Abstract

Aim:

We find several interventions in palliative care to cover psychosocial needs and to relieve distress of patients. There is a growing interest in therapies using biographical approaches, but discussion about interventions is sparse, and there is no concept for comprehensive and sustainable provision. Research on interventions with a single biographical approach is available, but there is no systematic review that tests a range of interventions. Therefore, we look at all studies using biographical approaches for patients and/or caregivers.

Methods:

In May 2017, the electronic databases of Medline, PubMed, EMBASE, Central, and PsycINFO were searched for qualitative and quantitative empirical reports. Interventions for patients, dyads of patient and caregiver, and bereaved caregivers were included. Data analysis follows the guideline PRISMA.

Results:

Twenty-seven studies were included – 12 using a quantitative evaluation and 15 using a qualitative evaluation. Interventions using biographical approach are widespread and show broad variations in comprehension and performance. The scope of interest lays on patient and family in trajectory of illness and bereavement. The most common interventions used were life review, short life review, dignity therapy, and bereaved life review. Biographical approaches increase quality of life and spiritual well-being and reduce depression. Interventions show effects independently of the number of sessions or provider.

Conclusions:

Transferability of concepts seems limited due to the implications of culture on themes emerging in interventions. In some case, there were predicting factors for responders and nonresponders. Further research is needed.

Keywords: Biography, life review, narration, palliative care, terminal care

INTRODUCTION

Existential suffering,[1] expressed as or related to anxiety, mental anguish, and psychosocial suffering, is frequent in patients with life-threatening disease and requires spiritual and psychosocial support in these patients. Biography interventions can offer a coping strategy with the creation of a life narrative. In some countries such as Australia, New Zeeland, the United Kingdom, interventions are not provided by professionals but by hospice biographers.[2,3]

The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of interventions using biography addressed to either patient, caregiver, or both, regardless of the interviewer, and with a special focus on implementation.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

This systematic review was designed to evaluate interventions using a biographical approach for patients receiving palliative care and/or their family caregivers. We considered full reports concerning biographical approaches such as therapeutic life review, short-term life review, dignity therapy, and bereaved life review in English. Studies using biographical elements just for special purpose such as forgiveness or meaning were not included.

The primary outcome for the review was quality of life aspects such as spiritual well-being or reduction of depression. Studies on diseases requiring palliative care or advanced stage of life-threatening disease were included. The review used a mixed method approach, including both randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and other trials with qualitative and quantitative outcome measures. Theoretical reports or opinion papers (n = 10), single case reports (n = 1), studies on posttraumatic stress disorder (n = 1), reviews (n = 1), and two papers with a focus on health-care professionals were excluded.

Inclusion criteria

Eligible studies had to define the quality of life as outcome measure, and at least one treatment arm had to be a biographical intervention. Studies were included if they recruited participants with the following criteria and reported results from using biographical approaches:

Age 18 years or more

Participants of both sexes

In- or outpatients in provision of palliative care and/or caregiver of patients in palliative care

No psychiatric diagnosis (for example, posttraumatic stress disorder).

Search methods for identification of studies

Comprehensive searches of electronic database of Medline, PubMed, EMBASE, Central, and PsycINFO were undertaken. We also searched the reference lists of identified articles. In addition, the authors were contacted to obtain unreported data. Publications that met inclusion criteria were retrieved as full-text and qualitative studies classified along the COREQ reporting guideline[4] and quantitative according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.[5]

To identify studies, we developed a detailed search strategy [Supplementary Data 1, List of search strategies] for each electronic database and other resources. The search was restricted to publications in English language.

Medline using OVID (to May 24, 2017): search strategy as detailed in supplementary data

Central (to May 24, 2017): search strategy as detailed in supplementary data

EMBASE (to May 31, 2017): search strategy as detailed in supplementary data

PsycINFO using OVID (to May 24, 2017): search strategy as detailed in supplementary data

PubMed (to May 24, 2017): search strategy as detailed in supplementary data.

Data collection and analysis

All studies with an abstract referring to an intervention using biographical elements in palliative care were retrieved in full.

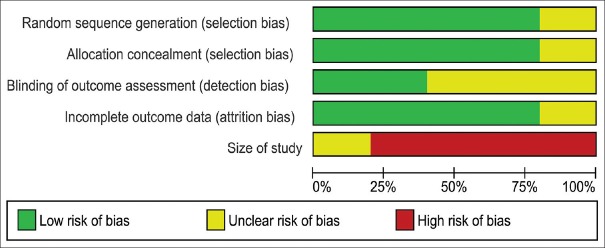

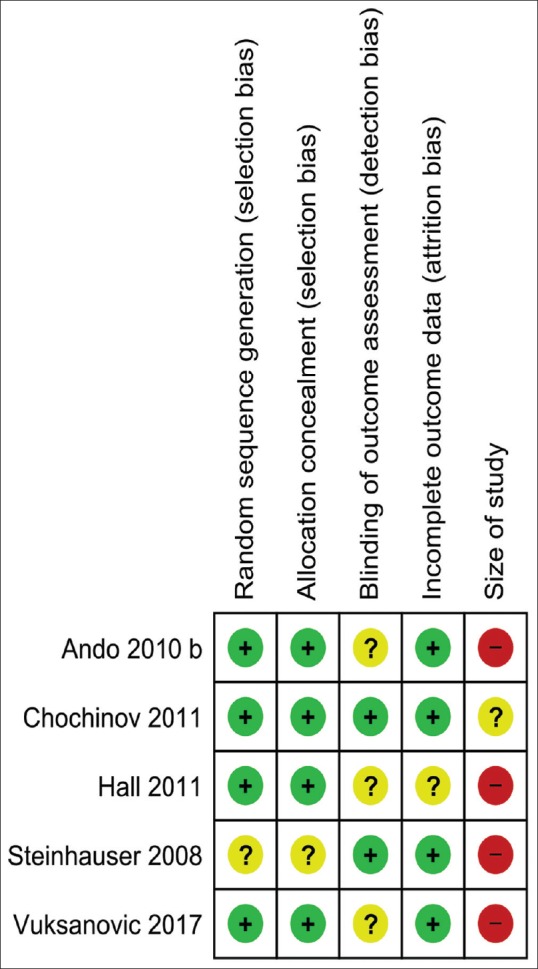

Two authors (MH and MM) independently assessed risk of bias [Figures 1 and 2] for each RCT, using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions,[5] with any disagreements resolved by discussion or by involving other review authors (LR and SF).

Figure 1.

