Abstract

Objectives

The British Association of Spinal Surgeons recently called for updates in consenting practice. This study investigates the utility and acceptability of a personalised video consent tool to enhance patient satisfaction in the preoperative consent giving process.

Design

A single-centre, prospective pilot study using questionnaires to assess acceptability of video consent and its impacts on preoperative patient satisfaction.

Setting

A single National Health Service centre with individuals undergoing surgery at a regional spinal centre in the UK.

Outcome measure

As part of preoperative planning, study participants completed a self-administered questionnaire (CSQ-8), which measured their satisfaction with the use of a video consent tool as an adjunct to traditional consenting methods.

Participants

20 participants with a mean age of 56 years (SD=16.26) undergoing spinal surgery.

Results

Mean patient satisfaction (CSQ-8) score was 30.2/32. Median number of video views were 2–3 times. Eighty-five per cent of patients watched the video with family and friends. Eighty per cent of participants reported that the video consent tool helped to their address preoperative concerns. All participants stated they would use the video consent service again. All would recommend the service to others requiring surgery. Implementing the video consent tool did not endure any significant time or costs.

Conclusions

Introduction of a video consent tool was found to be a positive adjunct to traditional consenting methods. Patient–clinician consent dialogue can now be documented. A randomised controlled study to further evaluate the effects of video consent on patients’ retention of information, preoperative and postoperative anxiety, patient reported outcome measures as well as length of stay may be beneficial.

Keywords: video consent, informed consent, patient satisfaction, spinal surgery

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The development of a personalised video consent tool used to promote patient autonomy and shared decision making.

An exploratory pilot study in spinal surgery, future research will explore the use of Oxford Informed Video Consent Tool across different surgical specialities.

Prospective quantitative data gathered from 20 participants, the introduction of a qualitative research element is planned for phase II of this study.

A novel method to document the patient–clinician preoperative consent conversation.

Introduction

Informed consent is a legal and ethical principle that is required prior to any intervention that may violate autonomy. The Montgomery v Lanarkshire judgement1 initiated a change in how healthcare professionals obtain informed consent. Montgomery1 confirms the shift from an already eroding paternalistic approach to consent set by Bolam v Friem Hospital Management Committee,2 to the adoption and acknowledgment of a person-centred approach seen in Sidaway v Bethlem Royal Hospital,3 De Freitas v O’Brien4 and Bolitho v City & Hackney HA.5 Others concur that Montgomery marked a decisive shift in the legal test of duty of care, from the perspective of the clinician to that of the patient.6

Informed consent has gained accelerated momentum following the Montgomery judgement.

In acknowledgement of the recent changes in consenting practice, the General Medical Council (GMC), the Royal College of Surgeons and other professional organisations, such as The British Association of Spinal Surgeons, have issued best practice guidelines on obtaining informed consent.7 However, despite the release of updated guidelines, there is currently a gap in consenting practice relating to documenting the preoperative consent conversation.

Preparing to undergo surgery can be a stressful event for both patients and their families. Often, important information discussed within the consent consultation is forgotten.8 By providing patients access to a tool that captures their consent conversation, it is thought that the video will provide patients an opportunity to reflect and revisit the previously discussed dialogue, prior to consenting to treatment. It encourages a bespoke individualised approach as indicated by Montgomery.1 The addition of this step to the preoperative consenting process may safeguard patients from medical coercion and promote autonomy to make an informed decision about their care, while reducing potential litigation claims.

Enhancements in digital technology are driving changes in information practices.

Such enhancements have influenced how informed consent may be delivered9; examples include the use of iPads to deliver consent information10 and the use of a smartphone applications to assist informed consenting practice.11 The acceptance of multimedia technology in preoperative consenting has been demonstrated across a variety of surgical disciplines, including foot and ankle surgery,12 spinal surgery,13 vascular surgery,14 ophthalmic surgery,15 gastrointestinal surgery16 and urological surgery.17 Notably, such preoperative multimedia consent technologies are often generic and not patient specific. There is currently a lack of research regarding the use of personalised multimedia consenting adjuncts within surgery.

In order to improve service delivery and comply with the updated guidelines, we piloted a video consent tool (Oxford Informed Video Consent Tool (OxVIC) as an adjunct to traditional consenting methods for patients attending a spinal Preoperative Outpatient Assessment Clinic (POAC). Each consent video contained indications for surgery, associated risks and benefits, alternative treatment options and a section for patients to ask questions or clarify points. To our knowledge, the use of a video informed consent tool has not been used before in spinal surgery.

