Abstract

Variants in the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) have been associated with increased risk for sporadic, late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Here we show that germline knockout of Trem2 or the TREM2R47H variant reduce microgliosis around amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and facilitate the seeding and spreading of neuritic plaque (NP) tau aggregates. These findings demonstrate a key role for TREM2 and microglia in limiting development of peri-plaque tau pathologies.

Rare variants conferring a partial loss of function in TREM2, a cell surface receptor specifically found on microglia in the brain, increase AD-risk 2–4-fold.1 In addition, TREM2 variant carriers have a faster rate of cognitive decline, suggesting TREM2 also influences disease progression.2 Previous studies by our group and others have characterized the effects of TREM2 deficiency on Aβ plaques, hypothesized to be an initiator of AD,3 and found that the loss or reduction of TREM2 function decreased microgliosis surrounding plaques in multiple mouse models and in humans expressing the AD-risk allele, TREM2R47H.4-12 This corresponded with increased neuritic dystrophy around plaques.7,8,10-12 Together, TREM2 genetic and functional data insinuate that microglia are critical to mitigating damage inflicted by nearby Aβ plaques; yet, how these protective microglial actions and the TREM2 variants that interrupt them contribute to AD risk and progression remains ambiguous.

Swollen, dystrophic neural processes containing aggregated, phosphorylated tau (p-tau) surrounding Aβ deposits are a key feature of NPs, a hallmark pathology of AD. P-tau also composes the second pathological protein aggregate that defines AD, neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). NFTs are largely found in the medial temporal lobe of cognitively normal individuals with and without preclinical AD. Progression of tau pathology into the limbic and neocortex with antecedent Aβ pathology coincides with cognitive impairment.13 A recent study demonstrated that the presence of amyloid plaques facilitated local tau seeding in dystrophic neurites that later spurred the spreading and formation of p-tau in NPs and NFTs in mice.14 This strengthens the hypothesis that Aβ plaque accumulation damages adjacent neural processes, creating a favorable environment for early NP tau aggregation that can facilitate greater p-tau expansion in NPs and NFTs and AD progression. Previous studies support that microglia limit peri-plaque neuritic dystrophy;7,8,10-12,15 therefore, we hypothesized that loss of plaque-associated microglia in mice with reduced or null TREM2 function would further exacerbate seeded NP tau formation, aggregation, and spreading.

To investigate the effects of TREM2 deficiency and the TREM2R47H AD-risk variant on NP tau pathology, we employed a newly developed model of inducing endogenous mouse tau to have AD-like tau features by seeding the brain with sarkosyl-insoluble tau aggregates isolated from the frontal cortex of human AD brain tissue (AD-tau), prepared as previously described.14,16 APPPS1–21 Trem2+/+ (T2WT) or Trem2−/− (T2KO) mice4 and APPPS1–21 mice expressing the human TREM2 common variant (T2CV) or R47H AD-risk variant (T2R47H) on a mouse T2KO background8 were unilaterally injected at 5.5 months-of-age in the dentate gyrus and overlying cortex (1µg/site) and analyzed 3-months post-injection (3 mo p.i.). APPPS1–21 mice have substantial cortical and early hippocampal Aβ pathology by 5.5 mo, even in the absence of TREM2,4 yet negligible NP tau aggregation that can be identified by immunostaining. However, injection of AD-tau in mice with Aβ plaques was reported to preferentially induce NP tau aggregates as opposed to NFTs by 3mo p.i.14

