Abstract

Objective

Epilepsy affects approximately 50 million people globally, with approximately 80% living in low/middle-income countries (LMIC), where access to specialist care is limited. In LMIC, primary health workers provide the majority of epilepsy care, despite limited training in this field. Recognising this knowledge gap among these providers is an essential component for closing the epilepsy treatment gap in these regions.

Setting

In Zambia, the vast majority of healthcare is provided by clinical officers (COs), primary health providers with 3 years post-secondary general medical education, who predominantly work in first-level health centres around the country.

Participants

With cooperation from the Ministry of Health, a total of 10 COs from 4 surrounding first-level health centres around the capital city of Lusaka participated, with 9 completing the entire course.

Intervention

COs were trained in a 3-week structured course on paediatric seizures and epilepsy, based on adapted evidence-based guidelines.

Results

Preassessment and postassessment were conducted to assess the intervention. Following the course, there was improved overall knowledge about epilepsy (69% vs 81%, p<0.05), specifically knowledge regarding medication management and recognition of focal seizures (p<0.05), improved seizure history taking and appropriate medication titration (p<0.05). However, knowledge regarding provoked seizures, use of diagnostic studies and general aetiologies of epilepsy remained limited.

Conclusions

This pilot project demonstrated that a focused paediatric epilepsy training programme for COs can improve knowledge and confidence in management, and as such is a promising step for improving the large epilepsy treatment gap in children in Zambia. With feasibility demonstrated, future projects are needed to expand to more rural regions for more diverse and larger sample of primary health provider participants and encompass more case-based training and repetition of key concepts as well as methods to improve and assess long-term knowledge retention.

Keywords: neurology, paediatrics, epilepsy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Demonstrates an effective strategy for training first-line providers with limited education on effective paediatric epilepsy management.

Provides a model for a feasible training strategy built with partnership within the healthcare system in the country, including the main academic tertiary centre and ministry of health, in order to create a sustainable referral system.

As a pilot project, the study was limited in sample size and geographical scope and only tested immediate improvement after training with modest effects seen.

Long-term retention was not measured in this project and needs to be assessed in future studies.

Direct impact on patient care practices was not measured.

Introduction

Approximately 50 million people around the world are affected by epilepsy,1 which includes 0.5%–1% of children globally.2 Out of those affected, an estimated 80% are living in the developing world.3–5 In Zambia, the prevalence of epilepsy is estimated to be as high as 14.6 per 1000.6 The burden is not only high in low/middle-income countries (LMIC) but also compounded by a persistently high treatment gap—the percentage of people who are not accessing medical care or on appropriate medication. The epilepsy treatment gap remains above 70%–80% across most of LMIC.7 This is despite epilepsy being a very treatable condition, with an estimated 70% of people achieving good seizure control on appropriate and cost-effective therapy, including the most common ones available in LMIC.4 Children are particularly a vulnerable population. In Zambia, children with epilepsy have been shown to have fewer educational opportunities, poorer nutrition and lower socioeconomic status than other children.8

One of the largest contributing factors to the paediatric epilepsy treatment gap is the significant shortage of child neurologists in the world, with increased disparity in LMIC and rural regions. The most recent data from the WHO reports that there are less than 0.4 per 100 000 child neurologists globally, with 0.02 per 100 000 in LMIC.9 As a result, up to 91% of neurological care is provided by paramedical providers who have variable education regarding neurological disorders.9 These providers include nurses, community health workers and clinical officers (COs) (primary care providers with 3 years of post-secondary school general medical education). While this model of care delivery is essential to cover the healthcare needs in these regions, it creates significant concerns about this level of non-specialist providers’ ability to appropriately recognise and manage neurological conditions due to limited training. Demonstrating this, a Zambian study showed that irrespective of the volume of people with epilepsy that primary healthcare workers had seen in the previous 3 months, the majority had less than adequate knowledge about seizure management.10

Programmes utilising algorithmic and module-based training for specialised care provided by the primary health worker have been shown effective not only to improve care but also to improve health seeking behaviours and awareness in communities.5 11–13 Examples of such programmes for active convulsive epilepsy have been shown successful in various regions of the world, including Kenya, where a 10% reduction in the epilepsy training gap was seen through a community education programme,14 and in Zimbabwe, where a programme for education of community health workers significantly improved health seeking and compliance among people with epilepsy.15 In Zambia, where the epilepsy treatment gap remains as high as 90% in some rural regions,7 and the accessibility of specialists is extremely limited, this is an important strategy to consider as an option for expanding care. Notably, however, such education programmes for epilepsy typically focus on a broad approach towards convulsive epilepsy, without any specific focus on children or the significant portion of more subtle epilepsies that can impact a child’s development.

