Abstract

In contrast with traditional models of risk for suicidal ideation that combine multiple vulnerability components into one composite measure, weakest link perspectives posit that individuals are as vulnerable as their most vulnerable component (or “weakest link”). Such a perspective has been applied to depression, but has not been evaluated with respect to suicidal ideation. Thus, the goal of the present study was to apply a weakest link perspective to the study of suicidal ideation. We hypothesized that an individual’s “weakest link” among vulnerability components from the hopelessness theory (HT) and interpersonal psychological theory of suicide (IPTS) would interact with high levels of stress to predict increases in suicidal ideation over a six-week period better than the traditional conceptualizations of HT or IPTS. Participants were 171 college students who completed measures of cognitive vulnerability, stress, and suicidal ideation twice over a period of six weeks. Bayesian regression analyses supported our hypotheses. The data fit the weakest link model using HT and IPTS components better than traditional conceptualizations of HT and IPTS. This study implies that weakest link models from depression may be useful in understanding which individuals are most vulnerable to experiencing suicidal ideation in the context of stress.

Keywords: Suicidal ideation, weakest link, hopelessness theory, interpersonal psychological theory, suicide

Within the field of suicidology, much attention has been given to vulnerability theories. Generally, these models posit that certain types of maladaptive thinking, often in combination with the occurrence of stress, confer vulnerability to suicide. The theoretical models most relevant to the present study are the hopelessness theory (HT; Abramson, Metalsky, & Alloy, 1989) and the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide (IPTS; Joiner et al., 2009). Whereas HT is borrowed from the depression literature, IPTS is considered to be unique to suicide. One commonality between the two theories is that both include multiple components of vulnerabilities that are combined to create a unitary composite score. For example, HT includes beliefs that negative events are due to stable and global causes with negative consequences and self-implications, and IPTS includes beliefs that one is a burden to others and does not belong to a social group. Although vulnerability composites are predominantly used in research on suicide, research on depression has evolved to also use more complex examination of weakest link models (Abela & Sarin, 2002). In these models, vulnerability to depression is conferred by the most depressogenic component of a cognitive vulnerability. That is, rather than vulnerability to depression being represented by a composite score containing multiple components that can vary greatly in their severity, weakest link conceptualizations focus only on the most severe component.

Cognitive vulnerability theories propose similar mediating pathways to depression (and in our case, suicide) where the individual component vulnerabilities contribute to the development of maladaptive cognitions in response to stress. Weakest link models propose that when there are similar pathways to depression, the most severe vulnerability component will interact with stress (consistent with a diathesis-stress framework) to predict depressive symptoms (Abela, Aydin, & Auerbach, 2006). Surprisingly, despite shared vulnerabilities between depression and suicide, extant research typically has evaluated vulnerabilities to suicide using composite measures of individual theories separately, rather than applying a weakest link model to examine whether individuals’ most robust vulnerability factor (in the context of stress) would provide more precise specification of which individuals are likely to be at risk for suicide. The goal of this study is to examine a model that applies a weakest link theory to HT and IPTS in relation to suicide. We note that weakest link models do not necessarily imply that theories of composite vulnerabilities are not valid. Rather, weakest link models propose that different individuals might have exaggerated vulnerability from some components and not others. Whereas composite theories focus on the average level of vulnerability, weakest link theories focus on the most severe component of risk among a set of related vulnerability components. Thus, rather than supersede composite theories, weakest link models add explanatory value to the theories from which they are ultimately derived.

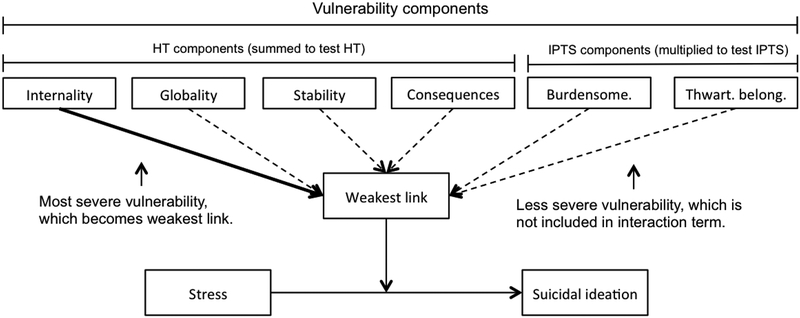

Figure 1 shows a conceptual diagram of the weakest link model. In this example, internality is the most negative domain, and is thus used for the score for this individual’s weakest link. For other individuals, other vulnerabilities (e.g., stability, burdensomeness, etc.) might be the weakest link. A test of the hopelessness theory would sum all of the HT variables, which would create an additive composite score that would then interact with stress to predict suicidal ideation. The weakest link approach stands in contrast to a standard test of the hopelessness theory that would sum all of the HT variables, which would create an additive composite that would interact with stress to predict suicidal ideation. The weakest link approach also stands in contrast to a standard test of IPTS, which would multiply the two IPTS variables to create a multiplicative interaction term that would be used to predict suicidal ideation (NB: stress is not involved in the interaction term for IPTS). Figures more fully demonstrating the hopelessness theory (Abramson, Metalsky, & Alloy, 1989, p. 360, figure 1) and interpersonal-psychological theory (Van Orden, et al., 2010, p. 576, figure 1) are available elsewhere.

Figure 1.

Graphical depiction of weakest link model

Hopelessness Theory

The original formulation of the hopelessness theory comes from the theory of learned helplessness (Abramson, Seligman, & Teasdale, 1978). According to this theory, individuals who make internal, stable, and global attributions for negative events and expect continued helplessness in the future are at risk for the development of depression. The hopelessness theory of depression (HT; Abramson, Metalsky, & Alloy, 1989) reformulated the helplessness model by deemphasizing the role of internal attributions, and focusing on the role of three depressogenic inferential styles about the causes, consequences, and self-implications of events: 1) global and 2) stable attributions for negative events, as well as 3) the expectation of negative future consequences and negative implications for the self. The tendency to make such negative inferences (i.e., an individual’s negative inferential style) is posited to induce hopelessness when individuals experience stressful life events, which then leads to the development of both depression (Alloy et al., 2000) and suicidal ideation (Abramson et al., 1998; Joiner & Rudd, 1995).

Although the majority of research testing HT in depression, and all of the research testing HT in suicide, has examined negative inferential style as a composite score that confers risk for depression and suicide, Abela and Sarin (2002) noted that such research has yielded mixed support for the theory. According to Abela and Sarin, a “weakest link” conceptualization of HT could account for the mixed findings. In the weakest link theory, vulnerability to depression in the face of stress is not conferred by the composite of all depressogenic inferential styles, but rather by the weakest or most depressogenic component of all depressogenic inferential styles. Support for this theory has generally been strong in a variety of samples including college students (Stone, Gibb, & Coles, 2009) and adolescents (Abela, McGirr, & Skitch, 2007; Stange, Alloy, Flynn, & Abramson, 2013), as well as in studies using a variety of methodologies, including multi-wave longitudinal (Abela et al., 2006) and daily diary (Abela et al., 2007) designs. Interestingly, although there have been weakest link modifications to HT in depression, research on HT in suicide has yet to evolve beyond examining “composite only” models. In the present study, we fill this gap by testing cognitive vulnerability to suicide within a weakest link framework.

