Abstract

Introduction:

Little is known regarding how human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal cancer (HPV-OPC) patient goals change with treatment. This study evaluates whether patient ranking of non-oncologic priorities relative to cure and survival shift after treatment as compared to priorities at diagnosis.

Materials and Methods:

This is a prospective study of HPV-OPC patient survey responses at diagnosis and after treatment. The relative importance of 12 treatment-related priorities was ranked on an ordinal scale (1 as highest). Median rank (MR) was compared using Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank tests. Prevalence of high concern for 11 treatment-related issues was compared using paired t-test. The effect of patient characteristics on change in priority rank and concern was evaluated using linear regression.

Results:

Among 37 patients, patient priorities were generally unchanged after treatment compared with at diagnosis, with cure and survival persistently ranked top priority. Having a moist mouth uniquely rose in importance after treatment. Patient characteristics largely did not affect change in priority rank. Concerns decreased after treatment, except concern regarding recurrence.

Discussion:

Treatment-related priorities are largely similar at diagnosis and after treatment regardless of patient characteristics. The treatment experience does not result in a shift of priorities from cure and survival to non-oncologic domains over cure and survival. The rise in importance of moist mouth implies that xerostomia may have been underappreciated as a sequelae of treatment. A decrease in most treatment-related concerns is encouraging, whereas the persistence of specific areas of concern may inform patient counseling.

Keywords: patient preference, decision-making, HPV, head and neck neoplasms, oropharyngeal neoplasms

Introduction:

The incidence of human papillomavirus- associated oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer (HPV-OPC) is rising in many developed countries [1], and is known to have an improved prognosis compared with HPV-unassociated head and neck cancers [2]. Deintensified treatment regimens are currently under evaluation in clinical trials with the overall aim of reducing toxicity, for example dysphagia, while maintaining excellent oncologic outcomes for favorable-risk groups [3, 4]. Although deintensification focuses on long-term patient function and quality of life, there is a paucity of literature regarding patient preference in treatment for HPV-OPC. Specifically, it is unclear how patients view the relative importance of oncologic outcomes compared with non-oncologic outcomes that relate to eating, activity and communication.

Eliciting patient preferences is a central tenet of shared decision-making (SDM), which is now widely recognized as imperative in health care [5, 6]. SDM is particularly important in the context of diseases such as HPV-OPC in which patients have multiple complex treatment options, each with a meaningful impact on quality of life yet providing equivalent oncologic outcomes [7]. In head and neck cancer, patient-reported outcome measures (PROM) [8, 9] are commonly used in clinical trials. Although PROMs are valuable reflections of patient symptom burden and can permit comparisons of the impact of treatment on quality of life during and after therapy, they do not necessarily describe patient preferences. The only recent study to examine patient preference found that cure and survival were most highly valued as treatment goals, regardless of HPV tumor status [10]. However, whether patient preferences change after treatment has not been explored. In addition, understanding treatment-related concerns and whether they change during treatment can identify unmet needs and guide patient counselling.

Materials and Methods:

Patients with incident diagnoses of HPV-OPC, age 18 or older, who spoke English, were eligible to enroll in this prospective study at Johns Hopkins Hospital (Baltimore, Maryland). Patients completed a survey about priorities and concerns twice, at least 6 months apart. This included a baseline survey, taken within one year of diagnosis (“at diagnosis”) and a follow-up survey taken greater than 6 months after treatment end (“after treatment”). Tumor p16 immunohistochemistry status was abstracted from the medical record as a surrogate marker for HPV-positive tumor status. In situ hybridization (ISH) was performed for HPV16 E6/E7 RNA ISH (RNAscope®, Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Hayward, CA) on a subset of tumors. Cases that were HPV16 RNA ISH-negative underwent additional testing using a probe to detect E6/E7 RNA ISH for high-risk HPV genotypes [11]. This study was approved by the institutional review board, and all participants signed written informed consent.

