Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of the current study was to investigate alterations in retinal oxygen delivery, metabolism, and extraction fraction and elucidate their relationships in an experimental model of retinal ischemia.

Methods

We subjected 14 rats to permanent bilateral common carotid artery occlusion using clamp or suture ligation, or they underwent sham procedure. Within 30 minutes of the procedure, phosphorescence lifetime imaging was performed to measure retinal vascular oxygen tension and derive arterial and venous oxygen contents, and arteriovenous oxygen content difference. Fluorescent microsphere and red-free retinal imaging were performed to measure total retinal blood flow. Retinal oxygen delivery rate (DO2), oxygen metabolism rate (MO2), and oxygen extraction fraction (OEF) were calculated.

Results

DO2 and MO2 were lower in ligation and clamp groups compared to the sham group, and also lower in the ligation group compared to the clamp group (P ≤ 0.05). OEF was higher in the ligation group compared to clamp and sham groups (P ≤ 0.03). The relationships of MO2 and OEF with DO2 were mathematically modeled by exponential functions. With moderate DO2 reductions, OEF increased while MO2 minimally decreased. Under severe DO2 reductions, OEF reached a maximum value and subsequently MO2 decreased with DO2.

Conclusions

The findings improve knowledge of mechanisms that can maintain MO2 and may clarify the pathophysiology of retinal ischemic injury.

Keywords: imaging, oxygen metabolism, retinal ischemia

Ocular ischemic syndrome (OIS) is a condition that is caused by occlusion or severe narrowing of the vasculature that supplies the eye, usually the internal and/or common carotid arteries.1 It is characterized by reduced ocular blood flow, loss of visual acuity, orbital pain, and abnormalities in the anterior and posterior segments of the eye.1 Most patients with OIS are also at risk for, or suffer from, cardiovascular and/or cerebrovascular diseases.2–4 Since OIS may appear in the eye before signs and symptoms from the cerebrovascular system,1 patients with OIS should be investigated for the presence of potential cerebral disease.

Experimental permanent bilateral common carotid artery occlusion (BCCAO) is a procedure that causes ischemia by reducing perfusion pressure to tissues that are supplied by the common carotid arteries. It was first used to study cerebral ischemia in rats5 and was later adopted as an experimental model for OIS, showing changes in retinal vessels, capillary network and arterial filling time.6 With prolonged BCCAO of 3 to 300 days duration, retinal anatomical and functional abnormalities, including progressive retinal degeneration and reduced retinal electrophysiological function have been demonstrated.7–13 Additionally, retinal electrophysiologic,13–15 and biochemical11,13–17 changes have been reported within 24 hours of BCCAO.

It is well-established that autoregulatory mechanisms maintain or augment total retinal blood flow (TRBF) during reduced perfusion pressure and light flicker stimulation.18,19 Accordingly, the initial compensatory response to BCCAO is expected to be retinal vasodilation, though not previously reported to our knowledge. Once the vasodilatory capacity is expended, TRBF is reduced thereby affecting the rate of inner retinal oxygen delivery (DO2) which is equal to the product of TRBF and retinal arterial oxygen content. To maintain inner retinal oxygen metabolism (MO2) under a reduced DO2 condition, the tissue must extract more of the supplied oxygen, consequently increasing the oxygen extraction fraction (OEF), defined as the ratio of MO2 to DO2.20 However, there is limited knowledge about changes in TRBF, DO2, MO2, and OEF immediately following BCCAO.

Methods for measurements of retinal MO2 in rats have been reported by an oxygen-sensitive microelectrode technique, visible light optical coherence tomography (OCT) and by combining photoacoustic ophthalmoscopy with spectral domain OCT.21–23 We have previously used phosphorescence lifetime and blood flow imaging for measurements of DO2 and MO2 in rats.24,25 Recently, we reported alterations in DO2, MO2, and OEF in a rat model of graded retinal ischemia induced by ligating the contralateral carotid artery and compressing the ipsilateral carotid artery at graded levels.20 However, in this study, sequential measurements under graded retinal ischemia in the same rat were obtained, thus precluding independent data points that are needed for comparative analysis and mathematical modeling of DO2, MO2, and OEF. The current study was conducted to test two hypotheses: 1) DO2 and MO2 decrease and OEF increases immediately after BCCAO and 2) MO2 is maintained by elevation of OEF during moderate reductions in DO2.

Material and Methods

Animals

All procedures were approved by the University of Southern California Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and adhered to the articles of the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. The study was performed in 14 adult (age: 12–18 weeks) male Long-Evans rats (weight: 300–500 g; Charles River, Wilmington, MA, USA). Rats were acclimated for 3 days before being subjected to random grouping of cohorts. They were kept under environmentally controlled conditions with a 12-hour/12-hour light/dark cycle at 20 to 22°C, were fed a standard rat diet, and had free access to food and water. Prior to performing the experimental procedures, the rats were anesthetized with xylazine (5 mg/kg) and ketamine (90 mg/kg) by intraperitoneal injections. Additional xylazine and ketamine were administered during the procedures to maintain anesthesia. The rats were placed on a heated pad for performing the surgical procedure, and the eyes were kept hydrated by administering saline drops every 10 minutes. Phenylephrine 2.5% (Paragon, Portland, OR, USA) and Tropicamide 1% (Bausch and Lomb, Tampa, FL, USA) were instilled into both eyes for pupillary dilation prior to imaging.

