Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate the association between early-life exposure to the Great Chinese Famine (1959–1961) and the prevalence of poor physical function in midlife.

Design

A population-based historical prospective study was performed as part of a wider cross-sectional survey. Exposure to famine was defined by birthdate, and participants were divided into non-exposed group, fetal-exposed group and infant-exposed group.

Setting and participants

A total of 3595 subjects were enrolled into the study from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) 2015 based on random selection of households that had at least one member aged 45 years old and older in 28 provinces of mainland China.

Main outcome measures

Physical function status was assessed by a six-item self-report on the Barthel scale which rated basic activities of daily living (BADL).

Results

743 (20.7%) out of all participants were exposed to the Great Chinese Famine in their fetal periods, while 1550 (43.1%) participants were exposed at the age of an infant. The prevalence of poor physical function in the non-exposed group, fetal period-exposed group and infant period-exposed group were 12.3%, 15.5% and 17.0%, respectively. Among males, after stratification by gender and severity of famine, the prevalence of poor physical function in the fetal period was significantly higher (OR 2.40, 95% CI 1.18 to 4.89, p=0.015) than the non-exposed group in severely affected areas, even after adjusting for the number of chronic diseases, place of residence, smoking and alcohol drinking habits, marital status, educational level and body mass index. A similar connection between prenatal and early postnatal exposure to the Great Chinese Famine and the prevalence of poor physical function in midlife, however, was not observed from female adults.

Conclusions

Males who were exposed to the Great Chinese Famine (1959–1961) present considerably decreased physical function in their later life.

Keywords: epidemiology, public health, health informatics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study that evaluated the association between prenatal and early postnatal exposure to the Great Chinese Famine and the prevalence of poor physical function in midlife, which this analysis intends to fill in the gap in this range of research.

The study applied the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) 2015 tracking survey, which is a nationally representative longitudinal survey.

Stringent quality control measures were applied in every stage of the CHARLS 2015 tracking survey, which ensured the quality of our study.

Selection bias was inevitable due to excess mortality in early life; this might decrease the real effect of famine exposure on physical function.

Self-reported prevalence based on the Barthel scale could be lower than the real prevalence of poor physical function.

Introduction

The Framework of Life-Course Epidemiology proposes that physical growth and development taking place during the life-cycle, including prenatal life and childhood, have long-term effects and consequences on health and function in adulthood.1 2 Within this framework, the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) assumes that physical adaptations are responses to early life (fetal and infant stages). Undernutrition would lead to bodily changes for early survival, but might increase the prevalence of adult chronic disease,3–5 as well as age-related physical function decline.6 Impaired physical function is an essential manifestation of ageing process, which is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.7 8 Recent literature showed that prenatal undernutrition could result in poor physical function in later life among males; meanwhile, prenatal growth was one factor that predicts physical performance among the elderly.9 Low weight at first postnatal year is associated with some ageing markers such as decreased opacity, low muscular strength10 11 and osteoarthritis in men.12

Furthermore, childhood development and growth have an impact on physical performance in midlife13 and may increase the prevalence of falls in later life.14 Poor childhood health status has a long-range negative influence on adult health outcomes in terms of self-reported health status and successful ageing.15–17 These findings indicate that early life malnutrition may increase the prevalence of poor physical function to a certain extent.

Due to ethical limitations, we cannot perform similar research to examine the DOHaD hypothesis of human beings. However, historical famine provides direct evidence for the hypothesis in humans and provides a quasi-experimental setting for studying the effect of severe undernutrition in early life on inverse health outcomes.18 Due to inclement climatic conditions and radical collectivisation movement, extreme food shortage appeared on the entire mainland China between 1959 and 1961.19 20 Different from the Dutch famine study,21 the Great Chinese Famine caused about 30 million premature deaths, lasted for more extended longer period and was more severe.22 To investigate the association between early life malnutrition and poor physical function in later life in humans, reliable and solid evidence could be provided through the Great Chinese Famine study.

In this study, we employed data derived from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) 2015 to investigate the association between early-life exposure to the Great Chinese Famine and the prevalence of poor physical function in midlife.

