Abstract

Background

Cross-national comparison studies on gender differences have mainly focussed on life expectancy, while less research has examined differences in health across countries. We aimed to investigate gender differences in cognitive function and grip strength over age and time across European regions.

Methods

We performed a cross-sectional study including 51 292 men and 62 007 women aged 50 + participating in the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe between 2004–05 and 2015. Linear regression models were used to examine associations.

Results

In general, women had better cognitive function than men, whereas men had higher grip strength measures. Sex differences were consistent over time, but decreased with age. Compared with men, women had higher cognitive scores at ages 50–59, corresponding to 0.17 SD (95% CI 0.14, 0.20) but slightly lower scores at ages 80–89 (0.08 SD, 95% CI 0.14, 0.00). For grip strength, the sex difference decreased from 18.8 kg (95% CI 18.5, 19.1) at ages 50–59 to 8.5 kg (95% CI 7.1, 9.9) at age 90 + . Northern Europeans had higher cognitive scores (19.6%) and grip strength measures (13.8%) than Southern Europeans. Gender differences in grip strength were similar across regions, whereas for cognitive function they varied considerably, with Southern Europe having a male advantage from ages 60–89.

Conclusion

Our results illustrate that gender differences in health depend on the selected health dimension and the age group studied, and emphasize the importance of considering regional differences in research on cognitive gender differences.

Introduction

Cognitive gender differences have fascinated researchers for decades, and their magnitude, patterns and causes continue to create debate.1 Despite substantial increases in cognitive performance over time,2 cognitive gender differences are still reported. Males tend to outperform females on most measures of visuospatial abilities,3 while sex differences that favour females in verbal abilities, such as reading and writing, are well documented.4–6 However, there are indications that sex differences are currently changing—for some tasks they are decreasing, while increasing or remaining stable for other tasks—and that sex differences in cognitive abilities need further examination.7 A recent study that used data from the second wave of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) found that gender differences in cognitive function differed across cognitive tasks, birth cohorts and regions, with a geographical gradient, indicating a Northern advantage over Western and Southern regions.1

Interestingly, a similar North–South gradient has been found for other health measures, such as grip strength. Jeune et al.8 compared grip strength among 598 nonagenarians and centenarians in three European countries. The study found a clear North–South gradient, with lower mean grip strength in Italy compared to France and Denmark. Andersen-Ranberg et al.9 investigated cross-national differences in grip strength in the first wave of SHARE and found geographical differences, with the highest scores in Northern-continental European countries and the lowest in Southern countries. The two studies found that women had lower grip strength than men.8,9 Similarly, other cross-national comparison studies have shown that men are physically stronger8,10,11 and have higher grip strength measures than women.12–14 However, comparisons of grip strength across different populations have been impeded due to the use of different measurement tools and methods, and little is known about grip strength in the oldest population.15

This study sheds light on cognitive and physical health in a group that makes up an increasing proportion of European populations, namely, elderly people.16 Cognitive function and grip strength are strong predictors of mortality both in younger elderly and among the oldest old.17,18 This very large cross-sectional sample of 113 299 Europeans aged 50 + from all available waves of SHARE interviewed during 10 years offers the opportunity to detect gender differences in these two important public health measures over age and time across European regions. The SHARE sample represents a unique opportunity to examine gender differences in countries with cultural variety and differences in the health behaviours and social roles of men and women.19

Methods

Setting and study population

SHARE is a cross-national and longitudinal survey, collecting individual data about economic, health and social factors of Europeans aged 50 and above. The data collection in SHARE is done according to strict quality standards and with ex-ante harmonized interviews across countries.20 Data were drawn at the household level, and the personal interviews were performed in the participants’ homes by a well-trained team of interviewers.20 To increase sample size and compensate for attrition, refresher samples were added in each wave.20 The household response rate differed by country varying between 44.0 and 97.6% in wave 1 and between 30.3 and 69.3% for refreshers in wave 6.21

This study includes men and women aged 50+ from the 20 European countries available in SHARE. Data on demographic and health indicators were obtained from waves 1 (2004–05), 2 (2006–07), 4 (2011), 5 (2013) and 6 (2015). We excluded individuals with unknown birth date (n = 19) and missing cross-sectional individual weights (n = 385, 0.3%). The numbers of observations in each wave in the individual countries are presented in Supplementary table S1.

