Abstract

Background

People living with HIV (PLWH) experience higher risk of myocardial infarction (MI) and heart failure (HF) compared with uninfected individuals. Risk of other cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) in PLWH has received less attention.

Methods and Results

We studied 19 798 PLWH and 59 302 age‐ and sex‐matched uninfected individuals identified from the MarketScan Commercial and Medicare databases in the period 2009 to 2015. Incidence of CVDs, including MI, HF, atrial fibrillation, peripheral artery disease, stroke and any CVD‐related hospitalization, were identified using validated algorithms. We used adjusted Cox models to estimate hazard ratios and 95% CIs of CVD end points and performed probabilistic bias analysis to control for unmeasured confounding by race. After a mean follow‐up of 20 months, patients experienced 154 MIs, 223 HF, 93 stroke, 397 atrial fibrillation, 98 peripheral artery disease, and 935 CVD hospitalizations (rates per 1000 person‐years: 1.2, 1.7, 0.7, 3.0, 0.8, and 7.1, respectively). Hazard ratios (95% CI) comparing PLWH with uninfected controls were 1.3 (0.9–1.9) for MI, 3.2 (2.4–4.2) for HF, 2.7 (1.7–4.0) for stroke, 1.2 (1.0–1.5) for atrial fibrillation, 1.1 (0.7–1.7) for peripheral artery disease, and 1.7 (1.5–2.0) for any CVD hospitalization. Adjustment for unmeasured confounding led to similar associations (1.2 [0.8–1.8] for MI, 2.8 [2.0–3.8] for HF, 2.3 [1.5–3.6] for stroke, 1.3 [1.0–1.7] for atrial fibrillation, 0.9 [0.5–1.4] for peripheral artery disease, and 1.6 [1.3–1.9] for CVD hospitalization).

Conclusions

In a large health insurance database, PLWH have an elevated risk of CVD, particularly HF and stroke. With the aging of the HIV population, developing interventions for cardiovascular health promotion and CVD prevention is imperative.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, epidemiology, HIV

Subject Categories: Epidemiology, Cardiovascular Disease, Risk Factors

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Using a large healthcare claims database, we showed that people living with HIV are at increased risk of developing cardiovascular diseases, particularly heart failure and stroke, compared with uninfected individuals.

Risk of atrial fibrillation was also slightly elevated in people living with HIV compared with uninfected individuals.

The association of HIV infection with risk of cardiovascular disease was stronger in younger than older individuals.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

These findings reinforce the importance of primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in people living with HIV.

Additional research needs to evaluate whether specific screening strategies for identification of subclinical cardiovascular disease, including atrial fibrillation, are needed in people living with HIV.

Introduction

The advent and diffusion of combination antiretroviral therapy has led to better survival and reduction of AIDS‐related mortality in people living with HIV (PLWH), with their life expectancy increasing by 9 to 10 years between 1996 and 2010 in high‐income countries.1 As a consequence, morbidity and mortality attributable to aging‐related causes among PLWH are on the rise. Currently, over half of the deaths in PLWH in high income countries are non‐AIDS related.2, 3

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) ranks first as a cause of death in the United States and globally.4 Among PLWH, mortality attributable to CVD is growing in importance. The proportion of deaths attributable to CVD in PLWH in the United States more than doubled between 1999 and 2013, from 2.0% to 4.6%.5 Extensive evidence shows that HIV infection is an independent risk factor for coronary artery disease and, to a lesser extent, heart failure (HF).6, 7 Information on the link between HIV infection and other cardiovascular conditions such as stroke,8, 9 peripheral artery disease (PAD),10 or atrial fibrillation (AF),11 however, remains scarce. Elucidating the impact of HIV infection on a wide range of CVDs will contribute to a more comprehensive characterization of the burden of non‐communicable disorders in PLWH, informing their specific needs for control of CVD risk factors. This is of particular importance given recent findings showing that interventions on traditional cardiovascular risk factors could prevent a substantial proportion of CVD in PLWH.12 In addition, this information can provide support for future work exploring the pathways linking HIV infection and CVD. Thus, we evaluated the association of HIV infection with specific CVDs in a large healthcare administrative database in the United States.

Methods

Study Population

We used data from the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounter Database and the Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits Database (Truven Health Analytics, Ann Arbor, Michigan) for the period of January 1, 2009 through June 30, 2015. These databases include healthcare claims for outpatient services from all levels of care, outpatient pharmacy claims, and enrollment information for individuals enrolled in private health plans or employer‐sponsored Medicare supplemental plans across the United States. The databases include information on >245 million unique patients since 1995. In the most recent full data year, MarketScan contained healthcare data for >43 million covered individuals. Each individual in a MarketScan database is assigned a unique enrollee identifier. The identifier is created by encrypting information provided by data contributors. The population in MarketScan is widely distributed across all regions of the United States and is generally representative of the commercially insured population.13, 14 This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Emory University. A waiver of the informed consent was obtained. The authors cannot make data and study materials available to other investigators for purposes of reproducing the results because of licensing restrictions. Interested parties, however, could obtain and license the data by contacting Truven Health Analytics Inc.

