Abstract

Background:

Experiences of childhood adversity are consistently associated with compromised behavioral health later in life. Less clear is the intergenerational influence of maternal childhood adversity on developmental outcome in children. Completely unknown are the mechanisms linking teen mother’s childhood adversity to child developmental outcomes.

Objective:

The present study tested whether aspects of parenting (parenting stress, physical discipline, and disagreement with grandparents) served as the pathways between teen mother’s childhood adversity and the externalizing behaviors of their offspring at age 11, by gender.

Participants and Setting:

Data were from a longitudinal panel study of teen mothers and their children, the Young Women and Child Development Study (N=495; 57% male).

Methods:

The pathways from teen mother’s childhood adversity to their offspring’s externalizing behavior were tested by two subscales: rule-breaking behavior and aggressive behavior. In addition, multiple-group analysis was examined for potential gender differences.

Results:

Teen mother’s childhood adversity was positively associated with greater use of parenting stress (β=0.16, p<.01) and physical discipline (β=0.11, p<.05). In addition, parenting stress, physical discipline, and disagreement with grandparent were all associated with increased rule-breaking and aggressive behaviors in children. Multiple group analysis revealed that the path between physical discipline and externalizing behavior differed by gender, with the path only significant for girls.

Conclusions:

These findings have implications for early intervention efforts that emphasize the need to intervene with children and parents, particularly helping teen mothers gain knowledge and skills to offset the impact of their experiences of childhood adversity on their parenting behaviors.

Keywords: Teen mother, Childhood Adversity, Parenting behaviors, Externalizing Behavior

Experiences of adversity in childhood have significant long-term effects on developmental outcomes. Childhood adversities can threaten early and lifelong development and health (Anda et al., 2002; Björkenstam et al., 2013; Lanier, Maguire-Jack, Lombardi, Frey, & Rose, 2018). Childhood adversities include a variety of traumas, including abuse and neglect, living in poverty, living with a substance abuser, or living with someone who is/has been imprisoned (Felitti et al., 1998). While few prior studies have established the link between parental child abuse histories and later developmental outcomes (Madigan, Wade, Plamondon, & Jenkins, 2015; Pasalich, Cyr, Zheng, McMahon, & Spieker, 2016), the intergenerational impacts are unknown.

Teen parenting has significant health-related consequences for both mothers and children. Teen mothers have described the experience of labor as traumatizing (Anderson & McGuinness, 2008) and are at higher risk for psychological distress that continues over time (Mollborn & Morningstar, 2009). Compared to pregnant adults, adolescent motherhood is associated with a range of adverse outcomes, including depression (Kamalak et al., 2016), substance use (Salas-Wright, Vaughn, Ugalde, & Todic, 2015) and posttraumatic stress disorder (Madigan, Vaillancourt, McKibbon, & Benoit, 2015), which can negatively influence parent-child relationships. Further, teen mothers exhibiting their own vulnerabilities to their children can perpetuate multigenerational cycles of disadvantage (Coyne & D’Onofrio, 2012; Lee et al., 2017). Children of teen mothers are at increased risk for behavioral health problems (Huang, Costeines, Ayala, & Kaufman, 2014) and compromised development (Lee et al., 2017). Specifically, being born to adolescent mothers may place children at increased risk for externalizing behavior problems (Garner, Shonkoff, Siegel, Dobbins, Earls, McGuinn, & Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care, 2012). The present study examines the relationship between teen mother’s childhood adversity (child abuse and family dysfunction) on the externalizing behaviors of their children. Specifically, we examine three aspects of parenting as possible pathways from early adversity of mothers to externalizing behaviors in their children: (1) disagreement with grandparents on parenting, (2) physical discipline, and (3) parenting stress. In addition, we explored externalizing behaviors into two ways, rule-breaking behavior and aggressive behavior; this will allow the investigation of different developmental patterns for different manifestations of externalizing behavior.

Teen Mothers with Childhood Adversity: An understudied intergenerational risk source

Childhood adversities place children at greater risk for a wide range of developmental issues later in life (Björkenstam et al., 2013). Further, there is a graded relationship found between childhood adversity and poorer health and behavioral outcomes (Anda et al., 2002; Lanier et al., 2018). These processes may perpetrate the cycle of negative experiences, placing teens at higher risk for negative outcomes.

Many teen mothers are exposed to multiple traumatic and stressful events during childhood that can affect their psychological functioning and quality of life both before and after the birth of their child (Beers & Hollo, 2009). Importantly, teen mothers’ history of childhood adversities can influence their child’s development. In fact, teen mothers with a history of sexual and physical abuse were more likely to have an infant with insecure attachment, which predicted higher externalizing problems in preschool and in early adolescence (Pasalich et al., 2016). In a longitudinal study of adolescent mothers and their children, an association between teen mother’s child abuse history and their offspring externalizing behavior was identified (Pasalich et al., 2016). No identified study, however, has linked teen mother’s own childhood adversity experiences with externalizing behaviors in their children.

Parenting: the most proximal risk process that links teen mother’s childhood adversity to their child development

Parenting is a primary force behind the transfer of any intergenerational risk (Serbin & Karp, 2004). Young mothers may be at higher risk for parenting adjustment issues because they are developmentally unprepared for the challenge of motherhood and forced to mature before they are truly ready (Savio Beers & Hollo, 2009; Serbin & Karp, 2004). Teen mothers face a number of challenges, including transitioning into a new role with increased responsibilities. Well documented in prior studies, premature entry into the role of mother has a range of correlates, including poor parenting behaviors, less interaction with their child, and less positive in their parenting style (Beers & Hollo, 2009; Lee & Guterman, 2010; Wilson, Gross, Hodgkinson, & Deater-Deckard, 2017). This may be partly due to their young age and lower cognitive readiness for parenting (Beers & Hollo, 2009). Some studies demonstrated that experiences of childhood adversity can impinge on parenting, because of their links to higher rates of depression (Chapman et al., 2004), risk of illicit drug use (Dube et al., 2003), and overall poor emotion regulation (Smith, Cross, Winkler, Jovanovic, & Bradley, 2014). In fact, it is important to consider how teen moms’ experience of childhood adversity may affect their parenting, and the development of their young children. When caregivers are faced with parenting in the context of their own trauma, it can be considerably more difficult to co-regulate their young children and provide the sensitive and nurturing care that children need. Experiences of childhood maltreatment often impact a mother’s view of being a caregiver, in that they are at greater risk for developing unhelpful attitudes and beliefs about parenting compared to moms who were not maltreated as children (Wright, Fopma-Loy, & Oberle, 2012). Taken together, teen parents, who may already be at higher risk for problematic parenting behaviors, may experience even more struggle with parenting, perceive parenting to be more stressful, and rely on harsh parenting strategies due to distress associated with their own exposure to childhood adversity.

