Abstract

Background

Many older patients don’t receive appropriate oncological treatment. Our aim was to analyse whether there are age differences in the use of adjuvant chemotherapy and preoperative radiotherapy in patients with colorectal cancer.

Methods

A prospective cohort study was conducted in 22 hospitals including 1157 patients with stage III colon or stage II/III rectal cancer who underwent surgery. Primary outcomes were the use of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer and preoperative radiotherapy for stage II/III rectal cancer. Generalised estimating equations were used to adjust for education, living arrangements, area deprivation, comorbidity and clinical tumour characteristics.

Results

In colon cancer 92% of patients aged under 65 years, 77% of those aged 65 to 80 years and 27% of those aged over 80 years received adjuvant chemotherapy (χ2trends < 0.001). In rectal cancer preoperative radiotherapy was used in 68% of patients aged under 65 years, 60% of those aged 65 to 80 years, and 42% of those aged over 80 years (χ2trends < 0.001). Adjusting by comorbidity level, tumour characteristics and socioeconomic level, the odds ratio of use of chemotherapy compared with those under age 65, was 0.3 (0.1–0.6) and 0.04 (0.02–0.09) for those aged 65 to 80 and those aged over 80, respectively; similarly, the odds ratio of use of preoperative radiotherapy was 0.9 (0.6–1.4) and 0.5 (0.3–0.8) compared with those under 65 years of age.

Conclusions

The probability of older patients with colorectal cancer receiving adjuvant chemotherapy and preoperative radiotherapy is lower than that of younger patients; many of them are not receiving the treatments recommended by clinical practice guidelines. Differences in comorbidity, tumour characteristics, curative resection, and socioeconomic factors do not explain this lower probability of treatment. Research is needed to identify the role of physical and cognitive functional status, doctors’ attitudes, and preferences of patients and their relatives, in the use of adjuvant therapies.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12885-019-5910-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Age, Equity, Adherence, Chemotherapy, Preoperative radiotherapy

Background

Evidence suggests that older patients can benefit from aggressive therapies as much as younger individuals can, improving their overall and disease-free survival [1]. Nevertheless, a high percentage of older patients do not receive standard cancer treatments [2–5]. A European study found that 69% of patients under 65 years old and only 16% of those over this age received adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer [4]. Several authors have shown that these differences remain after adjusting for comorbidity [2, 6]. Age has also been associated with the frequency of use of radiotherapy [7–9]. In Sweden, preoperative radiotherapy for rectal cancer was given to 64% of patients under 65 years old, to 50% of 65 to 79 years old and to 15% of those 80 years of age or older [7]. In Canada, Eldin et al. observed that after adjusting for comorbidity and stage, age was the most important factor in determining the use of radiotherapy [9]. Most of the revised studies have reported results adjusting for comorbidity and stage, but studies are scarce that in addition have adjusted for the patient’s social position and living arrangements. None of the multicentre studies has taken into account the inter-hospital variability both in clinical practice and in hospital area’s material deprivation.

A greater toxicity of chemotherapy and radiotherapy in older patients with colorectal cancer might explain a lower adherence to clinical practice guidelines. Further, the exclusion of older patients from clinical trials means that there is limited scientific evidence concerning the efficacy and toxicity associated with treatments in this population. This has led to a lack of evidence-based clinical guidelines [3]. For tumours at some anatomical sites, radiation therapy has been found to be more toxic in patients of advanced ages, suggesting a need for closer monitoring [1]. Nevertheless, the majority of clinical trials including older patients with colorectal cancer have reported toxicity profiles similar to those observed in younger patients [10, 11]. In addition to these clinical factors, there are social factors that may place older patients at a disadvantage with respect to receiving treatments, such as having a lower socioeconomic level [12–14] and a lower level of education [15], as well as more frequently living alone [16].

The aims of this paper were a) to identify whether there are differences between age groups in the use of chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer and preoperative radiotherapy for stage II and III rectal cancer; and b) to assess whether these differences remain after adjusting for comorbidity, tumour characteristics, curative resection and social factors such as economic deprivation or living arrangements.

Methods

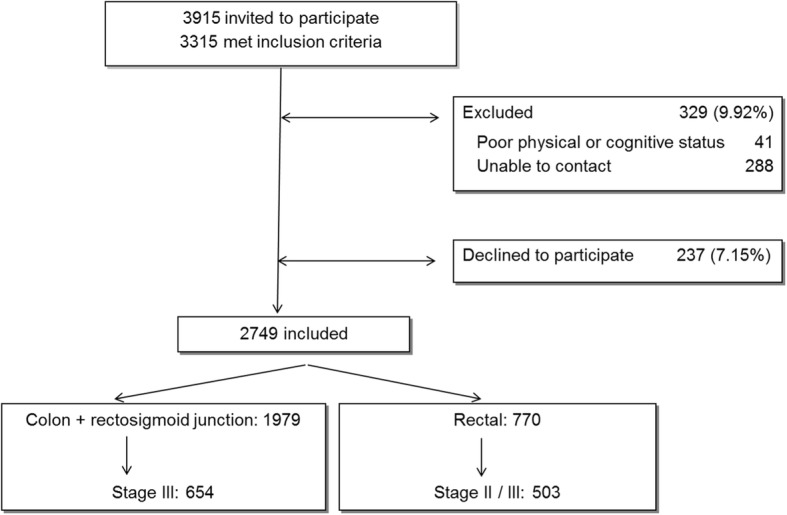

Data were obtained by conducting a prospective multicentre cohort study in 22 hospitals in five autonomous regions in Spain. We included patients with primary invasive colon or rectal cancer who underwent programmed or urgent surgery between April 2010 and December 2012. A detailed protocol was published by Quintana et al. [17]. Among the 3315 patients who met the inclusion criteria, 41 were excluded from the study due to poor physical or cognitive status, and we failed to contact another 288. In addition, 237 (7.2%) declined to participate in the study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patients through the study and reasons for non-inclusion

Outcomes and covariates

The primary outcomes analysed were the use of adjuvant chemotherapy in stage III colon cancer and preoperative radiotherapy in stage II and III rectal cancer. Age was assessed at the time of diagnoses and arbitrarily categorized into three groups: younger (under 65 years of age), older (65 to 80 years) and oldest (over 80 years) patients.

We assessed prognostic factors, which according to the scientific literature, might be unevenly distributed between age groups: a) Social and economic variables: socioeconomic level, considering level of education and area of residence deprivation, which was calculated following the methodology of Esnaola et al. [18], for each census tract based on five 2001 census indicators related to occupation and educational attainment; living arrangements (alone or with others);

b) health behaviours: alcohol intake (greater than 80 g/day or not) and smoking habits (current smoker, ex-smoker, never smoker);

c) cancer family history and whether the diagnosis had been made through a screening programme or not;

d) health status: comorbidities, measured using the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) [19], stratifying patients into three groups (0, 1, and 2 or more), and the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class [20], a proxy for the severity of patients’ comorbidities;

e) tumour characteristics: site (proximal colon, distal colon, rectosigmoid junction or rectum), histological findings (adenocarcinoma, mucinous adenocarcinoma, signet ring cell carcinoma, others), degree of differentiation (low, corresponding to tumours that are well or moderately well differentiated, or high, corresponding to poorly differentiated and undifferentiated tumours); h) tumour stage (according to the 7th edition of the TNM classification of the Union for International Cancer Control), assigning patients who underwent neoadjuvant treatment a clinical stage and those who underwent surgery as the first treatment a pathological stage, for statistical analysis;

f) surgery: profile of the surgeon (fully dedicated to coloproctology or not); type of surgery (elective/emergency); curative resection (no residual tumour (R0) or microscopic/macroscopic remnant of the tumour (R1/R2)); and finally whether a cancer committee was involved in the patient’s management, as a process indicator.

