Abstract

Introduction

Access to primary healthcare (PHC) has a fundamental influence on health outcomes, particularly for members of vulnerable populations. Innovative Models Promoting Access-to-Care Transformation (IMPACT) is a 5-year research programme built on community-academic partnerships. IMPACT aims to design, implement and evaluate organisational innovations to improve access to appropriate PHC for vulnerable populations. Six Local Innovation Partnerships (LIPs) in three Australian states (New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia) and three Canadian provinces (Ontario, Quebec and Alberta) used a common approach to implement six different interventions. This paper describes the protocol to evaluate the processes, outcomes and scalability of these organisational innovations.

Methods and analysis

The evaluation will use a convergent mixed-methods design involving longitudinal (pre and post) analysis of the six interventions. Study participants include vulnerable populations, PHC practices, their clinicians and administrative staff, service providers in other health or social service organisations, intervention staff and members of the LIP teams. Data were collected prior to and 3–6 months after the interventions and included interviews with members of the LIPs, organisational process data, document analysis and tools collecting the cost of components of the intervention. Assessment of impacts on individuals and organisations will rely on surveys and semistructured interviews (and, in some settings, direct observation) of participating patients, providers and PHC practices.

Ethics and dissemination

The IMPACT research programme received initial ethics approval from St Mary’s Hospital (Montreal) SMHC #13–30. The interventions received a range of other ethics approvals across the six jurisdictions. Dissemination of the findings should generate a deeper understanding of the ways in which system-level organisational innovations can improve access to PHC for vulnerable populations and new knowledge concerning improvements in PHC delivery in health service utilisation.

Keywords: primary health care, vulnerable populations, mixed methods, multi site

Strengths and limitations of this study.

International research programme designed to improve access to primary healthcare for vulnerable populations.

Community-academic partnerships in six regions in Australia and Canada.

Each intervention required mobilisation of local resources to match regional access needs and implement an intervention tailored to local context.

Interventions will be evaluated using a common methodology oriented to Levesque et al’s Access to Care Framework and an overarching logic model.

The study evaluation is limited by it being confined to six jurisdictions within two affluent Western nations. No rural communities were involved. Instruments were only available in English, French (in Canada) and Arabic (in New South Wales). The Victorian team worked with an accessible language service to develop Easy English versions of consent documents and questions within the patient survey.

Background

Recent and widespread reforms in primary healthcare (PHC) in Western countries reflect a growing concern that health systems should become more affordable, inclusive and fair.1 2 In Australia and Canada, PHC reforms prioritise access to effective and high-quality health services, with equity being at the heart of that system.3 4 Despite these reforms, meaningful gaps in equitable access to PHC remain.5–7 These gaps particularly affect vulnerable populations, such as poor, refugee and Indigenous communities7–13 and translate into unmet needs for care, delayed or inappropriate treatments, avoidable emergency department consultations and hospitalisations.5 14 Few PHC innovations directed at these needs have generated transformative change throughout healthcare systems.5

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research’s (CIHR) Community-Based Primary Health Care (CBPHC) Signature Initiative was designed to identify innovative approaches to improving the delivery of appropriate, high-quality community-based PHC.15 The Initiative, launched in 2013, promoted the development and comparison of innovative models for CBPHC delivery in Canada and/or internationally, research capacity building and knowledge translation to improve the delivery of CBPHC. The Initiative’s most significant investment involved funding 12 teams to conduct long-term intervention studies designed to improve access to CBPHC and/or chronic disease prevention and management for vulnerable populations. One of the 12 teams had an additional focus on Australian PHC through collaboration with the Australian Primary Health Care Research Institute’s Centre of Research Excellence programme. The successful applicant to the Canada/Australia funding opportunity was a consortium of researchers, clinicians and policy makers from three Australian states (New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia) and three Canadian provinces (Alberta, Ontario and Quebec).

The resulting programme, Innovative Models Promoting Access-to-Care Transformation (IMPACT),16 is a 5-year research programme built on a network of Local Innovation Partnerships (LIPs) bringing together decision makers, researchers, clinicians and, in some cases, members of vulnerable communities in each of the six regions. The LIPs collaborated in the design, implementation and evaluation of unique organisational interventions.

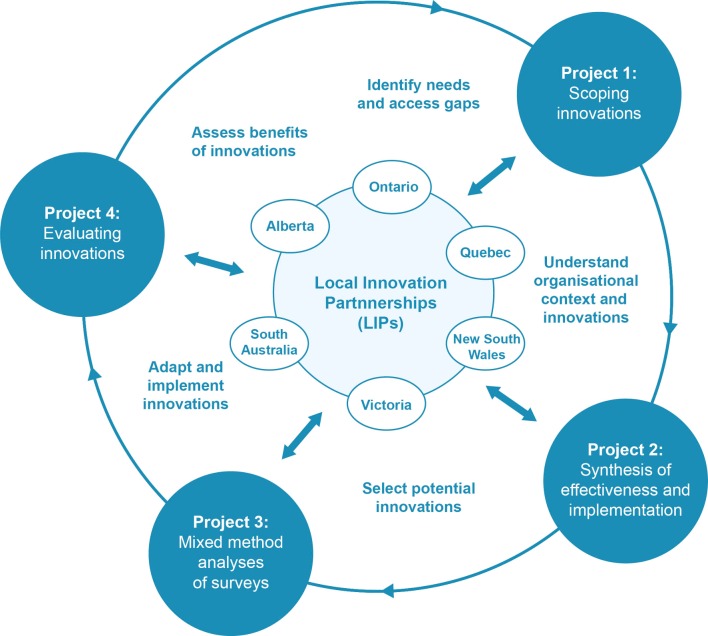

Figure 1 contains a schematic of the programme, descriptions of its overall design and details of three companion projects that informed the work of the LIPs.

Figure 1.

