Summary

Plant parasitic nematodes (PPN) are important pests of numerous agricultural crops especially vegetables, able to cause remarkable yield losses correlated to soil nematode population densities at sowing or transplant. The concern on environmental risks, stemming from the use of chemical pesticides acting as nematicides, compels to their replacement with more sustainable pest control strategies. To verify the effect of aqueous extracts of the agro-industry waste coffee silverskin (CS) and brewers’ spent grain (BSG) on the widespread root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita, and on the physiology of tomato plants, a pot experiment was carried out in a glasshouse at 25 ± 2 °C. The possible phytotoxicity of CS and BSG extracts was assessed on garden cress seeds. Tomato plants (landrace of Apulia Region) were transplanted in an artificial nematode infested soil with an initial population density of 3.17 eggs and juveniles/mL soil. CS and BSG were applied at rates of 50 and 100 % (1L/pot). Untreated and Fenamiphos EC 240 (nematicide) (0.01 μL a.i./mL soil) treated plants were used as controls. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and chlorophyll content of tomato plants were estimated during the experiment. CS extract, at both doses, significantly reduced nematode population in comparison to the untreated control, although it was less effective than Fenamiphos. BSG extract did not reduce final nematode population compared to the control. Ten days after the first treatment, CS 100 %, BSG 50 % and BSG 100% elicited the highest ROS values, which considerably affected the growth of tomato plants in comparison to the untreated plants. The control of these pests is meeting with difficulties because of the current national and international regulations in force, which are limiting the use of synthetic nematicides. Therefore, CS extracts could assume economic relevance, as alternative products to be used in sustainable strategies for nematode management.

Keywords: Meloidogyne incognita, phytochemicals, sustainable nematode control, tomato, by-products valorization

Introduction

Plant parasitic nematodes (PPN) are important pests of numerous agricultural crops especially vegetables, able to cause remarkable yield losses correlated to soil nematode population densities at sowing or transplant (Sasanelli, 1994; Perry & Moens, 2011). They can also cause indirect damages by opening penetration ways to soil pathogens (Fusarium spp., Verticillium spp., Pyrenochaeta lycopersici etc.) and/or to viruses (Brown et al., 1988) because of the mechanical action of their stylet on the root surface (Ciccarese et al., 2008; Sasanelli et al., 2008).

In particular, the widespread root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.) are of remarkable importance due to their polyphagy. Some of these species are included in the quarantine pest list either of the European Union (EU, Directive 2000/29) and of the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (EPPO) (Wesemael et al., 2010). Concerns for the environmental risks, stemming from the use of chemical pesticides acting as nematicides, recently ended in restrictions provided by the European legislation (EU Reg. 396/2005, 1095/2007, 33/2008, 299/2008, 1107/2009, 459/2010 and 293/2013), that impel their replacement with more sustainable pest control strategies (Renčo, 2013; Abdel-Daym et al., 2014). The use of eco-friendly agro-industrial by-products in pest control is nowadays regarded with increasing interest (Abdel-Dayem et al., 2012; Luque & Clark, 2013). In particular, those with high polyphenols content seems to be particularly effective in controlling plant parasitic nematodes (Chitwood, 2002; Oka, 2010). From this point of view, coffee silverskin (CS) and brewer’s spent grain (BSG) are among the most interesting readily available, high volume and low cost agro-industry by products with high polyphenols content. These by-products, rich in polyphenols content (Regazzoni et al., 2016; Santi Stefanello et al., 2018), are produced in large amount throughout the year (Mussatto & Teixeira, 2010; Lynch et al., 2016).

Coffee silverskin, the only by-product generated during the coffee roasting process (dos Santos Polidoro et al., 2017), is a thin tegument of the outer layer of coffee beans and represents about 4.2 % (w/w) of the entire seed weight (Janissen & Huynh, 2018). The average basic chemical composition of CS is 16 – 18 % of proteins, 2 % of lipids and 4 – 7 % of ash (Borrelli et al., 2004; Carneiro et al., 2009). This by-product is also rich in specific bioactive compounds such as chlorogenic acids (1 – 6 %), caffeine (0.8 – 1.3 %), and melanoidins (17 – 23 %) (Mesías et al., 2014; Behrouzian et al., 2016). CS is used as biofuel (Woldesenbet et al., 2016), fertilizer (Hachicha et al., 2012) and as mushroom cultivation substrate (Fan et al., 2003).

Brewer’s spent grain is the by-product of the beer fermentation process and consists of the husk-pericarp-seed coat layers covering the barley grain. The husk contains considerable amounts of silica and polyphenolic components of the barley grain (Macleod, 1979). The chemical composition of BSG varies according to barley variety, harvest time, malting and mashing conditions (Huige, 1994; Santos et al., 2003). In general, BSG is considered as a lignocellulosic material rich in protein and fibers, containing 15 – 24 % of proteins, 10 % lipids and 2 – 4 % of ash (Kanauchi et al. 2001; Mussatto & Roberto, 2005) and remarkable quantity of bioactive phytochemicals, such as phenolic compounds (Connolly et al., 2015). Among its different uses, it is employed to increase the protein and dietary fibre content of food, in animal feeding (Öztürk et al., 2002) and in industrial processes (Tsaousi et al., 2011; Aggelopoulos et al., 2013).

This work was aimed at studying, in a tomato plant pot experiment, the effect of the aqueous extract of CS and BSG on the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita (Kofoid and White) Chitw. and on the physiology of tomato plants.

Materials and Methods

The pot experiment was carried out at the Institute of Sustainable Plant Protection (IPSP) of the Italian National Research Council (CNR) in Bari (Italy) (40°16’22”N, 16°88’16”East Greenwhich) in a glasshouse, the temperature of which was set at 25 ± 2 °C.

Extracts preparation and characterization

CS and BSG were crushed and suspended in deionized water (1:10 w/vol) in a blender at 8,000 rpm for 5 min, shaken for 1 hour and filtered using a Whatman n.1 filter. The pH of extracts was measured using the pHmeter Basic 20 Crison and the electrical conductivity (EC) by a Sension+ EC7 (Hach) conductivity meter. Total nitrogen and total polyphenols were determined according to Bremner (1996) and Waterhouse’s (2002) methods, respectively. UHPLC Dionex Ultimate 3000 RS system coupled by the HESI– II probe and TSQ Quantum Access Max triple quad mass spectrometer (Thermo Fischer Scientific) was used for the qualitative assessment of polyphenols in CS and BSG aqueous extracts. The separation of compounds was performed at 30 °C on Hipersyl Gold C18 column, 3 μm particle size, i.d. 2.1 mm, 100 mm length (Thermo Fischer Scientific). A binary mobile phase made of a) formic acid aqueous solution at 0.1 % and b) formic acid in acetonitrile solution at 0.1 %, at a constant flow rate of 0.2 mL/min was used. The gradient program of solvent b was set to increase from 10 to 70 % in 20 min. The conditions of the MS system were the following: 320 °C for capillary temperature, 280 °C for source heater temperature, nebulizer gas N2, collision gas Ar, sheath gas flow 35 psi, auxiliary gas flow 10 units, capillary voltage -2.8 kV, tube lens offset 78, 111 and 160 for Q1, Q2 and Q3, respectively. Calibration curves were performed using pure standard phenols solutions of chlorogenic and ferulic acid at concentration ranging from 2.5 mg/L to 20 mg/L. These calibrations, based on ion extracted chromatogram at m/z = [M-H]- from the total ion chromatogram, were used to obtain semi-quantitative data of the caffeoyl quinic and feruloyl quinic derivates compounds identified in the extracts.

