Abstract

Introduction

Oocyte donation (OD) enables women with reproductive failure to conceive. Compared with naturally conceived (NC) and in vitrofertilisation (IVF) pregnancies, OD pregnancies are associated with a higher risk of pregnancy complications. The allogeneic nature of the fetus in OD pregnancies possibly plays a role in the development of these complications. The objective of the current study is therefore to study the number and nature of human leucocyte antigen (HLA) mismatches between fetus and mother and its association with the development of hypertensive pregnancy complications.

Methods and analysis

In this prospective multicentre cohort study, 200 patients visiting one of the 11 participating fertility centres in the Netherlands to perform OD or embryo donation or surrogacy will be invited to participate. These patients will be included as the exposed group. In addition, 146 patients with a NC pregnancy and 146 patients who applied for non-donor IVF are included as non-exposed subjects. These groups are frequency matched on age and ethnicity and only singleton pregnancies will be included. The primary clinical outcome of the study is the development of hypertensive disease during pregnancy. Secondary outcomes are the severity of the pre-eclampsia, time to development of pre-eclampsia and development of other pregnancy complications. The association of high number of HLA mismatches (>5) between mother and fetus will be determined and related to clinical outcome and pregnancy complication.

Ethics and dissemination

This study received ethical approval from the medical ethics committee in the Leiden University Medical Centre, the Netherlands (P16.048, ABR NL56308.058.16). Study findings will be presented at (inter) national conferences and published in peer-reviewed journals.

Keywords: oocyte donation, pregnancy, hla antigens, preeclampsia, pregnancy induced hypertension, histocompatibility

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Control of bias by adjustment for important confounders that are identified by a directed acyclic graph.

Minimising selection bias by selecting women pregnant after oocyte donation, embryo donation or surrogacy as the exposed group and non-donor in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and naturally conceived pregnancies as non-exposed group.

By including both non-donor IVF/intra cytoplasmic sperm injection pregnancies and women with naturally conceived pregnancies as the unexposed group, we take into account the confounding effect of artificial conception of the embryo, as well as hormonal treatment of women.

True translation of fundamental research into a clinical setting.

Study may be underpowered to show an association of human leucocyte antigen mismatches and other pregnancy complications than hypertensive complications.

Introduction

Oocyte donation (OD) is a specific method of artificial reproductive technology that resembles the technique of in vitro fertilisation (IVF), with the exception that an oocyte is obtained from a donor. Since the first successful OD pregnancy in 1984, thousands of OD procedures have been performed worldwide.1–3 Whereas the original indication was premature ovarian failure,4 nowadays the indication has been extended to other forms of infertility due to a diminished ovarian reserve.5–7

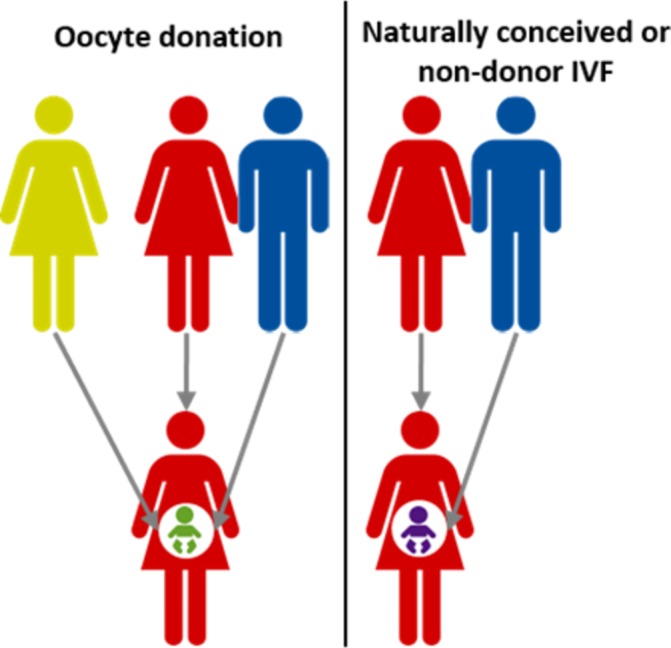

In OD pregnancies, the fetus can be completely allogeneic to the mother since the fetus carries paternal and donor-derived genes, whereas in non-donor autologous pregnancies, the fetus is semiallogeneic and haploidentical to the mother (figure 1). It is presumed that during OD pregnancies, the maternal immune system needs to adapt more, or differently, to tolerate this allogeneic fetus compared with naturally conceived (NC) and IVF pregnancies.8

Figure 1.

