This cross-sectional study uses investment and acquisition data from financial databases, news outlets, and press releases to describe the annual trends and geographic scope of private equity–backed acquisitions of dermatology practices in the United States through May 31, 2018.

Key Points

Question

What are the recent trends in private equity dermatology practice acquisitions throughout the United States?

Findings

This cross-sectional study of 5 financial databases found that private equity–backed dermatology management groups acquired 184 dermatology practices from 2012 to 2018, with the number of acquisitions increasing over time and broadening in geographic reach. These acquired practices comprised an estimated 381 dermatology clinics as of mid-2018, and the number of financing deals in which dermatology management groups raised capital increased over time.

Meaning

In recent years, private equity firms have increased their financial stakes in dermatology practices throughout the United States.

Abstract

Importance

Private equity (PE) firms invest in dermatology management groups (DMGs), which are physician practice management firms that operate multiple clinics and often acquire smaller, physician-owned practices. Consolidation of dermatology practices as a result of PE investment may be associated with changes in practice management in the United States.

Objective

To describe the scope of PE-backed dermatology practice acquisitions geographically over time.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study examined acquisitions of dermatology practices by PE-backed DMGs in the United States. Acquisition and investment data through May 31, 2018, were compiled using information from 5 financial databases. Transaction data were supplemented with publicly available information from 2 additional financial databases, 2 financial news outlets, and press releases from DMGs. All dermatology practices acquired by PE-backed DMGs were included. Acquisitions were verified to be dermatology practices that provided medical, surgical, and/or cosmetic clinical care. Private equity financing data were included when available. The addresses of clinics associated with acquired practices were mapped using spatial analytics software.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The number and location of PE practice acquisitions over time were measured based on the date of deal closure, the geographic footprint of each DMG’s acquisition, and the financing of each DMG.

Results

Seventeen PE-backed DMGs acquired 184 practices between May 1, 2012, and May 22, 2018. These acquired practices accounted for an estimated 381 dermatology clinics as of mid-2018 (assessment period from May 1 to August 31). The total number of PE-owned dermatology clinics in the United States was substantially larger because these data did not reflect DMGs that opened new clinics (organic growth); acquisitions data represented only the ownership transfer of existing practices from physician to PE-backed DMG. Practice acquisitions increased each year, from 5 in 2012 to 59 in 2017. An additional 34 acquisitions took place from January 1 to May 31, 2018. The number of financing rounds to sustain transactions mirrored the aforementioned trends in practice acquisitions. Clinics associated with acquired practices spanned at least 30 states, with 138 of 381 clinics (36%) located in Texas and Florida.

Conclusion and Relevance

The study findings suggest that PE firms have a financial stake in an increasing number of dermatology practices throughout the United States. Further research is needed to assess whether and how PE-backed ownership influences clinical decision-making, health care expenditures, and patient outcomes.

Introduction

Dermatology practices have caught the attention of private equity (PE) investors, who have sought to consolidate practices and produce economic value through operational efficiencies, revenue enhancement, increased market share, and economies of scale.1

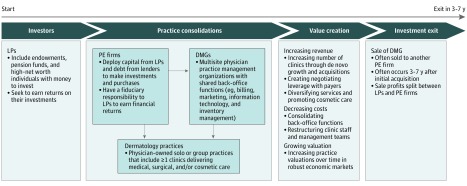

Although PE firms vary in their investment strategies, the typical investment process within dermatology practice management is described herein (Figure 1). Limited partners, such as endowments, pension funds, and high–net worth individuals, provide capital to a PE firm and seek future returns on their investment.2,3 The PE firm then makes a platform investment into a dermatology management group (DMG), which is a physician practice management company with integrated back-office functions that operates several dermatology clinics and often seeks to acquire and open new clinics.2,4,5,6 The DMG may subsequently receive financing, in the form of equity investments and debt, to fund the acquisition of dermatology practices (add-on acquisitions) or to grow organically by opening new clinics and hiring health care professionals to staff them (de novo growth).1,2,4,5 Additional strategies may be used to increase the valuation of the DMG by increasing revenue or decreasing costs.4 A robust bull market, which has been the case over the past decade, also contributes to rising practice valuations.3,7,8 After a holding period of 3 to 7 years, many PE firms seek to exit their investments, often through a secondary sale of the DMG to another PE firm.1 The roll-up model, which is characterized by platform investments into physician practice management companies, with subsequent add-on acquisitions and de novo growth, has also been reported in medical specialties beyond dermatology.6,9

Figure 1. Flow of Private Equity (PE) Investment Into Dermatology Practices.

DMGs indicates dermatology management groups; LPs, limited partners.

Other researchers, including Konda et al,10 have sought to describe PE investment in dermatology practices. The purpose of our study was to use a systematic and reproducible method to describe the recent trends and geographic reach of PE-backed acquisitions of dermatology practices through May 31, 2018, and to identify the major stakeholders completing these deals.

