Abstract

Introduction:

This study aimed to find the association of serum calcium level with abdominal obesity according to the waist circumference (WC) and the associated factors.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional study was carried out at private health-care center. A total of 291 patients, aged 18 years and above, with type 2 diabetes mellitus who attended the clinic from May 2017 through March 2018 were included. Sociodemographic, clinical, and laboratory data were obtained from the medical records of patients. Statistical analysis was carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (SPSS, version 23). Abdominal obesity was defined by WC ≥ 80cm in women and ≥94cm in men.

Results:

A total number of 291 participants participated in the study. Among these participants, 42.6% (n = 124) were male and 57.4% (n = 167) were female. The average age of respondents was 55.99 ± 9.81 years. Among the male participants, 90 (72.6%) (95% confidence interval [CI]: 64.6%–80.5%) were abdominally obese as were 154 participants (92.2%) (95% CI: 88.1%–96.3%) among females. Overall, 244 participants (83.8%) (95% CI: 79.6%–88.1%) were abdominally obese. The results of statistical modeling showed that gender, smoking status, physical activity, and serum calcium are strong determinants of abdominal obesity.

Conclusion:

This study revealed a significant association of abdominal obesity and serum calcium level among patients with diabetes.

Keywords: Abdominal obesity, calcium, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, waist circumference

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus, abbreviated DM, is commonly identified as diabetes. It is a metabolic disorder whose main feature is the elevation of blood sugar level for an extended period.[1] Complications of uncontrolled diabetes include a hyperosmolar diabetic state, diabetic ketoacidosis, and in extreme cases, death.[2] Chronic complications include chronic kidney disease, stroke, cardiovascular disease, eye damage, and foot ulcers.[3]

Diabetes is due to two major causes—either the pancreas produces insufficient insulin or the pancreas produces more than enough insulin—but the cells of the body fail to respond to it.[4] Type 2 DM is caused mainly by insensitivity of the body cells to the pancreas. Here, the cells fail to respond to insulin. The progression of the disease leads to lack of insulin.[5] It is commonly caused by a sedentary life and excessive body weight.[2]

Insulin injections are necessary for the management of type 1 DM.[2] On the contrary, type 2 diabetes can be managed with medications even without insulin.[6] Blood sugar level can be controlled by insulin and oral medications.[7] Obese patients may undergo weight loss surgery as a means of treatment, especially in cases of type 2 diabetes.[8] Gestational diabetes on the other hand resolves on delivery.[9]

A look at recent epidemiological statistics shows that over 425 million persons were affected by diabetes in 2017.[10] It is worth noting that type 2 DM made up 90% of these cases.[11,12] With reference to the adult population, this makes up approximately 8%, which is equally distributed in both genders.[10,13] A look at the current trend indicates that there will be a continual rise.[10] Diabetics are also at risk of early death.[2] Approximately 3.2–5 million diabetes-related deaths were recorded in 2017. More than US $700 billion was lost to diabetes in 2017. This represents the global economic cost as at 2017.[10]

The most important risk factor for type 2 DM, one that can be modified, is excess weight. Studies have shown that 85%–90% of patients with type 2 diabetes are either obese or overweight.[14] A look at epidemiological studies shows that an important predictor of type 2 DM is the individual’s body mass index (BMI).[15] A study by Field et al.[16] showed that persons of both genders with a BMI higher than 35kg/m2 were 20 times more at risk of developing type 2 diabetes compared to the control group. Obesity, however, is heterogeneous, and some obese patients are quite sensitive to insulin. Studies have also shown that patients with very high obesity have a normal plasma lipoprotein–lipid profile in spite of the high body fat.[17]

Waist circumference (WC) (which is used as a measurement for abdominal obesity) was proposed a risk factor for type 2 DM.[18] However, it is worth noting that total body fat is not the only indicator of obesity; metabolic risk is also determined by fat distribution as well as the portion of lipids present in tissues that are insulin sensitive, such as liver and skeletal muscle.[19]

