Abstract

Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has been limited among black and Latino men who have sex with men (MSM), especially in the southern United States. Public health departments and federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) serving predominantly uninsured populations are uniquely positioned to improve access. We evaluated a novel PrEP collaboration between a public health department and an FQHC in North Carolina (NC). In May 2015, a PrEP program was initiated that included no-cost HIV/sexually transmitted infection screening at a public health department, followed by referral to a colocated FQHC for PrEP services. We profiled the PrEP continuum for patients entering the program until February 2018. PrEP initiators and noninitiators were compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and chi-square or Fisher's exact tests for categorical variables. Of 196 patients referred to the FQHC, 60% attended an initial appointment, 43% filled a prescription, 38% persisted in care for >3 months, and 30% reported >90% adherence at follow-up. Among those presenting for initial appointments (n = 117), most were MSM (n = 95, 81%) and black (n = 62, 53%); 21 (18%) were Latinx and 9 (8%) were trans persons. Almost half (n = 55) were uninsured. We found statistically significant differences between PrEP initiators versus noninitiators based on race/ethnicity (p = 0.02), insurance status (p = 0.05), and history of sex work (p = 0.05). In conclusion, this collaborative model of PrEP care was able to reach predominantly black and Latino MSM in the southern United States. Although sustainable, program strategies to improve steps along the PrEP care continuum are vital in this population.

Keywords: HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis, federally qualified health center, public health department, men who have sex with men, PrEP cascade, PrEP continuum

Introduction

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a promising strategy for HIV prevention, but awareness and coverage are low, especially in populations at elevated risk for transmission.1,2 Black and Latino men who have sex with men (MSM) are priority populations given elevated HIV incidence but particularly low PrEP coverage in these groups.3 In addition, the southern United States remains a critical target region for increasing PrEP uptake. Nationwide, the region has the highest proportion of minority persons with a PrEP indication as well as the lowest number of PrEP prescriptions relative to new HIV diagnoses.3,4

The PrEP care continuum has been developed as a framework for exploring the proportion of at-risk patients proceeding to successive stages of care engagement in biomedical HIV prevention. Although prior iterations of this continuum have differed in exact steps, there is a shared goal of identifying where gaps in care exist to target future interventions.5–9 For example, Kelley et al. demonstrated that the largest drop off in the PrEP continuum among black MSM in Atlanta occurred in the step from being eligible (“sexually active”) to being aware/willing, and consequently only 12% were expected to ultimately benefit from PrEP.6

Various PrEP implementation models have been described involving sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinics, including direct PrEP prescribing, passive referral to local PrEP providers, and navigator-assisted linkage to local PrEP providers.10 STI clinics located in public health departments are appealing PrEP access points due to their reach of populations at elevated HIV risk.11,12 However, many STI clinics have limited infrastructure to support the provision of longitudinal PrEP services.13 Federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), however, are an important source of long-term health care for marginalized populations, and can increase access for at-risk individuals in the community.13 Thus, FQHCs may be ideal locations to provide long-term PrEP services for primarily underinsured and uninsured persons, although certain barriers (e.g., high laboratory costs) need to be addressed.

As of 2016, implementation of PrEP services at local health departments in North Carolina (NC) was extremely limited. According to one survey, 4% of health departments were prescribing PrEP and 13% were referring patients externally for PrEP care.14 To leverage the capacity of STI clinics to reach those at elevated HIV and STI risk, as well as the capacity of FQHCs to provide longitudinal care, a partnership program was developed in Durham, NC, to provide a seamless process of referral from the STI clinic to the FQHC for PrEP and primary care services. The goal was to increase PrEP uptake among underserved populations in the county, which has one of the highest HIV incidence rates in the state.15 We conducted a retrospective study to evaluate the PrEP continuum in this collaborative model and compare characteristics of persons who ultimately initiated PrEP with those who did not.