Methods

Building a Data Set of PE-Backed Transactions

Private equity–backed transactions in dermatology were identified using a methodical search of 5 financial databases—Capital IQ, CB Insights, Zephyr, Thomson ONE, and PitchBook—that compile data on business transactions in public and private markets.11,12,13,14,15 The first 4 databases were searched for dermatology practice acquisitions in the United States through May 31, 2018. The fifth financial database, PitchBook, was used to identify and quantify PE-backed financing rounds into DMGs. Additional transactions through May 31, 2018, were identified by searching press releases from the websites of DMGs and publicly available data on Bloomberg, Crunchbase, PR Newswire, and Business Wire.16,17,18,19 Detailed search criteria are described in eTable 1 in the Supplement. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Partners HealthCare, Boston, Massachusetts, with a waiver of consent because all data were publicly available.

Identifying Acquisitions of Dermatology Practices by PE-Backed DMGs

Private equity firms typically invest in large DMGs that subsequently expand in 2 ways: (1) through the acquisition of smaller practices and (2) through organic or de novo growth, defined as the opening of additional dermatology clinics.1,2,4,5 The search conducted for this study focused on the former strategy and aimed to quantify DMG expansion through practice acquisition. In addition, the search included only DMGs that had received at least 1 PE investment.

All firms that acquired dermatology practices were confirmed to be DMGs with PE financing. The names of all acquired entities were verified using Google searches to confirm that they were clinical practices offering services in medical, cosmetic, and/or surgical dermatology. The date of ownership turnover was assigned based on the date of deal closure. Transactions were excluded if the acquired entity was a hospital or clinic with multiple medical specialties, a pharmaceutical company, or a biotechnology firm. Acquisitions of dermatopathology facilities were also excluded, as were duplicate deals across databases, canceled deals, declarations of bankruptcy, and deals with no clear PE financing.

For DMGs with affiliated practices listed on their websites that were not captured in the database search but likely represented acquisitions, the practice acquisitions were included only if the year of acquisition could be identified through press releases.

Estimating Clinic Locations Associated With Acquired Practices

Because multiple clinic locations may have been acquired through the acquisition of a single practice, the specific dermatology clinic addresses associated with each acquired practice were identified. The number of clinics associated with each practice acquisition was not consistently reported; therefore, clinics associated with those practices as of mid-2018 (henceforth indicating the assessment period from May 1 to August 31) were identified through internet searches (eg, searches for clinic locations listed on the websites of acquired practices).

Of note, DMGs had more clinic locations listed on their websites as of mid-2018 than the number of clinics associated with the practice acquisitions identified by this search. If the additional clinics were not associated with a known acquisition, they were not included in the results because they likely reflected organic growth.

Mapping Geographic Footprint of Acquisition Activity

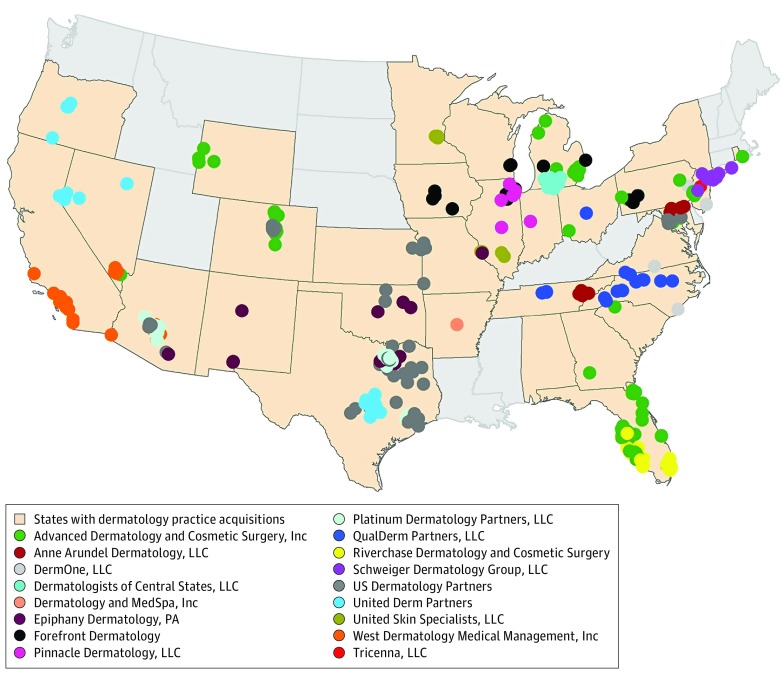

Spatial analytics software (ArcGIS; Esri) was used to create nationwide maps illustrating annual trends in dermatology practice acquisitions and the regional geographic footprint of acquisitions made by PE-backed DMGs (Figure 2 and Figure 3).20

Figure 2. Regional Footprint of Dermatology Practice Acquisitions by Dermatology Management Groups (DMGs).

