Abstract

Objectives

To report on women’s and families’ expectations and experiences of hospital postnatal care, and also to reflect on women’s satisfaction with hospital postnatal care and to relate their expectations to their actual care experiences.

Design

Systematic review.

Setting

UK.

Participants

Postnatal women.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Women’s and families’ expectations, experiences and satisfaction with hospital postnatal care.

Methods

Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL Plus), Science Citation Index, and Social Sciences Citation Index were searched to identify relevant studies published since 1970. We incorporated findings from qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods studies. Eligible studies were independently screened and quality-assessed using a modified version of the National Institutes of Health Quality Assessment Tool for quantitative studies and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme for qualitative studies. Data were extracted on participants’ characteristics, study period, setting, study objective and study specified outcomes, in addition to the summary of results.

Results

Data were included from 53 studies, of which 28 were quantitative, 19 were qualitative and 6 were mixed-methods studies. The methodological quality of the included studies was mixed, and only three were completely free from bias. Women were generally satisfied with their hospital postnatal care but were critical of staff interaction, the ward environment and infant feeding support. Ethnic minority women were more critical of hospital postnatal care than white women. Although duration of postnatal stay has declined over time, women were generally happy with this aspect of their care. There was limited evidence regarding women’s expectations of postnatal care, families’ experience and social disadvantage.

Conclusion

Women were generally positive about their experiences of hospital postnatal care, but improvements could still be made. Individualised, flexible models of postnatal care should be evaluated and implemented.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42017057913.

Keywords: postnatal care, women’s experience, systematic review

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We searched across 10 different databases.

Quality assessment and data extraction were performed by the authors independently of each other.

Although the aim was to focus on women and babies without complications, most studies did not differentiate by risk.

We initially planned to focus on hospital postnatal care, but some studies did not differentiate between hospital and community postnatal care. These were included for completeness.

Introduction

The key aspects of postnatal care include attention to the physical health of the mother, breastfeeding support, psychological well-being of parents, and education as to what the woman should expect after birth and regarding infant care. Over time there have been a number of changes in postnatal care in the UK, the most evident being a reduction in length of hospital stay.1 A hospital lying-in period of between 8 and 14 days was standard in the 1950s,2 whereas length of postnatal hospital stay for a woman with an uncomplicated vaginal birth in the UK is now often 1–2 days.3 4

A Cochrane review by Brown et al 5 on length of postnatal hospital stay for healthy mothers who gave birth to healthy term babies suggests that early discharge home does not have an adverse effect on maternal health or breastfeeding outcomes when accompanied by a policy of offering women at least one nurse-midwife home visit.5 Most trials included assessments of women’s satisfaction with postnatal care in hospital, and overall, while not statistically significant, women tended to favour a short postnatal stay. A trial by Waldenström et al 6 also reported that, following early discharge, fathers were more involved in early care of the infant. The Cochrane review has not been updated since 2002, and the current state of evidence regarding the impact of length of postnatal hospital stay is unclear, particularly regarding current UK postnatal care policy and practice.

More choices around place of birth means that women may have more variation in location for the immediate postnatal period, for example, a stand-alone birth centre (midwife-led units where the emphasis is on birth without medical intervention in a homely environment) in comparison with a hospital maternity unit. Content of care has also changed. Maternal health observations, feeding support and parental education all remain priorities, but there are limits to what can be achieved during a short stay. In addition, national guidance recommends that women are asked about their emotional well-being at every contact and that they have an initial assessment of needs and individualised plan of care, all of which require time.7 Better Births: Improving outcomes of maternity services in England8 acknowledges that postnatal care needs to be resourced appropriately and that women should have access to their midwife (and where appropriate obstetrician) as required after having had their baby. The Maternity Transformation Programme,9 which gives a structure to the implementation of Better Births, emphasises the importance of kind and personalised care, although postnatal care is not a specific work stream within this.

The need to invest in postnatal care arises from the knowledge that it is the most commonly criticised aspect of care by women, as evidenced in the National Maternity Survey reports and publications arising from secondary analysis of survey data.3 10 11 However, we do not know if this is related to unmet expectations, poor experience of birth or afterwards, or the emotional and physical well-being of the women reporting their experiences.

As hospital postnatal stay has been decreasing in duration and also changing its focus, identifying changes in maternal expectations, experiences and satisfaction may provide important insights as to what aspects of care need to be improved for future services.

Review objectives

This review was conducted to inform a series of policy research projects on postnatal care in the UK. The main aim of this review was to comprehensively report on women’s and families’ expectations and experiences of the immediate postnatal care received in hospitals (including both alongside and free-standing birth centres). The following were the objectives:

To report on women’s satisfaction with hospital/birth centre postnatal care.

To explore how this relates to expectations and experience of care.

To identify gaps in hospital postnatal service provision in the UK.

Methods

This review was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2009 checklist12 and registered with PROSPERO (see Postnatal Care Protocol V.6 in online supplementary file).

bmjopen-2018-022212supp002.pdf (470KB, pdf)

Selection of studies and inclusion criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they involved women with low-risk pregnancies as defined by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 2017 guidelines13 and gave birth in hospitals or birth centres in the UK. If studies contained data relating to both low-risk and high-risk pregnancies, only information relevant to the low-risk group was sought for inclusion. Studies conducted on women with high-risk pregnancies as defined by the NICE 2017 guidelines on antenatal care13 were excluded. We initially planned to exclude studies involving women with various or unknown pregnancy risks, if it was not possible to separate data relating to low-risk women. Studies with findings relating to a woman’s partner were also sought for inclusion. Studies of women of all ages, parity, ethnic background and mode of delivery were eligible for inclusion. Data were also sought regarding contextual information relevant to women’s expectations, satisfaction and experiences of their immediate postnatal care in hospital or birth centre.

We incorporated findings from different research methods: qualitative, quantitative and mixed-method design studies. The quantitative studies of the following designs were eligible for inclusion: randomised controlled trials (RCTs), cross-sectional studies, retrospective or prospective survey-based studies, and observational cohort studies. As the aim was to provide an aggregative summary of what is known about women’s experiences of hospital care, it was important to include all possible data in the synthesis. Qualitative studies included were interview studies, observational studies, focus groups studies and open-ended text from surveys where thematic analysis had been conducted. Surveys where free-text quotes were provided purely for illustrative purposes were excluded.

Reviews, editorials, commentaries and reports were only used to identify additional studies that were not retrieved by the searches. This review focuses on hospital postnatal care; thus, studies on aspects of community postnatal care were not included unless it was impossible to differentiate between them in which case they were included.

Any outcomes relevant to women’s and families’ expectations, experiences and satisfaction with postnatal care received in hospital or birth centres were extracted and are reported in this review.

Search strategy and study selection

The methodological component of the SPIDER (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type)14 search strategy was used. Sets of search terms were developed to cover the following concepts: expectations, experiences and satisfaction with postnatal care in hospital and birth centres in the UK. The MEDLINE search strategy is shown in online supplementary appendix 1.

bmjopen-2018-022212supp001.pdf (470KB, pdf)

The following databases were electronically searched: Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL Plus), Science Citation Index, and Social Sciences Citation Index. We also searched the grey literature in the databanks of British Library EThOS, OpenGrey and ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. All retrieved references were stored in EndNote (V.X8) and screened independently by the review authors.

We restricted our search to English language only and limited by date from 1970. This date was chosen as many changes to postnatal care policies took place subsequently. Review searches were conducted in February 2017. An update search was carried out in February 2019. Authors were contacted as necessary to locate full-text papers.

Assessment of the included studies

For quantitative designs we applied a modified version of the National Institutes of Health Quality Assessment Tool for the observational cohort and cross-sectional studies.15 This tool was used to assess included studies for generalisability and risk of bias based on recruitment, exclusion criteria applied, description of the study population (demographic, location and time period), sample size, response rate and comparability with the wider population. The tool also assessed the adequacy of statistical techniques and adjustment for potential confounders and the reliability and validity of standardised measures. We rated the quality of evidence on each domain as ‘yes’ for low risk of bias, ‘no’ for high risk of bias and ‘unclear’ when no information was provided to support the judgement. The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) risk of bias tool for RCTs16 was implemented to rate the quality of any RCTs identified for inclusion in this review.

For evaluating the risk of bias of qualitative studies, we used the CASP.16 This tool has a checklist of 10 questions which cover the study objectives and rationale, study methods, study design, recruitment strategies, method of data collection, information on ethical approval, and rigour of the method of analysing data and reporting of findings. Each domain is designated ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘unclear’ as above.

For mixed-methods studies, the quantitative and qualitative components were assessed and reported separately, and are thus included in both quantitative and qualitative tables.

