Abstract

CONTEXT:

Given a large and consistent literature revealing a link between housing and health, abstract publicly supported housing assistance programs might play an important role in promoting the health of disadvantaged children.

OBJECTIVE:

To summarize and evaluate research in which authors examine housing assistance and child health.

DATA SOURCES:

PubMed, Web of Science, PsycInfo, and PAIS (1990–2017).

STUDY SELECTION:

Eligible studies were required to contain assessments of public housing, multifamily housing, or vouchers in relation to a health outcome in children (ages 0–21); we excluded neighborhood mobility interventions.

DATA EXTRACTION:

Study design, sample size, age, location, health outcomes, measurement, program comparisons, analytic approach, covariates, and results.

RESULTS:

We identified 14 studies, including 4 quasi-experimental studies, in which authors examined a range of health outcomes. Across studies, the relationship between housing assistance and child health remains unclear, with ~40% of examined outcomes revealing no association between housing assistance and health. A sizable proportion of observed relationships within the quasi-experimental and association studies were in favor of housing assistance (50.0% and 37.5%, respectively), and negative outcomes were less common and only present among association studies.

LIMITATIONS:

Potential publication bias, majority of studies were cross-sectional, and substantial variation in outcomes, measurement quality, and methods to address confounding.

CONCLUSIONS:

The results underscore a need for rigorous studies in which authors evaluate specific housing assistance programs in relation to child outcomes to establish what types of housing assistance, if any, serve as an effective strategy to reduce disparities and advance equity across the lifespan.

The American Academy of Pediatrics and other national health organizations have called for the development and evaluation of interventions that directly target the social determinants underlying child health disparities.1–4 Given a large and consistent literature revealing a clear link between housing and health,5 housing assistance programs (ie, publicly-supported housing subsidies subject to ongoing public debate6,7 and budgetary threat8–11) might play an important role in promoting the health of disadvantaged children.12,13

Aligned with traditional models linking childhood poverty to health outcomes,14 there are several primary pathways that may connect housing assistance to child health and wellbeing and are as follows: (1) improvements to housing stability15,16 and housing quality,12,17 including the physical or built environment, neighborhood quality,18 and/or a potentially harmful family dynamic19,20; and (2) improvements in housing affordability that allow families to redirect resources toward other health investments (eg, nutrition, physical activity, or health care). Both channels may lead to reduced psychosocial stress for children and parents21–23 and more stable and responsive parenting.24–26 However, programs in which housing assistance is administered may negatively impact child health by segregating low-income populations in poor-access locations27 or underinvesting in housing quality, which may lead to problems with pests, mold, or ventilation.28

Evaluations of US housing assistance programs on child health face a number of empirical challenges, including the following: (1) confounding (because housing assistance is not typically randomized, and unobserved factors that are used to select families to receive US Department of Housing and Urban Development [HUD] assistance may also predispose individuals to relatively poor health29,30), (2) measurement error (because self-reports of housing assistance are often inaccurate for identifying families in assisted housing6,31), and (3) heterogeneous housing assistance programs that vary across locations, which can be difficult to characterize. To date, research on the association between housing assistance and child health in the United States has not been reviewed systematically.

As of 2015, HUD provides housing assistance to ~5 million families, including nearly 4 million children,32 with a cost in excess of $35 billion.33 HUD interacts with local public housing agencies (PHAs) that play a large role in eligibility determination and program administration. HUD assistance is delivered through dozens of programs that are used to serve different goals and populations. Each program generally falls within the following 3 broad categories: public housing, multifamily housing, and housing choice vouchers (see Table 1 for details). Unlike means-tested entitlement programs, like Medicaid, which guarantee benefits to all eligible applicants, HUD programs are subject to annual appropriations, and only ~25% of income-eligible households currently receive assistance.33 HUD housing assistance programs are used to provide benefits that ensure that participating households contribute no more than 30% of their income to rent.

TABLE 1.

Major Housing Assistance Programs Operated by the US Department of HUD

| Program Category | Description | Demographicsa | Program Scope (as of 2014) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public housing | PHA-owned and -operated building; all renters in building are assisted | 31% of households are elderly, 21% are disabled, and 40% include children | $7 billion in federal spending |

| New applicants must have incomes 80% of AMI, and 40% of new applicants must have incomes 30% of AMI | Paid work is the largest source of income for 28% of households | 1.1 million assisted households | |

| Multifamily housing | Privately owned buildings that have a set share of assisted units | 50% of households are elderly, 18% are disabled, and 26% include children | $12 billion in federal spending |

| New applicants must have incomes 50% of AMI, and 40% of new applicants must have incomes 30% of AMI | Paid work is the largest source of income for 16% of households | 1.5 million assisted households | |

| Housing choice voucher program | Provides renters with housing subsidies to acquire housing in the private market | 21% are elderly, 28% are disabled, and 48% include children | $18 billion in federal spending |

| New applicants must have incomes 50% of AMI, and 75% of new applicants have incomes 30% of AMI | Paid work is the largest source of income for 28% of households | 2.2 million assisted households | |

To characterize the existing body of quantitative research, we summarized and evaluated studies in which authors measure the association between housing assistance and child health. A systematic review of existing studies can be used to provide a comprehensive summary of the current evidence and to characterize the quality, consistency, and generalizability of results.36 A summary of evidence is also timely, given recent calls to reduce the HUD budget by ~$6 billion during the next fiscal year.37

METHODS

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines to conduct the systematic review.38

Eligibility Criteria

We required that studies included a statistical comparison (ie, a test statistic or confidence interval [CI]) of at least 1 health outcome between children receiving housing assistance and children not receiving housing assistance in the United States. Eligible studies must have been published in an English-language peer-reviewed journal between January 1990 and December 2017. We defined “health outcome” to include child mental or physical health, including violence and health behaviors. For this review, our definition of health outcome did not include proxies for health, such as neighborhood conditions, number of school absences (for unspecified reasons), cognitive outcomes, health care use, nonviolent criminal behavior, or other proximate determinants of health (eg, food insecurity, blood lead level [BLL]). If a study included multiple outcomes and only some conformed to our definition for this review, we included only the eligible outcomes. We defined “childhood” up to age 21 (to be as inclusive as possible), and we required that the sample was not selected on the basis of a health condition of a parent. To provide a focused review on housing assistance, we excluded studies of neighborhood mobility interventions (eg, Moving to Opportunity [MTO]) that were designed to examine the effect of change in residential context or refurbishment or energy efficiency interventions.

