Abstract

Background

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is increasingly performed in younger patients despite the lack of comprehensive assessment of long-term outcomes. We systematically reviewed the contemporary literature to assess the 1) indications, 2) implant selection and long-term survivorship, 3) complication and reoperation rates and 4) radiographic and functional outcomes of primary THA in patients younger than 55 years.

Methods

We searched the Embase and MEDLINE databases for English-language articles published between 2000 and 2018 that reported outcomes of primary THA in patients younger than 55 years with a minimum follow-up duration of 10 years.

Results

Thirty-two studies reporting on 3219 THA procedures performed in 2434 patients met our inclusion criteria. The most common preoperative diagnoses were avascular necrosis (1044 [32.4%]), osteoarthritis (870 [27.0%]) and developmental dysplasia of the hip (627 [19.5%]). Modular implants (3001 [93.2%]), cementless fixation (2214 [68.8%]) and metal-on-polyethylene bearings (1792 [55.7%]) were frequently used. The mean 5- and 10-year survival rates were 98.7% and 94.6%, respectively. Data on survival beyond 10 years were heterogeneous, with values of 27%–99.5% at 10–14 years, 59%–84% at 15–19 years, 70%–77% at 20–24 years and 60% at 25–30 years. Rates of dislocation, deep infection and reoperation for any reason were 2.4%, 1.2% and 16.3%, respectively. The mean Harris Hip Score improved from 43.6/100 to 91.0/100.

Conclusion

Total hip arthroplasty in patients younger than 55 years provides reliable outcomes at up to 10 years. Future studies should evaluate the outcomes of THA in this population at 15–20 years’ follow-up.

Abstract

Contexte

On effectue de plus en plus d’arthroplasties totales de la hanche (ATH) chez des patients qui ne sont pas âgés, malgré l’absence d’évaluation exhaustive des issues à long terme. Nous avons procédé à une revue systématique de la littérature récente pour analyser 1) les indications, 2) la sélection des implants et la survie à long terme, 3) les taux de complications et de réintervention, et 4) les résultats radiographiques et fonctionnels des ATH primaires chez les patients de moins de 55 ans.

Méthodes

Nous avons interrogé les bases de données Embase et MEDLINE pour recenser les articles de langue anglaise publiés entre 2000 et 2018 qui faisaient état des issues d’ATH primaires chez des patients de moins de 55 ans suivis pendant au moins 10 ans.

Résultats

Trente-deux études portant sur 3219 ATH effectuées chez 2434 patients répondaient à nos critères d’inclusion. Les diagnostics préopératoires les plus fréquents étaient la nécrose avasculaire (1044 [32,4 %]), l’arthrose (870 [27,0 %]) et la dysplasie développementale de la hanche (627 [19,5 %]). Les implants modulaires (3001 [93,2 %]), la fixation non cimentée (2214 [68,8 %]) et le couple métal–polyéthylène (1792 [55,7 %]) ont été fréquemment utilisés. Les taux de survie moyens à 5 et à 10 ans étaient de 98,7 % et de 94,6 %, respectivement. Les données sur la survie au-delà de 10 ans étaient hétérogènes, allant de 27 % à 99,5 % après 10 à 14 ans, de 59 % à 84 % après 15 à 19 ans, de 70 % à 77 % après 20 à 24 ans et de 60 % après 25 à 30 ans. Les taux de dislocation, d’infection profonde et de réintervention, toutes causes confondues, étaient de 2,4 %, de 1,2 % et de 16,3 %, respectivement. Le score de Harris moyen s’est amélioré, passant de 43,6/100 à 91,0/100.

Conclusion

L’arthroplastie totale de la hanche chez les patients de moins de 55 ans donne des résultats fiables pour les 10 premières années après l’intervention. Les prochaines études devraient évaluer les issues de l’arthroplastie de la hanche dans cette population après 15 à 20 ans de suivi.

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) reliably decreases pain and improves function and quality of life in patients with advanced hip disease at up to 25–30 years of follow-up.1,2 Despite early concerns over prosthetic longevity in patients with higher activity levels, improvements in implant design and surgical technique have led to increased demand for THA in younger, active patients.3,4 Kurtz and colleagues3 reviewed the American National Inpatient Sample database from 2006 and reported the proportion of primary THA procedures performed annually in patients younger than 55 years to be about 21%, with a projected rise to 28% by 2030. This proportion is slightly lower outside the United States, with rates of 11.9%, 6.4% and 13.2% reported by the 2014 Canadian,5 United Kingdom6 and Australian7 joint replacement registries, respectively.

Earlier studies showed high revision rates following Charnley low-friction arthroplasty in younger patients compared to older cohorts,8–10 with the main modes of failure being aseptic loosening and wear-induced osteolysis.11,12 Inferior implant survival in younger patients has been attributed to higher activity levels as well as a higher proportion of patients with inflammatory arthritis and congenital hip disease as their preoperative diagnosis.13 Despite these challenges, recent innovations including cementless fixation and alternative bearing surfaces have shown considerable promise in addressing many previous limitations of THA in younger patients.

Given these technological advances, we performed a systematic review of the contemporary literature with the aim of assessing the 1) indications, 2) implant selection and long-term survivorship, 3) rates of complication and reoperation and 4) radiographic and functional outcomes of primary THA in patients younger than 55 years of age.

Methods

Literature search and study selection

We performed a literature search according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Eligible studies were identified through a systematic search of MEDLINE and Embase databases from inception to April 2018. Database search terms included “total hip arthroplasty,” “total hip replacement,” “younger than 55,” “younger than 50,” “younger than 40,” “younger than 30,” “less than 55,” “less than 50,” “less than 40,” “less than 30” and “young patient.” We reviewed the bibliographies of all retrieved studies for relevant articles.

