Abstract

The age at first marriage in the U.S. has consistently increased, while the age at cohabitation has stalled. These trends present an opportunity for serial cohabitation (multiple cohabiting unions). The authors argue that serial cohabitation must be measured among those at risk, who have ended their first cohabiting union. Drawing on data from the National Survey of Family Growth Cycle 6 (2002), and continuous 2006–2013 interview cycles, the authors find that serial cohabitation is increasing among women at risk. Millennials, born 1980–1984, had 50% higher rates of cohabiting twice or more after dissolving their first cohabitation. This increase, however, is not driven by the composition of Millennials at risk for serial cohabitation. This work demonstrates the importance of clearly defining who is at risk for serial cohabitation when reporting estimates, as well as continuing to examine how the associations between sociodemographic characteristics and serial cohabitation may shift over time.

Keywords: Cohabitation, cohort, coresidence, life course, social trends/social change

For young adults forming relationships in the United States, cohabitation has usurped marriage. A majority of young adult women interviewed in the past decade have cohabited (73%), whereas half has married (Lamidi and Manning, 2016). In most industrialized nations, young adult women’s first union is overwhelmingly a cohabiting union, rather than a marriage, and women are marrying later than ever (Anderson and Payne, 2016; Manning, Brown, and Payne, 2014; Hiekel, Liefbroer, and Poortman, 2014). Despite the fixed role of cohabitation in young adult romantic relationships in both the United States and Europe, however, cohabiting unions in the U.S. are more likely to dissolve than result in marriage (Guzzo, 2014; Lamidi, Manning, and Brown, 2015). Young adults, then, may have more opportunities to experience a second or third cohabiting union (serial cohabitation) in the context of delayed marriage and the increased risk of cohabitation dissolution. Recent research suggests that serial cohabitation has increased for young adults in Western Europe and the United States, although there are few recent papers on serial cohabitation in the U.S. (Bukodi, 2012; Dommermuth and Wiik, 2014; see Lichter, Turner, and Sassler, 2010; Cohen and Manning, 2010; Vespa, 2014 for U.S. research).

This previous U.S. research, however, may lead to skewed estimates of serial cohabitation, as previous analytic populations include women who are not technically at risk for serial cohabitation. Serial cohabitation has been measured among all women, never-married women, or prior to women’s first marriage (see Lichter et al., 2010; Cohen and Manning, 2010). Recent studies have measured serial cohabitation among women who had ever cohabited (Vespa, 2014). Without having a first cohabiting union and dissolving this relationship, however, women cannot go on to have a second cohabiting union—much like remarriage, which is measured among those who have ended their first marriage. Therefore, we propose a more nuanced measurement of serial cohabitation among women who have dissolved their first cohabiting union. These initial approaches served to define serial cohabitation in the field of family sociology and demography, but these primary estimates may be conservative and may not wholly illuminate who is at risk for serial cohabitation. Further, the characteristics associated with serial cohabitation may be confounded with dissolution. Measuring serial cohabitation among women “at risk” for the event (i.e., who have dissolved their first cohabiting union), may be beneficial to clarify the risk factors of serial cohabitation, and to compare these factors over time. Young adult women’s relationships have transitioned to include more cohabitation and serial cohabitation over the past three decades. Drawing on the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) Cycle 6 (2002), 2006–2010, and 2011–2013, in this study we provide an update to prior studies on serial cohabitation by considering an alternative analytic population “at risk” for serial cohabitation during young adulthood (ages 16–28). We frame our research questions within the diffusion perspective (Liefbroer and Dourleijn, 2006). First, have the shares of women serially cohabiting increased across birth cohort, from Baby Boomers (born 1960–1964) to Generation X (born (1965–1968, 1970–1974, 1975–1979) and Millennials (born 1980–1984)? Second, is the likelihood of serially cohabiting during young adulthood, compared to cohabiting once, higher for more recent cohorts of young women born after 1964, Millennials or Generation X, compared to Baby Boomers born between 1960 and 1964, and does this cohort divide exist net of sociodemographic indicators? Third, do the traditional predictors of serial cohabitation persist in the youngest birth cohort of women compared to the earliest birth cohort? Finally, does the cohort divide remain after we standardize the characteristics of the earliest and latest cohorts to one another?

Our paper provides a snapshot of union experiences for women ages 16–28 born during the early 1960s (late Baby Boom cohort) and through the early 1980s (Millennial cohort). Theoretically, examining different generations is fruitful for comparing union experiences, as it allows for the comparison of cultural shifts over time to be situated within a framework of distinct birth cohorts characterized by their own rituals, narratives, and historical experiences (Eyerman and Turner, 1998). Applying the diffusion perspective, we would expect that the sociodemographic characteristics of serial cohabitors have shifted, narrowing the sociodemographic divide between who has serially cohabited and who has cohabited once. Our approach provides a new lens on the changes in cohabitation and marriage in the United States during young adulthood by examining the serial cohabitation experiences of women who have dissolved their first cohabiting union—those young adult women who are at risk for cohabiting more than once.

BACKGROUND

Trends in Cohabitation in the United States

The relationship context of young adult women in the U.S. has shifted greatly over the past three decades to one typified by cohabitation and delayed marriage. Nearly thirty years ago, 41% of young adult women ages 25–29 had ever cohabited (Bumpass and Lu, 2000). By 2013, nearly three-quarters had cohabitation experience (Lamidi and Manning, 2016; Manning and Stykes, 2015). As cohabitation has become more characteristic of this life stage, the age at first marriage has continued to rise and approaches age 30 (Anderson and Payne, 2016). Meanwhile, the age at which women begin cohabiting has not changed; the median age at first cohabitation has remained at about age 22 over a thirty-year period (Manning et al. 2014). Consequently, there is now more time during early adulthood for many young adult women to experience serial cohabitation.

In addition, the weakening link between cohabitation and marriage creates a relationship context that allows more opportunities for serial cohabitation. There is a marked instability that characterizes cohabiting unions in the U.S. Although a nontrivial share of cohabitors enter their union with plans to marry their partner or enter cohabiting unions to test compatibility, the reality is that most cohabiting unions in the United States end in dissolution rather than transitioning to marriage or remaining intact (Guzzo, 2014; Lamidi et al., 2015; Sassler, 2004). Only one-third of recent cohabitation cohorts transition to marriage by five years compared to over half (57%) in the 1980s, and though the share of cohabitors remaining together has distinctly increased from 6% to 22%, this is not the normative experience (Lamidi et al., 2015). Cohabiting unions are brief: the average duration of cohabiting unions is just over two years (Copen, Daniels, and Mosher, 2012; Lamidi et al., 2015). Sharing a residence may represent an opportunity for young adults to test whether they would like to marry their partner (Huang, Smock, Manning, and Bergstrom-Lynch, 2011), yet the short duration of these unions may illustrate that partnering is common during this life stage, but not akin to “settling down” (Arnett, 2000). Taken together, the early age at first cohabitation, high risk of separation and shrinking proportion of cohabiting unions transitioning to marriage, and short duration of most cohabiting unions, provides an unparalleled opportunity to serially cohabit during young adulthood.