Data Sources and Search Strategy

We conducted an electronic literature search in PubMed, Web of Science, PsycInfo, and PAIS (selected to cover both health and housing journals) from January 1990 through December 2017. We used 1990 as the start date, because the Cranston-Gonzalez National Affordable Housing Act was signed that year, which led to the large-scale dismantling of public housing through Homeownership Opportunities for People Everywhere VI (authorized in 1992). We used Medical Subject Headings of the National Library of Medicine to search in PubMed, and we designed similar searches for the other databases (see Supplemental Table 5). We also searched the reference lists of selected publications and relevant narrative review articles for eligible studies.

Study Selection

Two independent reviewers (N.S. and A.F.) assessed the relevance of studies identified in the databases searches on the basis of title and abstract. Relevant articles were obtained and reviewed for inclusion criteria, and disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Data Extraction

The first author developed and pretested a data extraction form specifically for this study and consulted coauthors as needed during the extraction process. For each identified article, data were extracted for the following: study design (randomized controlled trial [RCT], natural experiment, observational, etc), sample size, age, location, health outcomes, measurement of housing assistance status (eg, self-report, administrative record) and outcomes (eg, parent or self-report, measured), housing assistance program comparisons, analytic approach, covariates, and results.

Quality Assessment

Each of the included studies was evaluated for methodologic quality and assigned an evidence grade to summarize rigorous design features within each study. This scoring system (developed for this review) was informed by established criteria for appraising methods in observational descriptive studies39 and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Methods Guide for Comparative Effectiveness Reviews.40 We rated 4 components central to the internal and external validity of the study, including recruitment, source of housing assistance data, assessment of health outcome, and methodological approach to address confounding.13,29,30,41 One point was awarded for recruitment other than convenience sample, the use of HUD administrative records or direct recruitment from public housing developments (given that self-reports are likely to introduce significant bias6,31), and use of objectively assessed health outcomes (ie, to avoid bias in caregiver- or self-reports42–44). The approach to address potential confounding was rated from 0 to 2 with 1 point given for the use of quasi-experimental designs (ie, instrumental variable estimation [IVE], propensity score matching [PSM], or a waitlist comparison)45,46 and 2 points for RCTs (because RCTs, followed by quasi-experimental designs, have the greatest potential for fair comparisons, relative to association studies).

Data Synthesis

We developed a narrative synthesis of the results; it was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis because of variation in the study designs and outcomes. For each study, we summarized the design characteristics and described the associations observed between housing assistance and the outcomes (significant associations defined at P values <.10, to be inclusive of trends). We also provide a condensed quantitative summary, organized by study design and health outcome.

RESULTS

Search Results and Description of Included Studies

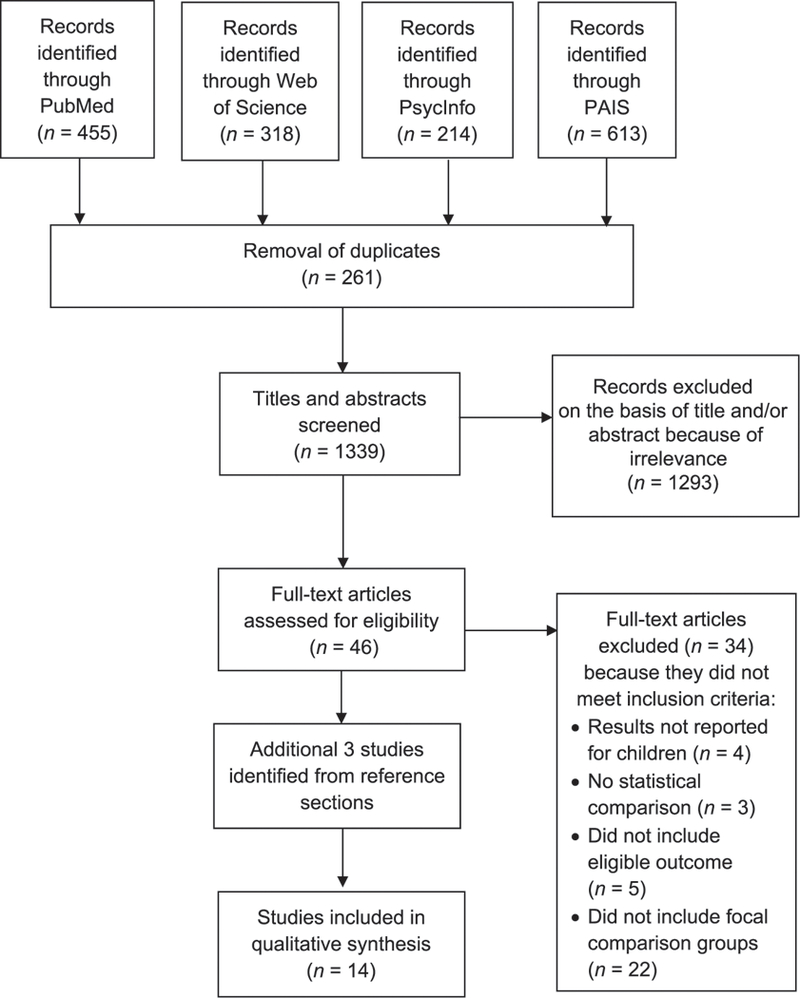

With our database search, we identified 1339 titles. After title and abstract review, 1268 records were discarded because of irrelevance and on the basis of inclusion and exclusion criteria; this large number was due to our broad search terms. Forty-six articles were downloaded for consideration (Fig 1). Eleven articles met all inclusion criteria, and examination of the reference sections of the identified studies led us to identify an additional 3 studies (total n = 14, summarized in Table 2). The studies have been published at a relatively even pace since 1990 (6 between 1990 and 2000,47–52 4 between 2001 and 2010,41,53–55 and 4 since 201113,17,56,57). Four studies were quasi-experimental,13,41,50,57 and the remaining 10 were association studies. No RCTs met criteria for inclusion. Four studies had longitudinal designs.13,17,41,55 Ten of the 14 studies were confined to a relatively small geographic area, whereas 4 studies used either national data13,57 or respondents from 20 major US cities.41,56

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of study selection for the identification of peer-reviewed publications on housing assistance and child health in the United States, January 1990 to December 2017. PAIS, Public Affairs Information Service.

TABLE 2.

