Abstract

Wounds, burns, cuts, and scarring may cause a serious problem for human health if left untreated, and medicinal plants are identified as potentially useful for wound healing. Therefore, the study focused on ethnophytotherapy practices for wound healing from an unexplored area, Pakistan. Ethnophytotherapeutic information was collected through well-planned questionnaire and interview methods by targeting 80 informants (70 males and 10 females), in the study area. Data was analyzed through quantitative tools like use value (UV) and credibility level (CL). A total of forty wound healing plant species, belonging to twenty-nine families, were being used in forty-six recipes. Herbs constitute (35%), shrubs (30%), trees (30%), and climbers (5%) in the treatment of multiple human injuries. For remedies preparations, leaves were most frequently utilized (52%) followed by whole plant, flowers, twigs, roots, bulb, bark, rhizome, resin, oil, leaf gel, latex, gum, and creeper. The most form of herbal preparation was powder (34.7%) and poultice (32.6%), followed by decoction, bandaged and crushed, in which 40% internally and 60 % externally applied. The drugs from these plants seem to be widely used to cure wounds: Acacia modesta, Aloe barbadensis, Azadirachta indica, Ficus benghalensis, Nerium oleander, and Olea ferruginea with higher use values (0.75). Local people are still connected with ethnophytotherapies practices for curing wounds for several reasons. This ethnomedicine and the wound healing plants are under severe threats; thus conservation must be considered. Further research should be directed towards implementing pharmacological activity on these invaluable botanical drugs.

1. Introduction

Plants as medicine play an important role in the public health sector across the world. Patients have been utilizing medicinal plants for a long time to fulfill different daily needs and to maintain well-being [1]. Plants provide people with food, medicines, and fodder for livestock, as well as materials for construction of houses [2]. The history of discovery and use of different medicinal plants is as old as the history of discovery and use of plants for food [3]. From the history, it was revealed that the ancient people used herbal medicine for treatment of various diseases including burn injury, due to its simplicity, low cost, and affordable basis [4]. Today, the injury is a serious health problem across the world, often associated with high-costs and inefficient therapies [5] and affect people both physically and psychologically [6]. It is estimated that several million patients suffer from wounds, burns, and cuts every year, which may result in death when they did not get treated properly [7, 8]. Wound infections and related diseases are very common in developing and some developed countries due to unhygienic conditions [9, 10]. Wounds can be referred to as physical disabilities [11] and are marked as injury to normal skin structural, anatomical, physiological, and functional variation [12]. World Health Organization (WHO) 2018 data estimated that 180 000 people died every year due to burn injuries, and the vast majority of these deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries. Many medical plants support natural repairing process of skin [13, 14]. As described in the different literature, 70% of the wound healing drugs are of plant origin, 20% of mineral origin, and the remaining 10% consisting of animal products [15].

So, by keeping in view the importance of phytotherapies for wound healing, our study was conducted with the aims (i) to unveil the valuable wounds healing plants from District Haripur, KPK, Pakistan, as previously this area was unexplored in this regard, (ii) to record traditional folk knowledge and phytotherapies being used in wound healing practices, (iii) to record wound healing medicinal plants with highest use value (UV) and credibility level (CL) for further in vitro investigations, (iv) to identify potential threats, and (v) to provide baseline data for phytochemists, pharmacologists, and conservationists for further future study.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Area

Haripur district is situated in Hazara division of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan (Figure 1) at latitude 33°-44′ to 34°-22′ and longitude 72°-35′ to 73°-15′ and about 610 meters above the sea level. A total area of the district is 1725 square kilometers. Haripur was founded in 1822 by Hari singh Nalva, a Sikh General of Ranjit Singh's army. He was the Governor of Kashmir in 1822-23 A.D. after whom it is named. District Haripur has three tehsils, namely, Khanpur, Ghazi, and Haripur. The whole district is subdivided into 45 Union Councils (UCs). According to National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS), the estimated population of the district was 857,000, in 2008, having population density of 497 persons per square kilometer. The district is predominantly a rural district where only 12% population lives in urban areas. Agriculture is the main source of livelihood of rural population of the district. Haripur district has distinct geographical significance as its boundaries touch Districts Mansehra, Abbottabad, Torghar, Buner, Swabi, Attock, Rawalpindi, and Federal capital Islamabad [16].

Figure 1.

Map of study area in Pakistan.