Risk of bias graph: Review of authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item presented as percentage across all included quantitative studies

Figure 2.

Risk of bias summary: Review of authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item presented as percentage across all included randomized controlled trials

The COREQ[6] was used as a checklist for the evaluation of the methodological quality of the qualitative studies as recommended by the Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group.[7] The tool consists of 32 items – Domain 1: research team and reflexivity with 8 items, Domain 2: study design with 15 items, and Domain 3: analysis and findings with 9 items.

A spreadsheet was designed with data from each included trial. Information on study design, study size, setting, study limitations, patient characteristics, outcome measures, and results were entered and evaluated.

Quantitative data were organized using Review Manager 5 of the Cochrane Community (version 5.3, Cochrane St Albans House 57-59 Haymarket London SW1Y 4QX United Kingdom). All data from included studies were reviewed separately by two authors (MH and MM) and a subsample was cross-checked with two other authors (LR and SF). Disagreement was resolved by consensus with the other members of the review author team.

Meta-analysis

Meta-analysis was planned for each intervention using Review Manager 5. For most interventions, meta-analysis was not possible due to the wide range of methodologies and outcome parameters used in the studies. In bereaved life review, three studies from the same research group used the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being (FACIT-Sp) and the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) as outcome measures, allowing for meta-analysis of the data.

RESULTS

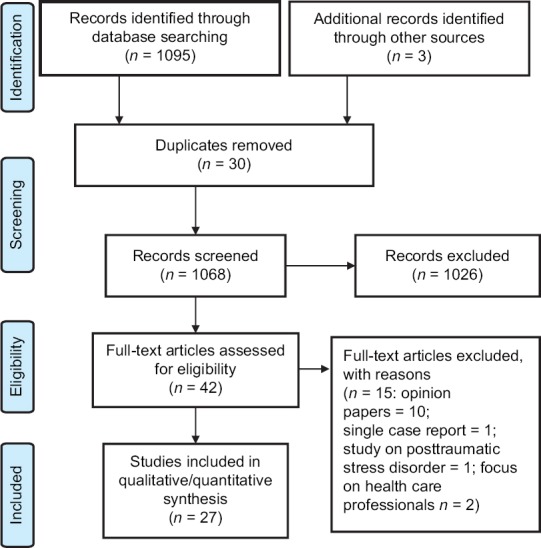

Twenty-seven studies were included – 12 using a quantitative evaluation and 15 using a qualitative evaluation. For three studies, two papers were reported on the same study protocol.[8,9,10,11,12,13] Three studies used a mixed methods approach and thus were included in both categories [Figure 3]. The most common interventions used were life review, short life review, dignity therapy, and bereaved life review.

Figure 3.

PRISMA flow diagram

Outcome measures/assessments

Outcome measures used most frequently were Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - Spiritual Well-being (FACIT-Sp) (n = 8) and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (n = 4) or Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (n = 3). Other outcome measures were Palliative Dignity Inventory (PDI) (n = 2), Skalen zur Erfassung der Lebensqualität bei Tumorkranken (SELT-M) (n = 1), Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACIT-G) (n = 1), Activities of Daily Living (ADL) (n = 1), Profile of Mood States (POMS) (n = 1), and Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD) (n = 1).

Results of quantitative studies

We found five RCTs[8,10,14,15,16] and seven observational studies[17,18,19,20,21,22,23] evaluating life review, short life review, dignity therapy, and bereaved life review. Four of these studies used a quantitative evaluation[18,19,21,23] and three[17,20,22] a mixed methods approach. Seven studies (1 RCT and 6 other studies) were from the same research team. Interventions were performed by clinical psychologist (n = 6), psychologist or palliative care nurse (n = 1), research assistant (n = 2), author (n = 2), or social worker and nurse (n = 1). Nine of 12 included quantitative evaluations showed significant results on life review, short life review, and bereaved life review improving spiritual well-being, quality of life, and reduction of depression [Table 1].

Table 1.

Quantitative studies

| Intervention | Country | Setting | Assessments | Main results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCT | |||||

| Steinhauser, et al. (2008) | Three-arm intervention at three time points: LR, forgiveness, heritage, and legacy; attention control group: Nonguided relaxation CD; true control group: No intervention | USA, North Carolina | 82 patients | ADL POMS CESD, QUAL-E | Intervention arm shows improvement in all outcomes, anxiety from 6.4 to 3.7, depression from 11.8 to 9.1, and QUAL-E from 3.4 to 3.7 |

| Ando, et al. (2010;39) | SLR; control group: General support | Japan | 68 patients | FACIT-Sp, HADS | Intervention group |

| FACIT-Sp from 17.2±6.9 to 25.5±4.9 HADS from 17.1±5.6 to 10.3±3.2 | |||||

| Control group | |||||

| FACIT-Sp from 16.7±8.6 to 13.8±7.5 HADS from 20.1±8.5 to 21.2±8.3 | |||||

| Chochinov, et al. (2011) | DT; control group: Standard PC | Canada (Winnipeg), USA New York, Australia (Perth) | 326 patients | FACIT-Sp HADS PDI SISC ESAS QOL | No significant differences between study arms. DT was significantly more likely to be experienced as helpful (χ2=35.501; P<0.001), improve quality of life (χ2=14.520; P<0.001), sense of dignity (χ2=12.655; P=0.002); change how their family sees and appreciates them (χ2=33.811; P<0.001) and be helpful to their family (χ2=33.864; P<0.001) |

| Hall, et al. (2011) | DT; control group: Standard care | London, UK | 45 patients | PDI | No differences on PDI. In the intervention group hope increased from 37.09 to 38.0 (1 week) to 37.5 (4 weeks), control group from 37.35 to 35.87 (1 week) to 35.3 (4 weeks) |

| Vuksanovic, et al. (2017) | Three-arm intervention at two time points: DT; LR; waitlist control | Australia | 70 patients | Brief Measure of Generativity and Ego-Integrity questionnaire, FACT-G PDI | DT significantly increased generativity and ego-integrity scores; FACT-G - no main effects; PDI - no significant differences; DT group had significantly higher generativity factor scores at completion of the study (95% CI 2.67, 3.41) compared with baseline (95% CI 3.52, 4.15, P<0.001). DT group had significantly higher ego-integrity scores at study completion (95% CI: 3.17, 3.77) compared with baseline (95%: CI 3.48, 4.22), P=0.01 |

