Key Points

Question

What drives variation in high-intensity statin use after acute myocardial infarction among older adults?

Findings

In this cohort study of 139 643 Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries hospitalized for myocardial infarction, postdischarge high-intensity statin use increased from 23.4% in 2011 to 55.6% in 2015. In multivariable-adjusted models, geographic region was more strongly associated with high-intensity statin use after myocardial infarction than hospital or patient characteristics.

Meaning

These findings suggest that large geographic treatment disparities in high-intensity statin use after myocardial infarction are poorly understood and require further research and intervention.

This cohort analysis explores the relative strength of associations of region and hospital and patient characteristics with high-intensity statin use after myocardial infarction in a population of fee-for-service US Medicare beneficiaries.

Abstract

Importance

High-intensity statin use after myocardial infarction (MI) varies by patient characteristics, but little is known about differences in use by hospital or region.

Objective

To explore the relative strength of associations of region and hospital and patient characteristics with high-intensity statin use after MI.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cohort analysis used Medicare administrative claims and enrollment data to evaluate fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries 66 years or older who were hospitalized for MI from January 1, 2011, through June 30, 2015, with a statin prescription claim within 30 days of discharge. Data were analyzed from January 4, 2017, through May 12, 2019.

Exposures

Beneficiary characteristics were abstracted from Medicare data. Hospital characteristics were obtained from the 2014 American Hospital Association Survey and Hospital Compare quality metrics. Nine regions were defined according to the US Census.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Intensity of the first statin claim after discharge characterized as high (atorvastatin calcium, 40-80 mg, or rosuvastatin calcium, 20-40 mg/d) vs low to moderate (all other statin types and doses). Trends in high-intensity statins were examined from 2011 through 2015. Associations of region and beneficiary and hospital characteristics with high-intensity statin use from January 1, 2014, to June 15, 2015, were examined using Poisson distribution mixed models.

Results

Among the 139 643 fee-for-service beneficiaries included (69 968 men [50.1%] and 69 675 women [49.9%]; mean [SD] age, 76.7 [7.5] years), high-intensity statin use overall increased from 23.4% in 2011 to 55.6% in 2015, but treatment gaps persisted across regions. In models considering region and beneficiary and hospital characteristics, region was the strongest correlate of high-intensity statin use, with 66% higher use in New England than in the West South Central region (risk ratio [RR], 1.66; 95% CI, 1.47-1.87). Hospital size of at least 500 beds (RR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.07-1.23), medical school affiliation (RR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.05-1.17), male sex (RR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.07-1.13), and patient receipt of a stent (RR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.31-1.39) were associated with greater high-intensity statin use. For-profit hospital ownership, patient age older than 75 years, prior coronary disease, and other comorbidities were associated with lower use.

Conclusions and Relevance

This study’s findings suggest that geographic region is the strongest correlate of high-intensity statin use after MI, leading to large treatment disparities.

Introduction

High-intensity statin therapy is a class IA indication after myocardial infarction (MI) for individuals 75 years or younger in the absence of safety and tolerability concerns; moderate-intensity statin therapy is recommended for most individuals older than 75 years.1,2 Use of high-intensity statins after MI compared with use of lower-intensity statins decreases rates of non-fatal MI, deaths due to coronary heart disease, and ischemic stroke in randomized clinical trials.3 The proportion of US adults taking high-intensity statins after MI has increased in recent years, but this therapy remains underused.4

For many years, regional variation in care processes and health outcomes across the United States have been documented for cardiovascular diseases and many other health conditions.5 Between-facility variation in statin use has been found within hospital registries such as the Get with the Guidelines Registry,6 among Veterans Administration hospitals,7 and in registries of clinical outpatient practices.8,9 Also, variation in high-intensity statin use associated with patient characteristics10,11 and regional variation in pharmacy performance related to statin use have been reported.12 The goal of the present study was to describe variation in high-intensity statin use by geographic region and explore the relative contributions of geographic region and hospital and patient characteristics in a contemporary cohort of patients discharged after an MI.

Methods

Study Population

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of US adults with fee-for-service Medicare coverage who were hospitalized for MI. Hospitalizations for MI were identified as inpatient claims with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, primary discharge diagnosis of 410.xx, except 410.x2.13 Medicare data do not capture information on medications when the beneficiary pays out of pocket. Therefore, in the primary analysis, we required beneficiaries to have a claim for a statin within 30 days of hospital discharge. For analysis of trends in high-intensity statin use over time, we included Medicare beneficiaries who were hospitalized for MI from January 1, 2011, through June 30, 2015 (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). For analysis of characteristics associated with high-intensity statin use, we included Medicare beneficiaries who were hospitalized for MI from January 1, 2014, through June 30, 2015 (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). We further required that beneficiaries (1) were 66 years or older on the day of discharge; (2) had a hospital length of stay of at least 1 night and no more than 30 days; (3) survived for at least 30 days after discharge; (4) had full fee-for-service Medicare coverage during the hospitalization, the year before the hospitalization, and the 30 days after hospitalization; (5) were not in a skilled nursing facility or hospice care during the 30 days after hospitalization; (6) did not have end-stage heart failure or end-stage renal disease; (7) had a claim for a statin within 30 days of discharge; (8) were treated for their MI in hospitals with available data from the 2014 American Hospital Association Survey14 and the 2014 Hospital Compare metrics15; and (9) received care at hospitals that had at least 10 beneficiaries 75 years or younger and at least 10 beneficiaries older than 75 years. In sensitivity analyses, we included beneficiaries with and without statin claims within 30 days after discharge. Further explanation of the inclusion and exclusion criteria is provided in the eMethods in the Supplement. After all inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, 139 643 beneficiaries treated in 1437 hospitals were included in the analysis of trends. For analysis of characteristics associated with high-intensity statin use, 42 962 beneficiaries treated in 833 hospitals were included, representing 23.7% of potentially eligible beneficiaries with hospitalizations for MI (range, 20.8% in the Pacific region to 27.6% in the East South Central region) (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

The institutional review board of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Privacy Board approved this research. A waiver of informed consent was granted for the use of deidentified data. Race/ethnicity is reported as recorded in Medicare enrollment data and is included in these analyses owing to its importance in treatment disparities. Data required to replicate this research are available from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.