Phytotoxicity tests

Phytotoxicity of the CS and BSG aqueous extracts was evaluated measuring the Germination Index (GI) of the garden cress seeds (Lepidium sativum L.) (Zucconi et al., 1981). L. sativum was exposed to the extracts diluted at 30 %, 10 %, 3 % and 1 %. GI was calculated according to the following formula:

where Ns is the number of germinated seeds, Es the root elongation measured in mm and Nw and Ew are the same parameters measured in the control treatment.

Preparation of infested soil and pot experiment

An Italian population of Meloidogyne incognita race 1 (Hartman & Sasser, 1985) was reared for two months on tomato [Lycopersicum esculentum Mill. (L.)] plants (cv. Marmande) in a glasshouse at 25 ± 2 °C. When large mature egg masses were formed, tomato plants were uprooted and their roots gently washed, to free them of adhering soil particles, and finely chopped. To estimate the numbers of eggs and second stage juveniles (J2s) in the chopped roots, ten 5-g root samples were suspended in a 1 % aqueous solution of sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) in 150 mL jars for 3 minutes, after which the eggs and J2s released in the suspension were counted (Hussey & Barker,1973). The roots were then thoroughly mixed with 4 kg of steam sterilized sandy soil (pH 7.9; sand = 85.7 %; silt = 7.1 %; clay = 7.2 % and organic matter = 0.6 %) and used as inoculum. Appropriate amounts of this inoculum were then thoroughly mixed with steam sterilized silty clay loam soil (USDA) in a concrete mixer to obtain a uniformly infested soil. Nematodes, eggs and J2s, were extracted from 8 soil samples to determine the initial population density corresponding to 3.17 eggs and J2s/mL soil (Pi). This infested soil in an amount of 6.5 L was then used to fill plastic pots (V = 7.5 L).

One month old seedling of tomato (landrace of Apulia Region) was transplanted into each pot. There were five replications for each treatment and pots were arranged on benches, in a glasshouse at 25 ± 2 °C, according to a randomized block design. During the experiment tomato plants were maintained randomizing the position of the blocks and at the same time repositioning each plant within a block every week, to avoid a block position effect and at the same time the factor position of the plant within the block. The experiment was performed twice. Plants received all the necessary maintenance (irrigation, fertilization, etc.). Plants were irrigated when it was necessary before their wilting. Hoagland solution (1 L/pot) was used for fertilization (2 times during the experiment) to avoid macro and micro elements deficiency (Hoagland & Arnon, 1950).

The pots were treated with CS and BSG aqueous extracts, obtained as described in the paragraph “Extracts preparation and characterization”, at concentrations of 50 and 100 %. Untreated and Fenamiphos EC 240 (0.01 μL a.i./mL soil) treated pots were used as controls. Each pot received 1 L of extract, or nematicide suspension. CS and BSG treatments were applied twice: at plant transplant and 20 days later.

At the end of the experiment (2 months) plants were uprooted and height, fresh and dry top and root weights were recorded. Root gall index (RGI) was estimated according to a 0 – 10 scale, where 0 = no galls; 1 – 4 = galling of secondary roots only, 5 – 10 = galling of primary laterals and tap root, with 5 equal to 50 % of roots galled and 10 the maximum nematode infestation possible (Bridge & Page, 1980).

Final soil nematode population density was determined in each pot processing 500 mL soil by the Coolen’s method (Coolen, 1979). M. incognita density in roots was assessed by cutting up each root system into small pieces and further comminuting them in a blender, containing 1 % aqueous solution of sodium hypochlorite for three periods of 20 sec (Marull & Pinochet, 1991). The water suspension was sieved on a 250 μm pore sieve over a 22 μm pore sieve. Nematodes and root debris gathered on the 22 μm pore sieve were separated by centrifugation (Beckman, Mod. Allegra X-12) at 2,000 rpm for five min in a magnesium sulfate solution of 1.16 specific gravity. Then eggs and juveniles in the water suspension were sieved again through the 22 μm pore sieve, sprayed with tap water to wash away the magnesium sulfate solution and collected in about 40-60 mL water. Eggs and juveniles in the water suspension were counted and final nematode population density (Pf) in each pot was determined by summing nematodes recovered from soil and roots. The nematode reproduction factor r was expressed as ratio between final and initial population density (Pf/Pi) of M. incognita.

Effects of CS and BSG treatments on Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Chlorophyll levels

To test whether CS and BSG treatments at different concentration doses triggered an oxidative burst, the accumulation of ROS was quantified in tomato roots. ROS contents were determined following the method described in Melillo et al. (2006). Root portions were excised and pre-incubated for 30 min in potassium phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 6). Root tissues were homogenized (in a ratio of 1 mL/50 mg of tissue) inside a working solution containing 50 μM 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein-diacetate (DCFH-DA) (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) dissolved in a potassium phosphate buffer 20 mM pH 6 with 0.2 g/mL of porcine liver esterase (Sigma) and then incubated for 30 min at 25 °C on a shaker. Fluorescence (Ex 488 nm, Em 525 nm) caused by the oxidation of DCFH to DCF was measured by a fluorometer (GloMax-Multi Jr, Promega, Madison, WI, USA). For statistical purposes, fluorometry experiments were performed on six samples.

To verify the effect of CS and BSG treatments on chlorophyll contents, the following methods were used: a) indirect measures of chlorophyll content were recorded with a quick method using the SPAD-502 chlorophyll meter (Konica Minolta, Japan). For each plant ten measurements were recorded between the base and the apex of each leaf lamina and their average calculated as single SPAD value; b) 3 leaves of each treated or untreated plant were sampled and three disks, for each of them, were collected and immediately placed in vials containing 10 mL Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Chlorophyll extraction was obtained following the Tait and Hik’s method (2003). Total chlorophyll content and its concentration were determined by UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Mod. Lambda 25 - Perkin Elmer). Contents of total chlorophyll and chlorophyll a and b, were assessed by using the equations described by Barnes et al. (1992). ROS contents and chlorophyll contents were determined 5 and 10 days after treatments and 25 days later after a second CS and BSG treatments.