Statistical analysis

First, potential prognostic factors were compared among the three age groups using Pearson chi-square test (χ2) and chi square test for trends (χ2trends). Then, the univariate association of each factor with the use of adjuvant chemotherapy and preoperative radiotherapy was investigated using Pearson chi square test for the categorical non ordinal variables and chi square test for trends for the ordinal variables. Multivariable analyses were performed with Generalised Estimating Equations, clustering by hospital, to assess the association between age and the use of chemotherapy and preoperative radiotherapy, adjusting for sociodemographic and clinical factors. This approach enabled us to construct multivariate models that take into account the correlation between individuals from the same hospital. An unstructured variance-covariance matrix was used. Potential confounders with p < 0.2 in the univariate analysis were entered simultaneously in the multivariable model using dummy variables. Missing data were imputed using the multiple imputation method available in SPSS which uses by default 5 iterations. The imputed variables were: level of education, deprivation index, screening, ASA class and alcohol intake. The variables used for the imputation were as follows: age, level of education, deprivation index, autonomous region, CCI, ASA class, alcohol intake and surgeon profile. The calculated measure of association was the odds ratio with the corresponding 95% confidence interval. Two-tailed tests were used, considering p values < 0.05 to be statistically significant. The analysis was performed using IBM SPSS, Statistics for Windows, v23, and Stata v14.

Results

A total of 2749 patients were finally included in the study, among whom 654 had stage III colon cancer and 503 stage II or III rectal cancer (Fig. 1). This research report refers to these 1157 patients.

Patients included were significantly older than those who were excluded or not contactable (p, χ2 < 0.005), but differences with those who declined to participate were not statistically significant.

Of the included patients, 38.8% were under 65 years, 47.2% were between 65 and 80 years, and 13.9% were over 80 years of age. Approximately two thirds (65.2%) were men. Overall, 13% had not completed any formal education, and only 12% had university qualifications (short- or long-cycle degrees). Most participants (86%) lived with a relative.

Tables 1 and 2 indicate the observed differences between age groups, for colon and rectum respectively. Older patients were more likely to have a low education level (p, χ2trends < 0.0005) and to live alone (p, χ2 < 0.0005). No significant differences were found in deprivation of the area of residence (p = 0.9). Younger patients were more likely to report a family history of cancer (p, χ2 < 0.05). The proportion of patients who have never smoked increases with age (p, χ2 < 0.05) and comorbidity increases with age (p, χ2trends < 0.0005). In colon cancer there were no age significant differences in tumour sites, histological classification, degree of differentiation or, in rectal cancer, in stage at diagnosis. Finally, we did not find differences in curative resections (R0) by age.

Table 1.

Distribution of social, health and clinical patient’s variables by age groups in stage III colon cancer (n = 654)

| N | < 65 years N = 246 n (%) |

65–80 years N = 311 n (%) |

> 80 years N = 97 n (%) |

P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic variables | |||||

| Sex | 654 | ||||

| Male | 151 (61.4) | 205 (65.9) | 60 (61.9) | 0.50 | |

| Female | 95 (38.6) | 106 (34.1) | 37 (38.1) | 0.65 | |

| Deprivation index | 624 | ||||

| Quartile 1 least deprived | 49 (21.2) | 67 (22.3) | 17 (18.5) | 0.67 | |

| Quartile 2 | 64 (27.7) | 101 (33.6) | 31 (33.7) | 0.78 | |

| Quartile 3 | 67 (29.0) | 72 (23.9) | 22 (23.9) | ||

| Quartile 4 most deprived | 51 (22.1) | 61 (20.3) | 22 (23.9) | ||

| Level of education | 534 | ||||

| Illiterate or with no formal education | 10 (4.8) | 46 (18.2) | 15 (20.5) | < 0.0005 | |

| Primary | 123 (59.1) | 162 (64.0) | 50 (68.5) | < 0.0005 | |

| Secondary | 35 (16.8) | 24 (9.5) | 3 (4.1) | ||

| University | 40 (19.2) | 21 (8.3) | 5 (6.8) | ||

| Living arrangements | 522 | ||||

| Living alone | 23 (11.5) | 42 (17.0) | 14 (18.7) | 0.18 | |

| Living with others | 177 (88.5) | 205 (83.0) | 61 (81.3) | 0.08 | |

| Family history of cancer | 584 | ||||

| No | 118 (52.2) | 175 (63.9) | 68 (81.0) | < 0.0005 | |

| Yes | 108 (47.8) | 99 (36.1) | 16 (19.0) | < 0.0005 | |

| Screening | 622 | ||||

| No | 174 (74.0) | 250 (84.7) | 86 (93.5) | < 0.0005 | |

| Yes | 61 (26.0) | 45 (15.3) | 6 (6.5) | < 0.0005 | |

| Health behaviours and comorbidities | |||||

| Smoking habits | 648 | ||||

| Never smoker | 112 (45.5) | 154 (50.0) | 50 (53.2) | 0.01 | |

| Current smoker | 42 (17.1) | 31 (10.1) | 4 (4.3) | 0.79 | |

| Ex-smoker | 92 (37.4) | 123 (39.9) | 40 (42.6) | ||

| Alcohol | 612 | ||||

| No | 188 (83.9) | 257 (86.2) | 84 (93.3) | 0.09 | |

| Yes | 36 (16.1) | 41 (13.8) | 6 (6.7) | 0.04 | |

| ASA class | 633 | ||||

| I-II | 175 (73.2) | 157 (52.2) | 30 (32.3) | < 0.0005 | |

| III | 60 (25.1) | 127 (42.2) | 52 (55.9) | < 0.0005 | |

| IV | 4 (1.7) | 17 (5.6) | 11 (11.8) | ||

| Charlson Index | 654 | ||||

| 0 | 163 (66.3) | 158 (50.8) | 40 (41.2) | < 0.0005 | |

| 1 | 49 (19.9) | 80 (25.7) | 26 (26.8) | < 0.0005 | |

| ≥ 2 | 34 (13.8) | 73 (23.5) | 31 (32.0) | ||

| Tumour characteristics | |||||

| Site | 654 | ||||

| Rectosigmoid junction | 40 (16.3) | 45 (14.5) | 11 (11.3) | 0.72 | |

| Distal colon | 108 (43.9) | 140 (45.0) | 41 (42.3) | 0.21 | |

| Proximal colon | 98 (39.8) | 126 (40.5) | 45 (46.4) | ||

| Histological classification | 643 | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 219 (91.3) | 274 (89.3) | 87 (90.6) | 0.18 | |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 16 (6.7) | 27 (8.8) | 9 (9.4) | 0.69 | |

| Signet-ring cell carcinoma | 2 (0.8) | 6 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Other types of carcinoma | 3 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Degree of differentiation | 573 | ||||

| Low grade | 165 (79.3) | 226 (81.9) | 79 (88.8) | 0.15 | |

| High grade | 43 (20.7) | 50 (18.1) | 10 (11.2) | 0.07 | |

| Intervention | |||||

| Main intervention | 654 | ||||

| Elective | 232 (94.3) | 300 (96.5) | 87 (89.7) | 0.03 | |

| Emergency | 14 (5.7) | 11 (3.5) | 10 (10.3) | 0.32 | |

| Curative resection | 618 | ||||

| R0 | 218 (92.4) | 261 (90.0) | 84 (91.3) | 0.63 | |

| R1 / R2 | 18 (7.6) | 29 (10.0) | 8 (8.7) | 0.56 | |

| Surgeon’s profile | 615 | ||||

| General | 61 (27.0) | 96 (32.5) | 36 (38.3) | 0.12 | |

| Coloproctologist | 165 (73.0) | 199 (67.5) | 58 (61.7) | 0.04 | |

| Cancer committee | 617 | ||||

| No | 77 (32.9) | 127 (43.6) | 44 (47.8) | 0.01 | |

| Yes | 157 (67.1) | 164 (56.4) | 48 (52.2) | 0.004 | |

aPearson Chi-square test to generate upper P value and chi-square test for trends to generate lower P value

Table 2.

