Abstract

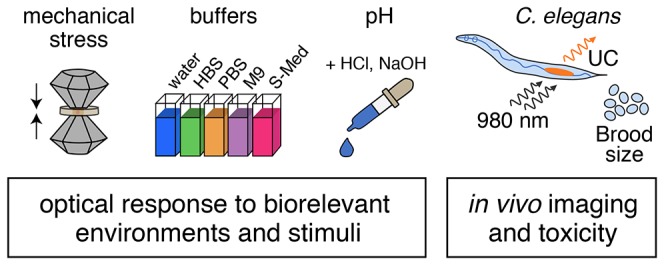

Upconverting nanoparticles (UCNPs) are promising tools for background-free imaging and sensing. However, their usefulness for in vivo applications depends on their biocompatibility, which we define by their optical performance in biological environments and their toxicity in living organisms. For UCNPs with a ratiometric color response to mechanical stress, consistent emission intensity and color are desired for the particles under nonmechanical stimuli. Here, we test the biocompatibility and mechanosensitivity of α-NaYF4:Yb,Er@NaLuF4 nanoparticles. First, we ligand-strip these particles to render them dispersible in aqueous media. Then, we characterize their mechanosensitivity (∼30% in the red-to-green spectral ratio per GPa), which is nearly 3-fold greater than those coated in oleic acid. We next design a suite of ex vivo and in vivo tests to investigate their structural and optical properties under several biorelevant conditions: over time in various buffers types, as a function of pH, and in vivo along the digestive tract of Caenorhabditis elegans worms. Finally, to ensure that the particles do not perturb biological function in C. elegans, we assess the chronic toxicity of nanoparticle ingestion using a reproductive brood assay. In these ways, we determine that mechanosensitive UCNPs are biocompatible, i.e., optically robust and nontoxic, for use as in vivo sensors to study animal digestion.

Short abstract

Biocompatibility tests on ligand-stripped α-NaYF4:Yb,Er@NaLuF4 nanoparticles show high mechanosensitivity, pH stability, and low chronic toxicity for potential in vivo applications in mechanobiology.

As researchers develop new nanotechnologies for biomedical applications, there is a need to evaluate their biocompatibility for effective integration. Inorganic nanoparticles, in particular, offer desirable properties like luminescence, magnetism, high surface-to-volume ratio, and responsiveness to external stimuli for imaging, diagnostics, therapy, drug delivery, and sensing.1−3 Inorganic nanoparticles include metallic,4−7 semiconducting,8 carbon-based (e.g., nanodiamond, carbon nanotubes),9 and rare-earth or lanthanide-based10,11 nanoparticles, each with distinct material properties. However, the attributes that make them useful, such as their small size and material composition, may have unexpected consequences in living organisms, marked by negative changes to the physiology and behavior of the biological specimen.12,13 For example, heavy metal ion-leaching from the host matrix has been especially concerning with uncoated quantum dots,14,15 while the morphology of carbon nanotubes induces asbestosis-like symptoms in mice.16,17 Beyond toxicity, another side of biocompatibility deals with the ways in which the biological environment might alter the nanoparticles, for instance, through degradation and aggregation.12,13,18 It has been shown for a variety of nanoparticles that proteins adsorb onto the surface,19−21 forming a corona that inhibits the particles’ function (e.g., targeting22). Additionally, the preparation of nanoparticles for experiments (e.g., storage23) can introduce factors that alter material properties.

Here, we focus on lanthanide-based upconverting nanoparticles (UCNPs), a class of luminescent nanoparticles that emit in the visible with near-infrared illumination. In addition to enabling background-free imaging, UCNPs exhibit photostability24,25 and synthetic tunability26 that make them suitable as optical probes for a variety of applications. Recent advances include deep brain optogenetics,27 super-resolution imaging,28,29 photodynamic therapy,30 drug delivery,31 and sensing external stimuli.32−35 Of rising interest is the application of upconversion in mechanobiology, a field that studies how mechanical signals regulate biological processes ranging from touch sensation36 to stem cell differentiation.37 In the last year, our group has developed bright, mechanosensitive UCNPs with measurable color responses to mechanical stress,38 promising a new way to visualize and quantify forces in vivo. The color response is a ratiometric change in the red-to-green emission ratio over micro-Newton forces, which are relevant magnitudes exerted by muscle contractions.34,39

To use mechanosensitive UCNPs in biology, key questions about biocompatibility must first be addressed: how do the nanoparticles affect their environment (i.e., toxicity), and how does the environment affect the nanoparticles’ optical performance? Lanthanide-based nanoparticles tend to have low toxicity, as illustrated by many in vitro cell studies11,40−42 and several in vivo studies.43−45 Nanoparticles should be water-soluble and dispersed in biological buffers. However, decreased intensity and changes in emission color have been reported for particles suspended in water compared to organic solvents (e.g., ethanol, dimethylformamide, cyclohexane).46,47 Further, groups have shown evidence of fluoride leaching from the nanoparticle host (NaYF4), resulting in complete emission quenching and the eventual disintegration of particles in water.48,49 Such changes will convolute the optical signal (i.e., intensity and/or color) intended for detecting mechanical forces. Typically, additional surface modifications like ligand-exchange and additive shell layers, such as silica coatings and polymeric shells, can mitigate but do not completely eliminate these surface and solvent effects.42,50−54 For mechanosensitive UCNPs, the addition of materials and ligands with different mechanical properties55 than the ceramic NaLnF4 host may alter the pressures that are recorded, so we investigate the simplest type of surface modification, ligand-stripping. Of course, this decision has implications in other areas: stability in buffers and pH values, robustness in vivo, and toxicity. Therefore, it is important to characterize these sensors with a comprehensive suite of tests to ensure proper readout in more complex, in vivo applications.

In this paper, we aim to address questions about the biocompatibility of upconverting mechanosensors by understanding the effect of biological media on the nanoparticles’ optical properties and the effect of the nanoparticles on living organisms. First, we characterize the mechano-optical response of ∼30 nm ligand-stripped, core–shell UCNPs (α-NaYF4:Yb,Er@NaLuF4) using a diamond anvil cell (DAC). We then monitor how upconversion emission changes over time (up to 23 days) in commonly used buffers, including hydroxyethyl piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES)-buffered saline (HBS), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), M9, and S-Medium. To mimic a dynamic environment, we cycle between pH 6 and pH 3 in S-Medium. For the purposes of characterizing UCNPs for mechanosensing in a dynamic, muscular system like the digestive tract, we focus on toxicity in the context of feeding UCNPs to the model organism, Caenorhabditis elegans. Ultimately, we find that these nanoparticles are highly mechanosensitive, pH-stable, chronically nontoxic by ingestion, and suitable for in vivo imaging and mechanosensing applications.

Results and Discussion

Ligand-Stripped UCNPs for Aqueous Environments

We synthesize nanoparticles consisting of an upconverting cubic-phase NaYF4:Yb(18%),Er(2%) core with an inert 4–5 nm NaLuF4 shell. Lanthanide ions Yb3+ and Er3+ act as the sensitizer and emitter pair; Yb3+ absorbs in the near-infrared (980 nm), and Er3+ emits in the visible, with distinct green (520 nm, 540 nm) and red (660 nm) bands. Recently, we showed that the same core–shell particles are structurally robust stress sensors with a ratiometric color response in the μN force regime.38 However, the nanoparticles were characterized in nonpolar solvents (i.e., cyclohexane and silicone oil). Cells, tissues, and organisms, in contrast, consist mostly of water, a polar solvent. Therefore, translating UCNPs for use in mechanobiology requires surface modifications to suspend them in aqueous media. In doing so, new solvent–surface interactions will alter upconversion processes and emission.54

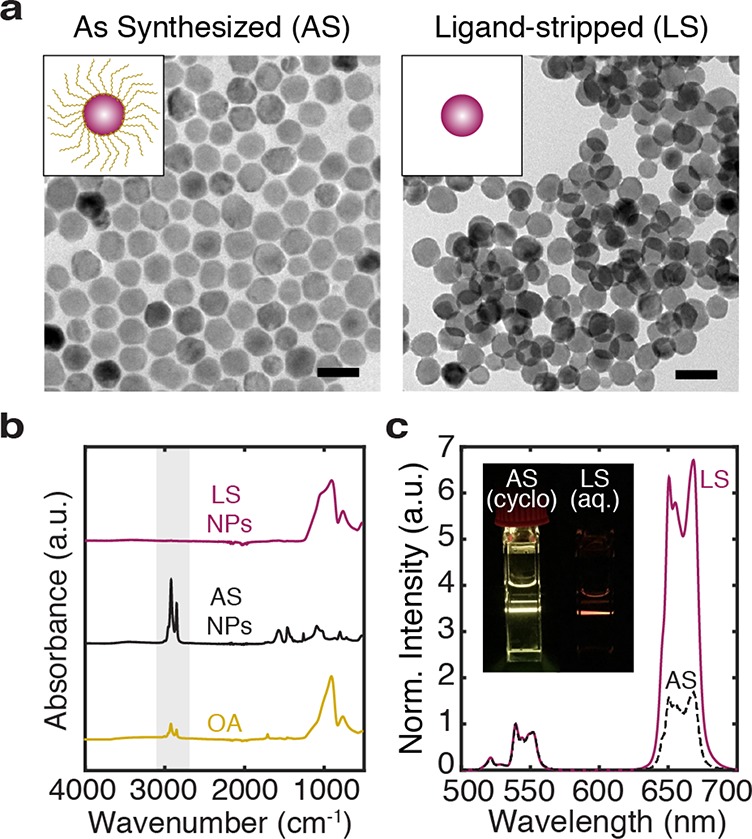

As a first step, we strip the hydrophobic, oleic acid (OA) ligand off of UCNPs using a modified procedure from Bogdan et al.56Figure 1a shows representative transmission electron micrographs (TEMs) of sub-50 nm as synthesized (AS) and ligand-stripped (LS) nanoparticles. OA provides a ∼2 nm barrier on the AS particles surface, which provides more uniform particle dispersion and interparticle distances seen in the TEM of AS nanoparticles compared to LS nanoparticles. To further verify that organics, including OA ligand, were fully removed from the nanoparticles surface, we perform Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). Absorption spectra for OA, AS nanoparticles, and LS nanoparticles are presented in Figure 1b. Peaks near 2900 cm–1 signify the stretching modes of CH2 and CH3;57 they are present in the spectra for OA and AS nanoparticles but not in LS nanoparticles. Instead, the FTIR signature of LS nanoparticles is dominated by a broad peak around 910 cm–1, associated with the glass slide that samples are prepared on. The FTIR spectrum of the glass slide is presented in the Supporting Information (SI).