Region and Hospital Characteristics

Using Medicare provider numbers, we linked the beneficiaries’ claims data to the 2014 American Hospital Association Survey and the 2014 Hospital Compare quality metrics. From these data sources, we selected characteristics that may be related to posthospitalization use of high-intensity statins. Information on hospital ownership type (non–federal government, not-for-profit, or for profit), hospital size (<100, 100-199, 200-299, 300-399, 400-499, or ≥500 beds), metropolitan area (yes or no), and medical school affiliation (yes or no) were obtained from the American Hospital Association Survey. From the Hospital Compare metrics, we obtained information on post-MI 30-day readmission rates, post-MI 30-day mortality rates, overall hospital rating, patient satisfaction, and 30-day risk-adjusted overall posthospitalization mortality comparison, all expressed as above or equal to the median vs below the median. In addition, we identified the US Census region for each hospital (East South Central, Mountain, West South Central, Middle Atlantic, South Atlantic, West North Central, East North Central, Pacific, or New England) (eFigure 3 in the Supplement).

Beneficiary Characteristics

From the Medicare enrollment files, we identified each beneficiary’s age, sex, race/ethnicity, and low-income status, defined as dual enrollment in Medicare and Medicaid or eligibility for a Part D subsidy. From the claims in the year before the hospitalization, we identified prior coronary heart disease, diabetes, stroke, heart failure, dementia, chronic kidney disease, and cancer. We additionally identified claims for skilled nursing facility stays and hospitalizations in the year before the hospitalization for the MI. We used the MI hospitalization claims to determine whether a beneficiary had a new diagnosis of heart failure and whether the beneficiary had a coronary stent placed during the hospitalization.

Statin Intensity

Beneficiaries were required to have a prescription claim for a statin within 30 days of discharge after their MI hospitalization in the primary analysis. Statin intensity was assessed for the first statin claim after discharge. In accordance with the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines for the treatment of cholesterol levels, we considered doses of 40 to 80 mg of atorvastatin calcium and 20 to 40 mg of rosuvastatin calcium to be high-intensity statins.1 All other statins and doses were considered of low to moderate intensity.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed from January 4, 2017, through May 12, 2019. We calculated the frequency of hospital and individual characteristics among beneficiaries whose first statin claim after discharge for an MI was high intensity vs low or moderate intensity. We then calculated the percentage of beneficiaries whose first statin claim after discharge was for a high-intensity statin over time. To test whether a statistically significant variation occurred across regions from 2011 to 2015, we used Poisson distribution mixed models with hospital-specific random intercepts and region-specific fixed effects. To evaluate whether the variation across regions differed over time, we added a region by calendar year interaction term. Among beneficiaries hospitalized for MI from 2014 to 2015, we used Poisson distribution mixed models with hospital-specific random intercepts to calculate adjusted risk ratios (RRs) for high-intensity statin use. Initial models included the region and hospital characteristics and the individual characteristics separately. In subsequent models, all these characteristics were included in a single model.

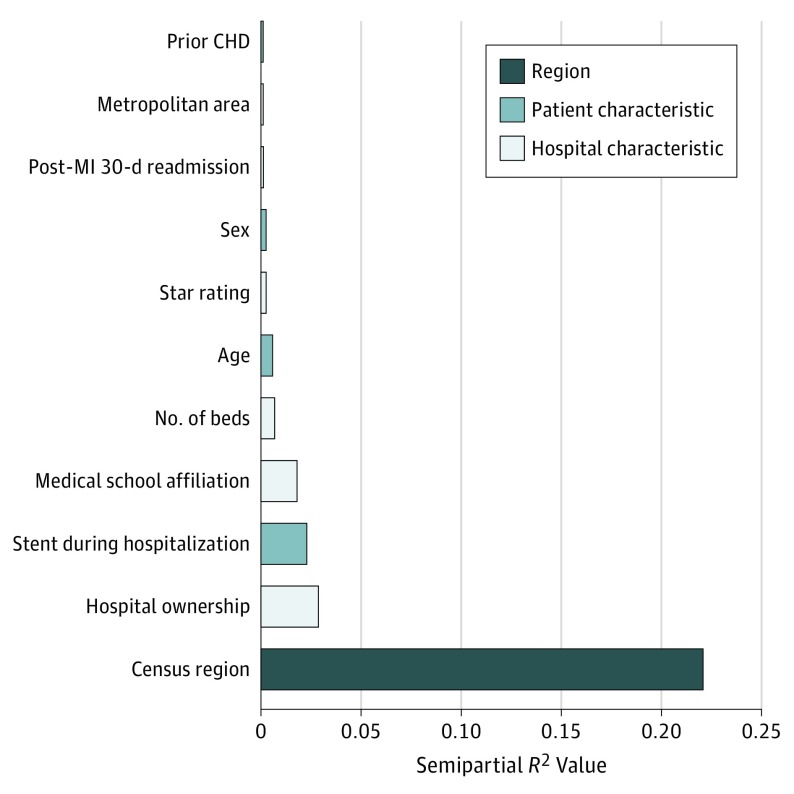

Because the models included variables with different scales and variables with multiple categories, the magnitude of the RRs cannot be directly compared. We therefore calculated semipartial R2 values, a function of the χ2 statistics, for each of the independent variables included in the fully adjusted models.16 The semipartial R2 values measure the relative contribution of individual independent variables to the model, adjusted for the contribution of the other independent variables in the model, with higher values indicating greater contribution. Calculation of the semipartial R2 values allows direct comparison of the relative contribution of individual variables to the overall R2 value, which measures the multivariate association between the full set of independent variables and the outcome. Multivariate association ranges from 0 to 1, indicating a worthless and a perfect model, respectively. For categorical variables (eg, region), we summed the semipartial R2 statistics for each level to estimate the overall semipartial R2 value.