For BCCAO, the common carotid arteries (CAs) were accessed via an anterior midline prelaryngeal incision and were cleanly dissected from the vagus and sympathetic nerves. In 5 rats, 5-0 silk sutures were used to ligate both CAs (ligation group) and in another five rats, atraumatic vascular clamps (jaw dimension of 6 × 1 mm; Fine Science Tools, Braintree, MA, USA) were applied to the CAs (clamp group). Four rats were subjected to exactly the same surgical procedure without occlusions (sham group). The femoral artery was cannulated for administration of 2-μm polystyrene fluorescent microspheres (Life Technologies, Eugene, OR, USA) at a concentration of 107 particles/mL and Pd-Porphine (Frontier Scientific, Logan, UT, USA) at a dosage of 20 mg/kg.

For imaging, the rats were placed on an animal holder equipped with a copper tubing water heater. A glass coverslip with 2.5% hypromellose ophthalmic demulcent solution (HUB Pharmaceuticals, Plymouth, MI, USA) was applied to the cornea to maintain hydration and eliminate its refractive power. Both eyes of each rat were imaged within 30 minutes after BCCAO or sham procedures. Personnel who conducted the experiments were knowledgeable of group allocation during the imaging sessions.

Blood Flow Imaging

A previously described imaging system was used to capture red-free and fluorescent image sequences and measure vessel diameter (D) and venous blood velocity (V), respectively.26 For D measurements, the light illumination of a slit lamp biomicroscope coupled with a green filter (540 ± 5 nm) was used to capture retinal images. Registered mean images were analyzed to determine the vessel boundaries based on the full width at half maximum of intensity profiles perpendicular to the vessel centerline at several consecutive locations along each vessel.26 Measurements in individual vessels were averaged to obtain mean arterial and venous D (DA, Dv) per eye. For V measurements, a 488-nm diode excitation laser and an emission filter (560 ± 60 nm) were used to acquire 520 fluorescence images at 108 Hz. Multiple image sequences were analyzed to determine the displacement of microspheres along each vein segment over time. In each vein, V was calculated by averaging 15 to 30 measurements. Additionally, measurements in individual veins were averaged to calculate a mean venous V (Vv) per eye. Blood velocity was measured in veins which have a smaller variance during the cardiac cycle compared to arteries. Blood flow was calculated as V × π × D2 / 4 for each vein and summed over all the major veins to calculate TRBF.

Oxygen Tension Imaging

Retinal vascular oxygen tension (PO2) imaging was performed using our previously established optical section phosphorescence lifetime imaging system.27,28 A vertical laser line (532 nm) was projected on the retina at an angle and an infrared filter with a cutoff wavelength of 650 nm was placed in the imaging path. The phosphorescence emission from the oxygen-sensitive molecular probe, Pd-Porphine, within all the major retinal arteries and veins was imaged. The phosphorescence lifetime was determined using a frequency-domain approach and converted to PO2 using the Stern-Volmer expression.29,30 Three PO2 measurements were averaged for each retinal major vein and artery.

Oxygen Delivery, Metabolism and Extraction Fraction

The O2 content of the retinal blood vessels was determined as the sum of oxygen bound to hemoglobin and dissolved in blood31: O2 content = SO2 × HgB × C + k × PO2, where SO2 is the oxygen saturation calculated from the rat hemoglobin dissociation curve using measured PO2 and blood pH values from literature, HgB is the rat hemoglobin concentration value (13.8 g/dL),32 C is the maximum oxygen-carrying capacity of hemoglobin (1.39 mL O2/g),33 and k is the solubility of oxygen in blood (0.0032 mL O2/dL mm Hg).34 Measurements of O2 content in individual vessels were averaged to obtain mean arterial and venous O2 contents (O2A, O2V) per eye. O2AV was computed as the difference between O2A and O2V. DO2, MO2, and OEF were calculated as: TRBF × O2A, TRBF × O2AV, and MO2/DO2, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using statistical software (SSPS Statistics, version 24; IBM Armonk, NY, USA). Linear mixed model analysis was performed on oxygen metrics (O2A, O2AV, TRBF, DO2, MO2, OEF) with group (sham, clamp, ligation) and eye (right, left) as fixed factors and animal as a random factor. Estimates (β) for the effect of group were determined. The relationships of MO2 and OEF with DO2 were estimated using the nonlinear least squares curve-fitting tool in MATLAB. Significance was accepted at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