Clinics associated with practices acquired by DMGs through May 31, 2018. Beige indicates states with dermatology practice acquisitions; colored circles, individual clinics. The map excludes de novo clinic expansion and does not represent the entire geographic footprint of each DMG today.

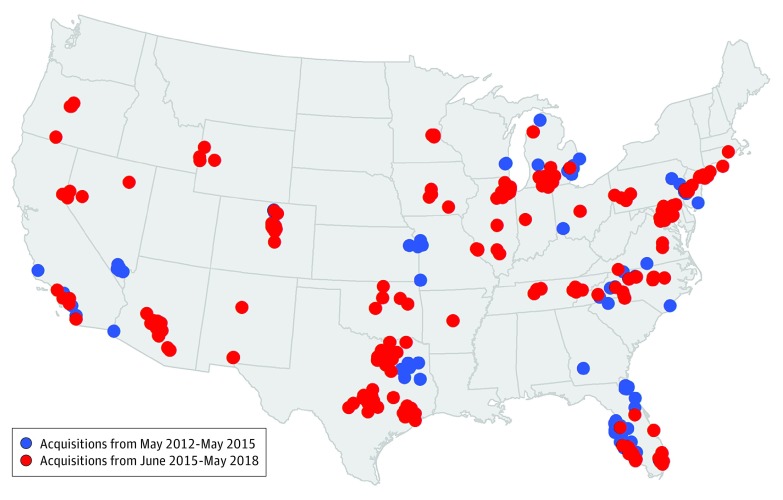

Figure 3. Geographic Distribution of Dermatology Practice Acquisitions Over Time.

Each color-coded circle indicates an individual clinic associated with an acquired practice. Although states with Dermatology Management Group–owned clinics have been mapped before, our map uniquely demonstrates the clinic locations associated with practice acquisitions.20

Identifying DMG Financing for Acquisitions

Private equity investments into DMGs were identified using Capital IQ, CB Insights, Zephyr, and Thomson ONE databases. All DMGs with documented PE financing were then searched using PitchBook to identify the first PE investment and all subsequent financing rounds, which included equity investments and debt financing. Results were triangulated among the databases, and transactions that appeared to be duplicates were excluded.

Results

Historical Trends in Acquisition of Dermatology Practices by PE-Backed DMGs

Our search found that PE-backed DMGs acquired 184 physician-owned dermatology practices between May 2012 and May 2018. These acquired practices accounted for an estimated 381 dermatology clinics as of mid-2018 and represented first-time transition of ownership from physician to PE-backed DMG. No dermatology practices in the data set were acquired by PE-backed DMGs before May 2012.

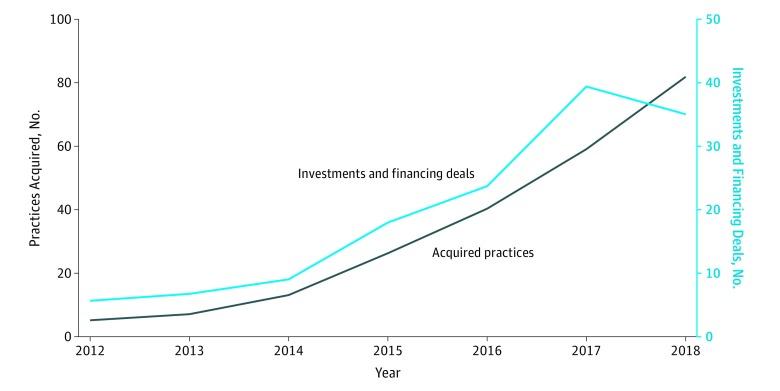

The number of practices acquired by PE-backed DMGs increased each year, with 5 acquisitions in 2012, 7 in 2013, 13 in 2014, 26 in 2015, 40 in 2016, and 59 in 2017. Thirty-four practices were acquired from January 1 to May 31, 2018 (Figure 4). Forty-one practice acquisitions occurred from May 1, 2012, to May 31, 2015, and 143 occurred from June 1, 2015, to May 31, 2018. The 41 practices acquired in the first 3 years were associated with an estimated 98 clinics as of mid-2018, and the 143 practices acquired in the subsequent 3 years were associated with an estimated 283 clinics as of mid-2018.

Figure 4. Dermatology Practice Acquisitions and Dermatology Management Group (DMG) Financing Over Time.

Annual trends in the number of DMG financing rounds and the number of practices acquired by private equity (PE)–backed DMGs over time. Data points for 2018 were projected based on the rate of acquisition and investment from January 1 to May 31, 2018. Dermatology practices acquired by PE-backed DMGs include practices acquired after the PE firms’ initial platform investments. Investments and financing deals for PE-backed DMGs include initial PE investments and subsequent equity investments and debt financing, and do not include DMG financing before the initial PE investment.