We identified all patients in the MarketScan databases with an HIV diagnosis (see definition below) and at least 12 months of enrollment before the date of HIV diagnosis, without age restrictions. For each HIV case, we selected up to 3 uninfected individuals matched by sex, year of birth, and date of enrollment using a greedy matching without replacement algorithm requiring exact match for all matching variables.15

Definition of HIV Status

We defined HIV infection using the presence of any of the following International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision‐Clinical Modification (ICD‐9‐CM) codes in any claim: 042 (HIV disease), 079.53 (HIV, type 2), 795.71 (non‐specific serologic evidence of HIV), or V08 (asymptomatic HIV infection status).

Outcome Definition

We defined cardiovascular end points applying validated algorithms to diagnostic codes from inpatient and outpatient claims after the date of HIV diagnosis or the corresponding date for uninfected people. Myocardial infarction (MI) was defined as ICD‐9‐CM 410 code as primary diagnosis in an inpatient claim,16 HF as ICD‐9‐CM code 428 in any position in an inpatient claim,17 stroke as ICD‐9‐CM codes 430, 431, 434 or 436 as primary diagnosis in an inpatient claim,18 AF as ICD‐9‐CM codes 427.31 or 427.32 in any position in one inpatient claim or 2 separate outpatient claims,19 and PAD as selected ICD‐9‐CM codes 440, 442, 443 and 444 in any position in an inpatient claim.20 Finally, CVD hospitalization was defined as presence of ICD‐9‐CM codes 390 to 460 as primary diagnosis code in any inpatient claim. Information on mortality is not available in the MarketScan databases. Table S1 includes a detailed list of the codes used for each end point.

Covariates

We used inpatient and outpatient claims up to the time of HIV diagnosis or corresponding date for matched uninfected people to define potential confounders. We considered comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, coronary artery disease, ischemic stroke, HF, AF, PAD, kidney disease, obesity, sleep apnea, liver disease, thyroid disease, drug abuse, alcohol abuse, smoking) and medication use (lipid‐lowering medication, antiplatelet, insulin, oral antidiabetics, diuretics, beta blockers, angiotensin receptor blockers, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, non‐steroid anti‐inflammatory drugs, antidepressants, benzodiazepines). We provide a complete list of ICD‐9‐CM codes used to define each comorbidity in Table S1.

Statistical Analysis

We evaluated the association between HIV infection and risk of each CVD end point using multivariable Cox regression, with separate models for each outcome. Time of follow‐up was defined as the time between HIV diagnosis, or corresponding date for matched uninfected individuals, and occurrence of the study end point, database disenrollment, or September 30, 2015, whichever occurred earlier. An initial model adjusted for age and sex, with an additional analysis including all the covariates defined above. Proportional hazard assumption was explored via inspection of log(‐log(survival)) curves and inclusion of time * HIV status terms in the models. We conducted analyses in the overall sample, among those without any prior history of CVD, and stratified by age (<50, ≥50 years) and sex.

MarketScan does not record information on patient race. Not being able to control for race in this analysis is likely to cause confounding given the higher prevalence of HIV infection among blacks in the United States and the differences in risk of CVD by race.21, 22 To address this limitation, we performed a probabilistic bias analysis to correct for unmeasured confounding following the methodology proposed by Lash and colleagues.23 This method corrects the observed estimates of association based on assumptions about the prevalence of the confounder in exposed and unexposed individuals, and the strength of the association between the confounder and the outcomes. To apply this method, we selected a range of values for the proportion of blacks among HIV‐positive and HIV‐negative patients, and the strength of the association between race and CVD end points. Next, we randomly sampled from this distribution of potential values and corrected the hazard ratio (HR) calculated from the standard analysis using the formula proposed by Schlesselman,24 and further correcting for random variability as recommended by Lash et al25 Finally, we repeated the process 10 000 times and calculated bias‐corrected HRs and 95% CIs as the median, and 2.5 and 97.5 percentiles of the distribution. We performed this process separately for each CVD end point. Data S1 provides details about the methodology, ranges of values for the different parameters (Table S2), as well as justification for those values.