2.2. Field Survey

The whole study area was frequently visited and the main target sites in the study area were Khanpur, Garmthun, Najafpur, Dartian, Babotri, Baghpur dehri, Kohala, Nilan Bhoto, Jabri, Hattar, Kotnajibullah, Khalabat, Beer, Ghazi, Nara Amazai, etc. A field survey was aimed to collect field data and activities like (i) recording folk knowledge and phytotherapies being used in wound healing practices, (ii) plant's collection, (iii) local information about plants, (iv) identification of potential threats, (v) photography, etc. This survey was completed through well-planned questionnaires, interviews, and keen observations. Questionnaire method was also helpful in the documentation of folk indigenous knowledge. The interviews were helpful in investigation of local people and knowledgeable persons (farmers and herdsmen), who are mainly connected with plants and involved in traditional health care. During the field visits, total of 80 informants were approached randomly for questionnaires and interviews. Their description with respect to age, education, profession, etc. is given in (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants.

| By age | 10-20 years | 20-30 years | 30-40 years | 40-50 years | 50-60 years | Above 60 years | % |

| Male | 0 | 05 | 10 | 15 | 18 | 22 | 87.5 % |

| Female | --- | --- | --- | 03 | 04 | 03 | 12.5 % |

| Total | --- | (6.2%) | (12.5%) | (22.5%) | (27.5%) | (31.2%) | --- |

| By qualification | Illiterate | Primary | Middle | Secondary | Higher secondary | Higher education | % |

| Male | 16 | 18 | 14 | 14 | 06 | 02 | 87.5 % |

| Female | 05 | 03 | 02 | --- | --- | --- | 12.5 % |

| Total | (26.2%) | (26.2%) | (20%) | (17.5%) | (7.5%) | (2.5%) | --- |

| By profession | Farmers | Herdsmen (nomadic) | Hakeem | Teachers | Shop-keeper | Laborers | % |

| Male | 45 | 15 | 03 | 02 | 02 | 03 | 87.5 % |

| Female | 08 | 02 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 12.5 % |

| Total | (66.2%) | (21.2%) | (3.7%) | (2.5%) | (2.5%) | (3.7%) | --- |

2.3. Plant Collection and Identification

The plant specimens collected were authenticated using the international plant name index (http://www.ipni.org), the plant list (www.theplantlist.org), and GRIN taxonomy site (http://www.ars-grin.gov/cgi-bin/npgs/html/queries.pl). The life form of investigated plants was categorized into herbs, shrubs, grasses, and trees (annual, biennial, or perennial), according to the system modified by Brown [17]. The collected plant specimens were identified by Prof. Dr. Ghulam Mujtaba Shah (Plant Taxonomist), Hazara University Mansehra (Pakistan), and by using Flora of West Pakistan [18] and Flora of Punjab [19]. The voucher specimens were deposited in the Herbarium, Department of Botany, Hazara University, Mansehra (Pakistan).

2.4. Identification of Potential Threats

During field survey, potential threats were identified through well-planned questionnaires, interviews, and keen observations. Therefore, the data obtained were tabulated and supported by photography. The main aim of the photography was to support field data with evidence. Photography of study area, as well as important plants and potential threats, was taken.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The ethnophytotherapeutic data was statistically analyzed using Microsoft Office Excel software (2010). The use value (UV) of plant species were also determined [1, 20].

Use value (UV) determines the relative importance of uses of plant species. It is calculated using the following formula:

| (1) |

where “UV” indicates use value of individual species, “U” is the number of uses recoded for that species, and “N” represents the number of informants who reported that species.

Credibility level (CL) of plant species: to determine credibility level of plants, a simple statistical tool was developed given name “credibility level” (CL). First of all, those plants are chosen which were reported by more than five informants with the same use. Then each plant was evaluated under the following formula:

| (2) |

where “CL” indicates credibility level of plant species, “N” is the number of informants recorded for this plant, and “ƩN” represents the total number of informants for all plant species. CL value of each plant was tabulated in ascending series. The higher CL value is the most credibility of the medical plant used as ethnomedicine among communities in the study area.