Serial Cohabitation in the United States

Most of the research on serial cohabitation in the U.S. has focused on documenting the sociodemographic patterns of serial cohabitation among never married women or women who have ever cohabited (Cohen and Manning, 2010; Lichter et al., 2010; Vespa, 2014). Nationally representative data shows that, over time, women who have ever cohabited are becoming more likely to serially cohabit. Bumpass and Lu (2000) estimated that about 7% of cohabitors had lived with more than one partner in the 1980s. Yet by 2002, one quarter of cohabitors (25%) had serially cohabited (Lichter et al. 2010) and by 2010, this estimate was over one third (35%) (Vespa, 2014). The number of women experiencing serial cohabitation is increasing faster than those experiencing only one-time cohabitation, and serial cohabitation has increased by 80% between the 1980s and 2010s (Cohen and Manning, 2010; Vespa, 2014). This trend implies that serial cohabitation is becoming an established relationship trajectory, potentially as a new form of “intensive dating” among young adults (Lichter et al., 2010).

Despite the increases in serial cohabitation among cohabiting women overall, there appears to be a demographic divide in terms of who serially cohabits and who does not. Evidence indicates that serial cohabitors are among the most socioeconomically disadvantaged of cohabitors (Vespa, 2014; Lichter et al., 2010). Serial cohabitors are more likely to be raised in single-mother families, experience early sexual activity, have lower educational attainment, and experience a birth in their teens than their counterparts who cohabited with one partner (Cohen and Manning, 2010; Lichter et al., 2010). In addition, the majority of serial cohabitors are forming stepfamilies with the entrance into their second cohabiting union as they or their partners contribute children from prior relationships (Guzzo, 2017).

Diffusion

With the emergence of cohabitation as a minority experience, those who cohabited constituted a select group of individuals who differed from those who chose instead to directly marry (Liefbroer and Dourleijn, 2006). The theoretical underpinnings take the form of either a diffusion of norms or a diffusion of innovation. As cohabitation becomes more prevalent, norms shift and the selectivity of cohabitation wanes (Liefbroer and Dourleijn, 2006). Evidence is consistent examining attitudinal reports over time: between 1976 to 2008, the proportion of adolescents who agreed that premarital cohabitation was a good testing ground for marriage increased by 75%, and using data collected from 2011–2013, 64% of men and women agreed that living together before marriage could help to prevent divorce (Bogle and Wu, 2010; Eickmeyer, 2015). The shifting of attitudes represents an increased acceptance of cohabitation that provides social support for cohabitors and reduces the stigma of the union. Empirical support for this perspective has also been established with regard to cohabitation and marital dissolution. As cohabitation became more common it was no longer associated with an increased risk of marital dissolution (Manning and Cohen 2012; Liefbroer and Dourleijn 2006). As we pivot the application of the diffusion perspective to serial cohabitation, we expect that as cohabitation has become more common, the characteristics of serial cohabitors will be less select and they will resemble young adult women who cohabit once.

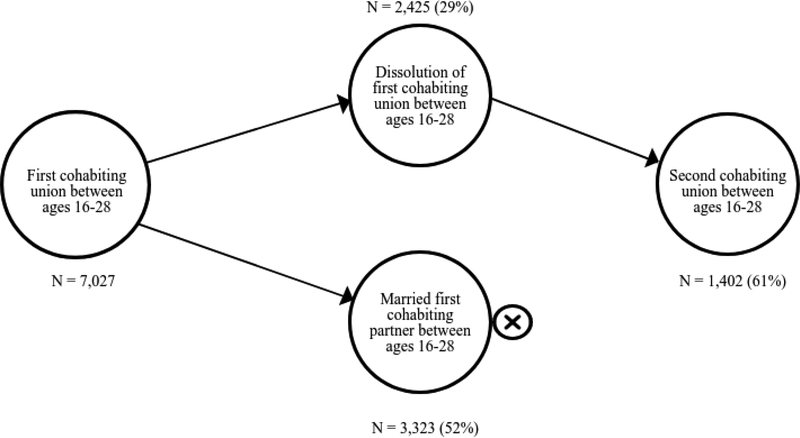

We used remarriage research as a guide for establishing a new approach to study serial cohabitation by focusing on defining the population at risk. In studying remarriage, scholars examine those individuals who have ended a marriage and as such are exposed to or at risk of re-partnering (e.g., McNamee and Raley 2011; Teachman and Heckert 1985). Although prior research examining serial cohabitation among women who have ever cohabited has merits, it is limited by considering serial cohabitation among all cohabitors rather than individuals at risk of serial cohabitation: those who have dissolved their relationship with their first cohabiting partner, Figure 1 illustrates these pathways and indicates when women become at risk for serial cohabitation.

Figure 1.

Pathway Into Premarital Serial Cohabitation During Young Adulthood (Ages 16–28).

Serial cohabitation is associated with a host of characteristics that we included to reduce the potential effects of selection. We included women’s race and ethnicity, as non-White and Hispanic women have significantly lower odds of serial cohabitation than White women, after controlling for demographic and economic factors (Cohen and Manning, 2010; Lichter et al., 2010). We accounted for education and family structure in childhood as women without a college degree and women whose parents separated have higher odds of serial cohabitation (Lichter et. al., 2010). We measured the respondent’s sexual partnership history to account for the association between serial cohabitation and women’s number of sex partners (Cohen and Manning, 2010). We controlled for the respondent’s childbearing history prior to dissolving their first cohabitation and entering a second cohabitation, as research indicates that women who have children before cohabiting have an increased risk of relationship dissolution, and relationships with stepchildren are less stable than those with only biological children (Lamidi et al., 2015; White and Booth, 1985). To account for the duration of and age at first cohabitation, we included an indicator of the respondent’s age at first union dissolution.

