Abstract

Background.

Patient success with atrial fibrillation (AF) requires adequate health literacy to understand the disease and rationale for treatment. We hypothesized that individuals receiving treatment for AF would have increased knowledge about AF and that such knowledge would be modified by education and income.

Methods.

We enrolled adults with AF receiving anticoagulation at ambulatory clinic sites. Participants responded to survey items encompassing the definitions of AF and stroke, the rationale for anticoagulation, and an estimation of their annual stroke risk. We examined responses in relation to household income and education in multivariable-adjusted models.

Results.

We enrolled 339 individuals (age 72.0±10.1; 43% women) with predominantly lower annual income ($20-49,999, n=99, 29.2%) and a range of educational attainment (high school or vocational, n=117, 34.5%). Participants demonstrated moderate AF knowledge (1.7±0.6; range 0-2) but limited knowledge about anticoagulation (1.3±0.7; range 0-3) or stroke (1.5±0.8; range 0-3). Income was not associated with improvement in AF (P=0.32 for trend), anticoagulation (P=0.27) or stroke knowledge (P=0.26). Individuals with bachelor or graduate degree had greater AF (1.8±0.5) and stroke (1.6±0.8) knowledge relative to those with high school or vocational training (1.4±0.7 and 1.2±0.9; P<0.01, both estimates). Education was not associated with understanding the rationale for anticoagulation. Most participants (230, 68%) estimated their annual stroke risk as ≥15%.

Conclusions.

We identified consistent, fundamental gaps in disease-specific knowledge in a cohort of adults receiving treatment for non-valvular AF. Improved patient understanding of this complex and chronic disease may enhance shared decision-making, patient engagement, anticoagulation adherence, and clinical outcomes in AF.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Shared decision making, health literacy, education, income

INTRODUCTION

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common and highly morbid condition associated with significant cardiac and non-cardiac complications including ≥15% of all strokes in the United States.1 AF is a challenging disease for patients to manage as it requires ability to access healthcare resources such as specialty care, proficiency in symptom recognition and reporting, management of complex medications including anticoagulation, and participation in multifaceted treatment plans. Individuals with AF may not have sufficient health literacy or knowledge about AF necessary to participate in the array of complex activities demanded by this condition. Further, individuals may be unable to participate in the shared decision-making about anticoagulation mandated by professional society guidelines.2,3

Prior literature has revealed that patients generally have a poor understanding of AF.4,5 Several surveys performed demonstrate that between 15%-30% of patients are unaware of their AF diagnosis.6,7 Lack of insight into severity of disease is also widely prevalent.8 Important knowledge deficits include understanding the indication for anticoagulation as preventative therapy for stroke, appropriate utilization of anticoagulants, and awareness of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants.9

Health literacy, the degree to which individuals are able to access and process basic health information and services and thereby participate in health-related decisions, impacts knowledge of health conditions and has particular relevance to AF.10,11 Limited health literacy in AF has been associated with decreased awareness of diagnosis and challenges with anticoagulation that include indication, knowledge of adverse side effects, and decreased adherence to anticoagulation.5,6,12,13 Low educational attainment and low income negatively influence health literacy but study of the impact of these social determinants in AF remains limited. We examined how education and income – fundamental social determinants of health – relate to patient knowledge of AF, its treatments, and complications.

We investigated AF-associated knowledge by assessing the ability to define AF, identify indication for anticoagulation, accurately define stroke, and estimate annual stroke risk. We hypothesized that patients with higher education or income would demonstrate greater knowledge of AF care compared to those with either lower education or income.

METHODS

Cohort Selection

We prospectively enrolled a cohort of adults receiving care for non-valvular AF and prescribed oral anticoagulation at 4 ambulatory sites affiliated with the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) in Pittsburgh, PA.14 We identified participants as having non-valvular AF and receiving oral anticoagulation from the electronic health record and recruitment at clinical visits, referral by physician or other care provider, or self-referral via a web-based clinical research portal. Participants were deemed eligible for participation if they were adults (age≥18 years), had been prescribed oral anticoagulation for non-valvular AF, and had a CHA2DS2-VaSc15 (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes, stroke, vascular disease [history of MI, PVD, or aortic atherosclerotic disease], and sex category) score ≥2. Individuals were required to speak English at a level adequate for informed consent and participation in this study. Those with AF within 30 days of cardiovascular surgery were excluded. From 2016-2018 we identified 1093 individuals as eligible and approached 486 who were invited to participate. A final cohort of 339 individuals agreed to participate in the assessments described here.