Two authors (X.Y.M. and Y.J.G.) independently screened the titles and abstracts of articles identified through the search strategy for eligibility. The predetermined inclusion criteria were 1) reporting of primary THA outcomes, 2) series of at least 20 patients, 3) mean follow-up of at least 10 years, 4) all patients younger than 55 years at the time of surgery and 5) reporting of implant selection and survivorship, complications and functional outcomes. Articles were restricted to those that were published in full and written in English. Studies were excluded if they 1) were published before 2000, 2) were conference abstracts, case reports, reviews or surgical technique articles, 3) did not adequately report implant selection and survivorship or 4) reported outcomes of hemiarthroplasty, hip resurfacing, metal-on-metal bearings or revision THA. When multiple studies reported on the same study population, the article with the longest follow-up duration was selected, and the other studies were removed. Studies that passed the initial title and abstract screening were reviewed in full with the use of the same eligibility criteria. Any disagreement between authors was resolved by consensus.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two authors (X.Y.M. and Y.J.G.) independently extracted the relevant data from each study and recorded them in an Excel document. Data collected included study design and period; patient age, sex and body mass index; mean follow-up duration and proportion of patients lost to follow-up; preoperative diagnosis and surgical approach; and implant selection, type of fixation and bearing surface. Outcome measures included implant survivorship at 5 years, 10 years and final follow-up; rates of dislocation, deep infection, other complications and reoperation; radiographic assessment; and functional outcome scores. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus.

Two authors (X.Y.M. and Y.J.G.) independently assessed the methodological quality of eligible studies. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials14 was used for randomized controlled trials, and the Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORS) was used for nonrandomized studies.15 Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration) was used to construct the risk of bias summary. Any disagreement between reviewers was resolved by consensus. Agreement between reviewers on individual MINORS items was measured with the Cohen κ.16

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize patient demographic characteristics, implant selection and outcome measures. We calculated weighted means for all interval and ratio data. Stratification by implant fixation was not performed owing to inconsistent reporting of outcomes and the small number of studies using cemented and hybrid fixation. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We performed all statistical analysis using SPSS version 24.0 software (IBM Corp.).

Results

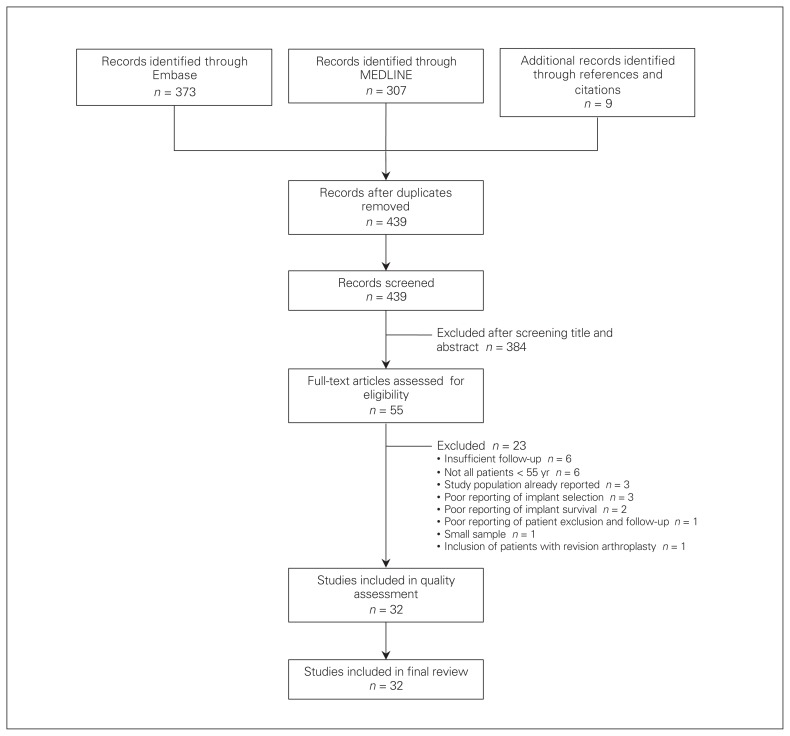

The initial search yielded 435 potentially relevant articles after exclusion of duplicates (Fig. 1). After review of the titles and abstracts, 384 articles were excluded. Twenty-three additional articles were excluded after full-text review, leaving 32 articles eligible for inclusion in the systematic review.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram showing study selection.

Patient demographic characteristics

A total of 3219 primary THA procedures performed in 2434 patients between 1969 and 2006 were included. The year of surgery was 1970–1980 for 171 hips (5.3%), 1980–1990 for 650 (20.2%), 1990–2000 for 1044 (32.4%) and after 2000 for 495 (15.4%); 9 studies reporting on 859 procedures (26.7%) had dates of surgery spanning more than 1 decade and thus could not be sorted into these intervals. A total of 777 procedures (24.1%) were performed after 1985. Of the 2434 patients, 1144 (47.0%) (standard deviation [SD] 17.2, range 20.5–85.7) were women. The mean age was 42.0 years (SD 7.4 yr, range 17.9–52.5 yr), and the mean body mass index was 26.6 (SD 2.7, range 22–29.6). The mean follow-up duration was 15.5 years (SD 5.9 yr, range 10–28.4 yr); 185 patients (7.6% [SD 8.1, range 0–39.1]) were lost to follow-up. The most common preoperative diagnoses were avascular necrosis (1044 cases [32.4%]), primary/secondary osteoarthritis (870 [27.0%]) and developmental dysplasia of the hip (627 [19.5%]) (Table 1). A summary of the patient demographic characteristics is presented in Table 2, with full details available in Appendix 1 (available at canjsurg.ca/013118-a1).

Table 1.