DATA and METHODS

We relied on the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) interviews conducted in Cycle 6 (2002), and interviews conducted between 2006–2010 and 2011–2013 as a part of the continuous survey. The NSFG is a series of nationally representative cross-sectional data that provides detailed information on family formation behaviors such as fertility, marriage, divorce, and cohabitation in the United States. Cohabitation episodes can be ascertained through retrospective reports on start and end dates of non-marital cohabitations, pre-marital cohabitations, and the respondent’s current cohabiting relationship. Interviews were conducted with the civilian non-institutionalized population, and included an oversampling of Blacks, Hispanics, and teenagers. Respondents were between ages 15–44 when they were interviewed. The response rate for Cycle 6 was 79%, for interviews conducted between 2006–2010 it was 77%, and for interviews conducted between 2011–2013 it was 72.8% (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2015, 2016).

Although each of these cycles included interviews with men and women, cohabitation histories collected from men were not directly comparable to those collected from women. For example, interviews conducted between 2006–2010 collected cohabitation dates for men’s current and former partners, but exclude dates for more than these two cohabitations. Therefore, only female respondents were included in the analysis. Applied weights made the analytic sample nationally representative of women ages 15–44 in the United States. Further, cluster and stratification variables were employed to take into consideration the complex sampling design of the NSFG (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2015, 2016).

The merged data from the three groups of interviews resulted in 25,523 women. The sample was limited to respondents age 28 or older at the time of the interview to maximize the utility of the data for studying young adulthood, as well as to ensure young adult cohabitation experiences applied to women interviewed in all collected years (n=13,775). Women who were not born between 1960 and 1984 were excluded (n = 565), which resulted in 13,210 remaining respondents. We excluded women who cohabited before the age of 16 (n = 351), resulting in 12,859 women in our sample to conduct descriptive analyses of overall trends in serial cohabitation. The distribution of the sample across the birth cohorts is presented in Appendix Table 1 for review. Analyses of women at risk of serial cohabitation were further restricted to those who ended their first cohabiting union between the ages of 16 and 28 (n = 2,491). This upper age limit means that serial cohabitation after age 28 was not captured in these analyses. Supplemental analyses indicated that 5% of women who did not serially cohabit during young adulthood went on to do so after age 28. Sixty-six (1.8%) women reported forming their second cohabiting union prior to ending their union with their first cohabiting partner, and were excluded from the analysis (n = 66), resulting in a final sample size of 2,425.

To conduct discrete time event-history analyses, we converted our data into “person-month” records, with one observation during each month a woman was at risk of experiencing a second cohabitation between ages 16 and 28. Women became at risk of serial cohabitation based on the date their first cohabiting union dissolved. They remained at risk of cohabitation from the month of dissolution to either entry into a second cohabiting union or censoring. Censoring occurred in two cases: first, if a woman did not form a second cohabiting union by the age of 28; second, if a woman directly married (n = 276). This second case censored both women who directly married and remained married, and women who married and then went on to cohabit again, meaning that we did not capture any postmarital cohabitation.

Dependent Variable

To capture the experience of forming a second cohabiting union during young adulthood, we relied on the dates at which respondents formed their second cohabiting union to clock their time to repartnering. Cohabitation experience was captured with questions including wording such as “Do not count “dating” or “sleeping over” as living together. By living together, I mean having a sexual relationship while sharing the same usual residence.” Respondents reported on the start and end dates of their cohabitation experiences in months.

Independent Variables

The focal independent variable was birth cohort. We used the respondent’s birth year in order to capture cohort change in cohabitation. Using birth years that spanned from 1960 to 1984 allowed us to capture five distinct birth cohorts encompassing the last five years of the Baby Boom birth cohort (1960–1964), all of Generation X (1965–1968, 1970–1974, 1975–1979) and the first four years of the Millennial cohort (1980–1984). Because of the age limitation, more cases were drawn from the earlier 2002 and 2006–2010 samples, with a majority (n=1,214) of cases drawn from 2006–2010. Our results are presented by birth cohort.

Race and ethnicity were categorized (a) Hispanic, (b) non-Hispanic White, (c) non-Hispanic Black, and (d) non-Hispanic Other. The respondent’s race and ethnicity were ascertained by a direct question of whether the respondent identified as Hispanic, Latina, or of Spanish origin, as well as if they identified as Black/ African American, or White. Those who identified an ethnic origin were coded as Hispanic, and those who did not were coded by their identification as Black, White, or any Other race. Education, measured at the date of the interview, was coded into four categories: (a) less than a high school education, (b) high school diploma or GED, (c) some college with no degree or associate’s degree, and (d) bachelor’s degree or higher. We included a control for family background, which determined whether the respondent lived with two biological or adoptive parents until age 18 to gauge the respondent’s family structure of origin.

We included three indicators measuring women’s relationship history. Drawing on questions about sexual partnership histories and cohabitation histories, the number of sexual partners outside of cohabitation was collected by subtracting the number of sexual partners from the number of cohabiting partners. Childbearing experience was based on whether women reported having a birth before their first cohabiting union dissolved. Women’s age at first cohabitation dissolution was constructed using the end date of their first cohabiting union and their date of birth.

Analytic Plan

To examine the experience of serial cohabitation for Baby Boomers, Generation X, and Millennials, we begin by describing the pathways into becoming at risk of serial cohabitation during young adulthood (Figure 1). Next, we present descriptive statistics to provide a general snapshot of women who are at risk of serial cohabitation during young adulthood (ages 16–28) (Table 1). We introduce our event-history analyses by presenting women’s cumulative estimates of serial cohabitation based on life tables (Figure 2). Using discrete time logistic regression, we explore the transition to serial cohabitation during young adulthood with birth cohort as our focus (Table 2). In our full model, we test the association between birth cohort and serial cohabitation with the inclusion of socioeconomic indicators and relationship history. Finally, to determine whether the observed cohort differences were explained by cohort shifts in sociodemographic characteristics and relationship history, we directly standardize the cumulative proportions of women serially cohabiting for birth cohorts significantly different than our reference cohort born 1960–1964 (Table 3). All results are weighted and adjusted for the survey design effects.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for women at risk for premarital serial cohabitation (ages 16–28) by birth cohort

| N = 2,425 | Birth Cohort |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960–1964 | 1965–1969 | 1970–1974 | 1975–1979 | 1980–1984 | |