Data collection

Two questionnaires were administered at each data collection timepoint (at diagnosis and after treatment). The “Chicago Priority Scale” [12] elicited the relative importance of 12 treatment goals on an ordinal ranking scale (1-12 with 1 as most important). Domains included: “keeping my natural voice”; “being able to chew normally”; “being cured of my cancer” (referred to hereafter as cure); “having no pain”; “keeping my appearance unchanged”; “returning to my regular activities as soon as possible” (activity); “having a normal amount of energy for me” (energy); “keeping my normal sense of taste and smell”; “being understood easily”; “living as long as possible” (survival); “having a comfortably moist mouth” (moist mouth); “being able to swallow all foods and liquids”. Cure and survival were designated oncologic goals, and all other domains were considered non-oncologic. The second survey, the “Concerns questionnaire” included 11 prompts relevant to treatment experience and elicited concern on a 3-point scale (not at all, somewhat, very much concerned). This questionnaire was adapted from data collection tools piloted in previously published studies [13, 14] and expanded on the basis of the authors’ clinical experience.

The baseline survey also included a quality of life assessment using the Functional Assessment for Cancer Treatment—General (FACT-G, Version 4, Copyright 1987, 1997), a 27-item questionnaire appraising functional, physical, emotional and social well-being validated for use in many settings [15]. The follow-up survey also included a validated assessment of patient regret regarding treatment decisions, known as the Ottawa Decision Regret scale (regret), which elicited agreement with 5 statements on a 5-point scale [16]. Surveys were administered via computer-assisted self-interview. The survey elements are available in Supplemental Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics including demographics (gender, race/ethnicity, income, education), substance use (tobacco, alcohol), and clinical details were collected at enrollment or abstracted from the medical record.

Data analysis

Analysis was restricted to enrolled patients who ranked at least 10 domains in the Chicago Priority Scale, and completed both surveys. Priorities were described as median rank (MR) and inter-quartile range (IQR), and compared across time of rank (at diagnosis versus [vs.] after treatment) by Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank tests. Concerns were analyzed as binary, with “very much” (high concern) compared with “somewhat” or “not at all.” Proportions of participants with high concern were compared across time of survey (at diagnosis vs. after treatment) by paired t-tests. Higher scores indicated better quality of life for the FACT-G (possible range 0-108) and greater regret for the Ottawa Decision Regret scale (possible range 0-100), and these scores along with decade of age were evaluated as continuous variables. Annual household income (<$50,000/$50,000-$150,000/≥$150,000), and education (less than advanced degree/advanced degree) were treated as categorical variables. The effect of patient characteristics on change in rank or high concern by time of survey was analyzed using linear regression. STATA version 15.1 (College Station, TX) was used for analysis.

Results

Of 50 unique participants diagnosed with incident HPV-OPC between August, 2016 and January, 2018 who completed baseline surveys, 37 (74%) completed follow up surveys and were included in the analytic population. Participants who did not complete the follow up survey (13, 26%) were similar in age (p=0.30) to the analytic population. Two (15%) of the 13 participants with incomplete follow up surveys died, and none recurred.

The majority of participants were 50-69 (22, 59%), male (33, 89%), white (33, 89%), reported former tobacco use (14, 50%) and current alcohol use (18, 67%) (Table 1). Most participants had an annual household income of $50,000 - 150,000 (14, 54%) and had an advanced degree (20, 71%). With regard to clinical characteristics, all 37 participants were p16 positive by immunohistochemistry. All 22 participants tested for high-risk HPV by ISH were positive, whereas 19 (86%) were HPV16 ISH-positive. Most participants were T1 or T2 AJCC 7th edition tumor stage (32, 86%), nodal stage N2 (31, 83%). The most common treatment regimen was chemoradiotherapy (16, 43%), followed by surgery with adjuvant chemoradiotherapy (10, 27%). Quality of life (median score 81, IQR 65-92) was moderately high for most patients. Regret was low, with median score 5, IQR 0-20. All participants except for one were “no evidence of disease” at time of follow up survey. One participant was receiving treatment for recurrence. A sensitivity analysis was performed excluding this participant, with similar results as described below.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated oropharyngeal cancer.