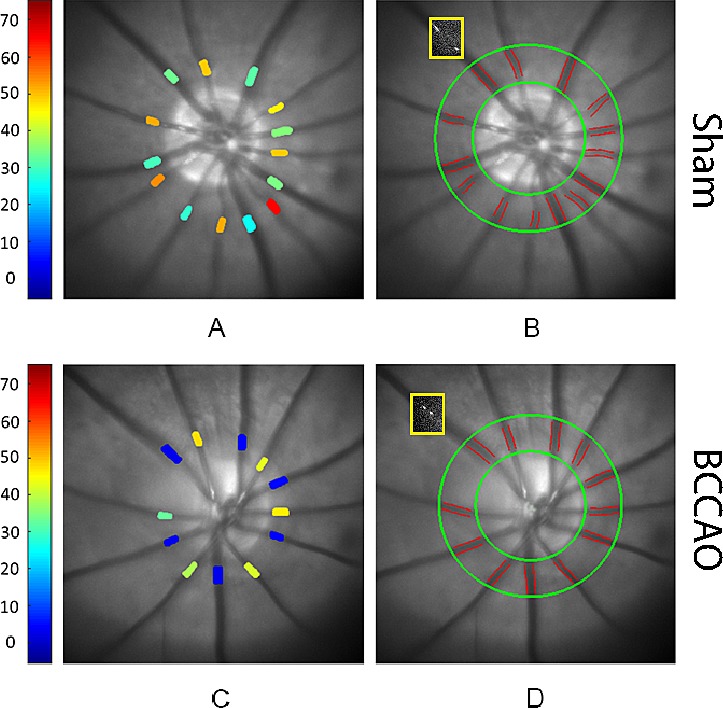

A schematic diagram of the methodology for measurements of retinal vascular PO2 is shown in Figure 1. Retinal arterial and venous PO2 in the rat from the sham group was higher than the rat from the ligation group (Figs. 1A, 1C). Retinal vessel boundaries, as automatically detected, are shown outlined on red-free retinal images in rats from the sham and ligation groups (Figs. 1B, 1D). The position of one intravenous microsphere at two time points is displayed in a yellow box overlaid on the red-free retinal images. Reduced blood velocity can be visualized in the rat from the BCCAO group (Fig. 1D) compared to the rat from the sham group (Fig. 1B) by the shorter distance the microsphere traveled during the same time interval.

Figure 1.

Methodology of oxygen tension and blood flow imaging performed within 30 minutes of sham procedure or bilateral common carotid artery occlusion (BCCAO) by ligation in rats. Retinal vascular oxygen tension measurements are displayed in pseudo color in rats from (A) sham and (C) ligation groups. Color bar shows oxygen tension values in mmHg. Automatically detected retinal vessel boundaries are outlined on red-free retinal images in rats from (B) sham and (D) ligation groups. The position of one intravenous microsphere at two time points is displayed as overlaid on the red-free retinal images (yellow boxes). Note reduced blood velocity can be visualized in the rat from the BCCAO group (D) compared to the rat from the sham group (B) by the shorter distance the microsphere traveled during the same time interval.

The Table lists mean and standard deviation of retinal vascular O2 contents, Vv, and TRBF in the sham, clamp and ligation groups. Compared to the sham group, O2A was lower in both clamp (β = −2.9 mL O2/dL) and ligation (β = −3.8 mL O2/dL) groups (P ≤ 0.01). Similarly, O2V was lower in both clamp (β = −2.7 mL O2/dL) and ligation (β = −5.3 mL O2/dL) groups (P < 0.04). O2V was also lower in the ligation group compared to the clamp group (β = −2.6 mL O2/dL; P < 0.04). O2AV was not significantly different among groups (P > 0.1). There were no statistically significant differences in Dv and DA (P > 0.2). However, Vv was lower in the ligation group compared to the sham (β = −9.0 mm/minute) and clamp (β = −4.2 mm/minute) groups (P ≤ 0.006). Vv was also lower in the clamp group compared to the sham group (β = −4.9 mm/minute; P = 0.003). Likewise, TRBF was lower in the ligation group compared to the sham (β = −6.2 μL/minute) and clamp (β = −3.8 μL/minute) groups (P ≤ 0.02). Occlusion of carotid arteries had a general effect of reducing retinal O2A, O2V, Vv, and TRBF, while Dv and DA were not affected significantly. Additionally, O2AV was not significantly changed with BCCAO due to comparable reductions in O2A and O2V.

Table.

Comparison of Retinal Arterial (O2A), Venous (O2V), Arteriovenous (O2AV) Oxygen Contents, Venous Blood Velocity (Vv), and TRBF

|

Parameter |

Sham (n

= 8) |

Clamp (n

= 10) |

Ligation (n

= 10) |

| O2A, mL O2/dL | 11.2 ± 1.7 | 8.3* ± 2.0 | 7.3* ± 2.1 |

| O2V, mL O2/dL | 5.4 ± 1.3 | 2.7* ± 3.0 | 0.20*† ± 0.13 |

| O2AV, mL O2/dL | 5.7 ± 1.7 | 5.5 ± 2.0 | 7.2 ± 2.1 |

| Vv, mm/min | 12.1 ± 2.0 | 7.2* ± 3.2 | 3.0*† ± 2.0 |

| TRBF, μL/min | 8.5 ± 2.1 | 6.2 ± 3.1 | 2.3*† ± 1.5 |

n indicates the number of eyes; all parameters were measured within 30 minutes of sham procedure or bilateral common carotid artery occlusion by clamp or ligation in rats. Data reported as mean ± standard deviation.