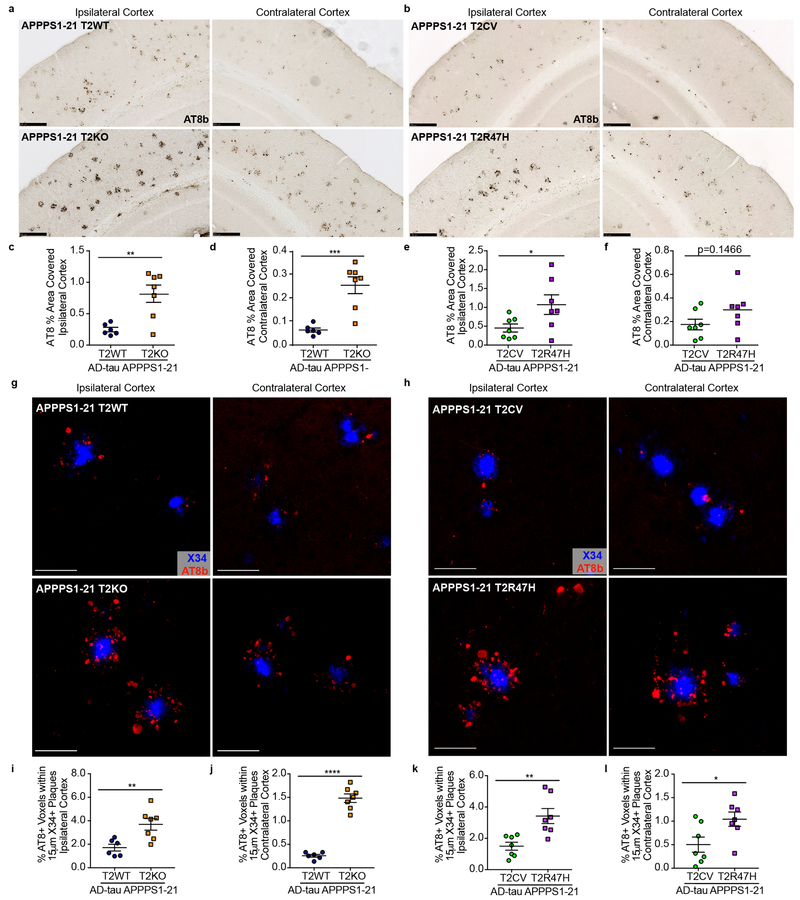

We observed widespread seeded NP tau aggregation throughout the ipsilateral (ipsi) cortex of APPPS1–21 mice as well as spread to the contralateral (contra) cortex using this experimental paradigm (characterization of unseeded and seeded APPPS1–21 mice in Supplementary Fig.1) that was remarkably elevated in T2KO and T2R47H mice compared to T2WT and T2CV mice, respectively (Fig. 1a-f). Notably, human tau was not detected in AD-tau treated mice (Supplementary Fig. 2) indicating aggregates were composed of seeded mouse tau, as previously described.16 NP tau aggregates were not observed in the absence of Aβ plaques (Supplementary Fig. 3), also consistent with previous findings.14 We did not detect a difference in cortical, fibrillar Aβ plaque burden in T2WT vs. T2KO or in T2CV vs. T2R47H mice (Supplementary Fig. 4). Minimal NFTs distant from plaques were observed using this experimental strategy (Supplementary Fig. 5) and model. Nominal hippocampal NP tau seeding was detected (Supplementary Fig. 1), likely due to the comparatively lower hippocampal vs. cortical Aβ plaque burden in this model (Supplementary Fig. 4), and therefore not assessed. To confirm that cortical NP tau aggregation was increased independent of the number of Aβ plaques, we performed confocal analysis and quantified the amount of NP tau surrounding individual X34 positive (X34+) Aβ plaques (Fig. 1g-l). This corroborated that seeded NP tau pathology was significantly increased with loss of TREM2 function and in the setting of the TREMR47H variant, regardless of plaque size (Supplementary Fig. 6a-b). Notably, a portion of the NP tau surrounding plaques also co-localized with X34, indicative of a more advanced, fibrillar p-tau aggregate (Supplementary Fig. 7a-b). All seeded mice contained some fibrillar NP tau, but these aggregates were significantly pronounced in T2KO and R47H mice (Supplementary Fig. 7c-d). Altogether, these data support that loss of TREM2 function increases the burden of seeded peri-plaque p-tau deposits.

Fig. 1. NP tau pathology is significantly increased with loss of TREM2 function.

a, b, Representative images of AT8-labeled NP tau burden in AD-tau seeded APPPS1-21 T2WT and T2KO (a) or T2CV and T2R47H mice (b). Scale bars 250µm. c, d, e, f, Quantification of AT8 staining in the ipsi and contra cortices of T2WT and T2KO mice (t(11), ipsi **P=0.0039, contra ***P=0.0005) (c,d) or T2CV and T2R47H mice (t(12), ipsi *P=0.0484, contra P=0.1466) (e,f). g,h, Confocal images of cortical AT8+ NP tau (red) around X34+ plaques (blue). Scale bars 50µm. i,j,k,l Quantification of the percent of AT8+ voxels within 15µm of plaques in T2WT and T2KO mice (t(11), ipsi **P=0.0066, contra ***P<0.0001) (i,j) or T2CV and T2R47H mice (t(12), ipsi **P=0.0064, contra *P=0.0311) (k.l). Significance determined by unpaired, two-sided student’s t-test for T2WT (n = 6) and T2KO (n = 7) or T2CV (n = 7) and T2R47H (n = 7). Individual data points are plotted for each group ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