Background variables

Ages were grouped into 10-year categories for ages 50–89, with an open-ended category from age 90. The European countries were classified into four regions: Northern Europe (Denmark and Sweden), Western Europe (Austria, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Belgium, Ireland and Luxembourg), Southern Europe (Spain, Italy, Greece and Portugal) and Eastern Europe (Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, Slovenia, Estonia and Croatia). Educational level was assessed as self-reported highest educational attainment and recorded into low [International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) groups 0–2], medium (ISCED groups 3–4) and high (ISCED groups 5–6), according to the ISCED (ISCED 1997).22 Height and chronic diseases were self-reported. Chronic diseases were divided into a binary variable (<2, 2+ chronic diseases).

Health variables

All participants in SHARE were tested on three cognitive tasks that assessed fluency—checked by the number of animals that the respondent could name in one minute—and episodic memory. The latter included immediate recall, which measures how many of 10 words the respondent could recall immediately after the interviewer read the words, and delayed memory, which measures the ability to recall the same words after other interview questions. We calculated a cognitive composite score (CCS)23 by standardizing each of these tests to the mean and standard deviation (SD) of the youngest age group (50–54 year olds) in the total study population, before summing them into the CCS. Higher scores reflected better performance. To facilitate easy interpretation, the CCS was linearly transformed into a T-score with a mean of 50 and an SD of 10, in the youngest age group.24 If a person had missing information of one or more of the cognitive tests, the CCS was coded as missing and thus excluded from the analyses.

The method for measuring grip strength has previously been described.9 In short, grip strength was measured in kilograms and assessed as the maximum score out of four trials (two measurements per hand), recorded with a handheld dynamometer.

Statistical analyses

Using linear regression models with robust standard errors, we compared cognitive function and grip strength between men and women over the fives waves of SHARE, for all countries combined and for the four regions separately. The model took into account clustering due to repeated measurements of the same individual. All analyses included interactions between gender and age groups, adjusted for European region, and wave. We repeated the analyses, controlling for education, height and chronic diseases. In a sensitivity analysis, we repeated the analyses, excluding people with dementia (3927 observations, 1.6%). In all analyses, we included the cross-sectional individual probability weights supplied by SHARE.25 Stata version 14.2 was used for the analyses.

Results

In total, 51 292 men (45.3%) and 62 007 (54.7%) women were included, corresponding to 244 258 observations (Supplementary figure S1). The proportion of men and women differed slightly in the four European regions (table 1). Educational attainment was higher for men than for women in all regions, except Northern Europe. Southern Europe had the highest proportion of participants with low education. More women than men had at least two chronic conditions, with the largest share of chronic conditions in Eastern Europe, but the largest gender difference in Southern Europe (table 1). The means of the CCS were higher among women than among men in all regions except Southern Europe, where men had higher scores than women. The means of grip strength were higher among men than women in all regions, with the largest gender difference in Northern Europe (table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of men and women participating in SHARE between 2004–05 and 2015

| All countries | Northern Europea | Western Europeb | Southern Europec | Eastern Europed | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| N (%) individuals | 51 292 (45.3) | 62 007 (54.7) | 5716 (46.9) | 6464 (53.1) | 21 091 (45.7) | 25 021 (54.3) | 11 626 (45.8) | 13 746 (54.2) | 12 859 (43.4) | 16 776 (56.6) |

| N (%) observations | ||||||||||

| 50–59 years | 31 611 (29.0) | 41 405 (30.6) | 3787 (27.1) | 4734 (29.4) | 14 691 (31.5) | 18 652 (32.9) | 6338 (26.2) | 8657 (29.7) | 6795 (28.2) | 9362 (28.2) |

| 60–69 years | 38 757 (35.6) | 44 871 (33.2) | 5086 (36.4) | 5688 (35.3) | 16 357 (35.1) | 18 461 (32.5) | 8377 (34.6) | 9375 (32.1) | 8937 (37.1) | 11 347 (34.1) |

| 70–79 years | 26 893 (24.7) | 31 757 (23.5) | 3480 (24.9) | 3666 (22.7) | 10 935 (23.4) | 12 553 (22.1) | 6503 (26.8) | 7050 (24.2) | 5975 (24.8) | 8488 (25.5) |

| 80–89 years | 10 667 (9.8) | 15 156 (11.2) | 1457 (10.4) | 1750 (10.9) | 4250 (9.1) | 6166 (10.9) | 2697 (11.1) | 3536 (12.1) | 2263 (9.4) | 3704 (11.1) |