| Non-RCT | |||||

| Ando, et al. (2007;15) | LR Pre-post intervention |

Japan | 12 patients | SELT-M | Two groups effective and noneffective SELT-M from 2.57±0.61 to 3.58±1.0 P=0.013 and from 2.57±0.61 to 3.14±2.25, P=0.023 |

| Ando, et al. (2008;17) | SLR Pre-post Intervention |

Japan | 30 patients | FACIT-Sp HADS NRS suffering, happiness |

FACIT-SP from 16±8.2 to 24±7.1 HADS from 17±8.6 to 9.5±5.4 |

| Ando, et al. (2010;40) | BLR Pre-post Intervention |

Japan | 21 bereaved caregivers | FACIT-Sp BDI-II |

FACIT-Sp from 19.9±5.8 to 22.8±5.1 Z=2.2, P=0.028 BDI from 10.8±7.7 to 6.8±5.8 Z=−3.0, P=0.003 |

| Ando, et al. (2012;10) | SLR Pre-post Intervention |

Japan | 34 patients | FACIT-Sp | FACIT-Sp from 17.2±6.9 to 25.5±4.9 |

| Ando, et al. (2014;31) | BLR Pre-post Intervention |

Japan | 20 bereaved caregivers | FACIT-Sp BDI-II |

BDI from 14.4±9.2 to 11.6±7.4 t=2.15, P=0.045 FACIT-Sp from 24.3±10.1 to 25.9±11 t=−1.0, P=0.341 |

| Ando, et al. (2015;13) | BLR Pre-post Intervention |

Hawaii | 20 bereaved caregivers | FACIT-Sp BDI-II |

FACIT-Sp from 34.1±9.63 to 36.3±10.6 t=−2.6, P<0.05 BDI from 11.7±7.7 to 8.8±7.0 t=2.27, P<0.05 |

| Sakaguchi, Okamura (2015) | Collage activity based on LR Pre-post intervention |

Japan | 11 cancer patients | FACIT-Sp HADS SESTC |

FACIT-SP from 25.9±8.1 to 34.9±17.5 (P=0.002), HADS score significantly decreased from 11.6±6.3 to 6.4±3.7 (P=0.026) |

LR: Life review, SLR: Short-term life review, BLR: Bereaved life review, ADL: Activities of Daily Living, POMS: Profile of Mood States, CESD: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, QUAL-E: Quality of Life at the End of Life, FACIT-SP: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being, BDI: Beck Depression Inventory, SELT-M: Skalen zur Erfassung der Lebensqualität bei Tumorkranken, HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, NRS: Numeric Rating Scale, FACT-G: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General, SESTC: Self-Efficacy Scale for Terminal Cancer, PDI: Palliative Dignity Inventory

Randomized controlled trials

RCTs[8,10,14,15,16] were evaluating life review,[8] short life review,[10] and dignity therapy.[13,14,16] The RCTs were conducted in Japan[10] on short life review and in the United States[8] on life review. Dignity therapy was evaluated in the United Kingdom,[24] in Australia,[16] and in a multi-site study in Canada, the United States, and Australia.[14] The sample size ranged from 45 to 326 patients receiving palliative care as in- and outpatients. Two of the RCTs were three-arm interventions;[8,16] the others compared the intervention with standard care. Steinhauser et al.[8] checked life review against relaxation Compact Disc and a control group with no intervention. Life review[8] as component of Outlook intervention showed improvement in all primary outcomes such as ADL, POMS, CESD, and Quality of Life at the End of Life. Chochinov et al.[14] looked at outcome measures such as FACIT-Sp, HADS, PDI, SISC, ESAS, and quality of life but found no significant differences in study arms. However, patients reported that the intervention had improved their quality of life (χ2 = 14.520, 2 df; P < 0.001) and their sense of dignity (χ2 = 12.655, 2 df; P = 0.002). Hall et al.[13] assessed the PDI and found no differences in testing dignity therapy against standard care. Vuksanovic et al.[16] compared dignity therapy with life review and a waiting-list control group. The focus of this study was evaluation of the legacy creation in dignity therapy. Dignity therapy demonstrated no significant differences in FACT-G and PDI but significantly increased scores of the Brief Measure of Generativity and Ego-Integrity. There were no differences between life review and dignity therapy intervention regarding dignity-related distress and quality of life outcomes including physical, social, emotional, and functional well-being. Short life review[10] in comparison to standard care led to significant improvements in all primary outcomes such as FACIT-Sp and HADS.

Risk of bias

From the five RCTs included in the review, 80% (4/5) were classified as low risk of bias in selection bias, 40% (2/5) as low risk in detection bias, and 80% (4/5) as low risk in attrition bias. However, 80% (4/5) were evaluated as high risk of bias concerning study size as they had fewer than 50 patients per treatment arm [Figures 1 and 2]. We defined studies with 0–2 unclear or low risks of bias to be high-quality studies, with 3–5 unclear or high risks of bias to be moderate-quality studies, and with 6–8 unclear or high risks of bias to be low-quality studies.

Observational studies

The other studies[17,18,19,20,21,22,23] were evaluating life review[17,23] with patients, short life review[18,20] with patients, and bereaved life review[19,21,22] with caregivers. Six of the single-arm interventions were conducted in Japan and only one study in the United States.[22] The sample size ranged from 11 to 34 patients or 20–21 caregivers. Independent from the number of questions, life review led to a decrease of depression and an increase of the quality of life. Studies evaluating life review[17,23] assessed spiritual well-being with FACIT-Sp and SELT-M. Ando et al.[17] classified patients in an effective and noneffective group based on scores of SELT-M. Quality of life and spiritual well-being increased significantly in the effective group. The authors identified predictors for the effectiveness of the intervention such as positive view of life, pleasure in daily activities, and good human relationships. Interventions evaluating short life review[18,20] reported an increase of spiritual well-being measured with the FACIT-Sp.

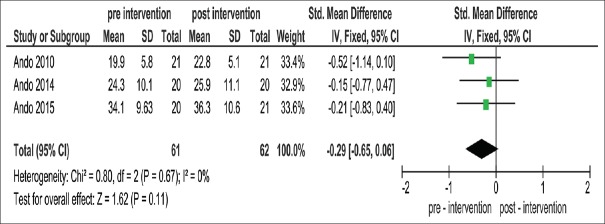

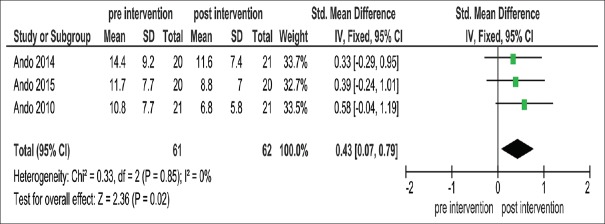

Meta-analysis

A meta-analysis was performed for the effects of bereaved life review. This analysis showed no significant effect on FACIT-Sp [standardized mean difference (SMD): 0.29, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.65–0.06; Analysis 1.1; Figure 4]. In contrast, there was a significant effect of the intervention in the BDI (SMD: 0.43, 95% CI: 0.07–0.79; Analysis 1.2; [Figures 4 and 5].