Our study aims were to evaluate acceptability of a novel consent tool (OxVIC), as an adjunct to traditional (written and verbal) consenting methods. This aims to provide documentary evidence of the patient–clinician consent conversation, which now forms part of the medical notes. Our study aims to improve patient experience and enhance patient satisfaction within the preoperative consent process, while generating an evidence base for future research.

Methods

Ethical approval for this project was obtained. In addition to the video consent process described below, written informed consent was additionally obtained from all participants.

Procedure

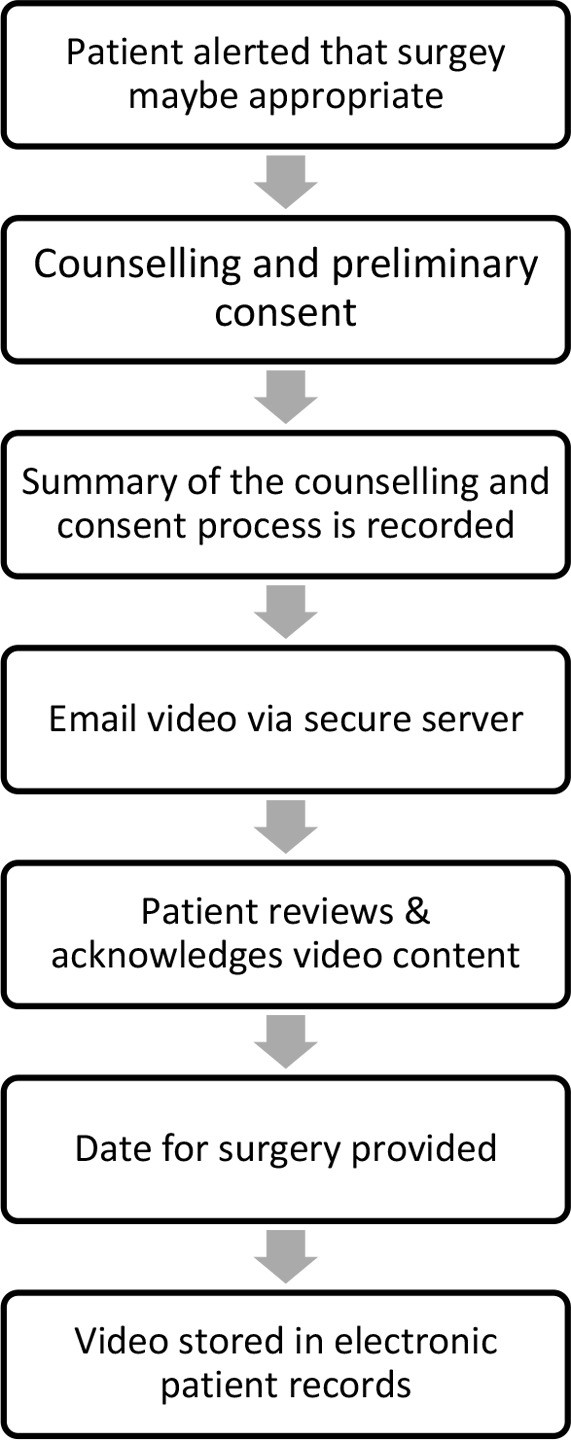

We conducted a single-centre, non-randomised, non-comparative pilot study in patients undergoing a spinal procedure at a National Health Service (NHS) spinal centre in the UK. A flowchart of the study procedure is outlined in figure 1. Prior to consenting to take part, all patients received a Participant Information Sheet (PIS). The PIS outlined that if patients agreed to take part, they would receive the ‘gold standard’ (verbal and written) in consent information. In addition to this, they would also receive a consent adjunct in the form of a personalised video.

Figure 1.

An overview of the Oxford Video Informed Consent Tool process.

All participants who agreed to take part were consented by fellowship trained Consultant Spinal Surgeons using verbal and written consenting methods in addition to a summary of the consent consultation being recorded. A researcher independent of the surgical team provided participants with patient information sheets prior to consenting. Participants were all informed that participation was voluntary and were free to withdraw at any time. The summary was conducted in a structured way and consisted of the following: a discussion around the patients reasoning for choosing surgery, followed by an overview of the surgical procedure, its intended benefits and associated risks ending with an opportunity for the patients to check their understanding by asking questions.