| (Baby Boomers) |

(Generation X) |

(Millennials) |

|||

| % / M | % / M | % / M | % / M | % / M | |

| Sociodemographics | |||||

| Racial/ethnic group | |||||

| non-Hispanic White | 73.2 | 68.2 | 67.0 | 66.4 | 64.0 |

| non-Hispanic Black | 11.4 | 18.1 | 16.7 | 14.2 | 18.4 |

| Hispanic | 10.7 | 7.5 | 12.2 | 14.5 | 13.7 |

| non-Hispanic Other | 4.8 | 6.2 | 4.2 | 4.9 | 3.9 |

| Education | |||||

| Less than high school | 9.6 | 11.2 | 12.3 | 10.1 | 10.5 |

| High school diploma or GED | 37.0 | 33.4 | 29.0 | 35.5 | 33.5 |

| Some college, associate’s degree | 26.2 | 28.3 | 33.1 | 31.9 | 39.8 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 27.2 | 27.2 | 25.7 | 22.5 | 16.2 |

| Family background | |||||

| Raised with two biological parents | 61.6 | 51.1 | 52.0 | 44.7 | 47.1 |

| Relationship history | |||||

| Number of non-cohabiting sex partners (mean) | 9.8 | 8.8 | 9.7 | 10.4 | 10.9 |

| Childbearing experience | |||||

| Child before first cohabitation dissolution | 27.2 | 28.1 | 30.1 | 35.2 | 33.9 |

| Age at first cohabitation dissolution (mean) | 22.7 | 23.0 | 22.6 | 22.3 | 22.6 |

| N | 178 | 448 | 715 | 661 | 423 |

Note: All values are weighted.

Source: 2002, 2006–2010, and 2011–2013 National Survey of Family Growth

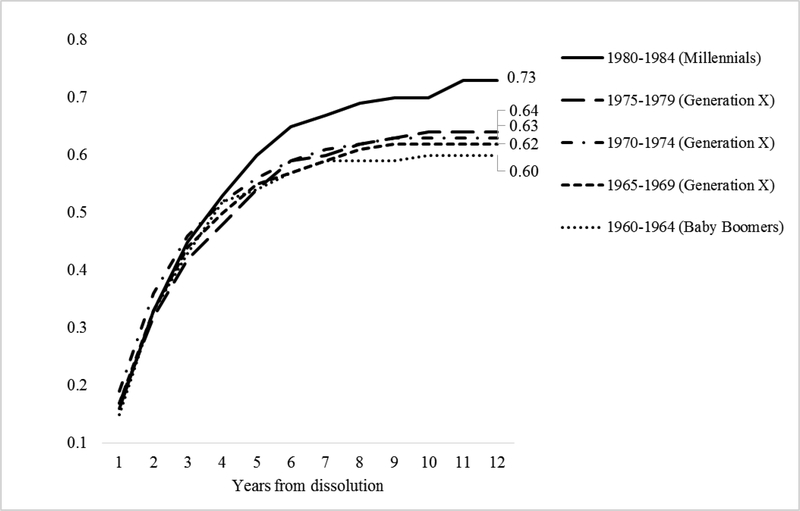

Figure 2. Women’s Entry Into Second Cohabitation Following Dissolution (Ages 16–28) (N = 2,425).

Source: 2002, 2006–2010, and 2011–2013 National Survey of Family Growth

Table 2.

Discrete Time Logistic Regression of Cohort on Serial Cohabitation After Dissolution of First Cohabitation

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | SE | Odds Ratio | SE | |||

| Birth cohort (reference = 1960–1964 [Baby Boomers]) | ||||||

| 1965–1969 (Generation X) | 1.08 | 0.21 | 1.17 | 0.24 | ||

| 1970–1974 (Generation X) | 1.19 | 0.19 | 1.19 | 0.21 | ||

| 1975–1979 (Generation X) | 1.27 | 0.22 | 1.26 | 0.24 | ||

| 1980–1984 (Millennials) | 1.53 | * | 0.29 | 1.52 | * | 0.32 |

| Months since cohabitation dissolution | 0.98 | *** | 0.001 | 0.98 | *** | 0.001 |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Racial/ethnic group (reference = non-Hispanic White) | ||||||

| non-Hispanic Black | 0.56 | *** | 0.07 | 0.66 | *** | 0.07 |

| Hispanic | 0.72 | ** | 0.08 | 0.74 | ** | 0.09 |

| non-Hispanic Other | 0.69 | 0.18 | 0.71 | 0.20 | ||

| Education (reference = high school diploma or GED) | ||||||

| Less than high school | 1.18 | 0.15 | 1.15 | 0.15 | ||

| Some college, associate’s degree | 0.88 | 0.11 | 0.88 | 0.11 | ||

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 0.84 | 0.10 | 0.91 | 0.10 | ||

| Family background | ||||||

| Not raised with two biological parents (reference = two parents) | 1.09 | 0.11 | 1.01 | 0.11 | ||

| Relationship history | ||||||

| Number of non-cohabiting sex partners | 1.00 | 0.004 | ||||

| Age at first cohabitation dissolution | 0.90 | *** | 0.02 | |||

| Childbearing experience (reference = no child) | ||||||

| Had a child before first cohabiting union dissolved | 0.95 | 0.11 | ||||

| N of person-year observations | 124,311 | |||||

| N of persons | 2,425 | |||||

p < .10

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Note: All values are weighted.

Source: 2002, 2006–2010, 2011–2013 National Survey of Family Growth

Table 3.

Predicted percent serially cohabiting using Millennial cohort and Baby Boomer cohort means and coefficients

| Coefficients | Means | |

|---|---|---|

| 1980–1984 (Millennial) | 1960–1964 (Baby Boomer) | |

| 1980–1984 (Millennial) | 67.0 | 73.4 |

| 1960–1964 (Baby Boomer) | 59.7 | 60.6 |

Notes: Predicted values based on event history logistic regression model of serial cohabitation that includes indicators for variables shown in Table 2 (Model 2). Logistic regression not shown.

Source: 2002, 2006–2010, 2011–2013 National Survey of Family Growth

RESULTS

A key motivation of our research is to clarify the measurement of serial cohabitation. Our strategy to measure the prevalence of serial cohabitation was to restrict analyses to women who dissolved their first cohabiting union. Figure 1 illustrates this pathway, which was the most common pathway into becoming at risk of serial cohabitation for young adult women who experience their first cohabiting union between ages 16 and 28 (N = 7,027). ). Of these women, 29% (N = 2,346) dissolved their first cohabiting union whereas 52% married their first cohabiting partner and are no longer at risk of premarital serial cohabitation. 61% of young adult women at risk for serial cohabitation went on to cohabit again between the ages of 16 and 28 prior to marrying. For the remainder of young adult women who were at risk, they experienced marriage before cohabiting again (N = 115). Applying these constraints, the share of young adult women at risk for premarital serial cohabitation increased from 30% to 44% between women born in the 1960–1964 birth cohort and women born in the 1980–1984 birth cohort (Appendix Table 1). Considering serial cohabitation among women who dissolved their first cohabiting union is an unexplored approach employed in our analyses.