Figure 4.

Forest plot of meta-analysis of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being

Figure 5.

Forest plot of meta-analysis of the Beck Depression Inventory

Results of qualitative studies

Within the 18 included studies providing qualitative data, we found 2 reports[9,12] with qualitative evaluations from RCTs,[8,15] 15 other studies,[11,17,20,22,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35] and 1 qualitative evaluation of transcripts of dignity therapy.[36] In addition to the reports from RCTs, three studies followed a mixed methods approach.[17,20,22] Five studies evaluated life review,[9,17,25,27,33] two studies short life review,[20,26] four studies bereaved life review,[11,21,22,32] and one dignity therapy.[12] The remaining studies dealt with biographical approaches that were slightly different. A Chinese study focused on dignity in illness trajectory.[29] A study from the United States looked at reminiscing,[30] a study from Canada on a Living With Hope Program,[34] and one from the United States examined life history of disease.[35] Interventions were provided by a clinical psychologist (n = 5), psychologist or pastoral care worker (n = 1), psychologist or social worker or palliative care nurse (n = 1), social worker or palliative care nurse (n = 3), research assistant (n = 4), and author (n = 1). The sample size ranged from 11 to 45 patients, from 13 to 24 dyads of patient and caregiver, and from 19 to 20 bereaved caregivers. All patients received end-of-life care or palliative care in inpatient and outpatient settings [Table 2].

Table 2.

Qualitative studies

| Intervention | Country | Setting | Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCT | ||||

| Steinhauser, et al. (2009) | Three-arm intervention at three time points: LR, forgiveness, heritage, and legacy; attention control group: Nonguided relaxation CD; true control group: No intervention | USA, North Carolina | 18 patients | Life story: Cherished times, accomplishments/forgiveness: Things done differently, forgiveness asked, forgiveness offered, peace/heritage and legacy: Lessons learned, lessons to share with loved ones, advice to other generations, legacy |

| Hall, et al. (2013) | DT; control group: Standard care | London, UK | 45 patients and caregiver | Themes underlying DT: Generativity, continuity of self, maintenance of pride, hopefulness, and care tenor were evident in the intervention group. Just hopefulness and care tenor in the control group |

| Non-RCT | ||||

| Ando, et al. (2007;15) | LR Pre-post intervention |

Japan | 12 patients | Overall QOL score and spirituality subscale score significantly increased; effective group: Positive view of life, pleasure in daily activities, balanced evaluation of life noneffective group: Worries about future caused by disease, conflicts in family relationships, confrontation of practical problems |

| Ando, et al. (2007;5) | LR Four sessions | Japan | 16 patients | Text analysis showed differences according to age, disease stage, and gender Main concerns related to age 40 - Children 50 - How to confront death 60 - Death-related anxiety 70 - Resignation about death; evaluative reminiscence of their lives 80 - Relationships with others |

| Ando, et al. (2009;7) | SLR Pre-post intervention |

Japan, Korea, America | 43 patients 20 Japanese, 16 Koreans, 7 Americans | Japan: Good human relationships and transcendence; achievements and satisfactions; good memories and important things; bitter memories |

| Korea: Religious life; right behavior for living; strong consideration for children and will; life for living | ||||

| America: Love, pride, will; good, sweet memories; regret and feelings of loss | ||||

| Ando, et al. (2010;19) | BLR Pre-post intervention |

Japan | 21 bereaved caregivers | Division according to FACIT-Sp findings into two groups 1=Effective group (scores from 3 to 14) 2=Noneffective group (scores from −12 to <3) 1. Good memories of family; loss and reconstruction; pleasant memories of last days, 2. Suffering with memories; disagreement on funeral arrangements; regret and sense of guilt |

| Keall, et al. (2011) | LR Three sessions | Sydney Australia | 11 patients | Overarching themes: Life review, current situation, legacy/principles |

| Ando, et al. (2012;10) | SLR Pre-post intervention |

Japan | 34 patients | Findings in 20 narratives (1) Human relationships; to live in the present (2) Birth of children; pleasant memories (3) Illness; marriage, divorce (4) Company or work; raising children or education (5) Achievements at work; attitude to cope with illness (6) Message to children; getting along with others (7) To live sincerely; consideration for others (8) Stormy life; self-centered life |

| Xiao, et al. (2012) | LR Three sessions | China | 26 patients | Six categories: Accepting one’s unique life; feelings of emotional relief; bolstering A sense of meaning in life; leaving a personal legacy; making future orientations; barriers to a life review |

| Ho, et al. (2013) | Dignity interview One session | Hong Kong China | 18 patients | Two major themes to maintain dignity were identified: Personal autonomy and family connectedness |

| Ingersoll-Dayton, et al. (2013) | Reminiscing five sessions | USA Midwest | 24 couples - patient with caregiver | Positive aspects found: Dyads enjoyed reliving story of life and life story book, planned to share it with others, fostered communication, meaningful engagement, and helped memory |

| Ando, et al. (2014;31) | BLR Pre-post intervention |

Japan | 19 bereaved caregivers | The analysis of the narratives made an allocation according to the stages of TTM possible |

| Ando, et al. (2015;13) | BLR Pre-post interventions |

Hawaii | 20 bereaved caregivers | Significant improvement in spiritual well-being and significant reduction of depression; interviews: Five categories: Learning from practical caring experience, positive understanding of patients, recognition of appreciation, self-change or growth, and obtaining a philosophy |

| Ando, et al. (2015;13) | BLR Pre-post intervention |

Japan | 20 caregivers | Findings in narratives were selected into changes and value changes: 1. Learning from the deceased×s death and self-growth, 2. Healing process, 3. Relating with others, 4. Relating with society, 5. Performing new family roles/values: 1. Continuing grief work, 2. Living with a philosophy, 3. Attaining life roles, 4. Keeping good Human relationships 5. Enjoying life |

| Dahley, Sanders (2016) | LR Pre-post intervention |

USA Midwest | 15 residents and 18 family members | Six major themes of LR emerged: Affirmed prior knowledge; created a living legacy; revealed new information; opened communication; enhanced understanding of the older adult; and affirmed older adult |

| Duggleby, et al. (2016) | LWHP Pre-post intervention | Canada | 13 dyads (patients and caregivers) | LWHP fostered according to the analysis 1. Reminiscing 2. Leaving a legacy 3. Positive reappraisal 4. Motivating processes |

| Hannum, Rubinstein (2016) | Life history Three sessions | USA Baltimore | 15 patients | Illness is disrupting individual biography into three time segments: Recalled past; existent present; imagined future |

| Hack et al. (2010) | Fifty transcripts of DT | Canada and Australia | 50 patients | Main findings: “Family,” “pleasure,” “caring,” “a sense of accomplishment,” “true friendship,” and “rich experience” |