Recognising the unique management needs of children with seizures, we developed an educational programme aimed at COs in Zambia, focusing specifically on paediatric epilepsy. This pilot project aimed to identify the necessary components for such a programme, assess feasibility and interest and demonstrate effectiveness in improving knowledge and comfort of providers in management of children with seizures and epilepsy.

Methods

Four peri-urban first-level health centres surrounding the capital city Lusaka were identified for participation in the epilepsy education programme based on population of children with epilepsy seen, ability to refer to the University Teaching Hospital and capacity to commit to the training. In 2017, the catchment population of the participating health centres ranged from 412 500 to 451 000.16 At the time of the training, none of the participating centres had a dedicated epilepsy or neurology clinic.

COs at each site were selected by clinic supervisors, based on interest, the likelihood that they would remain at their post within that centre for at least 1 year and ability to commit to the training. Gender and age did not play a role in selection. Due to the strong interest of the health centres and ministry of health in our training programme, there was strong commitment and availability of COs to attend the required period of training.

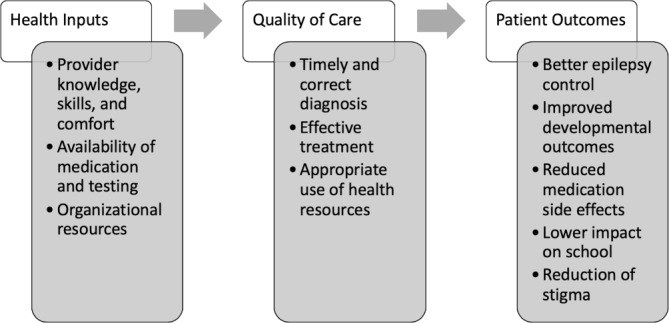

The training was conducted over a 3-week period by two board-certified paediatric neurologists (OC and AAP) during which period six modules were delivered. Each module was delivered on two separate days, allowing each CO two opportunities to attend the session in order to maximise completion rates. Out of the 10 COs who participated, 9 completed the entirety of the training. The objectives of the training were to improve provider knowledge about paediatric epilepsy in order to improve timeliness of management and utilisation or healthcare resources, with the ultimate goal of improving patient outcomes (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for improving quality of care and patient outcomes for children with epilepsy.

The teaching materials for this course were drawn from established national and international guidelines and resources, including WHO and International League Against Epilepsy materials, and were adapted for the management of children in Zambia.17 18 All materials were designed to provide a reasonable knowledge base for the level of a non-specialist provider, with focus on practical application in the primary level setting. All materials were developed by two child neurologists with additional expertise in epilepsy and experience in Zambia (OC, AAP) and additionally reviewed and edited to be appropriate for the level of CO education by a trained CO working in our paediatric epilepsy clinic in Zambia (OT).

The six educational modules included the following:

Module 1: Basic neuroanatomy, seizure pathophysiology, epidemiology of seizures/epilepsy in children with epilepsy (CWE) in sub Saharan Africa

Module 2: Basic paediatric neurology history and physical exam

Module 3: Seizure semiology (video based); other paroxysmal events that can mimic seizures in children

Module 4: Diagnosis and management of acute/provoked seizures, status epilepticus and first unprovoked seizures

Module 5: Diagnosis and management of epilepsy in children, basics of childhood epilepsy syndromes

Module 6: Follow-up of CWE, comorbid conditions in CWE, psychosocial impact of epilepsy

In addition to the formal training modules, open case discussions were held, without any patient identifiers, to encourage practical application of the education. After completion of post-assessments, one of the child neurologists (AAP) visited each clinic where pairs of the COs (6/9) were observed during a patient session to see direct implementation of the training in practice. During these observed sessions, continued guidance and management was provided as each case was reviewed directly. These sessions were not objectively reviewed for assessment of training, but rather utilised for feedback of identifying strengths and weaknesses of the training programme for future iterations.

