Abstract

Endometriosis is a chronic, painful disease without a cure. Due largely to chronic pain, endometriosis can lead to significant physical, mental, relationship, and financial burdens. Within the conventional single provider model of care—in which the patient is primarily taken care of by her physician and complementary strategies based on psychology, nutrition, pain medicine, pelvic physical therapy, and so on may not be readily available in a coordinated manner—most women with endometriosis live with unresolved pain and the consequences of that pain. We therefore propose that there is an urgent need to search for alternative models of care. In the current paper, we discuss our experiences with an model of care in which we adopt a long-term, patient-focused, and multidisciplinary chronic care model for women with endometriosis. Our objective is to improve long-term clinical outcomes for women with endometriosis. For geographical areas and healthcare systems in which it is feasible, we propose consideration of this multidisciplinary model of care as an alternative to the single provider model and offer guidance for those considering establishment of such a program. We also initiate a conversation about which clinical outcomes pertaining to endometriosis are important and should be tracked to assess the efficacy and value of multidisciplinary and other endometriosis healthcare models.

Keywords: endometriosis, multidisciplinary, chronic care model, multimodal, quality of life, health services

Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic, estrogen-dependent, and inflammatory disease of unknown etiology and without a cure; it is defined by the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus. It affects 6–10% of reproductive-aged women,1 leading to a range of chronic pain symptoms including, but not limited to, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, non-menstrual pelvic pain, dyschezia, and bladder and abdominal pain(Ballard et al 2008).2 The range of symptoms can be confusing for the patient and care provider, often leading to an unfortunate 6–12 year delay in diagnosis.3–5 Contemporary management of endometriosis includes medical strategies aimed at suppressing estrogen or menses and surgical methods aimed at excising or ablating the lesions. Endometriosis-related pain affects the ability to function physically and mentally, leading to social withdrawal, psychological symptoms such as depression, and broader reductions in quality of life (QoL).

In the current single-provider model of care for women with pelvic pain due to endometriosis, the patient is almost exclusively cared for by her physician, usually a gynecologist. If the physician is a primary care specialist such as family practitioner, internist, or pediatrician, then the patient will likely be referred to a gynecologist for surgical diagnosis and further management. This model of care for a complex chronic disease without a cure can pose challenges for both patients and care providers. With limited complementary strategies, such as mental health, acupuncture, nutrition, and pelvic physical therapy expertise to comprehensively address the patient’s pain and its consequences, optimal care may not be achieved. Indeed, 70% of women with endometriosis chronically experience unresolved pain, with 57% reporting dysmenorrhea, 47% reporting dyspareunia, and 60% reporting non-menstrual pelvic pain.6,7 These unacceptable levels of unresolved pain exist despite substantial healthcare utilization, with 46% of women reporting having received at least three medical treatments and 42% having undergone at least three surgeries to excise or ablate their endometriosis.8 Furthermore, 49% of women using narcotics for pain management continue taking narcotics one year after laparoscopy.9 Ultimately, the direct healthcare cost of endometriosis is similar to that of other chronic diseases including migraine, asthma, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and Crohn’s disease.10,11 Thus, there is an urgent need to rethink endometriosis care in order to provide a more comprehensive, patient-focused approach with long-term goals.