| N(%) | |

|---|---|

| Total number | 37 |

| Age | |

| 30-39 | 1 (3) |

| 40-49 | 7 (19) |

| 50-59 | 15 (41) |

| 60-69 | 7 (19) |

| ≥70 | 7 (19) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 4 (11) |

| Male | 33 (89) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White | 33 (89) |

| Black/Hispanic/Other | 4 (11) |

| Tobacco use | |

| Never | 12 (43) |

| Current | 2 (7) |

| Former | 14 (50) |

| Alcohol use | |

| Current | 18 (67) |

| Former | 9 (33) |

| Annual household income | |

| <$50,000 | 3 (12) |

| $50,000 - $150,000 | 14 (54) |

| ≥$150,000 | 9 (35) |

| Education | |

| Less than advanced degree | 8 (29) |

| Advanced degree | 20 (71) |

| HPV tumor status | |

| P16-positive | 37 (100) |

| HPV ISH-positive (among tested)a | 22 (100) |

| HPV16 ISH-positive (among tested) | 19 (86) |

| AJCC 7th Ed. tumor stage | |

| T1 | 19 (51) |

| T2 | 13 (35) |

| T3 | 2 (5) |

| T4 | 3 (8) |

| AJCC 7th Ed. nodal stage | |

| N0 | 1 (3) |

| N1 | 4 (11) |

| N2 | 31 (83) |

| N3 | 1 (3) |

| Treatment | |

| RT | 1 (3) |

| CRT | 16 (43) |

| Surgery | 1 (3) |

| Surgery + RT | 9 (24) |

| Surgery + CRT | 10 (27) |

| Median FACT-G score (IQR)b | 81 (65-92) |

| Median Regret score (IQR)c | 5 (0-20) |

IQR, interquartile range; HPV, human papillomavirus; ISH, in situ hybridization; RT, radiation therapy; CRT, chemoradiotherapy; FACT-G, Functional Assessment for Cancer Treatment – General

positive by RNA in situ hybridization for 18 high-risk HPV genotypes.

range, 0-108

range, 0-100

Participants completed baseline surveys a median of 1 month after diagnosis (IQR 1-2 months), and 8 months after the end of treatment (IQR 7-10 months). The median time between surveys was 10 months (IQR 9-11 months).

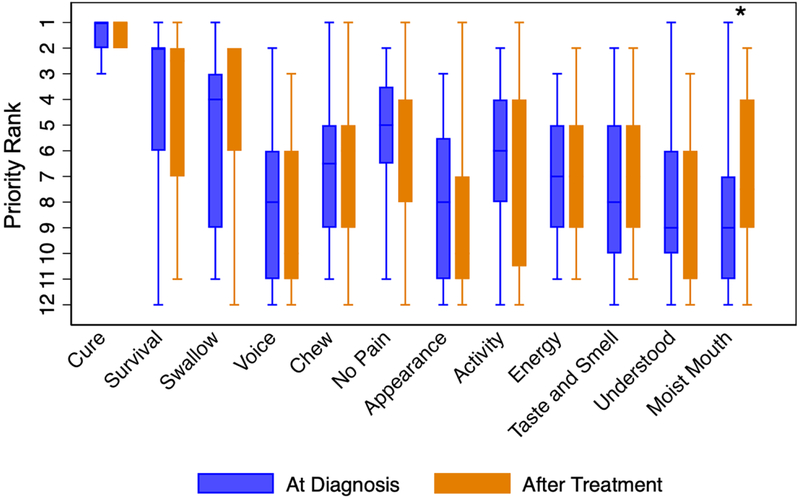

Priority rank after treatment compared with at diagnosis

At diagnosis, the treatment-related priorities ranked most highly by patients were cure (MR 1, IQR 1-2), followed by survival (MR 2, IQR 2-6), and swallow (MR 4, IQR 3-9). After treatment, these remained the top three priorities, with similar MR and IQR (Figure 1). Indeed, all priorities remained similar in importance after treatment compared with at diagnosis, with the exception of having a comfortably moist mouth, which became significantly more important (MR 9 vs. 7.5, p=0.01). While median rank for moist mouth was not within the top five priorities at either timepoint, there were six participants (17%) who ranked moist mouth in the top three priorities after undergoing treatment, compared to only one (3%) participant at diagnosis. The proportion of participants who ranked moist mouth in the bottom three priorities decreased from 15 (41%) at diagnosis to 8 (22%) after treatment.

Figure 1.

Ranked priorities at diagnosis and after treatment. Priority rank, with 1 as highest priority and 12 as lowest. Box plot shows the median rank and interquartile range, and whiskers extend the median by 1.5 times the interquartile range. *p=0.01.

Change in priority rank was then assessed by patient characteristics including age, income, education, quality of life, and regret. Change in priority rank was similar by each of these characteristics, with the exception that chew became more important after treatment compared to at diagnosis when examined by increasing decade of age (β=1.50, p=0.004). That is, for 19 participants 58 years of age or older, chew increased in importance from mean 6.5 to 5.4. Conversely, the prioritization of chew among 18 participants younger than 58 fell from 6.4 to 7.9.