Indicates significantly lower than the sham group.

Indicates significantly lower than the clamp group.

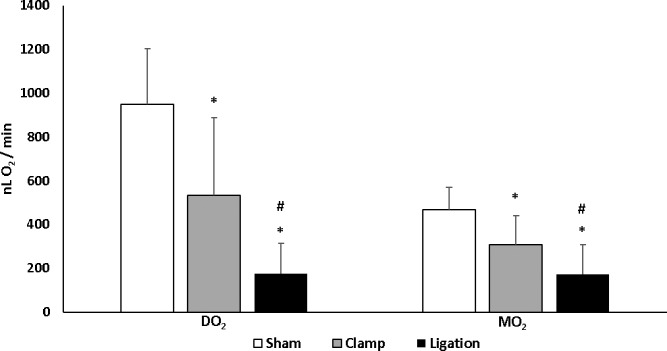

Figure 2 displays mean and standard deviation of DO2 and MO2 in the sham, clamp and ligation groups. DO2 was 948 ± 255 nLO2/minute, 532 ± 356 nLO2/minute, and 175 ± 137 nLO2/minute in the sham, clamp, and ligation groups, respectively. DO2 in the ligation group was lower compared to that in the sham (β = −772 nLO2/minute) and clamp (β = −357 nLO2/minute) groups (P ≤ 0.04). DO2 in the clamp group was lower compared to that in the sham group (β = −415 nLO2/minute) (P = 0.03). MO2 was 466 ± 103 nLO2/minute, 306 ± 135 nLO2/minute, and 171 ± 135 nLO2/minute in the sham, clamp, and ligation groups, respectively. MO2 in the ligation group was lower compared to that in the sham (β = −295 nLO2/minute) and clamp (β = −135 nLO2/minute) groups (P ≤ 0.05). MO2 in the clamp group was lower compared to that in the sham group (β = −160 nLO2/minute; P = 0.03). Immediately after ligation of carotid arteries, DO2 and MO2 were decreased to 18% and 37% of the mean values in the sham group, respectively.

Figure 2.

Comparison of retinal oxygen delivery (DO2) and oxygen metabolism (MO2) measured within 30 minutes of sham procedure or bilateral common carotid artery occlusion by clamp or ligation in rats. Error bars represent standard deviations. Asterisks indicates significantly lower than sham group and # indicates significantly lower than clamp group. Both DO2 and MO2 were reduced immediately following occlusion of carotid arteries by clamp and ligature.

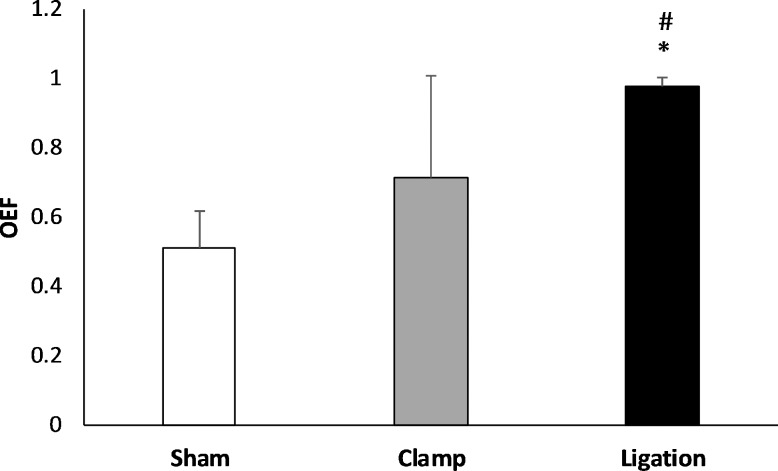

Figure 3 shows the mean and standard deviation of OEF in the sham, clamp, and ligation groups. OEF was 0.51 ± 0.11, 0.71 ± 0.29, and 0.98 ± 0.02 in the sham, clamp, and ligation groups, respectively. OEF was higher in the ligation group compared to that in the sham (β = 0.47) and clamp (β = 0.20) groups (P ≤ 0.03). However, OEF in the clamp group was not significantly different than that in the sham group (P = 0.1). The increase in OEF during carotid artery ligation indicates that up to 98% of the delivered oxygen was metabolized by the retinal tissue.

Figure 3.

Comparison of OEF measured within 30 minutes of sham procedure or bilateral common carotid artery occlusion by clamp or ligation in rats. Error bars indicate standard deviations. Asterisks indicates significantly higher than sham group and # indicates significantly higher than clamp group. OEF was increased immediately following occlusion of carotid arteries by ligation, but not significantly by clamp.

