Structured Abstract

Clinical applications of 3D image registration and superimposition have contributed to better understanding growth changes and clinical outcomes. The use of 3D dental and craniofacial imaging in dentistry requires validate image analysis methods for improved diagnosis, treatment planning, navigation and assessment of treatment response. Volumetric 3D images, such as cone-beam computed tomography, can now be superimposed by voxels, surfaces or landmarks. Regardless of the image modality or the software tools, the concepts of regions or points of reference affect all quantitative of qualitative assessments. This study reviews current state of the art in 3D image analysis including 3D superimpositions relative to the cranial base and different regional superimpositions, the development of open source and commercial tools for 3D analysis, how this technology has increased clinical research collaborations from centres all around the globe, some insight on how to incorporate artificial intelligence for big data analysis and progress towards personalized orthodontics.

Keywords: 3D analysis, artificial intelligence, personalized orthodontics

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Development of a method to obtain standardized cephalometric head films in 1931 by Broadbent1 changed the course of dentistry for the first time. This led to the development of innumerous cephalometric image analyses, being the first one by Downs in 1948, with the attempt to measure the face. At first, the goal was to determine an average value of a perfect face and use it as a reference for all treatment plans. Steiner, in 1950s, suggested measurements to diagnose and treatment plan each patient individually by predicting growth changes, as well as treatment outcomes.2 Even though cephalometric values are still used as a normality reference in orthodontics, it is known that variability can occur from each patient, for many different reasons. Innumerous studies have shown that cephalometric numbers differ according to race, genetics backgrounds or orofacial anomalies.3–5

The use of cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) in dentistry has the advantage of having a similar imaging quality as spiral multi-slice CT, with a significantly lower radiation dose, and being able to focus with higher resolution only into a specific anatomic area instead of having the exam of the full face.6,7 It overcomes some inherent flaws of 2D images, such as patient’s head position, superimposition of different anatomical structures, image magnification and distortions.8–11 The broad applicability of the CBCT scans includes assessing skeletal asymmetries, skeletal treatment outcomes, surgical planning, and regional anatomical remodelling. It enables volumetric measurements and allows a detailed assessment of the maxillofacial structures in variable thickness of the axial, coronal and sagittal slices, providing real measurements with no magnification.11,12

Even though CBCT images add information to diagnosis and treatment planning, caution should be taken not to expose the patient to excessive radiation. ALARA, the acronym for “As Low As Reasonably Achievable,” is a fundamental principle for diagnostic radiology. Dose minimization can be achieved by following appropriate radiograph selection criteria after taking a history from the patient, then clinical evaluation by an appropriate healthcare professional.13 Over the past 10 years, studies have reported advantages/disadvantages of the CBCT in relation to regular radiographs and concluded that CBCT should be indicated on specific situations where radiographs only would not be enough to diagnose cleft lip and palate, craniofacial anomalies and impacted canines.14 The overall purpose of this critical review was to explore the literature on three-dimensional analysis.

