Abstract

Regulatory approvals for the marketing of medicinal products authorize medical practitioners to prescribe drugs to a group of patients that are defined within the license of the medicinal product. However, such prescriptions are carried out in a controlled manner. Prior to being approved, the medicinal product will have been evaluated in a population pool containing fewer than 5,000 patients and in a predesigned environment where several factors may be lacking, such as the absence of women of childbearing potential, geriatric patients and paediatric patients. Therefore, it is not surprising that several major adverse drug reactions are detected only when the product has been prescribed to the general population. National and international regulatory bodies have devised systems for monitoring medicinal products after marketing, commonly known as postmarketing surveillance systems. Postmarketing surveillance refers to the process of monitoring the safety of drugs once they reach the market, after the successful completion of clinical trials. The primary purpose for conducting postmarketing surveillance is to identify previously unrecognized adverse effects as well as positive effects. The Yellow Card scheme, practiced in the United Kingdom and the Canada Vigilance Program adopted in the Canadian jurisdiction, are two of the most successful postmarketing surveillance systems implemented across the world. Therefore, this article intends to discuss postmarketing surveillance and its role in the context of the United Kingdom and Canadian jurisdictions with a view on presenting key aspects and measures that are employed for operating an efficient postmarketing surveillance system in regulated markets.

Keywords: adverse drug reactions, black triangle drugs, Health Canada, MHRA, postmarketing surveillance, Yellow Card scheme

Introduction

In the field of pharmaceutical sciences, drug innovation is a continual process that more often than not culminates in the discovery of potential new medicines. The development of a drug, right from conceptual stages to the finished product, is considered to be a highly complex process that scrutinizes every little aspect of the drug, thereby providing adequate assurance of its safety at the time of approval. However, to further ascertain the safety of new drugs for human consumption, investigative studies tend to continue after approval. These studies are commonly called ‘postmarketing studies’ or ‘phase IV trials’.

Postmarketing surveillance (PMS), in simple terms, refers to the process of monitoring the safety of drugs once they reach the market after the successful completion of clinical trials.1 The primary purpose for the conduct of PMS is to identify previously unrecognized adverse effects as well as positive effects. Other essential components can include off-label drug use, issues with orphan drugs and problems associated with the conduct of international clinical trials in the paediatric population.2

While premarketing trials are conducted with the intention of establishing the toxicity profile of a drug, they are frequently found to be lacking in capacity when it comes down to the detection of important adverse drug reactions (ADRs). This can be attributed to limitations in the number of participants in the trials, as some ADRs may be observed at rates of 1 in 10,000 or fewer drug exposures. ADRs are defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as ‘a response to a drug that is noxious and unintended and occurs at doses normally used in man for the prophylaxis, diagnosis or therapy of disease, or for modification of physiological function’. They have different categories such as dose-related, nondose-related, time-related and unexpected failure of therapy.3 Follow ups are integral to the detection of adverse reactions associated with the long-term use of drugs or the intake of drugs at widely separated intervals. Taken as a whole, the shortcomings posed by premarketing trials necessitate the conduct of continual investigative studies after drug approval.

PMS is an essential tool that helps to correlate the strength of the exposed drug with that of the adverse events, thereby painting a clearer picture with regard to the types of positive or negative effects that a drug may threaten to pose, over a prolonged period of administration.

Over the years, PMS practices have undergone considerable evolution, with regulatory authorities realizing the importance of applying appropriate measures to stifle the increasing incidences of adverse reactions. This has ushered in an era of ‘proactive approaches’ rather than ‘reactive approaches’ with a focus on risk prevention and necessary communication measures. Examples of this can be seen in the United Kingdom (UK) and Canada, two of the most regulated pharmaceutical markets in the world.

In 2013, an average of 176 out of 100,000 people reported an adverse event in the UK.4 Similarly, around 200,000 ADRs are reported in Canada every year, of which up to 22,000 resultant deaths are reported.5 These statistics were accountable for reported ADRs only, and it is widely believed that around 90% of ADRs go unreported. However, in the years to come, these stats are expected to reflect more accurate numbers with the implementation of a more robust PMS and pharmacovigilance (PV) system.

Therefore, it is prudent to review the specific components and processes involved in the reporting of adverse events, and analyse how the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in the UK and Health Canada in Canada, are likely to show similarities and disparities in the manner in which the PV systems are regulated.

Discussion

Postmarketing surveillance: MHRA

PMS or pharmacovigilance in the UK is practiced in the form of the Yellow Card scheme that is jointly operated by the MHRA and the Committee of Human Medicines (CHM). The Yellow Card scheme is credited as being one of the first PV schemes aimed at mitigating ADRs.6 PV encompasses the following objectives:7

➢ Monitoring the use of medicines in everyday practice with the aim to identify erstwhile unrecognized ADRs and also changes in the patterns of adverse effects.

➢ Carrying out risk–benefit analysis for medicines and suggesting suitable actions, if and when necessitated.

➢ Providing regular updates to healthcare professionals and patients with regard to the safe and efficacious use of medicines.