Overall design of the IMPACT programme. The work within the LIPs was informed by the findings of three separate inter-related initiatives (projects 1–3). We used two different approaches to identify effective and/or innovative organisational interventions designed to improve PHC access for vulnerable populations (project 1). The first was a scoping review mapping the existing evidence on PHC organisational access interventions that reported outcomes related to avoidable hospitalisation, emergency department admission or unmet healthcare needs.22 The second used a social media approach to conduct an environmental scan seeking innovative organisational interventions with a potential to improve access to community-based PHC for vulnerable populations.23 We conducted a series of realist reviews of the priority intervention chosen by each LIP (project 2). The reviews were coordinated by members of the international research team in collaboration with members of each LIP. The findings from the reviews informed the overall design of the interventions and helped LIPs identify key contextual factors and mechanisms relevant for each regional intervention. Further information on access in primary care was generated by a series of mixed-methods analyses of several Commonwealth Fund Surveys (2014 International Health Policy Survey of Older Adults and the 2013 survey of all adults)24–26 (project 3). This paper outlines the process that will be used for the evaluation of the innovations (project 4).

Work of the LIPs (inner circle in figure 1)

The programme began with the formulation of LIPs in each of six regional jurisdictions—three in Canada and three in Australia. The networks were set in communities where partnerships could be developed to address a priority gap in access to appropriate PHC for vulnerable populations.17 These learning networks of decision makers, researchers, clinicians and members of the community were, in most regions, built on pre-existing relationships between researchers, decision makers and clinicians.

Each LIP identified PHC access-related needs in their region by conducting PHC access needs evaluations (incorporating data from regional service providers and primary care organisations) to develop a profile of the demographic, economic and geographic characteristics of each LIP’s region. Findings were then presented to deliberative, consultative community forums that aimed to identify and prioritise each region’s PHC access-related needs.

Further forums then identified potential organisational innovations suitable and able to be implemented in each region. The potential innovations were reviewed by the LIP and informed by realist reviews18 conducted for each potential intervention. Finally, the most appropriate innovations were trialled and evaluated in the regions corresponding to each LIP. The CBPHC funding underwrote evaluation of the interventions but did not cover their implementation costs. Hence, teams in each region were charged with identifying resources to enable one of the priority needs to be addressed by an intervention.

Work within the partnerships was informed by a LIP Implementation Guide providing an overview of current thinking about implementation, core principles and specific checklists for helping the LIPs implement, improve and sustain their locally designed interventions.

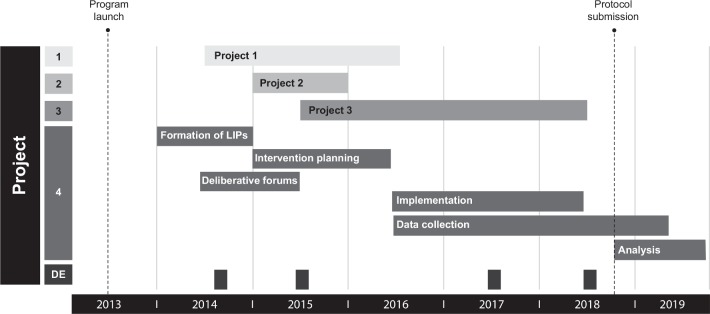

Interventions were implemented between June 2016 and June 2018. At the time of submission, data are still being gathered to inform components of the evaluation. Figure 2 shows a timeline of the research programme, including interventions, data collection and evaluation.

Figure 2.

Timeline of IMPACT activities. DE, developmental evaluation interviews; IMPACT, Innovative Models Promoting Access-to-Care Transformation.

This paper describes the approach that will be used to evaluate the effectiveness and further scalability of the interventions generated by the IMPACT programme. Evaluation used a common approach and a common set of tools; however, local and national modifications to the core methodology were encouraged.

Methods

Study aims and objectives

The objectives of the overarching IMPACT project are as follows:

To develop a network of partnerships between decision makers, researchers and community members to support the improvement of access to PHC for vulnerable populations.

To identify organisational, system-level CBPHC innovations designed to improve access to appropriate care for vulnerable populations and establish the effectiveness and scalability of the most promising innovations.

To support the selection, adaptation and implementation of innovations that align with regional partners' local populations’ needs and priorities.

To evaluate the effectiveness, efficiency and further scalability of these innovations.

This paper describes the evaluation approach to address the fourth programme objective and aims to explore:

The research programme’s support for the intervention.

The implementation of the intervention.

The impact of the intervention on patients, providers and practices and on healthcare utilisation.

These evaluation aims are expanded in the data analysis section. Our detailed, formal evaluation questions are listed in online supplementary appendix 1.

bmjopen-2018-027869supp001.pdf (400.7KB, pdf)

Design

Our evaluation will use a convergent mixed-methods design19 involving longitudinal (pre and post) evaluation of the implementation of interventions in regions associated with the six LIPs. Qualitative and quantitative data relevant to each intervention were collected in parallel, organised separately, then brought together to provide complementary evidence to answer the study’s research questions. Data collection for the evaluation used common tools administered before and 3–6 months after each intervention. This paper describes the strategy that will be employed to evaluate the collected data.

The evaluation (as with the larger programme) will be oriented to Levesque et al’s Access to Care Framework (see online supplementary appendix 2)20 and informed by a logic model (see online supplementary appendix 3) representing the mechanisms and potential consequences of the interventions. The Levesque framework views access to PHC as a dynamic process representing the interface between five dimensions of client abilities (ability to initiate, seek, reach, pay or engage) and five dimensions of service accessibility (approachability, acceptability, availability/accommodation, affordability and appropriateness). The scientific work of the study was informed by an International Expert Committee comprising leading primary care health services researchers from Europe, North America and New Zealand. The Committee was a committee of review, reflecting on and critically appraising the projects’ design, evaluation tools and approach to interpretation of key findings.

bmjopen-2018-027869supp002.pdf (273.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-027869supp003.pdf (344.2KB, pdf)

Setting

Table 1 outlines the characteristics of the six settings and vulnerable populations targeted by the interventions. Regions corresponding to the six participating sites are characterised by low socioeconomic status and diverse cultures (including high proportions of refugees and newly arrived migrants). Several regions contain substantial Indigenous communities.

