Abstract

Salix wilsonii is an important ornamental willow tree widely distributed in China. In this study, an integrated circular chloroplast genome was reconstructed for S. wilsonii based on the chloroplast reads screened from the whole-genome sequencing data generated with the PacBio RSII platform. The obtained pseudomolecule was 155,750 bp long and had a typical quadripartite structure, comprising a large single copy region (LSC, 84,638 bp) and a small single copy region (SSC, 16,282 bp) separated by two inverted repeat regions (IR, 27,415 bp). The S. wilsonii chloroplast genome encoded 115 unique genes, including four rRNA genes, 30 tRNA genes, 78 protein-coding genes, and three pseudogenes. Repetitive sequence analysis identified 32 tandem repeats, 22 forward repeats, two reverse repeats, and five palindromic repeats. Additionally, a total of 118 perfect microsatellites were detected, with mononucleotide repeats being the most common (89.83%). By comparing the S. wilsonii chloroplast genome with those of other rosid plant species, significant contractions or expansions were identified at the IR-LSC/SSC borders. Phylogenetic analysis of 17 willow species confirmed that S. wilsonii was most closely related to S. chaenomeloides and revealed the monophyly of the genus Salix. The complete S. wilsonii chloroplast genome provides an additional sequence-based resource for studying the evolution of organelle genomes in woody plants.

1. Introduction

In plant, chloroplast is an essential organelle with its own genome and servers as the metabolic center involved in photosynthesis and other cellular functions, including the synthesis of starch, fatty acids, pigments, and amino acids [1]. In most land plants, the chloroplast (cp) genome has a circular quadripartite structure, comprising four major segments: two inverted repeat regions (IRa and IRb), a large single copy (LSC) region, and a small single copy (SSC) region. The gene content and order are highly conserved among land plants, with most genes involved in photosynthesis, transcription, and translation [1, 2]. Despite the overall conservation, during evolution, cp genomes have undergone extensive rearrangements within and between plant species, including gene/intron gains and losses, expansion and contraction of the IRs, and inversions [2, 3]. This information, which is revealed by comparisons of cp genomes, has been especially valuable for plant phylogenetic and evolutionary studies. The elucidation of the variations among cp genomes has also contributed to the characterization of chloroplast-to-nucleus gene transfer, which plays an important role in the evolution of eukaryotes. Furthermore, the uniparental inheritance of the cp genome (usually maternal in angiosperms and paternal in gymnosperms), accompanied by the general lack of heteroplasmy and recombination, has enabled researchers to evaluate the relative influences of seed and pollen dispersal on total gene flow [4].

In addition to increasing the available information from functional and evolutionary perspectives, chloroplast genomics research has important implications for chloroplast transformation, which has advantages over nuclear transformation, including enhanced transgene expression and lack of transgene escape via pollen [5]. Because of the rapid and cost-effective development of high-throughput sequencing technology, more than 2,000 complete cp genomes of land plants are now available in the NCBI Organelle Genome Resources database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/organelle/). Since the first report by Ferrarini et al. [6], the third-generation PacBio RS platform has been applied for sequencing the cp genomes of many plant species [7–11], confirming the utility of PacBio RS data for the sequencing and de novo assembly of cp genomes.

Willows (Salix L.) are economically and ecologically important woody plants because of their considerable biomass production and resistance to environmental stresses [12, 13]. Moreover, Salix L. represents one of the most taxonomically complex genera of flowering plants and comprises 330-500 species, including tall trees, shrubs, bushes, and prostrate plants [14, 15]. Despite the high species diversity, the cp genomes of only 15 Salix species have been sequenced (i.e., nine shrub and six tree species). Salix wilsonii, which is commonly referred to as Ziliu in China, is a deciduous tree that can grow up to 13 m tall. It is a representative of section Wilsonia, which consists of 15 species [16]. Being native to China, S. wilsonii is widely distributed in Huanan, Hubei, Jiangxi, Anhui, Zhejiang, and Jiangsu provinces [16]. Additionally, one-year-old branchlets of this tree have a dull brown surface and its young leaves appear slightly red. These attractive characteristics make S. wilsonii an important ornamental plant in Middle and Eastern China. As part of an ongoing project to sequence the S. wilsonii nuclear genome, we assembled and characterized the cp genome by screening for chloroplast reads in the data generated with the PacBio RSII platform. Analyzing the S. wilsonii cp genome will help researchers resolve the phylogenetic relationships among Salix species and clarify the evolution of cp genomes in the family Salicaceae.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chloroplast Reads Extraction and Assembly

Fresh and young leaves were collected from a single S. wilsonii tree on the campus of Nanjing Forestry University, Jiangsu, China. Total DNA was extracted using the CTAB method [17] and subjected to whole-genome sequencing with the PacBio RSII platform (NestOmics, Wuhan, China). The sequencing library was constructed according to the 20-kb template preparation protocol [18]. Approximately 31 Gb of clean data including 2.8 M high-quality long reads were obtained (unpublished data). By mapping the high-quality reads to the land plant cp genomes available in the NCBI Organelle Genome Resources database, S. wilsonii chloroplast reads were extracted with a BLASTN algorithm (e-value of 1e−5). The extracted reads were first filtered to remove repetitive and shorter reads (<15,000bp). The remaining reads were error-corrected, trimmed, and assembled de novo using Canu version 1.4 [19] with the corOutCoverage=100, genomeSize=150 Kb and all other parameters set as default. The complete S. wilsonii cp genome sequence was deposited in the GenBank database (accession number: MK603517).

2.2. Chloroplast Genome Annotation and Sequence Analyses

The resulting FASTA file containing the assembled S. wilsonii cp genome sequence was annotated with the DOGMA (https://dogma.ccbb.utexas.edu/). The percent identity cutoff for protein-coding genes and RNAs was set to 60 and 85, respectively. The start and stop codons were manually corrected to match the gene predictions. The identified tRNA genes were confirmed with tRNAscan-SE 1.21 [20]. Consequently, a circular cp genome map was obtained with the OGDRAW version 1.1 (http://ogdraw.mpimp-golm.mpg.de/), and the extent of the repeat and single copy regions was specified manually.

The GC content and relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) values were determined with MEGA 7.0.21 [21]. Microsatellite or simple sequence repeats (SSRs) with core motifs of 1-6 bp were detected with the Perl script program MISA (http://pgrc.ipk-gatersleben.de/misa/). The minimum repeat number was set to 8, 6, 4, 3, 3, and 3 for mono-, di-, tri-, tetra-, penta-, and hexanucleotides, respectively. Two SSRs separated by no more than 100 bp were treated as compound SSRs. Tandem repeats were analyzed using the tandem repeat finder (http://tandem.bu.edu/trf/trf.submit.options.html), with the following parameters: 2, 7, and 7 for match, mismatch and Indels, respectively; 50 and 500 for minimum alignment score to report repeat and maximum period size, respectively. Additionally, REPuter (http://bibiserv.techfak.uni-bielefeld.de/reputer/), with the minimal repeat size set to 30 bp and the Hamming distance set to 3, was used to identify dispersed repeats, including forward, palindromic, reverse, and complemented repeats.