In addition to the Yellow Card scheme, the MHRA brought into effect an updated black triangle scheme in 2009 that was aimed at increasing the awareness of healthcare professionals and the public in general towards drugs and vaccines that required intensive monitoring. Any suspected adverse effects caused by such drugs and vaccines were to be immediately brought to the attention of the MHRA and the CHM. The symbol, which is denoted by an inverted black triangle, is found imprinted beside the name of the relevant drug product.

History of the Yellow Card scheme

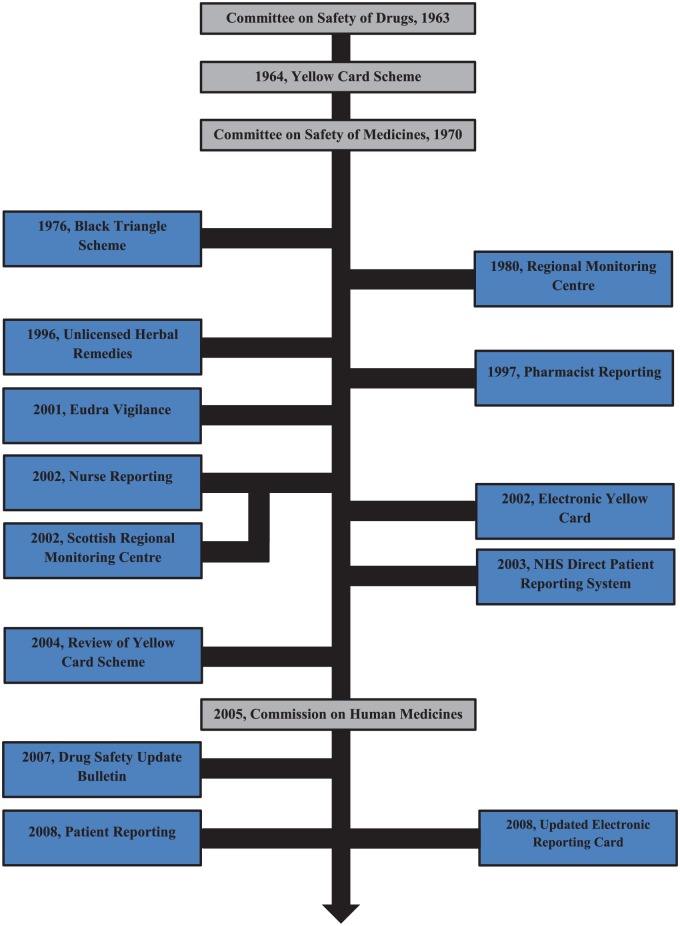

Figure 1 illustrates the key events in the history of the Yellow Card scheme.8 The scheme, established in 1964, was an outcome of the thalidomide tragedy that occurred in the early 1960s. This Yellow Card reporting system, based on the concept of voluntary reporting of suspected adverse reactions, is considered to be one of the first ADR reporting systems in the world. From the inception of the scheme until 1997, the reporting system was open only to doctors and dentists and therefore was restrictive in nature. However, from early 1997 onwards, the scope of the scheme was considerably widened to include hospital pharmacists. This move was widely recognized and appreciated by the healthcare community at the time as pharmacists were better placed to report and counter the adverse reactions caused by a rampant increase in the use of nonprescription medicines as well as complementary medicines.9 Further, in 1999, community pharmacists were added into the system, and since then, a substantial increase has been witnessed in the proportion of ADRs being reported. Since 2003, the scheme was amended to include nurses and coroners, following which a pilot scheme was implemented which persuaded patients and guardians to directly report ADRs to the MHRA through the Yellow Card scheme. The insight gained through this pilot project encouraged the MHRA to develop the scheme on a nationwide basis, which was rolled out in February 2008.

Figure 1.

Timelines in the history of Yellow Card scheme.

Through the years, the emergence of information technology has had a significant impact on the Yellow Card scheme. When initiated in 1964, the system was entirely paper-based. Over the years, the authorities realized that paper forms do not make the most convenient and accessible method for reporting ADRs. As a result, the MHRA launched the Yellow Card scheme website in 2002 which provided the reporting population with access to the electronic Yellow Card reporting form. This website has been updated by the MHRA on a regular basis to keep up with advances in technology. In 2008, the website was redeveloped and launched, coinciding with the launch of the Patient Reporting scheme.10

PMS in the UK: features and aspects

Spontaneous reporting of ADRs is an integral mechanism of PV, and the Yellow Card scheme in the UK fulfils this requirement. Yellow Card reports can be submitted directly to the MHRA via post, telephone or the internet. The essential reason to establish spontaneous reporting schemes is to detect adverse reactions to new drugs as well as established drugs, as clinical trials cannot define rare but important ADRs. Although clinical trials are funded by large sums of money running into millions, companies usually fail to detect rare ADRs, as drugs will be administered to a relatively smaller population base of 2,500 volunteers, out of which only about a 100 or so will have taken the drug for a duration lasting more than 1 year.11 Therefore, it is prudent that the MHRA functions efficiently in operating the Yellow Card scheme in order to discern previously known ADRs and convey information about the same to the healthcare community.