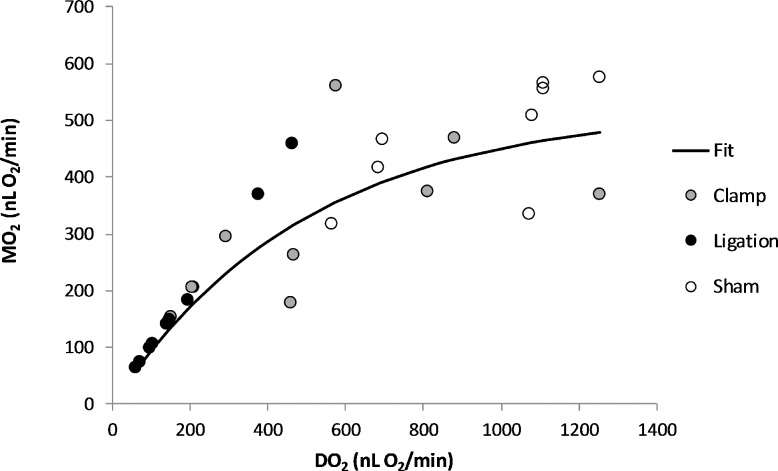

Figure 4 depicts the relationship between MO2 and DO2 based on compiled data from all 3 groups. The data were described by an exponential function: MO2 = 520* (1 − e–0.002*DO2; r2 = 0.81). According to the mathematical model, MO2 reached an asymptotic maximum value of 520 nLO2/minute at high levels of DO2. As DO2 decreased, MO2 initially decreased minimally, but eventually decreased more severely at low levels of DO2. Using the equation derived from the mathematical model, at 50% of the mean MO2 of the sham group (233 nLO2/minute), DO2 was calculated to be 297 nLO2/minute. Based on this relationship, it may be possible to estimate MO2 based on measurements of DO2 and derive threshold values for maintaining MO2.

Figure 4.

The relationship between retinal MO2 and DO2 based on compiled data obtained within 30 minutes of sham procedure or bilateral common carotid artery occlusion in rats. The data were described by an exponential function: MO2 = 520* (1 − e–0.002*DO2; r2= 0.81; n = 28). With DO2 reduction, MO2 initially decreased minimally, but with more severe reductions in DO2, it declined at the same rate as DO2.

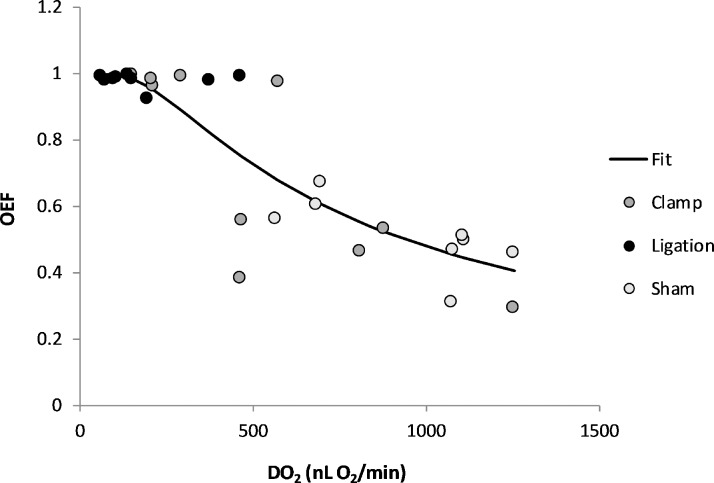

Based on compiled data from all three groups, the relationship between OEF and DO2 is depicted in Figure 5. The data were described by an exponential function: OEF = 0.998* (1 − e–649/DO2); (R2 = 0.77). According to the mathematical model, OEF initially increased as DO2 decreased, but eventually reached an asymptotic maximum value of 1 at low levels of DO2. Using the DO2 value of 297 nLO2/minute, the value at which MO2 was reduced to 50% of the mean in the sham group, OEF was calculated to be 0.89, reflecting a 75% increase with respect to the mean OEF value of 0.51 in the sham group. From this relationship, OEF threshold values for maintaining MO2 may be estimated.

Figure 5.

The relationship between retinal OEF and oxygen delivery (DO2) based on compiled data obtained within 30 minutes of sham procedure or bilateral common carotid artery occlusion in rats. The data were described by an exponential function: OEF = 0.998* (1 − e–649/DO2; r2 = 0.77; n = 28). Initially, OEF increased with decreasing DO2, but with more severe reductions in DO2, it increased more steeply and approached the theoretical maximum value of one, indicating oxygen was completely extracted from the retinal vasculature.

Discussion

Reduced oxygen supply to the retina due to carotid artery occlusion in patients with OIS often leads to vision loss. Therefore, it is important to assess alterations in DO2, MO2 and OEF under the experimental BCCAO condition to gain knowledge that may be relevant to carotid occlusive disease and other retinopathies also characterized by reduced oxygen supply. The current study confirmed the first hypothesis by demonstrating reductions in DO2 and MO2 and an increase in OEF under BCCAO. Furthermore, we were able to confirm the second hypothesis that the retina can accommodate moderate reductions in DO2 and relatively maintain MO2, though there is a decrease in MO2 mediated by severe reductions in DO2.