Age, sex, race, body mass index, and medical comorbidities including, congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, stroke/transient ischemic attack, and vascular disease were collected by review of the electronic health record. Prescription of oral anticoagulation and the specific agent were ascertained from the electronic health record and confirmed by the participant. We ascertained education and annual estimated household income by self-report. Education was categorized according to the highest level of education completed as high school or vocational, some college, bachelor’s degree, or graduate degree. We categorized income as <$20,000, $20,000-49,999, $50,000-99,000, and >$100,000.

Outcomes Ascertainment

We employed four questions to quantify knowledge about AF, its treatments, and complications. These questions were derived from a prior assessment of the relation of health literacy to warfarin knowledge and similar to those utilized in a validated “atrial fibrillation knowledge scale.”5,16 The questions were (1) “What is atrial fibrillation?”; (2) “Why are you taking [name of anticoagulant]?”; and (3) “What is a stroke?”. These three questions were utilized to determine whether patients could accurately define AF, identify the rationale for anticoagulation, and accurately define a stroke, respectively. The final question asked participants to estimate their annual risk of stroke by asking, “What is your percent annual stroke risk?” Individuals who indicated they did not understand percentage were asked to rate their likelihood of stroke in the next year from 0 (not at all likely) to 100 (extremely likely or definite).

Responses to questions were recorded and transcribed and then scored. Supplementary Table 1 provides the items with sample responses to demonstrate the approach for scoring by response. Individuals were assigned a score for each response depending on the content of the response. For Question 1 “What is atrial fibrillation?” the score range was 0 to 2. Participants received a point for identifying the condition as associated with the heart (1 point) and as a heart rhythm disorder or irregular heartbeat (1 point). For Question 2 “Why are you taking [name of anticoagulant]?” the score range was 0-3. Participants received a point each for reporting the goal of anticoagulation (stroke prevention), the underlying condition (AF), and the mechanism of action (prevention of the formation of a thrombus or “blood clot”). For Question 3 “What is a stroke?” the score range was 0-3. Participants received a point each for identifying involvement of the brain, describing disruption of oxygen or blood flow, and the potential signs or symptoms of stroke. Two reviewers (ARL and AMP) scored the transcribed responses independently and discrepancies were adjudicated by a third reviewer (JWM). Responses to Question 4, “What is your percent annual stroke risk?” were reported continuously from 0 to 100.

Statistical Analysis

We summarized the distributions of categorical variables as frequency (percentage) and continuous variables using mean ± SD. Differences in baseline characteristics between education groups were tested using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables. Our primary analysis was the association of education and income with responses to the AF-associated knowledge questions in a cohort of individuals undergoing treatment for prevalent AF. Our secondary analysis was the evaluation of patients’ projected stroke risk by CHA2DS2-VASc score versus their estimated stroke risk. We evaluated distribution of knowledge scores by both educational status and income category with differences assessed by univariable and multivariable linear regression. Our multivariable-adjusted models consisted in adjustment for age, sex, and race (model 1); age, sex, race, body mass index, congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, and vascular disease (model 2); followed by inclusion of education or income (model 3), depending on the independent variable being examined. We examined the distribution of estimated annual stroke risk by both educational status and income category with percentage estimation of stroke risk categorized as 0-1.9, 2-4.9, 5-9.9, 10-19, 20-29, 30-39, 40-49, and >50. As secondary analyses, we examined estimated versus projected stroke risk by education and income in models that categorized individuals by overestimation of stroke risk using cut-points of >10%, >20%, and ≥50%.

RESULTS

A total of 339 patients (mean age 72.0±10.1 years; 42.5% women) participated in the study as summarized in Table 1. A relatively high proportion (46%) had achieved a bachelor’s or graduate degree. Education was distributed by income, with a greater proportion of individuals with higher education belonging to higher income categories. Across educational categories, the prevalence of congestive heart failure, body mass index, and CHA2DS2-VASc score were increased in those with high school or vocational degrees compared to those with some college, bachelor’s, or graduate degrees. Other covariates including hypertension, diabetes, stroke, and vascular disease did not significantly vary by educational category.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants according to education.