LR: Life review, SLR: Short-term life review, BLR: Bereaved life review, LWHP: Living with Hope Program

Life review was conducted in two,[17,33] three,[9,27] or four[25] sessions. Emerging themes in life review[9] were childhood, social connections (family, friends, and loved ones), and work and career. Asked about accomplishments, patients referred to their education, children, financial stability and coping with illness. Major concerns were related to age, with patients in their forties focused on children, in their sixties on death-related anxiety, and in their eighties on relationships with others.[25] Ando et al. highlighted gender-related differences. In the terminal stage of disease, men spoke about “desire for death” and “how to confront death” whereas women used phrases such as “resignation to life.” Emerging themes depended on the cultural background.[26] Americans were interested in love, pride, will, and good memories; Koreans in religious life, right behavior for living, and strong consideration for children and will; and Japanese in good human relationships, transcendence, achievements, and satisfaction. In the study of Dahley and Sanders,[33] the intervention opened the communication between patients and caregivers and enhanced understanding between the generations. Family connectedness and personal autonomy were identified as the two major themes in dignity interviews in Hong Kong.[29] Analysis of transcripts found family, pleasure, caring, a sense of accomplishment, true friendship, and rich experience as topics.[36] Hall et al.[12] reported important topics in dignity therapy such as generativity, continuity of self, maintenance of pride, hopefulness, and care tenor.

Bereaved life review led to significant improvement in spiritual well-being and significant reduction of depression.[22] Caregivers reported on practical caring experience, positive understanding of patients, and recognition of appreciation, growth, and obtaining a philosophy in the review. Changes were described[32] as learning from the relative´s death, healing process, relating with others and society, and performing new family roles.

Positive result was described in a group of responders (effective group)[17] but not in nonresponders (noneffective group) who worried about the future in relation to disease, conflicts in family relationships, and confrontation of practical problems. The effective group had a positive view and a balanced evaluation of life.

Quality of included studies

The quality of included studies was low on average based on the COREQ tool.[6] Information about research team and reflexivity was sparse. The study design was described in depth, and most studies gave detailed information about analysis and findings [Supplementary Data 1].

DISCUSSION

Our review provides an overview of interventions in palliative care using biographical approaches. There was evidence from five randomized controlled trials on the effects of life review, short life review, and dignity therapy, showing positive effects in some, but not all outcome parameters. Patients and caregivers reported improvement of quality of life, but this seemed to depend on the absence of acute conflicts and problems. Overall, the quality of the evidence has to be rated as moderate. Thematic analysis demonstrated differences in the predominant topics between patients in different countries, challenging transferability of results to other cultural settings.

There was a high variability in the interventions, with no standardization of the number of questions, number of sessions, and implementation procedures. Most interventions were developed and evaluated in single research teams. There was no comparison between different biographical approaches. This makes comparison of studies very difficult if not impossible. Palliative care is guided by the preferences and priorities of the individual patient, so lack of standardization might be an advantage. The review of Keall et al.[37] looking at quantitative life review interventions found 10 different life review interventions with patients in 14 studies. The authors evaluated the diversity of interventions positively as it allows practitioners to select a suitable intervention for their clientele. However, similar to our review, they also reported a variety of outcome measures used in the studies, even if studies were conducted in the same country.

Keall et al. reported high attrition rates due to the number of sessions so that shorter interventions fared better. Significant results in a broad range of outcome measures were found in 11 of 14 studies, and 8 of the interventions were evaluated as probably efficacious.

Relation between quantitative and qualitative results

Evaluations of biographical approaches in palliative care are complex. The qualitative studies described predicting factors for responders to life review, suggesting that biography work may be less suitable for patients grappling with unsolved conflicts and worries that may find it hard to get positive feedback from their life story while still trying to cope with overwhelming psychosocial distress.

Bereaved life review was effective in the reduction of depression but did not lead to an improvement in spiritual well-being. Qualitative evaluation linked this to suffering with memories, disagreement on funeral arrangements, and regret and sense of guilt in a group of nonresponders. This may be related to the structure of the intervention, as distress caused by these cofactors may not be resolved in an intervention with only two sessions. Coping with grief and loss may need more time and an intervention with more frequent session. These findings confirm the probability of predictors for the effectiveness of biographical interventions. Short life review was only used by one research team. In a multisite study, they found an impact of different cultures on the topics raised by the patients in the review. This suggests the assumption that transferability of interventions might not be given. The emerging themes show only little similarities. This finding might have relevance for all interventions, so that qualitative studies should evaluate cultural impact. In consequence, interventions need to be tailored. Qualitative and quantitative studies provided divergent results for dignity therapy. In comparison with standard care, dignity therapy reached higher scores of generativity and ego-integrity in controlled trials. Patients experienced the intervention as helpful for themselves and their family, with an improvement of their quality of life. However, there were no significant differences between study arms looking at the main outcome measures FACIT-Sp, PDI, and HADS. This is consistent with the results of the review of Fitchett et al.,[15] where patients also reported high benefits for themselves and their families, with improved quality of life, sense of dignity, generativity, and ego-integrity, but outcome measures such as FACIT-Sp and PDI did not show significant differences. Increase of spirituality is associated with higher well-being in general,[38] but according to the authors of the review to spirituality and well-being, this conclusion cannot be drawn. However, the lack of significance in the standardized instruments might be related to lacking sensitivity of these measures to the effects of dignity therapy rather than to a lack of effectiveness.

In the qualitative data, we found generativity, continuity of self, maintenance of pride, hopefulness, and care tenor as major topics raised by participants in the biographical intervention. This is similar to the review of Guo and Jacelon[24] who found autonomy, relieved symptom distress, respect, being self, meaningful relationships, dignified treatment, and care. Dignity therapy was always linked to leaving a legacy, but other interventions (outlook, short life review, and bereaved life review) had legacy as a component as well.

