Summary

Social norms can greatly influence people’s health-related choices and behaviours. In the last few years, scholars and practitioners working in low- and mid-income countries (LMIC) have increasingly been trying to harness the influence of social norms to improve people’s health globally. However, the literature informing social norm interventions in LMIC lacks a framework to understand how norms interact with other factors that sustain harmful practices and behaviours. This gap has led to short-sighted interventions that target social norms exclusively without a wider awareness of how other institutional, material, individual and social factors affect the harmful practice. Emphasizing norms to the exclusion of other factors might ultimately discredit norms-based strategies, not because they are flawed but because they alone are not sufficient to shift behaviour. In this paper, we share a framework (already adopted by some practitioners) that locates norm-based strategies within the wider array of factors that must be considered when designing prevention programmes in LMIC.

Keywords: social norms, harmful practices, intervention, community health promotion, low-income countries

Social norms theory is opening new programmatic avenues for health promotion in low- and mid-income countries (LMIC) (Chung and Rimal, 2016; Miller and Prentice, 2016; Tankard and Paluck, 2016). As practitioners have begun to deploy social norm strategies to improve health, however, there has been a tendency to focus on norms to the exclusion of other factors that inform people’s actions. Using social norms theory without appreciating the place that norms occupy among other drivers of behaviour, might position interventions for failure, ultimately discrediting promising strategies simply because, in isolation, they are inadequate to improve health. The aim of this paper is to provide a framework that practitioners can use to embed a social norm perspective within integrated health interventions that address the multiple factors that sustain harmful behaviours.

SOCIAL NORMS AND HEALTH INTERVENTIONS IN LMIC

Researchers have been aware of the influence of social norms—informal rules of behaviour that dictate what is acceptable within a given social context—for a long time (Young, 2007; Mackie et al., 2015; Chung and Rimal, 2016). However, in recent years, there has been a surge of interest among both scholars and practitioners in transforming norms as a tool to achieve change in people’s behaviour and improve people’s health and well-being (Mollen et al., 2010).

Although all disciplines agree that social norms influence health-related behaviours, they offer different theoretical perspectives on what social norms are, how they form and how they shape behaviour (see reviews by Brennan et al., 2013; Elsenbroich and Gilbert, 2014; Mackie et al., 2015; Young, 2015). Loosely speaking, there are three main schools of thought on social norms that respectively defined them as: (i) behavioural patterns, (ii) collective attitudes and (iii) individuals’ beliefs about others’ behaviours and attitudes (Morris et al., 2015; Young, 2015). Contemporary research in health science has empirically demonstrated the usefulness of the third, ‘norms as beliefs’, school of thought, which emerged mostly from social psychology (e.g. Cialdini et al., 1990), as a means to explain and also to influence people’s health-related choices (Borsari and Carey, 2003; Eisenberg et al., 2005; Rimal and Real, 2005; McAlaney and Jenkins, 2015; Ahmed et al., 2016). Contemporary scholars in this tradition argue that social norms are one’s beliefs about (i) what others do and (ii) of what others approve and disapprove of (Gibbs, 1965; Cialdini et al., 1991; Cialdini and Trost, 1998; Lapinski and Rimal, 2005; Bicchieri, 2006; for a full review see Mackie et al., 2015). Among the work of various thinkers in this tradition, Cialdini’s has been the most influential (Cialdini and Trost, 1998). In this paper, we adopt theory and terminology developed by him and his colleagues, who identified two distinct types of social norms: (i) beliefs about what others do (descriptive norms) and (ii) beliefs about what others approve and disapprove (injunctive norms) (Cialdini et al., 1990; Cialdini and Trost, 1998; Cialdini et al., 2006). People tend to comply with descriptive and injunctive norms for a variety of reasons (Bell and Cox, 2015), the most well studied being the anticipation of social rewards and punishments for compliance and non-compliance, respectively (Bicchieri, 2006; Elster, 2007). Even though empirical findings in the health sciences have offered ground-breaking contributions to our understanding of the influence of social norms on a wide range of health outcomes (e.g. Piliavin and Libby, 1986; Peterson et al., 2009; Gidycz et al., 2011; McAlaney and Jenkins, 2015; Berger and Caravita, 2016; Prestwich et al., 2016; Templeton et al., 2016), most of these empirical findings emerge from studies conducted in high-income countries; the most famous case being the use of social norms theory to reduce use of alcohol and recreational drugs in US college campuses (Borsari and Carey, 2003; Lewis and Neighbors, 2006; Prestwich et al., 2016). This narrow evidence base is particularly problematic given donors’ and practitioners’ recent interest in integrating social norms theory into health interventions in LMIC. Each LMIC obviously presents characteristics that are unique to its context; yet, commonalities exist in the political and social features of most LMIC. These commonalities include, for instance: traditional forms of power often compensating for weaker state control and enforcement of the law (Englebert, 2009); relatively weak infrastructures (including reduced access to information and communication technology) (Abiad et al., 2017); and persistent economic deprivation impacting on the effectiveness of the formal health systems (Mills, 2011).