Statistical analysis

Data from pot experiment, chlorophyll and SPAD assessments were statistically analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA). The Least Significant Difference’s Test (LSD’s Test) was used for post-hoc analysis of physical and chemical main characteristics of CS and BSG extracts. Student’s t-tests (P ≤ 0.05 and P ≤ 0.01) was used for experimental design of ROS analysis in which we wished to make pairwise comparisons between treatments and their respective controls. Statistical analysis was performed using the Plot IT program Ver. 3.2 (Scientific Programming Enterprises, Haslett, MI, USA).

Results and Discussion

Extracts physical and chemical characteristics

The BSG extract showed a pH value close to neutrality (6.9) whereas a sub acid pH (5.6) was recorded for the CS extract (Table 1). No significant difference was observed for electrical conductivity. Total nitrogen content was significantly higher in BSG than in CS (about 70 %). Total polyphenols were significantly lower in BSG extract in comparison to CS extract (about 15 %) (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Physical and chemical main characteristics of coffee silverskin (CS) and brewer’s spent grain (BSG) extracts.

| Parameters | Unit | BSG | CS | LSD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.05 | 0.01 | ||||

| pH | [H+] | 6.9* ± 0.1 | 5.6 ± 0.1 | 0.13 | 0.22 |

| Electrical Conductivity | mS/cm | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 0.57 | 0.95 |

| Total Nitrogen | g/L | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.35 | 0.57 |

| Total Polyphenols | mg/L | 353 ± 15 | 403 ± 22 | 44.0 | 73.0 |

*Each value is an average of three replications ± SE

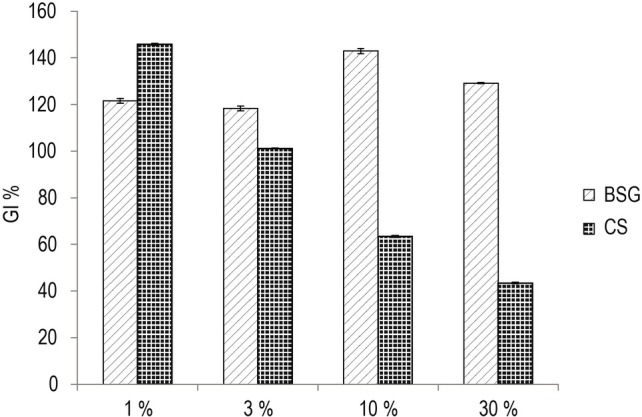

Both CS and BSG extracts exerted a bio stimulating effect at concentration of 1 and 3 %, whereas at concentration of 10 and 30 % BSG increased its bio stimulating effect and CS approached the GI toxicity threshold of 40 % (Zucconi et al., 1981), remaining, however, in the non-toxic range (Fig. 1). It is interesting to note that BSG extract, at a concentration of 10 %, showed a stimulating activity close to 140 % of the control.

Fig. 1.

Phytotoxicity test. Effect of different BSG and CS aqueous extract concentrations on germination index (GI) of garden cress seeds (Lepidium sativum L.).

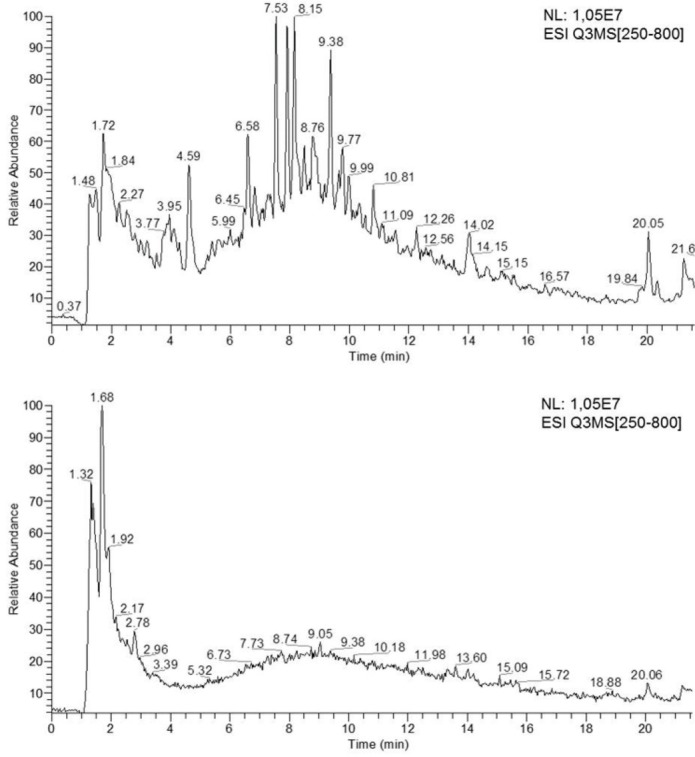

As showed in Figure 2 (top), LC-MS/MS analysis of polyphenols of CS extracts allowed to detect 77 signals. Only 12 of them were identified as quinic derivate considering their MS2 spectra as compared to those reported by Clifford et al. (2003; 2006) and Jaiswal et al. (2010). The 3 isomers of caffeoylquinic acid, 3-CQA, 4-CQA and 5-CQA, were identified using their [M-H]- at m/z 353 and the diagnostic signals with relative abundances at m/z 179, 191 and 173, respectively. Similarly, the feruloyl quinc isomers, 3-FQA, 4-FQA and 5-FQA, were identified using m/z 367 [M-H]- and the diagnostic signals at m/z 193, 173 and 191, respectively. The quinic acid (QA), feruloyl quinic acid-1 (FQA1), feruloyl quinic acid-2 (FQA2), 3-sinapoyl-4-caffeoyl quinic acid (3Si-4CQA), 3-dimethoxycinnamoyl quinic acid (3-DQA) and sinapoyl quinic acid (SiQA) were identified by partial matching with the expected monoisotopic mass and the diagnostic signals and reported in Table 2.

Fig. 2.

Total ions chromatograms of silverskin coffee extract (top) and brewer’s spent grain (bottom) obtained by LC-MS analysis.

Table 2.