3. Results

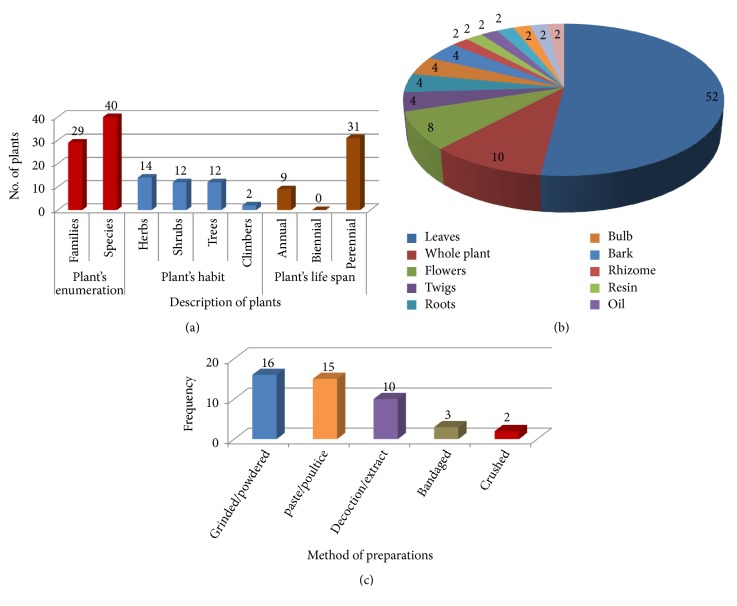

During the present study, data on 40 medicinal plant species belonging to 29 families that are being used in wound healing phytotherapies were collected from the study area. From those, herbs (35%) were the most widely used by local patients to treat various injury problems in the study areas of Haripur, followed by shrubs (30%), trees (30%), and climber species (5%) in which there were (22.5%) annual and (77.5%) perennial plant species as shown in Figure 2(a). Detailed information about each plant pertaining to the botanical name, voucher number, local name, family, habit, lifespan, locality, plant parts used, ethnophytotherapies, number of informants, etc. is listed in Table 2. People of District Haripur use different parts of the plants for wound healing phytotherapies as shown in Figure 2(b). Among those plant parts, leaves were the most frequently used (52%) followed by whole plant (10%), flowers (8%), twigs, roots, bulb and bark (4% each) and rhizome, resin, oil, leaf gel, latex, gum, and creeper (2% each).

Figure 2.

(a) Description of medicinal plants; (b) type of botanical parts; (c) methods of herbal drug preparation used for wound healing in the study area.

Table 2.

Ethnophytotherapies for wounds healing in District Haripur.

| No | Botanical Name/Voucher No. | Local Name | Family | Habit | Life span | Locality | Part Used | Ethno-Phytotherapies | No. of informants | U.V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Acacia modesta Wall. 01-Z |

Phulai | Leguminosae | Tree | Perennial | Dartian | Twigs, bark & leaves | For gum bleedings: Twigs are used as masvak. For mouth boils: Decoction of bark is gargled several times a day. For abscesses, boils & adulthood poxes: Half spoon powdered leaves are taken with water for a few days. | 04 | 0.75 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 2 |

Acacia nilotica (L.) Delile 02-Z |

Kikar | Leguminosae | Tree | Perennial | Najafpur | Flowers, leaves & gum | Formouth ulcer: spoon of powdered flowers and leaves are taken with water in morning and evening. For stomach ulcer: 1/4th spoon of powdered gum is taken with milk or water. | 04 | 0.5 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 3 |

Achyranthes aspera L. 03-Z |

Puth-Kanda, Lehndi booti | Amaranthaceae | Herb | Perennial | Khanpur | Leaves | For wound washing & healing: Decoction of leaves is used for washing the wounds and then poultice of leaves is applied. | 05 | 0.4 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 4 |

Adhatoda vasica Nees 05-Z |

Bhaikur, aroosa | Acanthaceae | Shrub | Perennial | Halli | Leaves | For pimples: 1/2 cup of leaves juice is taken 2 times a day. For skin wounds: Powdered leaves are applied topically. | 08 | 0.25 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 5 |

Allium cepa L. 08-Z |

Payaz | Amaryllidaceae | Herb | Perrenial | Khanpur | Bulb | For wound healing: Inner bulb scale is heated in mustard oil and bandaged on wounds. | 02 | 0.5 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 6 |

Allium sativum L. 09-Z |

Thoom | Amaryllidaceae | Herb | Annual | Khanpur | Bulb | For animal and insect bites: Grinded in vinegar and made into a paste and applied. | 08 | 0.12 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 7 |

Aloe vera (L.) Burm.f. 10-Z |

Kanwar-ghandal | Xanthorrhoeaceae | Herb | Perennial | Dara | Leaf gel | For burn, wounds and other skin problems: Gel of leaves is burnt over the fry pan and applied topically. | 04 | 0.75 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 8 |

Althaea officinalis L. 11-Z |

Khatmi | Malvaceae | Herb | Annual | Halli | Flowers & leaves | For skin burns: Powdered flowers and leaves are applied. | 04 | 0.25 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 9 |

Amaranthus viridis L. 12-Z |

Chaleray | Amaranthaceae | Herb | Annual | Jabri | Leaves | For healing of boils & abscesses: The upper surfaces of leaves are smeared with mustard oil, warmed gently and bandaged. | 06 | 0.33 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 10 |

Azadirachta indica A.Juss. 13-Z |

Nim | Meliaceae | Tree | Perennial | Bagla | Leaves | For skin pimples, boils & abscesses: Leaves are dipped in water at night. In morning one spoon of this water is taken. | 04 | 0.75 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 11 | Berberis lycium Royle14-Z | Simbulu | Berberidaceae | Shrub | Perennial | Dartian | Root | For mouth boils & internal wounds: 1/4th spoon of dried powdered root is taken with water. | 10 | 0.2 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 12 |