1.1 |. Three-dimensional superimposition

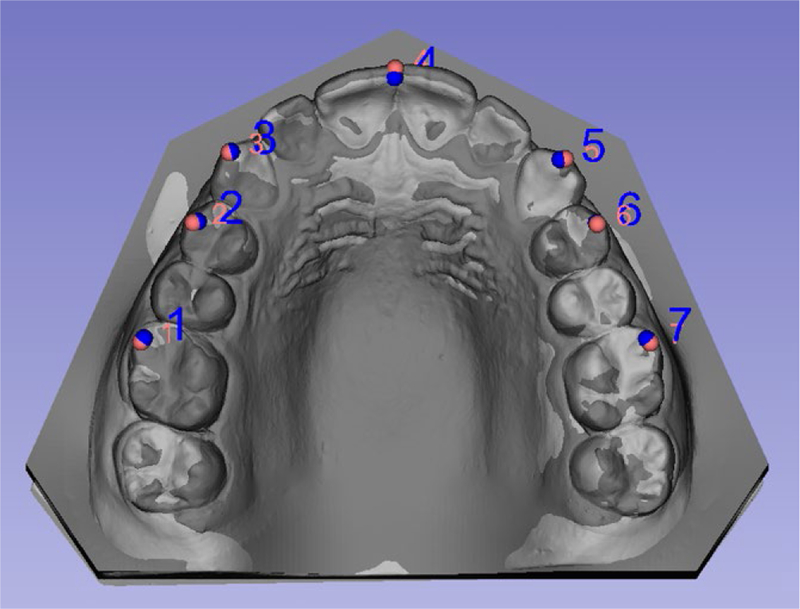

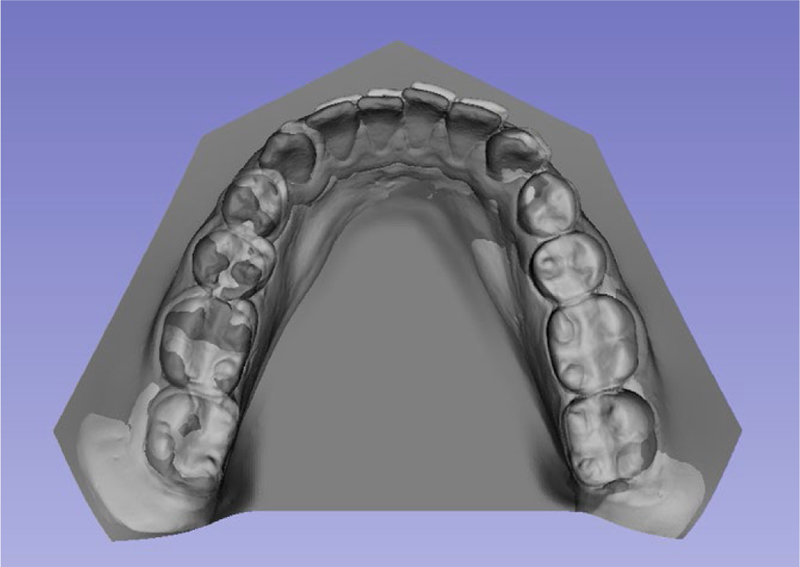

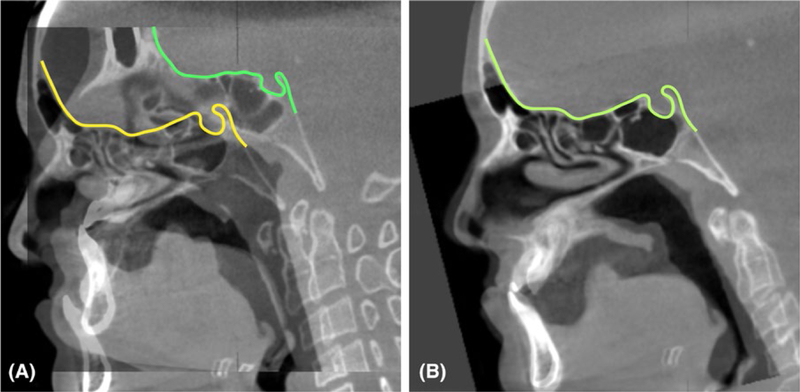

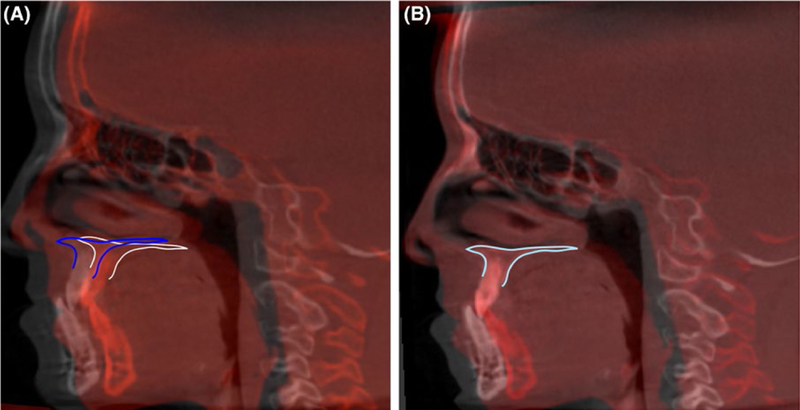

The different methods to superimpose 3D images are voxel-based, landmark-based and surface-based registration. A good superimposition method should be able to register precisely and aid understanding of the changes as a result of growth and/or treatment relative to the structure of reference. According to previous studies, landmark superimposition (Figure 1) is similar to 2D cephalometric but more complex, since identifying the landmarks in 3D images can be challenging.15–17 Surface-based superimposition (Figure 2) uses only the “surface” of the 3D structure and requires high-quality surface for an accurate superimposition.18 voxel-based registration (Figure 3) matches the greyscale values of approximately 300 000 voxels when, for example, the cranial base is used as the structure of reference. It is a completely automated superimposition to avoid observer-dependent technique.15,16,19–21 Studies comparing the three methods suggested that landmark superimposition is the least reliable. Surface registration and voxel-based registration were validated, being the voxel-based registration associated with less variability.17,22,23 It was also suggested that initial approximation of the images is an important step to reduce registration time of the programme and improve the precision of the superimposition.18

FIGURE 1.