Preoperative diagnosis in patients younger than 55 years of age who underwent total hip arthroplasty

| Diagnosis | No. (%) of hips n = 3219 |

|---|---|

| Avascular necrosis | 1044 (32.4) |

| Osteoarthritis (primary/secondary) | 870 (27.0) |

| Developmental dysplasia of hip | 627 (19.5) |

| Inflammatory arthropathy | 267 (8.3) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 92 (2.9) |

| Unclassified inflammatory arthropathy | 70 (2.2) |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 58 (1.8) |

| Juvenile idiopathic arthritis | 47 (1.5) |

| Post trauma | 105 (3.3) |

| Congenital dislocation of hip | 39 (1.2) |

| Slipped capital femoral epiphysis | 36 (1.1) |

| Tumour | 33 (1.0) |

| Legg–Calvé–Perthes disease | 32 (1.0) |

| Septic arthritis | 21 (0.6) |

| Osteochondritis dissecans | 16 (0.5) |

| Still disease | 2 (0.1) |

| Other/not reported | 127 (3.9) |

Table 2.

Summary of patient demographic characteristics, implant selection, survivorship and outcomes

| Study | No. of patients | No. of hips | Age, yr, mean (range) | Length of follow-up, yr, mean (range) | Implant fixation | Bearing surface | Implant survival, % | Outcome; no. (%) of hips | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| 5 yr | 10 yr | Final | Dislocation | Deep infection | Reoperation | |||||||

| Choi et al.,27 2017 | 17 | 20 | 36.2 (21–40) | 11 (10–13.5) | Cementless, hybrid | Metal-on-HXLPE | 95 | 95 | 95 (11 yr) | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.0) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Philippot et al.,39 2017 | 114 | 137 | 41 (18–50) | 21.9 (3.3–30.9) | Cementless | MoP | NR | NR | 77 (21.9 yr) | 15 (10.9) (intra-prosthetic) | 1 (0.7) | 44 (32.1) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Schmoulders et al.,41 2017 | 77 | 81 | 48 (30–50) | 13.5 (9.7–16.9) | Cementless | CoP | NR | 96.8 | 93 (13.5 yr) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (7.4) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Stambough et al.,44 2016 | 72 | 75 | 41.2 (17–50) | 10 (8.2–11.9) | Cementless | Metal-on-HXLPE | 96 | 92 | 92 (10 yr) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) | 5 (6.7) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Kim et al.,18 2016 | 200 | 400 | 52.5 (26–54) | 11.8 (10–13) | Cementless | CoC | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.5 (11.8 yr) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.5) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Kim et al.,19 2016 | 171 | 342 | 48 (21–50) | 26.1 (25–27) | Hybrid, cementless | MoP | NR | NR | 78.5 cup, 95.5 stem (26.1 yr) | 5 (1.5) | 1 (0.3) | 73 (21.3) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| McLaughlin et al.,37 2016 | 67 | 82 | 36.4 (20–49) | 25 (20–29) | Cementless | MoP | NR | NR | 90 stem (27 yr) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.7) | 9 (11.0) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Kim et al.,35 2014 | 70 | 88 | 45.6 (19–49) | 28.4 (27–29) | Cementless | MoP | NR | NR | 66 cup, 90 stem (28.4 yr) | 2 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 39 (44.3) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Babovic et al.,21 2013 | 50 | 54 | 38.9 (15–50) | 10.4 (NR) | Cementless | Metal-on-HXLPE 52, ceramic-on-HXLPE 2 | NR | NR | 98.1 (10.4 yr) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Chana et al.,25 2013 | 100 | 110 | 45.8 (20–55) | 11.5 (10–13.5) | Cementless | CoC | NR | 96.5 | 96.5 (11.5 yr) | 1 (0.9) (late traumatic) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.6) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Schmitz et al.,40 2013 | 48 | 69 | 25 (16–29) | 11.5 (7–23) | Cemented | MoP | NR | 86 | 75 (15 yr) | 2 (2.9) | 4 (5.8) | 16 (23.2) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Yoon et al.,48 2012 | 62 | 75 | 24 (18–30) | 11.4 (10–13.4) | Cementless | CoC | NR | 98.9 | 98.9 (10 yr) | 1 (1.3) (with fractured liner) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.3) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Biemond et al.,22 2011 | 80 | 93 | 44 (16–50) | 12.3 (9.8–15.5) | Cementless | MoP | NR | 84 | 84 (12.3 yr) | 6 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (18.3) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Faldini et al.,30 2011 | 28 | 34 | 47 (44–50) | 12 (10–14) | Cementless | MoP 27, CoC 7 | 100 | 100 | 100 (12 yr) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Hsu et al.,33 2011 | 62 | 80 | 38.6 (16–49) | 10.1 (10–12.3) | Hybrid | CoC | NR | 96.3 | 96.3 (10 yr) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.8) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Kim et al.,17 2011 | 78 | 109 | 43.4 (21–50) | 18.4 (17–19) | Hybrid, cementless | MoP | NR | 93.6 | 85.5 (20 yr) | 3 (1.4) | 3 (1.4) | 38 (17.4) |