Previous estimates of serial cohabitation in the United States considered serial cohabitation experiences among women prior to their first marriage and ever married (see Lichter et al., 2010; Cohen and Manning, 2010) or women who had ever cohabited (Vespa, 2014). We find that 6% of American women born between 1960 and 1964 serially cohabited whereas 13% of women born between 1980 and 1984 serially cohabited in young adulthood, and among cohabitors, 15% of Baby Boomers had serially cohabited in contrast to 24% of Millennials. (Appendix Table 1).

The characteristics of women at risk of serial cohabitation in Table 1 differ from a general population of women by comparison (see Appendix Table 1). Table 1 shows that the profile of women at risk of serial cohabitation in the U.S. changed over time. Although the majority of women at risk for serial cohabitation were non-Hispanic White, the share of non-White women at risk increased overall between the oldest birth cohorts and youngest. More women born between 1980 and 1984 who were at risk for serial cohabitation reported having some college education or an associate’s degree than older cohorts of women, but fewer had a bachelor’s degree or higher. Though the share of women with a college degree increased across cohorts in the general population (see Appendix Table 1), this trend was not apparent in the population of women in our risk set. The share of women growing up with both parents decreased across birth cohorts among women who were at risk of serial cohabitation. On average, women in our risk set who were born in the 1980–1984 cohort had one additional sex partner compared to women born between 1960 and 1964. Over time, more women reported having a child before dissolving their first cohabiting union, therefore entering our risk set with a child. Among women at risk for serial cohabitation, the average age at union dissolution remained at an average age of 23. In reference to our first research question, we find that the share of young adult women serially cohabiting increased across birth cohorts (Table 1).

We estimated cohort-specific life tables for Figure 2. Life tables were calculated by cohort, representing the proportion of women who formed second cohabiting unions in each interval (or each year since the dissolution of their first cohabiting union). Each interval began with the adjusted share of women at risk (i.e, excluded women who experienced a second cohabiting union and women who were censored within that year; see Preston, Heuveline, and Guillot, 2001 for an overview). Although those born between 1960 and 1979 had similar proportions serially cohabiting by age 28, ranging from 60% to 64%, 73% of women born in the 1980–1984 cohort serially cohabited following the dissolution of their first cohabitation. Additionally, the average time to serial cohabitation following the dissolution of women’s first cohabiting union decreased over birth cohorts (results not shown). On average, among women born between 1960 and 1964, women entered a second cohabiting union after 47 months (roughly 4 years) compared to entry after 26 months (roughly 2 years) among women born between 1980 and 1984.

Our second research question concerned whether the likelihood of serial cohabitation was greater for women born after 1964, compared to Baby Boomer women born between 1960 and 1964, accounting for potential cohort changes in the composition of the population based on socioeconomic characteristics. The results of our discrete time logistic regression models are presented in Table 2. In Model 1 the odds of serially cohabiting were 1.53 times greater, or 53% greater, among women born in the 1980–1984 birth cohort compared to women born between 1960 and 1964 after accounting for race and ethnicity, education, and family background. This supports our hypothesis that the odds of serial cohabitation increased for more recent birth cohorts of women. Similar results are obtained when a continuous indicator of birth cohort is applied. With regard to the sociodemographic indicators, racial/ethnic minorities, aside from women who identify with an “Other” race or ethnicity, had a far lower hazard than non-Hispanic White women to serially cohabit.

Model 2 incorporated women’s relationship history, indicated by their number of sex partners, age at first cohabitation dissolution, and childbearing experience. Net of these characteristics, the associations in Model 1 persisted. Women born between 1980 and 1984 continued to have significantly greater odds (52%) of serially cohabiting compared to women born between 1960 and 1964. Of the additional relationship history characteristics, women’s age at first cohabitation dissolution was significantly related to serial cohabitation. Every year women’s age at dissolution increased, their odds of serially cohabiting decreased by 10%.

In answering our third research question, we interacted each predictor with an indicator of whether women were born in the earliest birth cohort (1960–1964) or the latest birth cohort (1980–1984) and tested for significance in order to assess whether these traditional predictors of serial cohabitation persisted over time (not shown). Additionally, we tested whether these interactions were significant when using a continuous indicator of birth cohort. Contrary to our hypothesis, we find only one significant interaction. The effect of women’s age at their first cohabitation dissolution was significant and positive for Millennial women. This suggests that the role of women’s age at cohabitation dissolution may be weakening. This may be explained in part by the faster transition to a second cohabitation among Millennials. While generally the socioeconomic and relationship characteristics were similarly associated with the odds of serially cohabiting across birth cohorts, small sample sizes may have led to low statistical power for many interactions.

Given the shifting composition of cohabitors across birth cohorts (Table 1) and the significantly higher odds of serial cohabitation among women born between 1980 and 1984 (Millennials) compared to women born between 1960 and 1964 (Baby Boomers), we directly standardized the predicted proportion of serial cohabitors among these two birth cohorts to explore whether sociodemographic and relationship characteristic differences contributed to the increase in serial cohabitation between Baby Boomer and Millennial women. We find that the estimates of serial cohabitation for Millennials increased when their characteristics were standardized to match those of the late Baby Boomers. Table 3 shows that standardization increased the probability of serial cohabitation among Millennials, from 67% to 73% when using person-year means from the 1960–1964 birth cohort. In other words, the predicted probability of serial cohabitation would have been slightly higher for the 1980–1984 birth cohort if they had the same composition as the 1960–1964 cohort. The predicted probabilities for logistic regression models estimated using sample means did not perfectly match the observed probabilities (e.g., Cancian et al. 2014); nevertheless, they are similar to the values displayed in Figure 2. So, although there was a marked and significant increase in serial cohabitation across birth cohorts, it appears that Millennial’s sociodemographic and relationship characteristics did not explain this increase, but instead tempered the increase that would have occurred if women’s sociodemographic and relationship characteristics had not shifted from the 1960–1964 birth cohort.