All reviewers independently assessed the quality of the included studies, and any discrepancies in quality rating were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction and data analysis

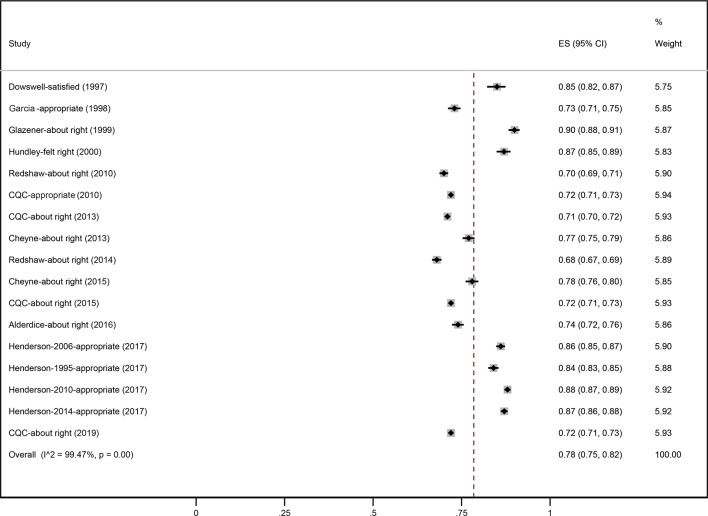

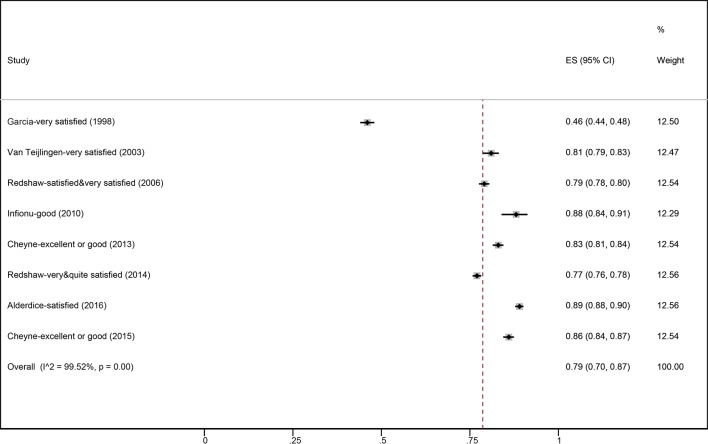

We designed two different data extraction forms, one for the quantitative studies and the second for the qualitative studies. We extracted information relevant to participants’ characteristics, study period, setting, study objective and study specified outcomes, in addition to the summary of results. Data from mixed-method studies were entered in both the qualitative and quantitative forms as appropriate. No authors were contacted to seek additional information. In this review we report findings from qualitative and quantitative studies separately. Meta-analyses were explored for quantitative data; however, heterogeneity was greater than 90% so this was not appropriate. Forest plots have been provided for outcomes where the variables were similar. An aggregative synthesis approach was used to summarise the qualitative data. With this approach the concepts are assumed to be largely well specified17 and the data pooled by providing a descriptive account of the pooled data.

We planned to perform the following subgroup analyses using both quantitative and qualitative data:

By parity.

By mode of delivery.

Ethnicity.

By the duration of postnatal stay: <24 hours, 24<48 hours, 48<72 hours, >72 hours.

Postnatal care received in hospitals in comparison with birth centres.

Comparisons over time: 1970–1989, 1990–2009 and 2010 to present.

Patient and public involvement

The need for a broad review of postnatal care was identified through discussion with our stakeholder groups, which included discussion with our parent, patient and public involvement (PPPI) stakeholders network. Dissemination of findings to stakeholders will be through plain language summaries developed with members of our PPPI stakeholders network.

Results

Results of the search

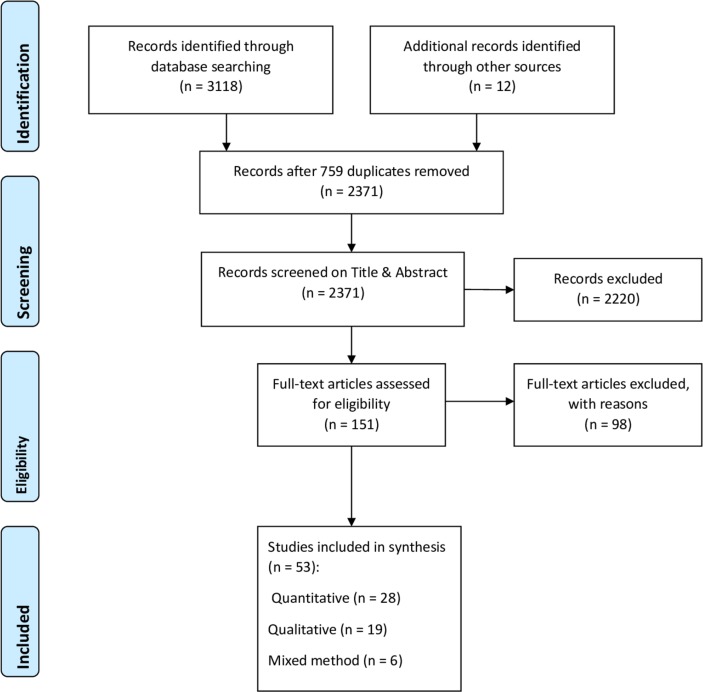

The search strategy retrieved 3118 references, of which 759 were duplicates and were removed. An additional 12 references were identified through hand searching of the reference list of full-text studies. Overall, 2371 titles and abstracts were independently screened by at least two reviewers, resulting in 151 full texts being retrieved. These were assessed for eligibility, and 53 studies are included in this review. Of these, 28 studies were purely quantitative, 19 purely qualitative and 6 used mixed methods (figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Description of included studies

Summaries of the included studies are presented in tables 1 and 2 for quantitative and qualitative studies, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included quantitative studies

| Study | Study objective(s) | Study period and setting | Study design | Participants’ characteristics | Postnatal expectations and experiences | ||||||

| Alderdice et al 18 | What is current practice in Northern Ireland, key areas of concern, do experiences of vulnerable groups differ from others, how do women’s experience compare with those in England? | October–December 2014, Northern Ireland. | Cross-sectional survey posted 3 months after birth to a random sample of women who delivered in the study period. Option of online completion. Eligibility: ages 16+ years, live baby, 2 reminders sent at 2 and 4 weeks. Response rate: 45%, n=2722. |

Mean age: 31 years. Primips: 43.2%. White: 97.9%. Mode of delivery: SVD: 54.6%. Instr: 15.3%. CS: 30.2%. |

LoS:

Mean LoS 2.1 days, primips 2.1, multips 1.9 days. 74% felt LoS about right (primips 71%, multips 74%), 14% too short, 8% too long. Women living alone more likely to stay in longer. No significant difference in LoS in women from deprived areas. Relationship with the staff: Always spoken so that they could understand: 85%. Always treated with respect: 83%. Always treated with kindness: 82%. Always treated as an individual: 79%. Always felt listened to: 77%. Overall satisfaction: 89% satisfied/very satisfied. |

||||||

| Bick et al 19 | To assess whether a quality improvement intervention was associated with improved bf, maternal health and enhanced women’s views of care. | January 2008–June 2009 for preintervention; April–September for postintervention, 1 hospital in England. | Before–after design using continuous quality improvement survey approach. Interventions included longer hospital stay, skin-to-skin contact and bf encouragement, preparation of PN discharge on the PN ward and a revision of PN information booklet. Questionnaire distributed by research MW on PN ward. Eligibility: 16 years or more, live baby, sufficient English. Response rates: preintervention 64% (n= 741); postintervention 63% (n=725). | Mean age: 30.5 years. Parity: 1.66. White European: 81%. Mode of delivery: SVD: 52.6%. Instr: 19.0%. CS: 28.2%. |

LoS:

Preintervention mean 2.2 days, postintervention 2.4 days. Expectations of hospital PN care: Care in hospital better than expected: preintervention 33.7%, postintervention 40.2%. Overall satisfaction with postnatal care: Preintervention 77.4%, postintervention 82.1%. Emotional support needs: No statistically significant differences between groups in women’s views of need for emotional support in hospital; of those women who reported that they did need emotional support in hospital, there was no difference in being able to speak to a midwife. Initiation of bf: Preintervention 86.1%, postintervention 87.4%. |

||||||

| Bowers and Cheyne20 | What is the impact on cost and quality of care of reducing PN stay? | 2013, 2014 Scottish and English National Maternity Surveys (2013). | Secondary analysis of surveys, Nursing and Midwifery Workforce and Workload Planning in Scotland in 2014, including 13 major hospitals with varying mean PN LoS (range 1.4–2.4 days), data from Scottish Government Information Services Division, routine NHS data. Simulation and financial modelling conducted. | Not reported. |

LoS:

Small correlation between LoS and mothers saying that LoS was too short. No correlation between mean LoS and overall satisfaction with PN care. Infant feeding: 40% did not get information needed. 60% did get active support and encouragement with feeding. Relationship with the staff: 30% not treated with kindness and respect. Parents’ education before discharge: 70% of general communication and feeding advice and assistance happened at the time of hospital admission and discharge, only 30% took place during the recovery phase. |

||||||

| Care Quality Commission21 | No objectives specified. | April–August 2010 births, England, 144 Trusts. | Cross-sectional survey posted 3 months after birth. Eligibility: age 16 years or more, live baby, no data about reminders. Response rate: 52%, n=25 229. |

Age:

<25 years: 14%. 25–34 years: 56%. 35+ years: 29%. Primips: 44%. White: 86%. Mode of delivery: SVD: 62%. Instr: 14%. CS: 25%. |

LoS:

<24 hours: 36%. 1–2 days: 35%. 3+ days: 29%. Views on duration of hospital stay: 72% ‘appropriate’. Kindness and understanding: 93% ‘always’. Information and explanations: 53% always given information/explanations, 89% received information needed when leaving hospital. Feeding advice (may include community): 79% ‘always or generally’ received consistent advice, 14% did not receive support. |

||||||

| Care Quality Commission22 (mixed methods) | No objectives specified. | February 2013 births, 137 Trusts, England. | Cross-sectional survey posted 3 months after birth to a random sample of women who delivered in the study period. Eligibility: excluded if woman or baby died, woman aged <16 years, concealed pregnancy, baby taken into care, private maternity care, woman resident outside UK. 2 reminders sent to non-responders. Response rate: 46%, n=>23 000 (exact number not reported). |

Mode of delivery:

SVD: 60%. Instr: 14%. CS: 26%. No other characteristics reported. |

Relationships with staff:

Always treated with kindness and understanding: 66%. Always received information/explanations needed after birth: all women 59%, primips 50%, multips 67%. Definitely given enough information about own recovery: all women 61%, primips 54%, multips 68%. Definitely received information about emotional changes: 56%. LoS: ≤12 hours: 17%. 1–2 days: 37%. 3–4 days: 18%. 5+ days: 9%. Views on LoS: About right: all women 72%, primips 69%, multips 75%. Infant feeding (may include community): Decision on feeding method always respected: 81%. Always consistent advice: 54%, primips 47%, multips 61%. Always active support/encouragement: all women 61%, primips 56%, multips 66%. |

||||||

| Care Quality Commission23 | No objectives specified. | February 2015 births, England, 133 Trusts. | Cross-sectional survey posted 3 months after birth. Eligibility: age 16 years or more, live baby, 2 reminders. Response rate: 40%, n=20 631. |

Age:

<25 years: 9%. 25–34 years: 59%. 35+ years: 32%. Primips: 51%. White: 77%. Mode of delivery: SVD: 59%. Instr: 51%. CS: 25%. |

LoS: 1–2 days 36%. View of LoS: about right 72%, too long primips 19%, multips 15%. Always treated with kindness and understanding: all women 71%, primips 66%, multips 75%. Always able to get help in reasonable time: 81%. Always took account of personal circumstances: 96%. Always given consistent feeding advice: 55% (may include community). |

||||||

| Care Quality Commission47 | No objectives specified. | February–January 2018 births, England, 129 Trusts. | Cross-sectional survey posted 3 months after birth. Eligibility: age 16 years or more, live baby, no data about reminders. Response rate: 37%, n=17 600. |

Age:

<24 years: 7.3%. 25–34 years: 58%. 35+ years: 35%. Primips: 42%. White: 86%. Mode of delivery: SVD: 58%. Instr: 14%. CS: 26%. |

LoS: within 2 days 70% of all women. View of LoS: about right 72%, 11% too short, 17% too long. Always treated with kindness and understanding: all women 77%. Always able to get help in reasonable time: 59%. Initiated bf: 80%. Always given information needed: 66%. Always given support and encouragement about feeding: 63%. Always given consistent feeding advice: 56%. Always respected their decision on feeding: 83%. Partners able to stay: 71%. Hospital room very clean: 70%. |

||||||

| Cheyne et al 25 | No objectives specified. | February–March 2013 birth, Scotland. | Cross-sectional survey posted 3 months after birth to a random sample of women who delivered in 2 weeks in the study period. Option of online completion. Eligibility: excluded if woman or baby died, woman aged <16 years, 2 reminders sent (not stated when). Response rate: 48%, n=2366. |

Age:

<25 years: 15%. 25–34 years: 57%. 35+ years: 28%. Primips: 42%. White: 92%. Mode of delivery: SVD: 56%. Instr: 14%. CS: 30%. |

Views on LoS: 77% ‘about right’, 14% ‘too long’, 10% ‘too short’. Always given explanations needed: 61%. Always treated with kindness and understanding: 67%. Overall quality of care: 83% excellent or good. Bf initiation: 49%. Feeding: consistent advice: always 57%. Feeding: active support and encouragement: always 63%. Feeding decisions respected by staff: always 82%. (Feeding may relate to community as well as hospital.) |

||||||

| Cheyne et al 24 (mixed methods) | No objectives specified. | February–March 2015, Scotland. | Cross-sectional survey posted 3 months after birth to a random sample of women who delivered in the study period. Online option for completion. Eligibility: excluded if woman or baby died, woman aged <16 years, 2 reminders sent (not stated when). Response rate: 41%, n=2036. |

Age:

<25 years: 10%. 25–34 years: 60%. 35+ years: 30%. Primips: 42%. White: 93%. Mode of delivery: SVD: 53%. Instr: 14%. CS: 33%. |

Views of LoS: about right 78%, too short 11%, too long 11%. Bf initiation: 52%. Always received information and explanations needed: 60%. Always treated with kindness and understanding: 70%. Partners accommodated on PN ward: 58%. Infant feeding decision always respected: 82%. Always consistent advice: 57%. Always active support and encouragement: 63%. Overall quality of care: excellent 54%, good 32%. (Feeding may relate to community as well as hospital.) |

||||||

| Cranfield26 | To assess women’s views of support received. | 1981, one centre in the North Herts Maternity Unit, England. | Cross-sectional postal survey sent 3 months after birth to 250 consecutive hospital admissions. Response rate: 76.4%, n=191. No eligibility criteria specified. No mention of reminders. |

Mean age: 26.8 years. Primips: 44%. Mode of delivery: SVD: 76%. Instr: 11%. CS: 13%. |

LoS: 1 day 3%, 2 days 28%, 3–4 days 9%, 5–6 days 9%, 7 days 30%, >7 days 22%. Received adequate help: 84%. Satisfaction with LoS: just right 75%, too long 18%. Bf initiation: 73%. |

||||||

| Dowswell et al 45 | To describe variation in the care process and to explore associations between care process, satisfaction and psychological well-being. | April 1994 births, 6 districts in Yorkshire, England. | Cross-sectional postal survey sent 4–8 weeks after birth to a random selection of women who delivered in the study period. Eligibility: live term births discharged home with mother, reminder sent 2 weeks after initial mailing. Response rate: 72%, n=720. |

No participant characteristics reported. Mode of delivery: SVD: 62.8%. Instr: 33.3%. CS: 3.8%. |

LoS (mean):

SVD: 2.6 days (range 2.0–3.0 days). Instr: 3.6 days. CS: 5.9 days. Women’s satisfaction with the LoS: 85% of women were satisfied with LoS.

|

||||||

| Farquhar et al 27 | To describe the views of women using a team MW scheme providing continuity of caregiver vs traditional care. | December 1994–June 1995, South East England. | Cross-sectional survey posted 1 week after birth to all women residents in health authority who delivered at 1 of 3 hospitals during study period. Women in study group received team MW. Comparison hospitals A and B provided traditional care. Eligibility: excluded women with concealed pregnancy, those with baby placed for adoption. Postal reminders sent after 2 weeks, then phone reminder. Response rates: team MW: 88%, n=1077. Comparison A: 88%, n=272; comparison B: 90% n=133. |

% | |||||||

| Age (years) | Team | Comparison A | Comparison B | % | Team MW | Comparison A | Comparison B | ||||

| <25 | 22 | 16 | 10 | Received fairly/very helpful advice | 94 | 93 | 94 | ||||

| 25–34 | 65 | 71 | 70 | Very satisfied with hospital PN care | 65 | 70 | 69 | ||||

| 35+ | 13 | 12 | 20 | ||||||||

| Primips | 38 | 35 | 27 | ||||||||

| White | 95 | 98 | 98 | ||||||||

| Mode of delivery not reported. | |||||||||||

| Garcia et al

28

(mixed methods) |

No objectives specified. | June–July 1995, England and Wales. | Cross-sectional survey posted 4 months after birth to a random sample of women who delivered in the study period. Eligibility: ages 16+ years, live baby. Response rate: 67%, n=2406. |

Age:

<25 years: 19.9%. 25–34 years: 65.6%. 35+ years: 14.5%. Primips: 42%. White: 92%. Mode of delivery: SVD: 71.9%. Instr: 11.7%. CS: 17.3%. |

LoS:

Had a say/choice in when they went home: 62%. Felt the duration was appropriate: 73%. Treated with respect, kindness and understanding: Always treated with respect: 54%. Always treated with kindness and understanding 51%. Well-supported, confidence and trust in staff: Always had confidence in staff: 59%. Overall satisfaction: 46% very satisfied. Discussion of delivery while on PN ward: Not wanted: 23%. Not been able to: 23%. Yes, at least in part: 53%. Bf: 72% put the baby to the breast at least once. Bf support: Always consistent advice: 31%. Always practical help: 34%. Always active support and encouragement: 38%. Always enough privacy to feed: 49%. |

||||||

| Glazener29 | To describe structures, processes and outcomes of PN care, characteristics, expectations and experiences of women, experience and roles of providers, factors associated with adverse outcome, and areas of unmet need. | May 1990 and May 1991, 2 hospitals in Scotland. | Postal questionnaires sent to a random sample of women immediately after discharge home. Eligibility: all women discharged from PN ward. Reminders sent at 2 and 6 weeks. Response rate: 89%, n=1412 (denominator was all women who initially agreed to take part). |

Mean age: 28.2 years. Primips: 46.7%. Ethnicity not reported. Mode of delivery: SVD: 72.6%. Instr: 13.6%. CS: 13.8%. |