Table 1.

Details of interventions in the six LIPs

| Canadian LIPs | Australian LIPs | |||||

| Alberta LIP | Quebec LIP | Ontario LIP | Victoria LIP | New South Wales LIP | South Australia LIP | |

| Targeted population | Individuals and groups of vulnerable populations living in North Lethbridge that have limited access to PHC. Includes immigrant, low income, Aboriginal, senior and homeless populations. | Orphaned patients (no PHC provider), particularly those in high deprivation neighbourhoods, newly assigned to family physicians through a centralised wait list. | Primary care patients, with strategies to ensure equitable access to community resources for socially vulnerable patients. | Vulnerable individuals who are clients of one of three community-based chronic disease services. Clients had at least one of the following characteristics: low socioeconomic status, socially isolated due to geographic distance/public transport inaccessibility, chronic illness or developmental disability. | Patients with poorly controlled diabetes attending practices in low socioeconomic localities. Specific subgroups: low socioeconomic status, culturally and linguistically diverse communities, refugee and humanitarian entrants. |

Aged and frail residents with complex/chronic health problems and high medical needs from three residential aged care facilities across the Adelaide metropolitan area. This population cohort is characterised by social isolation and reliance on others for the provision of care and thus can be extremely vulnerable. |

| Primary research question | What are the components of outreach and colocation as identified by vulnerable populations that contribute to making PHC services more approachable and engaging (eg, welcoming and unintimidating) for vulnerable populations in other contexts? | Can telephone contact from lay workers to vulnerable patients newly assigned to family practice clinics:

|

Can organisational changes be implemented within primary care practices to increase providers' and staff members’ awareness of community-based primary healthcare, support them to make appropriate referrals to community resources and address patients’ social barriers to reaching these resources? | Can a health service brokerage process involving PHC liaison workers and social service providers in the community:

|

For a vulnerable PHC population with chronic disease:

|

Can a PHC provider-led, multidisciplinary team approach to the management of chronic/complex conditions with a focus on fall prevention and end-of-life care result in improved access and provision of high quality, safe and effective PHC for residents of residential aged care facilities? Can this type of programme achieve reductions in hospital transfers, readmissions or relapse rates? |

| Intervention type | A pop-up service (a type of outreach) with a focus on cross team collaboration (eg, going to existing community events for hard-to-reach populations). | A telephone outreach service by lay volunteers to patients in deprived neighbourhoods newly assigned to family physicians to help them prepare for the first visit and explain important access-related issues. | A lay patient navigator supports primary care patients to reach community resources. Primary care practice providers and staff receive training and facilitation to increase their awareness of community resources, support them to identify patient needs that can be addressed by community resources, and refer and support their patients’ access to these resources. |

Community-based chronic disease services identify patients without an identifiable primary care provider. A broker then links identified patients to one of a panel of volunteer family practitioners. | Support access to PHC through a website that provides information and referral options to support diabetes self-management, facilitated by practice nurses at a health check visit in the PHC practice. | Participating residential aged care facilities implement a process of redesign of policies and procedures to improve consistency of primary care, in particular after-hour care. |

| Recruitment |

Patients

Principally by distribution of posters and postcards through existing service providers and at community businesses (eg, grocery store and so on), media release, radio advertisement and social media (Twitter and Facebook, via our team and also through participating service provider organisations). |

Patients

Members of the vulnerable population are residents from neighbourhoods with highest level of material and/or social deprivation based on postal code newly assigned by a centralised waiting list to family practices. Practices This LIP targeted possible clinics located in the LIP’s local territory. |

Patients

Eligible study participants are identified by their primary care provider and are those who are referred to a community resource by their primary care provider. Practices Practices with whom the research group has had a working relationship with form the pool of potential practices enrolled in the study. |

Patients

New and existing services clients who cannot identify a personal family physician or have not made contact with their family physician for 12 months or more. Practices Accredited primary care practices operating in the study region willing to provide care for new patients with access vulnerability. Practices needed to provide general primary care services and be willing to take on clients with access vulnerabilities. |

Patients

Eligible participants are patients aged 40–74 years attending the practice in the previous 2 years with type 2 diabetes with HbA1c >7 or BP >130/80 or BMI ≥30. Participants are invited by a mail invitation sent from the practice. Practices Family practices providing care for the target groups (socioeconomically diverse and Arabic-speaking practices) receive a written invitation from a Primary Health Network to participate. |

Patients

The residential aged care facility staff assist with identifying eligible residents. Residents must have the cognitive capacity to understand what is being asked of them and be able to give informed consent. Providers Clinical staff (physicians, nurse practitioners and nurses) who are employed by the residential aged care facility implementing the intervention or, in the case of some family physicians, have visiting arrangements to the relevant residential aged care facility. |

| Modifications to the core evaluation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; HbA1c, haemoglobin A1c; LIPs, Local Innovation Partnerships; PHC, primary healthcare.

Interventions

Patient and public involvement

The development of the interventions was informed by regional assessments of access-related need, formal community consultations and a series of research studies completed by the IMPACT team (see figure 1). In each region, formal community consultation comprised two deliberative forums with local decision makers, health and human service providers and community representatives to prioritise access needs for their vulnerable populations and develop a solution specific to local needs. Deliberative forums provided opportunities for members of the community to listen and negotiate through dialogue, creating mutual understanding and developing social capital.21 The first forum in each region identified priority primary care access gaps and the second focused on possible approaches to address these gaps. The research studies comprised: a scoping review of organisational interventions to improve access for vulnerable populations (project 1a)22; a search using email and social media to identify unpublished PHC access innovations (project 1b)23; a series of systematic reviews of the components of each intervention (project 2); and several access-oriented reanalyses of data generated by the Commonwealth Fund (project 3)24–26 (see figure 1).