Example of superimposition of surface models based on landmarks placed in teeth cusps

FIGURE 2.

Example of surface superimposition of surface models. Computer tries to superimpose the 2 surface models based on its meshes

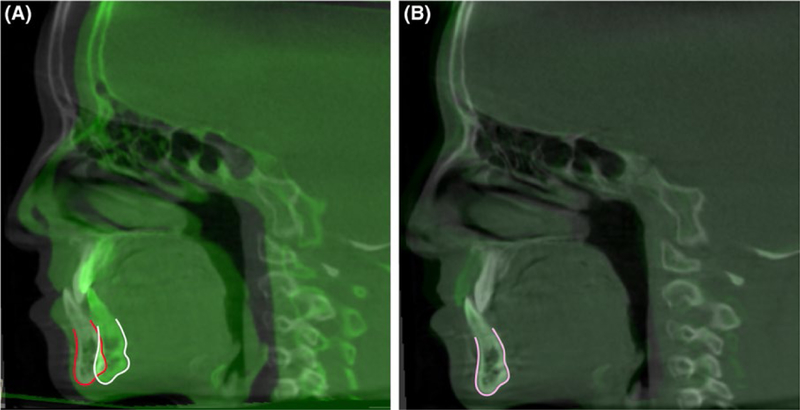

FIGURE 3.

Example of a voxel-based superimposition at the cranial base. A, Cone-beam computed tomographys overlaid before and (B) after superimposing at the cranial base

For 2D superimposition, the American Board of Orthodontics suggests using the anterior cranial base to assess the total superimposition; the anterior surface of zygomatic proves for maxillary superimposition; and the inner contour of the chin and the alveolar canal for mandibular superimposition.17 The translation from 2D to 3D superimposition can be challenging. Studies have attempted to determine the best anatomical structures for 3D superimposition, considering that anatomical structures reported to be stable on lateral cephalograms may not be reliable, because 3D superimposition also includes transverse dimensional changes.24

Cranial base (CB) superimposition (Figure 3) – CB superimposition has been suggested as a reference to assess overall facial growth and treatment outcomes25 considering that the CB grows fast in early postnatal life, reaching 90% of its final size by 4–5 years of age.26 Even though four different methods of CB superimposition have been suggested, studies have concluded that the best fit of the anterior CB was the best superimposition method.27–29 They highlighted that interpretation of the overall facial changes, especially in growing patients, should be made in reference to the CB superimpositions, that means, such superimpositions yield information of facial displacements relative to the CB.

Maxillary superimposition (Figure 4): Superimposition of stable maxillary structures can be used to assess growth and treatment changes within the maxillary dentoalveolar complex. Different regions have been suggested as stable structures, for example, palatal plane, internal palatal structures or different regions of the maxilla, being the gold standard the “implant method” superimposition described by Bjork in 1964.30 Ruellas et al31 tested 2 different areas of the maxilla to be used as reference and concluded that they showed similar results.

FIGURE 4.

Example of maxillary regional superimposition. A, cone-beam computed tomographys overlaid before and (B) after regional superimposition

Mandibular superimposition (Figure 5) – It has been a consensus that the most stable structure in the mandible is the symphysis. Two-dimensional analysis had also suggested that the contour of the mandibular canal and the lower contour of the developing third molar germ before root development could also be stable,32 but recent 3D studies showed that mandibular canal actually relocates laterally during growth,33 and therefore, it would not be a stable anatomic reference for 3D superimposition. The stables regions suggested in the literature is the Mandibular body without teeth, alveolar bone and rami,34 and the chin and symphysis.35

FIGURE 5.

