Abstract

Among the many anthropogenic changes that impact humans and wildlife, one of the most pervasive but least understood is light pollution. Although detrimental physiological and behavioural effects resulting from exposure to light at night are widely appreciated, the impacts of light pollution on infectious disease risk have not been studied. Here, we demonstrate that artificial light at night (ALAN) extends the infectious-to-vector period of the house sparrow (Passer domesticus), an urban-dwelling avian reservoir host of West Nile virus (WNV). Sparrows exposed to ALAN maintained transmissible viral titres for 2 days longer than controls but did not experience greater WNV-induced mortality during this window. Transcriptionally, ALAN altered the expression of gene regulatory networks including key hubs (OASL, PLBD1 and TRAP1) and effector genes known to affect WNV dissemination (SOCS). Despite mounting anti-viral immune responses earlier, transcriptomic signatures indicated that ALAN-exposed individuals probably experienced pathogen-induced damage and immunopathology, potentially due to evasion of immune effectors. A simple mathematical modelling exercise indicated that ALAN-induced increases of host infectious-to-vector period could increase WNV outbreak potential by approximately 41%. ALAN probably affects other host and vector traits relevant to transmission, and additional research is needed to advise the management of zoonotic diseases in light-polluted areas.

Keywords: ecoimmunology, anthropogenic, light pollution, host competence, reservoir host

1. Introduction

Among the many anthropogenic changes that impact humans and wildlife, one of the most pervasive but least understood is light pollution [1]. Artificial light at night (ALAN) is a common form of light pollution worldwide in both urban centres and non-urban areas including farms, airports, warehouses and even natural areas such as green spaces near roadways [2,3]. Early research on human health found that individuals working throughout the night routinely suffer higher rates of type II diabetes, heart conditions and other non-infectious maladies compared to day-working staff [4]. In domesticated rodents, exposure to short-wavelength light at night, similar to that of cool-white LEDs, has been linked to metabolic dysregulation, immunosuppression and the development of some cancers [4]. Levels of blue light (420–480 nm) as low as 0.2 lx can suppress melatonin secretion in humans [5,6], and in wildlife, comparable forms of ALAN alter many behavioural, life history and physiological traits [7,8].

Despite the diverse and strong effects of ALAN, no study has yet investigated whether and to what degree it might affect infectious disease risk, which is surprising given that many hosts and vectors use light cues to coordinate daily and seasonal rhythms [9,10]. Light is among the most reliable environmental cues, and light regimes induce temporal fluctuations in immune defences and other factors that influence the risk of infection [11]. Our goal here was to discern whether ALAN could alter zoonotic disease risk for humans and wildlife by changing the ability of a reservoir host to amplify virus for subsequent transmission, and if so, to implicate some molecular mechanisms that might be responsible for these changes. Differences in transmission ability between individual hosts, which we term host competence [12–14], are partly mediated by endocrine-sensitive physiological processes [11,15]. For example, melatonin and glucocorticoids both affect host behaviours driving exposure risk as well as immune defences underlying resistance to infection and transmissibility [16,17].

We investigated ALAN effects on West Nile virus (WNV) infections in house sparrows (Passer domesticus) because this species is among the most common infection reservoir in light-polluted areas and a close commensal of humans [18]. House sparrows are also among the more competent hosts for WNV [19], which we chose as our pathogen for two reasons: (i) more than 46 000 cases of WNV-induced human disease have been reported across the US since its introduction to New York in 1999 [20]; and (ii) following its emergence in the US, WNV decimated avian populations, particularly corvids and other passerine species that commonly occupy light-polluted habitats [21].

2. Material and methods

(a). Capture and housing

We captured house sparrows using mist nets at two sites in the Tampa Bay area with comparable levels of light pollution. All birds were captured between the hours of 5.30 and 9.30. Birds were then transported to the University of South Florida vivarium where they were housed individually in 13″ × 15″ × 18″ cages for the next 7–25 days in visual and audial proximity to each other. In captivity, birds were housed under ALAN/treatment (12 L : 12 D approx. 8 lx artificial light; n = 23) or natural light/control conditions (12 L : 12 D; n = 22). Food (mixed seeds) and water were provided ad libitum throughout the study. Following this initial period, all birds were transported to the USF Biosafety level-3 (BSL-3) suite where they were kept individually in similar cages but inside bioBUBBLE containment systems (bioBUBBLE Inc, Fort Collins CO). Light conditions during this period were identical to conditions described earlier.

(b). Dexamethasone suppression test

To examine HPA function, we performed the dexamethasone (DEX) suppression test twice: once at capture and once after 7–25 days in captivity. Blood samples for the DEX suppression test required: (1) a baseline corticosterone (CORT) sample obtained within 3 min of capture, (2) a post-stressor blood sample collected after 30 min of restraint in a cloth bag following initial capture, which was immediately followed by a DEX injection (s.q., 28 µg dissolved in 50 µl peanut oil) and (3) a final sample collected 1 h after injections. Blood samples were collected from the brachial vein using sterile 26-gauge needles and microcapillary tubes, and serum was frozen at −20°C until hormone assay.

(c). West Nile virus infection

Following transfer to the BSL-3 facility, we exposed all birds (n = 45) to 101 (PFU) of WNV, NY99 strain via subcutaneous inoculation within the same time frame [22] (ALAN exposure duration varied to determine if time of ALAN exposure affected infection outcomes but was not a significant term in models, so it is not further addressed). Following WNV exposure, all birds were maintained under the same light regimes while we sampled serum on days 2, 4, 6 and 10 to quantify WNV viraemia in circulation [23]. We also measured body mass (to 0.1 g prior to and on each blood sampling day) to assess effects on individual health and group WNV-induced mortality (mortality was closely monitored from the point of exposure through day 10, when the experiment was concluded). Serum and whole blood samples were frozen at −20°C until extraction, and qPCR or sequencing methods protocols were performed.

(d). Corticosterone assays

CORT concentrations were quantified in serum using an enzyme immunoassay kit from Arbor Assays (Arbor Assays, Ann Arbor, MI, product no. K014-H5; [13]). Samples were run in duplicate and standardized across plates. Concentrations were derived from known values along the standard curve, and all values fell within the curve.