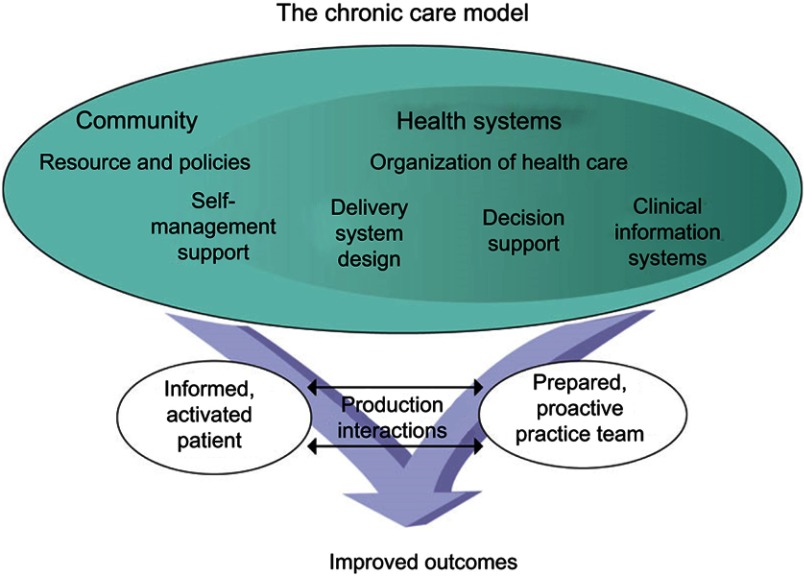

Endometriosis is a unique chronic disease in that it causes significant morbidity, is without a cure yet, and is primarily treated by gynecologists. Gynecology is a surgical specialty, and it is common in many situations for gynecology surgeons to generally have a shorter-term outlook than, for instance, primary care physicians. Thus, in order to provide prolonged, patient-focused care to women with endometriosis, a shift in thinking to a more long-term outlook is imperative. The Chronic Care Model (CCM),12 provides a framework (Figure 1) for improving long-term care and health of individuals with chronic disease in primary care, which may provide a suitable model for the care of women with endometriosis.

Figure 1.

The chronic care model.

Note: Reproduced with permission from Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract. 1998;1(1):2–4.12

Transforming healthcare delivery system design is paramount in the CCM and may be the vital framework for improving endometriosis care. As highlighted above, the current system’s inability to adequately address endometriosis pain symptoms often results in the emergence of broader functional sequela and psychological impact. The ability to address these broader impacts is crucial and certainly requires a more comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach to care. Although caring for chronic conditions in specialty clinics is less common, similar transformations have been described in other conditions such as HIV care13,14 and HCV care,15 in which comprehensive and multidisciplinary approaches integrating mental health services with specialty care have been effective for improving care.

Herein, we report our experience with the application of the CCM to endometriosis care in our center and provide insight into patient referrals to other specialties along with preliminary patient feedback. We hope that this article will help in developing multidisciplinary care models for endometriosis and stimulate discussion regarding appropriate clinical outcomes that should be used as measures of quality in such models of care.

Main text

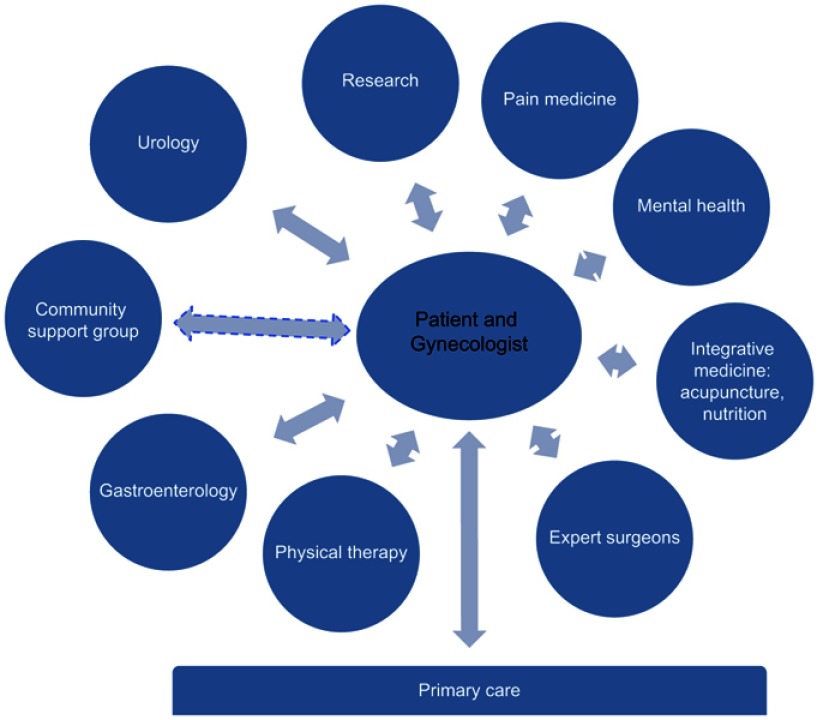

In 2010, our motivators for establishing a multidisciplinary endometriosis program were the following beliefs: 1) optimal long-term management of endometriosis patients requires providers with complementary expertise who communicate effectively with each other; 2) this model would allow for a comprehensive, long-term, and patient-focused approach; and 3) the model would facilitate and stimulate research and education. A team of healthcare providers was recruited from relevant specialties including pain medicine, psychology, gastroenterology, urology, expert surgeons, pelvic physical therapy, and integrative medicine incorporating acupuncture, nutrition, and mind-body programs (Figure 2). Their roles are as follows.

