Key Points

Question

Can deep natural language processing of radiologic reports be used to measure real-world oncologic outcomes, including disease progression and response to therapy?

Findings

In a cohort study of 2406 patients with lung cancer, the findings suggested that deep learning models may estimate human curations of the presence of active cancer, cancer worsening/progression, and cancer improvement/response in radiologic reports with good discrimination (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, >0.90). Statistically significant associations between these end points and overall survival were observed.

Meaning

Deep natural language processing may be able to extract clinically relevant oncologic end points from radiologic reports.

Abstract

Importance

A rapid learning health care system for oncology will require scalable methods for extracting clinical end points from electronic health records (EHRs). Outside of clinical trials, end points such as cancer progression and response are not routinely encoded into structured data.

Objective

To determine whether deep natural language processing can extract relevant cancer outcomes from radiologic reports, a ubiquitous but unstructured EHR data source.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A retrospective cohort study evaluated 1112 patients who underwent tumor genotyping for a diagnosis of lung cancer and participated in the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute PROFILE study from June 26, 2013, to July 2, 2018.

Exposures

Patients were divided into curation and reserve sets. Human abstractors applied a structured framework to radiologic reports for the curation set to ascertain the presence of cancer and changes in cancer status over time (ie, worsening/progressing vs improving/responding). Deep learning models were then trained to capture these outcomes from report text and subsequently evaluated in a 10% held-out test subset of curation patients. Cox proportional hazards regression models compared human and machine curations of disease-free survival, progression-free survival, and time to improvement/response in the curation set, and measured associations between report classification and overall survival in the curation and reserve sets.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) for deep learning models; secondary outcomes were time to improvement/response, disease-free survival, progression-free survival, and overall survival.

Results

A total of 2406 patients were included (mean [SD] age, 66.5 [10.8] years; 1428 female [59.7%]; 2170 [90.2%] white). Radiologic reports (n = 14 230) were manually reviewed for 1112 patients in the curation set. In the test subset (n = 109), deep learning models identified the presence of cancer, improvement/response, and worsening/progression with accurate discrimination (AUC >0.90). Machine and human curation yielded similar measurements of disease-free survival (hazard ratio [HR] for machine vs human curation, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.71-1.95); progression-free survival (HR, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.71-1.71); and time to improvement/response (HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.65-1.64). Among 15 000 additional reports for 1294 reserve set patients, algorithm-detected cancer worsening/progression was associated with decreased overall survival (HR for mortality, 4.04; 95% CI, 2.78-5.85), and improvement/response was associated with increased overall survival (HR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.22-0.77).

Conclusions and Relevance

Deep natural language processing appears to speed curation of relevant cancer outcomes and facilitate rapid learning from EHR data.

This cohort study examines the use of deep natural language processing in extraction of information on cancer outcomes from the medical records of patients with lung cancer.

Introduction

The US health care system rapidly incorporated electronic health records (EHRs) into routine clinical practice in the past decade.1 The large volume of information housed within EHRs can be viewed as evidence2 with the potential to drive cancer research and optimize oncologic care delivery. However, important clinical end points, such as response to therapy and disease progression, are often recorded in the EHR only as unstructured text. For patients in therapeutic clinical trials, standards such as the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST)3,4,5 provide clear guidelines for defining radiographic disease status. However, RECIST is not routinely applied outside of clinical trials. To create a true learning health system6 for oncology and facilitate delivery of precision medicine7 at scale, methods are needed to accelerate curation of cancer-related outcomes from EHRs8 according to validated standards.

We have developed a structured framework for curation of clinical outcomes among patients with solid tumors using medical records data (PRISSMM). PRISSMM considers each data source—including pathologic reports, radiologic/imaging reports, signs/symptoms, molecular markers, and medical oncologist assessment—independently.9 By maintaining a record of such data provenance through the curation process, a multidimensional representation of a patient’s clinical trajectory and outcomes, including disease-free survival (DFS) and progression-free survival (PFS), can be constructed.

Even within a structured framework, human medical records curation is resource intensive and often impractical. To accelerate the process of curating relevant clinical outcomes for patients with cancer, we applied deep learning to EHR curated by abstractors according to PRISSMM. We focused on text reports of imaging studies, which are ubiquitous and central to ascertainment of cancer progression and treatment response for patients with advanced solid tumors. Our hypothesis was that deep learning algorithms could use routinely generated radiologic text reports to identify the presence of any cancer, and, if cancer was present, identify shifts in disease burden and involved sites.

Methods

Cohort

The data for this analysis were derived from the EHRs of patients with lung cancer who had genomic profiling performed through the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) PROFILE10,11 precision medicine effort from June 26, 2013, to July 2, 2018. PROFILE participants consented to medical records review and genomic profiling of their tumor tissue. PROFILE was approved by the DFCI Institutional Review Board; this supplemental retrospective analysis was declared exempt from review also by the DFCI Institutional Review Board. Patients were included regardless of cancer stage at diagnosis, histologic findings (ie, small cell vs non–small cell lung cancer), or treatment history. Information on self-reported race/ethnicity is reported to inform assessment of generalizability.