The literature on the effectiveness of social norms interventions for increasing health and well-being in LMIC is sparse but growing. The most promising examples are emerging from the field of sexual and reproductive health and rights (Haylock et al., 2016; Read-Hamilton and Marsh, 2016). For instance, social norms theory has been used extensively to understand the persistence of female genital cutting (FGC), a non-medically justified modification of women’s genitalia that poses a global threat to the health of 140 million of women and girls globally (Wagner, 2015). Existing programme implementations that targeted social norms around FGC offered important insights into the potential of addressing social norms for social change, suggesting that community-based interventions can be effective in achieving behavioural change when they successfully integrate an approach that considers the social environment (Diop et al., 2008; Cislaghi et al., 2016; Miller and Prentice, 2016; Tankard and Paluck, 2016). Take, for instance, 3-year, community-led social change programme implemented by the Non-governmental Organisation (NGO) Tostan, which was widely studied as an effective model to change social norms sustaining FGC in Senegal (Johnson, 2003; Diop et al., 2004; Mbaye, 2007; Diop et al., 2008; Easton et al., 2009; CRDH, 2010; Gillespie and Melching, 2010; Mcchesney, 2015; Cislaghi, 2017, 2018). The multi-pronged programme implemented by Tostan offers some important lessons. It was found effective in changing people’s health-related practices because it integrated a social norms component within an intervention that also addressed people’s individual attitudes and knowledge, local institutional policies and political accountability, and community members’ economic conditions (Cislaghi et al., 2016). Similar integrated interventions seem particularly promising exactly because they address social norms in their interplay with other factors affecting people’s health and well-being. Yet, practitioners working to increase people’s health in LMIC lack a practical framework they can easily use to plan and deliver effective social norms programmes that also address other behavioural drivers. We offer a first attempt at such a framework in the next section.

A DYNAMIC FRAMEWORK TO EMBED SOCIAL NORMS

Human action almost never originates from a single cause. Relying exclusively on norms-based approaches for improving health outcomes oversimplifies the true complexity of human behaviour. We concur with Brennan and colleagues that ‘we doubt that many if any norms provide reasons that literally exclude from consideration any interestingly wide range of other reasons for action’ (Brennan et al., 2013, p. 251). Most of the social norms interventions used with students in high-income countries have focused on changing descriptive norms; that is: they aimed to correct students’ misperceptions about the number of other students who drink or use recreational drugs. In their approach, they lacked an integrated framework that would help address other factors contributing to the harmful behaviour of interest, this possibly being one of the reasons for their mixed effectiveness (Borsari and Carey, 2003; Lewis and Neighbors, 2006; Prestwich et al., 2016).

