Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Engaging community urologists in referring patients to clinical trials could increase the reach of cancer trials and, ultimately, alleviate cancer disparities. We sought to identify determinants of referring patients to clinical trials among urology practices serving rural communities.

METHODS

We conducted semi-structured qualitative interviews based on the Theoretical Domains Framework at non-metropolitan urology practices located in communities offering urological cancer trials. Participants were asked to consider barriers and strategies that might support engaging their patients in discussions about urological cancer clinical trials and referring them appropriately. Recorded interviews were transcribed and coded using template analysis.

RESULTS

Most participants were not aware of available trials and had no experience with trial referral. Overall, participants held positive attitudes toward clinical trials and recognized their potential roles in accrual, but limited local resources reduced opportunities for offering trials. Most participants expressed a need for increased human, financial, and other resources to support this role. Many participants requested information and training to increase their knowledge of clinical trials and confidence in offering them to patients. Participants highlighted the need to build efficient pathways to identify available trials, match eligible patients, and facilitate communication and collaboration with cancer centers for patient follow-up and continuity of care.

CONCLUSIONS

With adequate logistical and informational support, community urology practices could play an important role in clinical trial accrual, advancing cancer research and increasing treatment options for rural cancer patients. Future studies should explore the effectiveness of strategies to optimize urology practices’ role in clinical trial accrual.

Keywords: urological cancer, clinical trials, physician recommendation, implementation science, community practice, cancer care delivery

1. INTRODUCTION

Major advances in treatment of urological cancers have been achieved due to successful completion of clinical trials.1,2 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) treatment guidelines for urological cancer care recommend consideration of available clinical trials as standard of care3–6 as do American Urological Association guidelines for bladder7 and prostate cancer.8 Despite strong endorsement and proven contributions of clinical trials, 92% of adult cancer patients do not participate,9 with even lower rates for underserved populations.10–15 Rural cancer patients have recently received attention as an important underserved population.16,17 Rural Americans constitute one-fifth of the US population and bear a disproportionate burden of cancer morbidity and mortality18,19 and thus should be included in clinical trials. However, the degree to which rural cancer patients are adequately represented in cancer clinical trials is uncertain. Several studies suggest rural patients are underrepresented.11,13–15 However, a more recent study, which pools multiple trials within one cancer cooperative group suggests that across all trials rural patients are adequately represented.20

Improved rural representation in some clinical trials may be the result of programs like the National Cancer Institutes’ Community Oncology Research Program which has increased clinical trial participation among rural patients by extending clinical trials to community oncology practices.20 However, the maldistribution of the oncology workforce21 and the substantial proportion of cancer patients cared for by non-oncologists highlight the need for continued efforts to reach rural populations.20

One innovative strategy to maintain representation of rural populations is to integrate other cancer care providers into clinical trial efforts. Many specialists are involved in diagnosing and treating cancer. However, 20% of the US cancer burden is urologic,22 making urologists a potentially valuable partner in increasing rural cancer patients’ access to clinical trials. Although faced with similar maldistribution challenges demonstrated in the oncology workforce, urologists maintain a stronger hold in rural communities than oncologists: 11% of urologists serve rural communities compared to 3% of oncologists.21,23

Despite the high concentration of cancer within their specialty, urological cancer trials accrue patients more slowly than other cancer trials24 Whether this is due to infrastructure limitations or unique barriers urologists face is unknown because relatively little research on physicians’ participation in clinical trials include urologists.12,24,25 Even less is known about the particular challenges faced by urologists practicing in rural settings. We sought to addresses these questions through in-depth exploration of factors influencing rural-serving urologists’ offer of clinical trials.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

To structure this qualitative inquiry, we used the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF), which synthesizes 128 theoretical constructs drawn from 33 theories into 14 constructs relevant to implementation behavior.26 The TDF’s 14 behavioral determinants are further summarized into three essential conditions of behavior change: capability, opportunity, and motivation.27 Capability refers to individual’s psychological and physical capacity to engage in intended activities. Motivation is defined as internal psychological processes that energize and direct behavior. Opportunity includes factors external to the individual that prompt or make behavior possible.27

We conducted semi-structured individual and group interviews on location in urology practices in communities across a rural state. To eliminate distance to trials as a distinct barrier,28 we included only practices with access to urological cancer clinical trials through their hospital’s affiliation with a state-wide infrastructure supporting clinical trials. To identify practices, we obtained a list of urologists from the state licensing board. We included all urologists with a non-federal, active license. We sorted urologists by county and excluded those in metropolitan counties (defined as population ≥50,000). We then identified non-metropolitan counties in which cancer cooperative group trials were offered through an outreach arm of the state’s academic medical center. Urologists were included if their address was in, or adjacent to, the county in which trials were available. We verified urologists’ practice affiliation via practice websites, directory listings, and phone calls to the practice. From the subset of urology practices with locally available trials, we excluded practices beyond a 4-hour driving radius from the university for the initial assessment. Practices were recruited by contacting individual urologists and obtaining agreement for the practice to participate.

