Abstract

Lineage tracking delivers essential quantitative insight into dynamic, probabilistic cellular processes, such as somatic tumor evolution and differentiation. Methods for high diversity lineage quantitation rely on sequencing a population of DNA barcodes. However, manipulation of specific individual lineages is not possible with this approach. To address this challenge, we developed a functionalized lineage tracing tool, Control of Lineages by Barcode Enabled Recombinant Transcription (COLBERT), that enables high diversity lineage tracing and lineage-specific manipulation of gene expression. This modular platform utilizes expressed barcode gRNAs to both track cell lineages and direct lineage-specific gene expression.

Keywords: lineage tracing, heterogeneity, barcode, clonal dynamics, population variation

Graphical Abstract

Many pathological and physiological processes, including cancer, infection, and microbiota control, are governed by the evolutionary dynamics of large heterogeneous cell populations. Tumors consist of 107 to 1012 cells that vary with respect to growth rate, drug response, and cell fate decisions. While rare mutations are a driving force for population adaptation, new evidence also emphasizes the contribution of epigenetic plasticity and heterogeneous cell states within clonal populations. Intratumor cell heterogeneity is a significant clinical challenge that contributes to chemoresistance, meta-stasis and treatment failure.1–8 To improve therapeutic strategies in cancer and infectious diseases, new tools are required to measure and control the contributions of diverse cell subpopulations.9–13

Recent studies have demonstrated the utility of high-diversity DNA barcode libraries in monitoring heterogeneous cell populations.8,9,11–23 This is achieved by stably integrating cells with a unique, random DNA sequence, instantiating cell lineages that pass this heritable tag to their progeny. Lineage abundance is tracked over time by next-generation sequencing of the barcode ensemble. Changes in clonal dynamics after perturbations, such as treatment with a pharmacological agent, may reveal variation in lineage survival or proliferation rate.12–15 This approach allows for the simultaneous observation of many cell lineage trajectories to reveal high-resolution details of population dynamics. Recent functionalized lineage tracing tools have been developed to further characterize biological processes with lineage resolution. Particularly exciting methods have leveraged serially edited barcodes to enable the reconstruction of lineages and descendent sublineages to monitor developmental processes in vivo.17,22,23 Additional variations have utilized an expressed evolving barcode to allow for lineage-resolved single-cell RNA-sequencing, a powerful approach for integrating developmental origins and cell-type classification.20,21,24,25 These lineage based analyses by sequencing is a destructive measurement that limits further molecular and functional analysis of the cells in specific lineages of interest. We are not aware of any existing method that enables one to simultaneously track high diversity lineage dynamics and isolate a specific lineage from a cell population for downstream analysis. Here we set out to develop a platform technology, Control of Lineages by Barcode Enabled Recombinant Transcription (COLBERT), to enable lineage tracing followed by lineage-specific activation of gene expression.