What then should accompany social norms in a framework of factors influencing health-related behaviours? A plethora of models of what influences behaviour exist and reviews can be found across many disciplines (see, for instance, Darnton, 2008). One of the most frequently cited is the ‘ecological framework’. Originally created by Bronfenbrenner (1992, 2009), the ecological framework helps understand the influence of the micro, meso and macro environments on human behaviour. The ecological framework has been adapted by many scholars (Tudge et al., 2009) to study social influence on various health-related issues. These issues include, to cite a few examples: pollution (Underwood and Peterson, 1988), nutrition (Smaling, 1993), adolescent self-esteem (DuBois et al., 1996), elder abuse (Schiamberg and Gans, 2000) and school bullying (Swearer and Espelage, 2004). One of the most well-known adaptations of the ecological framework among practitioners working on social norms in LMIC is Heise’s (Heise, 1998). Heise’s adaption is the starting point for many practitioners working to change social norms in LMIC, particularly those working on harmful gender-related social norms and related practices (e.g. FGC, child marriage or intimate partner violence). This framework (as Bronfenbrenner’s before) integrates social norms as a factor contributing to making up cultural influences in the macrosystem. Heise’s ecological framework, however, was never meant as a tool to plan interventions; its initial aim was to offer a model for understanding the interaction of factors that increase or decrease the likelihood of intimate partner violence at an individual or population level. For it to become a practical tool that NGO practitioners can use when planning social norm interventions, Heise’s framework needs to evolve in two ways. First, it needs to offer practitioners an easy way to adapt it to the contexts in which they implement their programmes. The existing version provides a useful way to organize factors that have emerged as predictive of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) across multiple settings. It intends to conceptualize the phenomenon of IPV rather than equip practitioners with a tool to diagnose the specific factors driving IPV in a specific setting. Second, the framework needs to spell out key factors that are currently hidden within the framework (as, for instance, power), as well as the interactions between the various factors that fall on the framework.

THE DYNAMIC FRAMEWORK FOR SOCIAL CHANGE

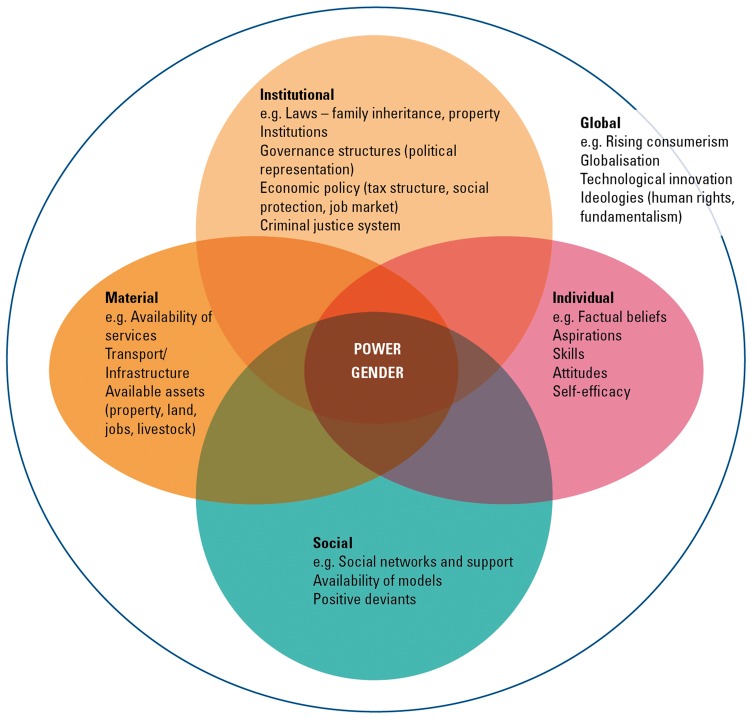

We suggest here a possible adaptation of the ecological framework, where four domains of influence (institutional, material, social and individual) overlap (see Figure 1).

Fig. 1:

Dynamic framework for social change.

The individual domain includes all factors related to the person: factual beliefs, aspirations, skills, attitudes and self-efficacy, to cite a few. The social domain includes factors such as the availability of different types of social support, the configuration of social networks both proximal and distal and exposure to positive deviants in a group, for instance. Factors in the material domain include physical objects and resources—money, land or services, for example. Finally, the institutional domain includes the formal system of rules and regulations (laws, policies or religious rules).

Importantly, these domains overlap generating cross-cutting factors that also contribute to influencing people’s actions. For example, ‘access to services’ would fall at the intersection between individual (I), social (S) and material (M) domains. As Bersamin et al. (2017) recently found in their study of young female students’ access to the health services, people access health services when (i) those services physically exist (M); (ii) they know what those services offer and when they should visit them (I); and (iii) they believe that they won’t incur social disapproval if they visit the health service, i.e. that there are no social norms against accessing the service (S). What is unique about this framework, thus, is that it both highlights the importance of addressing change at those intersections—where social norms operate and programmatic action can be the most effective—and offers a tool to design intervention strategies that address interactions between factors.

