Abstract

Objectives

To assess the degree to which variations in publicly reported hospital scores arising from the English Cancer Patient Experience Survey (CPES) are subject to chance.

Design

Secondary analysis of publically reported data.

Setting

English National Health Service hospitals.

Participants

72 756 patients who were recently treated for cancer in one of 146 hospitals and responded to the 2016 English CPES.

Main outcome measures

Spearman-Brown reliability of hospital scores on 51 evaluative questions regarding cancer care.

Results

Hospitals varied in respondent sample size with a median hospital sample size of 419 responses (range 31–1972). There were some hospitals with generally highly reliable scores across most questions, whereas other hospitals had generally unreliable scores (the median reliability of question scores within individual hospitals varied between 0.11 and 0.86). Similarly, there were some questions with generally high reliability across most hospitals, whereas other questions had generally low reliability. Of the 7377 individual hospital scores publically reported (146 hospitals by 51 questions, minus 69 suppressed scores), only 34% reached a reliability of 0.7, the minimum generally considered to be useful. In order for 80% of the individual hospital scores to reach a reliability of 0.7, some hospitals would require a fourfold increase in number of respondents; although in a few other hospitals sample sizes could be reduced.

Conclusions

The English Patient Experience Survey represents a globally unique source for understanding experience of a patient with cancer; but in its present form, it is not reliable for high stakes comparisons of the performance of different hospitals. Revised sampling strategies and survey questions could help increase the reliability of hospital scores, and thus make the survey fit for use in performance comparisons.

Keywords: oncology, quality improvement, medical management, health service research, patients, health policy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We make use of the actual data used in public reporting of a high-profile survey with a high response rate, allowing us to make direct inferences about the quality indicators under consideration.

Mixed effects logistic regression models are used to effectively partition the observed variability in hospital scores into that which is due to chance and that which reflects true differences between hospitals.

Our analysis considers three different contributing factors affecting the reliability of hospital scores which can give insight into designing potential improvement efforts.

This study only considers the crude hospital scores and not those adjusted for patient case mix which have recently been reported. However, as we expect any such adjustment to result in lower reliabilities the conclusions of the study remain valid.

Introduction

‘Before you can improve it you first have to measure it’ is a common adage of the quality improvement movement across the world.1 Coupled with a tendency towards greater public accountability, this maxim has led to an ever-increasing number of measurement initiatives, typically underpinned by public reporting of scores of healthcare organisations.2 3

Together with patient safety and clinical effectiveness, patient experience is being increasingly accepted as a distinct dimension of care quality.4 Relatedly, policymakers regularly commission large-scale nationwide patient surveys in the USA and the UK.5–7 Most such surveys are aimed at patients with a diverse range of conditions. However, a repeatable disease-specific survey for patients with cancer was launched in England in 2010, and its findings are reported publicly and used by healthcare improvement teams in constructing and evaluating action plans.

The statistical reliability of measures of care quality remains a concern, as often the sample sizes involved in organisational comparisons are small. Ideally, measurement initiatives should follow prior examination of the statistical properties of indicators, but this is rarely the case. Some previous UK work has examined the reliability of indicators of stage at diagnosis, diagnostic activity, general practice patient experience and general practice high risk prescribing, on the whole providing cautionary findings indicating the risk of unreliability of organisational rankings.8–12 Similar approaches and findings have been reported from the USA and Dutch settings.13–19

These considerations highlight the need for examining the reliability of hospital scores for the Cancer Patient Experience Survey (CPES) and have motivated us to examine this question empirically in this study. Its aim was to provide a detailed profile of the statistical reliability (and therefore of the role of chance) in hospital scores derived from the CPES.

Methods

Data were analysed relating to respondents to the 2016 CPES. The (English) CPES 2016 survey questionnaire is the sixth iteration of the survey first undertaken in 2010. It includes many evaluative questions covering the experience of diagnosis, diagnostic testing, shared decision-making, specialist nursing, inpatient care, anticancer treatment (surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy), hospital discharge and care in the community, together with an item for overall satisfaction with care. Survey results are reported publicly for each English hospital to drive local quality improvements to assist commissioners and providers of cancer care and to inform the work of the various charities and stakeholder groups supporting patients with cancer. The survey was mailed to all adult patients (aged 16 and over) discharged from a National Health Service hospital after inpatient or a day case cancer-related treatment during April–June 2016 after vital status checks at survey mail out (between 3 and 5 months after the sampling period).