| 79 | 110 | 46.8 (21–49) | 18.4 (16–19) | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Pakvis et al.,38 2011 | 131 | 158 | 42 (18–50) | 13.2 (10–18) | Cementless | CoP 100, MoP 58 | NR | 98 | 80 (14 yr) | 7 (4.4) | 3 (1.9) | 39 (24.7) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Boyer et al.,23 2010 | 69 | 76 | 39 (NR) | 10 (7–15) | Hybrid, cementless | CoC | NR | 92 | 92 (10 yr) | 3 (3.9) | 1 (1.3) | 5 (6.6) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Burston et al.,24 2010 | 44 | 54 | 39.5 (18–50) | 12.5 (10–17) | Cemented, hybrid | MoP | NR | NR | 79.2 (12.5 yr | 4 (7.1) | 2 (3.6) | 14 (25.0) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Flecher et al.,31 2010 | 212 | 233 | 42.6 (20–50) | 10 (5–16) | Cementless | CoP | NR | 96.7 | 87 (15 yr) | 6 (2.6) | 4 (1.7) | 23 (9.9) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Wrobelewski et al.,47 2010 | 26 | 35 | 17.9 (12–19) | 15.6 (2.3–34) | Cemented | MoP 25, CoP 10 | NR | NR | 59 (15.6 yr) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) | 16 (45.7) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Akbar et al.,20 2009 | 59 | 70 | 35 (22–40) | 14 (10–16) | Cementless | CoP | 100 | 100 | 86 (14 yr) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (7.1) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Lewthwaite et al.,36 2008 | 101 | 123 | 42 (NR) | 12.5 (10–17) | Cemented | MoP | NR | 94.4 | 92.6 (12.5 yr) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.8) | 13 (10.6) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Utting et al.,45 2008 | 53 | 70 | 40 (19–49) | 13.6 (12–16) | Hybrid | MoP | NR | NR | 84 cup/liner (stem NR) (16 yr) | 2 (2.9) | 1 (1.4) | 13 (18.6) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Wangen et al.,46 2008 | 42 | 47 | 25 (15–30) | 13 (10–16) | Cementless | MoP | NR | NR | 51 (13 yr) | 3 (6.4) | 0 (0.0) | 24 (51.1) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Singh et al.,42 2004 | 33 | 38 | 42 (22–49) | 10 (5.3–14.2) | Hybrid, cementless | CoP 36, MoP 2 | NR | NR | 90.5 cemented cup, 96 cementless cup, 100 stem (12 yr) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (10.5) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Keener et al.,34 2003 | 42 | 57 | 42 (18–49) | 25.7 (25–30) | Cemented | MoP | NR | NR | 60 (30 yr) | 1 (1.8) | 4 (7.0) | 22 (38.6) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Crowther et al.,28 2002 | 44 | 56 | 37 (22–49) | 11 (9–14) | Cementless | MoP | NR | NR | 87.5 (11 yr) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) | 7 (12.5) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Chiu et al.,26 2001 | 33 | 47 | 28.8 (17–39) | 14.9 (6.9–21.1) | Cemented | MoP | 97.8 | 84.5 | 27 (15 yr) | 2 (4.3) | 1 (2.1) | 30 (63.8) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Duffy et al.,29 2001 | 72 | 82 | 32 (17–39) | 10.3 (10–14) | Cementless | MoP | 96.3 | 78.1 | 78.1 (10 yr) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.4) | 26 (31.7) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Garcia-Cimbrelo et al.,32 2000 | 58 | 67 | 32.4 (18–39) | 21.7 (5–25) | Cemented | MoP | 98.5 | 88 | 70 (24 yr) | 3 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | 19 (28.4) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Smith et al.,43 2000 | 40 | 47 | 41 (21–50) | 18.2 (17–20) | Cemented | MoP | NR | 96.8 | 96.8 (10 yr) | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (12.8) |

CoC = ceramic-on-ceramic; CoP = ceramic-on-conventional-polyethylene; HXLPE = highly cross-linked polyethylene; MoP = metal-on-conventional-polyethylene; NR = not reported.

Surgical technique and implant selection

A variety of surgical approaches including anterolateral, posterolateral, posterior and transtrochanteric were used. Modular implants were used in 3001 hips (93.2%) and monoblock implants in 218 (6.8%). Implant fixation was cementless in 2214 hips (68.8%), hybrid in 540 (16.8%) and cemented in 465 (14.4%). Among the 2399 cementless femoral stems described, the fixation design was metaphyseal-fitting in 1544 cases (64.4%), metaphyseal–diaphyseal-junction-fitting in 366 (15.3%), diaphyseal-fitting in 223 (9.3%) and screwed into the femoral canal in 137 (5.7%); the fixation design was not reported in 129 cases (5.4%). The bearing surface used was metal-on-conventional-polyethylene in 1792 hips (55.7%), ceramic-on-ceramic in 748 (23.2%), ceramic-onconventional-polyethylene in 530 (16.5%), metal-on-highlycross-linked polyethylene in 147 (4.6%) and ceramic-on-highly-cross-linked polyethylene in 2 (0.1%). The femoral head diameter ranged from 22 to 36 mm. Two studies reported use of acetabular autografts.40,43 Full surgical and implant details are presented in Appendix 1.

Implant survivorship, complications and reoperation

The 5- and 10-year revision-free implant survival rates were 98.7% (SD 1.5%, range 95%–100%) and 94.6% (SD 5.5%, range 78.1%–100%), respectively. In studies with mean follow-up beyond 10 years, reported revision-free survival rates were 27%–99.5% (16 studies) at 10–14 years, 59%–84% (2 studies) at 15–19 years, 70%–77% (2 studies) at 20–24 years and 60% (1 study) at 25–30 years. Rates of dislocation, deep infection and reoperation for any reason were 2.4% (SD 2.5%, range 0%–10.9%), 1.2% (SD 1.5%, range 0%–7%) and 16.3% (SD 13.6%, range 0%–63.8%), respectively. Aseptic loosening was the most common reason for reoperation. A summary of implant survivorship and complications is presented in Table 2, with full details available in Appendix 1.

Radiographic assessment and functional outcome

Nonprogressive acetabular and femoral radiolucent lines were observed in 418 (13.0%) (SD 18.4%, range 0%–85.2%) and 225 (7.0%) (SD 13.8%, range 0%–90.9%) components, respectively. Progressive radiolucency was not commonly reported. Functional outcome at final follow-up was reported with the use of the Harris Hip Score or the Merle d’Aubigné Score in all but 1 study, which used the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.34 The Harris Hip Score was reported in 26 studies, with a mean postoperative score of 91.0/100 (SD 4.8, range 81–98) and a mean improvement of 47.4 points (SD 4.6, range 32.5–53). The Merle d’Aubigné Score was reported in 7 studies, with a mean postoperative score of 16.0/18 (SD 1.6, range 10.5–17.1) and a mean improvement of 7.1 points (SD 1.5, range 5.6–8.7). Other reported outcome scores included the Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score, Oxford Hip Score and modified UCLA Activity Score.