USING THE FRAMEWORK

The use of the framework to plan a health intervention has two steps. In the first, the factors hypothesized to generate or sustain the behaviour of interest are identified, using available research, practice-based evidence and formative research. Next, collaborating partners distribute these factors across the various domains and intersections of the framework, perhaps during a workshop to develop a theory of change to inform intervention development.

Table 1 can help organize this work. The table includes (i) an indication of the domain of analysis (first column),(ii) the factors falling in that domain that affect the health outcome of interest (second column), (iii) the dynamics through which those factors influence the health outcome (third column) and (iv) the level of influence that the particular factor has over a behaviour (fourth column).

Table 1:

A practical tool to diagnose factors influencing a behaviour of interest on the dynamic framework

| Domain | Factors | Contribution to health outcome | Level of influence (high, mid, low) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | Knowledge | ||

| Values | |||

| Skills | |||

| Self-efficacy | |||

| Aspirations | |||

| Social/material | Inheritance traditions | ||

| (intersection) | Social Mobility | ||

| Material | Services | ||

| Laws | |||

| Individual/social/material | Access to services | ||

| (Intersection) | |||

| Individual/social/material/structural | Power relations | ||

| (intersection) | Gender roles | ||

| … | … | … | … |

Through a collective process of reflection, this process generates hypotheses and prompts collective discussion, particularly around what falls in the intersections between domains. There is no single way in which this framework could or should be populated. Contextual socio-cultural circumstances and the characteristics of the phenomenon on which practitioners want to intervene will change what factors fall into each domain.

USING THE FRAMEWORK: A PRACTICAL EXAMPLE FROM AN INTERVENTION DESIGN WORKSHOP

Let us give an example. Recently, this framework was used to facilitate the design of an intervention on social norms and violence against children (VAC). During the design workshop, participants split into three groups. Participants identified, by group, the factors contributing to VAC in the region where the intervention was to be run. They did so by discussing the existing evidence (as well as their own understandings as cultural insiders) of how the factors in each section of the diagram contributed to sustaining VAC in that particular area. The groups then regathered and compared/contrasted their findings. The final list that emerged as a result of the plenary discussion included several factors sustaining or potentially preventing VAC in the intervention area. As participants identified these factors, they specifically looked at the role that social norms played in sustaining them.

Workshop participants then proceeded to the second step. The second step is action-oriented: programme designers identify the key factors that their intervention can and should address and seek collaborating partners to address factors that fall outside the reach or realm of expertise. Participants in the workshop first grouped similar factors into themes and then discussed the dynamic relation between these themes. Several questions emerged in this discussion; for instance: which themes are more important to address in the intervention? what would be the cascading effect of changing social norms on the different themes? which social protective social norms can we leverage? which themes required the collaboration of other stakeholders? From this conversation, participants drew a diagram showing the dynamic relation between themes and their influence on VAC. This diagram eventually informed the following conversations on what entry points existed for the intervention and on what collaborations were required to achieve effective sustainable change.

The purpose of the dynamic framework is not to determine precisely in which domain a particular factor should fall. Rather, it is to generate discussion and reflection among practitioners about the factors that influence a particular health outcome in a given context and the role that social norms may play in strengthening or weakening those factors. Such discussions help plan an intervention and assess the need to coordinate with other actors to ensure effective and sustainable change.