(e). RNA extraction and real-time polymerase chain reaction for viraemia

WNV RNA was extracted from 10 µl of stored serum using the Qiagen QIAmp Viral Extraction Mini Kit (Qiagen Cat. No. 52906). Viraemia was quantified using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction using a one-step Taqman kit (iTaq Universal Probes One-Step Kit; Bio-Rad Cat. No. 1725141). Standards were extracted from known concentrations (via plaque-assay) of WNV stock and quantified using the same methods listed earlier. Forward and reverse primers and probe sequences are listed in electronic supplementary material, text [23]. All samples were run in duplicate with negative controls.

(f). West Nile virus and corticosterone statistical analyses

Linear mixed models were used in Rstudio and SPSS to analyse most data, after log10 transformation of WNV viraemia which produced variable distributions amenable to model assumptions. Statistics in the electronic supplementary material, text confirm that analyses conducted in both programmes were consistent. We first modelled viraemia as a dependent variable in which ALAN conditions, days post-exposure and their interactions were fit as fixed effects. Given the repeated measures nature of the study, we used the individual bird as a random effect. We modelled WNV tolerance in a similar fashion except that in these models, body mass change (from pre-WNV values) was the dependent variable. To account for unequal variance among groups, we performed several iterations of this model that accounted for this and compared them using an ANOVA; because the models were not significantly different, we reported the conservative estimates provided by the linear mixed model allowing for unequal variance (electronic supplementary material, text). We included all data over the course of the entire infection and used days post-exposure, ALAN and WNV titter (as a continuous covariate) and all two- and three-way interactions as predictors [24]. As above for viraemia, the individual bird was included as a random effect and body mass prior to WNV exposure was included as a covariate to control for pre-existing differences in vigour among individuals [24]. CORT data were analysed similarly to viraemia with the following exceptions. First, we conducted an omnibus mixed model in which CORT was the dependent variable and time in captivity, ALAN and their interaction were fixed effects with individual bird as a random effect. In a second series of models, we analysed each of four HPA traits separately: baseline CORT (first measurement), post-stressor CORT (second measurement), post-dexamethasone CORT (third measurement) and total CORT (area under the total concentration curve), as each variable serves a distinct physiological role across the time period which they were sampled and hence could affect WNV competence differently. In these simpler mixed models, time was binary (at capture versus after a period of captivity but prior to WNV exposure), but otherwise model composition was identical to the omnibus models. Finally, we used Cox regression to assess effects of ALAN on direct mortality risk to WNV. We set alpha to less than 0.05 and used SPSS v. 24 and GraphPad Prism for analyses and figure production, respectively.

(g). Outbreak potential modelling

Using a previously developed model [25], the pathogen basic reproductive number can be written as

where a is the bite rate, b and c are the respective probabilities that birds and mosquitoes are infected by a bite, IP is the bird host infectious period, m is the mosquito mortality rate, k is the WNV development rate in the mosquito and M/B is the ratio of adult mosquitoes to birds.

Assuming that ALAN only affects host competence traits measured in the experiment (i.e. infectious period) and does not affect vector traits, the proportionate change in the reproductive number due to ALAN is

The infectious periods of ALAN and control birds were estimated as the total amount of time for which viraemia exceeds the 105 transmission threshold, yielding respective values of approximately 4 and 2 days. This results in a change in outbreak potential, 1%.

To estimate the absolute outbreak potential in the presence and absence of ALAN (R0(ALAN), R0(control) respectively), we estimated the remaining component parameters of the reproductive number from experiments and the literature; where ranges of parameters were reported, we took the approximate midpoint value (electronic supplementary material, text). The parasite development rate and adult mosquito mortality were calculated as the inverses of the reported extrinsic incubation periods of WNV and Culex quinquefasciatus, a common and competent WNV vector in Florida, lifespan, respectively [26]. The resulting values for R0 in the presence and absence ALAN were R0(ALAN) = 12.66 and R0(control) = 8.95.

(h). Whole blood RNA extraction and sequencing

RNA was processed and sequenced following the protocols described by Louder et al. [27]. Following sequencing, reads were adapter trimmed with Trim Galore v. 0.3.8 [28]. Trimmed reads were then aligned to the zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata) v. 3.2.4 reference genome [29] with STAR v. 2.5.3 [30] specifying ‘–sjdbOverhang 74’. We assigned Ensembl gene IDs and quantified reads with htseq-count v. 0.6.0 [31] specifying ‘-s reverse’ to account for the strand-specific library preparation. A total of 9688 genes with an average count value greater than 5 across all 18 samples were used to generate a count matrix and retained for downstream analysis.

(i). RNA sequencing—differential expression

DEseq2 v. 1.21.21 [32] was used to read in the count matrix and perform normalization of counts to sequencing depth. Normalized counts of each sample were then rlog transformed and visualized via principal components analysis within the pcaExplorer R package (electronic supplementary material, figure S4) [27]. We generated the DEseq model ‘∼ nested.ind + TreatDay’, where ‘nested.ind’ accounts for repeated sampling of individuals and ‘TreatDay’ is a grouping variable of the interaction between treatment and day (i.e. four groups: 2dpe-Control, 2dpe-ALAN, 6dpe-Control and 6dpe-ALAN). We then extracted results from the model selecting pairwise contrasts between 2dpe-ALAN versus 2dpe-Control, 6dpe-ALAN versus 6dpe-Control, Control-6dpe versus 2dpe and ALAN-6dpe versus 2dpe. In each case, we used the ‘lfcShrink’ function within DEseq2 to perform log2 fold change shrinkage to enhance visualization of individual gene expression plots. DEseq2 performs a Wald test followed by false discovery rate (FDR) [28] correction to determine differential expression (DE). We classified genes with an FDR less than 0.10 as DE, which is the standard for DEseq analyses and default determined by the package; values listed for the FDR less than 0.05 are in the electronic supplementary material text. As the interaction term between treatment and day on viraemia was significant on day 6, we were primarily interested in the effects of light pollution on gene expression at this point. We further filtered the comparisons of 6dpe-ALAN versus 2dpe-ALAN and 6dpe-ALAN versus 6dpe-Control. For 6dpe-ALAN versus 2dpe-ALAN, we eliminated genes that were also DE in the 6dpe-Control versus 2dpe-Control. As the control birds were also infected with WNV, this isolates the genes responding to both WNV and ALAN treatment in the 6dpe-ALAN birds. For 6dpe-ALAN versus 6dpe-Control, we removed genes also DE in the 2dpe-ALAN versus 2dpe-Control comparison. This eliminates genes that did not change in relative expression level between sampling points. In each of these filtration steps, we only removed genes with the same regulation pattern (i.e. up or down), as we were interested in genes that show the opposite expression patterns between days and/or treatments.

