Abstract

Introduction

Health and social care professionals (HSCPs) have increasingly contributed to enhance the care of patients in emergency departments (EDs), particularly for older adults who are frequent ED attendees with significant adverse outcomes. For the first time, the effectiveness of a HSCP team intervention for older adults in the ED has been tested in a large randomised controlled trial (Clinicaltrials.gov, NCT03739515), providing an opportunity to explore the implementation process for this type of intervention. This protocol describes a process evaluation that will to investigate the implementation, delivery and impact of an HSCP team intervention in the ED.

Methods and analysis

Using the Medical Research Council Framework for process evaluations, we will employ a mixed-methods approach to provide a description of the process of implementation and delivery of the HSCP intervention in the ED, evaluate its fidelity, dose and reach and explore the perceptions of key staff members in relations to the mechanisms and contexts of impact at the levels of individuals, physical environment, operations, communication and the broader hospital and healthcare system.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval for this study was received from the HSE Mid-Western Regional Hospital Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 103/18). All participants will be invited to read and sign a written consent form prior to participation. The results of this review will be disseminated through publication in a peer-review journal and presented at relevant conferences.

Keywords: allied health, emergency department, process evaluation, implementation, interdisciplinary care, health service delivery

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first formal process evaluation of the implementation of a health and social care professional team caring for older patients in the emergency department.

The study will employ the Medical Research Council framework for process evaluations.

This study will adopt a mixed-methods approach and involve different stakeholders to investigate the implementation, delivery and impact of the allied health intervention.

Group interviews may introduce biases related to group dynamics and social desirability that we will attempt to overcome using also individual interviews and quantitative data.

Findings will provide key information for future implementations of allied health teams in emergency care settings.

Introduction

Background

Complex interventions have been increasingly employed in an attempt to enhance health service delivery as well as other societal issues.1 Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are traditionally considered as the reference standard for establishing the effectiveness of interventions.1 2 Recent efforts have been made to include process evaluations as a core component of investigations of effectiveness, as stated in a recent Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance document.1 Conducting a process evaluation of an intervention, particularly in the case of complex quality improvement interventions, is important to gain a deeper understanding of the mechanisms influencing effectiveness (or lack of it), to explain discrepancies between expected and observed outcomes, to highlight the complexities of an intervention and the impact of contextual factors on outcomes and thus to better inform implementation.2–4

The MRC framework highlights three key functions of process evaluations: (1) examining the implementation process and its content (fidelity adaptation, dose and reach); (2) understanding the mechanisms of impact (participants’ response to the intervention; mediators; unexpected pathways and consequences) and (3) investigating the influence of the context of the intervention. Such a framework enables to capture the complexities of developing and implementing a health service intervention, so to offer useful insights for future quality improvement. In this process evaluation, we aim to use the MRC framework to evaluate the process, delivery and impact of the implementation of an allied health team-based intervention within an emergency setting.

Intervention characteristics

The present process evaluation will explore the process of implementation of the OPTIMEND intervention (ie, ‘Optimising early assessment and intervention by Health and Social Care Professionals in the Emergency Department’). OPTIMEND is the first RCT aimed to measure the impact of early assessment and intervention by a team of health and social care professionals (HSCPs) working in the emergency department (ED) on the quality, safety and cost-effectiveness of care for older adults, as compared with usual ED care. The HSCP team comprises of a senior physiotherapist, a senior occupational therapist, and a senior medical social worker providing functional assessment, early interventions and discharge plans to adults aged ≥65 years. A total of 354 participants were recruited in the study from December 2018 until May 2019 and randomly allocated to the HSCP intervention or ED usual care (ie, medical team). Participants in both intervention and control groups are followed-up through telephone assessment at 30 days, 4 and 6 months after the ED index visit (ongoing until November 2019). Primary outcomes of the trial include ED length of stay and rates of hospital admissions. Secondary outcomes include function and quality of life (baseline and follow-up), satisfaction with care, ED revisits and healthcare utilisation (follow-up) and cost-effectiveness.

