Summary

An efficient Agrobacterium‐mediated site‐specific integration (SSI) technology using the flipase/flipase recognition target (FLP/ FRT ) system in elite maize inbred lines is described. The system allows precise integration of a single copy of a donor DNA flanked by heterologous FRT sites into a predefined recombinant target line (RTL) containing the corresponding heterologous FRT sites. A promoter‐trap system consisting of a pre‐integrated promoter followed by an FRT site enables efficient selection of events. The efficiency of this system is dependent on several factors including Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain, expression of morphogenic genes Babyboom (Bbm) and Wuschel2 (Wus2) and choice of heterologous FRT pairs. Of the Agrobacterium strains tested, strain AGL1 resulted in higher transformation frequency than strain LBA4404 THY‐ (0.27% vs. 0.05%; per cent of infected embryos producing events). The addition of morphogenic genes increased transformation frequency (2.65% in AGL1; 0.65% in LBA4404 THY‐). Following further optimization, including the choice of FRT pairs, a method was developed that achieved 19%–22.5% transformation frequency. Importantly, >50% of T0 transformants contain the desired full‐length site‐specific insertion. The frequencies reported here establish a new benchmark for generating targeted quality events compatible with commercial product development.

Keywords: Agrobacterium, co‐integrate vector, FLP/ FRT , maize transformation, site‐specific integration, RMCE

Introduction

Advancements in plant transformation technology have made it possible to insert DNA sequences into plant genomes with relative ease. Methods have been developed for transformation of a large number of plant species, most often using Agrobacterium‐mediated or biolistic methods (De Buck et al., 2009; Jackson et al., 2013; Kohli et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2014; Zhi et al., 2015). However, transgenic events obtained from a single DNA construct, referred to as sister events, often exhibit different phenotypes (Hobbs et al., 1990; Jones et al., 1987; Peach and Velten, 1991). This variation led to a transgenic trait development paradigm wherein large numbers of sister events are generated and subjected to phenotyping, in order to identify an event with the desired phenotype (Strauss and Sax, 2016).

Most transformation methods generate sister events with significant differences at the DNA level, including copy number, truncation and rearrangement (Afolabi et al., 2004; Maessen, 1997; Puchta et al., 1994). This accounts for some event‐to‐event phenotypic variation. In order to minimize event‐to‐event variation, typically ~70% of the T0 events produced from the simple constructs (1–2 transgenes) are discarded using the molecular criteria for quality events (Zhi et al., 2015) and even higher proportions of the events are discarded when complex constructs are used (Anand et al., 2018). Therefore, only quality events (QE; single copy vector backbone‐free events) are preferred for phenotyping.

Additionally, deregulation of transgenic events that disrupt an endogenous gene is difficult (EFSA GMO Panel, 2011). Therefore, it is a common practice to discard events with transgenes in or near endogenous genes. Since 60%–75% of otherwise quality events fail to meet the above criteria, cumulatively >90% of the transgenic T0 events are discarded (Anand and Jones, 2018). One possible approach to reduce this attrition is to accurately insert transgenes into well characterized insertion sites through site‐directed integration (Akbudak et al., 2010; Cardi and Neal Stewart, 2016; Rinaldo and Ayliffe, 2015).

Most commercial transgenic maize products contain multiple transgenes. These multiple traits are combined through trait introgression and this process is increasingly difficult and costly with more traits (Peng et al., 2014; Sun and Mumm, 2015). A transformation method that uses site‐directed integration to create transgenic events in a single genetic region, a so‐called complex trait locus (CTL), presents a possible solution (Chilcoat et al., 2017). In a CTL, multiple transgenic events, each inserted in a short genomic region (1–5 centimorgans), can be linked through crossing. Once linked, these multiple traits segregate together, and can be treated as a single locus when conducting trait introgression.

The preferred methods for site‐directed insertion have typically relied on site‐specific integration (SSI) or homologous recombination (HR) (Lyznik et al., 2003; Ow, 2007; Terada et al., 2002; Tzfira and White, 2005). HR has only been achieved at very low frequencies (Srivastava and Thomson, 2016). SSI may have the potential for higher efficiencies since it relies on recombinases to insert donor DNA. The most preferred SSI strategy employs a target genomic locus that contains two heterologous recombination target sites (RT) flanking a selectable marker gene and donor DNA (Albert et al., 1995; Schlake and Bode, 1994; Turan et al., 2010, 2013). In the presence of a recombinase, the donor DNA is exchanged with the target, a process referred to as recombinase‐mediated cassette exchange (RMCE). This approach has been applied to transgene insertion in plants (Ebinuma et al., 2015; Li et al., 2009; Louwerse et al., 2007; Nandy and Srivastava, 2011, 2012; Nanto and Ebinuma, 2008; Nanto et al., 2005, 2009; Srivastava and Thomson, 2016).

Site‐specific integration in plants has generally been achieved using biolistic delivery of both the donor DNA and DNA encoding the recombinase, usually in the form of circular plasmid DNA (Albert et al., 1995; Chawla et al., 2006; Srivastava and Ow, 2002). However, biolistic delivery of DNA often results in complex DNA integration (multiple copies of the transgenes, truncated DNA and large deletion of genomic DNA). Most T0 events do not contain the desired RMCE. In short, even though SSI has been reported in a number of studies, low SSI frequencies (Li et al., 2009; Nanto et al., 2005; Ow, 2002), combined with the complex nature of DNA integrations, have prevented this technology from being widely used.

Here, we describe an efficient method of SSI in elite maize inbreds. This method uses Agrobacterium‐delivery of the flipase/flipase recognition target (FLP/FRT) recombinase system and the maize Babyboom (Bbm) and maize Wuschel2 (Wus2) genes (Lowe et al., 2016) to improve plant regeneration. The effect of Agrobacterium strain, vector design, use of Bbm/Wus2 genes and choice of heterologous FRT pairs on transformation frequency and recovery of T0 RMCE events in two elite maize inbreds is described. The method described here is a step‐function improvement over previously described maize transformation methods for generating quality events that do not disrupt endogenous genes.

Results

Development and characterization of recombinant target lines

Recombinant target lines (RTL) were created with heterologous FRT pairs consisting of a ZmUbi promoter followed by a FRT1 site; neomycin phosphotransferase (NPTII) selectable marker; cyan fluorescent protein (AmCyan1) marker; and a second, heterologous, FRT site (FRT6, 12 or 87; Figures 1a and 1d). A representative construct with FRT1/87 is described in Table S1. The ZmUbi promoter serves as a promoter trap when the RTL is subsequently used for RMCE. This enables activation of a marker gene in the donor DNA only when RMCE has occurred. This design is similar to one described for soybean SSI (Li et al., 2009, 2010). The RTLs were molecularly characterized using Southern‐by‐Sequencing™ technology, hereafter referred to as SbS analysis (Zastrow‐Hayes et al., 2015). SbS utilizes capture‐based target enrichment of samples prior to next‐generation sequencing (NGS) and is used to determine the insertion sequence and intactness of the inserted DNA at the target site. SbS allows the selection of single copy backbone‐free events with known genetic insertion sites. In addition, this technique can also confirm the absence of unintended DNA sequence insertion, either at the target site or other genomic locations.

