Abstract

Background

Statins may improve outcomes in patients with cirrhosis. We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the effect of statins on patients with cirrhosis and related complications, especially portal hypertension and variceal haemorrhage.

Methods

Studies were searched in the PubMed, Embase and Cochrane library databases up to February 2019. The outcomes of interest were associations between statin use and improvement in portal hypertension (reduction >20% of baseline or <12 mm Hg) and the risk of variceal haemorrhage. The relative risk (RR) with a 95% CI was pooled and calculated using a random effects model. Subgroup analyses were performed based on the characteristics of the studies.

Results

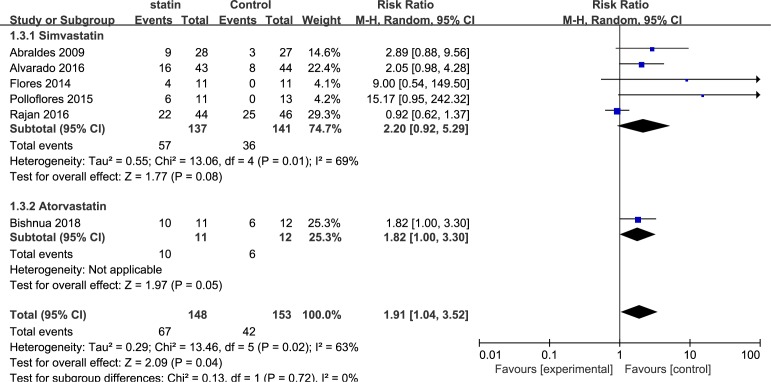

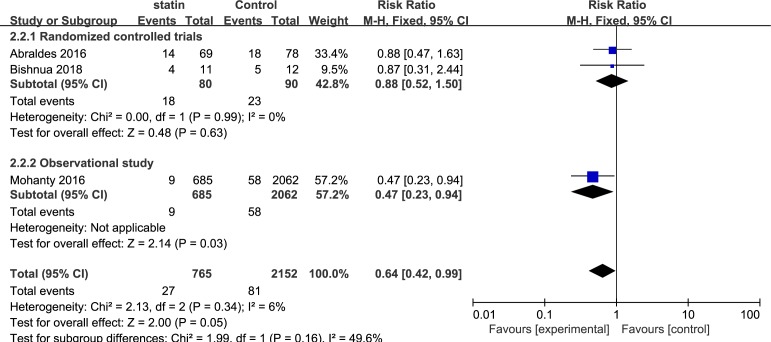

Eight studies (seven randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and one observational study) with 3195 patients were included. The pooled RR for reduction in portal hypertension was 1.91 (95% CI, 1.04 to 3.52; I2=63%) in six RCTs. On subgroup analysis of studies that used statin for 1 month, the RR was 2.01 (95% CI, 1.31 to 3.10; I2=0%); the pooled RR for studies that used statins for 3 months was 3.76 (95% CI, 0.36 to 39.77; I2=75%); the pooled RR for studies that used non-selective beta-blockers in the control group was 1.42 (95% CI, 0.82 to 2.45; I2=64%); the pooled RR for studies that used a drug that was not reported in the control group was 4.21 (95% CI, 1.52 to 11.70; I2=0%); the pooled RR for studies that used simvastatin was 2.20 (95% CI, 0.92 to 5.29; I2=69%); RR for study using atorvastatin was 1.82 (95% CI, 1.00 to 3.30). For the risk of a variceal haemorrhage, the RR based on an observational study was 0.47 (95% CI, 0.23 to 0.94); in two RCTs, the pooled RR was 0.88 (95% CI, 0.52 to 1.50; I2=0%). Overall, the summed RR was 0.64 (95% CI, 0.42 to 0.99; I2=6%).

Conclusion

Statins may improve hypertension and decrease the risk of variceal haemorrhage according to our assessment. However, further and larger RCTs are needed to confirm this conclusion.

Keywords: portal hypertension, variceal haemorrhage, cirrhotic, statins, meta-analysis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This will be the most comprehensive review of published and unpublished data of clinical effects of statins on the reduction of portal hypertension and variceal haemorrhage.

This systematic review provides strong evidence for clinicians using statins to treat portal hypertension and variceal haemorrhage.

Eligible studies screening, data extraction and quality assessment were performed by two independent reviewers to reduce the potential for reviewer bias.

Large randomised controlled trials are needed to confirm beneficial effects of statins in patients with liver diseases.

Only studies in the English language have been included in the analysis.

Introduction

Cirrhosis is increasingly prevalent worldwide, as a result of a variety of chronic liver diseases. Cirrhosis, including compensate and decompensate, was in the top eight causes of death in the USA in 2010 and led to more than 49 500 deaths.1 The median survival of patients with compensated cirrhosis is >12 years, and patients with decompensated cirrhosis exhibit a median survival of <2 years.2 Portal hypertension and oesophageal varices are common complications of cirrhosis, and these conditions develop into variceal haemorrhage, which produces a mortality of 10%–15% per episode.3 The hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) is a significant indicator of portal hypertension and varices bleeding. Reduction in HVPG indicates an improvement in portal hypertension and a decline in bleeding risk.4

Statins are widely used in clinical practice because of their exact and effective lipid-lowering effects.5 6 The use of statins in patients with liver disease has long been limited by concerns of their potential hepatotoxicity, which have been raised by anecdotal evidence of increased liver enzymes following statin use or the possible trapping of lipids in the liver.7 Some residual concern remains among primary care physicians in prescribing statins to patients with underlying liver disease because some of doctors still believe that these patients are at increased risk for hepatotoxicity.8 However, a growing interest in the potential benefits of statins in patients with liver diseases has recently emerged.7 9–12 Recent in vivo and in vitro experiments have gradually demonstrated that statins also exhibit anti-inflammatory,13 immune-modulating,14 antiproliferative15 and antioxidant16 effects as well as improved endothelial function17 and inhibit platelet aggregation18 and certain Gram-negative bacteria.19 20 These findings led to the development of statins in basic research of liver disease and laid a solid foundation for clinical practice.