Identification and quantification of compounds obtained by LC-MS/MS analysis of silver skin coffee extract (in brackets the relative abundance of each signal).

| RT | [M-H]- | MS2 | mg/L | Name * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.44 | 191 | 85(100) 127(50) | 54.78 | QA |

| 2.23 | 353 | 135(100) 191(80) 179(10) | 3.43 | 3-CQA |

| 3.22 | 353 | 191(100) 161(5) 173(6) | 4.54 | 5-CQA |

| 3.39 | 353 | 136(100) 191(60) 94(40) 173(30) | 7.44 | 4-CQA |

| 3.56 | 367 | 135(100) 193(10) 179(5) 118(5) 94(5) | 2.26 | 3-FQA |

| 4.01 | 367 | 367(100) 269(95) 287(40) 148(20) 349(15) | 2.85 | FQA1 |

| 4.67 | 367 | 367(100) 287(40) 243(40) 349(30) | 2.02 | FQA2 |

| 6.11 | 367 | 173(100) 134(80) 94(60) 193(15) | 2.53 | 4-FQA |

| 6.27 | 367 | 191(100) 135(40) 94(35) 193(15) | 7.71 | 5-FQA |

| 6.53 | 559 | 351(100) | 0.36 | 3Si-4CQA |

| 9.87 | 381 | 358(100) 363(74) 257(48) 273(35) 319(27) 363(25) 336(23) | 4.25 | 3-DQA |

| 12.34 | 397 | 397(100) 325(20) 219(10) | 0.37 | SiQA |

*Q=quinic, F=Feruloyl, C=Caffeoyl, Si=Sinapoyl, D=Dimethoxycinnamoyl, A=Acid

In Figure 2 (bottom), 35 signals detected in LC-MS/MS analysis of BSG extract were reported. Unfortunately, no one of them matched with those described by Quifer-Rada et al. (2015) and Munekata et al. (2016) for beer polyphenols and residues. Therefore, Table 3 reports a structural hypothesis about the possible nature of the molecules found in BSG.

Table 3.

Identification and quantification of compounds obtained by LC-MS/MS analysis of brewer’s spent grain extract (in brackets the relative abundance of each signal).

| RT | [M-H]- | MS2 | Structural hypothesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7.58 | 394 | 289(100) 333(88) 394(88) 305(82) 351(78) 271(36) 297(26) | Ca (289) |

| 7.69 | 329 | 82(100) 247(99) 96(43) 163(37) 125(36) 148(33) 81(30) 173(28) | Co(163) Q frg(173) Dq(329) |

| 8.2 | 265 | 123(100) 86(59) 175(45) 153(19) 168(16) 114(12) 106(11) | P(153) |

| 8.68 | 357 | 163(100) 233(50) 151(10) | Co(163) |

| 8.99 | 331 | 249(100) 153(32) 207(15) 234(13) 150(11) | P(153) |

| 9.01 | 271 | 146(100) 148(59) 136(46) 176(20) 120(17) 163(11) 191(11) | Co(163) Q(191) |

| 9.36 | 373 | 212(100) 283(53) 248(46) 191(43) 209(39) 194(35) | F(194) Q(191) |

| 10.73 | 375 | 312(100) 191(81) 246(52) 187(48) 176(35) 219(24) | Q(191) |

| 12.27 | 538 | 180(100) 414(59) 283(48) 206(28) 383(16) 184(11) | C(180) |

| 12.94 | 480 | 173(100) 262(73) 306(32) 231(22) 480(20) 188(16) 204(15) | Q frg(173) |

| 13.54 | 331 | 157(100) 314(74) 144(39) 153(23) 155(19) 138(18) 171(15) | P (153) |

| 13.95 | 329 | 211(100) 222(44) 173(38) 212(38) 203(37) 163(16) | Co(163) Q(173) Dq(329) |

| 15.58 | 317 | 153(100) 233(30) 112(28) 163(23) 133(19) 215(17) | Co(163) P(153) |

| 17.19 | 541 | 230(100) 117(20) 194(15) 212(10) 153(5) | F (194) P(153) |

Ca=catechin; Co=coumaric; Q=quinic; Dq=dimethylquercetin; P=protocatechuic; F=ferulic; C=caffeic; Frg=fragment.

Pot experiment

In Table 4 the effects of the CS and BSG extracts on the growth of tomato plants infested by M. incognita are reported. The nematode caused a significant reduction in fresh and dry top weight of tomato plants in comparison to CS and BSG treatments. Fresh and dry top weights ranged between 52.5 and 101.5 g and 5.8 and 12.4 g, respectively. No statistical difference was observed between the 2 controls (Fenamiphos treated and untreated). All CS and BSG treatments did not differ from each other for plant fresh and dry top weights (P=0.01). These morphological parameters were not different in CS treated plants and in Fenamiphos treated plants (P=0.01) either. On the contrary, a significant difference was observed between the 2 BSG treatments and the Fenamiphos one (P=0.05). Both CS and BSG treatments had a stimulating effect on tomato growth compared to the untreated plants. Plant heights across treatments ranged between 85.6 cm and 94.2 cm, being not significantly different from those of control pots (73.8) at P=0.01.

Table 4.

Effects of two different concentrations of aqueous solutions of coffee silverskin (CS) and brewer's spent grain (BSG) on the growth of tomato plants (landrace of Apulia Region) infested by the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita.

| Treatment | Dose (%) | Top weight | (g) | Height | (cm) | Root weight (g) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fresh | dry | ||||||||||||

| es | 50 | 76.1*±6.7 | bc** | ABC | 9.3 ± 0.8 | bc | ABC | 88.2 ± 4.4 | ab | A | 8.7 ± 0.7 | b | AB |

| es | 100 | 80.7 ±10.9 | bcd | ABC | 9.6 ± 1.2 | bc | BC | 91.4 ±7 | b | A | 12.2 ± 0.7 | c | BC |

| BSG | 50 | 101.5 ±6.9 | d | C | 12.4 ± 0.9 | d | C | 85.6 ± 2.6 | ab | A | 18.6 ±1.5 | d | D |

| BSG | 100 | 94.4 ± 3.5 | cd | BC | 11.1 ±0.6 | cd | C | 86.8 ± 5.6 | ab | A | 13.3 ± 1.4 | c | C |

| Fenamiphos 240 EC (liquid formulation) | 0.01 soil μL a.i./cm3 | 64.3 ±11.1 | ab | AB | 7.2 ± 1.4 | ab | AB | 94.2 ± 7.5 | b | A | 4.7 ± 0.5 | a | A |

| Untreated control | -- | 52.5 ± 4.5 | a | A | 5.8 ± 0.5 | a | A | 73.8 ± 5.9 | a | A | 12.3 ± 0.9 | c | BC |

* Each value is an average of 5 replications + SE; **Data followed by the same letters in each column are not statistically different according to Least Significant Difference's Test (small letters for P= 0.05; capital letters for P= 0.01).

Root weights in plants treated with BSG at a concentration of 50 % (18.6 g/pot) and Fenamiphos (4.7 g/pot) were significantly higher and lower, respectively, than those in the untreated control (12.3 g/pot) (Table 4). The higher root weight of tomato plants in comparison to Fenamiphos treated pots was due to the presence of numerous galls increasing root weight as already reported by D’Addabbo and Sasanelli (2005). All the other treatments did not influence root weight.