The intervention effectiveness was assessed by a 24-item knowledge assessment and 10-item confidence survey, given both before module delivery and at the completion of the training programme. The knowledge assessment contained 17 multiple choice questions based on the established teaching materials and guidelines, and the participants were directed towards common management decisions in caring for children with epilepsy, including identification of seizure types common in children based on case description, appropriate antiepileptic medication selection for seizure type and diagnostic and referral decision points. It also included seven true and false questions assessing beliefs regarding epilepsy (such as ability of children with epilepsy to go to school, seizures being caused by spirits and other common societal beliefs). The 10-item confidence assessment rated using a 10-point scale evaluated the general comfort in items such as treating seizures, prescribing medications, managing status epilepticus and providing seizure safety guidance. Preassessment and postassessment group scores were compared. Data was analysed using Stata v.14 software using paired t-test analysis. The methodology for this quality improvement project follow SQUIRE guidelines.19

Patient and public involvement

No patients were directly involved in this study.

Results

A total of nine COs successfully completed the entire training course. There were six women and four men initially enrolled with one man not completing the programme.

Knowledge assessment results are depicted in table 1. Overall, there was a significant improvement in knowledge scores between the preintervention and postintervention assessments, with participants answering 68.8% of multiple-choice questions correctly prior to training, compared with 80.6% correct following training (p<0.001). The most notable improvements were seen in the improvement in ability to identify a focal seizure with altered awareness (by case description), improving from 50% of participants in the pretest to 100% in the post-test (p=0.015). In addition, prior to training, only 60% of participants correctly indicated that they would increase the dose of anti-seizure medication in order to reach therapeutic effect; following training 100% of participants answered correctly (p=0.037).

Table 1.

Knowledge assessment results

| Question | Pre-test (% of participants answered correct) | Post-test (% of participants answered correct) | P value* |

| Seizures are caused by abnormal electrical activity | 100 | 100 | – |

| Epilepsy is defined as >2 unprovoked seizures | 100 | 100 | – |

| Identifying developmental delay | 90 | 90 | – |

| Seizure first aid | 70 | 100 | 0.081 |

| Identifying absence seizures | 100 | 100 | – |

| Identifying myoclonic seizures | 90 | 100 | 0.343 |

| Identifying generalized tonic clonic seizures | 100 | 100 | – |

| Identifying syncope | 70 | 70 | – |

| Identifying focal seizures | 50 | 100 | 0.015 |

| Treat focal seizures with carbamazepine | 40 | 80 | 0.168 |

| Treat generalised seizures with sodium valproate | 50 | 70 | 0.224 |

| Treat infantile spasms with prednisolone | 10 | 30 | 0.343 |

| Increase the dose of an antiepileptic drug (AED) to reach therapeutic effect | 60 | 100 | 0.037 |

| Add a second AED when a single AED is at max dose | 40 | 60 | 0.509 |

| No imaging or medication for a simple febrile seizure | 40 | 50 | 0.591 |

| Obtain imaging for a complex febrile seizure | 80 | 20 | 0.005 |

| Give diazepam for status epilepticus | 90 | 100 | 0.343 |

| Epilepsy is not contagious | 100 | 100 | – |

| Epilepsy cannot be caused by witchcraft | 90 | 100 | – |

| A child with epilepsy can go to school | 100 | 100 | – |

| An adult with epilepsy can go to work | 100 | 100 | – |

| Should not drive if has had a seizure recently | 70 | 90 | 0.343 |

| People with epilepsy can get married and have kids | 100 | 100 | – |

| Traditional remedies can have negative effects | 90 | 90 | – |

Although not statistically significant due to the small sample size, there was a notable trend of improvement in selecting an appropriate antiepileptic based on seizure description, with a correct response rate improvement from 40% to 80% for using carbamazepine as first choice for focal seizures and 50%–70% for using sodium valproate first for generalised seizures (presented in clinical scenarios in which these were best first-line options). Also notable was that 90% of participants were unfamiliar with the treatment of infantile spasms with steroids (prednisolone available in Zambia) prior to training, with a 20% improvement after completion.

Improvement of febrile seizure management was not seen during this course, despite content review on the topic. Both prior to and following training, about half of participants could not correctly identify that neither imaging nor medication is necessary for a simple febrile seizure. Notably, we also found that prior to training 80% of participants responded correctly to obtain neuroimaging in clinical scenario depicting a child with focal seizures in the setting of fever, but after training only 20% did.