Teen mothers’ parenting stress.

Maternal exposure of childhood adversities is significantly associated with parental stress (Ammerman et al., 2013; Murphy et al., 2014). Parenting stress (e.g., stress in the parenting role) is a common indicator of maternal distress, which in turn has a significant impact on child development (Baker et al., 2003; Neece, Green, & Baker, 2012). Especially among adolescent mothers, high levels of parenting stress are problematic, having a direct influence on parenting-child interaction (Lehr et al., 2016) and child developmental outcomes (Crnic, Gaze, & Hoffman, 2005). Given long established links between parenting stress and negative child outcomes, identifying significant correlates between teen mom’s childhood adversities and parenting stress could promote early identification of parents and children at risk.

Teen mother’s physical discipline.

Parents’ use of physical discipline is related to children’s externalizing behaviors (Boutwell, Franklin, Barnes, & Beaver, 2011; Evans, Simons, & Simons, 2012; Ferguson, 2013; Gershoff, 2002), even controlling for demographic, parenting, and individual characteristics of the child (Fine, Trentacosta, Izard, Mostow, & Campbell, 2004; Lansford et al., 2014; MacKenzie, Nicklas, Waldfogel, & Brooks-Gunn, 2012). Specifically, mothers exposed to physical abuse were more likely to report spanking their children and using corporal punishment as a primary parenting strategy (Chung et al., 2009). Especially given that adolescent mothers are at higher risk for utilizing harsh parenting behaviors (Lee & Guterman, 2010), it is necessary to examine the impact of teen mother’s physical discipline on their offspring’s externalizing behaviors.

Disagreement on parenting with grandparents: A unique parenting aspects in teen mothers.

Teen mothers heavily rely on their own mothers for advice; the mothers of teen mothers have been found to provide both social support and significant parenting support in the first 24 months of the child’s life (Oberlander, Shebl, Magder, & Black, 2009). Further, residing with the maternal grandmother has been found to improve teen mothers’ adjustment to parenting (Oberlander et al., 2009). This is due, in part, to the fact that grandparents continue to parent the teen parent as well as their grandchildren, assisting in transitioning adolescent parents into the parenting role (Dallas, 2004). In fact, teen mothers who are parenting their children with the support of their mothers are more confident in their parenting abilities (Oberlander, Black, & Starr, 2007). Further, teen mothers who have an open, communicative, and flexible relationship with their own mothers tend to exhibit more positive parenting behaviors (Wakschlag, Chase-Lansdale, & Brooks-Gunn, 1996).

On the other hand, conflicted relationships between a teen mother and her mother can lead to parenting stress, decreased parenting satisfaction, and increased depressive symptoms for the teen mother (Bunting & McAuley, 2004). In addition, less supportive grandmother-teen mother relationships may result in the teen mother leaving her mother’s home, ultimately leading to decreased social support, fewer opportunities for modeling for parenting behavior, and less educational support. This may negatively impact both the teen mother and her child (Oberlander et al., 2009). Since support from grandmothers is a direct resource for adolescent mothers and their offspring, it is important to understand how disagreement with grandparents about parenting may inform the quality of parenting that children of teen mothers receive.

Gender Differences

While many studies have examined gender differences in children’s externalizing behaviors (Archer, 2004; Loeber, Capaldi, & Costello, 2013), the knowledge base on gender differences in relation to teen mother’s parenting behaviors is limited. Researchers consistently suggests gender differences in adult mother’s parenting behaviors (specifically harsh parenting) and child externalizing behaviors (Mandara, Murray, Telesford, Varner, & Richman, 2012), with boys exhibiting more externalizing behaviors than girls throughout both childhood and adolescence (Bongers, Koot, van der Ende, & Verhulst, 2004). However, the impact of teen mothers’ parenting influences on boys’ and girls’ externalizing behaviors are not fully explained. This association for teen mothers who have experienced child adversities are unknown. Building on the current knowledge base, our study will generate pathways for boys and girls of teen mothers with childhood adversities to child externalizing behaviors.

Current Study

While there are studies linking teen mother’s childhood adversity and their own long-term developmental outcomes (Ardelt & Eccles, 2001; Brody, Murry, Kim, & Brown, 2002; Nievar & Luster, 2006), less is known about the intergenerational impact of teen mother’s childhood adversity on their parenting behaviors, and in turn, their child’s externalizing behaviors in early adolescence. One existing study examining the impact of teen mothers’ childhood adversities on behavior problems of their offspring only incorporated childhood abuse history (Pasalich et al., 2016), missing the opportunity to understand the influences of adversities outside of maltreatment. Further, research on grandparent’s involvement in the parenting of their grandchild would help us better understand the ways in which we can support multi-generational family systems to increase positive outcomes of children of teen mothers.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess family dynamics in the context of teen mother’s childhood adversity and parenting. In the present study, we hypothesize that teen mother’s childhood adversity will be associated with their own parenting behaviors. In addition, we expect that parenting stress, physical discipline, and disagreement with grandparents will be positively associated with their offspring’s externalizing behaviors at age 11. Further, we hypothesize that there will be gender differences in the relationship between parenting behaviors and child externalizing behaviors.