Allogeneic situation in oocyte donation pregnancies. In a naturally conceived or non-donor in vitro fertilisation (IVF) pregnancy, the fetus inherits the genetic material from both the mother and the father (right in picture) leading to a semiallogeneic situation. In an oocyte donation pregnancy involving an unrelated donor, the fetus may be completely allogeneic to the mother.

Despite the increasing number of OD procedures, relatively little is known about the underlying biology and long-term complications. Most of the literature regarding outcome in OD pregnancies has been focussing on perinatal complications, such as preterm birth, growth retardation and pre-eclampsia. Indeed, after correction for maternal age and plurality, OD pregnancies are accompanied with a higher risk for spontaneous miscarriages, pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH), caesarean section and bleeding complications, when compared with NC and IVF pregnancies.9–11 However, the pathophysiology of the higher incidence of pregnancy complication after OD remains unclear. A higher incidence of PIH has been shown when the oocyte donor is not genetically related to the recipient.12 A possible explanation therefore suggests a relationship with the high level of immunogenetic dissimilarity, reflected by the number of human leucocyte antigens (HLA) mismatches.13 14 Moreover, in uncomplicated OD pregnancies, a significant higher level of HLA class I matching between mother and child was observed than expected by chance.15 We therefore hypothesise in this study that the number of HLA mismatches between fetus and mother is related to the development of hypertensive pregnancy complications.

Study objectives

Primary objective

The primary objective of the study is the association of high number of HLA mismatches between fetus and mother and the development of hypertensive disease during pregnancy, including PIH and pre-eclampsia. High number of HLA mismatches is defined as ≥5 fetal–maternal HLA mismatches on the basis of discrepancy on the HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, HLA-DR and HLA-DQ antigens.

Secondary objectives

Secondary objective is the association of high number of HLA mismatches and the severity of the pre-eclampsia, time to the development of pre-eclampsia and development of other pregnancy complications, including spontaneous miscarriage, (severe) fetal growth restriction, haemolysis elevated liver enzymes and low platelet count (HELLP), gestational diabetes mellitus and (severe) preterm birth. Furthermore, the association of these outcomes with total number of HLA class mismatches, HLA class I and II mismatches and mismatching at HLA locus specifically is studied.

Methods and analysis

Study design

This study is performed within the DONOR project, a project on theDONation of Oocytes in Reproduction. This study will be performed as a prospective multicentre cohort study conducted at 11 fertility centres in the Netherlands, with the Leiden University Medical Centre (LUMC) as coordinating centre.

Data collection will continue until the required number of 492 patient inclusions has been reached and follow-up has been completed. This is expected to take approximately 2 years.

Eligibility

Inclusion criteria are:

Patients who are pregnant after OD, embryo donation or surrogacy pregnancy.

Patients who are pregnant after non-donor IVF or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI).

Patients with a NC pregnancy (spontaneously conceived and insemination).

Exclusion criteria includes patients with a multiple pregnancy, patients who are mentally or legally incapable of signing the informed consent, patients with known chromosomal abnormalities or fetal anomalies.

Study population and recruitment

Study recruitment started at the coordinating centre on 1 September 2016. All other centres will start recruitment in 2019. Recruitment is expected to last until September 2021.

In this cohort study, the exposure of interest is the number of HLA mismatches. However, HLA typing of the fetus and therefore determination of number of HLA mismatches can only be determined after birth and, thus, after the development of the outcome. Therefore, we will select women pregnant after OD, embryo donation or surrogacy as the exposed group. These women will be frequency matched for age (5-year categories) and ethnicity with two non-exposed women, represented by one non-donor IVF and one NC pregnancies.