Peer-Reviewed Studies of Housing Assistance and Child Health (n = 14)

| Study Characteristics | No. Studies | Total Studies, % |

|---|---|---|

| Y of publication | ||

| 1990–2000 | 6 | 42.9 |

| 2001–2010 | 4 | 28.6 |

| 2011–2017 | 4 | 28.6 |

| Design | ||

| RCT | 0 | 0.0 |

| Quasi-experimentala | 4 | 28.6 |

| Longitudinal or prospective | 2 | 50.0 |

| Cross-sectionalb | 2 | 50.0 |

| Association studiesc | 10 | 71.4 |

| Longitudinal or prospective | 1 | 10.0 |

| Cross-sectionalb | 9 | 90.0 |

| Geography | ||

| Local | 10 | 71.4 |

| Nationald | 4 | 28.6 |

| Recruitment | ||

| Convenience sample | 4 | 28.6 |

| Probability sample | 3 | 21.4 |

| Schools, convenience sample | 1 | 7.1 |

| Schools, probability sample | 1 | 7.1 |

| Ongoing nonprobability cohort or other | 5 | 35.7 |

| Sample size | ||

| <500 | 2 | 14.3 |

| 500–999 | 2 | 14.3 |

| >1000 | 10 | 71.4 |

| Ages representede, y | ||

| 0–6 | 9 | 64.3 |

| 7–14 | 6 | 42.9 |

| 15–21 | 3 | 21.4 |

| Comparisone | ||

| Any housing assistance versus none | 5 | 35.7 |

| Public housing versus none | 9 | 64.3 |

| Voucher versus none | 1 | 7.1 |

| Voucher versus public housing | 1 | 6.7 |

| No. health outcomes examined | ||

| 1 outcome | 4 | 28.6 |

| ≥2 outcomes | 10 | 71.4 |

Includes studies in which PSM, IVE, or waitlist comparison are used.

Includes studies in which authors conducted cross-sectional analyses, even if data are derived from a longitudinal cohort study.

Includes studies in which adjusted regression models to control for potential confounders are used.

Includes studies from the FFCWS, which is not nationally representative but includes children from 20 major US cities.

Categories are not all mutually exclusive; therefore, the number of studies reported across subcategories will be >14.

Convenience samples were used in 4 studies,47,49,50,53 probability samples were used in 3,13,52,57 and samples recruited from schools were used in 2.48,54 The authors of seven studies relied on data from ongoing longitudinal cohorts,13,17,41,51,55–57 including the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS),41,56 the 3 Cities Study17 the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY),57 and the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID).13 The studies were generally large; only 4 studies included <1000 children.13,47,48,50 The identified studies tended to be focused on younger children. Nine studies included children ages 0 to 6 years,17,41,47,49,50,52–54,56 6 studies included children and adolescents ages 7 to 14 years,13,17,48,54,55,57 and 3 studies included individuals 15 to 21 years.17,55,57

Authors of the majority of studies conducted a statistical comparison between either (1) children in households receiving any housing assistance with children receiving no assistance (n = 5)13,17,47,50,53 or (2) children in public housing with children not in public housing (n = 9).41,48,49,51,52,54–57 One study was used to compare children in households receiving vouchers with children not receiving any assistance.57 The most common outcomes were weight status and growth indicators,41,47,50,53,56 followed by general perceived health13,41,53 and violent behaviors.48,55,57 Outcomes with only 1 or 2 studies included emotional and/or behavioral problems,13,17 birth weight,41,49 substance use,51,57 asthma,54 iron deficiency.47 immunization,52 and physical activity.56

Effect of Housing Assistance on Child Health

In the following section, we summarize the results organized by outcome. Details for each study are presented in Table 3, including a description of the comparison population and method to address confounding. With Table 4, we present a condensed summary of the results.

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of Studies Used to Assess Housing Assistance in Relation to Children’s Health Outcomes, January 1990 to December 2017 (n =14, Presented in Chronological Order)

| Study, y | Design | Population (Selection, Location, Age at Baseline) |

Housing Assistance: Assessment and Comparison(s) |

Health Outcome(s) and Mode of Assessment |

Approaches to Address Confounding |

Major Findingsa | Evidence Gradeb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meyers et al47 | Cross-sectional | Convenience sample of 508 children (6 mo to 6 y) from clinic that serves a low-income | Administrative data | Measurement of (1) height-for-age, (2) wt-for-height, (3) | Control for observed variables | No HA associated with greater odds of anemia (OR = 1.8; 95% CI: 0.95–3.39; P = .0695) compared with those with HA | 2 |

| predominantly minority population; Boston, Massachusetts |

HA versus none | wt-for-age, and (4) iron deficiency | No differences for wt or height assessments | ||||

| Meyers et al50 | Cross-sectional, waitlist | Convenience sample of 203 children (<3 y) from pediatric emergency | Caregiver report | Measurement of (1) height-for-age, (2) wt-for- | Control for observed variables | HA associated with higher wt- for-age and wt-for-height z scores compared with those without | 2 |

| department of municipal hospital; Boston, Massachusetts | HA versus no assistance versus waitlist | height, (3) wt-for-age, and (4) low growth | HA waitlist associated with elevated odds of low growth compared with receiving HA (OR = 8.2; 95% CI: 2.2–30.4) | ||||

| indicators | Null results for height-for-age | ||||||

| Shiono et al49 | Cross-sectional | Convenience sample of 1150 newborns from clinic-based sample of pregnant women; 6 clinics in New York, New York, and Chicago, Illinois | Caregiver report PH versus not | Birth wt from medical record review (or maternal report if record not available) | Control for observed variables | PH associated with lower birth wt (unadjusted means: 3326 vs 3385 g, respectively; adjusted b = −0.83; SE = 0.49; P < .10) | 1 |

| Williams et al51 | Cross-sectional | 1264 adolescents (age not reported) enrolled in ongoing study of “inner-city” minority youth; New York, New York | Recruitment within PH PH versus not | Self-reported alcohol involvement | Control for observed variables | PH associated with less alcohol involvement; association modified by race and/ or ethnicity, self-reported grades, and perceived availability of alcohol | 1 |

| Kenyon et al52 | Cross-sectional | Multistage cluster household sample of 1244 children (19–35 mo); Chicago, Illinois | Stratified design to include PH units | Immunization coverage from record data (4:3:1 series = 4 doses of diphtheria- tetanus-pertussis vaccine, | None | PH associated with less 4:3:1 immunization coverage (23% coverage; 95% CI: 18%–28%) compared with those not in PH (strata with high-risk for measles cases in 1980 [45%; 95% CI: 38%–52%] and low-risk for measles cases in 1980 [51%; 95% CI: 43%–60%]) | 3 |

