Prior to the 2016 WHO update, adult astrocytomas were graded exclusively by histologic features, where grade III anaplastic astrocytomas were separated from grade II diffuse infiltrating astrocytomas on the basis of mitotic figures, and glioblastomas (GBM; grade IV) were defined based on the presence of microvascular proliferation and/or tumor necrosis [9]. With the establishment of the 2016 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System guidelines, adult astrocytomas have been segregated into IDH-wildtype and IDH-mutant groups due to the significant prognostic advantage conferred by the presence of an IDH1 or IDH2 mutation [9, 14]. Since this update, much work has been done to establish additional prognostic factors in both IDH-wildtype and IDH-mutant astrocytomas to further subclassify these groups and to aid in the understanding of the underlying biology [1–3, 5].

We have previously investigated the influence of total copy number variation (CNV) on clinical outcome in adult astrocytomas in a variety of cohorts, including cases from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset [10–13]. In IDH-mutant lower-grade gliomas (grades II and III), elevated total CNV (16–22%) is associated with poor clinical outcome (defined in these earlier reports as rapid progression to GBM and patient survival intervals < 24 months) compared to histologically similar tumors with lower total CNV (8–10%), and the level of total genomic CNV is inversely correlated with both progression-free and overall survival in linear regression models. Total CNV appears to have no prognostic value in IDH-wildtype astrocytoma or IDH-mutant GBM groups [10–12].

Unlike other prognostic factors, however, CNV is more difficult to utilize clinically, as it is not a simple “present-or-absent” model like IDH1/2 mutations. To address this, we used the cBioPortal interface [4, 7] to reanalyze the survival and CNV data from IDH-mutant grade II/III astrocytomas in our previous publications (n = 67) [10, 12] to establish a simple and reasonable threshold that could be used to reliably predict clinical outcomes within the IDH-mutant, 1p/19q-retained lower-grade astrocytoma subgroup. We defined CNV as the percentage of the genome with alterations meeting the criteria of log2 > 0.3; copy number data was derived from Affymetrix SNP6 (Santa Clara, CA, USA) and Agilent 224 K/415 K (Santa Clara, CA, USA) platforms [1]. Preliminary data from our previous studies suggested potential clinically useful CNV cutoff levels of 10, 15, and 18% [10, 12].