Interpersonal psychological theory

The interpersonal psychological theory of suicide (IPTS; Joiner, 2005; Joiner et al., 2009) posits that completed suicide is the result of two factors: the desire to die (i.e., suicidal ideation) and the acquired capability to die. The desire and capability for suicide exist and are often studied independently. As the current study is concerned with the development of suicidal ideation, we focus only on the desire to die by suicide. Within IPTS, the desire to die by suicide is the byproduct of two component beliefs: 1) that one is a burden to others (i.e., perceived burdensomeness), and 2) that one does not belong to a social group (i.e., thwarted belongingness). These IPTS variables are frequently (but not exclusively, c.f. Conner, Britton, Sworts, & Joiner, 2007) examined as a synergistic composite whereby perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness interact with one another to predict suicidal ideation. Support for this model has been found in several large samples of college students (Joiner et al., 2009; Van Orden, Witte, Gordon, Bender, & Joiner, 2008). Like research on HT, there are also inconsistencies in support for IPTS. Indeed, although there are many studies that support IPTS, several studies fail to replicate the burdensomeness x belongingness interaction that is essential in IPTS (e.g., Bryan, Morrow, Anestis, & Joiner, 2010; Christensen, Batterham, Soubelet, & Mackinnon, 2013). Thus, it might also be that like HT, a weakest link framework could explain the inconsistent results of IPTS. Although not typically tested in interaction with stress, IPTS is compatible with a diathesis-stress framework (Van Orden et al. 2010). Although stress predicts suicide attempts and ideation (e.g., Bagge, Glenn, & Lee, 2013; Joiner & Rudd, 1995), not everyone who encounters stress experiences suicidal ideation or attempts. Thus, IPTS vulnerabilities could indicate which individuals are more likely to experience suicidal ideation following stress. This is especially true if the events lead someone to believe they are a burden to others or do not belong to a social group.

Hopelessness, interpersonal psychological, and weakest link theories

Although the original weakest link studies examined the weakest link within HT (e.g., Abela & Sarin, 2002), risk factors often do not operate in isolation. Therefore, recent research on depression has begun to expand the conceptualization of vulnerabilities to consider weakest links across multiple risk factors and theories (e.g., Abela & Hankin, 2008; Abela & Scheffler, 2008; Morris, Ciesla, & Garber, 2008; Reilly, Ciesla, Felton, Weitlauf, & Anderson, 2012). For example, it might not be apparent that an individual is vulnerable to suicide when examining their weakest link only among the HT variables if their true weakest link is within the IPTS variables (and vice versa). Thus, a more comprehensive test of the weakest link theory should involve the integration of as many potential weak “links” as possible. To that end, we included both HT and IPTS variables to test the weakest link hypothesis for suicidal ideation.

IPTS and HT, although often examined independently, may be compatible. Negative inferential style is a distal, stable risk factor that exists – and likely develops – in adolescence (Gibb & Alloy, 2006) and predicts the onset of major depressive disorder (Alloy et al., 2006). Perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness are proposed as proximal causes of suicidal ideation (Van Orden et al., 2010) and are predicted by depression (Kleiman, Liu, & Riskind, 2014) and negative inferential style (Kleiman, Law, & Anestis, in press). Thus, it might be considered in an etiological chain of suicidal ideation, that negative inferential style precedes perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness (and this relationship is possibly mediated by depression or hopelessness). If this is true, then a weakest link model that includes both HT and IPTS might provide an index of both distal and proximal risk for suicidal ideation. Further, it could be that those whose weakest links come from the IPTS variables are at more proximal risk for suicidal ideation than those whose weakest links are any of the HT variables. Also, consistent with the idea that IPTS and HT variables might be compatible, perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and hopelessness (the by-product of negative inferential style) interacted to predict suicidal ideation in a group of older adults (Christensen et al., 2013), such that those highest on all three variables experienced the highest levels of suicidal ideation.

The present study

Whereas theories of depression have moved from examination of composite vulnerability scores to examination of weakest link models, the related research on suicide has not progressed to the study of weakest link models. Thus, the primary goal of the present study is to test a weakest link theory of suicidal ideation. We take an additional novel approach by including the vulnerability factors from two theories, HT and IPTS, within our weakest link conceptualization, accounting for possible co-existing pathways to suicidal ideation. We have two related hypotheses. First, we hypothesize that a “weakest link” conceptualization can be applied to the study of suicidal ideation. That is, following exposure to high levels of stress, those with a more severe weakest link will experience more suicidal ideation than those with a less severe weakest link. Second, we hypothesize that this weakest link conceptualization will be a better explanation of suicidal ideation than traditional HT or IPTS composite scores. Given the strong overlap between depression and suicidal ideation (Lewinsohn, Rhode, & Seeley, 1994), we conducted all analyses using depressive symptoms as a covariate.

We expand further upon the extant research by using a statistical methodology more appropriate to addressing our question. Existing attempts to compare the weakest link theory to traditional conceptualizations (as well as other conceptualizations that are not the focus of this manuscript such as flexibility or keystone conceptualizations) often involve entering predictors from each theory into the same regression equation1 (Haeffel, 2008; Reilly et al., 2012). Such an approach is highly problematic because this involves entering duplicate or highly correlated predictors in the same model, resulting in high collinearity, and violating the assumptions of regression (e.g., Haeffel, 2008). The most appropriate analytical procedure to compare competing models is one that produces a model fit statistic that can be compared across models. Thus, in order to compare traditional and weakest link models and correct deficits in previous research, we utilized Bayesian analysis.

Method

Participants

Participants were 171 young adults2 (70% female) from a large, suburban university. Approximately 46% identified as Caucasian, 16% identified as Asian, 15% identified as African American, and the remainder self-identified with a different race. The age of participants ranged from 17 to 44 years old (M = 20.65 years, SD = 3.82). Parental consent was obtained for the three participants (1.8%) who were under 18.

We used various methods (e.g., specific wording on ads) to target those with increased suicidal ideation, as suicidal ideation is a relatively low base-rate occurrence in college students. As a result, some level of suicidal ideation (i.e., BSS > 0) was endorsed by 19.9% of the sample at Time 1 (T1), 15.7% of the sample at Time 2 (T2), and 26.8% at either T1 or T2. This is notably higher than cohort studies that found 12% of college students experienced suicidal ideation during college (Wilcox et al., 2010). Moreover, 14 participants (8%) reported on the demographics questionnaire that they had attempted suicide in the past, which is greater than the 6% lifetime prevalance rate estimates reported in epidemiological studies of college students (Arria et al., 2009).