2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis and Genome Comparison

All willow species with available cp genomes were included in the phylogenetic analysis. Populus tremula and Populus trichocarpa were used as the outgroup species. Phylogenetic trees based the whole cp genome sequences (genomic tree) and the coding sequences (CDS-tree) were constructed respectively. For the genomic tree, the complete cp genome sequences were first aligned using the MAFFT v7 [22], after which RAxML v8 was used to construct a maximum likelihood (ML) tree under the GTR+Γ model with 1000 bootstrap replicates [23]. The CDS-tree was generated using 55 protein-coding genes shared among the 18 species (16 Salix species and 2 Populus species). Specifically, ML trees for each gene were inferred separately with RAxML v8 [23], all of which were further used to infer the species tree with ASTRAL-III method [24]. The resulting species tree was visualized in FigTree 1.4.3 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/).

The mVISTA [25] was employed in the LAGAN mode to compare the cp genome of S. wilsonii with other Salix cp genomes. The annotation of Salix arbutifolia was used as a reference. The cp genomes for the following species were retrieved from the NCBI database: S. arbutifolia (NC_036718.1), Salix babylonica (NC_028350.1), Salix chaenomeloides (NC_037422.1), Salix hypoleuca (NC_037423.1), Salix interior (NC_024681.1), Salix magnifica (NC_037424.1), Salix minjiangensis (NC_037425.1), Salix oreinoma (NC_035743.1), Salix paraplesia (NC_037426.1), Salix purpurea (NC_029693.1), Salix rehderiana (NC_037427.1), Salix rorida (NC_037428.1), Salix suchowensis (NC_026462.1), Salix taoensis (NC_037429.1), Salix tetrasperma (NC_035744.1), P. tremula (NC_027425.1), P. trichocarpa (NC_009143.1), Stockwellia quadrifida (NC_022414.1), and Oenothera elata (NC_002693.2).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Assembly of the S. wilsonii cp Genome

A total of 42,633 chloroplast reads comprising 72,7581,388 nucleotides were extracted from the PacBio dataset. The reads were further filtered to remove repetitive and shorter sequences. Following correction and trimming, 505 PacBio RS reads were recovered containing 14,033,355 nucleotides (Table S1). The trimmed reads had a minimum length of 31,950 bp, a maximum length of 57,380 bp, and an N50 length of 35,004 bp. All of these reads were finally integrated into a complete circular pseudomolecule with a length of 155,750 bp long without any gap. The average depth of coverage of the S. wilsonii cp genome was approximately 90.1×.

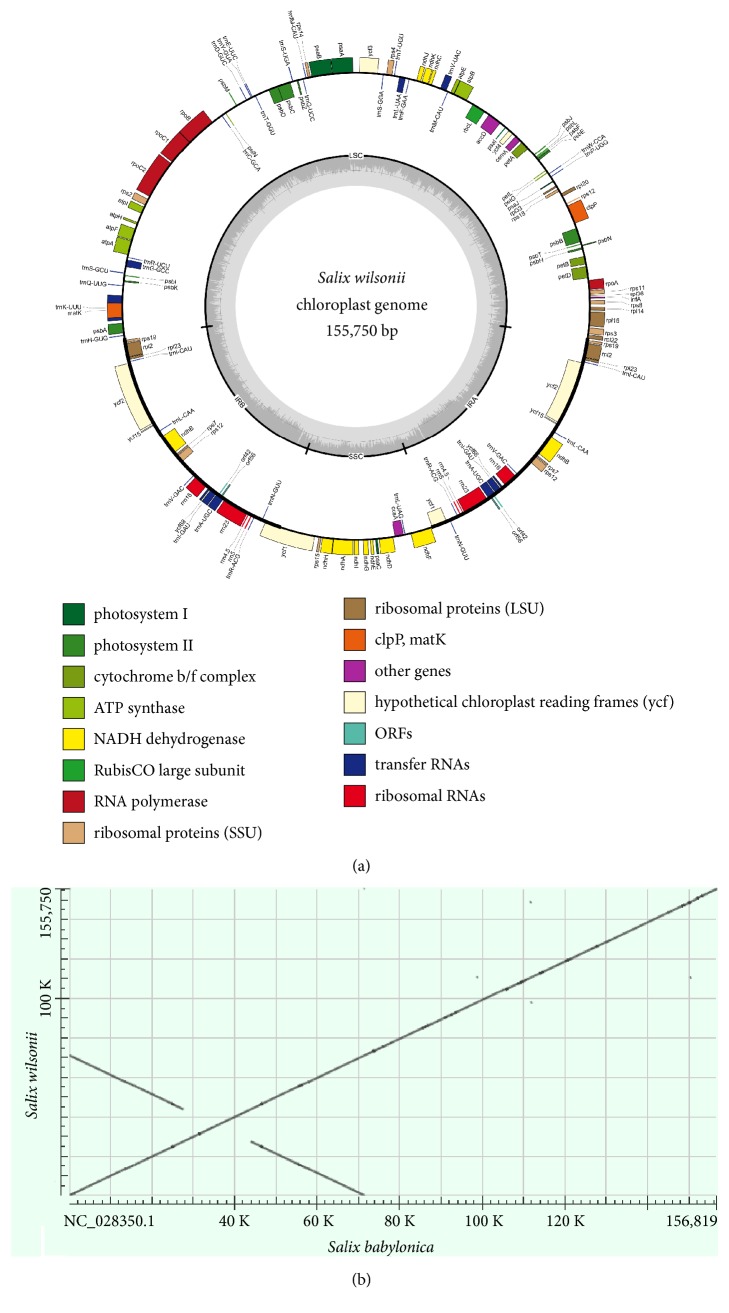

The size of the complete S. wilsonii cp genome was consistent with that of the cp genomes from the other sequenced Salix species (i.e., ranging from 154,977 bp in S. magnifica to 156,819 bp in S. babylonica) (Table S2). The assembled cp genome was a typical quadripartite molecule that included a pair of IRs (27,415 bp), an LSC region (84,638 bp), and an SSC region (16,282 bp) (Figure 1(a)). The overall GC content of the cp genome was 36.6%, and similar GC contents were calculated for the various willow species (Table S2). The GC content of the IR, LSC, and SSC region was 41.7%, 34.4%, and 31%, respectively. The observed higher GC content in the IR region was consistent with other angiosperm cp genomes [26, 27].

Figure 1.

Assembly of Salix wilsonii cp genome. (a) Gene map of the chloroplast genome of S. wilsonii. (b) Dot matrix alignment of cp genomes between S. wilsonii and S. babylonica.