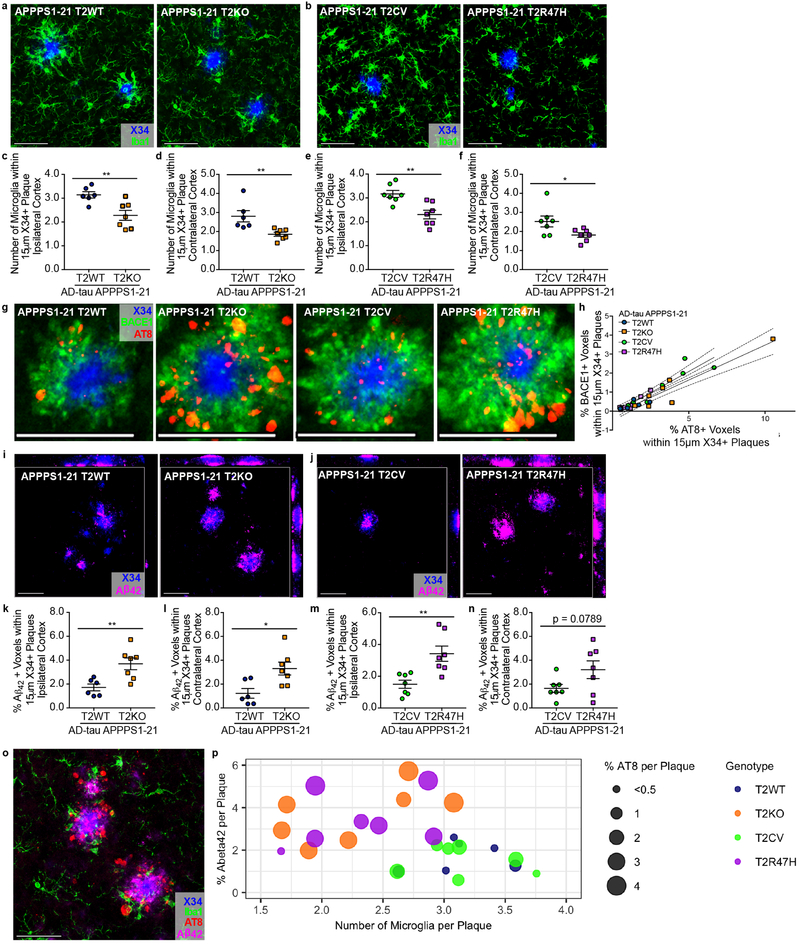

We next investigated how reduced TREM2 function could facilitate NP tau seeding. As expected,4-8,10,11 we observed reduced plaque-associated microgliosis in T2KO and T2R47H mice compared to T2WT and T2CV mice, respectively (Fig. 2a-f). Several previous publications have reported increased neuritic dystrophy around plaques in TREM2 deficient models or in the presence of the R47H variant.7,8,11,12 We labeled dystrophic neurites by immunostaining for BACE1, which accumulates in dystrophic neuronal processes,17 and observed a strong correlation between the amount of BACE1-labeled processes and AT8 staining (Fig. 2g-h). Although some co-localization was detected, we unexpectedly found that many AT8+ neurites did not co-localize with BACE1, suggesting that dystrophic neurites are a heterogenous population of structures, perhaps with different proclivity for seeding of aggregated p-tau.15,17 Despite their poor overall co-localization, the strong positive correlation between BACE1 and AT8 suggests that overall Aβ plaque-induced neuronal toxicity contributes to a favorable environment for the induction of pathological tau seeding. While plaques are composed of different Aβ species, Aβ42 in particular is neurotoxic and can affect microtubule stability and tau phosphorylation.3 One recent study described an inverse relationship between encapsulation of plaques by microglial processes and Aβ42 ‘hot-spots’ on plaques, which further corresponded with increased dystrophic neurites.15 Therefore, we tested whether TREM2-deficiency affected Aβ42 immunoreactivity within amyloid plaques. Confocal analysis of plaques co-stained with X34 and a C-terminal, Aβ42-specific antibody revealed significant increases of Aβ42 in and around X34+ plaques in the ipsilateral cortex of T2KO and R47H mice (Figure 2i-n), regardless of plaque size (Supplementary Fig. 6c-d). Fig. 2o-p illustrates that NP tau seeding is preferentially increased in T2KO and T2R47H mice as a function of the number of plaque-associated microglia and the percent of Aβ42 comprising plaques.

