Abstract

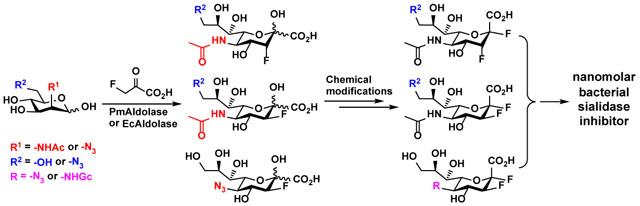

A library of 2(e),3(a/e)-difluorosialic acids and their C-5 and/or C-9 derivatives were chemoenzymatically synthesized. Pasteurella multocida sialic acid aldolase (PmAldolase), but not its Escherichia coli homolog (EcAldolase), was found to catalyze the formation of C5-azido analog of 3-fluoro(equatorial)-sialic acid. In comparison, both PmAldolase and EcAldolase could catalyze the synthesis of 3-fluoro (axial or equatorial)-sialic acids and their C-9 analogs although PmAldolase was generally more efficient. The chemoenzymatically synthesized 3-fluoro (axial or equatorial)-sialic acid analogs were purified and chemically derivatized to form desired difluorosialic acids and derivatives. Inhibition studies against several bacterial sialidases and a recombinant human cytosolic sialidase hNEU2 indicated that sialidase inhibition was affected by the C-3 fluorine stereochemistry and derivatization at C-5 and/or C-9 of the inhibitor. Opposite to that observed for influenza A virus sialidases and hNEU2, compounds with an axial fluorine at C-3 were better inhibitors (up to 100-fold) against bacterial sialidases compared to their 3F-equatorial counterparts. While C-5-modified compounds were less efficient anti-bacterial sialidase inhibitors, 9-N3-modified 2,3-difluoro-Neu5Ac showed increased inhibitory activity against bacterial sialidases. 9-Azido-9-deoxy-2-equatorial-3-axial-difluoro-N-acetylneuraminic acid (2e3aDFNeu5Ac9N3) was identified as an effective inhibitor with a long effective duration selectively against pathogenic bacterial sialidases from Clostridium perfringens (CpNanI) and V. cholerae.

Keywords: Carbohydrate, Difluorosialic acid, Neuraminidase, Sialidase, Sialidase inhibitor

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Sialic acids are a family of negatively charged monosaccharides with a nine-carbon backbone. They play important roles in human homeostasis and pathological processes.1 The level of sialic acid on cell surface is regulated by the functions of sialyltransferases, sialidases, and the availability of sialyltransferase donor substrates cytidine-5’-monophosphate sialic acids (CMP-Sia).1–3 Sialidases or neuraminidases (EC 3.2.1.18) are key enzymes for the catabolism of sialic acid-containing oligosaccharides or glycoconjugates, in which they catalyze the cleavage of terminal sialic acids.2 Sialidases found in bacteria, viruses, fungi, and mammals have differences in their primary sequences, but share a common catalytic domain.4

Bacterial sialidases play diverse roles including a nutritional function for providing bacteria with carbon and energy sources, serving as virulence factors during bacterial pathogenesis, and immunomodulatory effects.5–9 For example, Streptococcus pneumoniae10 and Tannerella forsythia11 produce sialidases which release sialic acids as bacterial carbon and energy sources.12 In addition, Streptococcus pneumoniae sialidase SpNanA is essential for pathogenesis of Streptococcus pneumoniae, which causes respiratory-tract infections, pneumonia, otitis media, bacteremia, sepsis, and meningitis, etc.13 Clostridium perfringens sialidase may facilitate the infection of this Gram-positive pathogenic bacterium which causes histotoxic infections and intestinal diseases.14 Therefore, bacterial sialidases are attractive targets for drug development.

The effort of protein crystal structure-based rational design has successfully identified several sialidase inhibitors as effective anti-influenza A virus therapeutics, including Zanamivir (Relenza, GlaxoSmithKline),15 Oseltamivir (Tamiflu, Gilead/Roche),15,16 Peramivir (Rapivab, BioCryst),16–20 Laninamivir,21 and TCN-032.22,23 Crystal structures of an increasing number of bacterial sialidases are becoming available and an improved understanding of their mechanisms has been achieved, providing a great opportunity for designing inhibitors selectively against bacterial sialidases.24–26 Indeed, sialidase inhibitors have shown to protect mice against bacterial sepsis in an animal model.27

In addition to inhibitors designed based on sialidase transition state analog 2-deoxy-2,3-didehydro-N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac2en or DANA)24,27–29 or sialidase product analog,25,30 difluorosialic acids were developed as a new class of mechanism-based sialidase inhibitors.31–34 The addition of an electronegative fluorine atom as a good leaving group at C-2 of sialic acids was shown to allow the formation of a covalent bond between the sialic acid and the sialidase. Adding another fluorine at C-3 of sialic acid was shown to destabilize the oxocarbenium-like transition state,35,36 slow down the cleavage of the glycosyl-enzyme covalent bond, thus trap the intermediate.31–33,37–39 Indeed, the designed difluoro-compounds were demonstrated to form glycosyl-enzyme intermediates with several parasite trans-sialidases, some bacterial sialidases, and human cytosolic sialidase hNEU2 by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, mass spectrometry (MS), and/or X-ray crystal structures.31–33,38,39 Influenza A virus neuraminidases were shown to follow the same mechanism involving the formation of a glycosyl-enzyme intermediate.34 2(equatorial),3(equatorial)-Difluorosialic acid with a C4-guanidinium group was proven to have superior in vitro anti-influenza A virus efficacy compared to its C4-ammonium or its 2(equatorial),3(axial)-difluorosialic acid counterpart with an inhibition efficacy comparable to that of Zanamivir.34

We showed previously that derivatization of Neu5Ac2en-based sialidase inhibitor at carbon 9 and carbon 5 significantly affected its selectivity against different sialidases.26,40 We aimed to introduce selectivity to 2,3-difluoro sialic acid-based sialidase inhibitors by exploring modifications at C-5 and/or C-9 as well as varying C-3 fluorine stereochemistry (axial or equatorial). As shown below, an effective inhibitor with inhibition values in a low nanomolar range against bacterial sialidases including those from Streptococcus pneumoniae (SpNanA), Clostridium perfringens (CpNanI), and Arthrobacter ureafaciens is identified. The inhibitor also has a long effective duration against pathogenic bacterial sialidases from V. cholerae (with a reactivation half-life of > 24 hours) and Clostridium perfringens (CpNanI) (with a reactivation half-life of > 60 hours). The compound can be explored to further improve its property for potential application as useful chemical glycobiological tools and/or strategies to combat bacterial infection or host immune-regulation.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

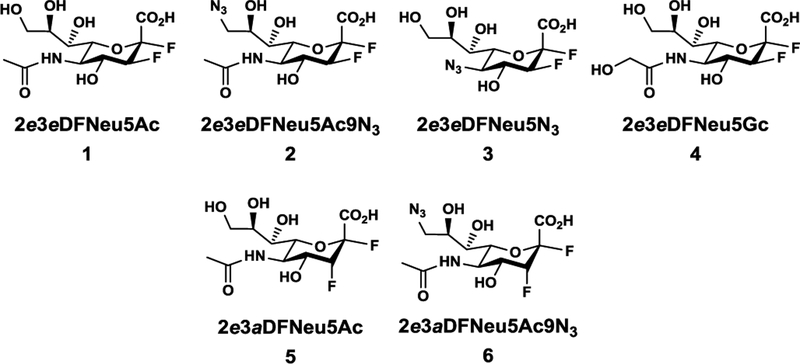

Synthesis of 2,3-Difluorosialic Acids and Analogs. A library of 2(equatorial),3(equatorial/axial)-difluoro sialic acids and analogs (Figure 1) were designed and synthesized, which include a C-3 fluorine (equatorial) with or without modification on C-5 or C-9 (Compounds 1–4), or a C-3 fluorine (axial) with or without modification on C-9 (Compounds 5–6).

Figure 1.

2,3-Difluorosialic acid and analogs synthesized and tested as potential sialidase inhibitors.

2e3eDFNeu5Ac (1) and 2e3aDFNeu5Ac (5), as well as 2e3eDFNeu5Ac9N3 (2) and 2e3aDFNeu5Ac9N3 (6) were synthesize to address the question whether C-3 fluorine stereochemistry would influence the inhibition of sialidases. 2e3eDFNeu5N3 (3) and 2e3eDFNeu5Gc (4) were produced to allow the comparison with 2e3eDFNeu5Ac (1) to study the effect of C-5 modification. The comparison of 2e3eDFNeu5Ac9N3 (2) and 2e3eDFNeu5Ac (1), as well as 2e3aDFNeu5Ac9N3 (6) and 2e3aDFNeu5Ac (5) can lead to the understanding of the effect of modifications at C-9. In addition, comparison with results from previous reported inhibition studies using C-5 and C-9 of Neu5Ac2en26 would gain insights for the preferred type of inhibitors against different bacterial sialidases.

