Abstract

The aim of this systematic scoping review was to identify and analyze indicators that address implementation quality or success in health care services and to deduce recommendations for further indicator development. This review was conducted according to the Joanna Briggs Manual and the PRISMA Statement. CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO were searched. Studies or reviews published between August 2008 and 2018 that reported monitoring of the quality or the implementation success in health care services by using indicators based on continuous variables and proportion-based, ratio-based, standardized ratio–based, or rate-based variables or indices were included. The records were screened by title and abstract, and the full-text articles were also independently double-screened by 3 reviewers for eligibility. In total, 4376 records were identified that resulted in 10 eligible studies, including 67 implementation indicators. There was heterogeneity regarding the theoretical backgrounds, designs, objectives, settings, and implementation indicators among the publications. None of the indicators addressed the implementation outcomes of appropriateness or sustainability. Service implementation efficiency was identified as an additional outcome. Achieving consensus in framing implementation outcomes and indicators will be a new challenge in health services research. Considering the new debates regarding health care complexity, the further development of indicators based on complementary qualitative and quantitative approaches is needed.

Keywords: implementation, quality, indicators, implementation success, outcomes

What do we already know about this topic?

While measuring implementation success, it is important to differentiate among service, client, and implementation outcomes. Several studies report the need for valid measures.

How does your research contribute to the field?

This systematic scoping review shows a need to develop valid indicators to measure implementation success. In this context, both health care complexity and pragmatism should be considered.

What are your research’s implications toward theory, practice, or policy?

A new generation of complementary qualitative and quantitative indicators may be suitable to meet the challenges of health care complexity.

Introduction

Substantial resources are invested in the health care system to improve the quality of care.1,2 However, evidence-based innovations in health care do not necessarily achieve their desired effects if they are affected by poor implementation quality.3 Therefore, it is important to differentiate between innovation and implementation effectiveness to measure implementation success.4 Innovation and implementation effectiveness can be measured in research settings or in a daily routine setting.5

“Innovation effectiveness describes the benefits [that] an organization receives [because] of its implementation of a given innovation (. . .)”4 and can be measured by service or client outcomes, e.g., efficiency, safety, equity, patient centeredness, and timeliness.5

“Implementation effectiveness refers to the consistency and quality of targeted organization members’ use of a specific innovation”.4 It can be measured by implementation outcomes, e.g., acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, costs, feasibility, fidelity, penetration, and sustainability.5 In the context of the quality implementation framework, the term quality implementation is used and defined as “(. . .) putting an innovation into practice in such a way that it meets the necessary standards to achieve the innovation’s desired outcomes”.6 This definition emphasizes that implementation can be seen as a construct with gradations between low and high quality.6 The definition of implementation quality also emphasizes the importance of a predefined determination of the level of expectations for the implementation outcome.6 The following related terms also exist: implementation strength, which refers to the “(. . .) amount of the program that is delivered”;7 implementation intensity, which refers to the “quantity and depth of implementation activities”;7 implementation quantity, which refers to the “dosage”;7 and implementation degree, which refers to the “degree to which the intervention can be adapted to fit the local context, the strength and quality of the evidence supporting the intervention, the quality of design and packaging and the cost”.7 However, in all the definitions, the implementation outcome measurement is central.

Finally, implementation success comprises both innovation and implementation effectiveness in a setting of the daily routines of health care services, including the measurement of service, client, and implementation outcomes.4,5

The importance of valid implementation measures to evaluate effectiveness due to their intermediate function between service and client outcomes and implementation outcomes is reported in several studies.1,5 Although there are several strategies to integrate evidence-based practices into daily routines to improve health care services’ effectiveness, there is still a need for validated implementation measures.1

Implementation outcomes can be measured by using administrative data and indicators.8,9 Indicators have a long tradition in measuring the quality of health care;10 they measure factors that cannot be directly observed,11 they have a predictive function,12 and their reference range or value indicates good or bad quality.13 An indicator “is a quantitative measure that can be used as a guide to monitor and evaluate the quality of important patient care and support service activities (. . .)”.10 Comparable implementation indicators have a crucial function in implementation monitoring and benchmarking.9 Although there are reviews that address the measurement of implementation outcomes8,14 and another review is planned,15 none of them explicitly focuses on quantitative implementation indicators. Therefore, the aim of this systematic scoping review (SR) was to identify and analyze indicators that address implementation quality or success in health care services and to deduce recommendations for further indicator development.

Methods

A systematic scoping review (SR) was performed according to the approved standards of the “Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers Manual 2015”16 and the “PRISMA Statement”.17

Data Sources and Search Strategy

The databases CINAHL via EBSCO, EMBASE via OVID, MEDLINE via PubMed, and PsycINFO via OVID were searched (see Supplemental Appendix 1). The search strategy was developed according to a predefined SR protocol. The search strategy was pretested by 2 authors (T.W., S.K.) by performing a title-abstract screening of the first 100 records. The search terms were verified according to the PRESS Checklist.18 A two-part search string that combined the search components of implementation and indicator was used. The first string included several terms and synonyms for implementation, e.g., implementation, implementing, implemented, knowledge translation, and dissemination. This was supplemented by the implementation outcomes defined by Proctor et al.,5 e.g., acceptability, implementation costs, and sustainability. The second string included several terms and synonyms of indicator, e.g., indicator, indicators, index, indices and measure, validation, monitoring, and outcome. The search terms were limited to their appearance in the titles of publications to improve precision.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The literature published in English or German between August 2008 and August 2018 was included. Publications were included if they reported monitoring of the quality or success of the implementation of health care interventions or innovations by using quantitative process or outcome indicators or indices. The type of implemented interventions or innovations was not relevant for inclusion or exclusion. However, the identified publications had to be related to health care settings, e.g., inpatient, outpatient, and community health care.

Included publications had to contain indicators that measured continuous variables or proportion-based, rate-based, ratio-based, or standardized ratio–based variables. Indicators that were not explicitly associated with implementation were excluded, for example, performance measures that serve to measure the quality of the provided evidence- and/or consensus-based care and its changes in daily routines.19 These types of measures were only included if they were aimed at and described in the context of implementation measurement.

All types of studies, reviews, and expert reports were included. Letters, editorials, and comments were excluded. Publications that only contained qualitative indicators were excluded.