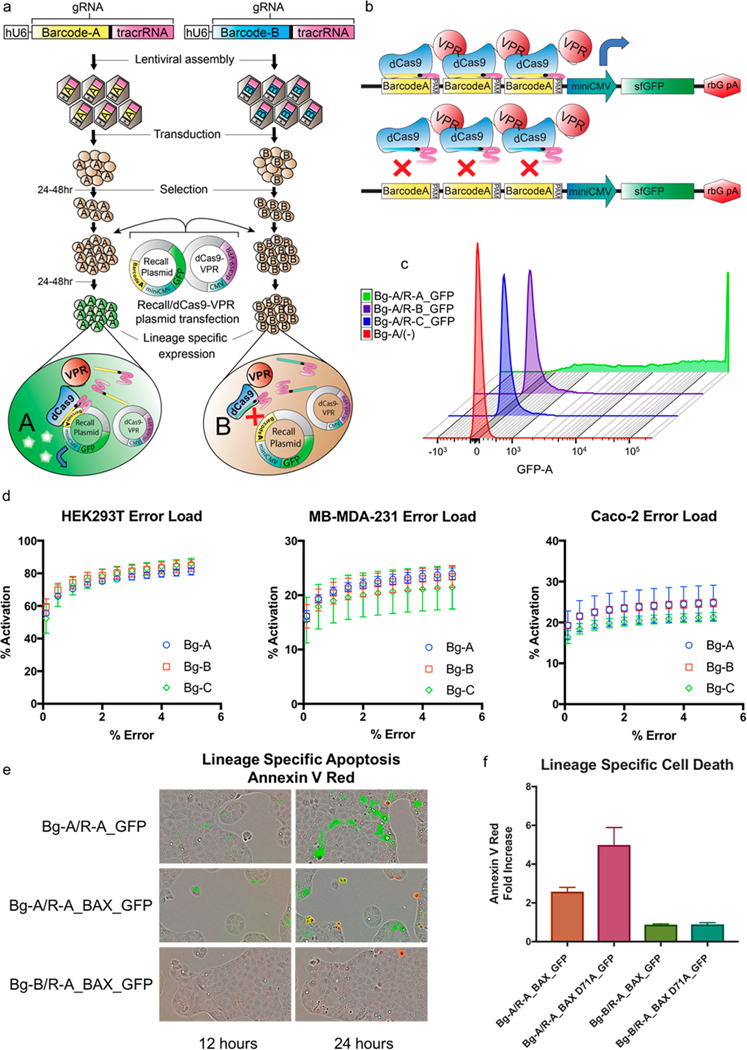

In this technique a population of cells is tagged with a stably integrated barcode-gRNA under control of a constitutive promoter. Lineage-specific gene expression can then be accomplished by transfecting the entire population of cells with a plasmid containing a transcriptional activator variant of Cas9, dCas9-VPR, and a “Recall” plasmid encoding the lineage barcode of interest upstream of a gene to be activated.18 Only those cells containing the specified barcode-gRNA of interest, in coordination with dCas9-VPR, drive expression of the reporter gene. A schematic of the overall strategy of COLBERT is shown in Figure 1a.

Figure 1.

Lineage-specific activation of gene expression. (a) Generation and lineage specific gene activation of independent barcoded gRNA populations. Three unique barcodes were randomly generated following the GNSNWNSNWNSNWNSNWNSN template and assembled into lentiviral gRNA expression cassettes. Cell lines: HEK293T, Caco2, and MDA-MB-231 were independently transduced with the three different barcode gRNAs and selected for stable integration. The barcoded populations were then cotransfected with each of one of the Recall plasmids, R-A/B/C_GFP and the dCas9-VPR plasmid. GFP expression was assessed 48 h post transfection via flow cytometry. (b) View of the lineage specific expression components. The lineage-specific Recall Plasmid contains a 3× barcode of interest_PAM array and adjacent downstream miniCMV promoter_sfGFP. In the presence of the matching barcode gRNA/dCas9-VPR complex, binding of the barcode arrays by the transcriptional activator dCas9-VPR will drive expression of sfGFP. In the case of mismatching barcode gRNA/dCas9-VPR complex, binding of the barcode arrays will not occur and expression of sfGFP will not be driven. (c) staggered histograms comparing high GFP expression for instances of matching barcode gRNA/Recall plasmid and nominal expression for instances of mismatch. GFP expression was measured via flow cytometry. (d) Error load graphs showing percent positive population activation at a given error rate. (e) Time-lapse fluorescent imaging of Caco2 Bg-A and Bg-B populations transfected with Recall-A_GFP and Recall-A_BAX_GFP along with the red apoptotic marker, Annexin-V red. The matching Bg-A population transfected with R-A_BAX_GFP displays efficient gene expression with GFP expression starting at 12 h followed BAX induced apoptosis present at 24 h. The mismatched Bg-B population does not show either GFP expression or notable induction of apoptosis. (f) Quantification of the number of Annexin-V Red positive cells show that, relative to Bg-A/R-A_GFP, there is a significant fold increase apoptosis in the cell populations transfected with a matching Recall plasmid containing either BAX or the hyper active mutant BAX D71A. Additionally, neither population with a mismatching Recall plasmid containing BAX or the hyperactive mutant displayed an increase in apoptosis over the control.