Example of mandibular regional superimposition. A, cone-beam computed tomographys overlaid before and (B) after regional superimposition

1.2 |. Software development

A number of software for image analysis have tools to superimpose different time-point scans. Open-source software have been developed and improved by computer scientists in order to fulfil clinical and researcher’s need. Most commonly used in combination, ITK-Snap and 3DSlicer, allow users to segment volumetric models, approximate and register CBCT scans or surface models, and allow 3D analysis and quantification. Examples of commercial software are as follows: Dolphin Imaging (Dolphin Imaging and Management Solutions, Chatswoth, CA, USA) uses a semiautomatic landmark-based registration process that also allows users to manually adjust the position of CBCT images and visualize the changes between 2 images. InVivo Dental (Anatomage, San Jose, CA, USA) and Maxilim Software (Medicim NV, Mechelen, Belgium) perform a voxel-based registration. The 3dMDvultus (3dMD, Atlanta, Georgia, USA) software uses a surface-based registration process where users manually select the stable anatomic regions to be register when superimposing images taken at different time points. OnDemand3D (Cybermed, Seoul, Korea) software performs a fast superimposition (10–15 seconds), has a user-friendly interface, does not require extensive training and does not require previous segmentation.36,37 So far, our group has worked closely with 3D Slicer Software on developing modules that allow voxel-based superimposition of CBCT scans of growing and non-growing patients, landmark-based superimposition and surface-based superimposition (both with surface landmarks or regions of interest), determine linear and angular measurements in the 3D space and its directional components (antero-posterior, infero-superior and medial-lateral) and create surface models with parametric and non-parametric meshes.

In addition to superimposing CBCT images, one of the goals of image analysis software development is to limit the human errors in image analysis, in an attempt to automate the processes of segmentation and land-mark identification, for example. Automatic landmark detection can be performed with different approaches: training-based, model-based and knowledge-based.38 However, biological variations can make it difficult to detect the precise location of landmark with training or model-based approach, and those authors concluded that even though automated landmark identification would eliminate human error and reduce time and effort involved in manual plotting, until there is a reliable technology, the gold standard will still be human eye of an expert.38

1.3 |. 3D cephalometrics

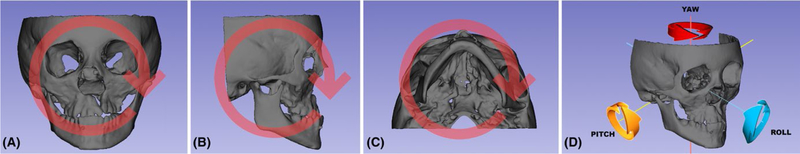

Quantification is an integral and important part of orthodontic diagnosis and planning. Two-dimensional cephalometric analysis is a reliable tool and has been used for over a century. Even with basic flaws, it is still considered a gold standard in image analysis. Translation from 2D to 3D perspective is still a challenge. For start, CBCT images can be assessed in different ways: reformatted conventional radiographs, 2D measurements out of different visualizations (axial, coronal, sagittal or parasagittal slices), and more recently, 3D linear measurements that can be decomposed in the following 3 planes of the space: antero-posterior, infero-superior and medial-lateral; or angular measurements, which are decomposed in pitch, roll and yaw (Figure 6). There are also different ways to place landmarks on the 3D image: on multiplanar views with or without cross-verification on the volume-rendered image, or on surface models,39–45 or even measure angles by moving preexisting planes.

FIGURE 6.

Illustration of (A) roll, (B) pitch, (C) yaw and (D) schematic view of the rotations

3D linear differences between two superimposed time points (T1 and T2) can be measured in each plane of the space. The 3D measurements correspond to the Euclidean distances between the T1 and T2 landmarks.46 Such measurements can be based on thousands of points in triangular meshes automatically defined in the surface models, and calculated in different ways:

1. Colour-coded maps:

Closest point 3D linear distances measure the distances between the closest vertices of the triangular meshes in two surfaces, and not corresponding distances between anatomical points on two or more longitudinally models. The computation of the surface distances can be stored as colour-coded 3D linear distances within.obj,.ply, or.vtk file formats in the user’s software of choice, such as Paraview (http://www.paraview.org; Accessed Aug 03, 2018) or within 3DSlicerCMF https://www.youtube.com/user/DCBIA: Accessed Aug 03, 2018). Even though this standard analysis currently used by most commercial and academic software does not map corresponding surfaces based in anatomical geometry, if used in conjunction with semi-transparent overlays, the graphic display of the colour-coded maps can help clinicians and researchers understand the complex overall surface changes. Localized measurements in closest point colour-coded maps can be made at one point or at any radius defined around the landmark.

2. Shape correspondence:

The SPHARM-PDM module47 in SlicerCMF computes point-based surface models, where all models have the same number of triangular meshes and vertices in corresponding (homologous) locations. Corresponding surface distances and vectors can then be calculated and graphically displayed in SlicerCMF. Localized measurements in closest point colour-coded maps can be made at one point or at any radius defined around the landmark.