Following the MRC framework for complex interventions,1 the design of the trial was informed by a systematic review of the existing international literature regarding the effectiveness of HSCP interventions in the ED.5 A qualitative study was also conducted with a range of stakeholders including ED patients and their families, ED staff, HSCPs and prehospital staff to explore their views on the role and impact of HSCPs working in teams in the ED. A paper reporting the findings of this phase is currently in submission. We also carried out an analysis of routine observational data to describe the flow of patients who attend a large Irish ED without a dedicated HSCP team in the ED. Allied health team services in the ED are routine practice in certain areas, such as in Australia6; however, the evidence on the impact HSCP teams on the quality, safety and cost-effectiveness of care is limited and heterogeneous. For this reason, there is a dearth of evaluations available on the implementation, delivery and impact of this model of care, often limited to investigations of acceptability or patient/staff satisfaction.7–9 The OPTIMEND is the first study internationally to test the effectiveness an ED-based HSCP team intervention by adopting a robust methodology, thus offering the opportunity to evaluate its implementation.

Theoretical framework

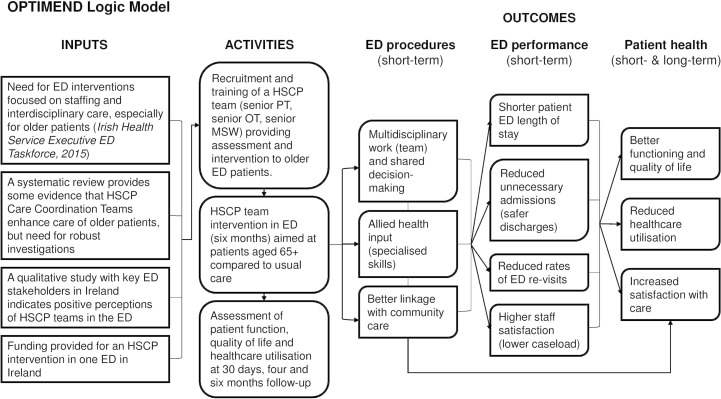

The causal assumptions of the intervention and theoretical framework guiding this evaluation are outlined in the logic model presented in figure 1, based on logic models recommended elsewhere.2 10 A key input for the intervention came from the emergency care national priorities set by the ED taskforce within the Health Service Executive (HSE) in Ireland, which included improving workforce and interdisciplinary care in emergency settings in order to enhance patient and process11 outcomes; following this, funding was secured for the design and implementation of an HSCP team intervention in the ED of a regional hospital in Ireland with a large catchment area, using the MRC framework for complex interventions. A synthesis of the evidence on this model of care and consultations with relevant stakeholders, as described in the previous section, informed the development of the intervention. Key assumptions of this HSCP intervention were that having a multidisciplinary team of professionals with specialised skills in the care of the older person would enhance the quality and timeliness of decision-making (ED processes), and that this would result in shorter stay for older adults as well as reduced rates of unnecessary hospital admissions (ED performance). Ultimately, it is expected that the intervention will benefit patient’s health outcomes by promoting better functioning and quality of life than usual ED care, higher satisfaction with the care received, and a better use of primary and community care.

Figure 1.

HSCP intervention logic model. ED, emergency department; HSCP, health and social care professionals; MSW, medical social worker; PT, physiotherapist; OT, occupational therapist.

Objectives

Based on the characteristics and assumptions of the OPTIMEND trial, the aim of this process evaluation is to understand the functioning and effects of the OPTIMEND intervention by examining how the intervention was delivered and received in practice. In line with the MRC guidelines for process evaluations of complex interventions,2 the study has the following objectives to achieve this aim:

To describe and analyse the implementation of the OPTIMEND trial (what was delivered and how), including an exploration of the intervention fidelity, dose and reach.

To explore the mechanisms of impact within the intervention (ie, barriers and facilitators of implementation in relation to participants’ responses, potential mediators and unexpected pathways).

To highlight contextual influences on impact, delivery and acceptability (ie, individuals, physical environment, ED processes and relations, hospital and healthcare system).

Methods and analysis

Design

The process evaluation will employ a mixed-methods approach to address the above objectives in relation to a HSCP intervention in the ED tested within a randomised controlled trial; the trial for which this process evaluation will be conducted is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03739515; registered on 12 November 2018.