Distribution of social, health and clinical patient’s variables by age groups in stage II, III rectal cancer (n = 503)a

| N | < 65 years N = 203 n (%) |

65–80 years N = 235 n (%) |

> 80 years N = 64 n (%) |

P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic variables | |||||

| Sex | 502 | ||||

| Male | 128 (63.1) | 169 (71.9) | 41 (64.1) | 0.12 | |

| Female | 75 (36.9) | 66 (28.1) | 23 (35.9) | 0.35 | |

| Deprivation index | 476 | ||||

| Quartile 1 least deprived | 28 (14.7) | 41 (18.6) | 12 (18.8) | 0.66 | |

| Quartile 2 | 68 (35.6) | 72 (32.6) | 16 (25.0) | 0.80 | |

| Quartile 3 | 57 (29.8) | 71 (32.1) | 24 (37.5) | ||

| Quartile 4 most deprived | 38 (19.9) | 37 (16.7) | 12 (18.8) | ||

| Level of education | 408 | ||||

| Illiterate or with no formal education | 9 (5.3) | 30 (15.9) | 11 (22.4) | < 0.0005 | |

| Primary | 100 (58.8) | 137 (72.5) | 33 (67.3) | < 0.0005 | |

| Secondary | 34 (20.0) | 8 (4.2) | 1 (2.0) | ||

| University | 27 (15.9) | 14 (7.4) | 4 (8.2) | ||

| Living arrangements | 403 | ||||

| Living alone | 11 (6.7) | 30 (15.8) | 9 (18.8) | 0.01 | |

| Living with others | 154 (93.3) | 160 (84.2) | 39 (81.3) | 0.005 | |

| Family history of cancer | 464 | ||||

| No | 97 (51.9) | 126 (58.3) | 42 (68.9) | 0.06 | |

| Yes | 90 (48.1) | 90 (41.7) | 19 (31.1) | 0.02 | |

| Screening | 478 | ||||

| No | 167 (87.0) | 199 (88.8) | 58 (93.5) | 0.36 | |

| Yes | 25 (13.0) | 25 (11.2) | 4 (6.5) | 0.18 | |

| Health behaviours and comorbidities | |||||

| Smoking habits | 498 | ||||

| Never smoker | 82 (40.4) | 104 (44.8) | 37 (58.7) | 0.001 | |

| Current smoker | 49 (24.1) | 30 (12.9) | 3 (4.8) | 0.37 | |

| Ex-smoker | 72 (35.5) | 98 (42.2) | 23 (36.5) | ||

| Alcohol | 483 | ||||

| No | 175 (89.3) | 198 (87.2) | 56 (93.3) | 0.39 | |

| Yes | 21 (10.7) | 29 (12.8) | 4 (6.7) | 0.70 | |

| ASA class | 490 | ||||

| I-II | 144 (73.1) | 118 (51.5) | 31 (48.4) | < 0.0005 | |

| III | 51 (25.9) | 101 (44.1) | 31 (48.4) | < 0.0005 | |

| IV | 2 (1.0) | 10 (4.4) | 2 (3.1) | ||

| Charlson Index | 502 | ||||

| 0 | 134 (66.0) | 118 (50.2) | 25 (39.1) | < 0.0005 | |

| 1 | 43 (21.2) | 60 (25.5) | 18 (28.1) | < 0.0005 | |

| ≥ 2 | 26 (12.8) | 57 (24.3) | 21 (32.8) | ||

| Tumour characteristics | |||||

| Histological classification | 467 | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 181 (96.8) | 201 (92.6) | 58 (92.1) | 0.05 | |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 5 (2.7) | 16 (7.4) | 4 (6.3) | 0.05 | |

| Signet-ring cell carcinoma | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Other types of carcinoma | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.6) | ||

| Degree of differentiation | 389 | ||||

| Low grade | 137 (86.7) | 153 (86.0) | 48 (90.6) | 0.68 | |

| High grade | 21 (13.3) | 25 (14.0) | 5 (9.4) | 0.62 | |

| Stage at diagnosis (pTNM or cTNM) | 502 | ||||

| II | 61 (30.0) | 76 (32.3) | 27 (42.2) | 0.19 | |

| III | 142 (70.0) | 159 (67.7) | 37 (57.8) | 0.11 | |

| Intervention | |||||

| Main intervention | 502 | ||||

| Elective | 200 (98.5) | 234 (99.6) | 64 (100.0) | 0.35 | |

| Emergency | 3 (1.5) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.16 | |

| Curative resection | 476 | ||||

| R0 | 162 (84.4) | 193 (85.4) | 52 (89.7) | 0.60 | |

| R1/R2 | 30 (15.6) | 33 (14.6) | 6 (10.3) | 0.37 | |

| Surgeon’s profile | 476 | ||||

| General | 59 (30.3) | 71 (32.3) | 18 (29.5) | 0.87 | |

| Coloproctologist | 136 (69.7) | 149 (67.7) | 43 (70.5) | 0.92 | |

| Cancer committee | 418 | ||||

| No | 52 (27.2) | 74 (33.2) | 19 (29.7) | 0.42 | |

| Yes | 139 (72.8) | 149 (66.8) | 45 (70.3) | 0.42 | |

aAge was missing in a case

bPearson Chi-square test to generate upper P value and chi-square test for trends to generate lower P value

Among the main differences in colon and rectal cancer, we highlight the following: younger patients were more likely to have undergone screening (p, χ2 < 0.0005) in colon cancer but there were no significant differences in rectal cancer; among those with colon cancer, patients over 80 years of age were more likely to have had emergency surgery (p, χ2 = 0.04) compared with those under age 80; with increasing age, the number of surgical interventions done by surgeons specialized in coloproctology decreased (p, χ2trends = 0.04) and the proportion of cases reviewed by an interdisciplinary tumor committee decreased (p, χ2trends = 0.004). These differences were not observed among those with rectal cancer.

Table S1 reports the frequencies of imputed variables before and after imputation. The distribution of the imputed values can be seen to be homogenous (Additional file 1: Table S1).

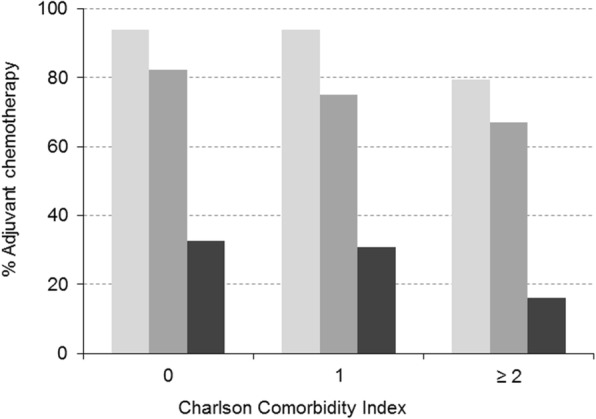

Adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with colon cancer

Of the 654 patients with stage III colon or rectosigmoid cancer identified, 75% received chemotherapy after surgical resection. Table 3A summarises the univariate association of patient characteristics with chemotherapy. The use of this therapy decreased significantly with age, from 91.9% in the youngest age group to 76.7% in the older group to only 26.8% in the oldest patients (p, χ2trends < 0.0005). No significant difference in use of adjuvant chemotherapy was observed by sex. A higher level of comorbidity was also associated with less use of chemotherapy, with a rate of 82% in patients with no comorbidities falling to just 58.7% in those with a CCI of 2 or more. Nevertheless, we should note that even among patients with no comorbidities, older age was also associated with less use of chemotherapy; the rates were 94, 82 and 33% for those under 65, between 65 and 80, and over 80 years of age, respectively (p, χ2trends < 0.0005) (Fig. 2). Table 3B shows the multivariable results. There was a significant negative association between age and the use of chemotherapy after simultaneously adjusting for comorbidity, tumour characteristics (such as the site and degree of differentiation) and level of education. Compared to younger patients, the adjusted OR was 0.3 (95% CI: 0.1–0.6) for the older and 0.04 (95% CI: 0.02–0.09) for the oldest age groups. We found no significant association between chemotherapy use and either participation of the cancer committee in the management of the patient or the surgeon’s specialisation. The outcome of the surgery did not have a significant effect on the chemotherapy use.