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis based on the most recent studies (randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and a cohort study) to evaluate the effects of statins in patients with cirrhosis and related complications, especially portal hypertension and variceal haemorrhage.

Methods

Search strategy

PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Controlled Trial Registry and The Cochrane Library were searched up to February 2019 to identify all relevant articles on the effect of statins in liver cirrhosis and retrieve pertinent studies (online supplementary method). No language restrictions were imposed. An experienced medical librarian designed and implemented the search strategy. Electronic databases were searched using the following search terms: liver cirrhosis, ascites, portal hypertension, statin, hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitors. The detailed search strategy is available in the ‘online supplementary method’. Two reviewers (SW and CH) independently assessed the titles and abstracts of the studies that met the eligibility criteria for inclusion.

bmjopen-2019-030038supp001.pdf (149.8KB, pdf)

Data abstraction

Two reviewers (SW and CH) independently extracted the data. The following data were collected from each study: year of publication, study design, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, aetiology of cirrhosis, total number of patients in each group, primary outcome reported and Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) class and ascites. Any divergence between the reviewers was discussed with a third reviewer (XZ), and agreement was reached by consensus.

We used the Newcastle–Ottawa scale to determine the quality of the cohort studies, and the Cochrane tool was used to determine the risk of bias for RCTs.

Outcomes assessed

Our primary outcome of interest was the association between statin use and the reduction in portal hypertension. The secondary outcomes of interest were the association between statin use and variceal bleeding. Several subgroup analyses were performed based on the quality of the studies, medication time, types of drugs in the control group and types of statins. The adverse effects of statins were not included in the study due to insufficient information.

Quality of evidence

We used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) framework to evaluate the quality of the evidence.21 The GRADE approach for systematic reviews defines the quality of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of an effect or association is close to the quantity of specific interest. The following factors were considered in determining the quality of evidence: risk of bias, directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias.

Statistical analysis

The trials and patient characteristics are reported as the number of observations and proportions. The relative risk (RR) and 95% CI that achieved a target haemodynamic response in each group were pooled using the DerSimonian and Laird random effects model.22 Intertrial heterogeneity was statistically assessed using the chi-square test and is expressed as the I2 value, and I2 values >50% were reflective of substantial heterogeneity.23 A formal assessment of publication bias using the egger test was performed (online supplementary figure 1).

bmjopen-2019-030038supp002.pdf (74.8KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

This meta-analysis did not involve patients or the public.

Results

Search results

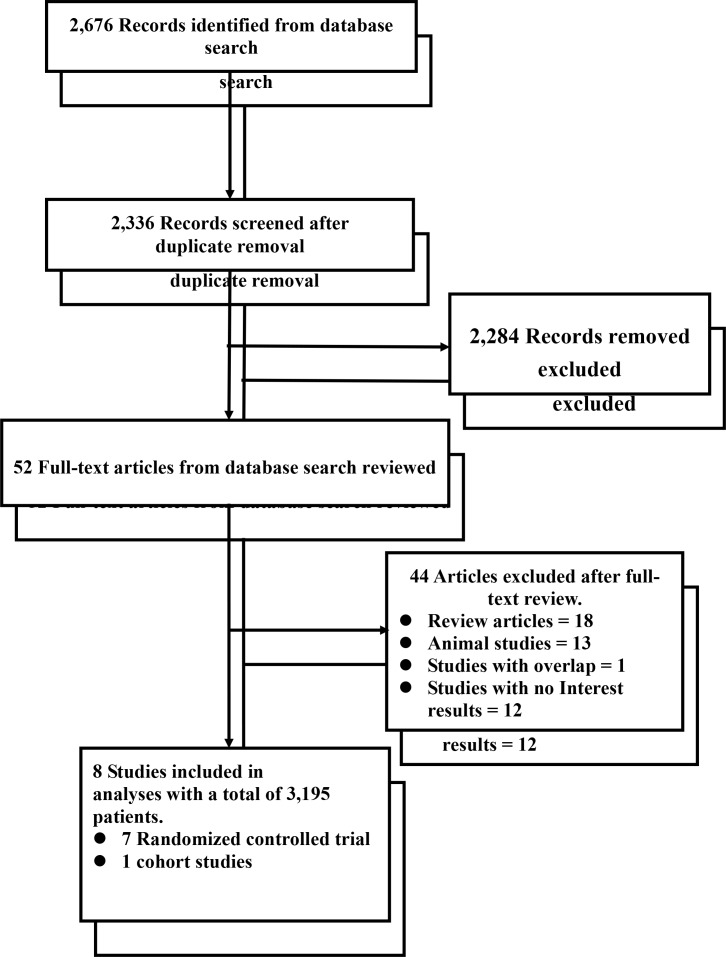

A total of 2676 potentially eligible references were retrieved in the literature search, and 2624 were excluded based on the titles and abstracts. A further 44 articles, referred to as full articles, were deemed ineligible. Twelve studies were excluded because they did not clearly report the number of patients with improved portal hypertension and variceal haemorrhage. Eight studies with a total of 3195 patients met our inclusion criteria and were included in our meta-analysis (seven RCTs and one observational study).10 24–30 Six studies included patients who exhibited the target reduction in HVPG >20% from baseline or <12 mm Hg in the statins group. Three studies included events of variceal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis. Figure 1 summarises the search strategy.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart.