The reporting of this protocol aligns with the Standard Protocol Items for Clinical Trials (SPIRIT) guidelines,12 and a full reporting SPIRIT checklist is presented in the online supplementary file 1. However, given the nature of the study (ie, not a trial but a process evaluation), the protocol has been written by incorporating appropriate elements of the Criteria for Reporting the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions (CReDECI 2) in healthcare (revised guideline),13 particularly in relation to reporting the development and evaluation of the intervention. Key considerations suggested by the MRC2 will be made in relation to the relations between the quantitative and qualitative components of the evaluation and the relation of the process evaluation to other evaluation components (trial outcomes on clinical and cost-effectiveness).

bmjopen-2019-032645supp001.pdf (131.6KB, pdf)

Participants

The evaluation will involve key staff members working in the hospital where the OPTIMEND intervention was carried out (University Hospital Limerick, Ireland), including the HSCPs who implemented the intervention and other staff members who worked in the ED during the OPTIMEND trial and/or contributed to the development and implementation of the intervention. Given the characteristics of the setting and the fact that the intervention was conducted at one site only, it is anticipated that around 20–25 participants will complete the study. Specifically, the following participant categories will be included in the study:

The clinical team involved in the intervention (senior physiotherapist, senior occupational therapist, senior medical social worker, research nurse).

ED doctors (4–5 participants).

ED nurses (4–5 participants).

Other hospital staff members who contributed to the development and implementation of the intervention (eg, Informatics, Planning and Performance Department; Departments managers; other HSCPs).

Participant recruitment will be conducted through convenience and snowball sampling, with prospective participants being identified by the research team and the clinical team involved in the intervention. The clinical team will also act as gatekeepers linking potential participants with the researcher managing enrolment (MC); furthermore, study leaflets will be distributed at UHL. Prospective participants will be provided with an information sheet outlining the evaluation aim and procedure; written informed consent will be sought prior to participation. At the time of submission of this protocol, participants recruitment is ongoing and expected to be completed by the end of July 2019.

Outcomes and measures

Using the MRC process evaluation framework, the study will focus on the measures and research questions outlined in table 1. The process of implementation will be described in terms of activities and processes put in place for the development and delivery of the implementation, the fidelity of the intervention (adherence to protocol and evidence as well as adaptations), its dose and reach. Mechanisms internal to the intervention will be investigated in relation to the participants’ interaction with the intervention, potential mediators and unexpected pathways. Lastly, using a system approach, potential facilitators and barriers to implementation outside of the intervention will be explored at the level of individuals, the ED physical environment, procedures, communication and the broader healthcare system.

Table 1.

Measures, research questions and data collection

| Dimension | Measure | Research questions | Data source | Analysis type |

| Implementation | Process | How was the intervention developed and delivered? What inputs, resources and structures were put into place? |

Team activity logs Interviews/Focus groups |

Quantitative descriptive |

| Fidelity (adherence) | To which extent did the intervention align or diverge from the protocol or international practice? What types of adaptations were made to fit the specific context of care delivery? | Trial protocol Systematic review Interviews/Focus groups |

Quantitative descriptive | |

| Dose | What was the duration, coverage and frequency of the intervention? | Team activity logs Recruitment logs |

Quantitative descriptive | |

| Reach | What proportion of the target population (eligible patients) were enrolled in the intervention? What was the attrition rate? |

Recruitment logs | Quantitative | |

| Mechanisms | Participants’ responses to and interaction with intervention | How did the patients feel about being involved in the intervention? How did other staff members feel about the intervention? |

Interviews/focus groups Data on patients’ satisfaction |

Qualitative and quantitative |

| Mediators | What aspects of the intervention influenced its implementation (people, operations, relations)? | Interviews/focus groups | Qualitative | |

| Unexpected pathways and consequences | Was there something about the intervention that was unexpected and might have influenced its implementation? | Interviews/focus groups | Qualitative | |

| Context | Barriers and facilitators | What factors external to the intervention influenced its implementation and in which way? Consider multiple levels: (1) individuals; (2) ED physical environment; (3) ED operations; (4) ED relations; (5) broader hospital or healthcare system | Interviews/focus groups | Qualitative |

Measures based on the Medical Research Council (MRC) Framework for process evaluations.1

Data collection and analysis

As described in table 1, a mix of quantitative and qualitative methods will be used to address the objectives of this process evaluation.