Methods

Referral model

The public health department and FQHC have a long-standing relationship of providing services for the underserved population in the community, and are colocated in a human services facility in Durham, NC. The county has an estimated population of 311,640 in 2017, of which 37.8% are black or African American and 13.7% are Hispanic or Latino in race/ethnicity. Approximately 12.8% of county residents are uninsured.16

The PrEP model was initiated in May 2015 by developing a new collaboration between the public STI clinic and the FQHC primary care clinic through a memorandum of understanding (MOU). An initial meeting of key stakeholders included administrators and health care providers from the health department, FQHC, academic institutions, as well as state public health officials. The MOU defined the referral process, appointments with PrEP providers at the FQHC, and shared costs of PrEP services in the absence of external funding. Individuals who met one of the following criteria were identified as priority candidates for PrEP: MSM who practiced unprotected anal sex, transgender persons, male or female partners to HIV-infected individuals, and sex workers. After PrEP eligible persons underwent initial no-cost STI screening at the STI clinic, health educators facilitated counseling and testing for HIV, hepatitis B and C, provided PrEP education and counseling, and shared information regarding the drug assistance program for uninsured patients. Interested candidates were referred to the FQHC for PrEP initiation, and patients were triaged for the next available appointment; same day or urgent appointments were made as needed for patients felt to be at increased risk. The appointments were made by the patient based on their availability, with assistance from clinical staff. The FQHC is colocated with the STI clinic in the same facility; therefore, transportation assistance with bus passes was provided for initial visits scheduled on different days or return visits.

STI clinic test results were provided to the FQHC through the MOU and patient release of information. The FQHC performed baseline creatinine testing, reviewed medication side effects, initiated PrEP, and conducted follow-up every 3 months for review of adherence and risks as well as repeat HIV/STI testing. Repeat HIV testing with fourth-generation assay was done if more than 1 week elapsed since last HIV test. The FQHC also provided primary care services as well as hormonal gender affirming therapy for transgender patients. Standardized clinic templates were created to ensure adherence to national PrEP guidelines17 and confidential data sharing. At program initiation, medical assistants helped patients navigate a drug assistance program for medications. As work load increased, a case manager was hired to facilitate access to a patient assistance program for both uninsured and insured patients, and to help reschedule patients after missed visits. The FQHC charged a minimum $20 visit fee for lowest tier income, which was subsequently reduced to $5 after the study period. Patients with higher levels of income had higher minimal fees for clinic visits according to FQHC standards. The FQHC was able to absorb laboratory costs (e.g., creatinine), since the health department provided all STI, HIV, and hepatitis testing as already mentioned. Health department and FQHC staff met quarterly to review aggregate data and improve services.

Study design

We conducted a retrospective analysis of steps along the PrEP continuum of care starting with the referral process. Data collection was performed for those presenting to care from May 2015 through February 2018. “Referred” patients included all those who received a referral from the STI clinic to the FQHC for PrEP care; data for these patients were available only in aggregate form. “Initial visit” patients were those who attended the initial FQHC PrEP appointment. For these patients, demographic characteristics were collected through chart abstraction. “Prescription” patients were defined as those who initiated PrEP medication (tenofovir/emtricitabine or TDF/FTC). Initiation of PrEP was determined by chart documentation, with patients confirming they were taking the medication through one of the following ways: (1) a phone call from a certified medical assistant, (2) 1-month nursing visit for laboratories and adherence counseling, or (3) a subsequent provider visit. Patients who presented to their first quarterly follow-up appointment with a PrEP provider were considered to have “3-month persistence.” Finally, “adherence 90% or more” was based on self-reported medication adherence at the follow-up visit, which was routinely collected according to number of missed doses and documented in the medical record. All patients used off-site pharmacies, as TDF/FTC is not currently available at the in-house pharmacy.

Statistical analysis

We assessed the demographic characteristics of individuals receiving PrEP services during the study period. Race/ethnicity categories included non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, Latino/Hispanic, and other. MSM included gay and bisexual men, and transgender included trans male and trans female patients (combined due to small numbers). We compared those who initiated PrEP and those who did not with prescription initiation already defined. For PrEP initiators and noninitiators, comparisons were made using Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables, and chi-square or Fisher's exact tests as indicated for categorical variables. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC). This study was approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board (Pro00086565). A data use agreement with the health department and a data collaboration agreement with the FQHC were approved before data collection.