Intervention design

The interventions ranged considerably in focus and mechanism. The Alberta LIP held a series of pop-up events where a range of health service and social welfare providers provided needed care in collaboration with members of a local, vulnerable community. Both Quebec and Victoria LIPs developed interventions to link consumers with a source of ongoing primary care. The Ontario intervention involved a lay, bilingual navigator integrated in primary care practices supporting patients to reach community resources to which they had been referred. South Australia worked with local service providers and decision makers to evaluate an aged care intervention to improve after-hours access to quality primary care. Finally, the New South Wales LIP implemented an intervention to improve diabetes care, including development of a website and health checks.

Study population

The interventions involved a range of participants, including vulnerable populations, PHC practices, their clinicians and administrative staff, service providers in other health or community and social service organisations, intervention staff and members of the LIP teams.

Study participants: vulnerable populations

All interventions were targeted at vulnerable populations, defined for this study as community members whose demographic, geographic, economic and/or cultural characteristics impeded or compromised their access to PHC. The specific social vulnerability of the study population varied based on the priority established in each of the six regions. They included residents of aged care facilities, diabetics within immigrant populations, people living with chronic disease and community members in regions with limited supply of primary care professionals.

Study participants: healthcare providers

Most of the interventions involved the participation of family physicians, non-physician clinicians (eg, nurses and social workers) and administrative staff working within family practices. Several sites included participants from members of health, social service or community organisations, in which case participants included administrative staff, clinicians, managers and, in some sites, directors or executives of these organisations.

Study participants: intervention staff

The composition and nature of intervention staff varied between LIP interventions. Different sites used lay and health professional navigators, family practice nurses, allied health professionals, healthcare managers, community service providers, residential aged care nurses, trainers and intake/screening staff.

Study participants: members of LIPs

Each LIP had a research team and a broader advisory/reference group (‘LIP Core team’). The research team comprised study investigators and research associates. The LIP Core team in each region comprised, in general, an IMPACT principal investigator, a LIP lead (responsible for the function of the LIP), a LIP coordinator (a field worker responsible for coordinating, documenting and managing the work of the LIP), decision makers, other researchers, clinicians and members of the community.

Measures

The study evaluation will rely on data collected during the implementation and follow-up of the interventions. The study measures are grouped in terms of their focus on patients and healthcare providers, intervention staff and members of LIPs.

Measures gathering data from consumers and healthcare providers

Quantitative data measures

We developed four different survey instruments (questionnaires) for patients, healthcare providers (family practitioners and nurses), family practices and staff within health and community services. Since the impact of the intervention on the participants will be determined by comparing responses before and after the intervention, the questions in the postintervention questionnaires duplicated many of the preintervention questions. These were combined with additional questions about the respondents’ intervention experiences.

As with other projects funded by the CBPHC initiative, the patient, provider and practice surveys were adapted from a number of previously used instruments, including surveys originating from an initiative of the Canadian Institute for Health Information,27 and supplemented by additional questions developed for this study (table 2). Each questionnaire was piloted prior to finalisation. All surveys were available in English and French (for Canadian administration to English-speaking and French-speaking populations). The New South Wales LIP developed an Arabic version of the patient survey, and the Victorian team worked with an accessible language service to develop Easy English versions of the patient survey and associated consent documents.

Table 2.

Survey measures

| Survey | Informed by or adapted from existing instruments or studies |

| Patient survey | Primary Care Assessment Tool42; Primary Care Assessment Survey43; EQ-5D-5L44; Veterans RAND 12-item Health Survey45; Canadian Survey of Experiences with Primary Health Care46; Perceived Need for Care Questionnaire47; Canadian Community Health Survey48; Patient Perception of Patient-Centeredness49; GP Patient Survey50; Interpersonal Processes of Care Survey51; and Health Literacy Questionnaire52 The patient survey was translated into French, Arabic and Easy English where required. |

| Provider survey | Comparison of Models of Primary Care in Ontario study53; Preventive Evidence into Practice study54; National Pain Strategy55; and Community-Based Primary Health Care Common Indicator Project.56 |

| Practice survey | Community-Based Primary Health Care Common Indicator Project.56 |

| Organisational survey | Evaluation of the Primary Care Partnership Strategy. Victoria, Australia.57 |

EQ-5D-5L, EuroQoL 5-dimension 5-level.

The patient survey provides data on participating patients’ ability to access PHC (including ability to perceive, seek, reach, pay and engage), experiences with and utilisation of healthcare services, relationships with PHC providers, links with community and other healthcare services, engagement with primary medical care and the appropriateness of healthcare received. It includes measures of the patient’s experience of PHC (appropriate care and referrals) and information on general health and demographics. The survey was administered either face-to-face or by telephone.

The provider survey was completed by primary care clinicians responsible for direct patient care (either family practitioners or nurses/nurse practitioners). Questions explore the range of vulnerable patients cared for and their experience, confidence and clinical activities used in managing the specific vulnerable population targeted by the LIP. Demographic information includes questions about age, gender, site of professional training, professional experience and hours of work.

The practice survey ascertains the structural and organisational characteristics of PHC clinics (usually general/family practices). The survey captures details on the participating clinic’s patient population, services, procedures and policies, especially as related to vulnerable patients. It also seeks information on staffing, funding sources, collaborative arrangements and communication infrastructure. It was completed by the most relevant individual at each practice site (generally either the lead physician or, where available, practice manager).

The organisational (health and community services provider) survey was administered in sites where these organisations were involved in the intervention. The survey includes items from the PHC surveys where relevant, with the addition of questions used in previous evaluations of state-wide partnership-based health system reform strategies. The survey focuses on each organisation’s internal policies, procedures, practices and relations with external service providers and PHC providers. It was completed by health and community service workers and/or managers participating in the interventions. Individual LIPs supplemented these tools, as needed, to address the informational needs specific to their context.