For each of the four DEseq2 comparisons, we performed gene ontology (GO) analysis with the GOrilla webserver [33] after converting zebra finch Ensembl IDs to gene symbols in the Ensembl-BioMart webserver [34,35]. A total of 7321 of 9688 had associated gene symbols. We then sorted DEseq2 results by ascending FDR value and used the entire ranked list of 7321 genes to perform GO analysis. A GO category was considered significantly enriched if the FDR value was less than 0.05.

Lastly, we performed cell type enrichment analysis with the CTen tool [36]. CTen identifies cell types from heterogeneous tissue (e.g. whole blood) transcriptomic data. Here, we restricted our analysis to DE genes, separated into up- and downregulated, in the d6 ALAN versus Control and ALAN d6 versus d2 contrasts. This approach helps distinguish whether gene expression differences were due to changes in transcription or relative cell type abundance following infection and ALAN treatment. We followed the ‘Advanced Example’ on the CTen Webserver (http://www.influenza-x.org/~jshoemaker/cten/advanced_example.php), and a cell type was considered significantly enriched with an enrichment score of greater than 2.

(j). RNA sequencing—weighted gene network correlation analysis

We used weighted gene network correlation analysis (WGCNA) v. 1.64-1 [37] to cluster genes with correlated gene expression into modules and then test these modules for associations with experimental groups. To generate the input for WGCNA, we first performed a variance-stabilized transformation of read counts on all 9688 genes in DEseq2. We then removed 59 genes that had a median absolute deviation of zero, for a total input of 9628 genes. We generated a signed network with the following parameters: soft threshold power (β) = 18, minimum module size = 30 and module dissimilarity threshold = 0.1. We then tested modules for associations with day, treatment and individual treatment × day groups. For module–trait correlations of interest, we visualized module gene expression with heatmaps and performed a target versus background GO analysis in GOrilla testing module genes (target) against all genes (background) used in the analysis. Lastly, we visualized module hub genes with Visant [37]. To do so, we restricted our visualization the top 300 genes ranked by intramodular connectivity from each module. Within these 300 genes, we calculated the topological overlap (i.e. strength of interaction) between each gene and ranked descending. We plotted the top 300 strongest interactions and identified the top 1–6 genes with the highest number of connections (degree distribution) to other genes and classified these as the module hubs.

3. Results

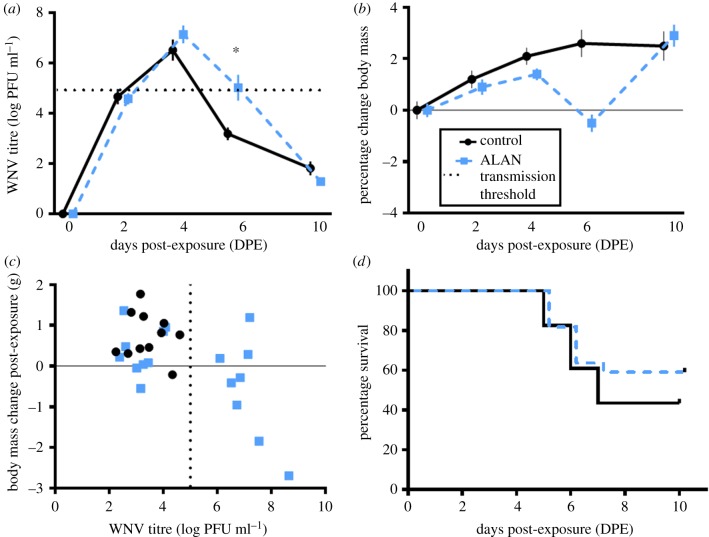

We detected a significant effect of ALAN on the temporal course of WNV viraemia in house sparrows (ALAN × day: F4,124 = 2.9, p = 0.023, 4 time points; figure 1a [no main effect]). At 2–4 days post-exposure (dpe; all animals became infected), both ALAN-exposed and control birds had comparable viral titres. However, at 6 dpe, the interaction between ALAN treatment and dpe was significant (t = 2.7, p = 0.009). Post hoc analyses (conducted using ‘emmeans’ in R studio) further confirmed the existence of a significant interaction (treatment × 6 dpe t = −2.9, p = 0.005 [electronic supplementary material, text]).The conservative estimate for minimum circulating viral titre needed to transmit WNV to vectors is approximately 105 plaque-forming units (PFU; horizontal dashed line in figure 1a; [38]), suggesting the ALAN-exposed individuals remained infectious longer than controls. Specifically, eight ALAN-exposed sparrows possessed viral titres above the transmission threshold whereas no control birds were infectious at 6 dpe (figure 1c).

Figure 1.

West Nile virus infection viraemia, body mass and WNV-induced mortality results. Effects of experimental West Nile virus exposure on house sparrows (Passer domesticus) exposed to artificial light at night (ALAN; 8 lx during night hours for two to three weeks prior to WNV exposure) versus controls (animals kept on 12 L : 12 D for duration of experiment). Blue points and dashed lines signify ALAN-exposed individuals, and black points and solid lines signify controls. (a) Individuals exposed to ALAN had significantly higher viral titers on d6 post-exposure, indicated by the asterisk. The horizontal dashed light represents the conservative transmission threshold or the minimum amount of virus in circulation required to transmit WNV to a vector (i.e. 105 PFU). (b) Effects of WNV and ALAN on change in group mean body mass throughout the course of WNV infection. On d6, ALAN-exposed individuals lost appreciable mass whereas controls continued to gain body mass. (c) Relationship between WNV titre and body mass change on d6 post-WNV exposure. The vertical dashed line represents the WNV transmission threshold; individuals to the right of this dashed line are infectious to mosquitoes, and individuals to the left of this dashed line are not. Only ALAN-exposed individuals were infectious on d6. (d) No effect of ALAN on WNV-induced mortality. (Online version in colour.)

In previous studies, we found that CORT, an avian stress hormone, enhanced host-attractiveness to Culex mosquito vectors [39] and increased WNV viraemia above the transmission-to-vector threshold [38]. Given these results, we investigated whether any effects of ALAN on WNV competence could be explained by increases in CORT using the DEX suppression test [40]. We found that CORT was unlikely to be involved in the observed ALAN effects in the present study, as there was little evidence that ALAN affected HPA function (treatment: F1,40 = 2.8, p = 0.104). To further probe whether ALAN effects on WNV competence were mediated by HPA dysregulation, we included CORT values in models to predict viraemia and tolerance; however, no single measure (baseline, stressor-induced or post-dexamethasone concentrations or the integral of CORT over the measurement period) was a significant predictor in any model.