The content and process of delivery will be evaluated quantitatively through the intervention activity logs. The implementation will also be investigated in terms of fidelity, dose and reach. Fidelity is a central measure in process evaluations4 which provides information on the extent to which the intervention was delivered as planned or adapted to a specific context. Although maintaining appropriate levels of fidelity has been suggested to enhance the impact of intervention,14 debates on the tension between intervention fidelity and adaptation are ongoing, translating into a variety of frameworks attempting to conceptualise fidelity.2 For the purpose of this process evaluation, we will use the framework proposed by Carroll and colleagues4 in relation to implementation fidelity for health services interventions and the MRC guidelines2 to integrate a quantification of adherence, dose and reach with a qualitative exploration of mechanisms of impact within and beyond the intervention. The trial activity logs and recruitment logs will be analysed to quantify and describe the intervention delivery, comparisons will be made with the trial protocol and evidence base (ie, systematic review) to evaluate adherence and dose; descriptive quantitative analyses of participants lost at follow-up will be carried to quantify attrition. Potential modifications will be quantified and described with the help of the clinical team using Stirman’s framework for interventions adaptations15; a detailed evaluation form is included in the online supplementary file 2, which focuses on what was modified and at what level of delivery, the nature of the modification and the agents of the modification.

bmjopen-2019-032645supp002.pdf (61.6KB, pdf)

The qualitative elements of the implementation will be explored via semistructured interviews and focus groups. An interview schedule is presented in the online supplementary file 3, with questions tailored to the trial clinical team and to other staff members. The members of the trial clinical team will be interviewed as a group to describe the process of implementation and delivery, as well as discuss its acceptability and impact; group interviews will also be organised with other members of staff, paying attention to capture the different perspectives of multiple professionals. In addition, prospective participants who do not wish or are not able to take part in the focus groups will be invited to participate in 1:1 semistructured interviews. Group and individual interviews have a number of strengths and weakness which make it preferable to adopt a flexible approach.16 On one hand, working with a group facilitates participants who might have time restrictions or feel at ease contributing as a member of a group; on the other hand, individual interviews provide space to individuals who may be unwilling to contribute within a group and can help to elicit more personal and truthful responses because removing potential biases related to group dynamics and social desirability. The interviews and focus groups will be audio recorded and transcribed. The data will be inputted in the software NVivo V.11 Plus (QSR International Pty Ltd) and analysed using the six steps of thematic analysis,17 18 with the aim to highlight the central themes related to the research questions above. While the analysis will be data driven, the evaluation is informed by an existing framework, thus emerging themes will be compared with the framework to evaluate fit.

bmjopen-2019-032645supp003.pdf (124.6KB, pdf)

By integrating the data collected quantitatively and qualitatively, our analysis will focus on providing a description of the process of implementation as well as considerations of the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention as perceived by key stakeholders involved.

All electronic and hardcopy data will be stored safely by the research team and retained in accordance to the data management policies and procedures of the University of Limerick, Ireland. Access to the data will be limited to the research team members involved in data analysis (MC, KR and RG).

Patient and public involvement statement

This process evaluation will not involve patients directly, as their perceptions of the intervention are investigated as part of the effectiveness study (currently in progress) and it was felt that involving patients in the process evaluation as well may cause a burden without providing novel information. The research questions of this study were informed by the need for quality and timeliness of assessment and intervention in the ED expressed by health service users at a Patient and Public Involvement initiative organised by the Health Service Executive’s Advocacy Unit in Ireland (https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/qid/person-family-engagement/listening-reports/listening-report-16.pdf).

Discussion

Process evaluations have increasingly become an important component of investigations of the effectiveness of health service interventions.1 Despite there are encouraging studies that support the benefits of introducing HSCPs to the ED and promoting interdisciplinary team care, the available evidence on the effectiveness of HSCP team interventions in the ED is limited and presents heterogenous methodologies.5 The completion of the first randomised controlled trial testing the impact of this model of care on patient and process outcomes in a large ED offers the opportunity to gather information on the process of implementation, delivery and impact, particularly in relation to its feasibility and the facilitators and barriers influencing its development, delivery and impact. Adopting the MRC framework for process evaluations1 will help to ensure that key aspects of the implementation process are explored and that the complexities of the intervention are captured in details at multiple levels (from individuals to the healthcare system); furthermore, involving different healthcare professionals in the evaluation will enhance the richness of information gathered, particularly in terms of the practical elements of developing and implementing a complex intervention in a dynamic healthcare setting. While we do not envisage any practical and operational issues arising during the study, the evaluation will be overseen by an interdisciplinary steering group of experts in allied health and emergency care that will ensure the rigorous conduct of the study. The findings of this process evaluation will be integrated with the results on the clinical and cost-effectiveness of the trial (currently in data collection status) to provide insights on the viability of this model of care and formulate recommendations for future implementation in other emergency care settings.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval for this study was received from the HSE Mid-Western Regional Hospital Research Ethics Committee (Ref: REC 103/18) in September 2018. All participants will be invited to read and sign a written consent form prior to participation. The results of this review will be disseminated through publication in a peer-review journal and presented at relevant conferences.