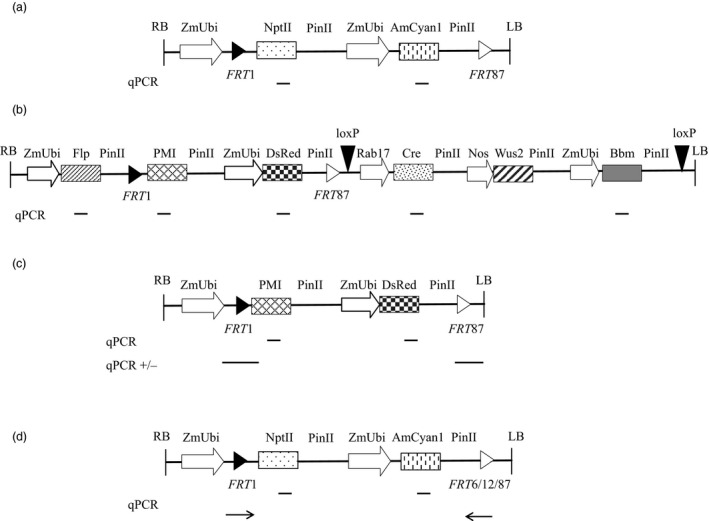

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of the DNA constructs and the intended recombinase‐mediated cassette exchange event (RMCE). (a) Target T‐DNA containing the constitutive promoter ZmUbi driving the neomycin transferase (nptII ) gene as plant selectable marker, and the same ZmUbi promoter driving the cyan fluorescent (AmCyan1) gene as fluorescent marker for selecting transformed cells. A FRT 1 site (black triangle) is placed between the ZmUbi promoter and the nptII gene, and a FRT 87 site (white triangle) is placed at the 3′ end. (b) Donor DNA3 T‐DNA containing the same heterologous FRT sites flanking a promoterless phosphomannose isomerase (pmi) gene, which confers mannose resistance when expressed and a fluorescent reporter gene, DsRed, driven by ZmUbi promoter allowing the selection of recombined transgenic events is shown as an example of a donor construct. This donor construct also contains the ZmUbi promoter driving the flp gene delivering the FLP recombinase needed for generating intended RMCE events on the 5′ of the donor DNA, an inducible cre gene by Rab17 promoter, a maize Wuschel (Wus2) gene driven by a nos promoter and a maize Babyboom (Bbm) gene driven by ZmUbi promoter on the 3′ end of the donor DNA flanked by loxP sites (inverted black triangles). Transient expression of the flp, Wus2 and Bbm gene is sufficient for recovering RMCE events. (c) RMCE event is essentially the target DNA, wherein the nptII and AmCyan1 gene between the FRT 1 and FRT 87 site is replaced with the pmi and DsRed gene on the donor DNA. The pmi gene is activated upon being inserted downstream of the ZmUbi promoter following cassette exchange between the FRT sites. All the components outside the FRT sites on the donor DNA are not integrated following recombination in an intended RMCE event. (d) The qPCR assay devised to quantify cross‐reactivity between different heterologous FRT sites. Relative positions of the gene‐specific qPCR assays, genomic DNA border‐specific PCR assays are marked with straight lines which were used for quantifying corresponding expression units and FRT junction calls, while the line with arrow indicate the relative position of the primer‐probe used for detecting excision.

SSI optimization in target line GT6

Once RTLs were created, we conducted a series of experiments with immature embryos derived from hemizygous plants to optimize SSI efficiency. The donor T‐ DNA design included a promoter‐less selectable marker gene, pmi, and red fluorescent protein marker gene DsRed flanked by corresponding heterologous FRT sites that matched the target FRT sites and a flp expression cassette (Donor DNA1, Table S1). In some cases, the donor T‐DNA also carried morphogenic genes, and an inducible Cre cassette as described in Figure 1b. Upon delivery of the donor DNA and expression of the FLP recombinase, RMCE can occur, wherein the RTL containing nptII + AmCyan1 is replaced with pmi + DsRed (Figure 1c) carried on the donor DNA. As a result, the promoter‐less pmi gene is inserted downstream of the ZmUbi promoter allowing retransformed events to be selected on mannose containing medium.

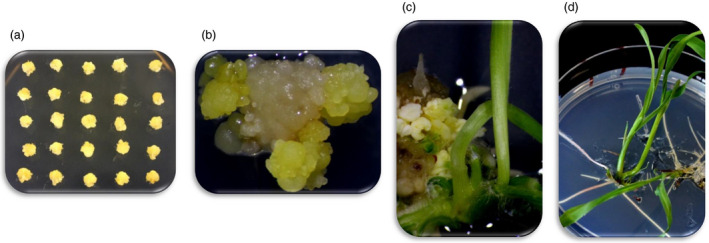

We evaluated two different Agrobacterium strains (LBA4404 and AGL1) and five different T‐DNA vector designs (Table S1) for optimizing SSI frequency. Initial studies for selecting Agrobacterium strain, optimizing construct design and optimizing culture conditions involved a single RTL in the elite genotype HC69 with FRT1/87 FRT sites (GT6). The process included Agrobacterium infection of immature embryos (Figure 2a), two or three rounds of mannose selection (Figure 2b), regeneration of transgenic events (Figure 2c) and rooting of the individual transgenic event on selection media (Figure 2d).

Figure 2.

The different stages in transformation for selecting intended RMCE events using the target line GT6. (a) Retransformation of immature embryos from the RTL containing the nptII selectable marker. (b) Selection of the putative RMCE events in media supplemented with mannose; this selection requires 2–3 rounds of transfer before a site‐specific integration event is identified. (c) Regeneration of the putative SSI event after three rounds of selection in mannose supplemented media and, (d) Rooting of the putative RMCE events in media supplemented with mannose. The overall transformation process to generate putative RMCE events takes over 3 months.

Once T0 events were regenerated, we identified events with the intended RMCE outcome through a combination of quantitative PCR (qPCR) and PCR analyses. This included a multiplexed PCR assay for detection of the vector backbone. PCR assays were also designed to sequences flanking the FRT sites and qPCR assays targeted to the excised marker gene (nptII), genes from the donor DNA (e.g. pmi and DsRed) and the FLP recombinase gene (flp) (Figure 1 and Table S2). RMCE events were defined as having the (i) presence of single intact copies of the donor genes (pmi and DsRed); (ii) absence of the excised marker gene (nptII); (iii) presence of FRT1 and FRT87 junctions; and (iv) absence of unintended DNA sequence insertions including the vector backbone and the flp gene. Some events have cassette exchange but also may contain additional DNA insertions, for example random insertions of the T‐DNA or backbone sequences. Other events may have accurate recombination of the 5′ FRT site but illegitimate recombination at the 3′FRT site. These events are considered non‐RMCE events.

