Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Patients with psoriasis are known to be at a higher risk of several comorbidities, but little is known about their risk of developing schizophrenia.

Methods:

A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort and case–control studies that reported relative risk, hazard ratio, odds ratio (OR), or standardized incidence ratio comparing risk of schizophrenia in patients with psoriasis versus subjects without psoriasis was conducted. Pooled OR and 95% confidence interval were calculated using random-effect, generic inverse-variance methods of DerSimonian and Laird.

Results:

A total of five studies (one retrospective cohort study and four case–control studies) with more than 6 million participants met the eligibility criteria and were included in this meta-analysis. The pooled OR of schizophrenia in patients with psoriasis versus subjects without psoriasis was 1.41 (95% confidence interval, 1.19–1.66). The statistical heterogeneity was low with an I2 of 33%.

Conclusion:

This systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated a significantly increased risk of schizophrenia among patients with psoriasis.

KEY WORDS: Meta-analysis, psoriasis, risk factor, schizophrenia

Introduction

Psoriasis is a common immune-mediated skin disorder that affects approximately 2%–4% of the general population.[1,2] The etiology of psoriasis is not known but is believed to be the interplay between genetic predisposition and environmental factors.[3] It has been demonstrated that patients with psoriasis have an increased prevalence of comorbidities, especially metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular diseases.[4,5,6,7] Premature atherosclerosis as a result of oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines–associated chronic inflammation of psoriasis is believed to play an essential role in this increased risk.[8,9]

Patients with psoriasis also have a higher prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities, particularly anxiety and depression.[10,11,12] A study found that the prevalence of depressive symptoms among patients with psoriasis was as high as 60%.[10] This could be the result of reduction in quality of life, psychological stress, and loss in work productivity associated with the disease[13] which could be substantial as about one-third of patients with psoriasis missed at least a day of work every month due to the illness. The estimated annual loss in productivity due to this absenteeism is almost 8 billion dollars in the United States.[14] In addition, a study has demonstrated that the negative impact on the quality of life of psoriasis is comparable to other major illnesses such as cancer, heart disease, and diabetes mellitus.[15] More recent studies have suggested that patients with psoriasis may also have a higher risk of psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia.[16,17,18,19,20] The current systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted with the aim to summarize all available evidence to better characterize the association between psoriasis and schizophrenia.

Methods

Search strategy

Two investigators (P.U. and K.W.) independently performed systematic literature review in MEDLINE and Embase database from inception to March 2018 using the search terms that comprised the terms for psoriasis and schizophrenia as described in supplementary data 1 (11.1MB, tif) . No language restriction was applied. References of selected review articles were also manually searched for additional studies.

Inclusion criteria

The eligibility criteria included the following: (1) cohort study or case–control study comparing the risk of schizophrenia between patients with psoriasis and subjects without psoriasis (i.e., for cohort study, cases were patients with psoriasis, whereas comparators were subjects without psoriasis and the outcome of interest was schizophrenia; for case–control study, cases were patients with schizophrenia, whereas controls were subjects without schizophrenia and the exposure of interest was psoriasis), (2) relative risk (RR), hazard ratio (HR), odds ratio (OR), or standardized incidence ratio (SIR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) or sufficient raw data to calculate these ratios were provided.

The two investigators (P.U. and K.W.) independently reviewed the articles and determined their eligibility. In the case that the two investigators had different opinions, the article was reviewed with the third investigator (W.C.) for the final determination of the eligibility. The quality of the included studies was assessed using Newcastle-Ottawa Score.[21] This scale assessed each study in three areas including (1) the recruitment of the participants, (2) the comparability between cases and controls, and (3) the ascertainment of the outcomes of interest for cohort study and exposures of interest for case–control study.