Methods

Database

This study was based on nationwide data derived from the CHARLS 2015, which was aimed at providing a high-quality public database with a wide range of information to meet the needs of scientific and policy researchers on ageing-related issues. A total number of 21 096 individuals from 12 235 households were interviewed through a face-to-face questionnaire, and the data collection of the survey was performed from July 2015 to August 2015. The representative samples were collected through a four-stage, stratified, cluster sampling method22 of households with at least one member who aged 45 years old and above, from the 450 communities, 150 counties, 28 provinces of mainland China. The CHARLS 2015 also collected data on height and weight, which was carried out by trained interviewers. To correct for non-response and sampling frame errors in each step of the CHARLS, the CHARLS team created separate weights for individuals and households. The datasets analysed in the current study are available online (http://charls.pku.edu.cn/zh-CN/page/data/2015-charls-wave4).23

Defining famine groups

Participants were divided into a non-exposed group and two famine-exposed groups (fetal-exposed and infant-exposed) by birthdate. The Great Chinese Famine started in January 1959 and ended in October 1961. Due to the fact that the exact dates on which the Great Chinese famine began and ended were not precise, and in order to minimise classification bias, participants born between 1 January 1959 and 30 September 1959 and between 1 October 1961 and 30 September 1962 were excluded.14 The birthdates of the three groups were 10/01/1962 to 09/30/1964 (non-exposed group), 10/01/1959 to 09/30/1961 (fetal stage-exposed group) and 01/01/1956 to 12/31/1958 (infant stage-exposed group).

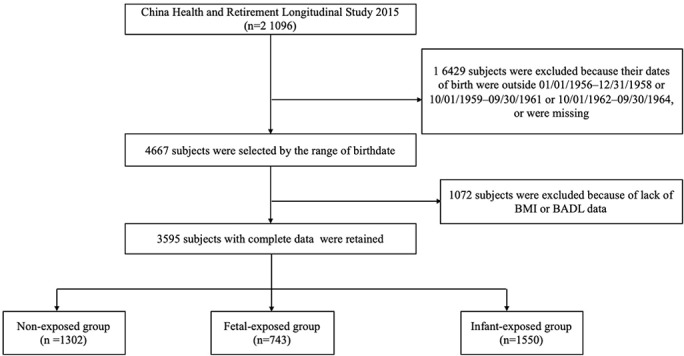

Sample

In the current study, 4667 participants were enrolled into three groups defined by birthdates. After excluding 1072 participants with missing data of body mass index (BMI) or functional limitations, 3595 subjects participated in the study (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart on the sample selection methods in each step. BADL, basic activities of daily living; BMI, body mass index.

Famine severity

Since different provinces in mainland China vary from climate, population density and policies regarding the shortage of foods, the severity of famine fluctuated sharply across regions.24 Excess mortality was the change in mortality rate from the average in 1956–1958 to the highest value among the period of 1959–1962 and was used to reflect the severity of famine exposure in the current study, which is consistent with previous studies.14 24 The regions with excess mortality of 100% were used to differentiate the severely affected areas from the mildly affected areas in this study.25

Measurements

Defining poor physical function

Physical function status was assessed through self-reporting on six items on Barthel’s scale (basic activities of daily living (BADL)),26 a tool for studying the ageing process.27 The six items included dressing, bathing, feeding, getting in or out of bed, toileting and control of urination and defecation. There were four possible responses for each activity: ‘no difficulties', ‘have some difficulties but still can do without help’, ‘need help’ and ‘unable to do’. Poor physical function was identified by the response ‘have some difficulties but still can do without help’, ‘need help’ or ‘unable to do’ in at least one of the six activities.

Assessment of covariates

Covariates such as demographics (birthdate, gender, residence place, education, marital status), lifestyles (smoking and alcohol drinking) and 14 types of self-reported chronic diseases were collected during face-to-face in-house interviews conducted by trained interviewers, and general obesity (body mass index (BMI)) was calculated from the height and weight of the biomarker data. Further, place of residence included urban and rural areas. Educational level was grouped into four stages: primary school or below, middle school, high school, college or above. Marital status was classified into ‘living with spouse’ (married with spouse present, cohabiting) and ‘living without spouse’ (married but temporarily not living with spouse for reasons such as work, separated, divorced, widowed or never married). Smoking status was characterised into ‘never smoked’, ‘past smoking’ and ‘currently smoking’ (smoked at least one cigarette per day in the last year). Alcohol drinking status was categorised into ‘never drank’ and ‘drinker’ (drank at least once per month in the last year). The diagnosis of 14 types of chronic diseases was based on whether the respondents had been diagnosed with any of the following conditions: hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes or elevated blood sugar; malignant tumours such as cancer, chronic lung disease, liver disease, heart disease, stroke, kidney disease, stomach disease or digestive system disease; emotional and mental problems, memory-related diseases, arthritis/rheumatism, and asthma. Participants who replied ‘yes’ were described as suffering from the diagnosed disease, while participants who responded ‘no’ were deemed disease-free. BMI was categorised as underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.5–23.9 kg/m2), overweight (24.0–27.9 kg/m2) or obese (≥28.0 kg/m2) based on the Chinese criteria.28

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean±SD and categorical variables were expressed as frequency (percentages). The χ 2 test was used to compare differences in basic characteristics and the prevalence of poor physical function between the two famine-exposed groups and the non-exposed group.