RESULTS

To demonstrate lineage-specific expression of a fluorescent reporter by COLBERT, we generated three independent HEK293T cell populations, each expressing a single known barcode gRNA (Bg), Bg-A, Bg-B, Bg-C. Cells were transduced at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1 to minimize instances of integration of more than one barcode. Cells containing stably integrated barcode sequences were selected by BFP+ expression (Figure 1a). We then constructed three different Recall plasmids (Recall A–C) each containing one of the three corresponding barcode regions and PAM site upstream of a miniCMV promoter and sfGFP (Figure 1b). Each barcoded cell population was cotransfected with each of the Recall plasmids in combination with dCas9-VPR plasmid. (Figure 1a). GFP expression was assessed via flow cytometry. Barcoded cell populations transfected with a matching Recall plasmid activated expression of the fluorescent reporter, while only nominal expression was present in the instances of mismatch (Figure 1c). This robust and easy-to-use platform can be deployed in a variety of cell types. Given this method requires manipulation of a cell system of interest, tractability and optimization should be determined for barcode transduction and recall component delivery. To assess the efficiency of lineage-specific GFP activation in the match population compared with nonspecific activation of mismatch population in HEK293T, Caco2, and MB-MDA-231 cells we quantified this signal-to-noise as error load, a measurement of percent lineage-specific activation given increasing amounts of off target activation (Supporting Figure S4). 75% of the lineage- specific GFP+ cells could be identified in HEK293T with 2% false positive activation. Error rates also remained low in Caco2, and MB-MDA-231 cells, although GFP activation was significantly lower, predominantly due to less efficient plasmid transfection in these cell types (Figure 1d). Additionally, discrepancies in transfection efficiency and lineage specific gene activation could be due to the efficiencies of the dCas9-activator of choice in the specific cell type.26

To optimize lineage-specific activation with the Recall plasmid, alternative designs were tested with varying numbers of barcode recognition sites (1×, 3× and 6×). In addition, both Recall and dCas9 VPR plasmid were titrated to determine optimal amounts for activation of barcode-driven expression (Supporting Figure S1–S3). We found that the Recall plasmid with 3× barcode recognition sites worked most efficiently with a Recall plasmid:dCas9-VPR molar ratio of 3:1.

Beyond the control of fluorescent reporter gene expression, this system can be functionalized to express any set of genes in a lineage-specific manner. To explore the multifunctionality of this platform we sought to perturb the cell fates of specific lineages, by driving lineage-specific expression of the pro-apoptotic protein BAX and the hyperactive mutant BAX D71A, in conjunction with GFP.27 Time-lapse fluorescent imaging revealed lineage-specific gene expression of GFP and subsequent apoptosis of GFP+ cells (Figure 1e). Costaining with Annexin V Red confirmed activation of apoptotic signaling in populations transfected with a matching Recall plasmid sequence, with the highest levels of apoptosis in the hyperactive BAX D71A mutant, and no activation with the mismatch Recall plasmid sequence (Figure 1f).