Methods

Study Design and Sample

The current study is a secondary analysis of data from the Young Women and Child Development Study (YCDS), a longitudinal panel study involving two cohorts of teen mothers and their offspring (Lee et al., 2017; Oxford, Lee, & Lohr, 2010). Recruitment for this two-cohort panel study occurred in health and social services agencies in three counties of a metropolitan region in Washington State. Eligible participants were pregnant, unmarried adolescents aged 17 years or younger who were planning to carry their baby to term at the time of enrollment. Data collection for Cohort 1 (C1) began in 1987 and concluded in 2007; data collection for Cohort 2 (C2) began in 1992 and terminated in 2007. A total of 495 pregnant adolescents (N=240 in C1; N=255 in C2) were enrolled in the study. Sample retention rates were consistently high across study years, averaging 94.6% for Cohort 1 and 83.7% for Cohort 2. The current study used the data of teen mothers and their offspring from both Cohort 1 and Cohort 2. Of the 495 participants, 488 (98.6%) remained in the final analysis. Sample attrition was based on response to the outcome variable of interest. The final analytic sample was racially diverse (58.2% Caucasian, 25.8% African American, and 16.1% mixed or other racial groups). Female offspring were slightly underrepresented (43.0%). While the two cohorts had many similarities, they differed in racial composition and educational attainment; as such, we controlled for teen mother’s race and education in all analyses. The study was approved by the Human Subjects Review Committee at the affiliated university.

Measures

Teen mother’s childhood adversity.

Teen mother’s childhood adversity was informed by the Adverse Childhood Experience study (Anda et al., 2002). Within the existing dataset, 8-items mapped onto the original 10 ACEs. Childhood adversity before age 18 was measured using the following items: Exposure to: (1) physical abuse (did a parents ever throw something at you, pushed, grabbed, shoved, or slapped you?), (2) sexual abuse (Have you ever been forced to have sexual intercourse against your will?), (3) family closeness (Our family members do not feel close to each other), (4) poverty (public assistance; Have you received public assistance/welfare or agency), (5) food insecurity (How often have you worried about having enough food for yourself?), (6) parent alcohol use (Did you ever live with an alcoholic parent or parent figure?), (7) maternal arrest before 18 years old (Were your parents arrested?), and (8) parental divorce (Were your parents divorced?) (Table 1). Each childhood adversity exposure was coded as “1” (yes) vs. “0” (no). The total ACE score was calculated with sum of the positive items of exposure, which ranged from 0 to 8.

Table 1.

Childhood Adversity Constructs and Measures (YCDS Cohort 1 & Cohort 2)

| Constructs | Original ACE Questions | Study Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Physical abuse | Did a parent or other adult in the household often or very often: Push, grab, slap, or throw something at you? or ever hit you so hard that you had marks or were injured? | Did parents/guardians ever: Actually throw something at you, or push, grab, shove or slap you (0 vs. 1)? |

| Sexual abuse | Did an adult or person at least 5 years older than you ever: Touch or fondle you or have you touch their body in a sexual way? or attempt or actually have oral, anal, or vaginal intercourse with you? | Have you ever been forced to have sexual intercourse against your will? That is, you had no other choice and had to do it (0 vs. 1)? |

| Family Closeness | Did a parent or other adult in the household often or very often: Swear at you, insult you, put you down, or humiliate you? or act in a way that made you afraid that you might be physically hurt? | Our family members feel very close to each other (0 vs. 1). Our family members are supportive of each other during difficult times (0 vs. 1). My parents don’ like me very much (0 vs. 1). |

| Poverty | Primary financial source | Have you received public assistance (welfare or shelter/agency) (0 vs. 1)? |

| Food insecurity | Did you often or very often feel that: You didn’t have enough to eat, had to wear dirty clothes, and had no one to protect you? or your parents were too drunk or high to take care of you or take you to the doctor if you needed it? | How often have you worried about having enough food for yourself (0 vs. 1)? |

| Parent alcohol abuse | Did you live with anyone who was a problem drinker or alcoholic, or who used street drugs? | Did you ever live with an alcoholic parent or parent figure (0 vs. 1)? |

| Parent incarceration | Did a household member go to prison? | Life Events Checklista (0 vs. 1) Have any of the following things happened to you: Parent was arrested (0 vs. 1)? |

| Divorce | Were your parents ever separated or divorced? | Life Events Checklista (0 vs. 1) Have any of the following things happened to you: Parents divorced (0 vs. 1)? |

Coddington, 1972

Parental stress at child age 3.

The 36-item PSI (Abidin, 1995) was used to collect self-report data of parenting stress. The three subscales each included 12 items. Parents used a 5-point scale to indicate the degree to which they agreed with each statement (1=strongly disagree; 2=disagree, 3=not sure, 4=agree, 5=strongly agree). This study utilized the sum of the total responses across 36 items (Cronbach’s α=.93).

Physical discipline at child age 6.

Use of physical discipline was measured using 13-items from the Conflict Tactics Scale, a validated measure to assess punitive discipline, spanking, and physical aggression (Strassberg, Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1994; Straus, 1979). Teen mothers rated the frequency with which they engaged in various parenting behaviors during the past 6 months on a 7-point scale, ranging from 0 to 6 (0=never, 1=less than once a month, 2=once a month, 3=2–3 times a month, 4=once a week, 5=2–5 times a week, 6=everyday). In this study, items from the CTS were summed to calculate a total score for conflict tactics (α=.73).

Disagreement with “grandparents” on parenting styles at child age 3.

Disagreement with “grandparents” was measured with a single-item: “Parent criticizing how you take care of your child”. Teen mothers reported its frequency in the past 6 months on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 to 5 (1=never, 2=seldom, 3=sometimes, 4=fairly often, 5=very often). In this study, teen mothers were asked to identify a person who was a “caregiver”. This person was not required to have a biological relationship to the mother or child (i.e. maternal or paternal mother, foster mothers, other guardian, or another person serving like a “mother” to the teen mother). For this work, this individual was identified as the “grandmother” as they were identified as providing support to the child as a grandmother would.

While prior studies have documented the link between parenting stress and more negative and less positive parenting behaviors towards their children, such as physical discipline and criticism, (Anthony et al., 2005), the purpose of current study is to examine how different aspects of parenting impact child behavioral outcomes, among a sample of teen mothers with childhood adversities. Therefore, the study grouped three different types of parenting aspects in the same paths, presupposing that the parenting behaviors might compete against each other, but that one could have a stronger impact on the child’s externalizing behaviors over the others. In addition, because of the high likely that grandparent’s disagreement on parenting and teen mother’s parenting stress would be correlated, the study chose to include parenting stress at the same time point as disagreement with grandparent on parenting. Based on literature showing that parenting norms maintain rank-order stability and vary little over time (Okado & Haskett, 2015), we believe using harsh discipline style at age 6 (when the items were asked of the mothers) is relevant and useful for understanding externalizing behaviors of the children of teen mothers.

Child externalizing behavior at age 11.