Fig. 2. Seeded NP-tau corresponds with loss of TREM2-dependent plaque-associated microglia, neuritic dystrophy and increased Aβ42 around plaques.

a, b, Confocal analysis of Iba1-labeled microglia (green) surrounding X34+ plaques (blue). c, d, e, f, Quantification of the number of microglial cells surrounding plaques in T2WT and T2KO (t(11), ipsi **P=0.0066, contra **P=0.0088) (c, d) or T2CV and T2R47H mice (t(12), ipsi **P=0.0033, contra *P=0.0409) (e, f). g, Confocal image of BACE1 (green) and AT8 (red) co-stained around X34+ plaques (blue). h, Pearson’s correlation of BACE1 and AT8 staining in AD-tau seeded APPPS1-21 T2WT and T2KO mice (r=0.9465, R2=0.8959, p<0.0001) and T2CV and T2R47H mice (r=0.9393, R2=0.8822, p<0.0001). i, j, Confocal images of Aβ42 (magenta) in and around X34+ plaques (blue). k, l, m, n, Quantification of the percent of Aβ42+ voxels within 15µm of plaques in T2WT and T2KO (t(11), ipsi **P=0.0066, contra *P=0.0121) (k, l) or T2CV and T2R47H mice (t(12), ipsi **P=0.0041, contra P=0.0789) (m, n). All representative images from ipsi cortex, scale bars 50µm. Significance determined by unpaired, two-sided student’s t-test for T2WT (n = 6) and T2KO (n = 7) or T2CV (n = 7) and T2R47H (n = 7). Individual data points are plotted for each group ± SEM. o, Representative image of co-stain for X34 (blue), AT8 (red), Aβ42 (magenta), and Iba1 (green) from a seeded APPPS1–21 T2KO mouse. Scale bar 50µm. p, Relationship between co-stained Iba1+ microglial cells (x-axis), Aβ42 (y-axis), and seeded AT8 NP tau surrounding X34+ plaques in the ipsi cortex. Each dot represents an individual mouse, dot color indicates TREM2 genotype, and dot size corresponds to percent of AT8+ staining around plaques (reported in Fig. 1). Significant Pearson’s correlations were observed between the number of microglia to % AT8 per plaque (r= −0.4531, R2=0.2053, *P<0.0176) and between % Aβ42 and AT8 (r= 0.8031, R22=0.6405, ***P<0.0001) surrounding plaques. A trend for a correlation was observed when comparing all groups for the number of microglia to % Aβ42 (r= −0.3463, R2=0.1199, P=0.0771). Significant comparisons and correlations between groups were initially observed in two separate experiments (co-staining for X34, AT8 and Aβ42 or co-staining for X34 and Iba1). Subsequently, a quadruple stain was performed for all antigens (X34, AT8, Aβ42 and Iba1) within the same tissue sections; these data confirmed previous significant observations and are reported in Figs. 1 and 2.