| PH versus not | 3 doses of polio vaccine, and 1 dose of measles- containing vaccine | Children in PH more likely to have no vaccinations (11%; 95% CI: 8%–14%) versus those not in PH (strata with high-risk for measles cases in 1980 [4%; 95% CI: 2%–6%] and low-risk for measles cases in 1980 [2%; 95% CI: 1%–5]) | |||||

| DuRant et al48 | Cross-sectional | 722 children (mean = 11.9 y, SD = 0.8) from 4 middle schools serving neighborhoods in and around PH; Augusta, Georgia | Youth report PH versus not | Self-reported violent behaviors | None | PH associated with higher violent behavior scores compared with those not in PH (unadjusted means: 1.73 (SD = 2.11) vs 1.04 (SD = 2.44), P < .0001) | 0 |

| Ireland et al55 | Longitudinal data, cross-sectional analyses | 1449 youth from the Rochester Youth Development Study and Pittsburgh Youth Study, multiwave stratified probability samples that overrepresent high-risk youth; Rochester New York, and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania | PH versus not | Self-reported violent behaviors | None | PH associated with higher violent behavior compared with those not in PH in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, only; differences most pronounced for youth in large housing developments | 1 |

| Meyers et al53 | Cross-sectional | Convenience sample of 1 1 723 children (<3 y) from low income renter homes recruited from clinics and EDs in 6 sites; Arkansas, California, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, District of Columbia |

Caregiver report HA versus none | Measured wt for age and caregiver report of perceived overall health status | Control for observed variables | No main effect of HA on any outcome Interaction between HA and food insecurity for wt-for-age. Among food insecure families, no HA was associated with a lower wt-for-age z score (−0.025 vs 0.205; P < .001) compared with those with HA | 1 |

| Fertig et al41 | Longitudinal, 3 y follow-up | 22477 children (<3 y) from the FFCWS longitudinal birth cohort, includes overrepresentation of unwed mothers; 20 large US cities | Caregiver report PH versus not | Birth wt from hospital record data, caregiver report of perceived overall health status, and measured BMI | IVE | No robust observation of association between PH and any outcome (observed associations inconsistent across instrumental variable specifications) | 3 |

| Northrldge et al54 | Cross-sectional | 4853 children (5–12 y) from 26 randomly selected elementary schools; New York, New York | Administrative data PH versus not (with 5 subtypes of private housing) | Caregiver report of current asthma | Control for observed variables | Across all types of private housing, children in private housing had lower odds of asthma; this association was only significant in fully adjusted models for elevator private housing (OR = 0.68; 95% CI: 0.50–0.93) | 2 |

| Klmbro et al56 | Cross-sectional | 1975 children (5 y) from the FFCWS longitudinal birth cohort, includes overrepresentation of unwed mothers; 20 US cities | Caregiver report PH versus not |

Measured BMI, caregiver report of outdoor play | Control for observed variables | PH associated with a 13% increase in estimated hours of weekday outdoor play No association for BMI | 2 |

| Leech57 | Cross-sectional | 2530 adolescents (14–19 y) from the NLSY | Caregiver report PH, subsidized housing, no assistance |

Self-report of violence, heavy alcohol or marijuana use, and (3) other drugs |

PSM | Subsidized housing associated with less violence and hard drug use and marginally lower heavy marijuana and/or alcohol use relative to children without HA No differences between children in PH and those without HA | 2 |

| Coley et al17 | Longitudinal, 6 y follow-up | 2437 children (2–21 y) from the 3-City Study cohort recruited from low income neighborhoods; | Caregiver report | Caregiver report of internalizing and externalizing behaviors | Control for observed variables | HA associated with smaller increases in internalizing behaviors over time (0.02 SD lower per y) compared with unassisted children in rental housing | 1 |

| Boston, Massachusetts, Chicago, Illinois, San Antonio, Texas | Housing assistance versus none | Null results for externalizing | |||||

| Newman and Holupka13 | Longitudinal, up to 12 y follow-up | 409 children (6.2 y at baseline) living in assisted housing or matched income-eligible nonrecipients from the PSID | Administrative data | Caregiver report of behavior problems and overall perceived child health | PSM, IVE | Null main effects | 3 |

| HA versus none | Different associations across the distribution of behavior problems in that HA was beneficial for children with the fewest behavior problems (10th percentile) and harmful for those with the worst behavior (>95th percentile) | ||||||

ED, Emergency Department; HA, housing assistance; OR, odds ratio; PH, public housing.

Defined at P value <.10.

Evidence grade (0–5 points) calculated on the basis of the following 4 study characteristics: recruitment other than convenience sample (1 point), use of HUD administrative records or direct recruitment from PH developments (1 point), use of objectively assessed health outcomes (1 point), and advanced approach to address confounding (ie, randomized trial design [2 points] or use of IVE, PSM techniques, or waitlist design [1 point]).

TABLE 4.

Description of Study Outcomes and Summary of Findings, Organized by Study Design (n = 14)

| Health Outcomes | No. Publications Used to Examine Outcome |

No. Specific Outcomes Examined Across Publications |

No. Outcomes That Reveal | Mixed Results Across Outcomesa |

Conditional Associationsb |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Differencec |

Housing Assistance Predicted Better Outcome |

Housing Assistance Predicted Worse Outcome |

|||||

| Quasi-experimental (n = 4) | |||||||

| Wt41,50 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 0 | √ | — |

| Emotion and/or behavior problems13 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | — | √ |

| General perceived health13,41 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | — | — |

| Violence57 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | — | √ |

| Birth wt41 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | — | — |

| Substance use57 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | — | √ |

| Total (all outcomes) | 7 | 12 | 6 (50%) | 6 (50%) | 0 (0%) | — | — |

| Association studies (n = 10) | |||||||

| Wt and growth measures47,53,56 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 0 | — | √ |

| Emotion and/or behavior problems17 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | √ | — |

| General perceived health53 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | — | — |

| Violence48,55 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | — | √ |

| Birth wt49 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | — | — |

| Substance use51 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | — | √ |

| Asthma54 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | — | √ |

| Iron deficiency47 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | — | — |

| Immunization52 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | — | — |

| Outdoor play56 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | — | — |

| Total (all outcomes)d | 13 | 16 | 6 (37.5%) | 6 (37.5%) | 4 (25.0%) | — | — |

For each study, we summarize findings for the highest standard of evidence (eg, results from quasi-experimental tests even if correlational or association results were also included); eg, for Meyers et al,50 we only include the waitlist comparisons, because this resembles quasi-experimental evidence. —, not applicable.

Mixed refers to inconsistent results across specific outcomes examined.

Conditional association refers to studies in which housing assistance is unrelated to the outcome in the overall sample but an association exists only for some subgroup.