The attending physician or nurse at the fertility department will ask eligible women who are pregnant after OD, embryo donation or surrogacy pregnancy. Age-matched and ethnicity-matched non-donor IVF women (see section above) will be selected by a research nurse, involved in this study, and asked to participate. This research nurse will also select age-matched and ethnicity-matched women with a NC pregnancy from the low-risk pregnancy population at the LUMC. These women will be recruited at their pregnancy intake visit in first trimester.

All women will receive written information and the informed consent form, which includes a request to obtain permission for gathering data from medical records and storage of biomaterial for additional analyses related to the current study. Participants are informed that trial participation is voluntary and that they are free to withdraw at any time without any consequences for subsequent care. All members of the research team are aware of the guidelines for good clinical practice for obtaining consent. In case of participation, the informed consent form should be signed prior to inclusion in the study. Women pregnant after OD, embryo donation or surrogacy pregnancy in a foreign country will also be included in the first trimester of pregnancy.

Study procedure

From all pregnancies, clinical characteristics will be documented (table 1). Peripheral blood samples will be obtained from all subjects. Women in this study will have regular checkups, according to Dutch guidelines,16 and complications will be documented in their medical records. In case of pregnancy loss (gestational age >8 weeks and <24 weeks), the products of conception will be collected for pathological investigation and fetal HLA typing. In case of a delivery (gestational age >24 weeks), umbilical cord blood will be obtained, as previously described.17 18 Material is pseudonomised by assigning a unique code after collection of materials and medical records.

Table 1.

Collection of data

| Parameters | |

| Maternal characteristics | Date of birth, maternal age, alcohol intake, smoking, caffeine intake, drugs intake, social economic class, weight, height, blood pressure, medical history (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, surgeries, previous blood transfusions), use of medication, education, ethnic origin, family history. |

| Paternal characteristics | Date of birth, age. |

| Donor characteristics | Date of birth, age. |

| Obstetric history | Parity, number of miscarriages, ectopic pregnancies or abortions, mode of delivery of previous births, gestational age at previous births, birth weight of children of previous births. |

| During pregnancy | Use of medication, miscarriage (spontaneously, medically induced or instrumental), hypertension, preeclampsia, pregnancy induced hypertension, haemolysis elevated liver enzymes and low platelets syndrome, vaginal bleeding, fetal growth restriction. |

| During delivery | Gestational age, (if relevant) indication for induction of labour, indication for secondary caesarean section/instrumental delivery, mode of delivery, medication during labour other than oxytocin, gender of child, birth weight. |

| Third stage | Method of delivery of placenta, placenta weight, postpartum haemorrhage and blood transfusions, perineum lacerations. |

| Neonatal data | Live birth, fetal gender, birth weight, 5 and 10 min Apgar scores, arterial umbilical cord pH, neonatal death, congenital anomalies, admission to intensive care unit. |