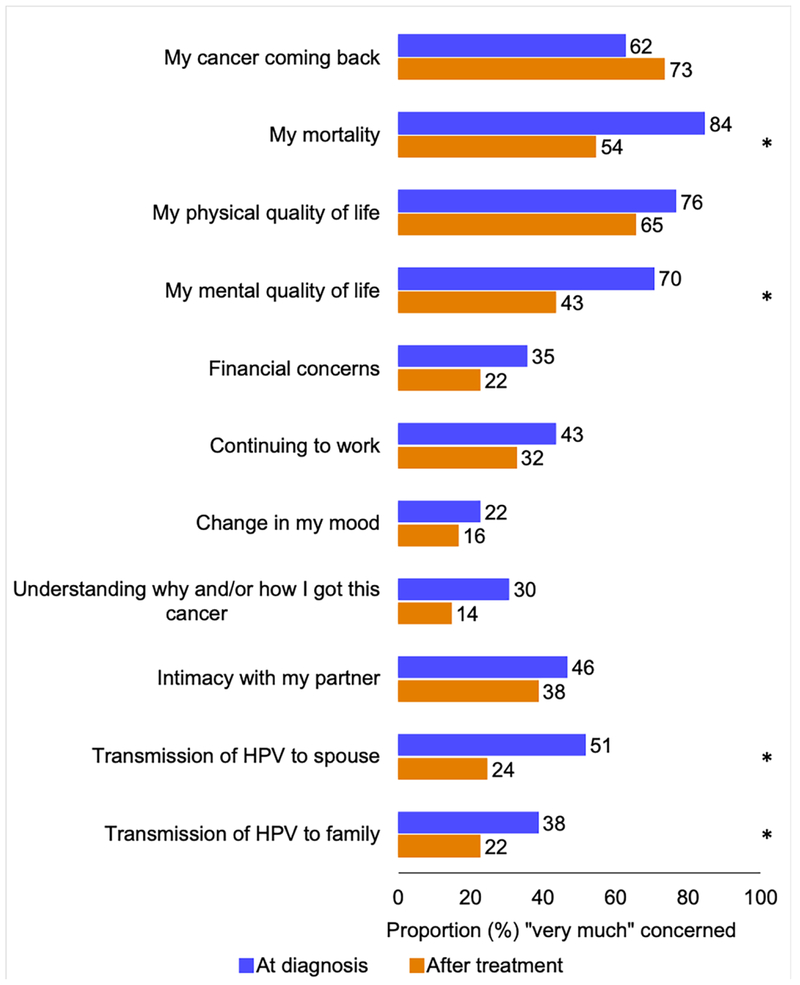

Change in concern after treatment compared with at diagnosis

Level of concern was also evaluated. At baseline, concern was most common regarding mortality (84%), physical quality of life (76%), mental quality of life (70%), and “my cancer coming back” (recurrence, 62%) (Figure 2). After treatment, these remained the most common topics of concern. Of the concerns assessed, the proportion of patients with high concern overall decreased after treatment compared with at diagnosis (p<0.001). These decreases in high concern were statistically significant for mortality (84% to 54%, p=0.006), mental quality of life (70% to 43%, p=0.006), and transmission of HPV to spouse (51% to 24%, p<0.001) and family (38% to 22%, p=0.03). Conversely, concern regarding recurrence trended upward after treatment compared with at diagnosis (62% to 73%, p=0.25).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of high concern (on a three point scale) among patients with human papillomavirus-associated oropharyngeal cancer regarding treatment-related issues at diagnosis and after treatment. *p=0.0008-0.04

Change in concern was also evaluated by age. Prevalence of high concern was similar by age at both time points, however the decrease in concern was significantly greater by increasing decade of age (β=−1.35, p=0.03). Interestingly, those that had an increase in overall concern had a median age of 48 (n=5), whereas those that had a decrease in concern had a median age of 59 (n=28, p=0.03). Examining issues separately, this pattern was significant for concern regarding transmission of HPV to family, which decreased with increasing age (β=−0.24, p=0.04).