Respondents comprised patients aged 16 years and olderwho were treated for cancer in English National Health Service (NHS) hospitals during April–June 2016. The patients had relevant International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes for cancer (C00-99 excluding C44 and C84 and D05) and were not known to have died prior to the survey mail out. Questionnaires were sent by post and responses could be made by post, online or using a telephone translation service. Details of the survey and method of administration have been published previously.20 In this study, we make use of publically reported hospital level data.21

Survey questions have up to seven response options which are dichotomised for public reporting such that hospitals scores represent the percentage of patients reporting a positive experience for each question. Scores are produced for hospital trusts and Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCG). Further details are given in the technical documentation.22

We calculated the Spearman-Brown (interunit) reliability of each hospital score. This is equivalent to the proportion of variation in hospital-level mean scores (for a given hospital sample size) attributable to the true (underlying) variation between them. Following previous work, we estimated reliability by partitioning the observed variability in hospital scores into two components, variability between hospitals and variability within hospitals, using mixed effects logistic regression models.8 23 For each question, a random intercept model (with no fixed effects other than the constant) was used to estimate the between hospital variance on the log-odds scale. This variance is a measure of the true (underlying) variation which can be thought of as that which would be seen with very large sample sizes in each hospital, such that the influence of sampling variation would be minimal.8 23 Since our scores are binary measures, the within-hospital variance also depends on the level of achievement at each hospital and can be described by the binomial distribution. In this context, for each question the reliability λ of hospital i is given by

| (1) |

where is the true (underlying) between-hospital variance on the log-odds scale, is the observed proportion of patients reporting a positive experience in hospital and is the sample size of hospital . High stakes purposes have important consequences for an individual or organisation (ie, when attached to a financial incentive, publicly reported league tables or an outcome measure in a research study) and therefore require high measure reliability. Reliability can take values from 0 to 1. Values <0.70 are considered to represent low reliability, whereas values ≥0.90 represent high reliability, required for ‘high stake’ purposes; in-between values are considered to represent adequate reliability.

Where less than 21 responses were received for an individual question for a hospital, results were not publicly reported. Of the 148 hospitals included in the survey, there were two hospitals with less than 21 responses for every question. We excluded these two hospitals from our analysis. However, there remained 69 suppressed scores (from 18 hospitals) in the publically reported data due to low numbers of respondents to certain questions applicable to only some patients. These scores were excluded from the analysis.

We calculated reliability for every hospital score on each question (a total of 146 hospitals multiplied by 51 questions=7446 individual scores, minus 69 suppressed scores=7377 individual scores).

Additionally, the model outputs were used to estimate the increase in sample size required for each hospital to reach a reliability of 0.7 for each question.8 23 We used R V.3.4.4 for all analyses.

Patient involvement

The CPES development and administration are supported by an advisory group which includes patient advocates. The present study forms part of a wider project funded by MacMillan Cancer Support for which there is an advisory group with patient representative participation.