Fat accumulation in the abdominal region has a relationship with insulin resistance and is a major indicator of metabolic syndrome, which increases the risk of cardiovascular and diabetes by 1.5–2-fold.[20] Abdominal obesity is associated with a number of cardiovascular risk factors. These factors according to the World Health Organization are defined as “metabolic syndrome.” The metabolic syndrome is characterized by insulin resistance, abdominal obesity, dyslipidemia, high-fasting glucose, hypertension, high level of plasminogen activator (PAI-1), and pro-inflammatory state.[21] Abdominal obesity is believed to be a major trigger of insulin resistance because of the rise in free fatty acid (FFA) flow to the liver and a rise in the secretion of inflammatory mediators. Studies have shown that patients with abdominal obesity have their FFA lipolysis increased by 50% compared to lean persons whose FFA turnover is reduced by 50%.[22] Also, patients with abdominal obesity have a higher rate of FFA lipolysis compared to patients with non-abdominal obesity.[22]

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted in health-care center in Ramallah District, Palestine. It comprised a systematic sample of 291 patients with type 2 diabetes from September 2017 through February 2018. The study was approved by the health and ethics committee of the health center, and all the participants gave their informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Relevant sociodemographic, clinical, and laboratory data were obtained from the medical records of the patients, including age, gender, and calcium level. Measurement of the last recorded serum vitamin D level was also considered in the study. This information was recorded on the data sheet. Anthropometric measurements were taken, including weight and height. Abdominal obesity was defined by WC (WC ≥80cm in women and ≥94cm in men).[2]

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), IBM Corporation, version 23). Chi-square tests and multivariate logistic regression test were used to assess the correlation between abdominal obesity and serum calcium level among patients with diabetes and other related risk factors. Separate regression models were used, and stepwise method was used for variable selection and model building.

Results

Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics

The demographic information of the participants is shown in Table 1. A total number of 291 participants participated in the study. Among these participants, 42.6% (n = 124) were male and 57.4% (n = 167) were female. The average age of respondents was 55.99 ± 9.81 years. Regarding the age groups, 25.4% (n = 74) were aged between 28 and 51 years, 49.8% (n = 145) aged 52–62 years, and 24.7% (n = 72) aged ˃62 years. Majority of the participants (74.2%) were married. Educational qualifications of the participants also varied. Appropriately 21% (n = 61) of the participants were elementary school education holders, 44.3% (n = 129) were high school education holders, and 34.7% (n = 101) were bachelor’s degree holders.

Table 1.

Frequency table for demographic and socio-economic characteristics (n = 291)

| Demographic characteristics | Response | Frequency (percentage) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 124 (42.6%) |

| Female | 167 (57.4%) | |

| Age group | 28–51 | 74 (25.4%) |

| 52–62 | 145 (49.8%) | |

| >62 | 72 (24.7%) | |

| Marital status | Single | 75 (25.8%) |

| Married | 216 (74.2%) | |

| Educational level | Elementary | 61 (21%) |

| High school | 129 (44.3%) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 101 (34.7%) |

Clinical and lifestyle characteristics

The clinical and lifestyle information of participants are shown in Table 2. Of the total participants, 228 (78.4%) were nonsmokers, 30 (10.3%) were past smokers, and 33 (11.3%) were current smokers. Among the total participants, 74 (25.4%) were non-physically active and 217 (74.6%) were physically active. Average height of the participants was 165.17 ± 10.16 cm. Average weight of the participants was 82.93 ± 49.98kg. Average BMI of the participants was 30.51 ± 19.60kg/m2. In this study, a total of 57 (19.6%) participants were normal weighted (<25kg/m2), 136 (46.7%) were overweight (25–29.9kg/m2), and 98 (33.7%) were abdominally obese. The average serum calcium level of the participants was 9.2 ± 0.5mg/dL. The average serum vitamin D level of the participants was 19.5 ± 21ng/mL. Of the total participants, 17.9% (n = 52) used metformin and 4.1% (n = 12) took sulfonylurea.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for clinical and lifestyle characteristics (n = 291)