Mean LoS: primips 5.8 days, multips 4.0 days. LoS considered: about right 90%, too short 2%, too long 8%. Considered room unsuitable (would have preferred smaller/single room): 13%. Visiting arrangements: Happy with visiting hours: 89%. Not enough: 9%. Too much: 2%. Staff adjective checklist: 1+ positive adjective: 97%. 1+ negative adjective: 36%. Bf initiation: 58%. Received enough advice about: Dressing baby: 62%. PN exercises: 84%. Own health: 68%. Bf problems at discharge: 16.8%. Received conflicting advice regarding bf: 31%. |

||||||

| Healthcare Commission30 | No objectives specified. | February 2007 births, England. | Cross-sectional survey posted 3 months after birth. Eligibility: age 16 years or more, live baby, no data about reminders. Response rate: 59%, n=26 325. |

Age:

<25 years: 17%. 25–34 years: 56%. 35+ years: 28%. Primips: 49%. White: 87%. Mode of delivery not reported. |

Information and kindness:

42% were not given information or explanations needed. 37% were not treated with kindness and understanding. Infant feeding (may include community): 23% did not receive consistent advice. 22% did not receive practical help. 22% did not receive active support or encouragement. Care after birth: 96% reported their baby had an examination or baby check before leaving hospital. Ward environment: Room/ward very clean: 40%. Toilets/bathroom very clean: 36%. Food: Always offered choice: 70%. Not enough: 28%. Poor overall: 19%. |

||||||

| Henderson and Redshaw1 | To explore change over time in women’s perceptions of maternity care. | 1995–2014, June–July 1995, 1 week March 2006, 2 weeks October–November 2009, 2 weeks January 2014, England. | Secondary analysis of 4 cross-sectional postal maternity surveys 1995, 2006, 2010 and 2014. Random samples selected, questionnaires sent 3 months after birth. Eligibility: aged 16 years or more, live baby. Reminders sent at 2, 4 (and 8 weeks for 2014); 1995 no reminders sent. Response rates: 1995: 67%, n=2406; 2006: 63%, n=2966; 2010: 55%, n=5333; 2014: 48%, n=4571. |

Age (years) | <25 (%) | 25–34 (%) | 35+ (%) | LoS | Women’s view of LoS | Confidence and trust in staff | |

| 1995 | 19.9 | 65.6 | 14.5 | 3 days or more (%) | Too short (%) | Always (%) | |||||

| 2006 | 19.3 | 56.6 | 24.1 | ||||||||

| 2010 | 17.1 | 58.4 | 24.5 | 1995 | 46.7 | 12.6 | 75.2 | ||||

| 2014 | 21.2 | 58.3 | 20.5 | 2006 | 34.8 | 13.1 | 68.9 | ||||

| 2010 | 30.6 | 12 | 68.6 | ||||||||

| Primips | White | 2014 | 28.7 | 12.2 | 68.7 | ||||||

| 1995 | 42.3 | 91.9 | |||||||||

| 2006 | 41 | 87.4 | |||||||||

| 2010 | 50.1 | 85.7 | |||||||||

| 2014 | 49.9 | 83.9 | |||||||||

| SVD | Instr | CS | |||||||||

| 1995 | 71.9 | 11.7 | 17.3 | ||||||||

| 2006 | 64.9 | 12.4 | 22.4 | ||||||||

| 2010 | 62.6 | 12.7 | 24.8 | ||||||||

| 2014 | 58.7 | 14.8 | 26.4 | ||||||||

| Henderson et al 31 | To examine use of services and perceptions of care of women from 7 specific ethnic minority groups. | April–August 2010 births, England, 144 Trusts. | Secondary analysis of Care Quality Commission 2010 data. Eligibility: age 16 years or more, live baby, no data about reminders. Response rate: 52%, n=25 229. |

Only ethnicity reported. White: 80.9%. Mixed: 1.2%. Indian: 2.3%. Pakistani: 2.3%. Bangladeshi: 0.6%. Caribbean: 0.6%. African: 2.6%. Chinese or other: 2.7%. |

LoS >2 days (%) | LoS too long/too short (%) | Information about recovery (%) | ||||

| White | 28.5 | 27.4 | 82 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 32.8 | 25.3 | 80.5 | ||||||||

| Indian | 36.6 | 32.7 | 83.4 | ||||||||

| Pakistani | 33.8 | 34.9 | 79.9 | ||||||||

| Bangladeshi | 32.5 | 29 | 81.3 | ||||||||

| Caribbean | 32.1 | 32 | 80.5 | ||||||||

| African | 38.5 | 28.6 | 87.5 | ||||||||

| Other | 33.1 | 28.7 | 85.4 | ||||||||

| Hicks et al 32 | To compare a Changing Childbirth initiative, including continuity of care, with traditional care. | 2001, England. | RCT comparing intervention with traditional care. Validated questionnaires sent 4–6 weeks after birth, care elements scored out of 5. Eligibility and reminders not reported. Response rate: intervention group n=81 (81%); control group n=92 (92%). |

Mean age:

Intervention group: 28.9 years. Control group: 28.2 years. Mean number of previous births: Intervention group: 2.4. Control group: 2.1. Mode of delivery and ethnicity not reported. |

No significant difference between the two groups on PN ward regarding: Care and sensitivity (scores 2.2 vs 2.2). Explanation/consultation (scores 2.3 vs 2.3). Contact with obstetrician (scores 2.5 vs 2.6). Contact with GP (scores 2.5 vs 2.4). Contact with midwives (scores 2.0 vs 2.0). Not rushed/under pressure (scores 2.1 vs 2.2). Own views taken into account (scores 2.2 vs 2.2). Consistency of information (scores 2.2 vs 2.3). Willingness of MWs to attend to needs (scores 2.2 vs 2.2). |

||||||

| Hirst and Hewison33 (mixed methods) | To compare the quality of hospital PN care for Pakistani and indigenous white women. | July 1995–August 1996, 20 GP practices in 2 districts in Northern NHS region, England. | Prospective comparative survey between districts and between ethnic groups using purposive sampling. No data on reminders or eligibility. Response rate: 83%, n=187. |

No details of participant characteristics reported. White women who were having their first pregnancy were older than Pakistani women. Age range (15–20, 21–30 and 31–41) was similar for each district. |

Expected LoS (hours) | Pakistani | White | ||||

| District A | 60 | 36.5 | |||||||||

| District B | 61.4 | 36 | |||||||||

| LoS: | |||||||||||

| Mean duration 50.7 hours (SD 30.6) for all women. | |||||||||||

| Hundley et al 34 | To determine the extent to which recommendations from policy documents had been adopted. | 10-day period in September 1988, Scotland. | Cross-sectional postal survey distributed by MWs 10 days after birth with Freepost return to study team. Eligibility: all women delivering in Scotland during the study period except if insufficient English, MW considered inappropriate or no longer resident in Scotland. Reminders sent by post at 2 weeks. Response rate: 69%, n=1137 women. |

Mean age: 29.3 years. Primips: 45.4%. White: 98.2%. Mode of delivery not reported. |

LoS:

3–5 days: 48%. 1–2 days: 29%. Views on LoS: 87.2% felt it was right. 3.9% felt it was too long. 8.8% felt it was too short. Choice on when to go home: 77% had a choice. |

||||||

| Ifionu et al

35

(abstract only) |

To assess the quality of maternity care provided in a busy teaching maternity unit. | February–July 2009, Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals. | Questionnaire distributed to women (no further details). Eligibility: live births, baby in ‘good condition’. Response rate: n=302, denominator not reported. |

Participant characteristics not reported. |

Overall postnatal hospital care: 11%–13% rated ‘poor’. Contraception postnatal advice: 65% did not receive any advice. |

||||||

| Ingram et al 36 | To determine whether specific ‘hands-off’ bf technique taught in hospital increases successful bf; to investigate factors associated with bf at 2 and 6 weeks. | October 1996–November 1998, Bristol, England. | Non-randomised, prospective cohort phased intervention study. Eligibility and reminders not reported. Response rate: 84%, n=1171. |

Mean age: 29.5 years. Primips: 58.4%. Mode of delivery and ethnicity not reported. |

Receiving enough support increased bf:

(OR 2.13, CI 1.28 to 3.53). Conflicting advice, enough advice and help, poor advice regarding problems not significantly associated with bf at 2 weeks. |

||||||

| McCourt et al 37 (mixed methods) | 1. Was 1:1 continuity of caregiver preferred by women? 2. Was it associated with any benefit to women? |

1994–1996, London, England. | Prospective study of all women receiving care in Trust over a 1-year period. Intervention and control groups from different areas. Questionnaires sent during pregnancy, and at 2 and 13 weeks postnatally. Eligibility: women resident in area over the period of study, delivered live, term baby. Analysis restricted to 1 hospital. Single reminder. Response rates at 2 weeks: 1:1 group, 59%, n=646; controls 60%, n=603. |

Age not reported. Primips: 35%. White: 42%. Mode of delivery not reported. |

Postnatal care experience comparing 1:1 care with routine care: very satisfied with care: 1:1 50%, routine care 54%. | ||||||

| National Childbirth Trust46 | To explore women’s experience of care and support during the first month after birth. | September 2008–September 2009, UK | Online survey on NCT website. Open to anyone accessing website. 95% NCT members. Response rate: unknown (no denominator), n=1321. |