Table 3.

Crude and adjusted analysis of the association between age and adjuvant chemotherapy in stage III colon cancer

| Adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3A. Univariate analysis | 3B. Multivariate analysis | |||

| n (%) | P value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age, years | ||||

| < 65 | 226 (91.9) | < 0.0005b | 1 | |

| 65–80 | 239 (76.8) | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) | 0.001 | |

| > 80 | 26 (26.8) | 0.04 (0.02–0.09) | < 0.0005 | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 309 (74.3) | 0.57a | ||

| Female | 182 (76.5) | |||

| Deprivation index | ||||

| Quartile 1 | 106 (79.7) | 0.29b | ||

| Quartile 2 | 142 (72.4) | |||

| Quartile 3 | 121 (75.2) | |||

| Quartile 4 | 97 (72.4) | |||

| Level of education | ||||

| No formal | 47 (66.2) | < 0.0005b | 1 | |

| Primary | 253 (75.5) | 1.2 (0.7–2.2) | 0.46 | |

| Secondary | 53 (85.5) | 1.6 (0.4–5.5) | 0.46 | |

| University | 59 (89.4) | 1.6 (0.5–5.7) | 0.45 | |

| Living arrangement | ||||

| Living alone | 56 (70.9) | 0.2a | ||

| Living with others | 345 (77.9) | |||

| Family history of cancer | ||||

| No | 257 (71.2) | < 0.0005a | 1 | |

| Yes | 194 (87.0) | 1.9 (0.7–5.0) | 0.21 | |

| Screening | ||||

| No | 368 (72.2) | 0.001a | 1 | |

| Yes | 97 (86.6) | 1.0 (0.4–2.2) | 0.99 | |

| Smoking habits | ||||

| Never smoker | 241 (76.3) | 0.516a | ||

| Current smoker | 61 (79.2) | |||

| Ex-smoker | 187 (73.3) | |||

| Alcohol | ||||

| No | 392 (74.1) | 0.42a | ||

| Yes | 63 (75.9) | |||

| Charlson index | ||||

| 0 | 296 (82.0) | < 0.0005b | 1 | |

| 1 | 114 (73.5) | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) | 0.43 | |

| ≥ 2 | 81 (58.7) | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) | 0.17 | |

| ASA class | ||||

| I-II | 309 (85.4) | < 0.0005b | 1 | |

| III | 155 (64.9) | 0.6 (0.3–1.1) | 0.10 | |

| IV | 10 (31.3) | 0.1 (0.03–0.3) | < 0.0005 | |

| Site | ||||

| Rectosigmoid junction | 78 (81.3) | 0.19a | 1 | |

| Distal colon | 219 (75.8) | 0.5 (0.2–1.4) | 0.18 | |

| Proximal colon | 194 (72.1) | 0.5 (0.2–1.6) | 0.25 | |

| Degree of differentiation | ||||

| Low grade | 354 (75.3) | 0.12a | 1 | |

| High grade | 85 (82.5) | 1.2 (0.4–3.4) | 0.70 | |

| Histological classification | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 439 (75.7) | 0.29a | ||

| Mucinous Adenocarcinoma | 38 (73.1) | |||

| Signet-ring cell carcinoma | 8 (100.0) | |||

| Other carcinomas | 3 (100.0) | |||

| Cancer committee | ||||

| No | 180 (72.6) | 0.30a | ||

| Yes | 282 (76.4) | |||

| Surgeon’s profile | ||||

| General | 134 (69.4) | 0.07a | 1 | |

| Coloproctologist | 323 (76.5) | 1.3 (0.6–3.1) | 0.50 | |

| Curative resection | ||||

| R0 | 428 (76.0) | 0.62a | ||

| R1/R2 | 40 (72.7) | |||

aPearson Chi-square test

bChi-square test for trends

Fig. 2.

Percentage of patients with stage III colon cancer who received chemotherapy by age and number of comorbidities. Legend: Age (years)  < 65,

< 65,  65–80,

65–80,  > 80

> 80

The most frequent chemotherapy schemes were CAPOX (capecitabine, oxaliplatin) in 49.4% of patients, FOLFOX (5- Fluorouracil, oxaliplatin) in 26.9% and capecitabine in monotherapy in 20% of the cases. Oxaliplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy administration varied with age as follows: 83.4% in the younger group, 64.2% in the older and 29% in the oldest (p, χ2trends < 0.0005). The administration of capecitabine in monotherapy was 11.7, 24.6 and 57.9%, respectively, (p, χ2trends < 0.0005).

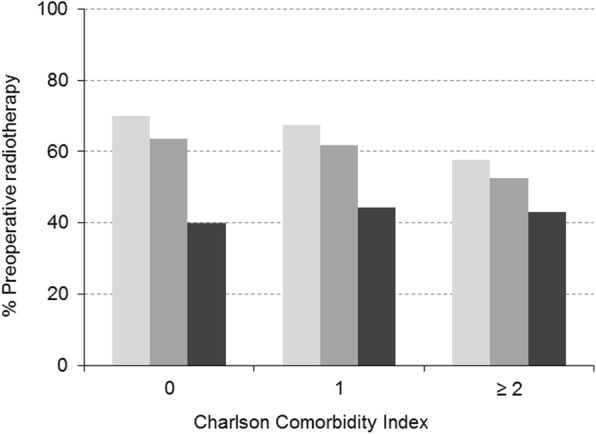

Preoperative radiotherapy for patients with rectal cancer

Of the 503 patients with stage II and III rectal cancer, 61% received radiotherapy before surgical intervention. Table 4A shows the univariate association of patient characteristics with preoperative radiotherapy. It was observed that its use decreased significantly with age, from 68% in the youngest age group to 60.4% in the older to 42.2% in the oldest patients (p, χ2trends < 0.0005). No significant association was observed between preoperative radiotherapy and sex or with socioeconomic characteristics or living arrangements. We also found significant differences in patients with no comorbidities, with rates of use of 70, 64 and 40% in the three age groups, respectively (p, χ2trends = 0.009) (Fig. 3). After simultaneously adjusting for family history of cancer, comorbidities and their severity, and tumour stage (Table 4B), age remained the main predictor. Compared to younger patients, the adjusted OR for the oldest patients was 0.5 (95% CI: 0.3–0.8), while the odds in the group of patients aged 65 to 80 years was not significantly lower with respect to the youngest group. We found no association of CCI or ASA with the use of radiotherapy, but family history was associated with a higher odds of use (OR = 1.5, 95% CI: 1.0–2.2), as was the tumour stage (OR = 2.8, 95% CI: 1.5–4.9).