The association between exposure to famine and poor physical function was determined with binary logistic regression analysis. The unadjusted results and results adjusted for different covariates are presented. Results were adjusted by gender, famine severity, number of chronic diseases, place of residence, smoking, alcohol drinking, marital status, educational level and BMI. In consideration of the possibility that severity of famine might affect people differently, and that early-life exposure affected men and women differently, severity-stratified famine and sex-stratified analyses were applied. Data were expressed as OR and 95% CI. A two-sided p value≤0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses. All statistical analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics V.17 for Windows (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Patient and public involvement

In the present study, we used the data from CHARLS, which is a nationally representative longitudinal survey. The Patients or the public were not involved.

Results

The basic characteristics of the study population are shown in table 1. A total of 3595 participants were involved in the study. The results showed that 743 (20.7%) participants were exposed to the Great Chinese Famine in the fetal period, while 1550 (43.1%) participants were exposed as infants. The prevalence of poor physical function among individuals in the non-exposed group, fetal-exposed group and infant-exposed group was 12.3%, 15.5% and 17.0%, respectively. Compared with the unexposed group, the prevalence of poor physical function was significantly higher in the fetal period-exposed and the infant-exposed groups (p=0.002).

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the study population

| Characteristics | Non-exposed group | Fetal period-exposed group | Infant period-exposed group |

P value |

| Birthdate | 10/1/1962–9/30/1964 | 10/1/1959–9/30/1961 | 01/01/1956–12/31/1958 | |

| n | 1302 | 743 | 1550 | |

| Female, n (%) | 708 (54.4) | 412 (55.5) | 805 (51.9) | 0.216 |

| Born in severely affected area, n (%) | 531 (40.8) | 252 (33.9) | 580 (37.4) | 0.008 |

| Urban, n (%) | 532 (40.9) | 279 (37.6) | 573 (37.0) | 0.087 |

| Living with spouse, n (%) | 1165 (89.5) | 653 (87.9) | 1351 (87.2) | 0.157 |

| Smoking, n (%) | ||||

| Never | 822 (63.1) | 445 (59.9) | 894 (57.7) | 0.024 |

| Past | 119 (9.1) | 84 (11.3) | 190 (12.3) | |

| Current | 361 (27.7) | 214 (28.8) | 466 (30.1) | |

| Alcohol drinking, n (%) | 387 (29.7) | 213 (28.7) | 423 (27.3) | 0.354 |

| Chronic diseases, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 379 (29.1) | 209 (28.1) | 440 (28.4) | 0.694 |

| 1 | 371 (28.5) | 200 (26.9) | 422 (27.2) | |

| 2 | 240 (18.4) | 155 (20.9) | 307 (19.8) | |

| 3 | 147 (11.3) | 89 (12.0) | 177 (11.4) | |

| 4 | 97 (7.5) | 49 (6.6) | 98 (6.3) | |

| ≥5 (multiple) | 68 (5.2) | 41 (5.5) | 106 (6.8) | |

| Education level, n (%) | ||||

| Primary school or below | 602 (46.2) | 356 (47.9) | 929 (59.9) | <0.001 |

| Middle school | 488 (37.5) | 218 (29.3) | 379 (24.5) | |

| High school | 173 (13.3) | 157 (21.1) | 224 (14.5) | |

| College school or above | 39 (4.61) | 12 (1.6) | 18 (1.2) | |

| General obesity (BMI), n (%) | ||||

| Underweight | 43 (3.3) | 22 (3.0) | 81 (5.2) | 0.001 |

| Normal weight | 557 (42.8) | 345 (46.4) | 721 (46.5) | |

| Overweight | 473 (36.3) | 261 (35.1) | 546 (35.2) | |

| Obese | 229 (17.6) | 115 (15.5) | 202 (13.0) | |

| Prevalence of poor physical function, n (%) | 160 (12.3) | 115 (15.5) | 264 (17.0) | 0.002 |

Bold values means P≤0.05, statistical significant level.

BMI, body mass index.