Qualitative data

In-depth qualitative data were collected using semistructured interviews with patients and PHC providers. In general, interviews with patients and PHC providers were conducted before and 3–6 months after the completion of the intervention. All interviews were aided by interview guides aligned to components of the Access to Care Framework20 and the local logic models. The guides were tailored at each site to reflect features of the local intervention. Question sequencing was flexible, allowing participant responses to guide the course of the interview. Contact summary sheets were prepared after each interview to document interviewer reflections and their developing understanding of emerging answers to the research questions.28

Patient interviews

Most sites limited preintervention qualitative data collection from patients to two open-ended questions that, in conjunction with a series of prompts, asked patients to describe their prior experiences with seeking and reaching primary care. These questions were administered in conjunction with the patient survey. Postintervention interviews investigated patients’ experience with the intervention, the intervention’s perceived acceptability and the impact on the patient’s ability to access primary care.

PHC provider interviews

Preintervention provider interviews explored existing organisational and individual approaches relating to the provision of accessible primary care to vulnerable populations. Postintervention interviews explored how the intervention influenced usual routines (organisational and individual) relating to access of vulnerable patients (frequency of actions such as information giving, referrals and so on) and adoption by providers. Providers were asked about the impact of the intervention on their own and the practice’s work and on the perceived feasibility of its broader implementation.

Non-participant observation in PHC settings

The Canadian sites compiled a comprehensive profile of the contextual, organisational and physical structure of a sample of PHC practice settings involved in the interventions. The profile was based on a modified tool previously used in the collection of observational data from family practices.29 30 Observers documented the physical space of the practice, front desk and administrative staff scheduling procedures and routines, staff interactions, practice flow and other waiting room/reception desk activities. These observations were focused on activities relevant to vulnerable patients’ access and were recorded as field notes.

Measures gathering data from intervention staff

Interviews with intervention staff and/or members of health and community services were conducted in some LIPs. These interviews explored their involvement in the delivery of the intervention and their perceptions concerning the sustainability of the intervention’s activities.

Expense diaries

Intervention staff gathered data on the cost of all non-research activities undertaken as part of the interventions that incur a cost or opportunity cost (eg, use of existing resources), including staff time (hourly salary), consumables/operating costs (eg, telephone calls and printing), travel, one-off costs (eg, website development) and rental of accommodation.

Navigator records

Several of the interventions used health navigators to assist with patient access to care. For these interventions, we collected navigator field diaries, minutes of meetings between navigators and the study teams and materials and evaluation reports from the educational events associated with the intervention.

Measures gathering data from members of local innovation partnerships

The study’s process evaluation will rely on data from interviews with LIP Core Team and Research Team members. These were conducted in four cycles (2014, 2016, 2017 and 2018) by independent research assistants not associated with any of the LIPs. Each site’s LIP lead, LIP coordinator and other research staff participated in interviews at these time points assessing their perceptions of how the programme was organised, including governance (international/national executive committees, project organisation and so on), approaches to researcher and stakeholder collaboration (LIPs), organisation of staff and communication. Non-researcher members of the LIP Core Teams were also interviewed at several time points at most sites.

LIP coordinators documented the development and characteristics of their region’s intervention. All coordinators kept a diary that recorded key events during the development and implementation of the intervention.

Data collection

Surveys

We used the software program Qualtrics 31 to organise survey data. Trained members of the research team working in each region administered surveys either in-person or over the telephone. PHC professionals and practice staff were also able to self-complete their questionnaires using a paper version. Self-completed questionnaires were then imported into Qualtrics.

Interviews

In-depth semistructured interviews were conducted by trained interviewers face-to-face or over the phone, depending on participants’ availability. In each case, interviews were audio-recorded. In the three Australian LIPs, the recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim. In Canada, narrative summaries (ie, purposeful transcription) of the interviews were created by researchers who conducted the interviews. All qualitative interview data were managed using the QSR International’s server-based software NVivo for Teams.32

Non-participant observations were recorded as field notes by research staff attending participating PHC practices during the intervention. The number of observations varied by LIP and depended on the interventions’ method and mechanism of implementation. Each observation session lasted approximately 1 hour and was recorded as a field note.

Data management

All qualitative and quantitative data associated with the interventions were collected locally and labelled with a unique participant number. Common rules were followed for naming variables and coding data to facilitate merging and mixed-methods analysis. For the analysis, both the qualitative and the quantitative data sets are stored in a central data repository. Separate qualitative and quantitative analytic teams have been established to assist in the implementation of the evaluation plan. These will evolve into teams focused on additional analyses generating manuscripts and other outputs.

Data analysis

Evaluation questions have been formulated to guide the analysis of the set-up, implementation and impact of the organisational interventions. The formal questions are included in online supplementary appendix 1.

Evaluation question 1: the research programme’s support for the intervention

The first evaluation question uses a developmental evaluation approach to explore how the overall programme’s approach to governance, relationships and processes influenced the design, development, implementation and sustainability of the interventions.

We collected data about how the programmes were planned, implemented and evaluated.33 The process evaluation focuses on all aspects of the development and implementation of the IMPACT programme, with a particular focus on the evolution of work within each LIP. This process, conducted through reports and discussions after each round of data collection, has contributed to ongoing reflection by the IMPACT team about the way the research programme has evolved.

Data sources include semistructured interviews with LIP Core Team and Research Team members, routinely collected documents (including minutes of meetings) and, in some LIPs, interviews with partners and stakeholders. The analysis of the first evaluation question will involve a hybrid deductive–inductive content thematic analysis.34 The initial round of analysis will include identification of themes, codes and keywords based on analysis of notes and interview transcripts. The process will be iterative, and members of the research team will review the initial codes. To ensure coding reliability between the intervention sites, one qualitative researcher will separately and independently code two Australian and two Canadian interviews. All issues identified will be discussed by the team and further analysis then undertaken.

Evaluation question 2: the implementation of the intervention

The second evaluation question seeks to identify whether the interventions were implemented as planned and to ascertain the contextual factors influencing the intensity and fidelity of the interventions. Here, the unit of analysis will be the intervention implemented at each of the six sites; each intervention is a case. Overall, we will use an embedded qualitative design where the majority of the analyses will depend on qualitative data routinely collected during the interventions.