Results

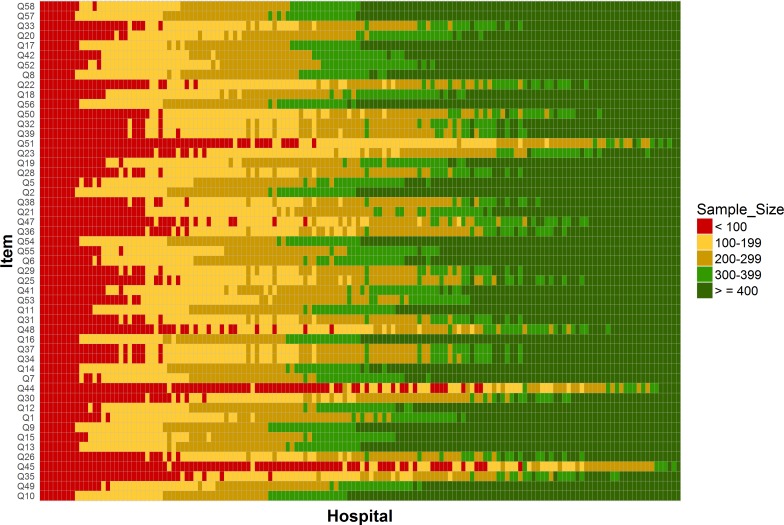

Overall, there were 72 756 respondents to the CPES in 2016 (response rate 66%) who were treated at the 146 hospitals included in our analysis. Our findings are displayed in three figures each comprising a grid of hospitals by questions. Hospitals are ordered according to the number of responders and questions are ordered according to the between-hospital variance. Hospitals varied in respondent sample size with a median of 419 responses (range 31–1972). Due to different sections of the questionnaire corresponding to different care pathways, not all questions were applicable to all patients and so the number of respondents varied considerably for each of the 51 questions. The number of respondents answering individual questions varied between 15 968 (22%) and 71 773 (99%) with a median of 52 786 (73%). The number of respondents for each question in each hospital is shown in figure 1 and online supplementary material table 1.

Figure 1.

Sample sizes for each of the 146 hospitals included in the analysis by question (Cancer Patient Experience Survey 2016). Each rectangle corresponds to a single hospital and question. Its colour indicates one of five sample size categories as shown on the legend. The exact values for each cell in this plot are provided in online supplementary material table 1.

bmjopen-2019-029037supp001.xlsx (254.2KB, xlsx)

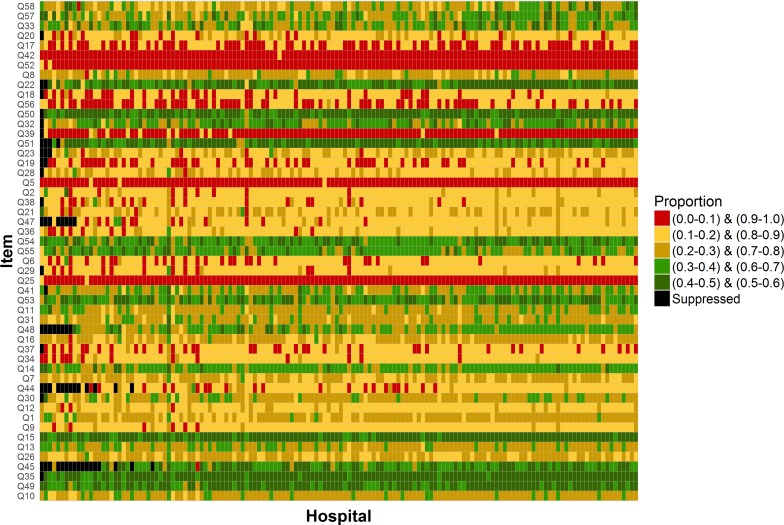

The percentage of patients reporting a positive experience was highly variable between questions and between hospitals (figure 2 and online supplementary material table 2). The median percentage of patients reporting positive experience across individual questions was 79% (range 29%–96%), while the corresponding median across individual hospitals was 75% (range 51%–82%).

Figure 2.

Proportions of patients reporting a positive experience by question and for each of the 146 hospitals included in the analysis (Cancer Patient Experience Survey 2016). Each rectangle corresponds to a single hospital and question. Its colour indicates one of five proportions categories as shown on the legend. The exact values for each cell in this plot are provided in the online supplementary material table 2.

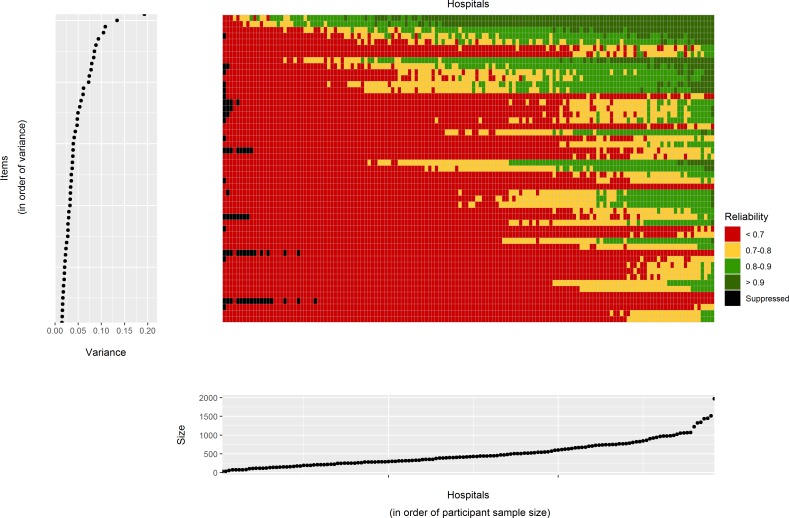

Figure 3 (and online supplementary material table 3) shows the reliability of the score for each question at each hospital. There were some hospitals with generally high reliability across most questions, whereas others had generally low reliability across survey items. The median reliability of question scores within individual hospitals was 0.60 (range 0.11–0.86). Similarly there were some questions with generally high reliability whereas others had generally low reliability. The median reliability of hospital scores within individual questions was 0.58 (range 0.21–0.93).

