Abstract

Objectives

We hypothesised that chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)-specific health status measured by the COPD assessment test (CAT), respiratory symptoms by the evaluating respiratory symptoms in COPD (E-RS) and dyspnoea by Dyspnoea-12 (D-12) are independently based on specific conceptual frameworks and are not interchangeable. We aimed to discover whether health status, dyspnoea or respiratory symptoms could be related to smoking status and airflow limitation in a working population.

Design

This is an observational, cross-sectional study.

Participants

1566 healthy industrial workers were analysed.

Results

Relationships between D-12, CAT and E-RS total were statistically significant but weak (Spearman’s correlation coefficient=0.274 to 0.446). In 646 healthy non-smoking subjects, as the reference scores for healthy non-smoking subjects, that is, upper threshold, the bootstrap 95th percentile values were 1.00 for D-12, 9.88 for CAT and 4.44 for E-RS. Of the 1566 workers, 85 (5.4%) were diagnosed with COPD using the fixed ratio of the forced expiratory volume in one second/forced vital capacity <0.7, and 34 (2.2%) using the lower limit of normal. The CAT and E-RS total were significantly worse in non-COPD smokers and subjects with COPD than non-COPD never smokers, although the D-12 was not as sensitive. There were no significant differences between non-COPD smokers and subjects with COPD on any of the measures.

Conclusions

Assessment of health status and respiratory symptoms would be preferable to dyspnoea in view of smoking status and airflow limitation in a working population. However, these patient-reported measures were inadequate in differentiating between smokers and subjects with COPD identified by spirometry.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), patient-reported outcome (PRO), the COPD assessment test (CAT), Dyspnoea-12 (D-12), the evaluating respiratory symptoms in COPD (E-RS)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) assessment test (CAT), the evaluating respiratory symptoms in COPD (E-RS) and Dyspnoea-12 (D-12) are all easy to administer since the methodology used in their development is similar.

The authors sought the reference values of the scores obtained from the D-12 and E-RS for healthy non-smoking subjects that has not been reported although it has been considered that a CAT score of 10 is a cut-off value.

The main limitation of this study is that it was conducted with healthy industrial workers who were not randomly sampled, thereby potentially being biassed due to the ‘healthy worker effect’.

Introduction

Over the last two decades, patient reported outcomes (PROs) have been considered to be important in the assessment of healthcare services.1–4 The St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) has been one of the most frequently used tools for health status measurements in subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).5 Short and simple instruments have become commonplace since the reduction in the number of items has become possible by methodological innovations, including the use of Rasch analysis.6 7 First, Jones et al developed the COPD assessment test (CAT), which has been considered to be almost equivalent to the SGRQ, making the tool easy both to administer and for patients to complete.8–10 Second, although dyspnoea is one of the most important perceptions experienced in subjects with respiratory or cardiac disorders, it has not been easy to measure this perception due to sensory quality and affective components of dyspnoea. Yorke et al reported that Dyspnoea-12 (D-12) provides a global score of breathlessness severity and can measure dyspnoea in a variety of diseases.11–13 Third, another tool designed specifically to quantify exacerbations in COPD is the Exacerbations of Chronic Pulmonary Disease Tool (EXACT) patient-reported outcome (known as EXACT-PRO).14–16 Leidy et al reported that, using 11 respiratory symptom items from the 14-item EXACT, the evaluating respiratory symptoms in COPD (E-RS) is a reliable and valid instrument for evaluating respiratory symptom severity in stable COPD.17 18

The developers of the CAT, D-12 and E-RS have stated that the three PROs derive from different conceptual frameworks, but the methodology used in the development is similar. In subjects with COPD, it may be commonly accepted that breathlessness is included in respiratory symptoms, and that this symptom is one of the essential components of health status. Therefore, the D-12 would be reflected in the E-RS, and the E-RS in the CAT.

We hypothesised that COPD-specific health status measured by the CAT, dyspnoea by the D-12, and symptoms by the E-RS are independently based on specific conceptual frameworks and are not interchangeable in a general population, and that comprehensive symptomatic assessment of the CAT and E-RS would be preferable to dyspnoea by the D-12 in identifying subjects who may have COPD among that population. Hence, the purpose of the present study was to examine the discriminative properties of the CAT, D-12 and E-RS in relation to smoking status and airflow limitation and to investigate whether health status, dyspnoea and respiratory symptoms could be related to a diagnosis of COPD based on the results of spirometry.

Additionally, we previously reported that the 95th percentile of the CAT scores was 13.6 in 512 healthy non-smoking subjects although the CAT score distribution overlapped remarkably between both healthy non-smoking subjects and subjects with COPD.19 As a secondary endpoint of the present study, it was our objective to determine reference values of the scores obtained from the D-12 and E-RS for healthy non-smoking subjects.

