Abstract

This Letter describes the synthesis and structure activity relationship (SAR) studies of structurally novel M4 antagonists, based on a 3-(4-aryl/heteroarylsulfonyl)piperazin-1-yl)-6-(piperidin-1-yl)pyridazine core, identified from a high-throughput screening campaign. A multidimensional optimization effort enhanced potency at human M4 (hM4 IC50s < 200 nM), with only moderate species differences noted, and with enantioselective inhibition. Moreover, CNS penetration proved attractive for this series (rat brain:plasma Kp = 2.1, Kp,uu = 1.1). Despite the absence of the prototypical mAChR antagonist basic or quaternary amine moiety, this series displayed pan-muscarinic antagonist activity across M1-5 (with 9- to 16-fold functional selectivity at best). This series further expands the chemical diversity of mAChR antagonists.

Keywords: pyridazine, muscarinic acetylcholine receptor, pan-antagonist, DMPK, Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR)

Graphical abstract

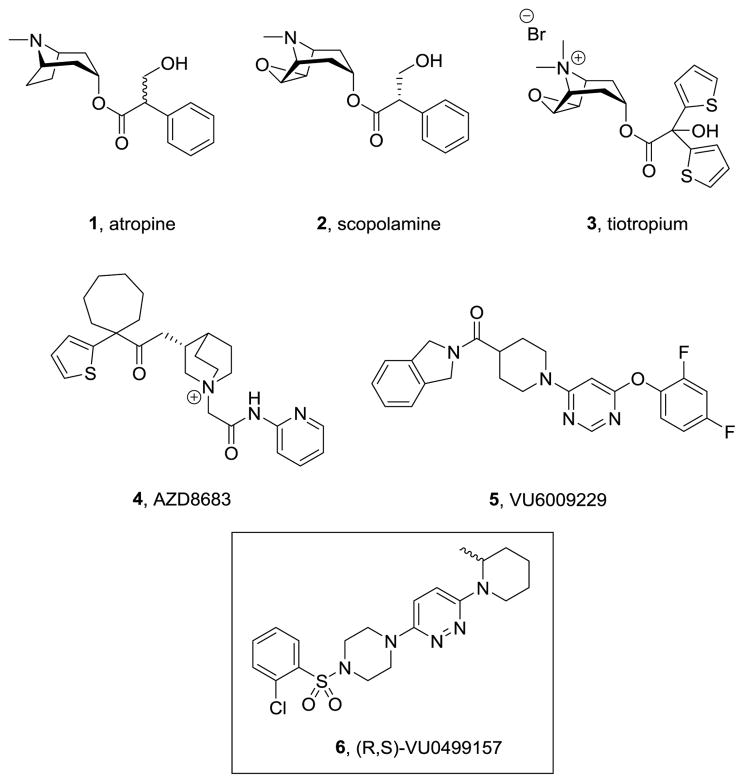

Selective inhibition of the M4 receptor, one of five muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs or M1-5), a class A family of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), has emerged as an exciting new approach for the symptomatic treatment of Parkinson’s disease.1–4 However, the development of small molecule ligands that are selective for M4, or any of the individual mAChRs, has proven to be challenging due to the high sequence homology amongst the receptor subtypes.5–8 Historically, mAChR antagonists possessed somewhat conserved chemotypes, exemplified by a basic tertiary or quaternary amine, and compounds with these functional groups represent the bulk of high-throughput screening (HTS) hits (the ‘usual suspects’) and marketed drugs 1-4 (Figure 1).9–11 Thus, we were delighted to identify fundamentally new chemotypes in an M4 functional HTS campaign, which was subsequently optimized to deliver potent and CNS penetrant antagonists such as 5; however, despite the absence of the classical pharmacophore, 5 proved to be a pan-muscarinic antagonist that bound to the orthosteric (ACh) site.12 Another departure from the classical mAChR chemotype was found in HTS hit 6, an ~ 1 μM hM4 antagonist. This Letter details the synthesis, SAR, pharmacology and DMPK profiles of analogs of 6, and the finding, once again, of pan-mAChR inhibition.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of known muscarinic antagonists 1-4, the newly optimized pan-mAChR antagonist 5, and a novel hit 6 from an M4 antagonist high-throughput screen.