Study status

At the time of submission, the status of this study is currently ‘recruiting’. Recruitment for the study commenced in June 2019 and it is anticipated to be completed by the end of July 2019.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MC and RG were major contributors in writing the protocol. MC and RG designed the study. MC, RG, UC and KR participated in data collection and analysis. RQ, FB, MW, RMN, MOC, GMC and DR participated in the project design and critically appraised and edited the manuscript. RG is the guarantor of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research is supported by the Health Research Board of Ireland through the Research Collaborative for Quality and Patient Safety (RCQPS 2017-2). The sponsor is not involved in the design of the study and collection, analysis, interpretation of data or in writing the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. . Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. . Process evaluation of complex interventions: medical research council guidance. BMJ 2015;350:h1258 10.1136/bmj.h1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hulscher ME, Laurant MG, Grol RP. Process evaluation on quality improvement interventions. Qual Saf Health Care 2003;12:40–6. 10.1136/qhc.12.1.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carroll C, Patterson M, Wood S, et al. . A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement Sci 2007;2:40 10.1186/1748-5908-2-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cassarino M, Robinson K, Quinn R, et al. . Effectiveness of early assessment and intervention by interdisciplinary teams including health and social care professionals in the emergency department: protocol for a systematic review. BMJ Open 2018;8:e023464 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gardner G, Gardner A, Middleton S, et al. . Mapping workforce configuration and operational models in Australian emergency departments: a national survey. Aust Health Rev 2018;42:340 10.1071/AH16231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Holmes C, Hollebon D, Scranney A, et al. . Embedding an allied health service in the Nelson hospital emergency department: a retrospective report of a six month pilot project. New Zeal J Physiother 2016;44:17–25. 10.15619/NZJP/44.1.03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moss JE, Flower CL, Houghton LM, et al. . A multidisciplinary care coordination team improves emergency department discharge planning practice. Med J Aust 2002;177:427–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Corbett HM, Lim WK, Davis SJ, et al. . Care coordination in the Emergency Department: improving outcomes for older patients. Aust Health Rev 2005;29:43–50. 10.1071/AH050043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hasson H. Systematic evaluation of implementation fidelity of complex interventions in health and social care. Implement Sci 2010;5:67 10.1186/1748-5908-5-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. HSE. Emergency Department Task Force. 2015.

- 12. Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. . SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Möhler R, Köpke S, Meyer G. Criteria for reporting the development and evaluation of complex Interventions in healthcare: revised guideline (CReDECI 2). Trials 2015;16:204 10.1186/s13063-015-0709-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dusenbury L, Brannigan R, Falco M, et al. . A review of research on fidelity of implementation: implications for drug abuse prevention in school settings. Health Educ Res 2003;18:237–56. 10.1093/her/18.2.237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stirman SW, Miller CJ, Toder K, et al. . Development of a framework and coding system for modifications and adaptations of evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci 2013;8:65 10.1186/1748-5908-8-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stewart DW, Shamdasani PN. Focus groups: theory and practice. https://books.google.ie/books?hl=en&lr=&id=YU0XBAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=focus+groups+limitations&ots=bDrREIX3Gx&sig=VtCXWwTg1L9pJBWt-C8o8cOJNEk&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=focus%20groups%20limitations&f=false (Accessed 15 May 2019).

- 17. Braun V, Clarke V, Terry G. Thematic analysis. Qual Res Clin Heal Psychol 2012;24:95–114. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-032645supp001.pdf (131.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-032645supp002.pdf (61.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-032645supp003.pdf (124.6KB, pdf)