Bombax ceiba L. 15-Z |

Sumbal | Malvaceae | Tree | Perennial | Daboola | Stem bark | For wound healing: Bark paste is applied topically. | 02 | 0.5 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 13 |

Cannabis sativa L. 21-Z |

Pang, bhang | Cannabaceae | Sub shrub | Annual | Hattar | Leaves | For wounds: Leaves are bound over the wounds. | 02 | 0.5 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 14 |

Cissampelos pareira L. 22-Z |

Phalaan jarhi, Ghora-sum | Menispermaceae | Climer | Perennial | Najafpur | Leaves | For wounds & itching: Crushed leaves are applied. | 06 | 0.3 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 15 |

Curcuma longa L. 31-Z |

Haldi | Zingiberaceae | Herb | Perennial | Khanpur | Rhizome | For internal wounds: One spoon of dried grounded rhizome is mixed in one cup of hot milk and taken at night. | 07 | 0.14 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 16 | Cuscuta reflexa Roxb.33-Z | Bail | Convolvulaceae | Climber | Perennial | Najafpur | Creepers | For pimples & wounds: Creeper is crushed after boiling and tied over. | 05 | 0.4 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 17 |

Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. 40-Z |

Khabal | Poaceae | Herb | Perennial | Nara Amazai | Whole plant | For nose and wound bleedings: Paste of whole plant is applied. | 08 | 0.25 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 18 |

Dodonaea viscosa (L.) Jacq. 55-Z |

Sanatha | Sapindaceae | Shrub | Perennial | Garam Thoon | Leaves | For skin boils & wounds: Powdered leaves are applied. | 13 | 0.15 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 19 |

Eucalyptus globulus Labill. 58-Z |

Gond | Myrtaceae | Tree | Perennial | Khanpur | Oil | For skin wounds & fungal infections: Massage of Eucalyptus oil is useful. | 08 | 0.25 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 20 |

Ficus benghalensis L. 86-Z |

Bohr | Moraceae | Tree | Perennial | Bandi | Leaves | For pimples, acne & rashes: Paste of leaves is applied. | 04 | 0.75 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 21 |

Ficus carica L. 90-Z |

Anjeer | Moraceae | Tree | Perennial | Daboola | Milky latex | For wounds healing: Milky latex is applied twice a day. | 05 | 0.2 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 22 |

Lantana camara L. 106-Z |

--- | Verbenaceae | Shrub | Perennial | Hattar | Leaves & twigs | For wounds swelling: Decoction of leaves is applied. | 02 | 0.5 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 23 |

Lawsonia inermis L. 109-Z |

Mehendi | Lythraceae | Tree | Perennial | Sarhadna | Leaves | For wounds: Leaf is grounded into paste and applied to get relief from burning sensation. | 02 | 0.5 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 24 | Malvastrum coromandelianum (L.) Garcke111-Z | Dhamni boti | Malvaceae | Sub shrub | Annual or biennial | Najafpur | Leaves | For ringworms & wounds: Paste of leaves is applied. | 03 | 0.66 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 25 | Melia azedarach L.124-Z | Daraik, bakain | Meliaceae | Tree | Perennial | Sarhadna | Leaves | For skin pimples: 1/2 cup of leaves juice is taken in morning. For burns: Fresh leaf extract is applied externally. | 11 | 0.18 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 26 | Mentha arvensis L.130-Z | Podina | Lamiaceae | Herb | Perennial | Mankrai | Leaves | For insect bites wound: Leaves are grinded and bruised and applied topically. | 08 | 0.12 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 27 |

Morus nigra L. 145-Z |

Kala toot, she-toot | Moraceae | Tree | Perennial | Dara | Leaves | For snake bite: Leaf extract is applied. | 03 | 0.33 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 28 | Nasturtium officinale R.Br. 150-Z | Tara meera | Brassicaceae | Herb | Perennial | Khanpur | Leaves | For skin allergies & pimples: 1/4th spoon of dried powdered leaves are taken with water daily. | 03 | 0.66 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 29 | Nerium oleander L.162-Z | Kundair | Apocynaceae | Shrub | Perennial | Najafpur | Leaves & roots | For scabies and skin swellings: Decoction of leaves is directly applied. For scorpion bite: Root paste is applied over the wound. | 04 | 0.75 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 30 |