| All Patients | HS or Vocational | Some College | Bachelor’s | Graduate | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of participants | 339 | 117 | 67 | 79 | 76 | |

| Age | 72.0 ± 10.1 | 73.5 ± 10.4 | 69.3 ± 10.7 | 72.6 ± 10.2 | 71.3 ± 8.78 | 0.044 |

| Sex (Male) | 195 (57.5) | 66 (56.4) | 37 (55.2) | 46 (58.2) | 46 (60.5) | 0.92 |

| Race | 0.37 | |||||

| White | 319 (94.1) | 109 (93.2) | 64 (95.5) | 75 (94.9) | 71 (93.4) | |

| Black | 13 (3.8) | 7 (6.0) | 3 (4.5) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (2.6) | |

| Other | 5 (1.5) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.5) | 2 (2.6) | |

| BMI | 31.2 ± 7.2 | 32.7 ± 8.0 | 32.7 ± 7.5 | 29.2 ± 6.7 | 29.6 ± 5.2 | 0.001 |

| CHF | 62 (18.3) | 31 (26.5) | 14 (20.9) | 13 (16.5) | 4 (5.3) | 0.003 |

| HTN | 241 (71.1) | 84 (71.8) | 50 (74.6) | 54 (68.4) | 53 (69.7) | 0.89 |

| DM | 81 (23.9) | 35 (29.9) | 15 (22.4) | 19 (24.1) | 12 (15.8) | 0.18 |

| Stroke/TIA | 25 (7.4) | 10 (8.5) | 7 (10.4) | 5 (6.3) | 3 (3.9) | 0.46 |

| Vascular Disease | 65 (19.2) | 27 (23.1) | 9 (13.4) | 17 (21.5) | 12 (15.8) | 0.32 |

| Annual Household Income | <0.001 | |||||

| <$19,999 | 35 (10.3) | 21 (17.9) | 7 (10.4) | 6 (7.6) | 1 (1.3) | |

| $20,000-49,999 | 99 (29.2) | 47 (40.2) | 24 (35.8) | 18 (22.8) | 10 (13.2) | |

| $50,000-99,999 | 97 (28.6) | 28 (23.9) | 22 (32.8) | 29 (36.7) | 18 (23.7) | |

| >$100,000 | 64 (18.9) | 4 (3.4) | 9 (13.4) | 17 (21.5) | 34 (44.7) | |

| Not Reported | 44 (13.0) | 17 (14.5) | 5 (7.5) | 9 (11.4) | 13 (17.1) | |

| CHA2DS2-VASC | 3.10 ± 1.61 | 3.41 ± 1.70 | 2.97 ± 1.63 | 3.13 ± 1.64 | 2.70 ± 1.33 | 0.022 |

Values correspond to N (percentage) unless otherwise stated. BMI, body mass index; CHF, congestive heart failure; HTN, hypertension; DM, diabetes mellitus; TIA, transient ischemic attack; CHA2DS2-VASc: congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 years, diabetes mellitus, stroke/transient ischemic attack, vascular disease, age 65–75 years, and sex category. SD: standard deviation.

Study participants exhibited moderate knowledge of AF but had limited knowledge of the rationale for anticoagulation and understanding of stroke. The mean score for “What is atrial fibrillation?” was 1.65±0.60 (maximum score 2); for the rationale for anticoagulation was 1.25±0.67 (maximum score 3); and for “What is a stroke?” was 1.46±0.81 (maximum score 3). Table 2 summarizes the relation of education to these 3 items. Higher education level was associated with increased ability to accurately define AF (1.78±0.45) and stroke (1.6±0.8), relative to those with high school or vocational training (1.4±0.7 and 1.2±0.9, respectively; P<0.001 for both estimates). However, higher education was not associated with increased ability to identify the rationale for anticoagulation, an observation that was not affected or attenuated by multivariable adjustment. There was no association between income and knowledge of AF (P=0.32 for trend), the rationale for anticoagulation (P=0.27), or stroke (P = 0.26) as summarized by Supplementary Table 2.

Table 2.