During BCCAO, TRBF was considerably reduced to 27% of normal blood flow, presumably from the vertebral arteries via the circle of Willis. This observation is consistent with other studies that showed presence of some retinal blood flow during BCCAO.11,13,20 Moreover, other studies have shown collateral circulation in the brain and severe bilateral hemispheric ischemia only by occluding the vertebral arteries in addition to the CAs.35

The reason for the observed reduction in retinal O2A during BCCAO is not entirely clear. However, other studies have shown under conditions of reduced retinal blood flow with BCCAO or reperfusion following occlusion of ophthalmic vessels, retinal O2A was similarly reduced.20,36 The main vascular compensatory response to BCCAO has been shown to be vasodilation and increased blood flow in the vertebral and basilar arteries,37–39 but this does not normalize blood flow to the circle of Willis and brain. Along this relatively long path of slow-moving column of blood from the circle of Willis to the eye, there was likely more time for oxygen to be diffused and consumed by the arterial walls, as well as by the optic nerve and peripapillary retinal tissues central to the measurement site. This may account for the measured decrease in O2A.

The finding of decreased MO2 mediated by a severe reduction in DO2 within 30 minutes after BCCAO is consistent with previous studies that showed the electroretinogram (ERG) b-wave amplitude was reduced within 20 and 45 minutes of BCCAO.13,15 In the current study, MO2 was reduced by 63%, comparable to a previously reported reduction of 46% in the ERG b-wave amplitude.13 Since generation of the ERG b-wave requires energy, its reduction is expected in the presence of reduced MO2. Additionally, Barnett et al.13 did not report any retinal histologic damage after 45 minutes of BCCAO,13 which suggests that DO2 and MO2 alterations after 30 minutes of BCCAO do not cause immediately observable retinal structural damage. Future studies can be directed at whether immediate or sustained alterations in DO2 and MO2 can predict retinal morphological and functional abnormalities observed with prolonged BCCAO.

Initially, the principal compensatory mechanism of the retina to respond to reduced perfusion pressure is to undergo vasodilation, ensuring TRBF and DO2 are maintained and consequently MO2 remains unchanged. In the current study, retinal vasodilation was not observed at the time of the measurements, suggesting that the vasodilatory response for maintaining TRBF was either already expended or not yet activated. Since based on Poiseuille formula, both blood flow and velocity depend on vessel diameter,40,41 the finding of reductions in both TRBF and Vv suggests inadequate vasodilation of retinal arteries and of downstream microvasculature for reducing vascular resistance immediately following BACCAO. Similar to our finding, Riva and coworkers42 found as perfusion pressure was decreased by increasing intraocular pressure in humans that retinal venous diameters near the optic nerve remained unchanged while blood velocity and flow decreased. They also found a simultaneous decrease in vascular resistance confirming the presence of vasodilation in the microvasculature downstream from their measurement site, though not adequate to maintain blood flow and velocity. It is probable that a similar phenomenon was active under BCCAO. Moreover, several studies have reported reductions in blood flow when autoregulatory mechanisms are expended under severe decreased perfusion pressure conditions in humans, monkeys and cats.42–46 Nevertheless, with less severe reductions in perfusion pressure, regulation by both TRBF and Vv is expected to minimize changes in MO2.

In the current study, the use of clamp incompletely occluded the CAs in some cases, thus providing data under varying levels of reduced TRBF. This allowed for mathematical modeling of the relationships of MO2 and OEF with DO2. Under moderate reductions in DO2, a minimum change in MO2 was demonstrated. The relative maintenance of MO2 was mediated by an increase in OEF as long as adequate oxygen was available to be extracted. However, with further reductions in DO2, the venous O2 content became negligible and thereby OEF reached a maximum value of unity, indicating that all of the delivered oxygen was metabolized. Under severe DO2 reduction, OEF was maximized and MO2 became limited by DO2, in agreement with our previous report.20

One advantage of the current study was quantitative measurements of TRBF and DO2. Thus, findings on the effects of ischemia on MO2 and OEF are not limited to the BCCAO model of retinal ischemia and may be applicable to other methods of reducing retinal blood flow to similar levels. Of particular interest is the information we obtained on MO2. Since energy is required for most retinal functions and MO2 is an indicator of retinal energy production, it should closely reflect the injurious impact of retinal ischemia.

Recently methods have become available for measurements of MO2, DO2, and OEF in human subjects.47–50 Thus, evaluation of these parameters may potentially lead to improvements in diagnosis and therapy of human retinal ischemic diseases. For example, thresholds for MO2, DO2, and OEF may be derived and applied to predict prognosis for disease progression or response to treatment for individual patients. Moreover, MO2 may prove to be a valuable quantitative outcome in therapeutic trials that evaluate delivery of oxygen or neuroprotective drugs. Finally, now that it is possible to measure MO2, research can focus on its role in retinal ischemia and other diseases, thereby leading to future advances in new metabolically-based treatments.