Two interviewers visited each enrolled site to conduct individual and small group interviews with urologists and clinical and operational staff. Participants were provided study information and reviewed informed consent prior to participation. The research was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Kansas Medical Center. Past accrual data on participating practices was obtained from the University’s Cancer Center. Characteristics of the practice, including degree of rurality, practice type (solo/group; private/hospital-owned), size, ownership model, hospital size and resources were collected from participants, extant census data and American Hospital Association records.

All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were imported into qualitative analysis software (NVivo29) after anonymization. We conducted template analysis,30 which uses a codebook to search for pre-defined themes and allows examination of emergent themes. The codebook was based on TDF constructs, with definitions and examples provided in previous literature,31,32 and revised throughout the analysis. To assess sample size adequacy, we assessed interviews for saturation, a criterion commonly used in qualitative research.33 After the initial round of data collection we reviewed transcripts to examine consistency in response across practices.

Twenty percent of transcripts were independently coded by two investigators and discrepancies resolved by consensus. Once coding was consistent among investigators, it was completed by a single investigator. Coded constructs were reviewed to identify subthemes.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participant Characteristics and Trial Accrual

We identified 90 urologists with non-federal, active licenses, 72 of whom practiced in metropolitan communities. Of the remaining 18 non-metropolitan area urologists, 14 (grouped into 9 practices) had trials available through the University’s outreach program in their local community; no trials were available near one urology practice. Three solo practices were located beyond the 4-hour driving radius, Of the six community urology practices meeting all inclusion criteria, four (67%) were enrolled. Non-enrollers consisted of one solo practice and one urologist practicing in a multi-specialty clinic. Responses were consistent across practices, indicating saturation had been achieved.Thus we did not contact the solo practices outside the driving radius. Across the four practices (two solo practices and two group practices), we completed interviews with seven physicians and 10 staff members, including nurses, practice managers and other support staff (Table 1). All participating practices were in non-metropolitan communities (population size <50,000) (Table 2). At the time of recruitment, six urological cancer clinical trials were available to community oncology programs in the centralized network. Two accruals to urological trials were attributed to these four rural communities’ cancer programs, accounting for 7% of the academic center’s annual enrollment, whereas three metropolitan community oncology programs accounted for 10% of accrual. We ascertained that both non-metropolitan accruals were obtained for a single study from a single community.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants

| Physician (n=7) | Staff (n=10) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 7 | 1 | ||

| Female | 0 | 9 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 5 | 10 | ||

| Non-White | 2 | 0 | ||

| Mean | Standard Deviation | Mean | Standard Deviation | |

| Age | 53.6 | 16.21 | 44.9 | 9.97 |

| Years in practice | 7.6 | 12.69 | 19.1 | 9.48 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of Practices

| Count (N=4) | |

|---|---|

| Practice Type | |

| Solo | 2 |

| Group | 2 |

| Affiliation | |

| Private | 2 |

| Hospital-Owned | 2 |

| Geographic locations | |

| Rural <2,500 population | 0 |

| Small Town (population = 2,500–9,999) | 1 |

| Micropolitan Area (population = 10,000–49,999) | 3 |

| Number of Employees | |

| < 5 | 1 |

| 5 – 9 | 1 |

| 10 – 14 | 1 |

| ≥ 15 | 1 |

| Number of Physicians | |

| 1 | 2 |

| 2–5 | 2 |

| Local Hospital Bed Size | |

| <100 | 2 |

| 100 – 200 | 0 |

| >200 | 2 |

| Intensity-modulated radiation therapy Facilities | |

| Yes | 4 |

| Surgical Robot | |

| Yes | 3 |

While all practices were in non-metropolitan communities, they differed in size and scope (Table 2). The two solo practices served small communities with populations less than 21,000. The two group practices were also in small communities (approximate populations 20,000 and 47,000), but both served as hubs for extensive outreach with multiple satellite sites (7 and 9 satellite clinics), covering up to nine surrounding counties, some more than two hours away, accessed via airplane.