| 90 + years | 1057 (1.0) | 2084 (1.5) | 169 (1.21) | 282 (1.8) | 431 (0.9) | 904 (1.6) | 315 (1.3) | 550 (1.9) | 142 (0.6) | 348 (1.1) |

| Total | 108 985 | 135 273 | 13 979 | 16 120 | 46 664 | 56 736 | 24 245 | 29 295 | 24 112 | 33 249 |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 66.2 (9.7) | 66.3 (10.3) | 66.6 (9.8) | 66.4 (10.3) | 65.6 (9.8) | 65.9 (10.4) | 67.1 (9.9) | 66.8 (10.6) | 66.1 (9.3) | 66.7 (9.9) |

| Height, mean (SD) | 174.7 (7.4) | 162.8 (6.6) | 178.1 (6.8) | 165.0 (6.2) | 175.3 (7.2) | 163.2 (6.6) | 171.0 (7.0) | 160.4 (6.4) | 175.1 (6.9) | 162.9 (6.3) |

| Missing | 911 (0.8) | 1418 (1.1) | 54 (0.4) | 81 (0.5) | 288 (0.6) | 464 (0.8) | 409 (1.7) | 633 (2.2) | 160 (0.7) | 240 (0.7) |

| Education, %e | ||||||||||

| Low | 41 845 (39.1) | 63 020 (47.3) | 4164 (30.4) | 5374 (33.9) | 12 976 (28.3) | 22 769 (40.8) | 16 560 (69.7) | 21 751 (76.1) | 8145 (34.2) | 13 126 (39.9) |

| Medium | 40 478 (37.8) | 45 574 (34.2) | 5238 (38.2) | 4994 (31.5) | 19 500 (42.5) | 21 280 (38.2) | 4309 (18.1) | 4453 (15.6) | 11 431 (848.0) | 14 847 (45.1) |

| High | 24 829 (23.2) | 24 558 (18.4) | 4304 (31.4) | 5500 (34.7) | 13 376 (29.2) | 11 734 (21.0) | 2890 (12.2) | 2376 (8.3) | 4259 (17.9) | 4948 (15.0) |

| Missing | 1833 (1.7) | 2121 (1.6) | 273 (2.0) | 252 (1.6) | 812 (1.7) | 953 (1.7) | 471 (1.9) | 588 (2.0) | 277 (1.2) | 328 (1.0) |

| Chronic diseases, %e | ||||||||||

| <2 diseases | 60 066 (55.3) | 67 711 (50.2) | 8080 (57.9) | 8750 (54.4) | 26 588 (57.3) | 30 624 (54.2) | 13 487 (55.8) | 13 732 (47.2) | 11 911 (49.6) | 14 605 (44.1) |

| 2 + chronic diseases | 48 485 (44.7) | 67 068 (49.8) | 5870 (42.1) | 7340 (45.6) | 19 833 (42.7) | 25 850 (45.8) | 10 675 (44.2) | 15 348 (52.8) | 12 107 (50.4) | 18 530 (55.9) |

| Missing | 434 (0.4) | 494 (0.4) | 29 (0.2) | 30 (0.2) | 243 (0.5) | 262 (0.5) | 68 (0.3) | 88 (0.3) | 94 (0.4) | 114 (0.3) |

aDenmark and Sweden.

bAustria, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Belgium, Ireland and Luxembourg.

cSpain, Italy, Greece and Portugal.

dCzech Republic, Poland, Hungary, Slovenia, Estonia and Croatia.

eMissing data are excluded from percentage calculations.

Table 2.

Cognitive function and grip strength for men and women participating in SHARE between 2004–05 and 2015

| All countries | Northern Europea | Western Europeb | Southern Europec | Eastern Europed | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Cognitive composite score | ||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 45.0 (10.6) | 46.1 (11.5) | 48.0 (10.0) | 50.7 (10.6) | 46.6 (10.3) | 48.1 (11.0) | 40.1 (9.6) | 39.3 (10.1) | 45.1 (10.7) | 46.3 (11.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 45.2 (38.0–52.2) | 46.5 (38.4–54.1) | 48.4 (41.8–54.7) | 51.4 (44.3–57.8) | 46.9 (40.0–53.5) | 48.7 (41.0–55.6) | 40.2 (33.5–46.4) | 39.3 (32.4–46.0) | 45.2 (38.0–52.2) | 46.6 (38.6–54.0) |

