Abstract

Autophagy is a conserved process that is critical for sequestering and degrading proteins, damaged or aged organelles, and for maintaining cellular homeostasis under stress conditions. Despite its dichotomous role in health and diseases, autophagy usually promotes growth and progression of advanced cancers. In this context, clinical trials using chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as autophagy inhibitors have suggested that autophagy inhibition is a promising approach for treating advanced malignancies and/or overcoming drug resistance of small molecule therapeutics (i.e., chemotherapy and molecularly targeted therapy). Efficient delivery of autophagy inhibitors may further enhance the therapeutic effect, reduce systemic toxicity, and prevent drug resistance. As such, nanocarriers-based drug delivery systems have several distinct advantages over free autophagy inhibitors that include increased circulation of the drugs, reduced off-target systemic toxicity, increased drug delivery efficiency, and increased solubility and stability of the encapsulated drugs. With their versatile drug encapsulation and surface-functionalization capabilities, nanocarriers can be engineered to deliver autophagy inhibitors to tumor sites in a context-specific and/or tissue-specific manner. This review focuses on the role of nanomaterials utilizing autophagy inhibitors for cancer therapy, with a focus on their applications in different cancer types.

Keywords: Autophagy, cancer, nanomaterials, drug delivery, theranostics

Graphical Abstract

Autophagy is a conserved process that is critical for sequestering and degrading proteins, damaged or aged organelles, and for capturing nanoparticles. Clinical trials have suggested that autophagy inhibition is a promising approach for treating advanced malignancies. With their versatile drug encapsulation and surface-functionalization capabilities, nanocarriers-based delivering of autophagy inhibitors have several distinct advantages over free autophagy inhibitors.

1. Introduction

Chemotherapy and molecularly targeted therapy are two of the current standard strategies for cancer treatment. However, the major drawback of these therapeutic options is drug resistance. Notably, multidrug resistance (MDR) is a phenomenon characterized by cancer cells that become resistant to one drug while also resisting other structurally or functionally dissembled drugs.[1] Several potential mechanisms can lead to drug resistance, such as limited drug delivery, increased drug efflux, mutations of the drug target, DNA damage repair, evasion of cell death, and activation of alternative signaling pathways. In addition, the heterogeneous nature of tumor cells may also contribute to drug resistance in a subpopulation of tumor cells. As the understanding of the role of autophagy in cancer initiation and development gradually increased in recent years, both preclinical and clinical studies have demonstrated that autophagy can promote cell survival during cytotoxic or molecularly targeted drug therapy. For example, treatment with chloroquine (CQ, an inhibitor of autophagy) enhanced tumor regression in response to alkylating agents in a mouse model of lymphoma.[2] Similarly, initial clinical studies demonstrated that patients with glioblastoma benefited from autophagy inhibition therapy using CQ.[3, 4] Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ, another autophagy inhibitor) was found to sensitize human cancer cells to cancer therapy,[5] and is being actively investigated in clinical trials for increased cancer treatment efficacy by combining with other therapeutics.[6] More importantly, CQ successfully overcomes vemurafenib (a BrafV600E specific inhibitor) resistance in pediatric brain tumors harboring BrafV600E mutation,[7] which was further confirmed by a more recent study from the same team.[8] These results collectively indicate that autophagy inhibition provides a promising way to circumvent drug resistance, which might avoid targeting the same or similar kinase pathways and therefore could apply to multiple different mechanisms of kinase inhibitor resistance. Less commonly, there were studies reporting that autophagy had a tumor-suppressive role when the function of Beclin1 was attenuated,[9, 10] or when Atg7 deletion was specifically targeted to the liver.[11, 12] Indeed, autophagy has a complicated role in cancers, which is dependent on many biological factors (e.g., tumor type, oncogenic event) as well as the tools used to investigate this process.13 Still, in many cases, autophagy promotes the survival of cancer cells by providing the building blocks needed for biosynthesis.[14] Therefore, inhibiting autophagy is a promising therapeutic approach being actively investigated.

Common concerns in using autophagy inhibitors for cancer therapy are their rapid clearance, poor drug delivery to tumor sites, toxicity and drug resistance associated with higher drug doses. Nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems are showing great promise in overcoming these obstacles by harnessing the superior drug-loading ability of nanocarriers and by facilitating tumor-targeted drug delivery.[15-17] Various nanodrugs have been clinically approved and used to enhance site-specific drug delivery in many instances.[18] In addition to its role in inhibiting autophagy, administration of CQ could reduce nanoparticle accumulation in the liver and normalize tumor vasculature, which will help improve drug delivery efficiency.[19, 20] In this review, we first briefly introduce the mechanisms of autophagy and also modulators of autophagy, then we will discuss nanomaterial-mediated regulation of autophagy with a focus on their potential application for cancer therapy. Finally, we summarize the limitations of current nanomaterial-based autophagy-regulating strategies for cancer therapy and propose novel strategies for future development.

2. Overview of Autophagy and Autophagy Modulators

Macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy) is a catabolic process regulated by a series of proteins encoded by more than 30 autophagy-related genes, protecting organisms and cells from metabolic stressors (e.g., nutrient deprivation).[21] Autophagy is usually initiated in the cytoplasm where cellular and foreign material are first engulfed by autophagosomes and then degraded and recycled after autophagosomes are trafficked and fused with lysosomes. The detailed process of autophagy has been excellently reviewed in multiple reviews.[21-23] Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) is the most traditional and powerful method to monitor double-membraned autophagosomes or confirm results obtained using other methods.[24] To date, the conversion of the soluble form of LC3 (LC3-I) to the membrane-associated form of LC3 (LC3-II) has greatly facilitated the detection of autophagy. The conversion of LC3 upon autophagy activation can be assessed using light microscopy and biochemical methods.[25, 26] Additionally, activation of autophagy is usually accompanied by recruitment and degradation of p62. Consequently, the cellular level of p62 inversely correlates with autophagic activity.[27] To overcome the pitfalls of each method and avoid erroneous assessment of autophagy, dynamic rather than static autophagy in a given cellular setting should be measured using proper methods simultaneously.[28-30]

In addition to its role in basic physiology and tissue homeostasis, autophagy is closely involved in the initiation and development of various kinds of cancers.[14, 31] Similar to that observed in BrafV600E-driven tumors,[7, 8, 32] autophagy promotes the growth of Ras-driven tumors by, in part, maintaining glycolytic capacity.[33, 34] The central role of autophagy in sustaining cancer cell glycolysis was further reported in chronic myeloid leukemia[35] and in pancreatic cancer.[36] When it comes to targeting autophagy for cancer therapy, several promising inhibitors targeting the components of the autophagy pathway have been investigated, including inhibitors of the ULK1 kinase,[37, 38] Vps34 inhibitors,[39-41] ATG4B inhibitor,[42] lysosome inhibitors.[43-46] Despite being extensively investigated in preclinical settings, none of the novel autophagy inhibitors targeting specific autophagy proteins have entered clinical trials. In comparison, CQ and HCQ become deprotonated and entrapped in lysosomes and as a result, increase the lysosomal pH and block the final step of the autophagy signaling pathway.[47] For clinical trials, HCQ is chosen over CQ as an autophagy inhibitor because of its relatively less toxicity compared to CQ at peak plasma concentrations.[48-50] Several clinical trials involving HCQ in as a single-agent trial or in combined treatment regimens have been published.[13] Therefore, future studies exploring nanomaterial-mediated inhibition of autophagy may use these classical as well as novel autophagy inhibitors (Table 1). In addition to these inhibitors, autophagy-inducing peptides and small molecules are also being developed.[51-53] Autophagy induction has shown promise for treating neurodegenerative disorders and infectious diseases.[52, 54]

Table 1:

Summary of representative autophagy inhibitors

| Agent | Target | Tumor types | Status | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chloroquine | Lysosome | Glioblastoma, brain Metastases, etc. | Clinical trials | [6] |

| Hydroxychloroquine | Lysosome | Colorectal cancer, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, etc. | Clinical trials | [6, 50] |

| Quinacrine | Lysosome | Lung cancer, osteosarcoma | Clinical trials | [199, 200] |

| 3-methyladenine | Beclin/vps34 complex | Prostate cancer, leukemia, etc. | Preclinical | [201,202] |

| Wortmannin | Beclin/vps34 complex | Breast cancer, melanoma, etc. | Preclinical | [70, 203] |

| Spautin-1 | Beclin/vps34 complex | Ovarian cancer, breast cancer, etc. | Preclinical | [39, 204] |

| SAR405 | vps34 | Renal cancer, head and neck cancer, etc. | Preclinical | [40, 205] |

| PIK-III | vps34 | Pancreatic cancer, etc. | Preclinical | [206] |

| Autophinib | vps34 | Breast cancer | Preclinical | [41] |

| UAMC-2526 | ATG4 | Colorectal cancer | Preclinical | [207] |

| Autophagin-1 | ATG4 | Not reported | Preclinical | [208] |

| NSC185058 | ATG4 | Osteosarcoma, glioblastoma | Preclinical | [209, 210] |

| SBI-0206965 | ULK1 | Lung cancer, colorectal cancer | Preclinical | [37, 211] |

| ULK-101 | ULK1 | Lung cancer | Preclinical | [38] |

| Lys05 | Lysosome | Melanoma, ovarian cancer | Preclinical | [43, 212] |

| DQ661 | Lysosome | Melanoma, pancreatic cancer, and colorectal cancer | Preclinical | [46, 213] |

| ROC-325 | Lysosome | Renal cancer | Preclinical | [214, 215] |

| VATG-027 | Lysosome | Melanoma | Preclinical | [216] |

| VATG-032 | Lysosome | Melanoma | Preclinical | [216] |

| Mefloquine | Lysosome | Breast cancer, etc. | Preclinical | [217] |

| Verteporfin | Lysosome | Breast cancer, etc. | Preclinical | [218] |

3. Effects of Nanoparticles on Autophagy

Nanoparticles (NPs) can be divided into two general categories: organic NPs (such as polymeric, liposomes, micelles, etc.) and inorganic NPs (such as gold, silica, iron oxide, etc.).[17, 18, 55] Inorganic NPs have been substantially investigated in preclinical studies, however, only several of them have been successfully translated to the clinic for imaging applications [56, 57] or for treatment purposes.[58] In comparison, organic NPs have been widely used in the clinic for a variety of applications. This has largely been used for drug delivery purposes, where long-lasting delivery of small molecule drugs and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) can be used to treat both cancer and non-cancerous diseases.[18, 59]

It is important to mention that NPs can function as autophagy inducers and trigger baseline autophagy activity.[60-62] A variety of NPs including liposomes,[63] PLGA NPs,[64] poly-(ethylenimine)-based NPs,[29] poly(methacrylic acid)-based NPs,[30] silica NPs,[65-67] gold NPs,[68, 69] silver NPs [70, 71], carbon nanotubes,[72] quantum dots,[73, 74] ferroferric oxide NPs,[75, 76] selenium NPs,[77] poly-ethylene-imine (PEI) NPs,[78] have been reported capable of inducing autophagy. While many of the NPs induce prosurvival autophagy,[62] certain NPs may induce mitochondria-dependent autophagic cell death.[79, 80] On the contrary, other NPs may inhibit the activity of autophagy, such as the nanodiamonds reported by Cui et al. [81] It is also worth noting that both physical and chemical characteristics (e.g., chemical composition, surface chemistry modifications, size, shape, length, crystal phase) may greatly affect the autophagy modulation ability of the NPs, exemplified by different carbon nanotubes.[82-85]. Intracellular signaling pathways can be regulated by NPs that can affect autophagy activity. An example of this is the regulation of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), which has been shown to be closely associated with autophagy activity.[86, 87] Although the major role of autophagy is to degrade and recycle foreign pathogens, damaged organelles, intracellular substrates and long-lived proteins, autophagy may attempt to track and degrade intracellular NPs after being activated (Figure 1).[88] Additionally, if vesicle trafficking and/or enzyme activity of lysosomes are inhibited by nanomaterials, an increased accumulation of autophagosomes will occur because the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes is suppressed. Therefore, the role of nanomaterials in triggering local or systematic autophagy or in inducing autophagic dysfunction needs to be thoroughly investigated before exploiting them to deliver autophagy inhibitors for cancer therapy.