Because the recommendation for use of high-intensity statins after MI is stronger for individuals 75 years or younger than for individuals older than 75 years,1,2 we stratified the analyses by these age groups. In previous investigations, receipt of high-intensity statin therapy before a hospitalization for MI was strongly associated with high-intensity statin therapy after the index hospitalization.4 As sensitivity analyses, we repeated the analyses described above for patients who did not take high-intensity statins before their index MI. In addition, we repeated the analyses without requiring a statin claim within 30 days of discharge. All analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc). Two-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Regional Variation in High-Intensity Statin Use Over Time

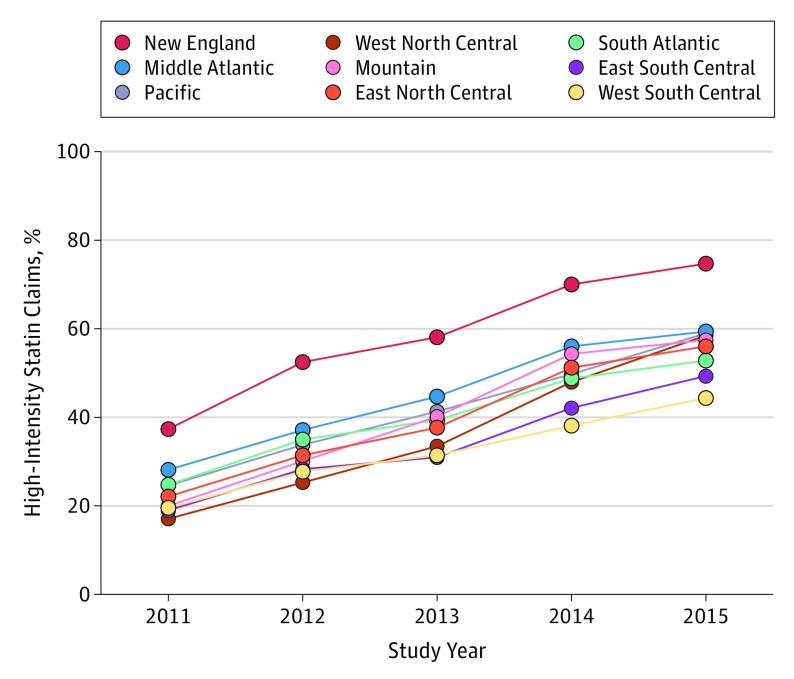

Among the 139 643 fee-for-service beneficiaries (69 968 men [50.1%] and 69 675 women [49.9%]; mean [SD] age, 76.7 [7.5] years), the percentage of Medicare beneficiaries with a high-intensity statin claim after a hospitalization for MI increased from 23.4% in 2011 to 55.6% in 2015. The percentage with high-intensity statin claims increased across all strata defined by region, hospital characteristics, and patient characteristics (eTables 2 and 3 in the Supplement). In 2011, the use of high-intensity statins varied from 17.0% in the West North Central region to 37.3% in New England (P < .001 for variation across regions) (Figure 1). The West North Central region had the greatest increase in high-intensity statin use (from 17.0% in 2011 to 58.4% in 2015), and the West South Central region had the smallest increase (from 19.6% in 2011 to 44.3% in 2015) (P < .001 for interaction between region and time). In 2015, the West South Central region had the lowest use of high-intensity statins (44.3%) whereas New England had the highest (74.6%) (P < .001 for variation across regions).

Figure 1. Percentage of Medicare Beneficiaries With a High-Intensity Statin Claim by US Census Region and Year.

The graph depicts the percentage of Medicare beneficiaries with claims for high-intensity statins (40 to 80 mg of atorvastatin calcium or 20 to 40 mg of rosuvastatin calcium) among those with a statin claim within 30 days of discharge after a hospitalization for myocardial infarction, by study year. Rates increased over time in all regions, but disparities in rates of use by region persist (P < .001 for variation across region in 2011 and in 2015).

Correlates of High-Intensity Statin Use in 2014-2015

Characteristics and Geographic Location of Institutions

Hospital characteristics by high-intensity statin claims after MI among Medicare beneficiaries (2014-2015) are shown in Table 1, and multivariable-adjusted modeling is shown in eTable 4 in the Supplement. Beneficiaries residing in New England were most likely to be treated with high-intensity statins after MI (1861 [73.5%]), whereas those in the West South Central region were least likely to receive high-intensity statins (1703 [40.6%]). Non–federal government ownership (2136 [54.1%]), larger hospital size (9498 [58.6%] for hospitals with at least 500 beds), and medical school affiliation (15 533 [56.4%]) were associated with a greater likelihood of claims for high-intensity statin therapy. High-intensity statin claims did not differ by metropolitan area or Hospital Compare metrics.