DISCUSSION

The goal of our study was to document cohort trends in serial cohabitation, with four primary research questions. The first research question established the cohort trends in serial cohabitation. While serial cohabitors continue to make up a minority of cohabiting women in the United States, this share continues to grow with no indication of reversal. We find that one in four Millennials who had ever cohabited, cohabited more than once. Consistent with prior work documenting increases in serial cohabitation in the U.S., (Lichter et al. 2010; Vespa 2014), there is a doubling in serial cohabitation from 6% of Baby Boomer women—born between 1960 and 1964—and 13% of Millennial women—born after 1980—having serially cohabited during young adulthood. This increase stems in part from a growing share of young adults who have ever cohabited (43% of Baby Boomers and 54% of Millennials), as well as increasing instability of cohabiting unions, as 30% of Baby Boomers in contrast to 46% of Millennials dissolved their first cohabiting union. Overall, one-quarter of Millennials are at risk of serial cohabitation in contrast to only 16% of the Baby Boomer cohort.

The second research question assessed the likelihood of serial cohabitation during young adulthood. Young adult women born between 1980 and 1984 had over 50% higher odds of forming a second cohabiting union during young adulthood compared to women born between 1960 and 1964, even after controlling for sociodemographic and relationship characteristics such as their number of sex partners and their childbearing behavior. Not only are Millennials more likely to serially cohabit, they form their unions much more quickly, with on average only 2 years between the end of their first and start of their second cohabitation.

The third research question examined the traditional predictors of serial cohabitation, and whether these characteristics continued to predict serial cohabitation among the youngest birth cohort of women. We adopted a framework that draws on the remarriage and re-partnering literature and assess the odds of serially cohabiting during young adulthood among women who dissolved their first cohabiting union. These represent the women at risk, or women who are exposed to forming a new union. We highlighted the pathway into serial cohabitation that is most common for young adult women. Narrowing the analyses to this group of women has measurement value as it avoids confounding associations: Our research suggests that the characteristics previously associated with serial cohabitation may actually be associated with union dissolution. Using this measurement of women at risk for serially cohabiting may be useful to parse out selection related to both dissolution and serial cohabitation to consider serial cohabitation among women on somewhat “even ground”. This approach aligns our work with the remarriage literature and draws attention to the importance of including cohabitation in models of re-partnering. Among young adult women in the United States, most serial cohabitation has occurred prior to every marrying, but as future research considers women above the age of 28, we suspect these pathways will further diverge. In addition, future research should consider the possible pathways out of a first cohabiting union, such as directly marrying or staying single, relative to cohabiting again. These pathways may be most pronounced among earlier birth cohorts, of whom fewer women serially cohabit.

The final research question determined whether the cohort divide in serial cohabitation remained after we standardized the characteristics of the earliest and latest cohorts to one another. It appears that the sociodemographic and relationship characteristics of Millennials may have counterbalanced the increase in serial cohabitation during young adulthood, specifically race and ethnicity. Previous research indicates that racial and ethnic minorities were less likely to serially cohabit than White women (Cohen and Manning, 2010; Lichter et al., 2010; Lichter and Qian, 2008). We find that if women born between 1980 and 1984 had the same average sociodemographic and relationship characteristics as women born between 1960 and 1964, their predicted probability of serially cohabiting would be 6% higher. This is apparently driven by race and ethnicity, as Black and Hispanic Millennial women continue to have significantly lower odds of serial cohabitation during young adulthood compared to White women.

Given the persistent association between race and ethnicity and serial cohabitation in the United States, as the characteristics of women who are at risk of serial cohabitation shift to include more racial and ethnic minorities we may find that the increase in serial cohabitation will become less dramatic across more recent birth cohorts. These characteristics appear to offset the increase in serial cohabitation between women born in the 1960–1964 birth cohort and women born in the 1980–1984 birth cohort.

If the increase in serial cohabitation is not driven by changes in the composition of younger birth cohorts of American women at risk for serial cohabitation, it is likely that it is fueled by period effects that reflect a growing acceptance of cohabitation during young adulthood as well as greater acceptance across the life course (Brown and Wright, 2016). Among U.S. high school seniors in 2014, those just launching into young adulthood, 71% agree that cohabitation is an ideal way to test compatibility with a future marriage partner. This is a substantial increase from the reported levels in the mid-1980s (47%) (Anderson, 2016). These young adults represent some of the youngest Millennials, and their attitudes toward cohabitation as a testing ground for marriage may indicate an acceptance for multiple cohabiting unions on the path to finding their ultimate marriage mate. These hypothesized period effects are consistent with the context of young adulthood as a time of romantic exploration (Arnett, 2000).

The finding that relationship characteristics continue to play a role in the odds of serial cohabitation during young adulthood may also illustrate the uncertainty and instability of young adulthood in the United States (Arnett, 2006; Settersten, 2012). The course of young adulthood in America has become more imprecise, and this blurriness may foster uncertainty and vulnerability in young adult’s relationships, leading to unstable partnerships that less often lead to marriage. The evolution of young adult women’s relationship behaviors to increasingly include serial cohabitation may be a response to the current context of this life stage: Uncertainty paired with high rates of cohabitation.

While this study cannot identify the specific factors leading to cohort change into the risk set, our redefinition of who is at risk of serial cohabitation allows us to conclude that previous research may have rather illustrated determinants of union dissolution, rather than selection into serial cohabitation. We find that not all of the characteristics previously associated with serial cohabitation (Lichter et al., 2010; Cohen and Manning, 2010) are upheld among our redefined analytic population. Growing up without two biological parents, women’s number of sex partners, and educational attainment do not continue to be significant predictors of serial cohabitation during young adulthood. At the same time, additional analyses of whether the predictors of serial cohabitation have changed between the earliest 1960–1964 birth cohort and the latest 1980–1984 birth cohort indicate that these relationships are largely unchanged across birth cohorts. We cannot, therefore, claim that diffusion is clearly at work, as these previous associations may be eliminated due to our redefinition of who is at risk for serial cohabitation. As these women have experienced both the formation and the dissolution of a cohabiting union, they are selective compared to women who have not experienced both of these events. Therefore, the diffusion of serial cohabitation in a more general population of young adult women may appear with different associations and at a different rate.