SOCIAL NORMS IN THE DYNAMIC FRAMEWORK

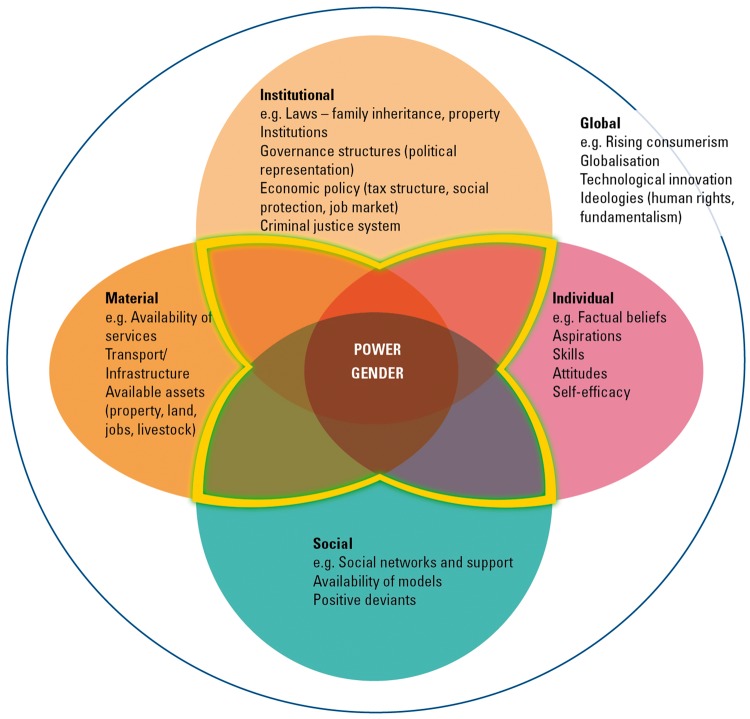

A socio-psychological approach to social norms (specific to one’s beliefs about the behaviours and attitudes of others) would place them at the intersection between the individual and the social domain. While we think that intersection can be an appropriate place for social norms, we also think it’s important to stress the fact that social norms play a role in all intersections. Embedded within local institutions and practices, social norms influence distribution of material resources, as well individual aspirations, and institutional laws and policies (see Figure 2).

Fig. 2:

The influence of social norms visualized on the dynamic framework.

Integrating a social norms perspective within health interventions, thus, contributes valuable potential because it can generate results across many intersections; it can widen existing positive cracks in hegemonic collective beliefs and generate space where change can happen. As such, the dynamic framework is not only a practical tool for diagnosing and planning effective integrated interventions, it becomes an ideational tool in which to plan ways that social norms change can be directed at both individuals and institutions.

CONCLUSION

Today’s considerable interest in using social norms theory to achieve positive health outcomes must be accompanied by an understanding of how a norms perspective can be integrated into a wider approach to social change. In this paper, we presented a framework that can help practitioners diagnose and plan effective interventions by embedding a social norms perspective into their programming. We refer to this framework as the dynamic framework for social change (but note that some practitioners who are using it refer it as ‘the flower’) because it encourages practitioners to look at the dynamic interactions between different domains of influence and how those interactions contribute to harmful practices. The dynamic framework helps recognize, in particular, the combined influence of various factors in each domain, suggesting that interventions should aim to achieve cooperation with other actors working at different points of influence. It also encourages practitioners to recognize the multi-faceted potential of working with norms at both the individual, collective, and institutional levels. This framework has been used by several NGO practitioners who found it both intuitive and useful for programme design. We offer it to the larger community of practitioners working to improve health in LMIC, hoping that others will join those who have already adopted it in their work.

FUNDING

The study was supported by UKaid from the Department for International Development through STRIVE, a research consortium based at the LSHTM. However, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the department's official policies.

REFERENCES

- Abiad A., Debuque-Gonzales M., Sy A. L. (2017) The Role and Impact of Infrastructure in Middle-Income Countries: Anything Special? Asian Development Bank, Manila. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed A. K., Weatherburn P., Reid D., Hickson F., Torres-Rueda S., Steinberg P.. et al. (2016) Social norms related to combining drugs and sex (“chemsex”) among gay men in South London. International Journal of Drug Policy, 38, 29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell D. C., Cox M. L. (2015) Social norms: do we love norms too much? Journal of Family Theory Review, 7, 28–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger C., Caravita S. C. (2016) Why do early adolescents bully? Exploring the influence of prestige norms on social and psychological motives to bully. Journal of Adolescence, 46, 45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bersamin M., Fisher D. A., Marcell A. V., Finan L. J. (2017) Reproductive health services: barriers to use among college students. Journal of Community Health, 42, 155–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bicchieri C. (2006) The Grammar of Society. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B., Carey K. B. (2003) Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: a meta- analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64, 331–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan G., Eriksson L., Goodin R. E., Southwood N. (2013) Explaining Norms. Oxford University Press, Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. (1992) Ecological Systems Theory. In Vasta R. (ed.), Six Theories of Child Development: Revised Formulations and Current Issues. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London, England, pp. 187–249. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. (2009) The Ecology of Human Development. Harvard university press. [Google Scholar]