Limitations of this study

There were a number of factors limiting the comparability of results. Methodological quality was poor, for example, related to small study size. There was no consensus on study methodology nor assessment instruments and a lack of standardization of the interventions. Some interventions were only evaluated by a single research team. A significant number of studies were conducted in Japan, limiting transferability of results to other settings.

CONCLUSIONS

Psychosocial interventions are needed in palliative care as part of the holistic approach. Biographical interventions offer a therapeutic option to relieve depression, distress, and suffering. Using trained staff members with special qualifications such as psychologists or chaplains for these interventions will require a significant amount of resources.

Keall et al.[37] described life review interventions as time-consuming and costly but with the cost-saving potential to be performed by trained volunteers. Fitchett et al.[15] said that dignity therapy is an expensive intervention but also put up the question of administering dignity therapy by chaplains as specialists for spiritual care rather than generalists like nurses. Identification of cost-effective solutions, for example, with trained volunteers might be a good option for resource-poor settings. Interventions might need to be tailored to cultural perceptions and expectations. Further research is needed to explore sustainable concepts for provision and implementation.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Data 1

Supplementary Material Table 1.

Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research

| Item | Study | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |

| Domain 1: Research team and reflexivity | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1. interviewer (I) | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | N | N | ? | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | ? | ? |

| 2. credentials | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | ? |

| 3. occupation | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | Y | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 4. gender | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | Y | ? | Y | Y | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 5. Experience and training | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ? | Y | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 6. relationship established | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | N | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | Y | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 7. participant knowledge of (I) | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 8. (I) characteristics | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | Y | Y | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Domain 2: study-design | ||||||||||||||||||

| 9. methodological orientation and theory | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ? |

| 10. sampling | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 11. method of approach | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 12. sample size | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 13. non-participation | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N |

| 14. setting of data collection | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ? |

| 15. presence of non-participants | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 16. description of sample | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 17. interview guide | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N |

| 18. repeat interviews | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 19. audio/visual recording | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 20. field notes | Y | N | Y | N | N | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | Y | Y | ? | ? | ? | ? | Y | ? |

| 21. duration | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ? | Y | Y |

| 22. data saturation | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 23. transcripts returned | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| Domain 3: analysis and findings | ||||||||||||||||||

| 24. number of data coders | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N |

| 25. descriptiion of the coding tree | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N |

| 26. derivation of themes | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 27. software | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | N | ? |

| 28. participant checking | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| 29. quotations presented | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 30. data and findings consistent | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ? |

| 31. clarity of major themes | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y |

| 32. clarity of minor themes | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

Ando M, Tsuda A, Morita T. Life review interviews on the spiritual well-being of terminally ill cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2007 Feb;15(2):225-31. PubMed PMID: 16967303. Epub 2006/09/13. eng.

LR: Life review, SLR: Short-term life review, BLR: Bereaved life review, ADL: Activities of Daily Living, POMS: Profile of Mood States, CESD: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, QUAL-E: Quality of Life at the End of Life, FACIT-SP: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being, BDI: Beck Depression Inventory, SELT-M: Skalen zur Erfassung der Lebensqualität bei Tumorkranken, HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, NRS: Numeric Rating Scale, FACT-G: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General, SESTC: Self-Efficacy Scale for Terminal Cancer, PDI: Palliative Dignity Inventory

Ando M, Morita T, O’Connor SJ. Primary concerns of advanced cancer patients identified through the structured life review process: A qualitative study using a text mining technique. Palliative and Supportive Care 2007;5:265-71.

Ando M, Morita T, Ahn SH, Marquez-Wong F, Ide S. International comparison study on the primary concerns of terminally ill cancer patients in short-term life review interviews among Japanese, Koreans, and Americans. Palliat Support Care 2009;7:349-55. PubMed PMID: 19788777. Epub 2009/10/01. eng

Steinhauser KE, Alexander SC, Byock IR, George LK, Tulsky JA. Seriously ill patients’ discussions of preparation and life completion: An intervention to assist with transition at the end of life. Palliative and Supportive Care 2009;7:393-404.

Ando M, Tsuda A, Morita T. Life review interviews on the spiritual well-being of terminally ill cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2007 Feb;15(2):225-31. PubMed PMID: 16967303. Epub 2006/09/13. eng.

Hack TF, McClement SE, Chochinov HM, Cann BJ, Hassard TH, Kristjanson LJ, et al. Learning from dying patients during their final days: life reflections gleaned from dignity therapy. Palliat Med 2010;24:715-23. PubMed PMID: 20605851. Epub 2010/07/08. eng.

Keall RM, Butow PN, Steinhauser KE, Clayton JM. Discussing life story, forgiveness, heritage, and legacy with patients with life-limiting illnesses. International Journal of Palliative Nursing 2011;17:454-60. PubMed PMID: 22067737. Epub 2011/11/10. eng.

Ando M, Morita T, Akechi T, Takashi K. Factors in narratives to questions in the Short-Term Life Review interviews of terminally ill cancer patients and utility of the questions. Palliat Support Care 2012;10:83-90. PubMed PMID: 22361362. Epub 2012/03/01. eng.

Xiao H, Kwong E, Pang S, Mok E. Perceptions of a life review programme among Chinese patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Nurs 2012;21:564-72. PubMed PMID: 21923673. Epub 2011/09/20. eng.

Hall S, Goddard C, Speck PW, Martin P, Higginson IJ. “It makes you feel that somebody is out there caring”: A qualitative study of intervention and control participants’ perceptions of the benefits of taking part in an evaluation of dignity therapy for people with advanced cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2013;45:712-25.

Ho AH, Leung PP, Tse DM, Pang SM, Chochinov HM, Neimeyer RA, et al. Dignity amidst liminality: Healing within suffering among Chinese terminal cancer patients. Death Studies 2013;37:953-70. PubMed PMID: 24517523. Epub 2014/02/13. eng.

Ingersoll-Dayton B, Spencer B, Kwak M, Scherrer K, Allen RS, Campbell R. The couples life story approach: a dyadic intervention for dementia. Journal Of Gerontological Social Work 2013;56:237-54. PubMed PMID: 23548144. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC4391740. Epub 2013/04/04. eng

Ando M, Tsuda A, Morita T, Miyashita M, Sanjo M, Shima Y. A pilot study of adaptation of the transtheoretical model to narratives of bereaved family members in the bereavement life review. The American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Care 2014;31:422-7.