The current study had some limitations. First, the study was limited to retinal physiologic measurements and did not investigate corresponding biochemical abnormalities, electrophysiologic dysfunction, or histopathologic changes under BCCAO, which have been previously described in literature. Nevertheless, the finding of reduced MO2 was consistent with previously reduced electrophysiologic responses immediately after BCCAO. Second, the systemic physiologic condition of the rats was not controlled or monitored during imaging, though we expect conditions were similar in sham and BCCAO groups. Third, the findings of the current study may not be generalizable beyond the animal species/strain under investigation. Fourth, the vascular clamp produced variable levels of CA occlusions apparently due to the displacement of the clamp during positioning of the animal for imaging. This, in turn, provided a limited number of data points under each graded level of decreased DO2. Additional data are needed for more robust mathematical modeling of the relationships. Finally, future studies are needed to determine the effect of prolonged TRBF reduction or TRBF recovery on MO2 and OEF.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated decreases in MO2 and DO2 and an increase in OEF immediately after permanent BCCAO. Furthermore, OEF was maximized as MO2 and DO2 were matched during severe ischemia. Additionally, nonlinear mathematical models were proposed for predicting MO2 and OEF based on DO2. The findings improve knowledge of mechanisms that can maintain MO2 and may clarify the pathophysiology of retinal ischemic injury.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Eye Institute (Bethesda, MD, USA) (Grants EY017918 and EY029220) and an unrestricted departmental award from Research to Prevent Blindness (New York, NY, USA).

Disclosure: P. Karamian, None; J. Burford, None; S. Farzad, None; N.P. Blair, None; M. Shahidi, P

References

- 1.Terelak-Borys B, Skonieczna K, Grabska-Liberek I. Ocular ischemic syndrome - a systematic review. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18:RA138–RA144. doi: 10.12659/MSM.883260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sivalingam A, Brown GC, Magargal LE, Menduke H. The ocular ischemic syndrome. II. Mortality and systemic morbidity. Int Ophthalmol. 1989;13:187–191. doi: 10.1007/BF02028208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Persoon S, Klijn CJ, Algra A, Kappelle LJ. Bilateral carotid artery occlusion with transient or moderately disabling ischaemic stroke: clinical features and long-term outcome. J Neurol. 2009;256:1728–1735. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5194-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim YH, Sung MS, Park SW. Clinical features of ocular ischemic syndrome and risk factors for neovascular glaucoma. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2017;31:343–350. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2016.0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eklöf B, Siesjö BK. The effect of bilateral carotid artery ligation upon the blood flow and the energy state of the rat brain. Acta Physiol Scand. 1972;86:155–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1972.tb05322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slakter JS, Spertus AD, Weissman SS, Henkind P. An experimental model of carotid artery occlusive disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984;97:168–172. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davidson CM, Pappas BA, Stevens WD, Fortin T, Bennett SAL. Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion: loss of pupillary reflex, visual impairment and retinal neurodegeneration. Brain Res. 2000;859:96–103. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)01937-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevens WD, Fortin T, Pappas BA. Retinal and optic nerve degeneration after chronic carotid ligation: time course and role of light exposure. Stroke. 2002;33:1107–1112. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000014204.05597.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takamatsu J, Hirano A, Levy D, Henkind P. Experimental bilateral carotid artery occlusion: a study of the optic nerve in the rat. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1984;10:423–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1984.tb00391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo XJ, Tian XS, Ruan Z, et al. Dysregulation of neurotrophic and inflammatory systems accompanied by decreased CREB signaling in ischemic rat retina. Exp Eye Res. 2014;125:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang Y, Fan S, Li J, Wang YL. Bilateral common carotid artery occlusion in the rat as a model of retinal ischaemia. Neuroophthalmology. 2014;38:180–188. doi: 10.3109/01658107.2014.908928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lavinsky D, Arterni NS, Achaval M, Netto CA. Chronic bilateral common carotid artery occlusion: a model for ocular ischemic syndrome in the rat. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244:199–204. doi: 10.1007/s00417-005-0006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnett NL, Osborne NN. Prolonged bilateral carotid artery occlusion induces electrophysiological and immunohistochemical changes to the rat retina without causing histological damage. Exp Eye Res. 1995;61:83–90. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(95)80061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Block F, Sontag KH. Differential effects of transient occlusion of common carotid arteries in normotensive rats on the somatosensory and visual system. Brain Res Bull. 1994;33:589–593. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Block F, Schwarz M, Sontag KH. Retinal ischemia induced by occlusion of both common carotid arteries in rats as demonstrated by electroretinography. Neuroscience Letters. 1992;144:124–126. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90731-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo X, Shen YM, Jiang MN, Lou XF, Shen Y. Ocular blood flow autoregulation mechanisms and methods. J Ophthalmol. 2015;2015:864871. doi: 10.1155/2015/864871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto H, Schmidt-Kastner R, Hamasaki DI, Parel JM. Complex neurodegeneration in retina following moderate ischemia induced by bilateral common carotid artery occlusion in Wistar rats. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:767–779. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kur J, Newman EA, Chan-Ling T. Cellular and physiological mechanisms underlying blood flow regulation in the retina and choroid in health and disease. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2012;31:377–406. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pournaras CJ, Rungger-Brändle E, Riva CE, Hardarson SH, Stefansson E. Regulation of retinal blood flow in health and disease. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2008;27:284–330. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blair NP, Felder AE, Tan MR, Shahidi M. A model for graded retinal ischemia in rats. Trans Vis Sci Tech. 2018;7(3):10. doi: 10.1167/tvst.7.3.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu W, Zhang HF. Noninvasive in vivo imaging of oxygen metabolic rate in the retina. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2014. pp. 3865–3868. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Yi J, Liu W, Chen S, et al. Visible light optical coherence tomography measures retinal oxygen metabolic response to systemic oxygenation. Light Sci Appl. 2015;4:e334. doi: 10.1038/lsa.2015.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cringle SJ, Yu DY, Yu PK, Su EN. Intraretinal oxygen consumption in the rat in vivo. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:1922–1927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wanek J, Teng PY, Blair NP, Shahidi M. Inner retinal oxygen delivery and metabolism in streptozotocin diabetic rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:1588–1593. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wanek J, Teng PY, Blair NP, Shahidi M. Inner retinal oxygen delivery and metabolism under normoxia and hypoxia in rat. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:5012–5019. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-11887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wanek J, Teng PY, Albers J, Blair NP, Shahidi M. Inner retinal metabolic rate of oxygen by oxygen tension and blood flow imaging in rat. Biomed Opt Express. 2011;2:2562–2568. doi: 10.1364/BOE.2.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shahidi M, Shakoor A, Blair NP, Mori M, Shonat RD. A method for chorioretinal oxygen tension measurement. Curr Eye Res. 2006;31:357–366. doi: 10.1080/02713680600599446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shahidi M, Wanek J, Blair NP, Mori M. Three-dimensional mapping of chorioretinal vascular oxygen tension in the rat. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:820–825. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shonat RD, Kight AC. Oxygen tension imaging in the mouse retina. Ann Biomed Eng. 2003;31:1084–1096. doi: 10.1114/1.1603256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lakowicz JR, Szmacinski H, Nowaczyk K, Berndt KW, Johnson M. Fluorescence lifetime imaging. Anal Biochem. 1992;202:316–330. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90112-k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shapiro BA, Peruzzi WT, Kozlowski-Templin R. Clinical Application of Blood Gases. St. Louis, MO: Mosby;; 1994. p. 427. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crystal G. Principles of cardiovascular physiology. Cardiac Anesthesia: Principles and Clinical Practice. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. pp. 37–57.