Data sources include the measures used to gather data from intervention staff and from members of the LIPs (see above). Sites used additional processes to track implementation fidelity. Some measured the degree to which patients attended health checks or practices to which they had been linked. Others captured detail of patient assessments, use of intervention components (ie, websites) and referral destination.

LIP coordinators in each site will use their diaries, along with minutes of meetings of the LIP partnerships, to help generate two summary documents: (A) the Template for Intervention Description and Reporting, a template for describing the characteristics of each intervention35 and (B) perceived contextual influences on the implementation and fidelity of each intervention arranged within a self-designed template, based on Stange and Glasgow’s approach to reporting contextual influences on the patient-centred medical home.36 Both documents are further informed by each region’s demographic data and access needs assessments conducted early in each LIP’s development. A central analysis team will combine this data with documentation of outputs from the deliberative forums as well as summarised data from the developmental evaluation.

The validity of the data will be checked using a member checking approach37 where summaries are shared with and corroborated by LIP coordinators, LIP leads and core team members.

Finally, the analysis team will use a cross-case synthesis analytic technique incorporating constant comparative analysis where resulting data can be compared. Summaries will be coded, then node extracts will be reviewed and matrices will be developed, comparing the interventions across thematic domains. We will use May’s ecological model of the ways that context interacts with participants and interventions as a lens to explore the data.38

Evaluation questions 3 and 4: evaluation of the impact of the intervention on patients, providers, practices and on healthcare utilisation

Evaluation question 3 considers how the interventions influenced: (1) patient participants’ abilities to access appropriate PHC; (2) providers’ knowledge and confidence to support the care of vulnerable patients; and (3) practice processes and policies to support vulnerable patients’ access to appropriate primary care.

Evaluation question 4 seeks to ascertain the effect of the interventions on: (1) enduring relationships with PHC; (2) appropriateness of referrals; (3) use of comprehensive primary care; (4) continuity; and (5) use of emergency departments and hospitals for ambulatory care sensitive conditions.

This component of the evaluation will be addressed with a convergent mixed-methods design, informed by Levesque et al’s Access to Care Framework20 and the project’s logic model (see online supplementary appendix 3). Analysis will first take place at the level of the LIP intervention by local analysts who will identify the dimensions of access within the logic model that would be influenced by the intervention.

Quantitative analysis will begin with data cleaning and, dependent on sample sizes, exploratory factor analysis so that items with high communality can be combined, thus reducing problems associated with running multiple statistical tests.39 In each LIP, the distribution of test variables will be checked to ensure they meet the assumptions of the statistical test for which they were used. For example, variables for which a ceiling or floor effect is evident will be excluded.

First, we will seek to identify change between variables measured in preintervention and postintervention surveys at the level of each LIP intervention by creating change scores (postintervention minus baseline responses). We will then assess predictors of change (where sample size is sufficient) beginning with bivariate tests for relationships between predictors (ie, patient age or gender, practitioner type and practice size) and change scores prior to conducting multivariate analyses of predictors of change scores based on statistically significant univariate analyses. Where sample size is not sufficient, a case study or qualitative approach will be used to consider factors that might have influenced the results.

Sample size varied across interventions. In terms of patient-level data, we require interventions being included in the quantitative components of the final evaluation to have at least 25 patients with data available for analysis

Qualitative analysis: conceptual phrases from the Access to Care Framework20 will be attributed to segments of data from preintervention interviews of patients and providers using structural coding techniques.40 The similarly coded segments will then be collated for more detailed coding and analysis using an inductive approach. A similar process will be applied for postintervention patient and provider interview data. The coding for preintervention and postintervention data will then be compared for each domain of the framework noting changes that can be attributed to the intervention. Each LIP will then develop case studies generated from the analytic plans and designed around the components of the questions that fitted the logic of each intervention.

Cross case analysis: the analysis between the LIPs will be informed by Crabtree et al’s41 approach to meta-synthesising results where investigators who conducted the original projects are part of the analysis team. This approach incorporates tacit knowledge from investigators and other products of the research programme into the overall analysis. We will begin by identifying aspects of the evaluation questions where data exists to be able to generate valuable insights for policy makers, clinicians, vulnerable communities and researchers. The analysis will be performed by a team comprising at least one member of each of the LIPs.

Ethics and dissemination

The IMPACT research programme received ethics approval from St Mary’s Hospital Montreal SMHC #13–30. The varied interventions received other ethics approvals across the six jurisdictions. Ethics applications were tailored to the needs of the vulnerable populations included in the study and to the sometimes complex requirements of health services implementing components of the study. At times, this required additional tailoring of the survey tools, in particular the patient questionnaires. The findings will be shared through a range of activities.

During the course of the study, a monthly newsletter has been made available to study participants, collaboration partners and the interested public to inform them about the progress of the study and its results. This newsletter is disseminated via a mailing list and remains available for download on the project website (www.impactresearchprogram.com). Updates on the study are also communicated via IMPACT’s Twitter account (@IMPACT_PHC). Policy and practice summaries will be developed and made available to decision makers through collaboration partners and plain language press releases. The results will be disseminated in scientific journals and will be presented at relevant international and national conferences. To ensure high accessibility, we aim to publish our work in open access journals. Outcomes should help inform the work of others grappling with similar access problems.

Discussion

The protocol outlines the approach for the evaluation of a large-scale, multisite programme, built on community–academic partnerships and designed to address important challenges or barriers in the delivery of accessible, high-quality PHC to vulnerable communities. The programme of work is complex and requires cooperation and collaboration between diverse teams at local, national and international levels. The diversity of targeted vulnerable populations and differences in the interventions trialled has challenged planning, data management and measurement.

Nevertheless, as the multiple facets of the evaluation are addressed, we anticipate rich insights into the evolving field of primary care health services research and primary care-oriented community–academic partnerships. Lessons from this evaluation will inform governments and communities who wish to improve access to CBPHC about the conditions necessary to ensure that innovations such as these can be adapted and scaled up. The strong partnerships between communities, providers, policy makers and researchers will ensure that these innovations are most relevant and have the best chance of being implemented broadly in the respective systems.