Literature Selection

The literature selection was conducted and double-checked independently by 3 reviewers (T.W., S.K., B.W.). Duplicates were excluded. First, a title-abstract screening was conducted by categorizing the records (“included,” “excluded,” or “unclear”). For the records that were categorized as “included” and “unclear,” the full text was screened for final eligibility. Backward and forward citation tracking was performed. In cases where there was uncertainty, an uninvolved reviewer was consulted.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

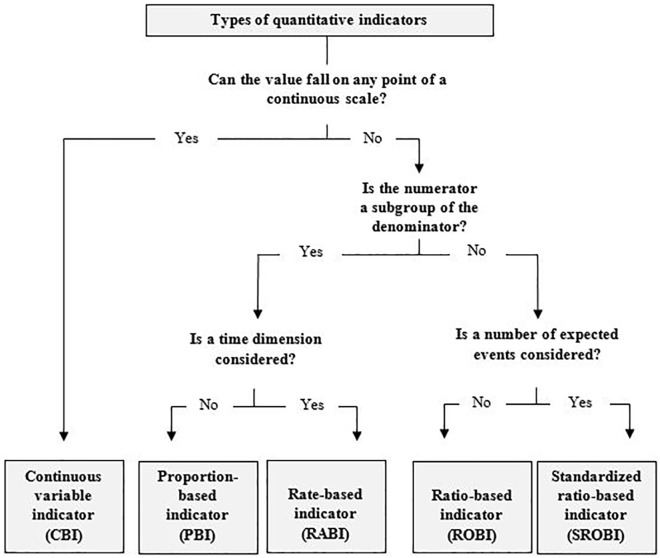

Relevant core data such as the author, publication year, study design, methods, setting, objective, and results were extracted and tabulated according to the Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ guideline.16 The Cochrane guideline20 was also considered for the narrative presentation of the results. A content analysis and data synthesis was performed by combining a deductive and inductive analysis process.21 The coding of the literature was performed by 2 authors (T.W., S.K.). The indicators were categorized as a continuous variable, proportion, rate, ratio, or standardized ratio (see Figure 1). Continuous variable indicators (CBIs) are based on aggregate data whereby the measured value can be represented by any point on a continuous scale,13 e.g., the indicator session exposure, which “(. . .) represents the average number of (. . .) sessions that [an] organization delivered”.1

Figure 1.

Types of quantitative indicators.

Proportion-based indicators (PBIs) measure the frequency of an event (numerator) in a defined population (denominator),22 e.g., “(. . .) the number of providers who deliver a given service or treatment, divided by the total number of providers trained in or expected to deliver the service”.5

Rate-based indicators (RABIs) are expressed by proportions or rates within a given time period. Both the numerator and denominator must contain the population at risk or defined event(s). Additionally, the period of time in which the deviation might occur has to be considered,12 e.g., “[Health Surveillance Assistants] supervised at village clinic in [Integrated Community Case Management] in the last 3 months [divided by] [s]urveyed [Health Surveillance Assistants] working in [Integrated Community Case Management] at the time of assessment”.9

Ratio-based indicators (ROBIs) measure different endpoints in the numerator and denominator,22 e.g., the number of patients who request the implemented service compared to the number of patients who are being offered the service.23

Standardized ratio–based indicators (SROBIs) play a special role among the indicators based on discrete variables.24 They were measured by the number of events that occurred compared to the expected number of events, e.g., the penetration rate, which is calculated as the “Number of eligible patients who use the service [divided by the] number of potential patients eligible for the service”.23

Indices contain several indicators that measure one phenomenon of interest.11

To apply deductive coding, a coding guide was used that considered the implementation outcomes of Proctor et al.5 Additional categories, e.g., implementation quality or success, were developed inductively. By clustering21 and the tabulation of the key results, the differences and commonalities among the identified indicators were identified. In the case of uncertainty regarding the identification of indicators as implementation indicators, the corresponding authors of the publications were contacted, e.g., Karim et al.25 and Garcia-Cardenas et al.23

Quality Appraisal of the Indicators

The quality of the indicators was checked by the following criteria based on “Measure Evaluation Criteria and Guidance for Evaluation Measures for Endorsement” of the National Quality Forum (NQF):26 (1) importance to measure and report refers to the “Extent to which the specific measure focus is (. . .) important to making significant gains in healthcare quality where there is variation in or overall less-than-optimal performance”;26 (2) scientific acceptability of measure properties refers to the availability of psychometric data, especially reliability and validity; (3) feasibility refers to the “Extent to which the specifications, including measure logic, require data that are readily available or could be captured without undue burden and can be implemented for performance measurement”;26 (4) usability refers to the “Extent to which potential audiences (. . .) are using or could use performance results for both accountability and performance improvement to achieve the goal of high-quality, efficient healthcare for individuals or populations”;26 and (5) related and competing measures refers to “(. . .) endorsed or new related measures (. . .) or competing measures (. . .), the measures are compared to address harmonization and/or selection of the best measure”.26

Each criterion was rated yes if the authors of the included papers provided comprehensive information about the quality of the indicator (set) or explicitly stated that the criterion, e.g., validity, was met. Yes* was assigned if the quality criterion was only mentioned briefly or was applicable to individual indicators. No was assigned if the given information suggested that the indicator (set) did not meet the criterion. Not mentioned was assigned if there was no information in relation to the criterion.