Children’s externalizing behaviors were measured using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach, 1991), a 118-item parent report measure designed to assess competencies, adaptive function, and problems for children ages 4–18 (Kerker et al., 2015). Items on externalizing behaviors were scored on a 3-point Likert scale (0=not true, 1=somewhat or sometimes true, and 2= very true or often true), summed to calculate raw scores for the total externalizing behavior. In addition to CBCL total score, rule-breaking behavior and aggressive behavior were also scored on a 3-point Likert scale, summed to calculate raw scores. Cronbach’s alpha for CBCL total score, rule-breaking behavior, and aggressive behavior were α=.93, .59, and .88, respectively.

Covariates.

Covariates included teen mother’s age (continuous), race (White, African American, Native American, Asian/Pacific Islander, Other), baseline educational attainment (<HS=0 vs. HS=1), teen mother’s baseline depressive symptoms (CES-D, SCL-90; Cronbach’s α= .78), child’s sex (male=0 vs. female=1), and child’s externalizing behavior at age 6 (CBCL).

Analytic approach

The analysis strategy was completed in three parts. First, the study tested pathways from teen mother’s childhood adversity to their offspring’s externalizing behavior in the full sample. Second, offspring externalizing behavior was tested by subscale – rule-breaking behavior and aggressive behavior. Third, a multiple-group analysis evaluated potential gender differences in the hypothesized pathways. All covariates were included in each model. The gender difference across the two models was tested using a Wald-test in Mplus version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). For all the models, multiple fit indexes were used, including comparative fit index (CFI) ≥.95 (Hu & Bentler, 1999), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤.06 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). All the analyses were conducted in Mplus version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). Missing data were managed with full information likelihood estimation, a recommended way to address missingness (Schlomer, Bauman, & Card, 2010).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 reports descriptive statistics for analysis variables. More than half of teen mothers had child adversity scores over 3 (72.8%). More than 25% of teen mothers reported disagreement with grandparents (sometimes, fairly often, very often). The mean scores for physical discipline was 17.01 (SD=8.12, range 1–43) and for parenting stress was 75.92 (SD=20.74, range 36–165). Bivariate correlation tests of study variables revealed that teen mother’s childhood adversity was positively correlated with physical discipline (r2=0.14, p<.01), parenting stress (r2=0.19, p<.01), and children’s externalizing behavior (r2=0.13, p<.01). All three aspects of parenting were positively correlated with children’s externalizing behaviors (p<.01).

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of Analysis Variables (N=495)

| n (%) or M (SD) | Range | Skewness/Kurtosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child sex (N=481) | ||||

| Male | 274 (57.0) | |||

| Female | 207 (43.0) | |||

| Education (N=495) | ||||

| < High school | 124 (25.1) | |||

| High school (9~12th) | 371 (74.9) | |||

| Race/ethnicity (N=481) | ||||

| White | 280 (58.2) | |||

| African American | 124 (25.8) | |||

| Native American | 32 (6.7) | |||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 21 (4.4) | |||

| Others | 24 (5.0) | |||

| Baseline depression (N=495) | 10.79 (5.67) | 0~27 | ||

| Baseline externalizing behavior (N=395) | Externalizing behavior | 13.48 (8.71) | 0~53 | |

| Rule-breaking | 2.38 (2.07) | 0~14 | ||

| Aggression | 11.09 (7.11) | 0~40 | ||

| Childhood adversitya (N=495) | ||||

| 0 | 8 (1.6) | |||

| 1 | 53 (10.7) | |||

| 2 | 74 (14.9) | |||

| 3 | 131 (26.5) | |||

| 4 | 107 (21.6) | |||

| 5 | 78 (15.8) | |||

| 6 | 37 (7.5) | |||

| 7 | 4 (0.8) | |||

| 8 | 3 (0.6) | |||

| Primary care providerb (N=396) | ||||

| Mother | 89 (22.5) | |||

| Grandmother | 10 (2.5) | |||

| Other relatives | 28 (7.1) | |||

| Boyfriend/husband’s mother | 16 (4.0) | |||

| Others | 253 (63.9) | |||

| Disagreement with grandparentsc (N=422) | ||||

| Never | 213 (50.5) | |||

| Seldom | 96 (22.7) | |||

| Sometimes | 74 (17.5) | |||

| Fairly Often | 23 (5.5) | |||

| Very Often | 16 (3.8) | |||

| Physical disciplined (N=344) | 17.01 (8.12) | 1~43 | ||

| Parenting stresse (N=418) | 75.92 (20.74) | 36~165 | ||

| Externalizing behaviorf (N=327) | Externalizing behavior | 11.70 (9.17) | 0~47 | 1.17/1.35 |

| Rule-breaking | 2.52 (2.52) | 0~16 | 1.69/4.60 | |

| Aggression | 9.18 (7.25) | 0~34 | 1.07/0.84 |

Assessed retrospectively

Others indicate other relative, friend, father of baby/boyfriend/husband, day care, and paid baby sitter

Parent criticizes your parenting

Conflict Tactics total score

Parenting Stress Index (PSI) total score

Externalizing Behavior (CBCL) total score, subscales

Evaluation of the Pathways

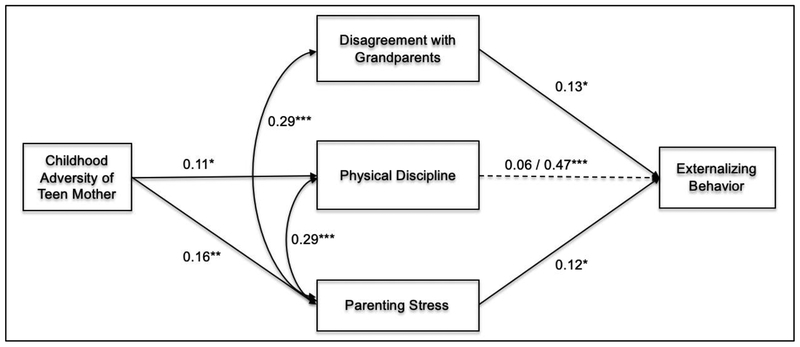

The final models are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2 (N=488). The first model (Figure 1) examined children’s total externalizing behavior. The model fit was good (X2 (8) = 8.80, p=0.35, RMSEA=0.01, CFI=0.99), and it accounted for 29.2% of the variance in children’s externalizing behavior. Having a higher childhood adversity score was positively associated with use of physical discipline (β=0.11, p<.05) and parenting stress (β=0.16, p<.01). In addition, disagreement with grandparents (β=0.13, p<.05), use of physical discipline (β=0.36, p<.01), and parenting stress (β=0.12, p<.05) each predicted increased externalizing behaviors in children.