Figure 1.

Upconverting nanoparticles before and after ligand-stripping. (a) Core–shell (NaYF4:Yb,Er@NaLuF4) nanoparticles are as synthesized (AS) with an oleic acid (OA) coating and ligand-stripped (LS) for dispersion in aqueous media. Transmission electron micrographs (TEMs) show the quasispherical morphology and monodispersity of AS nanoparticles and LS nanoparticles. The scale bars are 50 nm. (b) Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) measurements of OA (gold), AS nanoparticles (black), and LS nanoparticles (maroon) confirm that the highlighted vibrational modes around 2900 cm–1, associated with organic molecules like OA, are no longer present after the ligand-stripping procedure. Here, each spectrum is normalized to its maximum peak. For LS NPs and OA, the dominant peak around 910 cm–1 comes primarily from the glass slide (see Figure S1). (c) Upconversion spectra of AS nanoparticles in cyclohexane (black) and LS nanoparticles in an aqueous medium, S-Medium (maroon). Each spectrum is normalized to its green emission peak. The inset qualitatively shows the corresponding emission of colloidally suspended nanoparticles in a cuvette under 980 nm laser illumination. Enhanced contribution of the red emission band explains the perceived color difference between AS and LS UCNPs.

To monitor the effects of ligand-stripping on optical

properties,

we perform spectroscopy measurements by illuminating colloidally suspended

nanoparticles in a quartz cuvette with a continuous-wave (CW) 980

nm laser. Under similar illumination irradiance (100 W/cm2), distinct differences in emission color and brightness can be seen

between the AS and LS nanoparticles. In the picture inset of Figure 1c, for example, AS

nanoparticles in cyclohexane have brighter emission and appear yellow,

while LS nanoparticles in buffer solution appear red. The color difference

is quantified by the ratio of the Er3+ red and green emission

peaks,  . Figure 1c plots

normalized upconversion spectra, showing the

relative enhancement of red emission for LS nanoparticles in S-Medium

compared to AS nanoparticles in cyclohexane. The corresponding red-to-green

ratio is 9 versus 2. In general, LS nanoparticles dispersed in aqueous

media have redder emission than AS nanoparticles in cyclohexane due

to solvent interactions at the surface.46,47,51,56 More specifically,

OH stretching modes around 3500 cm–1 facilitate

nonradiative transitions in Er3+ that give rise to more

probable pathways of populating the radiative red state.46,47,54 In the SI, we compare the energetics of upconversion with and without OH bonds,

based on models reported in the previous literature.47,54,58,59 Additionally, we verify that the drastic color difference is not

an artifact of power loss caused by water absorption at 980 nm.

. Figure 1c plots

normalized upconversion spectra, showing the

relative enhancement of red emission for LS nanoparticles in S-Medium

compared to AS nanoparticles in cyclohexane. The corresponding red-to-green

ratio is 9 versus 2. In general, LS nanoparticles dispersed in aqueous

media have redder emission than AS nanoparticles in cyclohexane due

to solvent interactions at the surface.46,47,51,56 More specifically,

OH stretching modes around 3500 cm–1 facilitate

nonradiative transitions in Er3+ that give rise to more

probable pathways of populating the radiative red state.46,47,54 In the SI, we compare the energetics of upconversion with and without OH bonds,

based on models reported in the previous literature.47,54,58,59 Additionally, we verify that the drastic color difference is not

an artifact of power loss caused by water absorption at 980 nm.

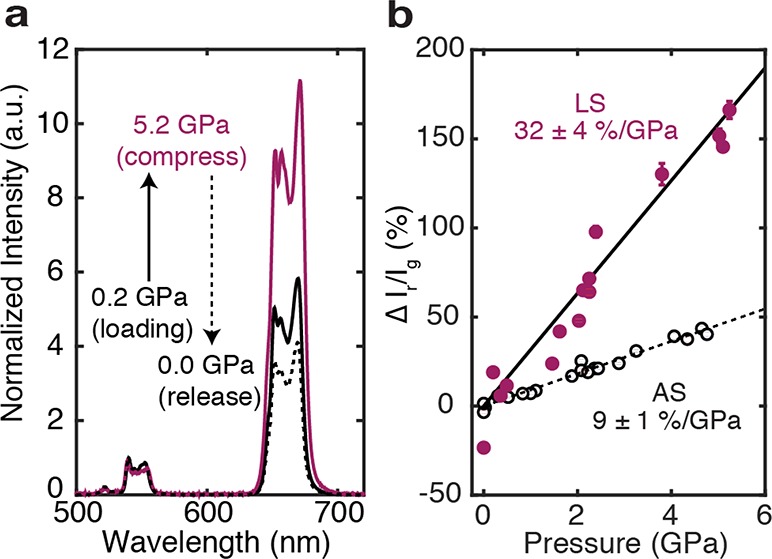

Mechano-optical Response of LS Nanoparticles

We characterize the mechanosensing capabilities of LS core–shell nanoparticles. In our laser-coupled DAC setup (see the Methods section), nanoparticles and a ruby calibrant are loaded in the DAC sample chamber with a hydrostatic pressure medium. Methanol:ethanol (4:1) is chosen as the pressure medium, because it is calibrated with ruby photoluminescence60 and provides a more polar and biorelevant environment than the typical silicone oil. Pressures up to ∼5 GPa are applied for three compression cycles while upconversion spectra are collected. In Figure 2a, we compare upconversion spectra at loading pressure (0.2 GPa), maximum exerted pressure (5.2 GPa), and full release pressure (0.0 GPa). Each spectrum is normalized to its own green emission peak, showing the relative change in red emission with respect to green emission; compression enhances the contribution of red emission, which can then be reversed upon pressure release. Crystal field distortions induced by external stress underlie these changes in optical properties.38,61 In Figure S4, we show that green intensity is more sensitive to pressure than red intensity.

Figure 2.

Mechanosensitivity of

LS nanoparticles. (a) Upconversion spectra

of LS nanoparticles loaded in a DAC with methanol:ethanol (4:1) pressure

medium at 0.2 GPa loading (solid black), 5.2 GPa maximum (solid maroon),

and final release pressure after three cycles (dashed black). Each

spectrum is normalized to its own green emission peak to visualize

the relative enhancement of red emission upon compression. (b) For

three pressure cycles, we record the percent change in the ratio from

the fitted ambient value ( ). An error-weighted

linear fit of all the

data points provides a slope or the mechanosensitivity value. LS nanoparticles

are over 3× more sensitive than AS nanoparticles with oleic acid.

Data for AS UCNPs were previously reported.38 The error on mechanosensitivity is the 95% confidence interval of

the fit. Error bars on markers indicate the standard deviation from

three spectra collected at each pressure point and may lie within

the marker.

). An error-weighted

linear fit of all the

data points provides a slope or the mechanosensitivity value. LS nanoparticles

are over 3× more sensitive than AS nanoparticles with oleic acid.

Data for AS UCNPs were previously reported.38 The error on mechanosensitivity is the 95% confidence interval of

the fit. Error bars on markers indicate the standard deviation from

three spectra collected at each pressure point and may lie within

the marker.

To quantify mechanosensitivity,

we look at the linear response

of the red-to-green ratio to pressure over three cycles. Specifically,

the slope of an error-weighted linear fit for all data points serves

as our figure of merit, defined as the percent change in the red-to-green

ratio ( ) per unit of pressure applied (GPa). Figure 2b displays data over

three pressure cycles with a fitted mechanosensitivity value of 32

± 4%/GPa. Interestingly, we find that LS nanoparticles are over

3 times more sensitive than their as synthesized counterparts with

an OA surface coating. As we have previously characterized, AS nanoparticles

exhibit a mechanosensitivity value of 9 ± 1%/GPa.38 One possible explanation for the observed differences

in mechanosensitivity is the role of OA molecules in dampening the

mechanical stress that particles actually experience. For instance,

OA crystallizes around 0.2–0.4 GPa,62 and the mismatch in elastic modulus to the particles NaYF4 host may influence the transmittance of mechanical stress and lattice

strain. The removal of OA enhances the color response of our nanoparticles,

which benefits force-detection. If other types of shell materials

or ligands are added, the particles should be recalibrated to account

for different mechanical properties. For instance, polymeric nanoparticles

have an elastic modulus <10 GPa,63 while

α-NaYF4 nanoparticles are stiffer with a modulus

of ∼300 GPa.61

) per unit of pressure applied (GPa). Figure 2b displays data over

three pressure cycles with a fitted mechanosensitivity value of 32

± 4%/GPa. Interestingly, we find that LS nanoparticles are over

3 times more sensitive than their as synthesized counterparts with

an OA surface coating. As we have previously characterized, AS nanoparticles

exhibit a mechanosensitivity value of 9 ± 1%/GPa.38 One possible explanation for the observed differences

in mechanosensitivity is the role of OA molecules in dampening the

mechanical stress that particles actually experience. For instance,

OA crystallizes around 0.2–0.4 GPa,62 and the mismatch in elastic modulus to the particles NaYF4 host may influence the transmittance of mechanical stress and lattice