Results

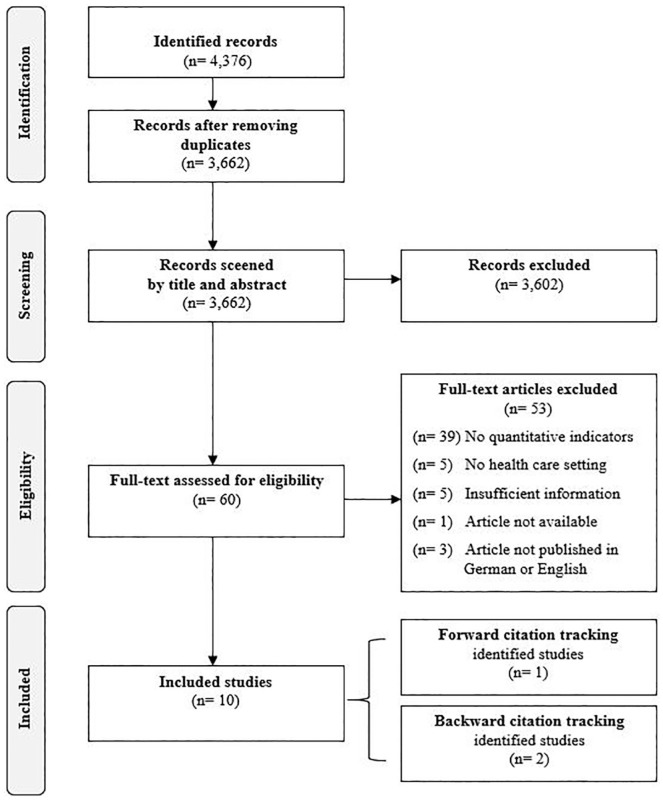

In total, 4376 records were identified that resulted in 10 eligible studies,1,5,9,23,25,27-31 including 67 implementation indicators. Of these studies, the publication of Karim et al.25 was identified by backward citation tracking of Hargreaves et al.32 Both publications of Stiles et al.30 and Garcia-Cardenas et al.23 were identified by backward and forward citation tracking of Proctor et al.,5 respectively (see Figure 2). More than half of the studies, 6 out of 10, were published in the last 5 years. The most common reason for excluding publications during the title-abstract screening was missing quantitative indicators in the context of implementation.

Figure 2.

Prisma flowchart.

There were 2 mixed method studies, one based on a case report and effectiveness implementation hybrid design23 and the other based on a narrative review and consensus-based approach27 (see Table 1). Seven quantitative studies1,9,25,28-31 that consisted of a follow-up study,1 cross-sectional studies,9,25 secondary data analyses,28 (randomized) implementation trials,29,31 and an exploratory study30 were included. One review that provided recommendations for implementation indicators was also included.5

Table 1.

Overview of the Identified Publications.

| Author(s) | Design/Methods | Setting | Objective | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original studies | ||||

| Garcia-Cardenas et al.23 | Mixed method design/case reporta (effectiveness-implementation hybrid design)a | Community health care (Community pharmacy) | Measuring the implementation process of a medication review according to its initial outcomes. | Measurement of the implementation outcomes as a systematic way of approaching the implementation process. |

| Garner et al.1 | Quantitative design/follow-up study (multilevel data set analyses)a | Stationary health care (Substance abuse treatment organizations) | Development of evidence-based measures for evaluating the implementation of the Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach. | Two measures each for fidelity and penetration were developed. The measure for procedure exposure showed high correlation with client outcomes. None of the 3 other indicators were predictive of improvements in client outcomes. |

| Guenther et al.27 | Mixed method design/review, consensus-based approach | Community health care (Global, country level) | Developing a Kangaroo Mother Care measurement framework and a core list of indicators. | Ten core indicators for Kangaroo Mother Care were identified: service readiness (n = 4) and service delivery (n = 6). |

| Heidkamp et al.9 | Quantitative design/cross-sectional study with cell phone interviews | Community health care (Community case management) | Measuring the implementation of Integrated Community Case Managements (childhood illness) by implementation strength and utilization indicators. | There was wide variation in the implementation strength indicators within and across districts. Project progress was shown. |

| Karim et al.25 | Quantitative design/cross-sectional study (dose-response study)a | Community health care (District level) | Reporting the effects of the newborn survival interventions (National Health Extension Program) between 2008 and 2010 in 101 districts of Ethiopia. | The results indicated that Ethiopia’s Health Extension Program has improved maternal and newborn health care practices. The median program intensity score increased 2.4-fold. |

| McCullagh et al.28 | Quantitative design/secondary data analysis of an RCTa | Primary health care (Urban practices) |

Determination of the adoption rates of clinical decision support tools. | Usage of the tool declined over time. A rigorous rationale could not be stated, and further investigation is recommended. |

| Saldana et al.29 | Quantitative design/large-scale randomized implementation triala | Community health care (Child welfare, juvenile justice, mental health, etc.) | Investigation of the behavior in early implementation stages regarding the prediction of a successful Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care program start. Measuring the predictive validity of the “Stages of Implementation Completion.” | Performing the Stages of Implementation Completion in a complete and timely manner increases the likelihood of a successful implementation. |

| Stiles et al.30 | Quantitative design/exploratory study | Community health care (Public mental health care) | Discussion of the conceptualization and operationalization of service penetration and presenting an exploratory study of service penetration. | Measuring data from the same individuals by 2 different collection methods showed different results. A list of criteria for the reporting of service penetration rates is provided. |

| Weir and McCarthy31 | Quantitative design/implementation triala (implementation monitoring process-based information theory) | Stationary health care (Veterans’ health administration, etc.) | Development of a framework to monitor the implementation process by using the example of a computerized provider order entry. | Based on the information model, implementation safety indicators were developed. Monitoring the implementation process by using the indicators helped to track trends in the usage of computerized provider order entry and policy mandates. |

| Reviews | ||||

| Proctor et al.5 | Narrative review | Community/mental health care | Conceptualization of the implementation outcomes in addition to service and client outcomes. | Definition of 8 implementation outcomes: acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, costs, feasibility, fidelity, penetration and sustainability and suggestions for their measurement. |

Described by the authors of the publications.

There was high heterogeneity regarding the objectives and settings of the publications. Six publications reported indicator (framework) development, conceptualizations, and/or indicator validation.1,5,27,29-31 The other 4 publications reported the evaluation of implementation by implementation indicators.9,23,25,28

Seven of the publications addressed community health care settings5,9,23,25,27,29,30 including mental health care,5,29,30 2 publications addressed the stationary health care setting,1,31 and 1 publication addressed the primary health care setting.28

Implementation Indicators

In total, 67 indicators were identified (see Table 2). The development of 41 indicators out of 5 studies1,5,23,29,31 was based on a theoretical background or framework. Three of the publications1,5,23 were based on the conceptual model of Proctor et al.,5 and 1 referred to the Stages of Implementation Completion (SIC) introduced by Chamberlain and colleagues to identify a timeframe for implementation activities and the proportions of completed activities.29 Furthermore, the theoretical framework of information theory presented by Shannon and Weaver was used to develop indicators.31

Table 2.