Primips: 83%. Age (years), primips only: <25: 1%. 25–34: 65%. 35+: 34%. Primips: white 95%. Mode of delivery: Primips: SVD: 48%. Instr: 26%. CS: 26%. Multips: SVD: 81%. Instr/CS: 3%. |

LoS:

Primips (%), Multips (%) < 24 hours: 15, 40 1–2 days: 44, 32 3–4 days: 27, 19 5+ days: 14, 9 Emotional support 24 hours after birth: Primips: 41% received ‘all’, 41% ‘some’, 25% ‘little’ 17%, ‘none’ 17%. Physical support 24 hours after birth: ‘all’ 56%, ‘some’ 24%, ‘little’ 12%, ‘none’ 9%. Information received: 45% received ‘all’, 25% ‘little or none’. Babies’ health information and advice: Primips: ‘all’ 52%, ‘some’ 31%, ‘little’ 11%, ‘none’ 6%. (Data above refer to the first 24 hours. For 15% of primips and 40% of multips, some of this period was postdischarge.) |

||||||

| Raleigh et al 38 | To examine social and ethnic inequalities in women’s experience of maternity care. | February 2007 births, England. | Cross-sectional survey posted 3 months after birth. Eligibility: age 16 years or more, live baby, no data about reminders. Response rate: 59%, n=26 325. |

Age:

<25 years: 17%. 25–34 years: 56%. 35+ years: 28%. Primips: 49%. White: 87%. Mode of delivery not reported. |

Compared with white women, women from ethnic minority stayed in hospital longer after normal delivery, were more likely to initiate bf and for their babies to be checked predischarge. Women from ethnic minorities were more positive about receiving adequate information, being treated with respect and less positive about cleanliness and choice of food. (Numbers varied by ethnic group.) |

||||||

| Redshaw and Heikkila10 | What is current clinical practice, what are key areas of concern, have women’s experience of care changed over the years, are there regional differences in care? | October–November 2009 births, England. | Cross-sectional survey posted 3 months after birth to a random sample of women who delivered in 2 weeks in October–November 2009. Option of online completion. Eligibility: age 16 years or more, live baby. Reminders sent at 2, 4 and 8 weeks. Response rate: 54%, n=5333. |

Age:

<25 years: 17.1%. 25–34 years: 58.4%. 35+ years: 24.5%. Primips: 50.1%. White: 85.7%. Mode of delivery: SVD: 62.6%. Instr: 12.7%. CS: 24.8%. |

Mean LoS:

Primips 2.4 days, multips 1.6 days. Satisfaction with LoS: About right: 70%. Too short: 12%. Too long: 15%. Relationships with staff: Always treated as an individual: 57%. Treated with respect most of the time: 91%. Treated with kindness most of the time: 91%. Always had confidence in staff: 69%. Always spoken to so could understand: 94%. Treated with kindness most of the time: 94%. Infant feeding: Initiation of bf: 63%. |

||||||

| Always… (%) | All women | Primips | Multips | ||||||||

| Consistent advice | 37.5 | 35.2 | 39.8 | ||||||||

| Practical help | 35.6 | 35.2 | 35.7 | ||||||||

| Active support | 39.5 | 38.9 | 40 | ||||||||

| (may include community) | |||||||||||

| Redshaw and Henderson3 | To describe current practice, areas of concern to women, especially experience of vulnerable women, and change over time. | January 2014 births, England. | Cross-sectional survey posted 3 months after birth to a random sample of women who delivered in 2 weeks in the study period. Option of online completion. Eligibility: ages 16+ years, live baby, 3 reminders sent at 2, 4 and 8 weeks. Response rate: 47%, n=4571. |

Age:

<25 years: 21.2%. 25–34 years: 58.3%. 35+ years: 20.5%. Primps: 49.9%. White: 83.9%. Mode of delivery: SVD: 58.7%. Instr: 14.8%. CS: 26.4%. |

Mean LoS: primps 2.2 days, multips 1.8 days. Satisfaction with LoS: about right 68%, too short 12%, too long 15%. Primips 18% too long, multips 13% too long. Relationship with the staff: Always spoken to so could understand: 79%. Always treated with respect (76%) and kindness (75%). Always treated as an individual: 71%. Always felt listened to: 68%. Overall satisfaction: Very/quite satisfied: 77%. Dissatisfied: primips 14%, multips 10%. |

||||||

| Infant feeding: | |||||||||||

| Bf initiation: 87% | |||||||||||

| Always… (%) | All women | Primips | Multips | ||||||||

| Consistent advice | 42.7 | 40.1 | 45.6 | ||||||||

| Practical help | 42.2 | 41.6 | 43 | ||||||||

| Active support | 47.2 | 42.6 | 47.8 | ||||||||

| (may include community) | |||||||||||

| Redshaw et al 11 | From the perspective of women needing maternity care, what is current clinical practice, what are key areas of concern, have women’s experience of care changed over the years? | March 2006 births, England. | Cross-sectional survey posted 3 months after birth to a random sample of women who delivered in 1 week in March 2006. Eligibility: age 16 years or more, live baby, no data about reminders. Response rate: 63%, n=2966. |

Age:

<25 years: 19.3%. 25–34 years: 56.6%. 35+ years: 24.1%. Primips: 41.0%. White: 87.4%. Mode of delivery: SVD: 64.9%. Instr: 12.4%. CS: 22.4%. |

Mean LoS:

Primips SVD: 2.8 days. Multips SVD: 2.0 days. CS all women: 4.1 days. 63% stayed <3 days. Relationship with the staff: Always spoken to so could understand: 91.5%. Treated with respect most of the time: 89.2%. Always treated as individuals: all women 53.1%, primips 50.4%, multips 55.2%. Ward environment: Improvements needed: primips 77%, multips 72%. Critical of privacy 28%, space 22%, temperature 27%, cleanliness 19%, noise 23%. Overall satisfaction: Satisfied/very satisfied: 79.8%. Infant feeding: Bf initiation: 80%. |

||||||

| Always… (%) | All women | ||||||||||

| Consistent advice | 32.7 | ||||||||||

| Practical help | 30.9 | ||||||||||

| Active support | 35.8 | ||||||||||

| (may include community) | |||||||||||

| Scott et al 39 | To examine autonomy, privacy and informed consent in care of PN women. | Study period not reported Scotland (6 university and district hospitals). | Questionnaire packs left with ward staff. Care elements scored out of 5. Eligibility not reported. Response rate: 60%, n=404. |

Women’s characteristics not reported. |

Information women received about LoS: mean score 3.79. Infant feeding information: mean score 4.34. Supporting bowel and bladder function: mean score 3.48. Information related to personal hygiene: mean score 3.56. Breast care information: mean score 3.62. Privacy: mean score 4.33. Staff knocked before entering the room: mean score 4.32. Receiving help with their meals: mean score 4.17. Able to bf in private: mean score 4.63. Confidentiality of women’s treatment: mean score 4.73. Helped to use toilet: mean score 4.86. Helped with hygiene: mean score 4.81. Exposing woman’s body to others: mean score 4.85. |

||||||

| Shields et al 40 (mixed methods) | To compare women’s satisfaction with MW managed care vs shared care over 3 different time periods as part of RCT. | 1993–1994, Glasgow, Scotland. | RCT of MW managed vs shared care. Questionnaires sent during pregnancy and at 7 weeks and 7 months postnatally. Eligibility: booked within 16 weeks, normal, healthy pregnancy, live birth, resident in catchment area. No data on reminders. Response rate at 7 weeks: MW group: 71.9%, n=445; shared care: 63.1%, n=380. |

Mean age at booking*: MW group: 25.8 years. Shared care: 25.5 years. Primips: MW group: 54.7%. Shared care: 53.5%. Mode of delivery (%): MW group Shared care SVD: 73.5 73.7 Instr: 13.6 14.3 CS: 12.9 11.9 |

Satisfaction with staff interaction (mean score on 5-point Likert scale, −2 to +2). | ||||||

| MW group | Shared care | ||||||||||

| Relationships with staff | 1.31 | 0.84 | |||||||||

| Information transfer | 1.2 | 0.7 | |||||||||

| Choices and decisions | 1.13 | 0.07 | |||||||||

| Social support | 1.21 | 0.74 | |||||||||

| Spurgeon et al 41 | To investigate satisfaction with 2 pilot schemes based on Changing Childbirth compared with traditional care. | January 1997–June 1998, large Trust in central England. | Retrospective cohort between-group comparison, two received midwifery-led card (A and B), and the controls (C) received standard obstetric-led care. All delivered in the same hospital. Questionnaires sent 6 weeks after birth. Eligibility: excluded women at high obstetric risk. Reminders sent out until a minimum of 100 questionnaires had been received from each group. Response rates not specified: intervention group, n=215; control group, n=118. |

Mean age:

A. 27.9 years. B. 28.7 years. C. 28.7 years. Average number of previous births: A. 1.7 B. 1.9 C. 2.0 Mode of delivery and ethnicity not reported. |