Concern regarding “mental quality of life” increased by a greater magnitude by increasing quality of life score (β=0.02, p=0.02). Change in specific concerns was otherwise generally similar by participant age, income, education, quality of life, and regret.

Discussion

This is one of the first studies to describe the trajectory of treatment-related priorities and concerns of patients with HPV-OPC. We found that patient priorities largely remain unchanged after treatment. These findings can be used to clarify patient treatment goals and needs, an understanding of which is valuable in the context of the rising incidence of HPV-OPC and the proposed changes in treatment currently under investigation. Apart from oncologic outcomes and moist mouth, the wide variability in priority rank reflects the unique value structure of individual patients, which cautions against presuming homogeneity and reinforces the importance of eliciting patient preference while discussing treatment options. A general decrease in prevalence of treatment-related concerns is encouraging, whereas the persistence of some areas of concern may inform patient counseling.

Treatment deintensification aims to treat low-risk groups with less intense curative therapy in order to decrease toxicity while maintaining excellent oncologic outcomes. Our finding that cure and survival are paramount to patients at diagnosis is consistent with prior studies [17, 18]. Patients’ desire for cure and survival at diagnosis is consistent with the previously described high diagnosis-related anxiety of this patient population [13]. It was previously unknown whether patients would view cure and survival as less important than other domains after treatment. However, this study suggests cure and survival remain top priorities after the acute toxicity of treatment is experienced. Had other domains risen in importance above oncologic outcomes after treatment, it would imply that, cognizant of their excellent prognosis and having finished therapy, this population might prefer to have avoided toxicity. Theoretically, this would lend support to deintensifying therapy so as to preserve swallow and taste, for example, for the next decades of life. However, the fact that oncologic outcomes were still unequivocally the most important priorities after treatment implies that these patients feel that the preservation of domains affected by therapy are secondary to oncologic goals. This finding supports conservative deintensification for HPV-OPC with the primary goal of maintaining survival outcomes, respecting patient preference for cure above all.

Though most domains did not significantly shift after treatment, having a comfortably moist mouth became significantly more important, which may imply that that the negative impact of xerostomia was unanticipated by patients and/or by the counselling multidisciplinary team. An earlier study based on the Chicago Priority Scale demonstrated that providers ranked moist mouth as lower in importance than patients [18], implying that providers may underestimate the impact of xerostomia. Xerostomia affects around two-thirds of oropharyngeal cancer survivors short-term [19], and remains a significant toxicity with deintensified doses of intensity-modulated radiotherapy [20]. Moreover, 39% of long-term survivors report moderate/severe xerostomia, which does not improve with time from treatment end [21]. Xerostomia predisposes patients to dental decay, affects social functioning due to halitosis and difficulty eating [22], and correlates with lower quality of life [23] and poor nutritional status [24]. Our results reinforce the importance of emphasizing that xerostomia is a potential side effect of radiation therapy during patient counseling at diagnosis and providing support throughout treatment. Although available treatments have limited efficacy, patients may be offered sialogogues or rinses as part of survivorship care. In addition, efforts to spare salivary glands when planning radiation treatment [24, 25] and continued investigation of new treatments for xerostomia are paramount [26].

Recent data have shown that the mean age of incident HPV-OPC cases is rising [27, 28]. Due to this and the attenuation of survival benefit conferred by HPV tumor status in older adults, treatment preference by age requires special attention [28]. Age did not appear to affect changes in oncologic priority rank, implying that the desire for curative therapy did not dissipate in the face of the experience of treatment for older adults. Chew rose in importance by older age, however, indicating that older adults had a more difficult time with the changes to the mechanics of eating. Younger patients tended to retain or increase their concern during treatment, in comparison to the decrease in concern among older participants. Although the reasons for this are unclear, prior study has demonstrated that anxiety and distress associated with cancer diagnosis are higher among younger patients [29].

Concern regarding treatment-related issues tended to decrease after therapy compared with at diagnosis. This is an encouraging finding, and may reflect that some patients overcame the challenges of treatment. Despite the overall decrease in concern, prevalence of posttreatment worry regarding HPV transmission to spouse (20%) and family (22%), intimacy with a partner (38%) and “why I got this cancer” (14%) highlights that, similar to a prior study [30], some patients may have unaddressed questions or misinformation regarding HPV transmission. The high prevalence (>60%) and small posttreatment rise in concern regarding recurrence identifies an additional supportive need. This finding is consistent with literature describing fear of recurrence among head and neck cancer survivors as common [31]. This is not unprecedented, as one in four HPV-OPC patients will recur within three years [32]. As head and neck cancer patients are reluctant to discuss fear of recurrence with providers [33], yet derive benefit from discussing their fear during follow-up [34], the prevalence of this concern in our study supports provider-initiated open discussion of coping mechanisms during surveillance visits.