Figure 1.

Path model of association of teen mom’s childhood adversity and parenting behaviors on children’s externalizing behavior

Covariates: sex, race, mother’s age, mother’s education, mother’s depression, baseline externalizing behavior (age 6)

Note.

a. Solid lines represent statistically significant at p-value *p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001 for full analysis sample (standardized coefficients).

b. Dotted lines represent statistically significant gender differences (boy/girl).

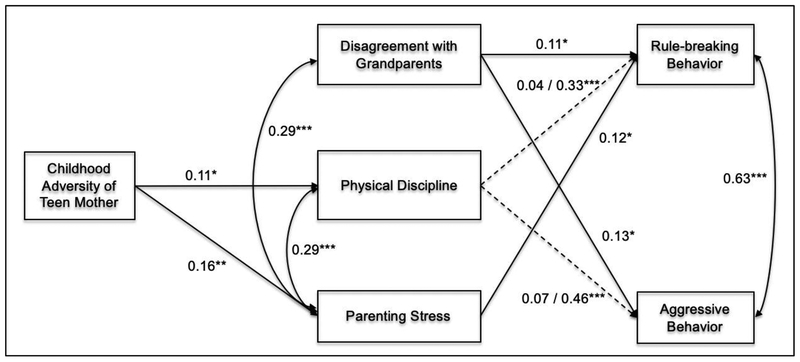

Figure 2.

Path model of association of teen mom’s childhood adversity and parenting behaviors on children’s rule-breaking and aggressive behavior

Covariates: sex, race, mother’s age, mother’s education, mother’s depression, baseline externalizing behavior (age 6)

Note.

a. Solid lines represent statistically significant at p-value *p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001 for full analysis sample (standardized coefficients).

b. Dotted lines represent statistically significant gender differences (boy/girl).

The second model (Figure 2) evaluated the same hypothesized pathways outlined in Figure 1, but with two sub-scales: (1) rule-breaking behavior and (2) aggressive behavior. The model fit was good (X2 (11) = 9.77, p=0.55, RMSEA=0.00, CFI=1.00), and it accounted for 25.4% of the variance in children’s rule-breaking and 26.7% for aggressive behavior. Similar to the first model, disagreement with grandparents (β=0.11, p<.05), physical discipline (β=0.26, p<.05), and parenting stress (β=0.12, p<.05) were associated with increased child’s rule-breaking behavior. While disagreement with grandparents (β=0.13, p<.05) and physical discipline (β=0.37, p<.01) were predictive of aggressive behavior in the full sample, there was no association between parenting stress and child’s aggressive behaviors.

Gender differences

Subsequent multiple-group analysis tested possible gender differences in the hypothesized paths. As shown in Figure 1, a multiple-group analysis revealed that there were gender differences in the direct path from physical discipline to externalizing behavior (Wald-test χ2(1)=7.89, p<.001). The path from physical discipline to child externalizing behavior for girls was statistically significant (β=0.47, p<.001), whereas the same path was not significant for boys. Second (see Figure 2), a multiple-group analysis revealed that there were gender differences in the direct path from physical discipline to rule-breaking behavior (Wald-test χ2(1)=3.88, p<.05) and aggressive behavior (Wald-test χ2(1)=7.25, p<.001). Again, the path to rule-breaking (β=0.33, p<.01) and aggressive behavior (β=0.46, p<.001) was statistically significant for girls, but not for boys.

Discussion

Being born to teen mothers may place children at increased risk for poorer development and increased behavioral challenges, including externalizing behavior problems (Lee et al., 2017; Shonkoff et al., 2012). There has been little investigation of the extent to which teen mother’s own vulnerabilities (i.e. childhood adversities) are associated with their offspring’s externalizing behaviors. Our study findings provided evidence of the multigenerational influence of parental childhood adversity. This study adds to the existing literature based in several important ways. First, our results provide evidence for intergenerational risk by examining the path from maternal childhood adversity to children’s externalizing behaviors through aspects of parenting. Second, our study modeled the predictor and outcome at different time points. Teen mother’s own experience of child adversity predicting offspring’s externalizing behavior at age 11 captured the importance of intervening with children and their mothers, particularly among mothers who have experienced their own trauma. Third, our study looked at two sub-scales of externalizing behavior: rule-breaking behavior and aggressive behavior. This enabled us to examine these relationships with two different developmental patterns with more specificity. Last, we examined the gender differences for all the possible paths. The findings suggest that because family crisis evolves over time, it is critical to assess and provide parenting support, particularly among families dealing with a pile-up of stressors and strains (like childhood maltreatment and family dysfunction). In this case, family’s adaptive resources can be part of the family’s capabilities for meeting demands and needs.

Maternal childhood adversity to three parenting aspects

Results from the full-group analysis support the mechanisms underlying the risk of teen mother’s childhood adversity experiences and their own parenting behaviors. Childhood adversities of teen mothers predicted mothers’ increased use of physical discipline and elevated parenting stress. Extending previous studies reporting intergenerational impacts of maternal trauma on child development (Putnam-Hornstein, Cederbaum, King, Eastman, & Trickett, 2015; Widom, Czaja, & DuMont, 2015), our study findings suggested that compromised parenting behaviors serve as pathways underlying these intergenerational impacts. Principally, children tend to imitate the model provided by their caregivers’ behavior. Exposure to aggressive parenting from an early age is likely to elicit a hostile attributions in children (Hyde, Shaw, & Moilanen, 2010). Therefore, it is probable that children who grow up in an environment where caregivers use aggressive forms of discipline, are likely to learn through modeling to be more aggressive themselves (Gámez-Guadix, Straus, & Hershberger, 2011). In addition to the physical discipline, there was an association between teen mother’s childhood adversity and parenting stress. This is consistent with prior work with adult mothers (Ammerman et al., 2013; Steele et al., 2016). In our results, we confirmed that this also applies for teen mothers. Contrary to our conceptual model, childhood adversities did not explain the path towards disagreement with ‘grandparents’ on parenting. The non-significant association between childhood adversity and disagreement is likely attributable to our sample; while many of the identified “grandparents” were the primary caregivers, 63.9% were other identified important adult or primary caregivers who may or may not have been a biological mother. It may be that those individuals did not have early life involvement with their identified “mother” and therefore, the adversity experiences of the teen mothers were not a shared experience with the ‘grandparent’ of the child.