Data extraction

A standardized data collection form was used to extract the following information: first author's name, title of the study, year of publication, year of study, country where the study was conducted, background population, method used to identify and verify diagnosis of psoriasis and schizophrenia, number of study subjects, duration of follow-up (for cohort study), demographic data of subjects, confounders that were adjusted, and adjusted effect estimates with 95% CI. The data extraction process was also performed by the two investigators (P.U. and K.W.). Data extracted by each investigator were cross-checked for any discrepancies.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.3 software from the Cochrane Collaboration (London, UK). Point estimates from each study were combined together using the generic inverse-variance technique of DerSimonian and Laird.[22] As the outcome of interest in this study was relatively uncommon, RR from cohort study was used as an estimate for OR to calculate the pooled effect estimate with OR from case–control study. Similarly, if a cohort study reported HR (i.e., study that conducted time-to-event analysis) or SIR (i.e., study that used general population as comparators) instead of RR, the reported HR or SIR will be used as an estimate for RR. Random-effect model, rather than a fixed-effect model, was used because the underlying principle of this model that the underlying truth of each study is different due to different study designs and background populations is generally more applicable to most meta-analyses. This model would also allow a better generalization of the results. Cochran's Q test and I2 statistic were used to evaluate statistical heterogeneity. This I2 statistic quantifies the proportion of total variation across studies that is due to true heterogeneity rather than chance. A value of I2 of 0%–25% represents insignificant heterogeneity, >25% but ≤50% low heterogeneity, >50% but ≤75% moderate heterogeneity, and >75% high heterogeneity.[23] Visualization of funnel plot was used to assess publication bias.

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the recommendations from Preferred reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) which is provided as supplementary data 2 (10.4MB, tif) .

Results

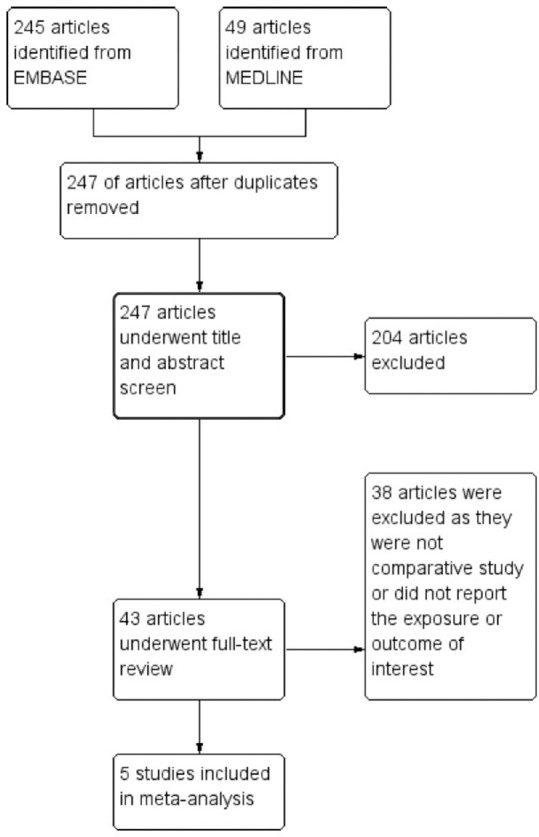

The search strategy yielded 294 potentially relevant articles (245 articles from Embase and 49 articles from MEDLINE). After exclusion of 47 duplicated articles, 247 articles underwent title and abstract review. A total 204 articles were excluded at this stage as they were clearly not cohort or case–control studies (they were case reports, review articles, editorials, or interventional studies, etc.), leaving 43 articles for full-length article review. After the full-length review, 38 articles were excluded as they were not comparative study or did not report the exposure or outcome of interest. Finally, five studies (one retrospective cohort study and four case–control studies) with more than 6 million participants were included into the meta-analysis.[16,17,18,19,20] Figure 1 outlines the systematic review process to identify the relevant studies. The characteristics and quality assessment of the included studies are provided in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Systematic literature review process

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in this meta-analysis of the association between psoriasis and schizophrenia

| Eaton et al.[16] | Benros et al.[17] | Yang et al.[18] | Chen et al.[19] | Gabilondo et al.[20] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Denmark | Denmark | Taiwan | Taiwan | Spain |

| Study design | Case-control study | Retrospective cohort study | Case-control study | Case-control study | Case-control study |

| Year of publication | 2006 | 2011 | 2011 | 2012 | 2017 |

| Number of participants | 200,294 (7,704 cases/192,590 controls) | 3.77 million | 92,700 (46,350 cases/46,350 controls) | 118,921 (10,811 cases/108,100 controls) | 2,255,406 (7,331 cases/2,248,075 controls) |

| Subjects | Cases: Patients with schizophrenia were identified from the database of 15 Danish psychiatric facilities between 1981 and 1998 Controls: Sex- and age-matched controls were randomly selected from general population through the Integrated Database for Longitudinal Labor Market Research |