Seventeen PE-backed DMGs participated in acquisitions of dermatology practices. These DMGs collectively listed ownership on their websites of an estimated 743 dermatology clinics by mid-2018, with each DMG owning between an estimated 9 and 193 dermatology clinics (median, 36 clinics) as of mid-2018. This tally of DMG-owned clinics was higher than the 381 clinics attributed to practice acquisitions identified through the search strategy because it included organic growth (new clinics opened by DMGs), dermatopathology practices, and other nonpublicly reported acquisitions.

Historical Trends in PE Financing of DMGs

The search identified 23 DMGs that received PE investments. The earliest PE investment into a DMG was Charterhouse Equity Partners’ 1998 acquisition of Dermatology Partners, Inc (also known as MyskinMD), which subsequently filed for bankruptcy. The next PE investment was Vicente Capital Partners’ 2009 acquisition of US Dermatology Medical Management (also known as VCP Medical Management, Inc). All remaining transactions occurred between February 6, 2012, and May 24, 2018.

Seventeen PE-backed DMGs subsequently acquired dermatology practices. These DMGs raised capital 96 times between February 6, 2012, and May 24, 2018, including initial PE platform investments and subsequent equity investments and debt financing. The number of new financing deals each year increased, from 3 in 2012 to 32 in 2017, and 11 took place from January 1 to May 31, 2018. The number of new financing deals doubled, from 8 in 2014 to 17 in 2015, which corresponded to a doubling of practice acquisitions, from 13 to 26, during the same period.

Our search found that 6 DMGs in the data set received PE investments but did not subsequently acquire any dermatology practices. These DMGs received 16 financing rounds (1 in 1998, 2 in 2009, 4 in 2011, and 9 from 2012-2018).

Regional Distribution of DMGs

Some DMGs acquired practices in several regions of the United States (Table and Figure 2). However, many had a regional focus. For example, Schweiger Dermatology Group, LLC focused on acquiring New York practices, while Riverchase Dermatology and Cosmetic Surgery acquired a number of practices in Florida (Figure 2).

Table. DMGs With PE Investmentsa.

| DMG | DMG Notes | Equity Investorsb | Disclosed Funding Since First PE Investment or Buyout, $, Millionsc | Total Clinics, No.d |

Practices Acquired, No. (No. of Clinics)e | Acquisition Activity, y | States With Clinicsd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult & Pediatric Dermatology, PC | Also known as APDerm | Waud Capital Partners, LLC | 39.4 | 11g | 0 | NA | MA, NH |

| Advanced Dermatology & Cosmetic Surgery, Inc | Also known as ADCS or ADCS Clinics | Audax Groupf; First Capital Partners, LLCf; Harvest Partners, LP | 463.7 | 193 | 47 (92) | 2012-2017 | AZ, CO, FL, GA, MD, MI, NV, OH, PA, RI, SC, TX, VA, WY |

| Anne Arundel Dermatology, LLC | Also known as AAD or ADM | New MainStream Capital; New Mountain Capital, LLC; Pantheon Ventures, Inc | 94.2 | 43 | 12 (20) | 2015-2018 | MD, TN, VA |

| Dermatologists of Central States, LLC | Also known as DOCS | Sheridan Capital Partners | 160.9 | 41g | 1 (6) | 2017 | IN, MS, OH |

| Dermatology and MedSpa, Inc | Formerly The Dermatology Center | Pharos Capital Group, LLC | Undisclosed | 21g | 1 (18) | 2016 | AR, NC, TN, TX, VA |

| Dermatology Partners, Inc | Also known as MySkin MD; filed for bankruptcy on an undisclosed date | Charterhouse Equity Partners | Undisclosed | Unknown | 0 | NA | FL |

| Dermatology Solutions Group, LLC | Formerly Gulf Coast Dermatology; clinical practice known as Dermatology Specialists; PE investor sold its stake on an undisclosed date | Cressey & Company, LPf | Undisclosed | 23g | 0 | NA | AL, FL, GA, MS |

| DermOne, LLC | Formerly Accredited Dermatology; 9 clinics were acquired by Schweiger Dermatology Group, LLC, and 1 clinic was acquired by Forefront Dermatology in March 2018 | Westwind Investors, LP | Undisclosed | 9g | 4 (4) | 2012-2013 | NJ, NC, VA |

| Epiphany Dermatology, PA | NA | CI Capital Partners, LLC | Undisclosed | 36 | 9 (19) | 2017-2018 | AZ, IA, MO, NM, OK, TX |

| Forefront Dermatology | Formerly Dermatology Associates of Wisconsin, SC | Goldman Sachs Merchant Banking Divisionf; OMERS Private Equity, Inc; Penfund; Varsity Healthcare Partnersf; undisclosed investors | 570.0 | 121 | 9 (17) | 2012-2017 | AL, DC, FL, IL, IN, IA, KY, MD, MI, MN, MO, OH, PA, VA, WI |

| Pinnacle Dermatology, LLC | NA | Chicago Pacific Founders, Inc | Undisclosed | 22 | 4 (7) | 2017-2018 | IL, IN, MI |