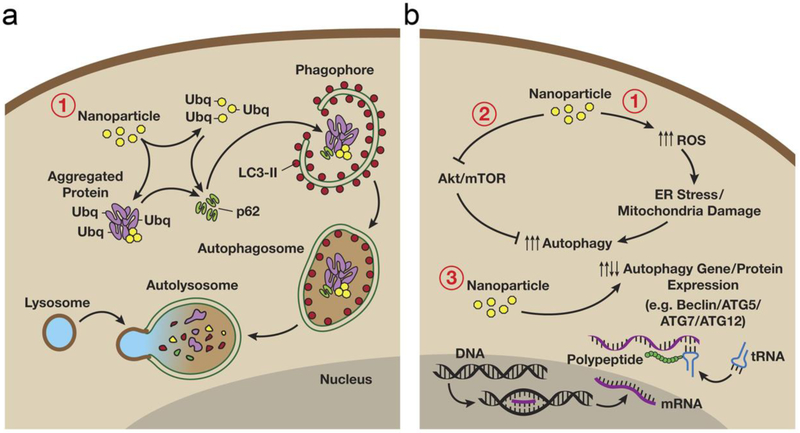

Figure 1.

Nanoparticle-mediated autophagy. (a) Autophagy involves the sequestration and subsequent degradation of nanomaterials. After entrance into the cytoplasm, nanomaterials may be sequestered and deposited within autophagosomes, and fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes will form autolysosomes, which will result in the breakdown and degradation of encapsulated foreign or aberrant nanomaterials. (b) Nanomaterials may also induce autophagy through upregulating oxidative stress and/or affecting the intracellular signaling pathways (e.g., Akt-mTOR signaling pathway) which may regulate the expression of genes/proteins necessary for autophagosome formation. Figure adapted with permission from.[88] Copyright © 2012 BioMed Central Ltd.

4. Leveraging Nanocarrier-mediated Autophagy for Cancer Therapy

Although a doubled-edged sword, autophagy is probably a pro-survival pathway once the tumor is established.[89] inhibiting autophagy flux thus creates a potential opportunity for developing therapeutic strategies. As will be discussed below, a great number of nanomaterials have been employed to modulate autophagy for cancer therapy.

4.1. Liposomes

Liposomes are biocompatible and biodegradable phospholipid vesicles composed of single or multiple concentric lipid bilayers enclosing aqueous spaces. Liposomes have been used to encapsulate and deliver small hydrophobic or hydrophilic drugs.[90] Liposomes can be cleared from the circulation by interacting with phagocytic cells in mononuclear phagocyte system and can be decorated with hydrophilic polymers, such as polyethylene glycol (PEG), to enhance the in vivo circulation time.[91] Several liposomal drugs have been approved by FDA, including Doxil®/Caelyx® for several malignancies, Myocet® for metastatic breast cancer, DaunoXome® for Karposi’s sarcoma, Marqibo® for acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Onivyde® for pancreatic cancer, and many others are in clinical development.[18, 92] As such, liposomes could also serve as a platform for delivering drugs to manipulate autophagy activity in cancers.

Lipodox® (doxorubicin hydrochloride liposome) is similar to Doxil® and has been used to treat cancers when a shortage of Doxil® occurs in the United States.[93] Lipodox, rather than doxorubicin, could inhibit the activity of P-glycoprotein (Pgp), a drug efflux pump, and reverse drug resistance of human colon cancer cells.[94] Wang et al. modified Lipodox with apolipoprotein A1 (apoA1) to mediate the internalization of the liposomes and loaded the liposomal formulation with autophagy inhibitors.[95] The authors found that Lipodox- and apo-Lipodox treatment of doxorubicin-resistant KBV cells induced autophagy as manifested by the accumulation of double-layered autophagosomes and increased conversion of LC-3-I into LC-3-N. Therefore, the authors tested a combination of apo-Lipodox with two autophagy inhibitors (LY294002 and CQ) and found that inhibition of autophagy enhanced the cytotoxicity of apo-Lipodox and reversed drug resistance.[95]

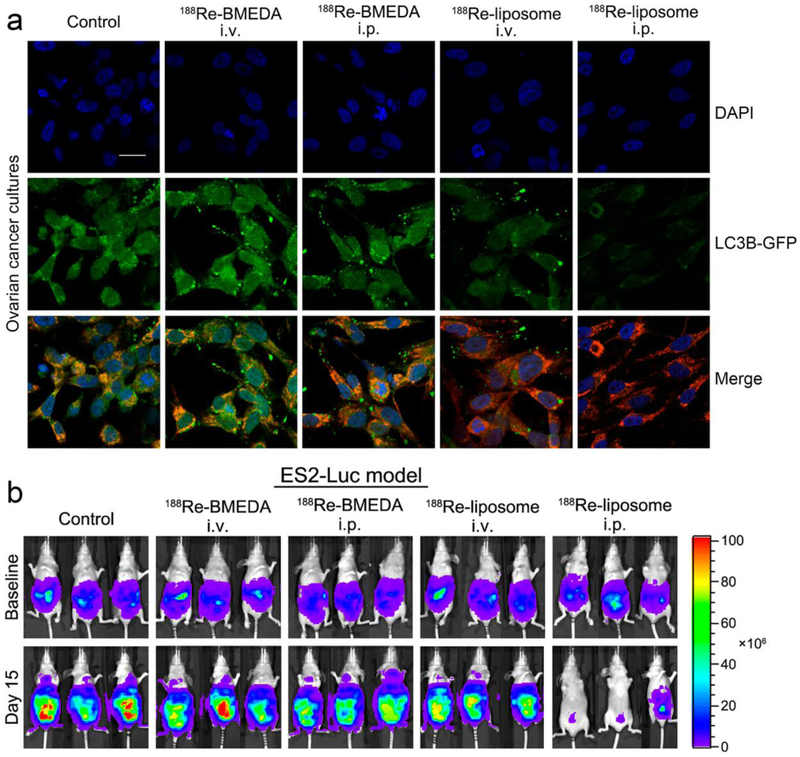

Chen et al. radiolabeled PEGylated liposome with 188Re, which is an attractive theranostic radionuclide with a short physical half-life of 16.9 h and reported that intravenous administration of 188Re-liposome suppressed tumor progression in the lung metastatic colorectal cancer models.[96] The therapeutic effect of 188Re-labeled PEGylated liposome as a monotherapy was further validated in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) model,[97] and synergistic effect of 188Re-PEGylated liposome and sorafenib (an oral multi-kinase inhibitor) was observed in colorectal cancer liver metastasis model.[98] More recently, Chang et al. reported that 188Re-liposome, rather than the free drug 188Re-BMEDA, inhibited autophagy and further led to a significant increase in tumor inhibition in two preclinical ovarian cancer models (Figure 2).[99] More importantly, 188Re-liposome treatment successfully overcame drug resistance and extended survival for two patients with recurrent ovarian cancer.[99]

Figure 2.

188Re-liposome inhibited autophagy in the tumor microenvironment and significantly suppressed tumor growth in ovarian cancer models. (a) The 188Re-Liposome treated ES2 cells (poorly differentiated ovarian clear cell carcinoma cells) were grown on glass coverslips and were transfected with LC3B-GFP vectors. Treatment with 188Re-liposome in ovarian cancer models downregulated the expression of LC3B, whereas treatment with 188Re-BMEDA did not. (b) Intraperitoneal delivery of 188Re-liposome demonstrated significant tumor killing effects in the ES2-Luc ovarian cancer model, where the tumor burden was monitored by bioluminescence imaging. Scale bar: 20 μm. Figure adapted with permission from.[99] Copyright © 2017 MDPI AG.

More recently, dual-functional drug liposome, which refers to drug-containing liposomes that possess a dual-function of providing the basic efficacy of the drug and the extended effect of the drug carrier, has emerged as a promising drug delivery system. These NPs have been successfully used to overcome MDR of chemotherapeutic drugs.[100, 101] Although CQ inhibits autophagy and can sensitize some cancer cells to chemotherapy, the acidic tumor microenvironment may inhibit the penetration of CQ into the cytoplasm, resulting in reduced cellular uptake and therefore limited efficiency of autophagy inhibition.[102] Wang et al. developed a pH-sensitive and integrin αvβ3 targeting liposomes (denoted as Lip-TR) and then loaded the Lip-TR NPs with HCQ using a transmembrane pH-gradient method.[103] The size of the synthesized HCQ/Lip-TR particles was 121.89 ± 1.59 nm at pH 7.4 and reduced to 118.46 ±1.64 nm at pH 6.5. In vitro studies showed the uptake of HCQ/Lip-TR was much higher than that of HCQ/Lip in αvβ3 positive melanoma cells at pH 6.5. Further in vivo studies demonstrated that increased HCQ was delivered into tumors by HCQ/Lip-TR when compared to other formulation (i.e., HCQ/Lip) or free HCQ, which was further associated with smaller tumor weight and more profound autophagy inhibition.[103]

Both preclinical and clinical studies have shown that combination therapy utilizing CQ and vemurafenib (a BrafV600E specific inhibitor) could circumvent multiple mechanisms of vemurafenib resistance and was effective for patients with vemurafenib-resistant brain tumors.[7, 8] In a clinical trial, Rosenfeld et al. reported that autophagy inhibition using HCQ was achievable but required a high dose of HCQ (800 mg of HCQ per day) and had dose-limiting toxicities.[104] Therefore, less toxic compounds inhibiting autophagy or more effective drug delivery strategies are needed for glioma patients. Liu et al. modified liposomes using several αvβ3 and neuropilin-1 receptor dual-targeting peptides (RRRRRRRRdGR, R8dGR; RRRRRRdGR, R6dGR; lower case letter represents D-amino acid residue). The liposomes, conjugated with the cell penetrating peptides, were then loaded with PTX and/or ICG to form their liposomal drug delivery system. The authors found that this formula effectively treated orthotopic glioma.[105, 106] To enhance the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and precisely deliver autophagy inhibitor to glioma, the R6dGR peptide-modified liposomes were loaded with HCQ and vandetanib (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor). Both in vivo and in vitro studies showed that this therapeutic strategy exhibited a synergistic anti-glioma effect by concomitantly inhibiting autophagy and EGFR/VEGFR signaling pathways.[107]

These studies indicate that smart liposomal delivery systems can be harnessed to efficiently deliver autophagy inhibitors to tumor cells and treat cancers in a more effective way.[108] Of note, several studies have demonstrated that liposomal tumor deposition is highly variable across heterogeneous tumors within an individual or across patients.[109] Radiolabeled drug-loaded liposomes with a PET isotope, such as 64Cu, can be used to noninvasively and quantitatively evaluate the biodistribution and deposition of liposomal drugs among different patients.[110-112] Future studies may further design radiolabeled liposomal therapeutics to facilitate image-guided delivery of autophagy inhibitors.