| Clinical and lifestyle characteristics | Response | Frequency (percentage) |

|---|---|---|

| Smoking status | Nonsmoker | 221 (75.9%) |

| Smoker | 70 (24.1%) | |

| Physical activity | Yes | 74 (25.4%) |

| No | 217 (74.6%) | |

| Body mass index | Normal (<25kg/ m2) | 57 (19.6%) |

| Overweight (25–29.9kg/m2) | 136 (46.7%) | |

| Obese (≥30kg/m2) | 98 (33.7%) | |

| Taking metformin | Yes | 52 (17.9%) |

| No | 239 (82.1%) | |

| Taking sulfonylurea | Yes | 12 (4.1%) |

| No | 279 (95.9%) | |

| Age | ||

| Mean ± SD | 55.99 ± 9.81 | |

| Height (cm) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 165.17 ± 10.16 | |

| Weight (kg) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 82.93 ± 49.98 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 30.51 ± 19.60 | |

| Serum calcium (mg/dL) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 9.2 ± 0.5 | |

| Serum vitamin D (ng/mL) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 19.5 ± 21 |

SD = standard deviation

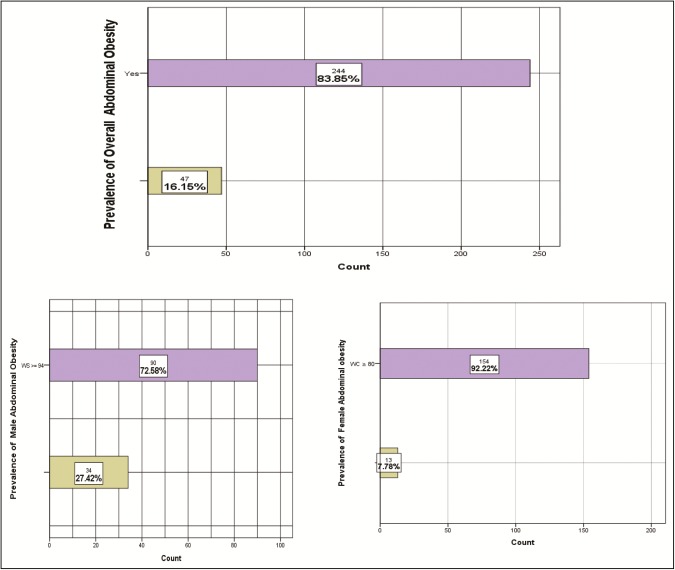

Prevalence of abdominal obesity according to waist circumference

Among the male participants, 90 (72.6%) (95% confidence interval [CI]: 64.6%–80.5%) were abdominally obese as were 154 (92.2%) (95% CI: 88.1%–96.3%) among the female participants. Overall, 244 participants (83.8%) (95% CI: 79.6%–88.1%) were abdominally obese. The prevalence of abdominal obesity was significantly higher in women (63.1%) than that in men (36.9%) (P < 0.001). Table 3 shows the prevalence of abdominal obesity among women and men by demographic and socioeconomic status. It provides the estimates along with P values. The prevalence of abdominal obesity among men and women was significantly associated with marital status (P < 0.001), educational level (P < 0.001), smoking status (P < 0.001), physical activity (P < 0.001), and sulfonylurea users (P = 0.019). Regarding the calcium homeostasis, a significant association was observed between the serum calcium level and abdominal obesity with lower serum calcium levels for the abdominal obese participants (P < 0.001). The same pattern of results was reported for vitamin D homeostasis, a significant association was observed between the serum vitamin D levels and abdominal obesity with lower serum vitamin D levels for the abdominal obese participants (P < 0.013).

Table 3.