This study provides new insights into serial cohabitation among young adult women in the United States, albeit with a few limitations. First, our approach is limited to the processes that occur after the first cohabitation dissolution and does not account for the unequal entry into the analytic populations across cohorts. The increase in cohabitation experience for contemporary young adult women cuts across race and education levels, but the outcomes of these unions do not. Cohabiting women without a college degree, as well as Black women, are less likely to transition to marriage from their first cohabiting union (Kuo and Raley, 2016). However, a growing proportion of cohabitors remain together by five years, and while there are few educational differences, these women are disproportionately less likely to be Black (Kuo and Raley, 2016). These shifting selection processes may explain why few of the sociodemographic cherlcharacteristics predict entry into a second union. Supplemental analyses (not shown) suggest that the characteristics of both Baby Boomers and Millennials who are at risk for serial cohabitation differ from those of their birth cohort who were not at risk, as well as from each other. A significantly larger share of Baby Boomer women at risk for serial cohabitation were White and grow up without two biological parents, and significantly fewer were Hispanic compared to women who were not at risk for serial cohabitation. Conversely for Millennials, significantly more women at risk for serial cohabitation were Black, had a high school diploma, and grew up without two biological parents. For both birth cohorts, significantly fewer women at risk for serial cohabitation were college graduates. Second, the NSFG is a cross-sectional survey, which does not allow assessments of temporal ordering of the associations between the correlates and serial cohabitation. Third, this study is limited to the cohabitation behavior of women. This was necessary because the earlier surveys were limited to women, and the cohabitation history collected from men later on are not wholly comparable. If we could access men’s perspectives, we could ask new questions about gender differences in serial cohabitation. Fourth, this work explores union formation between the ages of 16 and 28—roughly the late years of adolescence and early adulthood. While this is an important time of union formation for many women and we are capturing a significant picture of serial cohabitation, remarriage and divorce at later ages may indicate a growing proportion of women having cohabited more than once after age 28. Opportunities for serial cohabitation will continue as women move into their mid-life. Finally, the data do not include indicators of relationship quality. Similarly important is our exclusion of women who married their first cohabiting partner, but divorced this partner during young adulthood. Future research should consider including both women who serially cohabited before ever marrying and women who lived with a partner prior to marriage and cohabited again after their marriage dissolved. This pathway into serial cohabitation may bring more complexity into a second cohabiting union in regard to stepchildren and union experiences. Though demographic indicators of instability are available in the NSFG, the measures of relationship quality that predict instability would contribute to our understanding of cohabitation. If serial cohabitation continues to be a form of “intensive dating”, then we could expect their relationship quality to vary even further from one-time cohabitors and married individuals. Finally, the changing context of union formation, specifically the length of first cohabiting unions and transitions to marriage, suggests that selection into the population at risk may operate differently for the earliest cohort and the latest. Because of our definition of who is at risk for serial cohabitation, we are unable to account for the unequal entry into the analytic populations across cohorts.

Crafting a better understanding of multiple cohabiting partnerships during young adulthood is crucial for several reasons. The relationship experiences of young adults are more likely to eventuate in cohabitation than ever before, and the risk of serial cohabitation is increasing along with growing shares of women serially cohabiting before age 28. These relationships may be consequential for children as serial cohabitors may be increasingly forming stepfamilies, meaning they or their partners are bringing children from prior relationships (Guzzo, 2017). The living arrangements of children in these unions, then, should be considered in future explorations. Prior research indicates that serial cohabitors are at a higher risk of marital dissolution (Lichter and Qian, 2008), and research should consider whether this association remains as serial cohabitation becomes more common. Cohabitors are also increasingly divided, in terms of relationship quality, by whether they have plans to marry or not, as serial cohabitors are less likely to have marital intentions than one-time cohabitors (Brown, et al, 2015; Vespa, 2014). For a growing minority of young adult women, it may become increasingly important to consider the multiple co-residential partnerships experienced during young adulthood and their association with relationship dynamics. Our research continues to reiterate the increase in the risk of serial cohabitation for a significant, and growing, minority of young adult women. In the face of uncertainty, there may be disadvantages associated with serial cohabitation during young adulthood that may influence both the relationship functioning of cohabitors as well as the well-being of any residential children. However, young adult relationships may be evolving, and young women may be learning to end co-residential relationships that are not working out. These perspectives may vary depending on the pathway taken into serial cohabitation, and future research is needed on the implications of serial cohabitation. As American families continue to be complex, it is important that we use approaches that acknowledge this complexity.

Acknowledgments

Note: This research was supported in part by the Center for Family and Demographic Research, Bowling Green State University, which has core funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P2CHD050959).

Appendix Table 1. Descriptive statistics for all women ages 29+, by birth cohort

| N = 12,860 | Birth Cohort |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960–1964 | 1965–1969 | 1970–1974 | 1975–1979 | 1980–1984 | |

| (Baby Boomers) |

(Generation X) |

(Millennials) |

|||

| Cohabitation Experiences, ages 16–28 | % / M | % / M | % / M | % / M | % / M |

| Ever cohabited | 44.0 | 52.4 | 57.8 | 65.7 | 71.9 |

| One time | 37.1 | 43.0 | 45.8 | 48.8 | 40.8 |

| Serially cohabited | 6.4 | 8.9 | 12.0 | 13.6 | 12.7 |

| Among those who cohabited (N = 7,194) | |||||

| Serially cohabited | 23.3 | 25.9 | 27.2 | 30.5 | 34.3 |

| Dissolved first cohabiting union | 29.9 | 34.8 | 37.7 | 39.6 | 46.4 |

| Demographics | |||||

| Racial/ethnic group | |||||

| non-Hispanic White | 71.0 | 64.1 | 62.0 | 62.4 | 57.5 |

| non-Hispanic Black | 11.9 | 13.8 | 13.7 | 13.3 | 15.5 |

| Hispanic | 12.2 | 14.8 | 18.0 | 17.8 | 20.6 |

| non-Hispanic Other | 5.0 | 7.2 | 6.5 | 6.6 | 6.5 |

| Education | |||||

| Less than high school | 11.3 | 10.0 | 12.3 | 10.6 | 11.5 |

| High school diploma or GED | 32.3 | 29.2 | 27.1 | 26.0 | 23.8 |

| Some college, associate’s degree | 29.7 | 28.3 | 27.0 | 29.2 | 36.1 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 26.8 | 32.5 | 33.5 | 34.3 | 28.6 |

| Family background | |||||

| Raised with two biological parents | 71.1 | 66.2 | 63.2 | 57.2 | 59.2 |

| Relationship history | |||||

| Number of non-cohabiting sex partners | 4.9 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 6.1 | 6.2 |

| N | 1736 | 3263 | 3646 | 2686 | 993 |

Note: All values are weighted.

Source: 2002, 2006–2010, and 2011–2013 National Survey of Family Growth

Contributor Information

Kasey J. Eickmeyer, Email: eickmek@bgsu.edu, Bowling Green State University, Department of Sociology, Bowling Green, OH 43403.

Wendy D. Manning, Email: wmannin@bgsu.edu, Bowling Green State University, Department of Sociology, Bowling Green, OH 43403.