Study quality

The level of evidence was I in 3 studies17–19 and IV in 29 studies.20–48 The risk of bias summary for each included randomized trial and the interrater agreement for each MINORS item are presented in Table 3 and Table 4, respectively. The overall risk of bias of the randomized trials was low. The majority of included case series were of low methodological quality. Agreement between the reviewers was considered satisfactory for all items. The mean MINORS global score was 11.0/16 (range 7–14).

Table 3.

Risk of bias for each included randomized trial14

| Study | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Other bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim et al.17 | + | + | ? | + | + | + | ? |

| Kim et al.18 | + | + | ? | + | + | + | ? |

| Kim et al.19 | + | + | ? | + | + | + | ? |

+ = low risk of bias; ? = unclear risk of bias.

Table 4.

Interreviewer agreement on Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies items15

| Item | κ coefficient* |

|---|---|

| 1. A clearly stated aim | 0.862 |

| 2. Inclusion of consecutive patients | 0.759 |

| 3. Prospective collection of data | 0.603 |

| 4. Endpoints appropriate to the aim of the study | 0.755 |

| 5. Unbiased assessment of the study endpoint | 0.683 |

| 6. Follow-up period appropriate to the aim of the study | 1.000 |

| 7. Loss to follow-up less than 5% | 0.861 |

| 8. Prospective calculation of the study size | 0.896 |

A value > 0.4 is considered satisfactory.

Discussion

We found that a large proportion of younger patients underwent THA for avascular necrosis and osteoarthritis secondary to congenital, developmental or traumatic anatomic abnormalities. This result is in keeping with the current literature.49 These patients often present with major structural abnormalities such as proximal femoral deformity and femoral head collapse that increase the complexity of THA. Furthermore, patients who have undergone previous surgery may have retained hardware, extensive scar tissue, heterotopic ossification or limb length discrepancy that require a greater degree of preoperative planning than routine primary THA in older patients with osteoarthritis.49 Although THA had historically been performed in younger patients for rheumatoid arthritis, only 8.3% of hips in our review had inflammatory arthritis of any kind as their preoperative diagnosis. The decreasing demand for THA in patients with inflammatory arthritis likely reflects advances in disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, leading to improved management of these conditions.50

The predominance of modular, cementless implants in our review is also consistent with current practice patterns in North America and Europe. Modular implants have gained substantial popularity as they allow surgeons to independently adjust offset, version and limb length both preoperatively and intraoperatively.51 In addition, modular head and liner exchange can be a less invasive revision option in cases of instability and eccentric polyethylene wear with well-fixed femoral and acetabular components.52 Although modularity is associated with risk of trunnion corrosion, adverse local tissue reactions and component fracture, the only modularity-related complications in our review were 4 cases of fractured ceramic liner.

The inconsistent survivorship of cemented implants in younger patients has led to a preference for cementless fixation in this population.53,54 We found that a variety of cementless femoral component designs were used, with metaphyseal-fitting stems being the most common. Metaphyseal-fitting stems are thought to not only increase proximal load transfer to reduce stress shielding and thigh pain, but also preserve diaphyseal bone for future revision,55–57 thus making them a popular choice in younger patients, who are expected to outlive their implants. Success with metaphyseal-fitting stems has furthered interest in shorter stem designs for additional bone preservation.18,58 In a within-patient randomized trial, Kim and colleagues18 reported the outcomes of 200 patients who underwent bilateral THA and were randomly allocated to receive conventional cementless stems in one hip and short cementless stems in the contralateral hip. Those authors found decreased stress shielding in the short stems but no difference in survivorship or functional outcome between the implants after a mean follow-up duration of 10.8 years.

The most commonly reported bearings in our review were metal-on-conventional-polyethylene, ceramic-on-ceramic and ceramic-on-conventional-polyethylene. This may be related to our inclusion of only studies with long-term follow-up. Although highly cross-linked polyethylene has been shown to improve wear rates compared to conventional polyethylene,59,60 long-term data showing a clear increase in clinical survivorship are not yet available. The superior wear resistance of ceramic-on-ceramic bearings offers potential reduction of wear-induced osteolysis in comparison to metal-on-conventional-polyethylene bearings, although no study to date has shown a significant difference in reoperation rates. There have also been concerns over the risk of ceramic component fracture, chipping on insertion and squeaking.61 The incidence of ceramic-related complications in our review was relatively low, with 4 cases (0.3%) of fractured ceramic liners and 5 cases (0.4%) of squeaking. Ceramic-on-conventional-polyethylene bearings have also shown excellent wear resistance in the long term,62,63 although studies comparing these bearings with metal-onconventional-polyethylene bearings have shown mixed results.64–67 We excluded metal-on-metal bearings from our review owing to widespread concerns over increased metal ion levels and adverse local tissue reactions to metallic wear debris.

The overall revision-free survival rate was 98.7% at 5 years and 94.6% at 10 years. These values are similar to those reported for THA in older patients. Mäkelä and colleagues68 reviewed the Nordic Arthroplasty Registry for all primary THA procedures performed in patients older than 55 years between 1995 and 2011. Using the outcome of revision for any reason, they reported 10-year survivorship rates of 91.8%, 90.0% and 92.2% for cementless, hybrid and cemented components, respectively, in patients aged 55–64 years. Similarly, Hailer and colleagues69 reviewed the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register from 1992 to 2007 and reported 10-year survivorship rates of 85% and 94% for cementless and cemented THA components, respectively. Survivorship beyond 10 years was inconsistently reported because the final follow-up periods varied greatly between studies. Therefore, we were able to present only the range of final survivorship rates reported in the included studies. This reflects the current paucity of studies with more than 15 years’ follow-up, which is an inherent limitation of newer technology. Only 2 studies26,46 showed implant survivorship rates less than 75% at 10–15 years. Chiu and colleagues26 reported acetabular component survivorship of 27% at 15 years in 47 Charnley low-friction arthroplasty procedures performed using early cementing techniques. They found inadequate cement mantle around 27 components (57%) that correlated strongly with subsequent aseptic loosening and emphasized the importance of good cementing technique. Wangen and colleagues46 reported acetabular component survivorship of 51% at 13 years in 47 cementless THA procedures using hydroxyapatite-coated hemispherical cups in patients younger than 30 years. They attributed the high rates of cup loosening to the tendency for dissolution and resorption of the hydroxyapatite coating on the acetabular side, which had been observed in previous studies.70,71