The following are the features of the Yellow Card scheme employed by the MHRA in the UK.

Reporting an ADR12

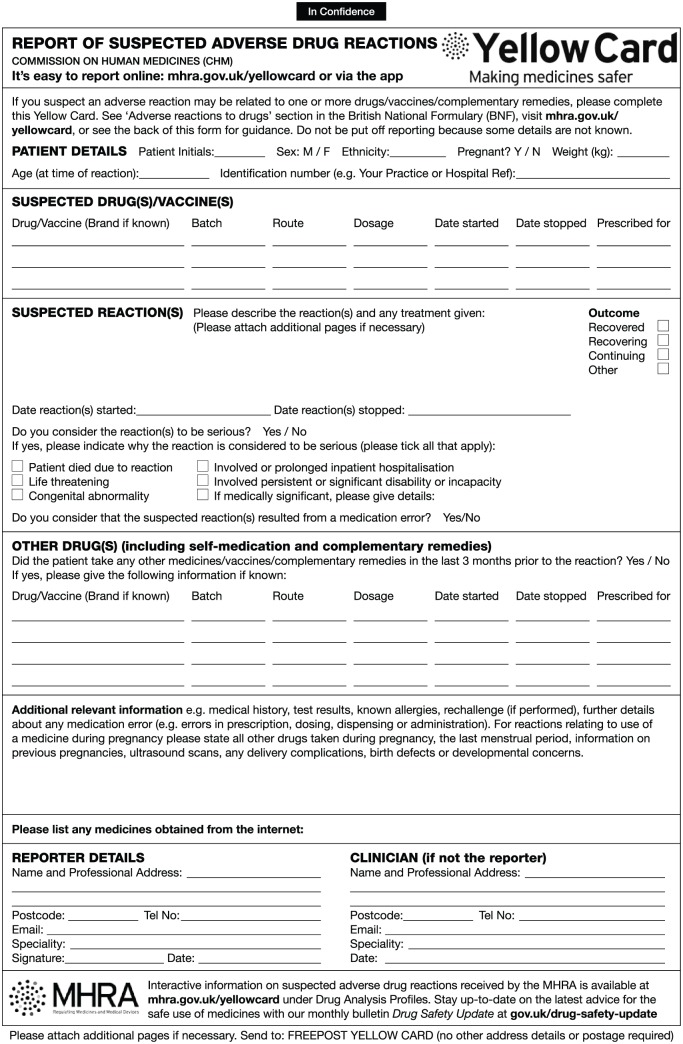

A sample of the Yellow Card ADR reporting form is shown in Figure 2. In the event that a patient suffers from a suspected ADR, the ADR should be reported using a Yellow Card. All ADRs associated with prescription as well as non-prescription drugs should be reported. The MHRA and the CHM do not specify the need for causality to report an ADR. On the contrary, patients and healthcare professionals are encouraged to submit reports, even in the event of doubt with regards to the ADR having occurred. Some instances where reporting a suspected ADR is considered mandatory are described below.

Figure 2.

Yellow Card side-effect reporting form.

➢ Black triangle drugs:13

In the UK, newly introduced pharmaceutical products including biologicals, are labelled with an inverted black triangle when they are first marketed. This black triangle indicates that all suspected ADRs occurring with respect to the marked drug product needs to be brought to the notice of the authorities, regardless of the severity of the adverse reaction. This intensive monitoring of the drug continues for a minimum of 2 years from the launch of the product and can be extended further if necessitated. In addition, a black triangle can be indicated on any medication that requires extensive monitoring. This can be observed in the case of a proven product being marketed as a combination product with another market-proven API.

➢ Serious reactions:

In the event of serious suspected reactions taking place, it is recommended that they are reported through the Yellow Card scheme, irrespective of whether the pharmaceutical product belongs to the category of a black triangle product or not. Such reactions can include fatal and life-threatening reactions, disabling or incapacitating reactions, congenital abnormalities and also medically significant reactions.

The reporting of such ADRs is highly encouraged as increasingly specific advice on side-effects which are likely to occur and corresponding comprehensive data obtained can be employed to compare the safety standards of drug products belonging to the same therapeutic class.

When a Yellow Card is intended to be submitted to the agency, it should include all possible information of the drug that is responsible for the adverse reaction and also document the characteristics of the reaction that occurred. Apart from this, essential information with regard to the patient and information of the healthcare professional should also be provided. The age, sex and weight of the patient should be included, as well as the patient’s initials and a number to identify the patient to the reporter, known as the local identification number.14 While submitting the report, it is not prudent for the reporter to inform the patient; however, the MHRA advises the reporter to inform the patient of the report and also to keep a copy of the Yellow Card on the patient’s chart.