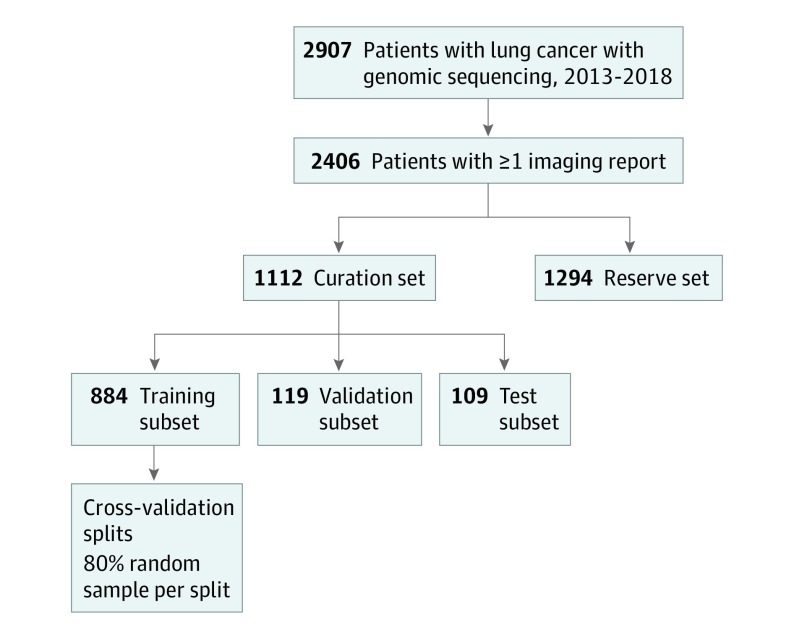

The cohort was restricted to PROFILE patients with lung cancer who had at least 1 report of a computed tomographic, magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomographic-computed tomographic, or nuclear medicine bone scan in our EHR. Manual curation for the cohort according to PRISSMM is ongoing; we conducted this analysis after records for approximately one-half of the PROFILE patients with lung cancer had been curated. Patients who had already undergone manual medical record review at the time of this analysis constituted the curation set. For deep learning model training, patients were further divided randomly, at the patient level, into training (80%), validation (10%), and test (10%) subsets12,13 (Figure 1); the number of patients in each curation subset approximated the proportions, because splitting was originally performed among all PROFILE patients. Patients who had not already undergone manual medical record review constituted the reserve set, which was used to conduct independent indirect validation of deep natural language processing models.

Figure 1. Cohort Derivation.

Derivation of curation set, curation subsets, and reserve set.

Medical Record Curation

Eight curators were trained to abstract data for the curation set according to the PRISSMM framework; details regarding curator training and interrater reliability are provided in eTable 1A in the Supplement.9 The present analysis focused on imaging reports. For each imaging study performed on or after the first pathologic report documenting lung cancer, curators evaluated whether each radiologic report indicated the presence of cancer; if cancer was present, whether the cancer was improving/responding, stable/no change, mixed, progressing/worsening/enlarging, or not stated/indeterminate in comparison with the previous scan; and the extent of cancer, focusing on common metastatic sites, including liver, adrenal gland, bone, lymph nodes, and brain/spine14 (eTable 1B in the Supplement). Data were collected using a REDCap database.15

Statistical Analysis

Within the curation set, deep natural language processing models were trained to determine whether imaging reports would be interpreted by human curators as demonstrating any evidence of cancer; improving/responding disease; worsening/progressive disease; and cancer present in specific extrapulmonary metastatic sites, including liver, bone, brain and/or spine, lymph nodes, and adrenal glands. Each of these 8 end points was treated as a binary outcome for a distinct model (eTable 1B in the Supplement). The model architecture treated each imaging report as a sequence of tokens, embedded into a vector space,16 and then fed into a 1-dimensional convolutional layer (eFigure 1 in the Supplement) to capture local interactions among nearby words.17 The dimensionality of each convolutional layer was then reduced using max-pooling.18 Pooling layer output was fed into fully connected layers to model global interactions among input words; this higher-level model architecture was designed to reflect intrinsic interdependence among outcomes. For example, the presence of cancer is required for response, progression, or disease at specific sites to be present, so the hidden layer for estimation of any cancer was concatenated to a specific hidden layer for each other outcome (eFigure 1B in the Supplement). Dropout was applied to hidden layers to improve generalizability.19 The final hidden layer output was fed into a sigmoid layer to generate a score that can be interpreted as the probability that a given imaging report was in a class of interest (eg, representing any evidence of cancer).

Model stability was assessed, and the optimal threshold probability for a positive outcome was defined by applying cross-validation to models trained within the 80% curation training subset; each of 5 cross-validation models was trained with a random 80% sample of the training data (ie, 64% of total curation data) and evaluated using the remaining 20% of the training data (ie, 16% of total curation data). The sigmoid activation layer output score for defining a predicted outcome as positive was defined as half of the mean best F1 scores calculated by cross-validation, where the F1 score is defined as the harmonic mean between precision and recall.20 For each outcome, an ensemble of the cross-validation models was constructed by taking the simple mean of the sigmoid activation layer outputs from each cross-validation model. The ensemble models were applied to the 10% validation subset for evaluation and iterative tuning. At the end of the analysis, the models were applied to the 10% final held-out test data set, after which no further training was performed. Using each imaging report as the unit of analysis and considering test subset human-curated outcomes to represent true labels, model performance was evaluated using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve.21 The area under the precision-recall curve, which measures the tradeoff between precision (positive predictive value) and recall (sensitivity) as well as the F1 score at the best F1 threshold, were also calculated. The local-interpretable model-agnostic explanation framework22 was applied to generate human-interpretable explanations of each classification.