Rates of dislocation (2.4%) and deep infection (1.2%) in our review are comparable to values reported in large registry studies (1.9% and 1.3%, respectively).72,73 Rates of periprosthetic fracture were also relatively low in comparison to those in the literature (0.3% v. 1%), likely secondary to superior bone quality in younger patients.74 The overall reoperation rate was high, at 16.3%, although many operations were late revisions for aseptic loosening more than 10 years after THA.

Radiographic evaluation of implant stability was performed with the DeLee and Charnley75 and Gruen76 systems for acetabular and femoral components, respectively. Progressive radiolucency was rarely reported, which minimized the risk of a large number of impending aseptic failures. Substantial improvements and high postoperative Harris Hip and Merle d’Aubigné scores suggest that most patients achieved satisfactory functional outcome.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, our review was restricted to English-language studies published after 1999 that had a mean follow-up duration of 10 years or more. Although having these strict inclusion criteria allowed us to focus on contemporary, long-term outcomes that are critical to counselling patients preoperatively, they may have resulted in exclusion of studies that contribute substantially to the literature on THA in younger patients. For instance, our minimum follow-up cut-off may have led to underrepresentation of highly cross-linked polyethylene in our study owing to its relative newness. Second, most of the included studies were small, retrospective case series of low methodological quality and were heterogeneous with respect to preoperative diagnosis, surgical technique and implant selection. This limited our ability to perform a meta-analysis and reflects the current lack of prospective, standardized, multicentre data in the orthopedic literature. Third, the paucity of studies with 15 years’ follow-up limited our ability to draw conclusions about implant survivorship beyond 10 years. Finally, there was considerable variability in outcome reporting between studies. For instance, many studies did not differentiate between primary and secondary osteoarthritis. Moreover, 6 different clinical outcome scores were used among the included studies, with 11 studies reporting only postoperative scores. These inconsistencies not only limited statistical analysis but may also have led to misclassification bias.

Conclusion

Our study provides important trends and data that should help surgeons counsel younger patients undergoing THA. The most common preoperative diagnoses appear to be avascular necrosis, osteoarthritis and developmental dysplasia of the hip. Modular, cementless implants with metal-onconventional-polyethylene bearings were used in most cases, with high survivorship seen at up to 10 years. Rates of dislocation and infection were comparable to those with THA in older patients, and good functional outcomes were routinely achieved. Future studies should aim to evaluate the outcome of THA in this population at 15–20 years’ follow-up.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared by X.Y. Mei and Y.J. Gong. O. Safir declares paid consultancies with Zimmer Biomet and DePuy Synthes, speaker fees from Zimmer Biomet, and research support from DePuy Synthes in the last 2 years. A. Gross declares speaker fees from Zimmer, and paid consultancies with Zimmer and Intellijoint within the last 2 years. P. Kuzyk declares research support from DePuy Synthes.

Contributors: X.Y. Mei, O. Safir, A. Gross and P. Kuzyk designed the study. X.Y. Mei acquired and analyzed the data, which Y.J. Gong also analyzed. X.Y. Mei wrote the article, which all authors reviewed and approved for publication.