Agrobacterium strain and morphogenic genes

It was previously shown different Agrobacterium strains vary in their ability to transform maize (Cho et al., 2014; Li et al., 2015). Therefore, we evaluated two commonly used Agrobacterium strains, AGL1 (a succinamopoine‐type hypervirulent strain) and LBA4404 THY‐ (an auxotrophic octopine‐type strain) for SSI. AGL1 and LBA4404 THY‐ carrying the donor DNA 1 (Table S1), were used. The T0 transformation frequency is presented in Table 1 indicating that the strain AGL1 resulted in greater than fivefold higher transformation frequency than strain LBA4404 THY‐.

Table 1.

Effect of Agrobacterium strain and maize morphogenic genes Bbm and Wus2 on transformation frequency and RMCE event recovery in maize inbred HC69 (GT6) with FRT1/87 target site

| Maize inbred | Agrobacterium strain | Bbm/Wus2 | Embryos (number) | Events (number) | T0 frequency (percentage) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | SSI | Transformation | RMCE* | ||||

| HC69 | AGL1 | − | 3376 | 9 | 4 | 0.27 | 0.12 |

| AGL1 | + | 3436 | 91 | 38 | 2.65 | 1.12 | |

| LBA4404 THY‐ | − | 4015 | 2 | 0 | 0.05 | 0 | |

| LBA4404 THY‐ | + | 3953 | 24 | 5 | 0.61 | 0.13 | |

RMCE events are characterized by (i) presence of single intact copy of the donor genes (pmi and DsRed); (ii) absence of the excised marker gene (nptII); (iii) presence of FRT1 and FRT87 junctions; and (iv) absence of unintended DNA sequence insertions including those derived from vector backbone, Bbm, cre and flp gene.

The molecular event quality was determined as previously described. Molecular analysis of the T0 events and the frequency of SSI events recovered from the two strains from multiple experiments are presented in Table 1 and Table S2. Molecular analysis of the T0 events indicated the two T0 events regenerated from LBA4404 THY‐ were non‐RMCE events, while four out of nine T0 events from AGL1 were RMCE events. Based on the RMCE frequency. AGL1 produced more of the RMCE events than LBA4404 THY‐(0.12% vs. 0%). The four RMCE events identified had no accessory DNA insertions based on qPCR detection, suggesting that transient expression of flp resulted in SSI.

Next, we investigated the impact of maize morphogenic genes (Bbm and Wus2) on Agrobacterium‐mediated SSI. It is known that morphogenic genes can improve transformation frequency in maize (Lowe et al., 2016). We used a two T‐DNA cohabitating vector (CHV) design for testing, one with the donor DNA (donor DNA1, Table S1; spectinomycin antibiotic marker) and the second carrying the morphogenic genes (DNA2, Table S1; kanamycin antibiotic marker). These two T‐DNA plasmids reside in a single Agrobacterium strain. Stable integration of morphogenic genes can reduce regeneration (Lowe et al., 2016), therefore a stress inducible Rab17 promoter (Vilardell et al., 1991) driving expression of the cre recombinase was used to excise the Bbm, Wus2 and cre expression cassettes flanked by loxP sites. Addition of morphogenic genes improved transformation frequency in both Agrobacterium strains, LBA4404 THY‐ and AGL1. The recovery of T0 transformants with strain LBA4404 THY‐ increased from 0.05% (binary vector) to 0.61% in the presence of the maize morphogenic genes. Similarly, AGL1 carrying the maize morphogenic genes exhibited an ~10‐fold increase in transformation frequency, from 0.27% to 2.65% (Table 1).

For experiments that included morphogenic genes, molecular characterization of T0 events was performed as described earlier with the inclusion of qPCR assays for the detection of the Bbm and cre genes. RMCE events were identified using the same criteria as described earlier, with addition of Bbm and cre genes to the list of unintended DNA insertion. A summary of molecular characterization and identification of SSI events are provided in Table S3. Five RMCE events were recovered from LBA4404 THY‐ (Table 1), our first successful recovery of SSI events utilizing this strain in these studies. Similarly, strain AGL1 carrying the maize morphogenic genes increased in RMCE frequency 10‐fold (0.12%–1.12%) as shown in Table 1.

The data presented in Table S3 indicate that RMCE events resulted from the transient expression of flp (#1 and #4) or the combination of Bbm and flp genes as none of the genes could be detected by qPCR (#7, #14 to #18). Taken together, these data demonstrate improved recovery of T0 transformants and RMCE events in the presence of maize morphogenic genes during Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation. Due to the marked improvement in recovery of both T0 transformants and RMCE events with strain AGL1, all future SSI experiments were performed using this strain carrying the maize morphogenic genes.

The strain AGL1 containing the morphogenic genes was also tested in a second maize elite inbred line, PH2RT, containing the FRT1/87 RTL for Agrobacterium‐mediated SSI. Three RMCE events were identified infecting over 2050 embryos suggesting very low RMCE (0.15%) frequency compared to HC69 (1.12%). The above data establishes successful Agrobacterium‐mediated SSI in a different maize inbred.

Single T‐DNA donor design with morphogenic genes

The co‐transformation frequency of two T‐DNAs range anywhere >60% which can be variable in maize (Miller et al., 2002). Therefore, we speculated that lower co‐transformation frequency is likely to reduce the efficiency of Agrobacterium‐mediated SSI. To test this hypothesis, we developed single T‐DNA vectors containing the donor DNA, flp recombinase and excisable Bbm, Wus2 and cre expression cassettes flanked by loxP sites (See Table S1, donor DNA3). The impact of the two‐TDNA vector design (donor DNA1+ DNA2) was compared to the single T‐DNA design (donor DNA3) using target line GT6. Transformation, event regeneration and molecular characterization of the T0 transformants were performed as previously described. The T0 transformation and RMCE event frequencies are summarized in Table 2. The single T‐DNA vector (donor DNA3) produced higher T0 transformation (3.9% for single T‐DNA vs. 2.9% for two T‐DNA) and RMCE (1.15% for single T‐DNA vs. 0.61% for two T‐DNA) event frequencies. An ~ twofold improvement in the frequency of RMCE event recovery was observed using the single T‐DNA vector.

Table 2.