| Missing data, % | 4.6 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 3.8 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 3.6 |

| Subcomponents of the cognitive composite score | ||||||||||

| Fluency, mean (SD) | 20.0 (7.5) | 19.7 (7.8) | 23.1 (7.3) | 23.3 (7.3) | 20.8 (7.2) | 20.7 (7.3) | 15.5 (6.4) | 14.5 (6.4) | 20.8 (7.6) | 20.9 (7.8) |

| Immediate recall | 5.0 (1.8) | 5.2 (1.9) | 5.2 (1.7) | 5.7 (1.8) | 5.2 (1.8) | 5.5 (1.8) | 4.5 (1.8) | 4.4 (1.9) | 5.0 (1.8) | 5.3 (1.8) |

| Delayed recall | 3.6 (2.1) | 3.9 (2.2) | 4.0 (1.9) | 4.6 (2.1) | 3.9 (2.1) | 4.3 (2.2) | 3.0 (1.9) | 3.0 (2.0) | 3.4 (2.1) | 3.7 (2.2) |

| Grip strength | ||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 42.9 (10.3) | 26.3 (7.1) | 45.4 (9.9) | 27.3 (6.7) | 43.9 (9.9) | 26.9 (6.9) | 39.1 (10.3) | 24.0 (7.1) | 43.4 (10.3) | 26.8 (7.2) |

| Median (IQR) | 43 (36–50) | 26 (22–31) | 46 (39–52) | 28 (23–32) | 44 (38–50) | 27 (23–31) | 40 (32–46) | 24 (20–29) | 44 (37–50) | 27 (22–31) |

| Missing data, % | 7.8 | 9.7 | 3.2 | 5.4 | 6.5 | 8.8 | 10.8 | 14.0 | 10.1 | 9.6 |

aDenmark and Sweden.

bAustria, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Belgium, Ireland and Luxembourg.

cSpain, Italy, Greece and Portugal.

dCzech Republic, Poland, Hungary, Slovenia, Estonia and Croatia.

Distributions for the CCS showed a decline in cognitive function over age, with women in Northern Europe having the highest CCS and women in Southern Europe having the lowest (figure 1A). The CCS was 16.4% lower for men and 22.4% lower for women in Southern than in Northern Europe. Similarly, the CCS was lower in Eastern (men 8.9%, women 12.9%) and Western Europe (men 3.0%, women 5.2%) than in Northern Europe. When investigating gender differences in cognitive function for all countries combined (figure 1B), we found a slight female advantage from ages 50–69 corresponding to 0.1–0.2 SD, no difference from age 70–79 and a small male advantage of 0.08 SD from age 80–89. A fluctuating pattern was found from age 90, indicating slightly better cognitive function for men than women. Relatively, we found a female advantage of 3.9% for ages 50–59 decreasing to a male advantage of 2.8% for people aged 90 + . When investigating cognitive gender differences for the four regions separately, we found a female advantage in Northern Europe from ages 50–79 of 0.2–0.3 SD. A female advantage was also indicated for age 80–89 from 2006–07 to 2015 (figure 1C). For Western Europe, we found a female advantage from ages 50–79 and an indication of a male advantage thereafter (figure 1D). For Southern Europe, a male advantage was found from ages 60–89 with no gender differences for the youngest and oldest age groups (figure 1E). For Eastern Europe, a female advantage was found in the youngest age groups (50–69), with an indication of a male advantage thereafter, significant for ages 80–89 (figure 1F). Overall, we found a stable pattern of gender differences over time; however, fluctuating patterns were found for people aged 90 + (figure 1; Supplementary table S2).

Figure 1.

(A) Cognitive function over age groups for men and women in four European regions. (B–F) Gender differences in cognitive function for 20 European countries combined (B) and for the four European regions separately (C–F) over age groups and time in SHARE waves 1 (2004–05), 2 (2006–07), 4 (2011), 5 (2013) and 6 (2015)

In investigating the three cognitive tests separately, we found a slight male advantage for fluency from age 60 and above. For episodic memory, a slight female advantage was found from ages 50–79 with a tendency towards a male advantage thereafter (Supplementary figure S2).