3. Quantification of directional changes in each plane of the 3D space:

The components in each plane of the space can be measured based on observer defined landmarks or automatically defined points. The distances between landmarks can be quantified in the transversal (x axis), antero-posterior (y axis) and vertical (z axis) directions using SlicerCMF.

4. 3D Angular Measurements:

3D angular measurements between lines or planes defined in a common 3D coordinate system can be used to quantify pitch, roll and yaw of the model. Evaluations using each of the three views (sagittal, coronal or axial) allow these angles to be measured from different time points. Such angular measurements can be accomplished in SlicerCMF for either characterization of facial morphology at any time point or for comparison of rotational changes between time points. Positive and negative values can be used to indicate rotations in different directions, such clockwise or counterclockwise rotation. The choice of which landmarks or planes should be selected depends on which kind of evaluation researchers would perform to answer their aims. For example, mandibular rotations between two time points can be assessed in the following ways: pitch can be measured as the angle obtained in the sagittal view; roll is measured in the coronal view; and yaw is measured in the axial view.

2 |. APPLICATIONS OF OPEN-SOURCE SOFT WARE TO COLL ABOR ATIVE CLINICAL RESEARCH

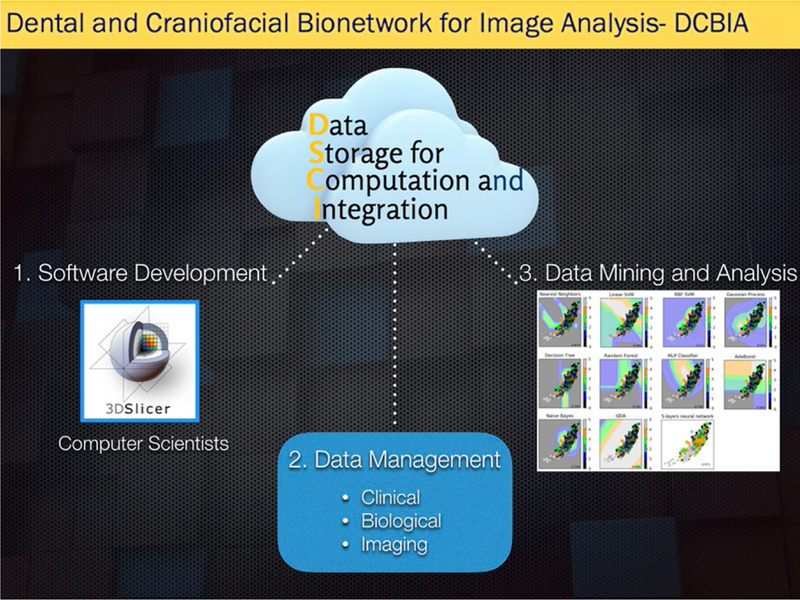

No doubt that 3D technology marked the development of Dentistry, and while some centres have the expertise to further develop tools that can be applied to clinical and research purposes, other centres have the eager to learn and be up to date. This exchange of knowledge leads to multicentres collaboration that can only benefit scientific advances from all parts involved. Dissemination of open-source software not only helps clinicians and researchers access to image analysis tools, but also brings feedback to the biomedical computer scientists. The Dental and Craniofacial Bionetwork for Image Analysis (DCBIA-https://sites.google.com/a/umich.edu/dentistry-image-computing/) group is composed by researchers, clinicians, computer scientists and engineers with the aims to (a) develop image analysis tools specifically to answer dentistry-related clinical questions; (b) train researchers interested in those tools. These efforts resulted in international collaborations with South America, Europe, Asia and Oceania, not to mention other centres within the United States, with a large variety of application of the tools as follows: craniofacial anomalies, asymmetry, surgical outcomes and growth changes.12,48–56 Strengthening the relationship with other centres may eventually facilitate the development of big data that require secure but easily accessible de-identified databases, with storage, mining and analytics capabilities.