Table 1. Medicare Beneficiaries With High-Intensity and Low- or Moderate-Intensity Statin Claims After MI by Geographic Region, Hospital Characteristics, and Hospital Compare Quality Metrics, 2014-2015.

| Hospital Characteristics | Beneficiaries, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| High-Intensity Statin Claim | Low- or Moderate-Intensity Statin Claim | |

| Geographic region | ||

| West South Central | 1703 (40.6) | 2487 (59.4) |

| Mountain | 1128 (55.4) | 907 (44.6) |

| East South Central | 1790 (44.0) | 2275 (56.0) |

| Middle Atlantic | 3908 (57.2) | 2928 (42.8) |

| South Atlantic | 4571 (50.8) | 4431 (49.2) |

| West North Central | 1615 (52.1) | 1485 (47.9) |

| East North Central | 3976 (53.1) | 3515 (46.9) |

| Pacific | 2018 (54.4) | 1692 (45.6) |

| New England | 1861 (73.5) | 672 (26.5) |

| Hospital ownership | ||

| Non-federal government | 2136 (54.1) | 1814 (45.9) |

| Not for profit | 18 429 (54.0) | 15 671 (46.0) |

| Profit | 2005 (40.8) | 2907 (59.2) |

| Hospital size, No. of beds | ||

| <100 | 274 (38.6) | 435 (61.4) |

| 100-199 | 1958 (50.5) | 1921 (49.5) |

| 200-299 | 3607 (48.2) | 3884 (51.8) |

| 300-399 | 4303 (47.6) | 4731 (52.4) |

| 400-499 | 2930 (51.8) | 2721 (48.2) |

| ≥500 | 9498 (58.6) | 6700 (41.4) |

| Metropolitan area | ||

| No | 1143 (49.7) | 1156 (50.3) |

| Yes | 21 427 (52.7) | 19 236 (47.3) |

| Medical school affiliation | ||

| No | 7037 (45.6) | 8382 (54.4) |

| Yes | 15 533 (56.4) | 12 010 (43.6) |

| Hospital Compare Quality Metrics | ||

| Hospital post-MI 30-d readmissiona | ||

| Above or equal to median | 11 370 (52.8) | 10 148 (47.2) |

| Below median | 11 200 (52.2) | 10 244 (47.8) |

| Hospital post-MI 30-d mortalityb | ||

| Above or equal to median | 11 138 (50.7) | 10 827 (49.3) |

| Below median | 11 432 (54.4) | 9565 (45.6) |

| Hospital star ratingc | ||

| Above or equal to median | 15 990 (52.3) | 14 582 (47.7) |

| Below median | 6580 (53.1) | 5810 (46.9) |

| Hospital patient satisfactionc | ||

| Above or equal to median | 19 082 (52.7) | 17 099 (47.3) |

| Below median | 3488 (51.4) | 3293 (48.6) |

| Overall 30-d risk-adjusted posthospitalization mortality | ||

| Above or equal to median | 17 938 (53.0) | 15 894 (47.0) |

| Below median | 4632 (50.7) | 4498 (49.3) |

Abbreviation: MI, myocardial infarction.

Median is 16.8.

Median is 13.5.

Median is 3.

Characteristics of Beneficiaries

Beneficiary characteristics by high-intensity statin claims after MI among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for MI in 2014 to 2015 are shown in Table 2, with multivariable modeling presented in eTable 5 in the Supplement. Individuals 75 years or younger (12 481 of 21 575 [57.8%]), men (12 656 of 22 619 [56.0%]), and those who received a stent during their index hospitalization (14 929 of 24 968 [59.8%]) were more likely to have a high-intensity statin claim. In contrast, individuals with comorbidities including prior coronary heart disease (7198 of 15 099 [47.7%]), prior heart failure (2962 of 6758 [43.8%]), and history of dementia (830 of 2065 [40.2%]) and those with a hospitalization in the year before the index MI (5226 of 11 198 [46.7%]) were less likely to have a high-intensity statin claim than their counterparts without these characteristics.

Table 2. Medicare Beneficiaries With High-Intensity Statin Claims After MI by Patient Characteristics, 2014-2015.

| Characteristic | Beneficiaries, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| High-Intensity Statin Claim | Low- to Moderate-Intensity Statin Claim | |

| Age, y | ||

| ≤75 | 12 481 (57.8) | 9094 (42.2) |

| >75 | 10 089 (47.2) | 11 298 (52.8) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 12 656 (56.0) | 9963 (44.0) |

| Female | 9914 (48.7) | 10 429 (51.3) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 19 841 (52.5) | 17 973 (47.5) |