To evaluate the assembly quality, S. wilsonii and S. babylonica cp genome sequences were aligned according to an established dot matrix method [28]. The result revealed excellent collinearity between the two cp genomes, and neither inversion nor translocation was detected (Figure 1(b)), thus confirming the high quality of our assembly.

3.2. Cp Genome Annotation and Gene Loss Analysis

The chloroplasts of land plants generally contain approximately 100-120 unique genes [1]. In the S. wilsonii cp genome, 115 unique genes were predicted and divided into the following four categories: 78 protein-coding genes, 30 tRNA genes, four rRNA genes, and three pseudogenes (Table 1). The rRNA genes, seven tRNA genes (trnA-UGC, trnI-CAU, trnI-GAU, trnL-CAA, trnN-GUU, trnR-ACG, and trnV-GAC) and 10 protein-coding genes (ndhB, rpl2, rpl23, rps7, rps19, ycf2, ycf15, pseudo-ycf68, orf42, and orf56) were duplicated in the IR regions. The relatively high GC contents in the rRNA and tRNA genes explained why the highest GC content was detected in the IR region. Additionally, 58 protein-coding and 22 tRNA genes were located in the LSC region, whereas 10 protein-coding genes (ccsA, ndhA, ndhD ndhE, ndhF, ndhG, ndhH, ndhI, psaC, and rps15) and one tRNA gene (trnL-UAG) were present in the SSC region. The genes rpl22 and ycf1 spanned the boundary of IRb/LSC and IRa/SSC, respectively. A sequence analysis revealed that 50.05%, 1.81%, and 5.77% of the genome sequences encoded proteins, tRNAs and rRNAs, respectively. The remaining 42.37% comprised introns or intergenic spacers.

Table 1.

Genes present in the cp genome of Salix wilsonii.

| Gene category | Group of genes | Name of genes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-replication | Ribosomal RNA genes | rrn16 | rrn23 | rrn4.5 | rrn5 | |

| Transfer RNA genes | trnA-UGC | trnC-GCA | trnD-GUC | trnE-UUC | trnF-GAA | |

| trnfM-CAU | trnG-GCC | trnG-UCC | trnH-GUG | trnI-CAU | ||

| trnI-GAU | trnK-UUU | trnL-CAA | trnL-UAA | trnL-UAG | ||

| trnM-CAU | trnN-GUU | trnP-UGG | trnQ-UUG | trnR-ACG | ||

| trnR-UCU | trnS-GCU | trnS-GGA | trnS-UGA | trnT-GGU | ||

| trnT-UGU | trnV-GAC | trnV-UAC | trnW-CCA | trnY-GUA | ||

| Large subunit of ribosome (LSU) | rpl2 | rpl14 | rpl16 | rpl20 | rpl22 | |

| rpl23 | rpl33 | rpl36 | ||||

| Small subunit of ribosome (SSU) | rps2 | rps3 | rps4 | rps7 | rps8 | |

| rps11 | rps12 | rps14 | rps15 | rps18 | ||

| rps19 | ||||||

| RNA polymerase | rpoA | rpoB | rpoC1 | rpoC2 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Genes for photosynthesis | Photosystem h | psaA | psaB | psaC | psaI | psaJ |

| Photosystem II | psbA | psbB | psbC | psbD | psbE | |

| psbF | psbH | psbI | psbJ | psbK | ||

| psbL | psbM | psbN | psbT | psbZ | ||

| Cytochrome b/f complex | petA | petB | petD | petG | petL | |

| petN | ||||||

| ATP synthase | atpA | atpB | atpE | atpF | atpH | |

| atpI | ||||||

| ATP-dependent protease subunit p | clpP | |||||

| Large subunit of rubisco | rbcL | |||||

| NADH dehydrogenase | ndhA | ndhB | ndhC | ndhD | ndhE | |

| ndhF | ndhG | ndhH | ndhI | ndhJ | ||

| ndhK | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Other genes | Maturase | matK | ||||

| Envelop membrane protein | cemA | |||||

| Subunit of acetyl-CoA-carboxylase | accD | |||||

| C-type cytochrome synthesis gene | ccsA | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Unknown function | Hypothetical chloroplast reading frames | ycf1 | ycf2 | ycf3 | ycf4 | ycf15 |

| orf42 | orf56 | |||||

| Pseudogene | pseudo-infA | pseudo-ycf68 | pseudo-ycf1 | |||

Two sets of ribosomal proteins, including 12 small ribosomal subunit proteins (encoded by rps genes) and nine large ribosomal subunit proteins (rpl genes), are commonly encoded in most plastid genomes [1]. We observed that two genes (rps16 and rpl32) were missing from the S. wilsonii cp genome. Although plastomes rarely lose rps and rpl genes [1], the rps16 and rpl32 genes are missing throughout the family Salicaceae. Furthermore, BLAST homology searches of the S. wilsonii nuclear genome (unpublished data) with the corresponding gene sequences from the Arabidopsis thaliana cp genome (NC_000932.1) as queries (GeneIDs: 844798 for rps16 and 844704 for rpl32) did not detect any fragments that matched these two genes. Thus, we suspected that rps16 and rpl32 were completely lost from the cell of S. wilsonii.

Two genes (infA and ycf68) were denoted as pseudogenes with truncated reading frames. The infA gene, which encodes the plastid translation initiation factor 1 (IF1), has been lost multiple times independently during the evolution of land plants and represents a classic example of chloroplast-to-nucleus gene transfer [29, 30]. The loss of infA was observed in the cp genomes of 11 Salicaceae species as well [31]. A functional and intact infA is still retained in the spinach chloroplast with a length of 234 bp (encoding 77 residues) [29]. The S. wilsonii pseudo-infA (159 bp) was identified in the LSC region with part of the gene being absent (Figure S1(A)). A TBLASTN search using the intact spinach chloroplast IF1 as a query revealed a candidate gene encoding cp IF1 in the S. wilsonii nuclear genome (unpublished data). The identified nuclear gene was predicted to encode a protein of 146 residues, which contained a long N-terminal extension comparing with the IF1 encoded by spinach cp genome (Figure S1(B)). The elongated N-terminal is also observed in other angiosperms, and it has been demonstrated to function as a chloroplast-targeting signal in soybean and Arabidopsis [29]. The pseudogenization of cp-infA and the intact nuclear-encoded IF1 identified in S. wilsonii strongly suggested the transfer of the infA gene from the chloroplast to the nuclear genome, which is a general occurrence during angiosperm evolution [29, 30].

The hypothetical gene ycf68, located in the trnI-GAU intron, was first identified as ORF133b in Oryza sativa [32]. A comparative analysis indicated that the pine and grass lineage gained ycf68 during the evolution of tracheophytes [33]. The ycf68 sequence is now considered as a cryptic reading frame that is widely conserved in several seed plants and liverwort species [34–37]. An alignment of the ycf68 sequences among 14 angiosperms indicated that ycf68 may be a functional protein-encoding gene in rice, corn, and Pinus species; however, in majority of cases, it is likely a nonfunctional gene because of numerous frameshifts and premature stop codons [34]. The cp genomes of Salicaceae species commonly carried sequences (approximately 380 bp) highly similar to the ycf68 ORF in the trnI-GAU intron, but they were not previously annotated. The S. wilsonii ycf68 sequence was highly homologous (92.45%) to the corresponding gene in O. sativa (NC_001320, Gene ID: 3131482), but many in-frame stop codons were found in the pseudo-ycf68 (Figure S2), resulting in a loss of function, which was consistent with the findings of previous studies [34, 36].