Control of bias

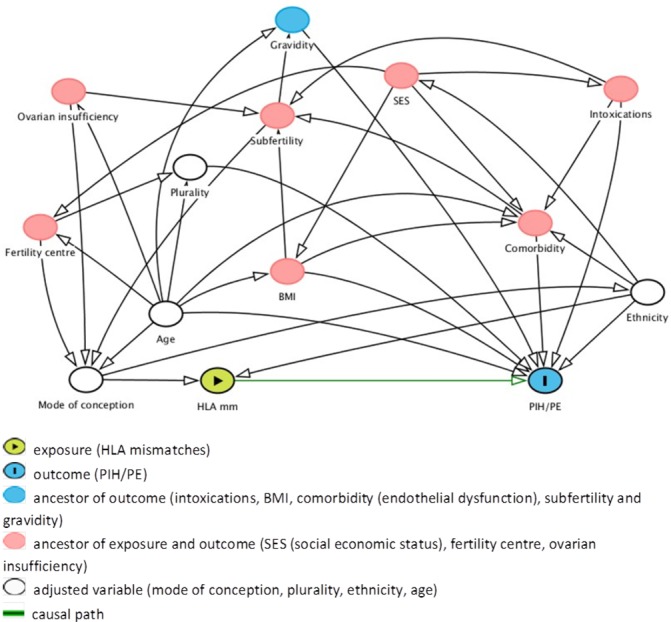

Since the design of this study is a prospective cohort study, there is a need to control and adjust for confounding factors. Advanced maternal age, primiparity, obesity, IVF and plurality are important risk factors for the development of hypertensive pregnancy complications.19–21 All possible factors are visualised to provide insight into their effects by a directed acyclic graph (figure 2) with the use of DAGitty program.22 According to this DAG, adjustment for age, ethnicity, plurality and mode of conception is necessary to minimise the effect confounding. Therefore, we will select singleton pregnancies only. Next, with the inclusion of a women pregnant after OD, embryo donation or surrogacy, two women with autologous pregnancies will be included. These non-exposed women are frequency matched for ethnicity and age. One woman after natural conception and one after IVF will be included for every exposed women. Finally, we will adjust for all pre-defined confounders including ‘mode of conception’ in the data analysis by multivariable analyses. In addition, since epidemiological studies show that limited seminal exposure or change of partner is associated with increased risk hypertensive complications,23 the factor ‘source of semen’ will be included in the multivariable analysis.

Figure 2.

The directed acyclic graph of this study with all associating factors, available on www.dagitty.net. The minimal sufficient adjustment sets contains age, ethnicity, plurality and mode of conception for estimating the effect of HLA mismatches on PIH/PE. BMI, body mass index; HLA, human leucocyte antigen; PE, pre-eclampsia; PIH, pregnancy-induced hypertension;

By including two unexposed groups: non-donor IVF or ICSI pregnancies as well as women with NC pregnancies, confounding is minimised. This is because artificial reproductive treatment is associated with more obstetric complications than NC pregnancies.24 IVF pregnancies are therefore selected, with a comparable assisted reproductive technique as performed in OD. The hormonal treatment as part of this technique is, however, different between non-donor IVF and OD. In non-donor IVF, the women receive hormonal treatment for the retrieval of the oocytes and for induction of a proper endometrium before embryo transfer. In OD, the recipient only receives the treatment before embryo transfer, and the oocyte donor receives the hormonal treatment necessary for oocyte retrieval. The use of these two unexposed groups has been described in prior research.14 25 The selection of the two unexposed groups is conducted early in pregnancy.

Finally, information bias is limited by using standard measurement instruments for HLA typing and calculation of HLA mismatches only and by using information from medical records before birth outcome is known.

Statistics

Sample size calculation

No previous studies exist in which the number of fetal–maternal HLA mismatches is related to the development of hypertensive pregnancy complications or other complications in pregnancy. As stated earlier, to prevent selection bias in this project, the exposed group is represented by women pregnant after OD, embryo donation or surrogacy and the non-exposed group are non-donor IVF and NC pregnancies. We based the sample size calculation on a study by Levron et al,26 in which the rate of hypertensive disease of pregnancy was determined in women who conceived through IVF using donor oocytes or autologous oocytes. In this study, a stratification for maternal age and restriction to singleton pregnancies was performed. The rate of hypertensive diseases was significantly higher among donor oocyte recipients compared with autologous oocyte recipients in patients <45 years (22% vs 10%, p=0.02). Using α=0.05 and Power=80% and the assumed relative risk of 2.2, we would need to include 146 patients who conceived with donor oocytes and 146 patients who conceived with autologous oocytes to demonstrate a significant difference. In earlier studies, we showed that the median number of HLA mismatches in the OD group was 7 (3–10), in the NC pregnancy group 4 (0–5) and in the non-donor IVF group 3 (0–4).13 We will therefore select 200 patients conceived with donor oocytes to obtain around 146 exposed women with >5 HLA mismatches. As we will include two unexposed, autologous groups, both 146 patients with NC pregnancy and 146 patients with IVF pregnancy should be included.