Cases: Patients with psoriasis were identified from the Danish National Hospital Register between 1977 and 2006. The rest of the patients without diagnosis of autoimmune diseases in the register served as comparators. Comparators: The rest of the patients without diagnosis of psoriasis in the register served as comparators |

Cases: Patients with schizophrenia were identified from the National Health Insurance Research Database between 1997 and 2001 Controls: Sex- and age-matched controls were randomly selected from the same underlying population |

Cases: Patients with schizophrenia were identified from the National Health Insurance Research Database in 2005 Controls: Sex- and age-matched controls were randomly selected from the same underlying population |

Cases: Patients with schizophrenia were identified from the database of the Basque Health System which provides universal health coverage to all residents of Basque Country Controls: The rest of the residents in the database serve as controls |

| Diagnosis of psoriasis | Presence of diagnostic codes of psoriasis in the database | Presence of diagnostic codes of psoriasis in the database | Presence of diagnostic codes of psoriasis in the database | Presence of diagnostic codes of psoriasis in the database | Presence of diagnostic codes of psoriasis in the database |

| Diagnosis of schizophrenia | Presence of diagnostic codes of schizophrenia in the database | Presence of diagnostic codes of schizophrenia in the database | Presence of diagnostic codes of schizophrenia in the database | Presence of diagnostic codes of schizophrenia in the database | Presence of diagnostic codes of schizophrenia in the database |

| Characteristics of participants | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Sex: Cases: 45.1% female Control: 50.5% female Geography: Cases: Urban 23.1% Suburban 61.4% Rural 12.2% Unknown 3.2% Control: Urban 31.9% Suburban 57.9% Rural 7.8% Unknown 2.4% |

Sex: Cases: 39.7% female Control: 51.0% female Mean age Cases: 48.6 years Control: 43.9 years |

| Confounder adjustment | Age, sex, urbanization, socioeconomic status, and family history of schizophrenia | Age, sex, and calendar year | Age, sex, urbanization, socioeconomic status, and geographic location | Age, sex, and geographic location | Age, sex, and deprivation index |

| Quality assessment (Newcastle-Ottawa scale) | Selection: 3 Comparability: 2 Outcome: 3 |

Selection: 3 Comparability: 1 Outcome: 3 |

Selection: 3 Comparability: 2 Outcome: 3 |

Selection: 3 Comparability: 2 Outcome: 3 |

Selection: 3 Comparability: 1 Outcome: 3 |

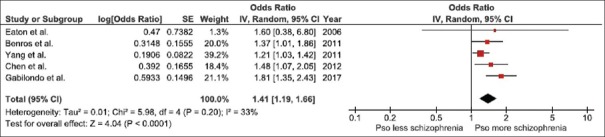

The pooled analysis of all studies demonstrated a significantly increased risk of schizophrenia in patients with psoriasis with the pooled OR of 1.41 (95% CI, 1.19–1.66). The statistical heterogeneity was low with an I2 of 33%. The forest plot of this meta-analysis is demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of this meta-analysis

To confirm the robustness of the results, jackknife sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding one study at a time from the complete analysis which gave us five different meta-analyses (each meta-analysis contained four primary studies). The pooled OR of these five meta-analyses ranged from 1.28 to 1.55 with the lower bounds of the corresponding CIs remaining above 1.0. The results of jackknife sensitivity analysis suggested that the significantly positive pooled effect estimate was a result of the included studies as whole, not driven by just one study with an outsized influence.

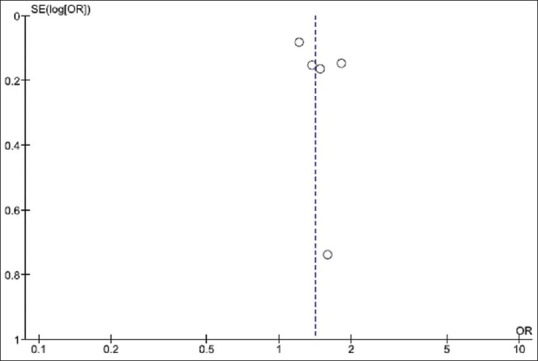

Evaluation for publication bias

Funnel plot to evaluate publication bias is demonstrated in Figure 3. The graph is symmetric and is not suggestive of the presence of publication bias in favor of studies with higher OR.