Three parenting aspects to child’s externalizing behaviors

Associations between teen mothers’ parenting behaviors and their offspring’s externalizing behavior were found. In line with previous studies (Boutwell et al., 2011; Evans et al., 2012), teen mothers’ physical discipline predicted children’s externalizing behavior at age 11. This is not surprising given that child behavior problems develop first within the context of family interactions. Recent studies using nationally representative samples report that higher frequency of physical discipline is positively related to negative child outcomes (Gromoske & Maguire-Jack, 2012), specifically elevated externalizing behaviors (Ferguson, 2013; Gershoff, 2002), even after controlling for child’s age, gender, family income and race (Lorber, O’Leary, & Slep, 2011). In addition, our finding suggests that parenting stress plays a significant role in determining the externalizing behaviors of youth. Similar to findings with adult mothers (Baker et al., 2003; Neece et al., 2012) and their children, elevated levels of parenting stress for teen mothers may directly contribute to child behavior problems. Although there were no associations between teen mother’s childhood adversities and disagreement with ‘grandparents’ on parenting, there was a significant path between disagreement with grandparents and child externalizing behavior at age 11. We did not have the statistical power to look at differences by caregiver type, but this is an important factor to explore in future studies, as shared adversities between a grandparent and teen mother could create support challenges. Since teen mothers rely heavily on an extended network of support for parenting, experiencing an unhealthy relationship with their ‘grandparents’ may lead to compromised developmental outcomes in children (Wilson et al., 2017).

Gender differences

Last, in regards to the multiple group analysis, gender differences were found in the path between physical discipline and externalizing behavior and both of its subscales; rule-breaking and aggressive behavior. Although boys and girls seem to display different patterns of behavior problems during childhood and adolescence (Crick & Zahn-Waxler, 2003), reliable gender differences in rates of problem behaviors start to emerge after the preschool period (Sterba, Prinstein, & Cox, 2007). Patterns of parent-child relationships during early childhood accounts for later gender differences in externalizing behaviors, and our results proved those associations of early use of physical discipline on externalizing behavior at age 11. Our findings that only girls were at significantly higher risk for developing externalizing behaviors differ from prior studies, which consistently show that boys are more likely to exhibit externalizing behaviors than girls (Evans et al., 2012). Children tend to model same sex parents’ behaviors (Barnett & Scaramella, 2013), which might explain our unexpected study findings—girls may have been modeling their teen mother’s behavior. In addition, studies indicated that boys experience significantly more physical discipline than girls (Arnstein, 2009), potentially leaving girls to be more vulnerable to experiences of physical discipline from parents.

Limitations.

Our study findings should be understood in the context of methodological limitations. First, the measure of child externalizing behaviors was based on parental reports, which may introduce systematic biases in estimates of associations among variable. Yet, our study controlled for child’s externalizing behaviors at age 6, which mitigates this concern to some extent. Still, future research should assess child externalizing behaviors from the children’s own perspective. Second, the reliability of rule-breaking behavior can be problematic, which indicates that approximately half of the variance in the observed score may be attributable to truth. However, since the CBCL items exhibit strong face validity and construct validity, our study confirmed that these items do tap into an underlying construct of rule-breaking behaviors among children of teen mothers. Third, we were unable to explore differences in “grandparent” support by biological vs. non-biological grandparents. Future research is needed to better understand the ways in which intrafamilial dynamics creates intergenerational cycles of risk. Fourth, our study did not incorporate other forms of support that may have been received by teen mothers, including support from father of the child or peers. Since father’s support can be a potent source of social support and a significant contributor to their child’s behavioral outcomes, future studies need to pay attention to father-mother relationships and support in the transition to parenthood. Fifth, all the measures on teen mother’s childhood adversities relied on teen mother’s self-reports, creating the possibility of reporting errors or biases. Sixth, due to our focus on teen mother’s childhood adversity before age of 18 (while still adolescents), our study did not control for the child’s age at mother’s 18th birthday (however, this variable was stable -Mage=3.5, SD=0.1). To better understand the influence of intergenerational toxic stress on children’s behaviors, future work should account for mother’s childhood adversities, as well as the childhood adversity experiences of their children.

Conclusion

The study’s findings shed light on underlying parenting mechanisms linking teen mother’s childhood adversity to their offspring’s externalizing behavior problems and suggests that children of teen mothers with prior exposure to adversities (such as maltreatment, poverty, parent’s divorce, parent’s substance abuse) are at increased risk for poor behavioral outcomes. Our results suggest that reducing risk for hostile parenting may be important for preventing externalizing problems in these vulnerable families. Promoting support for teen mothers with a childhood adversity history may help reduce further risk in the succeeding generation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our gratitude to YCDS study participants for their continued contribution to the study. This study was supported by the grant 1R03HD097379 from National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Funding: This study was supported by the grant 1R03HD097379 from National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