strain. The removal of OA enhances the color response of our nanoparticles,

which benefits force-detection. If other types of shell materials

or ligands are added, the particles should be recalibrated to account

for different mechanical properties. For instance, polymeric nanoparticles

have an elastic modulus <10 GPa,63 while

α-NaYF4 nanoparticles are stiffer with a modulus

of ∼300 GPa.61

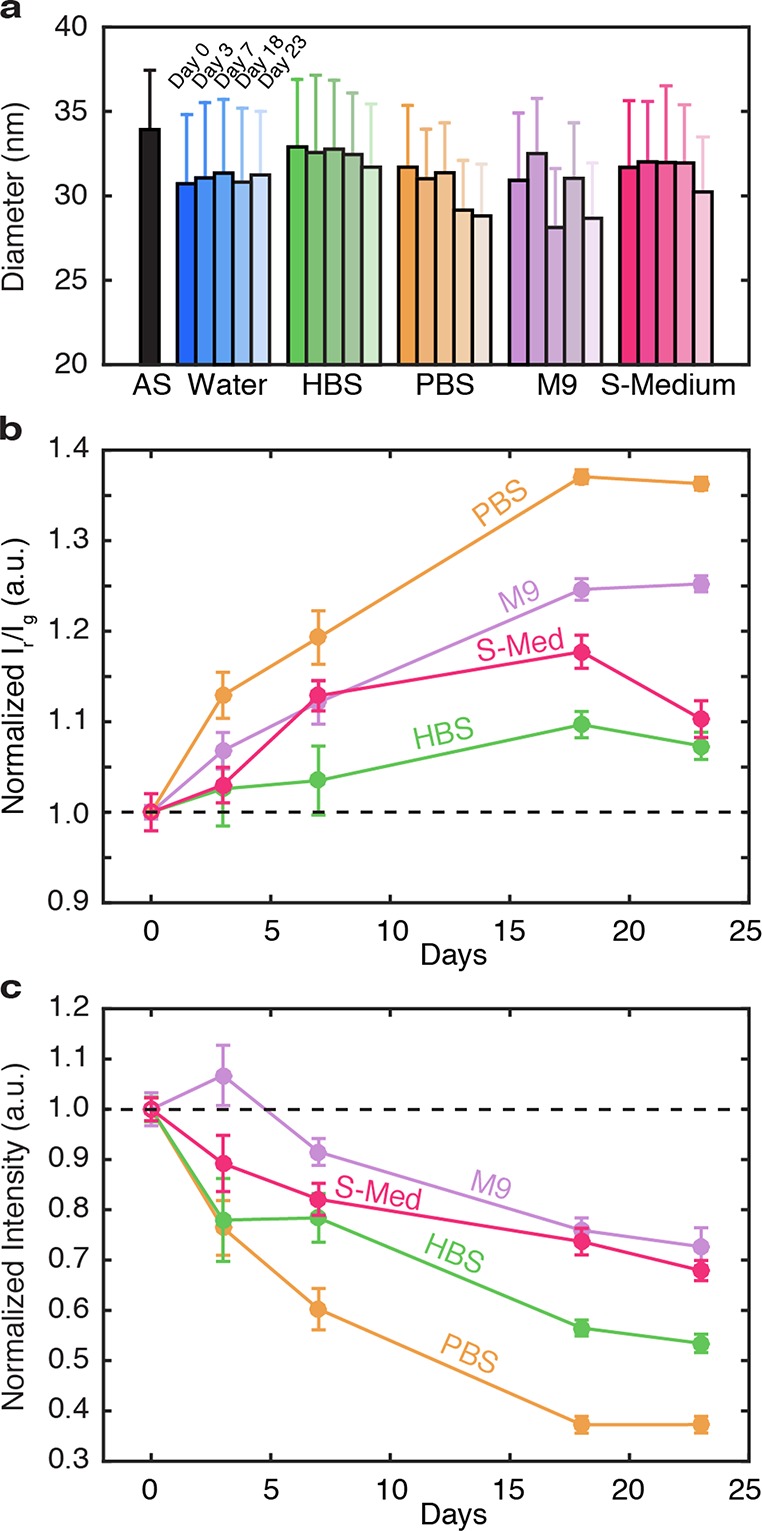

Buffer-Dependence on Optical Stability

Photostability is vital for imaging and sensing probes. Consistent brightness, for example, is required to detect a signal over the course of biological experiments. UCNP-based sensors typically have readouts that rely emission intensity, ratio, or energy transfer to other agents like dyes and fluorophores.32−35 While UCNPs are often touted for their photostability, processes like ion-leaching and degradation have been shown to compromise their optical performance over time.48,49,64 Previously, we characterized how the 4–5 nm inert shell of our core–shell nanoparticles provides effective surface passivation and enhances quantum yield by nearly 20×.38 Here, in various external environments, we expect that the inert shell will help protect the upconverting core. A previous study, for example, showed improved photostability of core–shell nanoparticles compared to cores alone.65 Despite shells up to 10 nm thick, however, particles are still susceptible to solvent effects at the surface.54 Therefore, understanding how the UCNPs change in various buffer types will improve preparation and storage methods, ensuring a more consistent readout in biology experiments.

First, LS nanoparticles are suspended in a variety of aqueous media commonly used with C. elegans, as well as other model organisms and cell lines. The media include water, HBS, PBS, M9, and S-Medium, of which the latter three are phosphate-based buffers. HBS and PBS are tuned to pH 7.4; water and M9 have pH 7, and S-Medium is slightly more acidic at pH 6. To properly compare between media types and their effect on UCNPs, we use and prepare the same batch of nanoparticles across all media.

Optical properties could be affected by structural degradation over time.48,49 Hence, we analyze the size of UCNPs stored in aqueous solution for over 3 weeks. Our particle analysis is done on TEM images containing 100–200 nanoparticles each (see the Methods section). Figure 3a displays how particle diameter has changed across and within buffer types; each bar represents the average size and distribution of particles. Per media type, we collect TEM images at Day 0 (day of ligand-stripping and suspension in buffer), Day 3, Day 7, Day 18, and Day 23. The biggest difference in particle size comes from the initial surface modification and suspension in aqueous media, which can be seen by comparing the colored bars (LS UCNPs) to the black bar (AS UCNPs). AS UCNPs are 33.9 ± 3.5 nm in diameter, while those in aqueous media range from 30.7 ± 4.1 nm (water) to 32.9 ± 4.0 nm (HBS) at Day 0. Interestingly, particle size is fairly constant thereafter and decreases only slightly on the final day of our investigation, suggesting that there is minimal etching of the shell layer with the addition of buffer salts and other ingredients. Only PBS results in a consistent decrease of average particle size. However, the changes are within the standard deviation of size distributions, which come from the particle synthesis and image analysis. In previous work using PBS, nanoparticle size was evaluated using dynamic light scattering (DLS) because the nanoparticles had a polymeric coating. The size of those particles increased over a week’s time due to significant aggregation.66 In this work, we saw significantly more aggregation in PBS and M9 compared to nanoparticles in other buffers (see Figure S5 for the complete TEM series).

Figure 3.

Structural and optical properties in buffers over time. Changes in (a) average nanoparticle diameter, (b) red-to-green emission ratio, and (c) emission intensity are recorded over 3 weeks after nanoparticles are suspended in a variety of aqueous media: water (blue), HBS (green), PBS (orange), M9 (purple), and S-Medium (pink). In part (a), the black bar represents the diameter of as synthesized (AS) nanoparticles prior to ligand-stripping. Error bars represent the standard deviation or size distribution of 100–200 nanoparticles analyzed from TEMs (see the SI). Note that values for (b) ratio and (c) intensity are normalized to Day 0 values for each buffer, while dashed lines indicate ideal photostability or constant emission over time. Nanoparticle concentration (10 mg/mL) and illumination conditions (100 W/cm2) are kept constant throughout the duration of the experiment. Here, error bars represent the standard deviation of three spectra collected at each time point.

The type of buffer influences the nanoparticles’ emission color (Figure 3b) and intensity (Figure 3c) differently over time. For biological experiments, buffers are preferred over water for maintaining pH and sustaining physiological processes, so we compare across the buffers and present data for water in the SI. Importantly, we maintain constant particle concentration (10 mg/mL) and illumination powers (100 W/cm2) throughout the entire experiment. Since each medium has slightly different components and pH values to start with, which will alter absorption and emission properties, we normalize to Day 0 values and track trends with respect to that initial data point. For instance, the red-to-green ratios for Day 0 buffers are 8.4 (HBS), 9.3 (PBS), 8.6 (M9), and 9.3 (S-Medium).

An ideal environment will maintain constant upconversion emission, indicated by the dashed lines in Figure 3b,c. Over 23 days, the red-to-green ratio generally increases, and intensity decreases for all buffers. HBS provides the most constant ratio over 3 weeks, while the phosphate buffers have more pronounced changes. Phosphate adsorbs strongly onto the nanoparticle surface,42,66 which can cause more particle aggregation and loss of luminescence. S-Medium is the best of the phosphate buffers, suggesting that the presence of other ingredients, such as cholesterol and citrate, coat the surface and mitigate the effect of phosphate. We isolate the effect of cholesterol and citrate on emission properties in the SI (Figure S8); cholesterol alone yields a more consistent red-to-green ratio compared to S-Medium or citrate alone. Meanwhile, intensity tends to be more sensitive than color and decreases rapidly in the first week, meaning that nanoparticles are best used as soon as possible after ligand-stripping. Because we use concentrations above saturation (>1 mg/mL) to minimize fluoride leaching,49 we do not observe complete intensity loss even after several weeks. PBS is consistently the most detrimental buffer for upconversion emission, with up to 65% loss in intensity, and should be avoided for biological use without additional surface modification.

By monitoring upconversion emission in a variety of buffers over time, we identify the time frame for which our LS UCNPs can be used as sensors. Optimizing for minimal variability in both ratio and intensity, we choose S-Medium as the medium for preparing, storing, and applying UCNPs in the following ex vivo and in vivo tests. More rigorously, we minimize time-dependent effects by performing experiments within 24 h of ligand-stripping the nanoparticles.