LoS: no significant difference between the groups (actual LoS not stated). Information and advice: no significant difference between the groups for information, feeding methods, the baby’s health, handling, washing and changing the baby. |

||||||

| van Teijlingen et al 42 | To identify individual or specific concerns with maternity care provision. | September 1998, Scotland (Scottish Birth Study). | Cross-sectional survey distributed by MWs 10 days after birth to all women who delivered in a 10-day period. Eligibility: all women delivering in Scotland during the study period except if insufficient English, MW considered inappropriate or no longer resident in Scotland. Reminders sent by post at 2 weeks. Response rate: 69%, n=1137. |

Age:

15–24 years: 21.4%. 25–34 years: 64.2%. 35+ years: 14.5%. Primps: 45.4%. White: 98.2%. Mode of delivery not reported. |

Overall satisfaction with postnatal care (may include community): Very satisfied: 81%. Satisfied in some ways/dissatisfied: 19%. Primip women’s satisfaction with postnatal care: Very satisfied: 78%. Satisfied in some ways/dissatisfied: 22%. Multip women’s satisfaction with postnatal care: Very satisfied: 84%. Satisfied in some ways/dissatisfied: 16%. |

||||||

| Wardle43 | To examine women’s experience of maternity care. | April–May 1991 births, Staffordshire, England. | Cross-sectional postal survey sent 7–8 weeks after birth to all women who had a hospital birth in study period. No eligibility criteria specified. Reminders sent 2 and 4 weeks after initial mailing. Response rate: 80%, n=639. |

No participant characteristics reported. |

Infant feeding: 58% of babies given breast milk in hospital, >50% supplemented with formula. Women’s health and baby’s care: 30% received conflicting advice from HCPs. 45% wanted to talk more to HCPs about babies’ care and their own health. 21%–27% did not have enough advice about feeding, handling, settling the babies and problems with their own health. Relationship with HCPs: 53% reported midwives were too busy to talk to them. 259 women wrote comments: 81% reported HCPs were helpful and friendly, 29% not receiving enough help or advice, 15% staff too busy, 18% staff attitudes poor and not helpful. Information to women separated from their babies: Most given enough information about baby’s health and progress, 1/4 wanted more, 1/4 wanted to talk to HCP about worries. |

||||||

| Wray44 | To gain the views of women about PN care. | Study period not reported. North West England (2 neighbouring urban locations). | Cross-sectional survey distributed by community MWs on the 10th or 14th day after birth, not clear how survey was returned. Eligibility: women and babies discharged home together, birth weight >2 kg, care by MWs, both mother and baby well, not placed for adoption. No data about reminders. Response rate: 42%, n=452. |

Age:

< 25 years: 18.5%. 25–34 years: 60.9%. 35+ years: 19.7%. Primips: 44.5%. Mode of delivery: SVD: 66%. Instr and CS: 33%. Ethnicity not reported. |

Visiting arrangements: 81% felt visit durations were about right, 19% too short. Flexibility of visiting: 62% right, 38% not flexible Postnatal ward: 86% had enough opportunity to rest. LoS: < 24 hours: 32%. < 2 days: 59%. 3 or 4 days: 26%. 5–10 days: 12%. Infant feeding: 70% intended to bf and of those 75% did bf. Feeding support (may include community): During the day 86% of women felt they were given enough help vs 80% at night. Baby’s care (may include community): 66% shown how to bathe the baby, 34% of women shown how to change nappies and 34% shown top and tail clean, 69% care of cord, 70% had help with baby sleeping position. |

||||||

Bf/bf, breast feeding; CS, caesarean section; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; GP, general practitioner; HCP, healthcare professional; Instr, instrumental delivery; LoS, length of stay; multip, multiparous; MW, midwife; NCT, National Childbirth Trust; NHS, National Health Service; PN, postnatal; primip, primiparous; RCT, randomised controlled trial; SVD, spontaneous vaginal delivery.

*Reported in original trial report.78

Table 2.

Characteristics of included qualitative studies

| Study identification, country | Study aim | Methods | Analysis | Sample characteristics | Themes, findings | |

| Baker et al,48 England | To explore women’s experience of childbirth and the post partum in the context of Changing Childbirth. | Semistructured interviews with 24 women (of 99 recruited for previous study of PN depression), 4–5 years post partum in women’s homes. Interviews recorded and transcribed. | Open and axial coding conducted independently by 3 researchers who then met to discuss interpretation. | Age range | 27–45 | Perception of control. |

| Primips | 9 | Staff attitudes and behaviour. | ||||

| Caucasian | All | Resources. | ||||

| Mode of delivery | Feeding. | |||||

| SVD | 16 | |||||

| Instr | 3 | |||||

| CS | 5 | |||||

| Length of stay | 1–3 days | |||||

| Beake et al,49 England | To explore women’s views and experiences on PN care in hospital and at home. | Indepth, semistructured interviews 8–12 months post partum in women’s homes conducted by researcher. Interviews recorded and transcribed. | Thematic approach similar to that adopted in grounded theory. 2 researchers independently read and coded transcripts. | 22 women, no demographics reported. ‘Diverse’ sample. Over one-third of the sample could not be contacted. | Support: unable to ask for help as women thought MWs too busy. Feeling neglected. Help with feeding the baby. Informational support. Poor facilities. Lack of privacy. Women wanted to go sooner. |

|

| Beake et al,50 England | To explore women’s experience and expectations of hospital PN care. | Semistructured interviews by research MW on PN ward within a few days of birth. | 2 researchers independently read transcripts to identify themes, analytic framework developed. Interviews continued until data saturation reached. | 20 women | Ward environment. | |

| Age range (years) | 23–39 | Attitudes of staff. | ||||

| White Europeans | 18 | Support for bf. | ||||

| Afro-Caribbean | 1 | Unmet information needs. | ||||

| Chinese | 1 | Women’s low expectations of care. | ||||

| Primips | 13 | |||||

| Mode of delivery | ||||||

| SVD | 2 | |||||

| Instr | 3 | |||||

| Emergency CS | 12 | |||||

| Elective CS | 3 | |||||

| Bowes and Domokos,51 Scotland | To explore Pakistani women’s own health concerns, including those related to maternity service provision. | Semistructured interviews, through an interpreter if required, in women’s home or community venue, time point not stated. | Interviews transcriptions indexed and sorted. | 19 Pakistani women and 1 Libyan, characteristics not reported. | Negative staff attitudes. Women reluctant to criticise service. Women appreciated having their babies taken away during night. Hospital food was criticised. |

|

| Care Quality Commission,22 England (mixed methods) | No objectives specified. | Free-text comments in postal questionnaires sent at 3 months post partum in 2013 to a random sample of women. Free-text from 10 007 women but only 8000 analysed. | Thematic analysis. | Whole sample: Mode of delivery |

Spoken to rudely and without consideration. Lack of discussion and explanation following complications. Being left unattended too long. Being neglected. Discharge too soon or held up. Partners not able to stay. Ward too noisy. Lack of privacy. Severely understaffed. MWs bossy and pushy. No support with bf. |

|

| SVD | 60% | |||||

| Instr | 14% | |||||

| CS | 26% | |||||

| No other characteristics reported. No characteristics reported specific to women who wrote free-text comments. | ||||||

| Cheyne et al,24 Scotland (mixed methods) | No objectives specified. | Free-text comments in postal questionnaires sent at 3 months post partum in 2015 to a random sample of women. Free-text from 1244 women. | Thematic analysis using detailed coding and constant comparison. | Whole sample: | Staff were excellent but too busy to have time to help with practical support. Some staff rude and unsupportive. Food was poor. Noisy environment. No proper aftercare or advice for specific conditions. Receiving conflicting advice. Need to build up women’s confidence. Women wanted partner involvement. Lengthy wait for discharge. |

|

| Age <25 years | 10% | |||||

| 25–34 years | 60% | |||||

| 35+ | 30% | |||||

| Primips | 42% | |||||

| White | 93% | |||||

| Mode of delivery | ||||||

| SVD | 53% | |||||

| Instr | 14% | |||||

| CS | 33% | |||||

| Condon et al,52 England | To explore teenagers’ experience of bf promotion and support by health professionals. | Semistructured interviews and focus groups involving 23 teenage mothers up to 2 years post partum, carried out in 2009. Snowball sampling. Interviews recorded and transcribed. Location for interviews not reported. | Inductive thematic analysis using NVivo. | 23 teen mothers aged <19 years, predominantly white (details not reported for PN sample). Mode of delivery and parity not reported. |

Experiences of bf promotion and support at birth. Experiences of continuing bf support. MWs helpful in showing how to position baby but insufficient help with subsequent feeds. |

|

| Cross-Sudworth et al,53 UK | To explore perspectives of first-generation and second-generation women of Pakistani origin and their experiences of maternity care. | Purposive sample. Semistructured interviews (n=8) and focus groups (n=7 in two groups), 3–18 months post partum in community setting, with interpreter as required. | Q methodology using −14 stage process to content analysis. Q set independently assessed by all team members. | UK-born | 10 | Empowerment and high confidence. Isolation and need for professional support. Poor maternity care. Caring maternity services and cultural traditions. Information and support. Importance of MW care. Wanted help bathing the baby. Wanted to stay longer. |

| UK-educated | 12 | |||||

| Age range | 15–21 years | |||||

| Parity | 1–4 | |||||

| Dykes,54 England | To explore the nature of interactions between MWs and bf women in PN ward, 2000–2002. | Participant observation of 97 encounters and 106 focused interviews with 61 women on PN ward in the first few days of birth. Excluded women unable to communicate in English or if baby was in NICU. | Ethnographic thematic analysis. Concurrent data collection and analysis. Basic, organising and global themes developed. Continued until theoretical saturation. | Age range (years) | 17–42 | MWs extremely busy, women aware of pressure on MWs. Bf support mechanical act and time-bound process. Limited continuity of carer. MWs constrained from developing ‘authentic presence’, not based on trusting relationship, led to labelling and stereotyping. Bf as a technically managed activity, teaching of specific techniques in reductionist way, invading body boundaries. Conflicting information received. |

| Primips | 40 | |||||

| White | 56 | |||||

| Asian | 5 | |||||

| Mode of delivery | ||||||

| SVD | 37 | |||||

| Instr | 11 | |||||

| CS | 13 | |||||

| Edwards,55 Scotland | To explore the expectations, knowledge and experiences regarding bf initiation in PN women. | 5 focus groups including 8 PN women within 6 months post partum held at PN clinics. Focus groups recorded and transcribed. | Inductive and deductive thematic analysis. | 8 PN women. All primips. All white. |