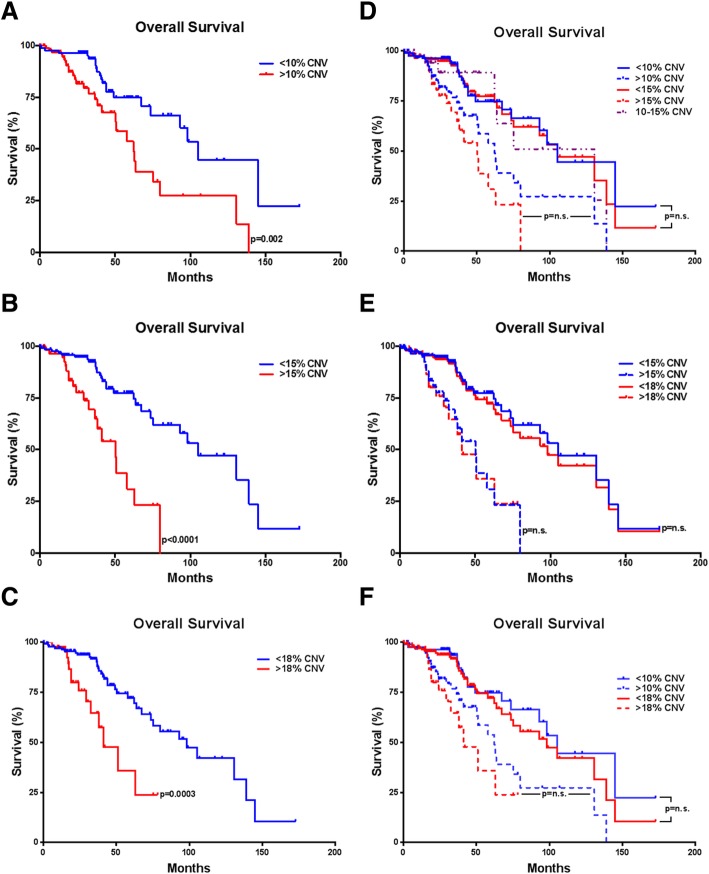

Using Kaplan-Meier analysis on cases from our previous publications and additional cases from the TCGA database (total n = 194 IDH-mutant lower-grade astrocytomas), we evaluated each of these potential thresholds. There was a significant survival difference between cases at each threshold evaluated: 10% (< 10% CNV, 105.2 month median survival; > 10% CNV, 62.2 month median survival; p = 0.0020) (Fig. 1a), 15% (< 15% CNV, 105.2 month median survival; > 15% CNV, 50.1 month median survival; p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1b), and 18% (< 18% CNV, 98.2 month median survival; > 18% CNV, 41.2 month median survival; p = 0.0003) (Fig. 1c). There was no significant patient survival difference in the 10% vs 15% CNV thresholds, and an additional group with CNV between 10 and 15% (130.8 month median survival) was not significantly different than the group with < 10% CNV (p = 0.6003), however these cases had significantly better clinical outcomes than cases with > 15% CNV (p = 0.0113) (Fig. 1d), suggesting 15% as the better cutoff point. No significant difference was found between the 15 and 18% thresholds (Fig. 1e) or the 10 and 18% thresholds (Fig. 1f), however the 18% threshold would exclude > 50% of cases from one of our previously reported poorly performing cohorts [12]. The 15% CNV threshold had a sensitivity of 85%, specificity of 90%, positive predictive value (PPV) of 77%, and negative predictive value (NPV) of 94%. The 10% CNV threshold had a relatively low specificity (57%) and PPV (32%) and the 18% CNV threshold had a lower sensitivity (75%) (Table 1). Based on these models, we suggest that a judicious CNV cutoff for predicting poor clinical outcome in adult IDH-mutant lower-grade astrocytomas would be around 15%. It is important to note that these results are from a single, albeit relatively large, data source and as such should be validated prospectively. It would be of interest to evaluate our suggested cutoff using other large-scale cohorts to confirm our recommendation of 15% CNV or alternatively help improve the robustness of our model and refine this threshold.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves demonstrating survival differences using 10% overall CNV as a threshold for poor clinical outcome (p = 0.0020) (a), using 15% overall CNV as a threshold for poor clinical outcome (p < 0.0001) (b), and using 18% overall as a threshold for poor clinical outcome (p = 0.0003) (c). Kaplan-Meier survival curves demonstrating no significant difference between 10 and 15% CNV thresholds (additionally, < 10% vs 10–15% p = 0.6003; 10–15% vs > 15% p = 0.0113) (d), no significant difference between 15 and 18% CNV thresholds (< 15% vs < 18, p = 0.5949; > 15% vs > 18% p = 0.9015) (e), and no significant difference between 10 and 18% CNV thresholds (< 10% vs < 18, p = 0.4791; > 10% vs > 18% p = 0.2672) (f). Copy number variation is expressed as a percentage of the total genome, log2 > 0.3 as reported previously [10, 12]

Table 1.

Comparison of 10, 15, and 18% CNV thresholds

| CNV Level | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10% | 88% | 57% | 32% | 96% |

| 15% | 85% | 90% | 77% | 94% |

| 18% | 75% | 93% | 75% | 93% |

While total CNV is not currently a regularly measured factor at the time of diagnosis, recent proof-of-concept studies have shown that genetic and epigenetic variables such as CNV and various mutations, individual gene amplifications/deletions, and chromosomal gains/losses can be identified rapidly [6, 8], and thus CNV estimates may soon be available within days of histologic diagnosis, raising the possibility for its use as an additional clinical factor guiding prognosis in IDH-mutant lower-grade astrocytomas.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Michel Nasr, Elizabeth Rosaschi, and the Department of Pathology at SUNY Upstate Medical University for publication costs.

Authors’ contributions

Conception of the work: KM, MS, TER; Design of the work: KM, MS, KG, KJH, JMW, TER.; Acquisition/analysis/interpretation of the data: KM, MS, KG, KJH, JMW, TER; Creation of new software used in the work: not applicable; Drafted the work or substantively revised it: KM, JMW, TER All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

M.S. is supported in part by a Friedberg Charitable Foundation.