When we excluded people who reported dementia, gender differences were identical to our primary analyses, overall, although cognitive function for people aged 90 + showed a slightly smaller male advantage (results not shown). Further analysis, adjusted for education, height and chronic diseases, showed an overall female advantage in cognitive function, present from ages 50–89 in Northern, Western and Eastern Europe. In Southern Europe, a female advantage was found from ages 50–69 with no gender differences thereafter (Supplementary table S2).

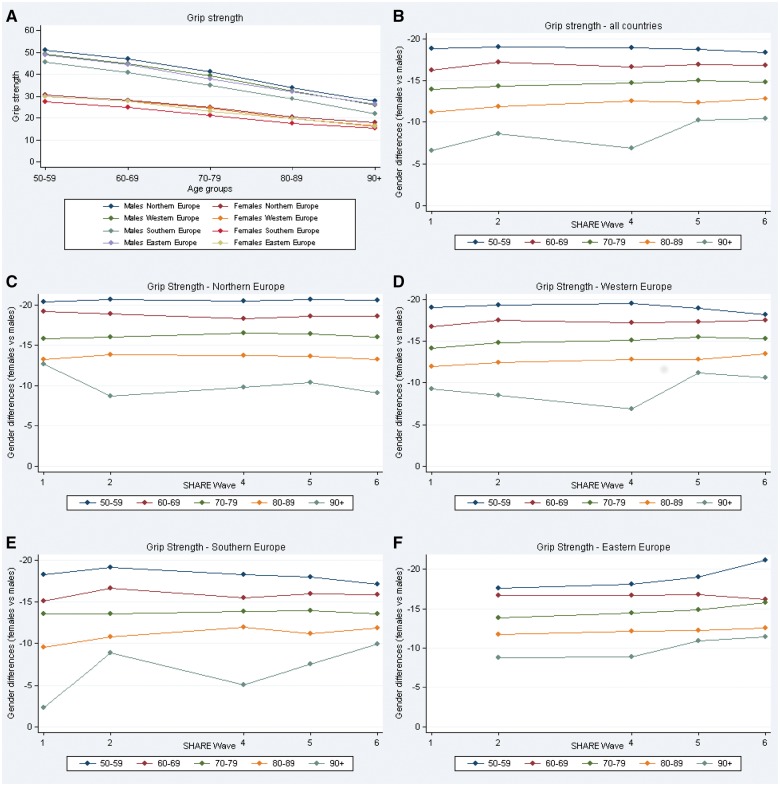

For grip strength, we found a North–South gradient with grip strength being 13.8% lower for men and 12.8% lower for women in Northern than in Southern Europe. Similarly, grip strength was also lower in Eastern (men 5.2%, women 3.8%) and Western Europe (men 3.1%, women 1.8%) than in Northern Europe. However, the age-trajectory of grip strength was similar in all European regions with a decline in grip strength with advancing age (figure 2A). Relatively, the male advantage decreased from 39.2% at ages 50–59 to 34.9% at age 90 + . When investigating gender differences, the results showed higher grip strength among men than women in all age groups, but the male advantage decreased from 18.8 kg (95% CI 18.5, 19.1) at ages 50–59 to 8.5 kg (95% CI 7.1, 9.9) at age 90 + (figure 2B). The patterns of gender differences were almost identical in the four European regions, but with a slightly larger female advantage in Northern Europe than in the other European regions (figure 2C–F). Gender differences were stable over time, except for slightly fluctuating patterns for people aged 90 + (figure 2; Supplementary table S3). In further adjusting for education, height and chronic diseases, the magnitude of the male advantage decreased in all European regions to a difference of 15.2 kg (95% CI 14.9, 15.5) at ages 50–59 and 5.2 kg (95% CI 3.8, 6.7) for age 90 + (Supplementary table S3).

Figure 2.

(A) Grip strength over age groups for men and women in four European regions. (B–F) Gender differences in grip strength for 20 European countries combined (B) and for the four regions separately (C–F) over age groups and time in SHARE waves 1 (2004–05), 2 (2006–07), 4 (2011), 5 (2013) and 6 (2015)

Discussion

Our results illustrate female cognitive and male physical superiority with stable gender differences over time, but with decreasing differences with advancing age on both the absolute and relative scale. Thus, despite men being stronger than women, the gender gap in grip strength diminished with increasing age in all European regions, which may imply that women maintain their grip strength better over age. For cognitive function, the female advantage decreased with advancing age, but the pattern of gender differences varied considerably by region. Women had better cognitive function than men in most age groups in Northern Europe, but worse cognitive function in Southern Europe. The regional differences in cognitive function might—at least partly—be explained by differences in education. Overall, cognitive function and grip strength varied between European regions, with higher cognitive scores (19.6%) and grip strength measures (13.8%) in Northern than in Southern Europe.

