Abstract

Introduction

Successful ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) management is time-sensitive and is based on prompt reperfusion mainly to reduce patient mortality. It has evolved from a single hospital care to an integrated regional network approach over the last decades. This prospective study, named the China STEMI Care Project (CSCAP), aims to show how implementation of different types of integrated regional STEMI care networks can improve the reperfusion treatment rate, shorten the total duration of myocardial ischaemia and lead to mortality reduction step by step.

Methods and analysis

The CSCAP is a prospective, multicentre registry study of three phases. A total of 18 provinces, 4 municipalities and 2 autonomous regions in China were included. Patients who meet the third universal definition of myocardial infarction and the Chinese STEMI diagnosis and treatment guidelines are enrolled. Phase 1 (CSCAP-1) focuses on the in-hospital process optimisation of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) hospitals, phase 2 (CSCAP-2) focuses on the PPCI hospital-based regional STEMI care network construction together with emergency medical services and adjacent non-PPCI hospitals, while phase 3 (CSCAP-3) focuses on the whole-city STEMI care network construction by promoting chest pain centre accreditation. Systematic data collection, key performance index assessment and subsequent improvement are implemented throughout the project to continuously improve the quality of STEMI care.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has been reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University First Hospital. Ranking reports of quality of care will be generated available to all participant affiliations. Results will be disseminated via peer-reviewed scientific journals and presentations at congresses.

Trial registration number

Keywords: accreditation, chest pain center, network, reperfusion, ST-elevation myocardial infarction

Strengths and limitations of this study.

China ST-elevation myocardial infarction Care Project (CSCAP) is the first project focuses on establishing an integrated regional ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) care network in China through in-hospital process optimisation, primary percutaneous coronary intervention hospital-based regional STEMI care network construction and whole-city STEMI care network construction step by step, which will help us to understand the situations extensively and then improve accordingly.

Evaluation, feedback and improvement system will be established, aiming to provide a tailored and continuous quality of care improvement plan based on the conditions of different regions to further integrate the STEMI care network nationwide.

Hospitals are not randomly selected in CSCAP which might be lead to lack of representatives to some degree. However, these hospitals are at a high level in their region which is suitable to be core centres for regional network construction. Their experiences could be valuable for hospitals in the same region but not in this study.

Introduction

The burden of cardiovascular diseases is increasing and posing a major public health issue worldwide. The number of new onset of myocardial infarction will be tremendous in China in the next 15 years with the increasing risk factors and ageing population.1 The Chinese cardiovascular report in 2017 has shown an increase in both the percentage of hospitalisation and mortality of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) over the years. The trends of fast growth nationwide as well as higher AMI mortality in rural areas were observed since 2005 and 2013, respectively.2

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), mainly caused by a sudden obstruction of the coronary artery with thrombus, benefits from both increasing reperfusion rate and shortening of the duration from the symptom occurrence to the opening of the target vessel.3 4 Although implementing an evidence-based medicine significantly improves the prognosis of patients with STEMI, the gap of clinical application is still large in real-world settings.5 A majority of Chinese STEMI patients miss the optimal treatment timing due to restrictions from both patients and medical services.6 7 Additionally, the ratio of STEMI reperfusion treatment remained at the level of around 55% in the last decade. Hence, in-hospital mortality has not changed significantly yet.7

Successful treatment of STEMI is a systemic issue, and the solution is neither a novel thrombolytic drug nor an intervention device. It can be brought about by comprehensive factors, including the patients’ health awareness, physician’s skill, physician–patient’s relationship, medical reimbursement system, prehospital emergency medical system (EMS), in-hospital treatment, connection mechanism between prehospital and in-hospital care and posthospital management. Experiences from both the American Lifeline program and the European Stent—Save a Life can be used for reference. The quality of medical care can be significantly improved by establishing a regional STEMI care network through close collaboration between hospitals of different levels and EMS.8 9

Although large-scale studies have been conducted in China, such as clinical pathways for acute coronary syndromes in China focusing on the acute coronary syndrome (ACS) clinical pathway, Cardiovascular Disease in China focusing on the in-hospital treatment of ACS, China Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry focusing on the management of both STEMI and non-STEMI and China Patient-centered Evaluative Assessment of Cardiac Events Retrospective Study of Acute Myocardial Infarction, none of them focused on establishing a regional STEMI care network.7 10–12 Serial documents issued by the National Health Commission of China provide favourable government supports and further emphasise the important rolls of administrative departments of healthcare at all levels in strengthening the construction of regional emergency care network.13–15

China has gradually increased the input of medical expense in the last few decades. However, there are several types of medical insurances with different reimbursement policy in China. The impacts of health economic factors as well as geographical and humanistic factors on quality of STEMI care also need to be discussed.