In both pretraining and post-training assessments, almost all participants responded that they believed epilepsy is not contagious, recognised it as a medical condition and reported that individuals with epilepsy can attend school, work and have children.

In the confidence assessments (table 2), there were significant improvements in participant comfort with most aspects of management, particularly in taking a history to identify characteristics of seizures (p=0.015), knowing when to prescribe medication (p=0.002), selecting which medication to use (p=0.000), changing medications (p=0.001), treating status epilepticus (p=0.001), providing guidance about side effects (p=0.000), answering caregivers’ questions (p=0.011) and providing safety guidance (p=0.002). Comfort with the identification of causes of seizures was reported as still limited, and participants reported that they desired more knowledge about epilepsy, both theoretical as well as practical application, continuing to express the lack of neurological education exposure that they received in general.

Table 2.

Comfort assessment results

| Comfort and confidence measures | Pretest average | Post-test average | P value* |

| Comfort treating children with epilepsy | 5.7 | 7.8 | 0.177 |

| Differentiating seizures and other events | 6.8 | 8.8 | 0.027 |

| Asking questions about characteristics of seizures | 7.4 | 9.1 | 0.015 |

| Focal versus generalised seizures | 6.2 | 9.3 | 0.007 |

| Deciding when to obtain images or tests | 6.5 | 8.9 | 0.037 |

| Identifying the cause of seizures | 6.2 | 8.3 | 0.116 |

| Knowing when to prescribe medication | 6.5 | 9.0 | 0.002 |

| Selecting which medication to use | 5.7 | 9.0 | 0.000 |

| Changing medication dose or adding medication | 4.4 | 8.7 | 0.001 |

| Treating status epilepticus | 6.4 | 9.3 | 0.001 |

| Providing guidance about side effects | 5.9 | 8.7 | 0.000 |

| Answering families' questions | 6.7 | 9.1 | 0.011 |

| Providing safety guidance to patients | 6.8 | 9.8 | 0.007 |

Significant p values were bolded.

Discussion

Our pilot education programme for paediatric epilepsy in Zambia demonstrated the feasibility of this type of structured educational intervention for primary health providers in our setting. Using proven strategies of shifting care of a condition traditionally managed by a specialist to primary health providers in limited resource regions via a focused education and algorithmic approach,5 14 20 we demonstrated that similar methods could be effective for paediatric epilepsy through a focused programme for basic level providers.

Through our programme, participating COs gained significant confidence in management of epilepsy in children, had improved recognition of the specific impact that seizures can have on a child’s development, improved in how to optimise medications available and learnt how to conduct a proper and efficient paediatric neurology history and physical exam for a general provider’s level to guide management and referral when indicated. Furthermore, a significant interest in improving paediatric epilepsy care has been raised throughout the participating COs, as well as their health centres and the Ministry of Health as a result of this programme, with cooperation for future trainings assured.

The overall concept was successful in execution, yet there were notable limitations. Due to the fact that this was a test of feasibility for this specific education module, our sample size was necessarily small and limited to the urban area of the Lusaka region. The small sample size and the short time frame of outcome assessments limited full assessment of the true impact on provider practice change. In addition, utilising centres that were all within the Lusaka region is also a limitation as the challenges of care—including more limited knowledge of basic paediatrics and neurology and access to medication and diagnostics—are significantly more complicated in the more rural regions.

Our pilot project had additional limitations, including the lack of objective measurement of the impact of the intervention, due to logistical challenges. The knowledge assessment used, which consisted primarily of case-based questions, is continuing to be utilised in future expansions of this study, and therefore has not been included in this paper. However, we acknowledge that use of a written exam to assess provider’s improvement in epilepsy management is not fully effective to judge change in care practices and further monitoring and evaluation methods to overcome these for future education interventions is essential to fully assess the impact of this type of programme.

Therefore, although the content of the education programme was assessed to the best of our ability as appropriate for this setting, further informal review among COs across the country of varying levels of experience and knowledge has revealed that more repetition and hands on training is required for truly effective training. Elements of these issues were reflected in our results of this study, where we interestingly found some COs could be trained to recognise specific seizure types and epilepsy syndromes, yet they did not gain ability to apply knowledge of more simple concepts that were crucial to care, such as recognising provoked versus unprovoked seizures and utility of diagnostic testing based on focal versus generalised semiology. Of note, the specific weakness in worsening of provoked seizure management seen after our training was not felt to be a result of our training, but rather further demonstration of lack of knowledge on recognising and managing provoked seizures in general, and difficulty in understanding this concept despite the training. Feedback from participants has revealed this to be one of the most challenging concepts for them to grasp. This further serves to demonstrate the need for increased repetition and case-based learning for effective education.