Indicator Description.

| Author | Endpoints | Indicator type | Indicator denomination/description | Indicator definition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative studies | |||||

| Garcia-Cardenas et al.23 |

Acceptability° (“The

perception among implementation stakeholders (patients and

GP) that the MRF service is agreeable, palatable, or satisfactory”) |

PBI | “Acceptability rate of patient-targeted care plans” | Numerator: No. of “recommendation[s] given by the pharmacist to the patient to prevent and/or solve a negative outcome associated with a medication” that were accepted | Denominator: The total number of recommendations given by the pharmacist to the patients |

| PBI | “Acceptability rate of GPs-targeted care plans” | Numerator: No. of “recommendation[s] given by the pharmacist to the GP to prevent and/or solve a negative outcome associated with a medication during multidisciplinary collaboration” that were accepted | Denominator: The total number of recommendations given by the pharmacist to the GPs | ||

| Feasibility° (“The extent to which the MRF service can be successfully used or carried out within the pharmacy”) | CBI | “Patient recruitment rate” | No. of patients recruited | ||

| PBI | “Retention-participation rate” | Numerator: No. of patients who received the service. | Denominator: No. of patients recruited | ||

| ROBI | “Service-offering rate” | Numerator: “Service offering by the pharmacy” | Denominator: “service request by the patient ratio” | ||

| Fidelity° (“The degree to which the MRF service is implemented and provided as it was described”) | CBI | “Dose: The amount, frequency and duration of MRF service provision” | “Number of patient’s visits to the pharmacy for service provision and time per patient spent on service provision” | ||

| Implementation costs° (“Cost impact of the MRF implementation effort”) | CBI | “Implementation costs” | “Direct measures of implementation costs, including the cost of the service provider and resources needed for service provision” | ||

| Penetration° (“Level of integration of the MRF service within the pharmacy and its subsystems”) | SROBI | “Penetration rate” | Numerator: “Number of eligible patients who use the service” | Denominator: “[N]umber of potential patients eligible for the service” | |

| Service implementation efficiency§ (“The degree to which the service provider improves his/her skills and abilities to provide it”) | CBI | “Service implementation efficiency” | “Change in the time spent on the service provision through the implementation program” | ||

| Garner et al.1 | Fidelity ° | CBI | “Session exposure” | “average number of A-CRA sessions that the organization delivered to its respective adolescent client” | |

| ROBI | “Procedure exposure” | “average number of unique A-CRA procedures that the organization delivered to its respective adolescent client” | |||

| Penetration ° | CBI | “Client penetration” | “unduplicated number of adolescent clients that the organization delivered at least one A-CRA procedure over the course of their SAMHSA/CSAT project” | ||

| CBI | “Staff penetration” | “total number of ‘staff A-CRA certification days’” | |||

| Guenther et al.27 | Penetration * | PBI | “KMC service availability: Percentage of facilities with in-patient maternity services with operational KMC” | Numerator: “Number of health facilities in which KMC is operational*” | Denominator: “Number of health facilities with inpatient maternity services” |

| Adoption * | PBI | “Weighed at birth: Percentage of newborns weighed at birth” | Numerator: “Number of newborns weighed at birth” | Denominator: “Number of live births” | |

| PBI | “Identification of newborns ≤2000 g: Percentage of live births identified as ≤2000 g” | Numerator: “Number of newborns identified as ≤2000 g” | Denominator: “Number of live births” | ||

| SROBI | “KMC coverage‡: Percentage of newborns initiated on facility–based KMC” | Numerator: “Number of newborns initiated on facility-based KMC” | Denominator: “Expected number of live births OR expected number of LBW babies” | ||

| PBI | “KMC monitoring: Percentage of KMC newborns who are monitored by health facility staff according to protocol” | Numerator: “Number of newborns admitted to KMC who are monitored by health facility staff according to protocol (includes at minimum: assessing feeding, STS duration, weight, temperature, breathing, heart rate, urine/stools)” | Denominator: “Number of newborns initiated on facility-based KMC” | ||

| PBI | “Status at discharge from KMC facility: Percentage of newborns discharged from KMC facility who: met facility criteria for weight gain/health status; left against medical advice; referred out; or died before discharge” | Numerator: “Number of newborns discharged from facility–based KMC who: 1) met facility criteria for weigh gain, health status, feeding, thermal regulation, family competency, etc.; 2) left against medical advice; 3) referred out for higher level care; 4) died before discharge” | Denominator: “Number of newborns discharged from facility-based KMC” | ||

| Fidelity * | PBI | “KMC follow-up: Percentage of newborns discharged from facility-based KMC that received follow-up per protocol” | Numerator: “Number of newborns discharged from facility-based KMC that received follow-up per protocol” | Denominator: “Number of newborns discharged alive who received facility-based KMC” | |

| Heidkamp et al.9 | Penetration * | ROBI | “HSA-to-population ratio” | Numerator: “HSAs working at time of assessment (Data source: MOH district records)” | Denominator: “Total population under 5 years (Data source: NSO Census 2008 - 2013 Projection)” |

| PBI | “Proportion of HSAs trained in iCCM” | Numerator: “HSAs trained in iCCM” | Denominator: “HSAs working at time of assessment (MOH district records)” | ||

| PBI | “Proportion of hard-to-reach areas with iCCM-trained HS” | Numerator: “HSAs trained in iCCM who work in HTRA (Data not available)” | Denominator: “Total no. of HTRA (Data not available)” | ||

| RABI | “Proportion of iCCM HSAs who have seen a sick child in the past 7 days” | Numerator: “HSAs who have seen a sick child in the past 7 days” | Denominator: “Surveyed HSAs working in iCCM at the time of the assessment” | ||

| PBI | “Proportion of iCCM HSAs who are living in their catchment area” | Numerator: “HSAs who live in their catchment area” | Denominator: “Surveyed HSAs working in iCCM at the time of the assessment” | ||

| Fidelity * | RABI | “Proportion of iCCM HSAs with supply of key iCCM drugs in last 3 months” | Numerator: “HSAs with no stockouts of more than 7 days of cotrimoxizole, lumefantrine-artemether, ORS, and/or zinc in the last 3 months (HSA must have at least one dose of unexpired drug at the time of survey)” | Denominator: “Surveyed HSAs working in iCCM at the time of the assessment” | |

| RABI | “Proportion of iCCM HSAs with supply of life-saving CCM [sic] drugs in the last 3 months” | Numerator: “HSAs with no stockouts of any duration of three life-saving drugs (cotrimoxizole, lumefantrine-artemether, and ORS) in the last 3 months (HSA must have at least one dose of unexpired drug at the time of survey)” | Denominator: “Surveyed HSAs working in iCCM at the time of the assessment” | ||

| Penetration * | ROBI | “Utilization” | “Mean no. of sick children seen per iCCM-trained HSA in the last 1 month” | ||

| Adoption * | RABI | “Proportion of iCCM HSAs supervised at village clinic in the last 3 months” | Numerator: “HSAs supervised at village clinic in CCM [sic] in the last 3 months” | Denominator: “Surveyed HSAs working in iCCM at the time of the assessment” | |