This study had several limitations. This analysis is limited by a small sample size, and we acknowledge that additional differences may have been detected with a larger dataset. Furthermore, although most patients filled out surveys close in proximity to their diagnosis, the range of data collection “at diagnosis” was up to one year, and later responses may not reflect pretreatment goals. Further, this study was limited to subjects who completed both baseline and follow-up surveys and we can not exclude the possibility that patients with poorest outcomes (who are less likely to have been able to complete a follow-up survey) may have different preferences.

In conclusion, treatment-related priorities generally do not change during treatment for HPV-OPC cancer. The stability of relative valuations of oncologic versus non-oncologic priorities supports the conservative adoption of deintensified treatement regimens. The unique emergence of having a comfortably moist mouth highlights the importance of patient counselling and the continued investigation of strategies to prevent and treat xerostomia. Lastly, concerns tended to decrease after treatment, although the persistence of some concerns provides opportunities for patient education and support.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS:

Treatment-related priorities of HPV-OPC are similar through treatment.

The importance of having a moist mouth increases after treatment.

Concern regarding treatment-relates issues generally declines after treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

The authors would like to thank the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (grants P50 DE019032, R35DE026631), the National Institutes of Health (grant 5T32DC000027-29) and the Oral Cancer Foundation for their support of this work.

FUNDING: This work was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (grants P50 DE019032, R35DE026631), the National Institutes of Health (grant 5T32DC000027-29) and the Oral Cancer Foundation.