Table 2 shows the prevalence and prevalence of poor physical function. The fetal period-exposed (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.71, p=0.041) and infant period-exposed (OR 1.42, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.76, p=0.002) groups had significantly high prevalence of poor physical function after adjustment for gender, severity of famine, number of chronic diseases, place of residence, smoking, alcohol drinking, marital status, educational level and BMI, compared with the non-exposed group. The same procedures were conducted in analysing the prevalence of high difficulties with dressing, bathing or showering, eating, getting in or out of bed, using the toilet and control of urination and defecation. Compared with the non-exposed group, it was observed that all the famine-exposed groups had significantly increased the prevalence of high difficulty with using the toilet and difficulty with bathing or showering after adjustment for multiple covariates. The infant-exposed group had a significantly higher prevalence of difficulty with dressing (p<0.05). However, no consistent associations were found concerning high difficulty with eating, getting in or out of bed and controlling urination and defecation (p>0.05).

Table 2.

Comparison of prevalence of poor physical function between famine-exposed groups and non-exposed group*

| Prevalence | Crude model | Adjusted model† | |||

| % | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Difficulty with dressing | |||||

| Non-exposed group | 34 (2.6) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Fetal-exposed group | 29 (3.9) | 1.52 (0.92 to 2.51) | 0.106 | 1.54 (0.93 to 2.56) | 0.095 |

| Infant-exposed group | 71 (4.6) | 1.79 (1.18 to 2.71) | 0.006 | 1.72 (1.13 to 2.62) | 0.012 |

| Difficulty with bathing or showering | |||||

| Non-exposed group | 35 (2.7) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Fetal-exposed group | 32 (4.3) | 1.63 (1.00 to 2.65) | 0.050 | 1.66 (1.02 to 2.72) | 0.044 |

| Infant-exposed group | 77 (5.0) | 1.89 (1.26 to 2.84) | 0.002 | 1.75 (1.16 to 2.65) | 0.008 |

| Difficulty with eating | |||||

| Non-exposed group | 16 (1.2) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Fetal-exposed group | 12 (1.6) | 1.32 (0.62 to 2.80) | 0.471 | 1.32 (0.62 to 2.83) | 0.474 |

| Infant-exposed group | 27 (1.7) | 1.43 (0.76 to 2.66) | 0.265 | 1.17 (0.62 to 2.20) | 0.629 |

| Difficulty with getting in or out of bed | |||||

| Non-exposed group | 57 (4.4) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Fetal-exposed group | 37 (5.0) | 1.15 (0.75 to 1.75) | 0.532 | 1.14 (0.74 to 1.75) | 0.553 |

| Infant-exposed group | 76 (4.9) | 1.13 (0.79 to 1.60) | 0.508 | 1.06 (0.74 to 1.51) | 0.760 |

| Difficulty with using the toilet | |||||

| Non-exposed group | 94 (7.2) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Fetal-exposed group | 76 (10.2) | 1.46 (1.07 to 2.01) | 0.018 | 1.46 (1.06 to 2.02) | 0.021 |

| Infant-exposed group | 175 (11.3) | 1.64 (1.26 to 2.13) | <0.001 | 1.61 (1.23 to 2.11) | <0.001 |

| Difficulty with controlling urination and defecation | |||||

| Non-exposed group | 32 (2.5) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Fetal-exposed group | 16 (2.2) | 0.87 (0.48 to 1.60) | 0.662 | 0.89 (0.48 to 1.63) | 0.694 |

| Infant-exposed group | 49 (3.2) | 1.30 (0.83 to 2.04) | 0.261 | 1.20 (0.76 to 1.90) | 0.435 |

| Poor physical function | |||||

| Non-exposed group | 160 (12.3) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Fetal-exposed group | 115 (15.5) | 1.31 (1.01 to 1.69) | 0.042 | 1.32 (1.01 to 1.71) | 0.041 |

| Infant-exposed group | 264 (17.0) | 1.47 (1.19 to 1.81) | <0.001 | 1.42 (1.14 to 1.76) | 0.002 |

*Calculations were made using binary logistic regression analysis. OR represents the ratio of the probability of poor physical function for those who were exposed to famine, compared with those who were not exposed to famine, at 95% CIs.

†Adjusted for gender, famine severity, number of chronic diseases, place of residence, smoking, alcohol drinking, marital status, educational level and body mass index.

Bold values means P≤0.05, statistical significant level.

