Abstract

Four terbium radioisotopes (149, 152, 155, 161Tb) constitute a potential theranostic quartet for cancer treatment but require any derived radiopharmaceutical to be essentially free of impurities. Terbium-155 prepared by proton irradiation and on-line mass separation at the CERN-ISOLDE and CERN-MEDICIS facilities contains radioactive 139Ce16O and also zinc or gold, depending on the catcher foil used. A method using ion-exchange and extraction chromatography resins in two column separation steps has been developed to isolate 155Tb with a chemical yield of ≥95% and radionuclidic purity ≥99.9%. Conversion of terbium into a form suitable for chelation to targeting molecules in diagnostic nuclear medicine is presented. The resulting 155Tb preparations are suitable for the determination of absolute activity, SPECT phantom imaging studies and pre-clinical trials.

Subject terms: Nuclear chemistry, Analytical chemistry

Introduction

Four terbium isotopes (149,152,155,161Tb) have been identified as having suitable physical properties (i.e. half-life (T1/2); emission type and quantity of emitted radiation) for use in cancer treatment and diagnosis. (Table 1)1–3. Initial pre-clinical trials1 have highlighted all four isotopes as being theranostic candidates using a folate-receptor derivative, cm09. Terbium isotopes form stable complexes with DOTA-containing targeting agents which show favourable in-vivo stability, emphasising their suitability for clinical use1,4,5. Terbium-155 (T1/2 = 5.32 d3) offers promise as an imaging tracer in single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), with initial pre-clinical studies indicating excellent image quality even at low doses4. The administration of 155Tb alongside a therapeutic terbium isotope would give a theranostic pair with identical chemical properties; this is particularly advantageous as it facilitates the application of personalised medicine.

Table 1.

| Isotope | T1/2 | Decay mode (branching ratio) | Energy of particle radiation | Energy of main γ and X-ray emissions (keV) | Application | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α therapy | PET | SPECT | β/auger therapy | |||||

| 149Tb | 4.12 h | α (16.7%) β+ (7.1%) |

Eα = 3.967 MeV Eβ+mean = 730 keV |

352 (29%) 165 (26%) |

x | x | ||

| 152Tb | 17.5 h | β+ (17%) | Eβ+mean = 1.080 MeV | 344 (64%) | x | |||

| 155Tb | 5.32 d | EC (100%) | — |

43 (86%) 49 (20%) 87 (32%) 105 (25%) |

x | |||

| 161Tb | 6.89 d | β− (100%) | Eβ-mean = 154 keV |

26 (23%) 45–46 (18%) 49 (17%) 75 (10%) |

x | x | ||

EC – electron capture; PET – positron emission tomography; SPECT – single photon emission computed tomography.

Terbium-161 can be generated via neutron activation of a 160Gd target and subsequent decay of the 161Gd product to give the desired 161Tb (160Gd(n,γ)161Gd (β−) 161Tb)5. The other isotopes (149,152,155Tb) have been produced mainly via a proton-induced spallation reaction on a tantalum target combined with on-line mass separation at the CERN-ISOLDE facility6–8. A high percentage of the 1.4 GeV protons delivered by the proton synchrotron booster do not interact with the ISOLDE targets and therefore, the CERN-MEDICIS facility was established to produce isotopes for medical applications by inducing spallation reactions in a secondary target. At CERN-MEDICIS, off-line mass separation is applied to isolate isotopes of the same A/q value6,7. Terbium-155 sources used in this study were collected after mass-separation by implantation of the ion beam (155 A/q) into zinc-coated gold foils. Further chemical separation is still required as mass separation is unable to differentiate between isobaric and pseudo-isobaric species. Removal of the foil matrix is also required.

Alternative methods of producing these isotopes have been investigated (Table 2)8–15. However, full-scale production at a radionuclide purity sufficient for clinical studies has not yet been demonstrated.

Table 2.

Established and alternative production methods for the four terbium isotopes.

| Isotope | Nuclear reactions | Production facility | Incident particle energy | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 149Tb | Ta(p,sp)149Tb | Synchrotron | 1.4 GeV (CERN) | Allen et al.8 |

| 151Eu(3He, 5n)149Tb | Cyclotron | 40–70 MeV | Zagryadskii et al.14 | |

| 152Tb | Ta(p,sp)152Tb | Synchrotron | 1.4 GeV (CERN) | Allen et al.8 |

| 155Gd(p,4n)152Tb | Cyclotron | 39 MeV | Steyn et al.9 | |

| 155Tb | Ta(p,sp)155Tb | Synchrotron | 1.4 GeV (CERN) | Allen et al.8 |

| 155Gd(p,n)155Tb | Cyclotron | 11 MeV | Vermeulen et al.13 | |

| 153Eu(ɑ,n)155Tb | Cyclotron | 28 MeV | Kazakov et al.12 | |

| 161Tb | 160Gd(n,γ)161Gd - > 161Tb | Nuclear reactor | (flux = 8 × 1014 neutrons cm−2 s−1) | Lehenberger et al.5 |