Few comparative studies have examined objective measures of performance,12 but, similar to previous studies,8,14,26 we observed a substantial male advantage in grip strength across countries. Despite men having higher grip strength than women, also at the oldest ages,10,15 we found that the gender gap diminished with increasing age, as previously demonstrated in Denmark and in the USA.14 Also, in line with our results, a population-based study of Danes aged 45 and above found that grip strength declined throughout life for both sexes, but for the oldest women, the curve reaches a horizontal plateau.10 These findings may imply that despite men being stronger than women at all ages, women may be better at maintaining their grip strength measures over age. In contrast, we found a decreasing female advantage with advancing age for cognitive function. This was in line with data from Denmark showing higher cognitive scores for men than women aged 80 and older,14 which may be due to small numbers and selectivity of very old participants. In line with a longitudinal study,27 we found that gender differences were stable over time, apart from a slightly fluctuating pattern among individuals aged 90 + . However, gender differences in this study depended on tests being consistent with research that reported an average female advantage for episodic recall,14,28 and with small or no overall differences in fluency.29,30

In agreement with comparative studies from Europe,1,8,9,31 we found a North–South gradient in grip strength and cognitive function demonstrating a Northern advantage over Southern regions. The North–South gradient in grip strength may be due to population background differences, such as birth weight, childhood growth and genetic variations and sociocultural differences, for instance, lifestyle and health care.8 However, although we confirmed the North–South gradient in grip strength, we found overall similar patterns of gender differences across European regions. Regarding cognitive function, Weber et al.1 demonstrated that the magnitude of gender differences varies systematically across regions, with both men and women in less advantaged regions (with high levels of mortality, large family sizes and low educational levels) having worse cognitive performance than respondents in more advantaged regions, and that women tend to have worse cognitive performance than men.1 Considering all available waves in SHARE, this study confirmed the geographic gradient in cognitive function with contrasting directions of gender differences in cognition between Northern and Southern Europe.

Previous literature has reported that some of the gender gap in various cognitive measures is explained by differences in education.1,13,32 In this study, we found that a slightly higher proportion of women than men in Northern Europe had high education, which may partially explain the fact that the gender difference in cognition was greatest in this region. Our results suggested that education, height and the number of chronic diseases contribute substantially to the gender gap in cognitive function. When these factors were controlled for, gender differences in Northern, Western and Eastern Europe were quite similar, with a female advantage in all age groups, whereas we found the smallest female advantage in Southern Europe. Based on these and previous research findings,1 and the fact that cognitive function is a strong predictor of both health and survival,33,34 policy makers should direct resources to ensure equal educational opportunities for men and women. If educational opportunities and living conditions improve in Southern Europe, women in these countries may improve their cognitive abilities, and thus in the future gender differences in Southern Europe may be more similar to those in higher-income countries.

This study has several strengths. Notably, we have very large sample sizes and, thus, high power to detect gender-specific patterns in health across European regions and make use of multiple waves of data. This allows for investigations of gender differences over age groups and time, including not only middle-aged Europeans but also elderly and very old people, for whom data are sparser.33,35 Further, this study examined gender differences with performance-based measures on cognitive functioning and grip strength, thus avoiding biases that may arise in self-reports.

A limitation in this study is that the cognitive function is a composite of three measures, and thus it is not likely to reflect all aspects of the cognitive ability. Particularly, we did not include tasks on which men traditionally have an advantage, such as numeracy.1 Another limitation in SHARE is the low response rate, which could lead to sample selection bias. However, SHARE provides calibrated weights, which are constructed to reduce the impact of this issue.20 The proportion of missing data differed between items and regions, with a slightly higher proportion of missing values of cognitive function for men than women (4.6 vs. 3.7%). For grip strength, fewer missing values were found for men than women (7.8 vs. 9.7%). Further, we grouped the 20 countries into four regions based on geographical proximity; thus, we did not detect potential varying gender differences between countries within the specific regions. A general limitation of SHARE is a large number of participants with unknown vital status, and SHARE has not (so far) systematically validated the mortality data by linking the sample to official registers. Thus, although it would have been interesting to investigate the longitudinal trajectories of cognitive functioning for males and females, these analyses would be problematic due to missing information on the follow-up of participants—primarily, a lack of information on mortality. However, we contribute to the research field by making (to our knowledge) the largest cross-sectional study of cognitive function and grip strength to take into account variations over age, time and European regions.