In the Netherlands, 285 OD procedures and one embryo donation were performed in 2012.2 The centres performing these procedures are participating in this project, and we therefore expect that the recruitment and inclusion will continue for approximately 2 years.

Statistical analysis plan

Relative risks and 95% CIs will be calculated for the dichotomous and categorical outcome measures. Differences between categorical variables will be compared between subgroups using the Χ2 test. Normally and non-normally distributed variables will be compared, respectively, using the unpaired t-test and the Mann-Whitney test.

To indicate an association between development of hypertensive complications (yes/no) and number of HLA mismatches, multiple logistic regression analysis will be performed with adjustment for age, ethnicity and the aforementioned possible confounding variables.

The relation between the number of HLA mismatches and time until development of hypertension will be visualised by Kaplan-Meier survival curves. The effect adjusted for age, ethnicity and confounders will be assessed by Cox proportional hazards regression.

Presence of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium will be assessed using Pypop Software V.0.7.0. All other statistical analyses are performed using SPSS Statistics V.23. For all tests a two-sided p<0.05 or 95% CI not including the null value is considered as significant.

Study outcomes

Clinical data

We will document the obstretric and general medical history of all women participating in this study (table 1). Furthermore, the following patient data is collected: date of birth, body weight and height, use of medication and ethnicity. In addition, paternal and donor age is collected.

During pregnancy, subjects included in this study will have checkups as with normal pregnancy controls27 and the development of possible complications during pregnancy, birth or postpartum will be documented in de medical file. The complications registred during the pregnancies are spontaneous miscarriage, (severe) fetal growth restriction, PIH, pre-eclampsia, HELLP, gestational diabetes mellitus and (severe) preterm birth. Definition of the registered complications are listed hereafter. Finally, neonatal data on birth weight, gender and Apgar score among others will be documented (table 1).

Fetal growth restriction is defined as estimated fetal weight (EFW) less than the 10th percentile, an estimated abdominal circumference (AC) less than 10 percentiles or deflection of the EFW and/or AC with greater than 20 percentiles over a period of more than 2 weeks.28

PIH is defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg detected after 20 weeks of gestation.

Pre-eclampsia is defined as PIH in combination with proteinuria, as shown by ≥300 mg/L on dipstick testing, a protein to creatinine ratio of ≥30 mg/mmol on a random sample or a urine protein excretion of ≥300 mg in 24 hours or worsening of pre-existent hypertension and proteinuria.29 Severe pre-eclampsia is defined when the blood pressure is >160 mm Hg systolic or >110 mm Hg diastolic or in the presence of the HELLP syndrome (see further), independent of the amount of proteinuria.30

The HELLP syndrome is a gestational disease characterised by haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and thrombocytopenia.31

Gestational diabetes mellitus is defined as hyperglycaemia during the pregnancy with an increased 75 g oral glucose tolerance test >7 mmol/L (sober) or >7.8 mmol/L (after 2 hours) measured in venous blood plasma.32

Spontaneous miscarriage is defined as the loss of pregnancy before the 24th week of gestation. In this study, miscarriages before 8 weeks (before inclusion) of either the exposed or non-exposed group will not be documented.

Preterm birth is defined as birth ≤37 completed weeks of gestation.33

Maternal peripheral blood and umbilical cord blood

DNA will be extracted from peripheral blood and umbilical cord blood. In case of a miscarriage, pregnancy tissue will be collected for cell isolation and DNA extraction. HLA will be typed for loci HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, HLA-E, HLA-G, HLA-DQ and HLA-DR using the Reverse Sequence Specific Oligonucleotides PCR technique.34 For class I, a commercially available assay is applied (LIFECODES HLA-A, B and C SSO Typing kits from Immucor), and HLA-DRB and HLA-DQB typing is performed with a locally developed SSO technique.35

The maternal and fetal HLA allele frequencies will be tested for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.36 37 The number of fetal–maternal HLA mismatches will be calculated at the Dutch national reference laboratory for histocompatibility testing (LUMC). On the basis of HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, HLA-DR and HLA-DQ antigens, the maximal number of (mis)matches between mother and child is 10.