Results

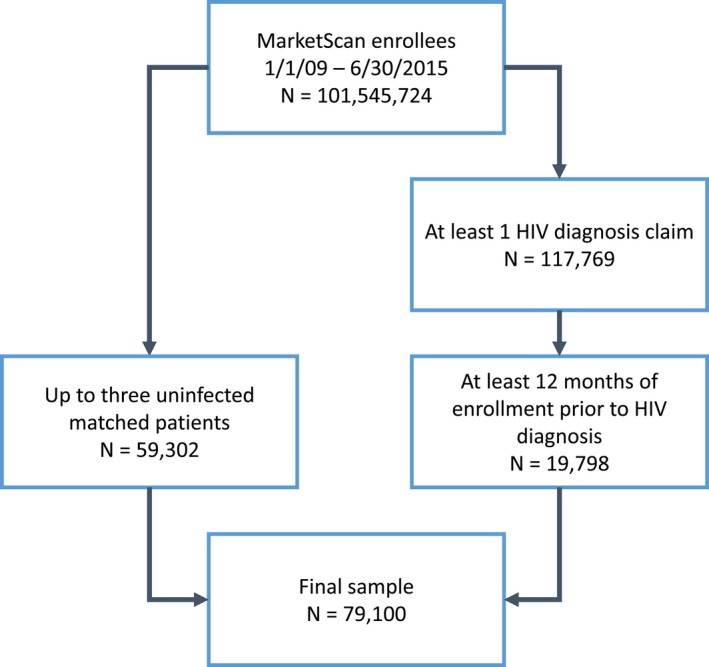

The MarketScan databases included information on 101 545 724 individuals for the period January 1, 2009 through June 30, 2015. Of these, 117 769 had at least one HIV diagnosis claim, with 19 798 of them having at least 12 months of enrollment before HIV diagnosis. We selected up to 3 uninfected people matched to each HIV infected patient. The final sample size included 79 100 patients (59 302 HIV‐negative individuals and 19 798 patients with HIV diagnosis) (Figure 1). Table 1 presents patient characteristics by HIV infection status. By design, age, and sex distribution in both groups was comparable. In contrast, prevalence of most cardiovascular risk factors, prior history of CVD, and use of several cardiovascular medications was higher in HIV positive individuals than in the uninfected controls.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study participants, MarketScan 2009 to 2015.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by HIV Infection Status, MarketScan 2009 to 2015

| HIV‐Infected Patients | Uninfected Controls | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 19 798 | 59 302 |

| Age, y (mean [SD]) | 43 (13) | 43 (13) |

| Women, n (%) | 3826 (19) | 11 467 (19) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 5198 (26) | 13 469 (23) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 1951 (10) | 4826 (8) |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 5432 (27) | 15 447 (26) |

| Smoking, n (%) | 1940 (10) | 3260 (6) |

| Alcohol abuse, n (%) | 547 (3) | 805 (1) |

| Drug abuse, n (%) | 683 (3) | 649 (1) |

| Obesity, n (%) | 1130 (6) | 3219 (5) |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 991 (5) | 2346 (4) |

| Ischemic stroke, n (%) | 698 (4) | 1180 (2) |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 562 (3) | 785 (1) |

| Peripheral artery disease, n (%) | 394 (2) | 780 (1) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 185 (1) | 490 (1) |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 618 (3) | 697 (1) |

| Liver disease, n (%) | 1661 (8) | 1574 (3) |

| Thyroid disease, n (%) | 1416 (7) | 3942 (7) |

| Sleep apnea, n (%) | 836 (4) | 3219 (5) |

| Use of medications: | ||

| ACE inhibitors, n (%) | 1981 (10) | 5553 (9) |

| Angiotensin‐receptor blockers, n (%) | 884 (4) | 2649 (4) |

| Beta blockers, n (%) | 1555 (8) | 4145 (7) |

| Diuretics, n (%) | 1349 (7) | 2893 (5) |

| Oral antidiabetics, n (%) | 948 (5) | 3028 (5) |

| Insulin, n (%) | 373 (2) | 930 (2) |

| Lipid‐lowering medications, n (%) | 2698 (14) | 8908 (15) |

| Antiplatelets, n (%) | 239 (1) | 679 (1) |

| NSAIDs, n (%) | 3411 (17) | 8354 (14) |

| Antidepressants, n (%) | 3221 (16) | 6629 (11) |

| Benzodiazepines, n (%) | 2278 (12) | 3758 (6) |

ACE indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme

The mean (median) follow‐up from index date to disenrollment or September 30, 2015 was 20 (17) months. During follow‐up, 935 patients experienced incident cardiovascular hospitalizations (7.1 cases per 1000 person‐years), 154 myocardial infarction (1.2 per 1000 person‐years), 223 heart failure (1.7 per 1000 person‐years), 98 peripheral artery disease (0.8 per 1000 person‐years), 93 incident strokes (0.7 per 1000 person‐years), and 397 atrial fibrillation (3.0 per 1000 person‐years). Table 2 reports the incident rates of the different cardiovascular events by HIV infection status. The overall rate of CVD hospitalization was 11 per 1000 person‐years among HIV positive and 6 per 1000 person‐years among uninfected individuals. Rates of all individual CVDs were higher among HIV positive than in uninfected individuals.