| Platinum Dermatology Partners, LLC | NA | Sterling Partners | 77.0 | 31 | 11 (30) | 2016-2018 | AZ, TX |

| QualDerm Partners, LLC | Also known as QDP | Apple Tree Partnersf; Cressey & Company, LP; Granite Growth Health Partners, LP | 31.8 | 18 | 11 (17) | 2014-2018 | NC, OH, SC, TN, VA |

| Riverchase Dermatology and Cosmetic Surgery | Also known as Riverchase MSO, LLC; formerly Naples Center for Dermatology and Cosmetic Surgery | GMB Mezzanine Capital, LP; GTCR, LLC; Prairie Capital, LPf | Undisclosed | 37 | 11 (22) | 2013-2018 | FL |

| Schweiger Dermatology Group, LLC | Formerly Clear Clinic and Schweiger Dermatology Management Company | LLR Partners, Inc; LNK Partners; SV Health Investors, LLC; Zenyth Partners, LP; undisclosed investors | 175.4h | 40 | 7 (9) | 2016-2017 | NJ, NY |

| Skin and Beauty Center, Inc. | Also known as SBC | Gemini Investors; Granite Capital Partners, LLC | Undisclosed | 6g | 0 | NA | CA |

| Skin & Cancer Associates, LLP | Also known as SCA | Susquehanna Private Capital, LLC | Undisclosed | 27g | 0 | NA | FL |

| Tricenna LLC, PC | Formerly The Dermatology Group | PNC Erieview Capital; The Riverside Company | Undisclosed | 23 | 2 (2) | 2017 | CT, NJ, NY, PA |

| United Derm Partners | Also known as UDP | Frazier Healthcare Partners | Undisclosed | 22g | 4 (20) | 2016-2018 | CA, NV, OR, TX |

| United Skin Specialists, LLC | Also known as USS | Clearwater Equity Group, Inc; Tonka Bay Equity Partners, LLC | Undisclosed | 9 | 6 (9) | 2015-2016 | IL, MN, MO |

| US Dermatology Medical Management, Inc | PE investor sold its stake as of 2016 | Vicente Capital Partners, LLCf | 10.2 | Unknown | 0 | NA | Unknown |

| US Dermatology Partners | Also known as Oliver Street Dermatology Management, LLC; formerly Dermatology Associates and Dermatology Associates of Tyler | ABRY Partners, LLC; Bay Capital Investment Partnersf; Brookside Mezzanine Partnersf; Candescent Partners, LLCf; Eagle Private Capital, LLCf; Harbert Credit Solutionsf; Providence Equity Partners, LLCf; Resolute Capital Partnersf; Spring Capital Partners, LPf; undisclosed investors | 399.2 | 65 | 32 (63) | 2012-2018 | AZ, KS, LA, MD, MO, OK, TX, VA |

| West Dermatology, LLC | NA | Enhanced Equity Funds, LP | Undisclosed | 34 | 13 (26) | 2015-2018 | AZ, CA, NV |

Abbreviations: AL, Alabama; AR, Arkansas; AZ, Arizona; CA, California; CO, Colorado; CT, Connecticut; DC, District of Columbia; DMGs, Dermatology Management Groups; FL, Florida; GA, Georgia; IA, Iowa; IL, Illinois; IN, Indiana; KS, Kansas; KY, Kentucky; LA, Louisiana; MA, Massachusetts; MD, Maryland; MI, Michigan; MN, Minnesota; MO, Missouri; MS, Mississippi; NA, not applicable; NC, North Carolina; NH, New Hampshire; NJ, New Jersey; NM, New Mexico; NV, Nevada; NY, New York; OH, Ohio; OK, Oklahoma; OR, Oregon; PA, Pennsylvania; PE, private equity; RI, Rhode Island; SC, South Carolina; TN, Tennessee; TX, Texas; VA, Virginia; WI, Wisconsin; WY, Wyoming.

Obtained from Capital IQ, CB Insights, Thomson ONE, and Zephyr databases.

Includes all firms with equity investments and does not include lenders or other debt financing firms without equity co-investments.

Includes initial platform investments and subsequent equity investments and debt financing, and does not include DMG financing prior to initial PE investment. The dollar amounts of many investments were undisclosed; therefore, the amounts reported underestimate each firm’s total financing as of mid-2018. Most dollar amounts were calculated from data reported on PitchBook; other databases containing financing information were used to supplement the calculations for Forefront Dermatology, Platinum Dermatology Partners, LLC, Schweiger Dermatology Group, LLC, US Dermatology Medical Management, Inc, and US Dermatology Partners.

Obtained from DMG websites as of mid-2018 (assessment period from May 1 to August 31).

Estimated number of clinics associated with these DMGs as of mid-2018 (assessment period from May 1 to August 31).

Former rather than active investor.

Estimated number of total clinics as of December 31, 2018.

Raised an additional $14.1 million in angel investments before the first PE investment.