The nature of the HLA mismatches will be further analysed by determining the number of HLA epitope mismatches between mother and child, using the HLAMatchmaker programme developed by Duquesnoy.38 With HLAMatchmaker histocompatibility between mother and child is determined on the basis of polymorphic amino acid configurations that represent defined areas of HLA epitopes on protein sequences of HLA-A, HLA-B and HLA-C chains accessible to alloantibodies.

Patient and public involvement statement

The Dutch society for patients with fertility problems (Freya) was consulted during the protocol development. To further facilitate the recruitment of patients, in addition to informing patients and their partners at the fertility centres, advertisement of this study will be done by the website of Freya. We will use their communication forms with their fellow sufferers to increase the recognition of the study and present results during their thematic meetings to inform on (progress of) the study. In addition, social media will be used to signpost publications and conference presentations and highlight important findings.

Discussion

A successful pregnancy is an immunological paradox.39 The fetus carries paternal and maternal genes, but is not rejected by the maternal immune system. In OD pregnancy, the fetus may be completely allogeneic compared with the mother. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the immune system needs to adapt more or differently to accept the allogeneic fetus. In this study we aim to determine if a higher number of HLA mismatches contributes to a higher incidence of pregnancy hypertensive complications.

In solid organ transplantation, immunogenic dissimilarities are present between donor and recipient, and use of immunosuppressive drugs is necessary to prevent rejection of the graft.8 40 As immunological acceptance of the fetus is often compared with the state of tolerance to an engrafted organ, the recognition of fetal antigens in pregnancy disorders, such as miscarriages and hypertensive complications, could be viewed as a kind of graft rejection.41

HLA typing and selection for an optimal number of HLA mismatches might therefore be useful as future strategies to induce immune tolerance and reduce complication rate in OD pregnancies.40

Expected results

We expect to find a higher degree of pregnancy complications in OD pregnancies compared with IVF and NC pregnancies.

We expect to find a higher number of HLA mismatches between mother and fetus in a pregnancy conceived through OD compared with IVF and NC pregnancies.

We expect to find an association between the development of hypertensive pregnancy complications and a higher number of HLA mismatches.

We expect to find a higher number of HLA mismatches between mother and fetus in women who conceived through OD with severe hypertensive complication, and that the development of the (severe) preeclampsia is at earlier gestational age.

The results of this project may provide new strategies in increasing the chance of a successful OD pregnancy, for instance by defining the optimum number of HLA mismatches between donor and recipient before pregnancy. This would imply a possibility to HLA typing and matching of donors and recipients of oocytes, and extra medical care or use of specific medication during pregnancy to optimise the pregnancy outcome.

The results of this project may lead to changes in guidelines and protocols considering OD pregnancies regarding an optimal number of HLA mismatches for OD pregnancies.

Ethics and dissemination

The study will be conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

As mentioned before, all patients will obtain written information of the study. After a period of consideration, the patient has to decide about participation. In case of participation, the informed consent form should be signed prior to inclusion in the study. All women are treated according to local protocols. Research nurses will ensure that the samples are immediately pseudonimised by assigning a unique code. This unique code will also be used to associate clinical data with the samples, without the need for personal identifiers such as donor name, date of birth or patient hospital number on the sample container. Furthermore, the code will encompass the association of maternal and fetal samples from one family. Patients will be asked to fill in webform questionnaires. Answers from this questionnaire will be linked to the Promise DONOR-database. These data, together with clinical data, will be saved semianomymised in the Promise DONOR-database. Only a minimum number of members of our project group will have access to this database. The principal investigators will ensure that the database is maintained efficiently and that all information is up to date and accurate.

Approval was obtained from the LUMC Medical Research Ethics Committee protocol number P16.048. Study findings will be presented at (inter) national conferences and published in peer-reviewed journals.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

KB and EL contributed equally.