Table 3 presents the prevalence of poor physical function of the exposed groups, relative to the non-exposed group stratified by severity of famine across the entire mainland China. In less severely affected famine areas, compared with the non-exposed group, only the OR of poor physical function for infant-exposed group was statistically significant (OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.91, p=0.010) even after adjusting for gender, number of chronic diseases, place of residence, smoking, alcohol drinking, marital status, educational level and BMI (OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.87, p=0.018). No consistent association in the fetal period-exposed group was found in poor physical function (p>0.05). However, in severely affected famine area, the OR of poor physical function for infant-exposed (OR 1.55, 95% CI 1.03 to 2.34, p=0.037) and infant groups (OR 1.45,95% CI 1.03 to 2.03, p=0.033) were statistically significant, compared with the non-exposed group, after adjusting for multiple covariates.

Table 3.

Prevalence of poor physical function in birth groups in the Great Chinese Famine area*

| Prevalence | Crude model | Adjusted model† | |||

| % | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Less severely affected famine area | |||||

| Non-exposed group | 91 (11.8) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Fetal-exposed group | 67 (13.6) | 1.18 (0.84 to 1.66) | 0.335 | 1.20 (0.85 to 1.69) | 0.309 |

| Infant-exposed group | 157 (16.2) | 1.44 (1.09 to 1.91) | 0.010 | 1.41 (1.06 to 1.87) | 0.018 |

| Severely affected famine area | |||||

| Non-exposed group | 69 (13.0) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Fetal-exposed group | 48 (19.0) | 1.58 (1.05 to 2.36) | 0.027 | 1.55 (1.03 to 2.34) | 0.037 |

| Infant-exposed group | 107 (18.4) | 1.52 (1.09 to 2.10) | 0.013 | 1.45 (1.03 to 2.03) | 0.033 |

*Calculations were made using binary logistic regression analysis. OR represents the ratio of the probability of poor physical function for those who were exposed to famine, compared with those who were not exposed to famine, at 95% CIs.

†Adjusted for gender, number of chronic diseases, place of residence, smoking, alcohol drinking, marital status, educational level and body mass index.

Bold values means P≤0.05, statistical significant level.

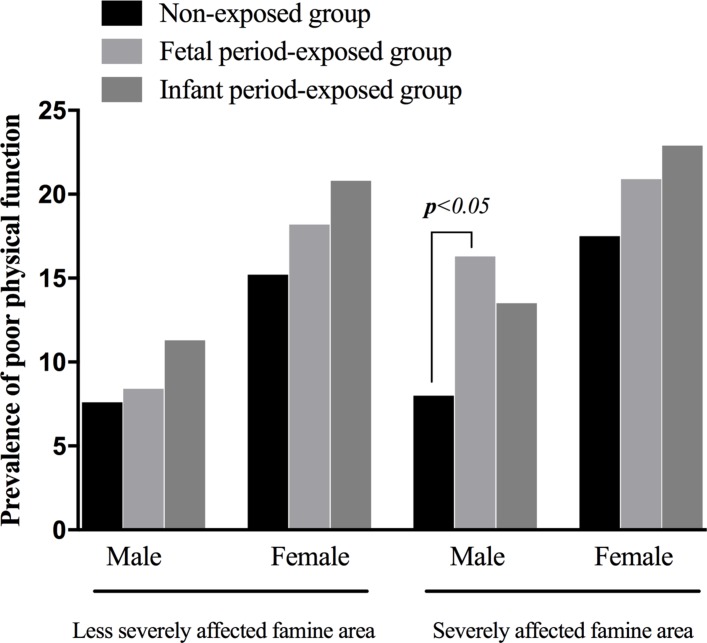

Stratified analysis by gender and severity of famine is displayed in table 4 and figure 2. Among males, when compared with the non-exposed group, exposure at the fetal period (OR 2.43, 95% CI 1.20 to 4.94, p=0.014) significantly increased the prevalence of poor physical function after adjusting for number of chronic diseases, place of residence, smoking, alcohol drinking, marital status, educational level and BMI in severely affected areas. No consistent associations between fetal and infant-exposed groups were found in less seriously affected famine areas (p>0.05). Among females, the adjusted prevalence of poor physical function for two exposed groups suggested no statistically significant differences (p>0.05).

Table 4.