Defined at P value < .10.

The total of all outcomes is larger than the number of publications, because some publications examined housing assistance in relation to 2 or more outcomes.

Weight and Other Body Measures

Four cross-sectional studies47,50,53,56 and 1 longitudinal study41 were used to examine housing assistance in relation to child BMI or other anthropomorphic assessments (ie, height-for-age, weight-for-height, weight-for-age). Authors of 3 of the studies did not report significant associations between housing assistance and child weight status or growth indicators,41,47,56 whereas authors of 1 study documented an association in favor of housing assistance for weight-for-age and weight-for-height z scores, with the associations strongest when comparing children receiving housing assistance with those on the waitlist.50 Another study was used to document a conditional association between housing assistance and child growth; housing assistance was associated with greater weight-for- age z scores for infants and young children in food-insecure families but not for children in food-secure families.53

Emotion and/or Behavior Problems

Two longitudinal13,17 studies were used to examine housing assistance in relation to child emotional or behavioral problems. Authors of a longitudinal study who used data from the 3 Cities Study17 which included children and adolescents from low-income neighborhoods in Boston, Chicago, and San Antonio, found children with housing assistance showed smaller increases for internalizing symptoms (eg, anxiety, withdrawal, and somatic complaints) over time compared with children in private rental housing; however, no association was observed for externalizing symptoms (eg, aggression, rule breaking). Authors of a prospective study drawing on data from the PSID (mean age baseline, 6.2 years; 13–17 years at follow-up) found a conditional association whereby housing assistance had no effects on child behavior problems and health outcomes at the mean; however, quantile regression analyses revealed that housing assistance was beneficial for children with the fewest behavior problems and most harmful for those with the worst behavior problems.13

General Perceived Health

Authors of 1 cross-sectional clinic-based study53 and 2 longitudinal studies13,41 examined housing assistance in relation to caregiver report of perceived child health. Authors of all 3 studies reported null associations.41,53

Violence

Three studies were used to examine housing assistance in relation to youth self-reported violent behavior (eg, carrying a weapon, aggravated assault, etc). In a cross-sectional study of children from 4 middle schools in Augusta, Georgia, that serve neighborhoods in and around public housing, bivariate analyses indicated that students in public housing had higher violent behavior scores relative to students not in public housing.48 Authors of a cohort study of youth in Rochester, New York, and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, found elevated self-reported violence participation among youth in public housing compared with those not in public housing in Pittsburgh only,55 and this difference was greatest for youth in large housing developments. In contrast, using data from the NLSY,57 authors of another study found that youth in subsidized housing reported lower rates of violent behavior compared with those not receiving housing assistance; however, this benefit was not evident for youth residing in public housing.

Birth Weight

The 2 studies used to evaluate the association between housing assistance and birth weight had conflicting findings.41,49 In a convenience sample of pregnant women who received prenatal care at selected clinics in New York City and Chicago, residing in public housing was associated with lower birth weight (from medical record or maternal report if record was missing), even after adjustment for potential confounders.49 In contrast, authors of a study drawing on data from FFCWS found no association between public housing and birth weight.41

Substance Use

Authors of 2 cross-sectional studies examined housing assistance in relation to substance use, and, in both, conditional associations were reported.51,57 The authors of a study of 1264 minority youth in and around public housing developments in New York City did not find an overall association between public housing and alcohol involvement (eg, measures of consumption, intensity, self-reported drunkenness) but revealed complex interactions between public housing and (1) race and/or ethnicity, (2) self-reported grades, and (3) perception of alcohol availability for some of the outcomes.51 In a study of 2530 adolescents from the NLSY in which authors employed a PSM methodology to compare heavy alcohol and drug use among youth receiving public housing, receiving subsidized housing (eg, vouchers), and receiving no assistance57 (notably, the only study in which comparison was made across programs), the results were conditional based on the type of housing assistance program. Youth residing in subsidized housing reported lower rates of hard drug use and marginally lower heavy marijuana and/or alcohol use relative to individuals not receiving housing assistance, whereas no differences were observed for comparisons of substance use between youth residing in public housing and those without housing assistance.

Other

Asthma,54 iron deficiency,47 immunizations,52 and outdoor play time56 were each examined only once, and there was mixed evidence for the effect of housing assistance across this set of outcomes. In a cross-sectional study of children from 26 randomly selected elementary schools in New York City, children in private elevator buildings (but not other types of private dwellings) had lower odds of asthma relative to children in public housing, after adjustment for individual and community characteristics.54 Researchers of a cross-sectional convenience sample of children in Boston reported that housing assistance (from administrative records) was associated with reduced risk of iron deficiency.47 A household survey of 1244 parents in Chicago, Illinois, found that immunization coverage was lower among children in public housing compared with children not in public housing.52 A study in which authors used data from the FFCWS cohort at age 5 revealed that public housing was positively associated with hours of weekday outdoor play.56

Evidence Grades and Summary of Results

None of the 14 studies received an evidence grade above 3 out of 5. Three studies received a score of 3,13,41,52 and there was mixed evidence across these studies; no associations were reported in 1 study,41 worse outcomes (immunization coverage) for those in public housing were reported in 1,52 and a conditional protective effect of housing assistance by cognitive performance was reported in 1.13 Six studies received a score of 1 or 0.

As shown in Table 3, for the 12 outcomes evaluated within the 4 quasi-experimental studies, 6 (50.0%) revealed no differences, and 6 revealed health benefits associated with housing assistance or for 1 form of assistance versus another (50.0%). For the 16 specific outcomes examined within the 10 association studies, 6 revealed no differences (37.5%), whereas 6 revealed health benefits associated with housing assistance (37.5%). Notably, only authors of the association studies report that housing assistance may be associated with worse outcomes (4 of the 16 specific outcomes, 25.0%).