Methods

Study design

This is a cross-sectional observational study.

Setting

The present study was conducted between March 2012 and April 2013 at the Niigata Association of Occupational Health Incorporated, Niigata, Japan.

Participants

The study subjects were healthy industrial workers over 40 years old who underwent annual health checks at this Association. All underwent a comprehensive health screening, including conventional spirometry. The exclusion criteria included: (1) abnormal findings of the pulmonary parenchyma and chest wall revealed on chest radiographs; (2) undergoing a thoracotomy in the past; (3) any admission to a hospital during the preceding 3 months (except hospitalisation for routine tests); (4) any physician-diagnosed pulmonary diseases including lung cancer, pulmonary tuberculosis, bronchiectasis or non-tuberculous mycobacteriosis except COPD as well as asthma; and (5) unstable complications of cardiovascular, neuromuscular, renal, endocrinological, haematological, gastrointestinal and hepatic co-morbidities. The information about their radiographic findings was obtained from annual health examinations. The participants also answered additional questions to investigate their smoking status and history.

Measurement

All eligible subjects completed the following examinations on the same day. Spirometry was performed with the use of nose clips in the sitting position with a Spiro Sift sp-470 Spirometer (Fukuda Denshi Co., Tokyo, Japan). All measurements were performed by a laboratory technician in accordance with guidelines published by the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society.20 The spirometric forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) values were the largest FVC and largest FEV1 selected from data obtained from at least three acceptable forced expiratory curves, even if these values were not obtained from the same curve.21 In this study, COPD was spirometrically defined as airflow limitation with a FEV1/FVC less than either a fixed ratio, 0.7, or lower limit of normal (LLN) without bronchodilator administration.22–25 Healthy subjects were defined as those with a FEV1 of >85% predicted or a FEV1/FVC of >0.7, forming two groups: subjects with a smoking history of ≥10 pack-years, and non-smoking subjects with a smoking history of <1 pack-year. This definition is similar to that of the Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate End-points study.26 27 The predicted values for pulmonary function were calculated based on the proposal from the Japanese Respiratory Society.28 The LLN for the Japanese population was calculated in the present study according to the method described by Osaka et al.29

The Japanese versions of the EXACT, CAT and D-12 were self-administered in the same order under supervision in a booklet form prior to the pulmonary function tests. The E-RS uses 11 respiratory symptom items from the 14-item EXACT, where scores range from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms.14–18 The RS-Total Score represents overall respiratory symptom severity.17 18 Three subscales were not used in this analysis. The Japanese translation has been created and provided by the original developers who recommend the use of an electronic version to collect the answers. However, no electronic device with the Japanese version of the EXACT or E-RS was available so all surveys were conducted using a paper-based method. Health status was assessed with a previously validated Japanese version of the CAT.30 The CAT consists of eight items scored from 0 to 5 in relation to cough, sputum, dyspnoea, chest tightness, capacity for exercise and activities, sleep quality and energy levels.9 10 The CAT Scores range from 0 to 40, with a score of zero indicating no impairment. To assess the severity of dyspnoea, we used the Japanese version of the D-12,31 which consists of twelve items (seven physical items and five affective items), each with a four point grading scale (0–3), producing a Total Score (range 0–36, with higher scores representing more severe breathlessness).11–13

Patient and public involvement

Patients were neither involved in the development of the research question, the design of this study, nor the recruitment to and conduct of the study. The abstract of the published paper will appear on the homepage of the institute.

Ethics

The present study was approved by the ethics committee of the Niigata Association of Occupational Health Incorporated. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Statistical methods

All results are expressed as means±SD. Relationships between two sets of data were analysed by Spearman’s rank correlation tests. In order to determine reference values for each score, we calculated the 95th percentile of the scores in healthy, non-smoking subjects using the Monte Carlo and bootstrap methods with 1000 bootstrap reps and used this as the upper limit of normal.32 In comparing the groups of COPD, non-COPD smokers and non-COPD never smokers, the significance of between-group difference was determined by an analysis of variance for FEV1 or a Kruskal-Wallis test for PRO scores, and when a significant difference was observed, Tukey tests or Steel-Dwass tests were used to analyse where the differences were significant, respectively. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics V.22.0 (International Business Machines Corp., Armonk, New York, USA) and BellCurve for Excel (Social Survey Research Information Co., Tokyo, Japan). A p value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Subject characteristics

A total of 1634 subjects initially participated in the study but 68 were subsequently excluded from the data analysis because of uncertainty over their smoking or other history or having one of the exclusion criteria. Therefore, a total of 1566 subjects (985 males) were analysed. Their demographic details and spirometric results are shown in table 1. The mean age of the subjects was 53.0 years. The mean FEV1 value was 99.6%±13.1% predicted. The FEV1/FVC ratio used as an index of airflow limitation ranged from 52.5% to 97.4%, with a mean of 80.1%. There was no difference between groups in the frequency of self-reported history of asthma.