Figure 3.

Funnel plot of this meta-analysis

Discussion

This study is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to comprehensively combine all available data on the risk of schizophrenia among patients with psoriasis. A significantly elevated risk was found with 41% increased odds of schizophrenia compared with subjects without psoriasis. Sensitivity analysis showed that the results of this meta-analysis were robust and were not dependent on just one primary study. This increased risk may warrant more attention from dermatologists and other healthcare providers on psychiatric health of patients with psoriasis. Evaluation by psychiatrist may be required if patients develop any signs and symptoms of psychosis.

Why do patients with psoriasis have a higher risk of schizophrenia is not well-understood and further studies are required. Nonetheless, there are few possible explanations.

Schizophrenia is the most common psychotic disorder with unknown etiology. According to the mild encephalitis hypothesis, which is supported by studies on immunology of the brain and cerebrospinal fluid, inflammation of the central nervous system (CNS) may play a pivotal role in the initiation and perpetuation of schizophrenia in a significant subgroup of patients.[24,25,26,27] These studies also suggest a significant role of T helper (Th17) cells for the initiation and progression of the inflammation in the CNS.[24,25,26,27] Interestingly, Th17 cells and tumor necrosis factor-alpha also play an essential role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis.[28,29] Thus, it is possible that dysregulated Th17 cells could be the shared underlying etiology that predisposes patients to both conditions.

PSORS1 on chromosome 6p21.3 is a known major susceptibility locus for psoriasis.[30,31] Interestingly, a study has demonstrated that a nearby region on chromosome 6p22.1 is associated with the higher risk of schizophrenia.[32] Due to their proximity, the susceptibility genes for psoriasis and schizophrenia may be transmitted together and, thus, a higher likelihood of the two conditions occurring in the same individual.

It is also possible the apparent increased risk of schizophrenia among patients with psoriasis is the result of surveillance bias as patients with psoriasis may have more medical examinations because they have chronic illness that requires a regular follow-up. Therefore, any additional illnesses may be more likely to be recognized and diagnosed compares with those with less exposure to medical community. In fact, the case–control study by Chen et al.[19] investigated the odds of having different types of chronic illnesses among patients with schizophrenia (in comparison to individuals without schizophrenia) and found significantly increased odds of 5 chronic diseases (out of 16 examined diseases). The highest observed OR was hypersensitivity vasculitis, followed by celiac disease, pernicious anemia, psoriasis, and Grave's disease.

This study has some limitations that need to be acknowledged. The major limitation is related to the methodology of the primary studies included into the meta-analysis as all of them were coding-based medical registry study which may have a limited accuracy of disease classification. Even though the systematic review was comprehensive, the number of available studies was relatively small which could limit the precision and generalizability of the pooled results. In addition, the limited number of eligible studies would limit the utility of evaluation for publication by funnel plot. It is still possible that publication bias in favor of studies with higher OR may have been present. Finally, over half of the included studies did not provide data on the characteristics of their participants. Therefore, it is not possible to evaluate whether their participants were representative of all patients with schizophrenia which could affect the internal validity of the studies.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated a significantly increased risk of schizophrenia among patients with psoriasis. Dermatologists and other healthcare providers who take care of patients with psoriasis should be aware of this increased risk and early referral to psychiatrist may be required if signs and symptoms of psychosis are suspected.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Online Supplementary Data