References

- Abidin RR (1995). Manual for the Parenting Stress Index (3rd ed.). Odessa FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach T (1991). Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL 4–18, YSR, and TRF profiles: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman RT, Shenk CE, Teeters AR, Noll JG, Putnam FW, & van Ginkel JB (2013). Multiple mediation of trauma and parenting stress in mothers in home visiting. Infant Mental Health Journal, 34, 234–241. 10.1002/icd.385 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anda RF, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Chapman D, Edwards VJ, Dube SR, & Williamson DF (2002). Adverse childhood experiences, alcoholic parents, and later risk of alcoholism and depression. Psychiatr Serv, 53(8), 1001–1009. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.8.1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C, & McGuinness TM (2008). Do teenage mothers experience childbirth as traumatic? J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv, 46(4), 21–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony L, Anthony B, Glanville D, Naiman D, Waanders C, & Shaffer S (2005). The relationships between parenting stress, parenting behavior and preschoolers’ social competence and behavior problems in the classroom. Infant and Child Development, 14, 133–154. doi: 10.1002/icd.385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Archer J (2004). Sex differences in aggression in real-world settings: A meta-analytic review. Review of General Psychology, 8, 291–322. doi:doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.8.4.291 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ardelt M, & Eccles JS (2001). Effects of mothers’ parental efficacy beliefs and promotive parenting strategies on inner-city youth. Journal of Family Issues, 22(8), 944–972. [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein E (2009). Associations between corporal punishment and behavioral adjustment in preschool-aged boys and girls. (Bachelor of Arts), University of Michigan, College of Literature, Science, and the Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Baker BL, McIntyre LL, Blacher J, Crnic K, Edelbrock C, & Low C (2003). Pre-school children with and without developmental delay: behaviour problems and parenting stress over time. J Intellect Disabil Res, 47(Pt 4–5), 217–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett MA, & Scaramella LV (2013). Mothers’ parenting and child sex differences in behavior problems among African American preschoolers. J Fam Psychol, 27(5), 773–783. doi: 10.1037/a0033792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beers LA, & Hollo RE (2009). Approaching the adolescent-headed family: a review of teen parenting. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care, 39(9), 216–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2009.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björkenstam E, Hjern A, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Vinnerljung B, Hallqvist J, & Ljung R (2013). Multi-exposure and clustering of adverse childhood experiences, socioeconomic differences and psychotropic medication in young adults. PLoS One, 8(1), e53551. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongers IL, Koot HM, van der Ende J, & Verhulst FC (2004). Developmental trajectories of externalizing behaviors in childhood and adolescence. Child Dev, 75(5), 1523–1537. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00755.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutwell BB, Franklin CA, Barnes JC, & Beaver KM (2011). Physical punishment and childhood aggression: the role of gender and gene-environment interplay. Aggress Behav, 37(6), 559–568. doi: 10.1002/ab.20409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Kim S, & Brown AC (2002). Longitudinal pathways to competence and psychological adjustment among African American children living in rural single-parent households. Child Dev, 73(5), 1505–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunting L, & McAuley C (2004). Research review: teenage pregnancy and motherhood: the contribution of support. Child Fam Soc Work, 9, 207–215. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman DP, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Edwards VJ, & Anda RF (2004). Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. J Affect Disord, 82(2), 217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung EK, Mathew L, Rothkopf AC, Elo IT, Coyne JC, & Culhane JF (2009). Parenting attitudes and infant spanking: the influence of childhood experiences. Pediatrics, 124(2), e278–286. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne CA, & D’Onofrio BM (2012). Some (but not much) progress toward understanding teenage childbearing: a review of research from the past decade. Adv Child Dev Behav, 42, 113–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, & Zahn-Waxler C (2003). The development of psychopathology in females and males: current progress and future challenges. Dev Psychopathol, 15(3), 719–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crnic KA, Gaze C, & Hoffman C (2005). Cumulative parenting stress across the preschool period: Relations to maternal parenting and child behaviour at age 5. Infant and Child Development, 14, 117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Dallas C (2004). Family matters: how mothers of adolescent parents experience adolescent pregnancy and parenting. Public Health Nurs, 21(4), 347–353. doi: 10.1111/j.0737-1209.2004.21408.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Chapman DP, Giles WH, & Anda RF (2003). Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: the adverse childhood experiences study. Pediatrics, 111(3), 564–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SZ, Simons LG, & Simons RL (2012). The effect of corporal punishment and verbal abuse on delinquency: mediating mechanisms. J Youth Adolesc, 41(8), 1095–1110. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9755-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, … Marks JS (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med, 14(4), 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CJ (2013). Spanking, corporal punishment and negative long-term outcomes: a meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Clin Psychol Rev, 33(1), 196–208. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine SE, Trentacosta CJ, Izard CE, Mostow AJ, & Campbell JL (2004). Anger perception, caregivers’ use of physical discipline, and aggression in children at risk. Social Development, 13, 213–228. [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET (2002). Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: a meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychol Bull, 128(4), 539–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gromoske A, & Maguire-Jack K (2012). Transactional and cascading relations between early spanking and children’s social-emotional development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 1054–1068. doi:doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.01013.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gámez-Guadix M, Straus M, & Hershberger S (2011). Childhood and adolescent victimization and perpetration of sexual coercion by male and female university students. Deviant Behavior, 32(8), 712–742. doi:doi: 10.1080/01639625.2010.514213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler t. P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Huang CY, Costeines J, Ayala C, & Kaufman JS (2014). Parenting Stress, Social Support, and Depression for Ethnic Minority Adolescent Mothers: Impact on Child Development. J Child Fam Stud, 23(2), 255–262. doi: 10.1007/s10826-013-9807-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde LW, Shaw DS, & Moilanen KL (2010). Developmental precursors of moral disengagement and the role of moral disengagement in the development of antisocial behavior. J Abnorm Child Psychol, 38(2), 197–209. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9358-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamalak Z, Köşüş N, Köşüş A, Hizli D, Akçal B, Kafali H, … Isaoğlu Ü (2016). Adolescent pregnancy and depression: is there an association? Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol, 43(3), 427–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerker BD, Zhang J, Nadeem E, Stein RE, Hurlburt MS, Heneghan A, … McCue Horwitz S (2015). Adverse Childhood Experiences and Mental Health, Chronic Medical Conditions, and Development in Young Children. Acad Pediatr, 15(5), 510–517. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2015.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanier P, Maguire-Jack K, Lombardi B, Frey J, & Rose RA (2018). Adverse Childhood Experiences and Child Health Outcomes: Comparing Cumulative Risk and Latent Class Approaches. Matern Child Health J, 22(3), 288–297. doi: 10.1007/s10995-017-2365-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Sharma C, Malone PS, Woodlief D, Dodge KA, Oburu P, … Di Giunta L (2014). Corporal punishment, maternal warmth, and child adjustment: a longitudinal study in eight countries. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol, 43(4), 670–685. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.893518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Gilchrist LD, Beadnell BA, Lohr MJ, Yuan C, Hartigan LA, & Morrison DM (2017). Assessing Variations in Developmental Outcomes Among Teenage Offspring of Teen Mothers: Maternal Life Course Correlates. J Res Adolesc, 27(3), 550–565. doi: 10.1111/jora.12293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, & Guterman NB (2010). Young mother-father dyads and maternal harsh parenting behavior. Child Abuse Negl, 34(11), 874–885. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JO, Gilchrist LD, Beadnell BA, Lohr MJ, Yuan C, Hartigan LA, & Morrison DM (2017). Assessing Variations in Developmental Outcomes Among Teenage Offspring of Teen Mothers: Maternal Life Course Correlates. J Res Adolesc, 27(3), 550–565. doi: 10.1111/jora.12293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Capaldi DM, & Costello E (2013). Gender and the development of aggression, disruptive behavior, and early delinquency from childhood to early adulthood. Disruptive Behavior Disorders, 1, 137–160. doi:doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-7557-6_6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorber MF, O’Leary SG, & Slep AM (2011). An initial evaluation of the role of emotion and impulsivity in explaining racial/ethnic differences in the use of corporal punishment. Dev Psychol, 47(6), 1744–1749. doi: 10.1037/a0025344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie MJ, Nicklas E, Waldfogel J, & Brooks-Gunn J (2012). Corporal punishment and child behavioral and cognitive outcomes through 5 years-of-age: Evidence from a contemporary urban birth cohort study. Infant Child Dev, 21(1), 3–33. doi: 10.1002/icd.758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan S, Vaillancourt K, McKibbon A, & Benoit D (2015). Trauma and traumatic loss in pregnant adolescents: the impact of Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavior Therapy on maternal unresolved states of mind and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Attach Hum Dev, 17(2), 175–198. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2015.1006386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan S, Wade M, Plamondon A, & Jenkins J (2015). Maternal abuse history, postpartum depression, and parenting: links with preschoolers’ internalizing problems. Infant Ment Health J, 36(2), 146–155. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandara J, Murray CB, Telesford JM, Varner FA, & Richman SB (2012). Observed gender differences in African American mother-child relationships and child behavior. Family relations, 61, 129–141. doi:doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00688.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mollborn S, & Morningstar E (2009). Investigating the relationship between teenage childbearing and psychological distress using longitudinal evidence. J Health Soc Behav, 50(3), 310–326. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy A, Steele M, Dube SR, Bate J, Bonuck K, Meissner P, … Steele H (2014). Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) questionnaire and Adult Attachment Interview (AAI): implications for parent child relationships. Child Abuse Negl, 38(2), 224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, & Muthén B (1998–2017). Mplus User’s Guide (Seventh Edition ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Neece CL, Green SA, & Baker BL (2012). Parenting stress and child behavior problems: a transactional relationship across time. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil, 117(1), 48–66. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-117.1.48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nievar MA, & Luster T (2006). Developmental processes in African American families: An application of McLoyd’s theoretical model. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(2), 320–331. [Google Scholar]

- Oberlander SE, Black MM, & Starr RH (2007). African American adolescent mothers and grandmothers: a multigenerational approach to parenting. Am J Community Psychol, 39(1–2), 37–46. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9087-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberlander SE, Shebl FM, Magder LS, & Black MM (2009). Adolescent mothers leaving multigenerational households. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol, 38(1), 62–74. doi: 10.1080/15374410802575321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okado Y, & Haskett ME (2015). Three-Year Trajectories of Parenting Behaviors Among Physically Abusive Parents and Their Link to Child Adjustment. Child & Youth Care Forum, 44(5), 613–633. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford ML, Lee JO, & Lohr MJ (2010). Predicting Markers of Adulthood among Adolescent Mothers. Soc Work Res, 34(1), 33–44. doi: 10.1093/swr/34.1.33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasalich DS, Cyr M, Zheng Y, McMahon RJ, & Spieker SJ (2016). Child abuse history in teen mothers and parent-child risk processes for offspring externalizing problems. Child Abuse Negl, 56, 89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam-Hornstein E, Cederbaum JA, King B, Eastman AL, & Trickett PK (2015). A population-level and longitudinal study of adolescent mothers and intergenerational maltreatment. Am J Epidemiol, 181(7), 496–503. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, Ugalde J, & Todic J (2015). Substance use and teen pregnancy in the United States: evidence from the NSDUH 2002–2012. Addict Behav, 45, 218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.01.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savio Beers LA, & Hollo RE (2009). Approaching the adolescent-headed family: a review of teen parenting. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care, 39(9), 216–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2009.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlomer GL, Bauman S, & Card NA (2010). Best practices for missing data management in counseling psychology. J Couns Psychol, 57(1), 1–10. doi: 10.1037/a0018082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serbin LA, & Karp J (2004). The intergenerational transfer of psychosocial risk: mediators of vulnerability and resilience. Annu Rev Psychol, 55, 333–363. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, Health C o. P. A. o. C. a. F., Committee on Early Childhood, A. o., and Dependent Care, & Pediatrics, S. o. D. a. B. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232–246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AL, Cross D, Winkler J, Jovanovic T, & Bradley B (2014). Emotional dysregulation and negative affect mediate the relationship between maternal history of child maltreatment and maternal child abuse potential. Journal of Family Violence, 29(5), 483–494. [Google Scholar]

- Steele H, Bate J, Steele M, Danskin K, Knafo H, Nikitiades A, … Murphy A (2016). Adverse Childhood Experiences, Poverty, and Parenting Stress. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 48(1), 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sterba SK, Prinstein MJ, & Cox MJ (2007). Trajectories of internalizing problems across childhood: heterogeneity, external validity, and gender differences. Dev Psychopathol, 19(2), 345–366. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strassberg Z, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, & Bates JE (1994). Spanking in the home and children’s subsequent aggression toward kindergarten peers. Development and Psychopathology, 6, 445–461. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA (1979). Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The conflict tactics (CT) scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wakschlag LS, Chase-Lansdale PL, & Brooks-Gunn J (1996). Not just “ghosts in the nursery”: contemporaneous intergenerational relationships and parenting in young African-American families. Child Dev, 67(5), 2131–2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Czaja SJ, & DuMont KA (2015). Intergenerational transmission of child abuse and neglect: real or detection bias? Science, 347(6229), 1480–1485. doi: 10.1126/science.1259917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D, Gross D, Hodgkinson S, & Deater-Deckard K (2017). Association of teen mothers’ and grandmothers’ parenting capacities with child development: A study protocol. Res Nurs Health, 40(6), 512–518. doi: 10.1002/nur.21839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright MOD, Fopma-Loy J, & Oberle K (2012). In their own words: The experience of mothering as a survivor of childhood sexual abuse. Development and psychopathology, 24(2), 537–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]