Ocimum basilicum L. 164-Z |

Niaz-bo | Lamiaceae | Herb | Annual | Khanpur | Leaves | For insect bite wounds: powdered leaves are rubbed. | 03 | 0.33 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 31 | Olea europaea subsp. cuspidata (Wall. & G.Don) Cif. 170-Z | Kaho | Oleaceae | Tree | Perennial | Choi | Leaves & twigs | For skin boils and pimples: 1 cup of leaf tea is taken once in a day. For mouth boils: Young twigs are chewed under the teeth. | 04 | 0.75 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 32 | Rydingia limbata (Benth.) Scheen & V.A.Albert. 173-Z | Chita kanda, bamboli | Lamiaceae | Shrub | Perennial | Najafpur | Whole plant | For wounds: Whole plant is powdered, mixed in butter and applied. | 02 | 0.5 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 33 | Oxalis corniculata L. 178-Z | Khat-matra | Oxalidaceae | Herb | Annual | Halli | Leaves | For skin inflammations: Powdered leaves are applied as a poultice. | 04 | 0.25 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 34 | Pinus roxburghii Sarg. 180-Z | Chir | Pinaceae | Tree | Perennial | Muslimabad | Resin | For skin burns, boils & wounds: Resin is applied externally. | 06 | 0.5 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 35 |

Punica granatum L. 195-Z |

Daruna | Lythraceae | Shrub | Perennial | Barkote | Flowers | For gum bleedings: Dried powdered flowers are used as tooth powder. | 09 | 0.11 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 36 | Rumex hastatus D. Don 206-Z | Katmat, tehtur | Polygonaceae | Shrub | Perennial | Najafpur | Leaves | For wounds: Leaves paste is applied. | 02 | 0.5 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 37 | Solanum americanum Mill. | Kach mach | Solanaceae | Herb | Annual | Joulian | Whole plant | For wound and boils: Whole plant paste is applied externally as a poultice. | 05 | 0.4 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 38 | Solanum surattense Burm. f. 240-Z | Mohkree | Solanaceae | Herb | Annual | Khoi Kaman | Whole plant | For skin infection: Dried powdered plant is applied topically. | 13 | 0.07 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 39 |

Woodfordia fruticosa (L.) Kurz. 256-Z |

Taawi, dhawi | Lythraceae | Shrub | Perennial | Najafpur | Leaves | For skin wounds: Poultice of leaves is applied externally. | 06 | 0.16 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 40 | Ziziphus nummularia (Burm.f.) Wight & Arn.282-Z | Beri | Rhamnaceae | Shrub | Perennial | Sarahdna | Leaves | For wounds: Leaf paste is applied over the wounds. For mouth & gum bleedings: Leaves are boiled in water, and gargled several times a day. | 05 | 0.4 |

The methods of preparation for 46 recorded recipes fall into 5 categories, viz., plant parts used as decoction/extract (21.7%), Grinded/powdered form (34.7%), paste/poultice (32.6%), crushed (4.3%), and bandaged (6.5%) as shown in Figure 2(c).

Study also revealed that local people use wound healing phytotherapies both internally and externally. These treatments involve 40% internal and 60 % external use. Use value (UV) of plant species was also calculated in order to determine the relative importance of plant in study area with respect to usage. Results showed that Acacia modesta, Aloe barbadensis, Azadirachta indica, Ficus benghalensis, Nerium oleander, and Olea ferruginea have higher use values (UVs), i.e., 0.75, while species Solanum surattense, Punica granatum, Mentha arvensis, and Allium sativum have lower use values (UVs), i.e., 0.07, 0.11, 0.12, and 0.12, respectively, as shown in Table 2. CL value was also calculated to check the credibility of plants used in study area. CL values obtained are given in Table 3. The higher CL value is the most credibility of plant used as ethnomedicine among District Haripur communities. Results showed that 20 plants in study area are more credible in efficacy than others. Of these the highest CL value was recorded for Dodonaea viscosa, i.e., 16.25; hence it is the most credible, in contrast to Ziziphus nummularia which showed the lowest CL value i.e., 6.25, among these 20 plant species in study area.

Table 3.

Credibility level (CL) value for herbal drugs.