Prevalence of abdominal obesity among men and women by demographic clinical and lifestyle variables

| Clinical and lifestyle characteristics | Prevalence of abdominal obesity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 291) | Male (n = 124) | Female (n = 167) | P value | |

| Total | 244 (83.8%) | 90 (36.9%) | 154 (63.1%) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 28–51 | 64 (86.5%) | 25 (39.1%) | 39 (60.9%) | 0.770 |

| 52–62 | 114 (78.6%) | 43 (37.7%) | 71 (62.3%) | |

| >62 | 66 (91.7%) | 22 (33.3%) | 44 (66.7%) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 74 (98.7%) | 14 (18.9%) | 60 (81.1%) | <0.001 |

| Married | 170 (78.7%) | 76 (44.7%) | 94 (55.3%) | |

| Educational level | ||||

| Elementary | 55 (90.2%) | 5 (9.1%) | 50 (90.9%) | <0.001 |

| High school | 112 (86.8%) | 27 (24.1%) | 85 (75.9%) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 77 (76.2%) | 58 (75.3%) | 19 (24.7%) | |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Nonsmoker | 178 (80.5%) | 36 (22.2%) | 142 (79.8%) | <0.001 |

| Smoker | 66 (94.3%) | 54 (81.8%) | 12 (18.2%) | |

| Physical activity | ||||

| Yes | 53 (71.6%) | 37 (69.8%) | 16 (30.2%) | <0.001 |

| No | 191 (88%) | 53 (27.7%) | 138 (72.3%) | |

| Metformin | ||||

| Yes | 40 (76.9%) | 15 (37.5%) | 25 (62.5%) | 0.930 |

| No | 204 (85.4%) | 75 (36.8%) | 129 (63.2%) | |

| Sulfonylurea | ||||

| Yes | 9 (75%) | 0 | 9 (100%) | 0.019 |

| No | 235 (84.2%) | 90 (38.3%) | 145 (61.7%) | |

| Abdominal obesity | Serum calcium | |||

| No | 9.62 ± 0.072 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 9.14 ± 0.031 | |||

| Serum vitamin D | ||||

| No | 26.362 ± 3 | 0.013 | ||

| Yes | 18.126 ± 1.33 | |||

Factors associated with abdominal obesity

Table 4 shows the results of binary logistic regression model applied to each demographic and socioeconomic variable separately. This table shows the results for abdominal obesity. The odds ratios (OR) in this table show the magnitude of the association, and their corresponding P values indicate whether the association is statistically significant or not by using the cutoff values of 0.05 as mentioned in the “Materials and Methods” section.

Table 4.

Factors associated with abdominal obesity

| Demographic | Prevalence of abdominal obesity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value | ||

| Gender (Ref. Male) | ||||

| Female | 4.47 | 2.25 | 8.92 | <0.001 |

| Age (Ref. 28–51 years) | ||||

| 52–62 | 0.57 | 0.26 | 1.25 | 0.16 |

| >62 | 12 | 0.59 | 5 | 0.32 |

| Marital status (Ref. married) | ||||

| Singles | 4.8 | 1.67 | 13.84 | 0.004 |

| Educational level (Ref. bachelor’s degree) | ||||

| Elementary | 2.86 | 1.09 | 7.46 | 0.03 |

| High school | 2.05 | 1.03 | 4.08 | 0.04 |

| Smoking status (Ref. nonsmoker) | ||||

| Smoker | 3.99 | 1.38 | 11.54 | 0.011 |

| Physical activity (Ref. yes) | ||||

| No | 2.91 | 1.52 | 5.58 | 0.001 |

| Metformin use (Ref. no) | ||||

| Yes | 0.57 | 0.27 | 1.19 | 0.138 |

| Sulfonylurea use (Ref. no) | ||||

| Yes | 0.56 | 0.15 | 2.16 | 0.40 |

| Serum calcium | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.25 | <0.001 |

| Serum vitamin D | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1 | 0.06 |

In this study, abdominal obesity was significantly associated with female gender (OR, 4.47; 95% CI: 2.25–8.92), being unmarried (OR, 4.8; 95% CI: 1.67–13.84), elementary education holders (OR, 2.86; 95% CI: 1.09–7.46), higher education holders (OR, 2.05; 95% CI: 1.03–4.08), smokers (OR, 3.99; 95% CI: 1.38–11.54), and physically non-active people (OR, 2.91; 95% CI: 1.52–5.58).