Description of included studies

Table 1 shows the characteristics of these studies. These studies included 3195 liver cirrhosis patients, of whom 902 patients were exposed to statins. One study was performed exclusively in patients with HCV mono-infection, and seven studies included cirrhosis with multiple underlying aetiologies. The medication time of statins was 1 month in three studies. However, statins were used for 3 months in three studies. Six studies provided the desired data as regarded decrease in HVPG (reduction >20% or <12 mm Hg).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Study | Design | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Aetiology of cirrhosis | Groups | N | Outcomes of interest | Outcomes | |

| Statins users (n) | Non-users (n) |

||||||||

| Mohanty et al 24 | Retrospective | HCV-positive patients defined by ICD-9 codes Compensated cirrhosis |

HIV or HBV coinfection Decompensation or HCC before or within 180 days after index date No laboratory results No follow-up Died within 180 days after index date Statin users with only one prescription fill or more than 365 days between first and second fill |

HCV | Statins Nonusers |

685 2062 |

Variceal haemorrhage | Variceal haemorrhage: 9 |

58 |

| Abraldes et al 25 | RCT | Age between 18 and 75 years, positive diagnosis of cirrhosis and severe portal hypertension defined as HVPG of 12 mm Hg or greater | Pregnancy Cholestatic liver disease Severe liver failure, evaluated by the presence of a serum bilirubin level greater than 5 mg/dL, prothrombin rate less than 40% Hepatic encephalopathy grades II–IV Child-Pugh score of 12 or greater Serum creatinine level greater than 1.5 mg/dL Hepatocellular carcinoma Portal vein thrombosis |

Mixed | Statins Nonusers |

28 27 |

Reduction in portal hypertension | Reduction in portal hypertension: 9 | 3 |

| Abraldes, et al 10 | RCT | Age between 18 and 80 years Previous diagnosis of liver cirrhosis Index variceal bleeding within the previous 5–10 days Plan to start standard treatment for the prevention of variceal rebleeding In woman documented absence of pregnancy and commitment to use adequate contraception if applicable |

Pregnancy or lactation multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma or a single nodule >5 cm in diameter. Creatinine >2 mg/dL Child–Pugh score >13 points Contraindication for statins Patients with HIV infection on protease inhibitors Pretreatment with portosystemic shunt (surgical or percutaneous) Index bleeding due to gastric varices Complete portal vein thrombosis or portal vein cavernomatosis Patients previously treated with the combination of endoscopic banding ligation and NSBB (before the index episode) Patients previously treated with statins within 1 month of randomization |

Mixed | Statins Nonusers |

69 78 |

Variceal haemorrhage | Variceal haemorrhage: 14 | 18 |

| Alvarado-Tapias et al 26 | RCT | Cirrhosis, CSPH and high-risk oesophageal varices without previous bleeding | NR | Mixed | Statins Nonusers |

43 44 |

Reduction in portal hypertension | Reduction in portal hypertension: 16 | 8 |

| Bishnu et al 27 | RCT | Age: 18–60 years Cirrhosis (diagnosed clinically, radiologically or histopathologically) Portal hypertension (history of variceal bleed, ascites, splenomegaly, oesophageal varices on upper GI endoscopy or history of having undergone EVL) |

Child–Pugh–Turcott (CPT) class C. Hepatic encephalopathy grades II–IV. Hepatocellular carcinoma Portal vein thrombosis or cavernomatosis. Hepatic venous outflow tract obstruction Previous portosystemic shunt surgery Obstructive airway diseases Cardiac conduction abnormalities Peripheral vascular disease Congestive cardiac failure NYHA class II–IV Renal insufficiency (serum creatinine >2 mg/dL) Previous episodes of rhabdomyolysis Hypersensitivity to HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors Previous treatment with HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor Participation in a concurring clinical trial Pregnancy or plan to conceive during study period |

Mixed | Statins Nonusers |

11 12 |

Reduction in portal hypertension Variceal haemorrhage |

Reduction in portal hypertension: 10 Variceal haemorrhage: 4 |

6 5 |

| Flores et al 28 | RCT | Cirrhosis and portal hypertension detected using abdominal ultrasound with colour Doppler flowmetry or upper digestive endoscopy | NR | Mixed | Statins Nonusers |

11 11 |

Reduction in portal hypertension | Reduction in portal hypertension: 4 | 0 |

| Pollo-Flores et al 29 | RCT | Age 18–75 years Diagnosis of cirrhosis with portal hypertension detected using an abdominal ultrasound with colour Doppler and an upper digestive endoscopy showing gastro-oesophageal varices Both procedures were performed within the previous 6 months |

Aminotransferases levels >3 times above the upper limit of normal (ULN) Recent (within the last 6 months) or current use of simvastatin Portal vein thrombosis, contrast medium allergy Hepatocellular carcinoma or any other malignancy reducing life expectancy Renal failure (creatinine level >1.5 mg/dL) Bleeding disorder (prothrombin activity test <30% or platelet count <35 × 10 9/L) or decompensated cirrhosis characterised by severe ascites or grade II or overt encephalopathy Patients with alcoholic cirrhosis were abstinent from alcohol consumption for at least 1 year |

Mixed | Statins Nonusers |

11 13 |

Reduction in portal hypertension | Reduction in portal hypertension: 6 | 0 |

| Rajan et al 30 | RCT | Cirrhotics with varices who had never bled | NR | Mixed | Statins Nonusers |

44 46 |

Reduction in portal hypertension | Reduction in portal hypertension: 22 | 25 |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; ICD-9, International Classification of Disease–9; NR, not reported; NSBB, non-selective beta- blockers; CSPH, clinically significant portal hypertension; EVL, endoscopic variceal ligation; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; GI, gastrointestinal; RCTs, randomised controlled trials.