Results

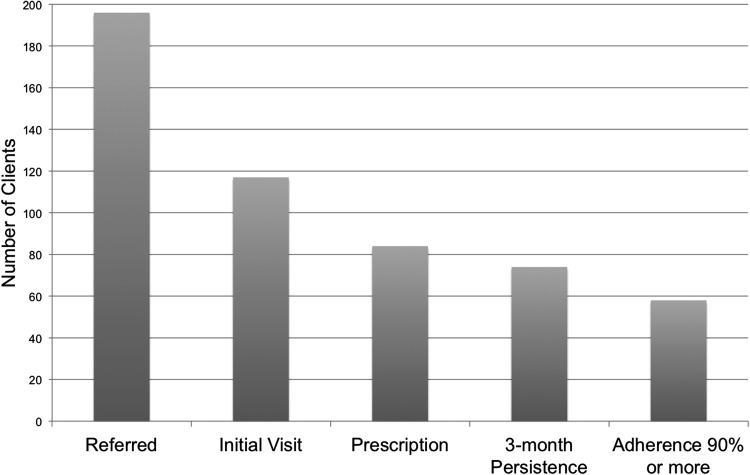

Over the study period, 196 unique patients were referred from the STI clinic to the FQHC primary care clinic for PrEP care. Among these patients who received initial HIV/STI testing, 117 (60%) patients attended their initial PrEP appointment at the FQHC, 84 (43%) filled a PrEP prescription, 74 (38%) persisted in care for at least 3 months, and 58 (30%) reported >90% medication adherence at follow-up (Fig. 1). Among the 117 patients presenting for initial appointments, 62 (53%) were black, 21 (18%) were Latinx, and 22 (19%) were Caucasian (Table 1); most were MSM (n = 95, 81%) and 9 (8%) were transgender. At the time of referral, 49 (42%) had private insurance, 13 (11%) had public insurance, and nearly half (n = 55, 47%) had no health insurance coverage. At baseline, 39 (33%) were diagnosed with an STI. Four patients evaluated for PrEP were subsequently diagnosed with HIV infection, of which one had a positive baseline HIV test and a second discontinued PrEP (due to low adherence and side effects), and later tested positive. The other two patients were repeatedly referred for PrEP, but were found to have converted by the FQHC visit.

FIG. 1.

PrEP continuum for health department/FQHC model. FQHC, federally qualified health center; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics for Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Patients

| Patients keeping initial appointment (n = 117) | PrEP initiators (n = 84) | PrEP noninitiators (n = 33) | pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median | 28 | 27 | 28 | 0.86 |

| Race, n (%) | 0.02 | |||

| Black | 62 (53) | 38 (45) | 24 (73) | |

| White | 22 (19) | 19 (23) | 3 (9) | |

| Latino | 21 (18) | 19 (23) | 2 (6) | |

| Other | 12 (10) | 8 (10) | 4 (12) | |

| Sex/orientation, n (%) | 0.78 | |||

| MSM | 95 (81) | 69 (82) | 26 (79) | |

| Trans | 9 (8) | 7 (8) | 2 (6) | |

| Heterosexual | 13 (11) | 8 (10) | 5 (15) | |

| Insurance status, n (%) | 0.05 | |||

| Private | 49 (42) | 38 (45) | 11 (33) | |

| Public | 13 (11) | 12 (14) | 1 (3) | |

| None | 55 (47) | 34 (40) | 21 (64) | |

| Baseline STI, n (%) | 0.11 | |||

| Yes | 39 (33) | 24 (29) | 15 (45) | |

| No | 73 (62) | 55 (65) | 18 (55) | |

| Not tested | 5 (4) | 5 (6) | 0 (0) | |

| Year of first appointment, n (%) | 0.17 | |||

| 2015 | 23 (20) | 19 (23) | 4 (12) | |

| 2016 | 37 (32) | 29 (35) | 8 (29) | |

| 2017 | 48 (41) | 29 (35) | 19 (58) | |

| 2018 | 9 (8) | 7 (8) | 2 (6) | |

| Sex work, n (%) | 0.05 | |||

| Yes | 6 (5) | 2 (2) | 4 (12) | |

| No | 111 (95) | 82 (98) | 29 (88) | |

| HIV+ partner, n (%) | 0.15 | |||

| Yes | 28 (24) | 17 (20) | 11 (33) | |

| No | 89 (76) | 67 (80) | 22 (67) |

PrEP initiators versus noninitiators.