Comparison of the single T‐DNA and two T‐DNA vectors carrying morphogenic genes on Agrobacterium‐mediated SSI in target line GT6. The transformation and intended RMCE events were identified from side‐by‐side testing of the single T‐DNA (donor DNA3) and two‐T‐DNA constructs (donor DNA1+ DNA2)

| Vector design | Embryos (number) | T0 transformation | RMCE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events (number) | Frequency | Events (number) | Frequency | ||

| Donor DNA1+ DNA2 | 2269 | 66 | 2.9% | 14 | 0.61% |

| Donor DNA3 | 2252 | 88 | 3.9% | 26 | 1.15% |

Over 100 T0 RMCE events, were subjected to SbS analysis (Zastrow‐Hayes et al., 2015). Only events with fully intact donor DNA insertions (flanked by intact FRT1/87 sites) and no unintended DNA sequence were considered SbS‐pass events. Using these criteria, 85% (60 of 71 T0 RMCE events) of the single T‐DNA generated events passed SbS screening, while 69% (42 of 61 T0 RMCE events) of the events from two T‐DNA passed SbS. The two T‐DNA design had significantly higher SbS fail rate (31%; P = 0.032). Based on the improved RMCE and SbS pass frequencies the single T‐DNA approach for Agrobacterium‐mediated SSI is superior.

Testing of different FRT pairs

Choice of heterologous recombination sites was previously shown to improve RMCE frequency (Li et al., 2010; Louwerse et al., 2007). Compatible target sites in direct orientation with high cross‐reactivity is likely to favour excision in the presence of recombinase. If the reaction in the presence of recombinase favours excision, RMCE is likely to be lower. Therefore, heterologous FRT sites with low cross‐reactivity have the potential to further improve RMCE efficiency. To validate this hypothesis, three heterologous FRT site combinations, FRT1/6, FRT1/12 and FRT1/87, were evaluated. The FRT pairs described here differ in the spacer sequence (Table S4). Heterologous FRT pairs in direct orientation differ with respect to cross‐reactivity (self‐recombination) between themselves and can result in excision, inversion or recombination (Li et al., 2009, 2010). A transient screening method was developed to quantify the cross‐reactivity between the FRT pairs. This involved transient expression of FLP (3 or 6 days’ post‐treatment) delivered through either Agrobacterium or biolistic transformation (FLP plasmid DNA concentration—2.5 or 10 ng/shot), followed by qPCR determination of CT values to quantify the frequency of excision. FRT pairs that readily cross‐react or recombine are expected to have lower CT values, while FRT pairs with lower cross‐reactivity will have higher CT values.

We initially tested different DNA delivery methods to evaluate FLP‐mediated cross‐reactivity between heterologous FRT sites using GT6 embryos with FRT1/87 site. Agrobacterium‐ delivered FLP showed lower excision frequency (25%) compared to biolistically delivered FLP (50% at 2.5 ng and 100% at 10 ng) at 3‐day post‐treatment (DPT), while 100% excision was observed at day 6 with both delivery systems. This observation is consistent with the differences in the amount of DNA delivered by the two methods.

Since the biolistic delivery method allowed early detection and provided the flexibility to vary FLP concentrations to measure FRT cross‐reactivity, we used this method to measure excision frequency between multiple heterologous FRT pairs (1/6; 1/12 and 1/87) using embryos derived from independent target lines containing the FRT1/6, FRT1/12 or FRT1/87 sites. Two different FLP plasmid DNA concentrations (2.5 and 10 ng) and two different time points (3 and 6 days’ post‐treatment) were used for quantifying excision frequency. The data showed good correlation between the CT value, FLP DNA amount (2.5 and 10 ng), the number of days post‐treatment (3 DPT or 6 DPT) with the frequency of excision between the different FRT pairs tested (Table 3). Increasing amounts of FLP DNA and later time points resulted in lower CT values across the three FRT combinations (1/6; 1/12 and 1/87). The FRT1/87 pair readily excised in the presence of FLP (~100% excision irrespective of the amount of FLP DNA or time points), while lower excision rates were detected between the FRT1/6 pair (0% at 3 DPT and 8% at 6 DPT) and no excision was observed with the FRT1/12 pair in treatments with lower amounts of FLP DNA (2.5 ng, Table 3). At higher FLP concentrations, excision was detected between the FRT1/12 sites at 6 DPT (8%), while >30%–36% of the FRT1/6 pairs had recombined at the same time point (Table 3). Based on the above observations, we inferred that the FRT1/6 and FRT1/12 pairs with lower cross‐reactivity would be a better choice of FRT sites for improving the frequency of RMCE events.

Table 3.

Cross‐reactivity between different heterologous FRT sites in the presence of FLP protein. To determine the cross‐reactivity between different FRT pairs (1/6, 1/12 and 1/87) embryos derived from individual target lines in the inbred HC69 containing the FRT1/6, FRT1/12 and FRT1/87 pairs were bombarded with two different concentrations of FLP plasmid DNA (2.5 and 10 ng) respectively. Individual embryos were collected at two different times points, 3 days post‐treatment (3 DPT) or 6 DPT and qPCR assays were performed to capture the CT (threshold cycle) values which was used to determine the frequency of excision between different FRT pairs

| FRT site combinations and FLP plasmid DNA concentration | Mean CT value ± SD (3 DPT)* | Mean CT value ± SD (6 DPT)* | Percentage of events excised (3 DPT)† | Percentage of events excised (6 DPT)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRT1/87 (2.5) | 34.48 ± 1.2 | 33.15 ± 1.53 | 97.2 | 100 |

| FRT1/87 (10) | 32.39 ± 1.05 | 30.73 ± 0.85 | 100 | 100 |

| FRT1/6 (2.5) | 40 ± 0 | 38.93 ± 0.35 | 0 | 8.3 |

| FRT1/6 (10) | 38.19 ± 1.2 | 37.23 ± 1.08 | 30.5 | 36.1 |

| FRT1/12 (2.5) | 40 ± 0 | 40 ± 0 | 0 | 0 |

| FRT1/12 (10) | 40 ± 0 | 39.08 ± 0.13 | 0 | 8.3 |

Mean CT cycle with standard deviation values from three replicate experiments using a minimum 12 independent embryos each for the different FRT pairs (1/6, 1/12 and 1/87).

Percentage of the embryos identified as excised based on CT values in the pool of 36 embryos from different FRT pairs (1/6, 1/12 and 1/87) bombarded with FLP plasmid DNA (2.5 and 10 ng).

SSI across multiple RTLs

Using heterologous recombination sites, loxP/loxP5171 Louwerse and colleagues previously reported higher RMCE event recovery in Arabidopsis (Louwerse et al., 2007).