Distribution of responses to knowledge assessment by Education.

| All Participants | HS or Vocational | Some College | Bachelor’s | Graduate | P-Value | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What is atrial fibrillation? | 1.65 ± 0.60 | 1.44 ± 0.72 | 1.66 ± 0.62 | 1.81 ± 0.43 | 1.78 ± 0.45 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 0 | 23 (6.8%) | 16 (13.7%) | 5 (7.5%) | 1 (1.3%) | 1 (1.3%) | ||||

| 1 | 74 (21.8%) | 33 (28.2%) | 13 (19.4%) | 13 (16.5%) | 15 (19.7%) | ||||

| 2 | 242 (71.4%) | 68 (58.1%) | 49 (73.1%) | 65 (82.3%) | 60 (78.9%) | ||||

| Why are you taking [name of anticoagulant]? | 1.25 ± 0.67 | 1.16 ± 0.67 | 1.34 ± 0.71 | 1.25 ± 0.67 | 1.29 ± 0.65 | 0.32 | 0.51 | 0.65 | 0.68 |

| 0 | 35 (10.3%) | 13 (11.1%) | 8 (11.9%) | 8 (10.1%) | 6 (7.9%) | ||||

| 1 | 195 (57.5%) | 77 (65.8%) | 29 (43.3%) | 45 (57.0%) | 44 (57.9%) | ||||

| 2 | 99 (29.2%) | 22 (18.8%) | 29 (43.3%) | 24 (30.4%) | 24 (31.6%) | ||||

| 3 | 10 (2.9%) | 5 (4.3%) | 1 (1.5%) | 2 (2.5%) | 2 (2.6%) | ||||

| What is a stroke? | 1.46 ± 0.81 | 1.19 ± 0.88 | 1.48 ± 0.77 | 1.54 ± 0.80 | 1.76 ± 0.63 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 0 | 48 (14.2%) | 29 (24.8%) | 8 (11.9%) | 9 (11.4%) | 2 (2.6%) | ||||

| 1 | 110 (32.4%) | 44 (37.6%) | 22 (32.8%) | 24 (30.4%) | 20 (26.3%) | ||||

| 2 | 159 (46.9%) | 37 (31.6%) | 34 (50.7%) | 40 (50.6%) | 48 (63.2%) | ||||

| 3 | 22 (6.5%) | 7 (6.0%) | 3 (4.5%) | 6 (7.6%) | 6 (7.9%) |

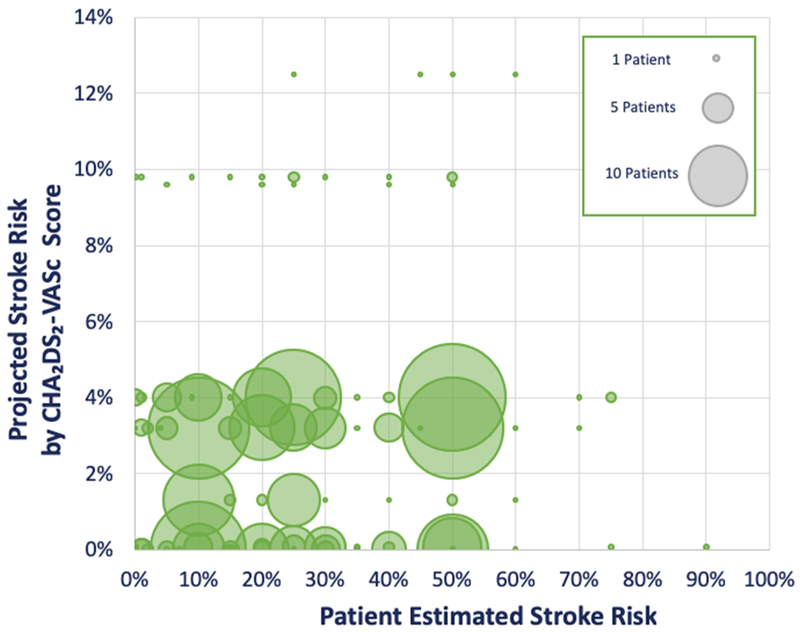

Table 3 summarizes the association between education and participants’ projected stroke risk as ascertained using the CHA2DS2-VASc score compared to cohort participants’ own estimation of their annual stroke risk. Across all educational levels, individuals overestimated their annual risk of stroke with 69.9% over-estimating their risk by >10%, 50% by >20%, and 2.9% by >50%. However, higher level of education was significantly associated with lower likelihood of overestimating stroke risk; patients with lower levels of education were more likely to overestimate their stroke risk (P<0.001). The discrepancy between estimated and projected stroke risk is presented graphically in the Figure. The association between income and participants’ projected versus estimated stroke risk is summarized in Supplementary Table 3. Income was not consistently associated with ability to more accurately predict percent annual stroke risk.