Figure 3.

Main central grid: reliability of hospital scores for each of the 146 hospitals included in the analysis (Cancer Patient Experience Survey 2016). Each rectangle corresponds to a single hospital and question. Its colour indicates one of four reliability categories as shown on the legend. Left hand side plot: the variance for each question on the log odds scale. The order of the questions has the same order than that of the main grid and is sorted from the question with lowest between-hospital variance to the question with greatest between-hospital variance. Bottom plot: the sample size for each hospital in terms of the total number of responders. The order of the hospitals has the same order than that of the main grid and is sorted from the hospital with the smallest sample size to the hospital with greatest sample size. The exact values for each cell in this plot are provided in the online supplementary material table 3.

Given that reliability depends on the sample size, the between-hospital variance and the hospital performance, we can examine how these factors influence reliability. Hospitals which tended to have low reliability also had small sample sizes. Also questions with low reliability tended to be those where the between-hospital variance is low. However, there are some exceptions to this which can be seen as the horizontal lines composed mostly of red squares in figure 3. Some CPES questions are unreliable across all hospitals because they have, across all hospitals, a small number of respondents to that particular question. Examples include questions only applicable to patients treated by radiotherapy (questions 44 and 45). In general, questions with small sample sizes relate to patients on a particular care pathway. Other examples of low reliability can be seen in questions for which hospitals performance is consistently high (questions 5 and 25).

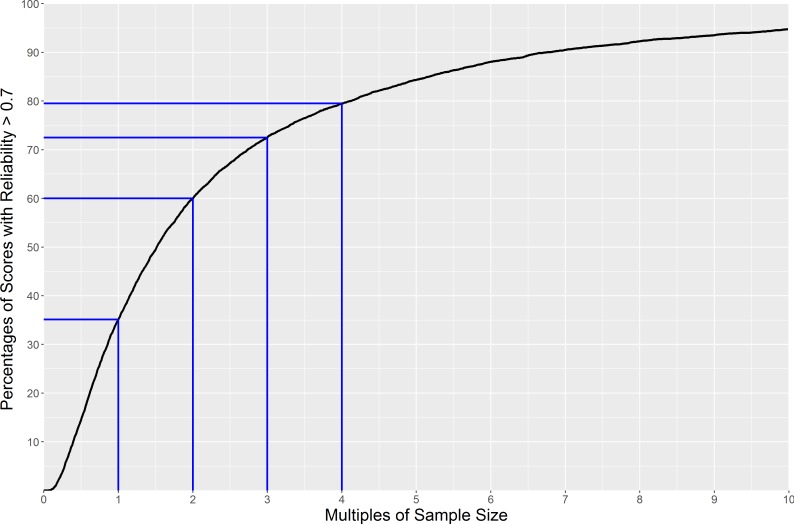

Overall, the reliability of hospitals scores for the survey is low. Of the 7377 individual hospital-question pairs, only 35% reached a reliability of 0.7, the minimum generally considered to be useful. As it is possible to improve reliability by increasing the sample size for a given hospital, we calculated how many multiples of the current sample size would be required to reach a reliability of 0.7 for each question (figure 4). It would be possible for 60% of hospital scores to reach a reliability of 0.7 by doubling the individual hospital sample size. Further increases lead to smaller gains, though 80% of the individual hospital scores would have achieved a reliability of 0.7 or more with four times as much data (which represents the upper limit of what could be achieved within a single year of data collection, though could also be achieved by aggregating over longer time periods).

Figure 4.

The expected percentage of hospital scores reaching a reliability of at least 0.7 when changing individual hospital sample sizes for each question.