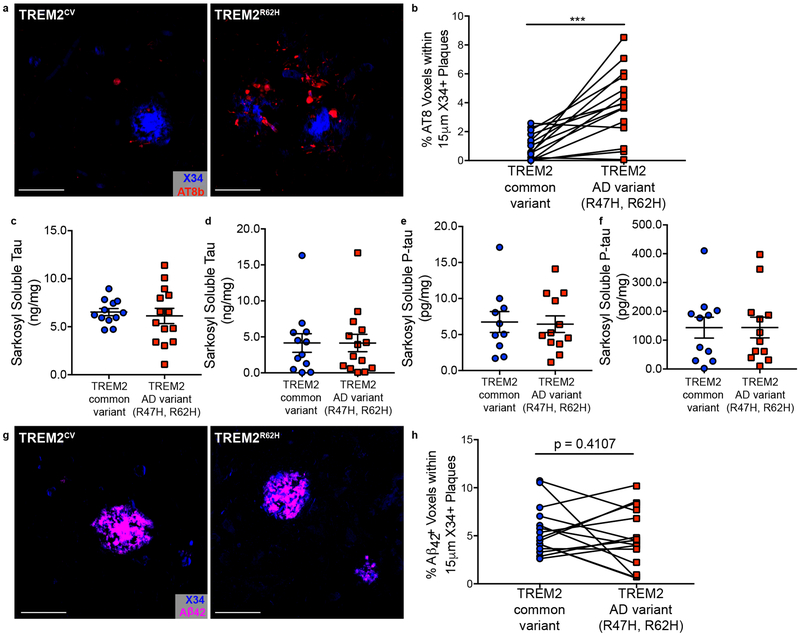

Finally, we assessed whether human AD cases from AD-associated TREM2 variant carriers exhibited similar elevations in NP tau. We examined prefrontal cortex tissue from late-onset AD TREM2R47H and TREM2R62H variant carriers and their case-matched controls. Consistent with our mouse data and a previous study,7 we detected significantly more p-tau around plaques in TREM2 AD-risk variant carriers (Fig. 3a-b). The increase in NP tau staining in AD-associated TREM2 variant carriers was independent of APOEε4 genotype, consistent with a recent report finding that reduced microgliosis in TREM2 variant carriers was independent of APOEε4 genotype (Supplementary Fig. 8).12 The increase in NP tau staining was also not attributable to overall changes in total insoluble tau or p-tau (Fig. 3c-f). Analysis of Aβ42 staining around plaques did not reveal significant increases in TREM2 variant carriers (Figure 3g-h). Given that we assessed end-stage AD cases (Supplementary Table 1), it is possible that the plaques have matured differently than in our mouse model, which recapitulates the preclinical phase of the disease. There may also be additional factors contributing to Aβ42 plaque composition and morphology in humans which are not fully recapitulated in APPPS1–21 mice. Future studies are needed to better delineate if there is a relationship between Aβ42 around plaques and NP tau deposition or loss of plaque-associated microglia in human TREM2 variant carriers.

Fig. 3. TREM2 variant carriers have significantly more NP tau aggregation and Aβ42 around plaques.

a, Representative image from confocal analysis of AT8 staining (red) surrounding X34+ plaques (blue) in TREM2R47H/R62H AD patients and case-matched TREM2CV AD-controls. Scale bars 50µm. b, Quantification AT8+ NP tau within 15µm of X34+ plaques (t(15) *P=0.0002). Significance determined by paired, two-sided t-test. c, d, e, f, Levels of soluble (t(24) P=0.6686) and insoluble total tau (t(24) P=0. 9994) (c, d) and soluble (t(24) P=0. 9594) and insoluble (t(24) P=0.8673) p-tau (e, f) in human AD cases (Supplementary Table 2). Significance determined by unpaired, two-sided student’s t-test. Individual data points are plotted for each group ± SEM. g, Representative image from confocal analysis of Aβ42 staining (magenta) surrounding X34+ plaques (blue) from human AD cases. h, Quantification of Aβ42 within 15µm of X34+ plaques (t(15) P=0.4107). Significance determined by paired, two-sided t-test. For immunostaining analysis, case-matched controls included TREM2R47H n = 8, TREM2R62H n = 7, TREM2CV n = 14; one TREM2CV was shared for two TREM2 variant cases. For biochemical analyses, TREM2R47H n = 7, TREM2R62H n = 7, TREM2CV n = 11.

Previous studies have only considered the effects of TREM2 function in the context of either Aβ4-12 or tau pathologies.18-20 Here, we employed a newly developed mouse model of both and Aβ and tau aggregation14 and found that TREM2 deficiency and the TREM2R47H variant increased susceptibility of tau seeding and spreading in dystrophic neurons surrounding Aβ plaques, which also corresponded with more Aβ42 accumulation and less microgliosis. A key question that remains unanswered in AD pathogenesis is how the accumulation of Aβ is linked to the progression of tau pathology in AD. Our data suggest that microglia and TREM2 lay at a critical intersection of Aβ and tau pathologies. TREM2-facilitated microglial association with plaques appears to limit damage to surrounding neuronal processes, possibly by containing toxic Aβ42 species, and prevents early tau seeding events. Previous work showed that these NP tau aggregates can lead to NFT formation.14 Thus, our findings offer novel evidence of how TREM2 function in microglia limits Aβ plaque-mediated tau pathogenesis in AD. They also suggest that loss of plaque-associated microglia in TREM2 variant carriers increases AD-risk and disease progression via increasing susceptibility to tau-seeding and spreading.

Methods.