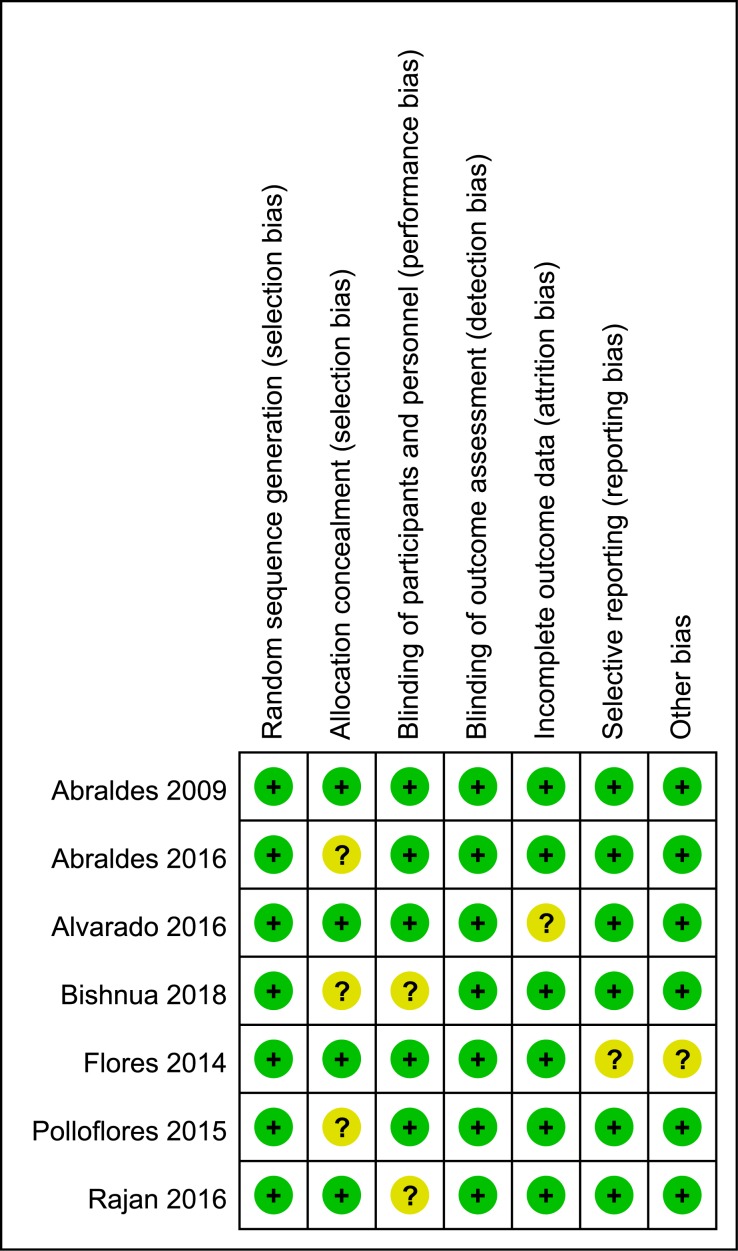

The only observational study was of high quality, as exhibited by the high Newcastle–Ottawa quality score. Table 2 summarises the methodological qualities of the observational study and RCTs. Figure 2 shows the methodological qualities of the RCTs.

Table 2.

Quality assessment of the observational studies using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

| Studies | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Quality | |||||

| Representativeness of exposed cohort | Selection of non-exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Outcome not present at start | Adjustment for primary and secondary factors | Assessment by record linkage | Long enough follow-up for outcome to occur | Adequacy of follow-up | ||

| Mohanty et al 24 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | High quality |

| Quality assessment of the randomised controlled trials using the Cochrane tool for assessing the risk of bias | |||||||

| Selection bias | Performance bias | Detection bias | Attrition bias | Reporting bias | Other bias | Quality | |

| Abraldes et al 25 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | High quality |

| Abraldes et al 25 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | High quality |

| Alvarado-Tapias et al 26 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | High quality |

| Bishnua et al 27 | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | High quality |

| Flores et al 28 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | High quality |

| Pollo-Flores et al 29 | Low risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | High quality |

| Rajan et al 30 | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | High quality |

Figure 2.

Risk of bias assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomised controlled trials.

Table 3 summarises the characteristics of the 3195 patients included in the eight studies. Statin users and nonusers were generally male because the cirrhosis incidence in females was lower than that in males. Patients were mostly categorised as CTP A and B classes, 221 of 255 (87%) in two studies. No appreciable differences in the complications of cirrhosis, such as ascites or previous variceal bleeding, were observed between the two study groups across the eight studies.

Table 3.

Characteristics of participants in the included studies

| Treatment group |

Patients, N | Age, years | Males, N | Viral/alcoholic aetiology, N |

Child–Pugh class A/B/C, N | Ascites, N |

Previous variceal bleeding, N |

|

| Mohanty et al 24 | Statins | 685 | 56 | 671 | 685/0 | NR | NR | NR |

| Nonusers | 2062 | 56 | 2021 | 2062/0 | NR | NR | NR | |

| Abraldes et al 25 | Statins | 28 | 58 | 17 | NR | 18/10/0 | 14 | 6 |

| Nonusers | 27 | 56 | 21 | NR | 16/8/3 | 16 | 9 | |

| Abraldes et al 10 | Statins | 69 | 57 | 45 | 20/49 | 15/68/17 | 15 | NR |

| Nonusers | 78 | 57 | 53 | 19/55 | 24/62/14 | 16 | NR | |

| Alvarado-Tapias et al 26 | Statins | 43 | 56 | 31 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Nonusers | 44 | 54 | 35 | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Bishnu et al 27 | Statins | 11 | 44 | 9 | 0/4 | NR | 5 | 6 |

| Nonusers | 12 | 47 | 12 | 1/6 | NR | 6 | 5 | |

| Flores et al 28 | Statins | 11 | 46 | 23 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Nonusers | 11 | 43 | 30 | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Pollo-Flores et al 29 | Statins | 11 | 57 | 6 | NR | NR | 2 | 5 |

| Nonusers | 13 | 59 | 7 | NR | NR | 3 | 3 | |

| Rajan et al 30 | Statins | 44 | 51 | 30 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Nonusers | 46 | 53 | 35 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

NR, not reported.