Objectives

The 10-year project, named as China STEMI Care Project (CSCAP), aims to show how implementation of different types of integrated regional STEMI care networks can improve the reperfusion treatment rate, shorten the total duration of myocardial ischaemia, and lead to mortality reduction step by step. It will also provide useful information when building up a STEMI care network in other similar regions. In details, CSCAP focuses on improving the awareness of health and emergency treatment for patients with STEMI, increasing the ratio of reperfusion treatment, shortening the overall duration of myocardial ischaemia and implementing standard secondary prevention to improve the long-term prognosis by establishing and optimising medical care evaluation, feedback and improvement system with data support.

Methods and analysis

Study design

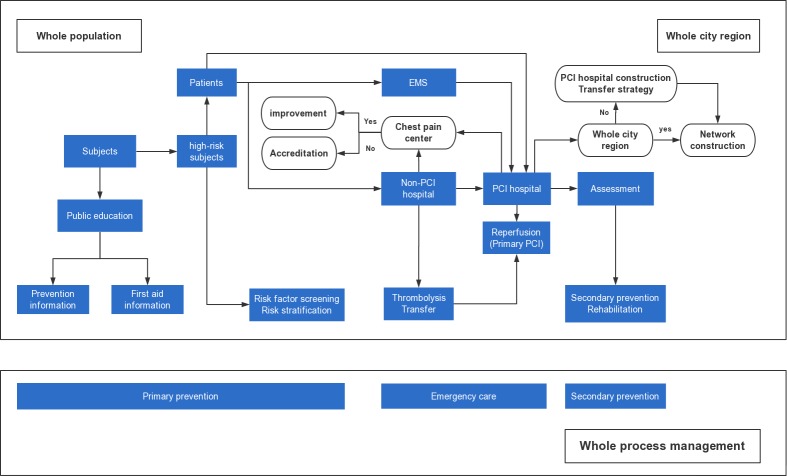

CSCAP is a prospective multicentre registry containing three phases. Phase 1 of CSCAP (CSCAP-1) focuses on the in-hospital process optimisation of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) hospitals. Phase 2 of CSCAP (CSCAP-2) focuses on the PPCI hospital-based regional STEMI care network construction with their adjacent non-PPCI hospitals and EMS. Phase 3 of CSCAP (CSCAP-3) focuses on the whole-city STEMI care network construction by promoting chest pain centre (CPC) accreditation (figure 1). Systematic data collection, assessment of quality of care and subsequent improvement are implemented throughout this study to continuously improve the quality of care.

Figure 1.

CSCAP whole-city STEMI care network construction. CSCAP, China ST-elevation myocardial infarction Care Project; EMS, emergency medical system; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Organisational framework

CSCAP was established by the Chinese Medical Doctor Association and supported by the National Health Commission of China in 2011. After collaborating with the European Stent—Save a Life in CSCAP-3, China became its member country in 2017. The project office, executive committee and steering committee were set up for the purposes of management, implementation and academic support. Data management and statistical analyses were conducted by the School of Public Health of Peking University.

Site selection

CSCAP included 18 provinces (Anhui, Fujian, Gansu, Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan, Hebei, Heilongjiang, Henan, Hubei, Jiangsu, Liaoning, Shandong, Shanxi, Shaanxi, Sichuan, Yunnan and Zhejiang), 4 municipalities (Beijing, Chongqing, Shanghai and Tianjin) and 2 autonomous regions (Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang) in China when considering incidence of STEMI, logistic as well as economic issues.

A total of 53 tertiary hospitals qualified for PPCI in 10 provinces, 2 municipalities and 2 autonomous regions of China were enrolled in CSCAP-1. The qualification of these selected hospitals was based on the numbers of PCI cases and cardiovascular interventionists extracted from the national PCI registry database. Moreover, all of them are able to provide 24/7 PPCI service. These hospitals were selected because they were at the top level in their city and potentially a hub for regional network construction in CSCAP-2. A total of 244 PCI hospitals with adjunct non-PCI hospitals from 18 provinces, 4 municipalities and 2 autonomous regions were selected to build up the regional STEMI care network in CSCAP-2. A total of seven cities (Harbin, Hangzhou, Nanning, Qingdao, Shenzhen, Suzhou and Taiyuan) from 6 provinces and one autonomous region with different EMS types were selected to build up the whole-city STEMI care network in CSCAP-3.