Measures

Negative inferential style.

The Cognitive Style Questionnaire (CSQ; Haeffel et al., 2008) is a measure of HT that asks participants to imagine experiencing 12 negative events (e.g., “An important romantic relationship you are involved in breaks up because the other person no longer wants a relationship with you”) and then write down a cause for these events. Participants rate the internality, stability, and globality of this cause as well as the self implications and future consequences of the event on a 1 (e.g., totally caused by other people) to 7 (e.g., totally caused by me) scale. The 12 event scores for each scale are averaged. Averaging the five component scales creates the overall HT composite. The possible range of all components and the composite is 1 through 7. In a review of over 30 studies that utilized the CSQ, Haeffel et. al. (2008) report average composite scores ranging from 3.49 to 4.10 and internal consistencies ranging from .83 to .91. Alloy et al. (2000) report a one year test-retest reliability of .80.

Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness.

The Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (INQ; Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte, & Joiner, 2012) is a 15-item measure of the variables associated with IPTS. Six items measure thwarted belongingness (e.g. “These days, I feel disconnected from other people”) and nine items measure perceived burdensomeness (e.g., “These days, I think I make things worse for the people in my life”). Items are rated on a 1 (not true at all) to 7 (very true) scale and averages are computed to create scale scores. The possible range of scores for each item is thus 1 through 7. The INQ demonstrates strong convergent validity with measures of related constructs, such as social support and loneliness (Van Orden et al., 2012). Kleiman, Liu, and Riskind (2014) found that both the burdensomeness and belongingness scales of the INQ had a test-retest reliability of .60 in undergraduates across a six-week period.

Stress.

Stressful events were assessed using a modified version of the Life Events Interview (LEI; Francis-Raniere, Alloy, & Abramson, 2006). In an interview format, participants were asked about the occurrence (yes/no), date of last occurrence, and number of times the event occurred over the past six weeks. Participants were reminded of the date six weeks prior at T1 as well as an anchor to help them remember this date (e.g., “this was around finals time,” “this was right before Thanksgiving break”). Utilizing an interview method such as the LEI encourages accurate recall of events compared to a checklist measure. Indeed, participants who completed the LEI prospectively correctly recalled 100% of the events they had listed in a daily diary (Alloy & Abramson, 1999). Our version of the LEI included 63 stressful events that might be relevant to our young adult sample, such as “significant fight or argument with boyfriend or girlfriend that led to a serious consequence”. Occurrence of stressful events was summed together such that higher scores equaled more stressful events over the six-week period. We conceptualized stress in the present study as moderate to severe stressors that occurred over the six weeks prior to T1. We did this because in line with other studies of diathesis-stress models (e.g., Abela & Sarin, 2002), we wanted to capture stress that occurred over a sufficient period to activate a diathesis (e.g., negative cognitive style).

Suicidal ideation.

The Beck Suicide Scale (BSS; Beck & Steer, 1991) is a 21-item self-report measure. Nineteen items assess current suicidal ideation and two items assess past suicidal behavior. As we were only concerned with suicidal ideation, we used the 19 suicidal ideation items. Each item of the BSS asks about topics such as a wish to die and expectations of making a suicide attempt. Each item has three choices scored 0 (less severe response) to 2 (most severe response). Responses are totaled to create a composite suicidal ideation score, thus the scores can range from 0 to 38. In a sample of college students, Van Orden et al. (2010) found that the average score on the BSS was 1.50. Self-report measures of suicidal ideation, such as the BSS, are found to have high agreement with clinician-administered interviews. Indeed, Kaplan et al. (1994) found that interview and self report measures have at least 90% overlap on a variety of suicide constructs (e.g., suicidal ideation, attempts, etc.). They also found that participants tended to disclose current suicidal ideation more easily on self-report measures, possibly because there is less stigma and embarrassment when using a self-report measure. In line with Kaplan et al.’s (1994) finding, scores from the BSS are found to have a correlation of .90 with scores on the Scale for Suicidal Ideation (SSI; Beck, Kovacs, & Weissman, 1979), a clinician administered interview version of the BSS (Beck, Steer, & Ranieri, 1988). Moreover, the BSS in particular has a strong relationship with clinician ratings of suicidal ideation and demonstrates acceptable test-retest reliability over time periods as short as one week (r = .54; Beck, Steer, & Ranieri, 1988).

Depressive Symptoms.

The Center for Epidemiology Scale for Depression (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) is a 20-item self-report measure of depressive symptoms. Participants rate the frequency with which a variety of symptoms (e.g, “I felt lonely”) occurred over the past week on 0 (rarely) to 3 (most of the time) scale. Scores are summed to create an overall CES-D score that can range from 0 to 60. Radloff (1991) found strong internal consistency (α = .87) and an average score of 15.46 among college students. Hann, Winter, and Jacobsen (1999) found a test-retest reliability of .51 over a time period of 2.5 weeks.

Procedure

Participants were assessed twice over approximately six weeks (M = 45.34 days, SD = 11.67 days). At T1, participants completed a structured life events interview and then completed a computerized set of self-report measures on a tablet computer. This session lasted approximately 90 minutes. At T2, they again completed the structured life events interview and a shorter selection of measures on the tablet. This session lasted approximately half hour. Participants were compensated for their time with course credit. Stringent suicide risk assessment procedures supervised by a licensed clinical psychologist were used to ensure participant safety. No study sessions had to be discontinued due to imminent suicide risk.

Analytic strategy

We computed the weakest link scores according to the guidelines established by Abela’s previous work (Abela, Aydin, & Auerbach, 2006; Abela, McGirr & Skitch, 2007; Abela & Scheffler, 2008). We first standardized all possible component scores (i.e., subscales from CSQ and INQ) based on the sample distribution (i.e., created z-scores), which put all components on the same scale. Each participant’s weakest link was thus the highest score on any of the component scales. We computed the HT additive composite by summing the subscales of the CSQ. We computed the IPTS multiplicative composite by multiplying the two subscales of the INQ.

Using these scores, we then tested three competing models. Each model was a Bayesian regression analysis (see below) predicting T2 suicidal ideation with T1 suicidal ideation and T1 depressive symptoms as covariates. The first model tested HT as originally hypothesized: the main effects of stress (which was standardized; Aiken & West, 1991) and the CSQ composite score, as well as the interaction between the two, were entered in the regression equation. The second model tested IPTS as originally hypothesized: the main effects of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness, as well as the interaction between the two were entered in the regression equation. The third model tested a weakest link theory using both the HT and IPTS variables; the weakest link of all CSQ and INQ subscales, stress, and the interaction between the CSQ/INQ weakest link and stress were entered into the regression equation.

Although we report only the results of a model with all predictors entered simultaneously, we report model fit statistics separately for models with and without the interaction term. For example, in the model testing HT, we report fit statistics for a model with the covariates and main effects only (e.g., suicidal ideation, depressive symptoms, and the main effects of stress and CSQ) as well as the full model that also contains the interaction term (i.e., stress X CSQ). We did this to illustrate the interaction term’s relative contributions to model fit and variance accounted for (i.e., R2) in each model.