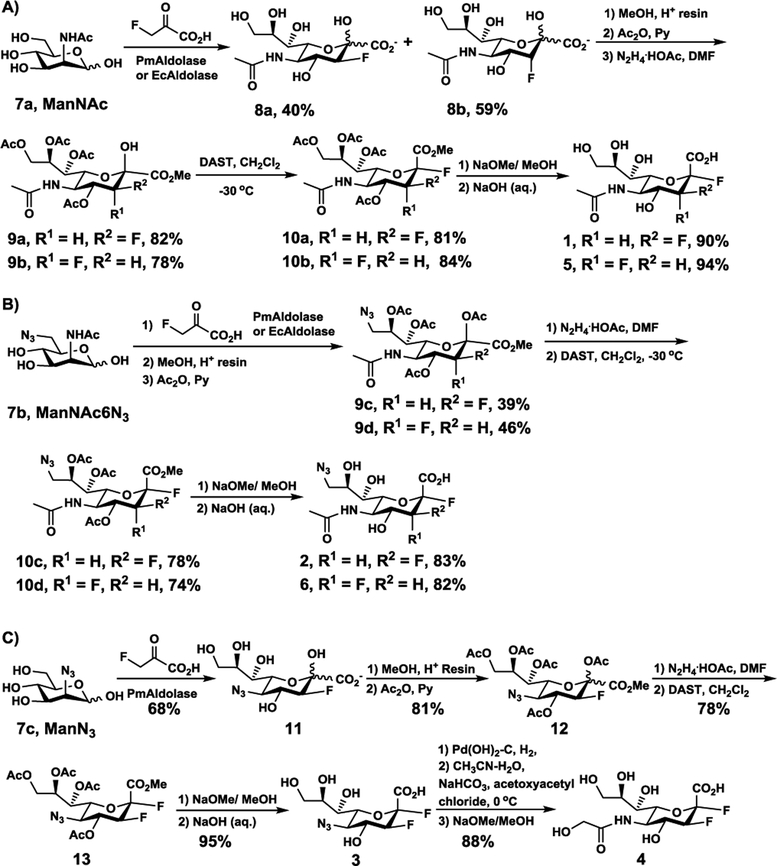

As shown in Scheme 1, an efficient chemoenzymatic method similar to a strategy reported previously32,33,41 was used to synthesize target difluoro-compounds. To obtain 2e3eDFNeu5Ac (1) and 2e3aDFNeu5Ac (5), 3-deoxy-3-fluoro-Neu5Ac intermediates 3F(e)Neu5Ac (8a) and 3F(a)Neu5Ac (8b) with a C-3 fluorine at either equatorial or axial position were synthesized by incubating sodium 3-fluoro-pyruvate with N-acetylmannosamine (7a) (Scheme 1A) in a Tris-HCl buffer (100 mM, pH = 7.5) at 37 °C for overnight in the presence of Pasteurella multocida sialic acid aldolase (PmAldolase)42 or Escherichia coli sialic acid aldolase (EcAldolase).43 A mixture of 3F(e)Neu5Ac and 3F(a)Neu5Ac (8a, 8b) diastereomers with a ratio close to 4:6 was obtained when either PmAldolase or EcAldolase was used. The diastereomers were readily purified and separated from each other by a simple silica gel column chromatography. Further modifications including esterification and per-O-acetylation followed by selective deprotection of the anomeric site using hydrazine acetate yielded hemiacetals 9a and 9b, respectively. These were treated with diethylaminosulfur trifluoride (DAST) to introduce the C-2 equatorial fluorine for the formation of 10a and 10b respectively. Full deprotection was achieved by saponification followed by the treatment with aqueous sodium hydroxide to produce compounds 1 and 5 with yields comparable to those reported previously.33

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 2,3-Difluorosialic Acids and Analogs 1–6.

To synthesize 9-azido-9-deoxy derivatives 2e3eDFNeu5Ac9N3 (2) and 2e3aDFNeu5Ac9N3 (6), 6-azido-6-deoxy-N-acetylmannosamine (ManNAc6N3, 7b)44 was used as a starting material to react with sodium 3-fluoro-pyruvate using either PmAldolase or EcAldolase to form a mixture of 3FNeu5Ac9N3 with the fluorine in either the equatorial or the axial position at C-3 (Scheme 1B). In this process, a mixture of a similar ratio of 3F(a)Neu5Ac9N3 and 3F(e)Neu5Ac9N3 was obtained as the end products despite either EcAldolase or PmAldolase was used as the catalyst. Nevertheless, 3F(a)Neu5Ac9N3 was the major product of the EcAldolase-catalyzed reaction in the initial 5 to 8 hours while both 3F(a)Neu5Ac9N3 and 3F(e)Neu5Ac9N3 were formed in almost the same ratio from the beginning in the PmAldolase-catalyzed reaction. In addition, the reaction catalyzed by PmAldolase was faster than the one catalyzed by EcAldolase. It was found challenging to separating 3F(a)Neu5Ac9N3 and 3F(e)Neu5Ac9N3 after the aldolase-catalyzed reaction. Therefore, they underwent protection procedures before being separated. Additional chemical modifications were carried out similarly to those described above for the synthesis of 2e3eDFNeu5Ac (1) and 2e3aDFNeu5Ac (5).

To introduce C-5 modification, sodium 3-fluoro-pyruvate and 2-azido-2-deoxymannose (ManN3, 7c)45,46 were incubated in Tris-HCl buffer (100 mM, pH = 7.5) at 37 °C for 4 days in the presence of PmAldolase (Scheme 1C). 3F(e)Neu5N3 (11) was obtained in 68% yield after both Bio-Gel P-2 gel filtration and silica gel chromatography purification procedures. The formation of 3F(a)Neu5N3 was observed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) but the yield was low and the product was not isolated. In contrast, EcAldolase did not work efficiently for this reaction. Methylation and esterification of 3F(e)Neu5N3 (11) formed compound 12. Upon hydrazine acetate deprotection of the anomeric ester and treatment with DAST to introduce C-2 equatorial fluorine, compound 13 was obtained. Deprotection formed the desired 2e3eDFNeu5N3 (3). It was used to synthesize 2e3eDFNeu5Gc (4) by hydrogenation, coupling with acetoxyacetyl chloride, followed by de-acetylation.32,47

Inhibition Studies. Direct comparison of the inhibition efficiencies of difluorosialic acids and Neu5Ac2en against different sialidases is difficult due to their different sialidase inhibition mechanisms (covalent versus noncovalent).34 Nevertheless, comparing the IC50 values obtained in a defined time frame and the time courses that covalent inhibitors loss their inhibitory activities against different sialidases can provide a clear idea about the efficiencies and the selectivity of the sialidase covalent inhibitors.

The sialidase inhibitory activities of the obtained 2,3-DFNeu5Ac and their C9- or C5-modified analogs (1–6) were assessed against a recombinant human cytosolic sialidase NEU2 (hNEU2)40 and eight bacterial sialidases including commercially available sialidases from V. cholerae, C. perfringens (CpNanI) and A. ureafaciens, as well as recombinant Streptococcus pneumoniae sialidases (SpNanA), SpNanB, and SpNanC,47–50 Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis ATCC15697 sialidase 2 (BiNanH2),51 and Pasteurella multocida multifunctional sialyltransferase 1 with sialidase activity (PmST1).44 Inhibition studies were carried out using Neu5Acα2–3GalβpNP as the sialidase substrate in the presence of an excess amount of β-galactosidase. The β-galactosidase catalyzed the cleavage of GalβpNP released by the sialidase to form para-nitrophenol (pNP), the majority of which was converted to para-nitrophenolate at pH higher than 9.5. The reading at A405nm correlated to the sialidase activity.40,52

Each inhibitor was initially used in a concentration of 0.1 mM to determine its percentage inhibition values against different sialidases in a 30 min-time frame. Inhibition activities of Neu5Ac2en were also tested at the same time for comparison purpose. As shown in Table 1, neither Neu5Ac2en nor any of the difluoro-compounds is an efficient inhibitor against SpNanB, SpNanC, or PmST1. This is expected for PmST153,54 which has a sialidase catalytic mechanism different from others tested here. The poor inhibitory activities of difluoro-compounds (1–6), especially the non-modified 2e3eDFNeu5Ac (1) and 2e3aDFNeu5Ac (5), against SpNanB and SpNanC are puzzling and deserve further investigation as they have been proposed to form a glycosyl-enzyme intermediate similar as hydrolytic sialidases such as SpNanA although different products were produced.49,50 Quite interestingly, while azido substitution of 9-OH of 2e3eDFNeu5Ac (1) did not affect the inhibitory activity of 2e3eDFNeu5Ac9N3 (2) against hNEU2 significantly, the same modification of 2e3aDFNeu5Ac (5) to 2e3aDFNeu5Ac9N3 (6) decreased its inhibitory activity against hNEU2 significantly from 69.7±0.4% to 1.5±0.3%. This indicates that the stereochemistry of 3-fluorine of the difluoro-compounds affects how they interact with hNEU2 and influence its catalytic activity. For other sialidases tested including those from A. ureafaciens, C. perfringens, and V. cholerae as well as SpNanA and BiNanH2, the presence of 0.1 mM of 2,3-difluoro sialic acids and analogs (compounds 1–2 and 4–6) except for 2e3eDFNeu5N3 (3) led to more than 70% inhibition with inhibitory activities comparable or better than Neu5Ac2en. For inhibitors showed less than 50% inhibition against certain sialidases at 0.1 mM concentration in the 30 min-time frame under the experimental conditions used, a higher concentration (1.0 mM) of inhibitors was used and the percentage inhibition data obtained were shown in Table 2. The combined data in Tables 1–2 defined the IC50 value ranges for weak inhibitors (IC50 = 0.1–1 mM or > 1 mM).

Table 1.

Percentage inhibition with 0.1 mM of inhibitor using Neu5Acα2–3GalβpNP as the sialidase substrate.

| Sialidases | Neu5Ac2en | 2e3eDFNeu5Ac (1) | 2e3eDFNeu5Ac9N3 (2) | 2e3eDFNeu5N3 (3) | 2e3eDFNeu5Gc (4) | 2e3aDFNeu5Ac (5) | 2e3aDFNeu5Ac9N3 (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. ureafaciens | 95.8±0.6 | 99.2±0.3 | 99.9±0.2 | 75.2±0.2 | 96.1±0.6 | 99.9±0.2 | 99.9±0.1 |

| C. perfringens | 72.1±0.0 | 80.6±0.7 | 99.9±0.1 | 29.8±1.2 | 71.6±1.2 | 99.9±0.1 | 99.9±0.1 |

| SpNanA | 94.9±2.2 | 99.7±0.3 | 85.8±0.7 | < 1.0 | 78.4±0.5 | 99.9±0.1 | 99.9 ± 0.1 |

| SpNanB | 2.7±0.3 | 11.8±1.0 | 26.8±0.2 | 35.1±0.8 | 25.3±1.7 | 12.0±0.2 | 16.7±1.6 |

| SpNanC | 6.3±0.6 | < 1.0 | < 1.0 | < 1.0 | < 1.0 | < 1.0 | < 1.0 |

| V. cholerae | 88.2±0.6 | 97.7±0.3 | 99.2±0.5 | 25±1.0 | 97.8±0.1 | 96.8±1.4 | 99.9±0.6 |

| BiNanH2 | 66.7±1.7 | 95.4±0.9 | 98.9±0.0 | 40.8±3.4 | 87.3±0.8 | 98.9±0.5 | 98.8±2.2 |

| PmST1 | 2.1±0.8 | < 1.0 | < 1.0 | < 1.0 | < 1.0 | < 1.0 | < 1.0 |

| hNEU2 | 74.9±0.0 | 75.4±0.6 | 82.3±2.8 | 37.5±1.2 | 80.4±1.3 | 69.7±0.4 | 1.5±0.3 |

Table 2.