DISCUSSION

Key Findings and Recommendations for Future Research

With our systematic review, we identified 14 peer-reviewed articles on housing assistance and child health outcomes (January 1990 to December 2017). Taken together, the evidence for an overall association between housing assistance and child health is mixed, with roughly half of the examined outcomes indicating no association between housing assistance and child health. Approximately 40% of the associations within the quasi-experimental and association studies revealed associations in favor of housing assistance (ie, 6 of 12 outcomes [50%] and 6 of 16 outcomes [37.5%], respectively), and associations disfavoring housing assistance were only reported within association studies (ie, studies most susceptible to confounding). Although some of the association studies included extensive control variables, they often lacked a plausible counterfactual comparison needed for causal inference.58

We excluded studies of housing mobility interventions (such as MTO) to focus specifically on the effects of housing assistance. Studies of housing mobility programs tend to be concentrated on neighborhood disorder and disadvantage in impacting the economic status and well-being of families, in which authors emphasize the differences between traditional public housing and housing voucher programs. Despite the more narrow focus of mobility interventions compared with our review of housing assistance, they do provide some insights into the role that housing interventions play in child health. Similar to the complex patterns within the present review, the effects of housing mobility interventions on child health are also unclear and vary on the basis of sex, family socioeconomic status, and age at relocation.59–61 Considering child health outcomes 4 to 7 years after randomization in the MTO housing voucher experiment, relocation to a low poverty neighborhood had a harmful effect for self-reported asthma,62 risky behaviors, elevated depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and conduct disorders for boys but not girls.63–65 In contrast, MTO had a positive effect on conduct disorder and substance use among girls, but not boys.63–65 Importantly, although an RCT is the optimal study design for generating causal evidence, recent studies indicate that both observational studies and RCT are susceptible to bias associated with “individualized treatment selection”60 (given that prerandomization characteristics can be used to predict treatment). For example, in MTO, baseline child health was associated with 40% lower odds of moving to a low poverty neighborhood upon randomization (odds ratio = 0.62; 95% CI = 0.42–0.91) and predicted selection into lower income neighborhoods among those who did move to a low-poverty neighborhood.66 Accordingly, innovative strategies to address selection bias within observational studies on the effect of housing assistance are urgently needed.23

With our review, we also excluded studies of housing assistance and health indicators that did not qualify as health outcomes, including BLLs and health care use. Notably, there appears to be mixed evidence for the association between housing assistance and these health indicators as well.67–71 Authors of a recent study that was used to link children in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey to HUD records (restricted to children with family income-to-poverty ratios <200%) documented a clear benefit of housing assistance whereby children in assisted housing had lower BLLs relative to children without housing assistance.69 Authors of two large studies used to examine housing assistance in relation to health service use or expenditures53,71 (including an RCT study of housing vouchers) reported null associations.

To advance our understanding of housing assistance and child health, more research is needed to establish if (1) there are positive or negative health effects for specific types or classes of child health outcomes (given the inconsistency we observed within and across categories of outcomes), (2) effects vary on the basis of individual13,51 and family characteristics53 or type of housing assistance program,23,57 and (3) there are latent effects and/or long-term impacts of housing assistance during early childhood that extend to adolescence and adulthood.72 There is evidence of long-run economic effects of the type of housing assistance interventions we reviewed72,73 and from the MTO neighborhood mobility intervention.74,75 Among the reviewed studies, only 1 was used to compare outcomes across multiple housing assistance programs (eg, public housing versus vouchers),57 and the authors found differences by program type, thereby emphasizing the importance of future research to identify which programs may be most beneficial for healthy child development.oooh,

To improve causal estimates of the impact of housing assistance on child health, priorities for future research include the following:(1) examination of housing assistance programs separately because each type of program may have differential effects,23,57 (2) measurement of housing assistance participation from administrative records, and (3) application of techniques to account for unobserved differences between assisted and nonassisted households (eg, events or conditions that both prompt a need for housing assistance and that affect child outcomes) using IVE, PSM, robust longitudinal modeling approaches, such as fixed effects, and natural experiments, such as local PHA lotteries or waitlist designs.76 Such an agenda would produce actionable insights that would inform housing assistance programs and the health of disadvantaged children.

Limitations of This Systematic Review

Several limitations of this review are important to consider. First, because of publication bias, studies with null findings are likely to be underrepresented.77 Second, as described above, many of the included studies had insufficient methods to address confounding, the majority of studies were cross-sectional, and there were few studies on the same child health outcome, which limits our ability to identify potentially consistent patterns that may be limited to a specific health outcome. As a strategy to enhance the use of this review, we applied an evidence grade to each study in order to highlight those studies with methodologic strengths; however, this grading system is only intended to emphasize rigorous measurement and analytical aspects of existing research, rather than quantifying evidence of causal inference. In spite of these limitations, the convergence of (1) substantial government spending on housing assistance,33 (2) the US housing affordability crisis,78 and (3) the magnitude of child health disparities in the United States79–81 underscore the importance of a systematic assessment of the current state of evidence about how housing assistance is linked to child health.

Implications for Policy and Practice

Both public health and pediatric practice prioritize health promotion and disease prevention, and increasingly, primary health care providers for children are aware of the early life origins of many adult diseases and how these diseases are shaped by early environmental influences,3,80,82,83 which include safe and affordable housing. As described in pediatric guidelines, as well as in a recent American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement,3,84,85 an important role for pediatricians is to supplement typical developmental evaluations with attention to ecological and community characteristics that threaten or enrich healthy child development.85,86 Children and families have tangible benefits from referral for basic unmet needs and social determinants of health.85–87 For example, an RCT at 8 urban community health centers in Boston, Massachusetts, revealed that referring children for social determinants of health at pediatric well-care visits was associated with increased receipt of community-based resources for unmet basic needs, including lower odds of being in a homeless shelter.85 If future researchers indicate that housing assistance is an effective strategy to improve child health, practitioners may decide to embed services to connect eligible families to housing assistance.

CONCLUSIONS

With this review, we provide mixed evidence about the association between housing assistance and child health. Although a substantial portion of the results indicate no difference, authors of a number of studies suggest that receipt of housing assistance is associated with health benefits for children, and authors of relatively few studies (who do not adequately control for potential confounding) indicate that housing assistance is associated with worse outcomes. Taken together, we view these data as promising and as modest evidence that socioeconomic disparities in certain child health outcomes could be attenuated via expanded and enhanced housing assistance policies. Most importantly, the results underscore the need for additional rigorous studies in which researchers carefully evaluate specific housing assistance programs in relation to a broad range of child health outcomes to establish what types of housing assistance, if any, can be used to serve as an effective strategy to reduce disparities and advance health equity across the lifespan.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FUNDING: Supported by a seed grant from the Maryland Population Research Center.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BLL