| RABI | “Proportion of iCCM HSAs supervised in the last 3 months with reinforcement of clinical practice” | Numerator: “HSAs supervised at village clinic with observation of case management or practicing case scenarios or mentored in health facility in the last 3 months” | Denominator: “Surveyed HSAs working in iCCM at the time of the assessment” | ||

| Karim et al.25 |

Penetration

*

(“Program intensity”) |

RABI | “period prevalence of household visits by HEWs” | “the percentage of women in a kebele who were visited by a HEW during six months preceding the survey” | |

| RABI | “period prevalence of household visits by CHPs” | “the percentage of women in a kebele who were visited by a CHP during the last six months” | |||

| PBI | “proportion of households with a FHC” | Not mentioned | |||

| PBI | “proportion of model families” | “percentage of respondents who reported that their household was a model family household or they were working towards it” | |||

| McCullagh et al.28 |

Acceptability

§

Unclear |

ROBI | “iCPR tool use” | Numerator: “opened tool” | Denominator: “iCPR encounters” |

| Unclear | “iCPR tool completion” | – | |||

| Unclear | “iCPR smartset completion” | – | |||

| Saldana et al.29 | Feasibility * | ROBI | “Duration score” | “the amount of time that a county/agency takes in a stage is calculated by dates of entry through date of final activity completed” | |

| Fidelity * | PBI | “Proportion score” | “the proportion of activities completed within a stage” | ||

| Stiles et al.30 | Penetration ^ | RABI | “Penetration rate” “within a specified time frame” | Numerator: “the number of eligible persons who used the service(s)” | Denominator: “the total number of eligible persons” |

| RABI | “Annual penetration” | Numerator: “Total persons having any service contact during the year” | Denominator: “Total persons eligible at some point during the year” | ||

| RABI | “Average monthly penetration” | Numerator: “Total user months over a 1-year period” | Denominator: “Total eligible months over a 1-year period” | ||

| Weir and McCarthy31 | Adoption * | PBI | Not mentioned | “Proportion of orders entered by each clinical role (M.D., R.N., R.N. verbal, pharmacist, clerk)” | |

| PBI | “Proportion of orders entered by R.N.s” | “# of R.N., verbal, and telephone orders/total # of orders” | |||

| Fidelity * | PBI | “Mean time for unsigned orders” | “# of orders left unsigned after 6 hours/total # of orders” | ||

| CBI | Not mentioned | “# of orders incorrectly entered as text orders” | |||

| PBI | “Proportion of antibiotic orders expiring w/out a DC order” | “# of antibiotic orders expiring w/out a DC order/total # of antibiotic orders” | |||

| Penetration * | PBI | “Origin of order (direct entry, order set, or personal order set)” | “# of each type/total # of orders” | ||

| Fidelity * | PBI | “Proportion of orders with entry error” | “# of orders DC’ed by each service and reentered (e.g., lab, pharmacy)/ total # of orders per service” | ||

| CBI | Not mentioned | “# of orders incorrectly entered as text orders” | |||

| Unclear | CBI | Not mentioned | “# of automatically generated co-orders (e.g., corollary, expired, transfer, etc.)” | ||

| Feasibility * | CBI | Not mentioned | “Time for each service between orders and event (e.g., lab collection, imaging procedure done)” | ||

| CBI | Not mentioned | “# of times unplanned computer down per week” | |||

| CBI | Not mentioned | “# of DC’ed orders by clerk with ‘duplicate’ as reason” | |||

| Fidelity * | CBI | Not mentioned | “# of missing print lab and pharmacy labels” | ||

| CBI | Not mentioned | “# of alerts unresolved after 12 hours (indicating possible delivery to wrong clinician)” | |||

| Feasibility * | CBI | Not mentioned | “Time from order of stat meds to actual delivery” | ||

| CBI | Not mentioned | “# of incident reports for errors” | |||

| Fidelity * | CBI | Not mentioned | “# of duplicate ‘sticks’ for the same lab order” | ||

| CBI | Not mentioned | “# of hours that alerts for out-of-range lab values remain unsolved” | |||

| CBI | Not mentioned | “# of hours that out-of-range lab values remain out of range, e.g., potassium, haematocrit” | |||

| ROBI | Not mentioned | “Average time for X-ray readings to be available” | |||

| ROBI | Not mentioned | “Average time for orders to be acknowledged by R.N.” | |||

| CBI | Not mentioned | “# of hours between the two signers for chemo-therapy orders” | |||

| CBI | Not mentioned | “# of minutes postop orders are activated after transfer to floor” | |||

| CBI | Not mentioned | “# of minutes between activation of admission orders and official bed assignment” | |||

| Proctor et al.5 | Penetration | PBI | Not provided | “the number of providers who deliver a given service or treatment, divided by the total number of providers trained in or expected to deliver the service” | |

Note. GP = general practitioners; MRF = pharmacist-led medication review with follow-up; PBI = proportion-based indicator; CBI = continuous variable indicator; ROBI = ratio-based indicator; SROBI = standardized ratio–based indicator; RABI = rate-based indictors; A-CRA = Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach; SAMHSA = Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; CSAT = Center for Substance Abuse Treatment; KMC = Kangaroo Mother Care; LBW = low birth weight; STS = skin-to-skin; HSA = Health Surveillance Assistant; MOH = Ministry of Health; NSO = National Statistical Office; iCCM = Integrated Community Case Management; HTRA = hard-to-reach areas; ORS = oral rehydration solution; HEW = Health Extension Workers; CHPs = Community Health Promoters; FHC = Family Health Card; iCPR = integrated clinical prediction rule; M.D.= physician; R.N. = registered nurse; DC = discontinue.

Indicators categorized by outcomes consistent with Proctor et al.5 by the authors of the identified publications.

Indicators categorized by described outcomes of the authors of the identified publications.

Indicators categorized by outcomes described by the authors of this article consistent with Proctor et al.5

Indicators categorized by Proctor et al.5 according to their defined outcomes.