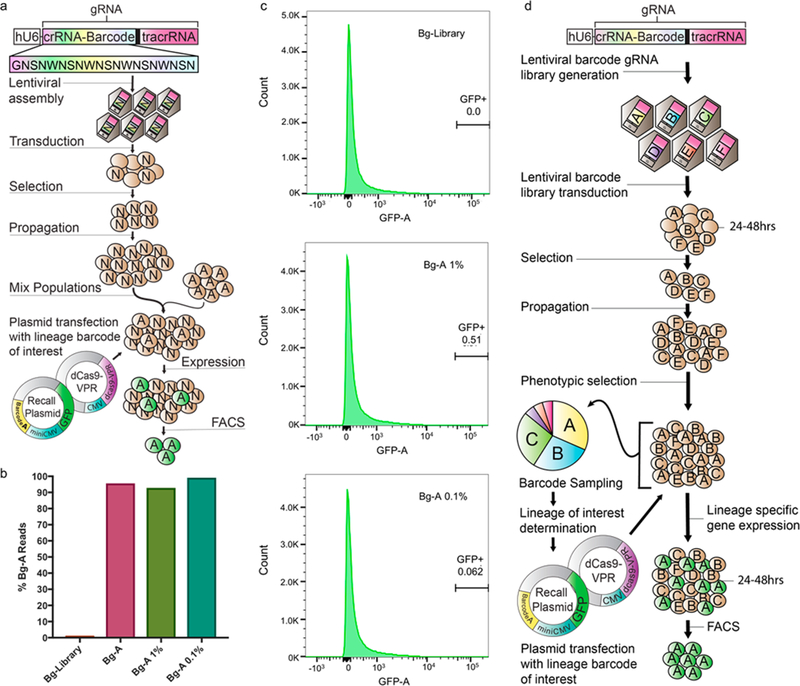

To confirm the efficiency of lineage-specific expression in a highly heterogeneous background, we tested the tool in a large diverse barcoded population. We constructed a high-diversity barcode gRNA library with the template: GNSNWNSNWNSNWNSNWNSN, having a diversity potential greater than 500 000 000 unique sequences (Figure 2a). This gRNA library was ligated into a gRNA expression lentiviral transfer vector and assembled into a pooled gRNA barcoded lentivirus. Following transduction of HEK293T, approximately 1.2 million stably integrated BFP+ cells were collected. High diversity of the barcoded lentiviral pool and HEK293T population was confirmed via barcode sampling (Supporting Figure S6–S7). Cells from the Bg-A population were then spiked into the high diversity Bg-Library population at 1:100 and 1:1000 dilution and grown overnight (Figure 2a). The spiked populations were then cotransfected with the Recall-A_GFP and dCas9-VPR plasmids and sorted via FACS for GFP expression. A Bg-Library only population was cotransfected as a control to initialize sorting gates for 0% error-load. Cell capture rates were in agreement with the 0% error-load determinations for HEK293T; activated GFP+ cells represented 0.51% and 0.062% of cells captured from the Bg-A 1% and Bg-A 0.1% populations, respectively (Figure 2b). Sorted GFP+ cells were subcultured and genomic DNA was isolated for sequencing. Barcode sequences were amplified via PCR using primers containing both flanking barcode annealing regions and Illumina adaptor/index sequences and quantified by next-generation sequencing (Supporting Figure S8). Barcode sequencing of the isolated Bg-A populations confirms that COLBERT identified and isolated highly purified fractions of cells carrying the reference Bg-A barcode, from within the high diversity Bg-Library population. 92.8% and 99.1% of the reads were identified as Bg-A from the high diversity populations spiked with 1% and 0.1% Bg-A respectively. This is very comparable to the 95.8% Bg-A reads (rom the Bg-A only control population. (Figure 2c). The demonstration that expressed gRNA barcodes can be used to efficiently perform lineage-specific manipulation of gene expression opens up the possibility for a broad range of studies, enabling lineage-specific interrogation within the context of a heterogeneous, evolving cell population (Figure 2d). Following barcode instantiation, cells can be monitored and at intervals the genomically encoded barcode region may be sequenced for quantitation of clonal barcodes; parallel samples can be archived for retroactive analysis. Lineage dynamics may inform the identification of specific lineages of interest for subsequent gene activation in archival samples via introduction of cognate Recall vectors into these populations. As in all molecular barcoding approaches, the diversity of the cell library should be small compared to the overall lentiviral diversity to minimize the likelihood of barcoding with the same or highly similar sequences.28 These statistical considerations have been well described elsewhere.15,28,29 As this method relies on lentiviral integration of the barcoded constructs into the genome, biological effects of this process should be assessed in lineages of interest. As well, stable expression should be evaluated via BFP expression as silencing of the integrated construct could occur over time. The ability to track clonal fitness dynamics and perform lineage-specific molecular analysis in longitudinal, parallel studies will provide unprecedented insight into cancer adaptation and other diseases with an evolutionary basis.

Figure 2.

Isolation of a single lineage of interest within a high diversity population. (a) High diversity barcoded-gRNA HEK293T cell population was generated with a GNSNWNSNWNSNWNSNWNSN template. The HEK293T Bg-A population was spiked in with the high diversity Bg-Library population to obtain a 1% and 0.1% Bg-A mixed population. Bg-A cells were then isolated from the mixed population via cotransfection of the R-A_GFP plasmid and dCas9-VPR plasmid and cell sorted based off of GFP expression. (b) To initialize sorting gates and determine capture rate, the Bg-Library, Bg-A 1% and Bg-A 0.1% populations were transfected with the Recall components and flow analyzed. Sorting gates were set based off of the Bg-Library to have a 0% error-load, resulting in the capture of 0.51% and 0.062% of cells in the Bg-A 1% and Bg-A 0.1%, respectively. (c) Barcode sequencing of the Bg-library and Bg-A populations as well as the Bg-A 1% and 0.1% isolated populations. Barcode sequencing of the isolated Bg-A 1% and 0.1% population show 92.8% and 99.1% of the reads being Bg-A respectively, nearly identical to the 95.8% Bg-A reads from the sampled Bg-A population. (d) Example experimental workflow utilizing COLBERT. A population of cells are tagged with a library of expressed barcoded gRNAs. The barcoded population can subsequently go through a phenotypic selection of interest. The resulting selected population is then sampled for relative barcode abundance. The barcode analysis would inform lineages of interest and allow for lineage-specific Recall plasmids to be assembled and cotransfected with dCas9-VPR into the resultant population for lineage-specific gene expression. In this instance, GFP is expressed, allowing the lineage of interest to be cell sorted and isolated from the mixed population.

METHODS

High-Complexity Barcode-gRNA Library Construction.