Discussion

In this study, we have profiled the reliability of a high-profile national patient experience survey for patients with cancer. Our findings show that about two-thirds of hospital scores in this survey do not meet reliability levels generally accepted as useful. In practical terms, this means that identification of hospitals that are performing well in specific aspects of care is hampered due to the influence of chance. The lack of reliability can be attributed to different factors which have variable influence.

Although there are thousands of healthcare quality indicators in current use, most are bereft of any evaluation of their statistical reliability. Patient experience scores of English general practices arising from early waves of the GPPS survey were found to have very high reliability, enabling subsequent reductions in the survey sample.9 10 In contrast, the present study, examining the reliability of CPES hospital scores for the first time, suggests the need for increases in the survey samples (see below). The present study forms part of an emerging body of literature examining the reliability of a diverse range of quality indicators, including from the UK, the USA and The Netherlands8–19 22 23; we would nonetheless like to re-emphasise the mismatch between the very large number of indicators in current use and the small number of indicators that have been profiled for their reliability.

The key strength of this study is the use of the actual data used in public reporting of a high-profile survey with a high response rate. Its main limitation is that our analysis does not take into account the influence of patient case mix. Certain patient groups have systematic tendencies towards reporting positive experiences compared with others,24 25 and for this reason, the results of the survey are reported in both adjusted and unadjusted form. Nonetheless, as patient case mix explains some of the variability between hospitals,26 had we calculated the reliability of case-mix adjusted scores we would have found the reliability would have been even lower than that presented here.

There are some hospitals that have low reliability for most questions as they treat a small number of patients, meaning that the uncertainty on their scores is inherently high. Further, there are some questions with low reliability due to limited true (underlying) variation between hospitals. In such cases, it is very hard to distinguish between hospitals since they are all performing at a similar level. As a consequence, in the absence of very large sample sizes, the observed variability between hospitals will be dominated by chance. A particular example of this phenomenon occurs for questions whose performance is consistently high/low across hospitals. It is harder to distinguish hospitals when performance is close to 0% or 100%. Lastly, there are other questions with a small number of respondents as they are applicable to only subsets of patients. In brief, the key mechanisms leading to low reliability are small hospital-level respondent sample, limited variability between hospitals (including because of ceiling/flooring effects) and small survey-level respondent sample.

Given one of the main uses of CPES is to inform hospital level performance, one might suggest that in its current form, the survey is not fit for one of its main intended purposes (though it should be noted that the reliability limitations we report do not affect the use of the survey for providing national-level intelligence about the experience of patients with cancer across English hospitals). It could be argued that rather than suppressing score made on the basis of less than 20 respondents as is currently done, all scores which have a reliability below 0.7 should be suppressed. Work in other contexts have shown that when reliability of metrics is low, there is a large amount of misclassification of performance.23 27 At the very least, we believe that users of the survey results should be made aware of the reliability of the hospital scores (with such reliability estimates accompanying the publicly reported scores) so that an informed interpretation can be made by patients, clinicians, managers and members of the public. There is a range of reasons why such transparent reporting of reliability of hospital scores may be useful. For example, a hospital may chose to focus improvement efforts on those questions where they perform worse than average and where they know their scores to be reliable. As we already noted, hospital comparisons are not the only purpose of the CPES. National assessments of patient experiences are supported by CPES and these data have been used to investigate variation and disparities in care between patient groups.24 25 For these uses that do not involve organisational comparisons, concerns about the lack of interunit reliability are not applicable. Furthermore, it can also be useful to know that all hospitals are performing above a target level even though we may not be able to distinguish between them.

There are various ways in which the survey could be changed in response to these findings. First, by redesigning the survey instrument or related reporting conventions. For example, questions where the variability between hospitals is very low could be considered as candidates for removal from subsequent survey waves as there is little point in classifying hospitals on aspects of care for which they have no tangible differences between them. A similar approach could be taken for questions where hospital performance is very high, although it may also be possible to add to or redesign the response options (or associated reporting conventions) to bring the mean reported scores closer to 50%, which will increase the reliability of these items. We do note that in both these situations, there is something to be celebrated as a lack of variability suggests equitable healthcare delivery and in the context of ‘ceiling’ effects, a high performance implies high-quality healthcare delivery. However, continued measurement of such aspects may not be the best use of patient survey resources. It is not without irony that the aims of quality improvement efforts underpinned by patient surveys are to improve service and reduce disparities, both of which reduce reliability and in turn reduce the usefulness of such survey items.