Geographic Expansion of Acquisition Activity Over Time

As the number of practice acquisitions increased, the geographic footprint of PE-funded consolidation expanded. Private equity–backed acquisitions of dermatology clinics occurred in 30 states, with Florida and Texas accounting for 36% of the clinics associated with acquired practices (Figure 3 and eTable 2 in the Supplement). Many early acquisitions occurred in Florida, and acquisition activity in Texas increased between 2016 and 2018 (Figure 2 and eTable 2 in the Supplement). Recent acquisitions also occurred in less populous states, such as Arkansas, Iowa, Minnesota, Oklahoma, Oregon, and Wyoming. Clinics associated with practices acquired in the 3 years after May 2015 were located in 26 states compared with 18 states for practices acquired in the previous 3 years (Figure 2).

Discussion

The data analysis identified 184 dermatology practices that were acquired by 17 PE-backed DMGs from May 2012 to May 2018. These practices comprised an estimated 381 clinics as of mid-2018. Consolidation increased each year beginning in 2012, with 11.8 times as many practices acquired in 2017 (59) than in 2012 (5). A 349% increase was noted in the number of practices acquired from the 3 years before June 1, 2015 (41), to the 3 years after June 1, 2015 (143) (Figure 2). The number of practices acquired increased a mean of 65% each year between 2012 and 2017 (range, 40%-100%), corresponding with a compound annual growth rate of 50.9%.

The results suggest that PE-backed dermatology practice consolidation is increasing, which is consistent with data reporting that fewer dermatologists are working in solo practices than they were a decade ago.21,22,23 This study used a method that was reproducible and, to our knowledge, novel, and its results supported similar findings by Konda et al.10

Financing of DMGs has increased over time, suggesting that practice acquisitions by DMGs may continue in the future. However, this trend may be tempered by changes in market conditions (eg, stock market volatility, rising interest rates, or recession), the uncertainty of future changes to physician reimbursement, and rising valuation multiples for DMGs. As valuation multiples for DMGs increase, PE firms must spend more to acquire them, with lower potential returns on investment.

The geographic footprint of PE acquisitions continues to expand. While some DMGs have acquired practices in multiple regions of the United States, many have strong regional footprints, with increasing local market share. Texas and Florida together account for more than one-third of clinics associated with the practices acquired to date, although consolidations have broadened to include clinics in at least 30 states. This geographic expansion may be a response to a number of factors, such as the growing demand for dermatology services, the opportunity for increased market share, regional variation in the cost of acquiring add-on practices, and the emergence of more DMGs.

It is important to consider this wave of dermatology practice consolidations in the broader context of the health care landscape. Physician practice consolidation began in the 1990s, when managed care and increased administrative burdens led to mergers of practices primarily owned by primary care physicians in an effort to improve efficiency and gain bargaining leverage.24 More recently, PE-funded consolidation has diversified into other sectors of health care delivery, from storefront retail medicine (eg, CVS MinuteClinic) to hospices and behavioral health practices.23 From 2012 to 2017, a 34% compound annual increase was reported in buyouts of North American retail health companies, including those providing dermatology, dentistry, ophthalmology, physical therapy, veterinary, fertility, and urgent care services.2

Practice consolidation offers theoretical economies of scale through the shared use of back-office functions, such as marketing, billing, scheduling, inventory management, and information technology. Large group practices may also negotiate more favorable reimbursement contracts with payers; alternatively, practices may offer below-market rates in exchange for relative exclusivity of a managed care patient population.22,25,26 Private equity firms can provide capital for real estate, specialized equipment (eg, laser therapy and phototherapy), and electronic health record systems. Ideally, these changes allow practices to improve profitability and diversify services while relieving physicians of administrative burdens.

Despite enthusiasm from investors, PE-backed dermatology practice acquisitions remain controversial.1,21 Physicians have raised concerns about the loss of physician autonomy and conflicts of interest that may arise from profit-seeking behaviors, as PE firms have a fiduciary responsibility to generate investor returns.21,27 Large groups that employ multispecialty physicians (eg, dermatopathologists, Mohs and cosmetic surgeons, and pediatric dermatologists) can take advantage of the in-office exception to the Stark Law, which allows physicians to legally refer patients to other professionals employed by the same group practice.28 Physicians may also be required by their employers to do so. These self-referrals enable large group practices to keep highly reimbursed services, such as Mohs surgery, within their network, and may also provide incentives that increase usage of these services.28

Physicians have also expressed concern that PE-backed dermatology practices may emphasize the employment of midlevel clinicians (eg, physician assistants and nurse practitioners) with varying levels of formal dermatology training.29 The employment of physician extenders in dermatology increased across all practice models, from 28% in 2005 to 46% in 2014, although such employment remains more common in large group practices (46%) than in practices with a single physician (34%).30 Concern has also been raised about potentially insufficient levels of direct physician supervision of midlevel clinicians.29 In addition, PE firms generally invest in a given entity for 3 to 7 years and therefore may be more motivated by short-term profits than long-term sustainability.1

The implications of PE-backed consolidation may stem from the significant differences between physician-owned and PE-backed practices. Physicians who operate solo practices have financial responsibility for themselves and their employees, while PE firms have an additional fiduciary responsibility to generate financial returns for their investors. Solo practices are also typically led by physicians, while DMGs may have nonphysician managers employed in key decision-making roles. The effect of external accountability to investors will be important to monitor.