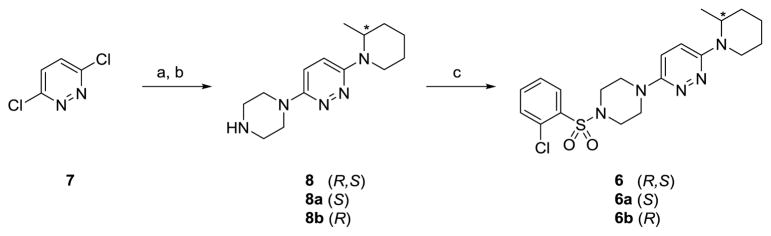

Compound 6 was resynthesized as shown in Scheme 1 as both the racemate, as well as the single (R)- and (S)-enantiomers. Briefly, 3,6-dichloropyridazine was subjected to an SNAr reaction with 2-methylpiperidine in NMP at 200 °C, followed by a second SNAr with piperazine to afford racemic 8 or chiral 8a/8b in 32–39% isolated yields in a one-pot procedure. Standard sulfonamide formation with 2-chlorobenzenesulfonyl chloride delivered racemic 6 and chiral 6a/6b in moderate yields.13

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of racemic compound 6 as well as discrete enantiomers.a

aReagents and conditions: (a) (R,S), (R) or (S)-2-methylpiperidine, DIPEA, NMP, microwave, 200 °C; (b) piperazine, 200 °C, 36% (R,S), 32% (R), 39% (S); (c) 2-chlorobenzenesulfonyl chloride, DIPEA, DCM, r.t., 38% (R,S), 35% (R), 44% (S).

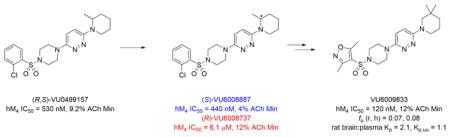

After resynthesis, racemic 6 was found to have submicromolar potency at human M4 (hM4 IC50 = 530 nM, pIC50=6.28±0.07, 9.2±5.4 % ACh Min). Excitingly, 6a, the (S)-enantiomer showed enhanced potency (hM4 IC50 = 440 nM, pIC50 = 6.37±0.08, 4±0 % ACh Min), while 6b, the (R)-enantiomer was significantly less active (hM4 IC50 = 6.08 μM, pIC50 = 5.24±0.09, 12±2 % ACh Min). Based on the unique and non-basic chemotype, coupled with the noted enantioselectivity (~14-fold) of hM4 inhibition, we anticipated that 6a would be selective for M4, akin to our related efforts on M1 and M5.14–20 Interestingly, 6a inhibited the other four mAChRs (hM1 IC50 = 1.3 μM, 2.8% ACh Min; hM2 IC50 = 1.2 μM, 2.9% ACh Min; hM3 IC50 = 7.0 μM, 4.3% ACh Min; hM5 IC50 = 6.5 μM, 3.1% ACh Min), but was moderately M4-preferring (2.7- to 16-fold). We then determined activity at rat mAChRs, and here, 6a was a weaker antagonist (rM1 IC50 = 1.4 μM, 2.6% ACh Min; rM2 IC50=5.9 uM, 7.1% ACh Min; rM3 IC50 >10 μM, 40 % ACh Min; rM4 IC50 = 1.0 μM, 4.8% ACh Min; rM5 IC50 >10uM, 37% ACh Min), only partially diminishing an EC80 of ACh at M3 and M5. While not the result we were hoping for in terms of mAChR selectivity, the series was still deemed worthy of further optimization. Figure 2 highlights the chemical optimization plan for 6a.

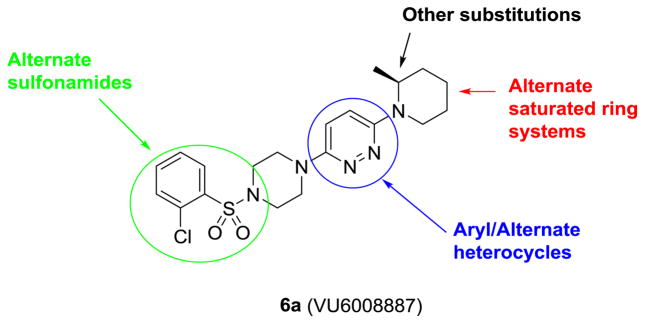

Figure 2.