Women who had CS upset of not having skin-to-skin contact with the baby. MW taking over, attaching the baby to the breast. Distressing feeding experiences. Feeling of dependency bf, women expected the MW to attach baby to the breast. Lack of skill on the part of the MWs when baby does not attach. Reality better than what women expected. Busy MWs, some short-tempered, seemed uninterested. Feeling left alone. Receiving inconsistent help and support. Peers providing help in hospital with feeding. |

|

| Age 26–30 years | 3 | |||||

| 31–35 | 4 | |||||

| 36–40 | 1 | |||||

| No data on mode of delivery. | ||||||

| Fawcett,56 UK | To examine women’s experiences of hospital-based PN care. | Stories posted by women to the Patient Opinion website relating to hospital PN care, 2013–2015. | Thematic analysis. | 168 stories. No characteristics reported. |

Bf support: primips reported more negative experience. Inclusion of partners. Longer visiting hours. Contrast between good day care, poor night care. Ward environment. Not receiving pain relief. Fast discharge when women wished to be discharged early. Women happy to stay in hospital longer when staff intention was good. Positive comments when continuity of carer. Hospital staff stressed and overworked. Treating women as people not a number. |

|

| Fraser,57 England | To determine how competence in midwifery might be defined from the women’s perspective and aid curriculum development. | Opportunistic sample of 40 women. Semistructured to unstructured interviews at 3 times, including 6–48 hours after birth (n=28), in hospital in 1996 with an interpreter if required. | Thematic analysis using constant comparison aided by Textbase Alpha. | Whole sample: | Not specific to PN hospital care. | |

| Age <20 years | 4 | Characteristics and qualities of caregivers. | ||||

| 20–29 | 22 | Individualised care. | ||||

| 30+ | 15 | Clinical competence of the caregivers. | ||||

| White British | 28 | Developing a trusting relationship with a female MW was perceived as essential to promoting a positive childbirth experience. | ||||

| Primips | 14 | |||||

| Mode of delivery | ||||||

| SVD | 25 | |||||

| Instr | 7 | |||||

| CS | 7 | |||||

| Garcia et al,28 England and Wales (mixed methods) | No objectives specified. | Free-text comments in postal questionnaires sent at 4 months post partum in 1995 to a random sample of women. Free-text from 1042 women. | Thematic analysis. | Whole sample: | Wanting help on PN ward and not getting it. | |

| Age <25 years | 19.90% | Being patronised due to young age. | ||||

| 25–34 years | 65.60% | Poor clinical care and negligence. | ||||

| 35+ years | 14.50% | Feeling rushed and impersonal. | ||||

| Primips | 42% | Staff being rushed, understaffed wards. | ||||

| White | 92% | |||||

| Mode of delivery | ||||||

| SVD | 71.90% | |||||

| Instr | 11.70% | |||||

| CS | 17.30% | |||||

| Hirst and Hewison,33 England (mixed methods) | To compare the quality of hospital PN care for Pakistani and indigenous white women. | Indepth interviews with 139 women in their homes recorded using handwritten notes, 6–8 weeks post partum. Bilingual interviewer if required. | Content analysis. | No details of participant characteristics reported. White women who were having their first pregnancy were older than Pakistani women. Age range (15–20, 21–30 and 31–41) was similar for each district. |

Practical care and guidance. Staff support, sensitivity and communication. Rest. Length of stay. Catering. Socialisation. Psychological well-being. Ward environment. |

|

| Jomeen and Redshaw,58 England | To explore black and minority ethnic women’s experiences of maternity care. | Free-text comments in postal questionnaires sent at 3 months post partum in 2006 to a random sample of women. Free-text from 219 BME women. | Thematic analysis using NVivo. | Black | 25.50% | Feeling cared for. |

| Asian | 57.90% | Expectations of care and policies. | ||||

| Mixed | 11.40% | Rules and organisational pressures. | ||||

| Chinese | 2.70% | Staff attitudes and communication. | ||||

| Other ethnic group | 0.30% | Hospital as a safe place. | ||||

| Age range | 16–40+ | Choices denied. | ||||

| Primips | 39.30% | Sensitive and supportive care. | ||||

| Mode of delivery | Ethnicity and culture stereotyping. | |||||

| SVD | 66.70% | Improving the quality of care. | ||||

| Instr | 10.50% | |||||

| CS | 22.80% | |||||

| Lagan et al,59 Scotland | To report on women’s reflections on their infant feeding expectations and experiences. | Purposive sampling to ensure a range of infant feeding method. 40 semistructured interviews and 7 focus groups (38 women), 4–8 months post partum in non-hospital setting in 2010. | Framework analysis using NVivo. | Age range (years) | 19–41 | Mixed and missing messages. |

| Caucasian | 75 | Conflicting advice. | ||||

| Primips | 49 | Information gaps. | ||||

| Mode of delivery | Unrealistic expectations. | |||||

| SVD | 43 | Pressure to bf. | ||||

| Instr | 12 | Emotional costs. | ||||

| CS | 23 | |||||

| Not clear if themes relate to hospital or community care. | ||||||

| McCourt et al,37 England (mixed methods) | 1. Was 1:1 continuity of caregiver preferred by women? 2. Was it associated with any benefit to women? |

Free text from questionnaires (n not reported); interviews (n=24) either face-to-face or by phone; focus groups at drop-in centres (n and location not reported). | Interviews and focus groups recorded and transcribed. Key emergent themes developed through open coding. Analysis of open text corroborated by independent researcher. | Age not reported. Primips: 35%. White: 42%. Mode of delivery not reported. |

Insensitive responses to requests for support. Staff seeming unavailable, offhand, too busy. Inconsistent advice about bf. Staff undermining women’s self-esteem regarding baby care. Serious lack of morale and motivation among MWs. NB: no quotes presented. |

|

| McFadden et al,61

England |

To explore factors influencing women’s bf experiences following CS. | Semistructured interviews 2–52 days post partum, on ward or NICU, with 10 women who had delivered by CS; 5 had their babies with them on PN ward, 5 had babies in NICU. | Thematic analysis using MaxQda using constant comparison. | Age range: 27–38 years. 6 of 10 primips. 8 of 10 white British. All CS. Age range 21–40 years. Parity 1–6. UK-born: 4. No other characteristics reported. |

Maternal baby separation. Feeling isolated and left to cope alone. Lack of privacy. Underestimated the emotional and physical effects of CS. Lacking confidence in their abilities to bf. Highly dependent on ward staff to initiate bf. Receiving emotional support from staff and families. |

|

| McFadden et al,60

England |

To explore the extent to which cultural context makes a difference to experiences of bf support for Bangladeshi women and to consider the implications for the provision of culturally appropriate care. | Purposive sampling. Indepth interviews and focus groups in community setting with 23 Bangladeshi women in 2008 who had bf within the previous 5 years. Bilingual interviewer if required. | Initial coding was inductive, then codes reorganised into logical framework. | Bf support in hospital. Satisfaction with hospital care. Staff not always sympathetic to women’s need. Ineffective support with bf. Expectation of hands-on support with feeding. Women’s concerns about producing enough milk. Use of formula milk. |

||

| Proctor and Wright,63 England | To gain insights into aspects of maternity care among pregnant and recently delivered mothers. | Postal survey: 313 questionnaires returned, 155 from PN women (6–8 weeks), 117 commented in free text (‘anything in the service that had particularly impressed or bothered them’). | Framework analysis using NUD*IST. | Primips: 54%. No other characteristics reported. |