| Black | 1553 (53.6) | 1347 (46.4) |

| Asian | 330 (52.0) | 305 (48.0) |

| Hispanic | 296 (46.5) | 341 (53.5) |

| Other | 550 (56.4) | 426 (43.6) |

| Low-income status | ||

| No | 16 942 (53.1) | 14 935 (46.9) |

| Yes | 5628 (50.8) | 5457 (49.2) |

| Prior CHD | ||

| No | 15 372 (55.2) | 12 491 (44.8) |

| Yes | 7198 (47.7) | 7901 (52.3) |

| Diabetes | ||

| No | 14 591 (53.5) | 12 698 (46.5) |

| Yes | 7979 (50.9) | 7694 (49.1) |

| Stroke | ||

| No | 22 128 (52.8) | 19 820 (47.2) |

| Yes | 442 (43.6) | 572 (56.4) |

| Prior heart failure | ||

| No | 19 608 (54.2) | 16 596 (45.8) |

| Yes | 2962 (43.8) | 3796 (56.2) |

| New heart failure | ||

| No | 16 295 (54.1) | 13 804 (45.9) |

| Yes | 6275 (48.8) | 6588 (51.2) |

| Dementia | ||

| No | 21 740 (53.2) | 19 157 (46.8) |

| Yes | 830 (40.2) | 1235 (59.8) |

| Chronic kidney disease | ||

| No | 16 934 (54.1) | 14 351 (45.9) |

| Yes | 5636 (48.3) | 6041 (51.7) |

| Hospitalization during year before MI | ||

| No | 17 344 (54.6) | 14 420 (45.4) |

| Yes | 5226 (46.7) | 5972 (53.3) |

| Cancer | ||

| No | 17 764 (53.0) | 15 748 (47.0) |

| Yes | 4806 (50.9) | 4644 (49.1) |

| Skilled nursing facility stay during year before MI | ||

| No | 21 661 (53.0) | 19 236 (47.0) |

| Yes | 909 (44.0) | 1156 (56.0) |

| Stent during hospitalization | ||

| No | 7641 (42.5) | 10 353 (57.5) |

| Yes | 14 929 (59.8) | 10 039 (40.2) |

Abbreviations: CHD, coronary heart disease; MI, myocardial infarction.

Joint Modeling of Region and Hospital and Beneficiary Characteristics

Geographic region (eg, New England vs West South Central RR, 1.66 [95% CI, 1.47-1.87]; P < .001 across all categories), hospital ownership (eg, for-profit vs not-for profit RR, 0.86 [95% CI, 0.79-0.92]; P < .001 across all categories), hospital size (eg, <100 beds vs 200-299 beds RR, 0.95 [95% CI, 0.79-1.13]; P < .001 across all categories), and hospital medical school affiliation (RR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.05-1.17) as well as younger patient age (RR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.84-0.89), male sex (RR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.07-1.13), receipt of a stent during the index hospitalization (RR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.31-1.39), and lack of prior coronary heart disease (RR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.90-0.96) and heart failure (RR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.91-1.00) were associated with a high-intensity statin claim (Table 3). None of the Hospital Compare metrics were associated with a high-intensity statin claim. The multivariate association (ie, overall R2) between the full set of independent variables and high-intensity statin claim was 0.3146. Geographic region was the strongest correlate of high-intensity statin claim with a semipartial R2 value of 0.2207, followed by hospital ownership (semipartial R2, 0.0286), stenting during the index hospitalization (semipartial R2, 0.0229), medical school affiliation (semipartial R2, 0.0182), hospital size (semipartial R2, 0.0070), and patient age (semipartial R2, 0.0061) and sex (semipartial R2, 0.0026) (Figure 2). Characteristics of the study population by region are shown in eTables 6 and 7 in the Supplement.

Table 3. Adjusted Relative Risk for High-Intensity Statin Claims Following Myocardial Infarction Associated With Region and Hospital and Medicare Beneficiary Characteristics, 2014-2015.

| RR (95% CI)a | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital Characteristics | ||

| Geographic region | ||

| West South Central | 1 [Reference] | <.001 |

| Mountain | 1.32 (1.17-1.48) | |

| East South Central | 1.03 (0.92-1.14) | |

| Middle Atlantic | 1.32 (1.20-1.46) | |

| South Atlantic | 1.14 (1.05-1.24) | |

| West North Central | 1.19 (1.07-1.32) | |

| East North Central | 1.21 (1.10-1.32) | |

| Pacific | 1.28 (1.16-1.42) | |

| New England | 1.66 (1.47-1.87) | |

| Hospital ownership | ||

| Non–federal government | 1.07 (0.99-1.16) | <.001 |

| Not for profit | 1 [Reference] | |

| Profit | 0.86 (0.79-0.92) | |

| Hospital size, No. of beds | ||

| <100 | 0.95 (0.79-1.13) | <.001 |

| 100-199 | 1.03 (0.95-1.11) | |

| 200-299 | 1 [Reference] | |

| 300-399 | 0.98 (0.91-1.05) | |

| 400-499 | 1.01 (0.94-1.10) | |

| ≥500 | 1.15 (1.07-1.23) | |

| Metropolitan area, no vs yes | 1.00 (0.91-1.10) | .98 |

| Medical school affiliation, yes vs no | 1.11 (1.05-1.17) | <.001 |

| Hospital post-MI 30-d readmission below vs above or equal to median | 0.98 (0.94-1.03) | .42 |

| Hospital post-MI 30-d mortality below vs above or equal to median | 1.01 (0.96-1.06) | .70 |

| Hospital star rating above or equal to vs below median | 1.04 (0.98-1.10) | .20 |

| Hospital patient satisfaction below vs above or equal to median | 0.98 (0.92-1.05) | .55 |

| Overall 30-d risk-adjusted posthospitalization mortality below vs above or equal to median | 1.02 (0.96-1.08) | .55 |

| Patient Characteristics | ||

| Aged >75 vs ≤75 y | 0.87 (0.84-0.89) | <.001 |

| Male vs female | 1.10 (1.07-1.13) | <.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 1 [Reference] | .16 |

| Black | 1.07 (1.01-1.13) | |

| Asian | 0.98 (0.88-1.10) | |

| Hispanic | 0.96 (0.85-1.08) | |

| Other | 0.98 (0.90-1.07) | |

| Low income status, yes vs no | 1.02 (0.98-1.05) | .32 |

| Prior coronary heart disease, yes vs no | 0.93 (0.90-0.96) | <.001 |

| Diabetes, yes vs no | 0.99 (0.97-1.02) | .71 |

| Stroke, yes vs no | 0.94 (0.85-1.03) | .20 |

| Prior heart failure, yes vs no | 0.95 (0.91-1.00) | .04 |

| New heart failure, yes vs no | 1.01 (0.98-1.04) | .50 |

| Dementia, yes vs no | 0.90 (0.84-0.97) | .005 |

| Chronic kidney disease, yes vs no | 0.98 (0.95-1.02) | .32 |

| Hospitalization during year before MI, yes vs no | 0.96 (0.93-1.00) | .05 |

| Cancer, yes vs no | 0.97 (0.94-1.00) | .08 |

| Skilled nursing facility stay in year before MI, yes vs no | 1.00 (0.93-1.08) | .98 |

| Stent during hospitalization, yes vs no | 1.35 (1.31-1.39) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: MI, myocardial infarction; RR, relative risk.