Search strategy

PRISMA checklist

References

- 1.Christophers E. Psoriasis – Epidemiology and clinical spectrum. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;26:314–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oji V, Luger TA. The skin in psoriasis: Assessment and challenges. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33:S14–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrea L, Nappi F, Di Somma C, Savanelli MC, Falco A, Balato A, et al. Environmental risk factors in psoriasis: The point of view of the nutritionist. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:E743. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13070743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liakou AI, Zouboulis CC. Links and risks associated with psoriasis and metabolic syndrome. Psoriasis (Auckl) 2015;5:125–8. doi: 10.2147/PTT.S54089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ungprasert P, Sanguankeo A, Upala S, Suksaranjit P. Psoriasis and venous thromboembolism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. QJM. 2014;107:793–7. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcu073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ungprasert P, Srivali N, Kittanamongkolchai W. Psoriasis and risk of incidental atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:489–97. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.186480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu SC, Lan CE. Psoriasis and cardiovascular comorbidities: Focusing on severe vascular events, cardiovascular risk factors and implications on treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:E2211. doi: 10.3390/ijms18102211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frostegard J. Atherosclerosis in patients with autoimmune disorders. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1776–85. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000174800.78362.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montecucco F, Mach F. Common inflammatory mediators orchestrate pathophysiological processes in rheumatoid arthritis and atherosclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:11–22. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esposito M, Saraceno R, Giunta A, Maccarone M, Chimenti S. An Italian study on psoriasis and depression. Dermatology. 2006;212:123–7. doi: 10.1159/000090652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicholas MN, Gooderham M. Psoriasis, depression, and suicidality. Skin Therapy Lett. 2017;22:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tee SI, Lim ZV, Theng CT, Chan KL, Giam YC. A prospective cross-sectional study of anxiety and depression in patients with psoriasis in Singapore. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1159–64. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmitt JM, Ford DE. Role of depression in quality of life for patients with psoriasis. Dermatology. 2007;215:17–27. doi: 10.1159/000102029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmitt JM, Ford DE. Work limitations and productivity loss are associated with health-related quality of life but not with clinical severity in patients with psoriasis. Dermatology. 2006;213:102–10. doi: 10.1159/000093848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rapp SR, Feldman SR, Exum ML, Fleischer AB, Jr, Reboussin DM. Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:401–7. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eaton WW, Byrne M, Ewald H, Mors O, Chen CY, Agerbo E, et al. Association of schizophrenia and autoimmune diseases: Linkage of Danish national registers. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:521–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benros ME, Nielsen PR, Nordentoft M, Eaton WW, Dalton SO, Mortensen PB. Autoimmune diseases and severe infections as risk factors for schizophrenia: A 30-year population-based register study. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1303–10. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11030516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang YW, Lin HC. Increased risk of psoriasis among patients with schizophrenia: A nationwide population-based study. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:899–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen SJ, Chao YL, Chen CY, Chang CM, Wu ECH, Wu CS, et al. Prevalence of autoimmune diseases in in-patients with schizophrenia: Nationwide population-based study. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200:374–80. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.092098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gabilondo A, Alonso-Moran E, Nuno-Solinis R, Orueta JF, Iruin A. Comorbidities with chronic physical conditions and gender profiles of illness in schizophrenia. Results from PREST, a new health dataset. J Psychosom Res. 2017;93:102–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–5. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trial. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Na KS, Jung HY, Kim YK. The role of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the neuroinflammation and neurogenesis of schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsycopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;48:277–86. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ding M, Song X, Zhao J, Gao J, Li X, Yang G, et al. Activation of Th17 cells in drug naïve, first episode schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsycopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;51:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riedmuller R, Muller S. Ethical implications of the mild encephalitis hypothesis of schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. 8:38. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Debnath M, Berk M. Th17 pathway-mediated immunopathogenesis of schizophrenia: Mechanisms and implications. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:1412–21. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ettehadi P, Greaves MW, Wallach D, Aderka D, Camp RD. Elevated tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) biological activity in psoriatic skin lesions. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;96:146–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fitch E, Harper E, Skorcheva I, Kurtz SE, Blauvelt A. Pathophysiology of psoriasis: Recent advance on IL-23 and Th17 cytokines. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2007;9:461–7. doi: 10.1007/s11926-007-0075-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang XJ, He PP, Wang ZX, Zhang J, Li YB, Wang HY, et al. Evidence for a major psoriasis susceptibility locus at 6p21 (PSORS1) and novel candidate region at 4q31 by genome-wide scan in Chinese Hans. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:1361–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.19612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowcock AM, Barker JN. Genetics of psoriasis: The potential impact on new therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:S51–6. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(03)01135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi J, Levinson DF, Duan J, Sanders AR, Zheng Y, Pe’er I, et al. Common variants on chromosome 6p22.1 are associated with schizophrenia. Nature. 2009;460:735–57. doi: 10.1038/nature08192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Search strategy

PRISMA checklist