Chemical optimization plan for 6a, surveying multiple dimensions of the novel mAChR antagonist chemotype.

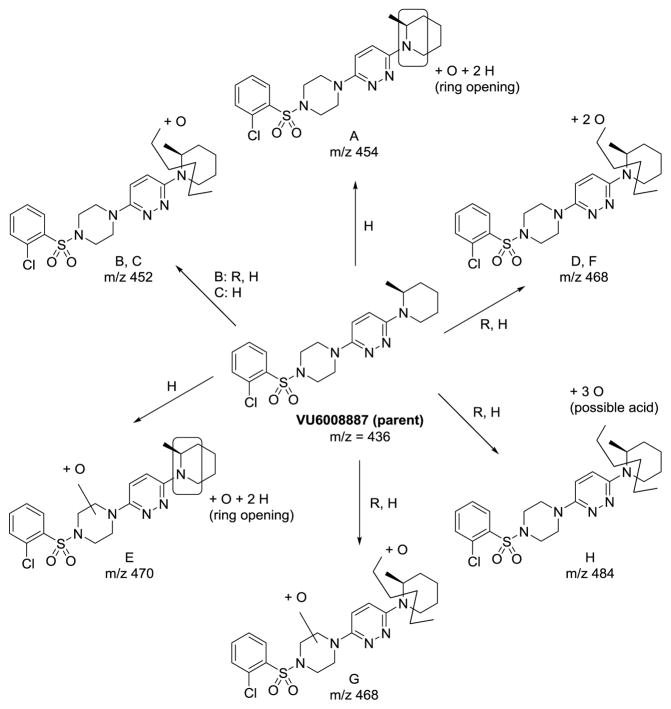

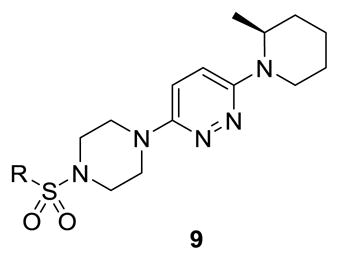

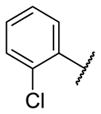

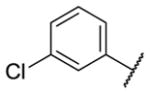

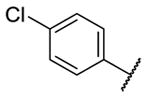

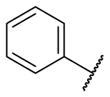

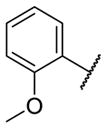

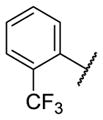

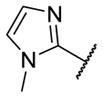

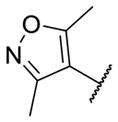

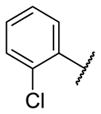

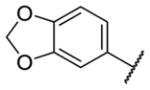

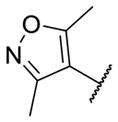

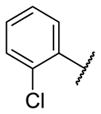

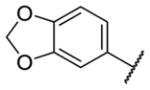

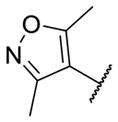

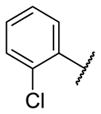

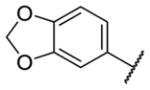

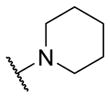

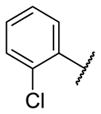

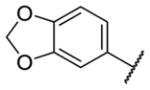

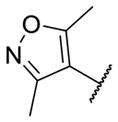

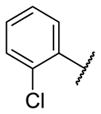

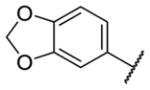

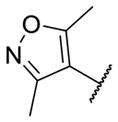

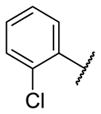

Our initial survey held the eastern portion of 6a constant while evaluating alternative sulfonamides, according to the route depicted in Scheme 1, which afforded analogs 9 (Table 1). Clear SAR was noted with analogs 9. Substitutions in the 2-position of the phenylsulfonamide were preferred, as potency decreased from 6a (hM4 IC50 = 440 nM), to the 3-Cl congener 9a (hM4 IC50 = 760 nM), and to the 4-Cl analog 9b (hM4 IC50 = 2.34 μM). Unsubstituted phenyl, 9c, was weak, as were electron-donating moieties in the 2-positon (9d). A 2-CF3 derivative (9e) was essentially equipotent to 6a. A 2,5-dimethylisoxazole (9g) afforded the best activity in this series (hM4 IC50 = 90 nM), and a piperonyl congener 9i (hM4 IC50 = 200 nM) was 10-fold more potent than a 3,4-dimethoxy analog 9j (hM4 IC50 = 2.80 μM). However, all analogs 9 (and including 6a) displayed high predicted hepatic clearance (CLhep) based on microsomal intrinsic clearance (CLint) data in both rat and human near hepatic blood flow rates (>60 mL/min/kg and >20 mL/min/kg, respectively), as well as high plasma protein binding. Based on these results, we performed metabolite identification studies in rat and human hepatic microsomes to assess soft spots and attempt to understand the high clearance, which appeared to be independent of the nature of the sulfonamide moiety. For this work, we evaluated 6a (VU6008887) in the presence and absence of NADPH, and found no NADPH-independent metabolism. 