Once a Yellow Card is completed, it is forwarded to the MHRA. Alternatively, the Yellow Card can also be provided to any of the five regional monitoring centres, who forward it to the MHRA. Upon successful acceptance of the report, an acknowledgement is provided to the reporter containing a UIN (unique identification number). Further, the UIN will be affixed to the Yellow Card and all patient-identifying information, except the contact information of the reporter is removed by the MHRA. The report is then entered into the MHRA database to enable rapid analysis of the ADR report. The reporter can be contacted by the MHRA at any point of this entire operation, to provide further data or to provide clarifications about the adverse reaction observed.

The scientists and concerned officials at the MHRA will use data provided on the Yellow Card to check for signs of suspected drug safety issues. These signs are then used to develop the overall ADR profile of the drug product, where alternatives to the drug can be used to carry out a comparison on the probable benefits, both on the basis of indication and efficacy. The CHM and the Pharmacovigilance Expert Advisory Group advise the MHRA on drug safety issues, and based on this advice, a decision will be taken on whether the drug should be withdrawn from the market or whether any changes are necessitated in the use of the drug.8

Communication: healthcare professionals and patients

The MHRA realizes that frequent communication with professionals from the healthcare sector as well as the general population is crucial in ensuring that awareness is created about the prevalence of new ADRs and also to impart valuable feedback. The MHRA achieves this in the following ways:

➢ An independent review carried out on the Yellow Card scheme in 2004 suggested possible ideas that can be implemented to further streamline the system that included the introduction of drug analysis prints (DAPs). A DAP provides information on the reactions reported for all drugs and this database can be accessed from the MHRA database.15

➢ Updating patient information leaflets and summaries of product characteristics for drug products when new safety concerns are identified. Also, the MHRA publishes safety concerns regarding drug products on its website.

➢ Doctors and other healthcare professionals are immediately informed of any urgent drug hazard warnings. The MHRA publishes a monthly bulletin Drug Safety Update that provides the latest advice to enable safer use of medicines. At the same time, the CHM publishes Current Problems in Pharmacovigilance, a drug safety bulletin which is circulated among all doctors as well as professionals from the pharmaceutical field, a copy of which is also provided on the MHRA website.16

➢ The MHRA uses the Public Health Link, which is an electronic cascade system, to propagate urgent information about ADRs to all concerned individuals, particularly from the healthcare sector. This system helps disseminate information when sufficient time is not available to do the same through hard copies.

Minimizing the risk: a regulatory perspective17

When warranted, the MHRA may adopt approaches that will ensure that a drug can be used in a way to minimize its risks, thereby delivering optimum benefits to patients. These approaches are as follows:

➢ Changes to warnings provided on product packaging and labels.

➢ The regulatory authorities will restrict the indications for the use of a drug.

➢ In certain instances, if the use of a drug is deemed to be subject to adverse reactions or is considered to be harmful when taken in higher doses, the regulatory authorities will change the legal status of the drug, for example, an over-the-counter medicine to a prescription medicine.

➢ In rare situations, if the MHRA deems that the adverse effects associated with the use of a marketed product are far too severe compared with the relative benefits, then it will take the decision to withdraw the product from the market.

Safety assessment marketed medicines

The launch of the Safety Assessment Marketed Medicines (SAMM) guidelines in 1994 was an attempt at providing post-approval safety assessment studies of greater scientific credibility. The SAMM guidelines were formalized by a working group containing the MHRA (formerly known as the Medicines Control Agency), Committee on Safety of Medicines, the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry, the British Medical Association (BMA) and the Royal College of General Practitioners. These guidelines were also made available in other European countries including Germany and the Netherlands in order to create an easier passage for the conduct of multinational multicentre studies. This enabled researchers to incorporate thousands of patients in the clinical studies and safety surveillance. In the UK, an SAMM study is ‘a formal investigation conducted for the purpose of assessing clinical safety of marketed medicines in clinical practice.’ This definition of SAMM guidelines encompasses all studies sponsored by the marketing company that are aimed at evaluating the safety of marketed medicinal products. These studies are designed on an objective-based approach but can include observational cohort studies, case-by-case surveillance and clinical trials. The highlights of the guidance were as follows:18

(1) Study patients should be selected from a pool that is representative of the general population of users.

(2) The comparator groups (i.e. patients with similar parameters but on an alternate drug therapy) should ideally be included.

(3) For a patient to be incorporated in a study, the drug should have been prescribed under normal clinical practice circumstances. The subsequent recruitment of the patient into the study shall be as per the study protocol.

For all studies the general advice is also clear:

(1) The draft study plan shall be discussed by the companies with the MCA (now MHRA) prior to submitting a finalized plan.

(2) An adequate ethics committee approval is mandatory.

(3) The company is held responsible for ensuring the conduct of the study as per the approved study protocol under the supervision of a UK-registered medical practitioner.

(4) In the instance that an appointed agent conducts the study on behalf of the company, the agent will be held responsible for the conduct of the study as per the protocol and should liaise with the company.

(5) The entire study should be overseen by an independent advisory board.

(6) Studies should not be instituted with the any ill intent, such as a promotional exercise.

(7) The study payment to doctors should be in accordance with BMA guidelines.