Patient enrolment

Patients who met with the third universal definition of myocardial infarction and the Chinese STEMI diagnosis and treatment guidelines were enrolled.16 17 STEMI patients with late admission to hospitals were also considered for the purpose of exploring optimal methods to shorten total ischaemic time causing by both patient and system delay. All patients received routine clinical assessments and treatments without any experimental intervention. The updated guideline-directed management such as reperfusion, auxiliary device implementation, elective revascularisation, medications and therapeutic lifestyle change will be implemented during the whole study period.

In CSCAP-1, a total of 4191 hospitalised patients, with symptom onset within 12 hours regardless of whether receiving reperfusion or symptom onset within 12–24 hours but still need PPCI, were enrolled consecutively in 2012. In CSCAP-2, a total of 20 799 patients with STEMI occurrence within 30 days regardless of reperfusion were enrolled consecutively from PPCI hospitals three times at a 6-month interval from 2015 to 2017. In CSCAP-3, a total of 30 hospitalised STEMI patients with symptom onset within 30 days will be enrolled consecutively from both PCI and non-PCI hospitals in the whole-city network every 3 months. Those patients who survived after hospital discharge will be followed up for 1 year.

Regional network construction

An integrated regional network contains PCI hospitals, non-PCI hospitals and EMS. There are three major types of EMS in China: (1) independent EMS, which has its own ambulances; (2) commanding EMS, which does not have its own ambulances and uses hospital ambulances and (3) affiliated EMS, which is based in hospitals and uses their ambulances. Due to these comprehensive situations, patients may not be transported to optimal hospitals to receive effective treatment in the shortest period because of incomplete communication.18 Thus, prehospital information transmission should be considered accordingly for hospital alert and rapid and accurate transfer.

Although PPCI is the most effective treatment for STEMI, it is difficult to be implemented in most of the primary hospitals, as they are limited by medical condition, geographical location and techniques. Early thrombolysis and/or transfer PCI strategy are the priority in these hospitals. Therefore, rapid identification of STEMI and referral to a hospital with PPCI ability are extremely important components in establishing a regional STEMI care network in China.

Optimising the in-hospital green channel can significantly shorten the door-to-balloon (D2B) time and door-to-needle (D2N) time, while establishing a CPC to integrate multiple resources is one of the most important methods.19 20 Traditional CPC focuses on the optimisation and integration of the in-hospital sources aiming to shorten the time of the process. The medical system and patient factors together determine the delay in STEMI emergency treatment.21 The concept of a modern CPC expands to establishing an effective regional network aiming to shorten the total ischaemia duration, thereby maximising the advantage of reperfusion therapy. The CPC independent accreditation in China was initiated in 2013 and two types of accreditation standards were developed according to PPCI ability.22 23

Procedures

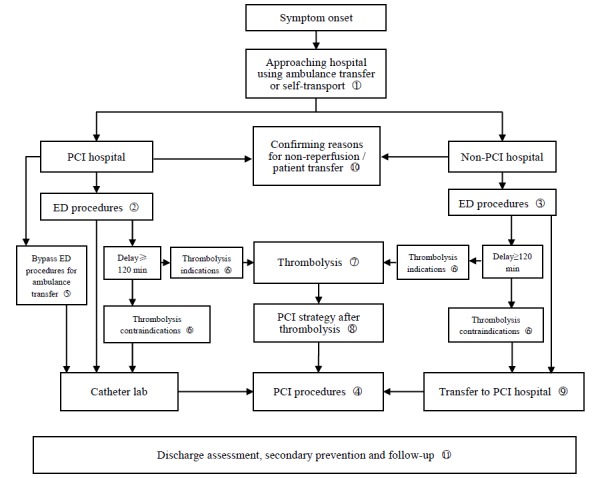

The treatment process of patients suffered STEMI was based on the STEMI protocol in the Announcement of Improving Medical Emergency Treatment Performance of Acute Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Diseases issued by the National Health Commission of China in 2015.15 Briefly, this flow chart included 1 centre (EMS), 2 types of hospitals (PCI and non-PCI), 3 types of transfer methods (EMS transfer to hospital, bypass emergency department (ED) and inter-hospital transfer) and 11 clinical pathways. Different clinical pathways were selected to execute the optimal emergency treatment based on the approaching time, method and hospital ability (figure 2). In addition, the procedures should be launched without results of myocardial biomarkers according to typical ischaemic symptoms and ECG.