References

- 1.Callaghan JJ, Bracha P, Liu SS, et al. Survivorship of a Charnley total hip arthroplasty. A concise follow-up, at a minimum of thirty-five years, of previous reports. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2617–21. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klapach AS, Callaghan JJ, Goetz DD, et al. Charnley total hip arthroplasty with use of improved cementing techniques: a minimum twenty-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-a:1840–8. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200112000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurtz SM, Lau E, Ong K, et al. Future young patient demand for primary and revision joint replacement: national projections from 2010 to 2030. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:2606–12. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0834-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maradit Kremers H, Larson DR, Crowson CS, et al. Prevalence of total hip and knee replacement in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:1386–97. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.01141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hip and knee replacements in Canada, 2014–2015: Canadian Joint Replacement Registry annual report. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.11th annual report 2014: National Joint Registry for England, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man. Hemel Hempstead (UK): National Joint Registry; 2015. [accessed 2019 Apr 24]. Age and gender of primary hip replacement patients (graph) Available: www.njrreports.org.uk/hips-primary-procedures-patient-characteristics/H06v4NJR?reportid=24DFC886-2530-4EEE-9327-999776161705&defaults=DC__Reporting_Period__Date_Range=%222015%7CNJR2014%22,J__Filter__Calendar_Year=%22MAX%22,R__Filter__Gender=%22All%22,H__Filter__Joint=%22Hip%22. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hip, knee and shoulder arthroplasty: annual report 2014. Adelaide (Australia): Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorr LD, Kane TJ, 3rd, Conaty JP. Long-term results of cemented total hip arthroplasty in patients 45 years old or younger. A 16-year follow-up study. J Arthroplasty. 1994;9:453–6. doi: 10.1016/0883-5403(94)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandler HP, Reineck ET, Wixson RL, et al. Total hip replacement in patients younger than thirty years old. A five-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63:1426–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharp DJ, Porter KM. The Charnley total hip arthroplasty in patients under age 40. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;201:51–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Homesley HD, Minnich JM, Parvizi J, et al. Total hip arthroplasty revision: a decade of change. Am J Orthop. 2004;33:389–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurtz S, Mowat F, Ong K, et al. Prevalence of primary and revision total hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 1990 through 2002. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1487–97. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schreurs BW, Hannink G. Total joint arthroplasty in younger patients: Heading for trouble? Lancet. 2017;389:1374–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. Cochrane Bias Methods Group; Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, et al. Methodological index for nonrandomized studies (MINORS): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:712–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med. 2012;22:276–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim YH, Kim JS, Park JW, et al. Comparison of total hip replacement with and without cement in patients younger than 50 years of age: the results at 18 years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93:449–55. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B4.26149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim YH, Park JW, Kim JS. Ultrashort versus conventional anatomic cementless femoral stems in the same patients younger than 55 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:2008–17. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-4902-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim YH, Park JW, Kim JS, et al. Twenty-five- to twenty-seven-year results of a cemented vs a cementless stem in the same patients younger than 50 years of age. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:662–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akbar M, Aldinger G, Krahmer K, et al. Custom stems for femoral deformity in patients less than 40 years of age: 70 hips followed for an average of 14 years. Acta Orthop. 2009;80:420–5. doi: 10.3109/17453670903062470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Babovic N, Trousdale RT. Total hip arthroplasty using highly cross-linked polyethylene in patients younger than 50 years with minimum 10-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:815–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biemond JE, Pakvis DF, Van Hellemondt GG, et al. Long-term survivorship analysis of the cementless Spotorno femoral component in patients less than 50 years of age. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26:386–90. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boyer P, Huten D, Loriaut P, et al. Is alumina-on-alumina ceramic bearings total hip replacement the right choice in patients younger than 50 years of age? A 7- to 15-year follow-up study. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2010;96:616–22. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burston BJ, Yates PJ, Hook S, et al. Cemented polished tapered stems in patients less than 50 years of age: a minimum 10-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:639–99. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chana R, Facek M, Tilley S, et al. Ceramic-on-ceramic bearings in young patients: outcomes and activity levels at minimum ten-year follow-up. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-b:1603–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B12.30917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiu KY, Ng TP, Tang WM, et al. Charnley total hip arthroplasty in Chinese patients less than 40 years old. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:92–101. doi: 10.1054/arth.2001.19156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi WK, Kim JJ, Cho MR. Results of total hip arthroplasty with 36-mm metallic femoral heads on 1st generation highly cross linked polyethylene as a bearing surface in less than forty-year-old patients: minimum ten-year results. Hip Pelvis. 2017;29:223–7. doi: 10.5371/hp.2017.29.4.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crowther JD, Lachiewicz PF. Survival and polyethylene wear of porous-coated acetabular components in patients less than fifty years old: results at nine to fourteen years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:729–35. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duffy GP, Berry DJ, Rowland C, et al. Primary uncemented total hip arthroplasty in patients < 40 years old: 10- to 14-year results using first-generation proximally porous-coated implants. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16(Suppl 1):140–4. doi: 10.1054/arth.2001.28716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faldini C, Miscione MT, Chehrassan M, et al. Congenital hip dysplasia treated by total hip arthroplasty using cementless tapered stem in patients younger than 50 years old: results after 12-years follow-up. J Orthop Traumatol. 2011;12:213–8. doi: 10.1007/s10195-011-0170-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flecher X, Pearce O, Parratte S, et al. Custom cementless stem improves hip function in young patients at 15-year followup. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:747–55. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1045-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia-Cimbrelo E, Cruz-Pardos A, Cordero J, et al. Low-friction arthroplasty in patients younger than 40 years old: 20- to 25-year results. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:825–32. doi: 10.1054/arth.2000.8097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsu JE, Kinsella SD, Garino JP, et al. Ten-year follow-up of patients younger than 50 years with modern ceramic-on-ceramic total hip arthroplasty. Semin Arthroplasty. 2011;22:229–33. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keener JD, Callaghan JJ, Goetz DD, et al. Twenty-five-year results after Charnley total hip arthroplasty in patients less than fifty years old: a concise follow-up of a previous report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1066–72. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200306000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim YH, Park JW, Park JS. The 27 to 29-year outcomes of the PCA total hip arthroplasty in patients younger than 50 years old. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:2256–61. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewthwaite SC, Squires B, Gie GA, et al. The Exeter™ universal hip in patients 50 years or younger at 10–17 years’ followup. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:324–31. doi: 10.1007/s11999-007-0049-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McLaughlin JR, Lee KR. Total hip arthroplasty with an uncemented tapered femoral component in patients younger than 50 years of age: a minimum 20-year follow-up study. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:1275–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pakvis D, Biemond L, Van Hellemondt, et al. A cementless elastic monoblock socket in young patients: a ten to 18-year clinical and radiological follow-up. Int Orthop. 2011;35:1445–51. doi: 10.1007/s00264-010-1120-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Philippot R, Neri T, Boyer B, et al. Bousquet dual mobility socket for patient under fifty years old. More than twenty year follow-up of one hundred and thirty one hips. Int Orthop. 2017;41:589–94. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3385-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmitz MW, Busch VJ, Gardeniers JW, et al. Long-term results of cemented total hip arthroplasty in patients younger than 30 years and the outcome of subsequent revisions. BMC Musculoskel Disord. 