Table 4.

Crude and adjusted analysis of the association between age and preoperative radiotherapy in stage II and III rectal cancer patients

| Preoperative radiotherapy in stage II and III rectal cancer | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4A. Univariate analysis | 4B. Multivariate analysis | |||

| n (%) | P value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age, years | ||||

| < 65 | 138 (68.0) | < 0.0005b | 1 | |

| 65–80 | 142 (60.4) | 0.9 (0.6–1.4) | 0.74 | |

| > 80 | 27 (42.2) | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | 0.004 | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 205 (60.7) | 0.85a | ||

| Female | 102 (61.8) | |||

| Deprivation index | ||||

| Quartile 1 | 50 (61.7) | 0.31b | ||

| Quartile 2 | 86 (54.8) | |||

| Quartile 3 | 94 (61.8) | |||

| Quartile 4 | 57 (65.5) | |||

| Level of education | ||||

| No formal | 31 (62.0) | 0.78b | ||

| Primary | 164 (60.5) | |||

| Secondary | 28 (65.1) | |||

| University | 25 (55.6) | |||

| Living arrangements | ||||

| Living alone | 30 (60.0) | 0.88a | ||

| Living with others | 217 (61.3) | |||

| Family history of cancer | ||||

| No | 147 (55.3) | 0.005a | 1 | |

| Yes | 136 (68.3) | 1.5 (1.0–2.1) | 0.05 | |

| Screening | ||||

| No | 262 (61.6) | 0.30a | ||

| Yes | 29 (53.7) | |||

| Smoking habits | ||||

| Never smoker | 136 (60.7) | 0.31a | ||

| Current smoker | 56 (68.3) | |||

| Ex-smoker | 113 (58.5) | |||

| Alcohol | ||||

| No | 264 (61.4) | 0.77a | ||

| Yes | 32 (59.3) | |||

| Charlson index | ||||

| 0 | 179 (64.6) | 0.03b | 1 | |

| 1 | 74 (60.7) | 0.9 (0.6–1.4) | 0.77 | |

| ≥ 2 | 54 (51.9) | 0.9 (0.5–1.7) | 0.88 | |

| ASA class | ||||

| I-II | 187 (63.8) | 0.12b | 1 | |

| III | 106 (57.6) | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 0.39 | |

| IV | 7 (50.0) | 0.8 (0.3–2.4) | 0.68 | |

| Degree of differentiation | ||||

| Low grade | 201 (59.5) | 0.76a | ||

| High grade | 29 (56.9) | |||

| Histological classification | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 268 (60.8) | 0.29a | ||

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 13 (52.0) | |||

| Stage | ||||

| II | 75 (45.7) | < 0.0005a | 1 | |

| III | 232 (68.4) | 2.8 (1.5–4.9) | 0.001 | |

| Cancer committee | ||||

| No | 84 (57.9) | 0.48a | ||

| Yes | 205 (61.6) | |||

| Surgeon’s profile | ||||

| General | 91 (61.1) | 1.0a | ||

| Coloproctologist | 201 (61.3) | |||

aPearson Chi-square test

bChi-square test for trends

Fig. 3.

Percentage of patients with stage II and III rectal cancer who received preoperative radiotherapy by age and number of comorbidities. Legends: Age (years)  < 65,

< 65,  65–80,

65–80,  > 80

> 80

Discussion

Chemotherapy

In our cohort of patients treated between 2010 and 2012, we found that 70% of all stage III patients with colon cancer received chemotherapy; however, its use dramatically decreased with age, with a percentage of 92% in under-65-year-olds but only 27% among over-80-year-olds. Data from Europe and Australia, where there are health systems with quasi-universal coverage as in Spain, indicate that no more than 20–25% of patients over 75 years old received adjuvant chemotherapy in 2000. In the USA, these percentages reach 40 to 50% [21]. In Spain, on the basis of population data, a study reported that the percentages of chemotherapy use fall from 61% in under-75-year-olds to 27% in patients 75 years of age or older [22].

In our study, a quarter of patients between 65 and 80 years old did not receive any chemotherapy. In some patients, this is attributable to a higher level of comorbidity, but we observed that the pattern remains even in patients with no comorbidities. Moreover, variables such as high alcohol intake, tumour characteristics (site and histological findings), and even curative resection had less influence than age on the decision of whether to treat. This is consistent with previous scientific reviews that have demonstrated a lower use of chemotherapy among the older even after adjusting for comorbidity and other relevant clinical variables [2, 21].

A low level of education, area of residence deprivation and marital status have been reported to be associated with lower probability of treatment [15, 23, 24]. In our study, we have observed that the magnitude of the association between age and chemotherapy does not change when we adjust for level of education, which means that the lower level of education in older patients does not help to explain the differences observed by age group. The deprivation index and living arrangement were also not found to be significantly associated with the use of chemotherapy.

In agreement with previous authors, we observed that those older than 65 were less likely to be treated with chemotherapy in spite of its survival advantage [25, 26]. Furthermore, the very old patients who received chemotherapy were more likely to be treated with capecitabine in monotherapy. Further research needs to be done in the oldest age groups, who have been excluded from most clinical trials and for whom little knowledge on treatment efficacy and safety is available [27].

Preoperative radiotherapy

The percentages of use of preoperative radiotherapy among patients under 65, between 65 and 80 and over 80 years of age were 68, 60 and 42%, respectively. The decrease with increasing age remained significant after adjusting for comorbidities and the other covariates. Compared to patients under 65 years of age, the adjusted ORs for patients between 65 and 80 and those over 80 years of age were 0.9 and 0.5, respectively.

Previously available evidence, derived from population-level data, indicated less use of radiotherapy among older patients. In Spain, 24% of under-75-year-olds and 11% of patients 75 years of age or older with colorectal cancer have received radiotherapy [22, 28]. In Sweden, the use of preoperative radiotherapy falls from 64% in under-65-year-olds to 15% in over-80-year-olds [7]. According to a review by Faivre [21], the rates of pre- and post-operative radiotherapy ranged from 20 to 50% in different registries in Europe and the USA.

In our study, comorbidity, area of residence deprivation, education and living arrangements did not predict the decision to treat preoperatively with radiotherapy. We did not find studies that analysed the influence of comorbidities. Previous studies have reported living arrangements and marital status to be significant predictors of the use of radiotherapy [7, 15, 29]. We should note that in our study, the percentage of older patients who lived alone was very low (14%). In other countries, the figures reach 35% in people above 65 years old and 50% in those above 80 years of age. This reflects the level of family support, especially from offspring, for widows/widowers in Spain. In Sweden, a study reported an association with income but not with level of education [7].

Another potentially relevant factor is the distance from the tumour to the anal verge, but there is evidence that this factor is not associated with age [8]. We did not study this issue, but some authors have found a strong association between age and the use of radiotherapy regardless of tumour sub-site location [7].

Limitations

This study has some limitations that should be recognised. We were not able to contact nearly 9% of eligible patients, and we found that these patients were older than the participants; hence, the older patients included may be a biased sample of the older population. If the clinical status of participants was better than that of those excluded, we could be underestimating the real effect of age on the use of cancer treatments. Another selection bias could be associated with the type of centres included in the study, given that most of them were referral hospitals with specialised units.

Regarding comorbidity, it has been suggested that the CCI may not capture comorbidities well, as it does not measure the severity of comorbid conditions [30]. To compensate for this limitation, at least partially, we included ASA class as a proxy for disease severity.