In conclusion, our results illustrate female cognitive and male physical superiority. For both measures, gender differences were stable over time but decreased with age. Gender differences in grip strength were similar across regions, whereas gender differences in cognitive function varied considerably, with women in Southern Europe having worse cognitive function than men at most ages. Our results may imply that despite men having higher grip strength measures than women, women may be better at maintaining their grip strength over age. Furthermore, we show that both men and women do cognitively worse in Southern Europe, the region with the lowest educational levels. Given that cognitive function is a strong predictor of both health and survival, policy makers should direct resources to ensure equal educational opportunities for men and women in all European regions.

Funding

This paper uses data from SHARE Waves 1, 2, 4, 5 and 6 (DOIs: 10.6103/SHARE.w1.600, 10.6103/SHARE.w2.600, 10.6103/SHARE.w4.600, 10.6103/SHARE.w5.600, 10.6103/SHARE.w6.600), see Börsch-Supan et al. (2013) for methodological details.20 The SHARE data collection has been primarily funded by the European Commission through FP5 (QLK6-CT-2001‐00360), FP6 (SHARE-I3: RII-CT-2006‐062193, COMPARE: CIT5-CT-2005‐028857, SHARELIFE: CIT4-CT-2006‐028812) and FP7 (SHARE-PREP: N°211909, SHARE-LEAP: N°227822, SHARE M4: N°261982). Additional funding from the German Ministry of Education and Research, the Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science, the U.S. National Institute on Aging (U01_AG09740‐13S2, P01_AG005842, P01_AG08291, P30_AG12815, R21_AG025169, Y1-AG-4553‐01, IAG_BSR06‐11, OGHA_04‐064, HHSN271201300071C) and from various national funding sources is gratefully acknowledged (see www.share-project.org).

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Key points

In a large cross-sectional study including 113 299 participants from 20 European countries in SHARE, we investigated gender differences in cognitive function and grip strength over age groups and time across European regions.

In general, women had better cognitive function than men, whereas men had higher grip strength measures than women. For both measures sex differences decreased with age, but were consistent over time.

We found a geographic gradient in cognitive function, with Northern Europeans having higher cognitive scores (19.6%) and grip strength measures (13.8%) than Southern Europeans.

Gender differences in grip strength were similar across regions, whereas for cognitive function they varied considerably, with the largest gender difference in Southern Europe.

Our results suggest that women have a lower starting point but may be better at maintaining their grip strength over age than men.

If lower education is the reason behind the lower cognitive function of especially women in Southern Europe, this inequality can be reduced if policy makers direct resources to ensure equal educational opportunities for men and women.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Weber D, Skirbekk V, Freund I, Herlitz A. The changing face of cognitive gender differences in Europe. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:11673–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Flynn JR. Searching for justice: the discovery of IQ gains over time. Am Psychol 1999;54:5–20. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Voyer D, Voyer S, Bryden MP. Magnitude of sex differences in spatial abilities: a meta-analysis and consideration of critical variables. Psychol Bull 1995; 117:250–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Halpern DF, Benbow CP, Geary DC et al. The science of sex differences in Science and Mathematics. Psychol Sci Public Interest 2007;8:1–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hedges LV, Nowell A. Sex differences in mental test scores, variability, and numbers of high-scoring individuals. Science 1995;269:41–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ahrenfeldt L, Petersen I, Johnson W, Christensen K. Academic performance of opposite-sex and same-sex twins in adolescence: a Danish national cohort study. Horm Behav 2015;69:123–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miller DI, Halpern DF. The new science of cognitive sex differences. Trends Cogn Sci 2014;18:37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jeune B, Skytthe A, Cournil A et al. Handgrip strength among nonagenarians and centenarians in three European regions. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2006;61:707–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Andersen-Ranberg K, Petersen I, Frederiksen H et al. Cross-national differences in grip strength among 50 + year-old Europeans: results from the SHARE study. Eur J Ageing 2009;6:227–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Frederiksen H, Hjelmborg J, Mortensen J et al. Age trajectories of grip strength: cross-sectional and longitudinal data among 8, 342 Danes aged 46 to 102. Ann Epidemiol 2006;16:554–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Proctor DN, Fauth EB, Hoffman L et al. Longitudinal changes in physical functional performance among the oldest old: insight from a study of Swedish twins. Aging Clin Exp Res 2006;18:517–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wheaton FV, Crimmins EM. Female disability disadvantage: a global perspective on sex differences in physical function and disability. Ageing Soc 2016;36:1136–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oksuzyan A, Singh PK, Christensen K, Jasilionis D. A cross-national study of the gender gap in health among older adults in India and China: similarities and disparities. Gerontologist 2018;58:1156–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Oksuzyan A, Crimmins E, Saito Y et al. Cross-national comparison of sex differences in health and mortality in Denmark, Japan and the US. EurJ Epidemiol 2010;25:471–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Oksuzyan A, Maier H, McGue M et al. Sex differences in the level and rate of change of physical function and grip strength in the Danish 1905-cohort study. J Aging Health 2010;22:589–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Commission E. Demography report 2010. Older, more numerous and diverse Europeans. 2011. Available at: ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet? docId = 6824&langId = en (24 January 2018, date last accessed).