Calculated using Poisson distribution mixed models with random effects for hospital and mutually adjusted for all of the characteristics in the table.

Figure 2. Relative Importance of Factors Associated With High-Intensity Statin Claims Among Medicare Beneficiaries After Myocardial Infarction (MI).

Factors associated with high-intensity statin use are ranked by semipartial R2 value, a measure of relative importance. Semipartial R2 values are shown by region, hospital characteristics, and patient characteristics. Semipartial R2 values were obtained from Poisson distribution mixed models with random effects for hospital. The values are mutually adjusted for all characteristics. Only variables with a semipartial R2 of greater than 0 are shown. CHD indicates coronary heart disease.

Sensitivity Analyses

Models for beneficiaries aged 66 to 75 years are shown in eTable 8 in the Supplement; for those older than 75 years, in eTable 9 in the Supplement. In both age groups, geographic region was most strongly associated with high-intensity statin use, and hospital ownership, hospital size, medical school affiliation, male sex, and receipt of a stent during the index hospitalization were associated with greater use of high-intensity statins.

Analyses restricted to beneficiaries who had no high-intensity statin claim before their index hospitalization are presented in eTable 10 in the Supplement. Consistent with the main analysis, geographic region and hospital characteristics were more strongly associated with a high-intensity statin claim than were beneficiary characteristics. Similarly, in an analysis that pooled beneficiaries with or without a statin claim in the 30 days after hospital discharge (eTables 11-13 in the Supplement), geographic region was the most strongly associated with high-intensity statin claims.

Discussion

High-intensity statin claims after MI varied widely by region, with greatest use in New England. In adjusted models, high-intensity statin claims also varied by hospital characteristics and beneficiary characteristics, but geographic region remained most strongly associated with a high-intensity statin claim after hospitalization for an MI among Medicare beneficiaries. Although high-intensity statin claims have increased in all regions since 2011, the increase has varied by region, and substantial disparities persist.

Heterogeneity in statin use by region has been reported by others in a variety of care settings. Kumar and colleagues9 published data from the outpatient Reduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health (REACH) Registry in 2009 demonstrating that statin use was highest in the Northeast and lowest in the Southern region of the United States among patients undergoing primary and secondary prevention therapy. Data from the Get with the Guidelines Initiative 2002 to 2010,6 an in-hospital quality improvement initiative for MI care with voluntary participation by selected hospitals, similarly showed the highest use of statins in the US Northeast and the lowest rate in the South. This report was limited to Hispanic patients but is of interest because few differences in clinical patient characteristics between regions were found, demonstrating that the regional differences were not primarily driven by characteristics of the patient population served.6 Lower rates of statin use in the southern United States were also present in the Get with the Guidelines Stroke initiative17 and in 2014 data from the EQuIPP database that measures performance among pharmacies serving Medicare beneficiaries through the Part D provisions.12 None of these studies differentiated use by intensity of statin treatment. Consistent with the pattern of regional variation in claims for high-intensity statins seen in the present investigation, we previously reported that, among Medicare beneficiaries, discontinuation of statin therapy after MI was lowest in New England.18 The present study extends prior findings by showing that regional differences in high-intensity statin use after MI were present in 2011 before the publication of the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol guidelines1 and have persisted through 2015 despite substantial increases in use of high-intensity statins in all regions since 2011.

Hospital characteristics shown to correlate with use of high-intensity statins in the present analysis are generally similar to those that have been reported to correlate with any vs no statin use by others.19,20,21 Consistent with the present analysis, statin use was higher in teaching hospitals compared with nonteaching hospitals based on data collected in 1999 to 2000 as part of the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events.19 The increase in the use of statin therapy after MI from 1992 to 2005 was also greater at teaching than nonteaching hospitals in Canada.21 Larger hospital size, which correlates with greater volume of patients with MI, has been associated with better adherence to MI performance measures and better outcomes.20

Use of high-intensity statins after MI varied with patient characteristics. After controlling for region and hospital characteristics, receipt of a stent was the patient characteristic most strongly associated with the use of high-intensity statins. As in prior studies, men were more likely than women to receive high-intensity statins after MI.22,23 In contrast, characteristics known to identify patients as being at very high risk of future events (prior coronary disease, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease)24,25 were not associated with a high-intensity statin claim or were associated with a slightly lower likelihood of a high-intensity statin claim. Despite emphasis on matching intensity of therapy with patient risk in current guidelines,1,2 data from the present study suggest that the treatment paradox of directing more intensive risk reduction therapies toward lower-risk patients persists in contemporary patient populations.26,27

Strengths and Limitations

We believe that our present study has important strengths. Use of claims data from Medicare with its large sample size allows for stable estimates of high-intensity statin claims and provides a high degree of generalizability to older adults in the United States. By combining information from Medicare with data from the American Hospital Association Survey and Hospital Compare, we were able to simultaneously assess regional and facility variations and beneficiary characteristics. The present study also has limitations. Having a prescription claim for a high-intensity statin does not necessarily equate to taking the high-intensity statin, although self-reported use and pill-bottle review correlate well with pharmacy claims.28,29 The present study lacks information about the health care professionals involved in inpatient and subsequent outpatient care and does not provide information about intended therapy (ie, prescriptions written). We relied on claims data and could not determine whether low- to moderate-intensity statin therapy was appropriate for individual patients based on lipid profiles and propensity for or prior experience of adverse effects of statins. However, such clinical characteristics are unlikely to vary sufficiently across the country to explain the large differences in high-intensity statin use by region. The present study is limited to adults 66 years or older with Medicare fee-for-service health insurance. Whether the results can be generalized to younger adults and those with commercial health insurance is unknown to date.