Table 2.

Incidence Rates of Cardiovascular Endpoints by HIV Infection Status, MarketScan 2009 to 2015

| HIV‐Infected Patients | Uninfected Controls | |

|---|---|---|

| CVD hospitalization | ||

| No. of Events | 359 | 576 |

| Person‐years | 33 394 | 97 449 |

| IR (95% CI)* | 10.8 (9.6–11.9) | 5.9 (5.4–6.4) |

| Myocardial infarction | ||

| No. of events | 46 | 108 |

| Person‐years | 33 873 | 98 135 |

| IR (95% CI)* | 1.4 (1.0–1.8) | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) |

| Heart failure | ||

| No. of events | 116 | 107 |

| Person‐years | 32 939 | 96 897 |

| IR (95% CI)* | 3.5 (2.9–4.2) | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) |

| Stroke | ||

| No. of events | 46 | 47 |

| Person‐years | 33 867 | 98 237 |

| IR (95% CI)* | 1.4 (1.0–1.8) | 0.5 (0.3–0.6) |

| Peripheral artery disease | ||

| No. of events | 30 | 68 |

| Person‐years | 33 304 | 96 942 |

| IR (95% CI)* | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) |

| Atrial fibrillation | ||

| No. of events | 116 | 281 |

| Person‐years | 33 523 | 97 141 |

| IR (95% CI)* | 3.5 (2.8–4.1) | 2.9 (2.6–3.2) |

CVD indicates cardiovascular disease; IR, incidence rate.

Per 1000 person‐years.

After adjustment for age and sex, rates of CVD hospitalization were double in HIV infected patients compared with uninfected controls, with rates of heart failure and stroke at least tripling in HIV infected patients compared with uninfected controls (Table 3, Model 1). In contrast, rates of myocardial infarction, peripheral artery disease, and atrial fibrillation were only 30% to 40% higher in HIV infected patients than controls. Adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors and other potential confounders had only limited impact in the estimates of association, with HR (95% CI) for heart failure, stroke, and CVD hospitalization of 3.2 (2.4–4.2), 2.7 (1.7–4.0), and 1.7 (1.5–2.0), respectively, in HIV infected patients compared with uninfected individuals (Table 3, Model 2). In contrast, HIV infected patients had no or small increased risk of MI (HR 1.3, 95% CI 0.9–1.9), AF (HR 1.2, 95% CI 1.0–1.5) or PAD (HR 1.1, 95% CI 0.7–1.7) compared with uninfected controls. Associations were of a similar magnitude or slightly stronger when the analysis was restricted to individuals without a prior history of CVD (Table S3). Correcting the estimates for unmeasured confounding by race provided similar results, with most associations being slightly attenuated except for that between HIV infection and AF, which was strengthened (Table 3, Model 3). This correction uses available literature to make assumptions about the association of race with CVD risk, and the racial distribution of PLWH and uninfected individuals, as described in Data S1.

Table 3.

Association of HIV infection status with incidence of cardiovascular disease, MarketScan 2009 to 2015

| CVD Hospitalization | Myocardial Infarction | Heart Failure | Stroke | Peripheral Artery Disease | Atrial Fibrillation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 2.0 (1.7–2.2) | 1.3 (0.9–1.9) | 3.5 (2.7–4.6) | 3.0 (2.0–4.5) | 1.4 (0.9–2.1) | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) |

| Model 2 | 1.7 (1.5–2.0) | 1.3 (0.9–1.9) | 3.2 (2.4–4.2) | 2.7 (1.7–4.0) | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) |

| Model 3 | 1.6 (1.3–1.9) | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) | 2.8 (2.0–3.8) | 2.3 (1.5–3.6) | 0.9 (0.5–1.4) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) |

Values correspond to hazard ratios (95% CIs) comparing HIV infected patients with uninfected controls. Model 1: Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for age and sex. Model 2: Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, smoking, alcohol abuse (not in incident stroke model), drug abuse (not in incident peripheral artery disease model), obesity, coronary artery disease, ischemic stroke, heart failure (not in incident heart failure model), peripheral artery disease (not in incident peripheral artery disease model), atrial fibrillation (not in incident atrial fibrillation model), chronic kidney disease, liver disease, thyroid disease, sleep apnea, use of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin‐receptor blockers, beta blockers, diuretics, oral antidiabetics, insulin, lipid‐lowering medications, antiplatelets, NSAIDs, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines. Model 3: Results from Model 2 after performing bias analysis for unmeasured confounding by race. CVD indicates cardiovascular disease.