Models were constructed using the Keras framework23 with the TensorFlow backend.24 Our free-text imaging reports constitute protected health information and are not publicly available, but the code used to train and evaluate the models is available on GitHub.25

To ascertain the face validity (clinical relevance) of machine-curated outcomes, we compared human and machine measurements of DFS, PFS, and time to improvement/response for curation set patients. Subgroups were defined as those who had early-stage disease at diagnosis, for evaluation of DFS, or received palliative-intent systemic therapy, for evaluation of PFS and time to improvement/response. Among patients with early-stage disease, we defined DFS as the time from initial diagnosis (regardless of upfront therapy) until death (ascertained via an institutional linkage to the National Death Index26 through December 31, 2017, and institutional administrative data thereafter) or the first imaging report indicating worsening/progression; patients were censored at the date of medical record abstraction or 180 days after their last imaging report, whichever came first. Among patients who received palliative-intent systemic therapy, we defined PFS as the time from initiation of first palliative-intent therapy until death or an imaging report indicating cancer worsening/progression, and time to improvement/response as the time from initiation of first palliative-intent systemic therapy to the first imaging report indicating improvement/response, subject to competing risks of death; patients were censored at the date of medical record abstraction or 90 days after their last imaging report, whichever came first. Time to these events using human vs machine curation was analyzed using Cox proportional hazards regression models, stratified by patient, with analysis of the cause-specific hazard in the competing risks case of time to improvement/response.

Next, we measured associations between cancer outcomes derived from machine curation of radiologic and overall survival. Because these analyses did not rely on manually curated medical record data, they were conducted among both curation set and reserve set patients. The intermediate outcomes serving as predictors in these models included the presence of any cancer, worsening/progression, and improvement/response. Analyses of cancer response or progression were restricted to imaging reports following initiation of a palliative-intent treatment plan. In addition, we used the curation set to measure the association between human abstractions of these end points in the curation set and overall survival. These associations were quantified using Cox proportional hazards regression models in which the curated intermediate outcomes on the most recent imaging report represented time-varying covariates with respect to the hazard of mortality; patients were censored on the data of data download or 90 days after each scan, whichever came first. Because genomic testing was required for inclusion in the cohort, a sensitivity analysis was performed in which only imaging reports that followed the genomic test order date were analyzed. Nominal, 2-sided P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Cohort

A total of 2406 patients were included (mean [SD] age, 66.5 [10.8] years; 1428 female [59.7%]; 2170 [90.2%] white). Radiologic reports (n = 14 230) were manually reviewed for 1112 patients in the curation set who underwent genomic sequencing from June 26, 2013, through July 2, 2018. These patients had 14 230 radiologic reports from our institution and affiliated sites available for analysis. A total of 884 patients (79.5%) were assigned to the training subset, 119 patients (10.7%) to the validation subset, and 109 patients (9.8%) to the final test subset for machine learning. The mean (SD) number of imaging reports per curated patient was 12.8 (12.0), over a mean of 26.0 (22.7) months. The reserve set, for whom manual curation has not yet been performed, included an additional 1294 patients, with 15 000 imaging reports. Patient and radiologic report characteristics in the curated and reserve sets were similar. For example, 71% to 74% of patients in the curation subsets and 75% of patients in the reserve set had adenocarcinoma (Table 1; eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Table 1. Cohort Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Subset, No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curation Set (n = 1112 Patients) | Reserve Set (n = 1294 Patients) | |||

| Training (n = 884) | Validation (n = 119) | Test (n = 109) | Total | |

| Histologic diagnosis | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 658 (74.4) | 84 (70.6) | 78 (71.6) | 968 (74.8) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 113 (12.8) | 17 (14.3) | 15 (13.8) | 136 (10.5) |

| Small cell lung cancer | 45 (5.1) | 3 (2.5) | 5 (4.6) | 37 (2.9) |

| Other | 68 (7.7) | 15 (12.6) | 11 (10.1) | 153 (11.8) |

| Disease extent at original diagnosis | ||||

| Early (stage I-III) | 544 (61.5) | 78 (65.5) | 70 (64.2) | NAa |

| Metastatic (stage IV) | 340 (38.5) | 41 (34.5) | 39 (35.8) | NAa |

| Age at genomic sequencing, y | ||||

| <50 | 55 (6.2) | 8 (6.7) | 8 (7.3) | 87 (6.7) |

| 50-59 | 189 (21.4) | 27 (22.7) | 22 (20.2) | 244 (18.9) |

| 60-69 | 301 (34.0) | 42 (35.3) | 39 (35.8) | 442 (34.2) |

| 70-79 | 250 (28.3) | 34 (28.6) | 31 (28.4) | 390 (30.1) |

| ≥80 | 89 (10.1) | 8 (6.7) | 9 (8.3) | 131 (10.1) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 359 (40.6) | 51 (42.9) | 47 (43.1) | 521 (40.3) |