The following 60 base pair oligonucleotide containing a 19 nucleotide semirandom sequence corresponding the barcode guide-RNA and reverse extension primer was ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies: GAGCCTGAAGACCTCACCGNSNWNSNWNSNWNSNWNSNGTTTTAGCGTCTTCCATGCGCA, TGCGCATGGAAGACGCTAAAAC. An extension reaction was performed to generate the double stranded barcode-gRNA oligo. The double stranded product contains two BbsI sites that, after digestion, generate complementary overhangs for ligation into the gRNA expression transfer vector pKLV-U6gRNA(Bbsl)-PGKpuro2ABFP (Addgene). 1 μg of Bbsl digested gRNA expression transfer vector was ligated with digested barcode-gRNA insert in a molar ratio 1:7. This reaction was purified and concentrated in 6 μL using the Zymo DNA Clean & Concentrator kit and transformed into electrocompetent SURE 2 cells (Agilent). Transformants were inoculated into 500 mL of 2xYT containing 100 μg/mL carbenicillin for outgrowth overnight at 37 °C. Transformation efficiency was calculated via dilution plating and shown to be approximately 7 × 108 cfu/μg.

Mock Barcode-gRNA Construction.

Three different discrete known barcode-gRNA lentiviral expression vectors were generated with the gRNA sequences: (Bg-A) GACATGGATCGCTAGAACCG, (Bg-B) GTCAAGGTAGCTAAGTAGCG, (Bg-C) GTCAAGCGTGCAATGGTAGC. To accomplish this, the following oligo pairs with complementary barcode sequences and the appropriate overhang sequences were mixed and cloned into the BbsI digested pKLV-U6gRNA(Bbsl)-PGKpuro2ABFP transfer vector at a 10:1 molar ratio:

-

(A)

CACCGACATGGATCGCTAGAACCGGT,TAAAACCGGTTCTAGCGATCCATGTC.

-

(B)

CACCGTCAAGGTAGCTAAGTAGCGGT,TAAAACCGCTACTTAGCTACCTTGAC.

-

(c)

CACCGTCAAGCGTGCAATGGTAGCGT,TAAAACGCTACCATTGCACGCTTGAC.

Lentiviral Assembly.

Lentiviral assembly was accomplished using the GeneCopeia Lenti-Pac HIV Expression Packaging Kit (cat# HPK-LvTR-20). Two days prior to lentiviral transfection HEK293T cells were plated onto a 10 cm dish at 1.5 million cells and cultured in 10 mL DMEM supplemented with 10% heat inactivated FBS. 48 h after plating, cells were 70–80% confluent and transfected with 15 μL of EndoFectin and a mix of 2.5 μg of pKLV-U6Barcode-gRNA-PGKpuro2ABFP and 2.5 μg of Lenti-Pac HIV mix (GeneCopoeia). The media was replaced 14 h post transfection with 10 mL DMEM supplemented with 5% heat inactivated FBS and 20 μL TiterBoost (GeneCopoeia) reagent. Media containing viral particles was collected at 48 and 72 h post transfection, centrifuged at 500g for 5 min, and filtered through a 45 μm poly(ether sulfone) (PES) low protein-binding filter. Filtered supernatant was stored at –80 °C in aliquots for later use.

Barcoding Cell Lines.

Cell lines HEK293T, MB-MDA-231, and Caco-2 cell lines were cultured in DMEM + GlutaMAX supplemented with 4.5 g/L D-glucose, 110 mg/L sodium pyruvate, 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Cells were transduced with the pKLV-U6Barcode-gRNA-PGKpuro2ABFP lentivirus using 1 μg/mL Polybrene. After 48 h incubation, BFP+ cells were isolated by FACS. To reduce the likelihood that two viral particles enter a single cell, the lentiviral transduction multiplicity of infection was kept below 0.1.

Barcode Amplification.

After lineage isolation, cell populations of interest were harvested and genomic DNA was extracted using the PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit (Thermo Fisher). Barcode sequences were amplified using PCR and sent for SE 75bp sequencing on an Illumina MiniSeq Primer sequences contained both flanking barcode annealing regions and Illumina adaptor/index sequence (Supporting Figure S8). For PCR reactions, 50 ng of plasmid DNA was used for the pKLV-U6Barcode-gRNA-PGKpuro2ABFP, 250 ng of genomic DNA was used for the BgA-100%, BgA-1%, and BgA-0.1% samples, and 16 μg of genomic DNA for the HEK 293T BgL.

Barcode Sequencing Analysis.