MSM, men who have sex with men; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Significant values are in bold.

Comparing PrEP initiators with noninitiators, we found statistically significant differences between the groups. PrEP noninitiators had a higher proportion of black patients than did PrEP initiators (73% vs. 45%, p = 0.02). Among PrEP noninitiators, there was also a higher proportion who were uninsured than insured (64% vs. 40%, p = 0.05), and a higher proportion of sex workers (12% vs. 2%, p = 0.05) relative to PrEP initiators (Table 1).

Discussion

Efforts are needed to enhance PrEP access and delivery among diverse patient populations through innovative models of care.18,19 New models for PrEP delivery are especially important for southern states such as North Carolina with high HIV incidence but without Medicaid expansion. Our PrEP model leveraged an existing public health–FQHC partnership, allowing for resource sharing among clinical entities providing care for underserved populations. The STI clinic provided the PrEP portal for persons at high risk for HIV infection, providing no-cost initial assessments and counseling, whereas the colocated FQHC prescribed PrEP and provided other primary care services. Although 40% of patients referred from the STI clinic did not attend their initial PrEP visit at the FQHC, 72% of those who made the appointment subsequently initiated PrEP and 63% persisted at 3 months.

Similar to prior studies,5–7 our PrEP continuum included initiation, retention, and adherence components as well as an initial stage specific to our unique referral process. Profiling the continuum allowed us to determine the gaps in which individuals fell out of the continuum. Based on these gaps, further efforts should be aimed at encouraging same-day PrEP initiation visits, or advocating for increased funding for PrEP initiation services to be provided directly from the STI clinic. Notably, however, 71% of the patients keeping their initial appointment were black or Latino, providing evidence that novel PrEP programs can reach these underserved populations. Nationwide in 2015, dismal proportions of black and Latino persons with PrEP indications were prescribed PrEP—1% and 3%, respectively—highlighting the urgent need to expand access among these racial/ethnic groups.3 The reach of this model is also apparent when examining other characteristics of the population presenting for care: 81% MSM, 8% transgender, and 33% with baseline STI diagnosis.

Our program has attempted to determine reasons why some referred persons did not make their PrEP appointments at the FQHC. Of 28 patients who were identified to have missed visits, 8 persons were successfully contacted to date and provided information through brief telephone questionnaires. Reasons for not making the initial PrEP appointment included preference for PrEP through their primary care providers, cost of medications, forgetting or difficulty in getting to appointments (e.g., due to work and transportation), personal issues, and unsure interest in PrEP. Further efforts are underway to contact additional patients, including those dropping off at distal steps of the continuum, and we are also organizing focus group discussions around discontinuation. A better understanding of why patients are falling out of the continuum is critical to guiding interventions that are adapted to this population.

Our data demonstrate other challenges to PrEP delivery among persons with elevated HIV risk. In comparing those who filled a PrEP prescription with those who did not, we found differences based on race, in that PrEP noninitiators had a higher proportion of black patients than did PrEP initiators; the proportion of Latino patients who initiated PrEP was more favorable. The nominal fee ($20 total/out-of-pocket) for the FQHC visit may have posed a barrier to a population that perceives itself as young, healthy, and at low risk of HIV acquisition.20 Although the clinic visit fee was decreased to $5 for the lowest financial/income tier, this change did not take effect until after the study period. PrEP noninitiators also had higher proportions of uninsured patients and sex workers relative to PrEP initiators. Longitudinally, our PrEP program outcomes are comparable with other southern PrEP cohorts with an overall 3-month retention rate of 59% (among persons presenting for initial PrEP visit).21,22 Reported adherence was excellent and similar to other PrEP studies,5,23 although there is mixed evidence on its reliability as a self-reported measure.24,25