Outcome evaluation

Improvement in portal hypertension

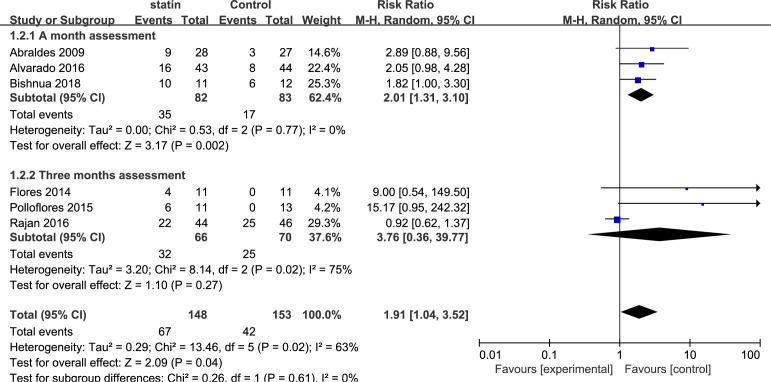

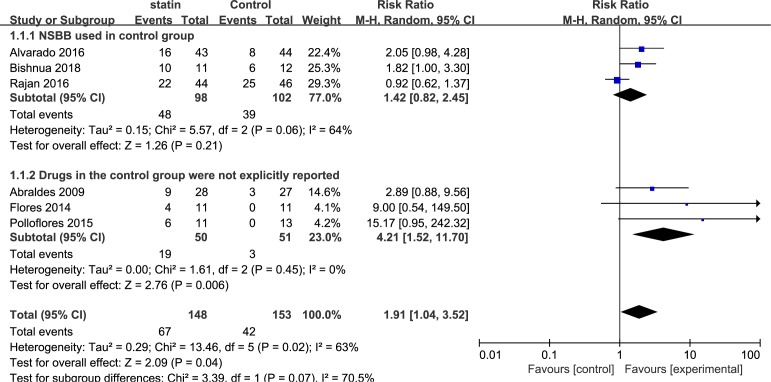

Six studies including 301 patients evaluated the improvement in portal hypertension in cirrhosis. Overall, a decrease in HVPG (>20% from baseline or <12 mm Hg) was achieved with statins in 57 of 135 evaluable patients compared with 36 of 141 patients in the control group (RR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.04 to 3.52; I2=63%). Three subgroup analyses were performed, based on the medication time, types of drug used in the control group and types of statins. Subgroup analysis of the medication time of statins included three studies that used statins for 1 month (RR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.31 to 3.10; I2=0%) and three studies that used statins for 3 months (RR, 3.76; 95% CI, 0.36 to 39.77; I2=75%) (figure 3). The second subgroup analysis was based on the types of drugs used in the control group, including non-selective beta-blockers (NSBB) and not explicitly reported drugs. The pooled RR for NSBB users was 1.42 (95% CI, 0.82 to 2.45; I2=64%), and the pooled RR for the not explicitly reported drugs was 4.21 (95% CI, 1.52 to 11.70; I2=0%) (figure 4). The third subgroup analysis was based on the types of statins. Five studies used simvastatin (RR, 2.20; 95% CI, 0.92 to 5.29; I2=69%), and one study used atorvastatin (RR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.00 to 3.30) (figure 5).

Figure 3.

Forest plot using the Mantel-Haenszel (M-H) analysis method to evaluate the role of statins in the reduction of portal hypertension using a subgroup analysis based on medication time of statins.

Figure 4.

Forest plot using the Mantel-Haenszel (M-H) analysis method to evaluate the role of statins in the reduction of portal hypertension using subgroup analysis based on the types of drugs in the control group. NSBB, non-selective beta-blockers.

Figure 5.

Forest plot using the Mantel-Haenszel (M-H) analysis method to evaluate the role of statins in the reduction of portal hypertension using subgroup analysis based on types of statins.

There was moderate persuasion supporting the use of statins associated with an improvement in portal hypertension based on the RCTs. However, the result was limited by the study size (109 events in 301 patients).

Risk of variceal haemorrhage

Three studies including 3025 patients evaluated the association between statin use and the occurrence of variceal bleeding. Overall, 27 events occurred in 765 statin users, and 81 events were reported in 2152 nonusers. A subgroup analysis was performed based on the type of trial. Overall, the pooled RR for the risk of variceal haemorrhage was 0.64 (95% CI, 0.42 to 0.99; I2=6%). The RR for the only one observational study was 0.47 (95% CI, 0.23 to 0.94). The pooled RR for the two RCTs studies was 0.88 (95% CI, 0.52 to 1.50; I2=0%) (figure 6).

Figure 6.

Forest plot using the Mantel-Haenszel (M-H) analysis method to evaluate the role of statins in the reduction of the risk of variceal haemorrhage using subgroup analysis based on types of statins.