Another way by which reliability could be increased is to increase the sample size. Currently, the CPES sample consists of all patients treated in a particular 3-month period. If a whole year sample was used instead, we would have up to four times as many patients available. Our findings suggest that the vast majority of hospital-level scores in such a case would be reliable, though of course there would be an increase in cost of delivering the survey. Rather than continuing with the current ‘census’ approach (whereby all patients who fit eligibility criteria during the survey sampling period form part of the sampling frame), probability sampling could be used. This would mean surveying more patients than is currently done in hospitals treating small numbers of patients with cancer and fewer than currently done in those treating many patients with cancer, potentially having little impact on the total sample size. Indeed, the optimal design for a survey that puts equal importance on every hospital is an equal sample size for each hospital and fixed target respondent numbers per unit of assessment are already used in a number of NHS and international surveys.6 7 However, changing the length of the sampling window will likely impact the composition of responders as this is dictated by variation in treatment modalities, early mortality and non-response, the effect of which will depend on the sampling window.28 This in turn may impact the ability to compare results to those from previous years. An alternative approach of aggregating multiple years of survey results will also improve reliability, though it will reduce the timeliness of scores and potentially reduce the usability of the findings. Similarly, improvements in response rate can also increase the sample size, in turn improving reliability. The scope for improvement in this survey may be limited due to it already having a high response rate, but for other surveys that may not be true.

Conclusion

The English Patient Experience Survey represents a globally unique source for understanding experience of a patient with cancer; but in its present form, it is not reliable for high stakes comparisons of the performance of different hospitals. In profiling the survey, we have found that around two-thirds of hospital scores are not reliable. This severely hampers the use of this survey for hospital comparisons and raises questions over the suitability of its current design. Classifying hospitals as being a poor performer on an unreliable question may lead to unfair reputational loss and misplaced quality improvement efforts resulting in an opportunity cost. Classifying hospitals as high performers on unreliable questions may lead to false reassurance in related areas thus missing the opportunity for improvement. Redesigning the questions and sampling strategy used could dramatically improve the percentage of reliable hospital scores and thus making the survey far more useful.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the NHS England as commissioner of the 2016 Cancer Patient Experience Survey, Quality Health as data collector and publisher of the data set, all NHS Acute Trusts in England for provision of data samples and all patients who responded to the survey.

Footnotes

Contributors: GAA and GL conceived and designed the study. GA developed the methodological framework. MGC performed the analysis. All authors (GAA, MGC, TMP and GL) contributed to the interpretation of findings and the drafting of the manuscript. GA is guarantor for this paper.

Funding: This research was funded by Macmillan Cancer Support (grant number 5995414). GL is funded by a Cancer Research UK Advanced Clinician Scientist Fellowship award (grant number C18081/A18180). The work presented here represents that of the authors and does not necessarily represent those of the funding organisations.

Competing interests: The authors report grants from MacMillan Cancer Support, during the conduct of the study. GA and GL have acted as academic consultants providing methodological advice to NHS England Insight team regarding the Cancer Patient Experience Survey.

Ethics approval: This study is entirely based on publically available data and so ethical approval is not required. The actual survey was conducted by the survey providers after obtaining section 251 approval of the NHS Act 2006 and Health Service (Control of Patient Information) Regulations 2002.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The study is based entirely on publicly reported data as referenced in the text.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Raleigh V, Foot S. Getting the measure of quality: Opportunities and challenges, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Quality Watch. NHS & Social Care Quality Indicators - Data & Statistics. http://www.qualitywatch.org.uk/indicators (accessed 09 Jul 2018).

- 3. NHS Digital. Compendium of Population Health Indicators. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/ci-hub/compendium-indicators

- 4. Darzi A. Quality and the NHS Next Stage Review. The Lancet 2008;371:1563–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60672-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers & Systems (CAHPS). https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/CAHPS/ (accessed 07 Sep 2018).

- 6. Ipsos M. GP Patient Survey Results Released 2018. 2018. https://www.ipsos.com/ipsos-mori/en-uk/2018-gp-patient-survey-results-released.

- 7. Care Quality Commission. Adult inpatient survey 2017: Statistical release. 2018. https://www.cqc.org.uk/publications/surveys/adult-inpatient-survey-2017.