4.2. Polymeric Nanoparticles

Polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) are classified as either nanospheres or nanocapsules. Nanospheres are polymers of the solid matrix, where drugs can be adsorbed on the surface or trapped within the sphere center. Nanocapsules are ideal drug reservoirs in which pharmaceutical compounds can be retained in either an aqueous or a non-aqueous liquid core that is entrapped in a polymeric shell.[113] Of various synthetic polymers, poly (lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) and polylactide (PLA) are FDA approved biodegradable polymers, and have been widely used as biomaterials for synthesizing NPs with sustained, controlled and targeted drug delivery.[114]

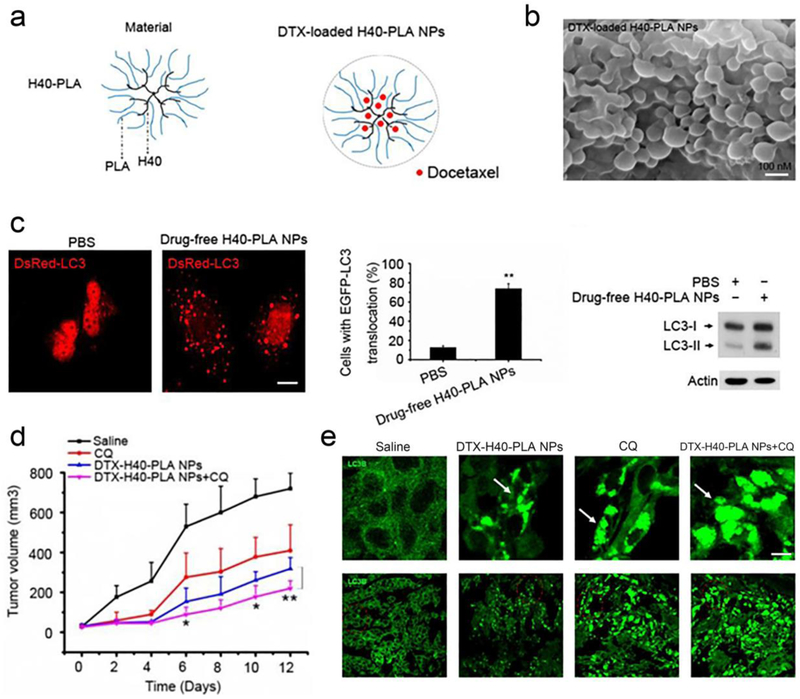

Although most PLGA-based NPs are swallowed by cells through endocytosis, autophagy may also sequester and degrade them.[115] To investigate whether administration of PLGA-based NPs would induce autophagy in cancer cells, Zhang et al. synthesized six kinds of PLGA-based NPs using different surface engineering strategies and investigated their different autophagy-triggering capacities in MCF-7 cells. The authors found that all PLGA-based NPs could induce the formation of autophagosomes. However, PEG and D-a-tocopheryl polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate (TPGS) modified PLGA NPs had increased autophagy induction ability. Administration of docetaxel (DTX)-loaded PLGA NPs with autophagy inhibitors (i.e., 3-methyladenine (3-MA) and CQ) showed more profound inhibition of tumor growth in MCF-7 tumor-bearing mice.[116] Similar results were observed in DTX-loaded H40-PLA NPs, where DTX-H40-PLA NPs induced autophagy both in vitro and in vivo. The addition of CQ to DTX-H40-PLA NPs blocked autophagy (substantially increased autophagosomes within tumor tissues) and impressively inhibited tumor growth (Figure 3).[117] In mouse colon cancer cells, lipid-coated PLGA NPs loaded with mRIP3-plasmid DNA and CQ also showed effective tumor-inhibiting efficacy.[118]

Figure 3.

Chloroquine (CQ) enhanced the therapeutic efficacy of dendritic DTX-H40-PLA NPs in breast cancer models. (a) Schema of preparation of DTX-H40-PLA NPs. (b) Field emission scanning electron microscopy imaging of the DTX-H40-PLA NPs. (c) H40-PLA NPs induced autophagy in MCF-7 cells, as revealed by the confocal microscopic imaging, and quantification of DsRed-LC3 transfected cells by western blotting of LC3I/II protein levels. Scale bar represents 10 μm. (d) Inhibition of autophagy using CQ enhanced the tumor-suppressing effect of DTX-H40-PLA NPs in MCF-7 breast cancer models (n=5 for each treatment group). * represents P<0.05 and ** represent P<0.01. (e) Assessment of autophagy activity in tumor tissues further confirmed profound autophagy inhibition in mice treated with a combination of DTX-H40-PLA NPs and CQ. Autophagosomes were indicated by the arrows on the enlarged fluorescent images of the below images. Scale bar represents 10 μm. Figure adapted with permission from.[117] Copyright © 2014 Ivyspring international publisher.

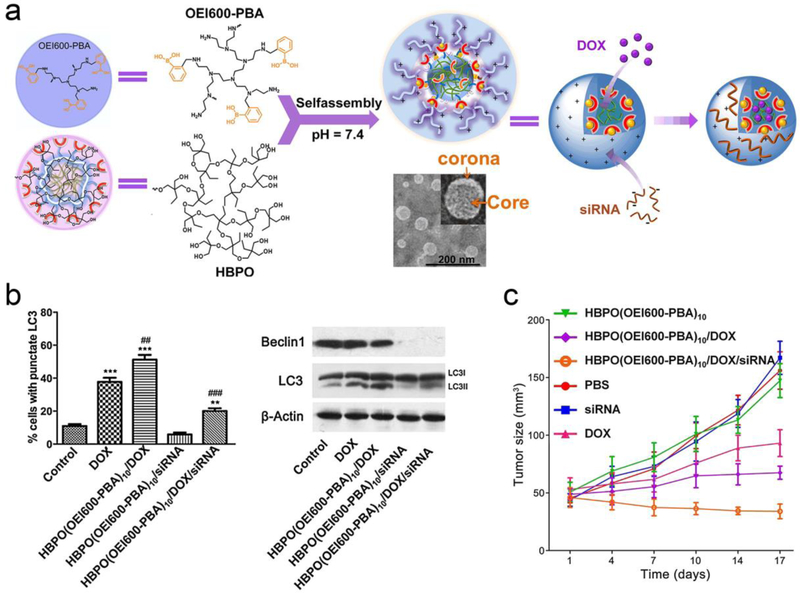

Polymeric vehicles have been extensively used for delivering siRNA, drug therapeutics, or for co-delivery of drugs and siRNA. From a clinical perspective, flexible and adjustable nanoplatforms that can be used to deliver siRNA/drug in a controlled manner is highly needed, particularly for the controlled co-delivery of siRNA and a drug.[119] As an example, Jia et al. reported a flexible nanoplatform derived from the pH-dependent assembly of two hyperbranched polymers (phenylboronic acid-tethered hyperbranched oligoethylenimine, OEI600-PBA; 1,3-diol-rich hyperbranched polyglycerol, HBPO). The inner core of the HBPO aggregates loaded DOX through hydrophobic interaction and the surface clustered cationic OEI600-PBA units allowed conjugation of Beclin1 siRNA. Upon cellular endocytosis and degradation, the formula liberated siRNA/drug payloads and exerted its synergistic anticancer effects (Figure 4).[120] Under hypoxic conditions, autophagy contributes to cell survival by providing a nutritional source for tumor cells.[121, 122] Guan et al. employed long-circulating and cationic-interior liposomes to co-deliver GAPDH-siRNA and PTX into hypoxic tumor cells and found that incubation of HeLa cells with siRNA-PTX liposomes could significantly suppress autophagy by reducing the expression of Atg-5 and Atg-12 and overcome PTX resistance.[123]

Figure 4.

Hyperbranched polymers-mediated delivery of Beclin1 siRNA and antitumor DOX inhibited drug-induced autophagy and thereby suppressed tumor growth in cervical cancer models. (a) The schematic illustration of the assembly of OEI600-PBA and HBPO and the corresponding TEM image of the core-corona nanocarrier. (b) Quantitative PCR and western blotting analyses of LC3 level in HeLa cells showed that DOX treatment led to enhancement of cellular autophagy. In comparison, delivery of Beclin1 siRNA by the nanocarriers effectively inhibited the autophagy activation induced by DOX. **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 versus normal control, ##p < 0.01 and ###p < 0.001 versus DOX-treated group. (c) In tumor-bearing nude mice, DOX/siRNA/(OEI600-PBA)10 outperformed other treatment formulations and showed the most obvious antitumor effect (n=5 for each treatment group). Figure adapted with permission from.[120] Copyright © 2015 Elsevier Ltd.