We also found that when focusing on the paediatric history and physical exam, utilising a clear assessment tool that was simplified and captured basic exam techniques relevant to our purposes was the most effective. Finally, we have found that the COs struggled to implement their acquired knowledge if trained in isolation as the knowledge gap on management of seizures and epilepsy in children is a problem across providers, and inclusion of nurses and general medical officers (to whom the COs must report to if they want to refer a child) as part of an epilepsy team within the participating health centres will be essential for effective implementation of these trainings in the future.

Interestingly, in assessing for any incorrect misconceptions and personal bias against those with epilepsy, objectively on our assessments we found no evidence of this even before the training. However, during open case discussions, there were clear elements of societal beliefs which persisted, including that of a diagnosis of epilepsy meaning one could no longer contribute to the family, often would not go to school and would continue to struggle in the community. Providers were more open about sharing these concerns, even expressing that they personally held them in certain instances, when it was done in a more informal setting, leading us to believe that this data would be better ascertained from a focus group mechanism in the future.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first in-depth training of this kind in Zambia which focuses specifically on seizures and epilepsy in children, taking into account the special needs of this population.

Overall, our results have identified that our model of training can be successful. However, improvements focused on increased hands on clinical training, increased repetition of core concepts and inclusion of participants in multiple roles in the first-level health system across both urban and rural settings is necessary. For future trainings, a plan for follow-up knowledge assessments and an online platform for continued education and formation of a community of epilepsy providers across the country is also being developed.

This model is unique from the majority of epilepsy education programmes that primarily combine adult and paediatric populations and focus on active convulsive epilepsy alone. We argue that this is an important distinction as focus on active convulsive epilepsy alone may miss a significant period of time for intervention in many children in a region where the seizures are often focal and can be subtle at onset,21 and these delays in treatment can cause significant impairments in development which may have been reducible if not preventable by appropriate early epilepsy management.22

We recognise that the training of providers at multiple levels will be required—that of paramedical providers, general medical doctors, paediatricians and ultimately training of paediatric neurologists—for a sustainable system of timely management and appropriate referrals. The Paediatric Epilepsy Training courses developed by the British Paediatric Neurology Association are one of the few existing paediatric epilepsy training programmes for non-specialist providers and are an excellent option for 1 day courses to improve knowledge broadly in the management of paediatric epilepsy for paediatricians and general medical doctors with a good basic knowledge.23 Programmes like this cannot sufficiently target the primary level provider who require more extensive training as our programme aims to do, but it can help expand the referral system, strengthening knowledge of providers in every level of the health system for consistent care quality. Furthermore, at the time of this manuscript, an initiative for the first specialty training programme for neurologists had just been launched in Lusaka, with two trainees enrolled for child neurology. While this provides new hope for access to specialist care in Zambia, the large burden of epilepsy will continue to require care improvement at all levels, beginning with the first-line providers as we have elected to do so in this initiative.

Conclusions

Overall, this study demonstrated that education on paediatric epilepsy can be effectively delivered to primary care providers in Zambia, with improved knowledge outcomes as well as greater confidence in epilepsy knowledge. Given the lack of specialists in the region, this type of education-based intervention targeting primary health providers may significantly improve neurological outcomes, as these providers are involved in the earliest points of care for children with epilepsy. Further expansion of the training across different first-level health centres, with incorporation of methods to objectively measure practice change and knowledge retention, will be required to better assess the long-term impact of these measures on the epilepsy treatment gap.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Chipepo Kankasa for donating a venue for the lectures and staff time for participation, Chipo Bucheba, Kateule Banda, Edna Mwaanga and Pezo Mumbi for their support in coordination of lectures, Dr Maitreyi Mazumdar for her guidance and the Boston Children’s Hospital Global Health Program for the funding support provided. We would also like to thank the participating health centers: Chipata First Level Hospital, Mandevu Primary Health Centre, Matero First Level Hospital and Chilenje First Level Hospital.