To evaluate the effect of heterologous FRT sites on RMCE frequency, we tested ≥ 6 independently generated RTL lines for three FRT pairs (1/6; 1/12 and 1/87) in the inbred HC69. Immature embryos were isolated and transformed with constructs containing corresponding donor DNA (donor DNAs 3, 4 or 5, Table S1) with the corresponding FRT pair. The three donor DNAs carried identical T‐DNAs, with the exception of the variable FRT pair. The transformation and RMCE frequencies are summarized in Table 4. We observed higher transformation frequencies in lines with FRT1/6 or FRT1/12 integration sites (22.5% and 19%, respectively) compared to the line with FRT1/87 integration site (4.6%). The higher transformation frequency led to a similar increase in RMCE frequency. The frequency of RMCE events was 3.5‐fold higher in lines with the FRT1/6 or FRT1/12 integration sites compared to the line with the FRT1/87 integration site. The RMCE frequencies (6.7%–6.9%) measured as proportion of the number of embryos infected are much higher than reported by Louwerse et al., 2007 using heterologous loxP sites. Noticeably >50% of the T0 events generated with FRT1/6 and FRT1/12 were RMCE events. The above data indicates the choice of FRT pair is important for RMCE frequency and that FRT pairs with lower cross‐reactivity improved RMCE event recovery in maize.

Table 4.

Effect of different FRT pairs on transformation frequency and RMCE frequency. For determining the effect of FRT pairs on SSI, embryos derived from ≥6 target lines in the inbred HC69 containing the FRT1/6, FRT1/12 and FRT1/87 pairs were transformed with corresponding donor cassette to determine the T0 transformation frequency and RMCE frequency

| FRT pair | Embryos (number) | T0 transformation frequency | RMCE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 events (number) | Frequency | |||

| 1/6 | 462 | 22.5% | 32 | 6.9% |

| 1/12 | 676 | 19.1% | 45 | 6.7% |

| 1/87 | 3218 | 4.6% | 39 | 1.2% |

Progeny analysis

From the SbS‐pass RMCE events, seven plants were selected and self‐fertilized in the greenhouse to enable segregation analysis. We evaluated T1 plants for zygosity of inserted transgene copy number (pmi and DsRed) using qPCR. Based on the segregation of the transgene copy number across the hemi, homo and null at T1 generation, all seven events showed the expected Mendelian inheritance of the transgenes in T1 generation (Table 5). In T1 generation, the plants homozygous for the transgene were selected and further selfed for seed increase. In subsequent generations none of the events showed any segregation of the transgene; they were homozygous fixed. These data confirmed the stable inheritance of the SSI locus.

Table 5.

Observed and expected number of homozygous, hemizygous and null plants for transgene copy number in seven SbS pass events with the Chi‐square values in T1 generation

| Event name | Null | Hemizygous | Homozygous | Chi‐square | P‐value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Expected | Observed | Expected | Observed | Expected | |||

| E10347.49.2.3, EA‐3007.68.2.9 | 18 | 25 | 54 | 50 | 27 | 25 | 2.45 | 0.293758 |

| E10347.87.3.1, EA‐3005.42.2.74 | 17 | 25 | 60 | 50 | 21 | 25 | 5.26 | 0.072078 |

| E10427.83.3.5, EA‐3005.41.2.10 | 21 | 25 | 50 | 50 | 27 | 25 | 0.77 | 0.680451 |

| E10602.22.5.2, EA‐2756.87.1.7 | 20 | 25 | 54 | 50 | 25 | 25 | 1.32 | 0.516851 |

| E9846.94.1.39, EA‐3390.04.2.2 | 22 | 25 | 53 | 50 | 26 | 25 | 0.56 | 0.755784 |

| E10347.25.1.5, EA‐2757.016.1.34 | 24 | 25 | 49 | 50 | 26 | 25 | 0.09 | 0.955997 |

| E10427.68.4.2, E9641.99.3.1 | 21 | 25 | 56 | 50 | 23 | 25 | 1.52 | 0.467666 |

Not statistically significant deviations from a 1 : 2 : 1 segregation at 5% level.

Discussion

More than 90% of the events generated using random transformation are unsuitable for product development because of low molecular quality or the genomic insertion site. Site‐specific integration provides a solution for targeting genes to a predefined and pre‐characterized genomic location. This approach generates events with consistent gene expression (Albert et al., 1995; Chawla et al., 2006). Additionally, this technology offers the potential to create complex trait loci with multiple sites in favourable genomic locations.

An efficient method for gene insertion in maize using Agrobacterium‐mediated SSI is described here. The method uses a previously described promoter‐trap system flanked by heterologous FRT sites (Li et al., 2009, 2010) for successful recovery of RMCE events in maize. The use of a promoter‐trap system for SSI was first demonstrated in tobacco (Albert et al., 1995) and its utility was further extended to other plants (Li et al., 2009; Louwerse et al., 2007; Vergunst et al., 1998). The majority of work on SSI in plants has used biolistic DNA delivery (Albert et al., 1995; Srivastava and Ow, 2002; Srivastava et al., 2004). Previously reported methods of SSI are of low efficiency and therefore have not been adopted for either gene optimization or product development. The SSI frequencies reported in crops ranged from 0.3 to 0.7 events per bombarded plate in rice (Nandy and Srivastava, 2011; Srivastava et al., 2004), and 0.5 to 1 event per bombardment plate in soybean (Li et al., 2009). Additionally, the nature of complex DNA insertions, integration of interspersed copies of DNA and modifications at the integration site (Altpeter et al., 2005; Kohli et al., 2003, 2010) contributed to the lack of adoption of SSI. Agrobacterium‐mediated SSI has been reported in the model systems of Arabidopsis and tobacco, but very few site‐specific T0 RMCE plants were obtained (Nanto et al., 2005; Vergunst and Hooykaas, 1998; Vergunst et al., 1998) which also limited its adoption.

We have developed an efficient Agrobacterium‐mediated SSI method in maize. Lines containing heterologous FRT integration sites and a promoter trap with a nptII gene were generated. The previously described promoter‐trap system was used to select events wherein the nptII gene in the target line is exchanged for a different selectable marker, in this case the pmi gene. In the development of this method, we evaluated different Agrobacterium strains, different vector designs, the use of morphogenic genes and different heterologous FRT pairs. Agrobacterium strain AGL1 resulted in higher transformation frequency and generated more RMCE events than strain LBA4404 (Table 1). AGL1, a super‐virulent strain, was previously shown to enhance transient T‐DNA delivery and transformation frequency in maize (Cho et al., 2014; Li et al., 2015). Perhaps, its higher level of DNA delivery contributes to its utility in SSI. We observed that the expression of the morphogenic genes Bbm and Wus2 improved frequency of transformation and recovery of RMCE events by 10‐fold, resulting in higher frequency RMCE events for both Agrobacterium strains AGL1 and LBA4404 THY‐. This observation is consistent with the earlier reports that co‐expression of morphogenic genes Bbm and Wus2 stimulates the growth of embryogenic callus resulting in improved transformation frequencies (Lowe et al., 2016). Our finding complements an earlier observation where introduction of a recombinase along with the ipt gene was shown to stimulate selective proliferation of transgenic cells and promoted recovery of RMCE events (Ebinuma et al., 2015). Our data also demonstrates that RMCE events can be recovered from transient expression of Bbm/Wus2 and flp, with no stable integration of these genes required.