6a was more stable in human, forming 8 NADPH-dependent metabolites, but the parent remained the major species. In rat microsomes, the major peak (by UV and extracted ion chromatograms) was metabolite F, resulting from extensive oxidative metabolism of the piperidine moiety (Figure 3), and very little parent remained.

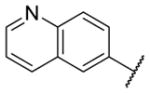

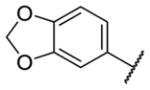

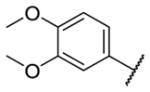

Table 1.

Structures and mAChR activities of analogs 6a, 9a-k.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R | hM4 IC50 (μM)a [% ACh Min ±SEM] | hM4 pIC50 (±SEM)a |

| 6a |

|

0.44 [4.0±0] | 6.37±0.08 |

| 9a |

|

0.76 [22±2] | 6.15±0.11 |

| 9b |

|

2.34 [30±2] | 5.64±0.05 |

| 9c |

|

2.57 [8.0±1] | 5.59±0.02 |

| 9d |

|

2.38 [11±0] | 5.62±0.02 |

| 9e |

|

0.52 [4.0±0] | 6.28±0.02 |

| 9f |

|

1.60 [8.0±0] | 5.80±0.06 |

| 9g |

|

0.09 [6.0±0] | 7.04±0.03 |

| 9h |

|

1.17 [7.0±1] | 5.95±0.09 |

| 9i |

|

0.20 [9.0±1] | 6.71±0.06 |

| 9j |

|

2.80 [46±3] | 5.58±0.10 |

| 9k |

|

4.02 [51±0] | 5.40±0.08 |

Mean of three independent determinations in a calcium mobilization assay using recombinant hM4-expressing Chinese hamster ovary cells co-transfected with chimeric Gqi5 in the presence of an ACh EC80.

Figure 3.

Metabolite identification studies in rat and human liver microsomes in the presence or absence of NADPH. No NADPH-independent metabolites were noted in either species, but rat specifically produced metabolite F.

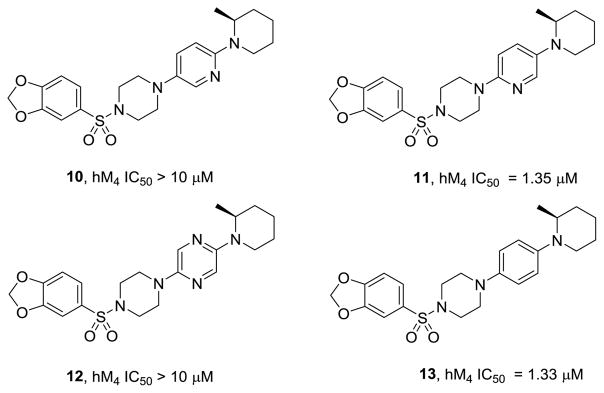

Based on these data, we first explored alternative heteroaryl replacements for the pyridazine ring, to assess if electronics could modulate metabolism of the piperidine ring (or the pendant methyl group) while maintaining M4 inhibitory activity. Employing variations of 7 in Scheme 1, the two regioisomeric pyridine cores 10 and 11 were prepared, as well as a pyrazine core 12 and a phenyl congener 13 (Figure 4). Clearly, the pyridazine of 6a and 9a-k is essential for M4 activity, and these alternate heterocyclic analogs did not provide superior compounds.

Figure 4.

Structures and activities of pyridazine replacements 10-13. Note, the parent pyridazine analog, 9i, has an hM4 IC50 of 200 nM.