The nematological analysis pointed out that both CS and BSG treatments, independently from the dose, did not reduce root gall index (RGI), if compared to the untreated control (Table 5) (P=0.01). On the contrary, Fenamiphos was able to reduce the RGI to 1.4, a value significantly lower than those of all other treatments, including the untreated control, that spanned from 3.8 to 5.4.

Table 5.

Effects of different concentrations of aqueous solutions of coffee silverskin (CS) and brewer's spent grain (BSG) on the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita infecting tomato plants (landrace Apulia Region).

| Treatment | Dose (%) | Root gall index (0-10) | Eggs and juveniles/g root (x 1,000) | Eggs and juveniles/mL soil | Final population/mL soil (from roots and soil) | Reproduction rate r = Pf/Pi | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | 50 | 3.8*± 0.7 | b** | B | 19.8 ± 1.3 | ab | A | 14.8 ± 1.6 | b | BC | 42.9 ± 2.8 | b | AB | 13.5 ± 0.9 | b | AB |

| CS | 100 | 4 ± ±0.3 | bc | B | 22.4 ± 1.5 | b | AB | 4.8 ± 0.7 | a | A | 52.9 ± 9.4 | b | BC | 16.7 ±1.1 | b | BC |

| BSG | 50 | 4.6 ±0.5 | bc | B | 35.2 ± 2.1 | cd | CD | 5.4 ± 1.3 | a | A | 107 ±10.9 | d | D | 33.7 ± 3.4 | d | D |

| BSG | 100 | 4.2 ±0.6 | bc | B | 29.3 ± 1.7 | c | BC | 16.8 ± 3.3 | b | C | 69.1 ±11.4 | bc | BC | C16.8 ±3.3bC6 | bc | BC |

| Fenamiphos 240 EC (liquid formulation) | 0.01 μL/ cm3 soil | 1.4 ±0.5 | a | A | 13.8 ± 2.9 | a | A | 5.8 ± 0.9 | a | A | 13.1 ±1.2 | a | A | 3.1 ±1.2aA4 | a | A |

| Untreated control | -- | 5.4 ±0.2 | c | B | 40.3 ± 3.5 | d | D | 8.2 ± 1.8 | a | AB | 82.2 ±13.6 | cd | CD | 25.9 ± 4.3 | cd | CD |

* Each value is an average of 5 replications + SE; **Data followed by the same letters in each column are not statistically different according to Least Significant Difference's Test (small letters for P= 0.05; capital letters for P= 0.01).

Nevertheless, CS treatments were effective to reduce eggs and juveniles/g root by 50.9 and 44.4 % respectively, compared to the untreated control (Table 5) (P=0.01), irrespective of the concentration used. In addition, the observed nematicidal effect was no significantly different from that observed in Fenamiphos treated pots (P=0.01). CS treatments were more effective than BSG treatments in reducing nematode population on the roots (P = 0.05).

Soil nematode population density was lowered by CS 100 % (4.8 eggs and juveniles/mL soil) and BSG 50 % (5.4 eggs and juveniles/mL soil) treatments and was no statistically different from Fenamiphos (5.8 eggs and juveniles/mL soil) and the untreated control (8.2 eggs and juveniles/mL soil).

The final nematode population density, calculated summing nematodes from roots and soil, was reduced in CS 50 % and 100 % treatments by 47.8 and 35.6 %, respectively if compared to the untreated control. Interestingly, this parameter, in the CS 50 % treatment, was not significantly different (P = 0.05) from that recorded in Fenamiphos treated pots. By contrast, BSG treatments, at both concentrations, were not effective in reducing the final nematode population in comparison to the control.

The same results were obtained for the nematode reproduction factor (Pf/Pi). The lowest and the highest reproduction factors were recorded in Fenamiphos and BSG 50 % treatments, respectively (Table 5).

It is well known that substances with a high polyphenols content display a substantial nematicidal effect, the intensity of which is also related to the species of nematode concerned. Considering that CS and BSG extracts have both a high content of polyphenols, their different performances in assuring nematode control can be explained with their different polyphenols composition. This hypothesis is in line with the results of D’Addabbo et al. (2013), who studied the nematicidal activity of pure chlorogenic and caffeic acids and the extract of Artemisia annua on the nematodes M. incognita, Globodera rostochiensis (Woll.) Behrens and Xiphinema index Thorne et Allen. They found a high effect of these compounds on G. rostochiensis, a partial response on X. index and a low activity on M. incognita. Chlorogenic acid was able to elicit 100 % of juvenile mortality in X. index at a concentration of 125 μg/mL after 8 h of exposure, whereas caffeic acid produced the same result after 4 hrs of exposure, at the same concentration. The authors found a very little effect of these compounds against M. incognita, with the maximum observed effect after more than 24 h of exposure at the maximum concentration (500 μg/mL). The plant extracts were not able to produce the same nematicidal activity observed for pure chlorogenic and caffeic acids. However, A. annua extract was able to reduce significantly (50 %) the hatching percentage of eggs of M. incognita and G. rostochiensis in comparison to the control (distilled water). Considering these results, it is plausible that caffeoyl and feruloyl quinic derivates, identified in the CS extract, could be responsible for the observed nematicidal effect on the M. incognita population in our pot experiment.

Effects of CS and BSG treatments on ROS and Chlorophyll levels In plants ROS are implicated as key signaling molecules in the regulation of numerous biological processes such as growth, development and responses to biotic and/or abiotic stimuli (Baxter et al., 2014). ROS production was used as a phytotoxicity index of the tomato roots exposed to both doses of CS and BSG extracts. No ROS accumulation was detected in roots 5 days after treatments at the two applied doses (50 and 100 %) (Table 6) in comparison to the untreated plants. A significant increase (P=0.01) in ROS content was detected 10 days after BSG treatments in roots at both concentrations. In roots treated with 100 % of CS a significant ROS increase was recorded (Table 6). Twenty days after the first treatment, plants were newly treated with both extracts and ROS amount was evaluated 5 days later. A significant ROS accumulation was evident only in roots treated with 100 % CS compared to untreated and BSG-treated plants.

Table 6.