Table 1.

Demographic details and spirometric results

| Total subjects | Age | Male | Cumulative smoking | Prior diagnosis of asthma | Prior diagnosis of COPD | FEV1 | FEV1/FVC | |

| Number | Years | Number (%) | Pack-years | Number (%) | Number (%) | % predicted | % | |

| All subjects | 1566 | 53.0±8.7 | 985 (62.9%) | 14.1±18.6 | 46 (2.9%) | 10 (0.6%) | 99.6±13.1 | 80.1±5.8 |

| Healthy non-smoking subjects*† | 646 | 53.3±8.8 | 189 (29.3%) | 0.0±0.1 | 17 (2.6%) | 2 (0.3%) | 105.5±10.7 | 82.3±4.4 |

| COPD defined by fixed ratio | 85 | 60.4±9.4 | 83 (97.6%) | 36.9±28.1 | 5 (5.9%) | 4 (4.7%) | 80.2±11.6 | 66.0±4.1 |

| Non-COPD smokers | 817 | 51.9±8.0 | 704 (86.2%) | 23.1±16.9 | 23 (2.8%) | 4 (0.5%) | 97.9±11.8 | 80.1±4.7 |

| Non-COPD never smokers | 664 | 53.4±8.9 | 198 (29.8%) | 0.0±0.0 | 18 (2.7%) | 2 (0.3%) | 104.2±12.0 | 82.0±4.5 |

| COPD defined by LLN | 34 | 57.7±10.4 | 29 (85.3%) | 31.9±25.8 | 2 (5.9%) | 2 (5.9%) | 77.3±13.1 | 63.0±4.9 |

| Non-COPD smokers | 867 | 52.4±8.3 | 755 (87.1%) | 24.2±18.3 | 26 (3.0%) | 6 (0.7%) | 97.1±12.3 | 79.4±5.3 |

| Non-COPD never smokers | 665 | 53.5±8.9 | 201 (30.2%) | 0.0±0.0 | 18 (2.7%) | 2 (0.3%) | 104.1±12.1 | 82.0±4.5 |

*FEV1 of >85% predicted and FEV1/FVC of >0.7.

†A smoking history of <1 pack-year.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; LLN, lower limit of normal.

The scores for the D-12, CAT and E-RS are shown in table 2. They were skewed to the milder ends, and a floor effect was seen in all of the scores. This effect was most pronounced for the D-12 (84.0%) and E-RS (53.3%), and least for the CAT (14.6%). Regarding the interrelationships between the D-12, CAT and E-RS, they were significantly but only weakly correlated with each other (D-12 vs CAT, Spearman’s correlation coefficient (Rs)=0.398, p<0.001; D-12 vs E-RS, Rs=0.274, p<0.001; and CAT vs E-RS, Rs=0.446, p<0.001).

Table 2.

Distributions of the D-12, CAT and E-RS total scores

| D-12 score (0–36) | CAT score (0–40) | E-RS Total score (0–40) | |||||||||||||

| Mean | Median | SD | Max. | Floor effect (%) | Mean | Median | SD | Max. | Floor effect (%) | Mean | Median | SD | Max. | Floor effect (%) | |

| All subjects | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 6.0 | 84.0 | 4.3 | 3.0 | 3.9 | 25.0 | 14.6 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 15.0 | 53.3 |

| Healthy non-smoking subjects*† | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 6.0 | 86.5 | 3.6 | 3.0 | 3.3 | 24.0 | 15.9 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 10.0 | 62.5 |

| COPD defined by fixed ratio | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 4.0 | 81.2 | 4.8 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 19.0 | 15.3 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 2.2 | 12.0 | 44.7 |

| Non-COPD smokers | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 6.0 | 82.0 | 4.8 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 25.0 | 13.1 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 15.0 | 46.5 |

| Non-COPD never smokers | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 6.0 | 86.7 | 3.6 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 24.0 | 16.3 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 12.0 | 62.7 |

| COPD defined by LLN | 0.5 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 73.5 | 6.2 | 6.0 | 4.8 | 19.0 | 14.7 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 9.0 | 38.2 |

| Non-COPD smokers | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 6.0 | 82.2 | 4.8 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 25.0 | 13.0 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 15.0 | 46.6 |

| Non-COPD never smokers | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 6.0 | 86.8 | 3.6 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 24.0 | 16.5 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 10.0 | 62.7 |

*FEV1 of >85% predicted and FEV1/FVC of >0.7.