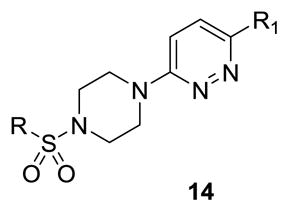

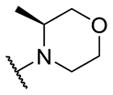

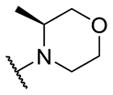

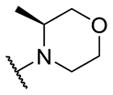

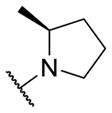

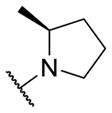

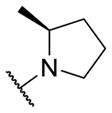

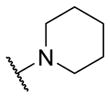

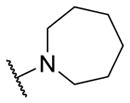

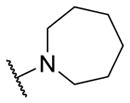

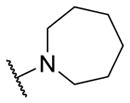

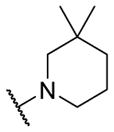

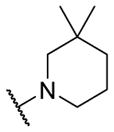

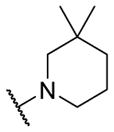

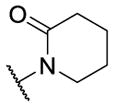

Therefore, all efforts now focused on a multidimensional array surveying the most active sulfonamide moieties (6a, 9g and 9i) in combination with replacements for the 2-methlypiperidine moiety (Table 2). SAR was steep, with chiral 2-methyl morpholine surrogates (14a-c) devoid of M4 activity (hM4 IC50s > 10 μM), as was a piperidinone (14o). Ring contraction to a chiral 2-methyl pyrrolidine as in 14d-f lost 5- to 6-fold in hM4 inhibitory activity relative to 6a, as did deletion of the chiral methyl group (14g, h). Interestingly, ring expansion to an unsubstituted homopiperidine, as in 14i-k, afforded potent hM4 antagonists (hM4 IC50s as low as 290 nM). This result led us to re-explore the piperidine core, but with a gem-dimethyl moiety in the 3-position (14l-n) to mimic the steric bulk of the homopiperidine. From this effort, 14n (hM4 IC50 = 120 nM, 12% ACh min) emerged as an attractive antagonist for further profiling, as it was also active on rat M4 (rM4 IC50 = 365 nM, pIC50 = 6.43±0.01, 32±1% ACh Min).

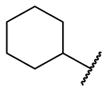

Table 2.

Structures and mAChR activities of analogs 14.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd | R | R1 | hM4 IC50 (μM)a [% ACh Min ±SEM] | hM4 pIC50 (±SEM)a |

| 14a |

|

|

>10 [56] | >5 |

| 14b |

|

|

>10 [63] | >5 |

| 14c |

|

|

>10 [66] | >5 |

| 14d |

|

|

2.90 [9.0±0] | 5.54±0.02 |

| 14e |

|

|

2.73 [14±5] | 5.59±0.12 |

| 14f |

|

|

3.31 [10±1] | 5.48±0.03 |

| 14g |

|

|

5.58 [12±1] | 5.27±0.08 |

| 14h |

|

|

0.73 [55±8] | 6.18±0.14 |

| 14i |

|

|

1.27 [6.0±0] | 5.90±0.06 |

| 14j |

|

|

0.29 [20±3] | 6.54±0.02 |

| 14k |

|

|

0.43 [8.0±1] | 6.39±0.09 |

| 14l |

|

|

0.94 [5.0±0] | 6.03±0.03 |

| 14m |

|

|

0.47 [14±2] | 6.34±0.06 |

| 14n |

|

|

0.12 [12±1] | 6.96±0.14 |

| 14o |

|

|

>10 [51] | >5 |

Mean of three independent determinations in a calcium mobilization assay using recombinant hM4-expressing Chinese hamster ovary cells co-transfected with chimeric Gqi5 in the presence of an ACh EC80.