Apart from comorbidity, another factor that could justify a lower use of treatment in older people is a supposedly greater toxicity. There is some evidence suggesting a lack of association between age and toxicity [31] or even a lower incidence of adverse effects in people above 75 years old [32, 33], attributable to dose reduction and the use of less aggressive treatment regimens in this age group. A recent Danish study found that over-70-year-olds with colorectal cancer were treated with single-agent therapy and at a lower initial dosage and that this chemotherapy dose reduction did not have an impact on disease-free survival or cancer-specific mortality; these outcomes were only different in the older patients who received less than half of the full number of cycles (given to other patients) [11]. Nevertheless, other authors have described a higher level of toxicity with age [2, 34]. In the present study, we did not assess adverse events.

A weakness in determining the causes of the low adherence to clinical practice guidelines for older patients is the lack of information concerning the functional status of patients, which might explain treatment decisions. An alteration in the instrumental activities of daily living has been significantly associated with chemotherapy-related toxicity [35]. Further, poor nutritional status has been described as a predictor of a lower tolerance to chemotherapy, and factors such as malnutrition and frailty have been associated with higher mortality in patients with colorectal cancer undergoing palliative chemotherapy [36]. It would be of interest to know whether the 41 patients excluded because of functional limitations received chemo/radio-therapy but poor functional or cognitive status was used as exclusion criterion in the main study. In the case of radiotherapy, another factor that might hinder treatment is difficulty of access to treatment centres [37], although we think that this factor would not have a great impact in our setting, given that when the distance to the hospital is large, public services provide transport to patients who need it.

In our study, we did not take into account variables such as the opinions of doctors and preferences of patients and their relatives. According to some authors, the opinions and attitudes of doctors may explain the low prescription of adjuvant chemotherapy. In particular, older patients are perceived as being less able to tolerate chemotherapy well [38]. Additionally, doctors perceive that a short life expectancy may limit the benefits of chemotherapy, although it has also been shown that chemotherapy does increase the time to recurrence and overall survival in older patients [11]. Some research has provided evidence that doctors may be less likely to offer adjuvant treatments to older patients [39], and in terms of patient preferences, it has been reported that older patients more frequently decline adjuvant therapy, especially if they lack social support [6, 40]. Yellen et al. found that older patients were not less likely to accept chemotherapy than younger patients but that they were less willing to accept a greater level of toxicity in exchange for longer survival [41].

In our health system, the odds of use of both adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer and preoperative radiotherapy for rectal cancer decrease dramatically with age. This conclusion can be partially but not completely explained by a higher frequency and severity of comorbidity among older patients. Nevertheless, curative resection, tumour characteristics and social factors such as deprivation, level of education and living arrangements did not help to explain the observed differences in treatment by age. Indeed, after adjusting for all these factors, significant differences between age groups remained. Further research is required to assess the impact of the functional, cognitive and motor status of patients as well as doctors’ knowledge and attitudes and the preferences of patients and their relatives. Some studies have reported the usefulness of including geriatric assessment tools for daily clinical practice, although their application for identifying patients who are good candidates for adjuvant treatments is not clear, and further research is needed to assess the role of these tools in oncological treatment [3, 42].

Conclusions

The probability of older patients with colorectal cancer receiving adjuvant chemotherapy and preoperative radiotherapy is lower than that of younger patients and many of them are not receiving the treatments recommended by clinical practice guidelines. Differences in comorbidity, tumour characteristics, curative resection, and socioeconomic factors do not explain this lower probability of treatment. Research is needed to identify the role of physical and cognitive functional status, doctors’ attitudes, and preferences of patients and their relatives, in the use of adjuvant therapies.

Additional file

Table S1. Distribution of variables before and after imputation. (DOCX 33 kb)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the participating patients who voluntarily took part in this study. We also thank the doctors and all the interviewers from the participating hospitals (Antequera, Costa del Sol, Valme, Virgen del Rocío, Virgen de las Nieves, Canarias, Parc Taulí, Althaia Foundation, del Mar, Clínico San Carlos, La Paz, Infanta Sofía, Alcorcón Foundation, Galdakao-Usansolo, Araba, Basurto, Cruces, Donostia, Bidasoa, Mendaro, Zumárraga and Doctor Peset), for their invaluable collaboration in patient recruitment, and to the Research Committees of the participating hospitals.

The Results and Health Services Research in Colorectal Cancer (REDISECC- CARESS/CCR group):

Jose María Quintana1, Marisa Baré2, Maximino Redondo3, Eduardo Briones4, Nerea Fernández de Larrea5, Cristina Sarasqueta6, Antonio Escobar7, Francisco Rivas8, Maria Morales-Suárez9, Juan Antonio Blasco10, Isabel del Cura11, Inmaculada Arostegui12, Amaia Bilbao7, Nerea González1, Susana García-Gutiérrez1, Iratxe Lafuente1, Urko Aguirre1, Miren Orive Calzada1, Josune Martin1, Ane Antón-Ladislao1, Núria Torà13, Marina Pont13, María Purificación Martínez del14, Alberto Loizate15, Ignacio Zabalza16, José Errasti17, Antonio Gimeno18, Santiago Lázaro19, Mercè Comas20, Jose María Enríquez-Navascues21, Carlos Placer21, Amaia Perales22, Iñaki Urkidi23, Jose María Erro24, Enrique Cormenzana25, Adelaida Lacasta26, Pep Piera26, Elena Campano27, Ana Isabel Sotelo28, Segundo Gómez-Abril29, F. Medina-Cano30, Julia Alcaide31, Arturo Del Rey-Moreno32, Manuel Jesús Alcántara33, Rafael Campo34, Alex Casalots35, Carles Pericay36, Maria José Gil37, Miquel Pera37, Pablo Collera38, Josep Alfons Espinàs39, Mercedes Martínez40, Mireia Espallargues41, Caridad Almazán42, Paula Dujovne43, José María Fernández-Cebrián43, Rocío Anula44, Julio Mayol44, Ramón Cantero45, Héctor Guadalajara46, María Alexandra Heras46, Damián García46, Mariel Morey47, Alberto Colina48.

1Research Unit, Galdakao-Usansolo Hospital, Galdakao-Bizkaia/Health Services Research on Chronic Diseases Network (REDISSEC), Spain.

2Clinical Epidemiology and Cancer Screening, Corporació Sanitaria ParcTaulí,

Sabadell/REDISSEC, Spain.

3Laboratory Service, Costa del Sol Hospital, Málaga/REDISSEC, Spain.

4Epidemiology Unit, Seville Health District, Andalusian Health Service, Spain.

5Cancer and Environmental Epidemiology Unit, National Center for Epidemiology, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain/Consortium for Biomedical Research in Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBERESP), Madrid, Spain.

6Research Unit, Donostia University Hospital/Biodonostia Health Research Institute, Donostia/REDISSEC, Spain.

7Research Unit, Basurto University Hospital, Bilbao/REDISSEC, Spain.

8Epidemiology Service, Costa del Sol Hospital, Málaga/REDISSEC, Spain.

9Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, University of Valencia/Epidemiology and Public Health Networking Biomedical Research Centre (CIBERESP) - Center for Public Health Research (CSISP) - Foundation for the Promotion of Health and Biomedical Research of Valencia Region (FISABIO), Valencia, Spain.

10 Health Technology Assessment Unit, Laín Entralgo Agency, Madrid, Spain.

11Research and Teaching Support Unit, Teaching and Research Office, Planning Division, Primary Care Management, Madrid Regional Department of Health, Spain.

12Department of Applied Mathematics, Statistics and Operations Research, University of the Basque Country/REDISSEC, Spain.

13Clinical Epidemiology and Cancer Screening, Corporació Sanitaria ParcTaulí,

Sabadell/REDISSEC, Spain.

14Department of Medical Oncology, Basurto University Hospital, Bilbao, Spain.