Public health departments and FQHCs take care of the nation's most vulnerable and uninsured, and are uniquely positioned to improve PrEP delivery among those who need it most. However, challenges to PrEP delivery exist, and this combined PrEP model needed to overcome several barriers to implementation. The FQHC's priority is general primary care; therefore, it was important to emphasize that PrEP is part of primary care for individuals at risk for HIV infection, especially those without a medical home. Clinical directors at the health department and the FQHC had to meet with administrators at each agency to address concerns regarding training, personnel utilization, and cost. Sustainable mechanisms for training new providers had to be requested from statewide HIV/AIDS training centers. These provided both in-person and online modules in PrEP prescribing and mentorship to FQHC staff. A major challenge was the cost of repeat STI testing (at multiple sites including oral and rectal specimens) and other laboratory services through the FQHC. PrEP patients were initially intended to have both baseline and follow-up testing at the STI clinic, but patients declined these “double-visits” (i.e., laboratory testing at the health department and medication prescriptions at the FQHC). Thus, additional negotiations between the two entities allowed FQHC providers to order STI tests through the public health laboratory when patients presented for PrEP follow-up.

Health departments in high HIV prevalence areas interested in initiating PrEP programs should reach out to FQHCs regarding HIV prevention. A PrEP collaborative model can be facilitated through meetings with health care providers and stakeholders in the community, and engagement of administrators and clinic staff already dedicated to serving an underserved population. Integrating PrEP within other clinic services and primary care is crucial to the sustainability of the program in FQHCs, which typically do not provide specialized care. Finally, case management staff is necessary to assist uninsured patients with patient assistance coverage and facilitate patient retention-in-care.

This study is limited in that demographic data are not provided for those who were referred for PrEP care from the STI clinic but did not attend for the initial visit. Unfortunately, demographic characteristics were only available for those presenting to the FQHC for care. In addition, the adherence assessment was self-reported, although self-reported drug adherence has been shown in clinical settings to reflect drug concentrations as measured by dried blood spots (DBS).25 DBS may not be feasible in most real-world settings, particularly when resources are constrained. Routinely obtaining prescription data or using pill counts from pill bottles may be more feasible options for assessing adherence, but still require staffing resources. Automated technology-based adherence support tools are promising and undergoing further testing in large clinical trial.26–28 Another limitation of this study is that there was a small number of patients who presented for their initial visit in 2018 and had duration in care <3 months; thus the “3-month persistence” step in the cascade may underestimate the true follow-up rates. Finally, we recognize the need for a single uniform PrEP continuum to allow for standardized comparisons among populations. However, new models of care that are tailored to the community setting—for example, a southern county with limited funds allocated to PrEP delivery—are critically needed, and adaptation of the continuum framework to assess these unique models is, therefore, necessary.

In summary, despite limited funds to support PrEP outside of major metropolitan areas, sustainable programs can be implemented by leveraging and strengthening partnerships between public health departments and FQHCs or other community health centers that can also provide primary care to high-risk populations. Our referral model was able to reach priority populations including persons of color and the uninsured in our community, but additional efforts (such as PrEP navigation, case management, and data sharing) are vital to increasing the proportion of individuals engaged along the PrEP care continuum.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by NIH/NIAID under Award Number K23AI137121 to M.E.C. A.L.R is currently funded through NIH/NIAID T32AI007001.