The choice of heterologous FRT pair was demonstrated to be important for improving recovery of RMCE events. Umlauf and Cox (1988) showed that sequence changes in the spacer (8 bp) region of the FRT site can drastically reduce recombination without affecting recognition by the FLP protein. Spacer mutants with perfect self‐recombination, combined with a minimal cross‐reactivity seems to be important for enhancing RMCE (Turan et al., 2011). This was further validated by Lee and Saito (Lee and Saito, 1998) using spacer mutation sites loxP5171 which recombined with themselves but not with a wild‐type loxP site. Consistent with this earlier work, we observed that FRT cross‐reactivity was negatively correlated with RMCE frequency. Noticeably, we found that over 50% of the SSI events generated with FRT1/6 and FRT1/12 were perfect RMCE events containing the intact transgene sequence at the desired locus. This translates to a >50% increase in downstream process efficiency, since 50% of the T0 events are kept based on molecular attrition, compared to <10% using random transformation. Therefore, our preferred method uses the heterologous FRT1/6 pair for routine Agrobacterium‐mediated SSI in maize.

In conclusion, an efficient Agrobacterium‐mediated SSI strategy using the FLP‐FRT system in maize has been developed for routine transgenic event production. The application of this technology has been further extended to additional elite corn inbreds with heterologous FRT pairs. Our work establishes the use of FLP‐FRT system for generating high quality transgenic events in maize with no gene disruption at high frequencies with the potential to replace random transformation.

Materials and methods

DNA vector construction

DNA constructs used in the study are described in Table S1. The details of the genetic components used for vector construction is listed in Table S6. All the donor constructs were generated in the cointegrate vectors as previously described (Zhi et al., 2015) for maize transformation, while the morphogenic genes used in the two T‐DNA designs were built in a binary vector. The use of a promoter trap with FRT1 site upstream flanked by heterologous FRT pairs was used to aid in SSI event identification (switch in the selectable marker). Some materials reported in this paper contained reporter marker such as DsRed, AmCyan1 and selectable marker PMI owned by third parties. Similarly, some of the inbred lines and the target lines reported here are proprietary. Corteva will provide materials to academic investigators for non‐commercial research under an applicable material transfer agreement subject to proof of permission from any third‐party owners of all or parts of the material and governmental regulation considerations. Obtaining permission from third parties will be the responsibility of the requestor.

Maize transformation and molecular event characterization

Lines with heterologous FRT sites were generated in the elite inbreds HC69 and PH2RT via Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation using a construct containing ZmProUbi‐FRT1‐NptII::PinII + ZmUbiPro::AmCyan1::PinII‐FRT87 (additional FRT combinations included the same donor DNA but varying FRT pairs FRT1/6 and FRT1/12, Table S1). Only single copy, backbone‐free events were selected, subjected to SbS. The hemizygous embryos derived from the RTLs were used for Agrobacterium‐mediated SSI. Immature embryos derived from hemizygous RTL, GT6 in the elite genotype HC69 with FRT1/87 FRT sites was used for optimizing Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation. We additionally used an RTL from PH2RT to further demonstrate SSI in a different genotype.

For comparing heterologous FRT sites, we used ≥6 independent RTLs in the inbred HC69. Maize immature embryo transformation was performed using split ear transformation as described in Cho et al., 2014 with mannose selection. Putative RMCE events were screened for DsRed expression with a fluorescence microscope (Leica) followed by selecting the transformed calli on mannose media. For gene excision an inducible Rab17 promoter driving the expression of Cre recombinase was used. This promoter can be induced by osmotic stress or through desiccation (Vilardell et al., 1991). The putative transgenic events were desiccated overnight on dry filter paper before moving onto maturation media to induce Cre expression and excision of the morphogenic and cre genes. T0 transformation frequency was determined as the number of events (plantlet with roots) produced to the total number of embryos infected. Only a single healthy‐looking event per embryo was used for determining the transformation frequency and for molecular analysis.

For molecular analysis, genomic DNA extracted from leaf punches derived from T0 events and wild‐type plants was subjected to multiplex PCR assays to detect the presence/absence of random binary vector backbone (Wu et al., 2014) for random T‐DNA integration, qPCR assays for detecting the presence/absence of the accessory components (flp, cre and Bbm) and qPCR assays to confirm excision of the target gene (nptII) and integration of the donor genes (pmi and DsRed). Additionally, PCR assays spanning the Ubi‐FRT1 (FRT 5′) and FRT6/12/87‐ PinII (FRT 3′) junctions were performed to confirm the presence of both FRT junctions for final identification of the RMCE events (Figure 1c). The details of the primer probe used for molecular analysis to identify the intended RMCE are described in Table S5a. The transformants identified with the intended donor DNA insertions (RMCE) were subjected to Southern‐by‐Sequencing as previously described (Zastrow‐Hayes et al., 2015). Events with fully intact donor DNA flanked by the heterologous FRT pairs absent for unintended DNA sequence were identified as SbS pass events.

Agrobacterium tumefaciens culture conditions

Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains were grown on solidified or liquid AB Sucrose or yeast peptone medium (YP) or Luria Broth (LB) medium supplemented with appropriate antibiotics (rifampicin, 10 mg/L; spectinomycin, 100 mg/L; tetracycline 12.5 mg/L) at 28 °C. For plant transformation, Agrobacterium strains were streaked from glycerol stocks on AB sucrose media supplemented with appropriate antibiotics; one to three colonies were picked.

Determination of cross‐reactivity between various FRT pairs

For determining the effect of transient FLP delivery on heterologous FRT site cross‐reactivity, immature embryos derived from target site with FRT pairs (1/6, 1/12 and 1/87) were used. FLP plasmid DNA was either delivered using Agrobacterium or biolistic transformation (2.5 and 10 ng) and immature embryos collected at 3 and 6 days’ post‐treatment (DPT), replicated thrice and used for quantification. Specific PCR primer/probe were designed (ZmUbi:FRT3′, Figure 1d and Table S5b) to quantify the excision rates between the FRT pairs. A minimum of 12 individual embryos were collected per treatment following Agrobacterium infection or biolistic delivery at different time points (3 and 6 DPT), followed by qPCR for quantifying excision frequency between the FRT pairs. Normalized procedures including sample collection, extraction and probe‐based PCR were used to collect the CT (threshold cycle) values in order to determine whether cross‐reactivity was occurring. Data from CT values was only used to determine whether qPCR provided a signal for amplification or lack thereof. We chose not to use a normalizer (house‐keeping gene) to maintain robustness to capture the smallest amounts of any potential cross‐reactivity.

Conflict of Interest

AA, W.G‐K and EW are inventors on pending applications on this work and are current employees of Corteva Agriscience™ which owns the pending patent applications. ZL, ST, MA, BL, TJ and NDC are current employees of Corteva Agriscience™.