PMS in Canada

Drug approvals in Canada are based on the presentation of substantive documentation of a drug’s quality and safety, by the manufacturer to the regulatory authority, Health Canada. The conduct of clinical trials is subject to the submission of a clinical trial application. After this, Health Canada can authorize the manufacturer to conduct developmental phase clinical trials, involving drugs where the suggested trial is outside the parameters of the marketing authorization of the drug.19 If the drug manufacturer is able to provide substantial evidence of the fulfilment of all applicable requirements, Health Canada will grant an no objection certificate and a drug identification number that authorizes the manufacturer to sell the drug in the pharmaceutical market.

In accordance with the Good Pharmacovigilance Practices guidelines, drug manufacturers have a binding obligation to monitor the safety and efficacy of their medicines post-approval.20 Section C.01.016 to C.01.019 of the guidelines21 strictly forbid a drug manufacturer from engaging in the active sale of a drug unless all necessary information regarding any serious unexpected adverse effect has been reported to Health Canada within 15 days of the occurrence. According to Health Canada, a serious unexpected adverse reaction is “a noxious and unintended response to a drug which may occur at any dose and which will require the hospitalization of the patient or prolonging of existing hospitalization, causes malformation, results in persistent or significant disability or is fatal and life-threatening in nature”.22 Hence, Health Canada employs a three-pronged approach to assure decreased incidences of serious unexpected adverse reactions of marketed drugs, (i.e. collection, analysing and assessment of ADR data submitted by the pharmaceutical industry, healthcare professionals and patients). The Canada Vigilance Program is Health Canada’s PMS program that is entrusted with the responsibility to collect and assess reports of ADRs of health products marketed and sold in Canada. As is the case in most regulated pharmaceutical markets, Health Canada uses the data obtained to conduct a complete analysis of probable safety concerns, recommend pharmaceutical manufacturers to change product labels, and work with manufacturers to enact these changes, communicate new safety information to healthcare professionals and the public.23 The Canada Vigilance Program, initiated in 1965, operates on the basis of adverse reaction reports submitted by healthcare professionals and consumers. The reports can be submitted on a voluntary basis, either directly to Health Canada or to the market authorization holders. This program applies to a wide range of products including prescription and nonprescription medicines, natural health products, biologicals and radiopharmaceuticals. At the regional level, the program is ably supported by the presence of seven Canada Vigilance Regional Offices, who act as the point of contacts for ADR reporters. These regional offices collect reports and forward these to the Canada Vigilance National Office for further assessment.24 In addition to the Canada Vigilance Program, Health Canada formed the Drug Safety and Effectiveness Network (DSEN) as a reaction to the introduction of the Food and Consumer Action Plan. The DSEN, in joint collaboration with the Canadian Institute for Health Research, initiated the Canadian Network for Observational Drug Effect Studies (CNODES) in 2011. CNODES built a network comprising researchers and databases from across Canada with the aim of coordinating drug safety and efficacy-based research for drugs marketed in Canada. A key aspect of CNODES was its access to the UK’s Clinical Practice Research Datalink, as it enabled CNODES to analyse drugs marketed in the UK before they were approved in Canada.25 CNODES was preceded by the Vaccine and Immunization Surveillance in Ontario (VISION), which was operated by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences. However, this program was intended to primarily function as a vaccine vigilance setup.26

Current postmarketing surveillance system

In 2002, Health Canada formed the Marketed Health Products Directorate, which was a part of the broader Canada Vigilance Program, with a specific decree for PMS. The Marketed Health Products Directorate (MHPD), operating under the aegis of the Health Products and Food Branch (HPFR), monitors the activities associated with the assessment of safety trends and risk communication regarding marketed drug products. The MHPD is involved in the development of regulations concerned with reporting of adverse reactions. For this, it coordinates with international organizations which enhances the ease with which information and data can be shared across different regions.27 The core responsibilities of the MHPD are as follows:

➢ collection and monitoring of ADRs and drug incident data.

➢ review and analysis of health product safety information.

➢ conduct a risk–benefit analysis of approved healthcare products.

➢ communicate drug-related risks to healthcare professionals.

➢ develop and implement policies to efficiently regulate healthcare products.

➢ monitor the regulatory advertising schemes.

In 2005, the Canada Vigilance Program was renamed MedEffect Canada. MedEffect Canada acted as a comprehensive tool that ensured improved access to ADR information. Initially, MedEffect Canada was established as a partnership initiative between professional healthcare organizations and consumer groups. It was envisioned as a 5-year pilot project to ensure that access to safe and effective healthcare products was available to all.28 The MedEffect program was introduced by the MHPD with the following goals:

➢ To enable centralized access to reliable and accurate drug product safety data as and when they are made available.

➢ To put in place a simple and efficient system for healthcare professionals and other ADR reporters to file ADR reports via phone, email or mail.

➢ To generate awareness about the necessity of reporting ADRs to Health Canada.

➢ To help identify and communicate potential risks.