Percentage inhibition with 1.0 mM of inhibitor using Neu5Acα2–3GalβpNP as the sialidase substrate. ND, not determined.

| Sialidases | 2e3eDFNeu5Ac (1) | 2e3eDFNeu5Ac9N3 (2) | 2e3eDFNeu5N3 (3) | 2e3eDFNeu5Gc (4) | 2e3aDFNeu5Ac (5) | 2e3aDFNeu5Ac9N3 (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. ureafaciens | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| C. perfringens | ND | ND | 30.0±0.8 | ND | ND | ND |

| SpNanA | ND | ND | 29.6±0.9 | ND | ND | ND |

| SpNanB | 30.2±2.2 | 51.9±2.2 | 38.0±0.9 | 26.0±4.9 | 19.0±0.2 | 43.8±1.4 |

| SpNanC | 25.1±6.1 | 53.9±0.1 | 6.5±0.8 | 5.5±0.2 | 55.2±0.4 | 83.7±3.5 |

| V. cholerae | ND | ND | 76.6±4.6 | ND | ND | ND |

| BiNanH2 | ND | ND | 85.6±0.5 | ND | ND | ND |

| PmST1 | 4.3±0.1 | 9.3±2.3 | 7.8±0.3 | 22.4±0.1 | 3.0±0.6 | 6.0±0.4 |

| hNEU2 | ND | ND | 80.7±1.2 | ND | ND | 53.4±1.3 |

IC50 values of 2,3-DFNeu5Ac and their C9- or C5-modified analogs (1–6) were obtained for stronger inhibitors (IC50 <0.1 mM). As shown in Table 3, in general, hydrolytic sialidases are sensitive to inhibition by DFNeu5Ac and derivatives. Intramolecular trans-sialidase (IT-sialidase) SpNanB, SpNanC that catalyzes the formation of sialidase transition state analog Sia2ens, and α2–3-sialyltransferase with sialidase activity PmST1 were not sensitive to the inhibition by difluoro-sialic acids nor Neu5Ac2en. While substitution of the 5-acetamido group in 2e3eDFNeu5Ac (1) by the 5-glycolamido group in 2e3eDFNeu5Gc (4) was well tolerated by all hydrolytic sialidases tested including both bacterial sialidases and hNEU2, replacing the same group by an azido group in 2e3eDFNeu5N3 (3) was not tolerated well, and the corresponding IC50 values increased for at least 10-fold. The low inhibitory activities of 2e3eDFNeu5N3 (3) against most sialidases tested indicate that the NH in the 5-acetamido group of DFNeu5Ac and derivatives is important for sialidase binding. Substitution of C9-OH by an azido group in general improved IC50 values against sensitive bacterial sialidases. On the contrary, the same substitution on 2e3aDFNeu5Ac9N3 (6) led to at least 10-fold decrease in inhibitory activity against hNEU2 although it did not affect the hNEU2 inhibitory activity of 2e3eDFNeu5Ac9N3 (2) significantly.

Table 3.

IC50 values (μM) of potential inhibitors against bacterial and human sialidases using Neu5Acα2–3GalβpNP as a substrate.

| Sialidases | Neu5Ac2en | 2e3eDFNeu5Ac (1) | 2e3eDFNeu5Ac9N3 (2) | 2e3eDFNeu5N3 (3) | 2e3eDFNeu5Gc (4) | 2e3aDFNeu5Ac (5) | 2e3aDFNeu5Ac9N3 (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. ureafaciens | 8.1±0.3a | 2.1±0.1 | (1.5±0.1)×10−1 | (7.1±0.4)×10 | 3.5±0.1 | (1.1±0.1)×10−1 | (5.2±0.1)×10−3 |

| C. perfringens | (2.0±0.1)×10b | (1.7±0.3)×10 | (7.3±0.4)×10−1 | > 1×103 | (4.1±0.5)×10 | (1.8±0.1)×10−1 | (2.4±0.1)×10−2 |

| SpNanA | (1.0±0.1)×10a | (1.1±0.1)×10 | (2.1±0.2)×10−1 | > 1×103 | (2.0±0.2)×10 | (1.3±0.2)×10−1 | (3.3±0.2)×10−2 |

| SpNanB | (3.7±0.6)×103b | > 1×103 | (1–10)×102 | > 1×103 | > 1×103 | > 1×103 | > 1×103 |

| SpNanC | > 1×103c | > 1×103 | (1–10)×102 | > 1×103 | > 1×103 | (1–10)×102 | (1–10)×102 |

| V. cholerae | 8.6±1.0d | 2.0±0.1 | (7.3±0.5)×10−1 | (1–10)×102 | 1.6±0.1 | (3.3±0.4)×10−1 | (1.8±0.1)×10−1 |

| BiNanH2 | (4.0±0.2)×10a | 6.5 ± 0.6 | (3.3±0.3)×10−1 | (1–10)×102 | (1.7±0.2)×10 | (2.6±0.1)×10−1 | (1.0±0.1)×10−1 |

| PmST1 | > 1×103c | > 1×103 | > 1×103 | > 1×103 | > 1×103 | > 1×103 | > 1×103 |

| hNEU2 | (1.8±0.1)×10d | (2.3±0.2)×10 | (2.8±0.2)×10 | (1–10)×102 | (2.6±0.4)×10 | (5.2±0.8)×10 | (1–10)×102 |

3F(a)-compounds showed 5- to 100-fold increased inhibitory activity against sensitive bacterial sialidases compared to their 3F(e)-counterparts. This was opposite to that observed for influenza A virus sialidases34 or hNEU2 for which 3F(a)-compounds were worse inhibitors compared to their 3F(e)-counterparts. Among all difluoro-compounds tested, 2e3aDFNeu5Ac9N3 (6) was the most effective and selective inhibitor against bacterial hydrolytic sialidases including Arthrobacter ureafaciens sialidase, Clostridium perfringens sialidase (CpNanI), and SpNanA, with IC50 values of 5.2 ± 0.1 nM, 24 ± 1 nM, and 33 ± 2 nM, respectively. Its IC50 values for inhibition against V. cholerae sialidase and BiNanH2 were also at least 500-fold better than that for hNEU2. Among these, SpNanA is an essential virulence factor for S. pneumoniae infection and is considered a valid drug target.50 Sialidase from epidemic strains of V. cholerae, a causive agent of cholera is a potential drug target.55 CpNanI facilitates the infection of Gram-positive pathogenic bacterium Clostridium perfringens.56,57

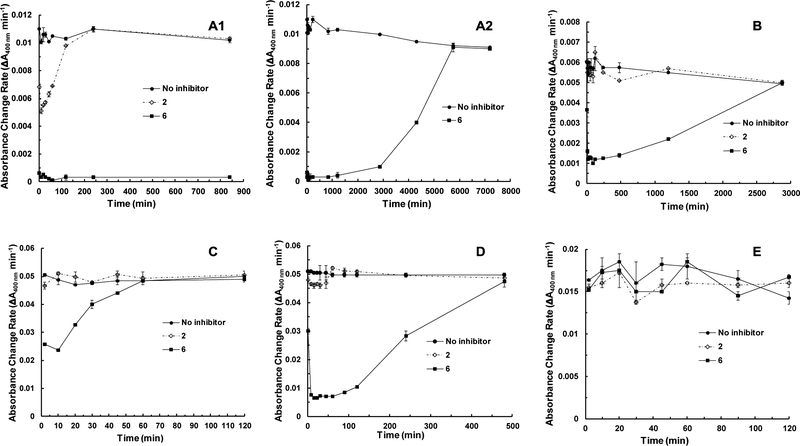

Time course study for sialidase de-activation and re-activation in the presence of a covalent inhibitor. As sialidase covalent inhibitors de-activate sialidases by forming a covalent sialosyl-enzyme intermediate which can be hydrolyzed in a time-dependent manner and the sialidases eventually regain activities,34 time-dependent sialidase activity loss and regain in the presence of difluorosialic acids and derivatives (1–6) were investigated. As shown in Figure 2 and Figure S2 (see ESI), among sialidases tested including pathogenic bacterial sialidases CpNanI (Figure S2A), V. cholera sialidase (Figure S2B), and SpNanA (Figure S2C), commensal bacterial sialidase BiNanH2 (Figure S2D), and human sialidase hNEU2 (Figure S2E), none of them were sensitive to difluorosialic acids and derivatives 1 and 3–5. In comparison, except for hNEU2 (Figure 2E), all bacterial sialidases tested were sensitive to 2e3aDFNeu5Ac9N3 (6). CpNanI (Figure 2A1), but not other bacterial sialidases tested, was also sensitive to 2e3eDFNeu5Ac9N3 (2) inhibition although to a less extend compared to its sensitivity to 2e3aDFNeu5Ac9N3 (6). In general, sensitive sialidases were de-activated very quickly (<10 min) by 2e3aDFNeu5Ac9N3 (6) but the time frames for their re-activations varied significantly. The half-life for re-activation of SpNanA (Figure 2C, 25 min), BiNanH2 (Figure 2D, 4 h), V. cholerae sialidase (Figure 2B, 24 h), and CpNanI (Figure 2A2, 2 days) ranged from 25 min – 2 days. With a high inhibitory activity and a long effective time frame against pathogenic bacterial sialidases CpNanI and V. cholerae sialidase, 2e3aDFNeu5Ac9N3 (6) is a promising candidate for further drug development.

Figure 2.