Effect of coffee silverskin (CS) and brewer’s spent grain (BSG) extracts soil treatments, at two concentrations (50 and 100%), on plant growth and reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation in tomato roots (landrace Apulia Region).

| Treatment | Dose | 5 days after 1st treatment | 10 days after 1st treatment | 5 days after 2nd treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | ROS content | Plant weight (g) | ROS content | Plant weight (g) | ROS content | Plant weight (g) | |

| BSG | 50 | 3,482 ± 125 | 4.96 ± 1.38 | 3,738 ± 69** | 6.45 ± 0.86* | 3,682 ± 77 | 30.83 ± 2.63 |

| BSG | 100 | 3,725 ± 71 | 3.37 ± 0.79 | 3,840 ± 50** | 5.36 ± 1.05* | 2,999 ± 82 | 28.97 ± 1.31 |

| CS | 50 | 3,444 ± 127 | 4.57 ± 0.82 | 3,325 ± 129 | 7.91 ± 1.44 | 3,392 ± 157 | 26.89 ± 2.04 |

| CS | 100 | 3,777 ± 165 | 4.11 ± 1.08 | 3,764 ± 130** | 6.42 ± 1.18* | 4,681 ± 139** | 29.93 ± 0.49 |

| Control | 3,3721 ± 182 | 4.91 ± 0.94 | 3,131 ± 148 | 11.00 ± 0.93 | 3,360 ± 203 | 27.13 ± 3.06 | |

Each value is an average of fluorescence units (FSU 50 mg-1 root fresh weight) of two experiments each containing six replications ± SE; Asterisks indicate statistically significant difference in comparison to the untreated control according to Student’s t-test (* for P≤0.05, ** for P≤0.01).

The treatments CS 100 %, BSG 50 % and BSG 100 % elicited the highest ROS values, which considerably affected the growth of tomato plants (Table 6). Five days after the second treatment plants recovered the loss of weight, compared to control. Because cell membranes are one of the major sites of ROS activity under environmental stress (Mittler, 2002), higher levels of ROS in CS-and BSG-treated plants might induce cellular damage leading to apoptic-like programmed cell death. Moreover, as high levels of ROS serve as substrates for synthesis of secondary metabolites or as components enforcing the physical barrier of the cell walls their accumulation in treated roots alert plants to limit nematode infection.

Chlorophyll content (Chl) in all treated tomato plants did not differ from that of the control at 5 and 10 days after the first treatment (Table 7). No difference, at both observation times, was found in total chlorophyll, Chl a and b. After the second treatment, a significant difference was observed in chlorophyll a content in plants treated with CS 100 % (29.7 μg/cm2) in comparison to all other treatments included the control (33.3 μg/cm2) (Table 7). It is well known that ROS enhancement can cause the degradation of photosynthetic pigments and damage to photosynthetic machinery (Mittler, 2002). High ROS levels found after treatments may have directly or indirectly contributed to the decline in the observed chlorophyll levels.

Table 7.

Effect of different concentrations of coffee silverskin (CS) and brewer’s spent grain (BSG) aqueous extracts on chlorophyll content (Chl) of leaves of treated or untreated (control) tomato plants (landrace of Apulia Region) at 5, 10 and 25 days after treatments.

| 15/11/2017 (5 days – after the first treatment) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Dose (%) | Chl a (μg/cm2) | Chl b (μg/cm2) | Chl tot. (μg/cm2) | |||

| CS | 50 | 27.6* ± 1.7 | a** | 7 ± 1.6 | a | 34.6 ± 3.2 | a |

| CS | 100 | 26.7 ± 4 | a | 7.3 ± 1.1 | a | 34.1 ± 5.1 | a |

| BSG | 50 | 28.9 ± 2.7 | a | 8.1 ± 0.7 | a | 37 ± 3.4 | a |

| BSG | 100 | 26.7 ± 2.9 | a | 7.7 ± 1.2 | a | 34.3 ± 4 | a |

| Control | 28.1± 1.3 | a | 7.9 ± 0.4 | a | 36.1 ± 1.7 | a | |

| 20/11/2017 (10 days - after the first treatment) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Dose (%) | Chl a (μg/cm2) | Chl b (μg/cm2) | Chl tot. (μg/cm2) | |||

| CS | 50 | 29.4 ± 2 | a | 7.4 ± 0.3 | a | 36.7 ± 2.1 | a |

| CS | 100 | 31.4 ± 0.6 | a | 8.3 ± 0.4 | a | 39.7 ± 0.9 | a |

| BSG | 50 | 28.8 ± 1.9 | a | 7.8 ± 0.6 | a | 36.5 ± 1.7 | a |

| BSG | 100 | 29.3 ± 2.1 | a | 7.8 ± 0.7 | a | 37.2 ± 2.5 | a |

| Control | 32 ± 0.7 | a | 8.4 ± 0.4 | a | 40.5 ± 1.1 | a | |

| 05/12/2017 (5 days - after the second treatment) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Dose (%) | Chl a (μg/cm2) | Chl b (μg/cm2) | Chl tot. (μg/cm2) | |||

| CS | 50 | 33.6 ± 1.7 | a | 11.4 ± 2.7 | a | 45.1 ± 4.4 | a |

| CS | 100 | 29.7 ± 0.7 | b | 7.9 ± 0.1 | a | 37.7 ± 0.7 | a |

| BSG | 50 | 34.3 ± 1.9 | a | 8.9 ± 0.7 | a | 43.2 ± 2.6 | a |

| BSG | 100 | 33.3 ± 0.2 | a | 9.1 ± 0.2 | a | 42.4 ± 0.4 | a |

| Control | 33.3 ± 2.2 | a | 9.5 ± 1.2 | a | 42.8 ± 3.4 | a | |

Each value is an average of 3 replications ±SE;** Data followed in each column by the same letter are not significantly different according to Least Significant Difference’s Test (LSD’s Test) (P≤0.05).

Conclusions

Yield losses caused worldwide by root-knot nematodes require to find ecofriendly control strategies with low environmental impact (Stirling, 2014) considering that the control of these pests is meeting with difficulties as current national and international regulations are limiting the use of synthetic nematicides which exert serious detrimental effects on the environment (Sánchez-Moreno et al., 2009). In our study both tested by-product extracts were not phytotoxic to tomato plants as shown by the morpho-physiological parameters of the treated plants. All this makes CS extracts of economic relevance, as alternative products to be used in sustainable strategies for nematode management. The observed nematicidal effect of CS extract against M. incognita is related to the release of polyphenols (caffeoyl and feruloyl quinic derivates) from the coffee epidermis as demonstrated for other agro-industrial by-products as grape pomace (D’Addabbo et al., 2000) or olive mill wastes (Sasanelli et al., 2002).