The distribution regarding the indicator types and the indicators that address implementation outcomes was not balanced. There was high heterogeneity regarding the objectives of the indicators. The indicators were based either on a continuous variable (n = 23)1,23,31 or on a discrete variable (n = 42),1,5,9,23,25,27-30 and some (n = 2) could not be categorized because the data provided were poor.28 There were only 2 standardized ratio-based indicators, namely, the penetration rate, i.e., the “Number of eligible patients who use the service [divided by the] number of potential patients eligible for the service”,23 and Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC) coverage, i.e., the “Percentage of newborns initiated on facility-based KMC”.27 Most of the indicators were provided by Weir and McCarthy (n = 24).31

Nearly all implementation indicators could be assigned to implementation outcomes (acceptability, adoption, costs, feasibility, fidelity, and penetration) according to the conceptional model of Proctor et al.5 None of the indicators were assigned to appropriateness or sustainability. However, Garcia-Gardenas et al.23 addressed the implementation outcome appropriateness by three qualitative indicators, e.g., “(. . .) the perceived fit of the innovation to address the drug-related problems of the local community”.23 These indicators did not meet our inclusion criteria. Garcia-Cardenas et al.23 and Garner et al.1 did the matching themselves to the model of Proctor et al.,5 and one additional outcome, service implementation efficiency, was described and measured by “[t]he degree to which the service provider improves his/her skills and abilities to provide it”.23 The indicators of Stiles et al.30 were directly assigned by Proctor et al.5; the indicators of McCullagh et al.28 were assigned by the authors themselves without considering Proctor et al.5

Interestingly, fidelity (n = 22)9,23,27,31 and penetration were most frequently addressed by indicators (n = 19).1,9,23,25,27,30,31 In contrast, implementation cost23 and service implementation efficiency31 were addressed by only 1 indicator each. Furthermore, acceptability (n = 3),23,28 adoption (n = 9),9,27,31 and feasibility (n = 9)23,29,31 were poorly addressed by the indicators throughout the studies.

All indicators monitored a defined population, e.g., patients, health care providers, or the intervention itself. The indicators included service delivery, service use or activity completion as an endpoint, each from a defined perspective on the outcome, e.g., fidelity and penetration are measured by service delivery.1,9,23,25,27,29-31 On the one hand, service delivery, considering the outcome fidelity, is measured by a predefined standard. On the other hand, service delivery, considering the outcome penetration, is measured by the provision of the service in an area or between areas.1,9,23,25,27,29-31 In contrast, the implementation of the safety indicators31 that addressed fidelity and feasibility were focused on inefficient service provision or activities, e.g., “[number] of incident reports for errors”31 or “[number] of orders incorrectly entered as text orders”.31 Nearly all identified indicators are process indicators.

Outcomes Addressed by the Indicators

Garcia-Cardenas et al.23 aimed to describe the implementation process of a medication review and evaluation of its initial outcomes in a community pharmacy; they measured/analyzed acceptability (n = 2) on the 2 levels of patient acceptability and health care provider acceptability (general practitioners).23 Feasibility (n = 3) was measured by several rates, such as recruitment rates, the retention of participation rates, and service offering rates. Fidelity (n = 1) was measured by the quantity, frequency, and duration of service provision. Implementation costs (n = 1) were measured regarding service provision cost and resources, and penetration (n = 1) was measured by the level of organizational integration.23 Service implementation efficiency (n = 1) was operationalized by the degree of service provision skill improvement and measured by the needed service provision time.23

Garner et al.1 aimed to develop evidence-based measures to evaluate the implementation of the Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach in stationary health care in substance abuse treatment organizations. They also aimed to examine the relationship between implementation and client outcomes. Fidelity (n = 2) and penetration (n = 2) were measured by session and procedure delivery.1 Penetration was additionally measured by staff certification days.1

Guenther et al.27 aimed to develop a standardized approach to measure the implementation and progress of KMC by using a measurement framework and a core list of indicators that facilitate the monitoring of penetration. Adoption (n = 5) was measured by the number of newborns who were weighed, identified, initially assessed, discharged from or admitted to KMC.27 Fidelity (n = 1) was measured by the number of newborns who were discharged and received follow-up per the protocol; penetration (n = 1) was measured by KMC service availability.27

Heidkamp et al.9 aimed to measure the implementation of Integrated Community Case Management (iCCM) (childhood illness) by implementation strength and utilization indicators. Adoption (n = 2) was measured by Health Surveillance Assistants (HSAs) who were supervised at the clinic regarding iCCM. Fidelity (n = 2) was measured by HSAs with no stockouts during a predefined period. Penetration (n = 6) was measured according to the distribution of the HSAs and by the utilization of the iCCMs: HSAs that were working or trained in iCCM or by the number of children seen by an iCCM-trained HSA.9

Karim et al.25 aimed to report the effects of the implementation, labeled program intensity, of a newborn survival intervention in 101 districts of Ethiopia. Penetration (n = 4) as the core outcome was measured by the period prevalence of visits of households and by the proportion of households that were a model family household or that had a family health card.25

McCullagh et al.28 aimed to determine the adoption rates of clinical decision support tools. Acceptability as defined by McCullagh et al.28 was described as the use of the integrated clinical prediction rule (iCPR) (n = 1). Two other measures from the iCPR tool or smartest completion could not be categorized because of poor contextual information for the indicators. However, the outcome adoption is conceivable.28

Saldana et al. aimed to investigate behavior in the early implementation stages regarding the prediction of a successful start of the Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care program and to measure the predictive validity of the first 3 “Stages of Implementation Completion”.29 In this context, fidelity (n = 1) was measured by completed activities, and feasibility (n = 1) was indicated by the total time spent in the individual stage to complete the activities.29

Stiles et al.30 aimed to explore, conceptualize, and operationalize the indicators of service penetration. Penetration (n = 3) was measured by service use and service contact, including an overall measure of penetration that considered different time frames.30

Weir and McCarthy31 aimed to develop an implementation process monitoring framework by using the example of a computerized provider order entry (CPOE) that considered implementation safety indicators. Adoption (n = 2) was measured by entered orders. Fidelity (n = 15) was measured by unsigned, incorrect or discontinued orders, by unsolved problems regarding CPOE, and by the time that is needed for a predefined CPOE activity. Feasibility (n = 5) was measured by unplanned, unexpected, discontinued, and inefficient activities and penetration (n = 1) was measured according to the origin of the order. The categorization of automatically generated co-orders was unclear.31

Proctor et al.5 aimed to conceptualize implementation outcomes in addition to service and client outcomes. They recommended that indicator penetration (n = 1) could be measured by the service or treatment delivery by trained providers.5

Quality of the Implementation Indicators

Only the indicators in 2 publications9,25 met 5 of the 6 quality criteria of the NQF (see Table 3). Only these publications described at least one of their indicator as scientifically acceptable.9,25,29 One publication reported related and competing measures or reference values.27

Table 3.