Figure 2.

The University of California, San Diego Center for Endometriosis Research and Treatment model for multidisciplinary endometriosis care. The dashed line for community support group indicates that although this is an important component of the chronic care model, it is yet an unmet need in UC San Diego Center for Endometriosis Research and Treatment. Specialties with shorter arrows generally receive more frequent referrals than the ones with longer ones.

Gynecologist

Central to coordinating care and in accordance with the CCM is the patient-gynecologist interaction. Together, they decide if referrals to other specialties should be initiated. An important role for the primary gynecologist and their team is to educate the patient and to encourage self-education so that the patient may be better able to make more informed decisions about her care.

A new patient visit provides an opportunity to understand the patient’s journey and assess specific needs, preferences, and clinical condition, thus facilitating the development of a personalized and comprehensive treatment plan that is jointly formulated. Subsequent visits are useful to assess the impact of any treatment/referrals on pain, QoL, and general well-being as well as for collaboratively formulating the next steps.

Integrative medicine

Many women choose to try complementary therapies for health benefits. Often, patients may be skeptical of conventional medical or surgical therapies and would rather try, as sole interventions or in combination with more conventional treatments, options such as acupuncture, nutrition and mind-body programs. These interventions, which are included in our program, and are targeted at decreasing inflammation, may reduce pain or make conventional therapies more tolerable. Many patients find that these options improve their pain and QoL. In our program, integrative medicine has received the largest proportion of our referrals at 43%.

Mental health

Anyone experiencing chronic pain is vulnerable to psychological consequences. Hence, it is understandable that psychological disturbances such as depression are common in women with endometriosis.16 Having a psychologist embedded in the clinic can be invaluable, and for some patients, it substantially facilitates their overall psychological wellbeing. Where necessary, specialist psychiatric help may also be beneficial to help with detoxification for individuals accustomed to chronic opioid use. Of the referrals at our center, 12% are to our mental health professionals.

Pain medicine

Management in collaboration with pain medicine can be a crucial factor for optimizing outcomes for endometriosis patients. For example, even though a woman may have been diagnosed with endometriosis, it does not necessarily mean that her pain is due to endometriosis, and so, being vigilant regarding alternative, confounding diagnoses is important. In addition, there are times when a woman’s endometriosis pain may not be responsive to standard gynecologic interventions. In these circumstances, a pain medicine consultation is valuable in addressing pain with strategies such as nerve blocks and non-hormonal therapies including gabapentin, that are specialized and different from those of the typical gynecologist. Involvement of a pain medicine specialist is a critical component in our program and receives 12% of our referrals.

Expert surgeons

Complex surgeries are sometimes recommended for women with endometriosis. Although most laparoscopies are conducted by the central gynecologist, some may require subspecialist expertise and collaboration. For example, a colorectal surgeon’s assistance may be required to optimally address deep infiltrating recto-vaginal disease. Accordingly, we recommend partnering with experienced general surgeons, gynecologic oncologists, and colorectal surgeons.

Physical therapy

Patients with dyspareunia and pelvic floor dysfunction are referred for pelvic physical therapy.17 These specialists are often able to improve dyspareunia and other types of pelvic pain through internal manipulation of pelvic floor muscles and ligaments.

Gastroenterology

Women with endometriosis may have various gastrointestinal symptoms such as bloating, dyschezia, and constipation. Many show improvement with appropriate endometriosis medications and thus do not commonly need referral. Gastrointestinal bleeding may be due to endometriosis in the bowel, and in our program, this or other severe gastrointestinal symptoms trigger a gastroenterology referral to diagnose the cause, which may or may not be endometriosis. Gastroenterology has received 2% of our referrals.

Urology

Many women with bladder pain have interstitial cystitis or other chronic bladder pain. As with gastrointestinal symptoms, many bladder symptoms are also resolved with appropriate endometriosis medical treatment, and therefore, only a modest number of patients have been referred to urology. A few patients with ureteric stenosis due to peritoneal scarring have required collaborative surgery with gynecologists, oncologists, and urologists.

Primary care

Although not specifically a part of the Center for Endometriosis Research and Treatment (CERT) at UC San Diego Health, our patients are encouraged to have a primary care practitioner for more general healthcare concerns and opioid pain management consideration, if necessary. The risks of overdosing and addiction to opioids should be reduced by obtaining them from a sole primary care provider. The primary care specialist can also provide an opportunity for the early detection and management of endometriosis-related co-morbidities, such as rheumatologic, cardiovascular, and other inflammation-related diseases that are apparently more common in women with endometriosis.