Conclusions

Among Medicare beneficiaries, geographic region, rather than patient and hospital characteristics, was the most closely associated with high-intensity statin use after MI, leading to large treatment disparities. Reasons for these persistent regional disparities are poorly understood and require further research and intervention.

eMethods. Expanded Description of Study Population

eFigure 1. Study Population for Analysis of Trends in High-Intensity Statin Use After MI Among Medicare Beneficiaries From 2011 to 2015

eFigure 2. Study Population for Analysis of Correlates of High-Intensity Statin Use After MI Among Medicare Beneficiaries in 2014 and 2015

eFigure 3. Map of Regions Defined by the US Census

eTable 1. Proportion of Medicare Beneficiaries With a Claim for an MI Hospitalization (2014-2015) Who Met All Eligibility Criteria Using the Selection Procedure Shown in eFigure 2

eTable 2. Trends in High-Intensity Statin Claims After MI Among Medicare Beneficiaries by Region and Hospital Characteristics

eTable 3. Trends in High-Intensity Statin Claims After MI Among Medicare Beneficiaries by Patient Characteristics

eTable 4. Association Between Hospital Characteristics and High-Intensity Statin Claims After MI Among Medicare Beneficiaries, 2014-2015

eTable 5. Association Between Beneficiary Characteristics and High-Intensity Statin Claims After MI Among Medicare Beneficiaries, 2014-2015

eTable 6. Hospital Characteristics by Geographic Region Among Medicare Beneficiaries Hospitalized for MI

eTable 7. Characteristics of Medicare Beneficiaries Hospitalized for MI by Geographic Region

eTable 8. Association Between Hospital and Beneficiary Characteristics and High-Intensity Statin Claims After MI Among Medicare Beneficiaries Aged 66-75 Years, 2014-2015

eTable 9. Association Between Hospital and Beneficiary Characteristics and High-Intensity Statin Claims After MI Among Medicare Beneficiaries Aged >75 Years, 2014-2015

eTable 10. Association Between Hospital and Beneficiary Characteristics and High-Intensity Statin Claims After MI Among Medicare Beneficiaries Who Did Not Use High-Intensity Statins Before the MI Hospitalization, 2014-2015

eTable 11. Medicare beneficiaries With High-Intensity Statin Claims After MI With the Denominator Including Medicare Beneficiaries With or Without a Statin Claim in the 30 Days After Hospital Discharge, 2014-2015

eTable 12. Medicare Beneficiaries With High-Intensity Statin Claims After MI With the Denominator Including Medicare Beneficiaries With or Without a Statin Claim in the 30 Days After Hospital Discharge, 2014-2015

eTable 13. Association Between Region, Hospital and Beneficiary Characteristics and High-Intensity vs No or Low/Moderate Intensity Statin Claims After MI Among Medicare Beneficiaries, 2014-2015

References

- 1.Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. ; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines . 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25)(suppl 2):S1-S45. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines [published online November 3, 2018]. J Am Coll Cardiol. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, et al. ; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration . Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1670-1681. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenson RS, Farkouh ME, Mefford M, et al. Trends in use of high-intensity statin therapy after myocardial infarction, 2011 to 2014. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(22):2696-2706. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice. Dartmouth Atlas Project. http://www.dartmouthatlas.org. Published 1996. Accessed June 8, 2018.

- 6.Krim SR, Vivo RP, Krim NR, et al. Regional differences in clinical profile, quality of care, and outcomes among Hispanic patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction in the Get with Guidelines-Coronary Artery Disease (GWTG-CAD) registry. Am Heart J. 2011;162(6):988-995.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pokharel Y, Akeroyd JM, Ramsey DJ, et al. Statin use and its facility-level variation in patients with diabetes: insight from the Veterans Affairs national database. Clin Cardiol. 2016;39(4):185-191. doi: 10.1002/clc.22503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pokharel Y, Tang F, Jones PG, et al. Adoption of the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol management guideline in cardiology practices nationwide. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(4):361-369. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.5922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar A, Fonarow GC, Eagle KA, et al. ; REACH Investigators . Regional and practice variation in adherence to guideline recommendations for secondary and primary prevention among outpatients with atherothrombosis or risk factors in the United States: a report from the REACH Registry. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2009;8(3):104-111. doi: 10.1097/HPC.0b013e3181b8395d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang G, Robinson JG, Lauffenburger J, Roth MT, Brookhart MA. Prevalent but moderate variation across small geographic regions in patient nonadherence to evidence-based preventive therapies in older adults after acute myocardial infarction. Med Care. 2014;52(3):185-193. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colantonio LD, Huang L, Monda KL, et al. Adherence to high-intensity statins following a myocardial infarction hospitalization among Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(8):890-895. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.0911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desai V, Nau D, Conklin M, Heaton PC. Impact of environmental factors on differences in quality of medication use: an insight for the Medicare star rating system. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(7):779-786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colantonio LD, Levitan EB, Yun H, et al. Use of Medicare claims data for the identification of myocardial infarction: the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke Study. Med Care. 2018;56(12):1051-1059. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Hospital Association AHA Annual Survey Database. https://www.ahadataviewer.com/additional-data-products/AHA-Survey/. Accessed October 10, 2016.