3.3. Codon Usage and Intron Loss Analysis

Based on the protein-coding genes, 25,899 codons were identified (excluding the stop codons). All genes had the canonical ATG start codon, except for ndh, which was started with ACG. The three most abundant amino acids were leucine (2,776; 10.72%), isoleucine (2,215; 8.55%), and serine (2,063; 7.97%), whereas cysteine (303; 1.17%) was the least abundant amino acid (Table 2). For amino acids coded by multiple codons, codon usage was biased toward A and U at the synonymous third position sites [38, 39], and a similar bias was observed in the S. wilsonii cp genome. Of the 29 preferred codons (RSCU > 1), 28 ended in an A or U. In contrast, among the 30 less frequently used codons (RSCU < 1), all but two ended in a G or C.

Table 2.

The relative synonymous codon usage in the Salix wilsonii cp genome.

| Amino | Codon | Number | RSCU∗ | Amino | Codon | Number | RSCU∗ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| acid | acid | ||||||

| Ala | GCU | 614 | 1.83 | Leu | UUA | 843 | 1.82 |

| GCA | 371 | 1.11 | CUU | 578 | 1.25 | ||

| GCC | 210 | 0.63 | UUG | 568 | 1.23 | ||

| GCG | 146 | 0.44 | CUA | 393 | 0.85 | ||

| Asn | AAU | 949 | 1.52 | CUC | 207 | 0.45 | |

| AAC | 299 | 0.48 | CUG | 187 | 0.4 | ||

| Asp | GAU | 808 | 1.57 | Lys | AAA | 972 | 1.44 |

| GAC | 223 | 0.43 | AAG | 374 | 0.56 | ||

| Arg | AGA | 482 | 1.87 | Met | AUG | 622 | 1 |

| CGA | 355 | 1.38 | Phe | UUU | 979 | 1.29 | |

| CGU | 321 | 1.24 | UUC | 543 | 0.71 | ||

| AGG | 164 | 0.64 | Pro | CCU | 424 | 1.56 | |

| CGG | 117 | 0.45 | CCA | 307 | 1.13 | ||

| CGC | 109 | 0.42 | CCC | 202 | 0.74 | ||

| Cys | UGU | 208 | 1.37 | CCG | 157 | 0.58 | |

| UGC | 95 | 0.63 | Ser | UCU | 574 | 1.67 | |

| Gln | CAA | 669 | 1.49 | AGU | 408 | 1.19 | |

| CAG | 228 | 0.51 | UCA | 404 | 1.17 | ||

| Gly | GGA | 706 | 1.58 | UCC | 341 | 0.99 | |

| GGU | 554 | 1.24 | UCG | 200 | 0.58 | ||

| GGG | 333 | 0.75 | AGC | 136 | 0.4 | ||

| GGC | 194 | 0.43 | Thr | ACU | 528 | 1.59 | |

| Glu | GAA | 1003 | 1.48 | ACA | 413 | 1.25 | |

| GAG | 352 | 0.52 | ACC | 248 | 0.75 | ||

| His | CAU | 471 | 1.51 | ACG | 136 | 0.41 | |

| CAC | 151 | 0.49 | Trp | UGG | 449 | 1 | |

| Ile | AUU | 1091 | 1.48 | Tyr | UAU | 782 | 1.64 |

| AUA | 682 | 0.92 | UAC | 174 | 0.36 | ||

| AUC | 442 | 0.6 | Val | GUA | 532 | 1.52 | |

| GUU | 500 | 1.43 | |||||

| GUG | 202 | 0.58 | |||||

| GUC | 169 | 0.48 |

Note: ∗ relative synonymous codon usage, RSCU.

The tRNA and protein-coding genes of typical angiosperm cp genomes contain 17-20 Group II introns [40]. Of the 115 unique genes identified in the S. wilsonii cp genome, 14 contained one intron and three (clpP, ycf3, and rps12) contained two introns (Table 3), giving a total of 19 introns. The rps12, which encodes the 30S ribosomal protein S12, was a transspliced gene with the 5′-end located in the LSC region and the duplicated 3′-end located in the IR regions. The trnK-UUU had the largest intron (2,558 bp), which contained the matK gene, and the petB had the smallest intron (221 bp).

Table 3.

Genes with introns in the cp genome of Salix wilsonii.

| Gene | Location | Exon I | Intron I | Exon II | Intron II | Exon III |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (bp) | (bp) | (bp) | (bp) | (bp) | ||

| atpF | LSC | 145 | 731 | 410 | ||

| clpP | LSC | 69 | 829 | 291 | 598 | 228 |

| ndhA | SSC | 564 | 1074 | 546 | ||

| ndhB | IR | 777 | 682 | 756 | ||

| petB | LSC | 5 | 221 | 643 | ||

| petD | LSC | 9 | 782 | 489 | ||

| rpl2 | IR | 399 | 629 | 471 | ||

| rpl16 | LSC | 9 | 1114 | 402 | ||

| rpoC1 | LSC | 453 | 779 | 1617 | ||

| rps12 | trans | 114 | - | 231 | 537 | 30 |

| trnA-UGC | IR | 38 | 800 | 35 | ||

| trnG-GCC | LSC | 23 | 703 | 48 | ||

| trnI-GAU | IR | 37 | 947 | 35 | ||

| trnK-UUU | LSC | 37 | 2558 | 29 | ||

| trnL-UAA | LSC | 37 | 583 | 50 | ||

| trnV-UAC | LSC | 39 | 607 | 37 | ||

| ycf3 | LSC | 129 | 722 | 228 | 716 | 153 |

Although intron content is generally conserved among land plant cp genomes, there are several cases of intron gains or losses during evolution [2, 5, 40]. Guisinger et al. [39] described the loss of an intron from a tRNA gene (trnG-UCC) in photosynthetic angiosperms (Geranium palmatum and Monsonia speciosa). In the S. wilsonii cp genome, the trnG-UCC gene also lacked an intron. Moreover, by surveying all 15 Salix cp genomes available in the NCBI database, we determined that the trnG-UCC intron, which appeared to be conserved across land plants [39], was absent from all willow cp genomes. The presence/absence of introns may provide valuable phylogenetic information and represents a potentially useful marker for resolving evolutionary relationships in many angiosperm lineages [41–43]. Therefore, future studies should clarify the distribution and phylogenetic utility of lost introns.