Animals.

APPPS1–21 mice (gift from Mathias Jucker) that co-express human amyloid precursor protein (APP) with a Swedish mutation (KM670/671NL) and human mutant presenilin 1 (PS1, L1669) under control of the Thy1 promoter21 were crossed to either TREM2+/+ (T2WT) or TREM2−/− (T2KO)22 mice to generate APPPS1–21/T2WT (n = 6; 4 female, 2 male) or APPPS1–21/T2KO (n = 7; 4 female, 3 male) mice.4 APPPS1–21 mice that were mouse T2KO were also crossed to mice that had been engineered using bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) technology to express human TREM2 with either the common variant (T2CV) or R47H AD-risk variant (T2R47H) on a mouse TREM2 KO background8 to generate APPPS1–21/T2CV (n= 7; 1 female, 6 male) and APPPS1–21/T2R47H (n = 7; 6 female, 1 male) mice. No statistical methods were used to pre-determine sample sizes but our sample sizes are similar to those reported in He et al.14 the only other manuscript to date that has used this experimental strategy. One mouse was excluded from the T2WT group due to a failed injection, which was apparent upon IHC analysis and the subject also tested as an outlier by Grubb’s test. All mice were bred on a C57BL6 background and housed in pathogen-free conditions under a normal 12-hour light/dark cycle. All animal protocols were approved by the Animals Studies Committee at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Preparation of tau aggregates from human Alzheimer’s brain tissue for injection into mice and biochemical analysis.

AD-tau was isolated from a human AD brain, Braak stage V-VI, as previously described.16 Total protein concentration of the final supernatant was 6.7µg/µL as determined by BCA assay (Thermo Fisher). Protein-specific sandwich enzyme linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were used to determine the amount of tau, Aβ40, Aβ42, and alpha-synuclein in the AD-tau preparation, the concentrations of which were found to be 1.2µg/µL, not detectable, 12.4µg/µL, and 0.42µg/µL respectively. AD-tau was diluted to a final concentration of 0.4µg/µL and stored at −800C. Sample underwent one freeze-thaw to be aliquoted for injections. Prior to injection, each aliquot of AD-tau was thawed on ice and sonicated in a water bath sonicator (QSonica, Q700) for 30 seconds at 65% amplitude at 40C.

Stereotactic intracerebral injections.

Mice were anesthetized with isofluorane, immobilized in a stereotactic frame (David Kopf Instruments), and ascetically injected with 2.5µL of AD-tau in the dentate gyrus (Bregma: −2.5mm; lateral: −2.0mm; depth: −2.2mm) and overlying cortex (Bregma: −2.5mm; lateral: −2.0mm; depth: −1.0mm) using a Hamilton syringe (Hamilton, syringe: 80265–1702RNR; needle: 7803–07). To examine both seeding and spread of tau pathology, mice were unilaterally injected with a total of 2 µg AD-tau (1µg at each injection site). Mice were allowed to recover on a 370C heating pad and monitored for the first 48-hours post-surgery. All animals underwent the same procedures, therefore no randomization was necessary.

Brain extraction and preparation.