Author contribution

A.A., E.W., W.G‐K., T.J. and N.D.C conceived the research idea and designed research; Z.L. and S.T. conducted maize transformation; M.A., B.L. and A.A. contributed new reagents and supported vector construction; E.W. and A.A, performed data analysis; J.S.M conducted progeny analysis; A.A., T.J., and N.D.C. wrote the manuscript.

Supporting information

Table S1 Molecular characterization of the T0 SSI events generated from two different strains of Agrobacterium, AGL1 and LBA4404 THY‐.

Table S2 Molecular characterization of the T0 SSI events generated with and without morphogenic genes in the construct design for Agrobacterium‐mediated SSI.

Table S3 The impact of expression cassette arrangement within a single T‐DNA construct on transformation and RMCE frequencies in Agrobacterium‐mediated SSI in the target line GT6.

Table S4 The different FLP recognition target sites (FRT) and their sequences used in this study.

Table S5 Primer pairs and probe used in this study.

Table S6 Genetic elements used for generating expression cassettes within the T‐DNA.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kimberly Glassman, Visu Annaluru, Karri Klein and Super‐Vector team for their support with vector construction, Keith Lowe for technical support, Scott Betts with program support, Terry Hu and production transformation team members for their assistance in maize transformation. Special thanks to Tracy Fisher and Kara Califf for critical reading of the manuscript and art work.

References

- Afolabi, A.S. , Worland, B. , Snape, J.W. and Vain, P. (2004) A large‐scale study of rice plants transformed with different T‐DNAs provides new insights into locus composition and T‐DNA linkage configurations. Theor. Appl. Genet. 109, 815–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbudak, M.A. , More, A.B. , Nandy, S. and Srivastava, V. (2010) Dosage‐dependent gene expression from direct repeat locus in rice developed by site‐specific gene integration. Mol. Biotechnol. 45, 15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert, H. , Dale, E.C. , Lee, E. and Ow, D.W. (1995) Site‐specific integration of DNA into wild‐type and mutant lox sites placed in the plant genome. Plant J. 7, 649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altpeter, F. , Baisakh, N. , Beachy, R. , Bock, R. , Capell, T. , Christou, P. , Daniell, H. et al. (2005) Particle bombardment and the genetic enhancement of crops: myths and realities. Mol. Breed. 15, 305–327. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, A. and Jones, T.J. (2018) Advancing Agrobacterium‐based crop transformation and genome modification technology for agricultural biotechnology. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 418, 489–508. 10.1007/82_2018_97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand, A. , Bass, S.H. , Wu, E. , Wang, N. , McBride, K.E. , Annaluru, N. , Miller, M. et al. (2018) An improved ternary vector system for Agrobacterium‐mediated rapid maize transformation. Plant Mol. Biol. 97, 187–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardi, T. and Neal Stewart, C. (2016) Progress of targeted genome modification approaches in higher plants. Plant Cell Rep. 35, 1401–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, R. , Ariza‐Nieto, M. , Wilson, A.J. , Moore, S.K. and Srivastava, V. (2006) Transgene expression produced by biolistic‐mediated, site‐specific gene integration is consistently inherited by the subsequent generations. Plant Biotechnol. J. 4, 209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilcoat, D. , Liu, Z.B. and Sander, J. (2017) Use of CRISPR/Cas9 for crop improvement in maize and soybean. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 149, 27–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho, M.‐J. , Wu, E. , Kwan, J. , Yu, M. , Banh, J. , Linn, W. , Anand, A. et al. (2014) Agrobacterium‐mediated high‐frequency transformation of an elite commercial maize (Zea mays L.) inbred line. Plant Cell Rep. 33, 1767–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Buck, S. , Podevin, N. , Nolf, J. , Jacobs, A. and Depicker, A. (2009) The T‐DNA integration pattern in Arabidopsis transformants is highly determined by the transformed target cell. Plant J. 60, 134–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebinuma, H. , Nakahama, K. and Nanto, K. (2015) Enrichments of gene replacement events by Agrobacterium‐mediated recombinase‐mediated cassette exchange. Mol. Breed. 35, 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efsa, GMO Panel . (2011) EFSA guidance on the submission of applications for authorisation of genetically modified food and feed and genetically modified plants for food or feed uses under Regulation (EC) No 1829/2003. EFSA J. 9, 2311. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, S.L.A. , Kpodar, P. and DeLong, C.M.O. (1990) The effect of T‐DNA copy number, position and methylation on reporter gene expression in tobacco transformants. Plant Mol. Biol. 15, 851–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, M.A. , Anderson, D.J. and Birch, R.G. (2013) Comparison of Agrobacterium and particle bombardment using whole plasmid or minimal cassette for production of high‐expressing, low‐copy transgenic plants. Transgenic Res. 22, 143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.D.G. , Gilbert, D.E. , Grady, K.L. and Jorgensen, R.A. (1987) T‐DNA structure and gene expression in petunia plants transformed by Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 derivatives. Mol. Gen. Genet. 207, 478–485. [Google Scholar]