All lanthanides, especially neighbouring elements, have similar chemical properties due to small differences in their ionic size/charge ratio, making the isolation of high purity individual lanthanide solutions challenging16. They exist predominately in the III+ oxidation state under aqueous conditions. The exceptions are europium, which can be selectively reduced to Eu(II) under strongly reducing conditions, and cerium, which can be easily oxidised to Ce(IV). Changes in oxidation state markedly influence chromatographic behaviour and this can be exploited when developing separation methods.

A well-known method of separating lanthanide elements utilises cation-exchange chromatography with α-hydroxyisobutyric acid (α-HIBA) eluent and provides good separation even from neighbouring elements1,5,8. However, the process is slow and requires precise control of chemical conditions (pH and α-HIBA concentration) to give optimal yield and purity. Attempts to accelerate separation tend to compromise terbium recovery.

A significant 139Ce (T1/2 = 137.6 d17) impurity exists in 155Tb sources from CERN-ISOLDE and CERN-MEDICIS owing to formation of the pseudo-isobaric species, 139Ce16O, which cannot be removed by mass separation. Given its half-life, it constitutes an increasing proportion of overall source activity during transport and storage. In this study, we present a simple method for producing radiologically pure terbium preparations in a chemical form suitable for chelation to targeting molecules as well as for absolute activity measurements and phantom imaging studies. Our aim was to develop a robust, efficient and rapid method capable of isolating terbium from the foil matrix as well as from 139Ce by selective oxidation. Therefore, ion-exchange and extraction chromatography resins were chosen based on their selectivity for tetravalent over trivalent species.

Results

Chemical separation

Batch separation

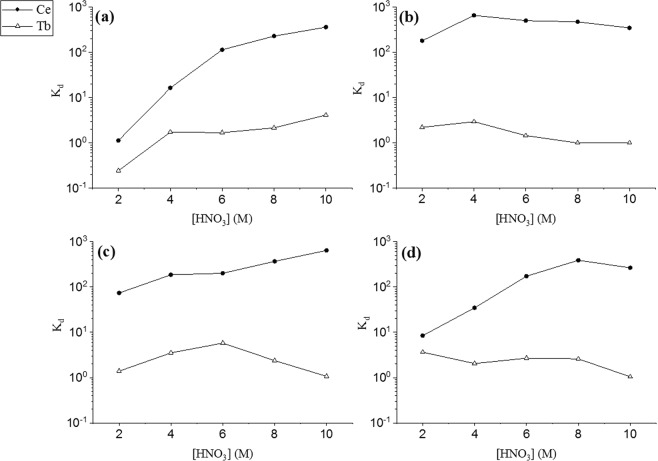

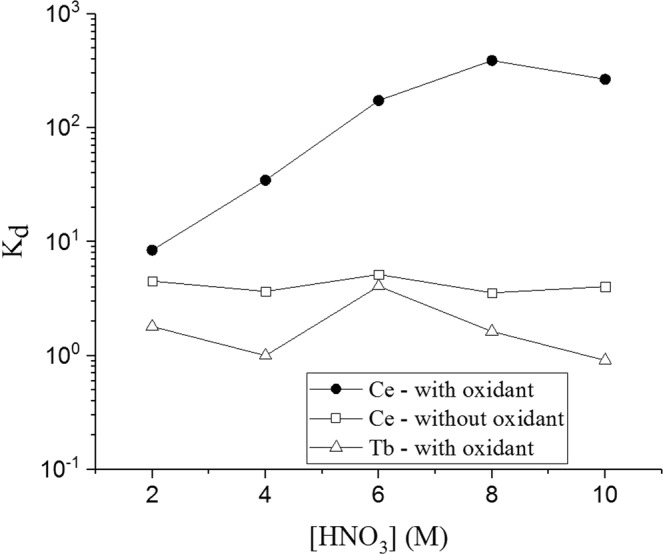

In the presence of an oxidant (sodium bromate, NaBrO3) and in HNO3 solutions commercial UTEVA, TEVA and TK100 extraction resins (Triskem International) and AG1 anion exchange resin (BioRad) all showed pronounced cerium adsorption selectivity over terbium (Fig. 1). The results imply oxidation of cerium to Ce(IV) was achieved, with terbium remaining in the trivalent state (Tb(III)).