Additionally, our study was designed to determine whether duration of ALAN exposure influenced corticosterone regulation or viraemia. Hence, birds were exposed to ALAN in captivity for a range of 7–25 days. However, days in captivity had no effect on viraemia in the mixed models (p = 0.802; electronic supplementary material, text); thus, we binned all birds under either ALAN or control groups and removed this term from further iterations of the models.

We next asked whether ALAN might modify the capacity of individuals to tolerate WNV or ameliorate damage associated with infection (e.g. maintain body mass while infected sensu [41]). A linear mixed model involving body mass as the dependent variable, treatment, day and their interaction as fixed effects and individual bird as a random effect was built using the ‘nlme’ software package in R. We found no effect of ALAN on WNV tolerance across the entire post-WNV-exposure period (ALAN × integrated WNV titre: F1,34 = 1.3, p = 0.257). However, birds with the highest WNV titres overall lost more body mass than birds with lower cumulative titres (integral WNV titre: F1,34 = 6.6, p = 0.015). Subsequently, we assessed directly whether body mass changed over time differently in ALAN-exposed and control birds after WNV infection. Birds in the control group gained mass post-infection, whereas body mass reached a nadir in ALAN-exposed birds 6 dpe (figure 1b); mass gain in virally infected birds is counterintuitive, but has precedent [42]. Again, post hoc analyses (‘emmeans’ in Rstudio) indicate that body mass differed at day 6 between controls and ALAN birds (treatment × 6 dpe t = 2.8, p = 0.007). On 10 dpe, body mass returns to comparable levels between groups (figure 1b). When we analysed how WNV tolerance changed over the infectious period, we found that it varied with days post-exposure (dpe × ALAN × WNV titre: F3,83 = 3.1, p = 0.030). This three-way interaction was driven by distinct WNV × ALAN effects on 6 dpe (β = 1.3 ± 0.60, t = 2.1, p = 0.041; figure 1c): at this time, only some ALAN-exposed birds (approx. 50%) maintained WNV titres above the transmission threshold; no control birds were infectious on day 6. We found no effect of ALAN on survival of WNV infection post-exposure (, p = 0.610; figure 1d); about 60% of birds in each group survived to 6 dpe. We confirmed that no collinearity existed among these three variables (ALAN, viraemia and body mass) using variance inflation factors and Eigenvalue condition indices (electronic supplementary material, text).

To evaluate the epidemiological implications of the above effects, we compared the relative change in outbreak potential in the presence and absence of ALAN by evaluating the pathogen basic reproductive number, R0, based on a simple single host, single vector model of WNV transmission [25]. We conservatively assumed that ALAN effects on house sparrows arise solely via extension of the infectious period; additional parameter values relating to demographic and transmission processes were estimated from the literature (electronic supplementary material, text). Under these conditions, ALAN effects on host infectiousness increased R0 from 8.95 to 12.66. In other words, assuming no prior exposure of hosts to WNV (i.e. no pre-existing immunity in the bird population) and no other effects of ALAN on house sparrow hosts or Culex vectors, ALAN would increase R0 for WNV by 41%.