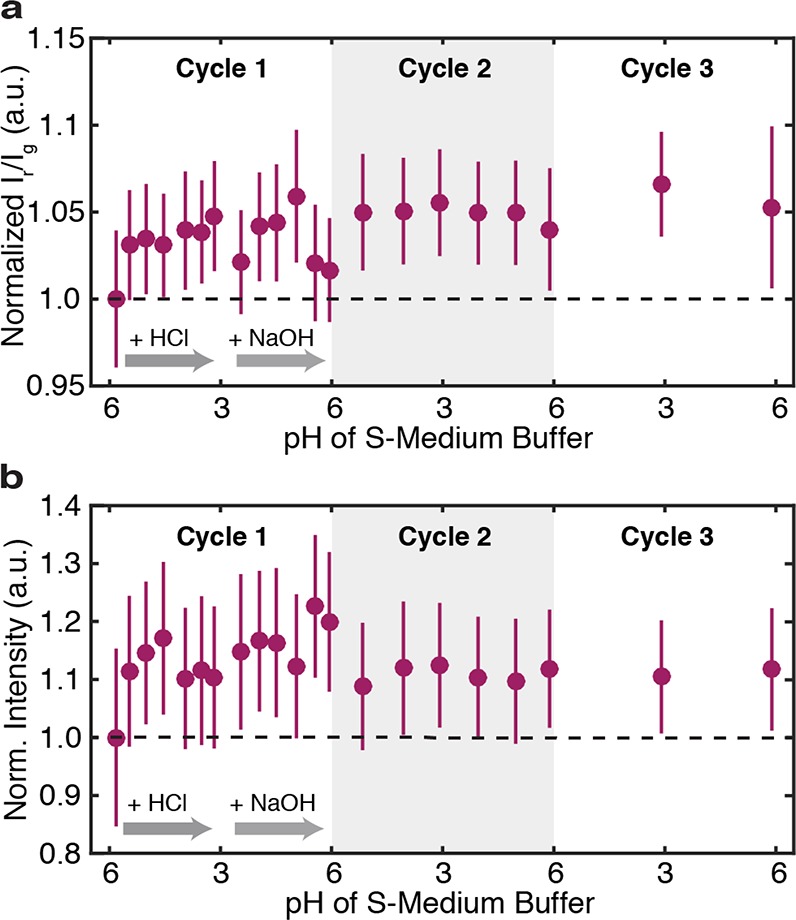

pH Stability of UCNPs in S-Medium

Mechanical sensors should have high sensitivity for mechanical stress and low sensitivity for other external stimuli. pH is one such variable with vital implications in biology. Cell cultures, for example, require stable pH levels, necessitating the use of pH buffers that either mimic or reproduce those found in nature.67 However, pH changes are also necessary for certain biological processes to occur, such as activating enzymes or breaking down food or waste.68,69 Chauhan et al. mapped the relevant pH values in nematode worms, C. elegans, from around pH 6 to pH 4 along its digestive tract.70 Because this range of pH values is present in the same systems in which we would like to record mechanical signals, we need to ensure that our nanoparticles have minimal pH sensitivity. To characterize how the nanoparticles’ optical properties change with pH, we perform ex vivo experiments on LS nanoparticles suspended in S-Medium buffer. We incrementally tune S-Medium down to pH 3 by adding hydrochloric acid (HCl) dropwise and then reverse that acidification with sodium hydroxide (NaOH).

Over continuous pH cycles, we observe little change in upconversion emission. In Figure 4a, given normalization to the starting red-to-green ratio of 7.3, there is a ∼5% increase of the ratio from pH 6 to pH 3 in the first cycle. This increase persists throughout the cycles, making the particles “redder” overall, though this effect is within the error of measurements or the standard deviation over 9 spectra collected at each data point. In Figure 4b, the average intensity increases within the first acidification step and thereafter steadies at ∼10% above the initial value. Fluctuations in ratio and intensity are associated with dynamic changes to the nanoparticles’ surface charge upon protonation and deprotonation, which alter coupling to OH vibrational modes that in turn influence radiative and nonradiative probabilities.46,56 Here, we account for the dilution of nanoparticle concentration with the addition of acidic and basic solutions and correct the intensity values accordingly. The uncorrected data and additional cycles are provided in the SI (Figure S9).

Figure 4.

pH dependence of upconversion in S-Medium. Changes in normalized (a) red-to-green ratio and (b) intensity from initial values (dashed lines) due to pH. For each cycle, hydrochloric acid (HCl) is added to lower the pH of S-Medium down to pH 3, and then, sodium hydroxide (NaOH) is added to increase the pH back to pH 6. Error bars represent the standard deviation of values analyzed from 9 spectra collected at each point. In part b, intensity values are corrected for the dilution of particle concentration as a result of adding acidic and basic solutions (see the Methods section). See Figure S9 for additional cycles and uncorrected intensity data.

The nanoparticles’ robustness to pH is likely due to the buffer solution we have chosen. In a previous study using PBS, core–shell nanoparticles with an 8 nm shell thickness showed irreversible intensity loss at pH 4.65 Additionally, Liu et al. report particle etching (3 nm in diameter) at pH 3 after 1 h, which we do not observe to the same extent, even after five pH cycles performed over 2 h. Our particles before and after pH cycling have diameters of 29.7 ± 4.0 and 28.1 ± 4.4 nm, respectively (see the SI). Importantly, these ex vivo tests simplify a complex biological environment and set a limit of detection and error on upconverting sensors that rely on the emission ratio for detecting external signals. For example, to use these particles as stress sensors in an environment that varies in pH, changes in the emission ratio need to be above 5%, which corresponds to pressures greater than 0.2 GPa or forces greater than about 0.6 μN using a single nanoparticle’s surface area.

In Vivo Imaging of Upconversion in C. elegans

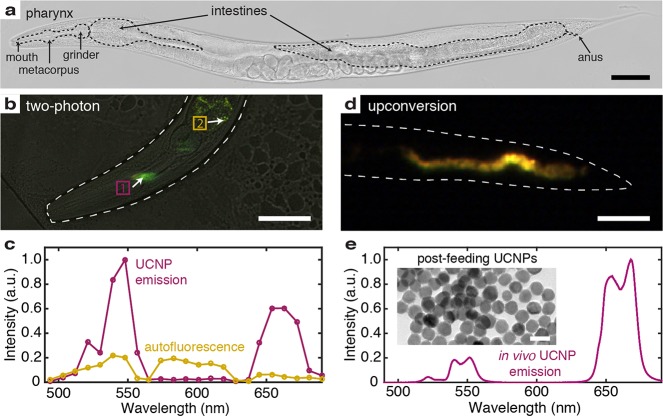

Having determined how the external environment influences the UCNPs, we implement UCNPs for in vivo imaging and evaluate their effect within C. elegans. Only a handful of studies look at upconversion emission along the digestive tract of C. elegans,43,44,71 most recently for the purposes of optogenetics.72,73 These millimeter-long nematode worms are optimal for screening biocompatibility of nanoparticles due to extensive literature on their biology, ease of culture, transparency, predictable reproduction, and low cost.74 Furthermore, because their genome is completely mapped, they are excellent models for understanding health and disease. Their digestive system is similar to that of humans.74 As highlighted in Figure 5a, the digestive system consists of the pharynx, which draws in and crushes up food at the grinder75 in the terminal bulb, followed by intestines along most of its length, where pH gradients and enzymes further break down the food.70,76,77 Finally, undigested food is expelled at the anus.

Figure 5.

In vivo imaging of upconversion in C. elegans. (a) Bright-field (BF) optical image of a C. elegans worm with parts of the digestive system highlighted. Food passes through the pharynx, then the intestines, and is finally expelled through the anus. (b) A composite 2-photon λ scan for wavelengths between 490 and 690 nm is overlaid on a BF confocal image of a worm’s pharynx. An arrow labeled 1 (maroon) marks emission from the metacorpus region, while an arrow labeled 2 (gold) marks emission from a region past the grinder. (c) Spectra from the two marked areas above. Nanoparticle emission is distinct from tissue autofluorescence and shows the characteristic green and red emission peaks of Er3+. (d) Digital images of a worm in a microfluidic channel are collected under illumination from a 980 nm diode laser. Upconversion emission is detected along the worm’s lower intestines without background fluorescence. Here, the yellow–orange is true to the color of upconversion emission and correlates to the ratio of red and green peaks. (e) Upconversion spectrum of nanoparticles, integrated along the worm’s posterior intestines. The inset is a TEM of nanoparticles collected from the liquid S-Medium culture after overnight incubation. All scale bars for worms are 50 μm, while the scale bar for the TEM is 50 nm.

C. elegans worms are fed nanoparticles in a liquid culture with S-Medium and Escherichia coli bacteria, their typical food source. After overnight incubation, we verify that nanoparticles are ingested using two imaging techniques. First, we collect two-photon confocal scans with an excitation wavelength of 980 nm. In Figure 5b, we overlay the bright-field (BF) image of the worm’s pharynx with a composite λ scan. A λ scan takes a series of images at specific wavelengths between 490 and 690 nm in ∼10 nm intervals, allowing for spectroscopic-like measurements. Along the worm’s pharynx, UCNPs have accumulated past the metacorpus (maroon label). Interestingly, emission is detected beyond the lumen in the surrounding pharyngeal tissue, thereby suggesting that some nanoparticles are endocytosed. Cells are negatively charged, so endocytosis by electrostatic attraction is more likely for positively charged nanoparticles.78 In the previous literature, this phenomenon has been observed for positively charged polyethyleneimine (PEI)-coated UCNPs.43 According to Bogdan et al., the ligand-stripping procedure leaves a surface charge dependent on pH.56 Specifically, the nanoparticles are positively charged at pH 4 while negatively charged at pH 7.4. Intermediary pH values, such as those found throughout the worm, would be expected to give rise to partial deprotonation at the surface.

With two-photon excitation, some autofluorescence is also detected past the grinder in the gut (gold label). Autofluorescence is a product of biomolecules and predominantly expresses itself in the intestines under UV and visible excitation.79 In Figure 5c, spectra for the two locations in the image reveal distinguishing features of particle emission compared to tissue autofluorescence. The former has peaks in the green and red, consistent with Er3+ emission.

Importantly, because upconversion relies on real energy states in the nanoparticle, imaging does not require two-photon excitation. To demonstrate this concept, we illuminate a worm with a continuous-wave (CW) 980 nm diode laser at ∼50 W/cm2, thereby removing background autofluorescence in the fluorescence image (Figure 5d). This image shows how nanoparticles have packed along the lower intestines. Contributions of green and red emission, as seen in the associated spectrum (Figure 5e), result in yellow–orange upconversion emission. At the posterior end, where nanoparticles have experienced the full pH gradient induced by digestion, strong upconversion emission can still be detected. As seen in the inset, nanoparticles collected after feeding show no morphological deformation or significant change in size (34.2 ± 3.1 nm).