Author Disclosure Statement

M.E.C. receives royalties from UpToDate. A.C.S. receives royalties from UpToDate and has a Gilead FOCUS grant for HIV/HCV testing and linkage to care. All other authors have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1. Bazzi AR, Biancarelli DL, Childs E, et al. . Limited knowledge and mixed interest in pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among people who inject drugs. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2018;32:529–537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Koren DE, Nichols JS, Simoncini GM. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis and women: Survey of the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs in an urban obstetrics/gynecology clinic. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2018;32:490–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smith DK, Van Handel M, Grey J. Estimates of adults with indications for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis by jurisdiction, transmission risk group, and race/ethnicity, United States, 2015. Ann Epidemiol 2018;28:850.e9–857.e9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Siegler AJ, Mouhanna F, Giler RM, et al. . The prevalence of pre-exposure prophylaxis use and the pre-exposure prophylaxis-to-need ratio in the fourth quarter of 2017, United States. Ann Epidemiol 2018;28:841–849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Lassiter JM, Whitfield THF, Starks TJ, Grov C. Uptake of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in a national cohort of gay and bisexual men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;74:285–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kelley CF, Kahle E, Siegler A, et al. . Applying a PrEP continuum of care for men who have sex with men in Atlanta, Georgia. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61:1590–1597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hojilla JC, Vlahov D, Crouch P-C, Dawson-Rose C, Freeborn K, Carrico A. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) uptake and retention among men who have sex with men in a community-based sexual health clinic. AIDS Behav 2018;22:1096–1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chan PA, Glynn TR, Oldenburg CE, et al. . Implementation of preexposure prophylaxis for human immunodeficiency virus prevention among men who have sex with men at a New England sexually transmitted diseases clinic. Sex Transm Dis 2016;43:717–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nunn AS, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Oldenburg CE, et al. . Defining the HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis care continuum. AIDS Lond Engl 2017;31:731–734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hoover KW, Ham DC, Peters PJ, Smith DK, Bernstein KT. Human Immunodeficiency virus prevention with preexposure prophylaxis in sexually transmitted disease clinics. Sex Transm Dis 2016;43:277–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu AY, Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, et al. . Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection integrated with municipal- and community-based sexual health services. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:75–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hoover KW, Parsell BW, Leichliter JS, et al. . Continuing need for sexually transmitted disease clinics after the affordable care act. Am J Public Health 2015;105(Suppl 5):S690–S695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mayer KH, Chan PA R P.atel R, Flash CA, Krakower DS. Evolving models and ongoing challenges for HIV preexposure prophylaxis implementation in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018;77:119–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang HL, Rhea SK, Hurt CB, et al. . HIV preexposure prophylaxis implementation at local health departments: A statewide assessment of activities and barriers. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018;77:72–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rosenberg ES, Grey JA, Sanchez TH, Sullivan PS. Rates of prevalent HIV infection, prevalent diagnoses, and new diagnoses among men who have sex with men in US states, metropolitan statistical areas, and counties, 2012–2013. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2016;2:e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Durham County, North Carolina. Available at: www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/durhamcountynorthcarolina/PST045217 (Last accessed February7, 2019)

- 17. US Public Health Service. Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States—2017 Update. A Clinical Practice Guideline. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2017.pdf (Last accessed March2018)

- 18. Elopre L, Kudroff K, Westfall AO, Overton ET, Mugavero MJ. The right people, right places, and right practices: Disparities in PrEP access among African American men, women and MSM in the Deep South. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;74:56–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aaron E, Blum C, Seidman D, et al. . Optimizing delivery of HIV preexposure prophylaxis for women in the United States. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2018;32:16–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Elopre L, McDavid C, Brown A, Shurbaji S, Mugavero MJ, Turan JM. Perceptions of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among young, black men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2018;32:511–518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chan PA, Mena L, Patel R, et al. . Retention in care outcomes for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation programmes among men who have sex with men in three US cities. J Int AIDS Soc 2016;19:20903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rolle C-P, Onwubiko U, Jo J, Sheth A, Kelley CF, Holland DP. PrEP implementation and persistence in a county health department in Atlanta, GA. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Boston, MA, March2018 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koss CA, Hosek SG, Bacchetti P, et al. . Comparison of measures of adherence to human immunodeficiency virus preexposure prophylaxis among adolescent and young men who have sex with men in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2018;66:213–219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Abaasa A, Hendrix C, Gandhi M, et al. . Utility of different adherence measures for PrEP: Patterns and incremental value. AIDS Behav 2018;22:1165–1173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Montgomery MC, Oldenburg CE, Nunn AS, et al. . Adherence to pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in a clinical setting. PloS One 2016;11:e0157742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mitchell JT, LeGrand S, Hightow-Weidman LB, et al. . Smartphone-based contingency management intervention to improve pre-exposure prophylaxis adherence: Pilot trial. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2018;6:e10456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fuchs JD, Stojanovski K, Vittinghoff E, et al. . A mobile health strategy to support adherence to antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2018;32:104–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. LeGrand S, Knudtson K, Benkeser D, et al. . Testing the efficacy of a social networking gamification app to improve pre-exposure prophylaxis adherence (P3: Prepared, Protected, emPowered): Protocol for a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Protoc 2018;7:e10448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]