A password protected email and a hospital trust approved web transfer service was used to send the personalised consent videos to study participants. Participants reviewed their personalised consent consultations at home with their family or friends. Participants had the option to forward their personal consent videos to family members outside of the UK. All participants were invited to contact the spinal team to seek clarity or ask further questions regarding the video content (two participants used this service). The recorded consent was stored securely within the electronic health record, accessible only to the research team.

Participants were asked to contact the spinal team once they had reviewed the consent conversation, acknowledging the risks and benefits of the proposed treatment. Prospective patient data were obtained using a self-administered questionnaire regarding patient satisfaction with the use of a video consent tool as an adjunct to traditional consenting methods. Participants were invited to complete the measure following the consent consultation and after reviewing their personalised consent video.

Approximately 13 additional minutes were required compared with the traditional process to complete the video recording process. The mean recording time was 13 min and 15 s, with a range of 6 min and 21 s, to 20 min and 55 s. This was dependant of the complexity of the proposed treatment and its associated risks and benefits. Introduction of the video consent tool did not endure any significant costs as the technology already existed within the Trust.

Participants

Participants were recruited over a 4-month period (September to December 2017).

Twenty-two people were approached to take part, two declined and twenty volunteered (n=20). Participants did not receive an honorarium for taking part in the study. Study inclusion criteria were: over the age of 18 years of age; have capacity to make informed decisions; and have an active email address with access to the internet. Participants were excluded from the study if they had any visual or hearing impairments which may inhibit the ability to review the consent video.

Assessments

A researcher independent of the surgical team distributed electronic Self-Administered Questionnaires (SAQ) to participants who agreed to partake in the study, data were collected at one point, post consent consultation. Participant demographics, which included gender, age, number of times the video consent tool was viewed and who they watched the video with, were collected. In addition to this, participants completed the validated CSQ-8 tool. The CSQ-8 tool consists of eight self-report questions, each constructed with a four-point Likert scale reply.18 The minimum achievable satisfaction score is 8, indicating poor satisfaction, a maximum score of 32 would indicate high levels of satisfaction.19 20 The CSQ-8 tool has been extensively tested for reliability and validity19–21; to date, it has been translated into more than 30 languages since its first launch in the early 1980s.22 The CSQ-8 has been found to be acceptable for use in previous studies examining patient satisfaction with consenting methods.17 23

Data analysis

The data collection period finished once 20 completed SAQs were received. Normality of data was assessed using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Descriptive, bivariate and inferential statistics were calculated and reported using two-tailed methods with the assistance a statistical programme from IBM, SPSS V.24 for Microsoft© Windows V.10.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the development or design of this pilot study. However, following this preliminary pilot study, patient involvement will be included in the development of subsequent studies utilising OxVIC.

Results

Descriptive information

Over a 4-month period, 20 participants (10:10, male:female) deemed suitable candidates for spinal procedures were recruited into the study. The mean age was 56 years (SD=16.26), range: 27 to 81 years. Participant demographics can been seen in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of study participants

| Demographics | Sample statistics | |

| Gender, N(%) | Male | 10 (50%) |

| Female | 10 (50%) | |

| Participant age (years) SD=16.26 | 25–34 | 2 (10%) |

| Mean age: 56 years | 35–44 | 0 (0%) |

| 45–54 | 6 (30%) | |

| 55–64 | 5 (25%) | |

| 65–74 | 4 (20%) | |

| 75–99 | 3 (15%) | |

| Range | 27–81 | |

| Variety of surgical procedures | Deformity correction Lumbar degenerative Nerve root block Removal of metalwork Tumour surgery |

3 6 3 1 7 |

| Frequency of viewing consent video | Once | 7 (35%) |

| Two to threetimes | 10 (50%) | |

| Four to fivetimes | 3 (15%) | |

| Video watched (with) | Alone | 3 (15%) |

| Family and friends | 17 (85%) |

Patient satisfaction

CSQ-8 data were normally distributed. High patient satisfaction levels were reported across a broad range of spinal procedures. The mean patient satisfaction score (CSQ-8) was 30.2 out of a maximum 32, indicative of high patient satisfaction.

CSQ-8 scores by gender and age can be seen in table 2. A two-way between-groups analysis of variance was conducted to explore the impact of gender and age on patient satisfaction levels, as measured by the CSQ-8 scale. Participants were divided into five groups depending on their age (group 1: 25–34 years, group 2: 45–54 years, group 3: 55–64 years, group 4: 65–74 years and group 5: 75–99 years). The interaction effect between gender and age was not statistically significant (p=0.155).