2013;14:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmolders J, Amvrazis G, Pennekamp PH, et al. Thirteen year follow-up of a cementless femoral stem and a threaded acetabular cup in patients younger than fifty years of age. Int Orthop. 2017;41:39–45. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3226-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singh S, Trikha SP, Edge AJ. Hydroxyapatite ceramic-coated femoral stems in young patients. A prospective ten-year study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:1118–23. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.86b8.14928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith SE, Estok DM, 2nd, Harris WH. 20-year experience with cemented primary and conversion total hip arthroplasty using so-called second-generation cementing techniques in patients aged 50 years or younger. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:263–73. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(00)90463-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stambough JB, Pashos G, Bohnenkamp FC, et al. Long-term results of total hip arthroplasty with 28-millimeter cobalt–chromium femoral heads on highly cross-linked polyethylene in patients 50 years and less. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:162–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Utting MR, Raghuvanshi M, Amirfeyz R, et al. The Harris–Galante porous-coated, hemispherical, polyethylene-lined acetabular component in patients under 50 years of age: a 12- to 16-year review. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:1422–7. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B11.20892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wangen H, Lereim P, Holm I, et al. Hip arthroplasty in patients younger than 30 years: excellent ten to 16-year follow-up results with a HA-coated stem. Int Orthop. 2008;32:203–8. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0309-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wroblewski BM, Purbach B, Siney PD, et al. Charnley low-friction arthroplasty in teenage patients: the ultimate challenge. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:486–8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B4.23477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoon HJ, Jeong JY, Kang SY, et al. Alumina-on-alumina THA performed in patients younger than 30 years: a 10-year minimum followup study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:3530–6. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2493-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Polkowski GG, Callaghan J, Mont M, et al. Total hip arthroplasty in the very young patient. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20:487–97. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-20-08-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hekmat K, Jacobsson L, Nilsson JA, et al. Decrease in the incidence of total hip arthroplasties in patients with rheumatoid arthritis — results from a well defined population in south Sweden. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R67. doi: 10.1186/ar3328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duwelius PJ, Burkhart B, Carnahan C, et al. Modular versus non-modular neck femoral implants in primary total hip arthroplasty: Which is better? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:1240–5. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3361-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walmsley DW, Waddell JP, Schemitsch EH. Isolated head and liner exchange in revision hip arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25:288–96. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dorr LD, Kane ITJ, Pierce Conaty J. Long-term results of cemented total hip arthroplasty in patients 45 years old or younger: a 16-year follow-up study. J Arthroplasty. 1994;9:453–6. doi: 10.1016/0883-5403(94)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dorr LD, Luckett M, Conaty JP. Total hip arthroplasties in patients younger than 45 years. A nine- to ten-year follow-up study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;260:215–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mallory TH, Head WC, Lombardi AV., Jr Tapered design for the cementless total hip arthroplasty femoral component. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;344:172–8. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199711000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Renkawitz T, Francesco SS, Grifka J, et al. A new short uncemented, proximally fixed anatomic femoral implant with a prominent lateral flare: design rationals and study design of an international clinical trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:147. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saito J, Aslam N, Tokunaga K, et al. Bone remodeling is different in metaphyseal and diaphyseal-fit uncemented hip stems. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;451:128–33. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000224045.63754.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim YH, Park JW, Kim JS. Is diaphyseal stem fixation necessary for primary total hip arthroplasty in patients with osteoporotic bone (Class C bone)? J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:139–46.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Glyn-Jones S, Thomas GE, Garfjeld-Roberts P, et al. The John Charnley Award: highly crosslinked polyethylene in total hip arthroplasty decreases long-term wear: a double-blind randomized trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:432–8. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3735-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kuzyk PR, Saccone M, Sprague S, et al. Cross-linked versus conventional polyethylene for total hip replacement: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93:593–600. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B5.25908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kamath AF, Prieto H, Lewallen DG. Alternative bearings in total hip arthroplasty in the young patient. Orthop Clin North Am. 2013;44:451–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Urban JA, Garvin KL, Boese CK, et al. Ceramic-on-polyethylene bearing surfaces in total hip arthroplasty. Seventeen to twenty-one-year results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-a:1688–94. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200111000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wroblewski BM, Siney PD, Fleming PA. Low-friction arthroplasty of the hip using alumina ceramic and cross-linked polyethylene. A ten-year follow-up report. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81:54–5. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.81b1.8822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nakahara I, Nakamura N, Nishii T, et al. Minimum five-year followup wear measurement of longevity highly cross-linked polyethylene cup against cobalt–chromium or zirconia heads. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:1182–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stilling M, Nielsen KA, Soballe K, et al. Clinical comparison of polyethylene wear with zirconia or cobalt–chromium femoral heads. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:2644–50. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0799-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hernigou P, Bahrami T. Zirconia and alumina ceramics in comparison with stainless-steel heads. Polyethylene wear after a minimum ten-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:504–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.85b4.13397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Epinette JA, Manley MT. No differences found in bearing related hip survivorship at 10–12 years follow-up between patients with ceramic on highly cross-linked polyethylene bearings compared to patients with ceramic on ceramic bearings. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:1369–72. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mäkelä KT, Matilainen M, Pulkkinen P, et al. Failure rate of cemented and uncemented total hip replacements: register study of combined Nordic database of four nations. BMJ. 2014;348:f7592. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f7592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hailer NP, Garellick G, Kärrholm J. Uncemented and cemented primary total hip arthroplasty in the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register: evaluation of 170,413 operations. Acta Orthop. 2010;81:34–41. doi: 10.3109/17453671003685400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lazarinis S, Kärrholm J, Hailer NP. Increased risk of revision of acetabular cups coated with hydroxyapatite: a Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register study involving 8,043 total hip replacements. Acta Orthop. 2010;81:53–9. doi: 10.3109/17453670903413178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reikeras O, Gunderson RB. Failure of HA coating on a gritblasted acetabular cup: 155 patients followed for 7–10 years. Acta Orthop Scand. 2002;73:104–8. doi: 10.1080/000164702317281503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Meek RM, Allan DB, McPhillips G, et al. Epidemiology of dislocation after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;447:9–18. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000218754.12311.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dale H, Skråmm I, Løwer HL, et al. Infection after primary hip arthroplasty: a comparison of 3 Norwegian health registers. Acta Orthop. 2011;82:646–54. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.636671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Della Rocca GJ, Leung KS, Pape HC. Periprosthetic fractures: epidemiology and future projections. J Orthop Trauma. 2011;25(Suppl 2):S66–70. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31821b8c28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.DeLee JG, Charnley J. Radiological demarcation of cemented sockets in total hip replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;121:20–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gruen TA, McNeice GM, Amstutz HC. “Modes of failure” of cemented stem-type femoral components: a radiographic analysis of loosening. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;141:17–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]