| Female | 525 (59.4) | 68 (57.1) | 62 (56.9) | 773 (59.7) |

| Self-reported race | ||||

| White | 795 (89.9) | 106 (89.1) | 94 (86.2) | 1175 (90.8) |

| Asian | 28 (3.2) | 4 (3.4) | 6 (5.5) | 48 (3.7) |

| Black/African American | 30 (3.4) | 1 (0.8) | 6 (5.5) | 39 (3.0) |

| Unknown/declined/other | 31 (3.5) | 8 (6.7) | 3 (2.8) | 32 (2.5) |

Abbreviation: NA, not available.

Staging information was not available for reserve set patients, whose records have not been manually reviewed. The other available clinical and demographic data for the reserve set were collected through the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute precision medicine effort (PROFILE).

Deep Learning to Classify Imaging Reports

Deep learning model performance characteristics are provided in Table 2. Within the test subset of the curation set, the AUC for detection of any cancer was 0.92; for worsening/progression, 0.94; for improvement/response, 0.95; for liver lesions, 0.98; for bone lesions, 0.95; for brain/spine lesions, 0.97; for lymph node lesions, 0.89; and for adrenal lesions, 0.97. Graphic depictions of the receiver operating characteristic curve and the precision-recall curve are provided in eFigure 2 in the Supplement. Sample automated model explanations for high-probability individual predictions are provided in eFigure 3 in the Supplement. For example, words such as mass, tumor, and burden tended to indicate that cancer was present; words such as increasing and metastatic tended to indicate progressive disease; and words such as decrease tended to indicate improving disease in specific reports.

Table 2. Model Performance Characteristics in 14 230 Total Imaging Reports Among Curation Set Patientsa.

| Outcome (% of All Reports With Outcome) | Metric | Training Subset (11 182 Reports) | Validation Subset (1545 Reports) | Test Subset (1503 Reports) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV 1 | CV 2 | CV 3 | CV 4 | CV 5 | ||||

| Any cancer (61.7) | AUC | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.92 |

| Area under PR curve | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.94 | |

| Best F1 score | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.88 | |

| Worsening/progressing (24.7) | AUC | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.94 |

| Area under PR curve | 0.79 | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.78 | 0.83 | |

| Best F1 score | 0.74 | 0.79 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.78 | |

| Improving/responding (11.5) | AUC | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.95 |

| Area under PR curve | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.82 | |

| Best F1 score | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.70 | 0.72 | 0.76 | |

| Metastasis in liver (8.1) | AUC | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.98 |

| Area under PR curve | 0.83 | 0.73 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.76 | 0.74 | |

| Best F1 score | 0.78 | 0.73 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.71 | 0.71 | |

| Metastases in bone (17.3) | AUC | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.95 |

| Area under PR curve | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.74 | 0.75 | |

| Best F1 score | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.76 | |

| Metastases in brain/spine (8.3) | AUC | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.97 |

| Area under PR curve | 0.85 | 0.77 | 0.90 | 0.77 | 0.89 | 0.79 | 0.83 | |

| Best F1 score | 0.83 | 0.78 | 0.85 | 0.77 | 0.83 | 0.75 | 0.79 | |

| Metastases in lymph nodes (13.4) | AUC | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.82 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.89 |

| Area under PR curve | 0.54 | 0.45 | 0.47 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0.49 | |

| Best F1 score | 0.55 | 0.51 | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.53 | 0.55 | |

| Metastases in adrenal (4.7) | AUC | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.97 |

| Area under PR curve | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.68 | 0.82 | 0.69 | 0.73 | |

| Best F1 score | 0.70 | 0.77 | 0.72 | 0.64 | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.73 | |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; CV, cross-validation; F1 score, harmonic mean between precision and recall; PR, precision recall.

Cross-validation models, each of which was trained using a random sample of 80% of the training subset patients and evaluated using the remaining 20% of the training subset. Training subset patients were allowed into more than 1 cross-validation model.