3.4. Repeat Sequence Analysis

Repeat sequences in cp genome contribute significantly to genomic structural variations, expansions, or rearrangements [1, 43]. An analysis of the repeat sequence in the S. wilsonii cp genome revealed 67 repeats, including 32 tandem repeats (sequence identity=100%) and 35 dispersed repeats (Table S3). The tandem repeat units were 11-25 bp long, and almost all of them were located in the intergenic spacer (IGS) regions. The three exceptions were located in the rpl16 or ycf3 intron regions. Among the dispersed repeats, 22 were forward repeats, two were reverse repeats, and 11 were palindromic repeats (Table S3). Most of the dispersed repeats were distributed in IGS regions, but some were detected in protein-coding genes.

Chloroplast simple sequence repeats (cpSSR) represent potentially useful markers for phylogenetic studies because of their haploid nature, relative lack of recombination, and uniparental inheritance [44]. We analyzed the type and distribution of SSRs in the S. wilsonii cp genome and detected 155 SSRs, including 118 perfect and 37 compound SSRs (Table 4). Among the perfect SSRs, there were 106, 1, 1, 8, and 2 for mono-, di-, tri-, tetra-, and pentanucleotide repeats, respectively. Hexanucleotide repeats were not detected. The longest repeat was 16 bp-stretch of A/T mononucleotides, and the major repeat unit was 8-10 bp (31 with 8 bp, 37 with 9 bp, and 18 with 10 bp), accounting for 72.9% (86/118) of all perfect SSRs. With one exception, all of the mononucleotide repeats consisted of A/T. Among the remaining 12 SSRs (repeat unit, 2-5 bp in length), seven contained only A and T bases (Table 4). The detection of AT-rich SSRs in the S. wilsonii cp genome was consistent with the findings in many other plant species [44]. The incidence of SSRs was proportional to the region size, with 110 in the LSC region, 18 in the IR region, and 27 in the SSC region. According to Ebert and Peakall [44], mononucleotide cpSSRs that located in a noncoding single copy (SC) region are more likely to exhibit intraspecies variation. We detected 94 mononucleotides distributed in noncoding SC regions of the S. wilsonii cp genome. These SSRs, together with the aforementioned tandem and dispersed repeats, may be useful for future ecological and evolutionary studies of willow species.

Table 4.

Numbers of SSRs identified in the cp genome of Salix wilsonii.

| SSR repeat type | SSR repeat unit | Number of repeats | Total | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |||

| Monomer | A/T | 31 | 36 | 18 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 105 | |||||

| C/G | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Dimer | TA | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Tripolymer | TAT | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Tetramer | AATG | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| AGAA | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| TAGA | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| TATT | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| TTCA | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| TTTA | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| TTTC | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Pentamer | AATTT | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| ATTAA | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Compound | 37 | |||||||||||||||

| Total | 155 | |||||||||||||||

3.5. Inverted Repeat Contraction and Expansion

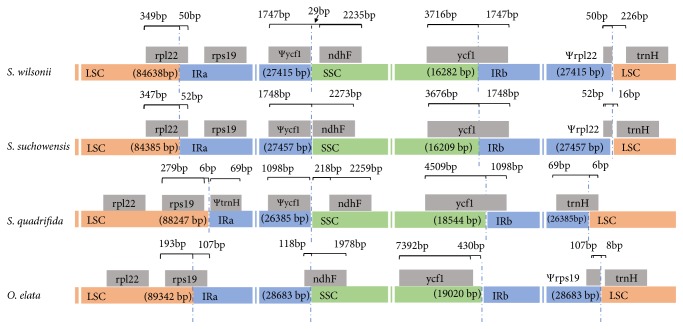

The IR regions, which are frequently subject to expansion, contraction, or even complete loss, play an important role for plastome stability and evolution [1, 45]. An examination of the IR boundary shifts may lead to a more thorough characterization of species-specific phylogenetic history. In this study, we compared the IR/SC boundaries of four rosid plants: S. suchowensis, S. wilsonii, S. quadrifida, and O. elata, which represent three different families (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of IR boundaries among the cp genomes of four rosid plants. “Ψ” means pseudogene.

The IR region length ranged from 26,385 bp to 28,683 bp, and some expansions/contractions of the IR regions were observed. Similar to most eudicot plastomes [46, 47], the IRa/LSC border in O. elata lied within the rps19 gene, resulting in a Ψrps19 (107 bp) at the IRb/LSC boundary (Figure 2). In S. quadrifida, the IRa region was detected adjacent to the rps19 gene, and no pseudogene was detected at the IRb/LSC border. However, in both analyzed Salix species, the IRa/LSC junction expanded to partially include the rpl22 gene, creating a Ψrpl22 (approximately 50 bp) at the IRb/LSC boundary. The IRb/LSC junctions were located downstream of trnH (8-226 bp) in the examined species, except for the S. quadrifida, in which the trnH gene was incorporated in the IRb region, with 69 bp of this gene duplicated in the IRa region.

The IRb/SSC borders in both Salix species were located within ycf1. Thus, a Ψycf1 was identified at the IRa/SSC border (1,747 bp in S. wilsonii and 1,748 bp in S. suchowensis). A portion of the ndhF gene reportedly overlapped with Ψycf1 (140 bp) in S. suchowensis [48]. Moreover, the IRa/SSC border was located downstream of ndhF in S. wilsonii (29 bp). In S. quadrifida, ycf1 also spanned the IRb/SSC junction; the IRa/SSC border was located downstream of ndhF, with 218 bp between Ψycf1 and ndhF. Regarding O. elata, the IRa/SSC border was located within ndhF and the IRb/SSC boundary was located 430 bp from ycf1, which was inconsistent with the findings for most angiosperms [34, 47]. Changes in IR extent are the main factor affecting variations in overall plastome size and the number of genes [47]. Several elegant models have been proposed to explain the mechanisms underlying IR boundary shifts. These models involve gene conversions, double-strand breaks, and genomic deletions [49]. Future investigations should explore the conservation and evolutionary dynamics of the IR region among Salicaceae plants.