Research

Women with endometriosis view participation in research as altruistic.18 Stimulating and facilitating “bedside to bench and back” translational research productivity in a meaningful manner that addresses the needs of women with endometriosis are major benefits of CERT. Moreover, a research team composed of clinicians, basic scientists, and students enhances training and facilitates high-priority research.19

Community-support group

The CCM, as described by Wagner,12 incorporates self-help and community support groups. However, such well-intended endeavors do not always work well, and at present, we do not have an active support group in CERT.

Other

The comprehensive care of women with endometriosis clearly requires more than simply the core elements depicted in Figure 2. We rely heavily on our nursing staff to provide support and education as well as to help co-ordinate care and oversee patient experience. Reproductive endocrinologists can be critical in addressing fertility needs, and on occasion, imaging specialists can be important in helping with differential diagnoses.

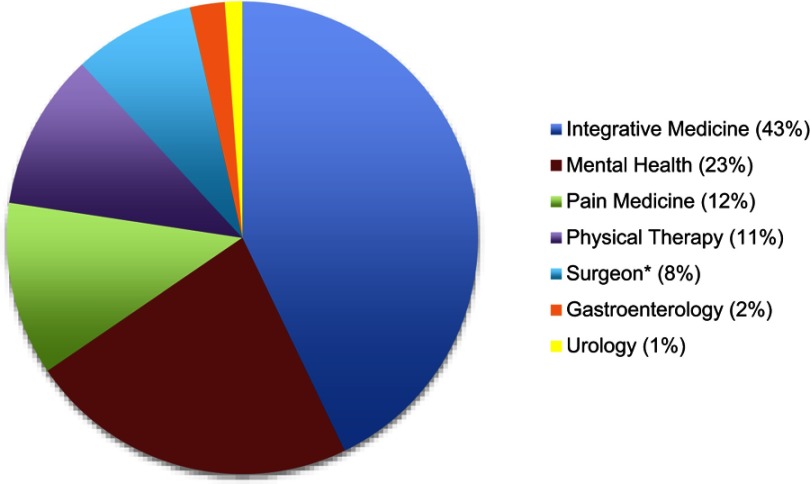

Figure 3 depicts the relative frequency of referrals from the core patient-gynecologist team to the various components of CERT. These data reflect the needs and wishes of the patient population served. It is worth noting that pain medicine only generates 12% of the referrals. In contrast, integrative medicine and mental health together account for 66% of the referrals. Neither of these are currently standard components of endometriosis care. Clearly, a prospective, in-depth evaluation of the value of the various components of the multidisciplinary program is required.

Figure 3.

Relative frequency of referrals from the central gynecologist and patient interactions to other components of the UC San Diego Center for Endometriosis Research and Treatment. *As the central gynecologist is a reproductive endocrinologist, the surgeon referrals typically reflect those for hysterectomy and not laparoscopy.

To obtain some preliminary indication of patient perceptions pertaining to multidisciplinary endometriosis care, data from an internal quality assurance project in which our nursing/patient experience team collected data from 28 recent patients was used. In response to the statement “In my opinion, having the availability of a multidisciplinary endometriosis program to more completely help women with endometriosis is:” 18 (71%) responded “very helpful,” 5 (18%) responded “somewhat helpful,” 3 (14%) responded “very little helpful,” and 2 (7%) reported “unhelpful.”

Conclusions

Endometriosis is a complex, chronic disease that poses challenges for both patients and care providers. Despite substantial healthcare resources being directed at endometriosis care, clinical outcomes remain suboptimal. Indeed women with endometriosis are frequently dissatisfied with their care and seek alternative strategies to manage their symptoms20 that they may or may not discuss with their physician. It is thus imperative to contemplate alternative healthcare models for this disease. Our insights from establishing a multidisciplinary endometriosis clinic demonstrate that the CCM can be applied to the care of women with endometriosis and that establishment of a long-term, patient-focused, comprehensive, and multidisciplinary program is feasible.