Moreover, abdominal obese subjects were more likely to have low serum calcium levels, (OR, 0.08; 95% CI: 0.040–0.170) and (OR, 0.12; 95% CI: 0.06–0.25), respectively.

To select the set of factors that jointly influence the abdominal obesity, we used the stepwise procedure applied to the multiple logistic regression model. The results of this procedure showed that gender, smoking status, physical activity, and serum calcium are jointly highly associated with abdominal obesity. More details are present in Table 5.

Table 5.

Multiple logistic regression model (stepwise procedure) for abdominal obesity

| Independent variables | Abdominal obesity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | OR | 95% CI | P value | ||

| Gender (male) | −1.01 | 0.44 | 0.36 | 0.15 | 0.86 | 0.022 |

| Smoking status (yes) | 1.93 | 0.55 | 6.87 | 2.35 | 20.11 | 0.000 |

| Physical activity (yes) | −0.88 | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.19 | 0.88 | 0.023 |

| Serum calcium | −1.51 | 0.43 | 0.22 | 0.096 | 0.51 | 0.000 |

SE = standard error

Discussion

The incidence of type 2 DM has been continuously rising, leading to serious public health problem. In this study, we studied the relationship between gender, smoking status, physical activity, and serum calcium level with abdominal obesity among patients with type 2 DM to enhance the overall diagnosis and preventing the associated complications by reducing not only the economic burden but also the social burden on the patients.[23] Abdominal obesity was defined by measuring the WC (WC ≥ 80cm in women and ≥94cm in men).[24] Previous studies have shown that a strong direct relation is observed between abdominal fat accumulation and increased incidence of type 2 DM, leading to increased risk of metabolic disorders and insulin resistance,[25,26] which is consistent with our results, where among the men, 90 participants (72.6%) (95% CI: 64.6%–80.5%) were abdominally obese as were 154 participants (92.2%) (95% CI: 88.1%–96.3%) among the women. Overall, 244 participants (83.8%) (95% CI: 79.6%–88.1%) were abdominally obese, the prevalence of abdominal obesity was significantly higher in women (63.1%) than in men (36.9%) (P < 0.001). Similarly, in one of the studies conducted in Germany, the prevalence of obesity was estimated to be 23.9% and it was associated with increased waistline up to 39.5% in which men had an average of 102cm and women 88cm.[27]

WC and BMI measurements serve as important indicators to estimate fat and abdominal mass. Abdominal obesity is well known to be of particular importance in the association and development of type 2 DM as well as other conditions such as cardiovascular diseases and various types of cancer.[28,29] Moreover, this increase in the waistline measurement is highly associated with rising incidence and severity of type 2 DM, which was reported in our study.

The results of this study revealed that serum calcium level of the patients had a significant correlation with their WC measurements, weight, and vitamin D levels. In one of the studies, it was shown that abnormal calcium level is linked to obesity. Similar to this study, a significant correlation between serum ionized calcium level and obesity was reported in some other studies.[30]