A key aspect of the MedEffect program is the Adverse Reaction Online database, where data for ADRs for all health products are readily available including drugs, biologics, prescription and nonprescription drugs and natural health products.

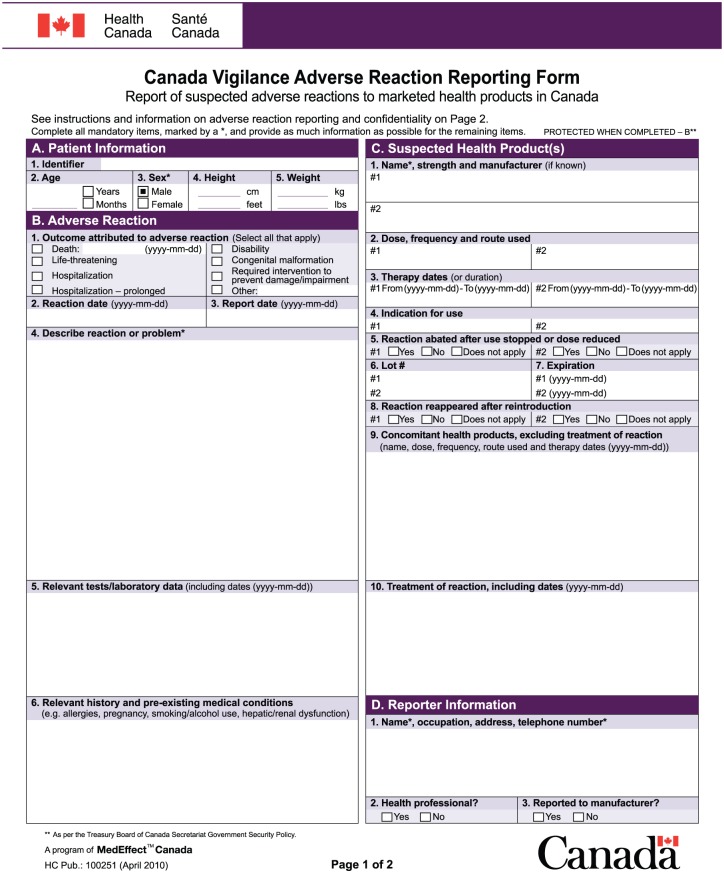

Reporting requirements

A sample of the adverse reaction reporting form is given in Figure 3. The Canadian ADR reporting program includes healthcare professionals as well as consumers as recognized reporters and thereby lets them report ADRs directly to Health Canada and marketing authorization holders. In this manner, PV can be observed efficiently as manufacturers are furnished with sufficient time to understand the ADRs and report them to Health Canada within the stipulated duration of 15 days. Health Canada stipulates that the reporter of an ADR must mandatorily include specific information in the form while submitting the report. Patient information must be filled in that includes the physical features of the patient such as height, weight and age. The patient name is not included in the form for reasons of confidentiality. The form must also provide a description of the reaction experienced by the patient along with the therapy dates, (i.e. the date the ADR occurred/resolved and the date the drug therapy commenced/stopped). Lastly, Health Canada requires the reporter to include contact information of the patient as well as the reporter, in case Health Canada requires any additional information with regard to the adverse reaction.29 In some cases, relevant tests/lab data, as well as concomitant health product data, may be provided.

Figure 3.

The adverse reaction reporting form.

Data assessment and management

Health Canada makes use of MedDRA terminology for coding ADR reports that are submitted as a part of the Canada Vigilance Program. It has introduced the technology to facilitate the electronic transfer of adverse reaction data efficiently, between the marketing authorization holder and the regulatory authorities. This entire setup has been implemented keeping in mind International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) directives and standards. An electronic gateway has been introduced for the benefit of large industrial companies, whereas small and medium-scale manufacturers can operate the system by means of a web-based portal. Once the reports are collected, the reports are assessed for integrity and completeness, then forwarded for further processing. It is the responsibility of the marketing authorization holders (MAHs) to collect follow-up data via telephone calls, site visits, and written requests. During the assessment, the identity of the reporter and the patient is kept confidential as per the provisions of the Privacy Act.30

The reports submitted to Health Canada are assessed by employing the WHO-defined causality categories, thereby determining the causal relationship. Signals from the vigilance database are discerned through a systematic and periodic review of ADR reports, by employing appropriate statistical tools. The MHPD staff assesses and reviews adverse reaction reports, either individually or as a summary of collective reports. As per the Canadian Vigilance System, the process of providing personalized feedback to reporters on the association of drugs and ADRs does not exist. The reporters are instead provided with receipt of adverse reaction reports along with links to electronic monthly bulletins published by Health Canada and MHPD.31

Risk minimization

Health Canada has implemented a number of initiatives to ensure that the rate of incidence of ADRs is kept at a minimum.32

➢ Health Canada has always laid emphasis on educating healthcare professionals and patients/consumers with regards to pharmacovigilance. The availability of suitable tools on the MedEffect Canada website has helped realize this goal to a certain extent.