Ando M, Marquez-Wong F, Simon GB, Kira H, Becker C. Bereavement life review improves spiritual well-being and ameliorates depression among American caregivers. Palliat Support Care 2015;13:319-25. PubMed PMID: 24606790. Epub 2014/03/13. eng.

Ando M, Sakaguchi Y, Shiihara Y, Izuhara K. Changes experienced by and the future values of bereaved family members determined using narratives from bereavement life review therapy. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13:59-65. PubMed PMID: 24183321. Epub 2013/11/05. eng.

Dahley L, Sanders GF. Use of a structured life review and its impact on family interactions [Nursing Homes & Residential Care 3377]. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis United Kingdom; 2016 [cited 40 Allen, R. (2009). The legacy project intervention to enhance meaningful family interactions: Case examples. Clinicial Gerontologist., 32, 164-176. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07317110802677005]. 1:[53-66]. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=psyc13&NEWS=N&AN=2016-16335-004.

Duggleby W, Cooper D, Nekolaichuk C, Cottrell L, Swindle J, Barkway K. The psychosocial experiences of older palliative patients while participating in a Living with Hope Program. Palliat Support Care 2016;14:672-9. PubMed PMID: 27586308. Epub 2016/09/03. eng..

Hannum SM, Rubinstein RL. The meaningfulness of time; Narratives of cancer among chronically ill older adults. Journal of Aging Studies 2016;36:17- 25. PubMed PMID: 26880601. Pubmed Central PMCID: PMC4757851. Epub 2016/02/18. eng.

Allison Tong, Peter Sainsbury, Jonathan Craig; Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups, International Journal for Quality in Health Care, Volume 19, Issue 6, 1 December 2007, Pages 349–357. Rating: criterion fullfilled= yes = Y; criterion not fullfilled= no = N; no information in the text = ?

Medline and PsycInfo search strategy - Using OVID

A systematic review of biography in palliative care

| # | 1. | (palliati* OR palliative care OR hospice OR terminal care OR terminally ill).mp. |

| # | 2. | Story telling.mp. |

| # | 3. | reminiscene.mp. |

| # | 4. | Reminiscing.mp. |

| # | 5. | Life review.mp. |

| # | 6. | autobiographical memory.mp. |

| # | 7. | biography.mp. |

| # | 8. | life-narrative.mp. |

| # | 9. | life narrative.mp. |

| # | 10. | random*.ti,ab. |

| # | 11. | factorial*.ti,ab. |

| # | 12. | assign*.ti,ab. |

| # | 13. | allocat*.ti,ab. |

| # | 14. | evaluation study*.ti,ab. |

| # | 15. | prospective study*.ti,ab. |

| # | 16. | comparative study*.ti,ab. |

| # | 17. | qualitative study*.ti,ab. |

| # | 18. | 18 and 19 and 20 |

CENTRAL search strategy

A systematic review of biography in palliative care

| # | 1. | (palliative OR “palliative care” OR hospice OR “terminal care” OR “terminally ill”):ti,ab,kw |

| # | 2. | “Story telling” |

| # | 3. | “reminiscene” or “reminiscing” |

| # | 4. | “Life review” |

| # | 5. | “autobiographical memory” |

| # | 6. | “biography” |

| # | 7. | “life-narrative” or “life narrative” |

| # | 8. | factorial*:ti,ab |

| # | 9. | placebo*:ti,ab |

| # | 10. | assign*:ti,ab |

| # | 11. | allocat*:ti,ab |

| # | 12. | “evaluation study”:ti,ab |

| # | 13. | “prospective study”:ti,ab |

| # | 14. | “comparative study”:ti,ab |

| # | 15. | “qualitative study”:ti,ab |

| # | 16. | 2-7/OR |

| # | 17. | 8-15/OR |

| # | 18. | 16 and 17 and 1 |

EMBASE search strategy

A systematic review of biography in palliative care

| # | 1. | (palliative OR ‘palliative care’ OR hospice OR ‘terminal care’ OR ‘terminally ill’)/exp |

| # | 2. | ‘Story telling’/exp |

| # | 3. | (reminiscene or reminiscing)/exp |

| # | 4. | ‘life review’/exp |

| # | 5. | ‘autobiographical memory’/exp |

| # | 6. | biography/exp |

| # | 7. | (‘life-narrative’ or ‘life narrative’)/exp |

| # | 8. | factorial*:ti,ab |

| # | 9. | placebo*:ti,ab |

| # | 10. | assign*:ti,ab |

| # | 11. | allocat*:ti,ab |

| # | 12. | ‘evaluation study’:ti,ab |

| # | 13. | ‘prospective study’:ti,ab |

| # | 14. | ‘comparative study’:ti,ab |

| # | 15. | ‘qualitative study’:ti,ab |

| # | 16. | 2-7/OR |

| # | 17. | 8-15/OR |

| # | 18. | 16 and 17 and 1 |

Search strategy Pubmed

(palliative[All Fields] OR “palliative care”[All Fields] OR (“hospices”[MeSH Terms] OR “hospices”[All Fields] OR “hospice”[All Fields] OR “hospice care”[MeSH Terms] OR (“hospice”[All Fields] AND “care”[All Fields]) OR “hospice care”[All Fields]) OR “terminal care”[All Fields] OR “terminally ill”[All Fields]) AND (“Story telling”[All Fields] OR reminiscent[All Fields] OR reminiscing[All Fields] OR “Life review”[All Fields] OR “autobiographical memory”[All Fields] OR (“biography”[Publication Type] OR “biography as topic”[MeSH Terms] OR “biography”[All Fields]) OR “life-narrative”[All Fields])

REFERENCES

- 1.Boston P, Bruce A, Schreiber R. Existential suffering in the palliative care setting: An integrated literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41:604–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beasley E, Brooker J, Warren N, Fletcher J, Boyle C, Ventura A, et al. The lived experience of volunteering in a palliative care biography service. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13:1417–25. doi: 10.1017/S1478951515000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radbruch L, Payne S. White paper on standards and norms for hospice and palliative care in Europe: Part 1. Eur J Palliat Care. 2009;16:278–89. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dong ST, Butow PN, Tong A, Agar M, Boyle F, Forster BC, et al. Patients’ experiences and perspectives of multiple concurrent symptoms in advanced cancer: A semi-structured interview study. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:1373–86. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2913-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011. [[updated 2011 Mar] [Last accessed on 2017 May 15]]. Available from http://handbook.cochrane.org .