15Department of General Surgery, Basurto University Hospital, Bilbao, Spain.

16Department of Histopathology, Galdakao-Usansolo Hospital, Galdakao, Spain.

17Department of General Surgery, Araba University Hospital, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain.

18Department of Gastroenterology, Canarias University Hospital, La Laguna, Spain.

19Department of General Surgery, Galdakao-Usansolo Hospital, Galdakao, Spain.

20Municipal Healthcare Institute (IMAS)-Hospital del Mar, Barcelona, Spain.

21Department of General and Digestive Surgery, Donostia University Hospital, Spain.

22Biodonostia Health Research Institute, Donostia, Spain.

23Department of General and Gastrointestinal Surgery, Mendaro Hospital, Spain.

24Department of General and Gastrointestinal Surgery, Zumárraga Hospital, Spain.

25Department of General and Gastrointestinal Surgery, Bidasoa Hospital, Spain.

26Department of Medical Oncology, Donostia University Hospital, Spain.

27Institute of Biomedicine of Seville (IBIS), Virgen del Rocío University Hospital, Sevilla, Spain.

28Department of Surgery, Virgen de Valme University Hospital, Sevilla, Spain.

29Department of General and Gastrointestinal Surgery, Hospital Dr.Peset, Valencia, Spain.

30Department of General and Gastrointestinal Surgery, Costa del Sol Health Agency, Marbella, Spain.

31Department of Medical Oncology, Costa del Sol Health Agency, Marbella, Spain.

32Department of Surgery, Antequera Hospital, Spain.

33Coloproctology Unit, General and Digestive Surgery Service, Corporació Sanitaria Parc Taulí, Sabadell, Spain.

34Digestive Diseases Department, Corporació Sanitaria Parc Taulí, Sabadell, Spain.

35Pathology Service, Corporació Sanitaria ParcTaulí, Sabadell, Spain.

36Medical Oncology Department, Corporació Sanitaria Parc Taulí, Sabadell/REDISSEC, Spain.

37General and Digestive Surgery Service, Parc de Salut Mar, Barcelona, Spain.

38General and Digestive Surgery Service, Althaia- Xarxa Assistencial Universitaria, Manresa, Spain.

39Catalonian Cancer Strategy Unit, Department of Health, Catalan Institute of Oncology (ICO), Barcelona.

40Medical Oncology Department, Catalan Institute of Oncology (ICO), Spain.

41Agency for Health Quality and Assessment of Catalonia (AquAS)/REDISSEC, Spain.

42Agency for Health Quality and Assessment of Catalonia (AQuAS)/CIBERESP, Spain.

43Department of General and Gastrointestinal Surgery, Alcorcón Foundation University Hospital, Madrid, Spain.

44Department of General and Gastrointestinal Surgery, San Carlos University Hospital, Madrid, Spain.

45Department of General and Gastrointestinal Surgery, Infanta Sofía University Hospital, San Sebastián de los Reyes, Madrid, Spain.

46Department of General and Gastrointestinal Surgery, La Paz University Hospital, Madrid, Spain.

47REDISSEC. Research Support Unit, Primary Care Management for the Madrid Region, Madrid, Spain.

48Department of General Surgery and Digestive Diseases, Cruces University Hospital, Barakaldo, Spain.

Abbreviations

- ASA

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- CAPOX

Capecitabine, Oxaliplatin

- CCI

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- CI

Confidence Interval

- FOLFOX

5-Fluorouracil, Oxaliplatin

- OR

Odds Ratio

Authors’ contributions

Study concepts and design: SC, QJM and REDISSEC-CARESS/CCR group. Data acquisition: SC, PA, EA, BM, RM, FN, BE, QJM and REDISSEC-CARESS/CCR group. Quality control of data and algorithms: SC, PA, QJM. Data analysis and interpretation: SC, PA, PJM and ZMV. Manuscript preparation: SC and ZMV. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by grants from the Spanish Health Research Fund (PS09/00314, PS09/00910, PS09/00746, PS09/00805, PI09/90460, PI09/90490, PI09/90397, PI09/90453, PI09/90441); Department of Health of the Basque Country (2010111098); KRONIKGUNE–Research Centre on Chronicity (KRONIK 11/006); and the European Regional Development Fund. These institutions had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; nor in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This project was approved by the following bodies in Spain (reference number of approval, when provided, in brackets): the Ethics Committees of Txagorritxu (2009–20), Galdakao, Donostia (5/09), Basurto, La Paz, Clínico San Carlos, Fundación Alcorcón and Marbella (10/09) hospitals, and the Ethics Committee of the Basque Country (PI2014084). All patients were informed of the objectives of the study and invited to voluntarily participate. Patients who agreed to participate provided written consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

C. Sarasqueta, Phone: +34 650713633, Email: cristina.sarasquetaeizaguirre@osakidetza.eus

A. Perales, Email: amaia.perales@biodonostia.org

A. Escobar, Email: antonio.escobarmartinez@osakidetza.eus

M. Baré, Email: mbare@tauli.cat

M. Redondo, Email: mredondo@hcs.es

N. Fernández de Larrea, Email: nerea.fernandez@salud.madrid.org

E. Briones, Email: eduardo.briones.sspa@juntadeandalucia.es

J. M. Piera, Email: josepmanuel.pierapibernat@osakidetza.eus

M. V. Zunzunegui, Email: maria.victoria.zunzunegui@umontreal.ca

J. M. Quintana, Email: josemaria.quintanalopez@osakidetza.eus

the REDISECC-CARESS/CCR group:

Jose María Quintana, Marisa Baré, Maximino Redondo, Eduardo Briones Pérez de la Briones, Nerea Fernández de Larrea, Cristina Sarasqueta, Antonio Escobar , Francisco Rivas, Maria Morales-Suárez, Juan Antonio Blasco, Isabel del Cura , Inmaculada Arostegui, Amaia Bilbao, Nerea González , Susana García-Gutiérrez, Iratxe Lafuente, Urko Aguirre, Miren Orive, Josune Martin, Ane Antón-Ladislao, Núria Torà, Marina Pont, María Purificación Martínez del, Alberto Loizate, Ignacio Zabalza, José Errasti, Antonio Gimeno, Santiago Lázaro, Mercè Comas, Jose María Enríquez-Navascues, Carlos Placer, Amaia Perales, Iñaki Urkidi, Jose María Erro, Enrique Cormenzana, Adelaida Lacasta, Pep Piera, Elena Campano, Ana Isabel Sotelo, Segundo Gómez-Abril, F. Medina-Cano, Julia Alcaide, Arturo Del Rey-Moreno, Manuel Jesús Alcántara, Rafael Campo, Alex Casalots, Carles Pericay, Maria José Gil, Miquel Pera, Pablo Collera, Josep Alfons Espinàs, Mercedes Martínez, Mireia Espallargues, Caridad Almazán, Paula Dujovne, José María Fernández-Cebrián, Rocío Anula, Julio Mayol, Ramón Cantero, Héctor Guadalajara, María Alexandra Heras, Damián García, Mariel Morey, and Alberto Colina