Mice were anesthetized with intraperitoneal pentobarbital (200mg/kg), perfused with 3U/mL heparin in cold Dulbecco’s PBS and the brains were carefully extracted. Whole brains were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 days before being transferred to 30% sucrose and stored at 4°C until they were sectioned. Brains were cut coronally into 30μm sections on a freezing sliding microtome (Leica SM1020R) and stored in cryoprotectant solution (0.2M phosphate buffered saline, 15% sucrose, 33% ethylene glycol) at −20°C until use. A small nick was placed with a razor blade on the left hemisphere at the piriform cortex to ensure proper identification of the ipsilateral injected side in subsequent immunostaining experiments.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for NP tau was performed with biotinylated AT8 (AT8b) (Thermo Fisher, MN1020B) at a 1:500 dilution. A biotinylated in-house human tau25–30 specific antibody23 was used to detect injected human AD-tau at a 1:500 dilution. For IHC, sections were washed 3 times for 5 minutes in tris-buffered saline (TBS), then placed in 0.3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes. After washing, sections were blocked in 3% milk 0.25% TBS-triton-X-100 (TBS-X) for 30 minutes and then placed in primary antibody overnight at 40C. The next day, sections were washed and placed in ABC Elite (Vector Laboratories, PK-4000) for 1 hour, washed again, and developed in DAB (Sigma Aldrich, D4293) supplemented with 0.225% hydrogen peroxide and 0.1% nickel chloride. Sections were mounted, allowed to dry overnight, dehydrated in sequential alcohol dilutions followed by xylene and then sealed with Cytoseal (Thermo Fisher, 8310). Immunofluorescence (IF) co-stains were performed for 1) X34, Aβ42 AT8, and Iba1 or 2) X34, AT8 and BACE1. Fibrillar Aβ was stained by X34 dye (Sigma, SML-1954) and antibodies to AT8, Aβ42 (Thermo Fisher, 700254, 1:500), Iba1 (Abcam, ab5076, 1:2000), and BACE1 (Abcam, ab108394, 1:500) were used to interrogate peri-plaque pathologies. All stains were performed with free-floating sections on a shaker at room temperature unless otherwise indicated. For IF, sections were washed and then permeabilized in 0.25% triton-X-100 phosphate-buffered saline (PBS-X) for 30 minutes. Lipofuscin was quenched with 0.1% Sudan black, washed once in 0.02% PBS-tween-20 and again in PBS. Tissue was then incubated in X34 for 20 minutes, washed 3 times in X34 buffer (40% EtOH in PBS), and washed in PBS 2 times. Sections were then blocked for 30 minutes in 3% bovine serum albumin, 3% normal goat serum, 0.1% PBS-X for 30 minutes, before being placed in primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 40C. The next day, sections were washed, placed in secondary antibodies for 2 hours (Thermo Fisher, 1:500), and then washed again 3 times for 20 minutes. Section were mounted, sealed in ProLong Gold anti-fade (Thermo Fisher, P36930), and stored in the dark at 40C until imaging. Additional details on antibodies and reagents can be found in the Life Sciences Reporting Summary accompanying this manuscript.

IF of human tissue.

Slides with 8μm thick sections of prefrontal cortex from TREM2 CV and R47H or R62H AD cases were co-stained for X34, Aβ42 and AT8 using the previously described IF protocol, with the addition of a 10-minute antigen retrieval step in boiling citrate buffer prior to permeabilization in PBS-X. Cases were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Washington University-St. Louis. All TREM2R47H and TREM2R62H cases were paired with a TREM2CV case control that was matched by age, gender, and apolipoprotein E status (Supplemental Table 1).

Image acquisition and analysis.

Stains were quantified from 3–4 sections per a subject for IHC and 2–3 sections for IF. In IF images, on average there were 1–4 plaques for mouse stains and 3–6 plaques for human stains within a given image. Notably, the number of plaques and plaque size was not significantly different between compared groups for all confocal analyses. For IHC stains, slides were scanned using a NanoZoomer digital pathology system (Hamamatsu Photonics, Middlesex, NJ) and images were processed using NDP viewing software (Hamamatsu) and ImageJ software version 2.0.0 (National Institutes of Health). For IF, 2–3 z-stacks per section were acquired on an LSM 880 II Airyscan FAST confocal microscope (Zeiss) with a 20x objective. Quantification of confocal images for p-tau and Aβ42 around X34+ plaques was performed on a semi-automated platform using MATLAB and Imaris 9.2 software (Bitplane) to create surfaces of each stain based on a threshold applied to all images, dilate X34 surfaces 15µm, and co-localize various immuno-stained surfaces and dilated X34 surfaces. For quantification of the number of plaque-associated microglia, a threshold was applied across all images to assign spots to each microglial cell body. X34 surfaces were dilated 15µm, and spots were manually counted within the X34+ extended surface. Any spots fully within or partially touching the extended surface were included in the analysis. AT8 stained NFTs were manually counted in the ipsilateral cortex and hippocampus of seeded mice. All staining experiments were imaged and quantified by a blinded observer. Representative images were further processed using ImageJ, Illustrator and Photoshop CC 2017 (Adobe Systems). R studio was used to generate plots comparing different AT8, Aβ42, and microglia cells surrounding X34+ plaques.

Tau ELISAs.