Bayesian analysis.

To examine our hypotheses, we used Bayesian regression analyses in Mplus version 7.11 (Muthén & Muthén, 2013). A key difference between Bayesian estimation and traditional “frequentist” estimation (e.g., maximum likelihood estimation) is that frequentist methods rely on the probability of the data fitting the model, whereas Bayesian estimation relies on the probability of the model fitting the data. As noted earlier, a major advantage of using Bayesian analyses in the present study is that it allows a comparison of models that avoids problems of multi-collinearity. Model fit is assessed using the deviance information criterion (DIC). The DIC values are similar to other “information criterion” variables (e.g., AIC, BIC) and indicate how well a model fits the data. DIC values are used to compare models to each other and lower DIC values indicate better fitting models. The general rule of thumb is that DIC values that differ by more than 10 represent models that are appreciably different. Another advantage of using Bayesian estimation relevant to the present study is that assumptions of normality from maximum likelihood regression do not apply to Bayesian statistics. Thus, the semi-continuous nature of T2 BSS suicidal ideation scores is not problematic to this estimation technique (Yuan & MacKinnon, 2009). Bayesian analyses are generally interpreted the same way as maximum likelihood regression. Beta weights and 95% confidence intervals (also called credibility or probability intervals) are produced. A 95% confidence interval that does not include zero is considered significant at p < .05.

There are several other important factors in conducting Bayesian analysis that should be discussed. Bayesian analysis estimates a posterior distribution from the observed variables in successive iterations based on the prior iterations, using Markov-Chain Monte Carlo estimation. An analysis is successful when it converges, that is, when the most recent estimate in the chain is very similar to the previous estimate. Convergence is assessed in Mplus by using the potential scale reduction (PSR) factor, where acceptable values are close to 1.00. The default settings in Mplus are to analyze two chains simultaneously using 100 iterations (or “links” in the chain). Then, according to Muthén (2010), we conducted the analyses again using 1000 iterations to see if there was any noticeable impact to the PSR. There was no noticeable difference between the analysis with 100 and 1000 iterations, and thus we report only the results using 100 iterations. One final set of model fit statistics is the posterior predictive chi-square 95% confidence interval and p value. These set of values are essentially a chi-square test of the difference between the observed and replicated (i.e., predicted) values. A model with good predictive values has a posterior predictive confidence interval that is nearly symmetrical around zero, with a negative lower interval and a p value that is near .50.

Results

Preliminary analyses

In the present study, all of the measures had acceptable internal consistency. The internality (α = .74), stability (α = .90), globality (α = .92), future consequences (α = .91) and self implications (α = .93) subscales of the CSQ all had acceptable to excellent internal consistency, as did the overall CSQ composite (α = .97). Both the perceived burdensomeness (α = .95) and thwarted belongingness (α = .90) subscales of the INQ demonstrated excellent internal consistency. The BSS demonstrated acceptable internal consistency at both time points (α = .74 and .87, respectively) and the CES-D had excellent internal consistency (α = .91).

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of the study variables are shown in Table 1. All of the HT and IPTS components, the HT composite score, weakest link, and suicidal ideation at both time points were positively intercorrelated among each other. The only exception was the self-implications component, which was not correlated with T2 suicidal ideation. Stress only was correlated with thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and weakest link. The frequency of weakest links was distributed as follows: internality (23.4%), stability (7.6%), globality (11.1%), consequences (9.4%), self (17.5%), thwarted belongingness (17%), and perceived burdensomeness (14%).

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations for all study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Internality (CSQ) | -- | ||||||||||||

| 2. Stability (CSQ) | .39*** | -- | |||||||||||

| 3. Globality (CSQ) | .44*** | .80*** | -- | ||||||||||

| 4. Consequences (CSQ) | .37*** | .88*** | .82*** | -- | |||||||||

| 5. Self (CSQ) | .49*** | .70*** | .64*** | .75*** | -- | ||||||||

| 6. Thwarted belongingness INQ) | .25** | .39*** | .36*** | .40*** | .33*** | -- | |||||||

| 7. Perceived burdensomeness (INQ) | .16* | .36*** | .32*** | .37*** | .27*** | .67*** | -- | ||||||

| 8. Weakest link (HT and IPTS) | .51*** | .60*** | .58*** | .61*** | .57*** | .75*** | .70*** | -- | |||||

| 9. HT composite | .59*** | .92*** | .90*** | .93*** | .85*** | .41*** | .36*** | .68*** | -- | ||||

| 10. Depressive symptoms (CES-D) | .25** | .46*** | .39*** | .48*** | .42*** | .76*** | .70*** | .73*** | .48*** | -- | |||

| 11. Stress (LEI) | −.02 | .12 | .04 | .15 | .11 | .24*** | .16* | .19* | .10 | .24*** | -- | ||

| 12. T1 suicidal ideation (BSS) | .18* | .26** | .19* | .24** | .20** | .64*** | .51*** | .55*** | .25* | .54*** | .20* | -- | |

| 13. T2 suicidal ideation (BSS) | .17* | .22** | .16* | .20** | .14 | .59*** | .46*** | .50*** | .21* | .45*** | .20* | .70*** | -- |

| Mean | 4.96 | 3.36 | 3.52 | 3.28 | 4.15 | 1.83 | 2.53 | 0.98 | 3.87 | 22.24 | 8.29 | 1.66 | 1.30 |

| Standard deviation | 0.74 | 1.21 | 1.23 | 1.19 | 1.10 | 1.09 | 1.23 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 10.77 | 7.44 | 3.99 | 4.03 |

Note. HT = Hopelessness Theory, IPTS = Interpersonal Psychological Theory of Suicide, CSQ = Cognitive Style Questionnaire (measure of HT), INQ = Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (measure of IPTS), CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale, LEI = Life Events Interview, BSS = Beck Suicide Scale,

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05

We conducted analyses to determine whether participants who endorsed suicidal ideation at T2 (i.e., BSS scores > 0) differed significantly on any of the demographic variables from those who did not endorse any suicidal ideation at T2 (i.e., BSS scores = 0). No differences were found for age, (t[169] = 0.61, p = .542), gender (χ2 [df=1] = 1.16, p = .281), or race (χ2 [df=6] = 4.69, p = .584). Thus, these demographic variables were not included in any further analyses. We also conducted a series of t-tests to determine whether participants who endorsed suicidal ideation at T2 (i.e., BSS scores > 0) differed significantly on any of the T1 variables from those who did not endorse any suicidal ideation at T2 (i.e., BSS scores = 0). These results are displayed in Table 2. As would be expected, those who endorsed suicidal ideation at T2 scored significantly higher on all study variables from those who did not endorse suicidal ideation at T2.