The associations were of similar magnitude for men and women, but there was some evidence of effect modification in the HR scale by age. In general, associations were stronger among younger individuals (<50) than older ones (≥50 years of age) (Figure 2). This was particularly notable for HF, with an HR (95% CI) of 5.9 (3.4–10.1) in the younger group compared with 2.5 (1.8–3.5) among the older.

Figure 2.

Forest plot presenting associations of HIV infection status with incidence of cardiovascular disease by sex and age group, MarketScan 2009 to 2015. Results from Cox regression models adjusted for all covariates listed in Model 2 of Table 3. HR indicates hazard ratio.

Discussion

In this analysis of a large healthcare claims database, we show that PLWH experience higher rates of several CVDs compared with a group of age and sex‐matched uninfected individuals, independent of cardiovascular risk factors and other comorbidities. The association of HIV infection with CVD was particularly strong for HF, stroke, and a broadly defined outcome of CVD hospitalization, as well as for people aged <50 years and those without a prior history of CVD. In this cohort, PLWH did not have increased risk of PAD and only moderately increased risk of MI and AF. Correcting for unmeasured confounding had a minimal impact on the estimates of association.

The extended use of combination antiretroviral therapy has resulted in longer life expectancy in PLWH. Therefore, rates of other chronic conditions, including CVD, in this population have increased. Multiple studies have shown that PLWH are at particularly increased risk of MI and other manifestations of coronary artery disease. For example, the adjusted HR (95% CI) of MI in PLWH in the Veterans Aging Cohort Study Virtual Cohort (mean age 48 years old, 97% men) compared with uninfected controls was 1.48 (1.27–1.72) in the period 2003 to 2009.26 Our analysis reports a slightly weaker association, consistent with a report from Kaiser Permanente health plans in California suggesting declining relative risks for MI associated with HIV infection in more recent years, from 1.8 (95% CI 1.3–2.6) in 1996 to 1999 to 1.0 (95% CI, 0.7–1.4) in 2010 to 2011.27

The literature on CVD end points in PLWH other than MI is sparser but growing. In the Veterans Aging Cohort Study, HIV infection was associated with increased risk of both HF with reduced ejection fraction (HR 1.6, 95% CI 1.4–1.9) and HF with preserved ejection fraction (HR 1.2, 95% CI 1.0–1.4) compared with no‐infection.28 Consistent with our findings, associations were stronger in younger than older people. Similar observations have been made in a cohort of PLWH and uninfected controls in Chicago, IL, with an HR (95% CI) for HF of 2.1 (1.4–3.2) comparing PLWH with controls.29 Direct HIV‐induced myocardial damage, myocardial inflammation and fibrosis, and some antiretroviral medications are potential mechanisms underlying this association.30 Higher relative risk of HF among younger individuals could be because of a lower baseline risk, in which small absolute increases in risk lead to higher relative ratios, or to higher prevalence of competing causes of HF among older individuals. The few studies that have explored an association between HIV infection and stroke reported increased, but relatively weak, rates of stroke among PLWH compared with uninfected individuals: the pooled risk ratios (95% CI) of any stroke and of ischemic stroke in a meta‐analysis of published studies were 1.82 (1.53–2.16) and 1.27 (1.15–1.39), respectively.31 These results are in contrast to the stronger associations reported in the present analysis. Only 1 previous publication has reported the prospective association of HIV infection with incidence of PAD. Among 91 953 participants in the Veterans Aging Cohort Study, the HR (95% CI) of PAD was 1.19 (1.13–1.25) in PLWH versus uninfected people.10 These results are consistent with the findings from our analysis. Finally, no published studies have compared directly rates of AF in PLWH and uninfected people. An analysis of 30 533 PLWH from the Veterans Affairs HIV Clinical Case Registry reported an incidence of AF of 3.6 events per 1000 person‐years, but no uninfected comparison group was included.11

The present study makes some significant contributions to the extensive literature on the relationship between HIV infection and incidence of CVD. First, it shows that healthcare claims databases are a valuable resource for the epidemiologic study of CVD and other chronic conditions in PLWH. Carefully phenotyped prospective cohorts of PLWH and uninfected people are uniquely suited to answer questions about outcomes associated with HIV infection, but they can be limited by their sample size, geographic restrictions, lack of diversity, or narrow list of disease end points. Large claims databases, despite their known shortcomings, provide large sample size, include patients from wide geographic areas, and reflect the sociodemographic diversity of the general insured population. Second, ours is the first study to compare incidence of AF in PLWH to an uninfected cohort. We report that PLWH had a 40% increased risk of AF compared with uninfected individuals, independent of other cardiovascular risk factors and considering unmeasured confounding. Inflammation associated with HIV infection as well as direct effects of HIV on the atrial myocardium, as shown by studies reporting high prevalence of left atrial enlargement and myocardial fibrosis in PLWH,32, 33 could explain this association. A previous study indicating that markers of HIV infection severity were associated with incident of AF among PLWH indirectly supports a deleterious effect of HIV on AF pathogenesis.11 Third, we assessed a wide range of CVD end points, providing a comprehensive characterization of the cardiovascular risk in this population, and highlighting areas that require particular attention beyond the prevention of coronary artery disease, such as the high rate of HF hospitalization among PLWH. Future research should evaluate the effect that combination antiretroviral therapy has on CVD end points in PLWH. Observational studies suggest that combination antiretroviral therapy may reduce or eliminate the increased risk of CVD observed in PLWH.34