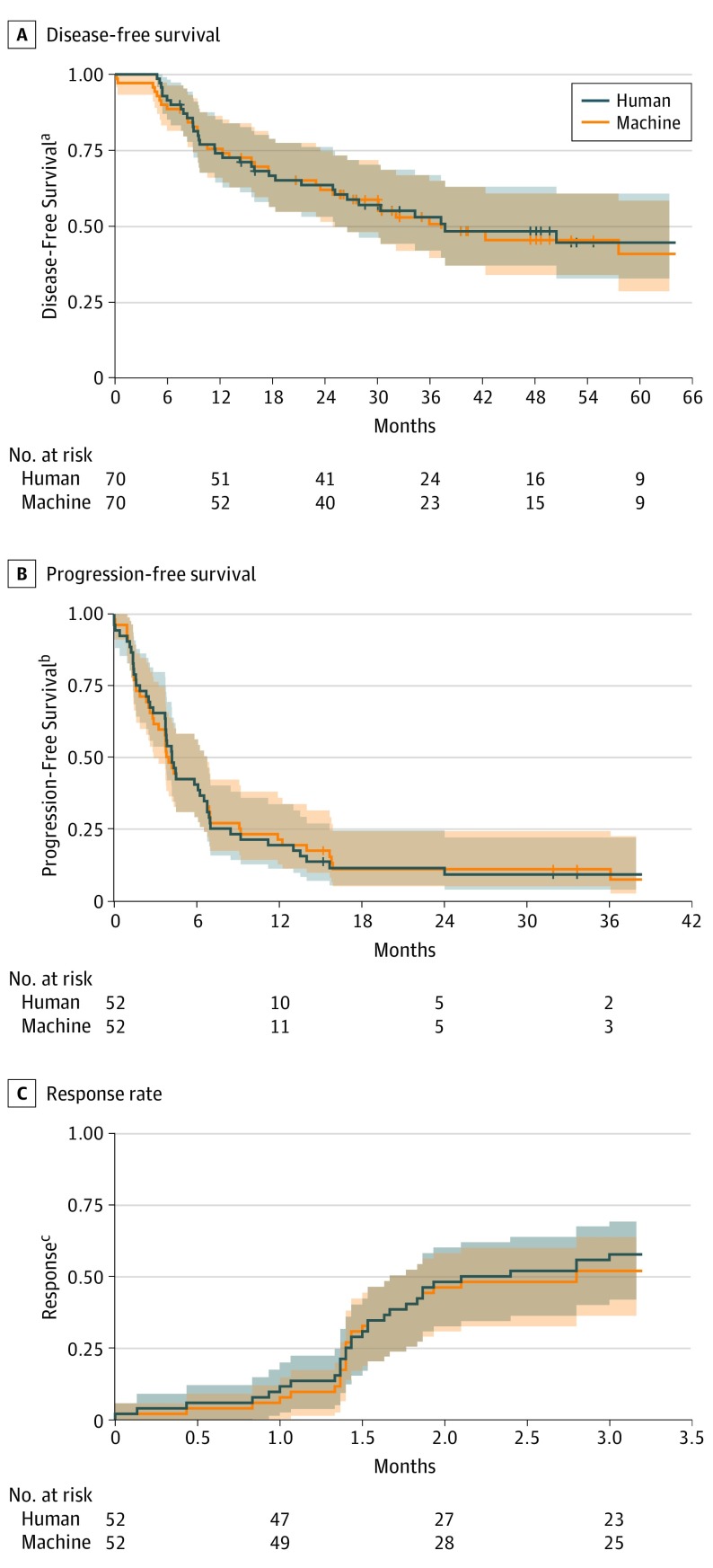

Face Validity of Machine-Curated End Points

Among patients with early-stage lung cancer in the curation set, machine and human curations of the time from diagnosis to disease recurrence or death (DFS) yielded similar results (hazard ratio [HR] in the test subset for machine vs human curation, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.71-1.95). Among patients who received palliative-intent systemic therapy, machine and human curations in the time from initiation of first palliative therapy to disease progression or death (PFS; HR in the test subset, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.71-1.71) or from initiation of first palliative therapy to improvement/response (HR in the test subset, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.65-1.64) also yielded similar results (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Comparison of Human and Machine Curation of Imaging Reports.

Shaded bands represent 95% CIs. The cumulative rate of response was calculated subject to competing risks of death. Disease-free survival was measured among patients with early-stage disease at diagnosis. The end point was defined as the time from diagnosis until death or the first imaging report curated as representing disease worsening/progression, whichever came first. Progression-free survival was measured among patients who received systemic therapy documented as palliative in intent. The end point was defined as the time from initiation of first palliative-intent systemic therapy at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute until death or the first imaging report indicating worsening/progressive disease, whichever came first. Response was measured among patients who received systemic therapy documented as palliative in intent. The end point was defined as the time from initiation of first palliative-intent systemic therapy at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute until the first imaging report indicating improving/responding disease, subject to competing risks of death.