The programme of work within IMPACT has already identified the promise of formal integration of services to improve access to primary care services for vulnerable populations,22 the prevalence of effective but unpublished PHC access interventions23 and the factors associated with multiple barriers to primary care.24 Our systematic reviews provide rigorous information on the effectiveness of several innovations, as well as on their scalability in different contexts and anticipated economic impact.

For the broader PHC community, the results of evaluations of the evolution of the partnerships and the impact of the interventions will provide a better understanding of the influence of context in the implementation of community-focused access interventions and significant new data on mechanisms supporting the implementation of community–academic partnerships. The evaluation will provide unique insights into how innovations work in different contexts and both their direct, indirect and unanticipated impacts. Resorting to a clear logic conceptualisation of PHC systems will enable us to identify relevant organisational levers and contextual influences that can be harnessed to create sustainable and scalable changes in CBPHC to favour access for the vulnerable.

The work should generate a deeper understanding of the ways in which system-level organisational innovations can improve access to PHC for vulnerable populations and new knowledge concerning improvements in PHC delivery in health service utilisation.

This work will be uniquely relevant to real-world implementation of new policy and programme options for improving access to PHC care by vulnerable populations in a range of contexts and systems. The findings will contain a rich source of practical experience and examples of applications of innovations to inform the work of others grappling with similar complex access problems.

Registration

Given that the IMPACT study was an exploratory evaluation of six health service innovations using a mixed methods approach and a before–after design and that the assignment of the medical intervention was not at the discretion of the investigators, we followed the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (http://www.icmje.org/about-icmje/faqs/clinical-trials-registration/) in not registering the overall study. The Ottawa intervention secured funding to subsequently incorporate a clinical trial, which was recently described in JMIR Research Protocols (available at https://www.researchprotocols.org/2019/1/e11022/) and has a trial registration number NCT03105635 at ClinicalTrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03105635/).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like thank all members of the Local Innovation Partnerships who contributed to the design of the study. In addition, we would like to thank Dr Lisa Starr, Dr Phillip Thompson, Ms Annette Peart and Ms Sophie Lim for their assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: GR, J-FL, MH, CSc, SDa, VL, SDe, NS and JH designed the study. MK, CSp, JA and ED provided further design input following funding. GR, SDe and MK led the writing of this manuscript, and all authors approved the final version.

Funding: The IMPACT study is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (TTF-130729) Signature Initiative in Community-Based Primary Health Care, the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé and the former Australian Primary Health Care Research Institute, which is supported by a grant from the Australian Government Department of Health under the Primary Health Care Research, Evaluation and Development Strategy.

Disclaimer: The information and opinions contained in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views or policy of these funding agencies or the Australian Government Department of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study has been approved by the relevant Human Research Ethics Committees at each study site in Australia and Canada.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. 2008. A Summary of the 2008 World Health Report "Primary Health Care: Now More Than Ever". Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Canadian Institute for Health Information. 2008. Reducing gaps in health: a focus on socio-economic status in Urban Canada. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Institute for Health Information. [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission. 2009. A healthier future for all Australians. Final report of the National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission. Canberra, Australia. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hutchison B, Levesque JF, Strumpf E, et al. . Primary health care in Canada: systems in motion. Milbank Q 2011;89:256–88. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00628.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Levesque JF, Pineault R, Hamel M, et al. . Emerging organisational models of primary healthcare and unmet needs for care: insights from a population-based survey in Quebec province. BMC Fam Pract 2012;13:66 10.1186/1471-2296-13-66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Harris MF. Access to preventive care by immigrant populations. BMC Med 2012;10:55 10.1186/1741-7015-10-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Asada Y, Kephart G. Equity in health services use and intensity of use in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res 2007;7:41 10.1186/1472-6963-7-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bowen S. Access to health services for underserved populations in Canada. Ottawa, Canada: Health Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Haggerty JL, Pineault R, Beaulieu MD, et al. . Practice features associated with patient-reported accessibility, continuity, and coordination of primary health care. Ann Fam Med 2008;6:116–23. 10.1370/afm.802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Marshall EG, Wong ST, Haggerty JL, et al. . Perceptions of unmet healthcare needs: what do Punjabi and Chinese-speaking immigrants think? A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:46 10.1186/1472-6963-10-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harris MF, Furler J, Valenti L, et al. . Matching care to need in general practice: A secondary analysis of BEACH data. Aust J Prim Health 2004;10:151–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Spike EA, Smith MM, Harris MF. Access to primary health care services by community-based asylum seekers. Med J Aust 2011;195:188–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Khandor E, Mason K, Chambers C, et al. . Access to primary health care among homeless adults in Toronto, Canada: results from the Street Health survey. Open Med 2011;5:e94–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McCusker J, Tousignant P, Borgès Da Silva R, et al. . Factors predicting patient use of the emergency department: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ 2012;184:E307–16. 10.1503/cmaj.111069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Community-Based Primary Heatlh Care: Canadian Institutes of Health Research. 2018. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/43626.html [Accessed 18 Jun 2018].