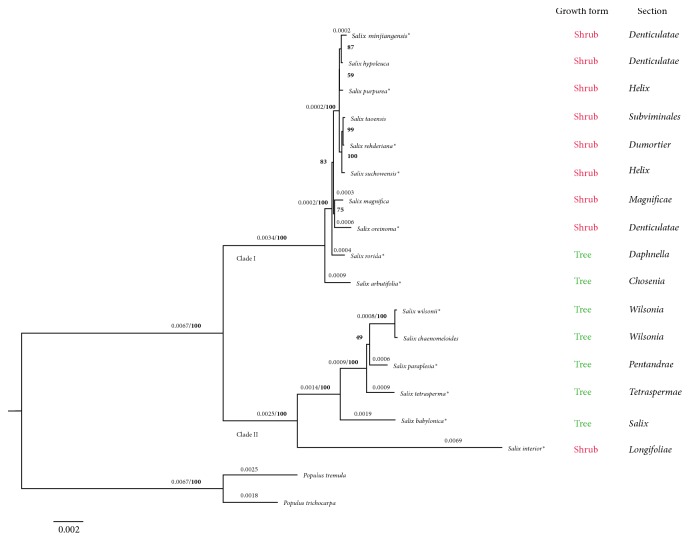

3.6. Phylogenetic Relationships and Comparative Analysis among Salix Species

The taxonomy and phylogenetic relationships of the genus Salix based on morphology are extremely difficult due to the scarceness of informative morphological characters [50]. Furthermore, the dioecious reproduction and common interspecific hybridization of Salix species also complicate the traditional phenotypic characterization [50, 51]. The cp genomes have been proven highly effective for inferring the phylogenetic relationships in numerous plant groups. To elucidate the phylogenetic position of S. wilsonii, a ML tree was constructed based on the complete cp genome sequences of 16 Salix species belonging to 13 different sections according to the Flora of China [16]. As shown in Figure 3, all the willow species were monophyletic and were evidently separated into two major clades with full support. The S. wilsonii and S. chaenomeloides from section Wilsonia formed a monophyletic group in Clade II. A CDS-tree based on was also constructed by using 55 protein-coding genes shared among the analyzed species The overall topology of the CDS-tree was very similar to that of the genomic tree; only some incongruence was found among the relationships of seven shrub willows, including S. taoensis, S. hypoleuca, S. rehderiana, S. minjiangensis, S. purpurea, S. suchowensis, and S. magnifica (Figure S3).

Figure 3.

Maximum likelihood tree of willows and outgroups based on whole cp genome sequences. The branch length (≥0.0002) and the bootstrap value that supported each node (in bold) are shown above the branch. ∗ indicates the species selected for genome comparison analysis.

Although several molecular phylogenetic studies of the genus Salix have been published, most of them were carried out with nuclear internal transcribed spacers or a few chloroplast DNA regions [15, 50, 52–54]. Two phylogenetic analyses focused on the relationships of the genera Salix and Populus were recently conducted with the chloroplast protein-coding gene dataset and complete cp genome, respectively [31, 55]. Considering the limited number of Salix species involved in Huang et al.'s study [31], we compared the relationships resolved in the genomic tree with those reported by Zhang et al. [55]. Overall, the two main clades formed within the genus Salix were generally consistent, but some inconsistences were observed among the interspecific relationships in each clade. These inconsistencies may have been due to the use of different datasets during the phylogenetic analysis, since the phylogenetic relationships presented in Clade I of our CDS-tree (Figure S3) were almost the same with that of Zhang et al.

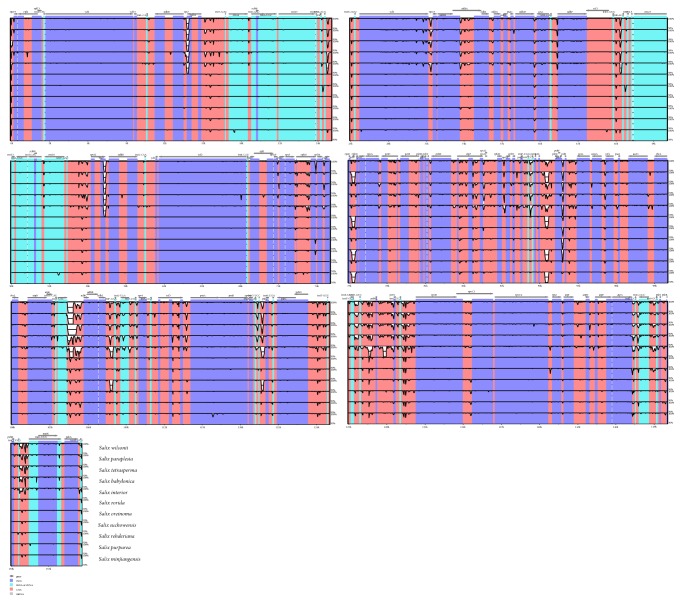

In order to compare the sequence variation within the genus Salix, the whole cp genomes of 12 Salix species were aligned using mVISTA with S. arbutifolia as a reference (Figure 4). The results revealed high sequence similarity across the willow cp genomes. Consistent with other angiosperms [56, 57], the IR regions were more conserved than the LSC and SSC regions, and the noncoding regions were more divergent than the coding regions. Based on the alignment, the highly divergent regions were detected in the IGS regions: ycf1-rps15, trnNGUU-trnRACG, trnVGAC-rps12, rps7-ndhB, rpl14-rps8, rps8-infA, rpoA-petD, psbB-clpP, rpl20-rpl18, rpl33-psaJ, trnPUGG-trnWCCA, petL-psbE, psbL-petA, cemA-ycf4, ycf4-psaI, rbcL-accD, trnVUAC-ndhC, ndhJ-trnFGAA, trnLUAA-trnTUGU, trnTUGU-rps4, ycf3-psaA, trnfM-trnGUCC, trnGUCC-psbZ, psbD-TrnTGGU, trnYGUA-trnDGUC, trnDGUC-psbM, psbM-psbN, trnCGCA-rpoB, trnGGCC-trnSGCU, trnQUUG-trnKUUU, and psbA-trnHGUG. For the coding regions, the more divergent regions were found in rps7, ycf1, and matK. These highly variable regions can be used to develop more informative DNA barcodes and facilitate phylogenic analysis among Salix species.

Figure 4.

Complete chloroplast genome comparison of 12 Salix species using mVISTA program with S. arbutifolia as a reference. Cp genome regions are color-coded as protein-coding (exon), rRNA, tRNA, and conserved noncoding sequences (CNS).

4. Conclusions

In this study, we assembled and characterized the complete cp genome of S. wilsonii, which is an endemic and ornamental willow tree in China. The S. wilsonii cp genome was structurally and organizationally similar to the cp genomes of other Salix species. Significant shifts in the IR boundaries were revealed in comparison with the cp genomes from three other rosid plant species. An analysis of the phylogenetic relationships among 16 willow species indicated S. wilsonii and S. chaenomeloides were sister species and revealed the monophyly of the genus Salix. The complete S. wilsonii cp genome represents a useful sequence-based resource which can be further applied for phylogenetic and evolutionary studies in woody plants.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Key Research and Development Plant of China (2016YFD0600101), the Youth Elite Science Sponsorship Program by CAST (YESS20160121), the Qing Lan Talent Support Program at Jiangsu Province, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (031010156).

Data Availability

The cp genome data used to support the study findings are included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Authors' Contributions

Yingnan Chen and Nan Hu contributed equally to this work.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: statistics for the assembly of the Salix wilsonii cp genome.

Table S2: features of chloroplast genomes from 16 Salix species.

Table S3: statistics of repeat sequences in the Salix wilsonii cp genome.