Time course study results for sialidase de-activation and re-activation in the presence or the absence of a covalent inhibitor (2 or 6). A, C. perfringens sialidase CpNanI (A1, 2 min – 14 h for compounds 2 and 6 with no inhibitor as the control; A2, 2 min – 5 days for compound 6 with no inhibitor as the control); B, V. cholerae sialidase; C, SpNanA; D, BiNanH2; E, hNEU2.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, six 2,3-difluorosialic acids and analogs (1–6) with a 2F(e) and a 3F(a/e) with or without an additional modification at C5- or C9 have been chemoenzymatically synthesized as potential inhibitors against bacterial sialidases. PmAldolase was shown to be a superior catalyst compared to EcAldolase for the synthesis of 3-fluorosialic acids and analogs, the precursors for the chemical synthesis of desired 2,3-difluoro-compounds. Inhibition studies showed that the NH in the 5-acetamido group of difluoro-sialic acids is important for the design of the sialidase inhibitors. In contrast to the observations that 2e3a-difluorosialic acid analogs were worse inhibitors compared to its 3F(e) counterparts against human cytosolic sialidase hNEU2 and influenza A virus sialidases, they were better inhibitors against hydrolytic bacterial sialidases tested. The azido group substitution of the C9-OH in 2,3-difluorosialic acids improved their inhibitory activity and duration against hydrolytic bacterial sialidases. 2e3aDFNeu5Ac9N3 (6) has been identified as an effective and selective inhibitor with a high inhibitory activity and a long effective time-frame against pathogenic bacterial sialidases from Clostridium perfringens (CpNanI) and V. cholerae. It is a promising sialidase inhibitor that can be further developed as chemical biological tools and potential anti-bacterial therapeutics.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials and General Methods. Chemicals were obtained from commercial suppliers and used without further purification. 1H NMR, 13C NMR, 19F NMR spectra were recorded on 400 MHz Bruker Avance III and 800 MHz Bruker Avance III spectrometers. High resolution electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectra were obtained using Thermo Electron LTQ-Orbitrap XL Hybrid MS at the Mass Spectrometry Facility in the University of California, Davis. Silica gel 60 Å (230–400 mesh, Sorbent Technologies) was used for flash column chromatography. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC, Sorbent Technologies) was performed on silica gel plates using anisaldehyde sugar staining or 5% sulfuric acid in ethanol staining for detection. Gel filtration chromatography was performed with a column (100 cm × 2.5 cm) packed with Bio-Gel P-2 Fine resins (Bio-Rad). 3-Fluoropyruvic acid sodium salt monohydrate was from Sigma. Sialidases from V. cholerae, and A. ureafaciens were purchased from Prozyme. Sialidases from C. perfringens (CpNanI) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Recombinant Escherichia coli sialic acid aldolase43 and Pasteurella multocida sialic acid aldolase (PmAldolase),42 SpNanA and SpNanB,48 SpNanC,47 hNEU2,40 Bifidobacterium longum subsp. Infantis ATCC 15697 sialidase 2 (BiNanH2),51 and PmST144 were expressed and purified as described previously.

Chemical and Enzymatic Synthesis of 2,3-Difluorosialic Acids 1–6.

Synthesis of 5-acetamido-2,3,5-trideoxy-3-fluoro-D-erythro-α-L-gluco-non-2-ulopyranosylonic fluoride (2e3eDFNeu5Ac) (1) and 5-acetamido-2,3,5-trideoxy-3-fluoro-D-erythro-α-L-manno-non-2-ulopyranosylonic fluoride (2e3aDFNeu5Ac) (5)

Compounds 1 and 5 were chemoenzymatically synthesized similar to those reported previously32,33 with modifications.

N-Acetylmannosamine (ManNAc, 7a) (1.0 g, 4.52 mmol) and 3-fluoropyruvic acid sodium salt monohydrate (3.30 g, 22.60 mmol) were dissolved in water in a 500 mL Teflon container containing Tris-HCl buffer (100 mM, pH 7.5) and MgCl2 (20 mM). After adding an appropriate amount of PmAldolase (10 mg), water was added to bring the final volume of the reaction mixture to 225 mL. The reaction was carried out by incubating the solution at 37 °C with agitation at 100 rpm in an incubator for 1 day. The product formation was monitored by thin layer chromatography (TLC) developed with EtOAc:MeOH:H2O:HOAc = 6:2:1:0.1 (by volume) and stained with p-anisaldehyde sugar stain. Upon the completion of the reaction, the mixture was centrifuged. The supernatant was concentrated and passed through a Bio-Gel P-2 gel filtration column using water as an eluent. The products were further purified using a silica gel column chromatography to separate 8a (630 mg, 40%) and 8b (940 mg, 59%) as white solids.

5-Acetamido-2,3,5-trideoxy-3-fluoro-D-erythro-α-L-gluco-non-2-ulopyranosylonic fluoride (2e3eDFNeu5Ac, 1). Compound 8a (600 mg, 1.83 mmol) was dissolved in dry MeOH (20 mL) and ion exchange resin Amberlite® 120-H (1.5 g) was added. The mixture was refluxed for 5 h under a nitrogen atmosphere, the filtered through Celite, and washed with MeOH. The solvent was removed in vacuo and co-evaporated with 50 mL of toluene for four times. The intermediate methyl ester was dried in vacuo for 12–14 h and directly used for the next step without further purification.

To a solution of intermediate in 30 mL pyridine at 0 °C, 20 mL acetic anhydride was added drop wisely followed by the addition of a catalytic amount of DMAP. After being stirred at 0 °C for 1 h, the mixture was allowed to warm up to room temperature and stirred for a total of 10 h. The solvent was removed in vacuo and co-evaporated with 30 mL of toluene for four times. The intermediate was used directly for the next step without further purification.

To a solution of the intermediate in dry CH2Cl2 (50 mL), hydrazine acetate (820 mg, 9 mmol) in dry methanol (10 mL) was added and the mixture was stirred at 0 °C under an inert atmosphere (N2) for 8 h. The mixture was evaporated and the crude product was dissolved in EtOAc (80 mL). The organic layer was washed sequentially with HCl (1 N) and a saturated aqueous solution of NaHCO3, and dried using Na2SO4. The solvents were removed under a reduced pressure. Purification by silica gel column chromatography (EtOAc:hexane = 8:1, by volume) yielded compound 9a (765 mg, 82%) as a white foam.

DAST (0.27 mL, 2.05 mmol) was added drop wisely to a solution of hemiacetal 9a (700 mg, 1.37 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (20 mL) at −30 °C and the mixture was stirred under an Argon atmosphere at this temperature for 15 minutes. The reaction was quenched by adding MeOH (400 μL) and the mixture was evaporated. The residue was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (30 mL). The organic layer was washed sequentially with HCl (1 N) and a saturated aqueous solution of NaHCO3, and dried using Na2SO4. The solvents were removed under a reduced pressure. Purification by silica gel column chromatography (EtOAc:hexane = 9:1, by volume) afforded compound 10a (570 mg, 81%) as a white foam.

To a solution of compound 10a (550 mg, 1.07 mmol) at 0 °C in MeOH (20 mL), NaOMe (400 μL, 5.4 N in MeOH) was added drop wisely. The mixture was stirred at this temperature for 2 hours, then NaOH (1 M, 1.0 mL) was added and the stirring was continued for another 2 h. The reaction mixture was neutralized by adding ion exchange resin Amberlite® IR-120H, concentrated and purified using a C18 column on a CombiFlashRf 200i system by eluting with a gradient of 0–100% acetonitrile in water. The fractions containing the desired product were collected, combined, and lyophilized to produce compound 1 as a white powder. The product (318 mg, 90%) was further purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using a C18 column and water and acetonitrile as solvent and lyophilized. 1H NMR (800 MHz, D2O) δ 4.64–4.51 (m, 1H), 4.38–4.31 (m, 1H), 4.24 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 1H), 4.14 (t, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 3.75 (dd, J = 12.0, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 3.72–3.68 (m, 1H), 3.53 (dd, J = 12.0, 6.4 Hz, 1H), 3.43 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 1.98 (s, 3H); 13C{H} NMR (200 MHz, D2O) δ 174.3 (s, 1C, C=O), 168.5 (d, 1C, J1,F2 = 32 Hz, C-1), 107.0 (dd, 1C, J2,F = 220 Hz, J2,F3 = 28 Hz, C-2), 93.2 (dd, 1C, J3,F3 = 186 Hz, J3,F2 = 30 Hz, C-3), 73.0 (s, 1C, C-6), 70.2 (dd, 1C, J4,F3 = 18 Hz, J4,F2 = 8 Hz, C-4), 69.3 (C-8), 67.2 (s, 1C, C-7), 62.6 (s, 1C, C-9), 49.1 (d, 1C, J5,F3 = 8 Hz, C-5), 21.4 (s, 1C, NHCOCH3); 19F NMR (376 MHz, D2O) δ −112.2 (t, J = 13.7 Hz), −201.7 (ddd, J = 49.6, 14.4, 2.6 Hz); HRMS (ESI-Orbitrap) m/z: [M – H]− Calcd for C11H16F2NO8 328.0849; found 328.0834.

5-Acetamido-2,3,5-trideoxy-3-fluoro-D-erythro-α-L-manno-non-2-ulopyranosylonic fluoride (2e3aDFNeu5Ac, 5). The synthesis of compound 5 (485 mg) from 8b (900 mg) was processed similarly as that described for the synthesis of compound 1 from 8a. 1H NMR (800 MHz, D2O) δ 5.01 (dd, 1H, J = 2.4 and 48.0 Hz, H-3), 4.34 (t, 1H, J = 11.2 Hz, H-5), 4.14 (dd, 1H, J = 12.0 and 28.8 Hz, H-4), 4.11 (d, 1H, J = 11.2 Hz, H-6), 3.88–3.84 (m, 2H, H-8, H-9a), 3.64 (dd, 1H, J = 6.4 and 12.0 Hz, H-9b), 3.53 (d, 1H, J = 8.8, H-7), 2.05 (s, 3H, NHCOCH3);13C{H} NMR (200 MHz, D2O) δ 174.7 (s, C=O), 169.8 (dd, 1C, J1,F2 = 23.3 Hz, C-1), 106.5 (dd, 1C, J2,F = 224.7 Hz, J2,F3 = 29.5 Hz, C-2), 87.5 (dd, 1C, J3,F3 = 176.5 Hz, J3,F2 = 45.6 Hz, C-3), 72.2 (C-6), 69.7 (C-8), 68.0 (C-7), 67.5 (d, 1C, J = 17.8 Hz), 63.1 (C-9), 46.5 (d, J5,F3 = 2.4 Hz, C-5), 22.0 (s, 1C, NHCOCH3); 19F NMR (376 MHz, D2O) δ −123.27 (d, JF2,F3 = 13.6 Hz, F-2), −209.63 (ddd, JF3,H3 = 42.9 Hz, JF3,H4 = 29.3 Hz, JF3,F2 = 13.2 Hz, F-3); HRMS (ESI-Orbitrap) m/z: [M – H]− Calcd for C11H16F2NO8 328.0849; found 328.0838.