Figure 2.

CSCAP STEMI emergency care flow chart. CSCAP, China ST-elevation myocardial infarction Care Project; ED, emergency department; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Data collection and management

Data of all treatment process were collected, including patient general information, prehospital treatment, in-hospital management and follow-up management (table 1). Considering the real situation in ED, many time points could not be recorded manually on time which might lead to missing and inaccurate data. Mobile device app can record these time variables through a simple click and complete the prehospital ECG transmission. In addition, the technique of data auto-capture becomes more and more popular at present and should resolve this issue. All of these methods are considered gradually in this study.

Table 1.

China ST-elevation myocardial infarction Care Project data elements

| Category | Example elements |

| Patient baseline information | Demographics (age, sex, ethnicity, region, occupation, marriage status and medical insurance type). Risk factors (smoking status, BMI, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, chronic kidney disease, peripheral artery disease, MI history, stroke history and prior revascularisation). Clinical presentation (blood pressure, heart rate and cardiac function classification). |

| Prehospital information | Patient (symptoms, symptom-onset time and hospital approaching method). EMS (response time, transfer process, first medical contact time, first ECG time, ECG transmission ratio and bypass ED ratio). Non-PCI hospital (hospital approaching method, first medical contact time, admission time, first ECG time, diagnosis time, consent time, reperfusion and other treatment, DI-DO time and transfer process). |

| PCI hospital information | Reperfusion (methods, indication and contraindication, and non-reperfusion reasons). Treatment delay (hospital approaching method, first medical contact time, bypass ED ratio, admission time, first ECG time, catheter lab ready time, consent time, D2B, D2N, FMC2B, FMC2N, total ischaemic time and reasons of delay). PCI procedures (operative route, coronary angiography results, aspiration, culprit vessels, stent and elective PCI). Thrombolytic procedures (thrombolytic agent, dose and outcome). Medications (loading dose DAPT and statin, antiplatelets, β-blockers, statin, ACEI/ARB, GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor and anticoagulant with dose and contraindication information). Laboratory results (troponin, CK-MB, creatinine, HbA1c, fasting glucose, BNP or NT-proBNP, lipid profiles, ECG and UCG). Discharge (diagnosis, in-hospital duration, expense and medications). Outcomes (death, non-fatal reinfarction, non-fatal stroke, revascularisation, mechanical complication and bleeding). |

| Follow-up and management | Presentation status (symptom, cardiac function classification, blood pressure, heart rate and follow-up on-time ratio). Laboratory results (lipid profiles, glucose traits, HbA1c, creatinine, haemoglobin, BNP or NT-proBNP, ECG and UCG). Medications (antiplatelets, β-blockers, statin and ACEI/ARB). Risk factor control rate (blood pressure, lipid, glucose and smoking cessation). Outcomes (death, non-fatal reinfarction, non- fatal stroke, revascularisation, rehospitalisation due to unstable angina pectoris, heart failure or other cardiovascular reasons and bleeding). |

ACEI, ACE inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; CK-MB, creatine kinase muscle/brain isoenzyme; D2B, door to balloon; D2N, door to needle; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; DI–DO, door in–door out;ED, emergency department; EMS, emergency medical service; FMC2B, first medical contact to balloon; FMC2N, first medical contact to needle injection; GP IIb/IIIa, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa; HbA1c, glycosylated haemoglobin A1c; MI, myocardial infarction; NT-ProBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; UCG, ultrasound cardiogram.

Data were inputted into a self-built electronic database together with two existing databases of both CPC accreditation and national PCI registry by trained clinical research coordinators and clinicians in each hospital. The quality of the data was monitored and suspicious contents with missing, outlier and logical errors were mainly reviewed. When all problems are resolved, the database is then locked for statistical analysis.