4.3. Gold nanoparticles

Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) possess unique properties for biomedical applications, such as good biocompatibility, X-ray radiation absorption ability, photo-thermal conversion properties, etc.[124] As AuNPs are being widely utilized in medical imaging and phototherapy due to aforementioned properties, several major challenges (e.g., stability in the blood circulation, distribution in major organs, tumor-targeting ability, activation in response to the tumor microenvironment) need to be thoroughly addressed before clinical translation.[125]

A majority of AuNPs can interfere with autophagy and lysosomal dysfunction.[88] In normal rat kidney cells, AuNPs could block, rather than induce autophagy flux by accumulating in lysosomes and impeding their degradation capacity.[68] Moreover, AuNPs can sensitize NSCLC cells to the tumor necrosis factor related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), and the combination of TRAIL and AuNPs was more effective in treating NSCLC partially through AuNPs-induced autophagy.[126] Interestingly, different surface-engineering strategies, such as chiral polymer coating[127] or antibody-conjugation[128, 129] have been used to selectively induce autophagy and to develop targeted AuNPs therapeutics. Several studies have demonstrated that core-shell NPs with an iron core and a gold shell (Fe@Au) deplete mitochondrial membrane-potential in cancer cells but not in normal healthy cells. These core-shell Fe@Au NPs could further induce autophagic cell death.[80]

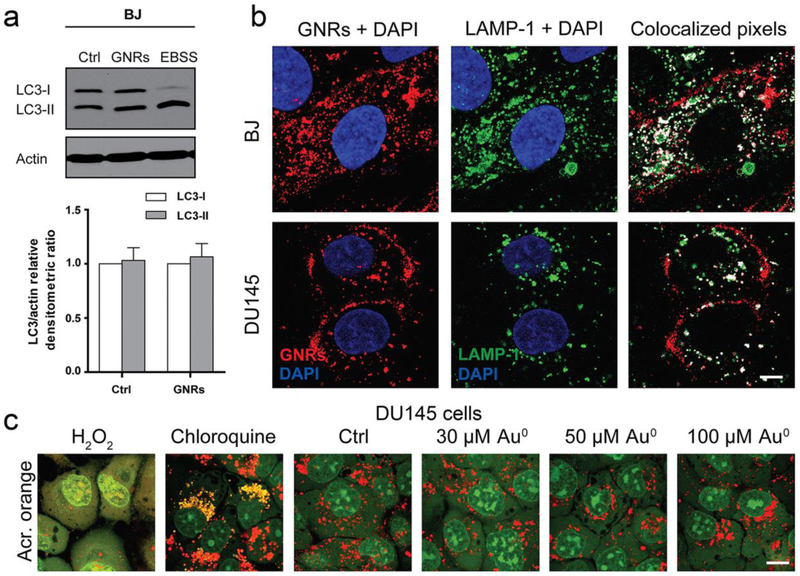

These results together indicate that AuNPs could either block or induce autophagy in a context-dependent manner. In contrast with these results, Zarska et al. demonstrated that gold nanorods were unable to induce intracellular activation of autophagy or to trigger lysosomal stress even after long-term retention inside the cancer cells (Figure 5).[130] Given the high complexity of autophagy, it is important to recognize that reliable methods should be used to discriminate between enhanced autophagy (enhanced cargo degradation) and inhibition of autophagosomal-lysosomal fusion (increased autophagosome accumulation but decreased cargo degradation).[131]

Figure 5.

Gold nanorods (GNRs) did not induce autophagy. (a) Incubation of normal human foreskin BJ fibroblasts with 50 μM of GNRs for 24 h did not induce autophagy. The serum-starved sample (EBSS) was used as a positive control. (b) Confocal images showed colocalization of GNRs with lysosomal marker LAMP-1 in both BJ and DU145 cells. Scale bar represents 10 μm. (c) DU145 cells were treated with 30-100 μM of GNRs for 24 h and then stained using acridine orange, a sensitive marker of lysosome intactness. While the lysosomal destabilizer (hydrogen peroxide, H2O2) induced loss of lysosomal red and increase of the cytoplasmic acridine orange in DU145 cells, GNRs did not inflict permeabilization of the lysosomes in DU145 cells. Scale bar represents 10 μm. Figure adapted with permission from.[130] Copyright © 2018 Elsevier Ltd.

4.4. Silver nanoparticles

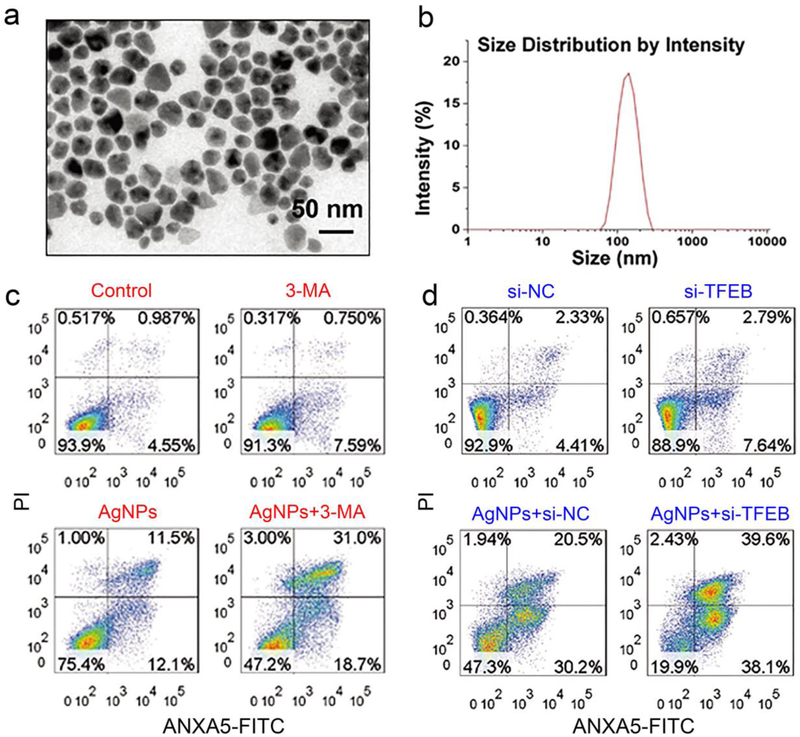

As one of the most commonly used nanomaterials for preclinical cancer diagnosis and therapy, it has been reported that silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are able to induce cytoprotective autophagy.[70, 132-134] Inhibition of autophagy using either small molecules (wortmannin) or knockdown of ATG5 protein enhanced the cytotoxicity of AgNPs in HeLa cells. Additionally, synergistic antitumor effects of AgNPs and autophagy inhibition was further validated in B16 mouse melanoma models.[70] in elucidating underlying molecular mechanisms accounting for AgNPs-induced autophagy, Lin et al. found that AgNPs could induce the translocation of transcription factor EB (TFEB) to nuclei in HeLa cells, which further led to the expression of autophagy-regulating genes.[71] Furthermore, inhibiting autophagy using autophagy inhibitor 3-MA or knocking down of TFEB attenuated the autophagy activity and enhanced the cell killing effect of AgNPs in HeLa cells (Figure 6).[71] Since AgNPs can sensitize glioma cells to radiotherapy,[132, 134, 135] the combination of AgNPs and ionizing radiation could increase the levels of autophagy.[135] Therefore, pharmacological inhibition of autophagy may further enhance the therapeutic effect of radiation therapy and AgNPs in gliomas.

Figure 6.

Inhibition of autophagy enhanced the cytotoxicity of silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) in HeLa cells. (a) TEM image of Ag NPs. (b) Size distribution of Ag NPs measured using dynamic light scattering. (c) Flow cytometry assessment of apoptosis using annexin A5-FITC (ANXA5-FITC)/propidium iodide (PI) showed extensive late-stage apoptosis of HeLa cells treated with Ag NPs and autophagy inhibitor 3-MA. (d) Reducing TFEB protein level by TFEB-specific siRNA also enhanced the cancer cell killing effect of Ag NPs. Figure adapted with permission from.[71] Copyright © 2018 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

4.5. Core-shell nanocarriers

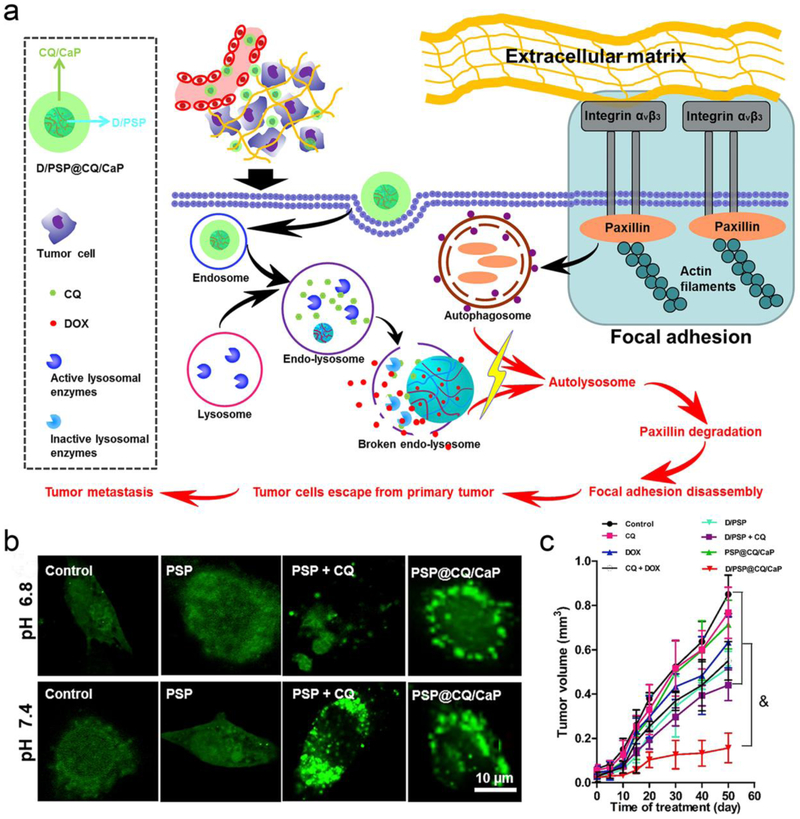

Core-shell nanocarriers might more efficiently extravasate from leaky tumor vasculatures and more readily diffuse into the tumor microenvironment.[136] To this end, Wang et al. developed core-shell nanocarriers, where a pH-triggered core (denoted as “D/PSP) was used to deliver DOX and a matrix metallopeptidase 2 (MMP2) degradable gelatin shell was employed to encapsulate autophagy inhibitor 3-MA.[137] In vivo studies indicated that this formula possessed high accumulation and retention within B16F10 tumors and more effectively inhibited tumor growth by delivering more DOX and 3-MA to the tumor sites.[137] Based on this previous work and the pH-sensitivity of phosphate nanoparticles (CaP),[138] the same team recently modified the formulation (named as “D/PSP@CQ/CaP”) by precipitating chloroquine-calcium phosphate coprecipitate (CQ/CaP) onto the surface of D/PSP.[139] D/PSP@CQ/CaP significantly inhibited the growth of primary breast cancer and also showed obvious anti-metastasis potential, which was partially related to increased expression of paxillin in addition to enhanced autophagy inhibition (Figure 7).[139] These studies together indicate that core-shell nanocarriers could be used to more precisely and efficiently deliver autophagy inhibitors.

Figure 7.

Synergistic anti-tumor and anti-metastasis effect of D/PSP@CQ/CaP NPs in 4T1 murine breast cancer models. (a) Schema illustrating mechanisms of D/PSP@CQ/CaP NPs in suppressing breast cancer in an autophagy-dependent manner. (b) Efficient autophagy inhibition by CQ/CaP shell in 4T1 breast cancer cells as revealed by fluorescence imaging. (c) Treatment of orthotopic 4T1 tumors by D/PSP@CQ/CaP inhibited the tumor growth and prolonged the median survival of mice (n=15 for each treatment group). & represents p < 0.01. Figure adapted with permission from.[139] Copyright © 2017 Elsevier Ltd.