- 17. Nybo H, Petersen HC, Gaist D et al. Predictors of mortality in 2, 249 nonagenarians–the Danish 1905-Cohort Survey. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51: 1365–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sayer AA, Kirkwood TB. Grip strength and mortality: a biomarker of ageing? Lancet 2015;386:226–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Crimmins EM, Kim JK, Sole AA. Gender differences in health: results from SHARE, ELSA and HRS. Eur J Public Health 2011;21:81–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Borsch-Supan A, Brandt M, Hunkler C et al. Data resource profile: the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:992–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bergmann M, Kneip T, Luca GD, Scherpenzeel A. Ageing and Retirement (SHARE), wave 1‐6. Based on Release 6.0.0 (March 2017). SHARE Working Paper Series 31‐2017. Munich: SHARE-ERIC, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.UNESCO.International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 23. McGue M, Christensen K. The heritability of cognitive functioning in very old adults: evidence from Danish twins aged 75 years and older. Psychol Aging 2001;16:272–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hale CD, Astolfi D. Standardized Testing: Introduction. Measuring Learning & Performance: A Primer. St. Leo, FL: Saint Leo University, 2011: 183–97. Available at:http://www.charlesdennishale.com/. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Börsch-Supan A, Jürges H. The Survey of Health, aging, and Retirement in Europe - Methodology. Mannheim: MEA, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kuh D, Bassey EJ, Butterworth S et al. Grip strength, postural control, and functional leg power in a representative cohort of British men and women: associations with physical activity, health status, and socioeconomic conditions. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2005;60:224–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. de Fria CM, Nilsson LG, Herlitz A. Sex differences in cognition are stable over a 10-year period in adulthood and old age. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn 2006;13:574–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Herlitz A, Airaksinen E, Nordstrom E. Sex differences in episodic memory: the impact of verbal and visuospatial ability. Neuropsychology 1999;13:590–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Crossley M, D’Arcy C, Rawson NS. Letter and category fluency in community-dwelling Canadian seniors: a comparison of normal participants to those with dementia of the Alzheimer or vascular type. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1997;19:52–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Capitani E, Laiacona M, Basso A. Phonetically cued word-fluency, gender differences and aging: a reappraisal. Cortex 1998;34:779–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ahrenfeldt LJ, Lindahl-Jacobsen R, Rizzi S et al. Comparison of cognitive and physical functioning of Europeans in 2004–05 and 2013. Int J Epidemiol 2018;47:1518–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schneeweis N, Skirbekk V, Winter-Ebmer R. Does education improve cognitive performance four decades after school completion? Demography 2014;51:619–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Christensen K, Thinggaard M, Oksuzyan A et al. Physical and cognitive functioning of people older than 90 years: a comparison of two Danish cohorts born 10 years apart. Lancet 2013;382:1507–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thinggaard M, McGue M, Jeune B et al. Survival prognosis in very old adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:81–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Crimmins EM, Beltrán-Sánchez H. Mortality and morbidity trends: is there compression of morbidity? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2011;66:75–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.