- 8. Abel G, Saunders CL, Mendonca SC, et al. Variation and statistical reliability of publicly reported primary care diagnostic activity indicators for cancer: a cross-sectional ecological study of routine data. BMJ Qual Saf 2018;27:21–30. 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Roland M, Elliott M, Lyratzopoulos G, et al. Reliability of patient responses in pay for performance schemes: analysis of national General Practitioner Patient Survey data in England. BMJ 2009;339:b3851 10.1136/bmj.b3851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lyratzopoulos G, Elliott MN, Barbiere JM, et al. How can health care organizations be reliably compared?: Lessons from a national survey of patient experience. Med Care 2011;49:724–33. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31821b3482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stocks SJ, Kontopantelis E, Akbarov A, et al. Examining variations in prescribing safety in UK general practice: cross sectional study using the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. BMJ 2015;351:h5501 10.1136/bmj.h5501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guthrie B, McCowan C, Davey P, et al. High risk prescribing in primary care patients particularly vulnerable to adverse drug events: cross sectional population database analysis in Scottish general practice. BMJ 2011;342:d3514 10.1136/bmj.d3514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Verburg IW, de Keizer NF, Holman R, et al. Individual and Clustered Rankability of ICUs According to Case-Mix-Adjusted Mortality. Crit Care Med 2016;44:901–9. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guglielminotti J, Li G. Monitoring Obstetric Anesthesia Safety across Hospitals through Multilevel Modeling. Anesthesiology 2015;122:1268–79. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Krell RW, Hozain A, Kao LS, et al. Reliability of risk-adjusted outcomes for profiling hospital surgical quality. JAMA Surg 2014;149:467–74. 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.4249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shih T, Dimick JB. Reliability of readmission rates as a hospital quality measure in cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;97:1214–8. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.11.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. van Dishoeck AM, Lingsma HF, Mackenbach JP, et al. Random variation and rankability of hospitals using outcome indicators. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:869–74. 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.048058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Henneman D, van Bommel AC, Snijders A, et al. Ranking and rankability of hospital postoperative mortality rates in colorectal cancer surgery. Ann Surg 2014;259:844–9. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sequist TD, Schneider EC, Li A, et al. Reliability of medical group and physician performance measurement in the primary care setting. Med Care 2011;49:126–31. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181d5690f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Quality Health. Guidance material and survey material. 2016. http://www.ncpes.co.uk/reports/2016-reports/guidance-material-and-survey-materials/3211-2016-cancer-survey-guidance/file

- 21. Quality Health. National Cancer Experince Survey 2016. Reports. Data tables. 2017. http://www.ncpes.co.uk/reports/2016-reports/local-reports-1/data-tables-1

- 22. Quality Health. Technical Documentation. 2016. http://www.ncpes.co.uk/reports/2016-reports/guidance-material-and-survey-materials/3210-2016-national-cancer-patient-experience-survey-technical-documentation/file

- 23. Barclay ME, Lyratzopoulos G, Greenberg DC, et al. Missing data and chance variation in public reporting of cancer stage at diagnosis: Cross-sectional analysis of population-based data in England. Cancer Epidemiol 2018;52:28–42. 10.1016/j.canep.2017.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. El Turabi A, Abel GA, Roland M, et al. Variation in reported experience of involvement in cancer treatment decision making: evidence from the National Cancer Patient Experience Survey. Br J Cancer 2013;109:780–787. 10.1038/bjc.2013.316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Saunders CL, Abel GA, Lyratzopoulos G. Inequalities in reported cancer patient experience by socio-demographic characteristic and cancer site: evidence from respondents to the English Cancer Patient Experience Survey. Eur J Cancer Care 2015;24:85–98. 10.1111/ecc.12267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Abel GA, Saunders CL, Lyratzopoulos G. Cancer patient experience, hospital performance and case mix: evidence from England. Future Oncol 2014;10:1589–98. 10.2217/fon.13.266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yu H, Mehrotra A, Adams J. Reliability of utilization measures for primary care physician profiling. Healthc 2013;1:22–9. 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2013.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Abel GA, Saunders CL, Lyratzopoulos G. Post-sampling mortality and non-response patterns in the English Cancer Patient Experience Survey: Implications for epidemiological studies based on surveys of cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol 2016;41:34–41. 10.1016/j.canep.2015.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-029037supp001.xlsx (254.2KB, xlsx)