Synthesis of 5-acetamido-9-azido-2,3,5,9-tetradeoxy-3-fluoro-D-erythro-α-L-gluco-non-2-ulopyranosylonic fluoride (2e3eDFNeu5Ac9N3, 2) and 5-acetamido-9-azido-2,3,5,9-tetradeoxy-3-fluoro-D-erythro-α-L-manno-non-2-ulopyranosylonic fluoride (2e3aDFNeu5Ac9N3, 6). 6-Azido-6-deoxy-N-acetylmannosamine (ManNAc6N3, 7b)44 (1.0 g, 4.06 mmol) and 3-fluoropyruvic acid sodium salt monohydrate (2.96 g, 20.03 mmol) were dissolved in water in a 500 mL Teflon container containing Tris-HCl buffer (100 mM, pH 7.5) and MgCl2 (20 mM). After the addition of an appropriate amount of PmAldolase (12 mg), water was added to bring the final volume of the reaction mixture to 200 mL. The reaction was carried out by incubating the solution at 37 °C with agitation at 100 rpm in an incubator for 2 days. The product formation was monitored by thin layer chromatography (TLC) developed with EtOAc:MeOH:H2O:HOAc = 6:2:1:0.1 (by volume) and stained with p-anisaldehyde sugar stain. Upon the completion of the reaction, the mixture was centrifuged. The supernatant was concentrated and passed through a Bio-Gel P-2 gel filtration using water as an eluent. The product was purified further using silica gel column chromatograph to produce a mixture of two diastereomers.

The mixture of diastereomers (1.3 g, 3.69 mmol) was dissolved in dry MeOH (75 mL) and ion exchange resin Amberlite® 120-H (4.5 g) was added. The mixture was refluxed for 5 h under a nitrogen atmosphere, filtered through Celite and washed with MeOH. The solvent was removed in vacuo and co-evaporated with 50 mL of toluene for four times. The intermediate methyl ester was dried in vacuo for 12–14 h and used directly for the next step without further purification.

To a solution of intermediate in 75 mL pyridine at 0 °C, 50 mL of acetic anhydride was added drop wisely followed by the addition of a catalytic amount of DMAP. After being stirred at 0 °C for 1 h, the mixture was allowed to warm up to room temperature and stirred for a total of 10 h. The solvent was removed in vacuo and co-evaporated with 30 mL of toluene for four times. Purification by silica gel column chromatography (EtOAc:hexane = 5:1, by volume) yielded compound 9c(0.84 g, 39%) and 9d (1.01g, 46%) as white foams.

5-Acetamido-9-azido-2,3,5,9-tetradeoxy-3-fluoro-D-erythro-α-L-gluco-non-2-ulopyranosylonic fluoride (2e3eDFNeu5Ac9N3, 2). To a solution of compound 9c (0.80 g, 1.49 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (30 mL), hydrazine acetate (830 mg, 9 mmol) in dry methanol (10 mL) was added and the mixture was stirred at 0 °C under an inert atmosphere (N2) for 8 h. The mixture was then evaporated and the crude product was dissolved in EtOAc (80 mL). The organic layer was washed sequentially with HCl (1 N) and a saturated aqueous solution of NaHCO3, and dried using Na2SO4. The solvents were removed under a reduced pressure. The residue was dried in vacuo for 10–12 h and used in the next step without further purification.

DAST (0.30 mL, 2.23 mmol) was added drop wisely to a solution of hemiacetalin dry CH2Cl2 (25 mL) at −30 °C and the mixture was stirred under an argon atmosphere at this temperature for 15 minutes. The reaction was quenched by adding MeOH (250 μL) and the mixture was evaporated. The residue was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (30 mL). The organic layer was washed sequentially with HCl (1 N) and a saturated aqueous solution of NaHCO3, and dried using Na2SO4. The solvents were removed under a reduced pressure. Purification by silica gel column chromatography (EtOAc:hexane = 5:1, by volume) afforded compound 10c (577 mg, 78%) as a white foam.

To a solution of compound 10c (570 mg, 1.15 mmol) in MeOH (15 mL) at 0 °C, NaOMe (300 μL, 5.4 N in MeOH) was added drop wisely. The mixture was stirred at this temperature for 2 hours, then NaOH (1 M, 1.0 mL) was added and the stirring was continued for another 2 h. The reaction mixture was neutralized by adding ion exchange resin Amberlite® IR-120H, concentrated and purified using a C18 column on a CombiFlash (Rf 200i system) eluted with a gradient of 0–100% acetonitrile in water. The fractions containing the desired product were collected, combined, and lyophilized to produce compound 2 as a white powder. The product (338 mg, 83%) was further purified by HPLC (C18 column and water and acetonitrile as solvent) and lyophilized. 1H NMR (800 MHz, D2O) δ 4.76–4.52 (m, 1H), 4.49–4.37 (m, 1H), 4.32 (d, J = 10.8 Hz, 1H), 4.20 (t, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 3.96–3.87 (m, 1H), 3.59 (dd, J = 13.2, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 3.52 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 3.44 (dd, J = 13.2, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 2.06 (s, 3H); 13C{H} NMR (200 MHz, D2O) δ 174.3 (s, 1C, C=O), 168.4 (d, 1C, J1,F2 = 32 Hz, C-1), 107.1 (dd, 1C, J2,F = 218 Hz, J2,F3 = 26 Hz, C-2), 93.3 (dd, 1C, J3,F3 = 184 Hz, J3,F2 = 30 Hz, C-3), 72.9 (s,1C, C-6), 70.2 (dd, 1C, J4,F3 = 18 Hz, J4,F2 = 6 Hz, C-4), 68.3 (s, 1C, C-8), 67.7 (s, 1C, C-7), 53.4 (s, 1C, C-9), 49.2 (d, 1C, J5,F3 = 8 Hz, C-5), 21.5 (s, 1C, NHCOCH3); 19F NMR (376 MHz, D2O) δ: −112.78 (t, J = 14.1 Hz), −201.1 (ddd, J = 49.2, 14.4, 2.6 Hz). HRMS (ESI-Orbitrap) m/z: [M – H]− Calcd for C11H15F2N4O7 353.0914; found 353.0927.

5-Acetamido-9-azido-2,3,5,9-tetradeoxy-3-fluoro-D-erythro-α-L-manno-non-2-ulopyranosylonic fluoride (2e3aDFNeu5Ac9N3, 6). To a solution of compound 9d (1.0 g, 1.87 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (50 mL), hydrazine acetate (1.0 g, 11.22 mmol) in dry methanol (15 mL) was added and the mixture was stirred at 0 °C under an inert atmosphere (N2) for 8 h. The mixture was then evaporated and the crude product was dissolved in EtOAc (80 mL). The organic layer was washed sequentially with HCl (1 N) and a saturated aqueous solution of NaHCO3, and dried using Na2SO4. The solvents were removed under a reduced pressure. The residue was dried in vacuo for 10–12 h and used in the next step without further purification.

DAST (0.37 mL, 2.8 mmol) was added dropwise to a solution of hemiacetal in dry CH2Cl2 (30 mL) at −30 °C and the mixture was stirred under an Argon atmosphere at this temperature for 15 minutes. The reaction was quenched by adding MeOH (250 μL) and the mixture was evaporated. The residue was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (30 mL). The organic layer was washed sequentially with HCl (1 N) and a saturated aqueous solution of NaHCO3, and dried using Na2SO4. The solvents were removed under a reduced pressure. Purification by silica gel column chromatography (EtOAc:hexane = 5:1, by volume) afforded compound 10d (685 mg, 74%) as a white foam.

To a solution of compound 10d (680 mg, 1.38 mmol) in MeOH (25 mL) at 0 °C, NaOMe (500 μL, 5.4 N in MeOH) was added drop wisely. The mixture was stirred at this temperature for 2 hours, then NaOH (1 M, 1.5 mL) was added and the stirring was continued for another 2 h. The reaction mixture was neutralized by adding ion exchange resin Amberlite® IR-120H, concentrated and purified using a C18 column on a CombiFlashRf 200i system eluted with a gradient of 0–100% acetonitrile in water. The fractions containing the desired product were collected, combined, and lyophilized to produce compound 6 as a white powder. The product (400 mg, 82%) was further purified by HPLC (C18 column and water and acetonitrile as solvent) and lyophilized. 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O) δ 5.24–4.97 (m, 1H), 4.20 (t, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 4.15–4.00 (m, 1H), 4.00–3.86 (m, 1H), 3.74 (d, J = 10.2 Hz, 1H), 3.57 (dd, J = 13.2, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 3.48 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 3.40 (dd, J = 13.2, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 1.97 (s, 3H); 13C{H} NMR (200 MHz, D2O) δ 174.5 (s, 1C, C=O), 168.1 (dd, 1C, J1,F2 = 28 Hz and 2 Hz, C-1), 106.3 (dd, 1C, J2,F = 218 Hz, J2,F3 = 14 Hz, C-2), 88.5 (dd, 1C, J3,F3 = 184 Hz, J3,F2 = 18 Hz, C-3), 72.1 (s, 1C, C-6), 68.6 (s, 1C, C-8), 68.4 (dd, 1C, J4,F3 = 18 Hz, J4,F2 = 6 Hz, C-4), 67.8 (s, 1C, C-7), 53.2 (s, 1C, C-9), 46.3 (d, 1C, J5,F3 = 2.4 Hz, C-5), 21.6 (s, 1C, NHCOCH3); 19F NMR (376 MHz, D2O) δ −121.13 (d, J = 11.7 Hz), −217.76 (ddd, J = 51.5, 28.6, 11.7 Hz); HRMS (ESI-Orbitrap) m/z: [M – H]− Calcd for C11H15F2N4O7 353.0914; found 353.0935.