- Chung A., Rimal R. N. (2016) Social norms: a review. Review of Communication Research, 2016, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini R. B., Demaine L. J., Sagarin B. J., Barret D. W., Rhoads K., Winter P. L. (2006) Managing social norms for persuasive impact. Social Influence, 1, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini R. B., Kallgren C. A., Reno R. R. (1991) A focus theory of normative conduct: a theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 24, 1–243. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini R. B., Reno R. R., Kallgren C. A. (1990) A focus theory of normative conduct: recyling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini R. B., Trost M. R. (1998) Social influence: social norms, conformity and compliance In Gilbert D. T., Fiske S. T., Lindzey G. (eds), The Handbook of Social Psychology. McGraw-Hill, New York, Vol. II, pp. 151–192. [Google Scholar]

- Cislaghi B. (2017) Human Rights and Community-Led Development. EUP, Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Cislaghi B. (2018) The story of the ‘now-women’: changing gender norms in rural West Africa. Development in Practice, 28, 257–268. [Google Scholar]

- Cislaghi B., Gillespie D., Mackie G. (2016) Values Deliberation and Collective Action: Community Empowerment in Rural Senegal. Palgrave MacMillan, New York. [Google Scholar]

- CRDH. (2010) Évaluation De L’Impact Du Programme De Renforcement Des Capacités Des Communautés Mis En Œuvre Par Tostan En Milieu Rural Sénégalais Dans Les Régions De Tambacounda Et De Kolda, En 2009. Centre de Recherche pour le Développement Humain (CRDH; ), Dakar. [Google Scholar]

- Darnton A. (2008) Reference Report: an overview of behaviour change models and their uses https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/498065/Behaviour_change_reference_report_tcm6-9697.pdf (last accessed 7 March 2018).

- Diop N. J., Faye M. M., Moreau A., Cabral J., Benga H., Cissé F.. et al. (2004) The TOSTAN Program. Evaluation of a Community Based Education Program in Senegal. Population Council, GTZ and Tostan, Dakar. [Google Scholar]

- Diop N. J., Moreau A., Benga H. (2008) Evaluation of the Long-Term Impact of the TOSTAN Programme on the Abandonment of FGM/C and Early Marriage - Results from a Qualitative Study in Senegal. Population Council, Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- DuBois D. L., Felner R. D., Brand S., Phillips R. S. (1996) Early adolescent self-esteem: a developmental–ecological framework and assessment strategy. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 6, 543–579. [Google Scholar]

- Easton P., Monkman K., Miles R. (2009) Breaking out of the egg In Mezirow J., Taylor E. W. (eds), Transformative Learning in Practice: Insights from Community, Workplace, and Higher Education. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg M. E., Neumark-Sztainer D., Story M., Perry C. (2005) The role of social norms and friends' influences on unhealthy weight-control behaviors among adolescent girls. Social Science & Medicine, 60, 1165–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsenbroich C., Gilbert N. (2014) Modelling Norms. Springer, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Elster J. (2007). Explaining Social Behaviour, More Nuts and Bolts for the Social Sciences. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Englebert P. (2009) Africa: Unity, Sovereignty and Sorrow. Rienner, London. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs J. P. (1965) Norms: the problem of definition and classification. American Journal of Sociology, 70, 586–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz C. A., Orchowski L. M., Berkowitz A. (2011) Preventing sexual aggression among college men: an evaluation of a social norms and bystander intervention program. Violence against Women, 17, 720–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie D., Melching M. (2010) The transformative power of democracy and human rights in nonformal education: the case of Tostan. Adult Education Quarterly, 60, 477–498. [Google Scholar]

- Haylock L., Cornelius R., Malunga A., Mbandazayo K. (2016) Shifting negative social norms rooted in unequal gender and power relationships to prevent violence against women and girls. Gender & Development, 24, 231–244. [Google Scholar]