| No | Botanical Name | Local Name | Locality | Part Used | Used against | C.L Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dodonaea viscosa (L.) Jacq. | Sanatha | Garam Thoon | Leaves | Skin boils & wounds | 16.25 |

| 2 | Solanum surattense Burm. f. | Mohkree | Khoi Kaman | Whole plant | Skin infection | 16.25 |

| 3 | Melia azedarach L. | Daraik, bakain | Sarhadna | Leaves | Skin pimples & burns | 13.75 |

| 4 | Berberis lycium Royle | Simbulu | Dartian | Root | Mouth boils & internal wounds | 12.5 |

| 5 | Punica granatum L. | Daruna | Barkote | Flowers | Gum bleedings | 11.25 |

| 6 | Adhatoda vasica Nees | Bhaikur, aroosa | Halli | Leaves | For pimples & skin wounds | 10 |

| 7 | Allium sativum L | Thoom | Khanpur | Bulb | Animal and insect bites | 10 |

| 8 | Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. | Khabal | Nara Amazai | Whole plant | Nose & wound bleedings | 10 |

| 9 | Eucalyptus globulus Labill. | Gond | Khanpur | Oil | Skin wounds & fungal infections | 10 |

| 10 | Mentha arvensis L. | Podina | Mankrai | Leaves | Insect bites wound | 10 |

| 11 | Curcuma longa L. | Haldi | Khanpur | Rhizome | Internal wounds | 8.75 |

| 12 | Amaranthus viridis L. | Chaleray | Jabri | Leaves | Healing of boils & abscesses | 7.5 |

| 13 | Cissampelos pareira L. | Phalaan jarhi, Ghora-sum | Najafpur | Leaves | Wounds & itching | 7.5 |

| 14 | Pinus roxburghii Sarg. | Chir | Muslimabad | Resin | Skin burns, boils & wounds | 7.5 |

| 15 | Woodfordia fruticosa (L.) Kurz. | Taawi, dhawi | Najafpur | Leaves | Skin wounds | 7.5 |

| 16 | Achyranthes aspera L. | Puth-Kanda, Lehndi booti | Khanpur | Leaves | Wound washing & healing | 6.25 |

| 17 | Cuscuta reflexa Roxb | Bail | Najafpur | Creepers | Pimples & wounds | 6.25 |

| 18 | Ficus carica L. | Anjeer | Daboola | Milky latex | Wounds healing | 6.25 |

| 19 | Solanum americanum Mill. | Kach mach | Joulian | Whole plant | Wound and boils | 6.25 |

| 20 | Ziziphus nummularia (Burm.f.) Wight & Arn. | Beri | Sarahdna | Leaves | Wounds and mouth & gum bleedings | 6.25 |

During the study, it was also explored that plant resources of District Haripur are under severe threats. The major threats identified were subsequent forest fires during the summer, over grazing (normal and nomadic), overexploitation, mining activities, etc. as shown in Table 4. The important indigenous knowledge of plants is being confined to the older people mostly, as the young generations has little interest in such traditional practices and mainly because of transforming lifestyle and culture among the youth. This can be deduced from the informant's description by age showing that there were only 6.2% informants below 30 years of age.

Table 4.

Major threats to the wound healing plants in the study area.

| Locality/Threat | Fire | Over grazing (nomadic) | Over exploitation (Cutting etc.) | Mining activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khanpur | + | + | - | + |

| Garmthun | + | + | + | + |

| Najafpur | + | + | + | + |

| Dartian | + | + | + | + |

| Babotri | + | + | + | - |

| Baghpur dehri | + | + | + | + |

| Kohala | + | + | - | + |

| Nilan Bhoto | - | + | + | - |

| Jabri | + | + | + | + |

| Hattar | + | + | - | - |

| Sarae Nehmat Khan | - | + | - | - |

| Pharala | - | + | + | + |

| Beer | + | + | + | - |

| Ghazi | - | + | - | - |

| Nara Amazai | - | + | + | - |

4. Discussion

Since time immemorial, people have been used various parts of plants and its extracts in the treatment and prevention of many ailments [21]. This knowledge varies from region to region and from the community to community according to the presence of herbs and their historical uses [22]. In similar investigates, many other researchers [23–26] have significantly explored wound healing medicinal plants from other parts of the world. This is also confirmed by several other studies showing that herbs and plant organ leaves could be a major herbal remedy considered for many human ailments around the world including wounds and burns [27]. Many of these herbal medicines are used for wound healing in the form of (teas, decoctions, tinctures, syrups, oils, ointments, poultices, and infusions), as a safe and reliable natural substance derived from medicinal herbs [28].