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations of T1 variables by T2 suicidal ideation status (presence vs. absence of ideation)

| Variable | No ideation (BSS = 0) | Ideation (BSS > 0) | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internality (CSQ) | 4.91 (0.73) | 5.23 (0.78) | 2.08* |

| Stability (CSQ) | 3.40 (1.18) | 4.20 (1.30) | 3.15* * |

| Globality (CSQ) | 3.23 (1.17) | 4.07 (1.22) | 3.34* * * |

| Consequences (CSQ) | 3.13 (1.12) | 4.12 (1.26) | 4.05* * * |

| Self (CSQ) | 4.06 (1.08) | 4.66 (1.11) | 2.59* * |

| Thwarted belongingness (INQ) | 2.22 (1.12) | 3.84 (1.41) | 6.52* * * |

| Perceived burdensomeness (INQ) | 1.58 (0.73) | 3.18 (1.72) | 7.99* * * |

| Weakest link (HT and IPTS) | 3.24 (0.83) | 4.02 (0.66) | 4.60* * * |

| HT composite | 3.75 (0.89) | 4.46 (1.00) | 3.67* * * |

| Depressive symptoms (CES-D) | 20.44 (9.17) | 32.46 (12.71) | 5.77* * * |

| Stress (LEI) | 7.60 (6.33) | 12.55 (11.53) | 2.96* * * |

| Suicidal ideation (BSS) | 0.62 (2.16) | 7.12 (6.24) | 9.77* * * |

Note. HT = Hopelessness Theory, IPTS = Interpersonal Psychological Theory of Suicide, CSQ = Cognitive Style Questionnaire (measure of HT), INQ = Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (measure of IPTS), CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale, LEI = Life Events Interview, BSS = Beck Suicide Scale,

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05, df for t-test = 169.

Hopelessness Theory

The first section of Table 3 shows the results of the regression analysis replicating HT. Only the main effect of T1 suicidal ideation was a significant predictor of T2 suicidal ideation. As the interaction between negative inferential style and stress was not a significant predictor of T2 suicidal ideation, we can conclude that our data fail to support HT. We note that these findings are not problematic for our hypotheses as the weakest link theory explicitly predicts inconsistent support for HT and has not been evaluated to date in predicting suicidal ideation.

Table 3.

Output from Bayesian regression analyses testing the hopelessness theory, interpersonal psychological theory, and a weakest link model

| B (95% CI) | p | R2 (95% CI) | DIC | PP 95% CI (p) | PSR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model: Hopelessness Theory (HT) | ||||||

| Step 1 | .49 (.38 – .58) | 787.10 | −10.05 – 10.67 (.49) | 1.00 | ||

| T1 Suicidal ideation | 0.65 (0.51 – 0.79) | < .001 | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | 0.04 (−0.02 – 0.10) | .086 | ||||

| Stress | 0.09 (−0.46 – 0.62) | .376 | ||||

| HT composite | −0.04 (−0.58 – 0.49) | .449 | ||||

| Step 2 | .50 (.39 – .58) | 787.02 | −10.74 – 11.70 (.48) | 1.02 | ||

| HT composite X stress | 0.47 (−0.15 – 1.11) | .067 | ||||

| Model: Interpersonal Psychological Theory (IPTS) | ||||||

| Step 1 | .52 (.42 – .60) | 836.85 | −10.62 – 10.94 (.52) | 1.00 | ||

| T1 Suicidal ideation | 0.53 (0.39 – 0.67) | < .001 | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | −0.03 (−0.09 – 0.04) | .220 | ||||

| Perceived burdensomeness | 0.13 (−0.69 – 0.95) | .373 | ||||

| Thwarted belongingness | 0.46 (−0.18 – 1.08) | .075 | ||||

| Step 2 | .54 (.45 – .62) | 829.67 | −5.89 – 8.84 (.50) | 1.01 | ||

| Burdensomeness X belongingness | 0.57 (0.19 – 0.95) | .001 | ||||

| Model: Weakest link using HT and IPTS variables | ||||||

| Step 1 | .49 (.38 – .58) | 799.53 | −10.20 – 10.66 (.48) | 1.00 | ||

| T1 Suicidal ideation | 0.55 (0.42 – 0.66) | .000 | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | −0.01 (−0.17 – 0.15) | .459 | ||||

| Stress | 0.02 (−0.09 – 0.13) | .353 | ||||

| Weakest Link | 0.14 (−0.03 – 0.30) | .051 | ||||

| Step 2 | .53 (.43 – .61) | 796.94 | −10.39 – 10.23 (.48) | 1.02 | ||

| Weakest link x stress | 0.19 (0.08 – 0.30) | .001 |

Note. DIC = deviance information criterion, PP = posterior predictive, PSR = potential scale reduction

Interpersonal Psychological Theory

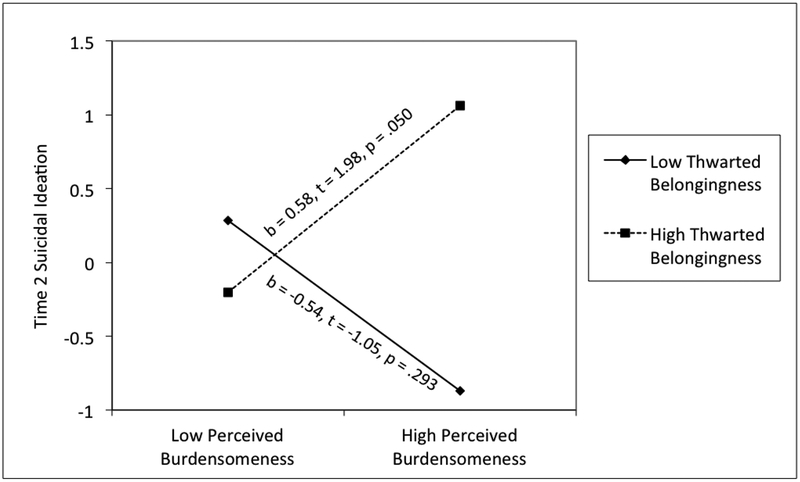

The second section of Table 3 shows the results of the regression analyses replicating IPTS. The model successfully converged. Time 1 (T1) suicidal ideation was the only significant predictor of T2 suicidal ideation in the first step, which accounted for approximately 52% of the variance in T2 suicidal ideation. The interaction between perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness significantly accounted for an additional 2% of the variance in T2 suicidal ideation in the second step. Given the significant interaction effect, we plotted and probed the interaction to better understand its effects. Figure 2 shows the relationship between perceived burdensomeness and T2 suicidal ideation as a function of high vs. low (+/− 1 SD) levels of thwarted belongingness. As can be seen from the figure, our data replicate the original IPTS findings. The relationship between perceived burdensomeness and T2 suicidal ideation was positive at high levels of thwarted belongingness and negative at low levels of thwarted belongingness.

Figure 2.