3 |. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Artificial intelligence, big data analysis and personalized orthodontics—Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the next step on diagnostic technology. A newly developed neural network-based classification of temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis (TMJ OA) was based on 3D surface meshes of over 250 condyles with different degrees of TMJ OA, as the training dataset for a deep learning algorithm. Ideally, once a new patient condyle surface model is uploaded to the programme, the Slicer ShapeVariation Analyzer (SVA) module can classify the severity of arthritic degeneration of that condyle within five groups of morphological variability.57 The technology behind such classification is a machine learning technique (deep learning). Up to now, we have trained and optimized nine different supervised machine learning algorithms to compare to our current deep neural network: Nearest Neighbors, Linear Support Vector Machine, Radial Basis Function Kernel Support Vector Machine, Gaussian Process, Decision Tree, Random Forest, AdaBoost, Naive Bayes and Quadratic Discriminant Analysis. We chose a deep neural network for classification of 3D meshes shape features, because it’s more modulable, innovative and robust to allow addition of larger data-sets as this work progresses with future collaboration with other clinical centres. With continued enrolment of subjects, neural networks have shown a better performance to build a predictive tool to assess disease progression and explain variability over time. The architecture of the current neural network was trained with high-dimensional imaging data of geometric shape features from 1002 3D meshes vertices of the condyles to classify a given condylar morphology. However, even though patterns of condylar degeneration can be quantified, the bone remodelling pattern obtained from SVA is not as a strong predictor of treatment outcomes neither pinpoint new treatment strategies by itself.

Under this perspective, it is expected that computers using machine learning may, in the future, automatically classify different malocclusions, skeletal discrepancies or dismorphologies of anatomical structures, and even perform automated image cephalometrics. One of the most important aspects on the development of the neural network-based classification is the sample size. Considering the biological variability, the larger the sample, the more accurate the neural network algorithms can become. In order to overcome that, national and international collaboration between centres/researchers is important.

Challenges for such diagnostic advances utilizing big data and artificial intelligence include the need for robust secure web-based systems with storage, mining and analytics capabilities (Figure 7). Additionally, standardization and integration of diagnostic records from clinical information, biological samples and imaging protocols and modalities (such as digital scans, photographs, X-rays, CBCT, CT, MRI and/or ultrasound) are crucial to derive more precise diagnosis. Once biological variability and genetic diverse background are determined or identified by computers, it can lead to a more personalized orthodontics, instead of “one size fits all type” of orthodontics.

FIGURE 7.

Schematic representation of a Data Storage for Computational Integration that is capable to store, mine and analyse data online

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Dr. Marcos Ioshida, Dr. Luciana Bittencourt, Priscille de Dumast and Clement Mirabel for their contribution and the financial support received from National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grant numbers R01EB021391, R01DE024450, R21DE025306).

Funding information

National Institutes of Health, Grant/Award Number: R01EB021391, R01DE024450 and R21DE025306