We used bias analysis to evaluate the impact of unmeasured confounding by race in our estimates of association. Risk of HIV and most CVDs is higher among blacks compared with other racial/ethnic groups in the United States, particularly whites.21, 35 Unfortunately, the MarketScan database does not include information on race, restricting our ability to control for this variable. Making reasonable assumptions about the proportion of blacks in PLWH and uninfected people and the association of race with the different CVD end points, and applying well‐established methods, we were able to obtain estimates of association adjusting for unmeasured confounding by race. As expected, estimates for most CVDs were attenuated in the corrected analysis. The only exception was AF, where the association between HIV status and AF risk became stronger. This is expected since, in contrast to other CVDs, rates of AF are lower in blacks than whites,36 and confounding by race would attenuate the true association.

The present analysis has some important strengths including the large patient population, the use of validated algorithms to define CVD end points, the ability to control for a variety of confounders and the use of bias analysis to mitigate the threat of unmeasured confounding. However, certain limitations must be highlighted. First, we relied on claims to define exposures, outcomes and covariates, which can lead to misclassification even when using validated algorithms. Defining incident CVD end points primarily using inpatient claims results in missing milder events not requiring hospitalization, even if the specificity is higher. Additionally, use of claims precludes a more refined classification of cardiovascular events, for example limiting our ability to differentiate between type 1 or type 2 MI, or between different etiologic factors for stroke cases. Lack of information on out‐of‐hospital fatal events also causes outcome misclassification. Second, increased healthcare use among PLWH may contribute to increased ascertainment of CVD outcomes, which could lead to an apparent higher risk of CVD in the HIV infected group. Third, claims are inadequate to evaluate HIV infection severity, since information such as viral load, CD4+ count or compliance with prescribed antiretroviral therapy is not available. Fourth, despite adjusting for numerous covariates and using bias analysis, uncontrolled confounding is likely to remain, including psychological and social risk factors more prevalent among PLWH. Fifth, our study sample is restricted to individuals with commercial or Medicare supplemental insurance in the United States and, thus, results may not generalize to the uninsured, those in other type of insurance plans (e.g. Medicaid), or to people outside the United States. Finally, we only considered first cardiovascular event after the index date, ignoring recurring events afterwards. Future work should evaluate the impact of HIV infection status on risk of recurrent cardiovascular end points.

Conclusion

To conclude, we observed that PLWH are at increased risk of several CVDs. Results from this study can inform future research by highlighting conditions that require increased attention and providing clues on the mechanisms that put PLWH at greater risk for certain CVDs compared with their uninfected counterparts. More work is needed to help with recognition, prevention, and treatment of CVD among PLWH.

Sources of Funding

Dr Alonso is supported by National Institutes of Health grants P30AI050409 (Emory Center for AIDS Research), R01HL122200, and R21AG058445, and American Heart Association grant 16EIA26410001. Dr Shah is supported by National Institutes of Health grant K23HL127251.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Data S1. Supplemental Methods.

Table S1. Diagnosis Codes Used to Define End Points or Covariates in the Study Population

Table S2. Bias Analysis Parameters for Race as an Unmeasured Confounder

Table S3. Association of HIV Infection Status With Incidence of Cardiovascular Disease Among Individuals Without Any History of Cardiovascular Disease, MarketScan 2009 to 2015

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e012241 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012241.)