Footnotes

Contributors: AAP is the principal investigator for this project, contributing to design, obtaining of funding and ethical approvals, development of training materials and implementation and development and editing of the manuscript. OC is the co-principal investigator, contributing to project design and development, coordination with local teams in Zambia, development of training materials and implementation and development and editing of the manuscript. LW is a research assistant who helped in data collection and analysis, as well as development and edits of the manuscript. OT is a research assistant who helped in development of training materials and data collection. PK is a research assistant who helped in project coordination on site. MM helped with local coordination and partnership development in Zambia, project development and edits to the manuscript.

Funding: Funding provided by Boston Children’s Hospital Global Health Program Project Grant.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained through the Boston Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board and University of Zambia Biomedical Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Collaborators GE. GBD 2016 Epilepsy Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of epilepsy, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol 2019;18:357–75. 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30454-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aaberg KM, Gunnes N, Bakken IJ, et al. Incidence and prevalence of childhood epilepsy: a nationwide cohort study. Pediatrics 2017;139:e20163908 10.1542/peds.2016-3908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Espinosa-Jovel C, Toledano R, Aledo-Serrano Á, et al. Epidemiological profile of epilepsy in low income populations. Seizure 2018;56:67–72. 10.1016/j.seizure.2018.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Newton CR, Garcia HH. Epilepsy in poor regions of the world. The Lancet 2012;380:1193–201. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61381-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Watila MM, Keezer MR, Angwafor SA, et al. Health service provision for people with epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa: a situational review. Epilepsy Behav 2017;70:24–32. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2017.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ba-Diop A, Marin B, Druet-Cabanac M, et al. Epidemiology, causes, and treatment of epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Neurol 2014;13:1029–44. 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70114-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Birbeck GL, Chomba E, Mbewe E, et al. The cost of implementing a nationwide program to decrease the epilepsy treatment gap in a high gap country. Neurol Int 2012;4:14 10.4081/ni.2012.e14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chomba E, Haworth A, Atadzhanov M, et al. The socioeconomic status of children with epilepsy in Zambia: implications for long-term health and well-being. Epilepsy Behav 2008;13:620–3. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Organization WFoNaWH. Atlas: country resources for neurologic disorders, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chomba EN, Haworth A, Atadzhanov M, et al. Zambian health care workers' knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and practices regarding epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2007;10:111–9. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2006.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chin JH. Epilepsy treatment in sub-Saharan Africa: closing the gap. Afr Health Sci 2012;12:186–92. 10.4314/ahs.v12i2.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kale R. The treatment gap. Epilepsia 2002;43(Suppl.6):31–3. 10.1046/j.1528-1157.43.s.6.13.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mbuba CK, Ngugi AK, Newton CR, et al. The epilepsy treatment gap in developing countries: a systematic review of the magnitude, causes, and intervention strategies. Epilepsia 2008;49:1491–503. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01693.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Radhakrishnan K. Challenges in the management of epilepsy in resource-poor countries. Nat Rev Neurol 2009;5:323–30. 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Adamolekun B, Mielke JK, Ball DE. An evaluation of the impact of health worker and patient education on the care and compliance of patients with epilepsy in Zimbabwe. Epilepsia 1999;40:507–11. 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb00749.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Central Statistical Office. Zambia in figures 2018, 2018. (published Online First: July 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 17. Organization WH. Mental health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) intervention guide, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18. WHO. ILAE/IBE/WHO global campaign against epilepsy: a manual for medical and clinical officers in Africa, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ogrinc GDL, Goodman D, Batalden P, et al. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Qual Saf 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bouchonville MF, Hager BW, Kirk JB, et al. Endo echo improves primary care provider and community health worker self-efficacy in complex diabetes management in medically underserved communities. Endocr Pract 2018;24:40–6. 10.4158/EP-2017-0079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wilmshurst JM, Kakooza-Mwesige A, Newton CR. The challenges of managing children with epilepsy in Africa. Semin Pediatr Neurol 2014;21:36–41. 10.1016/j.spen.2014.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Berg AT, Loddenkemper T, Baca CB. Diagnostic delays in children with early onset epilepsy: impact, reasons, and opportunities to improve care. Epilepsia 2014;55:123–32. 10.1111/epi.12479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kirkpatrick M, Dunkley C, Ferrie C, et al. Guidelines, training, audit, and quality standards in children’s epilepsy services: closing the loop. Seizure 2014;23:864–8. 10.1016/j.seizure.2014.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.