blood lead level

- CI

confidence interval

- FFCWS

Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study

- HUD

Housing and Urban Development

- IVE

instrumental variable estimation

- MTO

Moving to Opportunity

- NLSY

National Longitudinal Survey of Youth

- PHA

public housing agency

- PSID

Panel Study of Income Dynamics

- PSM

propensity score matching

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

Footnotes

Dr Slopen conceptualized the systematic review, performed the electronic search, evaluated articles for eligibility, extracted relevant data, interpreted the results, and drafted sections of the manuscript; Dr Fenelon conceptualized the systematic review, evaluated articles for eligibility, extracted relevant data, and drafted sections of the manuscript; Dr Newman interpreted the results, provided a critical review of the manuscript, and assisted with revisions; Dr Boudreaux conceptualized the systematic review, interpreted the results, and drafted sections of the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Academies of Sciences and Medicine. A Framework for Educating Health Professionals to Address the Social Determinants of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woolf SH, Braveman P. Where health disparities begin: the role of social and economic determinants–and why current policies may make matters worse. Health Aff(Millwood). 2011;30(10):1852–1859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garner AS, Shonkoff JP; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care; Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: translating developmental science into lifelong health. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/129/1/e224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Council on Community Pediatrics. Poverty and child health in the United States. Pediatrics. 2016;137(4):e20160339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaw M. Housing and public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25:397–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shroder M Does housing assistance perversely affect self-sufficiency? A review essay. J Hous Econ. 2002;11(4):381–417 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albright L, Derickson ES, Massey DS. Do affordable housing projects harm suburban communities? Crime, property values, and taxes in Mount Laurel, NJ. City Community. 2013;12(2):89–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reiss DJ. Trump’s budget proposal is bad news for housing across the nation. The Hill. March 16, 2017. Available at: http://thehill.com/blogs/pundits-blog/economy-budget/324211-how-trumps-budget-cuts-could-affect-housing-for-thousands. Accessed June 30, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Theodos B, Stacy CP, Ho H. Taking stock of the community development block grant. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Editorial Board. Show HUD’s budget cuts the door.New York Times. May 30, 2017:A20 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koh HK, Restuccia R. Housing as health. JAMA. 2018;319(1):12–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leventhal T, Newman S. Housing and child development. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2010;32(9):1165–1174 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newman S, Holupka CS. The effects of assisted housing on child well-being. Am J Community Psychol. 2016;60(1,2): 66–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duncan GJ. Give us this day our daily breadth. Child Dev. 2012;83(1):6–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crowley S The affordable housing crisis: residential mobility of poor families and school mobility of poor children. J Negro Educ. 2003;72(1):22–38 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jelleyman T, Spencer N. Residential mobility in childhood and health outcomes: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(7):584–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coley RL, Leventhal T, Lynch AD, Kull M. Relations between housing characteristics and the well-being of low-income children and adolescents. Dev Psychol. 2013;49(9):1775–1789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen QC, Acevedo-Garcia D, Schmidt NM, Osypuk TL. The effects of a housing mobility experiment on participants’ residential environments. Hous Policy Debate. 2017;27(3):419–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker CK, Billhardt KA, Warren J, Rollins C, Glass NE. Domestic violence, housing instability, and homelessness: a review of housing policies and program practices for meeting the needs of survivors. Aggress Violent Behav. 2010;15(6):430–439 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holt S, Buckley H, Whelan S. The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: a review of the literature. Child Abuse Negl. 2008;32(8):797–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newman SJ. Does housing matter for poor families? A critical summary of research and issues still to be resolved. J Policy Anal Manage. 2008;27(4):895–925 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garg A, Burrell L, Tripodis Y, Goodman E, Brooks-Gunn J, Duggan AK. Maternal mental health during children’s first year of life: association with receipt of section 8 rental assistance. Hous Policy Debate. 2013;23(2):281–297 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fenelon A, Mayne P, Simon AE, et al. Housing assistance programs and adult health in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(4):571–578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mensah FK, Kiernan KE. Parents’ mental health and children’s cognitive and social development: families in England in the Millennium Cohort Study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45(11):1023–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gladstone BM, Boydell KM, McKeever P. Recasting research into children’s experiences of parental mental illness: beyond risk and resilience. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(10):2540–2550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith M Parental mental health: disruptions to parenting and outcomes for children. Child Fam Soc Work. 2004;9(1):3–11 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Talen E, Koschinsky J. The neighborhood quality of subsidized housing. J Am Plann Assoc. 2014;80(1):67–82 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adamkiewicz G, Spengler JD, Harley AE, et al. Environmental conditions in low-income urban housing: clustering and associations with self-reported health. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(9):1650–1656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hinds AM, Bechtel B, Distasio J, Roos LL, Lix LM. Health and social predictors of applications to public housing: a population-based analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70(12):1229–1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Popkin SJ, Edin K. No Simple Solutions: Transforming Public Housing in Chicago. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers; 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Susin S Longitudinal outcomes of subsidized housing recipients in matched survey and administrative data. Cityscape. 2005;8(2):189–218 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Fact sheet: federal rental assistance. 2017. Available at: www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/4-13-11hous-US.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2017