4.6. Iron oxide nanoparticles

In the past decade, iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) have been widely used in the biomedical field for drug delivery, magnetic resonance imaging, and cancer theranostics.[57, 140, 141] IONPs of different shapes and surface properties have been used as photothermal agents for cancer ablation.[142, 143] However, the impact of autophagy on the photothermal effects of IONPs was only recently reported. Ren et al. reported that although incubation of MCF-7 cells with IONP could not induce autophagy, IONP-incubated cells with laser exposure displayed apparently higher autophagy activity as evidenced by fluorescent imaging of the GFP-LC3/MCF-7 cells, which was further confirmed by increased LC3-I/II conversion and increased autophagosomes and autophagic vacuoles. Moreover, in vivo studies using breast cancer models demonstrated that inhibition of autophagy using CQ further enhanced IONP-mediated photothermal therapy.[144] Combination therapy consisting of 3-MA and hyperthermia, which was mediated by NO· radical-conjugated Fe3O4 nanoparticles (Fe3O4-NO· NPs), showed significant tumor-suppressing effect and survival-prolonging benefit in cervical cancer models.[145] These results were similar to those observed in poly(dopamine) (PDA) NPs, where autophagy inhibitor CQ also sensitized cancer cells to the photothermal killing effect of PDA-PEG NPs and NIR irradiation.[146, 147]

4.7. Other nanomaterial-mediated regulation of autophagy in cancer therapy

Apart from the above-mentioned nanocarriers that have been used in the biomedical field for cancer therapy, there are several other promising nanomaterials that have emerged as efficient chemical drug carriers.[71, 77, 81,148] It is worth noting, however, some nanoparticles (e.g., selenium NPs) may induce autophagic death of certain cancer cells.[77]

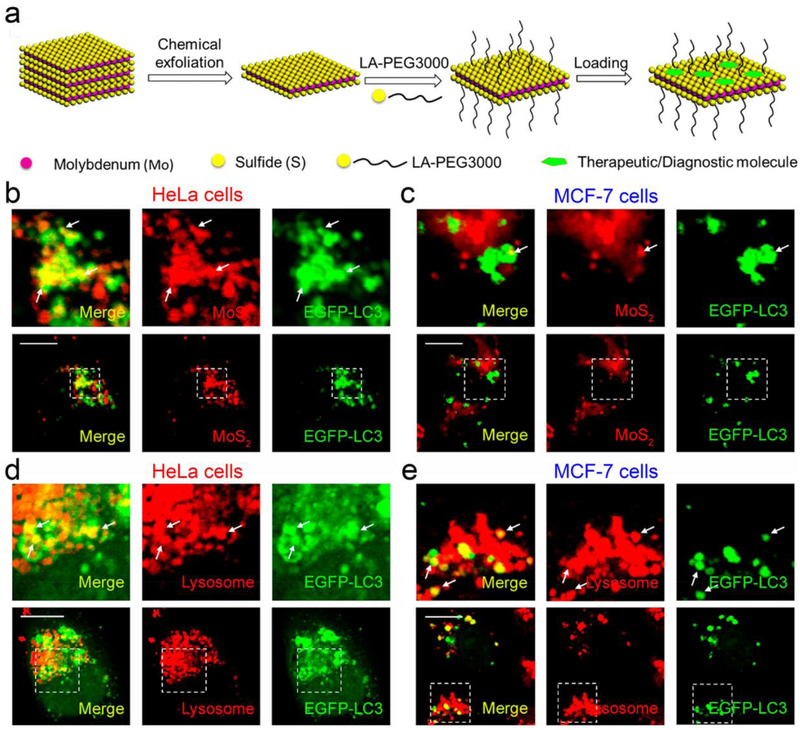

Nanogels are one of such examples, which are mainly based on the formulation of natural polymers such as chitosan and synthetic polymers such as poly(vinyl alcohol), poly(ethylene oxide), poly(ethyleneimine), poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) and poly-N-isopropylacrylamide (PNIPAM). Nanogels represent an optimal choice for delivering both hydrophilic drugs and biomolecular drugs such as proteins and peptides,[149] as well as for biological imaging.[150] In a study investigating the intracellular trafficking network of nanogels, Zhang et al. elucidated that uptake of PNIPAM nanogels by MCF-7 cells could be mediated through multiple pathways including endocytosis, micropinocytosis, endosome pathway, exocytosis pathway as well as the autophagy pathway, which was supported by increased accumulation autophagy markers (LC3II proteins and autophagosomes) and sequestration of Rho-labeled nanogels by EGFP-LC3 positive autophagosomes. The authors found that DOX and DOX-loaded nanogels substantially induced autophagosomes. Therefore, they further developed advanced treatment options and found that DOX-CQ-nanogels, rather than other treatment modalities (drug-free nanogels, DOX, DOX-nanogels, CQ-nanogels) showed substantial suppression of the tumor growth in MCF-7 bearing xenografts.[151] Molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) is a two-dimensional nanosheet (NS) in the transitionmetal dichalcogenide family and has been used for cancer theranostics since 2013.[152-154] A recent study elucidated that MoS2-based NSs were internalized through three different endocytosis pathways and also found that autophagy was involved in the intracellular fate of these NSs. Following incubation of HeLa and MCF-7 with fluorescent nanosheets, EGFP-LC3-positive autophagosomes formed in both cell lines and then autophagosomes fused with lysosomes, suggesting that autophagy may sequester and degrade the MoS2-NSs to a certain extent. Although in this study the authors did not include an autophagy inhibitor to increase the intracellular accumulation of NSs, the authors used Exo1 to inhibit the exocytosis pathway which resulted in increased exocytosis-mediated secretion of MoS2-based NSs in in vitro cell studies. These results were further confirmed by in vivo studies, where triple-combination therapy strategy using PEGylated MoS2/DOX NSs + NIR + Exo1 showed an enhanced therapeutic effect when compared with other treatment modalities (Figure 8).[155]

Figure 8.

Molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) nanosheets can be internalized within autophagosomes. (a) The depiction of surface-engineering and drug-loading of MoS2 nanosheets. (b) Confocal imaging of EGFP-LC3 transfected HeLa cells showed colocalization of MoS2-based nanosheets and EGFP-LC3-positive autophagosomes. (c) The colocalization of MoS2-based nanosheets and autophagosomes was also observed in MCF-7 cells. Confocal images showed colocalization of lysosomes and EGFP-LC3-positive autophagosomes in HeLa cells (d) and MCF-7 cells (e) incubated with fluorescent MoS2-based nanosheets. Figure adapted with permission from.[155] Copyright © 2018 American Chemical Society.

Over the last six years, lipid calcium phosphate NPs have been increasingly used as theranostic platforms due to their ability to efficiently load radiometals and cytotoxic agents.[156] Asymmetric PEGylated lipid calcium phosphate NPs were first explored for siRNA delivery.[157] Wu et al. co-loaded beclin 1-targeting siRNA and FTY720 (known as fingolimod) into lipid calcium phosphate NPs and found that silencing expression of beclin 1 could suppress FTY720-induced autophagy and increase the cytotoxicity of FTY720 both in the in vitro and in vivo studies.[158] However, Ding et al. developed PTX and temozolomide (TMZ) co-loaded calcium phosphate NPs and reported that treatment of C6 cells with PTX: TMZ NPs induced autophagic cell death. The authors further found that this system inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival of orthotopic glioma tumor-bearing rats more efficaciously when compared with other therapeutic methods (e.g., PTX NPs, TMZ NPs).[159]

5. Future Perspectives

Substantial evidence has implicated the importance of autophagy in regulating the initiation and progression of various cancers.[14, 31] Although a double-edged sword, inhibiting autophagy is still a promising approach for advanced cancers. Multiple ongoing clinical trials are evaluating the therapeutic efficacy of targeting autophagy in cancers.[6, 50] Since most chemotherapeutic drugs,[160] certain monoclonal antibodies,[161] as well as molecularly targeted agents,[7, 8] can induce autophagy and incite drug resistance, inhibition of autophagy activity may enhance the therapeutic efficacy of these agents and overcome the drug resistance. Indeed, multiple clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of autophagy inhibition as either a standalone therapy or in combination with other therapies (i.e., chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and/or molecularly targeted therapy) in patients with several kinds of solid tumors.[6] However, off-target, dose-limiting toxicities associated with CQ and HCQ may limit their clinical applications. Delivering of these clinically available autophagy inhibitors, as well as more potent lysosomal autophagy inhibitors (such as Lys05, DQ661, and VATG-032), in a more efficient manner may maximize the efficacy of autophagy inhibition for cancer therapy.

To fully realize the potential of nanomaterials in medical applications, it is essential to have a comprehensive understanding of their in vivo fate (i.e., biodistribution profiles of nanocarriers, interactions with single cells and tissues, clearance, long-term fate, and long-term toxicity).[17, 55, 162] one of the possible hurdles in assessing the aforementioned in vivo performance of nanocarriers is lack of reproducible and reliable methods that can be used to track and quantify both the short- and long-term deposition of nanocarriers. To understand the intracellular trafficking of NPs, several inner membrane vesicle systems can be thoroughly investigated using methods such as time-lapse live-cell imaging.[163, 164] Specifically, endocytosis (e.g., clathrin-mediated endocytosis, caveolae-dependent endocytosis, and clathrin/caveolae independent endocytosis) is one of the primary mechanisms for the uptake of NPs upon delivery, which is closely related to the NP’s physiochemical characteristics.[85, 165, 166] To shed light on the role of endocytosis in mediating uptake and subsequent internalization of NPs, both traditional and novel imaging methods (e.g. confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) and TEM) can be applied. Of the imaging approaches, newly-developed super-resolution techniques (e.g. photo-activated localization microscopy (PALM) and stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM)) are able to facilitate the discrimination of NP trafficking with superior spatial and temporal resolution, where previously unattainable information regarding the uptake and the intracellular tracking of NPs can be clearly obtained.[167] For more detailed information, readers are referred to other excellent review articles in this regard.[85, 168] As mentioned previously, uptake of NPs by cells may result in a stress response which further leads to the induction of autophagy. Therefore, the baseline impact of NPs on the activity of autophagy should be explored with a focus on whether the increased accumulation of autophagosomes is induced via lysosomal impairment.[21, 25, 169] In recent years, radionamedicine, which combines the physicochemical properties of nanomaterials and the power of molecular imaging techniques such as PET or SPECT, has emerged as a very promising platform to develop theranostic agents and to assess the in vivo behavior of nanomaterials.[170-172] Future efforts can be devoted to developing nanoparticle-based drug delivery strategies to regulate the activity of autophagy in cancers in an image-guided manner, which will facilitate better assessment of the in vivo biological fate of these intriguing nanocarriers and better monitoring of the therapeutic responses.

Most nanocarriers, if not all, are targeted to the tumor sites by the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, which is heavily affected by the circulation of the nanocarriers and the compromised vasculature. Nanocarriers with active targeting property could be designed by surface engineering the nanocarriers with specific ligands that could bind specific antigens on the target cells.[173] Of the various surface engineering strategies, antibody- or antibody fragment-decorated nanocarriers loaded with anticancer drugs/modulators of autophagy have shown great potential for future translation.[174-176] In addition, antibody or antibody fragment-functionalized NPs may have increased engulfing and internalization in targeted cells.[176] Despite liposomal drug formulations have shown great therapeutic advantages over free drugs clinically, accelerated blood clearance of liposomal formulations inevitably occur mainly because of production of anti-PEG IgM.[177] In this context, ligand-directed liposomes can be further formulated to deliver autophagy inhibitors in a context- and receptor-dependent manner.[178] It is important to remember that the majority, if not all, of the clinically approved nanotherapeutics, are simple in structure and compositions, as well as easy to prepare on a large scale for clinical trials and use.[17]

To limit off-target distribution of the autophagy inhibitors to undesired tissues, organ-specific drug delivery system may emerge as a cornerstone for future drug delivery.[179] For instance, a lipid nanoparticle-based CRISPR/Cas9 system may overcome a number of pitfalls (e.g., off-target events, immune responses, and integration events into the genome) for liver-specific targeting compared to traditional viral delivery systems.[180] By engineering nanocarriers with tris N-galactosamine, a ligand binding to trimeric asialoglycoprotein receptors which are highly abundant on hepatocytes, several other liver-specific drug delivery systems have also been developed.[181, 182] It has long been believed that autophagy is closely related to the initiation and development of liver cancer.[183] Therefore, future studies can further harness these powerful vehicles to deliver regulatory elements of autophagy and to regulate the autophagy activity of liver cancer in a site-specific and organ-specific manner. Efforts may also be dedicated to exploring and designing other reliable ligand-receptor systems which can be used to delivering autophagy inhibitors in an organ-specific manner.