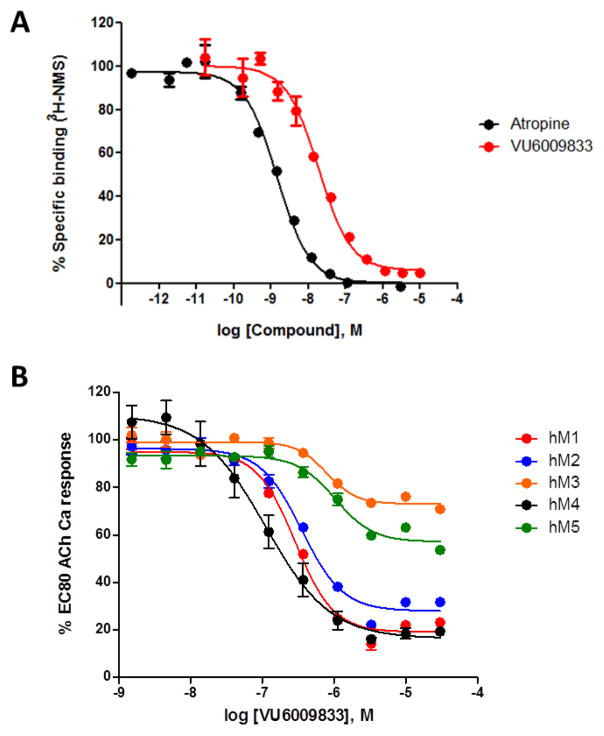

Based on the unexpected results with 5 and 6a, we next evaluated the molecular pharmacology profile of 14n (VU6009833, Figure 5). Like 5, 14n proved to bind at the orthosteric ACh site (or possibly overlapping with the orthosteric site), affording a Ki of 7.78±0.86 nM in a radioligand binding assay displacing [3H]-NMS in human M4 membranes. Compound 14n inhibited all five human mAChRs, but displayed weak, partial antagonism21,22 of M3 and M5, and was a potent full antagonist of M1 and M2 (rat data similar but not shown). Thus, like atypical pyrimidine 5, 14n represents another novel chemotype with pan-mAChR inhibitory activity.

Figure 5.

In vitro molecular pharmacology profile of 14n (VU6009833). A) Radioligand binding assay displacing [3H]-NMS in human M4 membranes. 14n afforded a Ki of 7.78±0.86 nM, while atropine, in agreement with historical data afforded a Ki of 0.64±0.09 nM. B) Concentration response curves (CRCs) for 14n in calcium mobilization assays in stably expressing hM1-5 Chinese hamster ovary cells (for Gi-coupled hM2 and hM4, co-expressed with Gqi5) in the presence of an approximate EC80 of ACh. Data are presented as the percentage of the EC80 ACh response of each cell line. All data points represent the mean of triplicate in single assay. (M1 IC50 = 288 nM (11% ACh min), M2 IC50 = 352 nM (17% ACh min), M3 IC50 = 782 nM (55% ACh min), M5 IC50 = 1,030 nM (43% ACh min).

14n possessed attractive physiochemical properties (clogP of 2.9, TPSA of 96 and a molecular weight of 434), which translated into acceptable plasma protein binding (fu (r,h) = 0.07 and 0.08) and rat brain homogenate binding (fu = 0.04). In our standard rat plasma:brain level (PBL) cassette study,23 14n displayed a Kp of 2.1 and a Kp,uu of 1.1, indicating excellent total and free CNS distribution. However, predicted hepatic clearance remained near hepatic blood flow rates in both rat and human (CLhep = 66.6 mL/min/kg and 20 mL/min/kg, respectively), suggesting that co-administration with an inhibitor of metabolism (putatively CYP450) and/or non-oral route(s) of administration may be required for in vivo studies with 14n. Currently, efforts are focused on improving metabolic stability of 14n and related analogs, as well as homology modeling and mutagenesis to better understand the mode of interaction with the ACh binding site.