†A smoking history of <1 pack-year. Numbers in parentheses indicate the theoretical score range, and higher scores indicate worse status.

CAT, COPD assessment test; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; D-12, Dyspnoea-12; E-RS, evaluating respiratory symptoms in COPD; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; LLN, lower limit of normal.

In order to determine the reference values, from the data obtained from 646 healthy non-smoking subjects (tables 1 and 2), the bootstrap 95th percentile values were subsequently calculated and used as the upper limit of normal. For the D-12, this was 1.00; for the E-RS, it was 4.44. Since these scores do not contain decimals, the reference values for the D-12 and E-RS Total Scores were considered to be ≤1 and ≤4, respectively. In the same way, the reference value of the CAT was calculated to be 9.88, which rounds up to 10, in the present study.

Concordant and discordant results between tools were set to be examined using the above cut-off values (table 3). However, since there were only a small number of subjects with higher scores on each instrument due to skewed score distribution, those with higher scores on one instrument and lower scores on another were less than one-tenth of all of the subjects involved.

Table 3.

Concordant and discordant results between tools using the cut-off values

| COPD assessment test (CAT) and evaluating respiratory symptoms in COPD (E-RS) | |||

| E-RS Total Score | |||

| 0–4 | 5 or more | ||

| CAT score | 0–9 | 1343 (86%) | 63 (4%) |

| 10 or more | 113 (7%) | 47 (3%) | |

| COPD assessment test (CAT) and Dyspnoea-12 (D-12) | |||

| D-12 score | |||

| 0–1 | 2 or more | ||

| CAT score | 0–9 | 1386 (89%) | 20 (1%) |

| 10 or more | 141 (9%) | 19 (1%) | |

| Evaluating respiratory symptoms in COPD (E-RS) and Dyspnoea-12 (D-12) | |||

| D-12 score | |||

| 0–1 | 2 or more | ||

| E-RS Total score | 0–4 | 1428 (91%) | 28 (2%) |

| 5 or more | 99 (6%) | 11 (1%) | |

Relationships of COPD-specific PROs with smoking and airflow limitation

We then divided the 1566 subjects into three groups consisting of a COPD group based on the FEV1/FVC using a fixed ratio, 0.7, or LLN; non-COPD current or past smokers; and non-COPD never smokers (tables 1 and 2). Using the fixed ratio of the FEV1/FVC<0.7, 85 subjects (5.4%) were diagnosed with COPD, 817 (52.2%) were non-COPD smokers, and 664 (42.4%) were non-COPD never smokers. Using the LLN definition, 34 subjects (2.2%) were diagnosed with COPD, 867 (55.4%) were non-COPD smokers and 665 (42.5%) were non-COPD never smokers.