In line with the present data, in a study on 908 subjects, the obese individuals were observed to have lower serum calcium levels; similarly, we also found association between abdominal obesity and serum calcium levels, where the abdominal obese subjects were more likely to have low serum calcium levels, (OR, 0.08; 95% CI: 0.040–0.170) and (OR, 0.12; 95% CI: 0.06–0.25), respectively.[31] The average serum vitamin D level of the participants in our study was 19.5 ± 21ng/mL. The same pattern of the results was reported for vitamin D homeostasis, a significant association was observed between the serum vitamin D level and abdominal obesity with lower serum vitamin D level for the abdominal obese participants (P < 0.013). For more details see Figure 1. Throughout most of the previous studies, obesity and vitamin D serum levels were studied and the etiology of lower levels of 25-hydroxy vitamin D in the obese population is not well known yet; it is unlikely to be due to inadequate absorption or low intake of vitamin D. One of the reasons can be a result of reduced sunlight exposure in the morbid obese individuals compared to that in the normal subjects. Another explanation could be that 25-hydroxy vitamin D is stored in fat tissue; hence having less bioavailability, resulting in lower levels of 25-hydroxy vitamin D.[32,33]

Figure 1.

Graphs for abdominal obesity

Our study further confirmed the finding from a previous study in which we found that abdominal obesity was significantly associated with physically non-active people (OR, 2.91; 95% CI: 1.52–5.58).[34] In addition, of the total participants, 228 (78.4%) were nonsmokers, 30 (10.3%) were past smokers, and 33 (11.3%) were current smokers. Our study is in agreement with other findings where the association between abdominal obesity and smoking (OR, 3.99; 95% CI: 1.38–11.54) was found to be significantly high compared with that of nonsmokers.[35,36]

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to estimate the association of abdominal obesity according to WC with serum calcium level among patients with type 2 diabetes in Palestine. This study showed that a high prevalence of abdominal obesity was observed in Palestinian patients diagnosed with type 2 DM. Abdominal obesity is significantly associated with lower serum calcium levels. The high prevalence of abdominal obesity obtained in the study supports the need to promote and implement the utilization of obesity and diabetes screening at the national level.

Study limitations

This was a cross-sectional study, supporting more research of the association of calcium level with WC and biochemical factors in a prospective study. Moreover, the serum calcium levels should be corrected for albumin in future studies.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. About diabetes. Archived from the original on 31 March 2014.

- 2.World Health Organization. Diabetes fact sheet N°312. October 2013. Archived from the original on 26 August 2013.

- 3.Kitabchi AE, Umpierrez GE, Miles JM, Fisher JN. Hyperglycemic crises in adult patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1335–43. doi: 10.2337/dc09-9032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shoback DG, Gardner D. Greenspan’s basic and clinical endocrinology. 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2011. Chapter 17. [Google Scholar]

- 5.RSSDI textbook of diabetes mellitus. Revised 2nd ed. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2012. p. 235. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. The top 10 causes of death fact sheet N°310. October 2013.