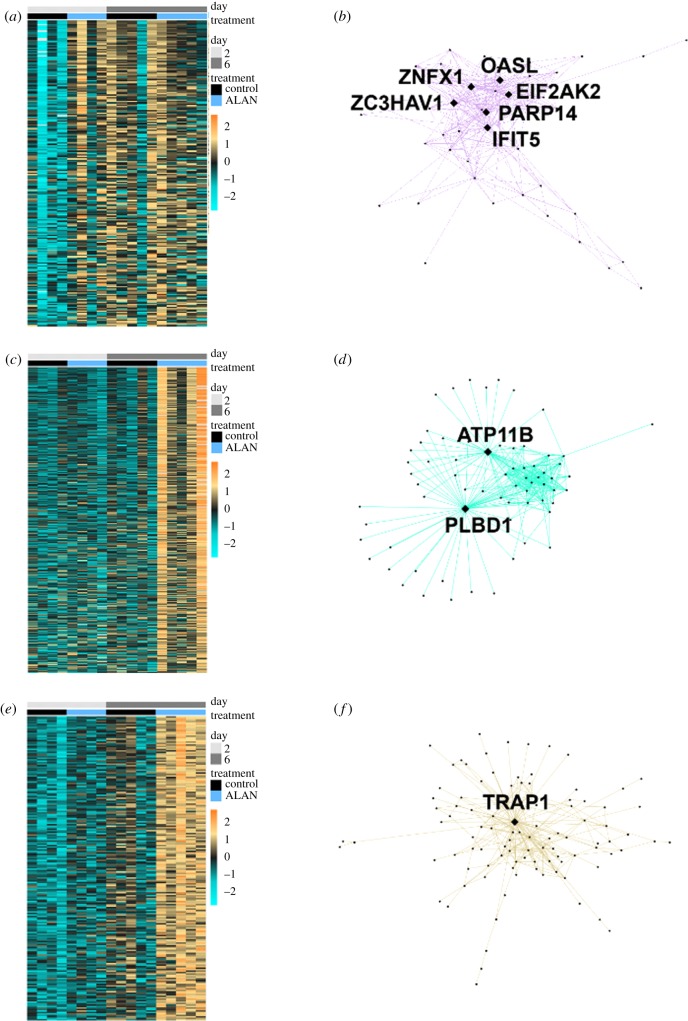

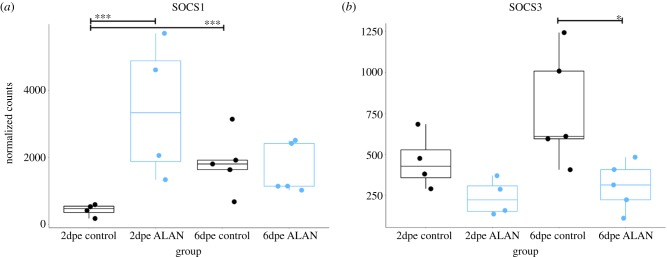

To implicate physiological mechanisms mediating ALAN effects on WNV competence, we conducted RNA-seq on whole blood samples at 2 and 6 dpe. WGCNA [43] identified 22 modules of co-regulated genes. One module (purple; figure 2a,b) included genes associated with innate immunity and were relatively increased in abundance in 2 dpe ALAN individuals (r = −0.66, p = 0.003; [44]). OASL, a gene linked to WNV resistance in both birds [43] and mammals [44,45], acted as hub (i.e. the most highly connected gene) within this module (figure 2b). Suppressor of cytokine signalling 1 (SOCS1), responsible for suppressing IFN-gamma (anti-viral) activity, was also assigned to the purple module and transcript levels increased in day 2-ALAN individuals (figure 3a), an outcome that may facilitate WNV dissemination through the host body [46–48]. Conversely, transcript levels of SOCS3, which also suppresses cytokine signalling, were decreased in ALAN-exposed individuals at 6 dpe (figure 3b). Two other modules revealed strong effects of ALAN treatment on the blood transcriptome, particularly at 6 dpe (turquoise module r = 0.84, p = 1.000 × 10−5], figure 2c,d; tan module [r = 0.84, p = 1.000 × 10−5], figure 2e,f). In one module, both PLBD1 and ATP11B (figure 2d) were hubs [49,50]. PLBD1 is expressed during severe infection in malaria patients [51]. Similarly, ATP11B is expressed in individuals experiencing innate immune hyperactivation [52]. In the other module, TRAP1 (i.e. Heat Shock Protein [HSP] 75) was a hub (figure 2f); TRAP1 inhibits cellular apoptosis by reducing reactive oxygen species [50,51]. Altogether, these results demonstrate that ALAN alters various components of the immune system [53,54].

Figure 2.

WGCNA results for significantly enriched WNV immune defense modules. (a) Heatmap of eigengene expression for purple module (235 genes), showing downregulation in d2 control birds. Columns are organized by day and treatment; each row represents a module gene and row colours correspond to relative expression levels, where orange represents upregulation and blue represents downregulation. (b) Visant network of the most interconnected genes in the purple module (greater than 28 connections). Each dot represents a gene and diamonds highlight hub genes. (c) Heatmap of eigengene expression for turquoise module (3274 genes), showing upregulation in d6 ALAN birds. Columns are organized by day and treatment, each row represents a module gene and row colours correspond to relative expression levels, where orange represents upregulation and blue represents downregulation. (d) Visant network of the most interconnected genes in the turquoise module (greater than 44 connections). Each dot represents a gene and diamonds highlight hub genes. (e) Heatmap of eigengene expression for tan module (206 genes), showing upregulation in d6 ALAN birds. Columns are organized by day and treatment, each row represents a module gene and row colours correspond to relative expression levels, where orange represents upregulation and blue represents downregulation. (f) Visant network of the most interconnected genes in the tan module (greater than 60 connections). Each dot represents a gene and diamonds highlight hub genes. (Online version in colour.)

Figure 3.

Normalized counts for (a) SOCS1 and (b) SOCS3 across treatment groups. Each dot represents a sample. Black dots and boxplots correspond to control and blue dot and boxplots correspond to ALAN. Significance bars indicate ***p < 0.001 and *p < 0.05. (Online version in colour.)

4. Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that ALAN extended the infectious-to-vector window for a zoonotic pathogen in a wild reservoir species. Ecologically, this effect could enhance transmission risk, as suggested by changes in R0 when only this parameter (duration of infection) was allowed to vary with light pollution. Although this approach is unarguably a great simplification of the true effects of ALAN in nature, this result should instigate additional theoretical and empirical studies of ALAN and infectious disease. At the molecular level, transcriptomic data suggest that ALAN-exposed birds were less effective at tolerating infection on day 6 post-exposure, probably from a combination of pathogen-induced damage or immunopathology, although neither of these were directly measured [49,50]. The mechanism underlying body mass gain in control birds during WNV infection is not well understood, but not unprecedented [23]. Many of the birds exposed to ALAN with significant loss of body mass on day 6 died shortly thereafter; this may be why the group average on day 10 reflects a ‘catching up’ of body mass of individuals who survived the studied course of infection. Much is still unknown about body mass regulation during viral infections, so we emphasize the need to further investigate relationships between pathogen-induced or collateral damage and body mass in passerines. The higher abundance of gene transcripts of typical WNV anti-viral response genes earlier in ALAN-exposed than control birds also suggests that immune responses were generally dysregulated. These differences could have contributed to the loss of body mass in ALAN-exposed birds, as there are significant energetic costs involved in mounting immune responses, but direct investigations are necessary [22,41]. Regardless of the mechanism, ALAN did not cause greater WNV-induced mortality, a result that could enable infectious birds to transmit WNV to vectors for longer than in non-polluted areas.

Whereas anti-viral immune defences were bolstered earlier, ALAN birds remained infectious for longer than controls, which prompts questions regarding the mechanisms that allow the high viral burden to persist. The dysregulation of the TRAP1 network indicates that inhibition of apoptosis may have been important [50,51]. Additionally, SOCS genes, which assist in the negative feedback of immune mechanisms via the JAK-STAT signalling pathway, might have attenuated cytokine secretion and thus enabled WNV to disseminate more easily. ALAN-exposed individuals upregulated SOCS1 on day 2 post-WNV exposure and downregulated SOCS3 on day 6 post-WNV exposure. Previous studies have found that upregulation of SOCS during WNV infection increases neuroinvasive capacity [46]. SOCS has also been proposed as a mechanism by which flaviviruses, including WNV, actively evade host defences [46]. It is likely that high viral titres persisted as a result of a combination of these and other mechanisms [15].

Prior studies on laboratory rodents found that individuals exposed to various forms of light at night had exaggerated immune responses, many with the capacity to induce collateral damage [4]. Although the exact mechanisms by which ALAN altered immune defences here is obscure, other hormones (i.e. melatonin) could play a role [9]. Our study ruled out corticosterone as a factor, despite other evidence in birds that ALAN alters the regulation of avian physiology via stress-response pathways [16,55]. Because melatonin enhances viral resistance and attenuates cellular and tissue damage by acting as an antioxidant and free radical scavenger, ALAN-induced suppression may contribute to the increased viral titre observed in this study [9,56]. Alternatively, incoordination of biological rhythms may also have contributed to the effects we observed. Most organisms evolved to use photoperiod to synchronize endogenous circadian rhythms with the environment. Indeed, 10% of the mammalian genome shows intrinsic circadian oscillations, including immune parameters such as Toll-like receptor expression and neutrophil activity [57]. Shifting the time at which individuals are exposed to WNV (i.e. from crepuscular to night-time periods) may also affect infection outcomes, as other studies have found oscillations in pathogen defences that impact the likelihood that viral dissemination occurs [58,59]. This issue is worthy of future study. Lymph nodes, which also influence viral dissemination, and the spleen, which is a key site of WNV replication, also display circadian patterns of gene expression [60]. Peritoneal macrophages involved in inflammation upregulate the secretion of cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-6, at different points during the 24-hour period. ALAN cues that contradict zeitgeber time may mismatch circadian rhythms of hosts to their environments and hence induce upregulation of certain anti-viral defences at inappropriate times.