Synthesis of 5-azido-2,3,5-trideoxy-3-fluoro-D-erythro-α-L-gluco-non-2-ulopyranosylonic fluoride (2e3eDFNeu5N3) (3)

5-Azido-3,5-dideoxy-3-fluoro-D-erythro-L-gluco-2-nonulopyranosonic acid (11). 2-Azidomannose (0.5 g, 2.43 mmol)45,46 and 3-fluoropyruvic acid sodium salt monohydrate (1.8 g, 12.32 mmol) were dissolved in water in a 500 mL Teflon container containing Tris-HCl buffer (100 mM, pH 7.5) and MgCl2 (20 mM). After the addition of an appropriate amount of PmAldolase (10 mg), water was added to bring the final volume of the reaction mixture to 100 mL. The reaction was carried out by incubating the solution at 37 °C with agitation at 100 rpm in an incubator for 4 days. The product formation was monitored by thin layer chromatography (TLC) developed with EtOAc:MeOH:H2O:HOAc = 6:2:1:0.1 (by volume) and stained with p-anisaldehyde sugar stain. Upon the completion of the reaction, the mixture was centrifuged. The supernatant was concentrated and passed through a Bio-Gel P-2 gel filtration using water as an eluent. The product was purified further using silica gel chromatograph to produce 11 (516 mg, 68%). 1H NMR (800 MHz, D2O) δ 4.60 (dd, J = 49.6, 8.8 Hz, 1H), 4.08 (dd, J = 22.4, 9.6 Hz, 1H), 3.94 (d, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 3.84 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H), 3.77–3.70 (m, 2H), 3.68 (t, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 3.63 (dd, J = 12.0, 6.4 Hz, 1H); 13C{H} NMR (200 MHz, D2O) δ 173.1 (s, 1C, C-1), 94.2 (d, 1C, J2,F3 = 20 Hz, C-2), 91.1 (d, 1C, J3,F3 = 188 Hz, C-3), 70.7 (d, 1C, J4,F3 = 18 Hz, C-4), 69.6 (s, 1C, C-6), 69.2 (s, 1C, C-8), 68.0 (s, 1C, C-7), 62.7 (s, 1C, C-9), 61.0 (d, 1C, J5,F3 = 8 Hz, C-5); 19F NMR (376 MHz, D2O) δ −200.2 (dd, J = 52.8, 13.6 Hz); HRMS (ESI-Orbitrap) m/z: [M – H]− Calcd for C9H13FN3O8 310.0692; found 310.0675.

Methyl 5-azido-2,4,7,8,9-penta-O-acetyl-3,5-dideoxy-3-fluoro-D-erythro-L-gluco-non-2-ulopyranosonate (12). Compound 11 (0.5 g, 1.6 mmol) was dissolved in dry MeOH (50 mL) and ion exchange resin Amberlite® 120-H (1.5 g) was added. The mixture was refluxed for 5 h under a nitrogen atmosphere, filtered through Celite and washed with MeOH. The solvent was removed in vacuo and co-evaporated with 20 mL of toluene for four times. The intermediate methyl ester was dried in vacuo for 12–14 h and directly used for the next step without further purification.

To a solution of intermediate in 30 mL pyridine at 0 °C, 25 mL of acetic anhydride was added drop wisely followed by the addition of a catalytic amount of DMAP. After being stirred at 0 °C for 1 h, the mixture was allowed to warm up to room temperature and stirred for a total of 10 h. The solvent was removed in vacuo and co-evaporated with 30 mL of toluene for four times. Purification by silica gel column chromatography (EtOAc:hexane = 1:1, by volume) yielded compound 12 (697 mg, 81%) as a white foam. 1H NMR (800 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.56 (dt, J = 11.2, 9.6 Hz, 1H), 5.47 (dd, J = 7.2, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 5.13 (m, 1H), 4.49 (dd, J = 48.8, 9.6 Hz, 1H), 4.41 (dd, J = 12.8, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 4.20 (dd, J = 12.8, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 3.82 (s, 3H), 3.71 (dd, J = 11.2, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 3.42 (t, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 2.21 (s, 41H), 2.19 (s, 3H), 2.18 (s, 3H), 2.04 (s, 6H); 13C{H} NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.7 (s, 1C, C=O), 170.0 (s, 1C, C=O), 169.6 (s, 1C, C=O), 169.4 (s, 1C, C=O), 167.7 (s, 1C, C=O), 164.3 (s, 1C, C-1), 95.1 (d, 1C, J2,F3 = 20 Hz, C-2), 87.9 (d, 1C, J3,F3 = 204 Hz, C-3), 71.2 (d, 1C, J4,F3 = 20 Hz, C-4), 70.7 (s, 1C, C-6), 69.8 (s, 1C, C-8), 67.8 (s, 1C, C-7), 61.4 (s, 1C, C-9), 59.5 (d, 1C, J5,F3 = 6 Hz, C-5), 53.6 (s, 1C, COOMe), 20.9 (s, 1C, COCH3), 20.8 (s, 2C, COCH3), 20.7 (s, 2C, COCH3); 19F NMR (376 MHz, D2O) δ −201.1 (dd, J = 52.0, 12.0 Hz); HRMS (ESI-Orbitrap) m/z: [M + Na]+ Calcd for C20H26FN3O13Na 558.1342; found 558.1368.

Methyl 5-acetamido-4,7,8,9-tetra-O-acetyl-2,3,5-trideoxy-3-fluoro-D-erythro-α-L-gluco-non-2-ulopyranosylonate fluoride (13). To a solution of compound 12 (650 mg, 1.21 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (15 mL), hydrazine acetate (552 mg, 6 mmol) in dry methanol (4 mL) was added and the mixture was stirred at 0 °C under an inert atmosphere (N2) for 8 h. The mixture was then evaporated and the crude product was dissolved in EtOAc (50 mL). The organic layer was washed sequentially with HCl (1 N) and a saturated aqueous solution of NaHCO3, and dried using Na2SO4. The solvents were removed under a reduced pressure. The residue was dried in vacuo for 10–12 h and used in the next step without further purification.

DAST (0.24 mL, 1.81 mmol) was added drop wisely to a solution of hemiacetal in dry CH2Cl2 (15 mL) at −30 °C and the mixture was stirred under an Argon atmosphere at this temperature for 15 minutes. The reaction was quenched by addition of MeOH (100 μL) and the mixture was evaporated. The residue was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (30 mL). The organic layer was washed sequentially with HCl (1 N) and a saturated aqueous solution of NaHCO3, and dried using Na2SO4. The solvents were removed under a reduced pressure. Purification by silica gel column chromatography (EtOAc:hexane = 1:1, by volume) produced compound 13 (469 mg, 78%) as a white foam. 1H NMR (800 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.67 (ddd, J = 15.2, 9.6, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 5.45 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 5.34 (m, 1H), 4.59 (m, 1H), 4.28 (dd, J = 12.0, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 4.20 (dd, J = 12.0, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 4.16 (d, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 3.88 (s, 3H), 3.46 (t, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 2.18 (s, 3H), 2.18 (s, 3H), 2.08 (s, 3H), 2.06 (s, 3H); 13C{H} NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.7 (s, 1C, C=O), 169.9 (s, 1C, C=O), 169.5 (s, 1C, C=O), 169.2 (s, 1C, C=O), 164.4 (d, 1C, J1,F2 = 32 Hz, C-1), 106.1 (dd, 1C, J2,F = 230 Hz, J2,F3 = 28 Hz, C-2), 90.6 (dd, 1C, J3,F3 = 192 Hz, J3,F2 = 30 Hz, C-3), 72.4 (s, 1C, C-6), 72.1 (dd, 1C, J4,F3 = 22 Hz, J4,F2 = 6 Hz, C-4), 68.1 (s, 1C, C-8), 67.1 (s, 1C, C-7), 61.8 (s, 1C, C-7), 58.5 (d, 1C, J5,F3 = 6 Hz, C-5), 53.7 (s, 1C, COOMe), 20.8 (s, 1C, COCH3), 20.7 (s, 2C, COCH3), 20.6(s, 1C, COCH3); 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ −116.94 (t, J = 14.0 Hz), −200.37 (dt, J = 48.5, 14.6 Hz); HRMS (ESI-Orbitrap) m/z: [M+Na]+ Calcd for C18H23F2N3O11Na 518.1193; found 518.1209.

5-Azido-2,3,5-trideoxy-3-fluoro-D-erythro-α-L-gluco-non-2-ulopyranosylonic fluoride (2e3eDFNeu5N3, 3). To a solution of compound 13 (450 mg, 0.90 mmol) in MeOH (10 mL) at 0 °C, NaOMe (300 μL, 5.4 N in MeOH) was added drop wisely. The mixture was stirred at this temperature for 2 hours, then NaOH (1 M, 1.5 mL) was added and the stirring was continued for another 2 h. The reaction mixture was neutralized by adding ion exchange resin Amberlite® IR-120H, concentrated and purified using a C18 column on a CombiFlash (Rf 200i system) eluted with a gradient of 0–100% acetonitrile in water. The fractions containing the desired product were collected, combined, and lyophilized to produce compound 3 as a white powder. The product (270 mg, 95%) was further purified by HPLC (C18 column and water and acetonitrile as solvent) and lyophilized. 1H NMR (800 MHz, D2O) δ 4.66–4.57 (m, 1H), 4.45 (dt, J = 16.8, 8.8 Hz, 1H), 4.20 (d, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 3.83 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H), 3.79–3.72 (m, 3H), 3.62 (dd, J = 11.2, 5.6 Hz, 1H); 13C{H} NMR (200 MHz, D2O) δ 168.5 (d, 1C, J1,F2 = 32 Hz, C-1), 107.2 (dd, 1C, J2,F = 222 Hz, J2,F3 = 28 Hz, C-2), 92.9 (dd, 1C, J3,F3 = 186 Hz, J3,F2 = 30 Hz, C-3), 73.0 (s,1C, C-6),71.5 (dd, 1C, J4,F3 = 20 Hz, J4,F2 = 6 Hz, C-4), 69.4 (s, 1C, C-8), 67.6 (s, 1C, C-7), 62.7 (s, 1C, C-9), 59.6 (d, 1C, J5,F3 = 8 Hz, C-5); 19F NMR (376 MHz, D2O) δ −112.26 (t, J = 13.5 Hz), −200.37 (ddd, J = 49.2, 14.7, 3.0 Hz); HRMS (ESI-Orbitrap) m/z: [M – H]− Calcd for C9H12F2N3O7 312.0649; found 312.0635.