The describing method was used in CSCAP to mainly rank data quality and medical quality. Continuous variables were described as mean (SD) or median (IQR), while categorical variables were described as a percentage. Multivariate regression model was used to evaluate the factors related to the assessment of medical quality. The Cox model was used to analyse the association between exposures and medical outcomes. A p<0.05 was defined as a significant difference. All analyses were performed using R (http://www.R-project.org).

Key performance index

The National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR), established since 1997, has become the basis for project implementation and quality evaluation as well as medical quality improvement of research centres in the USA. It has a positive impact on clinical practice, medical payment, clinical research and government decision-making.24 25 The present study referred to the NCDR model to optimise the STEMI quality of care and established an evaluation, feedback and improvement system for primary key performance indexes(KPIs). For KPI selection, PPCI hospitals focused on the improvement in the PPCI capacity and efficiency, non-PPCI hospitals focused on the improvement in rapid diagnosis, thrombolysis and referral capacity to PPCI hospitals, and EMS focused on the improvement in information transmission to alert hospitals early for rapid and accurate transfer.

A total of 13 primary KPIs were selected for medical quality evaluation based on different roles of EMS and hospitals in STEMI management (box 1). However, different treatment delay indexes were used in different phases according to the progress of network construction. D2N and D2B time, defined as in-hospital FMC to target vessel open, were used to evaluate in-hospital delay in CSCAP-1. First medical contact-to-balloon time and first medical contact-to-needle time, defined as FMC by emergency system or hospital to target vessel open, were used to evaluate the whole medical system delay in CSCAP-2. Total ischaemic time, defined as symptom onset to target vessel open, is used in CSCAP-3 to add the information of patient delay.

Box 1. Primary performance measures for evaluating medical care quality.

Primary performance measures

Prehospital care

Symptom onset to first medical contact (min).

Hospital admission ratio via ambulance (%).

Prehospital ECG transmission ratio (%).

Bypass ED ratio in patients with symptom onset within 12 hours (%).

Reperfusion

Overall reperfusion ratio (%).

Thrombolysis ratio in patients with symptom onset within 12 hours (%).

Primary PCI ratio in patients with symptom onset within 12 hours (%).

D2B in patients with symptom onset within 12 hours (min).

D2N in patients with symptom onset within 12 hours (min).

Discharge

Usage of both DAPT, statin, β blocker and ACEI/ARB in patients without contraindication (%).

Outcomes

In-hospital mortality (%).

Follow-up and management

1-year on-time follow-up ratio (%).

1-year MACE (%), including mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke and hospitalisation due to heart failure or acute coronary syndrome.

ACEI, ACE inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; D2B, door to balloon; D2N, door to needle; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy;ED, emergency department; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

The circular enrolment–evaluation–feedback–improvement method will be implemented in both CSCAP-2 and CSCAP-3. The quality feedback report contains each KPI of the affiliation and its ranking within its regional network and among all affiliations. Comparisons of KPIs with itself and those of others are analysed for tailed improvements.

Patient and public involvement

Public education of first aid and healthcare will be performed during the project implementation. Patients were not offered the opportunity to participate in the study design. They will obtain the information related to the study via public media as well as academic publications.

Ethics and dissemination

Ranking reports of quality of care will be made available to all participant affiliations. Results will be disseminated at international conferences and published in peer-reviewed scientific journals or public media.

Discussion

The integration and optimisation of an integrated regional network with government support are urgent issues of STEMI care, especially in China. CSCAP is the first prospective registry study focused on regional network construction and will help to understand the current situations and the differences with other countries extensively, which leads to optimised clinical practice and problem-guided improvement. It will provide important information for the network construction shifting from the PPCI hospital-centred regional network to the whole-city network step by step, so as to create an optimal integrated STEMI care system in China.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study team members and patient advisers of all collaborative hospitals and emergency medical services. They are also grateful to the organisational coordination of Chinese Medical Doctor Association and China Cardiovascular Association. They acknowledge the supports provided by the National Health Commission and local governments in China.