In addition to traditional treatment strategies, therapeutic oligonucleotides are promising approaches for cancer treatment.[184] With the approval of the first antisense oligonucleotide drug and several undergoing siRNA-based clinical trials,[185, 186] remarkable progress for therapeutic oligonucleotides has been achieved in the past few years. RNA-based therapeutics have great potential to target a large part of the currently undruggable proteins.[187] Autophagy inhibitors have shown great promise in overcoming drug resistance in clinical trials,[7, 8] we still do not have highly specific autophagy inhibitors. In theory, gene knockdown/knockout may more specifically and completely inhibit autophagy than pharmacological agents.[25, 188] Various kinds of nanocarriers have also been engineered to enhance the siRNA therapy and reduce side effects.[189] In addition, due to their inherent properties (e.g., biocompatibility, biodegradability, and programmability), DNA nanostructures are being precisely engineered to deliver therapeutic oligonucleotides (such as siRNA, antisense RNA, and CRISPR/Cas9 system).[171, 190] Therefore, nanocarrier-mediated delivery of siRNA or other gene therapeutics may be developed to inhibit autophagic activity for cancer therapy.

As mentioned above, the tumor-targeting efficiency of most of the nanocarriers depends largely on the EPR effect[191] and it is estimated that less than 1% of the injected NPs reach the tumor site.[192] Several NPs alter the activity of autophagy when administered. Autophagy also plays a key role in deciding the intracellular fate of NPs after endocytosis and therefore influencing their delivery efficiency.[193] In addition, most, if not all, delivered biological agents will be entrapped in endosomes and are degraded by specific enzymes in the lysosome. Several strategies have been proposed to facilitate endosomal escape.[194-196] A classic approach uses the prototypical molecule CQ[19, 163, 197] to diffuse across the cell membrane and into endosomes where it becomes protonated and trapped inside the endosome, leading to increased concentration of CQ in endosomes, lysis of endosomes and then enhanced release of nanocarriers or biological agents from endosomes to the cytoplasm. In addition, CQ could improve the accumulation of NPs by modulating innate immunity,[198] and by normalizing tumor vessels and increasing perfusion.[20] Therefore, co-delivery of autophagy inhibitors and nanocarrier-based therapeutic agents may have synergistic treatment effect by simultaneously inhibiting autophagy and enhancing drug delivery efficiency.

6. Conclusion

Upon continuous optimization and concomitant preclinical/clinical investigations, nanocarrier-mediated regulation of autophagy, especially autophagy inhibition, may serve as an effective treatment option for advanced malignancies.

Acknowledgments

This work was sponsored by the Ph.D. Innovation Fund of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (No. BXJ201736), the Shanghai Key Discipline of Medical Imaging (No. 2017ZZ02005), the University of Wisconsin - Madison, and the National Institutes of Health (P30CA014520), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81371626 and 81630049). Weijun Wei was partially funded by the China Scholarship Council (No. 201706230067).

Biographies

Dr. Wei is a medical doctor majoring in nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. He has been dedicated to developing novel antibody-based probes for noninvasive molecular imaging of cancers and also for treating malignancies. Dr. Wei is also interested in radioiodine treatment of differentiated thyroid cancer, as well as molecularly targeted therapy of radioiodine-refractory thyroid cancers. Dr. Wei has published >20 articles in several world-renowned journals such as Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, Theranostics, etc. Currently, Dr. Wei is a visiting scholar at the University of Wisconsin - Madison under the supervision of Prof. Weibo Cai.

Zack Rosenkrans is currently a Ph.D. student in the Pharmaceutical Sciences program at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, under the supervision of Dr. Weibo Cai. He previously received a B.S. in Chemical Engineering from the University of Kansas in Lawrence, KS. His research is focused on developing nanomaterial-based platforms for image-guided drug delivery and theranostics.