Chronic Cytotoxicity of UCNPs in C. elegans

Minimal toxicity has been reported for UCNPs used in C. elegans.43,44,72,73 However, these studies are limited to hexagonal-phase hosts, while the mechanosensitive UCNPs are cubic-phase and contain Lu3+ in the shell. In terms of toxicity, Lu3+ has been less studied than other lanthanides,11 with the potential to be more harmful because of its heavier atomic weight.80 However, in vitro cell cultures do not suggest significant cytotoxicity.81,82 Further, incubation times for feeding C. elegans are 12–15 h, a duration for which lanthanide leaching is minimal, even for unshelled UCNPs.64

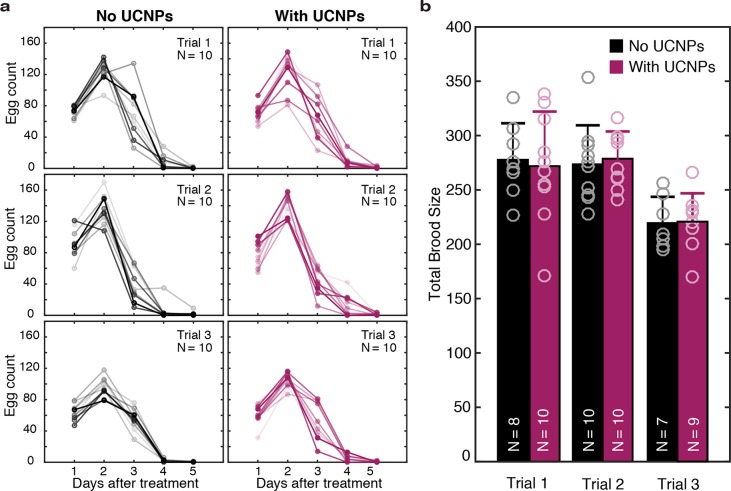

To assess whether or not these nanoparticles are detrimental to the health of C. elegans worms, we perform brood assays, which monitor the number of progeny a worm produces at maturity. Brood assays are considered a highly reliable form of chronic toxicity assay for C. elegans, because egg-laying behavior is consistent in worm cultures across laboratories while other assays (e.g., survival rate or lifespan, presented Figure S10) are not.83,84 We study two treatment conditions: with and without UCNPs. Specifically, worms are either treated with UCNPs (∼0.1 mg per worm) suspended in S-Medium or just S-Medium. After an overnight incubation in liquid culture, we begin the brood assay (see the Methods section). Three trials of the brood assay, each starting with 10 worms per condition, are performed. In Figure 6a, each curve shows the number of eggs an individual worm laid each day. Since worms are treated during their larval (L4) stage, Day 1 after treatment corresponds to worms with the maturity of Day 1 Adults. Consistent with normal reproductive behavior,83 egg-laying reaches a maximum for Day 2 Adults (i.e., Day 2 after treatment) and tapers off by Day 5.

Figure 6.

Biocompatibility of nanoparticles in C. elegans. Three trials of brood assays are conducted to determine the chronic cytotoxicity of nanoparticle ingestion at a concentration of ∼0.1 mg/worm. In each trial, 10 control worms (black lines) and 10 worms treated with UCNPs (maroon lines) are monitored day-to-day after overnight incubation in a liquid S-Medium culture. (a) The number of eggs laid each day after treatment is recorded for individual worms (N = 10 per condition per trial), indicated by different shades of color and line curves. (b) The total brood size is plotted in a bar graph for all three trials. The total brood size is the cumulative egg count from Day 1 to Day 5 after treatment. Worms that did not last the full duration of the study were excluded. Markers represent individual worms; the bar heights represent the mean, and error bars represent the standard deviation.

The cumulative egg count or total brood size is presented in Figure 6b for all three trials. We have excluded worms that did not last the full 5 day count, due to escape from their agar plates or error during plate-to-plate transfer. In Trial 1, the control treatment (no UCNPs) yields an average brood size of 278 ± 34 worms, while treatment with UCNPs yields an average of 272 ± 50 worms. In Trial 2, the values are similar at 274 ± 36 and 279 ± 25 worms, respectively. Meanwhile, Trial 3 shows a smaller brood size across both treatments: 220 ± 24 (without UCNPs) and 221 ± 26 (with UCNPs). These average brood sizes are typical for wild type (N2) worms,83 and the variation across trials or worm populations exceeds the variation between treatments. These results indicate that ingestion and accumulation of UCNPs in the digestive tract do not affect worm reproduction. Such low toxicity allows us to use these UCNPs safely in C. elegans.

There are several considerations for applying nanoparticles to other biological systems, including cells, tissues, and living organisms. First, how nanoparticles are administered affects their distribution in tissues. For instance, Zhou et al. showed that the biodistribution of particles in organs was different if the mice were fed or injected with UCNPs.45 Next, there are fundamental differences between cells and animals. Eating by a cell, or endocytosis, is highly dependent on surface charge; if the charge is positive or cationic, particles are more likely to be engulfed by the cell.78 After particles are endocytosed and compartmentalized in the acidic lysosome, cytotoxicity can be caused by nanoparticles stripping phosphates from the lipid bilayer and transforming into an urchinlike morphology without phosphonate pretreatment.41,42 In contrast, particles that are eaten by C. elegans worms are passed through the digestive tract.43,44 Here, we demonstrate that feeding particles to worms even at concentrations of 0.1 mg/animal has no effect on fecundity, and particles collected after feeding retain their morphology. Although generalizations about toxicity are challenging, our findings suggest that delivering nanoparticles by feeding has few if any deleterious effects on either the particles or the animal.

Conclusions

In summary, we evaluate the biocompatibility of mechanosensitive UCNPs from two perspectives: (1) the effect of buffer and pH on their structural stability, mechanosensitivity, and optical performance, and (2) their potential toxicity in C. elegans. On the basis of a series of ex vivo and in vivo tests, our ligand-stripped core–shell nanoparticles are highly mechanosensitive, pH-stable in S-Medium, and nontoxic by ingestion, rendering them useful for in vivo mechanosensing. More generally, our work highlights the importance of characterizing interactions between nanoparticles and their environment to optimize their use in biology. In the case of mechanosensors, we can better distinguish real signals from noise and determine detection limits. It is important to note that optimization steps will vary depending on the specific biological application. For instance, additional analyses will be needed to assess their functionality and toxicity in intracellular environments for applications that depend on delivering the nanoparticles to the cellular cytoplasm. Our focus here has been on the functionality of mechanosensitive nanoparticles in extracellular environments, such as the fluid cavities inside organs or potentially applied to tissue slices in vitro. Indeed, the nanoparticles developed and characterized in this study may also be useful for mechanical studies of the digestive organs of other animals as well as other fluid-filled organs, such as the vertebrate eye.

While the ensemble measurements we carried out are most relevant for imaging in C. elegans, other applications may hinge on single-particle measurements, which could increase the dissolution rate and quench emission within several hours.48,49 More sophisticated surface modification techniques, including ligand-exchange and additive coatings,42,50−53 may then be required for improved stability or implemented to expand bioconjugation capabilities. This decision will then have consequences in sensing capabilities, toxicity, and other measurements of biocompatibility. Given optimization of optical performance and toxicity through application-specific characterization, mechanosensitive UCNPs promise a new way to study mechanobiology, starting with background-free visualizations of mechanical events in living cells, tissues, and animals.

Methods

Synthesis of Core–Shell UCNPs

Cubic-phase core–shell nanoparticles (NaYF4:Yb,Er@NaLuF4) are synthesized according to methods detailed in our earlier work38 and modified from Li et al.85 Briefly, cores are synthesized in a 250 mL round-bottom flask containing a mixture of 5 mmol of Ln(CF3COO)3 (Ln = 80% Y, 18% Yb, and 2% Er), 5 mmol of Na(CF3COO), 16 mL of oleic acid (OA), and 32 mL of octadecene (ODE). The mixture is heated to 150 °C for 1 h and then cooled to 50 °C before adding 16 mL of oleylamine (OM). Following the addition of OM, the mixture is heated to 100 °C and stirred under vacuum for 30 min. The flask is then purged with argon gas and heated to 310 °C. The reaction is stopped 20 min later by removing the heating mantle and cooled to room temperature. After cleaning with ethanol three times (centrifugation at 3000 RCF for 5–10 min), the nanoparticles are suspended in 25 mL of cyclohexane before shelling.

Shelling is performed in a 50 mL flask. First, the precursors (0.2 mmol of Na(CF3COO), 0.2 mmol of Ln(CF3COO)3, 5 mL of OA, and 5 mL of ODE) are mixed, heated to 150 °C for 1 h, and then cooled to 50 °C. Portions of 1 mL of the cores in cyclohexane are then added before heating the mixture to 100 °C and pulling vacuum for 30 min. Following an argon purge, the mixture is heated to 310 °C and allowed to react for 30 min. Finally, core–shell nanoparticles are cleaned as above and suspended in 2 mL of cyclohexane.

Ligand-Stripping UCNPs

As synthesized (AS) nanoparticles are transferred to a scintillation vial of known mass. The cyclohexane solvent is allowed to evaporate before weighing the vial and determining the mass of UCNPs. Then, a 0.04 M solution of HCl in 80% ethanol and 20% water is added to the vial (∼1–10 mL per 10 mg of UCNPs). The vial is sonicated for 20 min to detach the OA ligand. Afterward, the mixture is transferred to a separatory funnel. DI water and diethyl ether (Sigma-Aldrich) are added to the funnel such that volumetrically, the ratio of the three components is 1:1:1. The funnel is shaken several times to mix the UCNP solution with diethyl ether; the stopper is released to relieve pressure between shakes since diethyl ether is quite volatile. After shaking, the mixture phase-separates with diethyl ether on top and the denser aqueous media below. Stripped OA molecules will remain at the interface, while ligand-stripped (LS) UCNPs remain in the aqueous phase. The stopcock is opened to collect the aqueous phase. The remaining diethyl ether is discarded, and the funnel is rinsed with ethanol before repeating the procedure for the collected UCNPs. This time, only diethyl ether is added to the UCNPs in a 1:1 volumetric ratio. Again, the aqueous phase is collected and transferred to a centrifuge tube, where isopropyl alcohol (IPA) is added such that it comprises more than three-quarters of the total volume. Nanoparticles are crashed out at 3000 RCF for 10 min. Residual solvent is allowed to dry off before adding buffer solution. For our study in buffers, we prepare 10 mg/mL UCNP solutions. For feeding experiments, we prepare 5 mg/mL UCNP solutions. Note that these concentrations assume perfect yield from the ligand-stripping procedure.