- 6.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flemming K, Booth A, Hannes K, Cargo M, Noyes J. Cochrane qualitative and implementation methods group guidance series-paper 6: Reporting guidelines for qualitative, implementation, and process evaluation evidence syntheses. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;97:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steinhauser KE, Alexander SC, Byock IR, George LK, Olsen MK, Tulsky JA, et al. Do preparation and life completion discussions improve functioning and quality of life in seriously ill patients? Pilot randomized control trial. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:1234–40. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinhauser KE, Alexander SC, Byock IR, George LK, Tulsky JA. Seriously ill patients’ discussions of preparation and life completion: An intervention to assist with transition at the end of life. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7:393–404. doi: 10.1017/S147895150999040X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ando M, Morita T, Akechi T, Okamoto T Japanese Task Force for Spiritual Care. Efficacy of short-term life-review interviews on the spiritual well-being of terminally ill cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:993–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.11.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ando M, Morita T, Miyashita M, Sanjo M, Kira H, Shima Y, et al. Factors that influence the efficacy of bereavement life review therapy for spiritual well-being: A qualitative analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2010;19:309–14. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-1006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall S, Goddard C, Speck PW, Martin P, Higginson IJ. “It makes you feel that somebody is out there caring”: A qualitative study of intervention and control participants’ perceptions of the benefits of taking part in an evaluation of dignity therapy for people with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45:712–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall S, Goddard C, Opio D, Speck PW, Martin P, Higginson IJ, et al. A novel approach to enhancing hope in patients with advanced cancer: A randomised phase II trial of dignity therapy. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2011;1:315–21. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2011-000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Breitbart W, McClement S, Hack TF, Hassard T, et al. Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:753–62. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70153-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fitchett G, Emanuel L, Handzo G, Boyken L, Wilkie DJ. Care of the human spirit and the role of dignity therapy: A systematic review of dignity therapy research. BMC Palliat Care. 2015;14:8. doi: 10.1186/s12904-015-0007-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vuksanovic D, Green HJ, Dyck M, Morrissey SA. Dignity therapy and life review for palliative care patients: A randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53:162–70.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ando M, Tsuda A, Morita T. Life review interviews on the spiritual well-being of terminally ill cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:225–31. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0121-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ando M, Morita T, Okamoto T, Ninosaka Y. One-week short-term life review interview can improve spiritual well-being of terminally ill cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2008;17:885–90. doi: 10.1002/pon.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ando M, Morita T, Miyashita M, Sanjo M, Kira H, Shima Y, et al. Effects of bereavement life review on spiritual well-being and depression. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:453–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ando M, Morita T, Akechi T, Takashi K. Factors in narratives to questions in the short-term life review interviews of terminally ill cancer patients and utility of the questions. Palliat Support Care. 2012;10:83–90. doi: 10.1017/S1478951511000708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ando M, Sakaguchi Y, Shiihara Y, Izuhara K. Universality of bereavement life review for spirituality and depression in bereaved families. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;31:327–30. doi: 10.1177/1049909113488928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ando M, Marquez-Wong F, Simon GB, Kira H, Becker C. Bereavement life review improves spiritual well-being and ameliorates depression among American caregivers. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13:319–25. doi: 10.1017/S1478951514000030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakaguchi S, Okamura H. Effectiveness of collage activity based on a life review in elderly cancer patients: A preliminary study. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13:285–93. doi: 10.1017/S1478951514000194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo Q, Jacelon CS. An integrative review of dignity in end-of-life care. Palliat Med. 2014;28:931–40. doi: 10.1177/0269216314528399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ando M, Morita T, O’Connor SJ. Primary concerns of advanced cancer patients identified through the structured life review process: A qualitative study using a text mining technique. Palliat Support Care. 2007;5:265–71. doi: 10.1017/s1478951507000430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ando M, Morita T, Ahn SH, Marquez-Wong F, Ide S. International comparison study on the primary concerns of terminally ill cancer patients in short-term life review interviews among Japanese, Koreans, and Americans. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7:349–55. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509990289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keall RM, Butow PN, Steinhauser KE, Clayton JM. Discussing life story, forgiveness, heritage, and legacy with patients with life-limiting illnesses. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2011;17:454–60. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2011.17.9.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiao H, Kwong E, Pang S, Mok E. Perceptions of a life review programme among Chinese patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21:564–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho AH, Leung PP, Tse DM, Pang SM, Chochinov HM, Neimeyer RA, et al. Dignity amidst liminality: Healing within suffering among Chinese terminal cancer patients. Death Stud. 2013;37:953–70. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2012.703078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ingersoll-Dayton B, Spencer B, Kwak M, Scherrer K, Allen RS, Campbell R, et al. The couples life story approach: A dyadic intervention for dementia. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2013;56:237–54. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2012.758214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ando M, Tsuda A, Morita T, Miyashita M, Sanjo M, Shima Y, et al. A pilot study of adaptation of the transtheoretical model to narratives of bereaved family members in the bereavement life review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;31:422–7. doi: 10.1177/1049909113490068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ando M, Sakaguchi Y, Shiihara Y, Izuhara K. Changes experienced by and the future values of bereaved family members determined using narratives from bereavement life review therapy. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13:59–65. doi: 10.1017/S1478951513000990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dahley L, Sanders GF. Use of a Structured Life Review and its Impact on Family Interactions. [Last accessed on 2017 Jul 24]. Available from: http://www.ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=psyc13&NEWS=N&AN=2016-16335-004 .

- 34.Duggleby W, Cooper D, Nekolaichuk C, Cottrell L, Swindle J, Barkway K, et al. The psychosocial experiences of older palliative patients while participating in a living with hope program. Palliat Support Care. 2016;14:672–9. doi: 10.1017/S1478951516000183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hannum SM, Rubinstein RL. The meaningfulness of time; narratives of cancer among chronically ill older adults. J Aging Stud. 2016;36:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hack TF, McClement SE, Chochinov HM, Cann BJ, Hassard TH, Kristjanson LJ, et al. Learning from dying patients during their final days: Life reflections gleaned from dignity therapy. Palliat Med. 2010;24:715–23. doi: 10.1177/0269216310373164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keall RM, Clayton JM, Butow PN. Therapeutic life review in palliative care: A systematic review of quantitative evaluations. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49:747–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Visser A, Garssen B, Vingerhoets A. Spirituality and well-being in cancer patients: A review. Psychooncology. 2010;19:565–72. doi: 10.1002/pon.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]