In summary, an M4 HTS campaign identified 6 as a novel M4 antagonist chemotype, devoid of the ‘usual suspect’ pharmacophores. Synthesis of the discrete enantiomers indicated enantioselectivity with regards to M4 inhibition, yet this series proved to lack mAChR subtype selectivity. Further optimization afforded 14n, a potent and highly CNS penetrant pan-mAChR antagonist with attractive physiochemical properties. Additionally, 14n and related analogs do not feature either a strong basic amine or the prototypical tropane structure of classical muscarinic antagonists. Thus, these analogs represent a next generation of pan-mAChR antagonists that could serve as leads for the development of potentially safer or differentiating anti-cholinergic agents. Studies are underway to better understand the nature of the binding mode, as well as efforts to reduce metabolic clearance and ultimately improve in vivo pharmacokinetics.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH for funding via the NIH Roadmap Initiative 1X01 MH077607 (C.M.N.), the Molecular Libraries Probe Center Network (U54MH084659 to C.W.L.) and U01MH087965 (Vanderbilt NCDDG). We also thank William K. Warren, Jr. and the William K. Warren Foundation who funded the William K. Warren, Jr. Chair in Medicine (to C.W.L.). We thank Q2 Solutions’ discovery metabolism group for the contracted metabolite identification experiments and analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bernard V, Normand E, Bloch B. J Neurosci. 1992;12:3591–3600. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-09-03591.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Böhme TM, Augelli-Szafran CE, Hallak H, Pugsley T, Serpa K, Schwarz RD. J Med Chem. 2002;45:3094–3102. doi: 10.1021/jm011116o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ztaou S, Maurice N, Camon J, Guiraudie-Capraz G, Kerkerian-Le Goff L, Beurrier C, Liberge M, Amalric M. J Neurosci. 2016;36:9161–9172. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0873-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eskow Jaunarajs KL, Bonsi P, Chesselet MF, Standaert DG, Pisani A. Progress in Neurobiology. 2015;127–128:91–107. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kruse AC, Kobilka B, Gautam D, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A, Wess J. Nat Rev. 2014;13:549–560. doi: 10.1038/nrd4295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conn PJ, Christopoulos A, Lindsley CW. Nat Rev. 2009;8:41–54. doi: 10.1038/nrd2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kato M, Komamura K, Kitakaze M. Circ J. 2006;70:1658–1660. doi: 10.1253/circj.70.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mete A, Bowers K, Bull RJ, Coope H, Donald DK, Escott KJ, Ford R, Grime K, Mather A, Ray NC, Russell V. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:6248–6253. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.09.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callan MJ. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:S58–S67. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200207001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sonda S, Katayama K, Fujio M, Sakashita H, Inaba K, Asano K, Akira T. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:925–931. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitch CH, Brown TJ, Bymaster FP, Calligaro DO, Dieckman D, Merrit L, Peters SC, Quimby SJ, Shannon HE, Shipley LA, Ward JS, Hansen K, Olesen PH, Sauerberg P, Sheardown MJ, Swedberg MDB, Suzdak P, Greenwood B. J Med Chem. 1997;40:538–546. doi: 10.1021/jm9602470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bender AM, Weiner RL, Luscombe VB, Cho HP, Niswender CM, Engers DW, Bridges TM, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2017;27:2479–2483. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Representative Experimental. All reactions were carried out employing standard chemical techniques under inert atmosphere. Solvents used for extraction, washing, and chromatography were HPLC grade. All reagents were purchased from commercial sources and were used without further purification. Analytical HPLC was performed on an Agilent 1200 LCMS with UV detection at 215 nm and 254 nm along with ELSD detection and electrospray ionization, with all final compounds showing > 95% purity and a parent mass ion consistent with the desired structure. All NMR spectra were recorded on a 400 MHz Brüker AV-400 instrument. 1H chemical shifts are reported as δ values in ppm relative to the residual solvent peak (MeOD = 3.31, CDCl3 = 7.26). Data are reported as follows: chemical shift, multiplicity (br = broad, s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, m = multiplet), coupling constant (Hz), and integration. 13C chemical shifts are reported as δ values in ppm relative to the residual solvent peak (MeOD = 49.0, CDCl3 = 77.16). Low resolution mass spectra were obtained on an Agilent 1200 LCMS with electrospray ionization, with a gradient of 5–95% MeCN in 0.1% TFA water over 1.5 min. Microwave synthesis was performed on an Initiator+ by Biotage. Preparative purification (RP-HPLC) of library compounds was performed on a Gilson 215 preparative LC system.Representative synthesis of 14n: 3-(3,3-dimethylpiperidin-1-yl)-6-(piperazin-1-yl)pyridazine. 3,6-dichloropyridazine (150 mg, 1.01 mmol) and 3,3-dimethylpiperidine (137 mg, 1.21 mmol, 1.2 eq) were dissolved in NMP (3 mL) in a 5 mL microwave vial. DIPEA (0.88 mL, 5.03 mmol, 5 eq) was then added. The resulting solution was heated to 200 °C in the microwave for 1 h, after which time piperazine (651 mg, 5.03 mmol, 5 eq) was added. The resulting solution was heated to 200 °C in the microwave for 1 h, after which time solids were removed by filtration. Crude residue was purified by RP-HPLC, and fractions containing product were concentrated to give product as the TFA salt (213 mg, 54%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.82 – 7.72 (m, 2H), 3.67 (t, J = 5.2, 4H), 3.54 (t, J = 5.6, 2H), 3.26 (t, J = 5.3, 4H), 3.22 (s, 2H), 1.73 – 1.67 (m, 2H), 1.46 (t, J = 6.2, 2H), 0.90 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δ 151.77, 149.22, 126.18, 123.55, 57.20, 46.72, 42.44, 36.43, 31.79, 24.53, 21.06. LCMS (215 nm) RT = 0.317 min (>98%); m/z 276.4 [M+H]+.(14n): 4-[4-[6-(3,3-dimethyl-1-piperidyl)pyridazin-3-yl]piperazin-1-yl]sulfonyl-3,5-dimethyl-isoxazole. 3-(3,3-dimethylpiperidin-1-yl)-6-(piperazin-1-yl)pyridazine. (10 mg, 0.026 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (1 mL) and DIPEA (9 μM, 0.051 mmol, 2 eq) was added, followed by 3,5-dimethylisoxazole-4-sulfonyl chloride (8 mg, 0.039 mmol, 1.5 eq). The resulting solution was stirred at r.t. for 1 h, after which time solvents were concentrated, and crude residue was purified by RP-HPLC. Fractions containing product were basified with sat. NaHCO3, and extracted with 3:1 chloroform/IPA solution. Solvents were filtered through a phase separator and concentrated to give the title compound (3.5 mg, 31%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.93 – 6.84 (m, 2H), 3.55 (t, J = 5.0, 4H), 3.43 (t, J = 5.6, 2H), 3.20 (t, J = 5.0, 4H), 3.14 (s, 2H), 2.62 (s, 3H), 2.38 (s, 3H), 1.69 – 1.63 (m, 2H), 1.39 (t, J = 6.1, 2H), 0.92 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.95, 158.00, 156.88, 154.27, 118.04, 117.18, 113.11, 57.97, 46.37, 46.15, 44.90, 37.73, 31.21, 26.59, 21.80, 13.10, 11.47. LCMS (215 nm) RT = 0.839 min (>98%); m/z 435.4 [M+H] +