Table 3.

Participant estimation of annual stroke risk by self-reported educational level.

| All Participants | HS or Vocational | Some College | Bachelor’s | Graduate | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Participants | 339 | 117 | 67 | 79 | 76 | |

| Estimated Percent Annual Stroke Risk | <0.001 | |||||

| 0-1.9 | 20 (5.9%) | 8 (6.8%) | 3 (4.5%) | 5 (6.3%) | 4 (5.3%) | |

| 2-4.9 | 5 (1.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (5.3%) | |

| 5-9.9 | 17 (5.0%) | 3 (2.6%) | 1 (1.5%) | 6 (7.6%) | 7 (9.2%) | |

| 10-19 | 81 (23.9%) | 14 (12.0%) | 14 (20.9%) | 23 (29.1%) | 30 (39.5%) | |

| 20-29 | 90 (26.5%) | 25 (21.4%) | 23 (34.3%) | 26 (32.9%) | 16 (21.1%) | |

| 30-39 | 32 (9.4%) | 13 (11.1%) | 10 (14.9%) | 5 (6.3%) | 4 (5.3%) | |

| 40-49 | 20 (5.9%) | 13 (11.1%) | 4 (6.0%) | 2 (2.5%) | 1 (1.3%) | |

| >50 | 74 (21.8%) | 41 (35.0%) | 11 (16.4%) | 12 (15.2%) | 10 (13.2%) | |

| Over-Estimated Stroke Risk ≥10% | 237 (69.9%) | 98 (83.8%) | 52 (77.6%) | 50 (63.3%) | 37 (48.7%) | <0.001 |

| Over-Estimated Stroke Risk ≥20% | 171 (50.4%) | 83 (70.9%) | 39 (58.2%) | 30 (38.0%) | 19 (25.0%) | <0.001 |

| Over-Estimated Stroke Risk ≥50% | 10 (2.9%) | 4 (3.4%) | 5 (7.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.3%) | 0.046 |

Figure 1:

Projected versus Patient Estimated Percent Annual Stroke Risk

DISCUSSION

We observed significant gaps in knowledge essential to AF in this investigation of individuals receiving care for AF. Specifically, we observed that higher education level was associated with increased ability to accurately define AF and stroke but no increased ability to correctly identify indication for anticoagulation. However, education had only a small effect on the results and no influence on understanding the rationale for anticoagulation. Higher income level was not associated with increased AF knowledge in any of the three domains; this lack of association between income and any measure of disease-specific knowledge was unexpected and contrary to our hypothesis. Most importantly, study participants markedly overestimated annual stroke risk, regardless of income and education. Our findings suggest that individuals in this cohort had limited fundamental disease-specific knowledge about AF. Our results are particularly noteworthy as we selected our cohort from individuals actively receiving treatment for AF.

We consider the consistent overestimation of annual stroke risk, regardless of educational attainment or income level, as the most important finding in our study. We found that 70% of patients over-estimated their annual risk of stroke by >10%, 50% by >20%, and 3% by >50%. Clearly, these results suggest a failure to educate patients meaningfully on the rationale for anticoagulation and relevance of stroke prevention. Individual estimates of stroke risk contrast with those predicted by the CHA2DS2-VASc score15 that is widely relied on in clinical practice to recommend initiation of anticoagulation.

In the U.S., 65% of adults are reported to have a significant deficiency in numeracy, which likely contributes to difficulty in conceptualizing percent annual stroke risk and the discrepancy in projected versus patient-estimated risk that we identified here.17 For many patients, perceived increased stroke risk likely skews the risk/benefit ratio in favor of pursuing anticoagulation therapy. The fundamental gap between the clinician estimate of stroke risk and the patient’s perception of that risk impedes engaging in the shared decision making mandated by professional society guidelines.3 Our findings highlight the importance of patient education about risk for stroke in AF.