Discussion

This meta-analysis demonstrated the possible roles of statin use in patients with cirrhosis against the development of portal hypertension and the occurrence of variceal haemorrhage in eight studies (seven RCTs and one cohort study). The availability of statins was proven to lead to the decrease in portal hypertension and variceal bleeding across all trials. The summary RR between the numbers of HVPG reductions achieved in statin users and nonusers was 1.91 (95% CI, 1.04 to 3.52; I2=63%) in favour of statins. We performed three subgroup analyses because of the substantial heterogeneity. The subgroup analysis based on the medication time of statin use supported the improvement in portal pressure at the 1-month assessment (RR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.31 to 3.10; I2=0%). However, this effect was not statistically significant at the 3-month assessment (RR, 3.76; 95% CI, 0.36 to 39.77; I2=75%). These results suggest that the effects of statins are not dose-dependent and lead to strong curative effects in patients who used statins for 1 month compared with patients with a longer duration of use. Several possible mechanisms may explain the biological plausibility of our findings. The hepatotoxicity of statins occurs via regulation of the P450 cytochrome in immune-mediated liver damage, which activates apoptosis and T cell-induced liver injury.31 32 Previous clinical research33–36 confirmed these observations, which offset the benefits of statins over a longer treatment period. No considerable differences were observed in subgroup analyses for the use of NSBB in the control group (RR, 1.42; 95% CI, 0.82 to 2.45; I2=64%). We presume that improvements of portal hypertension by NSBB is the underlying mechanism. NSBB is clinically used to treat portal hypertension because of its efficacy in decreasing HVPG and variceal haemorrhage.37–40 Therefore, the use of NSBB in the control group may lead to no significant difference between the statin user and nonuser groups. Different types of statins exhibit inconsistent pharmacological actions. Therefore, patients were stratified by the statin varieties. The pooled RR in a subset of patients who received simvastatin was 2.20 (95% CI, 0.92 to 5.29; I2=69%), which indicates no improvement. Atorvastatin users exhibited a decrease in portal pressure (RR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.00 to 3.30). High-quality evidence was included, but discrepancies, such as the medication time, may have led to imprecision.

Events of variceal haemorrhage were satisfactorily reported in three studies. The effect of statins on variceal bleeding as a common cause of death in patients with portal hypertension was also investigated. The pooled RR was 0.64 (95% CI, 0.42 to 0.99; I2=6%). However, the reduction in the pooled RR of the risk of variceal haemorrhage failed to reach statistical significance with statin use in two RCTs (RR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.52 to 1.50; I2=0%). Notably, the only observational study confirmed the superiority of statins in lowering the risk of variceal bleeding (RR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.23 to 0.94). The characteristics of different types of experiments may be responsible for the inconsistency.

Statins have received increasing attention in clinical research in the field of various liver diseases including liver cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, fatty liver disease, viral hepatitis and other related liver diseases, in recent years.6 Studies have confirmed that statins are safe and effective for some patients with these liver diseases.41 A population-based study9 evaluated the effects of statins on reducing decompensation, mortality and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in HBV, HCV and alcohol-related cirrhosis. This study demonstrated that statins reduced decompensation (p<0.0001), mortality (p<0.0001) and the risk of HCC (p=0.009) in patients with cirrhosis, and this correlation was dose-dependent. The risk of decompensation in patients with cirrhosis caused by chronic HBV (RR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.25 to 0.62) or HCV infection (RR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.29 to 0.93) was lower in patients taking statins. The effect of statins on reducing the risk of cirrhosis decompensation was statistically significant in alcohol cirrhotic patients (RR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.45 to 1.07). In general, the use of statins reduced the decompensation rate of HBV, HCV and alcohol-related cirrhosis. Two recent studies42 43 demonstrated that statins were safe in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and exhibited beneficial effects decreasing steatosis and fibrosis and preventing disease progression. Multiple previous studies demonstrated the benefit of statins on liver systems. A randomised trial of patients with cirrhosis and significant portal hypertension observed that the nitric oxide levels in hepatic venous blood, as a key vasodilator mediating the hepatic vascular resistance,44–46 were increased in the statin group compared with those in the control group. A decrease in portal hypertension was also observed in patients who received statins.47 The study by Marrone et al 48 has also confirmed that the use of statins in cirrhotic animals can reduce liver fibrosis and prevent further deterioration of cirrhosis by inhibiting the activation of hepatic stellate cell. This may also be a potential mechanism for the efficacy of statins.

More research groups have begun to support the use of statin in some patients with chronic liver disease or cirrhosis based on these studies.49 50 Some researchers believe that statins may also be able to be used as an adjuvant therapy in any chronic liver disease patients with indications for statin use to prevent decompensation or delay the progression of patients with decompensated cirrhosis.51 However, this information was derived from retrospective cohort studies, and prospective studies are needed to confirm these beneficial effects.

This meta-analysis evaluated the role of statins in patients with cirrhosis as a decline in portal pressure and risk of variceal haemorrhage. We performed a comprehensive literature search that met the well-defined inclusion criteria. Eight studies were included, primarily consisting of RCTs. These studies were high-quality studies as graded by the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias or the Newcastle–Ottawa scale. Several subgroup analyses were completed based on the characteristics of the studies to further ascertain the precision of results.

However, several limitations exist in our meta-analysis. In some of the results, we have a large heterogeneity, which may be due to the inconsistency of the inclusion and exclusion criteria we included in the study. In addition, patients with various aetiologies of cirrhosis were not researched separately because of insufficient information, which may explain the substantial heterogeneity. So we performed a subgroup analysis to try to eliminate this difference, significantly reducing heterogeneity in some subgroup analyses. Seven RCTs were included, but the number of patients enrolled was relatively fewer in the RCTs (471 patients). Although individual studies adjusted for various confounders (eg, age, sex, CTP score and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score), some confounding factors cannot be fully adjusted. These situations may have affected the precision and credibility of our estimates. In two studies, the 0-event counts in the control group may be due to the fact that the placebo used in the control group is not a drug such as NSBB that has been proven to have a reduced portal pressure, leading to a wide 95% CI. The quality assessment of the RCT suggests that the quality of the two studies is acceptable, so we have no good reason to exclude these studies. The number of patients included in some studies is insufficient, so continuity corrections is not used, which may increase the risk of bias. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, as a metabolic disease, may exhibit closer relevance with lipid-lowering drug statins. Unfortunately, no eligible NAFLD research was included.