3.2. Potential Determinants of Offering Clinical Trials

Urologists and their staff described many aspects of capability, opportunity and motivation in relation to their referring behaviors. However, opportunity determinants of trial referral were the most prevalent across all domains.

3.2.1. Opportunity

Both environmental context and resources and social influences were prevalent across all settings and practices. Many participants identified limited time and high workload as barriers to offering trials, which was heightened in the context of under-resourced rural practices. Participants perceived trial referrals requiring an investment of extra resources they could not allocate or secure on their own. They noted discussing trials with patients requires an extra time commitment from already overburdened physicians and staff, and expressed need for additional human resources to provide ongoing support. For example, one urologist commented:

I think we have a good group of urologists here that are very interested in doing what’s going to be best for that patient and the patient population. If it’s good for them…it’s a no brainer, but we do need to have the personnel.

Some suggested that any use of internal resources be incentivized financially. In addition to human and financial resources, participants expressed need for informational resources to support offering trials, such as brochures, videos, and internet sources to share with patients when introducing trials (Table 3, Resources).

Table 3.

Illustrative Quotes of Opportunity Facilitators and Barriers

| TDF Domains | Relevant Themes | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Context | Environmental restrictions in rural communities reduce patient willingness to participate in clinical trials. |

|

| Resources | Trial referrals require additional human resources practices cannot attain on their own. |

|

| Trial referrals require informational resources. |

|

|

| Use of internal resources for trial referrals should be incentivized. |

|

|

| Social Influences | Urologists are willing to refer patients to cancer centers and physicians who are trustworthy. |

|

| Urologists rely on opportunities provided by usual referral partners |

|

|

| Urologists prefer that to receive trial information directly from trial investigators. |

|

|

| Urologists are influenced by patient reactions to their recommendation as well as their knowledge of and perceptions toward clinical trials in general. |

|

|

| Family members influence the referral processes. |

|

You can always give them literature, but I’m not sure they read it, but they might be more apt to play a video and get the information that way.

Despite having trials available in the immediate community, urologists were mindful of access limitations for patients living in more remote rural communities (Table 3, Environmental Context).

Social relationships also create opportunity, including influence from other providers at the cancer center, patients, and patients’ friends and family. Among them, influence from other providers and cancer centers were most important. For example, urologists felt more comfortable referring patients to cancer centers and academic hospitals with positive reputations and to physicians they regard as knowledgeable and trustworthy (Table 3, Social Influences). Participants expected their usual cancer referral partners (academic urologists and local cancer centers) to have processes for clinical trials and preferred their patients receive information directly from trial personnel. They indicated they could be highly influenced by expanding their professional networks to include trial investigators.

It’s getting the people that are involved in developing the clinical trial in front of urologists themselves…maybe just when they developed a new one…talking to them, and basically selling their clinical trial to that doctor so that doctor, one, believes in it and, two, wants to recommend it to their patients.

Urologists perceived patients and their families to strongly influence their offer of clinical trials. They cared about anticipated patient reactions to their recommendation as well as patients’ knowledge of and general perceptions about clinical trials. Some participants were mindful of social influence from patients’ family members and expressed willingness to include relatives when engaging patients (Table 3, Social Influences).

3.2.2. Capability

In the capability domain, knowledge emerged as the most prevalent overarching construct, closely intertwined with memory, attention, and decision processes, and psychological skills Lack of awareness about clinical trials was frequently mentioned, despite availability of urological cancer trials in each community, sometimes as close as the building next door. “We have to know what’s out there because…we simply don’t know what’s available.” Urologists and staff also lacked content and procedural knowledge about trials, which negatively impacts their confidence in presenting trials to their patients (Table 4, Memory, attention and decision processes). The few urologists who already offered trials described needing ongoing communication after referral. Existing trial information was hard to access and required high levels of cognitive processing to apply to patient care. They had inadequate reminder systems and requested systematic pathways to guide their decision processes in identifying and referring patients to trials.

Table 4.

Quotes Illustrating Capability Facilitators and Barriers

| TDF Domains | Relevant Themes | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | Community practices lack knowledge of existing trials. |

|

| Practices want to increase their knowledge of clinical trials through training and education. |

|

|

| Memory, attention, and decision processes | Self-made reminders some urologists use are not always effective. |

|

| Practices lack systematic pathways to manage trial information. |

|

|

| Psychological skills | Practices want more knowledge of clinical trials so that they can effectively explain and answer questions for patients. |

|

Capability determinant Behavioral Regulation was also discussed, but not included in the table.

Participants were aware of significant influences that physicians have on patient treatment decisions and believed urologists should have sufficient knowledge of clinical trials to feel confident about trial recommendations, which translates into cognitive skills, i.e., the ability to effectively explain and address questions about clinical trials, which they saw as an important prerequisite to offering trials. To increase knowledge, many participants expressed need for increased opportunities for basic training rather than being presented with full details about trials (Table 4, Knowledge).

3.2.3. Motivation

In the motivation domain, two TDF constructs, social/professional role & identity and beliefs about consequences, were most common. Regarding the social and professional role, urologists talked about how they view their role within the practice, relative to patients, and relative to other providers in the broader health system. Within the practice, urologists believe it is their responsibility to initiate conversations with the patient about clinical trials in the context of treatment counseling, rather than their staff. “[Talking about trials] is really part of giving the patient their options and making them aware of all of their options including trials.” That should first come from the physician. However, they do see a role for staff in helping them identify relevant trials for patients and further discussions they initiate. Several were conscientious of staff’s workload and were comfortable with, and willing to, delegate trial tasks to external resources such as cancer center trial staff. Urology staff see their role as reminding urologists about available trials, reinforcing doctor’s recommendations for trials, educating patients about trial options, and fielding questions about them (Table 5).

Table 5.

Quotes Illustrative of Motivational Facilitators and Barriers

| TDF Domains | Relevant Themes | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Social/professional role & identity | Urologists and staff consider initiating trial conversation as their role while others also take part in the referring process. |

|

| Urology staff see their role in offering clinical trials. |

|

|

| Urologists see their role in following and co-managing patients on trial. |

|

|

| Urologists feel responsible for maintaining positive professional relationship with their patients after the referral |

|

|

| Beliefs of consequences | Urologists with positive attitudes toward clinical trials were more likely to offer trials to their patients. |

|

| Emotion | Urologists’ emotion, mainly fear, influence their decision to offer trials. |

|

Other motivational determinants discussed included beliefs about capabilities, intentions, optimism, goal setting, and reinforcement.

Urologists state they have a duty to maintain positive doctor-patient relationships and feel it is imperative that trial discussions not interfere. Some recognized it is a urologists’ duty to the patient and their professional obligation to discuss trials. Relative to other providers, urologists recognized their responsibility to be aware of trials, to refer patients to oncologists or urologists specializing in cancer for treatment options they cannot offer, but not being responsible for eligibility screening (Table 5, Professional Role). Many were comfortable referring patients to clinical trials rather than treating them, particularly when they had exhausted treatment options available to them. They likened trial investigators to other specialists they could refer to, envisioning they could instruct a patient to see a trial investigator for more information and “then come back and talk with me about it.” Urologists expect trial experts to send communication back about the referred patients’ eligibility and ultimate trial status. They also expect to discuss specifics of any co-management responsibilities as they feel the community urologist still has responsibility for patients’ care, irrespective of trial participation (Table 5, Professional Role). Because urologists in small communities interact with patients outside the clinic, they need to know the management plan, even if they are not responsible. Urologists who had referred patients to trials did not necessarily see their role diminishing once a patient enrolled in a trial. Community urologists also had additional expectations of trial investigators: to inform them about available trials both as periodic reminders and to increase their confidence in making referrals.

Regarding beliefs about consequences, participants who believed in benefits of clinical trials, such as advancing medicine, were more favorable toward offering trials (Table 5, Beliefs). Similarly, those who believe they are providing quality of care by offering clinical trials to their patients with limited treatment options were more receptive to recommending trials.

4. DISCUSSION

We sought to explore the opportunity, capability and motivation of rural-serving urology practices in offering clinical trials to their patients. Despite having trials available in their communities, participating practices had limited awareness of available trials because they lacked social connections with those conducting trials. They also lacked useable and actionable information about trial opportunities. Urologists and staff had limited capability to initiate trial discussions and no processes to integrate trials into their workflow. Nonetheless, rural urologists were motivated to offer trials because they see trials as extending available treatment options, which is aligned with their professional role. Further, they were receptive to interventions to help them offer trials to their patients. They perceive a need for education about trials to increase knowledge, improve confidence, and potentially advance their understanding of rural patients’ concerns about and receptiveness to trials. Urologists indicated that dedicated resources are necessary and were receptive to external facilitation to achieve the goal.

Our findings confirm and extend previous work describing urologists’ attitudes regarding cancer clinical trials.24,25 In a national survey of urologists, participants reported holding positive attitudes about cancer clinical trials.24 Those survey participants saw a wide range of benefits from clinical trial participation to their patients and their practice, and had no objections to trials based on philosophical, ethical, or business grounds, consistent with our findings. Similar to participants in our study, the survey participants, particularly those who did not currently participate in trials, lacked incentive to offer clinical trials, educational opportunities to learn about trials, and systems through which to enroll patients.24 Previous literature has often characterized trial participation as potentially hindering the patient-physician relationship.34,35 In slight contrast, our findings suggest that, because of the value urologists place on the patient-physician relationship, emphasizing how offering clinical trials may enhance that relationship could provide the missing incentive, especially to the extent urologists compete with other providers for patients.

Urologists in this study perceived that rural patients were less receptive to trials than non-rural patients, a finding consistent with other literature.24,36 Indeed rural patients, whether due to education, income, or distance, may be more reluctant to participate. It has recently been demonstrated that rural patients may participate in a representative fashion if sufficient resources are provided to support the recruitment effort.20 Improvements in participation have been attributed to programs such as NCI’s NCORP.20 However, rural patients tend to have more negative attitudes toward trials. Thus, these efforts may need to be supplemented by direct outreach to rural populations featuring messages from their local healthcare providers.36

Low income patients, who are overrepresented in rural populations, are less likely to enroll in clinical trials and have a higher level of cost related concerns.37 Cancer patients bear a high financial burden for their treatment costs.38–41 Because treatment costs are the patient’s responsibility and only clinical trial costs are paid by study sponsors, uninsured patients may have difficulty participating in clinical trials. However, even uninsured patients may have difficulty participating in clinical trials. Although treatment and study costs may be covered for most insured patients, clinical trial participation may involve slightly higher incremental out-of-pocket costs compared to regular cancer care.42–45 Thus, urologists and staff should be educated on costs as well as benefits associated with participation in clinical trials and feel comfortable referring patients to trial specialists. Trial specialists should be able to accurately counsel patients, and may be able to help determine coverage and incremental costs, provide potential assistance,44 and address patients’ concerns so they can make informed decisions about trial participation.

Our results suggest environmental and staffing constraints may be additional limiting factors for urologists in rural practices. Although community urology practices across all geographic regions may be under-resourced, resource scarcity may be particularly important in non-metropolitan practices, which tend to be smaller groups or solo practices. Existing programs to extend trials to community urology practices (e.g., the Society of Urological Oncology-Clinical Trials Consortium) require practices to provide dedicated research personnel, limiting feasibility for solo and smaller group practices. However, in our study, urologists serving rural communities were willing to explore opportunities to collaborate with reputable cancer centers and regional oncologists. Delegation of tasks (beyond recommending a treatment path) fit well within self-perceived roles of urologists and their staff. Programs that provide external facilitators, rather than practice investment may generate greater uptake. Informational handouts or multimedia were welcomed and could be used to provide patient education deemed part of the urologist’s responsibility, but beyond resources at hand.46 If tailored to rural patients, these materials could further address barriers to participation.46

This study further extends previous work in two additional ways. First, we identified these rural urologists lack social networks with trial investigators who they and their staff perceive to be highly influential in encouraging them to offer clinical trials. Swanson et al. (2007) found a statically significant association between the urologist having an academic mentor who valued research and currently offering trials,24 but did not investigate the potential role of trial investigators directly championing trials to urologists. Study participants highly value face-to-face contact with trial investigators, a strategy demonstrated to be effective among primary care physicians.47 Second, offering clinical trials was consistent with rural urologists’ professional identity, as they perceive their job is to offer all appropriate treatment options to their patients. Because congruence of role identity with a new behavior is theorized to promote adoption of the behavior,48 promoting the offer of clinical trials as an extension of available treatment options may further enhance uptake.

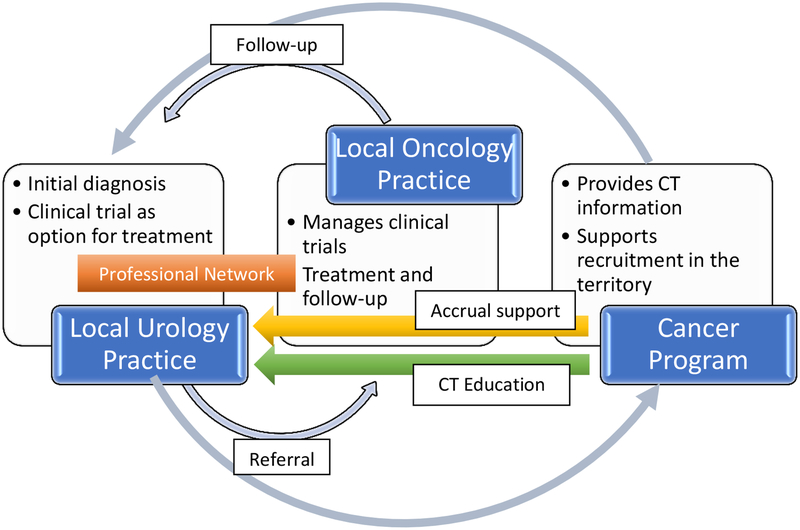

Based on these theoretically informed findings, we have identified several intervention components which may be effective in expanding the reach of cancer clinical trials to urological patients. First, disseminating information about available clinical trials to urologists is needed. Enriching dissemination efforts with face-to-face contacts from local study investigators and research personnel may increase integration of this information into patient care. Further, framing clinical trials as potential treatment option for all cancer patients and facilitating integration of reminders and support into the workflow at this junction may also aid implementation. Providing brief skills training at local and regional meetings that community urologists and their staff attend could increase confidence in offering trials. Developing adequate patient education materials about clinical trials in formats acceptable to rural populations could alleviate burden on urology practices and provide patients with consistent, accurate information that can facilitate their transition to the clinical trial expert. Finally, establishing clear communication about co-management responsibilities between the referring urologist and the clinical trial consult and ensuring feedback from cancer programs about eligibility screening and enrollment may foster urologists’ willingness to try referrals. Figure 1 suggests a way that practices and stakeholders could work together.

Figure 1.

Suggested patient and information flow to promote accrual to urologic clinical trials.

4.1. Limitations and Future Research

The current study is not without limitations. We did not interview patients or their caregivers, and are unable to validate the patients’ perspectives urologists described. Instead, we chose to focus on the physicians’ offer of clinical trials. A large body of literature describes patients’ barriers to clinical trial accrual and consistently finds that physician offer is highly influential in their decision to participate: Seventy percent of pattern variation for clinical trial enrollment is reported to be associated with physician effort to engage patients, and 73% of patients who enrolled in a clinical trial were motivated by their physician’s recommendation.12

Participating practices were limited to rural counties in a single state. Results may not be generalizable to practices in metropolitan areas or other states. We limited our study to communities which had access to NCI-sponsored trials. Results may not be relevant for communities without these opportunities28 or with only industry-sponsored trials.49 Future research should validate findings among practices in a variety of geographic settings and should monitor the distance a patient must travel to participate in a trial. Further, because our qualitative methodology does not allow us to ascertain the magnitude of the impact these determinants may have on the offer of clinical trials, additional research to quantify the relative importance of these factors is warranted. A survey of a representative sample of urologists could address both the generalizability of these findings and help prioritize which determinants should be targeted for intervention. Including such items in the American Urological Association census, an extant survey with high response rates,23 may be a feasible approach to obtaining this data. Finally, we offer some potential interventions to address these disparities, but formal intervention mapping to identify interventions which can address these determinants is warranted.50

5. CONCLUSIONS

Rural-serving urology practices present important opportunities to increase cancer clinical trial accrual. With adequate relational, logistical and informational support, these practices could help advance cancer research and increase treatment options for urological cancer patients. Implementation strategies which address determinants of the clinical trial offer among rural urologists are potentially viable. Future studies should explore effectiveness of strategies to optimize rural urology practices’ role in clinical trials accrual and assess the degree to which these findings apply to and impact other urology practices.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Non-metropolitan community urology practices present important opportunities to increase cancer clinical trial accrual.

Even in communities with available cancer clinical trials, practices have limited awareness of trials because they lack social connections with trial investigators.

Rural-serving urologists were motivated to offer trials because they see trials as extending available treatment options, which is aligned with their professional role.

Practices were receptive to interventions, including external facilitation, to help them offer trials to their patients.

Acknowledgements:

We appreciate the contributions of the Midwest Cancer Alliance, KU Cancer Center, and urology practices across the state of Kansas.

Financial Support: This study was supported by a grant from the Brown Performance Group; Dr. Ellis was supported by a Mentored Training in Dissemination and Implementation Research in Cancer (MT-DIRC) award (R25 CA171994).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial conflict of interest: none

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Taguchi S, Fukuhara H, Homma Y, Todo T. Current status of clinical trials assessing oncolytic virus therapy for urological cancers. Int J Urol. 2017;24(5):342–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin RM, Donovan JL, Turner EL, et al. Effect of a Low-Intensity PSA-Based Screening Intervention on Prostate Cancer Mortality: The CAP Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018;319(9):883–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Comprehensive Cancer Network I. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Testicular Cancer. 2018; version 2:https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/testicular.pdf. Accessed July 17, 2018.

- 4.National Comprehensive Cancer Network I. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Kidney Cancer. 2018; 4:https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/kidney.pdf. Accessed July 17, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.National Comprehensive Cancer Network I. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Prostate Cancer. 2018; 3:https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf. Accessed July 17, 2018.

- 6.National Comprehensive Cancer Network I. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Bladder Cancer. 2018; 5:https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/bladder.pdf. Accessed July 17, 2018.

- 7.American Urological Association. Diagnosis and Treatment of Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer: AUA/SUO Joint Guideline. 2016; http://www.auanet.org/guidelines/bladder-cancer-non-muscle-invasive-(2016). Accessed July 17, 2018.

- 8.American Urological Association. Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO Guideline. 2017; http://www.auanet.org/guidelines/prostate-cancer-clinically-localized-(2017). Accessed July 17, 2018.

- 9.Network ACSCA. Barriers to Patient Enrollment in Therapeutic Clinical Trials for Cancer: A Landscape Report. Washington, D.C.2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jimenez R, Zhang B, Joffe S, et al. Clinical trial participation among ethnic/racial minority and majority patients with advanced cancer: what factors most influence enrollment? Journal of palliative medicine. 2013;16(3):256–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanner A, Kim S-H, Friedman DB, Foster C, Bergeron CD. Promoting clinical research to medically underserved communities: current practices and perceptions about clinical trial recruiting strategies. Contemporary clinical trials. 2015;41:39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Comis RL, Miller JD, Aldigé CR, Krebs L, Stoval E. Public attitudes toward participation in cancer clinical trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21(5):830–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baquet CR, Ellison GL, Mishra SI. Analysis of Maryland cancer patient participation in national cancer institute-supported cancer treatment clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(20):3380–3386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zullig LL, Fortune-Britt AG, Rao S, Tyree SD, Godley PA, Carpenter WR. Enrollment and Racial Disparities in Cancer Treatment Clinical Trials in North Carolina. N C Med J. 2016;77(1):52–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sateren WB, Trimble EL, Abrams J, et al. How sociodemographics, presence of oncology specialists, and hospital cancer programs affect accrual to cancer treatment trials. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(8):2109–2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sciences DoCCaP. Research Emphasis. 2018. Accessed October 1, 2018, 2018.

- 17.Martinez ME, Paskett ED. Using the Cancer Moonshot to Conquer Cancer Disparities: A Model for Action. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(5):624–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blake KD, Moss JL, Gaysynsky A, Srinivasan S, Croyle RT. Making the case for investment in rural cancer control: an analysis of rural cancer incidence, mortality, and funding trends. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henley SJ, Anderson RN, Thomas CC, Massetti GM, Peaker B, Richardson LC. Invasive Cancer Incidence, 2004–2013, and Deaths, 2006–2015, in Nonmetropolitan and Metropolitan Counties - United States. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66(14):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Unger JM, Moseley A, Symington B, Chavez-MacGregor M, Ramsey SD, Hershman DL. Geographic distribution and survival outcomes for rural cancer patients treated in clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(15). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirkwood MK, Bruinooge SS, Goldstein MA, Bajorin DF, Kosty MP. Enhancing the American Society of Clinical Oncology workforce information system with geographic distribution of oncologists and comparison of data sources for the number of practicing oncologists. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(1):32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.U.S. Cancer Statistics Data Visualizations Tool, based on November 2017 submission data (1999–2015): [computer program]. US. Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Urological Association. The State of the Urology Workforce and Practice in the United States 2016. 2017; 2016:http://www.auanet.org/research/data-services/aua-census/census-results. Accessed July 14, 2017, 2017.

- 24.Swanson GP, Carpenter WR, Thompson IM, Crawford ED. Urologists’ attitudes regarding cancer clinical research. Urology. 2007;70(1):19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobs SR, Weiner BJ, Reeve BB, Weinberger M, Minasian LM, Good MJ. Organizational and physician factors associated with patient enrollment in cancer clinical trials. Clinical Trials. 2014;11(5):565–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, et al. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(1):26–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atkins L, Francis J, Islam R, et al. A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implementation Science. 2017;12(1):77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borno HT, Zhang L, Siegel A, Chang E, Ryan CJ. At What Cost to Clinical Trial Enrollment? A Retrospective Study of Patient Travel Burden in Cancer Clinical Trials. Oncologist. 2018;23(10):1242–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.NVivo qualitative data analysis Software [computer program]. 55 Cambridge Street Burlington, MA 01803 USA: QSR International Pty Ltd; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Symon G, Cassell C. Qualitative methods and analysis in organizational research: A practical guide. 12th ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd; ; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Birken SA, Presseau J, Ellis SD, Gerstel AA, Mayer DK. Potential determinants of health-care professionals’ use of survivorship care plans: a qualitative study using the theoretical domains framework. Implementation science : IS. 2014;9(1):167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ciprut S, Sedlander E, Watts KL, et al. Designing a theory-based intervention to improve the guideline-concordant use of imaging to stage incident prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2018;36(5):246–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches 4th Ed Los Angeles, California: SAGE Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ross S, Grant A, Counsell C, Gillespie W, Russell I, Prescott R. Barriers to participation in randomised controlled trials: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(12):1143–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rahman S, Majumder MA, Shaban SF, et al. Physician participation in clinical research and trials: issues and approaches. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2011;2:85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geana M, Erba J, Krebill H, et al. Searching for cures: Inner-city and rural patients’ awareness and perceptions of cancer clinical trials. Contemporary clinical trials communications. 2017;5:72–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Unger JM, Hershman DL, Albain KS, et al. Patient income level and cancer clinical trial participation. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(5):536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winkfield KM, Phillips JK, Joffe S, Halpern MT, Wollins DS, Moy B. Addressing Financial Barriers to Patient Participation in Clinical Trials: ASCO Policy Statement. J Clin Oncol. 2018:JCO1801132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dusetzina SB, Huskamp HA, Winn AN, Basch E, Keating NL. Out-of-Pocket and Health Care Spending Changes for Patients Using Orally Administered Anticancer Therapy After Adoption of State Parity Laws. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(6):e173598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knight TG, Deal AM, Dusetzina SB, et al. Financial Toxicity in Adults With Cancer: Adverse Outcomes and Noncompliance. J Oncol Pract. 2018:JOP1800120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leech AA, Dusetzina SB. Cost-Effective But Unaffordable: The CAR-T Conundrum. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldman DP, Berry SH, McCabe MS, et al. Incremental treatment costs in National Cancer Institute–sponsored clinical trials. Jama. 2003;289(22):2970–2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kilgore ML, Goldman DP. Drug costs and out-of-pocket spending in cancer clinical trials. Contemporary clinical trials. 2008;29(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nipp RD, Lee H, Powell E, et al. Financial Burden of Cancer Clinical Trial Participation and the Impact of a Cancer Care Equity Program. Oncologist. 2016;21(4):467–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nipp RD, Powell E, Chabner B, Moy B. Recognizing the Financial Burden of Cancer Patients in Clinical Trials. Oncologist. 2015;20(6):572–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jacobsen PB, Wells KJ, Meade CD, et al. Effects of a brief multimedia psychoeducational intervention on the attitudes and interest of patients with cancer regarding clinical trial participation: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(20):2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams CM, Maher CG, Hancock MJ, McAuley JH, Lin C-WC, Latimer J. Recruitment rate for a clinical trial was associated with particular operational procedures and clinician characteristics. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2014;67(2):169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Annals of behavioral medicine. 2013;46(1):81–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sateren WB, Trimble EL, Abrams J, et al. How sociodemographics, presence of oncology specialists, and hospital cancer programs affect accrual to cancer treatment trials. Journal of clinical oncology. 2002;20(8):2109–2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.French SD, Green SE, O’Connor DA, et al. Developing theory-informed behaviour change interventions to implement evidence into practice: a systematic approach using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implementation science : IS. 2012;7:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]