Prevalence of poor physical function in birth groups by gender and severity of the Great Chinese Famine area*

| Prevalence | Crude model | Adjusted model† | |||

| n (%) | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Less severely affected famine area | |||||

| Male | |||||

| Non-exposed group | 26 (7.6) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Fetal period-exposed group | 19 (8.4) | 1.11 (0.60 to 2.06) | 0.732 | 1.12 (0.60 to 2.08) | 0.733 |

| Infant period-exposed group | 53 (11.3) | 1.55 (0.95 to 2.53) | 0.082 | 1.45 (0.88 to 2.38) | 0.144 |

| Female | |||||

| Non-exposed group | 65 (15.2) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Fetal period-exposed group | 48 (18.2) | 1.24 (0.82 to 1.87) | 0.301 | 1.21 (0.80 to 1.84) | 0.366 |

| Infant period-exposed group | 104 (20.8) | 1.47 (1.05 to 2.07) | 0.027 | 1.37 (0.97 to 1.95) | 0.076 |

| Severely affected famine area | |||||

| Male | |||||

| Non-exposed group | 20 (8.0) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Fetal period-exposed group | 17 (16.3) | 2.26 (1.13 to 4.51) | 0.021 | 2.43 (1.20 to 4.94) | 0.014 |

| Infant period-exposed group | 37 (13.5) | 1.80 (1.02 to 3.20) | 0.044 | 1.66 (0.92 to 3.00) | 0.096 |

| Female | |||||

| Non-exposed group | 49 (17.5) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Fetal period-exposed group | 31 (20.9) | 1.25 (0.76 to 2.06) | 0.385 | 1.24 (0.74 to 2.06) | 0.416 |

| Infant period-exposed group | 70 (22.9) | 1.40 (0.93 to 2.10) | 0.107 | 1.34 (0.88 to 2.03) | 0.168 |

*Calculations were made using binary logistic regression analysis. OR represents the ratio of the probability of poor physical function for those who were exposed to famine, compared with those who were not exposed to famine, at 95% CIs.

†Adjusted for number of chronic diseases, place of residence, smoking, alcohol drinking, marital status, educational level and body mass index.

Bold values means P≤0.05, statistical significant level.

Figure 2.

Differences in risk of poor physical function as determined through stratified analysis by gender and severity of famine.

Figure 2 outlines the absolute prevalence of poor physical function. In females, the absolute prevalence of poor physical function is higher than in males. It is observed in both less-severely and severely famine-affected regions. There is no difference at all for females by exposure severity, with subjects exposed at early infanthood showing the highest prevalence of poor physical function, followed by those exposed in utero.

Discussion

This is the first study to suggest a relation between early-life undernutrition and poor physical function using national data from China. It was observed that early-life exposure to the Great Chinese Famine significantly increased the prevalence of poor physical function in midlife. After stratifying by gender and famine, it was found that only fetal exposure to severe famine resulted in considerably increased prevalence of poor physical function in male adults. However, the absolute prevalence of poor physical function in females was higher compared with males. It was observed in both less-severely and severely famine-affected regions. These results suggested that early-life poor nutritional might be a critical factor for physical function development in their midlife.

The sensitivity analyses with a different definition of the outcome (two answers or more of ‘have some difficulties but still can do without help’, ‘needs help’ and”unable to do’) show the same result that the fetal period-exposed (OR 1.34, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.99, p=0.158) and infant period-exposed (OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.07 to 2.06, p=0.019) groups had higher prevalence of poor physical function after adjustment for gender, severity of famine, number of chronic diseases, place of residence, smoking, alcohol drinking, marital status, educational level and BMI compared with the non-exposed group. The definition of the outcome in this study is effective and appropriate.

The current study focused on physical function as the primary outcome and noticed that fetal exposure to the severe Great Chinese Famine significantly increased the prevalence of poor physical function in later life. There are no existing studies on direct assessment of the effect of the Great Chinese Famine exposure in early life on physical function in middle age. However, a recent study explained that a good childhood health status increases the probability of better adult physical function by 14% (95% CI 12% to 17%).29 This implies that early-life stages could be critical periods for physical function in midlife.12 The development of the musculoskeletal system might account for these associations since protein deficiency due to famine may affect growth to optimal size. Nutrient factors affect the development of an optimal muscle mass which partly determines late life muscle mass and function.6

In the present study, it was observed that fetal and infant exposure to the Great Chinese Famine significantly increased the prevalence of high difficulty with using toilet and bathing or showering, while infant exposure significantly increased the prevalence of difficulty with dressing. However, no consistent results were observed for difficulty with eating, getting in or out of bed and control of urination and defecation. The results revealed that the effects of famine exposure on disability in BADL in late life involved using the toilet, dressing, and bathing or showering.