- 33.Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Policy Basics: Federal Rental Assistance. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 34.US Department of Health and Human Services.Programs of HUD: Major Mortgage, Grant, Assistance, and Regulatory Programs.Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Congressional Budget Office. Federal Housing Assistance for Low-Income Households.Washington, DC: United States Congressional Budget Office [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mulrow CD. Rationale for systematic reviews. BMJ. 1994;309(6954):597–599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woellert L HUD budget slashes housing programs, drawing protests from advocates. Politico (Pavia). 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loney PL, Chambers LW, Bennett KJ, Roberts JG, Stratford PW. Critical appraisal of the health research literature: prevalence or incidence of a health problem. Chronic Dis Can. 1998;19(4):170–176 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berkman ND, Lohr KN, Ansari M, et al. Grading the strength of a body of evidence when assessing health care interventions for the effective health care program of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: an update In: Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fertig AR, Reingold DA. Public housing, health and health behaviors: is there a connection? J Policy Anal Manage. 2007;26(4):831–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maoz H, Goldstein T, Goldstein BI, et al. The effects of parental mood on reports of their children’s psychopathology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(10): 1111–1122.e5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Youngstrom E, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Patterns and correlates of agreement between parent, teacher, and male adolescent ratings of externalizing and internalizing problems. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(6):1038–1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huybrechts I, Himes JH, Ottevaere C, et al. Validity of parent-reported weight and height of preschool children measured at home or estimated without home measurement: a validation study. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cook TD. Quasi Experimental Design In: Cooper CL, Flood PC, Freeney Y, eds. Wiley Encyclopedia of Management. Hoobken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meyers A, Rubin D, Napoleone M, Nichols K. Public housing subsidies may improve poor children’s nutrition. Am J Public Health. 1993;83(1):115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Durant RH, Altman D, Wolfson M, Barkin S, Kreiter S, Krowchuk D. Exposure to violence and victimization, depression, substance use, and the use of violence by young adolescents. J Pediatr. 2000;137(5):707–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shiono PH, Rauh VA, Park M, Lederman SA, Zuskar D. Ethnic differences in birthweight: the role of lifestyle and other factors. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(5):787–793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meyers A, Frank DA, Roos N, et al. Housing subsidies and pediatric undernutrition. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149(10):1079–1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Williams C, Scheier LM, Botvin GJ, Baker E, Miller N. Risk factors for alcohol use among inner-city minority youth: a comparative analysis of youth living in public and conventional housing. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 1997;6(1):69–89 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kenyon TA, Matuck MA, Stroh G. Persistent low immunization coverage among inner-city preschool children despite access to free vaccine. Pediatrics. 1998;101(4 pt 1):612–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meyers A, Cutts D, Frank DA, et al. Subsidized housing and children’s nutritional status: data from a multisite surveillance study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(6):551–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Northridge J, Ramirez OF, Stingone JA, Claudio L. The role of housing type and housing quality in urban children with asthma. J Urban Health. 2010;87(2):211–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ireland TO, Thornberry TP, Loeber R. Violence among adolescents living in public housing: a two-site analysis. Criminol Public Policy. 2003;3(1):3–38 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kimbro RT, Brooks-Gunn J, McLanahan S. Young children in urban areas: links among neighborhood characteristics, weight status, outdoor play, and television watching. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(5):668–676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leech TGJ. Subsidized housing, public housing, and adolescent violence and substance use. Youth Soc. 2012;44(2):217–235 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Evans GW, Wells NM, Moch A. Housing and mental health: a review of the evidence and a methodological and conceptual critique. J Soc Issues. 2003;59(3):475–500 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nguyen QC, Schmidt NM, Glymour MM, Rehkopf DH, Osypuk TL. Were the mental health benefits of a housing mobility intervention larger for adolescents in higher socioeconomic status families? Health Place. 2013;23:79–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Glymour MM, Nguyen QC, Matsouaka R, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Schmidt NM, Osypuk TL. Does mother know best? Treatment adherence as a function of anticipated treatment benefit. Epidemiology. 2016;27(2):265–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nguyen QC, Rehkopf DH, Schmidt NM, Osypuk TL. Heterogeneous effects of housing vouchers on the mental health of US adolescents. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):755–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schmidt NM, Lincoln AK, Nguyen QC, Acevedo-Garcia D, Osypuk TL. Examining mediators of housing mobility on adolescent asthma: results from a housing voucher experiment. Soc Sci Med. 2014;107:136–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schmidt NM, Glymour MM, Osypuk TL. Adolescence is a sensitive period for housing mobility to influence risky behaviors: an experimental design. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60(4):431–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kessler RC, Duncan GJ, Gennetian LA, et al. Associations of housing mobility interventions for children in high-poverty neighborhoods with subsequent mental disorders during adolescence [retraction in: JAMA. 2016;316(2):227–228]. JAMA. 2014;311(9):937–948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 65.Kessler RC, Duncan GJ, Gennetian LA, et al. Notice of retraction and replacement: Kessler RC, et al. Associations of housing mobility interventions for children in high-poverty neighborhoods with subsequent mental disorders during adolescence. JAMA. 2014;311 (9):937–947. JAMA. 2016;316(2):227–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 66.Arcaya MC, Graif C, Waters MC, Subramanian SV. Health selection into neighborhoods among families in the moving to opportunity program. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;1 83(2):130–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rabito FA, Shorter C, White LE. Lead levels among children who live in public housing. Epidemiology. 2003;14(3):263–268 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mielke HW, Gonzales CR, Mielke PW Jr. The continuing impact of lead dust on children’s blood lead: comparison of public and private properties in New Orleans. Environ Res. 2011;111(8):1164–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ahrens KA, Haley BA, Rossen LM, Lloyd PC, Aoki Y. Housing assistance and blood lead levels: children in the United States, 2005–2012. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(11):2049–2056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mielke HW, Gonzales CR, Powell ET, Mielke PW. Spatiotemporal exposome dynamics of soil lead and children’s blood lead pre- and ten years post-Hurricane Katrina: lead and other metals on public and private properties in the city of New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S.A. Environ Res. 2017;155:208–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jacob BA, Kapustin M, Ludwig J. The impact of housing assistance on child outcomes: evidence from a randomized housing lottery. Q J Econ. 2015;130(1):465–506 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Newman SJ, Harkness JM. The long-term effects of public housing on self-sufficiency. J Policy Anal Manage. 2002;21(1):21–43 [Google Scholar]

- 73.Andersson F, Haltiwanger JC, Kutzbach MJ, Palloni GE, Pollakowski HO, Weinberg DH. Childhood Housing and Adult Earnings: A Between-Siblings Analysis of Housing Vouchers and Public Housing. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chyn E Moved to Opportunity: The Long-Run Effect of Public Housing Demolition on Labor Market Outcomes of Children. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan; 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chetty R, Hendren N, Katz LF. The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: new evidence from the moving to opportunity experiment. Am Econ Rev. 2016;106(4):855–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Garboden PM, Leventhal T, Newman S. Estimating the effects of residential mobility: a methodological note. J Soc Serv Res. 2017;43(2):246–261 [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dickersin K The existence of publication bias and risk factors for its occurrence. JAMA. 1990;263(10):1385–1389 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schwartz AF. Housing Policy in the United States. New York, NY: Routledge; 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Braveman P What is health equity: and how does a life-course approach take us further toward it? Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(2):366–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shonkoff JP, Boyce WT, McEwen BS. Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. JAMA. 2009;301 (21):2252–2259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Braveman P, Barclay C. Health disparities beginning in childhood: a life-course perspective. Pediatrics. 2009;124(suppl 3):S163–S175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Slopen N, Koenen KC, Kubzansky LD. Childhood adversity and immune and inflammatory biomarkers associated with cardiovascular risk in youth: a systematic review. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26(2):239–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Slopen N, Goodman E, Koenen KC, Kubzansky LD. Socioeconomic and other social stressors and biomarkers of cardiometabolic risk in youth: a systematic review of less studied risk factors. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e64418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shonkoff JP, Garner AS; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care; Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/129/1/e232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, Silverstein M, Freeman E. Addressing social determinants of health at well child care visits: a cluster RCT. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/135/2/e296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Garg A, Marino M, Vikani AR, Solomon BS. Addressing families’ unmet social needs within pediatric primary care: the health leads model. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2012;51(12):1191–1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Garg A, Boynton-Jarrett R, Dworkin PH. Avoiding the unintended consequences of screening for social determinants of health. JAMA. 2016;316(8):813–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.