References

- 1.Chen RC, Royce TJ, Extermann M, Reeve BB. Impact of age and comorbidity on treatment and outcomes in elderly cancer patients. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2012;22:265–271. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hodgson DC, Fuchs CS, Ayanian JZ. Impact of patient and provider characteristics on the treatment and outcomes of colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:501–515. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.7.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kordatou Z, Kountourakis P, Papamichael D. Treatment of older patients with colorectal cancer: a perspective review. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2014;6:128–140. doi: 10.1177/1758834014523328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gatta G, Zigon G, Aareleid T, Ardanaz E, Bielska-Lasota M, Galceran J, et al. Patterns of care for European colorectal cancer patients diagnosed 1996-1998: a EUROCARE high resolution study. Acta Oncol. 2010;49:776–783. doi: 10.3109/02841861003782009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy CC, Harlan LC, Lund JL, Lynch CF, Geiger AM. Patterns of Colorectal Cancer Care in the United States: 1990–2010. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:djv198. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lemmens VE, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Verheij CD, Houterman S. Repelaer van Driel OJ, Coebergh JW: co-morbidity leads to altered treatment and worse survival of elderly patients with colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2005;92:615–623. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olsson LI, Granstrom F, Glimelius B. Socioeconomic inequalities in the use of radiotherapy for rectal cancer: a nationwide study. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martling A, Granath F, Cedermark B, Johansson R, Holm T. Gender differences in the treatment of rectal cancer: a population based study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:427–433. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eldin NS, Yasui Y, Scarfe A, Winget M. Adherence to treatment guidelines in stage II/III rectal cancer in Alberta. Canada Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol ) 2012;24:e9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kohne C.-H., Folprecht G., Goldberg R. M., Mitry E., Rougier P. Chemotherapy in Elderly Patients with Colorectal Cancer. The Oncologist. 2008;13(4):390–402. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2007-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lund CM, Nielsen D, Dehlendorff C, Christiansen AB, Ronholt F, Johansen JS, et al. Efficacy and toxicity of adjuvant chemotherapy in elderly patients with colorectal cancer: the ACCORE study. ESMO Open. 2016;1:e000087. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2016-000087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quaglia A, Lillini R, Mamo C, Ivaldi E, Vercelli M. Socio-economic inequalities: a review of methodological issues and the relationships with cancer survival. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;85:266–277. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aarts MJ, Lemmens VE, Louwman MW, Kunst AE, Coebergh JW. Socioeconomic status and changing inequalities in colorectal cancer? A review of the associations with risk, treatment and outcome. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2681–2695. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lemmens VE, van Halteren AH, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Vreugdenhil G. Repelaer van Driel OJ, Coebergh JW: adjuvant treatment for elderly patients with stage III colon cancer in the southern Netherlands is affected by socioeconomic status, gender, and comorbidity. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:767–772. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cavalli-Bjorkman N, Lambe M, Eaker S, Sandin F, Glimelius B. Differences according to educational level in the management and survival of colorectal cancer in Sweden. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1398–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cavalli-Bjorkman N, Qvortrup C, Sebjornsen S, Pfeiffer P, Wentzel-Larsen T, Glimelius B, et al. Lower treatment intensity and poorer survival in metastatic colorectal cancer patients who live alone. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:189–194. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quintana JM, Gonzalez N, Anton-Ladislao A, Redondo M, Bare M, de LN F, et al. Colorectal cancer health services research study protocol: the CCR-CARESS observational prospective cohort project. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:435. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2475-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esnaola S, Aldasoro E, Ruiz R, Audicana C, Perez Y, Calvo M. Desigualdades socioeconómicas en la mortalidad en la Comunidad Autónoma del País Vasco. Gac Sanit. 2006;20:16–24. doi: 10.1157/13084123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hightower CE, Riedel BJ, Feig BW, Morris GS, Ensor JE, Jr, Woodruff VD, et al. A pilot study evaluating predictors of postoperative outcomes after major abdominal surgery: physiological capacity compared with the ASA physical status classification system. Br J Anaesth. 2010;104:465–471. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faivre J, Lemmens VE, Quipourt V, Bouvier AM. Management and survival of colorectal cancer in the elderly in population-based studies. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:2279–2284. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serra-Rexach JA, Jimenez AB, Garcia-Alhambra MA, Pla R, Vidan M, Rodriguez P, et al. Differences in the therapeutic approach to colorectal cancer in young and elderly patients. Oncologist. 2012;17:1277–1285. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell NC, Elliott AM, Sharp L, Ritchie LD, Cassidy J, Little J. Impact of deprivation and rural residence on treatment of colorectal and lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:585–590. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carsin AE, Sharp L, Cronin-Fenton DP, Ceilleachair AO, Comber H. Inequity in colorectal cancer treatment and outcomes: a population-based study. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:266–274. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doat S, Thiebaut A, Samson S, Ricordeau P, Guillemot D, Mitry E. Elderly patients with colorectal cancer: treatment modalities and survival in France. National data from the ThInDiT cohort study. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:1276–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitry E, Bouvier AM, Esteve J, Faivre J. Improvement in colorectal cancer survival: a population-based study. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2297–2303. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pallis AG, Papamichael D, Audisio R, Peeters M, Folprecht G, Lacombe D, et al. EORTC elderly task force experts' opinion for the treatment of colon cancer in older patients. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Angelis R, Sant M, Coleman MP, Francisci S, Baili P, Pierannunzio D, et al. Cancer survival in Europe 1999-2007 by country and age: results of EUROCARE--5-a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:23–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sacerdote C, Baldi I, Bertetto O, Dicuonzo D, Farina E, Pagano E, et al. Hospital factors and patient characteristics in the treatment of colorectal cancer: a population based study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:775. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schrag D, Cramer LD, Bach PB. Age and adjuvant chemotherapy use after surgery for stage III Colon Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:850–857. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.11.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fata F, Mirza A, Craig G, Nair S, Law A, Gallagher J, et al. Efficacy and toxicity of adjuvant chemotherapy in elderly patients with colon carcinoma: a 10-year experience of the Geisinger medical center. Cancer. 2002;94:1931–1938. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kahn KL, Adams JL, Weeks JC, Chrischilles EA, Schrag D, Ayanian JZ, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy use and adverse events among older patients with stage III colon cancer. JAMA. 2010;303:1037–1045. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quipourt V, Jooste V, Cottet V, Faivre J, Bouvier AM. Comorbidities alone do not explain the undertreatment of colorectal cancer in older adults: a French population-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:694–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sargent D, Goldberg R, MacDonald J, Labianca R, Haller D, Shepard L. Adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer (CC) is beneficial without significantly increased toxicity in elderly patients. Proc ASCO. 2000;19.

- 35.Repetto L, Luciani A. Cancer treatment in elderly patients: evidence and clinical research. Recenti Prog Med. 2015;106:23–27. doi: 10.1701/1740.18952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aaldriks AA, van der Geest LG, Giltay EJ, le Cessie S, Portielje JE, Tanis BC, et al. Frailty and malnutrition predictive of mortality risk in older patients with advanced colorectal cancer receiving chemotherapy. J Geriatr Oncol. 2013;4:218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin CC, Bruinooge SS, Kirkwood MK, Hershman DL, Jemal A, Guadagnolo BA, et al. Association between geographic access to Cancer care and receipt of radiation therapy for rectal Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;94:719–728. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hakama M, Karjalainen S, Hakulinen T. Outcome-based equity in the treatment of colon cancer patients in Finland. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1989;5:619–630. doi: 10.1017/S0266462300008497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Newcomb PA, Carbone PP. Cancer treatment and age: patient perspectives. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:1580–1584. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.19.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoeben KW, van Steenbergen LN, van de Wouw AJ, Rutten HJ, van Spronsen DJ, Janssen-Heijnen ML. Treatment and complications in elderly stage III colon cancer patients in the Netherlands. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:974–979. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yellen SB, Cella DF, Leslie WT. Age and clinical decision making in oncology patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:1766–1770. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.23.1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Papamichael D, Audisio RA, Glimelius B, de Gramont A, Glynne-Jones R, Haller D, et al. Treatment of colorectal cancer in older patients: International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) consensus recommendations 2013. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:463–476. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Distribution of variables before and after imputation. (DOCX 33 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.