Future research needs consist of the setup of techniques able to produce commercial CS extracts with a standardized composition and known nematicidal efficacy. However, further studies are also needed to investigate the effect of CS extracts on different nematode species and types of soils.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Authors state no conflict of interest

References

- Abdel-dayem E., Erriquens F., Verrastro V., Sasanelli N., Mondelli D., Cocozza C.. Nematicidal and fertilizing effects of chicken manure, fresh and composted olive mill wastes on organic melon. Helminthologia. 2012;49(4):259–2012. doi: 10.2478/s11687-012-0048-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-daym E., Erriquens F., Sasanelli N., Ceglie F.G., Zaccone G., Miano T., Cocozza C.. Effects of several amendments on organic melon growth and production, Meloidogyne incognita population and soil properties. Sci. Hortic. 2014;180:156–160. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2014.10.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aggelopoulos T., Bekatorou A., Pandey A., Kanellaki M., Koutinas A.A.. Discarded oranges and brewer’s spent grains as promoting ingredients for microbial growth by submerged and solid state fermentation of agro-industrial waste mixtures. App. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2013;170(8):1885–1895. doi: 10.1007/s12010-013-0313-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes J.D., Balaguer L., Manrique E., Elvira S., Davison A.W.. A reappraisal of the use of DMSO for the extraction and determination of chlorophylls a and b in lichens and higher plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 1992;32:85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter A., Mittler R., Suzuki N. ROS as key players in plant stress signaling. J. Exp. Bot. 2014;66:1229–1240. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert375. Epub 2013 Nov 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrouzian F., Amini A. M., Alghooneh A., Razavi S.M.A.. Characterization of dietary fiber from coffee silverskin: An optimization study using response surface methodology. Bioact. Carbohydr. Dietary Fibre. 2016;8(2):58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bcdf.2016.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borrelli R. C., Esposito F., Napolitano A., Ritieni A., Fogliano V.. Characterization of a new potential functional ingredient: coffee silverskin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004;52(5):1338–1343. doi: 10.1021/jf034974x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner J. M. Sparks D.L., Page A.L., Helmke P.A., Loeppert R.H. Methods of Soil Analysis Part 3-Chemical Methods, SSSA Book Ser. 5.3. SSSA; ASA, Madison, WI: 1996. Nitrogen-Total; p. 1085 – 1121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge J., Page S.L.J.. Estimation of root-knot infestation level on roots using a rating chart. Trop. Pest Manag. 1980;26:296–298. [Google Scholar]

- Brown D.J.F., Lamberti F., Taylor C. E., Trudgill D. L.. Nematode-virus plant interactions. Nematol. Mediterr. 1988;16:153–158. [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro L.M., Silva J.P.A., Mussatto S.I., Roberto I.C., Teixeira J.A. Book of abstracts of the VIIIth International Meeting of the Portuguese Carbohydrate Group, GLUPOR. Braga, Portugal: 2009. Determination of total carbohydrates content in coffee industry residues; p. 94. 6 – 10 September. [Google Scholar]

- Chitwood D.J.. Phytochemical based strategies for nematode control. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2002;40:221–249. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.40.032602.130045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarese F., Sasanelli N., Gallo M., Papajova I., Renčo M. Proceedings Biotechnology 2008. Czech Budejovice: Czech Republic; 2008. Biological control of Fusarium-wilt and the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita on Cucumis melo subsp. Melo conv. Adzhur (Pang.) Grebensch; pp. 33–35. 13 – 14 February. [Google Scholar]

- Clifford M.N., Johnston K.L., Knight S., Kuhnert N.. Hierarchical scheme for LC-MSn identification of chlorogenic acids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003;51:2900–2911. doi: 10.1021/jf026187g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford M.N., Knight S., Surucu B., Kuhner N.. Characterization by LC-msn of four new classes of chlorogenic acids in green coffee beans: dimethoxycinnamoylquinic acids, diferuloylquinic acids, caffeoyl-dimethoxycinnamoylquinic acids, and feruloyl-dimethoxycinnamoylquinic acids. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2006;54:1957–1969. doi: 10.1021/jf0601665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly A., O’Keeffe M. B., Piggott C. O., Nongonierma A. B., Fitzgerald R. J.. Generation and identification of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory peptides from a brewers’ spent grain protein isolate. Food Chem. 2015;176:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coolen W.A. Lamberti F., Taylor C.E. Root-knot nematodes Meloidogyne species Systematics, Biology and Control. London (UK): Academic Press; 1979. Methods for the extraction of Meloidogyne spp., and other nematodes from roots and soil; pp. 317–329. [Google Scholar]

- D’addabbo T., Sasanelli N.. Azione soppressiva di differenti formulati di piante biocide sul nematode galligeno Meloidogyne incognita. Nematol. Mediterr. 2005;33(Suppl):47–50. In Italian. [Google Scholar]

- D’addabbo T., Sasanelli N., Lamberti F., Carella A.. Control of root-knot nematodes by olive and grape pomace soil amendments. Acta Hortic. 2000;532:53–57. [Google Scholar]

- D’addabbo T., Carbonara T., Argentieri M.P., Radicci V., Leonetti P., Villanova L., Avato P.. Nematicidal potential of Artemisia annua and its main metabolites. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2013;137:295–304. doi: 10.1007/s10658-013-0240-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dos SANTOS POLIDORO, A., Scapin E., Lazzari E., Silva A. N., Dos santos A. L., Caramão E. B., Jacques R. A.. Valorization of coffee silverskin industrial waste by pyrolysis: From optimization of bio-oil production to chemical characterization by GC× GC/qMS. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis. 2017;129:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jaap.2017.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan L., Soccol A., Pandey A., Soccol C.. Cultivation of Pleurotus mushrooms on Brazilian coffee husk and effects of caffeine and tannic acid. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2003;15(1):15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hachicha R., Rekik O., Hachicha S., Ferchichi M., Woodward S., Moncef N., Cegarra J., Mechichi T.. Co-composting of spent coffee ground with olive mill wastewater sludge and poultry manure and effect of Trametes versicolor inoculation on the compost maturity. Chemosphere. 2012;88(6):677–682. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman K.M., Sasser J.N. Barker K.R., Carter C. C., Sasser J. N. An advanced Treatise on Meloidogyne Vol. II: Methodology. North Carolina State University Graphics; Raleigh, NC, U.S.A: 1985. Identification of Meloidogyne species on the basis of differential host test and perineal-pattern morphology; pp. 69–77. (Eds) [Google Scholar]

- Hoaogland D.R., Arnon D.I. The Water-Culture method for growing plants without soil Circular 347. The college of agriculture - University of California; Berkeley: 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Huige N.J. Hardwick W.A. Handbook of Brewing. Marcel Dekker; New York, U.S.A: 1994. Brewery by-products and effluents; pp. 501–550. [Google Scholar]