Our work demonstrates prevalence of low disease-specific knowledge in AF and suggests that high educational attainment and income are not adequately protective. Despite the substantial resources that patients with high educational attainment and income have, this study highlights that these advantages may not be enough to overcome limited numeracy and health literacy. As such, these findings underscore the fundamental challenges of health literacy and shared decision making to AF. An American Heart Association Scientific Statement has broadly summarized the wide prevalence of limited health literacy in cardiovascular disease assessment and management.18 While health literacy has had limited study in AF,10 several studies have underscored the significance of health literacy as a challenge and obstacle for individuals with AF. One survey identified that up to 29% of patients were unaware having a diagnosis of AF and 34% unaware that AF could cause stroke. Over half (>50%) of individuals prescribed warfarin or a direct-acting oral anticoagulant were unsure of what to do after missing a medication dose.7 An international survey revealed that about 25% of patients felt unable to explain their diagnosis of AF, with the authors concluding similar to our study that patients demonstrated a poor understanding of AF management and treatment.4 In a study of health literacy in a large, ethnically diverse cohort of adults with AF, individuals with limited health literacy were less likely to be aware of having a diagnosis of AF compared to those with adequate health literacy.6 Progressing our understanding of the effects of health literacy are paramount to improve patient-centered care, health outcomes, and equity in health care delivery for AF.

Adequate health literacy is a prerequisite to participation in shared decision making, and is crucial to AF care. The landmark report issued by the National Academy of Medicine (previously the Institute of Medicine), “Crossing the Quality Chasm,” notes that patient-centered care is vital to improving the quality of healthcare in the US.19 Shared decision-making has been described as the “pinnacle” of patient-centered care and in the treatment of AF, antithrombotic therapy based on shared decision-making has garnered a class I recommendation.20 The goal of shared decision-making is to increase the likelihood that patients receive the care they need in a manner consistent with evidence-based practice while taking into account their values and preferences. Shared decision-making is characterized by patient and physician partnership with the exchange of physician’s expertise and patients’ experience and knowledge of their disease, joint deliberation when weighing of risks and benefits, and agreement on treatment to implement.21 The process of shared decision making is especially important when there are multiple reasonable treatment paths, each of which includes the possibility of therapeutic effects and side effects.22 In AF, treatments are complex and may require long-term (possibly lifelong) adherence, as is the case with anticoagulation. Critical deficiencies in AF knowledge, as demonstrated here, may threaten any attempt at shared decision-making. We would assert that the absence of disease-specific knowledge that we identified precludes patients’ ability to participate in the “meeting of experts” required for shared decision making.

Our analysis had several strengths. We recruited individuals receiving active care for AF within a single, large regional health care system. We expect that treatment for AF would have limited variability in such a setting. Our scoring method of participant responses utilized 2 independent reviewers, blinded to each other’s scoring, with adjudication by a third. We also recognize important limitations of our study. First, our cohort size is limited, and participants were recruited at selected ambulatory sites belonging to a large, regional health care system. This geographic and institutional limitation obviously reduces the generalizability of our findings. However it is realistic to expect that the challenges to disease-specific knowledge observed in our study are widely prevalent in patients with AF. Second, a large proportion of our cohort had a graduate level degree, which may also limit the generalizability of our study. It is all the more relevant that we identified poor knowledge related to AF even in those with higher education. Third, we relied on individual report for determination of household income and educational attainment, which may introduce recall error or unmeasured bias. Fourth, we did not account for individual-level factors that may influence individuals’ knowledge of AF, such as specific providers, provider specialty, duration of care for AF, or history of AF treatment. Fifth, we cannot exclude the many sources of residual confounding that influence how patients understand a chronic condition such as AF.

In conclusion, we observed significant and fundamental gaps in knowledge about AF in individuals actively receiving care for this condition. Our results were somewhat modified by education but not by income. We further identified that individuals in this cohort with prevalent AF markedly overestimated their annual risk of stroke. Our results demonstrate challenges to health literacy and specifically numeracy in AF. We would assert that patients who are not able to define a chronic disease accurately have limited ability to participate in shared decision making and patient-centered aspects relevant to a complex and chronic condition such as AF. Further study must now address how to advance patient-facing health knowledge in AF. Such interventions have the potential to improve patient engagement, shared decision making, and clinical outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Individuals with atrial fibrillation had limited disease-specific knowledge.

Most participants overestimated their risk of stroke from 15 to 50%.

Deficits in patient knowledge were attenuated slightly by education but not income.

Patients require enhanced AF knowledge to participate in shared decision making.

Acknowledgments

Grant support:

This work was supported by NIH/NHLBI award number R61HL144669.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

All authors take responsibility for all aspects of the reliability and freedom from bias of the data presented and their discussed interpretation.