Preparation of Buffers

M9 buffer (pH ∼ 7) was made by mixing 3 g of KH2PO4, 6 g of Na2HPO4, 5 g of NaCl, and 1 L of double-distilled water (ddH2O). HBS was made by adding 4.24 g of NaCl, 0.186 g of KCl, 0.238 g of MgCl2, 0.0524 g of CaCl2, and 1.192 g of HEPES to 500 mL of ddH2O. PBS solution was made from 4 g of NaCl, 0.1 g of KCl, 0.72 g of Na2HPO4, 0.12 g of KH2PO4, and 500 mL of ddH2O. Both HBS and PBS buffers were tuned to pH 7.4 using HCl. For S-Medium, S-Basal was first prepared by adding 23.4 g of NaCl, 4 g of K2HPO4, 24 g of KH2PO4, and 4 mL of cholesterol solution in 95% ethanol (5 mg/mL) to 4000 mL of ddH2O. Then, 12 mL of 1 M MgSO4, 12 mL of 1 M CaCl2, 40 mL of 1 M K-Citrate, and 40 mL of trace metal solution were added. S-Medium has pH ∼6 and osmolarity ∼370 mOsm/kg.

Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

To characterize the samples vibrational modes, we use a Nicolet iS50 FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) located in the Soft and Hybrid Materials Facility (SMF) at Stanford University. The instrument is used in its attenuated total reflectance (ATR) mode. For all samples, a droplet of ∼10 μL of the solution is drop-cast on a glass slide and heated to evaporate the solvent. The dried sample is then placed against the diamond ATR crystal. Spectra are acquired from 500 to 4000 cm–1. A background of the atmosphere is taken and subtracted from all spectra. After acquiring each spectrum, the ATR crystal is wiped clean with hexanes, isopropanol, water, and acetone and allowed to dry.

Particle Analysis

We take transmission electron micrographs

(TEMs) containing ∼100–200 nanoparticles (see Figure S5) on an FEI Tecnai transmission electron

microscope at 200 kV. Due to small interparticle distances, overlapping

nanoparticles, and aggregation, we manually draw circles over nanoparticles

using ImageJ software and calculate their area. Diameter (ds) is calculated from the measured area (As) using the following equation:  . In the SI,

we display histograms of the diameter values for all of our samples

and fit them to a normal distribution to find the mean size and standard

deviation.

. In the SI,

we display histograms of the diameter values for all of our samples

and fit them to a normal distribution to find the mean size and standard

deviation.

Diamond Anvil Cell (DAC) Measurement

Methods for performing DAC spectroscopy to characterize mechanosensitivity are described in detail in our earlier work.38,61 Key modifications include using LS core–shell UCNPs, which are first suspended in S-Medium and drop-cast on a heated glass slide before loading into the DAC sample chamber. Additionally, the hydrostatic pressure medium is methanol:ethanol (4:1). Pressure is related to the shift in ruby R1 photoluminescence from λ0 to λ by the calibration equation: P = (A/B)[(λ/λ0)B – 1], where A = 1904 GPa and B = 5.60,86 Upconversion spectra are collected by illuminating the DAC sample chamber with a CW 980 nm diode laser (Opto Engine) at ∼30 W/cm2 through a 10× Mitutoyo Plan Apo infinity-corrected long working distance objective (0.28 numerical aperture, NA) and spectrometer (Princeton Instruments Acton 2500) parameters: 250 μm slit, 500-Blaze 150 g/mm grating, and 0.21 nm resolution.

Cuvette Spectroscopy and pH Cycling Measurement

A CW 980 nm diode laser (Opto Engine) is fiber-coupled and focused onto a 10 mm path length quartz cuvette (Starna Cells, Inc.) through a collimator with an N-BK7 Plano convex lens (f = 20.0 mm) and an additional Plano convex lens (f = 35.0 mm) from Thorlabs. The incident irradiance is estimated to be 100 W/cm2 with a power of 800 mW and beam diameter of 1 mm. Emission is collected after a 750 nm SP filter by an OceanOptics HR4000 spectrometer.

For pH cycling, 0.48 M HCl and 0.48 M NaOH solutions

in DI water are prepared. pH is measured for a test sample containing

S-Medium buffer to calibrate the volume of acid or base necessary

to tune pH across the relevant range (pH 3 to pH 6) for five cycles.

On the basis of the calibration, HCl and NaOH are added dropwise to

the cuvette containing 1 mL of UCNPs in S-Medium (10 mg/mL). Spectra

is collected after shaking the cuvette using the setup mentioned above.

For intensity corrections, x is added to the raw

normalized intensity values.  . This calculation assumes that intensity

and concentration are linearly related.

. This calculation assumes that intensity

and concentration are linearly related.

C. elegans Culture and Feeding

Wild type (N2) C. elegans worms are cultured at 20 °C on NGM plates seeded with OP50 E. coli bacteria. Worm growth is synchronized with an established bleaching procedure.87 Two and a half days after bleaching, 50 worms in the L4 stage are picked into a liquid culture containing OP50 (OD600 = 0.3), S-Medium, and UCNPs (5 mg/mL) in a 1:4:5 volumetric ratio. A 1 mg portion of UCNPs is used for every 10 worms in the liquid culture. The worms are placed on a shaker in an incubator at 20 °C for 12–15 h overnight. Worms are then collected for imaging experiments or toxicity tests.

Imaging Upconversion Emission in C. elegans

After the feeding procedure, C. elegans worms are picked onto a glass slide with a 5% agarose pad and a drop of 0.2 μm polystyrene beads, as detailed by Kim et al.88 Two-photon confocal microscopy is performed on an Inverted Zeiss LSM 780 instrument, located in the Shriram Cell Sciences Imaging Facility (CSIF) at Stanford University. The microscope is coupled to a Spectra Physics MaiTai, DeepSee ultrafast pulsed laser system for two-photon excitation at 980 nm. The λ scan uses a 32 anode Hybrid-GaAsP detector for spectral unmixing.

For in-house upconversion imaging, we load the worms in a microfluidic device developed by Nekimken et al.89 A 50 μm wide channel confines Adult Day 1 worms in place. We illuminate the channel with the CW 980 nm diode (∼50 W/cm2) that is coupled to a Zeiss Axio Observer inverted microscope, through a 10× objective (0.2 NA). We collect images on an Allied Vision Technologies (AVT) digital camera and collect spectra with a Princeton Instruments Acton 2500 spectrometer and ProEM eXcelon CCD detector using a 500-Blaze 150 groove/mm grating.

Evaluating Chronic Cytotoxicity

After liquid culture, 10 worms from each treatment condition (with and without UCNPs) are put in their individual NGM plates (i.e., 20 worms and 20 plates total). The brood assay is performed double-blind, meaning that the plates are coded by a researcher that does not know which plates are from which treatment condition. For 5 consecutive days thereafter, each worm is picked onto a new agar plate. The original plate is counted 3 days after the transfer, which allows the eggs that were laid on the agar plate to hatch and mature, improving visibility for counting. To minimize movement from the worms during counting, plates are put in the fridge for ∼10 min prior to counting. The procedure is repeated every day at about the same time to record day-to-day egg-laying. Five days after treatment, egg-laying stops, and all worms from one treatment are placed in the same agar plate. For monitoring lifespan, live worms are determined by movement and their response to a gentle tap with a platinum pick.

Safety Statement

No unexpected or unusually high safety hazards were encountered.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alakananda Das, Adam Nekimken, Lingxin Wang, Zhiwen Liao, Cedric Espenel, Feng Ke, Wendy Mao, Katherine Sytwu, and David Barton III for feedback and support. A.L., O.H.S., C.A.M., R.D.M., M.B.G., and J.A.D. acknowledge financial support from the Stanford Bio-X Interdisciplinary Initiatives Committee (IIP) and NIH R21 grant 5R21GM129879-02. A.L. was also previously on NSF GRFP (2013156180). C.S. was supported by an Eastman Kodak fellowship. S.F. and J.A.D. acknowledge support from the Photonics at Thermodynamic Limits Energy Frontier Research Center, funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Award DE-SC0019140. TEM imaging was performed at the Stanford Nano Shared Facilities (SNSF)/Stanford Nanofabrication Facility (SNF), supported by the National Science Foundation under Award ECCS-1542152. Additionally, FTIR spectroscopy was performed at Stanford University’s Soft and Hybrid Materials Facility (SMF), and confocal microscopy was performed at the Stanford Shriram Cell Sciences Imaging Facility (CSIF).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acscentsci.9b00300.