Figure S1: pairwise and multiple sequence alignment. (A) Pairwise alignment of the infA genes from cp genomes of Spinacia oleracea (AF206521) and Salix wilsonii. (B) Multiple alignment of IF1 protein sequences. The accession numbers for these proteins are NP_192856.1 (Arabidopsis thaliana), AAK38870.1 (soybean, Glycine max), NP_054969 (spinach, Spinacia oleracea), and Salix wilsonii (EVM0016759.1, unpublished data). cp, chloroplast; nuc, nuclear.

Figure S2: alignment of the ycf68 genes from Oryza sativa and Salix wilsonii. Red boxes indicate in-frame stop codons.

Figure S3: the phylogenetic tree based on 55 protein-coding genes of 16 Salix and two Populus species. The branch length was shown on the branch and the branch support value (in bold) was shown at the node.

References

- 1.Wicke S., Schneeweiss G. M., dePamphilis C. W., Müller K. F., Quandt D. The evolution of the plastid chromosome in land plants: gene content, gene order, gene function. Plant Molecular Biology. 2011;76(3-5):273–297. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9762-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jansen R. K., Raubeson L. A., Boore J. L., et al. Molecular Evolution: Producing the Biochemical Data. Vol. 395. Elsevier; 2005. Methods for obtaining and analyzing whole chloroplast genome sequences; pp. 348–384. (Methods in Enzymology). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sloan D. B., Triant D. A., Forrester N. J., Bergner L. M., Wu M., Taylor D. R. A recurring syndrome of accelerated plastid genome evolution in the angiosperm tribe Sileneae (Caryophyllaceae) Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2014;72:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCauley D. E. The use of chloroplast DNA polymorphism in studies of gene flow in plants. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 1995;10(5):198–202. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(00)89052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniell H., Lin C. S., Yu M., Chang W. J. Chloroplast genomes: diversity, evolution, and applications in genetic engineering. Genome Biology. 2016;17, article 134 doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1004-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrarini M., Moretto M., Ward J. A., et al. An evaluation of the PacBio RS platform for sequencing and de novo assembly of a chloroplast genome. BMC Genomics. 2013;14(1, article 670) doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen X. C., Li Q. S., Li Y., Qian J., Han J. P. Chloroplast genome of Aconitum barbatum var. puberulum (Ranunculaceae) derived from CCS reads using the PacBio RS platform. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2015;6, article 42 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stadermann K. B., Weisshaar B., Holtgräwe D. SMRT sequencing only de novo assembly of the sugar beet (Beta vulgaris) chloroplast genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2015;16(1, article 295) doi: 10.1186/s12859-015-0726-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ni L. H., Zhao Z. L., Xu H. X., Chen S. L., Dorje G. The complete chloroplast genome of Gentiana straminea (Gentianaceae), an endemic species to the Sino-Himalayan subregion. Gene. 2016;577(2):281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiang B., Li X., Qian J., et al. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of the medicinal plant swertia mussotii using the pacbio RS II platform. Molecules. 2016;21(8, article 1029) doi: 10.3390/molecules21081029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin M., Qi X., Chen J., et al. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Actinidia arguta using the PacBio RS II platform. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197393.e0197393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuzovkina Y. A., Weih M., Romero M. A., et al. Salix: botany and global horticulture. In: Janick J., editor. Horticultural Reviews. Vol. 34. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2008. pp. 447–489. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smart L. B., Cameron K. D. Genetic improvement of willow (Salix spp.) as a dedicated bioenergy crop. In: Vermerris W. E., editor. Genetic Improvement of Bioenergy Crops. New York, NY, USA: Springer -Verlag; 2008. pp. 377–396. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karp A., Hanley S. J., Trybush S. O., Macalpine W., Pei M., Shield I. Genetic improvement of willow for bioenergy and biofuels. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology. 2011;53(2):151–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.01015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barkalov V. Y., Kozyrenko M. M. Phylogenetic relationships of Salix L. subg. Salix species (Salicaceae) according to sequencing data of intergenic spacers of the chloroplast genome and ITS rDNA. Russian Journal of Genetics. 2014;50(8):828–837. doi: 10.1134/S1022795414070035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang C., Zha S., Skvortsov A. K. Salix linnaeus. In: Wu Z. Y., Raven P. H., Hong D., editors. Flora of China. Vol. 4. Beijing, China: Science Press & Missouri Botanical Garden; 1999. pp. 162–274. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray M. G., Thompson W. F. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Research. 1980;8(19):4321–4326. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.19.4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Procedure & Checklist—20 Kb Template Preparation Using Bluepippin™ Size Selection System. Pacific Biosciences; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koren S., Walenz B. P., Berlin K., Miller J. R., Bergman N. H., Phillippy A. M. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Research. 2017;27(5):722–736. doi: 10.1101/gr.215087.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schattner P., Brooks A. N., Lowe T. M. The tRNAscan-SE, snoscan and snoGPS web servers for the detection of tRNAs and snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Research. 2005;33(2):W686–W689. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2016;33(7):1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katoh K., Standley D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2013;30(4):772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(9):1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang C., Rabiee M., Sayyari E., Mirarab S. ASTRAL-III: polynomial time species tree reconstruction from partially resolved gene trees. BMC Bioinformatics. 2018;19(S6, article 153) doi: 10.1186/s12859-018-2129-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayor C., Brudno M., Schwartz J. R., et al. VISTA : visualizing global DNA sequence alignments of arbitrary length. Bioinformatics. 2000;16(11):1046–1047. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.11.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nie X., Deng P., Feng K., et al. Comparative analysis of codon usage patterns in chloroplast genomes of the asteraceae family. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter. 2014;32(4):828–840. doi: 10.1007/s11105-013-0691-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu W., Kong H., Zhou J., Fritsch P., Hao G., Gong W. Complete Chloroplast Genome of Cercis chuniana (Fabaceae) with Structural and Genetic Comparison to Six Species in Caesalpinioideae. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018;19(5, article 1286) doi: 10.3390/ijms19051286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Z., Schwartz S., Wagner L., Miller W. A greedy algorithm for aligning DNA sequences. Journal of Computational Biology. 2000;7(1-2):203–214. doi: 10.1089/10665270050081478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Millen R. S., Olmstead R. G., Adams K. L., et al. Many parallel losses of infA from chloroplast DNA during angiosperm evolution with multiple independent transfers to the nucleus. The Plant Cell. 2001;13(3):645–658. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.3.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jansen R. K., Cai Z., Raubeson L. A., et al. Analysis of 81 genes from 64 plastid genomes resolves relationships in angiosperms and identifies genome-scale evolutionary patterns. Proceedings of the National Acadamy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(49):19369–19374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709121104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang Y., Wang J., Yang Y., Fan C., Chen J. Phylogenomic analysis and dynamic evolution of chloroplast genomes in salicaceae. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2017;8, article 1050 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stoebe B., Martin W., Kowallik K. V. Distribution and nomenclature of protein-coding genes in 12 sequenced chloroplast genomes. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter. 1998;16(3):243–255. doi: 10.1023/A:1007568326120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chaw S. M., Chang C. C., Chen H. L., Li W. H. Dating the monocotdicot divergence and the origin of core eudicots using whole chloroplast genomes. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 2004;58:424–441. doi: 10.1007/s00239-003-2564-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raubeson L. A., Peery R., Chumley T. W., et al. Comparative chloroplast genomics: analyses including new sequences from the angiosperms nuphar advena and ranunculus macranthus. BMC Genomics. 2007;8(1, article 174) doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wickett N. J., Zhang Y., Hansen S. K., et al. Functional gene losses occur with minimal size reduction in the plastid genome of the parasitic liverwort aneura mirabilis. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2008;25(2):393–401. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Su H.-J., Hogenhout S. A., Al-Sadi A. M., Kuo C.-H. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of omani lime (Citrus aurantiifolia) and comparative analysis within the rosids. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113049.e113049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Menezes A. P., Resende-Moreira L. C., Buzatti R. S., et al. Chloroplast genomes of Byrsonima species (Malpighiaceae): comparative analysis and screening of high divergence sequences. Scientific Reports. 2018;8(1, article 2210) doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20189-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Q., Xue Q. Comparative studies on codon usage pattern of chloroplasts and their host nuclear genes in four plant species. Journal of Genetics. 2005;84(1):55–62. doi: 10.1007/BF02715890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guisinger M. M., Kuehl J. V., Boore J. L., Jansen R. K. Extreme reconfiguration of plastid genomes in the angiosperm family Geraniaceae: rearrangements, repeats, and codon usage. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2010;28:583–600. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Daniell H., Wurdack K. J., Kanagaraj A., Lee S. B., Saski C., Jansen R. K. The complete nucleotide sequence of the cassava (Manihot esculenta) chloroplast genome and the evolution of atpF in malpighiales: RNA editing and multiple losses of a group II intron. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2008;116(5):723–737. doi: 10.1007/s00122-007-0706-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Downie S. R., Olmstead R. G., Zurawski G., et al. Six independent losses of the chloroplast DNA rpl2 intron in dicotyledons: molecular and phylogenetic implications. Evolution. 1991;45(5):1245–1259. doi: 10.2307/2409731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jansen R. K., Wojciechowski M. F., Sanniyasi E., Lee S., Daniell H. Complete plastid genome sequence of the chickpea (Cicer arietinum) and the phylogenetic distribution of rps12 and clpP intron losses among legumes (Leguminosae) Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2008;48(3):1204–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maréchal A., Brisson N. Recombination and the maintenance of plant organelle genome stability. New Phytologist. 2010;186(2):299–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ebert D., Peakall R. Chloroplast simple sequence repeats (cpSSRs): technical resources and recommendations for expanding cpSSR discovery and applications to a wide array of plant species. Molecular Ecology Resources. 2009;9(3):673–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2008.02319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu A., Guo W., Gupta S., Fan W., Mower J. P. Evolutionary dynamics of the plastid inverted repeat: the effects of expansion, contraction, and loss on substitution rates. New Phytologist. 2016;209(4):1747–1756. doi: 10.1111/nph.13743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Downie S. R., Jansen R. K. A comparative analysis of whole plastid genomes from the apiales: expansion and contraction of the inverted repeat, mitochondrial to plastid transfer of DNA, and identification of highly divergent noncoding regions. Systematic Botany. 2015;40(1):336–351. doi: 10.1600/036364415X686620. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun Y., Moore M. J., Zhang S., et al. Phylogenomic and structural analyses of 18 complete plastomes across nearly all families of early-diverging eudicots, including an angiosperm-wide analysis of IR gene content evolution. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2016;96:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun C., Li J., Dai X., Chen Y. Analysis and characterization of the Salix suchowensis chloroplast genome. Journal of Forestry Research. 2018;29(4):1003–1011. doi: 10.1007/s11676-017-0531-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park S., An B., Park S. Reconfiguration of the plastid genome in Lamprocapnos spectabilis: IR boundary shifting, inversion, and intraspecific variation. Scientific Reports. 2018;8(1, article 13568) doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31938-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu J., Nyman T., Wang D., Argus G. W., Yang Y., Chen J. Phylogeny of Salix subgenus Salix s.l. (Salicaceae): delimitation, biogeography, and reticulate evolution. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2015;15(1):31–43. doi: 10.1186/s12862-015-0311-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rechinger K. H. Salix taxonomy in Europe–problems, interpretations, observations. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Section B. Biological Sciences. 1992;98:1–12. doi: 10.1017/S0269727000007417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Azuma T., Kajita T., Yokoyama J., Ohashi H. Phylogenetic relationships of Salix (Salicaceae) based on rbcL sequence data. American Journal of Botany. 2000;87(1):67–75. doi: 10.2307/2656686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen J. H., Sun H., Wen J., Yang Y. P. Molecular phylogeny of Salix L. (Salicaceae) inferred from three chloroplast datasets and its systematic implications. TAXON. 2010;59(1):29–37. doi: 10.1002/tax.591004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lauron-Moreau A., Pitre F. E., Argus G. W., Labrecque M., Brouillet L., Lumbsch H. T. Phylogenetic Relationships of American Willows (Salix L., Salicaceae) PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121965.e0121965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang L., Xi Z., Wang M., Guo X., Ma T. Plastome phylogeny and lineage diversification of Salicaceae with focus on poplars and willows. Ecology and Evolution. 2018;8(16):7817–7823. doi: 10.1002/ece3.4261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li R., Ma P., Wen J., Yi T., Sarkar I. N. Complete sequencing of five araliaceae chloroplast genomes and the phylogenetic implications. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078568.e78568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Park I., Kim W., Yang S., et al. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of aconitum coreanum and aconitum carmichaelii and comparative analysis with other aconitum species. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184257.e0184257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: statistics for the assembly of the Salix wilsonii cp genome.

Table S2: features of chloroplast genomes from 16 Salix species.

Table S3: statistics of repeat sequences in the Salix wilsonii cp genome.

Figure S1: pairwise and multiple sequence alignment. (A) Pairwise alignment of the infA genes from cp genomes of Spinacia oleracea (AF206521) and Salix wilsonii. (B) Multiple alignment of IF1 protein sequences. The accession numbers for these proteins are NP_192856.1 (Arabidopsis thaliana), AAK38870.1 (soybean, Glycine max), NP_054969 (spinach, Spinacia oleracea), and Salix wilsonii (EVM0016759.1, unpublished data). cp, chloroplast; nuc, nuclear.

Figure S2: alignment of the ycf68 genes from Oryza sativa and Salix wilsonii. Red boxes indicate in-frame stop codons.

Figure S3: the phylogenetic tree based on 55 protein-coding genes of 16 Salix and two Populus species. The branch length was shown on the branch and the branch support value (in bold) was shown at the node.

Data Availability Statement

The cp genome data used to support the study findings are included in the article.