Dr. Cai is a Vilas Distinguished Achievement Professor of Radiology/Medical Physics/Biomedical Engineering/Materials Science & Engineering/Pharmaceutical Sciences at the University of Wisconsin - Madison, USA. He received a PhD degree in Chemistry from UCSD in 2004. Dr. Cai’s research at UW - Madison (http://mi.wisc.edu/) is focused on molecular imaging and nanotechnology. He has authored >270 articles (H-index: 72), edited 3 books, given >240 talks, and received many awards (e.g. Fellow of AIMBE in 2018). Dr. Cai’s trainees at UW - Madison have received >100 awards. Dr. Cai has served on the Editorial Board of >20 journals.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Holohan C, Van Schaeybroeck S, Longley DB, Johnston PG, Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amaravadi RK, Yu D, Lum JJ, Bui T, Christophorou MA, Evan GI, Thomas-Tikhonenko A, Thompson CB, J. Clin. Invest 2007, 117, 326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Briceno E, Reyes S, Sotelo J, Neurosurg. Focus 2003, 14, e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briceno E, Calderon A, Sotelo J, Surg. Neurol 2007, 67, 388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sasaki K, Tsuno NH, Sunami E, Tsurita G, Kawai K, Okaji Y, Nishikawa T, Shuno Y, Hongo K, Hiyoshi M, Kaneko M, Kitayama J, Takahashi K, Nagawa H, BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levy JMM, Towers CG, Thorburn A, Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy JM, Thompson JC, Griesinger AM, Amani V, Donson AM, Birks DK, Morgan MJ, Mirsky DM, Handler MH, Foreman NK, Thorburn A, Cancer Discov. 2014, 4, 773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mulcahy Levy JM, Zahedi S, Griesinger AM, Morin A, Davies KD, Aisner DL, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Fitzwalter BE, Goodall ML, Thorburn J, Amani V, Donson AM, Birks DK, Mirsky DM, Hankinson TC, Handler MH, Green AL, Vibhakar R, Foreman NK, Thorburn A, Elife 2017, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qu X, Yu J, Bhagat G, Furuya N, Hibshoosh H, Troxel A, Rosen J, Eskelinen EL, Mizushima N, Ohsumi Y, Cattoretti G, Levine B, J. Clin. Invest 2003, 112, 1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yue Z, Jin S, Yang C, Levine AJ, Heintz N, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003, 100, 15077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takamura A, Komatsu M, Hara T, Sakamoto A, Kishi C, Waguri S, Eishi Y, Hino O, Tanaka K, Mizushima N, Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inami Y, Waguri S, Sakamoto A, Kouno T, Nakada K, Hino O, Watanabe S, Ando J, Iwadate M, Yamamoto M, Lee MS, Tanaka K, Komatsu M, J. Cell Biol 2011, 193, 275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amaravadi R, Kimmelman AC, White E, Genes Dev. 2016, 30, 1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kimmelman AC, White E, Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dai W, Wang X, Song G, Liu T, He B, Zhang H, Wang X, Zhang Q, Adv. Drug Delivery Rev 2017, 115, 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jabr-Milane LS, van Vlerken LE, Yadav S, Amiji MM, Cancer Treat. Rev 2008, 34, 592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi J, Kantoff PW, Wooster R, Farokhzad OC, Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anselmo AC, Mitragotri S, Bioeng. Transl. Med 2016, 1, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pelt J, Busatto S, Ferrari M, Thompson EA, Mody K, Wolfram J, Pharmacol. Ther 2018, 191, 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maes H, Kuchnio A, Peric A, Moens S, Nys K, De Bock K, Quaegebeur A, Schoors S, Georgiadou M, Wouters J, Vinckier S, Vankelecom H, Garmyn M, Vion AC, Radtke F, Boulanger C, Gerhardt H, Dejana E, Dewerchin M, Ghesquiere B, Annaert W, Agostinis P, Carmeliet P, Cancer Cell 2014, 26, 190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klionsky DJ, Autophagy 2016, 12, 1.26799652 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ktistakis NT, Tooze SA, Trends Cell Biol. 2016, 26, 624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng Y, He D, Yao Z, Klionsky DJ, Cell Res. 2014, 24, 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eskelinen EL, Reggiori F, Baba M, Kovacs AL, Seglen PO, Autophagy 2011, 7, 935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Levine B, Cell 2010, 140, 313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaizuka T, Morishita H, Hama Y, Tsukamoto S, Matsui T, Toyota Y, Kodama A, Ishihara T, Mizushima T, Mizushima N, Mol. Cell 2016, 64, 835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bjorkoy G, Lamark T, Brech A, Outzen H, Perander M, Overvatn A, Stenmark H, Johansen T, J. Cell Biol 2005, 171, 603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eskelinen EL, Autophagy 2008, 4, 257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang FZ, Xing L, Tang ZH, Lu JJ, Cui PF, Qiao JB, Jiang L, Jiang HL, Zong L, Mol. Pharm 2016, 13, 1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Becker AL, Orlotti NI, Folini M, Cavalieri F, Zelikin AN, Johnston AP, Zaffaroni N, Caruso F, ACS Nano 2011, 5, 1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rybstein MD, Bravo-San Pedro JM, Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Nat. Cell Biol 2018, 20, 243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strohecker AM, Guo JY, Karsli-Uzunbas G, Price SM, Chen GJ, Mathew R, McMahon M, White E, Cancer Discov. 2013, 3, 1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lock R, Roy S, Kenific CM, Su JS, Salas E, Ronen SM, Debnath J, Mol. Biol. Cell 2011, 22, 165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo JY, Chen HY, Mathew R, Fan J, Strohecker AM, Karsli-Uzunbas G, Kamphorst JJ, Chen G, Lemons JM, Karantza V, Coller HA, Dipaola RS, Gelinas C, Rabinowitz JD, White E, Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karvela M, Baquero P, Kuntz EM, Mukhopadhyay A, Mitchell R, Allan EK, Chan E, Kranc KR, Calabretta B, Salomoni P, Gottlieb E, Holyoake TL, Helgason GV, Autophagy 2016, 12, 936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang A, Rajeshkumar NV, Wang X, Yabuuchi S, Alexander BM, Chu GC, Von Hoff DD, Maitra A, Kimmelman AC, Cancer Discov. 2014, 4, 905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Egan DF, Chun MG, Vamos M, Zou H, Rong J, Miller CJ, Lou HJ, Raveendra-Panickar D, Yang CC, Sheffler DJ, Teriete P, Asara JM, Turk BE, Cosford ND, Shaw RJ, Mol. Cell 2015, 59, 285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin KR, Celano SL, Solitro AR, Gunaydin H, Scott M, O’Hagan RC, Shumway SD, Fuller P, MacKeigan JP, Science 2018, 8, 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu J, Xia H, Kim M, Xu L, Li Y, Zhang L, Cai Y, Norberg HV, Zhang T, Furuya T, Jin M, Zhu Z, Wang H, Yu J, Li Y, Hao Y, Choi A, Ke H, Ma D, Yuan J, Cell 2011, 147, 223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ronan B, Flamand O, Vescovi L, Dureuil C, Durand L, Fassy F, Bachelot MF, Lamberton A, Mathieu M, Bertrand T, Marquette JP, El-Ahmad Y, Filoche-Romme B, Schio L, Garcia-Echeverria C, Goulaouic H, Pasquier B, Nat. Chem. Biol 2014, 10, 1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robke L, Laraia L, Carnero Corrales MA, Konstantinidis G, Muroi M, Richters A, Winzker M, Engbring T, Tomassi S, Watanabe N, Osada H, Rauh D, Waldmann H, Wu YW, Engel J, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2017, 56, 8153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vezenkov L, Honson NS, Kumar NS, Bosc D, Kovacic S, Nguyen TG, Pfeifer TA, Young RN, Bioorg. Med. Chem 2015, 23, 3237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McAfee Q, Zhang Z, Samanta A, Levi SM, Ma XH, Piao S, Lynch JP, Uehara T, Sepulveda AR, Davis LE, Winkler JD, Amaravadi RK, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012, 109, 8253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fu D, Zhou J, Zhu WS, Manley PW, Wang YK, Hood T, Wylie A, Xie XS, Nat. Chem 2014, 6, 614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Oncotarget 2017, 8, 112168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rebecca VW, Nicastri MC, McLaughlin N, Fennelly C, McAfee Q, Ronghe A, Nofal M, Lim CY, Witze E, Chude CI, Zhang G, Alicea GM, Piao S, Murugan S, Ojha R, Levi SM, Wei Z, Barber-Rotenberg JS, Murphy ME, Mills GB, Lu Y, Rabinowitz J, Marmorstein R, Liu Q, Liu S, Xu X, Herlyn M, Zoncu R, Brady DC, Speicher DW, Winkler JD, Amaravadi RK, Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amaravadi RK, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Yin XM, Weiss WA, Takebe N, Timmer W, DiPaola RS, Lotze MT, White E, Clin. Cancer. Res 2011, 17, 654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barnard RA, Wittenburg LA, Amaravadi RK, Gustafson DL, Thorburn A, Thamm DH, Autophagy 2014, 10, 1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Manic G, Obrist F, Kroemer G, Vitale I, Galluzzi L, Mol. Cell. Oncol 2014, 1, e29911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Onorati AV, Dyczynski M, Ojha R, Amaravadi RK, Cancer 2018, 124, 3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peraro L, Zou Z, Makwana KM, Cummings AE, Ball HL, Yu H, Lin YS, Levine B, Kritzer JA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 7792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Levine B, Packer M, Codogno P, J. Clin. Invest 2015, 125, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chiang WC, Wei Y, Kuo YC, Wei S, Zhou A, Zou Z, Yehl J, Ranaghan MJ, Skepner A, Bittker JA, Perez JR, Posner BA, Levine B, ACS Chem. Biol 2018, 13, 2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Menzies FM, Fleming A, Rubinsztein DC, Nat. Rev. Neurosci 2015, 16, 345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen H, Zhang W, Zhu G, Xie J, Chen X, Nat. Rev. Mater 2017, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Phillips E, Penate-Medina O, Zanzonico PB, Carvajal RD, Mohan P, Ye Y, Humm J, Gonen M, Kalaigian H, Schoder H, Strauss HW, Larson SM, Wiesner U, Bradbury MS, Sci. Transl. Med 2014, 6, 260ra149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xie W, Guo Z, Gao F, Gao Q, Wang D, Liaw BS, Cai Q, Sun X, Wang X, Zhao L, Theranostics 2018, 8, 3284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Coyne DW, Auerbach M, Am. J. Hematol 2010, 85, 311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kanasty R, Dorkin JR, Vegas A, Anderson D, Nat. Mater 2013, 12, 967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Andon FT, Fadeel B, Acc. Chem. Res 2013, 46, 733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mohammadinejad R, Moosavi MA, Tavakol S, Vardar DO, Hosseini A, Rahmati M, Dini L, Hussain S, Mandegary A, Klionsky DJ, Autophagy 2018, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang Y, Sha R, Zhang L, Zhang W, Jin P, Xu W, Ding J, Lin J, Qian J, Yao G, Zhang R, Luo F, Zeng J, Cao J, Wen LP, Nat. Commun 2018, 9, 4236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Man N, Chen Y, Zheng F, Zhou W, Wen LP, Autophagy 2010, 6, 449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang J, Chang D, Yang Y, Zhang X, Tao W, Jiang L, Liang X, Tsai H, Huang L, Mei L, Nanoscale 2017, 9, 3269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang J, Li Y, Duan J, Yang M, Yu Y, Feng L, Yang X, Zhou X, Zhao Z, Sun Z, Autophagy 2018, 14, 1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang J, Yu Y, Lu K, Yang M, Li Y, Zhou X, Sun Z, Int. J. Nanomed 2017, 12, 809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kretowski R, Kusaczuk M, Naumowicz M, Kotynska J, Szynaka B, Cechowska-Pasko M, Nanomaterials (Basel) 2017, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ma X, Wu Y, Jin S, Tian Y, Zhang X, Zhao Y, Yu L, Liang XJ, ACS Nano 2011, 5, 8629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li JJ, Hartono D, Ong CN, Bay BH, Yung LY, Biomaterials 2010, 31, 5996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lin J, Huang Z, Wu H, Zhou W, Jin P, Wei P, Zhang Y, Zheng F, Zhang J, Xu J, Hu Y, Wang Y, Li Y, Gu N, Wen L, Autophagy 2014, 10, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lin J, Liu Y, Wu H, Huang Z, Ma J, Guo C, Gao F, Jin P, Wei P, Zhang Y, Liu L, Zhang R, Qiu L, Gu N, Wen L, Small 2018, 14, e1703711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yu L, Lu Y, Man N, Yu SH, Wen LP, Small 2009, 5, 2784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mari E, Mardente S, Morgante E, Tafani M, Lococo E, Fico F, Valentini F, Zicari A, Int. J. Mol. Sci 2016, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Peynshaert K, Soenen SJ, Manshian BB, Doak SH, Braeckmans K, De Smedt SC, Remaut K, Acta Biomater. 2017, 48, 195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shi M, Cheng L, Zhang Z, Liu Z, Mao X, Int. J. Nanomed 2015, 10, 207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang L, Wang X, Miao Y, Chen Z, Qiang P, Cui L, Jing H, Guo Y, J. Hazard. Mater 2016, 304, 186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Huang G, Liu Z, He L, Luk KH, Cheung ST, Wong KH, Chen T, Biomater. Sci 2018, 6, 2508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Remaut K, Oorschot V, Braeckmans K, Klumperman J, De Smedt SC, J. Control. Release 2014, 195, 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Moosavi MA, Sharifi M, Ghafary SM, Mohammadalipour Z, Khataee A, Rahmati M, Hajjaran S, Los MJ, Klonisch T, Ghavami S, Sci. Rep 2016, 6, 34413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wu YN, Yang LX, Shi XY, Li IC, Biazik JM, Ratinac KR, Chen DH, Thordarson P, Shieh DB, Braet F, Biomaterials 2011, 32, 4565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cui Z, Zhang Y, Xia K, Yan Q, Kong H, Zhang J, Zuo X, Shi J, Wang L, Zhu Y, Fan C, Nat. Commun 2018, 9, 4347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cohignac V, Landry MJ, Ridoux A, Pinault M, Annangi B, Gerdil A, Herlin-Boime N, Mayne M, Haruta M, Codogno P, Boczkowski J, Pairon JC, Lanone S, Autophagy 2018, 14, 1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xue X, Wang LR, Sato Y, Jiang Y, Berg M, Yang DS, Nixon RA, Liang XJ, Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 5110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wu L, Zhang Y, Zhang C, Cui X, Zhai S, Liu Y, Li C, Zhu H, Qu G, Jiang G, Yan B, ACS Nano 2014, 8, 2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Behzadi S, Serpooshan V, Tao W, Hamaly MA, Alkawareek MY, Dreaden EC, Brown D, Alkilany AM, Farokhzad OC, Mahmoudi M, Chem. Soc. Rev 2017, 46, 4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hulea L, Markovic Z, Topisirovic I, Simmet T, Trajkovic V, Trends Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kim YC, Guan KL, J. Clin. Invest. 