Plot of the test of IPTS: Perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness predicting Time 2 suicidal ideation

Note. Y axis is Time 2 suicidal ideation controlling for Time 1 suicidal ideation, thus a negative value indicates a decrease in suicidal ideation from Time 1 to Time 2.

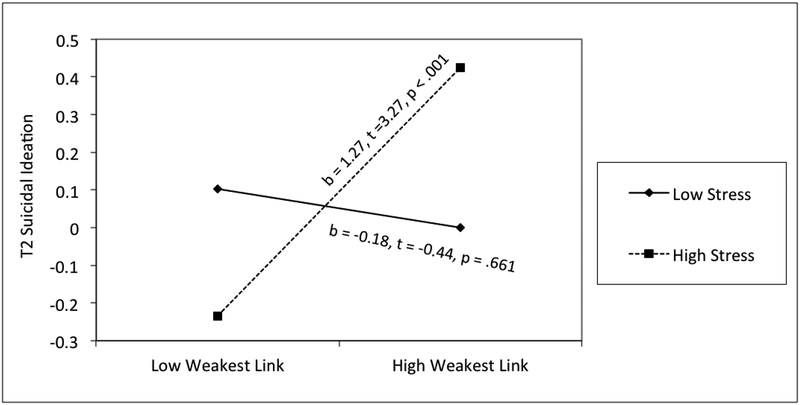

Weakest link theory with HT and IPTS variables

The third section of Table 3 shows the results of the regression analysis testing the weakest link theory using both HT and IPTS. The model successfully converged. T1 suicidal ideation was the only significant predictor of T2 suicidal ideation in the first step, which accounted for approximately 49% of the variance in T2 suicidal ideation. The weakest link X stress interaction significantly accounted for an additional 4% of the variance in T2 suicidal ideation in the second step. Given the significant interaction effect, we plotted and probed the interaction to better understand its effects. Figure 3 shows the plot of the relationship between weakest link and T2 suicidal ideation as a function of high vs. low (+/− 1 SD) levels of stress. As can be seen from the figure, the pattern of results supports the weakest link theory. The relationship between weakest link and T2 suicidal ideation was positive at high levels of stress. Consistent with the idea that a vulnerability (i.e., weakest link) is only related to negative outcomes when activated by stress, the relationship between weakest link and T2 suicidal ideation was not significant at low levels of stress.

Figure 3.

Plot of the interaction of the weakest link from HT and IPTS variables and stress predicting Time 2 suicidal ideation

Note. Y axis is Time 2 suicidal ideation controlling for Time 1 suicidal ideation, thus a negative value indicates a decrease in suicidal ideation from Time 1 to Time 2.

Summary and comparison of findings

Of the three analyses, two produced significant interactions: 1) the test of IPTS and 2) the test of weakest link theory using both HT and IPTS variables. When comparing the models, in which lower DIC equals better fit, the DIC for the HT + IPTS weakest link model (DIC = 796.94) was lower than the DIC for the IPTS model (DIC = 829.67). Using the general rule of thumb that models with DIC differences of at least 10 indicate meaningful differences, we can conclude that in a direct comparison of models, the IPTS + HT weakest link theory fits our data better than the IPTS theory. Although the DIC for the model testing HT only was the lowest of all models, when examining the relative contribution to variance accounted for (i.e., the model R2) of the interaction over the main effects in this model, it is clear that the majority of the predictive ability of this model came from the main effect of T1 suicidal ideation on T2 suicidal ideation. We would expect a large predictive contribution given the stability of suicidal ideation over time. Indeed, we included T1 suicidal ideation to create a more stringent test of our hypothesis and we were primarily concerned with factors that predicted T2 suicidal ideation above and beyond T1 suicidal ideation. By using this criterion, support for the weakest link model is enhanced because the weakest link X stress interaction offers some incremental utility in predicting T2 suicidal ideation above T1 suicidal ideation.

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to test an application of a weakest link conceptualization of vulnerability to suicidal ideation. Although the weakest link approach was initially proposed for depression, the present study is the first to our knowledge to apply such an approach to suicide. A novel addition to previous tests of the theory was that we included “weakest links” from two well-known cognitive vulnerability theories of suicidal ideation: the hopelessness theory (HT) and the interpersonal psychological theory (IPTS). Using Bayesian regression analysis, we tested three models and found support for two of them. Our data supported the model that tested the IPTS as originally hypothesized and the model that tested the weakest link theory using both IPTS and HT variables. In support of our hypothesis, when comparing these two models, the weakest link model using IPTS and HT variables fit the data better than the IPTS model. Additionally, both models predicted suicidal ideation above and beyond depressive symptoms, further suggesting that the weakest link conceptualization of vulnerability exists beyond the scope of severity of depressive symptoms.

We did not find support for the test of HT as originally hypothesized (i.e., CSQ composite score X stress interaction). There are several reasons why this might have occurred. First, in line with previous studies on weakest link theories of depression (e.g., Abela, et al., 2009; Abela & Sarin, 2002), the use of a composite score may obscure an individual’s true level of vulnerability if their “weakest link” is far weaker than other vulnerability components. For example, if person A had scores of 2, 3, and 4 on three vulnerability components, their additive score would be 9 and their weakest link would be 4. If person B had scores of 1, 2, and 5, their additive score would be 8 and their weakest link 5. HT would predict that under the same level of stressors, person A would be at higher risk than person B. The weakest link theory would predict that person B would be at higher risk. The weakest link theory might best detect such subtle differences in vulnerability to accurately predict who is at risk and who is not. Another reason is that we assessed a variety of stressors, but as Joiner and Rudd (1995) found, negative inferential style for interpersonal stress (i.e., items on the CSQ corresponding to interpersonal scenarios) interacts only with interpersonal stress to predict changes in suicidal ideation. Thus, it might be that the type of stressors assessed affected whether or not a negative inferential style was activated. Future studies that examine the effects of different events on cognitive vulnerability are needed. Regardless of the reason for the lack of significant findings, the non-significant findings themselves are not necessarily problematic as the initial conceptualization of the weakest link theory was in response to inconsistent support for HT. Thus, this finding only further supports the importance of weakest link approaches.

It is important to note that although the data fit the weakest link model best from a strict significance testing approach, the actual differences between models are not necessarily as clear cut. This is especially true when examining differences between the HT and weakest link models. The weakest link model explains 3% more variance and has a slightly more preferable model fit than the HT model. However, the HT model had the smallest DIC value and the vulnerability x stress interaction had a p value that was trending toward significance (p = .067) and this could be due to our sample size. This would suggest that the difference between the two models is relatively small. It also should be noted, however, that previous theoretical and empirical examinations of weakest link models suggest that differences between weakest link and traditional conceptualizations should be small. Weakest link models are designed to supplement – not replace – traditional models by explaining individual differences in vulnerability. Indeed, previous studies find high overlap between traditional and weakest link HT conceptualizations among college students (e.g., .93, Haeffel, 2008) and thus, we might expect only small differences between constructs with high overlap. Given the substantial burden of suicide among young adults, even small improvements to existing models of suicidal ideation has the potential to reduce the suffering and societal burden associated with suicide.