Conflicts of interest:

The authors report no conflicts of interest including consultancies, shareholdings, or funding agencies or grants.

References

- 1.Reiffel JA. Atrial fibrillation and stroke: Epidemiology. Am J Med. 2014;127:e15–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.January CT, Wann LS {Citation}, Calkins H, Chen LY, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC Jr, Ellinor PT, Ezekowitz MD, Field ME, Furie KL, Heidenreich PA, Murray KT, Shea JB, Tracy CM, Yancy CW. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, Calkins H, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC Jr, Conti JB, Ellinor PT, Ezekowitz MD, Field ME, u KT, Sacco RL, Stevenson WG, Tchou PJ, Tracy CM, Yancy CW, Members AATF. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130:e199–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aliot E, Breithardt G, Brugada J, Camm J, Lip GY, Vardas PE, Wagner M. An international survey of physician and patient understanding, perception, and attitudes to atrial fibrillation and its contribution to cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality. Europace. 2010;12:626–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fang MC, Panguluri P, Machtinger EL, Schillinger D. Language, literacy, and characterization of stroke among patients taking warfarin for stroke prevention: Implications for health communication. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75:403–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reading SR, Go AS, Fang MC, Singer DE, Liu IA, Black MH, Udaltsova N, Reynolds K. Health literacy and awareness of atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desteghe L, Engelhard L, Raymaekers Z, Kluts K, Vijgen J, Dilling-Boer D, Koopman P, Schurmans J, Dendale P, Heidbuchel H. Knowledge gaps in patients with atrial fibrillation revealed by a new validated knowledge questionnaire. Int J Cardiol. 2016;223:906–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lane DA, Meyerhoff J, Rohner U, Lip GYH. Atrial fibrillation patient preferences for oral anticoagulation and stroke knowledge: Results of a Conjoint analysis. Clin Cardiol. 2018;41:855–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hernandez Madrid A, Potpara TS, Dagres N, Chen J, Larsen TB, Estner H, Todd D, Bongiorni MG, Sciaraffia E, Proclemer A, Cheggour S, Amara W, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C. Differences in attitude, education, and knowledge about oral anticoagulation therapy among patients with atrial fibrillation in Europe: Result of a self-assessment patient survey conducted by the European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace. 2016;18:463–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aronis KN, Edgar B, Lin W, Martins MAP, Paasche-Orlow MK, Magnani JW. Health literacy and atrial fibrillation: Relevance and future directions for patient-centred care. Eur Cardiol. 2017;12:52–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Peel J, Baker DW. Health literacy and knowledge of chronic disease. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51:267–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oramasionwu CU, Bailey SC, Duffey KE, Shilliday BB, Brown LC, Denslow SA, Michalets EL. The association of health literacy with time in therapeutic range for patients on warfarin therapy. J Health Commun. 2014;19 Suppl 2:19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rolls CA, Obamiro KO, Chalmers L, Bereznicki LRE. The relationship between knowledge, health literacy, and adherence among patients taking oral anticoagulants for stroke thromboprophylaxis in atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Ther. 2017;35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guhl E, Althouse A, Sharbaugh M, Pusateri AM, Paasche-Orlow M, Magnani JW. Association of income and health-related quality of life in atrial fibrillation. Open Heart. 2019;6:e000974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lip GY, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJ. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: The Euro Heart Survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137:263–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hendriks JML, Crijns HJGM, Tieleman RG, Vrijhoef HJM. The atrial fibrillation knowledge scale: Development, validation and results. Int J Card. 2013;168:1422–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.OECD Skills Studies. Time for the U.S. to reskill?: What the survey of adult skills says. DOI: 10.1787/9789264204904-en. Accessed on April 27, 2019. [DOI]

- 18.Magnani JW, Mujahid MS, Aronow HD, Cene CW, Dickson VV, Havranek E, Morgenstern LB, Paasche-Orlow MK, Pollak A, Willey JZ. Health literacy and cardiovascular disease: Fundamental relevance to primary and secondary prevention: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm : A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seaburg L, Hess EP, Coylewright M, Ting HH, McLeod CJ, Montori VM. Shared decision making in atrial fibrillation: Where we are and where we should be going. Circulation. 2014;129:704–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tuckett DA, Boulton M, Olson C. A new approach to the measurement of patients’ understanding of what they are told in medical consultations. J Health Soc Behav. 1985;26:27–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making--pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:780–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.