The current study had combined further direct evidence in human beings for the fetal origin hypothesis.30 31 The findings in this investigation are consistent with the results of the Dutch study which reported that exposure to prenatal undernutrition among males was associated with poor physical function in their later life.9 The poor physical function in later life due to fetal stage exposure was more obvious in male than in female survivors. This seemed to be contradictory to the reported effect of severity of famine exposure on the sexes, in which the survival of male children was given preference over that of female children due to the tradition of ‘preferring boys to girls’.32 This was inconsistent with chronic lung diseases.25 One explanation for the sex-specific effects could be the differences in skeletal muscle metabolism: women have high metabolic flexibility in which substrate oxidation is readily adapted by nutrient availability.33 Another explanation is that when muscle mass is affected, the higher relative loss of muscle mass might be seen in men than in women because adult men have greater total lean mass and a lower fat mass than adult women.34 These gender gaps are consistent with the reports of the Dutch famine literature. Besides, the same study cohort described the sex-specific effects of prenatal undernutrition.35

There are some limitations in this study. One major limitation is selection bias which was caused by excess mortality in early life and ‘preferring boys to girls’ attitude common in China. The Great Chinese Famine might have spared the stronger and healthier subjects and gotten rid of the weaker ones. And the loss of girl participants in the exposed group may add to the explanation of the lack of associations between undernutrition and poor physical function in female in the current study. This selection bias may decrease the real effect of famine exposure on physical function,18 which did relatively reduce the trustworthiness of the study. Second, the present study lacks objective indicators of birth characteristics that reflect the severity of famine exposure. Such indicators include birth weight and head circumference which were used in other Chinese famine studies.14 36 Third, due to the fact that the Great Chinese Famine lasted for 3 years (1959–1961), the fetal period-exposed group was separated from the infant-exposed group. Fourth, there was a potential information bias which may result from the subjective nature of the outcome variable. Besides, the time lag within the data collection process, the investigation and analysis of data, and the arriving of results are another limitations that need to be recognised. Notwithstanding these limitations, this study used national data from CHARLS 2015 which had broad representation, and suggested that early-life exposure to the Great Chinese Famine significantly increased the prevalence of poor physical function in middle-age life.

Conclusion

These results indicate that exposure to the Great Chinese famine significantly increased the prevalence of poor physical function in later life, especially fetal exposure in males who had a distinctly higher prevalence of poor physical function in middle-age life.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to the team of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study and all the subjects who participated in the 2015 tracking survey.

Footnotes

Contributors: Contributors TT and LD organised the data and performed statistical analysis, while TT, YL, ZG and JM wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Funding: This study was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (18BRK034) and Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (201607010136).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Medical Ethics Committee of Peking University granted the present study exemption from review. All the participants were informed and consented to the protocol of the study. As the main approach of this study was cross-sectional analysis by collecting data from the CHARLS 2015, there were not many ethical concerns.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The datasets analysed in the current study are available online (http://charls.pku.edu.cn/zh-CN/page/data/2015-charls-wave4).