Contributors: MLvdH is the coordinating investigator. MLvdH and EL drafted the protocol and then KvB, MB and EL wrote the protocol in accordance with the co-authors’ contributions. ME, SH and FC complemented on the immunological questions in this protocol and SlC improved the methodological aspects. All authors contributed to the writing and reviewing of this article and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This project has been sponsored by the Leiden University Fund (LUF) / Den Dulk-Moermans Fonds 5212/30-4-15/DM.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Ferraretti AP, Goossens V, Kupka M, et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Europe, 2009: results generated from European registers by ESHRE. Hum Reprod 2013;28:2318–31. 10.1093/humrep/det278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Calhaz-Jorge C, de Geyter C, Kupka MS, et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Europe, 2012: results generated from European registers by ESHRE. Hum Reprod 2016;31:1638–52. 10.1093/humrep/dew151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lutjen P, Trounson A, Leeton J, et al. The establishment and maintenance of pregnancy using in vitro fertilization and embryo donation in a patient with primary ovarian failure. Nature 1984;307:174–5. 10.1038/307174a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bustillo M, Buster JE, Cohen SW, et al. Nonsurgical ovum transfer as a treatment in infertile women. Preliminary experience. JAMA 1984;251:1171–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Antinori S, Versaci C, Gholami GH, et al. Oocyte donation in menopausal women. Hum Reprod 1993;8:1487–90. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Klein J, Sauer MV. Oocyte donation. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2002;16:277–91. 10.1053/beog.2002.0288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee SJ, Schover LR, Partridge AH, et al. American society of clinical oncology recommendations on fertility preservation in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:2917–31. 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van der Hoorn ML, Lashley EE, Bianchi DW, et al. Clinical and immunologic aspects of egg donation pregnancies: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update 2010;16:704–12. 10.1093/humupd/dmq017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Levron Y, Dviri M, Segol I, et al. The ’immunologic theory' of preeclampsia revisited: a lesson from donor oocyte gestations. AmJObstet Gynecol 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Storgaard M, Loft A, Bergh C, et al. Obstetric and neonatal complications in pregnancies conceived after oocyte donation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG 2017;124:561–72. 10.1111/1471-0528.14257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Masoudian P, Nasr A, de Nanassy J, et al. Oocyte donation pregnancies and the risk of preeclampsia or gestational hypertension: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;214:328–39. 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hs K, Km Y, Sh C, et al. Obstetric outcomes after oocyte donation in patients with premature ovarian failure. Abstracts of the 21st annual meeting of the ESHRE, Copenhagen, Denmark 2005;20(Suppl 1):i34. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lashley LE, van der Hoorn ML, Haasnoot GW, et al. Uncomplicated oocyte donation pregnancies are associated with a higher incidence of human leukocyte antigen alloantibodies. Hum Immunol 2014;75:555–60. 10.1016/j.humimm.2014.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van der Hoorn MP, van Egmond A, Swings G, et al. Differential immunoregulation in successful oocyte donation pregnancies compared with naturally conceived pregnancies. J Reprod Immunol 2014;101-102:96–103. 10.1016/j.jri.2013.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lashley LE, Haasnoot GW, Spruyt-Gerritse M, et al. Selective advantage of HLA matching in successful uncomplicated oocyte donation pregnancies. J Reprod Immunol 2015;112:29–33. 10.1016/j.jri.2015.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Evers IM, Duvekot JJ, Middeldorp JM, et al. Richtlijn Basis Prenatale zorg: opsporing van de belangrijkste zwangerschapscomplicaties bij laag-risico zwangeren (in de 2de en 3de lijn). Nederlandse Vereniging voor Obstetrie en Gynaecologie 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schonkeren D, van der Hoorn ML, Khedoe P, et al. Differential distribution and phenotype of decidual macrophages in preeclamptic versus control pregnancies. Am J Pathol 2011;178:709–17. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tilburgs T, Roelen DL, van der Mast BJ, et al. Differential distribution of CD4(+)CD25(bright) and CD8(+)CD28(-) T-cells in decidua and maternal blood during human pregnancy. Placenta 2006;27(Suppl A):47–53. 