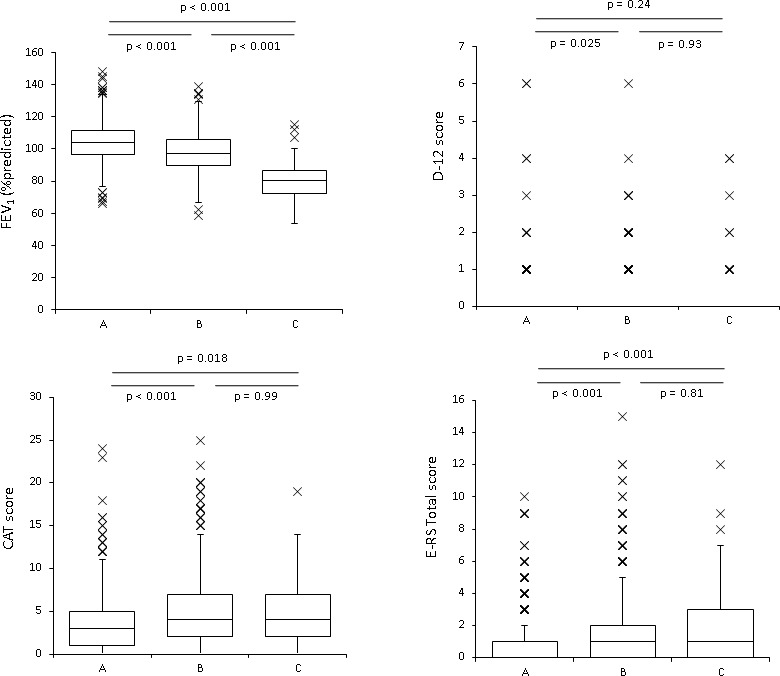

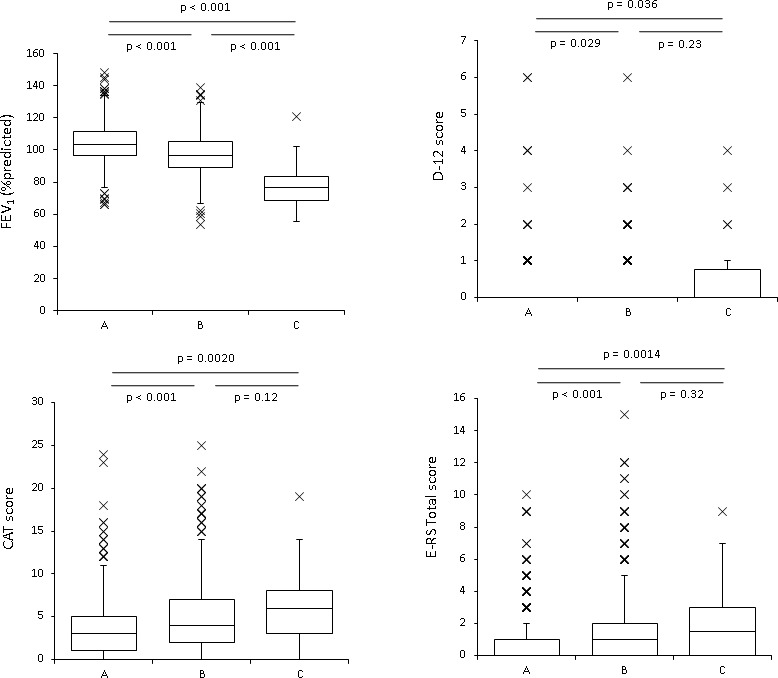

Relationships of the PROs between the three groups of subjects with COPD, non-COPD smokers and non-COPD never smokers are shown in figure 1 (COPD based on the fixed ratio) and figure 2 (COPD based on the LLN). The FEV1 (%predicted), D-12, CAT and E-RS Total were significantly separated between the three groups (p<0.05). There were significant differences between the three groups for FEV1 (%predicted), D-12, CAT and E-RS Total (p<0.05). FEV1 was significantly different between any two of the three groups (p<0.001) (figures 1 and 2). With regard to the score distribution (table 2), floor effect in subjects with COPD was most prominent for the D-12 (81.2% by the fixed definition and 73.5% by the LLN), and their median scores were 0.0 (table 2). It was the least for the CAT (15.3% by the fixed definition and 14.7% by the LLN).

Figure 1.

Box plots representing the distributions of FEV1 (%predicted), D-12 (Dyspnoea-12) score, CAT (COPD assessment test) score and E-RS (Evaluating Respiratory Symptoms in COPD) Total score in non-COPD never smokers (Group A, n=664), non-COPD current or past smokers (Group B, n=817) and COPD based on FEV1/FVC using a fixed ratio, 0.7 (Group C, n=85). The horizontal lines in the boxes represent the median, and the top and bottom of the boxes represent the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively. Bars represent the upper adjacent value (75th percentile plus 1.5 times the IQR) and the lower adjacent value (25th percentile minus 1.5 times the IQR), and the crosses represent outliers. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Figure 2.

Box plots representing the distributions of FEV1 (%predicted), D-12 (Dyspnoea-12) score, CAT (COPD assessment test) score and E-RS (Evaluating Respiratory Symptoms in COPD) Total score in non-COPD never smokers (Group A, n=665), non-COPD current or past smokers (Group B, n=867) and COPD based on FEV1/FVC using the LLN (Group C, n=34). The horizontal lines in the boxes represent the median, and the top and bottom of the boxes represent the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively. Bars represent the upper adjacent value (75th percentile plus 1.5 times the IQR) and the lower adjacent value (25th percentile minus 1.5 times the IQR), and the crosses represent outliers. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1s; FVC, forced vital capacity.

In investigating how many were symptomatic among 817 (by the fixed definition) and 867 (by the LLN definition) non-COPD smokers, using the above reference values, 24 (2.9%) and 24 (2.8%) were >1 on the D-12, 79 (9.7%) and 80 (9.2%) were >10 on the CAT, and 74 (9.1%) and 76 (8.8%) were >4 on the E-RS.

Regarding the group comparisons, significant differences were found between non-COPD never smokers and non-COPD smokers on all of the measures; however, significance was relatively weaker for the D-12 score (p=0.025 (figure 1) and 0.029 (figure 2)) as compared with the CAT and E-RS Total (p<0.001). On the CAT and E-RS Total, significant differences were also found between non-COPD never smokers and subjects with COPD (p<0.05); however, on the D-12, a significant difference was found only by the LLN definition (p=0.036, figure 2), but not by the fixed ratio definition (p=0.24, figure 1). Neither the D-12, CAT nor E-RS Total were significantly different between COPD and non-COPD smokers.