2015, 125, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Stern ST, Adiseshaiah PP, Crist RM, Part. Fibre Toxicol 2012, 9, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.White E, DiPaola RS, Clin. Cancer. Res 2009, 15, 5308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Torchilin VP, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2005, 4, 145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jokerst JV, Lobovkina T, Zare RN, Gambhir SS, Nanomedicine (Lond) 2011, 6, 715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bobo D, Robinson KJ, Islam J, Thurecht KJ, Corrie SR, Pharm. Res 2016, 33, 2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Smith JA, Costales AB, Jaffari M, Urbauer DL, Frumovitz M, Kutac CK, Tran H, Coleman RL, J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract 2016, 22, 599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Juang V, Lee HP, Lin AM, Lo YL, Int. J. Nanomed 2016, 11, 6047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wang B, Feng D, Han L, Fan J, Zhang X, Wang X, Ye L, Shi X, Feng M, J. Pharm. Sci 2014, 103, 3994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chen LC, Wu YH, Liu IH, Ho CL, Lee WC, Chang CH, Lan KL, Ting G, Lee TW, Shien JH, Nucl. Med. Biol 2012, 39, 35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lin LT, Chang CH, Yu HL, Liu RS, Wang HE, Chiu SJ, Chen FD, Lee TW, Lee YJ, J. Nucl. Med 2014, 55, 1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chang YJ, Hsu WH, Chang CH, Lan KL, Ting G, Lee TW, Mol. Clin. Oncol 2014, 2, 380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chang CM, Lan KL, Huang WS, Lee YJ, Lee TW, Chang CH, Chuang CM, Int. J. Mol. Sci 2017, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mu LM, Ju RJ, Liu R, Bu YZ, Zhang JY, Li XQ, Zeng F, Lu WL, Adv. Drug Delivery Rev 2017, 115, 46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gao M, Xu Y, Qiu L, Int. J. Nanomed 2015, 10, 6615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pellegrini P, Strambi A, Zipoli C, Hagg-Olofsson M, Buoncervello M, Linder S, De Milito A, Autophagy 2014, 10, 562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wang Y, Shi K, Zhang L, Hu G, Wan J, Tang J, Yin S, Duan J, Qin M, Wang N, Xie D, Gao X, Gao H, Zhang Z, He Q, Autophagy 2016, 12, 949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rosenfeld MR, Ye X, Supko JG, Desideri S, Grossman SA, Brem S, Mikkelson T, Wang D, Chang YC, Hu J, McAfee Q, Fisher J, Troxel AB, Piao S, Heitjan DF, Tan KS, Pontiggia L, O’Dwyer PJ, Davis LE, Amaravadi RK, Autophagy 2014, 10, 1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Liu Y, Lu Z, Mei L, Yu Q, Tai X, Wang Y, Shi K, Zhang Z, He Q, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Liu Y, Mei L, Xu C, Yu Q, Shi K, Zhang L, Wang Y, Zhang Q, Gao H, Zhang Z, He Q, Theranostics 2016, 6, 177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wang X, Qiu Y, Yu Q, Li H, Chen X, Li M, Long Y, Liu Y, Lu L, Tang J, Zhang Z, He Q, Int. J. Pharm 2018, 536, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wang Y, Tai X, Zhang L, Liu Y, Gao H, Chen J, Shi K, Zhang Q, Zhang Z, He Q, J. Control. Release 2015, 199, 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Harrington KJ, Mohammadtaghi S, Uster PS, Glass D, Peters AM, Vile RG, Stewart JS, Clin. Cancer. Res 2001, 7, 243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lee H, Shields AF, Siegel BA, Miller KD, Krop I, Ma CX, LoRusso PM, Munster PN, Campbell K, Gaddy DF, Leonard SC, Geretti E, Blocker SJ, Kirpotin DB, Moyo V, Wickham TJ, Hendriks BS, Clin. Cancer. Res 2017, 23, 4190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Blocker SJ, Douglas KA, Polin LA, Lee H, Hendriks BS, Lalo E, Chen W, Shields AF, Theranostics 2017, 7, 4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lee H, Gaddy D, Ventura M, Bernards N, de Souza R, Kirpotin D, Wickham T, Fitzgerald J, Zheng J, Hendriks BS, Theranostics 2018, 8, 2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.El-Say KM, El-Sawy HS, Int. J. Pharm 2017, 528, 675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Danhier F, Ansorena E, Silva JM, Coco R, Le Breton A, Preat V, J. Control. Release 2012, 161, 505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Vasir JK, Labhasetwar V, Adv. Drug Delivery Rev 2007, 59, 718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zhang X, Dong Y, Zeng X, Liang X, Li X, Tao W, Chen H, Jiang Y, Mei L, Feng SS, Biomaterials 2014, 35, 1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zhang X, Yang Y, Liang X, Zeng X, Liu Z, Tao W, Xiao X, Chen H, Huang L, Mei L, Theranostics 2014, 4, 1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hou X, Yang C, Zhang L, Hu T, Sun D, Cao H, Yang F, Guo G, Gong C, Zhang X, Tong A, Li R, Zheng Y, Biomaterials 2017, 124, 195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Saraswathy M, Gong S, Mater. Today 2014, 17, 298. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Jia HZ, Zhang W, Zhu JY, Yang B, Chen S, Chen G, Zhao YF, Feng J, Zhang XZ, J. Control. Release 2015, 216, 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Pouyssegur J, Dayan F, Mazure NM, Nature 2006, 441, 437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Bellot G, Garcia-Medina R, Gounon P, Chiche J, Roux D, Pouyssegur J, Mazure NM, Mol. Cell. Biol 2009, 29, 2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Guan J, Sun J, Sun F, Lou B, Zhang D, Mashayekhi V, Sadeghi N, Storm G, Mastrobattista E, He Z, Nanoscale 2017, 9, 9190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Cai W, Gao T, Hong H, Sun J, Nanotechnol., Sci. Appl 2008, 1, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Guo J, Rahme K, He Y, Li LL, Holmes JD, O’DriscoN CM, Int. J. Nanomed 2017, 12, 6131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ke S, Zhou T, Yang P, Wang Y, Zhang P, Chen K, Ren L, Ye S, Int. J. Nanomed 2017, 12, 2531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 127.Yuan L, Zhang F, Qi X, Yang Y, Yan C, Jiang J, Deng J, J. Nanobiotechnol 2018, 16, 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kubota T, Kuroda S, Kanaya N, Morihiro T, Aoyama K, Kakiuchi Y, Kikuchi S, Nishizaki M, Kagawa S, Tazawa H, Fujiwara T, Nanomedicine 2018, 14, 1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Zhang M, Kim HS, Jin T, Moon WK, J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2017, 170, 58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Zarska M, Sramek M, Novotny F, Havel F, Babelova A, Mrazkova B, Benada O, Reinis M, Stepanek I, Musilek K, Bartek J, Ursinyova M, Novak O, Dzijak R, Kuca K, Proska J, Hodny Z, Biomaterials 2018, 154, 275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Abrams JM, Alnemri ES, Baehrecke EH, Blagosklonny MV, Dawson TM, Dawson VL, El-Deiry WS, Fulda S, Gottlieb E, Green DR, Hengartner MO, Kepp O, Knight RA, Kumar S, Lipton SA, Lu X, Madeo F, Malorni W, Mehlen P, Nunez G, Peter ME, Piacentini M, Rubinsztein DC, Shi Y, Simon HU, Vandenabeele P, White E, Yuan J, Zhivotovsky B, Melino G, Kroemer G, Cell Death Differ. 2012, 19, 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wu H, Lin J, Liu P, Huang Z, Zhao P, Jin H, Wang C, Wen L, Gu N, Biomaterials 2015, 62, 47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Jeong JK, Gurunathan S, Kang MH, Han JW, Das J, Choi YJ, Kwon DN, Cho SG, Park C, Seo HG, Song H, Kim JH, Sci. Rep 2016, 6, 21688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Wu H, Lin J, Liu P, Huang Z, Zhao P, Jin H, Ma J, Wen L, Gu N, Biomaterials 2016, 101, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Liu P, Jin H, Guo Z, Ma J, Zhao J, Li D, Wu H, Gu N, Int. J. Nanomed 2016, 11, 5003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Wong C, Stylianopoulos T, Cui J, Martin J, Chauhan VP, Jiang W, Popovic Z, Jain RK, Bawendi MG, Fukumura D, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108, 2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Wang Y, Qiu Y, Yin S, Zhang L, Shi K, Gao H, Zhang Z, He Q, Autophagy 2017, 13, 359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Weiskopf K, Anderson KL, Ito D, Schnorr PJ, Tomiyasu H, Ring AM, Bloink K, Efe J, Rue S, Lowery D, Barkal A, Prohaska S, McKenna KM, Cornax I, O’Brien TD, O’Sullivan MG, Weissman IL, Modiano JF, Cancer Immunol. Res 2016, 4, 1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Wang Y, Yin S, Zhang L, Shi K, Tang J, Zhang Z, He Q, Biomaterials 2018, 168,1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Mahmoudi M, Hofmann H, Rothen-Rutishauser B, Petri-Fink A, Chem. Rev 2012, 112, 2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Mahmoudi M, Sant S, Wang B, Laurent S, Sen T, Adv. Drug Delivery Rev 2011, 63, 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Chu M, Shao Y, Peng J, Dai X, Li H, Wu Q, Shi D, Biomaterials 2013, 34, 4078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Peng H, Tang J, Zheng R, Guo G, Dong A, Wang Y, Yang W, Adv. Healthcare Mater 2017, 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Ren X, Chen Y, Peng H, Fang X, Zhang X, Chen Q, Wang X, Yang W, Sha X, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 27701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Zhang C, Ren J, He J, Ding Y, Huo D, Hu Y, Biomaterials 2018, 179, 186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Zhou Z, Yan Y, Hu K, Zou Y, Li Y, Ma R, Zhang Q, Cheng Y, Biomaterials 2017, 141, 116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Ding L, Zhu X, Wang Y, Shi B, Ling X, Chen H, Nan W, Barrett A, Guo Z, Tao W, Wu J, Shi X, Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 6790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Zhang Q, Yang W, Man N, Zheng F, Shen Y, Sun K, Li Y, Wen LP, Autophagy 2009, 5, 1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Tahara Y, Akiyoshi K, Adv. Drug Delivery Rev 2015, 95, 65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Lux J, White AG, Chan M, Anderson CJ, Almutairi A, Theranostics 2015, 5, 277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Zhang X, Liang X, Gu J, Chang D, Zhang J, Chen Z, Ye Y, Wang C, Tao W, Zeng X, Liu G, Zhang Y, Mei L, Gu Z, Nanoscale 2017, 9, 150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Zhu C, Zeng Z, Li H, Li F, Fan C, Zhang H, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 5998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Chou SS, Kaehr B, Kim J, Foley BM, De M, Hopkins PE, Huang J, Brinker CJ, Dravid VP, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2013, 52, 4160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Wang S, Chen Y, Li X, Gao W, Zhang L, Liu J, Zheng Y, Chen H, Shi J, Adv. Mater 2015, 27, 7117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Zhu X, Ji X, Kong N, Chen Y, Mahmoudi M, Xu X, Ding L, Tao W, Cai T, Li Y, Gan T, Barrett A, Bharwani Z, Chen H, Farokhzad OC, ACS Nano 2018, 12, 2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Satterlee AB, Huang L, Theranostics 2016, 6, 918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Li J, Yang Y, Huang L, J. Control. Release 2012, 158, 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Wu JY, Wang ZX, Zhang G, Lu X, Qiang GH, Hu W, Ji AL, Wu JH, Jiang CP, Int J Nanomedicine 2018, 13, 1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Ding L, Wang Q, Shen M, Sun Y, Zhang X, Huang C, Chen J, Li R, Duan Y, Autophagy 2017, 13, 1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Sui X, Chen R, Wang Z, Huang Z, Kong N, Zhang M, Han W, Lou F, Yang J, Zhang Q, Wang X, He C, Pan H, Cell Death Dis. 2013, 4, e838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Koustas E, Karamouzis MV, Mihailidou C, Schizas D, Papavassiliou AG, Cancer Lett. 2017, 396, 94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Bourquin J, Milosevic A, Hauser D, Lehner R, Blank F, Petri-Fink A, Rothen-Rutishauser B, Adv. Mater 2018, 30, e1704307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Zhang J, Zhang X, Liu G, Chang D, Liang X, Zhu X, Tao W, Mei L, Theranostics 2016, 6, 2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Vercauteren D, Deschout H, Remaut K, Engbersen JF, Jones AT, Demeester J, De Smedt SC, Braeckmans K, ACS Nano 2011, 5, 7874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Vacha R, Martinez-Veracoechea FJ, Frenkel D, Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 5391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Zhang S, Li J, Lykotrafitis G, Bao G, Suresh S, Adv. Mater 2009, 21, 419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.van der Zwaag D, Vanparijs N, Wijnands S, De Rycke R, De Geest BG, Albertazzi L, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 6391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Albanese A, Tang PS, Chan WC, Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng 2012, 14, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Wang Y, Li Y, Wei F, Duan Y, Trends Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Goel S, England CG, Chen F, Cai W, Adv. Drug Delivery Rev 2017, 113, 157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Jiang D, England CG, Cai W, J. Control. Release 2016, 239, 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]