Table 2.

Mean CSQ-8 scores by age and gender

| Demographic | Mean CSQ-8 score (Maximum score 32) |

Range (SD) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 30 | 26–32 (2.2) |

| Female | 30.4 | 29–32 (1.07) |

| Total mean | 30.2 | 26–32 (1.70) |

| Participant age (years) | ||

| 25–34 | 31 | 30–32 |

| 35–44 | - | - |

| 45–54 | 30.16 | 26–31 |

| 55–64 | 29 | 26–31 |

| 65–74 | 30.25 | 28–32 |

| 75–99 | 31.66 | 31–32 |

CSQ-8 responses generated several significant trends, a strong positive relationship between meeting patients’ preoperative consenting needs and helping them to deal more effectively with their preoperative concerns was reported (p=0.028), with 80% reporting that the tool helped a great deal. All participants reported that they would recommend the video consent tool to others preparing for surgery. When asked ‘if future treatment were required, would you use the service again?’, all participants responded yes. A significant positive relationship between the quality of the service participants received versus the service they expected was observed (p=0.008).

Engagement with the tool

All participants watched the consent video at least once prior to consenting for surgery, with a mean number of viewings of 2–3 times. Eighty-five per cent of the participants watched the consent video with friends and family, which included next of kin, partners, children and other family members. Two participants sent the consent videos to their children living overseas. Fifteen per cent of participants reported watching their video alone. Those who watched the video four to five times on average reported higher satisfaction scores.

Discussion

The main findings of our study were that participants were overall completely satisfied with the video consent tool and the service. All participants reported that they would use the service again if needed and that they would recommend the service to others requiring surgery. The mean CSQ-8 satisfaction score reported in this study was 30.2, with scores above 24 considered as high levels of satisfaction.21

It was beyond the scope of this exploratory pilot study to examine how the video consent tool compared with other methods of consent, such as audio recording of consent. Nonetheless, participant scores on the CSQ-8 in the present study indicate that the personalised video consent tool may be equal to, if not more effective than, the existing methods (eg, audio recording alone).17 23 However, additional research is needed to further explore this possibility. Our preliminary results suggest that participants’ age or gender did not affect patient satisfaction levels with the use of the video consent tool in the preoperative setting. This finding is consistent with previous studies.12 24 25

Busy preoperative clinics, poor communication techniques, unanswered questions, anxiety and poor comprehension are all barriers to patients not retaining information.26 Our study indicates that the use of personalised video tool may allow patients to process and review complex information previously discussed by the surgeon, from the comforts of their own home. Participants had the opportunity to email the spinal service for further clarity of the video content and two participants used this service.

Introduction of the video consent tool did not require significantly more clinician time. The ability to watch the video with family members, or even to securely send family members the video, allowed for shared decision making and aided a person-centred approach to care, empowering participants to manage their own medical information. This is important for patients outcomes as shared decision making facilitates increased patient satisfaction levels and potentially reduces illness uncertainty.27 28

All patients engaged with their personalised consent adjunct twice on average before consenting to surgery. To our knowledge, multiple interactions of a preoperative consent adjunct have not been reported in the literature.29 All patients were happy to recommend OxVIC to others requiring preoperative surgical consent, indicating that they were satisfied and it would be acceptable for further use.

This project found that the more times participants watched their consent video, the more satisfied they became with their consent process. With the highest satisfaction scores in those who engaged with the video tool the most (four to five times). Moreover, as the majority of studies using multimedia tools as an adjunct to informed consent do not personalise their content,27 29 this is the first time that the use of a personalised multimedia tool has been reported in the literature.

Clinical implications

This study indicates that a personalised video consent tool is feasible to administer during the preoperative consent process for spinal surgery procedures and that the intervention produced high satisfaction scores. Overall, we found that approximately 13 additional minutes was required compared with the traditional process to complete the video recording process.

This suggests that OxVIC would be acceptable for use, particularly in complex consultations where decision-making and communication might be more challenging for both the clinician and the patient.

While concerns over additional time, potential costs and practicality as to achieving this process are valid, they did not appear to be a significant barrier to delivering this service. Provided one has access to a good quality digital recording device, such as a smartphone that can transfer and store data securely, then the process can be straightforward.

We recognise that patients need to have access to the internet and may require help if not familiar using this sort of technology; however, as 85% of UK adults have a smartphone,30 access to the internet in this is not an insurmountable barrier. Future studies exploring clinician experiences of obtaining patient consent via OxVIC would also be useful to ensure that any concerns or barriers to use that were not identified in the present study are considered and acceptably addressed.