While practice consolidations have likely produced operational efficiencies that benefit both physicians and patients, the effect of consolidation on patient clinical outcomes and health care expenditures has not, to our knowledge, been addressed in the literature. Additional studies are also needed to understand the effect of consolidation on solo practitioners. For example, large group practices may direct referrals for highly lucrative services, such as Mohs surgery and dermatopathology, to physicians within their own network and may have the bargaining power to negotiate more favorable reimbursement contracts with insurers.1,27 Future research regarding practice patterns should assess staffing of physicians and midlevel clinicians, usage of procedures and tests, reimbursement rates and acceptance of Medicaid patients, use of information technology services, and trends in provider compensation, autonomy, satisfaction, and burnout. The changing business models of care delivery will necessitate a closer look at the subsequent effects on patient outcomes. As value-based care and alternative payment models become increasingly prevalent, outcomes data may soon play a more central role in the valuation and strategic rationale for physician practice consolidation.31

Limitations

These findings must be interpreted in the context of the study’s design. Public data regarding PE-backed transactions are inherently limited; thus, it was difficult to determine the extent of missing data. We sought to be as comprehensive as possible by triangulating nonoverlapping data from multiple financial databases and verifying closed deals through internet searches and press releases published on the websites of the DMGs. Because many transactions are not publicly disclosed, the results likely underestimated the scope of dermatology practice acquisitions. PitchBook reported at least 15 additional PE-backed DMGs that were not identified by the search methods but that may have acquired practices.10,15

The results also likely underreported direct acquisitions of small physician-owned practices by small PE firms. In addition, the data underestimated the number of clinics transitioning from physician to PE-backed ownership because the specific clinics associated with each DMG at the time of the DMG’s initial PE investment had not been disclosed.

The number of clinic locations was estimated because the clinic addresses associated with each practice acquisition were identified through an internet search. However, the clinic locations associated with acquired practices as of mid-2018 could be used to determine an approximation of the number of clinics that transferred from physician to PE-backed ownership at the time of acquisition. This approximation was possible because while DMGs expand through add-on acquisitions and organic growth, add-on dermatology practices are less likely to expand their clinic locations after being acquired.

In addition, the study sought to describe the ownership transfer, from physician to PE-backed DMG, of existing dermatology practices through acquisitions. By excluding the organic growth of DMGs through the direct opening of new clinics, this method underestimated the total footprint of PE-backed ownership of dermatology practices. Acquisitions of dermatopathology clinics, acquisitions not publicly reported, and acquisitions with an unknown date of deal closure were also excluded. The search strategy therefore identified 381 clinics associated with practice acquisitions by 17 DMGs, yet these DMGs collectively listed ownership of 743 individual dermatology clinics on their websites as of mid-2018.

Conclusions

Private equity–backed consolidation of dermatology practices has increased in recent years. The proliferation of PE investments into DMGs that manage multi-site delivery networks has contributed to the increase in practice acquisitions and the potential achievement of economies of scale. Although many DMGs have focused their acquisition activity within a specific region, acquisitions have spread geographically over time. Operational and management differences between PE-backed and physician-owned dermatology practices have not publicly been well described; thus, their effect on patients is not fully understood. Future studies should investigate the effect of PE-backed practice consolidation on practice patterns, health care expenditures, and patient outcomes.

eTable 1. Database Search Strategy

eTable 2. Practice Acquisitions by State

References

- 1.Resneck JS., Jr Dermatology practice consolidation fueled by private equity investment: potential consequences for the specialty and patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(1):13-14. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacArthur H. Bain & Co’s global private equity report 2018. Bain & Co website. https://www.bain.com/insights/global-private-equity-report-2018/. Published February 26, 2018. Accessed February 25, 2019.

- 3.McKinsey & Co. The rise and rise of private markets: McKinsey global private markets review 2018. McKinsey & Co website. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/private%20equity%20and%20principal%20investors/our%20insights/the%20rise%20and%20rise%20of%20private%20equity/the-rise-and-rise-of-private-markets-mckinsey-global-private-markets-review-2018.ashx. Published February 2018. Accessed February 25, 2019.

- 4.MacArthur H, Elton G, Haas D, Varma S. Rewriting the private equity playbook to combine cost and growth. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/baininsights/2017/04/08/rewriting-the-private-equity-playbook-to-combine-cost-and-growth/#265d5e144445. Published April 8, 2017. Accessed February 25, 2019.