Functional gRNA units were identified with a custom Python script and gRNA sequences grouped using the ustacks program provided as part of the stacks package.30 Custom scripts may be found at http://github.com/brocklab/COLBERT_amplicon_seq. Functional gRNAs were defined as containing perfect matches to the 34bp 5′ flanking sequence, a 20 bp spacer (corresponding to the expected 20 bp barcode sequence length), and a perfect match to the remaining 3′ flanking region. All frequencies reported are the frequency of the gRNA compared to the number of functional gRNA identified rather than the total number of reads. The ustacks program was run with the following allowances: gRNA detected a single time were considered, gRNA were grouped together if they differed by a single base pair (allowing for a sequencing error rate of ~5%), and both haplotype calling and secondary reads were disabled.

Recall Plasmid Assembly.

The Recall plasmid was constructed by using standard restriction cloning to combine a gBlock containing three tandem type IIS restriction sites (BsmBI, BbsI, BsaI) flanked by terminators with an amplicon containing a bacterial replication origin and ampicillin resistance marker to create this Golden Gate ready vector. Genes and barcode-specific landing pad sequences were cloned into the recall plasmid using the type IIS restriction sites. Barcode-specific landing pad arrays were generated by ordering phosphorylated complementary oligo pairs, corresponding with the barcode sequence of interest, with specific overlaps that both direct assembly of the landing pad array and integration into the Recall plasmid (Supporting Figure S1). The landing pad arrays were ligated and purified by gel extraction to ensure cloning with a fully assembled array. The fully assembled barcode landing pad was cloned into the BbsI site using standard restriction digest cloning. Mock Recall screens were used to assess efficiency via lineage specific expression of sfGFP. This reporter construct was assembled by cloning in a gBlock encoding miniCMV-sfGFP into the BsaI site using Golden Gate Assembly (Recall_GFP). Lineage-specific cell death was measured via barcode driven expression BAX and the hyper active mutant BAX D71A. gBlocks encoding miniCMV-BAX and miniCMV-BAX D71A were cloned into the BsmBI sites using Golden Gate Assembly (Recall_BAX_GFP, Recall_BAX D71A_GFP).

Mock Recall Screens.

The mock screens were performed in 24 well plates. HEK293T cells were transfected at 60% confluence using 1.5 μL Lipofectamine3000, 1 μL P3000 Reagent, 150 ng of Recall_GFP plasmid and 500 ng of dCas9-VPR plasmid. Caco2 cells were transfected at 30% confluence and transfected using 1 μL LipofectamineLTX, 0.5 μL Plus Reagent, 250 ng Recall_GFP Plasmid, and 250 ng dCas9-VPR plasmid. MB-MDA-231 cells were transfected at 70% confluence using 1 μL LipofectamineLTX, 0.5 μL Plus Reagent, 250 ng Recall_GFP Plasmid, and 250 ng dCas9-VPR plasmid. Cells were analyzed for GFP expression via flow cytometry 48 h post-transfection. Error load was quantified by comparatively tallying the values of the GFP-histogram, from high to low GFP intensity, of matching and mismatching recall samples. Specifically, sum totals of matching recall events were tabulated with respect to and along with each new accruing mismatch recall event. From these tabulations, % activation at a given error was calculated using the formula

The calculated % activation and % error values were plotted on a scatter plot and least-squares fitting generated exponential equations to model the data. (Supporting Figure S4). Experiments were performed in biological triplicate and modeled error load values were averaged along with standard error calculated.

Lineage Isolation.

For a standard, a range of HEK293T Bg-A/Bg-library dilutions were plated in 35 mm tissue culture dishes (100% Bg-A, 50% Bg-A, 10% Bg-A, 1% Bg-A, 0.1% Bg-A) with total cell number 360 000 per well. Two 10 cm plates were plated at 2.2 million cells for both a 1% and 0.1% Bg-A lineage dilution for lineage isolation. The 35 mm dishes were transfected with 4.5 μL LipofectamineLTX, 2.25 μL Plus Reagent, 675 ng Recall Plasmid, and 1.575 μg dCas9-VPR plasmid per well. The 10 cm plates were transfected with 27.5 μL LipofectamineLTX, 13.75 μL Plus Reagent, 4.125 μg Recall Plasmid, and 9.625 μg dCas9-VPR plasmid per plate. Populations were flow analyzed and sorting gates were set using 0% Bg-A as a standard (Supporting Figure S5). The GFP+ population was cultured for isolation of genomic DNA as above.

Annexin V Red Assay.