Quality of the Implementation Indicators.

| Author | Importance to measure and report | Scientific acceptability | Feasibility | Usability and use | Related and competing measures | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reliability | Validity | |||||

| Original studies | ||||||

| Garcia-Cardenas et al.23 | Yes | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Yes* | Yes* | Not mentioned |

| Garner et al.1 | Yes | Not mentioned | No | Yes* | Yes* | Not mentioned |

| Guenther et al.27 | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes* |

| Heidkamp et al.9 | Yes | Yes* | Yes* | Yes | Yes* | Not mentioned |

| Karim et al.25 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes* | Yes | Not mentioned |

| McCullagh et al.28 | Yes | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Yes* | Yes* | Not mentioned |

| Saldana et al.29 | Yes | Not mentioned | Yes* | Yes* | Yes* | Not mentioned |

| Stiles et al.30 | Yes* | No | No | Yes* | No | No |

| Weir and McCarthy31 | Yes | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Yes* | Yes* | Yes |

| Reviews | ||||||

| Proctor et al.5 | Yes | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Yes* | Not mentioned | Yes |

Note. Yes = the authors provided comprehensive information about the quality of the indicator (set) or explicitly stated that the criterion was met; Yes* = the quality criterion was only mentioned briefly in the publication or it was only applicable to individual indicators; No = the given information suggested that the indicator (set) did not meet the criterion; Not mentioned = there was no information in relation to the criterion.

Discussion

Although a comprehensive SR was performed, only a small number of publications and implementation indicators were identified. Several challenges of indicator-based implementation measurement and the need for new types of validated indicators were deduced.

We showed that several terms, frameworks, and models do exist for implementation measurement. This is problematic for both scientists and practitioners to identify implementation measures.33 Some authors1,23 applied the terminology introduced by Procter et al.5 Additionally, the term implementation strength was used.9 Schellenberg et al.7 also introduced the term implementation strength and added the terms implementation intensity, degree, and quality. Other authors discussed the term implementation quality.6,34 Rabin et al.35 addressed this problem by establishing a web-based, collaborative platform to stimulate an organized exchange among scientists, physicians, and other stakeholders to evaluate and standardize the constructs and measurement tools for implementation processes.

Several authors14,36,37 have already applied or discussed the Conceptional Framework for Implementation Research of Proctor et al.5 Throughout the last few years, they have all concluded that there is still a need for the development of an implementation framework including its related measures.14,36,37 The Context and Implementation of Complex Interventions (CICI) framework is recommended as a determinant and evaluation framework that considers the factors that influence implementation outcomes. It allows the assessment of implementation success by considering the context and setting of implementation endpoints.37 In addition to the outcomes of Proctor et al.,5 it is suggested by Pfadenhauer et al.37 that outcome dissemination should be added to the framework. Furthermore, service implementation efficiency is provided.23 However, a recent discussion describes implementation outcomes in light of health care and health care services research complexity in contrast to pragmatism.38 A redefinition of implementation success is postulated in addition to a discussion of the suitability of predetermined outcomes and process fidelity in the context of a complementary holistic view, where outcomes are emergent and measured by mixed method approaches to allow flexibility in a changing research context.38 The identified indicators were often related to a defined context and defined processes. Not all outcomes were addressed by indicators.

It would be of interest to develop indicators that are suitable for several implementation purposes. It is argued to consider several dimensions of implementation quality, e.g., process and outcome, for implementation measurement.6 Along these lines, the question also arises regarding how can existing measures stand up to the new debate on health care complexity and pragmatism?38 Two of the identified studies represented a first attempt by emphasizing the need for both qualitative and quantitative indicators or describe a qualitative view on selected indicators.23,27 A combination of complementary qualitative, and quantitative indicators can be assumed.38

We show that the publication of validated implementation indicators is lacking. Additionally, Garner et al.1 state that the availability of a validated implementation indicators is limited. We also show that the implementation indicator references were poorly reported. If calculated reference values or reference ranges based on normative or empirical data are missing, determining experience-based values is suggested.24 In a monitoring setting, a high sensitivity should be the aim.13 In this regard, the present SR seeks to increase awareness of the definitions for the corresponding reference values or ranges and to maintain an awareness of the changes in implementation processes. Continuous monitoring of implementation allows the early identification of deviations and new problems. Additionally, it allows the ongoing evaluation of adaptions in the implementation efforts.6

Finally, we identified interesting indicators of implementation safety.31 These indicators are being developed considering changing systems, including information changes at both the system and individual levels.31 The authors state that these types of indicators are necessary to ensure patient safety.31

Limitations

This SR has considered approved scientific standards. According to Krippendorff,21 an independent content analysis of the literature might minimize the risk of bias. Here, the coding was conducted by just one of the authors (T.W.); further coding and checks were conducted by another author (S.K.). In cases of uncertainty, either another reviewer or the corresponding author of the identified publication was contacted. Due to a significant number of publications that would not meet the inclusion criteria, the search string was restricted to the title. However, this served to increase precision so that the reduction in quantity was acceptable. A publication bias can be assumed, because unpublished or gray literature was excluded. However, we contacted selected authors of the included literature for further unpublished works to be considered. Although an initial assessment of the quality of the indicators was made, no final critical appraisal of the included publications was performed. It should be noted that this is not required for an SR.16

The quality indicator description differed throughout the publications. Therefore, in some cases, it was necessary to assemble indicator components for a structured presentation.

Conclusion

Finding consensus in framing and defining implementation success and outcome measurement by implementation indicators will be a new challenge in health services research; such a consensus would facilitate the development and use of valid implementation indicators in health services research and practice. Therefore, it is essential to consider the new debates in the context of health care complexity and to the need for an efficient and targeted method of measurement. Finally, a new generation of complementary qualitative and quantitative indicators considering several dimensions of implementation quality may be needed to meet the challenges of health care complexity.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, 2019.05.04_Suplementary_Implementation_success_indicators for Implementation Outcomes and Indicators as a New Challenge in Health Services Research: A Systematic Scoping Review by Tabea Willmeroth, Bärbel Wesselborg and Silke Kuske in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The project is funded by the Fliedner Fachhochschule Duesseldorf, University of Applied Sciences.

ORCID iD: Silke Kuske  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2221-4531

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2221-4531

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Garner BR, Hunter SB, Funk RR, Griffin BA, Godley SH. Toward evidence-based measures of implementation: examining the relationship between implementation outcomes and client outcomes. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;67:15-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Grimshaw J, Eccles M, Thomas R, et al. Toward evidence-based quality improvement. Evidence (and its limitations) of the effectiveness of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies 1966-1998. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(suppl 2):S14-S20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: new guidance. https://www.mrc.ac.uk/documents/pdf/complex-interventions-guidance/. Accessed October 8, 2017.