Figure 1.

Distribution coefficients (Kd) for Ce(IV), Ce(III) and Tb(III) in HNO3 solutions on UTEVA extraction chromatography resin. (N = 3).

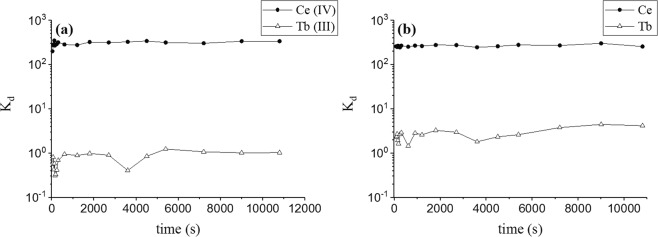

High Ce adsorption (Kd = 100–1,000) was observed at high HNO3 concentrations (8–10 M) on all four resins, whilst terbium adsorption remained minimal (Kd = 0.1–10) across the concentration range (Fig. 2). The best separation resolutions (Equation (2), SR > 100) were obtained using TEVA and UTEVA resins at high HNO3 concentrations; further studies were conducted on these resins using pre-packed cartridges.

Figure 2.

Distribution coefficients (Kd) of Ce(IV) and Tb(III) in HNO3 solutions on (a) AG1 ion exchange resin, (b) TEVA resin, (c) TK100 resin, (d) UTEVA resin. (N = 3).

Kinetic studies

UTEVA extraction chromatography resin was chosen to demonstrate kinetic behaviour with the rate of cerium adsorption studied in 10 M HNO3/0.1 M NaBrO3 solutions; rapid adsorption (<60 s) was observed (Fig. 3a). The rate of cerium oxidation was also studied in 10 M HNO3/0.1 M NaBrO3 solutions. Solutions were filtered under vacuum after a minimum of 60 s in contact with the resin. Rapid oxidation (<90 s) of cerium was observed (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Kinetics of (a) the adsorption of Ce(IV) and Tb(III) onto UTEVA resin, and (b) the oxidation of cerium using sodium bromate. Measured as the distribution coefficient (Kd) as a function of time.

Neither the rate of adsorption nor the rate of oxidation were limiting factors in the separation, suggesting that rapid column separation is achievable under these conditions.

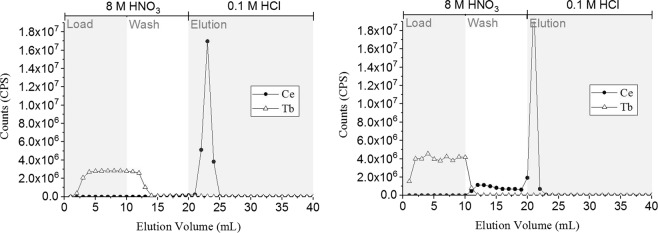

Column studies

Column-based separation using a commercially available pre-packed UTEVA cartridge (2 mL) provided effective isolation of terbium from cerium impurities. The elution profile (Fig. 4) shows that terbium (>99%) was removed in the load solution (10 mL, 8 M HNO3) and the subsequent wash solution (10 mL, 8 M HNO3) with minimal cerium impurities remaining (<0.002%). Cerium was successfully recovered by elution from the cartridge in hydrochloric solution (<10 mL, 0.1 M). The column-based separation was repeated using a pre-packed TEVA cartridge (2 mL); however, the separation achieved was less successful as ~0.1% Ce was detected in the Tb fraction under similar conditions (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Elution profiles (N = 3) for Tb and Ce from a pre-conditioned 2 mL UTEVA cartridge (left) and a pre-conditioned 2 mL TEVA cartridge (right). Approximate flow rate = 0.3 mL/min.

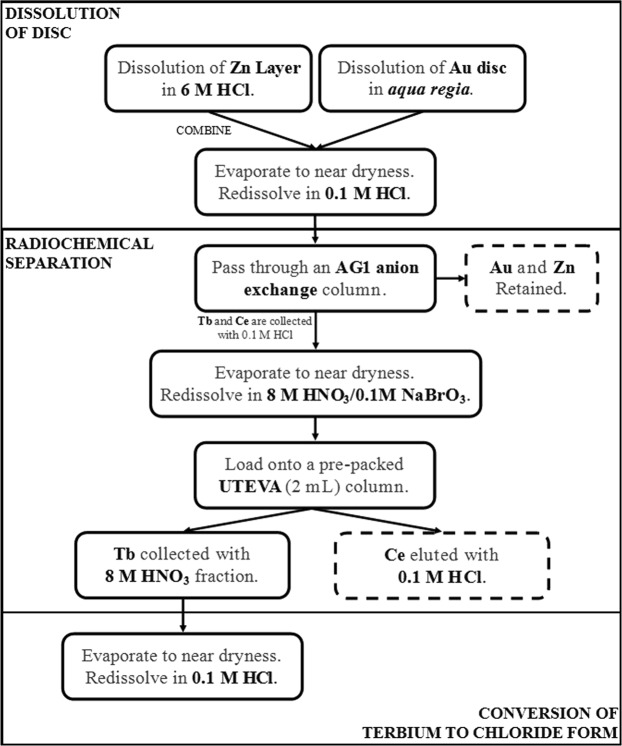

These column studies allowed the development of a separation scheme for the removal of 155Tb from both 139Ce isotopic impurities and the zinc-plated gold catcher foil matrix (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Final 155Tb separation scheme for CERN-ISOLDE and CERN-MEDICIS sources with an additional 139Ce recovery step.

Validation with active 155Tb

The method has been validated on three sources (nominal 155Tb activity Bq – MBq) over a two year period. A mass separated source received from CERN-ISOLDE in 2017 (EOB - 07/09/2017 18:42:00) contained a significant 139Ce impurity (A0(139Ce)/A0(155Tb) = 0.30 ± 0.02), Table 3). The scheme detailed in Fig. 5 removed 139Ce to the level of the Compton continuum background (DL,0(139Ce)/A0(155Tb) = 0.00021). Total terbium fraction recovery, R0,1(155Tb)/R0,2(155Tb), was 0.973+/− 0.038 with a radiochemical purity of 99.98% (Table 3). This was consistent for all validation experiments.

Table 3.

Radioisotopic composition of a 155Tb source received from CERN-ISOLDE before and after chemical separation (reference time 2017-09-29 12:00 UTC).

| Isotope | T 1/2 | Activity of material supplied (MBq) | Activity following separation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 139Ce | 136.7 d | 2.79 ± 0.068 | ≤1.90 kBq |

| 155Tb | 5.32 d | 9.28 ± 0.63 | 9.03 ± 0.049 MBq |

Discussion

In many cases, it is essential that suitable radiochemical methods are available to provide radionuclides in sufficient quantities with relatively high specific activity, radionuclidic and chemical purity to facilitate accurate pre-clinical and clinical study. The method described is able to produce high radiological purity 155Tb sources, suitable for absolute activity, nuclear data and ionisation chamber measurements. The sources are also suitable for bioconjugation, molecular chelation and SPECT imaging studies. Although the 139Ce impurity discussed here does not possess significant biological toxicity18, it is radioactive and, if not removed, would result in an unnecessary additional dose to the patient.

Currently, proton-induced spallation is the main route for producing 155Tb at CERN for (pre)-clinical studies. The chemical purification method proposed here (Fig. 5) allows the quantitative separation of 155Tb from a zinc and/or gold matrix and from 139Ce impurities produced by spallation at the CERN-ISOLDE and CERN-MEDICIS facilities. The method is rapid, simple and can also be used to recover a high purity 139Ce source; a useful standard in gamma spectrometry (Eγ = 165.86 keV, 79.90%)17.

The method has not yet been validated for the removal of other stable (e.g. 139La16O+, 155Gd+) or longer-lived, radioactive (e.g. 155Eu+) isobaric impurities; as with 139Ce16O, they would not be removed by mass separation. Such impurities might not pose a significant toxicological risk if they were to enter the body19,20 but nevertheless, would form stable complexes with DOTA (logK > 22)21 and DOTA-containing targeting molecules4 and could compete with the target terbium isotope(s), reducing their efficacy.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Standard element solutions at starting concentrations of 1000 ppm were purchased from Johnson Matthey and Fluka Analytical (Tb and Ce, respectively). Mixed standard solutions were prepared in HNO3 (Trace Analysis Grade, Fisher Scientific) and diluted to the required concentration with ultrapure water (ELGA PURELAB Flex, Veolia Water, Marlow, UK, 18 MΩ cm, <5 ppb Total Organic Carbon). Anion exchange resin (Bio Rad AG1-X8, 100–200 mesh) and extraction chromatography resins (TEVA, TK100 and UTEVA, Triskem International 100–150 μm) were used throughout.

The 155Tb source was provided by CERN-ISOLDE and CERN-MEDICIS in the form of a zinc-coated gold foil. HCl (Trace Analysis Grade, Fisher Scientific) and HNO3 were used for foil dissolution and NaBrO3 (Alfa Aesar) for cerium oxidation.

Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS)

Measurement of stable 140Ce and 159Tb was carried out using a tandem ICP-MS/MS (Agilent 8800) equipped with a collision-reaction cell positioned between two quadrupole mass filters. The instument was run in Single Quad mode, with only the second mass filter operating. The instrument is fitted with a quartz double-pass spray chamber and a MicroMist nebuliser (Glass Expansion, Melbourne, Australia) and nickel sample and skimmer cones (Crawford Scientific, South Lanarkshire, UK). It was tuned daily using a mixed 1 ppb standard solution (Ce, Co, Li, Mg, Tl and Y in 2% v/v HNO3). No additional terbium-specific tuning was carried out. A 209Bi (10 ppb solution in 2% v/v HNO3) internal standard was used to monitor and correct for instrumental drift during longer runs. Blank HNO3 (2% v/v) solutions were monitored regularly to ensure no Ce or Tb cross-contamination during a run.

Gamma-ray spectrometry

An n-type HPGe γ-ray spectrometer with a resolution (FWHM) of 1.79 keV at 1.33 MeV and relative efficiency 28% was used to determine the 139Ce/155Tb activity ratio. The detection system set-up and full-energy peak efficiency calibration is described in detail by Collins et al.22.

The nuclear data (half-lives and γ-ray emission intensities) used to determine the activities of 155Tb and 139Ce were taken from the evaluated database of ENSDF and the DDEP, respectively3,17. As 139Ce could not be observed after the chemical separation, the activity ratio of the 139Ce/155Tb in the chemically separated solution was estimated from the detection limit of the detector for 139Ce23.

Irradiation conditions and mass separation

Terbium-155 sources used in this study were produced at the CERN-ISOLDE and CERN-MEDICIS facilities. Three 155Tb sources were produced and provided to NPL for chemical separation between 2017 and 2018. The irradiation conducted at CERN-MEDICIS was as follows:

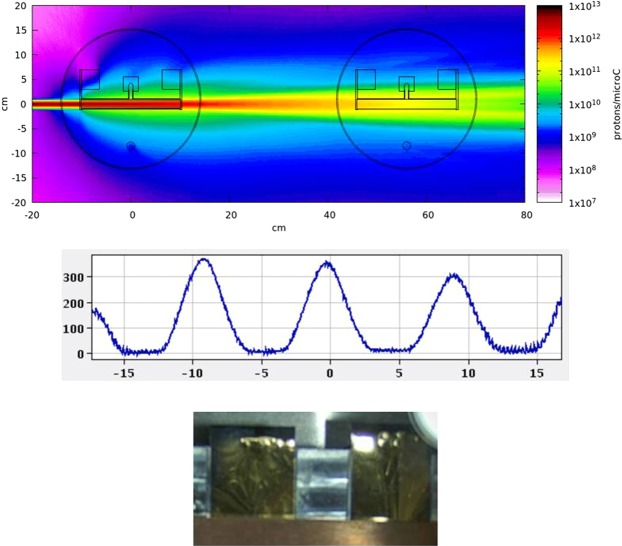

A high purity Ta metal target (Ta647M) made of 12 rolls of Ta foil (99.95% purity, 12 μm thick, 15 mm wide, 2 cm diameter) with a total mass of 357 g was arranged in a 20 cm long Ta tube coupled to a rhenium surface ion source. The target was irradiated with 1.4 GeV protons delivered by the Proton Synchrotron Booster accelerator (CERN, Geneva). The CERN-MEDICIS irradiation target is located in the High Resolution Separator (HRS) beam dump position at ISOLDE (Fig. 6), and receives a fraction of the scattered 1.8 × 1018 protons downstream from a primary HRS target (623SiC, ISOLDE physics program). The irradiation was scheduled within the MED004 approved experiment and took place from 27th September to 1st October 2018. The irradiated target was then moved to the CERN-MEDICIS isotope mass separator in order to release and extract ion species selected at mass-to-charge ratio of 1556. The separated ions were collected on a zinc-plated gold foil and removed on 3rd October. The following isotopes were implanted upon sample retrieval: 139Ce (implanted as 139Ce16O+): 6.9 MBq; 155Dy: 3.6 MBq; 155Tb: 20 MBq. Upon reception at NPL, 155Dy had decayed below the detection limit (DL,0 (155Dy) = 1.75 kBq).

Figure 6.

Top: Fluka simulation25,26 showing the incoming proton beam on an ISOLDE target (3.5 g/cm2 UCx for the purpose of the simulation) and intercepting the MEDICIS target downstream. Middle: Screenshot taken with the beam scanner, located before the implantation chamber. Beams at A/q = 154,155,156 are seen (153, 157 partly visible). The collected beam is centred on A/q = 155, while isotopes present at other masses are physically removed from the implantation using mechanical slits located ahead of the foil. The horizontal scale is in mm. Bottom: Two zinc-coated gold foils in the collection chamber seen from the rear. The collection takes place on the foil located on the left.

Chemical separation

Batch separation studies

The adsorption of Tb and Ce onto ion exchange (AG1, BioRad) and extraction chromatography resins (TEVA, UTEVA and TK100, Triskem International) was studied over a range of HNO3 solution concentrations (2–10 M). Nitric acid solutions (2 mL) containing a mixture of 100 ppb stable Ce and Tb were prepared. An aliquot was taken from each solution for ICP-MS measurement. The remaining solution was added to 0.1 g of resin (UTEVA, TEVA, TK100 or AG1). Sodium bromate (0.1 M, 0.03 g) was added to identical samples to assess changes in adsorption to the resin as a result of selective oxidation of Ce. In all cases, the samples were shaken and left to equilibrate for 24 h. After equilibration, the solutions were filtered to isolate the aqueous phase (Whatman 41 ashless filter paper, 20–25 μm pore size). An aliquot was taken from each sample, diluted with 2% HNO3 (2% v/v) and analysed by ICP-MS.

The adsorption of Tb and Ce onto each resin was quantified by calculating the distribution coefficient (Kd) using Eq. (1)24.

| 1 |

Where (CPS)0 and (CPS)t are the concentrations of analyte in the aqueous phase before and after equilibration, respectively, V is the volume of solution (mL) and m is the mass of resin used (g).

The separation achievable in the different HNO3 solutions was quantified by calculating the separation factor using Eq. (2).

| 2 |

Kinetic studies

In order to determine the rate at which Ce(IV) and Tb(III) are adsorbed onto UTEVA, a HNO3 (10 M) solution containing 100 ppb Ce, 100 ppb Tb and sodium bromate (0.1 M) was left for 24 h to allow for the oxidation of Ce(III) to Ce(IV). Aliquots (2 mL) were added to vials containing UTEVA resin (0.1 g) and were left in static conditions before being filtered to isolate the aqueous phase at regular time intervals under vacuum (60 seconds–180 minutes).

Likewise, to determine the rate at which Ce is oxidised, an excess of sodium bromate (0.1 M, 0.03 g) was added to a HNO3 solution (2 mL, 10 M) containing 100 ppb Ce, 100 ppb Tb and 0.1 g of UTEVA resin. Repeat samples were left in static conditions before being filtered to isolate the aqueous phase at regular time intervals under vacuum (90 seconds - 180 minutes).

An aliquot of each filtrate was diluted with HNO3 (2% v/v) before analysis by ICP-MS. Distribution coefficients were calculated using Eq. (1).

Column studies

Column-based separation was studied using a pre-packed 2 mL UTEVA cartridge (50–100 µm, Triskem International). The resin was pre-conditioned with 8 M HNO3 (20 mL). A HNO3 solution (10 mL, 8 M) containing 0.1 M NaBrO3, 100 ppb Tb and 100 ppb Ce was loaded onto the resin. A wash solution of 10 mL 8 M HNO3 was added to ensure removal of all Tb from the cartridge. Subsequent elution of Ce was achieved using 20 mL 0.1 M HCl. This separation method was also repeated using a pre-packed 2 mL TEVA cartridge (50–100 µm, Triskem International).

Throughout the separations, 1 mL fractions were collected, diluted with HNO3 (2% v/v) and analysed by ICP-MS in order to compile an elution profile. Column separations were carried out under gravity (approximate flow rate = 0.3 mL/min).

Method validation with active sample

Three zinc-coated gold foils containing 155Tb and 139Ce were received at NPL from CERN-ISOLDE and CERN-MEDICIS. The radionuclides were leached by dissolving the zinc layer in 20 mL 6 M HCl and the gold foil in 20 mL aqua regia. Both layers were dissolved in order to maximise the yield of terbium from the sources received. The combined solution was evaporated gently on a hot plate (~150 °C) to incipient dryness and re-dissolved in a 10 mL 8 M HNO3/0.1 M NaBrO3 solution. An ampoule was prepared for HPGe gamma spectrometry in order to quantify the activity of 155Tb and 139Ce present. After analysis, the portion was recombined with the bulk solution.

A pre-packed 2 mL UTEVA cartridge (Triskem International, 50–100 µm) was conditioned with 20 mL 8 M HNO3. The 10 mL sample was then loaded onto the column and the fraction collected under gravity. The column was washed with 10 mL 8 M HNO3. This fraction was collected, under gravity, and combined with the load fraction. The combined fractions were evaporated gently on a hot plate (~150 °C) to incipient dryness and re-dissolved in 20 mL 0.1 M HCl.

An ampoule of the combined terbium fractions was prepared and analysed by HPGe gamma spectrometry in order to assess the resultant purity of the 155Tb source after separation. The terbium recovery was calculated as follows:

| 3 |

where R0,1 and R0,2 are the count rates of the 105 keV gamma-ray emission before and after separation of the 139Ce, respectively at the reference time 2017-09-29 12:00 UTC. N1 and N2 are the net peak areas of the 105 keV full-energy peak measured before and after separation, ΔtL,1 and ΔtL,1 are the measurement live times, m1 and m2 are the measured active masses of solution, mD and mE are the total mass of solution used to dissolve the Zn layer of the target and eluent used in the chemical separation, respectively, λ is the decay constant of 155Tb, t1 and t2 are the time elapsed since the reference time and Δt1 and Δt2 are the measurement real times.

Conclusion

A novel method has been developed for the isolation of 155Tb from sources produced at CERN-ISOLDE and CERN-MEDICIS, currently the main producers of the isotope. A high purity 155Tb preparation was successfully recovered from a zinc-coated gold matrix and from 139Ce impurities using a chromatography-based system. The method was shown to be capable of separating 100 ppb Tb and Ce in a 10 mL solution, equivalent to ~6 GBq 155Tb and ~0.25 GBq 139Ce. The radiologically pure 155Tb preparation was subsequently used for absolute activity measurements and ion chamber measurements. The preparations are also suitable for phantom imaging and pre-clinical studies.

Acknowledgements

B.W.’s participation was facilitated by a PhD studentship co-sponsored by the University of Surrey and the National Physical Laboratory. The National Physical Laboratory is operated by NPL Management Ltd, a wholly-owned company of the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS). We gratefully recognise Chris Gilligan of AWE plc. for useful discussions regarding the chemical separation of the lanthanide elements. T.S. would like to thank the team involved in the preparation, operation and shipping of the isotope collection at CERN-MEDICIS. U.K. would also like to thank the team involved in the preparation, operation and shipping of the isotope collection at CERN-ISOLDE and the ISOLDE RILIS team who provided the smooth operation of the laser ion source. The collections at CERN-ISOLDE were supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 654002 (ENSAR2 project).

Author Contributions

B.W., P.I. and B.R. contributed the overall ideas and towards the design of the chemical separation procedure. B.W. wrote the majority of text in this manuscript and compiled the figures and tables. S.C. provided information and spectra associated with gamma spectrometry analysis. B.R. provided information with regard to ICP-MS analysis and both B.R. and P.I. assisted with active experimental work. T.S., J.P.R. and U.K. provided information regarding the production process at CERN-MEDICIS including Figure 6. All authors reviewed the manuscript and helped with editorial input.

Data Availability

The data generated and analysed during this study are available, upon reasonable request, from the corresponding author.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Müller C, et al. A unique matched quadruplet of terbium radioisotopes for PET and SPECT and for α- and β–radionuclide therapy: An in vivo proof-of-concept study with a new receptor-targeted folate derivative. J. Nucl. Med. 2012;53:1951–1959. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.107540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sonzogni, A., Brookhaven National Laboratory. Evaluated nuclear structure data file search and retrieval (ENSDF), https://www.nndc.bnl.gov/ensdf/ (2018).

- 3.BIPM. Monographie BIPM-5 – Table of Radionuclide, Seven Volumes, CEA/LNE-LNHB, 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France and BIPM, Pavillon de Breteuil, 92312 Sevres, France, http://www.nucleide.org/DDEP.htm (2004).