- 7.Airaodion AI, Airaodion EO, Ogbuagu EO, Ogbuagu U, Osemwowa EU. Effect of oral intake of African locust bean on fasting blood sugar and lipid profile of Albino Rats. Asian Journal of Research in Biochemistry. 2019;21:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dareen A, Abduelmula A, Moyad S, Monzer S. Evaluation of factors associated with inadequate glycemic control and some other health care indicators among patients with type 2 diabetes in Ramallah, Palestine. Res J Pharm Biol Chem Sci. 2013;4:445–51. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tao Z, Shi A, Zhao J. Epidemiological perspectives of diabetes. Cell biochemistry and biophysics. 2015;73:181–5. doi: 10.1007/s12013-015-0598-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas. 8th ed. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buse JB, Polonsky KS, Burant CF. Type 2 diabetes mellitus In Williams textbook of endocrinology 2011 Jan 1 (pp. 1371-1435) WB Saunders [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi Y, Hu FB. The global implications of diabetes and cancer. Lancet. 2014;383:1947–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60886-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDS) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2163–96. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumanyika S, Jeffery RW, Morabia A, Ritenbaugh C, Antipatis VJ. Obesity prevention: the case for action. Int J Obesity. 2002;26:425. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Colditz G, Liu S, Solomon CG, et al. Diet, lifestyle, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:790–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Field AE, Coakley EH, Must A, Spadano JL, Laird N, Dietz WH, et al. Impact of overweight on the risk of developing common chronic diseases during a 10-year period. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1581–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.13.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Després JP, Lemieux I, Bergeron J, Pibarot P, Mathieu P, Larose E, et al. Abdominal obesity and the metabolic syndrome: contribution to global cardiometabolic risk. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1039–49. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.159228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei M, Gaskill SP, Haffner SM, Stern MP. Waist circumference as the best predictor of noninsulin dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) compared to body mass index, waist/hip ratio and other anthropometric measurements in Mexican Americans—a 7-year prospective study. Obes Res. 1997;5:16–23. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1997.tb00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiss R. Fat distribution and storage: how much, where, and how? Eur J Endocrinol. 2007;157:S39–45. doi: 10.1530/EJE-07-0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institutes of Health. The practical guide: identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. Bethesda, Maryland: National Institutes of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee M, Aronne LJ. Weight management for type 2 diabetes mellitus: global cardiovascular risk reduction. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:68B–79B. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen MD, Haymond MW, Rizza RA, Cryer PE, Miles JM. Influence of body fat distribution on free fatty acid metabolism in obesity. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1168–73. doi: 10.1172/JCI113997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shahwan M, Hassan N, Noshi A, Banu N. Prevalence and risk factors of vitamin B12 deficiency among patients with type 2 diabetes on metformin: a study from northern region of United Arab Emirates. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2018;11:225. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lean ME, Han TS, Morrison CE. Waist circumference as a measure for indicating need for weight management. BMJ. 1995;311:158–61. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6998.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Hu FB. Comparison of abdominal adiposity and overall obesity in predicting risk of type 2 diabetes among men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:555–63. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.3.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R, Leon AS, Skinner JS, Rao DC, et al. Fitness alters the associations of BMI and waist circumference with total and abdominal fat. Obes Res. 2004;12:525–37. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hauner H, Bramlage P, Lösch C, Jöckel KH, Moebus S, Schunkert H, et al. Overweight, obesity and high waist circumference: regional differences in prevalence in primary medical care. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2008;105:827–33. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2008.0827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pischon T, Nöthlings U, Boeing H. Obesity and cancer: symposium on ‘Diet and cancer’. Proc Nutr Soc. 2008;67:128–45. doi: 10.1017/S0029665108006976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuo JF, Hsieh YT, Mao IC, Lin SD, Tu ST, Hsieh MC. The association between body mass index and all-cause mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a 5.5-year prospective analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1398. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lind L, Lithell H, Hvarfner A, Pollare T, Ljunghall S. On the relationships between mineral metabolism, obesity and fat distribution. Eur J Clin Invest. 1993;23:307–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1993.tb00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jafari-Giv Z, Avan A, Hamidi F, Tayefi M, Ghazizadeh H, Ghasemi F, et al. Association of body mass index with serum calcium and phosphate levels. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews. 2019;13:975–80. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2018.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moyad S, Monzer S, Abduelmula A, Kamel A, Dana H. Prevalence and risk factors of vitamin d deficiency among type 2 diabetics and non-diabetic female patients in Jordan. Res J Pharm Biol Chem Sci. 2013;4:278–92. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCarty MF, Thomas CA. PTH excess may promote weight gain by impeding catecholamine-induced lipolysis-implications for the impact of calcium, vitamin D, and alcohol on body weight. Med Hypotheses. 2003;61:535–42. doi: 10.1016/s0306-9877(03)00227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moyad J, Syed K, Sabrina A. Prevalence of diabetic nephropathy and associated risk factors among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in Ramallah, Palestine. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2019;13:1491–6. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2019.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiolero A, Faeh D, Paccaud F, Cornuz J. Consequences of smoking for body weight, body fat distribution, and insulin resistance. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:801–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.4.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Canoy D, Wareham N, Luben R, Welch A, Bingham S, Day N, et al. Cigarette smoking and fat distribution in 21,828 British men and women: a population-based study. Obes Res. 2005;13:1466–75. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]