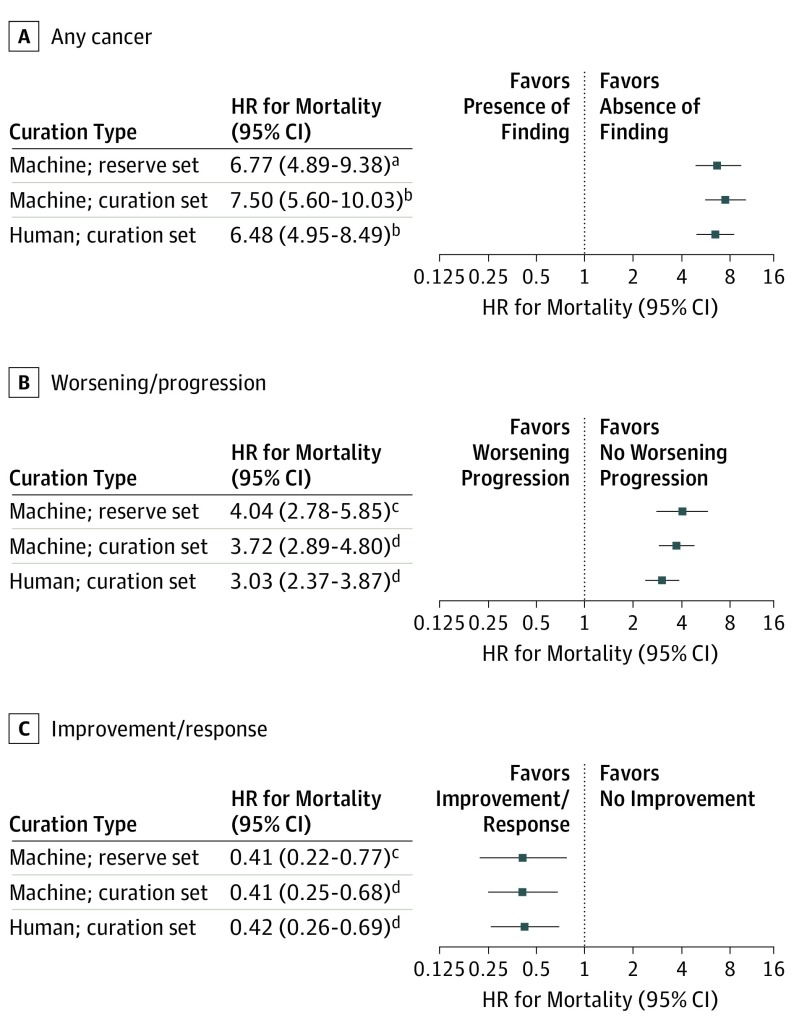

Within the separate reserve set of 1294 patients, whose records have not been manually curated, the HR for mortality associated with a report indicating active cancer per machine curation vs no active cancer was 6.77 (95% CI, 4.89-9.38). Among reserve set patients with radiologic reports for studies following initiation of palliative-intent systemic therapy, reports indicating worsening/progression per machine curation were associated with an increased risk of mortality (HR, 4.04; 95% CI, 2.78-5.85) vs reports indicating no worsening/progression, and reports indicating cancer improvement/response per machine curation were associated with a decreased risk of mortality (HR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.22-0.77) vs reports indicating no improvement/response (Figure 3). Results were similar in a sensitivity analysis restricted to imaging reports following a genomic testing order date (HR for any cancer, 6.15; 95% CI, 4.16-9.09; HR for worsening/progression, 3.43; 95% CI, 2.32-5.08; HR for improvement/response, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.20-0.79).

Figure 3. Association Between Machine-Curated Imaging Report Outcomes and Overall Survival.

All results were derived from Cox proportional hazards regression models in which the imaging finding was included as a time-varying covariate. Hazard ratios therefore represent the relative hazard of mortality at any given time if a particular imaging finding was present on the most recent prior scan vs if it was not. In models analyzing the outcome of any cancer, the presence of cancer on an imaging report was the sole independent variable. In models analyzing the outcome of response and progression, each was included as a binary variable.

aCohort included 1294 reserve set patients (with imaging reports on 11 946 dates predating survival cutoff) who did not undergo human curation but for whom overall survival data were available. Survival time was indexed at the date of the first imaging report available.

bCohort included 1112 curation set patients (with imaging reports on 11 091 dates predating survival cutoff) who underwent human and machine curation. Survival time was indexed at the date of the first imaging report available.

cCohort included 395 reserve set patients (with imaging reports on 4092 dates preceding survival cutoff) who did not undergo human curation but for whom overall survival data were available and initiated a treatment plan recorded as palliative in intent. Survival time was indexed at the date of first palliative-intent systemic therapy.

dCohort included 501 curation set patients (with imaging reports on 4941 dates predating survival cutoff) who underwent human and machine curation and initiated a treatment plan recorded as palliative in intent. Survival time was indexed at the date of first palliative-intent systemic therapy.

Discussion

These results suggest that deep natural language processing, trained using the structured PRISSMM framework for curation of real-world cancer outcomes, can rapidly extract clinically relevant outcomes from the text of radiologic reports. Our human curators can annotate imaging reports for approximately 3 patients per hour; at that rate, it would take 1 curator approximately 6 months to annotate all imaging reports for the patients with lung cancer in our cohort. Once trained, the models that we developed could annotate imaging reports for the entire lung cancer cohort in approximately 10 minutes. By reducing the time and expense necessary to review medical records, this technique could substantially accelerate efforts to use real-world data from all patients with cancer to generate evidence regarding effectiveness of treatment approaches and guide decision support.