The concentration of total soluble and insoluble tau from human AD cases (Supplementary Table 2) was quantified in a tau sandwich ELISA as previously described19 using Tau-5 as the coating antibody and human-specific biotinylated HT7 for detection. For quantification of total soluble and insoluble p-tau, a 96-well half-area plates were coated with 20μg/mL of an in-house p-S181-tau antibody and incubated at 4°C overnight. The next day, the plate was blocked in 3% BSA (RPI Corp.) in PBS for 1 hour at 37°C. Next, tau-178–225 (pS181, pS198, pS199, pS202, pT205) standard peptides and samples were diluted in sample buffer (.25% BSA-PBS, 1x protease inhibitor, 3300mM Tris pH 8.0, PBS), loaded onto the plate, and incubated at 4°C overnight. On the third day, 0.3μg/mL of biotinylated AT8 (pS202/pT205) (Thermo Fisher) was applied to the plate for 1.5 hours at 37°C, then Streptavidin-poly-HRP-40 (1:10000) – (Fitzgerald) was applied for 1.5 hours at room temperature. TMB Superslow Substrate solution (Sigma) was added and the plates were read at 650nm on a Biotek plate reader after developing for 30 minutes at room temperature. All samples were run in triplicate and results are reported from the first freeze-thaw and testing of the samples. Sample were run and quantified by a blinded observer.

Statistics.

GraphPad Prism 5.01 was used to perform statistical analyses. All graphs represent the mean of all samples in each group ± SEM. Sample sizes are reported within each figure and are reflective of individual subjects. All data was normally distributed and equal variances were formally tested. Significance was determined by unpaired Student’s t-test unless otherwise stated in figure legends and p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Data availability.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements.

This study was supported by the National Institute of Aging AG053976 (CEGL), AG059082 (MC), AG059176 (MC), AG026276 (DMH), AG03991 (DMH), AG05681 (DMH), JPB Foundation (DMH), The Donor’s Cure Foundation (JDU), and the Cure Alzheimer’s Fund (DMH, MC). Scanning of immunohistochemistry was performed on the NanoZoomer digital pathology system courtesy of The Hope Center Alafi Neuroimaging Lab. Confocal data was generated on a Zeiss LSM 880 Airyscan Confocal Microscope which was purchased with support from the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (ORIP), a part of the NIH Office of the Director under grant OD021629, and in part with the Washington University Center for Cellular Imaging (WUCCI). The authors would like to specifically thank M. Shih for his help in automating MATLAB scripts for data quantification, K. Campbell for her assistance with figure design in R studio, and L. Changolkar for assistance with the AD-tau preparation.

Footnotes

Competing Interest Statement. DMH and HJ are listed as inventors on a provisional patent from Washington University on TREM2 antibodies. DMH, HJ, and CEGL are listed as inventors on a patent licensed by Washington University to C2N Diagnostics on the therapeutic use of anti-tau antibodies. CEGL is currently an employee at Merck. MC receives research funding from Alector, Amgen, and Ono. DMH co-founded and is on the scientific advisory board of C2N Diagnostics, LLC. C2N Diagnostics, LLC has licensed certain anti-tau antibodies to AbbVie for therapeutic development. DMH is on the scientific advisory board of Proclara and Denali and consults for Genentech, Eli Lilly, and AbbVie.

References.

- 1.Gratuze M, Leyns CEG & Holtzman DM Mol. Neurodegener. 13, 66 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Del-Aguila JL et al. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD 62, 745–756 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Götz J, Ittner LM, Schonrock N & Cappai R Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 4, 1033–1042 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ulrich JD et al. Mol. Neurodegener. 9, 20 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y et al. Cell 160, 1061–1071 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jay TR et al. J. Exp. Med. 212, 287–295 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan P et al. Neuron 92, 252–264 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song WM et al. J. Exp. Med. (2018).doi: 10.1084/jem.20171529 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jay TR et al. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 37, 637–647 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y et al. J. Exp. Med. 213, 667–675 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng-Hathaway PJ et al. Mol. Neurodegener. 13, 29 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parhizkar S et al. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 191–204 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson PT et al. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 71, 362–381 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He Z et al. Nat. Med. 24, 29–38 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Condello C, Yuan P, Schain A & Grutzendler J Nat. Commun. 6, 6176 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo JL et al. J. Exp. Med. 213, 2635–2654 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sadleir KR et al. Acta Neuropathol. (Berl.) 132, 235–256 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leyns CEG et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 114, 11524–11529 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bemiller SM et al. Mol. Neurodegener. 12, 74 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sayed FA et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 115, 10172–10177 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Methods only references.

- 21.Radde R et al. EMBO Rep. 7, 940–946 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turnbull IR et al. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950 177, 3520–3524 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yanamandra K et al. Neuron 80, 402–414 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.