References

- 1. Collaboration Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort . Survival of HIV‐positive patients starting antiretroviral therapy between 1996 and 2013: a collaborative analysis of cohort studies. Lancet HIV. 2017;4:e349–e356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Collaboration Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort . Causes of death in HIV‐1‐infected patients treated with antiretroviral therapy, 1996‐2006: collaborative analysis of 13 HIV cohort studies. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1387–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Farahani M, Mulinder H, Farahani A, Marlink R. Prevalence and distribution of non‐AIDS causes of death among HIV‐infected individuals receiving antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28:636–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. GBD 2016 Causes of Death Collaborators . Global, regional, and national age‐sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980‐2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1151–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Feinstein MJ, Bahiru E, Achenbach C, Longenecker CT, Hsue P, So‐Armah K, Freiberg MS, Lloyd‐Jones DM. Patterns of cardiovascular mortality for HIV‐infected adults in the United States: 1999 to 2013. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117:214–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kaplan RC, Hanna DB, Kizer JR. Recent insights into cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk among HIV‐infected adults. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2016;13:44–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. So‐Armah K, Freiberg MS. HIV and cardiovascular disease: update on clinical events, special populations, and novel biomarkers. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2018;15:233–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sico JJ, Chang CC, So‐Armah K, Justice AC, Hylek E, Skanderson M, McGinnis K, Kuller LH, Kraemer KL, Rimland D, Bidwell Goetz M, Butt AA, Rodriguez‐Barradas MC, Gibert C, Leaf D, Brown ST, Samet J, Kazis L, Bryant K, Freiberg MS; Veterans Aging Cohort Study . HIV status and the risk of ischemic stroke among men. Neurology. 2015;84:1933–1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marcus JL, Leyden WA, Chao CR, Chow FC, Horberg MA, Hurley LB, Klein DB, Quesenberry CP Jr, Towner WJ, Silverberg MJ. HIV infection and incidence of ischemic stroke. AIDS. 2014;28:1911–1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Beckman JA, Duncan MS, Alcorn CW, So‐Armah K, Butt AA, Goetz MB, Tindle HA, Sico J, Tracy RP, Justice AC, Freiberg MS. Association of HIV infection and risk of peripheral artery disease. Circulation. 2018;138:255–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hsu JC, Li Y, Marcus GM, Hsue PY, Scherzer R, Grunfeld C, Shlipak MG. Atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter in human immunodeficiency virus‐infected persons: incidence, risk factors, and association with marker of HIV disease severity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:2288–2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Althoff KN, Gebo KA, Moore RD, Boyd CM, Justice AC, Wong C, Lucas GM, Klein MB, Kitahata MM, Crane H, Silverberg MJ, Gill MJ, Mathews WC, Dubrow R, Horberg MA, Rabkin CS, Klein DB, Lo Re V, Sterling TR, Desir FA, Lichtenstein K, Willig J, Rachlis AR, Kirk GD, Anastos K, Palella FJ Jr, Thorne JE, Eron J, Jacobson LP, Napravnik S, Achenbach C, Mayor AM, Patel P, Buchacz K, Jing Y, Gange SJ. Contributions of traditional and HIV‐related risk factors on non‐AIDS‐defining cancer, myocardial infarction, and end‐stage liver and renal diseases in adults with HIV in the USA and Canada: a collaboration of cohort studies. Lancet HIV. 2019;6:e93–e104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. IBM Watson Health . IBM MarketScan Research Databases for Health Services Research–White Paper. Somers, NY: IBM; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Claxton JS, Lutsey PL, MacLehose RF, Chen LY, Lewis TT, Alonso A. Geographic disparities in the incidence of stroke among patients with atrial fibrillation in the United States. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019;28:890–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Austin PC. A comparison of 12 algorithms for matching on the propensity score. Stat Med. 2014;33:1057–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cutrona SL, Toh S, Iyer A, Foy S, Daniel GW, Nair VP, Ng D, Butler MG, Boudreau D, Forrow S, Goldberg R, Gore J, McManus D, Racoosin JA, Gurwitz JH. Validation of acute myocardial infarction in the Food and Drug Administration's Mini‐Sentinel program. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22:40–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Loehr LR, Rosamond WD, Chang PP, Folsom AR, Chambless LE. Heart failure incidence and survival (from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study). Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:1016–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Andrade SE, Harrold LR, Tjia J, Cutrona SL, Saczynski JS, Dodd KS, Goldberg RJ, Gurwitz JH. A systematic review of validated methods for identifying cerebrovascular accident or transient ischemic attack using administrative data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(suppl 1):100–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jensen PN, Johnson K, Floyd J, Heckbert SR, Carnahan R, Dublin S. A systematic review of validated methods for identifying atrial fibrillation using administrative data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(suppl 1):141–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hirsch AT, Hartman L, Town RJ, Virnig BA. National health costs of peripheral arterial disease in the Medicare population. Vasc Med. 2008;13:209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . HIV Surveillance Report, 2017. 2018.