- Hussey R.S., Barker K.R.. A comparison of method of collecting inocula di Meloidogyne spp. including a new technique. Plant Dis. Reptr. 1973;57:1025–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal R., Patras M. A., Eravuchira P. J., Kuhnert N.. Profile and characterization of the chlorogenic acids in green robusta coffee beans by LC-MSn: identification of seven new classes of compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58:8722–8737. doi: 10.1021/jf1014457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janissen B., Huynh T.. Chemical composition and value-adding applications of coffee industry by-products: A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018;128:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanauchi O., Mitsuyama K., Araki Y.. Development of a functional germinated barley foodstuff from brewers’ spent grain for the treatment of ulcerative colitis. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2001;59:59–62. [Google Scholar]

- Luque R., Clark J. H.. Valorisation of food residues: waste to wealth using green chemical technologies. Sustain. Chem. Process. 2013;1(1):10. doi: 10.1186/2043-7129-1. – 10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch K. M., Steffen E. J., Arendt E. K.. Brewers’ spent grain: a review with an emphasis on food and health. J. Inst. Brew. 2016;122(4):553–568. doi: 10.1002/jib.363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod A.M. Pollock J.R.A. Brewing Science, Vol. 1. Academic Press; New York, U.S.A: 1979. The physiology of malting; pp. 145–232. [Google Scholar]

- Marull J., Pinochet J.. Host suitability of Prunus rootstock to four Meloidogyne species and Pratylenchus vulnus in Spain. Nematropica. 1991;21:185–195. [Google Scholar]

- Melillo M.T., Leonetti P., Bongiovanni M., Castagnone-sereno P., Bleve-zacheo T.. Modulation of reactive oxygen species activities and H2O2 accumulation during compatible and incompatible tomato–root-knot nematode interactions. New Phytol. 2006;170:501–512. doi: 10.1111/J.1469-8137.2006.01724.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesías M., Navarro M., Martínez-Saez N., Ullate M., Del castillo M., Morales F.. Antiglycative and carbonyl trapping properties of the water soluble fraction of coffee silverskin. Food Res. Int. 2014;62:1120–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.05.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R.. Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant. Sci. 2002;7:405–410. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munekata P.E.S., Franco D., Trindade M.A., Lorenzo J.M.. Characterization of phenolic composition in chestnut leaves and beer residue by LC-DAD-ESI-MS. LTW - Food Sci. Technol. 2016;68:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.11.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mussatto S.I., Roberto I.C.. Acid hydrolisis and fermentation of brewers’ spent grain to produce xylitol. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2005;85:2453–60. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mussatto S. I., Teixeira J. A.. Increase in the fructo-oligosaccharides yield and productivity by solid-state fermentation with Aspergillus japonicus using agro-industrial residues as support and nutrient source. Biochem. Eng. J. 2010;53(1):154–157. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2010.09.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oka Y.. Mechanisms of nematode suppression by organic soil amendments - A review. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2010;44:101–115. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2009.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Öztürk S., Özboy Ö., Cavidoğlu İ., Köksel H.. Effects of brewer’s spent grain on the quality and dietary fibre content of cookies. J. Inst. Brew. 2002;108(1):23–27. doi: 10.1002/j.2050-0416.2002.tb00116.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perry R.N., Moens M. Jones J., Gheysen G., Fenoll C. Genomics and molecular genetics of plant-nematode interactions. Springer; Dordrecht: 2011. Introduction to plant parasitic nematodes; modes of parasitism; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Quifer-rada P., Vallverdù-Queralt A., Martìnez-Huélamo M., Chiva-blanch G., Jàuregui O., Estruch R., Lamuela-Raventòs R.. A comprenhensive characterisation of beer polyphenols by high resolution mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-LTQ-Orbitrap-MS) Food Chem. 2015;169:336–343. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.07.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regazzoni L., Saligari F., Marinello C., Rossoni G., Aldini G., Carini M., Orioli M.. Coffee silver skin as a source of polyphenols: High resolution mass spectrometric profiling of components and antioxidant activity. J. Funct. Foods. 2016;20:472–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2015.11.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Renčo M.. Organic amendments of soil as useful tools of plant parasitic nematodes control. Helminthologia. 2013;50(1):3–14. doi: 10.2478/s11687-013-0101-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Moreno S., Alonso-prados E., Alonso-prados J. L., García-Baudín J. M.. Multivariate analysis of toxicological and environmental properties of soil nematicides. Pest Manag. Sci. 2009;65(1):82–92. doi: 10.1002/ps.1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santi stefanello F., Obem dos santos C., Caetano bochi V., Burin fruet A.P., Bromenberg soquetta M., Dörr A.C., Laerte Nörnberg J.. Analysis of polyphenols in brewer’s spent grain and its comparison with corn silage and cereal brans commonly used for animal nutrition. Food Chem. 2018;239:385–401. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.06.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos M., Jiménez J.J., Bartolome B., Gòmez-Cordovés C., Del nozal M.J.. Variability of brewers’ spent grain within a brewery. Food Chem. 2003;80:17–21. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(02)00229-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sasanelli N.. Tables of Nematode-Pathogenicity. Nematol. Mediterr. 1994;22:153–157. [Google Scholar]

- Sasanelli N., D’addabbo T., Convertini G., Ferri D.. Soil Phytoparasitic Nematodes Suppression and Changes of Chemical Properties Determined by Waste Residues from Olive Oil Extraction. Proceedings of 12th ISCO Conference. 2002;VOL. III:588 – 592. May 26 – 31, 2002 Beijing China. [Google Scholar]

- Sasanelli N., Ciccarese F., Papajova I.. Aphanocladium album by via sub-irrigation in the control of Pyrenochaeta lycopersici and Meloidogyne incognita on tomato in a plastic-house. Helminthologia. 2008;45:137–142. doi: 10.2478/511687-008-0027.y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stirling G. R. Biological control of plant-parasitic nematodes: Soil Ecosystem Management in Sustainable Agriculture. Biological Crop Protection Pty. Ltd; Australia: 2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tait M.A., Hik D.S.. Is dimethylsulfoxide a reliable solvent for extracting chlorophyll under field conditions? Photosynth. Res. 2003;78:87–91. doi: 10.1023/A:1026045624155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsaousi K., Velli A., Akarepis F., Bosnea L., Drouza C., Koutinas A. A., Bekatorou A.. Low-Temperature winemaking by thermally dried immobilized yeast on delignified brewer’s spent grains. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2011;49(3):379–384. [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse A.L.. Wine Phenolics. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2002;957:21–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesemael W.M.L., Viaene N., Moens M.. Root-knot nematodes Meloidogyne spp.) in Europe. Nematology. 2010;13:3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Woldesenbet A. G., Woldeyes B., Chandravanshi B. S.. Bio-ethanol production from wet coffee processing waste in Ethiopia. SpringerPlus. 2016;5(1):1903. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-3600-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucconi F., Forte M., Monaco A., Beritodi M.. Biological evaluation of compost maturity. Biocycle. 1981;22:27–29. [Google Scholar]