- 5.Greenfield M. Private equity firms increase focus on add-ons. PE Hub Network website. https://www.pehub.com/2015/02/private-equity-firms-increase-focus-on-add-ons/. Published February 10, 2015. Accessed February 25, 2019.

- 6.Consulting LEK. Physician practice management—a new chapter. Executive Insights. 2013;XV(21):1-6. https://www.lek.com/sites/default/files/insights/pdf-attachments/LEK_Physicial_Practice_Management_A_New_Chapter.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2019.

- 7.Lykken A. The positive impact of strong public markets on PE. PitchBook website. https://pitchbook.com/news/articles/the-positive-impact-of-strong-public-markets-on-pe. Published April 6, 2018. Accessed February 25, 2019.

- 8.Sarhan A. A quick look at valuations and market cycles. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/adamsarhan/2018/04/03/a-quick-look-at-valuations-market-cycles/#18c9c246264c. Published April 3, 2018. Accessed February 25, 2019.

- 9.Gabriel JM, Gale AD, Lambert LR, Whitton JP PE investment in physician practice management—what’s to come in 2019? Baker & Hostetler website. https://www.bakerlaw.com/alerts/pe-investment-in-physician-practice-management-whats-to-come-in-2019. Published February 13, 2019. Accessed April 15, 2019.

- 10.Konda S, Francis J, Motaparthi K, Grant-Kels JM Future considerations for clinical dermatology in the setting of 21st century American policy reform: corporatization and the rise of private equity in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;SO190-9622(18):32667. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Capital IQ: about this database. Harvard Business School Baker Library/Bloomberg Center website. https://www.library.hbs.edu/Find/Databases/Capital-IQ. Accessed February 25, 2019.

- 12.CB insights & industry analytics: about this database. Harvard Business School Baker Library/Bloomberg Center website. https://www.library.hbs.edu/Find/Databases/CB-Insights-Industry-Analytics. Accessed February 25, 2019.

- 13.Zephyr: about this database. Harvard Business School Baker Library/Bloomberg Center website. https://www.library.hbs.edu/Find/Databases/Zephyr. Accessed February 25, 2019.

- 14.Thomson ONE: about this database. Harvard Business School Baker Library/Bloomberg Center website. https://www.library.hbs.edu/Find/Databases/Thomson-ONE. Accessed February 25, 2019.

- 15.Who and what you can research with PitchBook. PitchBook website. https://pitchbook.com/data. Accessed February 25, 2019.

- 16.Healthcare providers and services: company overview. Bloomberg website. http://www.bloomberg.com. Accessed February 25, 2019.

- 17.About Crunchbase. Crunchbase website. https://about.crunchbase.com/about-us/. Accessed February 25, 2019.

- 18.Media room: about PR Newswire. Cision PR Newswire website. http://prnewswire.mediaroom.com/index.php. Accessed February 25, 2019.

- 19.About us. Business Wire website. https://www.businesswire.com/portal/site/home/about/. Accessed February 25, 2019.

- 20.About ArcGIS. Esri website. https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/about-arcgis/overview. Accessed February 25, 2019.

- 21.Margosian E. Pulling back the curtain on private equity. Dermatology World. 2018;28(1):32-41. https://www.aad.org/File Library/Dermworld/January-2018-dw.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Welch WP, Cuellar AE, Stearns SC, Bindman AB. Proportion of physicians in large group practices continued to grow in 2009-11. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(9):1659-1666. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robbins CJ, Rudsenske T, Vaughan JS. Private equity investment in health care services. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(5):1389-1398. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson JC. Consolidation of medical groups into physician practice management organizations. JAMA. 1998;279(2):144-149. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.2.144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coldiron BM. Well, I figured it out…I owe my soul to the company store. Dermatology News MDedge/Dermatology website. https://www.mdedge.com/edermatologynews/article/152321/business-medicine/well-i-figured-it-out-i-owe-my-soul-company-store. Published November 17, 2017. Accessed February 25, 2019.

- 26.Ginsburg PB. Wide variation in hospital and physician payment rates evidence of provider market power. Res Brief. 2010;(16):1-11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krause P. Private equity firms are suddenly buying dermatology practices—here’s why. Business Insider http://www.businessinsider.com/why-private-equity-firms-buy-dermatology-practices-2016-8. Published August 22, 2016. Accessed February 25, 2019.

- 28.Mannava KA, Bercovitch L, Grant-Kels JM. Kickbacks, Stark violations, client billing, and joint ventures. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31(6):764-768. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hafner K, Palmer G Skin cancers rise, along with questionable treatments. New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/20/health/dermatology-skin-cancer.html. Published November 20, 2017. Accessed February 25, 2019.

- 30.Ehrlich A, Kostecki J, Olkaba H. Trends in dermatology practices and the implications for the workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(4):746-752. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.06.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burwell SM. Setting value-based payment goals. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(10):897-899. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1500445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Database Search Strategy

eTable 2. Practice Acquisitions by State