In conclusion, our analyses based on RCTs and an observational study indicated a beneficial effect of statins on reducing portal hypertension and variceal haemorrhage. However, the assessment cannot serve as clinical guideline for the wide use of statins in cirrhosis with portal hypertension because of the limited quantity and quality of the included studies. Previous research reported the potential protective effects of statins against cirrhosis and HCC progression, and the potential benefits of statins may outweigh the theoretical risks. Notably, adverse events related to statins were rarely reported in studies. Large RCTs are required before statins are clinically used to treat patients with cirrhosis and complications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks for the economic support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Footnotes

Wan S and Huang C contributed equally.

Contributors: SW and CH contributed equally to this study. SW planned the study. SW and CH screened the literature and collected data. SW, CH and XZ conducted the meta-analysis and wrote the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 81660110), the “Gan-Po Talent 555” Project of Jiangxi Province, and the Nanchang University Graduate Innovation Special Fund Project (grant number: CX2018205).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Murray CJ, Atkinson C, Bhalla K, et al. . The state of US health, 1990-2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA 2013;310:591–608. 10.1001/jama.2013.13805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. D’Amico G, Garcia-Tsao G, Pagliaro L. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: a systematic review of 118 studies. J Hepatol 2006;44:217–31. 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. D’Amico G, Luca A. Natural history. Clinical-haemodynamic correlations. Prediction of the risk of bleeding. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol 1997;11:243–56. 10.1016/S0950-3528(97)90038-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ripoll C, Groszmann R, Garcia-Tsao G, et al. . Hepatic venous pressure gradient predicts clinical decompensation in patients with compensated cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2007;133:481–8. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sirtori CR. The pharmacology of statins. Pharmacol Res 2014;88:3–11. 10.1016/j.phrs.2014.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pose E, Trebicka J, Mookerjee RP, et al. . Statins: Old drugs as new therapy for liver diseases? J Hepatol 2019;70 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tsochatzis EA, Bosch J. Statins in cirrhosis-Ready for prime time. Hepatology 2017;66:697–9. 10.1002/hep.29277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moctezuma-Velázquez C, Abraldes JG, Montano-Loza AJ. The Use of Statins in Patients With Chronic Liver Disease and Cirrhosis. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2018;16:226–40. 10.1007/s11938-018-0180-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chang FM, Wang YP, Lang HC, et al. . Statins decrease the risk of decompensation in hepatitis B virus- and hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis: A population-based study. Hepatology 2017;66:896–907. 10.1002/hep.29172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Abraldes JG, Villanueva C, Aracil C, et al. . Addition of simvastatin to standard therapy for the prevention of variceal rebleeding does not reduce rebleeding but increases survival in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2016;150:1160–70. 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mach F, Ray KK, Wiklund O, et al. . Adverse effects of statin therapy: perception vs. the evidence - focus on glucose homeostasis, cognitive, renal and hepatic function, haemorrhagic stroke and cataract. Eur Heart J 2018;39:2526–39. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shin JY, Azoulay L, Filion KB. Statin use in patients with hepatitis c-related cirrhosis: true benefit or immortal time bias? Gastroenterology 2016;151:373 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.11.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chang CH, Hsu YM, Chen YC, et al. . Anti-inflammatory effects of hydrophilic and lipophilic statins with hyaluronic acid against LPS-induced inflammation in porcine articular chondrocytes. J Orthop Res 2014;32:557–65. 10.1002/jor.22536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kolawole EM, McLeod JJ, Ndaw V, et al. . Fluvastatin suppresses mast cell and basophil IgE Responses: genotype-dependent effects. J Immunol 2016;196:1461–70. 10.4049/jimmunol.1501932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Feldt M, Bjarnadottir O, Kimbung S, et al. . Statin-induced anti-proliferative effects via cyclin D1 and p27 in a window-of-opportunity breast cancer trial. J Transl Med 2015;13:133 10.1186/s12967-015-0486-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ramma W, Ahmed A. Therapeutic potential of statins and the induction of heme oxygenase-1 in preeclampsia. J Reprod Immunol 2014;101-102:153–60. 10.1016/j.jri.2013.12.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Oikonomou E, Siasos G, Zaromitidou M, et al. . Atorvastatin treatment improves endothelial function through endothelial progenitor cells mobilization in ischemic heart failure patients. Atherosclerosis 2015;238:159–64. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Camargo LM, França CN, Izar MC, et al. . Effects of simvastatin/ezetimibe on microparticles, endothelial progenitor cells and platelet aggregation in subjects with coronary heart disease under antiplatelet therapy. Braz J Med Biol Res 2014;47:432–7. 10.1590/1414-431X20143628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mehl A, Harthug S, Lydersen S, et al. . Prior statin use and 90-day mortality in Gram-negative and Gram-positive bloodstream infection: a prospective observational study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2015;34:609–17. 10.1007/s10096-014-2269-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. de Paula TP, Santos PC, Arifa R, et al. . Treatment with atorvastatin provides additional benefits to imipenem in a model of gram-negative pneumonia induced by Klebsiella pneumoniae in Mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018;62 10.1128/AAC.00764-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Sultan S, et al. . GRADE guidelines: 11. Making an overall rating of confidence in effect estimates for a single outcome and for all outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:151–7. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177–88. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. . Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mohanty A, Tate JP, Garcia-Tsao G. Statins are associated with a decreased risk of decompensation and death in veterans with Hepatitis C-Related Compensated Cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2016;150:430–40. 