- Kohli, A. , Twyman, R.M. , Abranches, R. , Wegel, E. , Stoger, E. and Christou, P. (2003) Transgene integration, organization and interaction in plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 52, 247–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohli, A. , Miro, B. and Twyman, R.M. (2010) Transgene integration, expression and stability in plants: strategies for improvements. In Transgenic Crop Plants: Principles and Development ( Kole, C. , Michler, C.H. , Abbott, A.G. and Hall, T.C. , eds), pp. 201–237. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, G. and Saito, I. (1998) Role of nucleotide sequences of loxP spacer region in Cre‐mediated recombination. Gene, 216, 55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. , Xing, A. , Moon, B.P. , McCardell, R.P. , Mills, K. and Falco, S.C. (2009) Site‐specific integration of transgenes in soybean via recombinase‐mediated dna cassette exchange. Plant Physiol. 151, 1087–1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. , Moon, B.P. , Xing, A. , Liu, Z.‐B. , McCardell, R.P. , Damude, H.G. and Falco, S.C. (2010) Stacking multiple transgenes at a selected genomic site via repeated recombinase‐mediated DNA cassette exchanges. Plant Physiol. 154, 622–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. , Susan, T. , Sandra, M. , Maren, L.A. , James, C.R. III. , Jones, T.J. , Zuo‐Yu, Z. , et al. (2015) Effect of Agrobacterium strain and plasmid copy number on transformation frequency, event quality and usable event quality in an elite maize inbred. Plant Cell Rep. 34, 745–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louwerse, J.D. , van Lier, M.C.M. , van der Steen, D.M. , de Vlaam, C.M.T. , Hooykaas, P.J.J. and Vergunst, A.C. (2007) Stable recombinase‐mediated cassette exchange in arabidopsis using Agrobacterium tumefaciens . Plant Physiol. 145, 1282–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, K. , Wu, E. , Wang, N. , Hoerster, G. , Hastings, C. , Cho, M.‐J. , Scelonge, C. et al. (2016) Morphogenic regulators baby boom and Wuschel improve monocot transformation. Plant Cell, 28, 1998–2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyznik, L.A. , Gordon‐Kamm, W.J. and Tao, Y. (2003) Site‐specific recombination for genetic engineering in plants. Plant Cell Rep. 21, 925–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maessen, G.D.F. (1997) Genomic stability and stability of expression in genetically modified plants. Acta Bot. Neerl. 46, 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M. , Tagliani, L. , Wang, N. , Berka, B. , Bidney, D. and Zhao, Z.‐Y. (2002) High Efficiency transgene segregation in co‐transformed maize plants using an Agrobacterium tumefaciens 2 T‐DNA binary System. Transgenic Res. 11, 381–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandy, S. and Srivastava, V. (2011) Site‐specific gene integration in rice genome mediated by the FLP–FRT recombination system. Plant Biotechnol. J. 9, 713–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandy, S. and Srivastava, V. (2012) Marker‐free site‐specific gene integration in rice based on the use of two recombination systems. Plant Biotechnol. J. 10, 904–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanto, K. and Ebinuma, H. (2008) Marker‐free site‐specific integration plants. Transgenic Res. 17, 337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanto, K. , Yamada‐Watanabe, K. and Ebinuma, H. (2005) Agrobacterium‐mediated RMCE approach for gene replacement. Plant Biotechnol. J. 3, 203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanto, K. , Sato, K. , Katayama, Y. and Ebinuma, H. (2009) Expression of a transgene exchanged by the recombinase‐mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) method in plants. Plant Cell Rep. 28, 777–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ow, D.W. (2002) Recombinase‐directed plant transformation for the post‐genomic era. Plant Mol. Biol. 48, 183–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ow, D.W. (2007) GM maize from site‐specific recombination technology, what next? Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 18, 115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peach, C. and Velten, J. (1991) Transgene expression variability (position effect) of CAT and GUS reporter genes driven by linked divergent T‐DNA promoters. Plant Mol. Biol. 17, 49–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng, T. , Sun, X. and Mumm, R.H. (2014) Optimized breeding strategies for multiple trait integration: I. Minimizing linkage drag in single event introgression. Mol. Breed. 33, 89–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puchta, H. , Swoboda, P. and Hohn, B. (1994) Homologous recombination in plants. Experientia, 50, 277–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldo, A.R. and Ayliffe, M. (2015) Gene targeting and editing in crop plants: a new era of precision opportunities. Mol. Breed. 35, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Schlake, T. and Bode, J. (1994) Use of mutated FLP recognition target (FRT) sites for the exchange of expression cassettes at defined chromosomal loci. Biochemistry, 33, 12746–12751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, V. and Ow, D.W. (2002) Biolistic mediated site‐specific integration in rice. Mol. Breed. 8, 345–349. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, V. and Thomson, J. (2016) Gene stacking by recombinases. Plant Biotechnol. J. 14, 471–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, V. , Ariza‐Nieto, M. and Wilson, A.J. (2004) Cre‐mediated site‐specific gene integration for consistent transgene expression in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2, 169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, S.H. and Sax, J.K. (2016) Ending event‐based regulation of GMO crops. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X. and Mumm, R.H. (2015) Optimized breeding strategies for multiple trait integration: III. Parameters for success in version testing. Mol. Breed. 35, 201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada, R. , Urawa, H. , Inagaki, Y. , Tsugane, K. and Iida, S. (2002) Efficient gene targeting by homologous recombination in rice. Nat. Biotechnol. 20, 1030–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turan, S. , Kuehle, J. , Schambach, A. , Baum, C. and Bode, J. (2010) Multiplexing RMCE: versatile extensions of the Flp‐recombinase‐mediated cassette‐exchange technology. J. Mol. Biol. 402, 52–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turan, S. , Galla, M. , Ernst, E. , Qiao, J. , Voelkel, C. , Schiedlmeier, B. , Zehe, C. et al. (2011) Recombinase‐Mediated Cassette Exchange (RMCE): traditional concepts and current challenges. J. Mol. Biol. 407, 193–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turan, S. , Zehe, C. , Kuehle, J. , Qiao, J. and Bode, J. (2013) Recombinase‐mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) ‐A rapidly‐expanding toolbox for targeted genomic modifications. Gene, 515, 1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzfira, T. and White, C. (2005) Towards targeted mutagenesis and gene replacement in plants. Trends Biotechnol. 23, 567–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umlauf, S.W. and Cox, M.M. (1988) The functional significance of DNA sequence structure in a site‐specific genetic recombination reaction. EMBO J. 7, 1845–1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergunst, A.C. and Hooykaas, P.J. (1998) Cre/lox‐mediated site‐specific integration of Agrobacterium T‐DNA in Arabidopsis thaliana by transient expression of cre. Plant Mol. Biol. 38, 393–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergunst, A.C. , Jansen, L.E. and Hooykaas, P.J. (1998) Site‐specific integration of Agrobacterium T‐DNA in Arabidopsis thaliana mediated by Cre recombinase. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 2729–2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilardell, J. , Mundy, J. , Stilling, B. , Leroux, B. , Pla, M. , Freyssinet, G. and Pagès, M. (1991) Regulation of the maizerab17 gene promoter in transgenic heterologous systems. Plant Mol. Biol. 17, 985–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, E. , Lenderts, B. , Glassman, K. , Berezowska‐Kaniewska, M. , Christensen, H. , Asmus, T. , Zhen, S. et al. (2014) Optimized Agrobacterium‐mediated sorghum transformation protocol and molecular data of transgenic sorghum plants. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant, 50, 9–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zastrow‐Hayes, G.M. , Lin, H. , Sigmund, A.L. , Hoffman, J.L. , Alarcon, C.M. , Hayes, K.R. , Richmond, T.A. et al. (2015) Southern‐by‐Sequencing: a robust screening approach for molecular characterization of genetically modified crops. Plant Genome, 8, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhi, L. , TeRonde, S. , Meyer, S. , Arling, M.L. , Register, J.C. III , Zhao, Z.‐Y. , Jones, T.J. et al. (2015) Effect of Agrobacterium strain and plasmid copy number on transformation frequency, event quality and usable event quality in an elite maize cultivar. Plant Cell Rep. 34, 745–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Molecular characterization of the T0 SSI events generated from two different strains of Agrobacterium, AGL1 and LBA4404 THY‐.

Table S2 Molecular characterization of the T0 SSI events generated with and without morphogenic genes in the construct design for Agrobacterium‐mediated SSI.

Table S3 The impact of expression cassette arrangement within a single T‐DNA construct on transformation and RMCE frequencies in Agrobacterium‐mediated SSI in the target line GT6.

Table S4 The different FLP recognition target sites (FRT) and their sequences used in this study.

Table S5 Primer pairs and probe used in this study.

Table S6 Genetic elements used for generating expression cassettes within the T‐DNA.