Footnotes

Contributors: YZ coordinated the study, assisted with data collection, performed data analysis and drafted the manuscript. BY, YH, JW, LY, ZW, ZZ, YC, XF, CG, BL, JC, MW, YM, XZ, YC, HY, DX, WF and JG carried out the data collection and helped draft the manuscript. SM and CKN participated in the design and helped draft the manuscript. YH, principal investigator of the project, conceived and designed the project, helped collect data and draft the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: CSCAP was funded by Chinese Medical Doctor Association with supports from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Essen Technology (Beijing) Co., Ltd., Lepu Medical Technology (Beijing) Co., Ltd., Sanofi-Aventis, Shenzhen Salubris Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd., and Tasly Pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was conducted in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University First Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Stevens W, Peneva D, Li JZ, et al. . Estimating the future burden of cardiovascular disease and the value of lipid and blood pressure control therapies in China. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:175 10.1186/s12913-016-1420-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Report on cardiovascular disease in China: Encyclopedia of China Publishing house, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. . ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2013;2013:e362–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, et al. . ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2569–619. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eagle KA, Nallamothu BK, Mehta RH, et al. . Trends in acute reperfusion therapy for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction from 1999 to 2006: we are getting better but we have got a long way to go. Eur Heart J 2008;29:609–17. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Song L, Hu DY, Yan HB, et al. . Influence of ambulance use on early reperfusion therapies for acute myocardial infarction. Chin Med J 2008;121:771–5. 10.1097/00029330-200805010-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li J, Li X, Wang Q, et al. . ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in China from 2001 to 2011 (the China PEACE-Retrospective Acute Myocardial Infarction Study): a retrospective analysis of hospital data. Lancet 2015;385:441–51. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60921-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jollis JG, Granger CB, Henry TD, et al. . Systems of care for ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: a report From the American Heart Association’s Mission: Lifeline. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2012;5:423–8. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.964668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kristensen SD, Fajadet J, Di Mario C, et al. . Implementation of primary angioplasty in Europe: stent for life initiative progress report. EuroIntervention 2012;8:35–42. 10.4244/EIJV8I1A7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gao R, Patel A, Gao W, et al. . Prospective observational study of acute coronary syndromes in China: practice patterns and outcomes. Heart 2008;94:554–60. 10.1136/hrt.2007.119750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hao Y, Liu J, Liu J, et al. . Rationale and design of the Improving Care for Cardiovascular Disease in China (CCC) project: A national effort to prompt quality enhancement for acute coronary syndrome. Am Heart J 2016;179:107–15. 10.1016/j.ahj.2016.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xu H, Li W, Yang J, et al. . The China Acute Myocardial Infarction (CAMI) Registry: A national long-term registry-research-education integrated platform for exploring acute myocardial infarction in China. Am Heart J 2016;175:193–201. 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pre-hospital medical emergency management measures. Chinese Village Medicine 2014:85–6. In Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 14. National Health Commission of China. Guiding Principles for Construction and Management of Chest Pain Center (Trial). 2017. In Chinese.

- 15. National Health Commission of China. The Announcement of Improving Medical Emergency Treatment Performance of Acute Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2015. In Chinese.

- 16. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. . Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation 2012;126:2020–35. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31826e1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chinese Society of Cardiology, Editorial board of Chinese Journal of Cardiology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. Chinese Journal of Cardiology 2015;43:380–93. In Chinese.26419981 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ranasinghe I, Rong Y, Du X, et al. . System barriers to the evidence-based care of acute coronary syndrome patients in China: qualitative analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2014;7:209–16. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bradley EH, Herrin J, Wang Y, et al. . Strategies for reducing the door-to-balloon time in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2308–20. 10.1056/NEJMsa063117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Graff LG, Dallara J, Ross MA, et al. . Impact on the care of the emergency department chest pain patient from the chest pain evaluation registry (CHEPER) study. Am J Cardiol 1997;80:563–8. 10.1016/S0002-9149(97)00422-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Windecker S, Bax JJ, Myat A, et al. . Future treatment strategies in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Lancet 2013;382:644–57. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61452-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. China Chest Pain Center Accreditation Work Committee. Standard for Chinese Chest Pain Center accreditation. J Interv Cardiol 2016;24:121–30. In Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 23. China Chest Pain Center Accreditation Work Committee. Standard for Chinese Primary Chest Pain Center accreditation. J Interv Cardiol 2016;24:131–3. In Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Diercks DB, Kontos MC, Chen AY, et al. . Utilization and impact of pre-hospital electrocardiograms for patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: data from the NCDR (National Cardiovascular Data Registry) ACTION (Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network) Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:161–6. 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Krim SR, Vivo RP, Krim NR, et al. . Regional differences in clinical profile, quality of care, and outcomes among Hispanic patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction in the Get with Guidelines-Coronary Artery Disease (GWTG-CAD) registry. Am Heart J 2011;162:988–95. 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.