Caco2 were transfected at 30% confluence using 1 μL LipofectamineLTX, 0.5 μL Plus Reagent, 250 ng Recall Plasmid, and 250 ng dCas9-VPR plasmid. At time of transfection, 2.5 μL IncuCyte Annexin V Red Reagent (Essen BioScience Cat # 4641) was added to monitor apoptosis. Cells were monitored in the IncuCyte for real time measurement of apoptotic cells in culture via fluorescent quantitation. Images were collected every 2 h and quantitation of apoptotic cells was performed using the IncuCyte image analysis software, measuring red object counts.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R21CA212928 to AB) and a Texas 4000 Foundation Cancer Research Pilot Grant (to AB). The authors are grateful to Amy Price for excellent administrative support and the staff of the Genome Sequencing and Analysis Facility at The University of Texas at Austin for technical support and assistance.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acssyn-bio.8b00105.

Further experimental details regarding barcode landing pad array design, lineage specific activation optimization, error load quantification, barcode library characterization, amplification primers, and lineage specific apoptosis movies (PDF)

Movie S1 (AVI)

Movie S2 (AVI)

Movie S3 (AVI)

Movie S4 (AVI)

Movie S5 (AVI)

Movie S6 (AVI)

Movie S7 (AVI)

Movie S8 (AVI)

Movie S9 (AVI)

Movie S10 (AVI)

Movie S11 (AVI)

Movie S12 (AVI)