- 4.Müller C, et al. Future prospects for SPECT imaging using the radiolanthanide terbium-155 – production and preclinical evaluation in tumour-bearing mice. J. Nucl. Med. 2014;41:e58–e65. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2013.11.002.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehenberger S, et al. The low-energy β- and electron emitter 161Tb as an alternative to 177Lu for targeted radionuclide therapy. J. Nucl. Med. 2010;38:917–924. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Formento Cavaier R, Haddad F, Sounalet T, Stora T, Zahi I, the MEDICIS-PROMED collaboration Terbium radionuclides for theranostics applications: A focus on MEDICIS-PROMED. Phys. Procedia. 2017;90:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.phpro.2017.09.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.dos Santos Augusto RM, et al. CERN-MEDICIS(medical isotopes collected from ISOLDE): A new facility. Appl. Sci. 2014;4:265–281. doi: 10.3390/app4020265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen B.J., Goozee G., Sarkar S., Beyer G., Morel C., Byrne A.P. Production of terbium-152 by heavy ion reactions and proton induced spallation. Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 2001;54(1):53–58. doi: 10.1016/S0969-8043(00)00164-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steyn GF, et al. Cross sections of proton-induced reactions on 152Gd, 155Gd and 159Tb with emphasis on the production of selected Tb radionuclides. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B. 2014;319:128–140. doi: 10.1016/j.nimb.2013.11.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duchemin C, Guertin A, Haddad F, Michel N, Métivier V. Deuteron induced Tb-155 production, a theranostic isotope for SPECT imaging and auger therapy. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes. 2016;118:281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2016.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tárkányi F, et al. Activation cross-sections of deuteron induced reactions on natGd up to 50 MeV. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes. 2014;83:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kazakov Andrey G., Aliev Ramiz A., Bodrov Alexander Yu., Priselkova Anna B., Kalmykov Stepan N. Separation of radioisotopes of terbium from a europium target irradiated by 27 MeV α-particles. Radiochimica Acta. 2018;106(2):135–140. doi: 10.1515/ract-2017-2777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vermeulen C, et al. Cross sections of proton-induced reactions on natGd with special emphasis on the production possibilities of 152Tb and 155Tb. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B. 2012;275:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.nimb.2011.12.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zagryadskii VA, et al. Measurement of terbium isotope yield in irradiation of 151Eu targets by 3He nuclei. At. Energy. 2017;123:55–58. doi: 10.1007/s10512-017-0299-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szelecsényi F, Kovács Z, Nagatsu K, Zhang M-R, Suzuki K. Investigation of deuteron-induced reactions on natGd up to 30 MeV: possibility of production of medically relevant 155Tb and 161Tb. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2016;307:1877–1881. doi: 10.1007/s10967-015-4528-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moeller, T. Atomic structure and its consequences – the dawn of understanding in The chemistry of the lanthanides (eds Sisler, H. H. & Van der Werf, C. A.) 18–21 (1963).

- 17.Martin MJ. ENSDF: The evaluated nuclear structure data file. AIP Conf. Proc. 1986;146:10–13. doi: 10.1063/1.35876. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Toxicological review of cerium oxide and cerium compounds: In support of summary Information on the Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS), https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/iris/iris_documents/documents/toxreviews/1018tr.pdf (2009).

- 19.Rim KT, Koo KH, Park JS. Toxicological evaluations of rare earths and their health impacts to workers: a literature review. Saf. Health Work. 2013;4:12–26. doi: 10.5491/SHAW.2013.4.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cotton, S. A. Scandium, Yttrium & the Lanthanides: Inorganic & Coordination Chemistry in Encyclopaedia of Inorganic Chemistry (ed. King, R. B.) 1–40 (2006).

- 21.Cacheris WP, Nickle SK, Sherry AD. Thermodynamic study of lanthanide complexes of l,4,7-triazacyclononane-N,N′,N″-triacetic acid and 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-N,N′,N″,N′“-tetraacetic acid. Inorg. Chem. 1987;26:958–960. doi: 10.1021/ic00253a038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collins SM, et al. The potential radio-immunotherapeutic α-emitter 227Th – part II: Absolute γ-ray emission intensities from the excited levels of 223Ra. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2019;145:251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2018.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Currie LA. Limits for qualitative detection and quantitative determination. Application to radiochemistry. Anal. Chem. 1968;40:586–593. doi: 10.1021/ac60259a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horwitz EP, McAlister DR, Dietz ML. Extraction Chromatography Versus Solvent Extraction: How Similar are They? Sep. Sci. Technol. 2006;41:2163–218. doi: 10.1080/014963906007428492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Böhlen TT, et al. The FLUKA Code: Developments and Challenges for High Energy and Medical Applications Nuclear Data Sheets. 2014;120:211–214. doi: 10.1016/j.nds.2014.07.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferrari, A., Sala, P. R., Fasso, A. & Ranft, J. CERN-2005-10, INFN/TC_05/11, SLAC-R-773 (2005).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated and analysed during this study are available, upon reasonable request, from the corresponding author.