- 14.Sheffler DJ, Williams R, Bridges TM, Lewis LM, Xiang Z, Zheng F, Kane AS, Byum NE, Jadhav S, Mock MM, Zheng F, Lewis LM, Jones CK, Niswender CM, Weaver CD, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW, Conn PJ. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;76:356–368. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.056531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melancon BJ, Utley TJ, Sevel C, Mattmann ME, Cheung YY, Bridges TM, Morrison RD, Sheffler DJ, Niswender CM, Daniels JS, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW, Wood MR. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:5035–5040. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gentry PR, Kokubo M, Bridges TM, Byun N, Cho HP, Smith E, Hodder PS, Niswender CM, Daniels JS, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW, Wood MR. J Med Chem. 2014;57:7804–7810. doi: 10.1021/jm500995y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurata H, Gentry PR, Kokubo M, Cho HP, Bridges TM, Niswender CM, Byers FW, Wood MR, Daniels JS, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2015;25:690–694. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.11.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gentry PR, Kokubo M, Bridges TM, Cho HP, Smith E, Chase P, Hodder PS, Utley TJ, Rajapakse A, Byers F, Niswender CM, Morrison RD, Daniels JS, Wood MR, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. Chem Med Chem. 2014;9:1677–1682. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201402051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geanes AR, Cho HP, Nance KD, McGowan KM, Conn PJ, Jones CK, Meiler J, Lindsley CW. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2016;26:4487–4491. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.07.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGowan KM, Nance KD, Cho HP, Bridges TM, Conn PJ, Jones CK, Lindsley CW. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2017;27:1356–1359. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodriguez AL, Nong Yi, Sekaran NK, Alagille D, Tamagnan GD, Conn PJ. Mol Pharm. 2005;68:793. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.016139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma S, Kedrowski J, Rook JM, Smith JM, Jones CK, Rodriguez AL, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. J Med Chem. 2009;52:4103–4106. doi: 10.1021/jm900654c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bridges TM, Morrison RD, Byers FW, Luo S, Daniels JS. Pharm Res Perspect. 2014;2M(6):77–80. doi: 10.1002/prp2.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]