REFERENCES

- 1.Broadbent BH. A new x-ray technique and its application to orthodontia. Angle Orthod. 1931;1(2):45–66. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steiner CC. The use of cephalometrics as an aid to planning and assessing orthodontic treatment: report of a case. Am J Orthod. 1960;46(10):721–735. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bronfman CN, Janson G, Pinzan A, Rocha TL. Cephalometric norms and esthetic profile preference for the Japanese: a systematic review. Dental Press J Orthod. 2015;20(6):43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janson G, Quaglio CL, Pinzan A, Franco EJ, Freitas MRD. Craniofacial characteristics of Caucasian and Afro-Caucasian Brazilian subjects with normal occlusion. J Appl Oral Sci. 2011;19(2):118–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mars M, James DR, Lamabadusuriya SP. The Sri Lankan Cleft Lip and Palate Project: the unoperated cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate J. 1990;27(1):3–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liang X, Jacobs R, Hassan B, et al. A comparative evaluation of cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) and multi-slice CT (MSCT): part I. On subjective image quality. Eur J Radiol. 2010;75(2):265–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang X, Lambrichts I, Sun Y, et al. A comparative evaluation of cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) and multi-slice CT (MSCT). Part II: on 3D model accuracy. Eur J Radiol. 2010;75(2):270–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lagravere MO, Major PW, Carey J. Sensitivity analysis for plane orientation in three-dimensional cephalometric analysis based on superimposition of serial cone beam computed tomography images. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2010;39(7):400–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeCesare A, Secanell M, Lagravere MO, Carey J. Multiobjective optimization framework for landmark measurement error correction in three-dimensional cephalometric tomography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2013;42(7):20130035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams GL, Gansky SA, Miller AJ, Harrell WE Jr, Hatcher DC. Comparison between traditional 2-dimensional cephalometry and a 3-dimensional approach on human dry skulls. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004;126(4):397–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kapila S, Conley RS, Harrell WE Jr. The current status of cone beam computed tomography imaging in orthodontics. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2011;40(1):24–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Angelopoulos C Cone beam tomographic imaging anatomy of the maxillofacial region. Dent Clin North Am. 2008;52(4):731–752, vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farman AG. ALARA still applies. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100(4):395–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evangelista K, Vasconcelos Kde F, Bumann A, Hirsch E, Nitka M, Silva MA. Dehiscence and fenestration in patients with Class I and Class II Division 1 malocclusion assessed with conebeam computed tomography. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;138(2):133 e131–137; discussion 133–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cevidanes LH, Bailey LJ, Tucker GR Jr, et al. Superimposition of 3D cone-beam CT models of orthognathic surgery patients. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2005;34(6):369–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bookstein F, Schafer K, Prossinger H, et al. Comparing frontal cranial profiles in archaic and modern homo by morphometric analysis. Anat Rec. 1999;257(6):217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghoneima A, Cho H, Farouk K, Kula K. Accuracy and reliability of landmark-based, surface-based and voxel-based 3D cone-beam computed tomography superimposition methods. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2017;20(4):227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bazina M, Cevidanes L, Ruellas A, et al. Precision and reliability of Dolphin 3-dimensional voxel-based superimposition. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2018;153(4):599–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cevidanes LH, Motta A, Proffit WR, Ackerman JL, Styner M. Cranial base superimposition for 3-dimensional evaluation of soft-tissue changes. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137(4 suppl):S120–S129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cevidanes LH, Styner MA, Proffit WR. Image analysis and superimposition of 3-dimensional cone-beam computed tomography models. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129(5):611–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cevidanes LH, Heymann G, Cornelis MA, DeClerck HJ, Tulloch JF. Superimposition of 3-dimensional conebeam computed tomography models of growing patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;136(1):94–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Almukhtar A, Ju X, Khambay B, McDonald J, Ayoub A. Comparison of the accuracy of voxel based registration and surface based registration for 3D assessment of surgical change following orthognathic surgery. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e93402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ponce-Garcia C, Lagravere-Vich M, Cevidanes LHS, de Olivera Ruellas AC, Carey J, Flores-Mir C Reliability of threedimensional anterior cranial base superimposition methods for assessment of overall hard tissue changes: a systematic review. Angle Orthod. 2018;88(2):233–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim I, Oliveira ME, Duncan WJ, Cioffi I, Farella M. 3D assessment of mandibular growth based on image registration: a feasibility study in a rabbit model. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:276128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bjork A, Skieller V. Normal and abnormal growth of the mandible. A synthesis of longitudinal cephalometric implant studies over a period of 25 years. Eur J Orthod 1983;5(1):1–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bambha JK. Longitudinal cephalometric roentgenographic study of face and cranium in relation to body height. J Am Dent Assoc. 1961;63:776–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Efstratiadis SS, Cohen G, Ghafari J. Evaluation of differential growth and orthodontic treatment outcome by regional cephalometric superpositions. Angle Orthod. 1999;69(3):225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Efstratiadis S, Baumrind S, Shofer F, Jacobsson-Hunt U, Laster L, Ghafari J. Evaluation of Class II treatment by cephalometric regional superpositions versus conventional measurements. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;128(5):607–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghafari J, Engel FE, Laster LL. Cephalometric superimposition on the cranial base: a review and a comparison of four methods. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1987;91(5):403–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bjork A Sutural growth of the upper face studied by the implant method. Rep Congr Eur Orthod Soc. 1964;40:49–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Oliveira Ruellas AC, Ghislanzoni LTH, Gomes MR, et al. Comparison and reproducibility of 2 regions of reference for maxillary regional registration with cone-beam computed tomography. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2016;149(4):533–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bjork A Prediction of mandibular growth rotation. Am J Orthod. 1969;55(6):585–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krarup S, Darvann TA, Larsen P, Marsh JL, Kreiborg S. Three-dimensional analysis of mandibular growth and tooth eruption. J Anat. 2005;207(5):669–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Oliveira Ruellas AC, Yatabe MS, Souki BQ, et al. 3D mandibular superimposition: comparison of regions of reference for voxel-based registration. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(6):e0157625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nguyen T, Cevidanes L, Franchi L, Ruellas A, Jackson T. Three-dimensional mandibular regional superimposition in growing patients. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2018;153(5):747–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weissheimer A, Menezes LM, Koerich L, Pham J, Cevidanes LH. Fast three-dimensional superimposition of cone beam computed tomography for orthopaedics and orthognathic surgery evaluation. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44(9):1188–1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi JH, Mah J. A new method for superimposition of CBCT volumes. J Clin Orthod. 2010;44(5):303–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gupta A, Kharbanda OP, Sardana V, Balachandran R, Sardana HK. A knowledge-based algorithm for automatic detection of cephalo-metric landmarks on CBCT images. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2015;10(11):1737–1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gribel BF, Gribel MN, Frazao DC, McNamara JA Jr, Manzi FR. Accuracy and reliability of craniometric measurements on lateral cephalometry and 3D measurements on CBCT scans. Angle Orthod. 2011;81(1):26–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gribel BF, Gribel MN, Manzi FR, Brooks SL, McNamara JA Jr. From 2D to 3D: an algorithm to derive normal values for 3-dimensional computerized assessment. Angle Orthod. 2011;81(1):3–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fuyamada M, Nawa H, Shibata M, et al. Reproducibility of landmark identification in the jaw and teeth on 3-dimensional conebeam computed tomography images. Angle Orthod. 2011;81(5):843–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naji P, Alsufyani NA, Lagravere MO. Reliability of anatomic structures as landmarks in three-dimensional cephalometric analysis using CBCT. Angle Orthod. 2014;84(5):762–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zamora N, Llamas JM, Cibrian R, Gandia JL, Paredes V. A study on the reproducibility of cephalometric landmarks when undertaking a three-dimensional (3D) cephalometric analysis. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2012;17(4):e678–e688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Oliveira AE, Cevidanes LH, Phillips C, Motta A, Burke B, Tyndall D. Observer reliability of three-dimensional cephalometric landmark identification on cone-beam computerized tomography. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107(2):256–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ludlow JB, Gubler M, Cevidanes L, Mol A. Precision of cephalometric landmark identification: cone-beam computed tomography vs conventional cephalometric views. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;136(3):312 e311–310; discussion 312–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khambay B, Ullah R. Current methods of assessing the accuracy of three-dimensional soft tissue facial predictions: technical and clinical considerations. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44(1):132–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gerig G, Jomier M, Chakos M. Valmet: A new validation tool for assessing and improving 3D object segmentation. Paper presented at: International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Solem RC, Ruellas A, Ricks-Oddie JL, et al. Congenital and acquired mandibular asymmetry: mapping growth and remodeling in 3 dimensions. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2016;150(2):238–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gomes LR, Cevidanes LH, Gomes MR, et al. Counterclockwise maxillomandibular advancement surgery and disc repositioning: can condylar remodeling in the long-term follow-up be predicted? Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;46(12):1569–1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nguyen T, Cevidanes L, Paniagua B, Zhu H, Koerich L, De Clerck H. Use of shape correspondence analysis to quantify skeletal changes associated with bone-anchored Class III correction. Angle Orthod. 2014;84(2):329–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.da Motta AT, de Assis Ribeiro Carvalho F, Oliveira AE, Cevidanes LH, de Oliveira Almeida MA. Superimposition of 3D cone-beam CT models in orthognathic surgery. Dental Press J Orthod. 2010;15(2):39–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kwon EK, Louie K, Kulkarni A, et al. The role of Ellis-Van Creveld 2(EVC2) in mice during cranial bone development. Anat Rec (Hoboken). 2018;301(1):46–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chang YJ, Ruellas ACO, Yatabe MS, Westgate PM, Cevidanes LHS, Huja SS. Soft tissue changes measured with three-dimensional software provides new insights for surgical predictions. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;75(10):2191–2201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Atresh A, Cevidanes LHS, Yatabe M, et al. Three-dimensional treatment outcomes in Class II patients with different vertical facial patterns treated with the Herbst appliance. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2018;154(2):238–248 e231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cruz-Escalante MA, Aliaga-Del Castillo A, Soldevilla L, Janson G, Yatabe M, Zuazola RV. Extreme skeletal open bite correction with vertical elastics. Angle Orthod. 2017;87(6):911–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yatabe M, Garib DG, Faco RAS, et al. Bone-anchored maxillary protraction therapy in patients with unilateral complete cleft lip and palate: 3-dimensional assessment of maxillary effects. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2017;152(3):327–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Dumast P, Mirabel C, Cevidanes L, et al. A web-based system for neural network based classification in temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2018;67:45–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]