We must acknowledge that studies such as ours, which are conducted in captivity, have some limits and should be cautiously extrapolated to the natural world. For example, the gain of body mass during the course of infection may not occur in nature as resources typically are not as accessible [61]. Furthermore, mortality could differ for ALAN-exposed birds if morbidity decreased survival probability via predation risk [62]. Ultimately, though, experimental WNV infections will never be realized in nature, so we advocate for additional work like ours, with study elements directed at emulating natural conditions (e.g. naturalistic food availability), which will be useful to the parametrization of epidemiological models [63].

Our results also should motivate further investigation of mechanisms whereby ALAN affects epidemic risk. Indeed, light pollution might alter other drivers of R0 such as vector and host diversity and the nature and timing of their interactions (i.e. over days and seasons [60]). Most WNV vectors, for instance, take blood meals at dusk and dawn [64]; with ALAN, the blood-meal feeding window might be extended, or vectors might arouse too early to find a blood meal [65]. Mosquito density also tends to be lower in urban than rural environments; however, urban heat islands make ideal breeding habitat for many species of vectors [66,67]. More work must determine which vector species thrive in light-polluted environments and how vector community composition affects local disease dynamics [65]. Incoordination of the immune system has also been noted in laboratory rodents and could result in increased susceptibility at time of exposure, thus increasing an important parameter in outbreak potential involving the likelihood that a host develops infection upon mosquito bite (i.e. exposure [4,25]). The pineal-derived hormone mentioned above, melatonin, also coordinates such circadian behaviours which could have complex effects on WNV dynamics, particularly as vectors also rely on melatonin for temporal coordination of behaviours [68].

As we further explore ALAN effects on infectious disease risk, it will be important to study whether and how lighting spectra can be adjusted to mitigate risk. Motion-activated or directed light sources can be substituted for current illumination practices, and lighting overall could also be reduced when alterations would have the greatest positive impacts on wildlife (i.e. migrations, breeding seasons). The International Dark-Sky Association has led efforts to eliminate lighting in tall urban buildings during avian migrations to reduce extensive window strikes that occur during critical migratory periods [2]. An analogous example to curtail vectored-disease transmission in the southeastern US would be to reduce the lighting of vulnerable areas during the height of arbovirus transmission season (e.g. late autumn [69]). Additional mitigation opportunities likely reside in the advent of new technologies detectable by human, but less so wildlife, vision (e.g. high-wavelength (red) wavelengths versus the broad-spectrum options typically used [64]).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Erik Hofmeister for sharing the West Nile virus NY'99 strain and members of the Martin Lab.

Ethics

All procedures and protocols were approved by and performed according to IACUC (no. 2716) and USF Biosafety (no. 1323).

Data accessibility

All data available from the Dryd Digitial Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.7v72n64 [70].

Authors' contributions

M.E.K. contributed to conceptualization, data curation, methodology, investigation, project administration and writing; D.J.N. contributed to data curation, methodology, formal analysis and writing; J.M.M. contributed to data curation, project administration and investigation; R.J.H. contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis, visualization and writing original draft; J.G. contributed to data curation and formal analysis; J.O. contributed to data curation and formal analysis; D.S. contributed to writing and revising the introduction, methods and discussion sections of the manuscript; R.H.Y.J. contributed to formal analysis; T.R.U. contributed to conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, resources and supervision; C.N.B. contributed to data curation, methodology, formal analysis, writing and supervision; L.B.M. contributed to conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision and writing original draft.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

We recognize NSF 1257773 for funding.

References

- 1.Leu M, Hanser S, Knick S. 2008. The human footprint in the West: a large-scale analysis of anthropogenic impacts. Ecol. Appl. 18, 1119–1139. ( 10.1890/07-0480.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.IDA. 2009. International Dark-Sky Association's practical guide 1: introduction to light pollution. Tucson, AZ: IDA.

- 3.Falchi F, Cinzano P, Duriscoe D, Kyba CC, Elvidge CD, Baugh K, Portnov BA, Rybnikova NA, Furgoni R. et al. 2016. The new world atlas of artificial night sky brightness. Sci Adv. 2, e1600377 ( 10.1126/sciadv.1600377) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Navara KJ, Nelson RJ. 2007. The dark side of light at night: physiological, epidemiological, and ecological consequences. J. Pineal Res. 43, 215–224. ( 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00473.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thapan K, Arendt J, Skene DJ. 2001. An action spectrum for melatonin suppression: evidence for a novel non-rod, non-cone photoreceptor system in humans. J. Physiol. 535, 261–267. ( 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00261.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pauley SM. 2004. Lighting for the human circadian clock: recent research indicates that lighting has become a public health issue. Med. Hypotheses 63, 588–596. ( 10.1016/j.mehy.2004.03.020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dominoni DM. 2015. The effects of light pollution on biological rhythms of birds: an integrated, mechanistic perspective. J. Ornithol. 156, 409–418. ( 10.1007/s10336-015-1196-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Witherington BE, Martin ER. 2003. Understanding, assessing, and resolving light-pollution problems on sea turtle nesting beaches. Tequesta, FL: Florida Marine Research Institute. See http://aquaticcommons.org/115/1/TR2_c.pdf (accessed 30 May 2017).