While we have not undertaken a cost analysis, for this pilot, there have been no significant costs as the technology already exists within the NHS Trust. Introducing OxVIC into clinical practice has numerous benefits such as documentary evidence of the clinician–patient consent conservation, which may reduce medicolegal cases. It may be used as an educational tool for medical teaching and could act as a patient resource/decision aid useful when analysing potential benefits and risks associated with surgery.

We would therefore suggest video consenting as a new benchmark in the consenting process. Based on this study, we recommend a large-scale study to evaluate the full impact of this process on outcome measures such as information retention, length of stay and litigation claims.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths and weaknesses. Among the strengths was the development of a novel method to document the patient–clinician consent conversation. To our knowledge, this study is the first of its kind to provide preoperative patients with a personalised multimedia consent adjunct (OxVIC). Furthermore, OxVIC allows patients to review their consent conversation with family members and friends away from the clinical area, promoting shared decision making and patient autonomy.

Among the weaknesses is the limited diversity of the sample (eg, spinal surgery patients). Further studies could include the patient perspectives from other surgical specialities. In addition, quantitative data gathered within this pilot could be supported by the addition of qualitative research methods. While a standard NHS/Trust surgical consent form was used to promote surgeon adherence to standard information giving, the consent videos were not independently reviewed for validation purposes prior to patient access. The potential for standardisation should be considered in future studies of multimedia consenting.

Finally, concerns regarding cost and additional consenting time could be perceived as a potential limitation. However, the ability to document the patient–clinician conversation and its potential application to medicolegal practice may outweigh such concerns. This needs to be considered in future feasibility studies.

Future research

The findings from this pilot provide a foundation for potential future research projects.

A larger more diverse sample size to include younger (<25 years) and older (75 years+) people could add to the validity. Moreover, there is scope for the tool to be included in other specialities and further research should examine the acceptability of video consenting tool in multiple surgical disciplines. A larger study to definitively test the efficacy of OxVIC across different surgical specialities is in process.

Conclusion

If patient satisfaction is a measure of quality,31 this study indicates that the introduction of a personalised consent tool may have a positive impact on the quality of service patients receive. The provision of informed care could be facilitated by the introduction of a personalised video tool, as it promotes patient autonomy, shared decision making and empowers patients to manage their own health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support received from the spinal surgery department throughout the pilot and thank those who volunteered to take part in the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: GM, CT and JR made substantial contributions to the conception of the study. GM analysed and interpreted the data for the study. GM, JR and DAR contributed to acquisition of the data. GM, CT, VW, DAR and JR drafted the article and revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the article in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the article are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Oxford Brookes University, Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee (FREC2016/57).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: We welcome data-sharing requests from researchers interested in OxVIC. Please contact GM (gerard.mawhinney@ouh.nhs.uk) directly to explore further.

Author note: OxVIC - The Oxford Video Informed Consent Tool is a registered trademark.

Presented at: This study has been presented via podium presentation at the 41st Annual Scientific Meeting of the Singapore Orthopaedic Association, The Joint British Scoliosis Society/Irish Spine Society Meeting, Belfast, 2018 and at the European Operating Room Nurses Association (EORNA) Congress, The Hague, The Netherlands 2019.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board Scotland. UKSC 11. 2015.

- 2. Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee. 1: WLR 583. 1957.

- 3. Sidaway v Board of Governors of the Bethlem Royal Hospital. 1: All ER 643. 1985.

- 4. De Freitas v O’Brien. P.I.Q.R. P281. 1995.

- 5. Bolitho (Deceased) v City & Hackney HA. P.I.Q.R. P334. 1997.