➢ In addition, Health Canada organizes various outreach programs for healthcare professional groups nationally. These programs are aimed at imparting ADR reporting information for all pharmaceutical products.

➢ Over the years, Health Canada has developed various bilateral international agreements with several foreign agencies. This has enabled the continuous flow of data on ADRs across the world, thereby permitting Health Canada to monitor all international safety concerns.

➢ In Canada, pharmaceutical manufacturers are required to submit periodic safety update reports as well as risk management plans at predefined intervals to Health Canada, thereby providing evidence of the continued safety of the drug product.

Risk communication

➢ Health Canada publishes a monthly adverse reaction bulletin/newsletter, Health Product InfoWatch, that it distributes among healthcare professionals including physicians and pharmacists. This newsletter provides clinically relevant safety information on pharmaceutical products including biologics, medical devices and natural health products.33 It also posts risk communications such as warnings, recalls, advisories and foreign product alerts on the MedEffect website. This website is regularly updated, to provide valuable information on health products to Canadians.

➢ Another initiative undertaken by Health Canada is the Dear Healthcare Professionals (DHP) letters initiative. A DHP letter is a correspondence usually in the form of emails, posts or fax, sent from the regulatory authority or the MAH of a pharmaceutical product. These letters are intended for healthcare professionals and contain important new safety information. These letters provide recipients with information concerning action(s) or practices that have been suggested to reduce particular risks of ADRs associated with a pharmaceutical product.34

Conclusion

PMS and PV are based on the core principle that patient health and patient safety are critical factors to be considered when manufacturing and marketing pharmaceutical products. Hence, while PV in a broader sense focuses on adverse reaction reporting along with disseminating knowledge among the healthcare community and patients in order to minimize risks, PMS fulfils the post-approval requirements of assessing and monitoring the potential risks associated with the use of pharmaceutical products in a larger patient population. In addition to potential risks, hitherto unknown adverse reactions can also be recognized during the PMS of drugs. In the UK, spontaneous reporting of ADRs is an integral mechanism of PMS and PV, and the same is achieved through the presence of the Yellow Card Scheme, operated by the MHRA, which has developed into a robust adverse reaction reporting system over the years. The adverse reaction reports collected through the Yellow Card scheme can be directly submitted to the MHRA via post, telephone or the internet. On the other hand, in Canada, the Canada Vigilance Program (now known as MedEffect), an initiative of Health Canada, is entrusted with the responsibility to collect and assess reports of ADRs of health products marketed and sold in Canada. In 2005, the MedEffect Canada program brought about key changes to the Canada Vigilance Program, keeping in view the needs and goals for patient safety in current times, which crucially included centralized access to reliable and accurate drug product safety data.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the N.G.S.M. Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Nitte (deemed to be University), Mangaluru, Karnataka, India for providing the necessary facilities and financial support to carry out this study. The authors would like to acknowledge the technical support offered by Mr Srivatsa Rao, Senior Manager, Regulatory Sciences, Biocon Limited, Bengaluru, India

Footnotes

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

ORCID iD: Ravi G. S.  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9591-4742

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9591-4742

Contributor Information

Nikhil Raj, Department of Pharmaceutical Regulatory Affairs, N.G.S.M. Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Nitte (Deemed to be University), Deralakatte, Mangaluru, Karnataka, India.

Swapnil Fernandes, Department of Pharmaceutical Regulatory Affairs, N.G.S.M. Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Nitte (Deemed to be University), Deralakatte, Mangaluru, Karnataka, India.

Narayana R. Charyulu, Department of Pharmaceutical Regulatory Affairs, N.G.S.M. Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Nitte (Deemed to be University), Deralakatte, Mangaluru, Karnataka, India

Akhilesh Dubey, Department of Pharmaceutical Regulatory Affairs, N.G.S.M. Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Nitte (Deemed to be University), Deralakatte, Mangaluru, Karnataka, India.

Ravi G. S., Department of Pharmaceutical Regulatory Affairs, N.G.S.M. Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Nitte (Deemed to be University), Deralakatte, Mangaluru 575018, Karnataka, India.

Srinivas Hebbar, Department of Pharmaceutical Regulatory Affairs, N.G.S.M. Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Nitte (Deemed to be University), Deralakatte, Mangaluru, Karnataka, India.

References

- 1. Huang YL, Moon J, Segal JB. A comparison of active adverse event surveillance systems worldwide. Drug Saf 2014; 37: 581–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vlahovic V, Mentzer D. Postmarketing surveillance. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2011; 205: 339–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Edwards IR, Aronson JK. Adverse drug reactions: definitions, diagnosis and management. Lancet Respir Med 2000; 356: 1255–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lunevicius R, Haagsma JA. Incidence and mortality from adverse effects of medical treatment in the UK, 1990–2013: levels, trends, patterns and comparisons. Int J Qual Heal Care 2018; 30: 558–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Adverse Drug Reaction Canada. Working to Prevent Canada’s 4th Leading Cause of Death, https://adrcanada.org/ (2018, accessed 8 June 2019).