- 22. Rosamond WD, Chambless LE, Heiss G, Mosley TH, Coresh J, Whitsel EA, Wagenknecht LE, Ni H, Folsom AR. Twenty‐two‐year trends in incidence of myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease mortality, and case fatality in 4 US communities, 1987‐2008. Circulation. 2012;125:1848–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lash TL, Fox MP, Fink AK. Probabilistic bias analysis In: Lash TL, Fox MP, Fink AK, ed. Applying Quantitative Bias Analysis to Epidemiologic Data. New York, NY: Springer; 2009:117–150. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schlesselman JJ. Assessing effects of confounding variables. Am J Epidemiol. 1978;108:3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lash TL, Fox MP, Fink AK. Applying Quantitative Bias Analysis to Epidemiologic Data. New York, NY: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Freiberg MS, Chang CC, Kuller LH, Skanderson M, Lowy E, Kraemer KL, Butt AA, Bidwell Goetz M, Leaf D, Oursler KA, Rimland D, Rodriguez Barradas M, Brown S, Gibert C, McGinnis K, Crothers K, Sico J, Crane H, Warner A, Gottlieb S, Gottdiener J, Tracy RP, Budoff M, Watson C, Armah KA, Doebler D, Bruyant K, Justice AC. HIV infection and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:614–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Klein DB, Leyden WA, Xu L, Chao CR, Horberg MA, Towner WJ, Hurley LB, Marcus JL, Quesenberry CP Jr, Silverberg MJ. Declining relative risk for myocardial infarction among HIV‐positive compared with HIV‐negative individuals with access to care. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:1278–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Freiberg MS, Chang CH, Skanderson M, Patterson OV, DuVall SK, Brandt CA, So‐Armah KA, Vasan RS, Oursler KA, Gottdiener J, Gottlieb S, Leaf D, Rodriguez‐Barradas M, Tracy RP, Gibert CL, Rimland D, Bedimo RJ, Brown ST, Goetz MB, Warner A, Crothers K, Tindle HA, Alcorn C, Bachmann JM, Justice AC, Butt AA. Association between HIV infection and the risk of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and preserved ejection fraction in the antiretroviral therapy era: results from the Veterans Aging Cohort Study. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:536–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Feinstein MJ, Stevenson AB, Ning H, Pawlowski AE, Schneider D, Ahmad FS, Sanders JM, Sinha A, Nance RM, Achenbach CJ, Christopher Delaney JA, Heckbert SR, Shah SJ, Hanna DB, Hsue PY, Bloomfield GS, Longenecker CT, Crane HM, Lloyd‐Jones DM. Adjudicated heart failure in HIV‐infected and uninfected men and women. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e009985 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Savvoulidis P, Butler J, Kalogeropoulos A. Cardiomyopathy and heart failure in patients with HIV infection. Can J Cardiol. 2019;35:299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gutierrez J, Albuquerque ALA, Falzon L. HIV infection as vascular risk: a systematic review of the literature and meta‐analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0176686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mondy KE, Gottdiener J, Overton ET, Henry K, Bush T, Conley L, Hammer J, Carpenter CC, Kojic E, Patel P, Brooks JT; SUN Study Investigators . High prevalence of echocardiographic abnormalities among HIV‐infected persons in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:378–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thiara DK, Liu CY, Raman F, Mangat S, Purdy JB, Duarte HA, Schmidt N, Hur J, Sibley CT, Bluemke DA, Hadigan C. Abnormal myocardial function is related to myocardial steatosis and diffuse myocardial fibrosis in HIV‐infected adults. J Infect Dis. 2015;212:1544–1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lai YJ, Chen YY, Huang HH, Ko MC, Chen CC, Yen YF. Incidence of cardiovascular diseases in a nationwide HIV/AIDS patient cohort in Taiwan from 2000 to 2014. Epidemiol Infect. 2018;146:2066–2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Das SR, Delling FN, Djousse L, Elkind MSV, Ferguson JF, Fornage M, Jordan LC, Khan SS, Kissela BM, Knutson KL, Kwan TW, Lackland DT, Lewis TT, Lichtman JH, Longenecker CT, Loop MS, Lutsey PL, Martin SS, Matsushita K, Moran AE, Mussolino ME, O'Flaherty M, Pandey A, Perak AM, Rosamond WD, Roth GA, Sampson UKA, Satou GM, Schroeder EB, Shah SH, Spartano NL, Stokes A, Tirschwell DL, Tsao CW, Turakhia MP, VanWagner LB, Wilkins JT, Wong SS, Virani SS; On behalf of the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139:e56–e528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Alonso A, Agarwal SK, Soliman EZ, Ambrose M, Chamberlain AM, Prineas RJ, Folsom AR. Incidence of atrial fibrillation in whites and African‐Americans: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am Heart J. 2009;158:111–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Supplemental Methods.

Table S1. Diagnosis Codes Used to Define End Points or Covariates in the Study Population

Table S2. Bias Analysis Parameters for Race as an Unmeasured Confounder

Table S3. Association of HIV Infection Status With Incidence of Cardiovascular Disease Among Individuals Without Any History of Cardiovascular Disease, MarketScan 2009 to 2015