- 6. Herring J, Fulford K, Dunn M, et al. Elbow Room for Best Practice? Montgomery, Patients' values, and Balanced Decision-Making in Person-Centred Clinical Care. Med Law Rev 2017;25:582–603. 10.1093/medlaw/fwx029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Powell JM, Rai A, Foy M, et al. The ‘three-legged stool’ - A system for spinal infomred consent. Bone Joint J 2016;98:427–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Saigal R, Clark AJ, Scheer JK, et al. Adult Spinal Deformity Patients Recall Fewer Than 50% of the Risks Discussed in the Informed Consent Process Preoperatively and the Recall Rate Worsens Significantly in the Postoperative Period. Spine 2015;40:1079–85. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grady C, Cummings SR, Rowbotham MC, et al. Informed Consent. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2017;376:856–67. 10.1056/NEJMra1603773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rowbotham MC, Astin J, Greene K, et al. Interactive informed consent: randomized comparison with paper consents. PLoS One 2013;8:e58603 10.1371/journal.pone.0058603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McConnell MV, Shcherbina A, Pavlovic A, et al. Feasibility of obtaining measures of lifestyle from a smartphone app: the My Heart Counts Cardiovascular Health Study. JAMA 2017;2:67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Batuyong ED, Jowett AJ, Wickramasinghe N, et al. Using multimedia to enhance the consent process for bunion correction surgery. ANZ J Surg 2014;84:249–54. 10.1111/ans.12534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Briggs M, Wilkinson C, Golash A. Digital multimedia books produced using iBooks Author for pre-operative surgical patient information. J Vis Commun Med 2014;37:59–64. 10.3109/17453054.2014.974516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bowers NE, Montbriand E, Jaskolka J, et al. Using a multimedia presentation to improve patient understanding and satisfaction with informed consent for minimally invasive vascular proceddures. Surgeon 2015;17:7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tipotsch-Maca SM, Varsits RM, Ginzel C, et al. Effect of a multimedia-assisted informed consent procedure on the information gain, satisfaction, and anxiety of cataract surgery patients. J Cataract Refract Surg 2016;42:110–6. 10.1016/j.jcrs.2015.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eggers C, Obliers R, Koerfer A, et al. A multimedia tool for the informed consent of patients prior to gastric banding. Obesity 2007;15:2866–73. 10.1038/oby.2007.340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Winter M, Kam J, Nalavenkata S, et al. The use of portable video media vs standard verbal communication in the urological consent process: a multicentre, randomised controlled, crossover trial. BJU Int 2016;118:823–8. 10.1111/bju.13595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nguyen TD, Attkisson CC, Stegner BL. Assessment of patient satisfaction: Development and refinement of a Service Evaluation Questionnaire. Eval Program Plann 1983;6(3-4):299–313. 10.1016/0149-7189(83)90010-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Attkisson CC, Zwick R. The client satisfaction questionnaire: Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilisation and psychotherapy outcome’. Eval Program Plann 1983;5:233–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Larson DLA, Hargreaves CC, W.A Nguyen, T.D. Assessment of client / patient satisfaction: development and refinement of a service evaluation questionnaire. Eval Program Plann 1979;6:299–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nguyen TD, Attkisson CC, Stegner BL. Assessment of patient satisfaction: development and refinement of a service evaluation questionnaire. Eval Program Plann 1983;6:299–313. 10.1016/0149-7189(83)90010-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. LLC TMS. CSQ Scales. 2018. http://www.csqscales.com/csq-translations.htm

- 23. Sahai A, Kucheria R, Challacombe B, et al. Video consent: a pilot study of informed consent in laparoscopic urology and its impact on patient satisfaction. JSLS 2006;10:21–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bollschweiler E, Apitzsch J, Apitsch J, et al. Improving informed consent of surgical patients using a multimedia-based program? Results of a prospective randomized multicenter study of patients before cholecystectomy. Ann Surg 2008;248:205–11. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318180a3a7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gyomber D, Lawrentschuk N, Wong P, et al. Improving informed consent for patients undergoing radical prostatectomy using multimedia techniques: a prospective randomized crossover study. BJU Int 2010;106:1152–6. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09309.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang C, Ammon P, Beischer AD. The use of multimedia as an adjunct to the informed consent process for Morton’s neuroma resection surgery. Foot Ankle Int 2014;35:1037–44. 10.1177/1071100714543644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;4:CD001431 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hallock JL, Rios R, Handa VL. Patient satisfaction and informed consent for surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:181.e1–7. 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nehme J, El-Khani U, Chow A, et al. The use of multimedia consent programs for surgical procedures: a systematic review. Surg Innov 2013;20:13–23. 10.1177/1553350612446352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. UK C. UK smartphone penetration continues to rise to 85% of adult population UK: Consultancy.uk. 2017. https://www.consultancy.uk/news/14113/uk-smartphone-penetration-continues-to-rise-to-85-of-adult-population

- 31. Sacks GD, Lawson EH, Dawes AJ, et al. Relationship Between Hospital Performance on a Patient Satisfaction Survey and Surgical Quality. JAMA Surg 2015;150:858–64. 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.