Comparative analysis shows that ethnophytotherapies for wound healings in District Haripur may or may not be similar in use with the other published literature reported from various other parts of the world. For example, present use of leaf juice of Melia azedarach is used to cure pimples and burns, while Ahmad [29] reported that this plant is beneficial against scabies, carbuncles, and abscess in district Attock. In Indian traditional medicine, species of the following genera are commonly used to treat wound and related injuries; Abutilon, Achyranthes, Acorus, Aegle, Aerva, Aloe, Azadirachta, Bambusa, Bidens, Boerhaavia, Butea, Caesalpinia, Calotropis, Carissa, Cassia, Cucumis, Curcuma, Cynodon, Datura, Dodonaea, Eclipta, Euphorbia, Ficus, Hyptis, Lantana, Leucas, Morinda, Ocimum, Opuntia, Pavetta, Pergularia, Plumbago, Pongamia, Sida, Smilax, Terminalia, Tridax, Vitex, and Zizyphus [30]. Pistacia atlantica subsp. kurdica Zohary can be used externally to treat skin injury as well as internally for abdominal pain [31]. A review of the previously published literature shows that the most species display a range of pharmacological activities that are suggested to have wound healing potential. For example, Acacia modesta has anti-inflammatory properties [32]. Ocimum basilicum holds antibacterial activity [33, 34]. Berberis lyceum retains antifungal properties [35, 36]. In rats, methanolic extract ointment from leaves of Adhatoda vasica had significant wound healing activity compared to standard drug [37]. A study by Ahmed [1] showed the importance of Allium sativum for antidandruff, intestinal worms, blood circulation, rheumatism, stimulant, cancer, cholera, alopecia areata, tuberculosis, and plague in Kurdistan region of Iraq, while in our study the same species was used to treat wounds by insect. The same author reported Althaea officinalis to treat burns in the form of poultice, which is exactly similar to our results. This is due to that fact that there may be several factors playing a role in establishing knowledge of ethnobotany and ethnomedicine particularly in rural areas, such as phytogeographical and ecological characteristics, demographic and ethnic structure as well [28]. This comparative analysis strengthens the value of the wound healing knowledge from our study location for further future studies.

5. Conclusion

Plant extracts have been demonstrated as important potential herbal remedies in many traditional medicinal systems around the world for wound repair and tissue regeneration. People of District Haripur (study area) rely mainly on ethnophytotherapies for wound healing. This is because of traditional culture, easy availability, and cheaper source of herbal medicines. Local people have sufficient knowledge about wound healing practices and saved mostly by older informants. In the study area both the wound healing, medicinal plants, and folk traditional knowledge are getting depleted thus conservation is required to maintain this valuable natural resource. Further pharmacological studies are recommended to validate the current herbal traditional knowledge.

Acknowledgments

We do appreciate the assistance from local informants and their sharing knowledge for public.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Authors' Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and have read and approved it for publication.