Despite the limitations regarding differences between models, the strongest implication from our findings is that weakest link conceptualizations from depression also can apply to the study of suicidal ideation. Weakest link approaches are particularly valuable as they move from a nomothetic approach that might overlook important unique features of an individual’s vulnerability to an idiographic approach where individuals at risk for suicidal ideation have unique configurations of vulnerability. Our findings imply that research on other forms of psychopathology, such as anxiety or disordered eating, might also benefit from weakest link conceptualizations. Our findings also suggest that there is merit in examining multiple theories of suicide risk together. Indeed, the model that fit the data best was the model that integrated both IPTS and HT vulnerabilities. Including vulnerabilities from only one theory may have caused erroneous conclusions to be drawn and the broader picture of suicide risk to be missed. The integration of multiple compatible theories of suicide risk and prevention is also compatible with the recent push towards transdiagnostic models of psychopathology (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema & Watkins, 2011), which may have implications for better prevention and intervention programs targeting individuals vulnerable to suicide. For example Silverman and Maris (1995) explicitly discuss the targeting an individual’s weakest link as the first course of a suicide intervention. Additional research is also needed that explores the role of factors from other theories of suicide risk outside of HT and IPTS in a weakest link framework. For example, Abela and Scheffler (2008) combine HT variables and rumination in a weakest link framework to predict depression symptoms. Given that rumination is also associated with risk for sucidal ideation (Smith, Alloy, & Abramson, 2006), future conceptualizations of weakest links of risk for suicidal ideation might include rumination.

Some discussion of episodic and chronic stressors is warranted. Whereas some stressful events might be isolated episodic occurrences, other stressors might be more chronic. Indeed, some individuals—such as those who have a negative inferential style (Hamilton et al., 2013; Safford, Alloy, Abramson & Crossfield, 2007) not only experience more stress, but actively generate future stressors (see Liu & Alloy, 2010). Given that episodic stressors tend to remit, individuals experiencing episodic stress might experience less of an effect of their weakest link on suicidal ideation because their stress levels vacillate over time whereas for others, the stress is chronically high. This effect is obscured, however, in light of research that finds episodic stressors can lead to other, related episodic stressors (Dohrewend, Link, Kern, Shrout, & Markowitz, 1990). For example, failing a test could lead an individual to believe they must prioritize their academic work, thus leading them to ending a romantic relationship.

The present study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. We used a relatively small sample of undergraduate students. This was an especially important issue for statistical power given that we observed relatively small effects, especially in the HT model. Thus, replication in larger samples is needed. Although the use of recruiting strategies to increase the base rate of individuals with suicidal ideation led to a rate of suicidal ideation greater than would be expected in undergraduate samples, we still had a relatively low base rate of suicidal ideation, especially compared to clinical samples. The use of a statistical technique appropriate for such skewed data helped in part to correct these limitations. Given the use of an undergraduate sample, these results suggest that screening for suicidal ideation using measures of both HT and IPTS is warranted. The implications for individuals in clinical settings are not entirely clear, however, and replication is needed in clinical samples (e.g., those with previous suicide attempts or relevant psychiatric disorders). We also evaluated suicidal ideation but not suicide attempts, so whether our findings will generalize to suicidal behavior is unknown. However, given that suicidal ideation is predictive of suicide attempts (Lewinsohn, Rohde, & Seeley, 1994), understanding which individuals are likely to experience suicidal ideation has important implications for preventing suicide. Another limitation was the use of self-report measures of suicidal ideation. Future studies could benefit from clinician-administered interviews of suicidality. A final limitation is that although we measured depression symptoms, we did not assess psychiatric diagnoses that might confer risk for suicidal ideation, such as major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder. Strengths of the study include the use of advanced statistical analyses, longitudinal data, and an interview measure of life events.

In summary, in the present study we found that a weakest link conceptualization of cognitive vulnerability can be applied to the study of suicide. Although the differences between models were small, the data best fit a model using a weakest link conceptualization of components from two theories of suicide: HT and IPTS. The strongest research implication for future investigation is that examination of pathways to suicidal ideation from multiple theories of suicide provides a better explanation than each theory does alone. Beyond the research implications, our findings imply clinically that among suicidal individuals, addressing the most severe vulnerability present first, rather than all vulnerabilities together, might prove to be the most effective intervention. Clinicians might consider administering the CSQ and IPTS to determine a patient’s weakest link, and thus, their level of current risk for suicidal ideation, as well as to understand the most beneficial vulnerability to modify.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported by NIMH Grants MH79369 and MH101168 to Lauren B, Alloy.

Footnotes

We note that in a test of the weakest link theory of depression in adolescents, Calvete, Villardón, and Estévez (2008) used structural equation modeling, which can produce model fit statistics that are comparable across models (e.g., AIC, BIC). However, Calvete et al. (2008) did not report these indices. They did include a lesser-used fit index, the Standardized Root Mean Residual, but used these values to assess absolute, rather than relative, fit. Moreover, had they used SRMR to compare relative fit across models, it may have actually challenged the weakest link theory. The SRMR for a model testing the self implications component of HT was more desirable than that of the weakest link.

The sample of 171 was from a larger sample of 245 that only completed the first time point. We ran a series of one-way ANOVAs comparing the 171 participants who completed both time points to the 74 participants who completed only the first time point on all Time 1 study variables (i.e., CSQ subscales, INQ subscales, CESD, and BSS). There were no significant differences on Time 1 variables between those who completed the study and those who did not (Ts range from 0.14 to 1,95, all p > .05).