- 6. Avery A, Anderson C, Bond C, et al. Evaluation of patient reporting of adverse drug reactions to the UK’s ‘Yellow Card scheme’: literature review, descriptive and qualitative analyses, and questionnaire surveys. Health Technol Assess (Rockv) 2011; 15: 1–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Anderson C, Gifford A, Avery A, et al. Assessing the usability of methods of public reporting of adverse drug reactions to the UK Yellow Card Scheme. Heal Expect 2012; 15: 433–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Metters J. Report of an independent review of access to the yellow card scheme. London: TSO National Audit Office, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marketed Health Products Directorate. Yellow Card Scheme - MHRA, https://yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk/monitoringsafety (accessed 8 June 2019).

- 10. Rabbur RSM, Emmerton L. An introduction to adverse drug reaction reporting systems in different countries. Int J Pharm Pract 2005; 13: 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tomorrow’s Pharmacist. Yellow Card reporting scheme: what to report and where to? Pharm J 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12. BMA Board of Science. Reporting adverse drug reactions: a guide for healthcare professionals. London: British Medical Association, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Black Triangle: Additional Monitoring of Medicines, www.rpharms.com/resources/quick-reference-guides/black-triangle-additional-monitoring-of-medicine (accessed 8 June 2019).

- 14. The Yellow Card Scheme: guidance for healthcare professionals, patients and the public, www.gov.uk/guidance/the-yellow-card-scheme-guidance-for-healthcare-professionals (2015, accessed 8 June 2019).

- 15. Blenkinsopp A, Wilkie P, Wang M, et al. Patient reporting of suspected adverse drug reactions: a review of published literature and international experience. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2007; 63: 148–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Drug Safety Update-GOV.UK, www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update (accessed 8 June 2019).

- 17. Hillman D, Ryder C. Applying for an EU marketing authorisation: a pharmacovigilance perspective. Regulatory Rapporteur 2019; 16: 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gough S. Post-marketing surveillance: a UK/European perspective. Curr Med Res Opin 2005; 21: 565–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. French DD, Margo CE, Campbell RR. Enhancing postmarketing surveillance: continuing challenges. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2015; 80: 615–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Health Products and Food Branch Inspectorate. www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/drug-products/applications-submissions/guidance-documents/clinical-trials/drugs-health-products-inspectorate.html (accessed 8 June 2019).

- 21. Good pharmacovigilance practices. Guidelines (GUI-0102) - Canada.ca, www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/compliance-enforcement/good-manufacturing-practices/guidance-documents/pharmacovigilance-guidelines-0102.html#a41 (accessed 8 June 2019).

- 22. Cheung RY, Goodwin SH. An overview of Canadian and US approaches to drug regulation and responses to postmarket adverse drug reactions. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2013; 7: 313–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Health Canada. Chapter 4 Regulating Pharmaceutical Drugs. 2011 Fall Report of the Auditor General of Canada, www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/parl_oag_201111_04_e_35936.html (2011, accessed 8 June 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 24. Health Canada. Canada Vigilance Program, www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/medeffect-canada/canada-vigilance-program.html (accessed 8 June 2019).

- 25. Health Canada. Health Product Vigilance Framework, www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/migration/hc-sc/dhp-mps/alt_formats/pdf/pubs/medeff/fs-if/2012-hpvf-cvps/dhpvf-ecvps-eng.pdf (2012, accessed 8 June 2019).

- 26. Wilson K, Ducharme R, Hawken S. Association between socioeconomic status and adverse events following immunization at 2, 4, 6 and 12 months. Hum Vaccines Immunother 2013; 9: 1153–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Health Canada. An overview of the Marketed Health Products Directorate, http://publications.gc.ca/site/archivee-archived.html?url=http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2011/sc-hc/H164-2-2008-eng.pdf (2012, accessed 8 June 2019).

- 28. Health Canada. MedEffect Canada, www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/medeffect-canada.html (accessed 8 June 2019).

- 29. Health Canada. Adverse reaction reporting and health product safety information, www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/migration/hc-sc/dhp-mps/alt_formats/pdf/pubs/medeff/fs-if/2011-ar-ei-guide-prof/2011-ar-ei-guide-prof-eng.pdf (2011, accessed 8 June 2019).

- 30. Health Canada. Adverse reaction and medical device problem reporting, www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/medeffect-canada/adverse-reaction-reporting.html (accessed 8 June 2019).

- 31. van Hunsel F, Härmark L, Pal S, et al. Experiences with adverse drug reaction reporting by patients. Drug Saf 2012; 35: 45–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kaur SD. A comparative analysis of post-market surveillance for natural health products (NHPs). MSc Thesis, University of Ottawa, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Health Canada. Health Product InfoWatch, www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/medeffect-canada/health-product-infowatch.html (accessed 8 June 2019).

- 34. Dear Health Care Professional Letter - OPDIVO®, www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/migration/hc-sc/dhp-mps/alt_formats/pdf/prodpharma/notice-avis/conditions/opdivo_dhcpl_lapds_183397-eng.pdf (2016, accessed 8 June 2019).