- 33.West J. Pulmonary Physiology and Pathophysiology: an Integrated, Case-Based Approach 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costanzo L. Physiology 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pulsinelli WA, Brierley JB. A new model of bilateral hemispheric ischemia in the unanesthetized rat. Stroke. 1979;10:267–272. doi: 10.1161/01.str.10.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blair NP, Tan MR, Felder AE, Shahidi M. Retinal oxygen delivery, metabolism and extraction fraction and retinal thickness immediately following an interval of ophthalmic vessel occlusion in rats. Sci Rep. 2019;9:8092. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44250-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fujii K, Heistad DD, Faraci FM. Flow-mediated dilatation of the basilar artery in vivo. Circ Res. 1991;69:697–705. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.3.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoi Y, Gao L, Tremmel M, et al. In vivo assessment of rapid cerebrovascular morphological adaptation following acute blood flow increase. J Neurosurg. 2008;109:1141–1147. doi: 10.3171/JNS.2008.109.12.1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jing Z, Shi C, Zhu L, et al. Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion induces vascular plasticity and hemodynamics but also neuronal degeneration and cognitive impairment. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2015;35:1249–1259. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feke GT, Tagawa H, Deupree DM, Goger DG, Sebag J, Weiter JJ. Blood flow in the normal human retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1989;30:58–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skinner HB. Velocity-diameter relationships of the microcirculation. Med Inform (Lond) 1979;4:243–256. doi: 10.3109/14639237909017762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Riva CE, Grunwald JE, Petrig BL. Autoregulation of human retinal blood flow. An investigation with laser Doppler velocimetry. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1986;27:1706–1712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Geijer C, Bill A. Effects of raised intraocular pressure on retinal, prelaminar, laminar, and retrolaminar optic nerve blood flow in monkeys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1979;18:1030–1042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Riva CE, Cranstoun SD, Petrig BL. Effect of decreased ocular perfusion pressure on blood flow and the flicker-induced flow response in the cat optic nerve head. Microvasc Res. 1996;52:258–269. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1996.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Riva CE, Sinclair SH, Grunwald JE. Autoregulation of retinal circulation in response to decrease of perfusion pressure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1981;21:34–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riva CE, Titze P, Hero M, Petrig BL. Effect of acute decreases of perfusion pressure on choroidal blood flow in humans. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:1752–1760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fondi K, Wozniak PA, Howorka K, et al. Retinal oxygen extraction in individuals with type 1 diabetes with no or mild diabetic retinopathy. Diabetologia. 2017;60:1534–1540. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4309-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Palkovits S, Told R, Schmidl D, et al. Regulation of retinal oxygen metabolism in humans during graded hypoxia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;307:H1412–1418. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00479.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shahidi M, Felder AE, Tan O, Blair NP, Huang D. Retinal oxygen delivery and metabolism in healthy and sickle cell retinopathy subjects. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59:1905–1909. doi: 10.1167/iovs.17-23647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Werkmeister RM, Schmidl D, Aschinger G, et al. Retinal oxygen extraction in humans. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15763. doi: 10.1038/srep15763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]