Synthesis of 5-glycolamido-2,3,5-trideoxy-3-fluoro-D-erythro-α-L-gluco-non-2-ulopyranosylonic fluoride (2e3eDFNeu5Gc, 4). To a solution of compound 3 (150 mg, 0.48 mmol) in CH3OH: Water (5 mL, 1:1 v/v), 20% Pd(OH)2/C (40 mg) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature under a positive pressure of hydrogen for 5 h. The reaction mixture was filtered through a Celite® bed and evaporated to dryness. The intermediate amine was dried in vacuo for 12–14 h and directly used for the next step without further purification.

The amine intermediate (134.5 mg, 0.47 mmol) was dissolved in CH3CN-H2O (4 mL, 1:1, v/v). Then solid NaHCO3 (390 mg, 4.7 mmol) and acetoxyacetyl chloride (252 μL, 2.35 mmol) in CH3CN (1 mL) were added. The reaction mixture was stirred for 3 hours at 0 °C and neutralized by adding acetic acid, concentrated, and purified by Bio-Gel-P2. Compound-containing fractions were combined and dried. The dried compound was dissolved in MeOH (4 mL) and NaOMe (200 μL, 5.4 N in MeOH) was added drop wisely at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 hours. The reaction mixture was neutralized by adding ion exchange resin Amberlite® IR-120H, concentrated and purified using a C18 column on a CombiFlashRf 200i system eluted with a gradient of 0–100% acetonitrile in water. The fractions containing the desired product were collected, combined, and lyophilized to produce compound 4 as a white powder. The product (142.2 mg, 88%) was further purified by HPLC (C18 column and water and acetonitrile as solvent) and lyophilized. 1H NMR (800 MHz, D2O) δ 4.70–4.58 (m, 1H), 4.48 (dt, J = 17.6, 9.6 Hz, 1H), 4.39 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 1H), 4.27 (t, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 4.12 (s, 2H), 3.79 (dd, J = 12.0, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 3.76–3.70 (m, 1H), 3.58 (dd, J = 12.0, 6.4 Hz, 1H), 3.48 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H); 13C{H} NMR (200 MHz, D2O) δ 175.2 (s, 1C, C=O), 168.4 (d, 1C, J1,F2 = 32 Hz, C-1), 107.1 (dd, 1C, J2,F = 220 Hz, J2,F3 = 28 Hz, C-2), 93.2 (dd, 1C, J3,F3 = 184 Hz, J3,F2 = 30 Hz, C-3), 69.4 (s, 1C, C-8), 72.9 (s,1C, C-6), 70.0 (dd, 1C, J4,F3 = 20 Hz, J4,F2 = 8 Hz, C-4), 67.2 (s, 1C, C-7), 62.6 (s, 1C, C-9), 60.5 (s, 1C, NHCH2OH), 48.8 (d, 1C, J5,F3 = 8 Hz, C-5); 19F NMR (376 MHz, D2O) δ: −112.8 (t, J = 13.7 Hz), −200.9 (ddd, J = 49.6, 14.8, 2.6 Hz); HRMS (ESI-Orbitrap) m/z: [M – H]− Calcd for C11H16F2NO9 344.0799; found 344.0792.

Inhibition Assay. Percentage Inhibition assays were carried out in duplicates in a 384-well plate similar to that reported previously.24 All reactions had a final volume of 20 μL containing Neu5Acα2–3GalβpNP (0.3 mM) and β-galactosidase (12 μg) with 0.1 mM or 1.0 mM of inhibitor. The assay conditions for various sialidases were as follows: A. ureafaciens sialidase (0.5 mU), NaOAc buffer (100 mM, pH 5.5); C. perfringens sialidase (CpNanI, 1.3 mU), MES buffer (100 mM, pH 5.0); V. cholera sialidase (0.6 mU), NaCl (150 mM), CaCl2 (10 mM), NaOAc buffer (100 mM, pH 5.5); SpNanA (0.75 ng), NaOAc buffer (100 mM, pH 6.0); SpNanB (3 ng), NaOAc buffer (100 mM, pH 6.0); SpNanC (10 ng), MES buffer (100 mM, pH 6.5); PmST1 (0.2 μg), NaOAc buffer (100 mM, pH 5.5), CMP (0.4 mM); hNEU2 (0.6 μg), MES buffer (100 mM, pH 5.0); BiNanH2 (4 ng), NaOAc buffer (100 mM, pH 5.0). The reactions were carried out for 30 minutes and quenched with 40 μL of N-cyclohexyl-3-aminopropane sulfonic acid (CAPS) buffer (0.5 M, pH 10.5). The concentrations of p-nitrophenolate formed was determined by measuring A405 nm of the reaction mixtures using a microplate reader.

Inhibition assays for obtaining IC50 values were carried out in duplicates in a 384-well plate similarly as described above except that twelve different concentrations of inhibitors in the range of 0 to 10 mM were used (varied from 10 mM, 5 mM, 2.5 mM, 1 mM, 0.5 mM, 0.1 mM, 50 μM, 25 μM, 10 μM, 5 μM, 2.5 μM, 1 μM, 0.5 μM, 0.1 μM, 50 nM, 10 nM, 5 nM, and 0 nM). IC50 values were obtained by fitting the average values to get the concentration-response plots using software Grafit 5.0.

Time course study for sialidase re-activation in the presence of a covalent inhibitor. This study was carried out in duplicates in a 384-well plate by incubating an inhibitor selected from difluorosialic acids and derivatives (1–6) and a sialidase in a 2:1 molar ratio in the presence of NaOAc buffer (100 mM, pH 6.0) with (for V. cholera sialidase) or without (for all other sialidases) CaCl2 (10 mM) and NaCl (150 mM) at room temperature (23 °C). At different time intervals (2 min – 24 hours or for up to 5 days), an aliquot (12 μL) of each pre-incubated inhibitor-sialidase mixture was assayed for sialidase activity using Neu5Acα2–3GalβpNP (2 mM) as the substrate in the presence of an excess amount of β-galactosidase (12 μg). BioTek Synergy HT plate reader was used for continuous reading of the formation of para-nitrophenol (pNP). The absorbance change rates (A400 nm min−1) were recorded and used for plotting Figure 2. The amounts of enzymes used were: C. perfringens sialidase (CpNanI, 2.0 μg), V. cholera sialidase (0.25 μg), BiNanH2 (0.10 μg), SpNanA (18 ng), hNEU2 (1.75 μg).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partially supported by United States National Institutes of Health grants R01AI130684 and R43AI108115. Bruker Avance-800 NMR spectrometer was funded by United States National Science Foundation grant DBIO-722538.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Sialidase inhibition IC50 plots for compounds 1–6 (Figure S1), time course study results for sialidase deactivation and reactivation in the presence or the absence of a covalent inhibitor (1 or 3–5) (Figure S2), and NMR spectra of compounds (1–6 and 11–13) (PDF).