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Abraldes JG, Albillos A, Bañares R, et al. . Simvastatin lowers portal pressure in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2009;136:1651–8. 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Alvarado-Tapias E, Ardèvol A, Pavel O, et al. . Hemodynamic effects of carvedilol plus simvastatin in cirrhosis with portal hypertension and no-response to β-blockers: A double-blind randomized trial. Hepatology 2016;64:74A. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bishnu S, Ahammed SM, Sarkar A, et al. . Effects of atorvastatin on portal hemodynamics and clinical outcomes in patients with cirrhosis with portal hypertension: a proof-of-concept study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;30:54–9. 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Flores PP, Rezende GF, Cassano U, et al. . Effect of simvastatin in portal hypertension. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2014;60:1191A. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pollo-Flores P, Soldan M, Santos UC, et al. . Three months of simvastatin therapy vs. placebo for severe portal hypertension in cirrhosis: A randomized controlled trial. Dig Liver Dis 2015;47:957–63. 10.1016/j.dld.2015.07.156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rajan V, Choudhary A, Jindal A, et al. . Addition of simvastatin to carvedilol does not improve hemodynamic response in cirrhotics with varices without prior bleed: Preliminary results of an open label RCT. Hepatology 2016;64:1134A–5. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bhardwaj SS, Chalasani N. Lipid-lowering agents that cause drug-induced hepatotoxicity. Clin Liver Dis 2007;11:597–613. 10.1016/j.cld.2007.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kubota T, Fujisaki K, Itoh Y, et al. . Apoptotic injury in cultured human hepatocytes induced by HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Biochem Pharmacol 2004;67:2175–86. 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.02.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ballarè M, Campanini M, Airoldi G, et al. . Hepatotoxicity of hydroxy-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol 1992;38:41–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Heuer T, Gerards H, Pauw M, et al. . [Toxic liver damage caused by HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor]. Med Klin 2000;95:642–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Koornstra JJ, Ottervanger JP, Fehmers MC, et al. . [Clinically manifest liver lesions during use of simvastatin]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 1996;140:846–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Black DM, Bakker-Arkema RG, Nawrocki JW. An overview of the clinical safety profile of atorvastatin (lipitor), a new HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:577–84. 10.1001/archinte.158.6.577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lebrec D, Poynard T, Bernuau J, et al. . A randomised controlled study of propranolol for prevention of recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis. Drugs 1989;37(Suppl 2):30–4. discussion 47 10.2165/00003495-198900372-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hillon P, Lebrec D, Muńoz C, et al. . Comparison of the effects of a cardioselective and a nonselective beta-blocker on portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 1982;2:528S–31. 10.1002/hep.1840020503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Aramaki T, Sekiyama T, Katsuta Y, et al. . Long-term haemodynamic effects of a 4-week regimen of nipradilol, a new beta-blocker with nitrovasodilating properties, in patients with portal hypertension due to cirrhosis. A comparative study with propranolol. J Hepatol 1992;15(1-2):48–53. 10.1016/0168-8278(92)90010-M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gatta A, Sacerdoti D, Merkel C, et al. . Use of a nonselective beta-blocker, nadolol, in the treatment of portal hypertension in cirrhotics. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res 1985;5:413–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pastori D, Polimeni L, Baratta F, et al. . The efficacy and safety of statins for the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Liver Dis 2015;47:4–11. 10.1016/j.dld.2014.07.170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dongiovanni P, Petta S, Mannisto V, et al. . Statin use and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in at risk individuals. J Hepatol 2015;63:705–12. 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nascimbeni F, Aron-Wisnewsky J, Pais R, et al. . Statins, antidiabetic medications and liver histology in patients with diabetes with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2016;3:e000075 10.1136/bmjgast-2015-000075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gupta TK, Toruner M, Chung MK, et al. . Endothelial dysfunction and decreased production of nitric oxide in the intrahepatic microcirculation of cirrhotic rats. Hepatology 1998;28:926–31. 10.1002/hep.510280405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rockey DC, Chung JJ. Reduced nitric oxide production by endothelial cells in cirrhotic rat liver: endothelial dysfunction in portal hypertension. Gastroenterology 1998;114:344–51. 10.1016/S0016-5085(98)70487-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shah V, Toruner M, Haddad F, et al. . Impaired endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity associated with enhanced caveolin binding in experimental cirrhosis in the rat. Gastroenterology 1999;117:1222–8. 10.1016/S0016-5085(99)70408-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zafra C, Abraldes JG, Turnes J, et al. . Simvastatin enhances hepatic nitric oxide production and decreases the hepatic vascular tone in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2004;126:749–55. 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Marrone G, Maeso-Díaz R, García-Cardena G, et al. . KLF2 exerts antifibrotic and vasoprotective effects in cirrhotic rat livers: behind the molecular mechanisms of statins. Gut 2015;64:1434–43. 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lin CY. Statins and risk of decompensation in hepatitis B virus-related and hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis: Methodological issues. Hepatology 2018;67:1174 10.1002/hep.29687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kim G, Jang SY, Nam CM, et al. . Statin use and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients at high risk: A nationwide nested case-control study. J Hepatol 2018;68:476–84. 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Magan-Fernandez A, Rizzo M, Montalto G, et al. . Statins in liver disease: not only prevention of cardiovascular events. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;12:743–4. 10.1080/17474124.2018.1477588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-030038supp001.pdf (149.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-030038supp002.pdf (74.8KB, pdf)