Continuity of carer. Environment of care. Information. Access. Care and treatment. Relationship with carer. Outcome. Attributes of staff. Choices. Control. |

|

| Proctor,62 England | To identify and compare perceptions of women and MWs concerning women’s beliefs about what constitutes quality in maternity services. | 7 focus groups and interviews, recorded and transcribed, 1994–1997, 2 units in Yorkshire. Interview numbers, PN time point and setting not reported. | Framework analysis using NUD*IST. | 19 PN women, 5 of whom gave birth 2–5 years previously. | Continuity of carer. | |

| Age range | 14–43 years | Environment of care. | ||||

| Parity | 0–3 | Information. | ||||

| Mode of delivery | Access. | |||||

| SVD | 7 | Care and treatment. | ||||

| Emergency CS | 3 | Relationship with carer. | ||||

| Elective CS | 2 | Outcome. | ||||

| Instr | 2 | Attributes of staff. | ||||

| Choices. | ||||||

| Control. | ||||||

| Puthussery et al,64 England | To explore the maternity care experiences and expectations in UK-born ethnic minority women. | Indepth, semistructured interviews with 34 UK-born ethnic minority women at mother’s home or convenient setting 3–12 months post partum. Interviews recorded and transcribed. | Grounded theory approach using NVivo. | Age <30 years | 14 | Sensitive care. |

| Women with adverse physical or mental health were excluded. | 30–39 | 18 | Mismatch between expectations and experiences. Women with additional needs less support than expected. Staff unfriendly and care impersonal. Care environment. PN wards perceived to be poorly equipped and furnished. Issues around privacy, noise, lack of cleanliness and hygiene. |

|||

| 40+ | 2 | |||||

| Primips | 22 | |||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Indian | 11 | |||||

| Pakistani | 4 | |||||

| Bangladeshi | 2 | |||||

| Black African | 10 | |||||

| Black Caribbean | 2 | |||||

| Irish | 5 | |||||

| Ridger,65 England | To explore women’s views of ward PN care. | Purposive sample of 12 women. Non-participant observation and interviews at 2–4 weeks after birth at women’s home or a health facility. | Ethnographic analysis. | Primips | 6 | Busy wards and lack of staff. Task-initiated care. Wanting to have care needs acknowledged. Receiving support. |

| Mode of delivery | ||||||

| SVD | 5 | |||||

| Emergency CS | 2 | |||||

| Elective CS | 3 | |||||

| Instr | 2 | |||||

| Shields et al,40 Scotland (mixed methods) | To compare women’s satisfaction with MW managed care vs shared care over three different time periods as part of RCT. | Free-text comments in questionnaire about what they liked and disliked about their care, 825 women commented on hospital PN care. | Elements of satisfaction grouped and coded independently by 2 researchers. | Mean age at booking*: | Relationships with staff. | |

| MW group: 25.8 years | Information transfer. Social support. Environment. General satisfaction. |

|||||

| Shared care: 25.5 years | ||||||

| Primips: | ||||||

| MW group 54.7% | ||||||

| Shared care 53.5% | ||||||

| Mode of delivery (%): | ||||||

| MW group shared care | ||||||

| SVD: 73.5 73.7 | ||||||

| Instr: 13.6 14.3 | ||||||

| CS: 12.9 11.9 | ||||||

| Taylor,66 England | The experiences of PN ward cot type: side care crib and stand-alone cot in relation to breast feeding. | RCT substudy. Semistructured interviews in women’s home, mostly by phone. | Content analysis using NVivo. | Side care crib, n=29 | Stand-alone cot, n=35 | Birth experiences. Skin-to-skin contact. Delayed bf initiation. Mother–infant separation. Unrealistic bf expectation. Bf experiences on the PN ward. Ward environment. Introduction of formula milk on the PN ward. |

| Primips: 17 | Primips: 16 | |||||

| SVD: 15 | SVD: 10 | |||||

| CS: 2 | CS: 6 | |||||

| Multips: 12 | Multips: 19 | |||||

| SVD: 8 | SVD: 15 | |||||

| CS: 4 | CS: 4 | |||||

*Reported in the original trial report.78

Bf/bf, breast feeding; BME, Black and minority ethnic; CS, caesarean section; Instr, instrumental delivery; multips, multiparous; MW, midwife; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; NUD*IST, Non-numberical Data Infomation Systems and Technology; PN, postnatal; primips, primiparous; RCT, randomised controlled trial; SVD, spontaneous vaginal delivery.

Quantitative studies

There were 34 quantitative studies included in the review,1 3 10 11 18–46 of which 6 were mixed methods.22 24 28 33 37 40

Of these studies, two were RCTs,32 40 one was a non-randomised controlled study,36 a further study was a before–after intervention study,19 and another three33 37 41 were cohort studies. The remaining 27 studies were cross-sectional surveys, 20 of which were national surveys with sample sizes ranging from 113734 to 26 325.30 Survey questions asked women their views on interpersonal and communication aspects of care, infant feeding advice and support received, physical and emotional well-being, length of stay and their view of their length of stay, and overall satisfaction.

The aim of the two included RCTs32 40 was ultimately to compare standard maternity care with midwife-led and managed care. Hicks et al 32 was a pilot study aiming to explore the compatibility of a new maternity care framework with maternity care as envisaged by the Changing Childbirth project. Women were randomised to either an experimental continuity of care group or a traditional care group. Women’s satisfaction with a variety of aspects of care was recorded. These included information received and interaction with healthcare professionals. In the second RCT,40 women were randomised to midwife-managed care or to standard care. However, looking at interventions to improve hospital postnatal care was not the intention of our review. Only data on women’s satisfaction ratings with the interaction with healthcare professionals, information transfer, choices and decisions, and social support were collected.

Of the included studies, 13 were conducted before 2000,26–29 33 34 36 37 40–43 45 and 21 were conducted since then. The majority of the studies were conducted in England, but one was conducted in Northern Ireland18 and seven in Scotland.24 25 29 34 39 40 42

Risk of bias of included studies

The methodological quality of the included studies was overall moderate to low (table 3). The study objectives were clearly prespecified in most of the included studies, but the research question was unclear in 11 studies.3 10 21–25 28 30 35 40 All the studies except one35 involved predefined populations. Of the 33 studies using surveys, 25 had response rates of at least 50%, and of those 8 studies had response rates over 70%,26 27 29 32 33 36 43 45 although in 1 study the denominator was women who had already agreed to participate.29 However, response rates were not reported and not possible to calculate in two studies.35 46 Sample selection was not clearly reported across the included studies, and in the majority of the studies the population had mixed risk status rather than low risk. The generalisability of the study results was also limited by differential response rates with significantly fewer responses from young, single women, those born outside the UK and those residents in deprived areas. Most of the studies reported methods to check the validity and reliability of the surveys. Overall, most of the included studies involved a sample size greater than 100 and used reliable and valid outcomes measures. However, few studies adjusted for potential confounding factors,3 19 31 32 38 46 or used statistical weighting to adjust for differential response rates.20–25 30

Table 3.

Risk of bias in quantitative studies

| Study identification | Was the research question clearly stated? | Was the study population clearly defined? | Was the participation rate of eligible persons at least 50%? | Were all the subjects recruited from the same or similar populations? | Was the sample of participants representative of low-risk women? | Are the measurements (questionnaires) likely to be valid and reliable? | Was the statistical significance assessed? | Are CIs given for the main result? | Was the sample size >100? | Were the exposure measures clearly defined, valid, reliable? | Were key potential confounding variables measured and adjusted for? | Was weighting used? | Can the results be generalised to low-risk women in the UK? |

| Alderdice et al 18 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | N |

| Bick et al 19 | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U |

| Bowers and Cheyne20 | Y | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | U |

| Care Quality Commission21 | U | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Care Quality Commission22 (mixed methods) | U | Y | N | U | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Care Quality Commission23 | U | Y | N | U | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Care Quality Commission 201920 | Y | Y | N | U | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Cheyne et al 25 | U | Y | N | U | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y |

| Cheyne et al 24 (mixed methods) | U | Y | N | U | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N |

| Cranfield26 | Y | Y | Y | N | U | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | U |

| Dowswell et al 45 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y |

| Farquhar et al 27 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y |

| Garcia et al,28 first-class delivery (mixed methods) | U | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y |

| Glazener29 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y |

| Healthcare Commission30 | U | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Henderson and Redshaw1 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y |

| Henderson et al 31 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Hicks et al 32 | |||||||||||||

| Hirst and Hewison33 (mixed methods) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | U |

| Hundley et al 34 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | N |

| Ifionu et al 35 | U | N | U | U | N | U | N | N | Y | N | N | N | U |

| Ingram et al 36 | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y |

| McCourt et al 37 (mixed methods) | Y | Y | Y | U | N | U | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y |

| National Childbirth Trust46 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Raleigh et al 38 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Redshaw and Heikkila10 | U | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y |

| Redshaw and Henderson3 | U | Y | N | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Redshaw et al 11 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y |

| Scott et al 39 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y |

| Spurgeon et al 41 | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | U |

| van Teijlingen et al 42 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y |

| Wardle43 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | Y |

| Wray44 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | N |

N, no; U, unclear; Y, yes.

We assessed the methodological quality of the two RCTs identified for inclusion using the CASP risk of bias tool for RCTs. Both RCTs32 40 clearly stated the focus of their research. Allocation to interventions was assigned randomly and the randomisation methods were reported in both trials. Information regarding whether women were aware or blinded to the intervention status is missing. Both trials reported no significant differences between groups at baseline. However, information relating to whether the groups were treated equally or differently during the study duration was unclear in both trials. Outcomes of interest were aspects of women’s satisfaction with the care they received, and as these were self-reported by the women themselves we are unable to discount the existence of bias in measuring outcomes. With regard to the intervention effect estimates, in Hicks et al,32 women reported a similar level of care satisfaction. In Shield et al,40 the estimated satisfaction with care was significantly higher in the midwife-managed care in comparison with the shared care group in relationships with staff, information transfer, choices and decisions and social support. Data on women’s emotional and physical support were not collected in either trial.

Quantitative results