FUNDING ROLE: The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Lortet-Tieulent J, Paula Curado M, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, et al. Worldwide trends in incidence rates for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:4550–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Fakhry C, Westra WH, Li S, Cmelak A, Ridge JA, Pinto H, et al. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008;100:261–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, Weber R, Rosenthal DI, Nguyen-Tân F, et al. Human Papillomavirus and Survival of Patients with Oropharyngeal Cancer — NEJM. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363:24–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].O'Sullivan B, Huang SH, Siu LL, Waldron J, Zhao H, Perez-Ordonez B, et al. Deintensification candidate subgroups in human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal cancer according to minimal risk of distant metastasis. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:543–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zdenkowski N, Butow P, Tesson S, Boyle F. A systematic review of decision aids for patients making a decision about treatment for early breast cancer. Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2016;26:31–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Coylewright M, Montori V, Ting HH. Patient-centered shared decision-making: a public imperative. Am J Med. 2012;125:545–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pollard S, Bansback N, Bryan S. Physician attitudes toward shared decision making: A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:1046–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Duman-Lubberding S, van Uden-Kraan CF, Jansen F, Witte BI, Eerenstein SEJ, van Weert S, et al. Durable usage of patient-reported outcome measures in clinical practice to monitor health-related quality of life in head and neck cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:3775–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Boyes H, Barraclough J, Ratansi R, Rogers SN, Kanatas A. Structured review of the patient-reported outcome instruments used in clinical trials in head and neck surgery. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;56:161–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Windon MJ, D’Souza G, Faraji F, Troy T, Koch WM, Gourin CG, et al. Priorities, Concerns, and Regret Among Patients With Head and Neck Cancer. Cancer. 2018;125(8):1281–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bishop Ja, Ma X-J, Wang H, Luo Y, Illei PB, Begum S, et al. Detection of Transcriptionally Active High-risk HPV in Patients With Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma as Visualized by a Novel E6/E7 mRNA In Situ Hybridization Method. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2012;36:1874–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].List MA, Stracks J, Colangelo L, Butler P, Ganzenko N, Lundy D, et al. How Do Head and Neck Cancer Patients Prioritize Treatment Outcomes Before Initiating Treatment? J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:877–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].D'Souza G, Zhang Y, Merritt S, Gold D, Robbins HA, Buckman V, et al. Patient experience and anxiety during and after treatment for an HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncology. 2016;60:90–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Taberna M, Inglehart RC, Pickard RKL, Fakhry C, Agrawal A, Katz ML, et al. Significant changes in sexual behavior after a diagnosis of human papillomavirus-positive and human papillomavirus-negative oral cancer. Cancer. 2017;123:1156–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, et al. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: Development and validation of the general measure. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1993;11:570–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Brehaut JC, O'Connor AM, Wood TJ, Hack TF, Siminoff L, Gordon E, et al. Validation of a decision regret scale. Medical Decision Making. 2003;23:281–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].List MA, Rutherford JL, Stracks J, Pauloski BR, Logemann JA, Lundy D, et al. Prioritizing treatment outcomes: Head and neck cancer patients versus nonpatients. Head and Neck. 2004;26:163–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gill SS, Frew J, Fry A, Adam J, Paleri V, Dobrowsky W, et al. priorities for the head and neck cancer patient, their companion and members of the multidisciplinary team and decision regret. Clinical Oncology. 2011;23:518–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chera BS, Fried D, Price A, Amdur RJ, Mendenhall W, Lu C, et al. Dosimetric Predictors of Patient-Reported Xerostomia and Dysphagia With Deintensified Chemoradiation Therapy for HPV-Associated Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;98:1022–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Pearlstein KA, Wang K, Amdur RJ, Shen CJ, Dagan R, Weiss J, et al. Quality of Life for Patients with Favorable Risk HPV-Associated Oropharyngeal Cancer After De-Intensified Chemoradiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Head MDA, Neck Cancer Symptom Working G. Self-reported oral morbidities in long-term oropharyngeal cancer survivors: A cross-sectional survey of 906 survivors. Oral Oncol. 2018;84:88–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Charalambous A Hermeneutic phenomenological interpretations of patients with head and neck neoplasm experiences living with radiation-induced xerostomia: The price to pay? European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2014;18:512–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Head MDA, Neck Cancer Symptom Working G, Kamal M, Rosenthal DI, Volpe S, Goepfert RP, et al. Patient reported dry mouth: Instrument comparison and model performance for correlation with quality of life in head and neck cancer survivors. Radiother Oncol. 2018;126:75–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Nutting CM, Morden JP, Harrington KJ, Urbano TG, Bhide SA, Clark C, et al. Parotid-sparing intensity modulated versus conventional radiotherapy in head and neck cancer (PARSPORT): A phase 3 multicentre randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2011;12:127–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hawkins PG, Kadam AS, Jackson WC, Eisbruch A. Organ-Sparing in Radiotherapy for Head-and-Neck Cancer: Improving Quality of Life. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2018;28:46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Buglione M, Cavagnini R, Di Rosario F, Maddalo M, Vassalli L, Grisanti S, et al. Oral toxicity management in head and neck cancer patients treated with chemotherapy and radiation: Xerostomia and trismus (Part 2). Literature review and consensus statement. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;102:47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Windon MJ, D'Souza G, Rettig E, Westra WH, van Zante A, Wang S, et al. Increasing Prevalence of Human Papillomavirus Among Older Adults. Cancer. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Rettig EM, Zaidi M, Faraji F, Eisele DW, El Asmar M, Fung N, et al. Oropharyngeal cancer is no longer a disease of younger patients and the prognostic advantage of Human Papillomavirus is attenuated among older patients: Analysis of the National Cancer Database. Oral Oncology. 2018;83:147–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Linden W, Vodermaier A, MacKenzie R, Greig D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: Prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;141:343–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Inglehart RC, Taberna M, Pickard RKL, Hoff M, Fakhry C, Ozer E, et al. HPV knowledge gaps and information seeking by oral cancer patients. Oral Oncology. 2016;63:23–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kanatas A, Humphris G, Lowe D, Rogers SN. Further analysis of the emotional consequences of head and neck cancer as reflected by the Patients' Concerns Inventory. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;53:711–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Fakhry C, Zhang Q, Nguyen-Tan PF, Rosenthal D, El-Naggar A, Garden AS, et al. Human papillomavirus and overall survival after progression of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32:3365–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Humphris GM, Ozakinci G. Psychological responses and support needs of patients following head and neck cancer. Int J Surg. 2006;4:37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ozakinci G, Swash B, Humphris G, Rogers SN, Hulbert-Williams NJ. Fear of cancer recurrence in oral and oropharyngeal cancer patients: An investigation of the clinical encounter. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2018;27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.