References

- 1.Ahmed H. M. Ethnopharmacobotanical study on the medicinal plants used by herbalists in Sulaymaniyah Province, Kurdistan, Iraq. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2016;12(1, article no. 8) doi: 10.1186/s13002-016-0081-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shinwari M. I., Khan M. A. Folk use of medicinal herbs of margalla hills National Park, Islamabad. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2000;69(1):45–56. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(99)00135-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ibrar M. Responsibilities of ethnobotanists in the field of medicinal plants. Proceeding of the Workshop on Curriculum Development in Applied Ethnobotany; 2002; Ethnobotany Project, WWF Pakistan; pp. 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sher H., Al-yemeni M. N., Wijaya L. Ethnobotanical and antibacterial potential of Salvadora persica l: a well known medicinal plant in Arab and Unani system of medicine. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research. 2011;5(7):1224–1229. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agyare C., Boakye Y. D., Bekoe E. O., Hensel A., Dapaah S. O., Appiah T. Review: african medicinal plants with wound healing properties. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2016;177:85–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gümüş K., Özlü Z. K. The effect of a beeswax, olive oil and Alkanna tinctoria (L.) Tausch mixture on burn injuries: an experimental study with a control group. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2017;34:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alam G., Singh M. P., Singh A. Wound healing potential of some medicinal plants. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Review and Research. 2011;9(1):136–145. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y., Beekman J., Hew J., et al. Burn injury: challenges and advances in burn wound healing, infection, pain and scarring. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2018;123:3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2017.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menke N. B., Ward K. R., Witten T. M., Bonchev D. G., Diegelmann R. F. Impaired wound healing. Clinics in Dermatology. 2007;25(1):19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finnerty C. C., Jeschke M. G., Branski L. K., Barret J. P., Dziewulski P., Herndon D. N. Hypertrophic scarring: the greatest unmet challenge after burn injury. The Lancet. 2016;388(10052):1427–1436. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31406-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strodtbeck F. Physiology of wound healing. Newborn and Infant Nursing Reviews. 2001;1(1):43–52. doi: 10.1053/nbin.2001.23176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shenoy C., Patil M. B., Kumar R., Patil S. Preliminary phytochemical investigation and wound healing activity of Allium cepa linn (Liliaceae) International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2009;(2):167–175. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar B., Vijayakumar M., Govindarajan R., Pushpangadan P. Ethnopharmacological approaches to wound healing—exploring medicinal plants of India. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2007;114(2):103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Das U., Behera S. S., Pramanik K. Ethno-herbal-medico in wound repair: an incisive review. Phytotherapy Research. 2017;31(4):579–590. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biswas T. K., Mukherjee B. Plant medicines of Indian origin for wound healing activity: a review. The International Journal of Lower Extremity Wounds. 2003;2(1):25–39. doi: 10.1177/1534734603002001006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hussain K., Shahazad A., Zia-ul-Hussnain S. An ethnobotanical survey of important wild medicinal plants of Hattar district Haripur, Pakistan. Ethnobotanical Leaflets. 2008;1(5) Ethnobotanical Leaflets. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown C. H. Folk botanical life‐forms: their universality and growth. American Anthropologist. 1977;79(2):317–342. doi: 10.1525/aa.1977.79.2.02a00080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nasir E., Ali S. I., Stewart R. R. Flora of West Pakistan: An Annotated Catalogue of the Vascular Plants of West Pakistan and Kashmir. Fakhri; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmad S. Flora of Punjab, Lahore: Monograph. Biological Society of Pakistan; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips O., Gentry A. H. The useful plants of Tambopata, Peru: I. Statistical hypotheses tests with a new quantitative technique. Economic Botany. 1993;47(1):15–32. doi: 10.1007/BF02862203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chah K. F., Eze C. A., Emuelosi C. E., Esimone C. O. Antibacterial and wound healing properties of methanolic extracts of some Nigerian medicinal plants. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2006;104(1-2):164–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.08.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fullas F. Ethiopian medicinal plants in veterinary healthcare. A mini-review. Ethiopian E-Journal for Research and Innovation Foresight. 2010;2(1):48–58. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rasik A. M., Raghubir R., Gupta A., et al. Healing potential of Calotropis procera on dermal wounds in Guinea pigs. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1999;68(1-3):261–266. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(99)00118-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reddy J. S., Rao P. R., Reddy M. S. Wound healing effects of Heliotropium indicum, Plumbago zeylanicum and Acalypha indica in rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2002;79(2):249–251. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00388-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar M. S., Sripriya R., Raghavan H. V., Sehgal P. K. Wound healing potential of Cassia fistula on infected albino rat model. Journal of Surgical Research. 2006;131(2):283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Öztürk N., Korkmaz S., Öztürk Y. Wound-healing activity of St. John's Wort (Hypericum perforatum L.) on chicken embryonic fibroblasts. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2007;111(1):33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rawat S., Singh R., Thakur P., Kaur S., Semwal A. Wound healing agents from medicinal plants: a review. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine. 2012;2(3):S1910–S1917. doi: 10.1016/s2221-1691(12)60520-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jarić S., Kostić O., Mataruga Z., et al. Traditional wound-healing plants used in the Balkan region (Southeast Europe) Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hussain K., Shahazad A., Zia-ul-Hussnain S. An ethnobotanical survey of important wild medicinal plants of Hattar district Haripur, Pakistan. Ethnobotanical Leaflets. 2008;1(5) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jain S. K. Dictionary oF Indian Folk Medicine and Ethnobotany. Deep Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmed H. M. Traditional uses of Kurdish medicinal plant Pistacia atlantica subsp. kurdica Zohary in Ranya, Southern Kurdistan. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 2017;64(6):1473–1484. doi: 10.1007/s10722-017-0522-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bukhari I. A., Khan R. A., Gilani A. H., Ahmed S., Saeed S. A. Analgesic, anti-inflammatory and anti-platelet activities of the methanolic extract of Acacia modesta leaves. Inflammopharmacology. 2010;18(4):187–196. doi: 10.1007/s10787-010-0038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaya I., Yigit N., Benli M. Antimicrobial activity of various extracts of Ocimum basilicum L. and observation of the inhibition effect on bacterial cells by use of scanning electron microscopy. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines. 2008;5(4):363–369. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v5i4.31291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Selvakkumar C., Gayathri B., Vinaykumar K. S., Lakshmi B. S., Balakrishnan A. Potential anti-inflammatory properties of crude alcoholic Extract of Ocimum basilicum L. in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Journal of Health Science. 2007;53(4):500–505. doi: 10.1248/jhs.53.500. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qadir M. I., Abbas K., Hamayun R., Ali M. Analgesic, anti-inflammatory and anti-pyretic activities of aqueous ethanolic extract of Tamarix aphylla L. (Saltcedar) in mice. Pakistan Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2014;27(6):1985–1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shabani Z., Sayadi A. The antimicrobial in vitro effects of different concentrations of some plant extracts including tamarisk, march, acetone and mango kernel. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science. 2014;4(5):75–79. doi: 10.7324/JAPS.2014.40514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vinothapooshan G., Sundar K. Wound healing effect of various extracts of Adhatoda vasica. International Journal of Pharma and Bio Sciences. 2010;1(4):530–536. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.