Our experiences with the establishment of a long-term, patient-focused, comprehensive, and multidisciplinary CCM for women with endometriosis expand on prior suggestions for multidisciplinary care of endometriosis.21–23 In rethinking endometriosis care and helping to shape the recommended outcome measures, we would like to promote conversation by suggesting the monitoring of pain, QoL, frequency of emergency room visits, and rate of opioid use as basic and minimum clinical parameters of endometriosis care models that are important to track. Furthermore, given the chronic nature of endometriosis-related morbidity and comorbidity, we also propose that such outcomes be tracked not over short periods of time, such as 6 months or less, but over a minimum of 2 years. Additional assessments of healthcare delivery costs would help define parameters for value. We propose that for improved long-term clinical outcomes, a multidisciplinary approach, which includes pain medicine, psychology, pelvic physical therapy, nutrition, and other disciplines, will be helpful. We anticipate that the foregoing discussion will stimulate conversation about the care of women with endometriosis with a view to encouraging the development of widely accepted international parameters for assessing the clinical and quality outcomes of different endometriosis care models.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364(9447):1789–1799. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17403-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballard KD, Seaman HE, De Vries CS, Wright JT. Can symptomatology help in the diagnosis of endometriosis? Findings from a national case-control study - Part 1. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;115(11):1382–1391. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01878.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballweg ML. Impact of endometriosis on women’s health: comparative historical data show that the earlier the onset, the more severe the disease. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;18(2):201–218. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2004.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hadfield R, Mardon H, Barlow D, Kennedy S. Delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis: a survey of women from the USA and the UK. Hum Reprod. 1996;11(4):878–880. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Staal AHJ, van der Zanden M, Nap AW. Diagnostic delay of endometriosis in the Netherlands. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2016;81(4):321–324. doi: 10.1159/000441911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Graaff A, D’hooghe TM, Dunselman GAJ, et al. The significant effect of endometriosis on physical, mental and social wellbeing: results from an international cross-sectional survey. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(10):2677–2685. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fourquet J, Gao X, Zavala D, et al. Patients’ report on how endometriosis affects health, work, and daily life. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(7):2424–2428. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinaii N, Cleary SD, Younes N, Ballweg ML, Stratton P. Treatment utilization for endometriosis symptoms: a cross-sectional survey study of lifetime experience. Fertil Steril. 2007;87(6):1277–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soliman A, Du EX, Yang H, Wu EQ, Haley JC. Retreatment rates among endometriosis patients undergoing hysterectomy or laparoscopy. J Womens Health. 2017;26(6):644–654. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2016.6043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simoens S, Dunselman G, Dirksen C, et al. The burden of endometriosis: costs and quality of life of women with endometriosis and treated in referral centres. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(5):1292–1299. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simoens S, Hummelshoj L, D’Hooghe T. Endometriosis: cost estimates and methodological perspective. Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13(4):395–404. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmm010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract. 1998;1(1):2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fix GM, Asch SM, Saifu HN, Fletcher MD, Gifford AL, Bokhour B. Delivering PACT-principled care: are specialty care patients being left behind? J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(S2):695–702. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2677-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pappas G, Yujiang J, Seiler N, et al. Perspectives on the role of patient-centered medical homes in HIV care. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(7):e49–53. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Groessl EJ, Sklar M, Cheung RC, Brau N, Ho SB. Increasing antiviral treatment through integrated hepatitis C care: a randomized multicenter trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;35(2):97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aerts L, Grangier L, Streuli I, et al. Psychosocial impact of endometriosis: from co-morbidity to intervention. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;50:2–10. doi: 10.1016/J.BPOBGYN.2018.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stein A, Sauder SK, Reale J. The role of physical therapy in sexual health in men and women: evaluation and treatment. Sex Med Rev. 2019;7(1):46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2018.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agarwal SK, Estrada S, Foster WG, et al. What motivates women to take part in clinical and basic science endometriosis research? Bioethics. 2007;21(5):263–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2007.00552.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogers PA, Adamson GD, Al-Jefout M, et al. Research priorities for endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2017;24(2):202–226. doi: 10.1177/1933719116654991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armour M, Sinclair J, Chalmers KJ, Smith CA. Self-management strategies amongst australian women with endometriosis: a national online survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019;19(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s12906-019-2431-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin DC, Ling FW. Endometriosis and pain. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1999;42(3):664–686. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199909000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’Hooghe T, Hummelshoj L. Multi-disciplinary centres/networks of excellence for endometriosis management and research: a proposal. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(11):2743–2748. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Metzger DA. Treating endometriosis pain: a multidisciplinary approach. Semin Reprod Endocrinol. 1997;15(3):245–250. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1068754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]