Availability of data and materials

The full dataset used in this study is freely available at www.cbioportal.org and https://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/organization/ccg/research/structural-genomics/tcga.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Kanish Mirchia, Email: MirchiaK@Upstate.edu.

Matija Snuderl, Email: Matija.Snuderl@NYULagone.org.

Kristyn Galbraith, Email: GalbraKr@Upstate.edu.

Kimmo J. Hatanpaa, Email: Kimmo.Hatanpaa@UTSouthwestern.edu

Jamie M. Walker, Email: WalkerJ1@uthscsa.edu

Timothy E. Richardson, Email: RichaTim@Upstate.edu

References

- 1.Brennan CW, Verhaak RG, McKenna A, Campos B, Noushmehr H, Salama SR, Zheng S, Chakravarty D, Sanborn JZ, Berman SH, et al. The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell. 2013;155:462–477. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Brat DJ, Verhaak RG, Aldape KD, Yung WK, Salama SR, Cooper LA, Rheinbay E, Miller CR, Vitucci M, et al. Comprehensive, integrative genomic analysis of diffuse lower-grade gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2481–2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ceccarelli M, Barthel FP, Malta TM, Sabedot TS, Salama SR, Murray BA, Morozova O, Newton Y, Radenbaugh A, Pagnotta SM, et al. Molecular profiling reveals biologically discrete subsets and pathways of progression in diffuse glioma. Cell. 2016;164:550–563. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cimino PJ, Zager M, McFerrin L, Wirsching HG, Bolouri H, Hentschel B, von Deimling A, Jones D, Reifenberger G, Weller M, et al. Multidimensional scaling of diffuse gliomas: application to the 2016 World Health Organization classification system with prognostically relevant molecular subtype discovery. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2017;5:39. doi: 10.1186/s40478-017-0443-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Euskirchen P, Bielle F, Labreche K, Kloosterman WP, Rosenberg S, Daniau M, Schmitt C, Masliah-Planchon J, Bourdeaut F, Dehais C, et al. Same-day genomic and epigenomic diagnosis of brain tumors using real-time nanopore sequencing. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;134:691–703. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1743-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, Sun Y, Jacobsen A, Sinha R, Larsson E, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 2013;6:pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hench J, Bihl M, Bratic Hench I, Hoffmann P, Tolnay M, Bosch Al Jadooa N, Mariani L, Capper D, Frank S. Satisfying your neuro-oncologist: a fast approach to routine molecular glioma diagnostics. Neuro-Oncology. 2018;20:1682–1683. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noy128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Kleihues P, Ellison DW. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:803–820. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mirchia K, Sathe AA, Walker JM, Fudym Y, Galbraith K, Viapiano MS, Corona RJ, Snuderl M, Xing C, Hatanpaa KJ, et al. Total copy number variation as a prognostic factor in adult astrocytoma subtypes. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2019;7:92. doi: 10.1186/s40478-019-0746-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richardson TE, Patel S, Serrano J, Sathe AA, Daoud EV, Oliver D, Maher EA, Madrigales A, Mickey BE, Taxter T, et al. Genome-wide analysis of glioblastoma patients with unexpectedly long survival. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2019;78:501–507. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nlz025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richardson TE, Sathe AA, Kanchwala M, Jia G, Habib AA, Xiao G, Snuderl M, Xing C, Hatanpaa KJ. Genetic and epigenetic features of rapidly progressing IDH-mutant Astrocytomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2018;77:542–548. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nly026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richardson TE, Snuderl M, Serrano J, Karajannis MA, Heguy A, Oliver D, Raisanen JM, Maher EA, Pan E, Barnett S, et al. Rapid progression to glioblastoma in a subset of IDH-mutated astrocytomas: a genome-wide analysis. J Neuro-Oncol. 2017;133:183–192. doi: 10.1007/s11060-017-2431-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan H, Parsons DW, Jin G, McLendon R, Rasheed BA, Yuan W, Kos I, Batinic-Haberle I, Jones S, Riggins GJ, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:765–773. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The full dataset used in this study is freely available at www.cbioportal.org and https://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/organization/ccg/research/structural-genomics/tcga.