- 9.Hastings MH, Herbert J, Martensz ND, Roberts AC. 1985. Annual reproductive rhythms in mammals: mechanisms of light synchronization. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 453, 182–204. ( 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1985.tb11810.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schibler U. 2005. The daily rhythms of genes, cells and organs. EMBO Rep. 6, S9–S13. ( 10.1038/sj.embor.7400424) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bedrosian TA, Fonken LK, Walton JC, Nelson RJ. 2011. Chronic exposure to dim light at night suppresses immune responses in Siberian hamsters. Biol. Lett. 7, 468–471. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2010.1108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barron D, Gervasi S, Pruitt J, Martin L. 2015. Behavioral competence: how host behaviors can interact to influence parasite transmission risk. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 6, 35–40. ( 10.1016/j.cobeha.2015.08.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gervasi SS, Civitello DJ, Kilvitis HJ, Martin LB. 2015. The context of host competence: a role for plasticity in host–parasite dynamics. Trends Parasitol. 31, 419–425. ( 10.1016/j.pt.2015.05.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paull SH, Song S, McClure KM, Sackett LC, Kilpatrick AM, Johnson PT. 2012. From superspreaders to disease hotspots: linking transmission across hosts and space. Front. Ecol. Environ. 10, 75–82. ( 10.1890/110111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin LB, Burgan SC, Adelman JS, Gervasi SS. 2016. Host competence: an organismal trait to integrate immunology and epidemiology. Integr. Comp. Biol. 56, 1225–1237. ( 10.1093/icb/icw064) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ouyang JQ, de Jong M, Hau M, Visser ME, van Grunsven RH, Spoelstra K. 2015. Stressful colours: corticosterone concentrations in a free-living songbird vary with the spectral composition of experimental illumination. Biol. Lett. 11, 13–20. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2015.0517) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sapolsky RM, Romero LM, Munck AU. 2000. How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions. Endocr Rev. 279, 2363–2368. ( 10.1210/er.21.1.55) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chamberlain DE, Toms MP, Cleary-McHarg R, Banks AN. 2007. House sparrow (Passer domesticus) habitat use in urbanized landscapes. J. Ornithol. 148, 453–462. ( 10.1007/s10336-007-0165-x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Komar N. 2003. West Nile virus: epidemiology and ecology in North America. Adv. Virus Res. 951, 84–93. ( 10.1016/S0065-3527(03)61005-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017. Preliminary maps & data for 2016. See https://www.cdc.gov/westnile/statsmaps/preliminarymapsdata/index.html (accessed 30 March 2017).

- 21.Marra P, et al. 2004. West Nile virus and wildlife. Bioscience 54, 393–402. ( 10.1641/0006-3568(2004)054[0393:WNVAW]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonneaud C, Balenger SL, Hill GE, Russell AF. 2012. Experimental evidence for distinct costs of pathogenesis and immunity against a natural pathogen in a wild bird. Mol. Ecol. 21, 4787–4796. ( 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05736.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gervasi SS, Burgan SC, Hofmeister E, Unnasch TR, Martin LB. 2017. Stress hormones predict a host superspreader phenotype in the West Nile virus system. Proc. R. Soc. B 284, 20171090 ( 10.1098/rspb.2017.1090) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adelman JS, Moyers SC, Farine DR, Hawley DM. 2015. Feeder use predicts both acquisition and transmission of a contagious pathogen in a North American songbird. Proc. R. Soc. B 282, 20151429 ( 10.1098/rspb.2015.1429) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wonham MJ, De-Camino-Beck T, Lewis MA. 2004. An epidemiological model for West Nile virus: invasion analysis and control applications. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 271, 501–507. ( 10.1098/rspb.2003.2608) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.David MR, Ribeiro GS, de Freitas RM. 2012. Bionomics of Culex quinquefasciatus within urban areas of Rio de Janeiro, Southeastern Brazil. Rev. Saude Publica 46, 858–865. ( 10.1590/S0034-89102012000500013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Louder MIM, Hauber ME, Balakrishnan CN. 2018. Early social experience alters transcriptomic responses to species-specific song stimuli in female songbirds. Behav. Brain Res. 347, 69–76. ( 10.1016/j.bbr.2018.02.034) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin M. 2011. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 17, 10–12. ( 10.14806/ej.17.1.200) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warren WC, et al. 2010. The genome of a songbird. Nature 464, 757 ( 10.1038/nature08819) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR. 2013. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21. ( 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. 2015. HTSeq-A Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–169. ( 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. 2014. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 ( 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eden E, Navon R, Steinfeld I, Lipson D, Yakhini Z. 2009. GOrilla: a tool for discovery and visualization of enriched GO terms in ranked gene lists. BMC Bioinf. 10, 48 ( 10.1186/1471-2105-10-48) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zerbino DR, et al. 2018. Ensembl 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D754–D761. ( 10.1093/nar/gkx1098) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kinsella RJ, et al. 2011. Ensembl BioMarts: a hub for data retrieval across taxonomic space. Database 2011, bar030 ( 10.1093/database/bar030) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shoemaker JE, Lopes TJS, Ghosh S, Matsuoka Y, Kawaoka Y, Kitano H. 2012. CTen: a web-based platform for identifying enriched cell types from heterogeneous microarray data. BMC Genomics 13, 460 ( 10.1186/1471-2164-13-460) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Langfelder P, Horvath S. 2008. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinf. 9, 559 ( 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turell MJ, O'Guinn M, Oliver J. 2000. Potential for New York mosquitoes to transmit West Nile virus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 62, 3 ( 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.413) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gervasi SS, Burkett-Cadena N, Burgan SC, Schrey AW, Hassan HK, Unnasch TR, Martin LB. 2016. Host stress hormones alter vector feeding preferences, success, and productivity. Proc. R. Soc. B 283, 20161278 ( 10.1098/rspb.2016.1278) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liebl AL, Shimizu T, Martin LB. 2013. Covariation among glucocorticoid regulatory elements varies seasonally in house sparrows. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 183, 32–37. ( 10.1016/j.ygcen.2012.11.021) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Råberg L, Sim D, Read AF. 2007. Disentangling genetic variation for resistance and tolerance to infectious diseases in animals. Science 318, 812 LP–814 LP. ( 10.1126/science.1148526) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coon CAC, Warne RW, Martin LB. 2011. Acute-phase responses vary with pathogen identity in house sparrows (Passer domesticus). AJP Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 300, R1418–R1425. ( 10.1152/ajpregu.00187.2010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tag-El-Din-Hassan HT, Sasaki N, Moritoh K, Torigoe D, Maeda A, Agui T. 2012. The chicken 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase A inhibits the replication of West Nile Virus. Jpn. J. Vet. Res. 60, 95–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mashimo T, Lucas M, Simon-Chazottes D, Frenkiel MP, Montagutelli X, Ceccaldi PE, Deubel V, Guénet JL, Desprès P. 2002. A nonsense mutation in the gene encoding 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase/L1 isoform is associated with West Nile virus susceptibility in laboratory mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 11 311–11 316. ( 10.1073/pnas.172195399) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perelygin AA, Scherbik SV, Zhulin IB, Stockman BM, Li Y, Brinton MA. 2002. Positional cloning of the murine flavivirus resistance gene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 9322–9327. ( 10.1073/pnas.142287799) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mansfield KL, Johnson N, Cosby SL, Solomon T, Fooks AR. 2010. Transcriptional upregulation of SOCS 1 and suppressors of cytokine signaling 3 mRNA in the absence of suppressors of cytokine signaling 2 mRNA after infection with West Nile virus or tick-borne encephalitis virus. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 10, 649–653. ( 10.1089/vbz.2009.0259) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guo J-T, Hayashi J, Seeger C. 2005. West Nile virus inhibits the signal transduction pathway of alpha interferon. J. Virol. 79, 1343–1350. ( 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1343-1350.2005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ma DY, Suthar MS. 2015. Mechanisms of innate immune evasion in re-emerging RNA viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 12, 26–37. ( 10.1016/j.coviro.2015.02.005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chovatiya R, Medzhitov R. 2014. Stress, inflammation, and defense of homeostasis. Mol. Cell 54, 281–288. ( 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.030) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guardado P, Olivera A, Rusch HL, Roy M, Martin C, Lejbman N, Lee H, Gill JM. 2016. Altered gene expression of the innate immune, neuroendocrine, and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) systems is associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in military personnel. J. Anxiety Disord. 38, 9–20. ( 10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.12.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sobota RS, et al. 2016. Expression of complement and toll-like receptor pathway genes is associated with malaria severity in Mali: a pilot case control study. Malar. J. 15, 150 ( 10.1186/s12936-016-1189-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu WC.2013. Sepsis is a syndrome with hyperactivity of TH17-like innate immunity and hypoactivity of adaptive immunity. arXiv Prepr (http://arxiv.org/abs/1311.4747. )