Discussion

This is the first study to directly compare differences among three COPD-specific outcomes, including dyspnoea, respiratory symptoms or health status in a general working population. First, the associations between dyspnoea measured by the D-12, health status by the CAT and respiratory symptoms by the E-RS were significant but weak, indicating that they were far below the level of conceptual similarity. This relationship may be expected since the three PRO measurement tools were created by each developer from independent conceptual frameworks. Second, from the data obtained from 646 healthy non-smoking subjects, the bootstrap 95th percentile values were an E-RS Total score of 4.44 indicating that the reference value is ≤4. The reference values for the D-12 and CAT score are also ≤1 and ≤10, respectively. Third, from a standpoint of the relationship with smoking status and airflow limitation, in comparison to non-COPD never smokers, health status by the CAT and respiratory symptoms by the E-RS were worse in non-COPD smokers and subjects with COPD, although dyspnoea by the D-12 was not as sensitive. None of these PRO measures were adequate in differentiating between non-COPD smokers and subjects with COPD.

In the present study, there were considerable numbers of smokers with preserved pulmonary function, or without airflow limitation, 52.2% by the fixed ratio and 55.4% by the LLN, respectively, who may be diagnosed as COPD-free by spirometric criteria. Their dyspnoea, health status and respiratory symptoms were significantly worse than those in never smokers, which is compatible with recent population studies.33–36 They also indicated that pulmonary disease and impairments were common in smokers with preserved pulmonary function although they did not meet the current criteria of COPD based on spirometry,35 36 and that symptoms might be more sensitive than spirometry in detecting smoking-related respiratory impairments. Actually, symptom-based questionnaires to screen for COPD that do not include spirometry have been developed.37 38

Conversely, the present study adds that PROs in non-COPD smokers were not significantly different from those in subjects with COPD. Actually, about 9% of smokers with preserved pulmonary function were judged to be symptomatic according to the reference values of CAT >10 or E-RS >4. Their symptoms may tend to exacerbate in the future, advance to COPD, or be treated as if they were COPD. How to manage this group of symptomatic smokers without airflow limitation is a key issue to be solved through careful long-term follow-ups.

The global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease (GOLD) 2011 consensus report proposed a revised ‘combined COPD assessment’ classification in which symptoms should be assessed either as a dyspnoea measure using the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnoea scale, or as a health status measure using the CAT.39 We have contributed to the establishment of this concept by demonstrating the significant predictive properties of dyspnoea and health status independently of airflow limitation.40 41 There has hitherto been much debate over how to assess symptoms in this new classification. Although dyspnoea was not measured by the mMRC dyspnoea scale but by D-12, interrelationships between the D-12, CAT and E-RS were weak to moderate. Therefore, it may be difficult to use dyspnoea, health status and respiratory symptoms in a mutually complementary form. The GOLD recommends a comprehensive assessment of symptoms rather than just a measure of dyspnoea. The present study supports this by showing that the D-12 had the most marked floor effects even in subjects with COPD, and that the CAT and E-RS seemed to be more sensitive in discriminating subjects based on smoking and COPD than the D-12.

We reported in 2013 that the 95th percentile of the scores in 512 healthy, non-smoking subjects were used as the upper limit of normal in exactly the same way as in the present study.19 For the CAT, it was 13.6. In 2014 Pinto et al 42 published some of the results of the Canadian cohort obstructive lung disease study and reported that the normative value for the CAT score was determined to be 16 from a population-based study where they used post-bronchodilator spirometric values. Compared with the above two reports, a score of 10 was the 95th percentile of the scores in healthy industrial workers from Japan, and it is the lowest in the present study. The GOLD currently states that the boundary between GOLD A and B and between GOLD C and D is a CAT score of 10,39 43 which is consistent with the important result of the present study although there might be some margin of error depending on the methodologies and subjects of the studies.

This study has several limitations. Although we intended to determine the border of the normal level of the D-12, CAT and E-RS Total scores, the study subjects were not randomly sampled and there could be a risk of sample bias. The D-12, CAT and E-RS are sufficiently validated for measuring PROs in subjects with COPD, but most participants were not patients with COPD but rather healthy workers. As such, there is a possibility that they are not appropriate tools for the study population. However, since the successful application of the CAT in a working population or a random sampling frame from the populations has also been reported,19 42 there may be a reason to be hopeful for success with the D-12 and E-RS. Although post-bronchodilator spirometric values are recommended to be used to make a diagnosis of COPD,39 43 the diagnosis was made only from pre-bronchodilator spirometric information in the present study. Furthermore, the present study was conducted in Japanese so that each of the instruments would have been translated from the original language of its development. Although the Japanese version has been validated in each case, it may be a limit to the generalisability of the research across the globe.