- 16. Levesque J-F, Russell GM, Haggerty J, et al. . Innovative Models Promoting Access-to-Care Transformation (IMPACT). Montreal, Canada Melbourne, Australia: Canadian Institutes for Health Care Research Australian Primary Health Care Research Insitute, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Scammon DL, Tomoaia-Cotisel A, Day RL, et al. . Connecting the dots and merging meaning: using mixed methods to study primary care delivery transformation. Health Serv Res 2013;48(6 Pt 2):2181–207. 10.1111/1475-6773.12114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, et al. . Realist review--a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10(Suppl 1):21–34. 10.1258/1355819054308530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Creswell J, Clark P V. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 3rd edn Los Angeles, USA: SAGE Publications, Inc, 2018:452. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Levesque JF, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health 2013;12:18 10.1186/1475-9276-12-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. MacNeil C. Evaluator as steward of citizen deliberation. Am J Eval 2002;23:45–54. 10.1177/109821400202300105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Khanassov V, Pluye P, Descôteaux S, et al. . Organizational interventions improving access to community-based primary health care for vulnerable populations: a scoping review. Int J Equity Health 2016;15:168 10.1186/s12939-016-0459-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Richard L, Furler J, Densley K, et al. . Equity of access to primary healthcare for vulnerable populations: the IMPACT international online survey of innovations. Int J Equity Health 2016;15:64 10.1186/s12939-016-0351-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Corscadden L, Levesque JF, Lewis V, et al. . Factors associated with multiple barriers to access to primary care: an international analysis. Int J Equity Health 2018;17:28 10.1186/s12939-018-0740-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Corscadden L, Levesque JF, Lewis V, et al. . Barriers to accessing primary health care: comparing Australian experiences internationally. Aust J Prim Health 2017;23:223–8. 10.1071/PY16093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Holdsworth S, Corscadden L, Levesque JF, et al. . Factors associated with successful chronic disease treatment plans for older Australians: Implications for rural and Indigenous Australians. Aust J Rural Health 2019. 10.1111/ajr.12461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Access data and reports Canada. 2018. https://www.cihi.ca/en/access-data-reports/results?query=survey&Search+Submit [cited 19 September 2018].

- 28. Miles M, Huberman M. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 2nd edn Los Angeles, USA: SAGE Publications, Inc, 1994:338. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Balasubramanian BA, Chase SM, Nutting PA, et al. . Using Learning Teams for Reflective Adaptation (ULTRA): insights from a team-based change management strategy in primary care. Ann Fam Med 2010;8:425–32. 10.1370/afm.1159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Russell G, Advocat J, Geneau R, et al. . Examining organizational change in primary care practices: experiences from using ethnographic methods. Fam Pract 2012;29:455–61. 10.1093/fampra/cmr117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Qualtrics. Qualtrics. September 2018 edn Provo, Utah, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32. QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo qualitative data analysis software. Version 10. 2012.

- 33. Patton MQ. Developmental evaluation: applying complexity concepts to enhance innovation and use. New York, USA: Guilford Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pluye P, Hong QN. Combining the power of stories and the power of numbers: mixed methods research and mixed studies reviews. Annu Rev Public Health 2014;35:29–45. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. . Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:g1687 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stange KC, Glasgow RE. Considering and reporting important contextual factors in research on the patient-centered medical home. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cohen DJ, Crabtree BF. Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: controversies and recommendations. Ann Fam Med 2008;6:331–9. 10.1370/afm.818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. May CR, Johnson M, Finch T. Implementation, context and complexity. Implement Sci 2016;11:141 10.1186/s13012-016-0506-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 6th edn Boston MA: Pearson Education, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. London: Sage, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Gunn JM, et al. . Uncovering the wisdom hidden between the lines: the Collaborative Reflexive Deliberative Approach. Fam Pract 2018;35:266–75. 10.1093/fampra/cmx091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shi L, Starfield B, Xu J. Validating the Adult Primary Care Assessment Tool. J Fam Pract 2001. 50;161. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Safran DG, Kosinski M, Tarlov AR, et al. . The Primary Care Assessment Survey: tests of data quality and measurement performance. Med Care 1998;36:728–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. . Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011;20:1727–36. 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Iqbal SU, Rogers W, Selim A, et al. . The Veterans RAND 12 Item Health Survey (VR-12): What it is and how it is used. 2007. https://www.bu.edu/sph/files/2015/01/veterans_rand_12_item_health_survey_vr-12_2007.pdf.

- 46. Statistics Canada. The Canadian Survey of Experiences with Primary Health Care 2007-2008, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Meadows G, Harvey C, Fossey E, et al. . Assessing perceived need for mental health care in a community survey: development of the Perceived Need for Care Questionnaire (PNCQ). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2000;35:427–35. 10.1007/s001270050260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Béland Y. Canadian community health survey--methodological overview. Health Rep 2002;13:9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al. . The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract 2000;49:796–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Campbell J, Smith P, Nissen S, et al. . The GP Patient Survey for use in primary care in the National Health Service in the UK – development and psychometric characteristics. BMC Fam Pract 2009;10:57 10.1186/1471-2296-10-57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Stewart AL, Nápoles-Springer AM, Gregorich SE, et al. . Interpersonal processes of care survey: patient-reported measures for diverse groups. Health Serv Res 2007;42(3 Pt 1):1235–56. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00637.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Osborne RH, Batterham RW, Elsworth GR, et al. . The grounded psychometric development and initial validation of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health 2013;13:658 10.1186/1471-2458-13-658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rowan MS, Hogg W, Labrecque L, et al. . A theory-based evaluation framework for primary care: setting the stage to evaluate the "Comparison of Models of Primary Health Care in Ontario" project. Can J Program Eval 2008;23:113–40. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Harris MF, Lloyd J, Litt J, et al. . Preventive evidence into practice (PEP) study: implementation of guidelines to prevent primary vascular disease in general practice protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Implement Sci 2013;8:8 10.1186/1748-5908-8-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pain Australia. National Pain Strategy. Pain management for all Australians. 2011. https://www.painaustralia.org.au/static/uploads/files/national-pain-strategy-2011-wfvjawttsanq.pdf (Accessed 18 Jul 2019).

- 56. Wong ST, Langton JM, Katz A, et al. . Promoting cross-jurisdictional primary health care research: developing a set of common indicators across 12 community-based primary health care teams in Canada. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2019;20:e7 10.1017/S1463423618000518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Swerissen H, Wilson G, Lewis V, et al. . An Evaluation of the primary care partnership strategy: report 3. Melbourne, Australia: Australian Institute for Primary Care, LaTrobe University, 2003:44. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-027869supp001.pdf (400.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-027869supp002.pdf (273.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-027869supp003.pdf (344.2KB, pdf)