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Varki A Sialic Acids in Human Health and Disease. Trends. Mol. Med 2008, 14, 351–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Chen X; Varki A Advances in the Biology and Chemistry of Sialic Acids. ACS Chem. Biol 2010, 5, 163–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Li Y; Chen X Sialic Acid Metabolism and Sialyltransferases: Natural Functions and Applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2012, 94, 887–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Taylor G Sialidases: Structures, Biological Significance and Therapeutic Potential. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 1996, 6, 830–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Vimr ER; Kalivoda KA; Deszo EL; Steenbergen SM Diversity of Microbial Sialic Acid Metabolism. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev 2004, 68, 132–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Gallego MP; Hulen C Influence of Sialic Acid and Bacterial Sialidase on Differential Adhesion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to Epithelial Cells. Colloids Surf. B. Biointerfaces 2006, 52, 154–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Honma K; Mishima E; Sharma A Role of Tannerella forsythia NanH Sialidase in Epithelial Cell Attachment. Infect. Immun 2011, 79, 393–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).King S Pneumococcal Modification of Host Sugars: a Major Contributor to Colonization of the Human Airway? Mol. Oral. Microbiol 2010, 25, 15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Li J; Sayeed S; Robertson S; Chen J; McClane BA Sialidases Affect the Host Cell Adherence and Epsilon Toxin-Induced Cytotoxicity of Clostridium perfringens type D Strain CN3718. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Gualdi L; Hayre JK; Gerlini A; Bidossi A; Colomba L; Trappetti C; Pozzi G; Docquier JD; Andrew P; Ricci S; Oggioni MR Regulation of Neuraminidase Expression in Streptococcus pneumoniae. BMC Microbiol. 2012, 12, 200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Roy S; Douglas CW; Stafford GP A Novel Sialic Acid Utilization and Uptake System in the Periodontal Pathogen Tannerella forsythia. J. Bacteriol 2010, 192, 2285–93.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Corfield T Bacterial Sialidases—Roles in Pathogenicity and Nutrition. Glycobiology 1992, 2, 509–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Brear P; Telford J; Taylor GL; Westwood NJ Synthesis and Structural Characterisation of Selective Non-Carbohydrate-Based Inhibitors of Bacterial Sialidases. ChemBioChem 2012, 13, 2374–2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Li J; McClane BA The sialidases of Clostridium perfringens Type D Strain CN3718 Differ in Their Properties and Sensitivities to Inhibitors. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2014, 80, 1701–1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).von Itzstein M; Wu WY; Kok GB; Pegg MS; Dyason JC; Jin B; Van Phan T; Smythe ML; White HF; Oliver SW; et al. Rational Design of Potent Sialidase-Based Inhibitors of Influenza Virus Replication. Nature 1993, 363, 418–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Kim CU; Lew W; Williams MA; Liu H; Zhang L; Swaminathan S; Bischofberger N; Chen MS; Mendel DB; Tai CY; Laver WG; Stevens RC Influenza Neuraminidase Inhibitors Possessing a Novel Hydrophobic Interaction in the Enzyme Active Site: Design, Synthesis, and Structural Analysis of Carbocyclic Sialic Acid Analogues with Potent Anti-Influenza Activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1997, 119, 681–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).von Itzstein M The War Against Influenza: Discovery and Development of Sialidase Inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov 2007, 6, 967–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Laborda P; Wang SY; Voglmeir J Influenza Neuraminidase Inhibitors: Synthetic Approaches, Derivatives and Biological Activity. Molecules 2016, 21, pii: E1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Babu YS; Chand P; Bantia S; Kotian P; Dehghani A; El-Kattan Y; Lin TH; Hutchison TL; Elliott AJ; Parker CD; Ananth SL; Horn LL; Laver GW; Montgomery JA BCX-1812 (RWJ-270201): Discovery of A Novel, Highly Potent, Orally Active, and Selective Influenza Neuraminidase Inhibitor Through Structure-Based Drug Design. J. Med. Chem 2000, 43, 3482–3486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Wester A; Shetty AK Peramivir Injection in The Treatment of Acute Influenza: A Review of The Literature. Infect. Drug Resist 2016, 9, 201–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Yamashita M Laninamivir and Its Prodrug, CS-8958: Long-Acting Neuraminidase Inhibitors for The Treatment of Influenza. Antiviral Chem. Chemother 2010, 21, 71–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Ramos EL; Mitcham JL; Koller TD; Bonavia A; Usner DW; Balaratnam G; Fredlund P; Swiderek KM Efficacy and Safety of Treatment with An Anti-m2e Monoclonal Antibody in Experimental Human Influenza. J. Infect. Dis 2014, 211, 1038–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Glanz VY; Myasoedova VA; Grechko AV; Orekhov AN Inhibition of Sialidase Activity as A Therapeutic Approach. Drug. Des. Devel. Ther 2018, 12, 3431–3437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Slack TJ; Li W; Shi D; McArthur JB; Zhao G; Li Y; Xiao A; Khedri Z; Yu H; Liu Y Triazole-Linked Transition State Analogs as Selective Inhibitors Against V. cholerae Sialidase. Bioorganic Med. Chem 2018, 26, 5751–5757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Xiao A; Slack TJ; Li Y; Shi D; Yu H; Li W; Liu Y; Chen X Streptococcus pneumoniae Sialidase SpNanB-Catalyzed One-Pot Multienzyme (OPME) Synthesis of 2,7-Anhydro-Sialic Acids as Selective Sialidase Inhibitors. J. Org. Chem 2018, 83, 10798–10804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Khedri Z; Li Y; Cao H; Qu J; Yu H; Muthana MM; Chen X Synthesis of Selective Inhibitors against V. cholerae Sialidase and Human Cytosolic Sialidase NEU2. Org. Biomol. Chem 2012,10, 6112–6120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Chen GY; Chen X; King S; Cavassani KA; Cheng J; Zheng X; Cao H; Yu H; Qu J; Fang D; Wu W; Bai XF; Liu JQ; Woodiga SA; Chen C; Sun L; Hogaboam CM; Kunkel SL; Zheng P; Liu Y Amelioration of Sepsis by Inhibiting Sialidase-Mediated Disruption of the CD24-SiglecG Interaction. Nat. Biotechnol 2011, 29, 428–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Xu G; Li X; Andrew PW; Taylor GL Structure of The Catalytic Domain of Streptococcus pneumoniae Sialidase NanA. Acta. Crystallogr. Sect. F. Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun 2008, 64, 772–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).von Itzstein M Disease-Associated Carbohydrate-Recognising Proteins and Structure-Based Inhibitor Design. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 2008, 18, 558–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Vavricka CJ; Muto C; Hasunuma T; Kimura Y; Araki M; Wu Y; Gao GF; Ohrui H; Izumi M; Kiyota H Synthesis of Sulfo-Sialic Acid Analogues: Potent Neuraminidase Inhibitors in Regards to Anomeric Functionality. Sci. Rep 2017, 7, 8239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Watts AG; Withers SG The Synthesis of Some Mechanistic Probes for Sialic Acid Processing Enzymes and The Labeling of A Sialidase from Trypanosoma rangeli. Can. J. Chem 2004, 82, 1581–1588. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Buchini S; Buschiazzo A; Withers SG A New Generation of Specific Trypanosoma cruzi Trans-Sialidase Inhibitors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2008, 47, 2700–2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Buchini S; Gallat FX; Greig IR; Kim JH; Wakatsuki S; Chavas LM; Withers SG Tuning Mechanism-Based Inactivators of Neuraminidases: Mechanistic and Structural Insights. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2014, 53, 3382–3386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Kim J-H; Resende R; Wennekes T; Chen H-M; Bance N; Buchini S; Watts AG; Pilling P; Streltsov VA; Petric M Mechanism-Based Covalent Neuraminidase Inhibitors with Broad-Spectrum Influenza Antiviral Activity. Science 2013, 340, 71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Delbrouck JA; Chêne LP; Vincent SP, Fluorosugars as Inhibitors of Bacterial Enzymes. In Fluorine in Life Sciences: Pharmaceuticals, Medicinal Diagnostics, and Agrochemicals, Elsevier: 2019; pp 241–279. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Withers S; Rupitz K; Street I 2-Deoxy-2-fluoro-D-glycosyl fluorides. A New Class of Specific Mechanism-Based Glycosidase Inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem 1988, 263, 7929–7932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Amaya MF; Watts AG; Damager I; Wehenkel A; Nguyen T; Buschiazzo A; Paris G; Frasch AC; Withers SG; Alzari PM Structural Insights into the Catalytic Mechanism of Trypanosoma cruzi Trans-Sialidase. Structure 2004, 12, 775–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Watts AG; Oppezzo P; Withers SG; Alzari PM; Buschiazzo A Structural and Kinetic Analysis of Two Covalent Sialosyl-Enzyme Intermediates on Trypanosoma rangeli Sialidase. J. Biol. Chem 2006, 281, 4149–4155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Newstead SL; Potter JA; Wilson JC; Xu G; Chien CH; Watts AG; Withers SG; Taylor GL The Structure of Clostridium perfringens NanI Sialidase and Its Catalytic Intermediates. J. Biol. Chem 2008, 283, 9080–9088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Li Y; Cao H; Yu H; Chen Y; Lau K; Qu J; Thon V; Sugiarto G; Chen X Identifying Selective Inhibitors Against The Human Cytosolic Sialidase NEU2 by Substrate Specificity Studies. Mol. Biosyst 2011, 7, 1060–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Chokhawala HA; Cao H; Yu H; Chen X Enzymatic Synthesis of Fluorinated Mechanistic Probes for Sialidases and Sialyltransferases. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 10630–10631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Li Y; Yu H; Cao H; Lau K; Muthana S; Tiwari VK; Son B; Chen X Pasteurella multocida Sialic Acid Aldolase: A Promising Biocatalyst. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2008, 79, 963–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Yu H; Yu H; Karpel R; Chen X Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of CMP-Sialic Acid Derivatives by A One-Pot Two-Enzyme System: Comparison of Substrate Flexibility of Three Microbial CMP-Sialic Acid Synthetases. Bioorg. Med. Chem 2004, 12, 6427–6435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Yu H; Chokhawala H; Karpel R; Yu H; Wu B; Zhang J; Zhang Y; Jia Q; Chen X A Multifunctional Pasteurella multocida Sialyltransferase: A Powerful Tool for The Synthesis of Sialoside Libraries. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 17618–17619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Cao H; Li Y; Lau K; Muthana S; Yu H; Cheng J; Chokhawala HA; Sugiarto G; Zhang L; Chen X Sialidase Substrate Specificity Studies Using Chemoenzymatically Synthesized Sialosides Containing C5-Modified Sialic Acids. Org. Biomol. Chem 2009, 7, 5137–5145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Alper PB; Hung S-C; Wong C-H Metal Catalyzed Diazo Transfer for The Synthesis of Azides from Amines. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 6029–6032. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Xiao A; Li Y; Li X; Santra A; Yu H; Li W; Chen X Sialidase-Catalyzed One-Pot Multienzyme (OPME) Synthesis of Sialidase Transition-State Analogue Inhibitors. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 43–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Tasnima N; Yu H; Li Y; Santra A; Chen X Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of para-Nitrophenol (pNP)-Tagged alpha2–8-Sialosides and High-Throughput Substrate Specificity Studies of alpha2–8-Sialidases. Org. Biomol. Chem 2016, 15, 160–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Owen CD; Lukacik P; Potter JA; Sleator O; Taylor GL; Walsh MA Streptococcus pneumoniae NanC: Structural Insights into The Specificity and Mechanism of A Sialidase That Produces A Sialidase Inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem 2015, 290, 27736–27748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Xu G; Kiefel MJ; Wilson JC; Andrew PW; Oggioni MR; Taylor GL Three Streptococcus pneumoniae Sialidases: Three Different Products. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 1718–1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Sela DA; Li Y; Lerno L; Wu S; Marcobal AM; German JB; Chen X; Lebrilla CB; Mills DA An Infant-Associated Bacterial Commensal Utilizes Breast Milk Sialyloligosaccharides. J. Biol. Chem 2011, 286, 11909–11918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Chokhawala HA; Yu H; Chen X High-Throughput Substrate Specificity Studies of Sialidases by Using Chemoenzymatically Synthesized Sialoside Libraries. Chembiochem. 2007, 8, 194–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Mehr K; Withers SG Mechanisms of The Sialidase and Trans-Sialidase Activities of Bacterial Sialyltransferases from Glycosyltransferase Family 80. Glycobiology. 2016, 26, 353–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).McArthur JB; Yu H; Tasnima N; Lee CM; Fisher AJ; Chen X alpha2–6-Neosialidase: A Sialyltransferase Mutant as a Sialyl Linkage-Specific Sialidase. ACS. Chem. Biol 2018, 13, 1228–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Mann MC; Thomson RJ; Dyason JC; McAtamney S; von Itzstein M Modelling, Synthesis And Biological Evaluation of Novel Glucuronide-Based Probes of Vibrio cholerae Sialidase. Bioorg. Med. Chem 2006, 14, 1518–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Navarro MA; Li J; McClane BA; Morrell E; Beingesser J; Uzal FA NanI Sialidase Is an Important Contributor to Clostridium perfringens Type F Strain F4969 Intestinal Colonization in Mice. Infect. Immun 2018, 86, pii: e00462–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Mehdizadeh Gohari I; Brefo-Mensah EK; Palmer M; Boerlin P; Prescott JF Sialic Acid Facilitates Binding And Cytotoxic Activity of The Pore-Forming Clostridium perfringens NetF Toxin to Host Cells. PLoS One. 2018, 13, e0206815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.