- 15.Medicare.gov Hospital Compare datasets. https://data.medicare.gov/data/hospital-compare. Updated April 24, 2019. Accessed July 13, 2017.

- 16.Jaeger BC, Edwards LJ, Das K, Sen PK. An R2 statistic for fixed effects in the generalized linear mixed model. J Appl Stat. 2017;44(6):1086-1105. doi: 10.1080/02664763.2016.1193725 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ovbiagele B, Schwamm LH, Smith EE, et al. Recent nationwide trends in discharge statin treatment of hospitalized patients with stroke. Stroke. 2010;41(7):1508-1513. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.573618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Booth JN III, Colantonio LD, Chen L, et al. Statin discontinuation, reinitiation, and persistence patterns among Medicare beneficiaries after myocardial infarction: a cohort study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10(10):e003626. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.003626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fox KA, Goodman SG, Klein W, et al. Management of acute coronary syndromes: variations in practice and outcome; findings from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE). Eur Heart J. 2002;23(15):1177-1189. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.3081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrison RW, Simon D, Miller AL, de Lemos JA, Peterson ED, Wang TY. Association of hospital myocardial infarction volume with adherence to American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association performance measures: insights from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry. Am Heart J. 2016;178:95-101. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2016.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Austin PC, Tu JV, Ko DT, Alter DA. Use of evidence-based therapies after discharge among elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction. CMAJ. 2008;179(9):895-900. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Virani SS, Woodard LD, Ramsey DJ, et al. Gender disparities in evidence-based statin therapy in patients with cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115(1):21-26. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.09.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peters SAE, Colantonio LD, Zhao H, et al. Sex differences in high-intensity statin use following myocardial infarction in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(16):1729-1737. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Ascenzo F, Biondi-Zoccai G, Moretti C, et al. TIMI, GRACE and alternative risk scores in acute coronary syndromes: a meta-analysis of 40 derivation studies on 216,552 patients and of 42 validation studies on 31,625 patients. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(3):507-514. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robinson JG, Huijgen R, Ray K, Persons J, Kastelein JJ, Pencina MJ. Determining when to add nonstatin therapy: a quantitative approach. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(22):2412-2421. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.09.928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yan AT, Yan RT, Tan M, et al. ; Canadian Acute Coronary Syndromes 1 and 2 Registry Investigators . Management patterns in relation to risk stratification among patients with non–ST elevation acute coronary syndromes. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(10):1009-1016. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.10.1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spertus JA, Furman MI. Translating evidence into practice: are we neglecting the neediest? Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(10):987-988. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.10.987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colantonio LD, Kent ST, Kilgore ML, et al. Agreement between Medicare pharmacy claims, self-report, and medication inventory for assessing lipid-lowering medication use. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25(7):827-835. doi: 10.1002/pds.3970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lauffenburger JC, Balasubramanian A, Farley JF, et al. Completeness of prescription information in US commercial claims databases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(8):899-906. doi: 10.1002/pds.3458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Expanded Description of Study Population

eFigure 1. Study Population for Analysis of Trends in High-Intensity Statin Use After MI Among Medicare Beneficiaries From 2011 to 2015

eFigure 2. Study Population for Analysis of Correlates of High-Intensity Statin Use After MI Among Medicare Beneficiaries in 2014 and 2015

eFigure 3. Map of Regions Defined by the US Census

eTable 1. Proportion of Medicare Beneficiaries With a Claim for an MI Hospitalization (2014-2015) Who Met All Eligibility Criteria Using the Selection Procedure Shown in eFigure 2

eTable 2. Trends in High-Intensity Statin Claims After MI Among Medicare Beneficiaries by Region and Hospital Characteristics

eTable 3. Trends in High-Intensity Statin Claims After MI Among Medicare Beneficiaries by Patient Characteristics

eTable 4. Association Between Hospital Characteristics and High-Intensity Statin Claims After MI Among Medicare Beneficiaries, 2014-2015

eTable 5. Association Between Beneficiary Characteristics and High-Intensity Statin Claims After MI Among Medicare Beneficiaries, 2014-2015

eTable 6. Hospital Characteristics by Geographic Region Among Medicare Beneficiaries Hospitalized for MI

eTable 7. Characteristics of Medicare Beneficiaries Hospitalized for MI by Geographic Region

eTable 8. Association Between Hospital and Beneficiary Characteristics and High-Intensity Statin Claims After MI Among Medicare Beneficiaries Aged 66-75 Years, 2014-2015

eTable 9. Association Between Hospital and Beneficiary Characteristics and High-Intensity Statin Claims After MI Among Medicare Beneficiaries Aged >75 Years, 2014-2015

eTable 10. Association Between Hospital and Beneficiary Characteristics and High-Intensity Statin Claims After MI Among Medicare Beneficiaries Who Did Not Use High-Intensity Statins Before the MI Hospitalization, 2014-2015

eTable 11. Medicare beneficiaries With High-Intensity Statin Claims After MI With the Denominator Including Medicare Beneficiaries With or Without a Statin Claim in the 30 Days After Hospital Discharge, 2014-2015

eTable 12. Medicare Beneficiaries With High-Intensity Statin Claims After MI With the Denominator Including Medicare Beneficiaries With or Without a Statin Claim in the 30 Days After Hospital Discharge, 2014-2015

eTable 13. Association Between Region, Hospital and Beneficiary Characteristics and High-Intensity vs No or Low/Moderate Intensity Statin Claims After MI Among Medicare Beneficiaries, 2014-2015