For example, rapid ascertainment of cancer outcomes using machine learning could specifically improve the utility of large-scale genomic data for precision medicine efforts.27,28 In trials of broad next-generation sequencing, most participants in such studies have not enrolled in genotype-matched therapeutic trials.29,30,31,32 However, oncology clinical trials often close without reaching their accrual goals.33,34 Methods are needed to identify patients who are eligible for trials at the time when they have progressive disease and are in need of a new therapy. Scalable techniques for extracting outcome data from EHRs could be incorporated into decision support tools for matching patients to targeted therapies at appropriate times in their disease trajectories.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study included the application of deep natural language processing to the challenge of extracting clinically relevant end points from EHRs using techniques that have previously been applied more often to sentiment analysis problems in nonmedical fields.35 Prior efforts to apply natural language processing techniques to measure oncologic outcomes36 have not leveraged recent rapid innovation in deep learning.8,37,38 Deep learning confers specific advantages, including facilitating subsequent transfer learning,39 in which components of previously trained models can be repurposed to perform related tasks using fewer data than might otherwise be required. We also incorporated a method22 for explaining individual deep learning model predictions into our analysis. This method evaluates the effect on local model predictions of slight alterations to input data for individual observations, enabling the text most important for a specific prediction, which may vary among observations, to be highlighted. This model explanation framework addresses a common criticism of deep learning models, particularly in health care—that nonlinear, black box40 models fail to yield the interpretability necessary for clinicians and researchers to trust model predictions. In addition, the labeled data for the analysis were generated using the open PRISSMM framework, which relies on publicly available, tumor site-agnostic data standards to improve reproducibility. This technique enabled the derivation of structured outcome data without requiring that radiologists generate information directly by clicking additional buttons in the EHR, which can be a tedious, error-prone process.41

This study has limitations, including the single-institution design, conducted among patients with one type of cancer. Models trained using EHR data from a single tertiary care institution may not perform as well in other institutions or practice settings. However, if multiple institutions and practices were to share their unstructured data for additional model training, or even implement distributed training without requiring that raw protected health information be shared,42 generalizability could be evaluated and optimized. The present study also ascertained cancer outcomes using only imaging reports. Some clinically important end points may be evaluable only within other components of the EHR, including laboratory test results, physical examination, symptoms, and oncologists’ impressions. Further research is needed to extract reproducible end points based on these additional EHR data sources. In addition, real-world clinical reports often communicate true clinical uncertainty about a finding at any given time. This underlying uncertainty likely explains the somewhat lower performance of our models for certain end points, such as the presence or absence of cancer in lymph nodes. Further work is needed to explicitly incorporate measures of uncertainty into model predictions.

Our real-world end points specifically do not attempt to replicate the RECIST criteria traditionally used to evaluate responses to treatment in clinical trials. Using the PRISSMM framework, disease response and progression do not require attainment of specific relative changes in tumor diameter, as would be the case for RECIST measurements. Raw response rates as defined by PRISSMM therefore cannot be directly compared with objective response rates defined by RECIST criteria. However, in our study, PRISSMM response and progression were associated with expected shifts in mortality risk along the disease trajectory.

Deep learning techniques for image analysis are advancing rapidly; an alternative approach to this work could be to train models to replicate human labels using radiologic images rather than radiologist-generated text interpretations of those images. However, training such a model to accurately discern malignant disease and identify changes in that disease might require substantially more data and computing resources. Analyzing the radiologic reports effectively leverages the clinical expertise of radiologists to reduce the dimensionality of raw images into a text report for analysis, constituting a form of human to machine transfer learning.

Conclusions

Automated collection of clinically relevant, real-world cancer outcomes from unstructured EHRs appears to be feasible. This technique has the potential to augment capacity for learning from the large population of patients with cancer who receive care outside the clinical trial context. Key next steps will include testing this approach in other health care systems and clinical contexts and applying it to evaluate associations among tumor profiles, therapeutic exposures, and oncologic outcomes.

eTable 1A. Human Curator Training, Abstraction Process, and Interrater Reliability

eTable 1B. Data Collection Instruments for Human Curation of Cancer Status Within Each Radiology Report

eTable 2. Characteristics of Radiology Reports

eFigure 1. Deep Learning Model Architectures for Imaging Report Interpretation

eFigure 2. Graphical Depictions of Model Performance

eFigure 3. LIME Explanations for Individual Model Predictions

References

- 1.Washington V, DeSalvo K, Mostashari F, Blumenthal D. The HITECH Era and the path forward. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(10):904-906. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1703370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sherman RE, Anderson SA, Dal Pan GJ, et al. Real-world evidence—what is it and what can it tell us? N Engl J Med. 2016;375(23):2293-2297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1609216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller AB, Hoogstraten B, Staquet M, Winkler A. Reporting results of cancer treatment. Cancer. 1981;47(1):207-214. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228-247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(3):205-216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine The Learning Healthcare System: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins FS, Varmus H. A new initiative on precision medicine. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):793-795. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1500523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naylor CD. On the prospects for a (deep) learning health care system. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1099-1100. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.11103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schrag D. GENIE: Real-world application. In: ASCO Annual Meeting; Chicago; June 4, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacConaill LE, Garcia E, Shivdasani P, et al. Prospective enterprise-level molecular genotyping of a cohort of cancer patients. J Mol Diagn. 2014;16(6):660-672. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2014.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sholl LM, Do K, Shivdasani P, et al. Institutional implementation of clinical tumor profiling on an unselected cancer population. JCI Insight. 2016;1(19):e87062. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.87062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saeb S, Lonini L, Jayaraman A, Mohr DC, Kording KP. The need to approximate the use-case in clinical machine learning. Gigascience. 2017;6(5):1-9. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/gix019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James G, Witten D, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning: With Applications in R. New York: Springer Publishing Co, Inc; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsu F, De Caluwe A, Anderson D, Nichol A, Toriumi T, Ho C. Patterns of spread and prognostic implications of lung cancer metastasis in an era of driver mutations. Curr Oncol. 2017;24(4):228-233. doi: 10.3747/co.24.3496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keras Documentation. Embedding layers. https://keras.io/layers/embeddings/. Accessed March 13, 2019.