REFERENCES

- Anderson LR, & Payne KK (2016). Median age at first marriage, 2014 Family Profiles, FP-16–07. Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research; https://www.bgsu.edu/ncfmr/resources/data/family-profiles/anderson-payne-median-age-first-marriage-fp-16-07.html [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LR (2016). High school seniors’ attitudes on cohabitation as a testing ground for marriage Family Profiles, FP-16–13. Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research; https://www.bgsu.edu/ncfmr/resources/data/family-profiles/anderson-hs-seniors-attitudes-cohab-test-marriage-fp-16-13.html [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5):469–480. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2006). “Emerging adulthood: understanding the new way of coming of age” pp. 3–20 in “Emerging adults in America: coming of age in the 21st century”, edited by Arnett JJ & Tanner JL. American Psychological Association: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Bogle R, & Wu H-S (2010). Thirty years of change in marriage and union formation attitudes, 1976–2008 Family Profiles, FP-10–103. Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research; https://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and-sciences/NCFMR/documents/FP/FP-10-03.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, Manning WD, & Payne KK (2015). Relationship quality among cohabiting versus married couples. Journal of Family Issues 1–24. doi: 10.1177/0192513X15622236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, & Wright MR (2016). Older adults’ attitudes toward cohabitation: Two decades of change. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71(4), 755–764. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukodi E (2012). Serial cohabitation among men in Britain: Does work history matter? European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 28(4), 441–466. doi: 10.1007/s10680-012-9274-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass L, & Lu HH (2000). Trends in cohabitation and implications for childrens family contexts in the United States. Population Studies, 54(1): 29–41. doi: 10.1080/713779060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancian M, Meyer DR, Brown PR, & Cook ST (2014). Who gets custody now? Dramatic changes in children’s living arrangements after divorce. Demography, 51(4), 1381–1396. doi: 10.1007/s13524-014-0307-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Manning WD (2010). The relationship context of premarital serial cohabitation. Social Science Research 39(5): 766–776. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copen CE, Daniels K, Mosher William D. (2013). First premarital cohabitation in the United States: 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. National Health Statistics Reports 64(64): 1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dommermuth L, & Wiik KA (2014). First, second or third time around? The number of co-residential relationships among young Norwegians. Young, 22(4), 323–343. doi: 10.1177/1103308814548103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eickmeyer KJ (2015). Generation X and Millennials: Attitudes toward marriage & divorce Family Profiles, FP-15–12. Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research; https://www.bgsu.edu/ncfmr/resources/data/family-profiles/eickmeyer-gen-x-millennials-fp-15-12.html [Google Scholar]

- Eyerman R, Turner BS (1998). Outline of a theory of generations. European Journal of Social Theory 1(1): 91–106. doi: 10.1177/136843198001001007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo KB (2014). Trends in cohabitation outcomes: compositional changes and engagement among never‐married young adults. Journal of Marriage and Family 76(4): 826–842. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo KB (2017). Marriage and dissolution among women’s cohabitations: Variations by stepfamily status and shared childbearing. Journal of Family Issues 39(4): 1108–1136. doi: 10.1177/0192513X16686136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiekel N, Liefbroer AC & Poortman AR. (2014). Understanding diversity in the meaning of cohabitation across Europe. European Journal of Population 30: 391 10.1007/s10680-014-9321-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang PM, Smock PJ, Manning WD, & Bergstrom-Lynch CA (2011). He says, she says: Gender and cohabitation. Journal of Family Issues, 32(7), 876–905. doi: 10.1177/0192513X10397601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo JCL, & Raley RK (2016). Diverging patterns of union transition among cohabitors by race/ethnicity and education: Trends and marital intentions in the United States. Demography, 53(4), 921–935. doi: 10.1007/s13524-016-0483-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamidi EO, & Manning WD (2016). Marriage and cohabitation experiences among young adults Family Profiles, FP-16–17. Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research; https://www.bgsu.edu/ncfmr/resources/data/family-profiles/lamidi-manning-marriage-cohabitation-young-adults-fp-16-17.html [Google Scholar]

- Lamidi EO, Manning WD, Brown SL (2015). Change in the stability of first premarital cohabitation, 1980–2009. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, 2014. San Diego, California. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, & Qian Z (2008). Serial cohabitation and the marital life course. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70(4): 861–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00532.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, Turner RN, Sassler S (2010). National estimates of the rise in serial cohabitation/ Social Science Research 39(5):754–765. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.11.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liefbroer AC, & Dourleijn E (2006). Unmarried cohabitation and union stability: testing the role of diffusion using data from 16 European countries. Demography 43(2):203–221. 10.1353/dem.2006.0018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, & Cohen JA (2012). Premarital cohabitation and marital dissolution: An examination of recent marriages. Journal of Marriage and Family 74(2):377–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00960.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Brown SL, Payne KK (2014). Two decades of stability and change in age at first union formation. Journal of Marriage and Family 76(2):247–260. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, & Stykes B (2015). Twenty-five years of change in cohabitation in the U.S., 1987–2013. (FP-15–01). Resource document. National Center for Family & Marriage Research; http://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-ofarts-and-sciences/NCFMR/documents/FP/FP-15-01-twentyfive-yrs-changecohab.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- McNamee CB, & Raley RK (2011). A note on race, ethnicity and nativity differentials in remarriage in the United States. Demographic Research, 24, 293. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2011.24.13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preston S, Heuveline P, & Guillot M (2001). Demography: Measuring and modeling population processes. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Sassler S (2004). The process of entering into cohabiting unions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(2), 491–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2004.00033.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Settersten RA Jr. (2012). “The contemporary context of young adulthood in the USA: From demography to development, from private troubles to public issues” pp. 11–26 in Early adulthood in a family context: National symposium on family issues, edited by Booth A, McHale SM, Landale NS, Brown SL, and Manning WD. Springer: New York City, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Teachman JD, & Heckert A (1985). The impact of age and children on remarriage: Further evidence. Journal of Family Issues, 6(2), 185–203. 10.1177/019251385006002003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2015). Public use data file documentation: 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2016). Public use data file documentation: 2011–2013 National Survey of Family Growth. Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Vespa J (2014). Historical trends in the marital intentions of one-time and serial cohabitors. Journal of Marriage and Family 76(1):207–217. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12083 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White LK, & Booth A (1985). The quality and stability of remarriages: The role of stepchildren. American Sociological Review, 689–698. doi: 10.2307/2095382 [DOI] [Google Scholar]