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Brock A, Chang H, and Huang S (2009) Non-Genetic Heterogeneity-a Mutation-Independent Driving Force for the Somatic Evolution of Tumours. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10 (5), 336–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Sharma SV, Lee DY, Li B, Quinlan MP, Takahashi F, Maheswaran S, McDermott U, Azizian N, Zou L, and Fischbach MA (2010) A Chromatin-Mediated Reversible Drug-Tolerant State in Cancer Cell Subpopulations. Cell 141 (1), 69–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Polyak K (2014) Tumor Heterogeneity Confounds and Illuminates: A Case for Darwinian Tumor Evolution. Nat. Med. 20 (4), 344–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Archetti M, Ferraro DA, and Christofori G (2015) Heterogeneity for IGF-II Production Maintained by Public Goods Dynamics in Neuroendocrine Pancreatic Cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112 (6), 1833–1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Cleary AS, Leonard TL, Gestl SA, and Gunther EJ (2014) Tumour Cell Heterogeneity Maintained by Cooperating Subclones in Wnt-Driven Mammary Cancers. Nature 508 (7494), 113–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Quintana E, Shackleton M, Foster HR, Fullen DR, Sabel MS, Johnson TM, and Morrison SJ (2010) Phenotypic Heterogeneity among Tumorigenic Melanoma Cells from Patients That Is Reversible and Not Hierarchically Organized. Cancer Cell 18 (5), 510–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Pisco AO, Brock A, Zhou J, Moor A, Mojtahedi M, Jackson D, and Huang S (2013) Non-Darwinian Dynamics in Therapy-Induced Cancer Drug Resistance. Nat. Commun. 4, 2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Lee J, Lee J, Farquhar KS, Yun J, Frankenberger CA, Bevilacqua E, Yeung K, Kim E-J, Balazsi G, and Rosner MR (2014) Network of Mutually Repressive Metastasis Regulators Can. Promote Cell Heterogeneity and Metastatic Transitions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S. A. 111 (3), E364–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Frieda KL, Linton JM, Hormoz S, Choi J, Chow K-HK, Singer ZS, Budde MW, Elowitz MB, and Cai L (2017) Synthetic Recording and in Situ Readout of Lineage Information in Single Cells. Nature 541 (7635), 107–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Woodworth MB, Girskis KM, and Walsh CA (2017) Building a Lineage from Single Cells: Genetic Techniques for Cell Lineage Tracking. Nat. Rev. Genet. 18 (4), 230–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Rogers ZN, McFarland CD, Winters IP, Naranjo S, Chuang C-H, Petrov D, and Winslow MM (2017) A Quantitative and Multiplexed Approach to Uncover the Fitness Landscape of Tumor Suppression in Vivo. Nat. Methods 14 (7), 737–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Yu C, Mannan AM, Yvone GM, Ross KN, Zhang Y-L, Marton MA, Taylor BR, Crenshaw A, Gould JZ, Tamayo P, et al. (2016) High-Throughput Identification of Genotype-Specific Cancer Vulnerabilities in Mixtures of Barcoded Tumor Cell Lines. Nat. Biotechnol. 34 (4), 419–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Bhang HC, Ruddy DA, Krishnamurthy Radhakrishna V, Caushi JX, Zhao R, Hims MM, Singh AP, Kao I, Rakiec D, Shaw P, et al. (2015) Studying Clonal Dynamics in Response to Cancer Therapy Using High-Complexity Barcoding. Nat. Med. 21 (5), 440–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Hata AN, Niederst MJ, Archibald HL, Gomez-Caraballo M, Siddiqui FM, Mulvey HE, Maruvka YE, Ji F, Bhang HC, Krishnamurthy Radhakrishna V, et al. (2016) Tumor Cells Can Follow Distinct Evolutionary Paths to Become Resistant to Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibition. Nat. Med. 22 (3), 262–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Levy SF, Blundell JR, Venkataram S, Petrov DA, Fisher DS, and Sherlock G (2015) Quantitative Evolutionary Dynamics Using High-Resolution Lineage Tracking. Nature 519 (7542), 181–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Blundell JR, and Levy SF (2014) Beyond Genome Sequencing: Lineage Tracking with Barcodes to Study the Dynamics of Evolution, Infection, and Cancer. Genomics 104, 417–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Kalhor R, Mali P, and Church GM (2017) Rapidly Evolving Homing CRISPR Barcodes. Nat. Methods 14 (2), 195–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Chavez A, Scheiman J, Vora S, Pruitt BW, Tuttle M, P R Iyer E, Lin S, Kiani S, Guzman CD, Wiegand DJ, et al. (2015) Highly Efficient Cas9-Mediated Transcriptional Programming. Nat. Methods 12 (4), 326–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Stubbington MJT, Lonnberg T, Proserpio V, Clare S, Speak AO, Dougan G, and Teichmann SA (2016) T Cell Fate and Clonality Inference from Single-Cell Transcriptomes. Nat. Methods 13 (4), 329–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Raj B, Wagner DE, McKenna A, Pandey S, Klein AM, Shendure J, Gagnon JA, and Schier AF (2018) Simultaneous Single-Cell Profiling of Lineages and Cell Types in the Vertebrate Brain. Nat. Biotechnol. 36 (5), 442–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Spanjaard B, Hu B, Mitic N, Olivares-Chauvet P, Janjuha S, Ninov N, and Junker JP (2018) Simultaneous Lineage Tracing and Cell-Type Identification Using CRISPR-Cas9-Induced Genetic Scars. Nat. Biotechnol. 36 (5), 469–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Pei W, Feyerabend TB, Rossler J, Wang X, Postrach D, Busch K, Rode I, Klapproth K, Dietlein N, Quedenau C, et al. (2017) Polylox Barcoding Reveals Haematopoietic Stem Cell Fates Realized in Vivo. Nature 548 (7668), 456–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).McKenna A, Findlay GM, Gagnon JA, Horwitz MS, Schier AF, and Shendure J (2016) Whole-Organism Lineage Tracing by Combinatorial and Cumulative Genome Editing. Science 353 (6298), aaf7907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Wagner DE, Weinreb C, Collins ZM, Briggs JA, Megason SG, and Klein AM (2018) Single-Cell Mapping of Gene Expression Landscapes and Lineage in the Zebrafish Embryo. Science 360 (6392), 981–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Alemany A, Florescu M, Baron CS, Peterson-Maduro J, and van Oudenaarden A (2018) Whole-Organism Clone Tracing Using Single-Cell Sequencing. Nature 556 (7699), 108–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Chavez A, Tuttle M, Pruitt BW, Ewen-Campen B, Chari R, Ter-Ovanesyan D, Haque SJ, Cecchi RJ, Kowal EJK, Buchthal J, et al. (2016) Comparison of Cas9 Activators in Multiple Species. Nat. Methods 13 (7), 563–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Zhou H, Hou Q, Hansen JL, and Hsu Y-T (2007) Complete Activation of Bax by a Single Site Mutation. Oncogene 26 (50), 7092–7102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Kebschull JM, Garcia da Silva P, Reid AP, Peikon ID, Albeanu DF, and Zador AM (2016) High-Throughput Mapping of Single-Neuron Projections by Sequencing of Barcoded RNA. Neuron 91 (5), 975–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Casbon JA, Osborne RJ, Brenner S, and Lichtenstein CP (2011) A Method for Counting PCR Template Molecules with Application to Next-Generation Sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 39 (12), e81–e81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Catchen J, Hohenlohe PA, Bassham S, Amores A, and Cresko WA (2013) Stacks: An Analysis Tool Set for Population Genomics. Mol. Ecol 22 (11), 3124–3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.