Three main conclusions may be drawn from our findings. First, associations among dyspnoea measured by the D-12, health status by the CAT, and respiratory symptoms by the E-RS, were statistically significant but weak, indicating that they cannot be used interchangeably. Second, using the data obtained from 646 healthy non-smoking subjects, the reference values of the D-12, CAT and E-RS were ≤1, ≤10 and≤4, respectively. Third, from a standpoint of the relationship with smoking status and airflow limitation, health status and respiratory symptoms may be more closely related to non-COPD smokers and subjects with COPD than dyspnoea as compared with non-COPD never smokers; however, none of these PRO measures can differentiate between non-COPD smokers and subjects with COPD. How to manage non-COPD symptomatic smokers should be investigated in the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Nancy Kline Leidy for permission to use the Japanese version of the E-RS.

Footnotes

Contributors: KN contributed, as the principal investigator, to the study concept and design, analysis of the results and writing of the manuscript. TO contributed to statistical analysis, the interpretation and editing of the manuscript. KN contributed to statistical analysis. MO contributed to acquisition of data. YH contributed to the interpretation and editing of the manuscript. SM contributed to performance of the study and acquisition of data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was partly supported by the Research Funding for Longevity Sciences (30-24) from the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology (NCGG), Japan.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Niigata Association of Occupational Health Incorporated (No. 6, last dated 8 January 2013).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No data are available.