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dekker GA. Risk factors for preeclampsia. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1999;42:422–35. 10.1097/00003081-199909000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Duckitt K, Harrington D. Risk factors for pre-eclampsia at antenatal booking: systematic review of controlled studies. BMJ 2005;330:565 10.1136/bmj.38380.674340.E0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mol BW, Roberts CT, Thangaratinam S, et al. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Textor J, van der Zander B, Gilthorpe MS, et al. Robust causal inference using directed acyclic graphs: the R package ’dagitty'. Int J Epidemiol 2016;45:1887–94. 10.1093/ije/dyw341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kho EM, McCowan LM, North RA, et al. Duration of sexual relationship and its effect on preeclampsia and small for gestational age perinatal outcome. J Reprod Immunol 2009;82:66–73. 10.1016/j.jri.2009.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Allen VM, Wilson RD, Cheung A, et al. Pregnancy outcomes after assisted reproductive technology. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2006;28:220–33. 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)32112-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lashley LE, Buurma A, Swings GM, et al. Preeclampsia in autologous and oocyte donation pregnancy: is there a different pathophysiology? J Reprod Immunol 2015;109:17–23. 10.1016/j.jri.2015.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Levron Y, Dviri M, Segol I, et al. The ’immunologic theory' of preeclampsia revisited: a lesson from donor oocyte gestations. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;211:383.e1–383.e5. 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.03.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. NVOG. Basis prenatale zorg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28. NVOG. Foetale groeirestrictie (FGR), 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Milne F, Redman C, Walker J, et al. The pre-eclampsia community guideline (PRECOG): how to screen for and detect onset of pre-eclampsia in the community. BMJ 2005;330:576–80. 10.1136/bmj.330.7491.576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tranquilli AL, Brown MA, Zeeman GG, et al. The definition of severe and early-onset preeclampsia. Statements from the International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy (ISSHP). Pregnancy Hypertens 2013;3:44–7. 10.1016/j.preghy.2012.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tranquilli AL, Dekker G, Magee L, et al. The classification, diagnosis and management of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: A revised statement from the ISSHP. Pregnancy Hypertens 2014;4:97–104. 10.1016/j.preghy.2014.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. NVOG. Diabetes en zwangerschap. Richtlijn NVOG 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 33. NVOG. Dreigende vroeggeboorte. Richtlijn NVOG, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dalva K, Beksac M. HLA typing with sequence-specific oligonucleotide primed PCR (PCR-SSO)and use of the Luminex technology. Methods Mol Med 2007;134:61–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Verduyn W, Doxiadis II, Anholts J, et al. Biotinylated DRB sequence-specific oligonucleotides. Comparison to serologic HLA-DR typing of organ donors in eurotransplant. Hum Immunol 1993;37:59–67. 10.1016/0198-8859(93)90143-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hardy GH. Mendelian proportions in a mixed population. Science 1908;28:49–50. 10.1126/science.28.706.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Weinberg. On the demonstration of heredity in man SH B, Papers on human genetics. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Duquesnoy RJ. HLAMatchmaker: a molecularly based algorithm for histocompatibility determination. I. Description of the algorithm. HumImmunol 2002;63:339–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Billington WD. The immunological problem of pregnancy: 50 years with the hope of progress. A tribute to Peter Medawar. J Reprod Immunol 2003;60:1–11. 10.1016/S0165-0378(03)00083-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. van der Hoorn ML, Scherjon SA, Claas FH. Egg donation pregnancy as an immunological model for solid organ transplantation. Transpl Immunol 2011;25:89–95. 10.1016/j.trim.2011.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wilczyński JR. Immunological analogy between allograft rejection, recurrent abortion and pre-eclampsia – the same basic mechanism? Hum Immunol 2006;67:492–511. 10.1016/j.humimm.2006.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.