- Heise L. L. (1998) Violence against women: an integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women, 4, 262–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson N. K. (2003) The Role of NGO in Senegal: Reconciliating Human Rights Policies with Health and Developmental Strategies. Paper presented at the American Political Science Association, Philadelphia: on August 27, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lapinski M. K., Rimal R. N. (2005) An explication of social norms. Communication Theory, 15, 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M. A., Neighbors C. (2006) Social norms approaches using descriptive drinking norms education: a review of the research on personalized normative feedback. Journal of American College Health, 54, 213–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie G., Moneti F., Shakya H., Denny E. (2015) What Are Social Norms? How Are They Measured? New York, UNICEF and UCSD; https://www.unicef.org/protection/files/4_09_30_Whole_What_are_Social_Norms.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Mbaye A. (2007) Outcomes and Impact of Adult Literacy Programs in Senegal: Two Case Studies. University of Maryland, College Park. [Google Scholar]

- McAlaney J., Jenkins W. (2015) Perceived social norms of health behaviours and college engagement in British students. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 41, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Mcchesney K. (2015) Successful approaches to ending female genital cutting. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Miller D. T., Prentice D. A. (2016) Changing norms to change behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 67, 339–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills A. (2011) Health systems in low- and middle-income countries. In Glied S., Smith P. C. (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Health Economics, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 30–58. [Google Scholar]

- Mollen S., Rimal R. N., Lapinski M. K. (2010) What is normative in health communication research on norms? A review and recommendations for future scholarship. Health Communication, 25, 544–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris M. W., Hong Y.-y., Chiu C.-y., Liu Z. (2015) Normology: integrating insights about social norms to understand cultural dynamics. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 129, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson J. L., Rothenberg R., Kraft J. M., Beeker C., Trotter R. (2009) Perceived condom norms and HIV risks among social and sexual networks of young African American men who have sex with men. Health Education Research, 24, 119–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piliavin J. A., Libby D. (1986) Personal norms, perceived social norms, and blood donation. Humboldt Journal of Social Relations, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Prestwich A., Kellar I., Conner M., Lawton R., Gardner P., Turgut L. (2016) Does changing social influence engender changes in alcohol intake? A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84, 845–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read-Hamilton S., Marsh M. (2016) The communities care programme: changing social norms to end violence against women and girls in conflict-affected communities. Gender & Development 24, 261–276. [Google Scholar]

- Rimal R. N., Real K. (2005) How behaviors are influenced by perceived norms: a test of the theory of normative social behavior. Communication Research, 32, 389–414. [Google Scholar]

- Schiamberg L. B., Gans D. (2000) Elder abuse by adult children: an applied ecological framework for understanding contextual risk factors and the intergenerational character of quality of life. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 50, 329–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smaling E. M. A. (1993) An agro-ecological framework for integrated nutrient management, with special reference to Kenya. Ph.D., Agricultural University, Wagening, The Netherlands.

- Swearer S. M., Espelage D. L. (2004) Introduction: a social-ecological framework of bullying among youth. In Espelage D. L., Swearer S. M. (eds), Bullying in American Schools: A Social-Ecological Perspective on Prevention and Intervention. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, Mahwah, NJ, US, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Tankard M. E., Paluck E. L. (2016) Norm perception as vehicle for social change. Social Issues and Policy Review, 10, 181–211. [Google Scholar]

- Templeton E. M., Stanton M. V., Zaki J. (2016) Social norms shift preferences for healthy and unhealthy foods. PLoS One, 11, e0166286.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tudge J. R., Mokrova I., Hatfield B. E., Karnik R. B. (2009) Uses and misuses of Bronfenbrenner's bioecological theory of human development. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 1, 198–210. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood A., Peterson C. (1988) Towards an ecological framework for investigating pollution. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 46, 227–234. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner N. (2015) Female genital cutting and long-term health consequences—nationally representative estimates across 13 countries. The Journal of Development Studies, 51, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Young H. P. (2007) Social Norms. Oxford Discussion Papers Series, 307 University of Oxford, Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Young H. P. (2015) The evolution of social norms. Annual Review of Economics, 7, 359–387. [Google Scholar]