References

- 1. Kyte D, Duffy H, Fletcher B, et al. . Systematic evaluation of the patient-reported outcome (pro) content of clinical trial protocols. PLoS One 2014;9:e110229 10.1371/journal.pone.0110229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jones PW. Health status measurement in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2001;56:880–7. 10.1136/thorax.56.11.880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. DeMuro C, Clark M, Doward L, et al. . Assessment of pro label claims granted by the FDA as compared to the EMA (2006-2010). Value Health 2013;16:1150–5. 10.1016/j.jval.2013.08.2293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gnanasakthy A, Mordin M, Evans E, et al. . A review of patient-reported outcome labeling in the United States (2011-2015). Value Health 2017;20:420–9. 10.1016/j.jval.2016.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM, et al. . A self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation. The St. George's respiratory questionnaire. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992;145:1321–7. 10.1164/ajrccm/145.6.1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Andrich D. Rasch models for measurement. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rasch G. Probabilistic models for some intelligence and attainment tests. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gupta N, Pinto LM, Morogan A, et al. . The COPD assessment test: a systematic review. Eur Respir J 2014;44:873–84. 10.1183/09031936.00025214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jones PW, Brusselle G, Dal Negro RW, et al. . Properties of the COPD assessment test in a cross-sectional European study. Eur Respir J 2011;38:29–35. 10.1183/09031936.00177210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, et al. . Development and first validation of the COPD assessment test. Eur Respir J 2009;34:648–54. 10.1183/09031936.00102509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yorke J, Swigris J, Russell A-M, et al. . Dyspnea-12 is a valid and reliable measure of breathlessness in patients with interstitial lung disease. Chest 2011;139:159–64. 10.1378/chest.10-0693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Swigris JJ, Yorke J, Sprunger DB, et al. . Assessing dyspnea and its impact on patients with connective tissue disease-related interstitial lung disease. Respir Med 2010;104:1350–5. 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.03.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yorke J, Moosavi SH, Shuldham C, et al. . Quantification of dyspnoea using descriptors: development and initial testing of the Dyspnoea-12. Thorax 2010;65:21–6. 10.1136/thx.2009.118521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Leidy NK, Wilcox TK, Jones PW, et al. . Standardizing measurement of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. reliability and validity of a patient-reported diary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:323–9. 10.1164/rccm.201005-0762OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jones PW, Chen W-H, Wilcox TK, et al. . Characterizing and quantifying the symptomatic features of COPD exacerbations. Chest 2011;139:1388–94. 10.1378/chest.10-1240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leidy NK, Wilcox TK, Jones PW, et al. . Development of the exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease tool (exact): a patient-reported outcome (pro) measure. Value Health 2010;13:965–75. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00772.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Leidy NK, Murray LT, Monz BU, et al. . Measuring respiratory symptoms of COPD: performance of the EXACT- respiratory symptoms tool (E-RS) in three clinical trials. Respir Res 2014;15:124 10.1186/s12931-014-0124-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Leidy NK, Sexton CC, Jones PW, et al. . Measuring respiratory symptoms in clinical trials of COPD: reliability and validity of a daily diary. Thorax 2014;69:424–30. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nishimura K, Mitsuma S, Kobayashi A, et al. . COPD and disease-specific health status in a working population. Respir Res 2013;14:61 10.1186/1465-9921-14-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. . Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005;26:319–38. 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Koyama H, Nishimura K, Ikeda A, et al. . A comparison of different methods of spirometric measurement selection. Respir Med 1998;92:498–504. 10.1016/S0954-6111(98)90298-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. García-Rio F, Soriano JB, Miravitlles M, et al. . Overdiagnosing subjects with COPD using the 0.7 fixed ratio: correlation with a poor health-related quality of life. Chest 2011;139:1072–80. 10.1378/chest.10-1721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Swanney MP, Ruppel G, Enright PL, et al. . Using the lower limit of normal for the FEV1/FVC ratio reduces the misclassification of airway obstruction. Thorax 2008;63:1046–51. 10.1136/thx.2008.098483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. van Dijk W, Tan W, Li P, et al. . Clinical relevance of fixed ratio vs lower limit of normal of FEV1/FVC in COPD: patient-reported outcomes from the CanCOLD cohort. Ann Fam Med 2015;13:41–8. 10.1370/afm.1714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vollmer WM, Gíslason T, Burney P, et al. . Comparison of spirometry criteria for the diagnosis of COPD: results from the BOLD study. Eur Respir J 2009;34:588–97. 10.1183/09031936.00164608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vestbo J, Anderson W, Coxson HO, et al. . Evaluation of COPD longitudinally to identify predictive surrogate end-points (eclipse). Eur Respir J 2008;31:869–73. 10.1183/09031936.00111707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Agusti A, Calverley PMA, Celli B, et al. . Characterisation of COPD heterogeneity in the ECLIPSE cohort. Respir Res 2010;11:122 10.1186/1465-9921-11-122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Society CPFCotJR The predicted values of pulmonary function testing and artrial blood gas in Japanese [in Japanese]. Jpn J Thorac Dis 2001;39. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Osaka D, Shibata Y, Abe S, et al. . Relationship between habit of cigarette smoking and airflow limitation in healthy Japanese individuals: the Takahata study. Intern Med 2010;49:1489–99. 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tsuda T, Suematsu R, Kamohara K, et al. . Development of the Japanese version of the COPD assessment test. Respir Investig 2012;50:34–9. 10.1016/j.resinv.2012.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kusunose M, Oga T, Nakamura S, et al. . Frailty and patient-reported outcomes in subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: are they independent entities? BMJ Open Respir Res 2017;4:e000196 10.1136/bmjresp-2017-000196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap (Chapman & Hall/CRC Monographs on Statistics & Applied Probability), 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Elbehairy AF, Guenette JA, Faisal A, et al. . Mechanisms of exertional dyspnoea in symptomatic smokers without COPD. Eur Respir J 2016;48:694–705. 10.1183/13993003.00077-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Furlanetto KC, Mantoani LC, Bisca G, et al. . Reduction of physical activity in daily life and its determinants in smokers without airflow obstruction. Respirology 2014;19:369–75. 10.1111/resp.12236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Regan EA, Lynch DA, Curran-Everett D, et al. . Clinical and radiologic disease in smokers with normal spirometry. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1539–49. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Woodruff PG, Barr RG, Bleecker E, et al. . Clinical significance of symptoms in smokers with preserved pulmonary function. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1811–21. 10.1056/NEJMoa1505971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Martinez FJ, Raczek AE, Seifer FD, et al. . Development and initial validation of a self-scored COPD population screener questionnaire (COPD-PS). COPD 2008;5:85–95. 10.1080/15412550801940721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Price DB, Tinkelman DG, Halbert RJ, et al. . Symptom-Based questionnaire for identifying COPD in smokers. Respiration 2006;73:285–95. 10.1159/000090142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agustí AG, et al. . Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: gold executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;187:347–65. 10.1164/rccm.201204-0596PP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nishimura K, Izumi T, Tsukino M, et al. . Dyspnea is a better predictor of 5-year survival than airway obstruction in patients with COPD. Chest 2002;121:1434–40. 10.1378/chest.121.5.1434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Oga T, Nishimura K, Tsukino M, et al. . Analysis of the factors related to mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: role of exercise capacity and health status. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:544–9. 10.1164/rccm.200206-583OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pinto LM, Gupta N, Tan W, et al. . Derivation of normative data for the COPD assessment test (cat). Respir Res 2014;15:68 10.1186/1465-9921-15-68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, et al. . Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 report. gold executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;195:557–82. 10.1164/rccm.201701-0218PP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.