Contributor Information

Evan M. Kleiman, Temple University

John H. Riskind, George Mason University

Jonathan P. Stange, Temple University

Jessica L. Hamilton, Temple University

Lauren B. Alloy, Temple University

References

- Abela JRZ, Aydin C, & Auerbach RP (2006). Operationalizing the “vulnerability” and “stress” components of the hopelessness theory of depression: A multi-wave longitudinal study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 1565–1583. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, McGirr A, & Skitch SA (2007). Depressogenic inferential styles, negative events, and depressive symptoms in youth: An attempt to reconcile past inconsistent findings. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 2397–2406. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, & Sarin S (2002). Cognitive vulnerability to hopelessness depression: A chain is only as strong as its weakest link. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 26, 811–829. doi: 10.1023/A:1021245618183 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, & Scheffler P (2008). Conceptualizing cognitive vulnerability to depression in youth: A comparison of the weakest link and additive approaches. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 1, 333–351. doi: 10.1521/ijct.2008.1.4.333 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abramson LY, Alloy LB, Hogan ME, Whitehouse WG, Cornette M, Akhavan S, & Chiara A (1998). Suicidality and cognitive vulnerability to depression among college students: A prospective study. Journal of Adolescence, 21, 473–487. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.87.1.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramson LY, Metalsky GI, & Alloy LB (1989). Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review, 96, 358–372. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-0649-8_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abramson LY, Seligman ME, & Teasdale JD (1978). Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 87, 49–74. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.87.1.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, & West SG (1991). Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Hogan ME, Whitehouse WG, Rose DT, Robinson MS, Kim RS, et al. (2000). The Temple-Wisconsin Cognitive Vulnerability to Depression Project: Lifetime history of Axis I psychopathology in individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 403–418. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Whitehouse WG, Hogan ME, Panzarella C, & Rose DT (2006). Prospective incidence of first onsets and recurrences of depression in individuals at high and low cognitive risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115, 145. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagge CL, Glenn CR, & Lee H-J (2013). Quantifying the impact of recent negative life events on suicide attempts. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 122, 359–368. doi: 10.1037/a0030371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Kovacs M, & Weissman A (1979). Assessment of suicidal intention: The Scale for Suicide Ideation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 47, 343–352. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.47.2.343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, & Steer RA (1991). Manual for Beck scale for suicidal ideation. New York: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Ranieri WF (1988). Scale for suicide ideation: Psychometric properties of a self a selft high and Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 499–505. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198807)44:4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Morrow CE, Anestis MD, & Joiner TE (2010). A preliminary test of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior in a military sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 48,347–350. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2009.10.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calvete E, Villardón L, & Estévez A (2008). Attributional style and depressive symptoms in adolescents: An examination of the role of various indicators of cognitive vulnerability. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46, 944–953. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen H, Batterham PJ, Soubelet A, & Mackinnon AJ (2013). A test of the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide in a large community-based cohort. Journal of Affective Disorders, 144, 225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR, Britton PC, Sworts LM, & Joiner J (2007). Suicide attempts among individuals with opiate dependence: The critical role of belonging. Addictive Behaviors, 32, 1395–1404. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BP, Link BG, Kern R, Shrout PE, & Markowitz J (1990). Measuring life events: The problem of variability within event categories. Stress Medicine, 6, 179–187. doi: 10.1002/smi.2460060303 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Francis-Raniere EL, Alloy LB, & Abramson LY (2006). Depressive personality styles and bipolar spectrum disorders: Prospective tests of the event congruency hypothesis. Bipolar Disorders, 8, 382–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00337.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, & Alloy LB (2006). A prospective test of the hopelessness theory of depression in children. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 35, 264–274. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeffel GJ (2008). Cognitive vulnerability to depressive symptoms in college students: A comparison of traditional, weakest-link, and flexibility operationalizations. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 34, 92–98. doi: 10.1007/s10608-008-9224-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haeffel GJ, Gibb BE, Metalsky GI, Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Hankin BL, Joiner TE Jr., et al. (2008). Measuring cognitive vulnerability to depression: Development and validation of the cognitive style questionnaire. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 824–836. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JL, Stange JP, Shapero BG, Connolly SL, Abramson LY, & Alloy LB (2013). Cognitive vulnerabilities as predictors of stress generation in early adolescence: Pathway to depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41, 1027–1039. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9742-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hann D, Winter K, & Jacobsen P (1999). Measurement of depressive symptoms in cancer patients: Evaluation of the center for epidemiological studies depression scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 46, 437–443. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(99)00004-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T (2005). Why People Die by Suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Selby EA, Ribeiro JD, Lewis R, & Rudd MD (2009). Main predictions of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior: Empirical tests in two samples of young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118, 634–646. doi: 10.1037/a0016500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, & Rudd MD (1995). Negative attributional style for interpersonal events and the occurrence of severe interpersonal disruptions as predictors of self-reported suicidal ideation. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 25, 297–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.1995.tb00927.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan ML, Asnis GM, Sanderson WC, Keswani L, de Lecuona JM, & Joseph S (1994). Suicide assessment: Clinical interview vs. self-report. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 50, 294–298. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman EM, Law KC, & Anestis MD, (2014). Do theories of suicide play well together? Integrating components of the hopelessness and interpersonal psychological theories of suicide. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 55, 431–438 doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman EM, Liu RT, & Riskind JH (2014). Integrating the interpersonal psychological theory of suicide into the depression/suicidal ideation relationship: A short-term prospective study. Behavior Therapy. 45, 212–221 doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2013.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, & Seeley JR (1994). Psychosocial risk factors for future adolescent suicide attempts. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 297 doi: v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RT, & Alloy LB (2010). Stress generation in depression: A systematic review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future study. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 582–593. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris MC, Ciesla JA, & Garber J (2008). A prospective study of the cognitive-stress model of depressive symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117(4), 719. doi: 10.1037/a0013741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B (2010). Bayesian analysis in Mplus: A brief introduction. Unpublished manuscript. http://www.statmodel.com/download/IntroBayesVersion,203.

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2013). Mplus User’s Guide. Seventh edition Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, & Watkins ER (2011). A heuristic for developing transdiagnostic models of psychopathology explaining multifinality and divergent trajectories. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 589–609. doi: 10.1177/1745691611419672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly LC, Ciesla JA, Felton JW, Weitlauf AS, & Anderson NL (2012). Cognitive vulnerability to depression: A comparison of the weakest link, keystone and additive models. Cognition & Emotion, 26, 521–533. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2011.595776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D Scale A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1991). The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 20, 149–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safford SM, Alloy LB, Abramson LY, & Crossfield AG (2007). Negative cognitive style as a predictor of negative life events in depression-prone individuals: A test of the stress generation hypothesis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 99, 147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman MM, & Maris RW (1995). The prevention of suicidal behaviors: An overview. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 25, 10–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.1995.tb00389.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JM, Alloy LB, & Abramson LY (2006). Cognitive vulnerability to depression, rumination, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation: multiple pathways to self-injurious thinking. Suicide & life-Threatening Behavior, 36, 443–454. doi: 10.1521/suli.2006.36.4.443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stange JP, Alloy LB, Flynn M, & Abramson LY (2013). Negative inferential style, emotional clarity, and life stress: Integrating vulnerabilities to depression in adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 42, 508–518. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.743104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone LB, Gibb BE, & Coles ME (2009). Does the hopelessness theory account for sex differences in depressive symptoms among young adults? Cognitive Therapy and Research, 34, 177–187. doi: 10.1007/s10608-009-9241-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, & Joiner TE (2010). The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide. Psychological Review, 117, 575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Gordon KH, Bender TW, & Joiner TE Jr. (2008). Suicidal desire and the capability for suicide: Tests of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior among adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 72–83. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox HC, Arria AM, Caldeira KM, Vincent KB, Pinchevsky GM, & O’Grady KE (2010). Prevalence and predictors of persistent suicide ideation, plans, and attempts during college. Journal of Affective Disorders, 127, 287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y, & MacKinnon DP (2009). Bayesian mediation analysis. Psychological Methods, 14, 301–322. doi: 10.1037/a0016972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]