- 17.LeCun Y. Generalization and network design strategies. In: Pfeifer R, Schreter Z, Fogelman F, Steels L, eds. Connectionism in Perspective. Zurich, Switzerland; Elsevier; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou Y-T, Chellappa R Computation of optical flow using a neural network. In: IEEE International Conference on Neural Networks. 1988(1998):71-78. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Srivastava N, Hinton G, Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Salakhutdinov R. Dropout: a simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. J Mach Learn Res. 2014;15:1929-1958. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lipton ZC, Elkan C, Naryanaswamy B. Optimal thresholding of classifiers to maximize F1 measure. Mach Learn Knowl Discov Databases. 2014;8725:224-239. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-44851-9_15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mandrekar JN. Receiver operating characteristic curve in diagnostic test assessment. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(9):1315-1316. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181ec173d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ribeiro M, Singh S, Guestrin C “Why should i trust you?”: explaining the predictions of any classifier. In: Proceedings of the 2016 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Demonstrations. Stroudsburg, PA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2016:97-101. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keras Documentation. https://keras.io. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- 24.Abadi M, Agarwal A, Barham P, et al. TensorFlow: large-scale machine learning on heterogeneous distributed systems. Preprint. Posted online March 16, 2016. arXiv:1603.04467

- 25.GitHub Inc https://github.com/prissmmnlp/prissmm_imaging_nlp. Created March 18, 2019.

- 26.Curtis MD, Griffith SD, Tucker M, et al. Development and validation of a high-quality composite real-world mortality endpoint. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(6):4460-4476. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoadley KA, Yau C, Wolf DM, et al. ; Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network . Multiplatform analysis of 12 cancer types reveals molecular classification within and across tissues of origin. Cell. 2014;158(4):929-944. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.AACR Project GENIE Consortium AACR Project GENIE: Powering precision medicine through an international consortium. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(8):818-831. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Presley CJ, Tang D, Soulos PR, et al. Association of broad-based genomic sequencing with survival among patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer in the community oncology setting. JAMA. 2018;320(5):469-477. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.9824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stockley TL, Oza AM, Berman HK, et al. Molecular profiling of advanced solid tumors and patient outcomes with genotype-matched clinical trials: the Princess Margaret IMPACT/COMPACT trial. Genome Med. 2016;8(1):109. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0364-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meric-Bernstam F, Brusco L, Shaw K, et al. Feasibility of Large-Scale Genomic Testing to Facilitate Enrollment Onto Genomically Matched Clinical Trials. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(25):2753-2762. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.4165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Le Tourneau C, Delord J-P, Gonçalves A, et al. ; SHIVA investigators . Molecularly targeted therapy based on tumour molecular profiling versus conventional therapy for advanced cancer (SHIVA): a multicentre, open-label, proof-of-concept, randomised, controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(13):1324-1334. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00188-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nass SJ, Moses HL, Mendelsohn J, eds. A National Cancer Clinical Trials System for the 21st Century: Reinvigorating the NCI Cooperative Group Program. Committee on Cancer Clinical Trials and the NCI Cooperative Group Program. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academies Press; 2010. doi: 10.17226/12879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schroen AT, Petroni GR, Wang H, et al. Achieving sufficient accrual to address the primary endpoint in phase III clinical trials from US Cooperative Oncology Groups. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(1):256-262. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nasukawa T, Yi J Sentiment analysis. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Capture—K-CAP ’03. New York, New York: ACM Press; 2003:70. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mullard A. Learning from exceptional drug responders. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13(6):401-402. doi: 10.1038/nrd4338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hinton G. Deep learning—a technology with the potential to transform health care. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1101-1102. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.11100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stead WW. Clinical implications and challenges of artificial intelligence and deep learning. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1107-1108. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.11029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pan SJ, Yang Q. A survey on transfer learning. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2010;22:1345-1359. doi: 10.1109/TKDE.2009.191 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dayhoff JE, DeLeo JM. Artificial neural networks: opening the black box. Cancer. 2001;91(8)(suppl):1615-1635. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ratwani RM, Savage E, Will A, et al. A usability and safety analysis of electronic health records: a multi-center study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(9):1197-1201. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocy088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li X, Fireman BH, Curtis JR, et al. Privacy-protecting analytical methods using only aggregate-level information to conduct multivariable-adjusted analysis in distributed data networks. Am J Epidemiol. 2019;188(4):709-723. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwy265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1A. Human Curator Training, Abstraction Process, and Interrater Reliability

eTable 1B. Data Collection Instruments for Human Curation of Cancer Status Within Each Radiology Report

eTable 2. Characteristics of Radiology Reports

eFigure 1. Deep Learning Model Architectures for Imaging Report Interpretation

eFigure 2. Graphical Depictions of Model Performance

eFigure 3. LIME Explanations for Individual Model Predictions