FTIR spectrum of glass slide; upconversion energetics with OH bonds; power-dependence of red-to-green ratio; pressure cycles and response of red and green emission; TEMs, particle analysis, and emission properties of nanoparticles in aqueous media for over 3 weeks; citrate and cholesterol controls; pH-cycling TEMs and emission properties; and C. elegans lifespan assay (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Lohse S. E.; Murphy C. J. Applications of colloidal inorganic nanoparticles: from medicine to energy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 15607–15620. 10.1021/ja307589n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giner-Casares J. J.; Henriksen-Lacey M.; Coronado-Puchau M.; Liz-Marzan L. M. Inorganic nanoparticles for biomedicine: where materials scientists meet medical research. Mater. Today 2016, 19, 19–28. 10.1016/j.mattod.2015.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.; Kim J.; Park Y. I.; Lee N.; Hyeon T. Recent development of inorganic nanoparticles for biomedical imaging. ACS Cent. Sci. 2018, 4, 324–336. 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z.; Le N. D.; Gupta A.; Rotello V. M. Cell surface-based sensing with metallic nanoparticles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 4264–4274. 10.1039/C4CS00387J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W.; Chen X. Gold nanoparticles for photoacoustic imaging. Nanomedicine 2015, 10, 299–320. 10.2217/nnm.14.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parchur A. K.; Sharma G.; Jagtap J. M.; Gogineni V. R.; LaViolette P. S.; Flister M. J.; White S. B.; Joshi A. Vascular interventional radiology-guided photothermal therapy of colorectal cancer liver metastasis with theranostic gold nanorods. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 6597–6611. 10.1021/acsnano.8b01424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djurišić A. B.; Leung Y. H.; Ng A. M.; Xu X. Y.; Lee P. K.; Degger N.; Wu R. Toxicity of metal oxide nanoparticles: mechanisms, characterization, and avoiding experimental artefacts. Small 2015, 11, 26–44. 10.1002/smll.201303947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martynenko I.; Litvin A.; Purcell-Milton F.; Baranov A.; Fedorov A.; Gun’ko Y. Application of semiconductor quantum dots in bioimaging and biosensing. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 6701–6727. 10.1039/C7TB01425B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya K.; Mukherjee S. P.; Gallud A.; Burkert S. C.; Bistarelli S.; Bellucci S.; Bottini M.; Star A.; Fadeel B. Biological interactions of carbon-based nanomaterials: from coronation to degradation. Nanomedicine 2016, 12, 333–351. 10.1016/j.nano.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmer E.; Acosta-Mora P.; Méndez-Ramos J.; Fischer S. Optical nanoprobes for biomedical applications: shining a light on upconverting and near-infrared emitting nanoparticles for imaging, thermal sensing, and photodynamic therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 4365–4392. 10.1039/C7TB00403F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnach A.; Lipinski T.; Bednarkiewicz A.; Rybka J.; Capobianco J. A. Upconverting nanoparticles: assessing the toxicity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 1561–1584. 10.1039/C4CS00177J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soenen S. J.; Parak W. J.; Rejman J.; Manshian B. (Intra) cellular stability of inorganic nanoparticles: effects on cytotoxicity, particle functionality, and biomedical applications. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 2109–2135. 10.1021/cr400714j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casals E.; Casals G.; Puntes V.; Rosenholm J. M.. Theranostic Bionanomaterials; Elsevier, 2019; pp 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Derfus A. M.; Chan W. C.; Bhatia S. N. Probing the cytotoxicity of semiconductor quantum dots. Nano Lett. 2004, 4, 11–18. 10.1021/nl0347334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardman R. A toxicologic review of quantum dots: toxicity depends on physicochemical and environmental factors. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006, 114, 165–172. 10.1289/ehp.8284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poland C. A.; Duffin R.; Kinloch I.; Maynard A.; Wallace W. A.; Seaton A.; Stone V.; Brown S.; MacNee W.; Donaldson K. Carbon nanotubes introduced into the abdominal cavity of mice show asbestos-like pathogenicity in a pilot study. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2008, 3, 423. 10.1038/nnano.2008.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostarelos K. The long and short of carbon nanotube toxicity. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 774. 10.1038/nbt0708-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore T. L.; Rodriguez-Lorenzo L.; Hirsch V.; Balog S.; Urban D.; Jud C.; Rothen-Rutishauser B.; Lattuada M.; Petri-Fink A. Nanoparticle colloidal stability in cell culture media and impact on cellular interactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 6287–6305. 10.1039/C4CS00487F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cedervall T.; Lynch I.; Lindman S.; Berggård T.; Thulin E.; Nilsson H.; Dawson K. A.; Linse S. Understanding the nanoparticle–protein corona using methods to quantify exchange rates and affinities of proteins for nanoparticles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 2050–2055. 10.1073/pnas.0608582104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkilany A. M.; Nagaria P. K.; Hexel C. R.; Shaw T. J.; Murphy C. J.; Wyatt M. D. Cellular uptake and cytotoxicity of gold nanorods: molecular origin of cytotoxicity and surface effects. Small 2009, 5, 701–708. 10.1002/smll.200801546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenzer S.; Docter D.; Kuharev J.; Musyanovych A.; Fetz V.; Hecht R.; Schlenk F.; Fischer D.; Kiouptsi K.; Reinhardt C.; et al. Rapid formation of plasma protein corona critically affects nanoparticle pathophysiology. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 772. 10.1038/nnano.2013.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvati A.; Pitek A. S.; Monopoli M. P.; Prapainop K.; Bombelli F. B.; Hristov D. R.; Kelly P. M.; Åberg C.; Mahon E.; Dawson K. A. Transferrin-functionalized nanoparticles lose their targeting capabilities when a biomolecule corona adsorbs on the surface. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 137. 10.1038/nnano.2012.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittler S.; Greulich C.; Diendorf J.; Koller M.; Epple M. Toxicity of silver nanoparticles increases during storage because of slow dissolution under release of silver ions. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 4548–4554. 10.1021/cm100023p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F.; Banerjee D.; Liu Y.; Chen X.; Liu X. Upconversion nanoparticles in biological labeling, imaging, and therapy. Analyst 2010, 135, 1839–1854. 10.1039/c0an00144a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S.; Han G.; Milliron D. J.; Aloni S.; Altoe V.; Talapin D. V.; Cohen B. E.; Schuck P. J. Non-blinking and photostable upconverted luminescence from single lanthanide-doped nanocrystals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009, 106, 10917–10921. 10.1073/pnas.0904792106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F.; Han Y.; Lim C. S.; Lu Y.; Wang J.; Xu J.; Chen H.; Zhang C.; Hong M.; Liu X. Simultaneous phase and size control of upconversion nanocrystals through lanthanide doping. Nature 2010, 463, 1061–1065. 10.1038/nature08777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S.; Weitemier A. Z.; Zeng X.; He L.; Wang X.; Tao Y.; Huang A. J.; Hashimotodani Y.; Kano M.; Iwasaki H.; et al. Near-infrared deep brain stimulation via upconversion nanoparticle–mediated optogenetics. Science 2018, 359, 679–684. 10.1126/science.aaq1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Q.; Liu H.; Wang B.; Wu Q.; Pu R.; Zhou C.; Huang B.; Peng X.; Ågren H.; He S. Achieving high-efficiency emission depletion nanoscopy by employing cross relaxation in upconversion nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1058. 10.1038/s41467-017-01141-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Lu Y.; Yang X.; Zheng X.; Wen S.; Wang F.; Vidal X.; Zhao J.; Liu D.; Zhou Z.; et al. Amplified stimulated emission in upconversion nanoparticles for super-resolution nanoscopy. Nature 2017, 543, 229. 10.1038/nature21366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J.; Yang P.; Sun M.; Bi H.; Liu B.; Yang D.; Gai S.; He F.; Lin J. Highly emissive dye-sensitized upconversion nanostructure for dual-photosensitizer photodynamic therapy and bioimaging. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 4133–4144. 10.1021/acsnano.7b00944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri A.; Arandiyan H.; Boyer C.; Lim M. Lanthanide-doped upconversion nanoparticles: emerging intelligent light-activated drug delivery systems. Advanced Science 2016, 3, 1500437. 10.1002/advs.201500437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu B.; Zhang Q. Recent advances on functionalized upconversion nanoparticles for detection of small molecules and ions in biosystems. Advanced Science 2018, 5, 1700609. 10.1002/advs.201700609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brites C. D.; Balabhadra S.; Carlos L. D. Lanthanide-based thermometers: at the cutting-edge of luminescence thermometry. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2019, 7, 1801239. 10.1002/adom.201801239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlenbacher R. D.; Kolbl R.; Lay A.; Dionne J. A. Nanomaterials for in vivo imaging of mechanical forces and electrical fields. Nature Reviews Materials 2018, 3, 17080. 10.1038/natrevmats.2017.80. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tajon C. A.; Yang H.; Tian B.; Tian Y.; Ercius P.; Schuck P. J.; Chan E. M.; Cohen B. E. Photostable and efficient upconverting nanocrystal-based chemical sensors. Opt. Mater. 2018, 84, 345–353. 10.1016/j.optmat.2018.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieg M.; Dunn A. R.; Goodman M. B. Mechanical control of the sense of touch by β-spectrin. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 224. 10.1038/ncb2915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingber D. Mechanobiology and diseases of mechanotransduction. Ann. Med. 2003, 35, 564–577. 10.1080/07853890310016333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lay A.; Siefe C.; Fischer S.; Mehlenbacher R. D.; Ke F.; Mao W. L.; Alivisatos A. P.; Goodman M. B.; Dionne J. A. Bright, Mechanosensitive Upconversion with Cubic-Phase Heteroepitaxial Core–Shell Nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 4454–4459. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b01535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin S.; Zhang X.; Zhan C.; Wu J.; Xu J.; Cheung J. Measuring single cardiac myocyte contractile force via moving a magnetic bead. Biophys. J. 2005, 88, 1489–1495. 10.1529/biophysj.104.048157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das G. K.; Stark D. T.; Kennedy I. M. Potential toxicity of up-converting nanoparticles encapsulated with a bilayer formed by ligand attraction. Langmuir 2014, 30, 8167–8176. 10.1021/la501595f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R.; Ji Z.; Chang C. H.; Dunphy D. R.; Cai X.; Meng H.; Zhang H.; Sun B.; Wang X.; Dong J.; et al. Surface interactions with compartmentalized cellular phosphates explain rare earth oxide nanoparticle hazard and provide opportunities for safer design. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 1771–1783. 10.1021/nn406166n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R.; Ji Z.; Dong J.; Chang C. H.; Wang X.; Sun B.; Wang M.; Liao Y.-P.; Zink J. I.; Nel A. E.; et al. Enhancing the imaging and biosafety of upconversion nanoparticles through phosphonate coating. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 3293–3306. 10.1021/acsnano.5b00439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.; Guo C.; Wang M.; Huang L.; Wang L.; Mi C.; Li J.; Fang X.; Mao C.; Xu S. Controllable synthesis of NaYF4: Yb, Er upconversion nanophosphors and their application to in vivo imaging of Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 2632–2638. 10.1039/c0jm02854a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J.-C.; Yang Z.-L.; Dong W.; Tang R.-J.; Sun L.-D.; Yan C.-H. Bioimaging and toxicity assessments of near-infrared upconversion luminescent NaYF4: Yb, Tm nanocrystals. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 9059–9067. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M.; Ge X.; Ke D.-M.; Tang H.; Zhang J.-Z.; Calvaresi M.; Gao B.; Sun L.; Su Q.; Wang H. The Bioavailability, Biodistribution, and Toxic Effects of Silica-Coated Upconversion Nanoparticles in vivo. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 218. 10.3389/fchem.2019.00218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong T.; Ding Y.; Xin S.; Hong X.; Zhang H.; Liu Y. Solvent-induced luminescence variation of upconversion nanoparticles. Langmuir 2016, 32, 13200–13206. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b03593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Würth C.; Kaiser M.; Wilhelm S.; Grauel B.; Hirsch T.; Resch-Genger U. Excitation power dependent population pathways and absolute quantum yields of upconversion nanoparticles in different solvents. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 4283–4294. 10.1039/C7NR00092H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahtinen S.; Lyytikainen A.; Pakkila H.; Homppi E.; Perala N.; Lastusaari M.; Soukka T. Disintegration of hexagonal NaYF4: Yb3+, Er3+ upconverting nanoparticles in aqueous media: the role of fluoride in solubility equilibrium. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 656–665. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b09301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dukhno O.; Przybilla F.; Muhr V.; Buchner M.; Hirsch T.; Mély Y. Time-dependent luminescence loss for individual upconversion nanoparticles upon dilution in aqueous solution. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 15904–15910. 10.1039/C8NR03892A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhr V.; Wilhelm S.; Hirsch T.; Wolfbeis O. S. Upconversion nanoparticles: from hydrophobic to hydrophilic surfaces. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 3481–3493. 10.1021/ar500253g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm S.; Kaiser M.; Würth C.; Heiland J.; Carrillo-Carrion C.; Muhr V.; Wolfbeis O. S.; Parak W. J.; Resch-Genger U.; Hirsch T. Water dispersible upconverting nanoparticles: effects of surface modification on their luminescence and colloidal stability. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 1403–1410. 10.1039/C4NR05954A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quarta A.; Curcio A.; Kakwere H.; Pellegrino T. Polymer coated inorganic nanoparticles: tailoring the nanocrystal surface for designing nanoprobes with biological implications. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 3319–3334. 10.1039/c2nr30271c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang G.; Pichaandi J.; Johnson N. J.; Burke R. D.; Van Veggel F. C. An effective polymer cross-linking strategy to obtain stable dispersions of upconverting NaYF4 nanoparticles in buffers and biological growth media for biolabeling applications. Langmuir 2012, 28, 3239–3247. 10.1021/la204020m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabouw F. T.; Prins P. T.; Villanueva-Delgado P.; Castelijns M.; Geitenbeek R. G.; Meijerink A. Quenching pathways in NaYF4: Er3+, Yb3+ upconversion nanocrystals. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 4812–4823. 10.1021/acsnano.8b01545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian K.; Singh A. K.; Hennig R. G.; Wang Z.; Hanrath T. The nanocrystal superlattice pressure cell: a novel approach to study molecular bundles under uniaxial compression. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 4763–4766. 10.1021/nl501905a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan N.; Vetrone F.; Ozin G. A.; Capobianco J. A. Synthesis of ligand-free colloidally stable water dispersible brightly luminescent lanthanide-doped upconverting nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 835–840. 10.1021/nl1041929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattley C. A.; Stavrinadis A.; Beal R.; Moghal J.; Cook A. G.; Grant P. S.; Smith J. M.; Assender H.; Watt A. A. Colloidal synthesis of lead oxide nanocrystals for photovoltaics. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 2802–2804. 10.1039/b926176a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R. B.; Smith S. J.; May P. S.; Berry M. T. Revisiting the NIR-to-visible upconversion mechanism in β-NaYF4: Yb3+, Er3+. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 36–42. 10.1021/jz402366r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossan M. Y.; Hor A.; Luu Q.; Smith S. J.; May P. S.; Berry M. T. Explaining the nanoscale effect in the upconversion dynamics of β-NaYF4: Yb3+, Er3+ core and core–shell nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 16592–16606. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b04567. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz S.; Chervin J.; Munsch P.; Le Marchand G. Hydrostatic limits of 11 pressure transmitting media. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2009, 42, 075413. 10.1088/0022-3727/42/7/075413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lay A.; Wang D. S.; Wisser M. D.; Mehlenbacher R. D.; Lin Y.; Goodman M. B.; Mao W. L.; Dionne J. A. Upconverting nanoparticles as optical sensors of nano-to micro-Newton forces. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 4172–4177. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b00963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y.; Zhou J.; Xu D. Solvent effect on pressure-induced phase transition in oleic ccid. High Pressure Res. 2014, 34, 243–249. 10.1080/08957959.2013.859685. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D.; Xie G.; Luo J. Mechanical properties of nanoparticles: basics and applications. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2014, 47, 013001. 10.1088/0022-3727/47/1/013001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.-F.; Sun L.-D.; Xiao J.-W.; Feng W.; Zhou J.-C.; Shen J.; Yan C.-H. Rare-Earth Nanoparticles with Enhanced Upconversion Emission and Suppressed Rare-Earth-Ion Leakage. Chem. - Eur. J. 2012, 18, 5558–5564. 10.1002/chem.201103485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D.; Xu X.; Wang F.; Zhou J.; Mi C.; Zhang L.; Lu Y.; Ma C.; Goldys E.; Lin J.; et al. Emission stability and reversibility of upconversion nanocrystals. J. Mater. Chem. C 2016, 4, 9227–9234. 10.1039/C6TC02990F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duong H. T.; Chen Y.; Tawfik S. A.; Wen S.; Parviz M.; Shimoni O.; Jin D. Systematic investigation of functional ligands for colloidal stable upconversion nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 4842–4849. 10.1039/C7RA13765F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagle H. Buffer combinations for mammalian cell culture. Science 1971, 174, 500–503. 10.1126/science.174.4008.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H.; Fan J.; Xu Q.; Li H.; Wang J.; Gao P.; Peng X. Imaging of lysosomal pH changes with a fluorescent sensor containing a novel lysosome-locating group. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 11766–11768. 10.1039/c2cc36785h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beasley D. E.; Koltz A. M.; Lambert J. E.; Fierer N.; Dunn R. R. The evolution of stomach acidity and its relevance to the human microbiome. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0134116 10.1371/journal.pone.0134116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan V. M.; Orsi G.; Brown A.; Pritchard D. I.; Aylott J. W. Mapping the pharyngeal and intestinal pH of Caenorhabditis elegans and real-time luminal pH oscillations using extended dynamic range pH-sensitive nanosensors. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 5577–5587. 10.1021/nn401856u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S. F.; Riehn R.; Ryu W. S.; Khanarian N.; Tung C.-k.; Tank D.; Austin R. H. In vivo and scanning electron microscopy imaging of upconverting nanophosphors in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nano Lett. 2006, 6, 169–174. 10.1021/nl0519175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal A.; Liu H.; Jayakumar M. K. G.; Andersson-Engels S.; Zhang Y. Quasi-Continuous Wave Near-Infrared Excitation of Upconversion Nanoparticles for Optogenetic Manipulation of C. elegans. Small 2016, 12, 1732–1743. 10.1002/smll.201503792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ao Y.; Zeng K.; Yu B.; Miao Y.; Hung W.; Yu Z.; Xue Y.; Tan T. T. Y.; Xu T.; Zhen M. An Upconversion Nanoparticle Enables Near Infrared-Optogenetic Manipulation of the C. elegans Motor Circuit. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 3373. 10.1021/acsnano.8b09270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Moragas L.; Roig A.; Laromaine A. C. elegans as a tool for in vivo nanoparticle assessment. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 219, 10–26. 10.1016/j.cis.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang-Yen C.; Avery L.; Samuel A. D. Two size-selective mechanisms specifically trap bacteria-sized food particles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009, 106, 20093–20096. 10.1073/pnas.0904036106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender A.; Woydziak Z. R.; Fu L.; Branden M.; Zhou Z.; Ackley B. D.; Peterson B. R. Novel acid-activated fluorophores reveal a dynamic wave of protons in the intestine of Caenorhabditis elegans. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 636–642. 10.1021/cb300396j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer J.; Johnson D.; Nehrke K. Oscillatory transepithelial H+ flux regulates a rhythmic behavior in C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 2008, 18, 297–302. 10.1016/j.cub.2008.01.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fröhlich E. The role of surface charge in cellular uptake and cytotoxicity of medical nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 5577. 10.2147/IJN.S36111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pincus Z.; Mazer T. C.; Slack F. J. Autofluorescence as a measure of senescence in C. elegans: look to red, not blue or green. Aging 2016, 8, 889. 10.18632/aging.100936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González V.; Vignati D. A.; Pons M.-N.; Montarges-Pelletier E.; Bojic C.; Giamberini L. Lanthanide ecotoxicity: First attempt to measure environmental risk for aquatic organisms. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 199, 139–147. 10.1016/j.envpol.2015.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.; Sun Y.; Cao T.; Peng J.; Liu Y.; Wu Y.; Feng W.; Zhang Y.; Li F. Hydrothermal synthesis of NaLuF4:153Sm, Yb, Tm nanoparticles and their application in dual-modality upconversion luminescence and SPECT bioimaging. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 774–783. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q.; Sun Y.; Yang T.; Feng W.; Li C.; Li F. Sub-10 nm hexagonal lanthanide-doped NaLuF4 upconversion nanocrystals for sensitive bioimaging in vivo. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 17122–17125. 10.1021/ja207078s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muschiol D.; Schroeder F.; Traunspurger W. Life cycle and population growth rate of Caenorhabditis elegans studied by a new method. BMC Ecol. 2009, 9, 14. 10.1186/1472-6785-9-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lithgow G. J.; Driscoll M.; Phillips P. A long journey to reproducible results. Nature 2017, 548, 387. 10.1038/548387a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Liu X.; Chevrier D. M.; Qin X.; Xie X.; Song S.; Zhang H.; Zhang P.; Liu X. Energy Migration Upconversion in Manganese (II)-Doped Nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 13510–13515. 10.1002/ange.201507176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chijioke A. D.; Nellis W.; Soldatov A.; Silvera I. F. The ruby pressure standard to 150 GPa. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 98, 114905. 10.1063/1.2135877. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stiernagle T. Maintenance of C. elegans. WormBook 2006, 1-101-1. 10.1895/wormbook.1.101.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E.; Sun L.; Gabel C. V.; Fang-Yen C. Long-term imaging of Caenorhabditis elegans using nanoparticle-mediated immobilization. PLoS One 2013, 8, e53419 10.1371/journal.pone.0053419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nekimken A. L.; Fehlauer H.; Kim A. A.; Manosalvas-Kjono S. N.; Ladpli P.; Memon F.; Gopisetty D.; Sanchez V.; Goodman M. B.; Pruitt B. L.; et al. Pneumatic stimulation of C. elegans mechanoreceptor neurons in a microfluidic trap. Lab Chip 2017, 17, 1116–1127. 10.1039/C6LC01165A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.