- 53.Newhouse DJ, Hofmeister EK, Balakrishnan CN. 2017. Transcriptional response to West Nile virus infection in the zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata). R. Soc. open sci. 4, 170296 ( 10.1098/rsos.170296) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yoshimura T, Suzuki Y, Makino E, Suzuki T, Kuroiwa A, Matsuda Y, Namikawa T, Ebihara S. 2000. Molecular analysis of avian circadian clock genes. Mol. Brain Res. 78, 207–215. ( 10.1016/S0169-328X(00)00091-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ouyang JQ, de Jong M, van Grunsven RH, Matson KD, Haussmann MF, Meerlo P, Visser ME, Spoelstra K. 2017. Restless roosts: light pollution affects behavior, sleep, and physiology in a free-living songbird. Glob. Chang. Biol. 23, 4987–4994. ( 10.1111/gcb.13756) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Valero N, Mosquera J, Alcocer S, Bonilla E, Salazar J, Alvarez-Mon M. 2015. Melatonin, minocycline and ascorbic acid reduce oxidative stress and viral titers and increase survival rate in experimental Venezuelan equine encephalitis. Brain Res. 1622, 368–376. ( 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.06.034) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scheiermann C, Kunisaki Y, Frenette PS. 2013. Circadian control of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13, 190–198. ( 10.1038/nri3386) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hoyle NP, et al. 2017. Circadian actin dynamics drive rhythmic fibroblast mobilization during wound healing. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaa12774 ( 10.1126/scitranslmed.aal2774) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mideo N, Reece SE, Smith AL, Metcalf CJE. 2013. The Cinderella syndrome: why do malaria-infected cells burst at midnight? Trends Parasitol. 29, 10–16. ( 10.1016/j.pt.2012.10.006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Keller M, Mazuch J, Abraham U, Eom GD, Herzog ED, Volk H-D, Kramer A, Maier B. 2009. A circadian clock in macrophages controls inflammatory immune responses. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 21 407–21 412. ( 10.1073/pnas.0906361106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liker A, Papp Z, Bókony V, Lendvai ÁZ. 2008. Lean birds in the city: body size and condition of house sparrows along the urbanization gradient. J. Anim. Ecol. 77, 789–795. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2008.01402.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Adelman JS, Mayer C, Hawley DM. 2017. Infection reduces anti-predator behaviors in house finches. J Avian Biol. 48, 519–528. ( 10.1111/jav.01058) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Griffith SC, Crino OL, Andrew SC. 2017. Commentary: a bird in the house: the challenge of being ecologically relevant in captivity. Front. Ecol. Evol. 5, 21 ( 10.3389/fevo.2017.00021) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Apperson CS, et al. 2004. Host feeding patterns of established and potential mosquito vectors of West Nile Virus in the Eastern United States. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 4, 71–82. ( 10.1089/153036604773083013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kernbach ME, Hall RJ, Burkett-Cadena ND, Unnasch TR, Martin LB. 2018. Dim light at night: physiological effects and ecological consequences for infectious disease. Integr. Comp. Biol. 58, 995–1007. ( 10.1093/icb/icy080) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Araujo RV, et al. 2015. São Paulo urban heat islands have a higher incidence of dengue than other urban areas. Brazilian J. Infect. Dis. 19, 146–155. ( 10.1016/j.bjid.2014.10.004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ferraguti M, Martínez-de La Puente J, Roiz D, Ruiz S, Soriguer R, Figuerola J. 2016. Effects of landscape anthropization on mosquito community composition and abundance. Sci. Rep. 6, 29002 ( 10.1038/srep29002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gwinner E, Benzinger I. 1978. Synchronization of a circadian rhythm in pinealectomized European starlings by daily injections of melatonin. J. Comp. Physiol. 127, 209–213. ( 10.1007/BF01350111) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ezenwa VO, Godsey MS, King RJ, Guptill SC. 2006. Avian diversity and West Nile virus: testing associations between biodiversity and infectious disease risk. Proc. R. Soc. B 273, 109–117. ( 10.1098/rspb.2005.3284) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kernbach ME, et al. 2019. Data from: Light pollution increases West Nile virus competence of a ubiquitous passerine reservoir species Dryad Digital Repository. 273, 109–117. ( 10.5061/dryad.7v72n64) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data available from the Dryd Digitial Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.7v72n64 [70].