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. von Bonsdorff MB, Rantanen T, Sipilä S, et al. . Birth size and childhood growth as determinants of physical functioning in older age: the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol 2011;174:1336–44. 10.1093/aje/kwr270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Power C, Kuh D, Morton S. From developmental origins of adult disease to life course research on adult disease and aging: insights from birth cohort studies. Annu Rev Public Health 2013;34:7–28. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roseboom TJ, Painter RC, van Abeelen AF, et al. . Hungry in the womb: what are the consequences? Lessons from the Dutch famine. Maturitas 2011;70:141–5. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wadhwa PD, Buss C, Entringer S, et al. . Developmental origins of health and disease: brief history of the approach and current focus on epigenetic mechanisms. Semin Reprod Med 2009;27:358–68. 10.1055/s-0029-1237424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li J, Na L, Ma H, et al. . Multigenerational effects of parental prenatal exposure to famine on adult offspring cognitive function. Sci Rep 2015;5:13792 10.1038/srep13792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Woo J, Leung JC, Wong SY. Impact of childhood experience of famine on late life health. J Nutr Health Aging 2010;14:91–5. 10.1007/s12603-009-0193-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hirani V, Blyth F, Naganathan V, et al. . Sarcopenia Is Associated With Incident Disability, Institutionalization, and Mortality in Community-Dwelling Older Men: The Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015;16:607–13. 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sayer AA, Robinson SM, Patel HP, et al. . New horizons in the pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of sarcopenia. Age Ageing 2013;42:145–50. 10.1093/ageing/afs191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bleker LS, de Rooij SR, Painter RC, et al. . Prenatal undernutrition and physical function and frailty at the age of 68 years: the Dutch famine birth cohort study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2016;71:1306–14. 10.1093/gerona/glw081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sayer AA, Cooper C, Evans JR, et al. . Are rates of ageing determined in utero? Age Ageing 1998;27:579–83. 10.1093/ageing/27.5.579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Inskip HM, Godfrey KM, Martin HJ, et al. . Size at birth and its relation to muscle strength in young adult women. J Intern Med 2007;262:368–74. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01812.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sayer AA, Poole J, Cox V, et al. . Weight from birth to 53 years: a longitudinal study of the influence on clinical hand osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:1030–3. 10.1002/art.10862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kuh D, Hardy R, Butterworth S, et al. . Developmental origins of midlife physical performance: evidence from a British birth cohort. Am J Epidemiol 2006;164:110–21. 10.1093/aje/kwj193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang Z, Li C, Yang Z, et al. . Fetal and infant exposure to severe Chinese famine increases the risk of adult dyslipidemia: Results from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. BMC Public Health 2017;17:488 10.1186/s12889-017-4421-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Barlogis V, Mahlaoui N, Auquier P, et al. . Physical health conditions and quality of life in adults with primary immunodeficiency diagnosed during childhood: A French Reference Center for PIDs (CEREDIH) study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017;139:1275–81. 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brandt M, Deindl C, Hank K. Tracing the origins of successful aging: the role of childhood conditions and social inequality in explaining later life health. Soc Sci Med 2012;74:1418–25. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. James Banks Z. National Bureau of Economic Research. Cambridge, MA: Social Science Electronic Publishing, 2011:321–39. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang Z, Li C, Yang Z, et al. . Infant exposure to Chinese famine increased the risk of hypertension in adulthood: results from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. BMC Public Health 2016;16:435 10.1186/s12889-016-3122-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rabusic L. [The demographic crisis in China, 1959-1961]. Demografie 1990;32:132–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li W, Yang DT. The great leap forward: anatomy of a central planning disaster. J Polit Econ 2005;113:840–77. 10.1086/430804 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. de Rooij SR, Roseboom TJ. The developmental origins of ageing: study protocol for the Dutch famine birth cohort study on ageing. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003167 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cai Y, Feng W. Famine, social disruption, and involuntary fetal loss: evidence from Chinese survey data. Demography 2005;42:301–22. 10.1353/dem.2005.0010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhao Y, Hu Y, Smith JP, et al. . Cohort profile: the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:61–8. 10.1093/ije/dys203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Luo Z, Mu R, Zhang X. Famine and Overweight in China*. Review of Agricultural Economics 2006;28:296–304. 10.1111/j.1467-9353.2006.00290.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang Z, Zou Z, Yang Z, et al. . Association between exposure to the Chinese famine during infancy and the risk of self-reported chronic lung diseases in adulthood: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e15476:e015476 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the barthel index. Md State Med J 1965;14:61–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, et al. . STudies of illness in the aged. The index of adl: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 1963;185:914–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McNatty KP, Hudson NL, Collins F, et al. . Effects of oestradiol-17 beta, progesterone or bovine follicular fluid on the plasma concentrations of FSH and LH in ovariectomized Booroola ewes which were homozygous carriers or non-carriers of a fecundity gene. J Reprod Fertil 1989;87:573–85. 10.1530/jrf.0.0870573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang Q, Zhang H, Rizzo JA, et al. . The Effect of Childhood Health Status on Adult Health in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Charles MA, Delpierre C, Bréant B. [Developmental origin of health and adult diseases (DOHaD): evolution of a concept over three decades]. Med Sci 2016;32:15–20. 10.1051/medsci/20163201004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Almond D, Currie J. Killing me softly: the fetal origins hypothesis. J Econ Perspect 2011;25:153–72. 10.1257/jep.25.3.153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Coale AJ, Banister J. Five decades of missing females in China. Demography 1994;31:459–79. 10.2307/2061752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lundsgaard AM, Kiens B. Gender differences in skeletal muscle substrate metabolism - molecular mechanisms and insulin sensitivity. Front Endocrinol 2014;5:195 10.3389/fendo.2014.00195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wells JC. Sexual dimorphism of body composition. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;21:415–30. 10.1016/j.beem.2007.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Roseboom TJ, van der Meulen JH, Ravelli AC, et al. . Effects of prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine on adult disease in later life: an overview. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2001;185:93–8. 10.1016/S0303-7207(01)00721-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li Y, Jaddoe VW, Qi L, et al. . Exposure to the Chinese famine in early life and the risk of hypertension in adulthood. J Hypertens 2011;29:1085–92. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328345d969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.