- 4. Klein KJ, Sorra JS. The challenge of innovation implementation. Acad Manage Rev. 1996;21(4):1055-1080. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Meyers DC, Durlak JA, Wandersman A. The quality implementation framework: a synthesis of critical steps in the implementation process. Am J Community Psychol. 2012;50(3-4):462-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schellenberg JA, Bobrova N, Avan BI. Measuring implementation strength: literature review draft report 2012. http://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/1126637/. Published November 1, 2012. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- 8. Cook JM, O’Donnell C, Dinnen S, Coyne JC, Ruzek JI, Schnurr PP. Measurement of a model of implementation for health care: toward a testable theory. Implement Sci. 2012;7:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Heidkamp R, Hazel E, Nsona H, Mleme T, Jamali A, Bryce J. Measuring implementation strength for integrated community case management in Malawi: results from a national cell phone census. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93(4):861-868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO). Characteristics of clinical indicators. Qual Rev Bull. 1989;15(11):330-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burzan N. Indikatoren. In: Baur N, Blasius J, eds. Handbuch Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer; 2014:1029-1036. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mainz J. Defining and classifying clinical indicators for quality improvement. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15(6):523-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sens B, Pietsch B, Fischer B, et al. Begriffe und Konzepte des Qualitätsmanagements. 4. Auflage. https://www.egms.de/static/de/journals/mibe/2018-14/mibe000182.shtml. Accessed May 13, 2019.

- 14. Lewis CC, Fischer S, Weiner BJ, Stanick C, Kim M, Martinez RG. Outcomes for implementation science: an enhanced systematic review of instruments using evidence-based rating criteria. Implement Sci. 2015;10:155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khadjesari Z, Vitoratou S, Sevdalis N, Hull L. Implementation outcome assessment instruments used in physical healthcare settings and their measurement properties: a systematic review protocol. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42017065348. Published 2017. Accessed May 13, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16. The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2015 Edition/Supplement. The Joanna Briggs Institute. Adelaide, Australia; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Braithwaite J, Hibbert P, Blakely B, et al. Health system frameworks and performance indicators in eight countries: a comparative international analysis [published online ahead of print January 4, 2017]. SAGE Open Med. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ryan R, Cochrane Consumers Communication Review Group. Cochrane consumers and communication review group: data synthesis and analysis. http://cccrg.cochrane.org/sites/cccrg.cochrane.org/files/public/uploads/meta-analysis_revised_december_1st_1_2016.pdf. Published December 2016. Accessed May 13, 2019.

- 21. Krippendorff K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Guide for reading Eligible Professional (EP) and Eligible Hospital (EH) emeasures: version 4. https://www.himss.org/guide-reading-eligible-professional-ep-and-eligible-hospital-eh-emeasures. Published May 2013. Accessed June 19, 2019.

- 23. Garcia-Cardenas V, Benrimoj SI, Ocampo CC, Goyenechea E, Martinez-Martinez F, Gastelurrutia MA. Evaluation of the implementation process and outcomes of a professional pharmacy service in a community pharmacy setting. A case report. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2017;13(3):614-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Geraedts M, Drösler SE, Döbler K, et al. DNVF-Memorandum III „Methoden für die Versorgungsforschung“, Teil 3: Methoden der Qualitäts- und Patientensicherheitsforschung. Gesundheitswesen. 2017;79(10):e95-e124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Karim AM, Admassu K, Schellenberg J, et al. Effect of Ethiopia’s health extension program on maternal and newborn health care practices in 101 rural districts: a dose-response study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6):e65160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. National Quality Forum (NQF). Measure evaluation criteria and guidance for evaluating measures for endorsement. http://www.qualityforum.org/Measuring_Performance/Submitting_Standards/2017_Measure_Evaluation_Criteria.aspx. Published 2017. Accessed April 23, 2019.

- 27. Guenther T, Moxon S, Valsangkar B, et al. Consensus-based approach to develop a measurement framework and identify a core set of indicators to track implementation and progress towards effective coverage of facility-based Kangaroo Mother Care [published online ahead of print December 2017]. J Glob Health. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McCullagh L, Mann D, Rosen L, Kannry J, McGinn T. Longitudinal adoption rates of complex decision support tools in primary care. Evid Based Med. 2014;19(6):204-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Saldana L, Chamberlain P, Wang W, Brown HC. Predicting program start-up using the stages of implementation measure. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2012;39(6):419-425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stiles PG, Boothroyd RA, Snyder K, Zong X. Service penetration by persons with severe mental illness: how should it be measured? J Behav Health Serv Res. 2002;29(2):198-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Weir CR, McCarthy CA. Using implementation safety indicators for CPOE implementation. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2009;35(1):21-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hargreaves JR, Goodman C, Davey C, Willey BA, Avan BI, Schellenberg JR. Measuring implementation strength: lessons from the evaluation of public health strategies in low-and middle-income settings. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(7):860-867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rabin BA, Lewis CC, Norton WE, et al. Measurement resources for dissemination and implementation research in health. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Busch C, Werner D. Qualitätssicherung durch evaluation. In: Bamberg E, Ducki A, Metz A-M, eds. Gesundheitsförderung und Gesundheitsmanagement in der Arbeitswelt: Ein Handbuch. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe; 2011:221-234. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rabin BA, Purcell P, Naveed S, et al. Advancing the application, quality and harmonization of implementation science measures. Implement Sci. 2012;7:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chaudoir SR, Dugan AG, Barr CHI. Measuring factors affecting implementation of health innovations: a systematic review of structural, organizational, provider, patient, and innovation level measures. Implement Sci. 2013;8:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pfadenhauer LM, Gerhardus A, Mozygemba K, et al. Making sense of complexity in context and implementation: the Context and Implementation of Complex Interventions (CICI) framework. Implement Sci. 2017;12:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Long KM, McDermott F, Meadows GN. Being pragmatic about healthcare complexity: our experiences applying complexity theory and pragmatism to health services research. BMC Med. 2018;16:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, 2019.05.04_Suplementary_Implementation_success_indicators for Implementation Outcomes and Indicators as a New Challenge in Health Services Research: A Systematic Scoping Review by Tabea Willmeroth, Bärbel Wesselborg and Silke Kuske in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing