Abstract

Porous composite hydrogels were prepared using glycol chitosan as the matrix, glyoxal as the chemical crosslinker, and carbon nanotubes (CNTs) as the fibers. Both carboxylic and hydroxylic functionalized CNTs were used. The homogeneity of CNTs dispersion was evaluated using scanning electron microscopy. Human vocal fold fibroblasts were cultured and encapsulated in the composite hydrogels with different CNT concentrations to quantify cell viability. Rheological tests were performed to determine the gelation time and the storage modulus as a function of CNT concentration. The gelation time tended to decrease for low concentrations and increase at higher concentrations, reaching a local minimum value. The storage modulus obeyed different trends depending on the functional group. The porosity of the hydrogels was found to increase by 120% when higher concentrations of carboxylic CNTs were used. A high porosity may promote cell adhesion, migration, and recruitment from the surrounding native tissue, which will be investigated in future work aiming at applying this injectable biomaterial for vocal fold tissue regeneration.

Keywords: Carbon nanotubes, Vocal folds, Injectable hydrogel, Tissue engineering

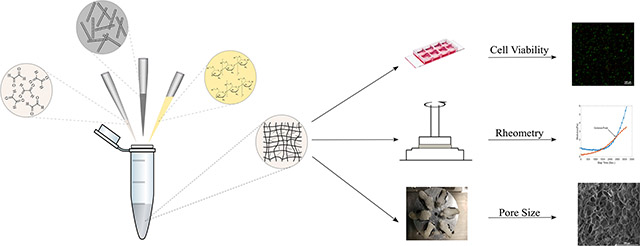

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The human voice is generated by forcing air out of the lungs through the larynx and the articulators. The vocal folds (VFs) are the organs responsible for producing voice by periodically valving the expelled air [1]. Mature human VFs are comprised of three layers: 1) the epithelium cover; 2) the lamina propria (LP); and 3) the vocalis muscle [2, 3]. Most VF injuries and structural disorders are related to the LP, which is a mucosal tissue broadly consisting of superficial, intermediate, and deep layers [4, 5]. Hyaluronic acid (HA) and fibrous proteins, which are secreted by fibroblast cells, are the main constituents of the LP [6-8]. Although the boundaries between different layers of the LP are not always very distinct, the volume fraction of collagen and elastin fibers tends to vary across the LP layers [7, 8]. The texture of the various layers in LP is also different. The superficial and intermediate layers are mostly extracellular, while the deep layer is mostly made of cellular tissue [9].

Voice overuse or abuse may cause tissue inflammation and wounds in the VFs. Generally, women are more susceptible to voice disorders due to differences in laryngeal anatomy [10]. Based on the origin and severity of symptoms, different tissue engineering methods have been used for the treatment of voice disorders [11]. When the injury is severe, structural implants are employed for VF treatment. In the case of minor damage, injectable materials are used as synthetic extracellular matrix (ECM) [12]. Polytef paste (Teflon™), Gelfoam™, collagen, HA, calcium hydroxylapatite (CaHA), and autologous fat are popular injectable materials used clinically. However, many of these injectables have drawbacks, including the risk of foreign body reaction (granuloma), chronic inflammation, over-stiffening, high degradation rate, and low gelation time [12-18]. Another common problem with current injectable scaffolds is limited cell adhesion and migration due to the lack of focal adhesion sites [19]. Low cell migration rate results in slow and incomplete tissue reconstruction, which further decelerates the wound healing process. To overcome this problem, composite hydrogels with imbedded micro-particles were proposed by Heris et. al to activate mechanotaxis processes in the scaffolds [20]. In the same vein, the present study examines the use of CNT-based composite hydrogels as injectable scaffolds for vocal folds tissue regeneration.

Carbon nanotubes have unique properties, including a high porosity [21, 22], good functionalization [23], and biomechanical properties [24]. They can thus be imbedded within a hydrogel to mimic the structure of fibrous proteins in the ECM. Previously studies have used CNTs’ in hydrogels to enhance the stiffness of the bulk gel [25, 26]. They have been extensively studied for different applications in the human body, such as skin growth, osteoblastic cell differentiation and proliferation, and brain circuit stimulation [24]. However, CNTs have never so far been incorporated in hydrogels for promoting cell migration. To assess the feasibility of using CNT-based composite scaffolds as synthetic ECM, their biological, mechanical, and physical properties need to be investigated.

Much work has been done on the interactions between CNTs and various cell types, from neurons to osteoblast and stem cells [24, 27, 28]. The reported range of CNT concentration without significant cytotoxicity varies considerably, between only a few nanograms per ml [29] to several mg per ml [30]. These results indicate that CNTs’ cytotoxicity varies with different cell types [31], thereby necessitating further studies specific to human vocal fold fibroblasts (HVFFs. While the biocompatibility of CNTs is still a subject of research, it is generally accepted that functionalized CNTs are more biocompatible than pristine CNTs [32-37].

In terms of mechanical properties, CNTs constitute the stiffest nanomaterials available, with a Young’s modulus up to 1.8 TPa [38]. The incorporation of CNTs in hydrogels may change the bulk stiffness of the scaffolds [39, 40]. Since cells tend to adhere to stiff surfaces [41], CNT-based composite hydrogels are hypothesized to offer a better substrate for HVFFs, in comparison with a homogeneous soft matrix. A biomimetic material should maintain the vibratory response of the native VF, which is a function of stiffness. The elastic shear modulus of mature human vocal fold at 1 Hz is around 10~300 Pa [42]; it varies due to gender- and age-related differences in human vocal folds [43, 44]. It is therefore desirable for injectable biomaterials to have tunable mechanical properties. It was hypothesized that this could be achieved simply by varying the CNT concentration until the modulus of the gel matches that of the local native tissue. This implies that the functionality of the composite hydrogel is not necessarily proportional to the concentration of CNT added.

Hydrogels are a class of crosslinked polymer chains with varying degrees of porosity. In order to recruit HVFFs, the pore size of hydrogel network should be similar to that of the cells (approximately 25 ± 5 μm in the case of HVFFs). The pore size changes when nanoparticles are introduced in the hydrogel network [45, 46]. Other hydrogel characteristics such as the gelation time, the swelling ratio, and the swelling rate are also likely affected by nanoparticles [46, 47]. Since the hydrogel precursors are mixed before injection, a rapid gelation may leave insufficient time for injection of the hydrogel in the VFs. A short gelation time can hamper hydrogel flow into the tissue [48]. A long gelation time, on the other hand, may result in instability of the hydrogel in the LP, and cause the biomaterial to be washed off [49]. Consequently, it is desirable for the gelation time to be within a time period of around 20 minutes. Because the vocal folds are located within the airway, it is also important to control swelling to avoid chronic respiratory problems after injection [50].

In the present study, different groups of injectable CNT-based composite hydrogels were prepared using glycol chitosan/glyoxal as the matrix. The effects of CNT concentration and functional groups on the viability rate of HVFFs was investigated. The maximum allowable CNT concentration based on a 70% viability rate was established. The mechanical properties and the gelation time of the materials were evaluated via rheometry tests. Swelling assays were conducted to evaluate water absorption capacity. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to quantify the change in pore size resulting from the addition of CNT’s to the hydrogels. The results support the plausibility of using CNT-based composite hydrogels as a synthetic scaffold in human VFs.

2. Experimental Methods and Procedures

2.1. Composite hydrogel synthesis

Carboxylic and hydroxylic multi-walled functionalized CNTs (>95%, OD:50-80 nm) were provided by US Research Nanomaterials, Inc. (Houston, TX, USA). To prevent agglomeration, the CNTs were dispersed in water before incorporation into the matrix. The use of surfactants to facilitate CNT dispersion was avoided to minimize adverse impact on cells viability. A probe sonicator (Fisher Scientific, Sonic Dismembrator Model 100) was utilized to homogeneously disperse the functionalized CNTs. The probe sonicator delivered 12 – 15 Watts of acoustic power and was found to be more effective than a bath sonicator. A stock solution of CNTs in water was prepared and sonicated. The resulting suspension was then centrifuged for 5 min at 2500 rpm to deposit the undispersed agglomerates at the bottom of the test tube. The sonication-centrifuging process was repeated twice, followed by a scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of the sample, to ensure that the CNTs are dispersed well. The homogeneous suspension, which is stable for several weeks, was subsequently diluted to obtain the final desired concentration. The concentrations were measured gravimetrically.

Glycol chitosan powder with a degree of polymerization of 2000 and glyoxal with a 40% volume fraction were purchased from Chemos and Sigma Aldrich Corporate, respectively. A concentration of 5% glycol chitosan solution was prepared Pbs 1x (Wisent Inc.) as the solvent, mixing using a Fisher Scientific rotator for 24 hours. Carbon nanotube-glycol chitosan (CNT-GC) composite hydrogels were prepared using 2% glycol chitosan solution as the matrix, different concentrations of CNT and 0.005% glyoxal as the crosslinker. For biological tests, two million cells/ml HVFFs were encapsulated into the hydrogel immediately before adding crosslinker. All composite hydrogel constituents were autoclaved. All preparations were done under a cell culture hood in sterilized conditions to minimize the risks of contamination.

2.2. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The length, diameter, and wall structure of the CNTs were visualized by means of TEM images. A drop of 2 mg/ml CNT suspension was imaged using a Philips CM200 TEM equipped with an AMT XR40B CCD camera and EDAX Genesis EDS. The images were collected with an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. The length and diameter measurements were performed using the ImageJ software (National Institute of Health).

2.3. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Scanning electron microscopy images were used to measure the pore size of CNT-GC network. The composite hydrogels were prepared as mentioned in section 2.1. After curing, the samples were frozen for 24 hours. The frozen samples were lyophilized in a ModulyoD 5L freeze dryer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) under 290 ± 10 μbar at room temperature for 24 hours. A FEI F50 scanning electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was then employed to image the surface network of the hydrogels. The ImageJ software was used for analyzing the SEM images. The average pore size was determined for each study group.

2.4. Swelling

To quantify water absorption, triplicate samples of CNT-GC were prepared in Eppendorf vials and cured in a 37°C incubator for 4 hours, as previously mentioned in section 2.1. After curing, the samples’ initial weight (Wi) were measured using a high-precision balance (Quintix, Sartorius, precision= 1mg). A solution of PBS 1x was then added to the hydrogels, and the samples underwent agitation via an orbital shaker (VWR 3500, Radnor, PA, United States) at 75rpm. On days 0, 1, 3, 7, 14, 30 the PBS was removed, and the samples’ weight was measured and recorded as the swollen weight (Ws). The swelling ratio was calculated based on the sample weight increase percentage at the above time points ((Ws – Wi)/Wi × 100%). The samples were then frozen in the −80°C freezer to be used for physical characterization.

2.5. Rheometry

A single head rotational rheometer (Discovery Hybrid HR-2, TA Instrument, DE) equipped with a 20 mm parallel plate was employed to determine the rheological properties for hydrogels with different CNT concentrations. Shear strain values below 5% were used to remain in the elastic region. Selected based on viability results, CNT concentrations of 250, 500 and 750 μg/ml along with a CNT-free control were used for rheological characterization. Rheological tests were performed at least in triplicates.

2.5.1. Gelation Time

Time-sweep experiments were conducted with a rotational frequency of 1 Hz and a shear strain of 0.1% at the body temperature, 37°C. Using the Trios software (TA Instrument, DE), the gap size between the rheometer plates was adjusted to 1000 μm to provide a reproducible loading. Each sample was prepared in an Eppendorf vial and injected to completely fill the gap. Time-sweep tests were performed immediately after injection over a period of one hour, spanning the entire curing period. A solvent trap (TA Instrument, DE) was used in order to avoid sample dehydration during tests. The storage and loss moduli (G′ and G″, respectively) were recorded during the curing period to determine the gelation time.

Two methods are commonly used to measure the gelation time of hydrogels. In the first method, the gelation point is defined as the instant when the ratio between G′ and G″ becomes independent of frequency. The other method is based on the intersection of G′ and G″ curves in a time-sweep test, indicating a transition between liquid and solid phases. The second method was used here.

2.5.2. Mechanical Characterization

After the time sweep tests, the sample was left under a solvent trap for 14 hours to ensure complete curing. Frequency-sweep (0.01 to 10 Hz) tests were then performed with a 0.1% of shear strain at 37°C. The viscoelastic properties, such as the storage modulus, the loss modulus, and the complex viscosity (η) were measured and compared with those of the native LP.

2.6. Cell culture

Cells (HVFFs) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM- Wisent Inc.) which contains 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich Corporate), 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich Corporate), and 1% non-essential amino acids (Sigma-Aldrich Corporate) at 37°C, in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. The cells were cultured in treated T75 flasks with filter caps (Thermo Scientific). Cell culture media were replaced every two days. When the desired level of confluency was reached, the flask was washed by Pbs 1x, and the adherent cells were detached from the flask surface using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA solution (Sigma-Aldrich Corporate) and encapsulated in the composite hydrogel to be cultured in a three-dimensional network.

2.7. Biocompatibility (Cell viability)

As a preliminary study, small quantities of CNT powder were added to the cell culture media. The cells were observed under a brightfield microscope (Olympus CKX41) every day for two weeks. Since no differences were observed in terms of cells growth, a set of experiments was designed to quantify the biocompatibility of CNTs in contact with HVFFs. To this end, samples with 250 ml of hydrogels with different CNT concentrations were prepared in 8 well μ-slides (Ibidi, Martinsried, Germany) using the method described in section 2.1. An estimated 2 million cells per ml of HVFFs were homogenously capsulated in the hydrogels. The samples were cured at 37° in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator for one hour. Cell culture media was subsequently added on the samples. The media was changed every two days.

The HVFF’s viability rate was measured for each sample on days 0, 4 and 7. Due to the very diverse and even conflicting reports on maximum allowable CNT doses in contact with cells, biocompatibility tests were initiated with a very low CNT concentration. To identify the maximum possible concentration without significant cytotoxicity, solutions with low (10, 20, 40, 80 μg/ml), medium (250, 500, 750 μg/ml) and high (2000, 4000, 8000 μg/ml) CNT concentrations were used. In each set experiments, a CNT-free hydrogel was used as the negative control. Measurements were done in triplicate.

The cells were stained using a live/dead™ Viability/Cytotoxicity kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States) prior to imaging. Green and red fluorescent lights were used in confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) to image live and dead cells, respectively. The Z-stack feature of the Zeiss LSM710 CLSM was used for image acquisition using the Zen software (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). The images were reconstructed and analyzed using the image processing software Imaris 8.3.1 (Bitplane, Switzerland) (See the supplementary file). The viability rate was determined based on reconstructed images by calculating the ratio between the number of live cells and the total number of cells for all the samples on days 0, 4, and 7.

2.8. PH measurement

The pH values of CNT solutions and hydrogels were measured using an electronic SevenEasy pH meter (Mettler Toledo). The measurements were performed at room temperature.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

The quantitative results were reported in mean values ± standard deviations (n=3 or greater). Two-tailed paired and unpaired student’s T-test were used accordingly to determine the P-values for different sets of data. A P-value under 0.05 was considered as the threshold to distinguish between significantly different data sets.

3. Results

3.1. CNT characterization

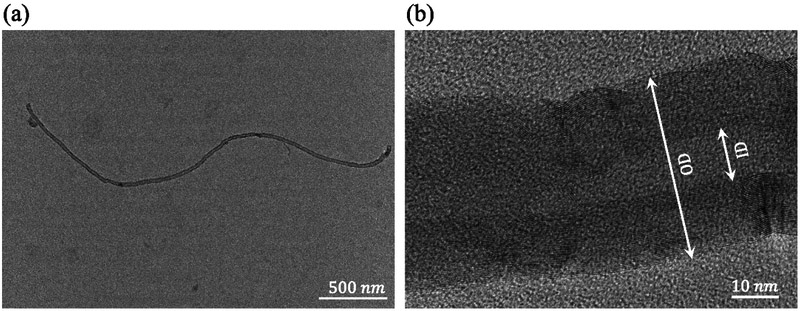

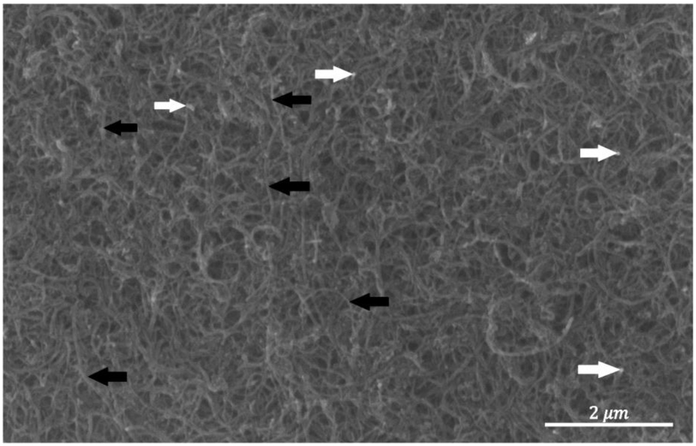

Transmission electron microscopy images in Figure 1 show that the actual diameter of carboxylic CNTs following 20 minutes of sonication is 45 ± 5 nm, which is roughly 30% less than the nominal diameter reported by the CNT provider. Excessive sonication power/time may cause breakage and shortening of the nanotubes as well as unzipping of the nanotubes’ exterior walls. To visually determine the extent of these defects, SEM images were used. Damaged CNTs are indicated by arrows in Figure 2. The majority of the CNTs are intact. Insufficient energy may imperfectly debond the agglomerations. After a few iterations, the proper sonicator output power and sonication time was determined so that minimum damage to the nanotubes was introduced while the CNTs were being dispersed. For carboxylic and hydroxylic CNTs, the optimum duration of sonication with an acoustic power of 12 – 15 Watts was found to be 12 – 18 minutes and 15 – 23 minutes, respectively. The COOH-CNTs were more dispersible in water.

Figure 1.

TEM images of carboxylic MWCNT used to estimate the (a) length and the (b) diameter of CNTs. Since at least one dimension is on the order of one nm, CNT-based composite hydrogels are considered nanocomposites.

Figure 2.

SEM images of a well-dispersed lot of carboxylic CNT suspension. The bright points indicated with the white arrows are CNTs’ breakage points. The black arrows point to the long intact CNTs without visible damage.

3.2. Physical characterization

3.2.1. Swelling behavior

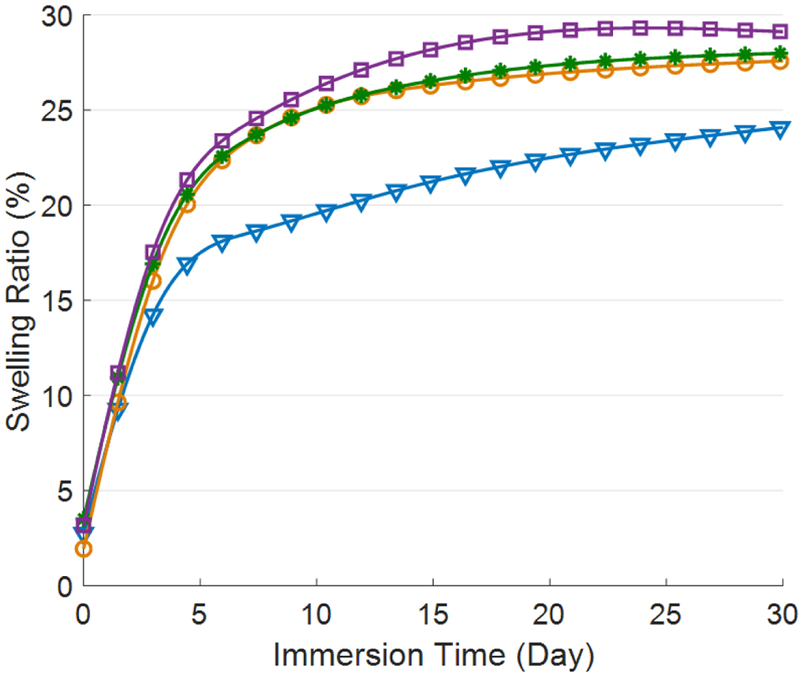

Figure 3 shows the effect of COOH-CNT concentration on the composite hydrogel swelling ratio over a period of one month. On day 30, the swelling ratio for samples with CNT concentrations of 0,250,500 and 750 μg/ml were 24%, 27.5%, 28%, and 29%, respectively. This shows that water permeability increased by 5% in the first month following the addition of COOH-CNTs. The samples with COOH-CNT reached their maximum swelling ratio more rapidly than the control sample, which shows that CNT-based hydrogels may stabilize faster in the body. The addition of OH-CNT did not visibly affect the swelling behavior of the hydrogels. The swelling ratio for all the samples, including the control sample, was measured to be 4% after 30 days. The overall swelling ratio of carboxylic hydrogels was greater than that of the hydroxylic hydrogels, due to the different crosslinker concentrations. Increasing the crosslinker concentration impeded hydrogel swelling. Moreover, the addition of OH-CNT did not affect the swelling ratio. All hydroxylic samples reached their maximum swelling ratio within the first week.

Figure 3.

Changes in swelling ratio for different COOH-CNT groups during the first month of immersion in PBS-1x (Downward-pointing triangle: Control, Circle: CNT250, Asterisk: CNT500, Square: CNT750).

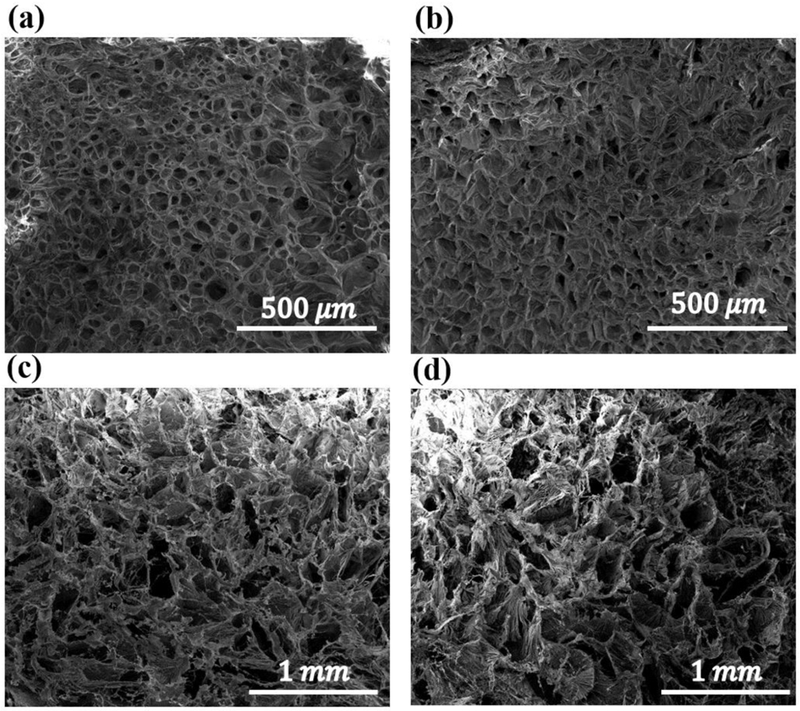

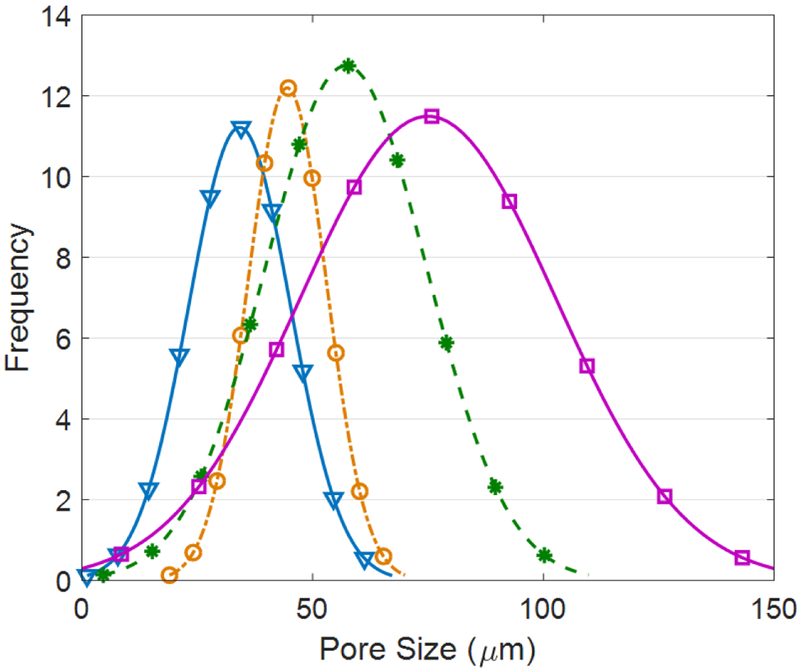

3.2.2. Pore size

Figure 4 shows snapshots of SEM images taken from the hydrogels network. The samples’ porosity was determined based on the SEM images using the ImageJ software. Figure 5 depicts the distribution of the measured pore size in each sample. The average pore size of the hydrogels with 250,500,750 μg/ml of COOH-CNT was increased by 33%, 73%, and 120%, respectively based on the control sample. The addition of OH-CNTs did not cause any enlargement in pore size.

Figure 4.

SEM images taken from the hydrogel surfaces to measure the average pore size for different COOH-CNT concentrations; (a) Control, (b) CNT250, (c) CNT500, (d) CNT750.

Figure 5.

The measured pore size distribution for the carboxylic CNT composite hydrogels (Downward-pointing triangle: Control, Circle: CNT250, Asterisk: CNT500, Square: CNT750).

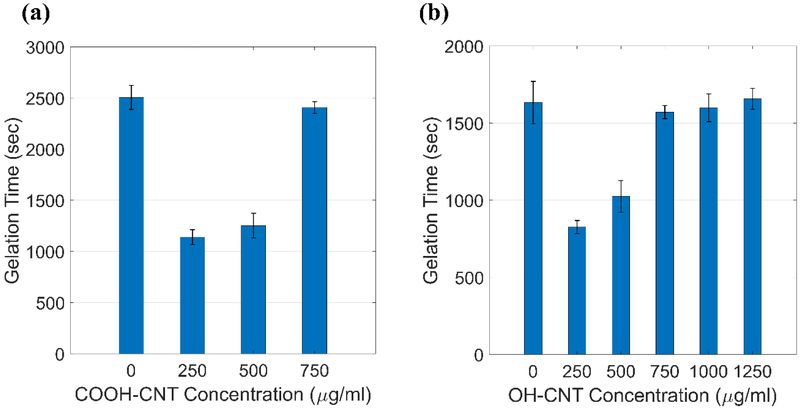

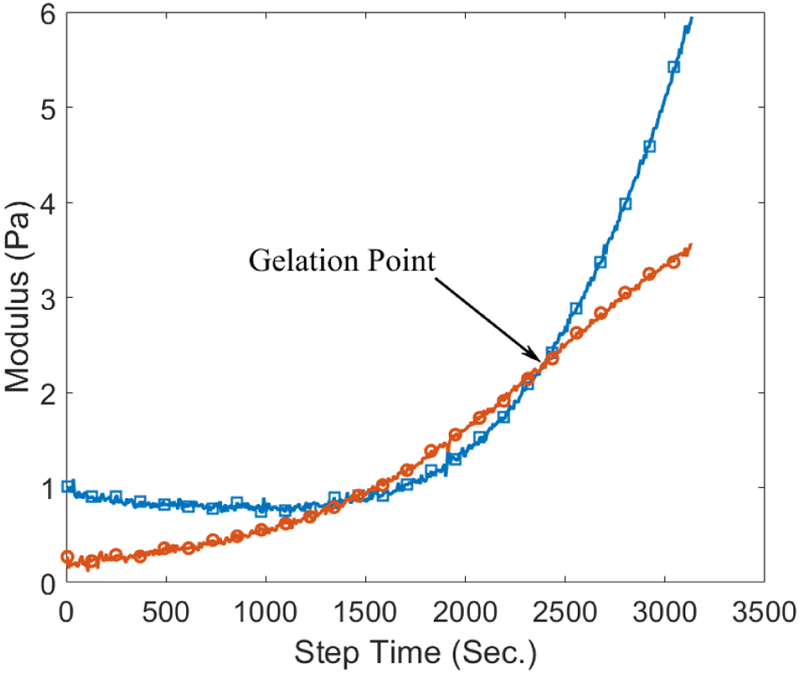

3.3. Rheological characterization

Rheological characterization was to investigate the viscoelastic properties of the hydrogels, which are important for vocal folds injectables. Both the storage and shear moduli increased while the hydrogel was being cured during the time-sweep rheometry tests, as shown in Figure 6. The gelation time was measured for different samples. In Figure 7-a it is demonstrated that the addition of CNTs up to a concentration of 250 μg/ml caused a decrease in the gelation time. Increased CNT concentrations tended to postpone gelation. In the case of OH-CNT hydrogels, increasing the CNT concentration to values greater than 750 μg/ml, which is still in the biocompatible range, did not highly affect the gelation time (Figure 7-b).

Figure 6.

Gelation point for the control sample in time-sweep rheometry results (Circle: Loss modulus, Square: Storage Modulus).

Figure 7.

Gelation time for the composite hydrogels as a function of CNT concentration; (a) Carboxylic CNT groups (b) Hydroxylic CNT groups.

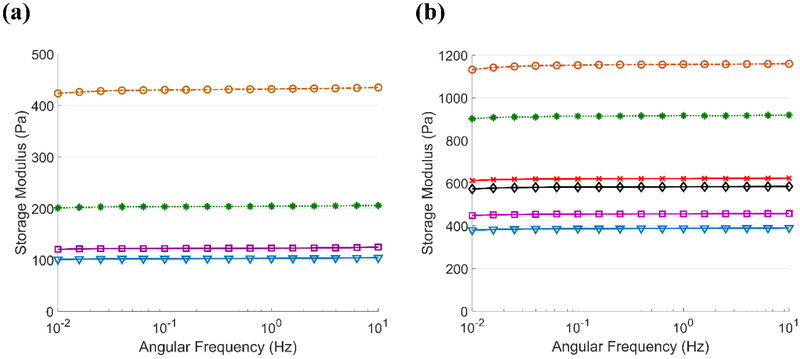

Frequency-sweep tests were employed after hydrogel curing to analyze the effects of COOH- and OH-CNT concentration on the storage modulus (Figure 8). Regardless of the CNT type, the storage modulus depends highly on the CNT concentration, but not on the frequency. The maximum storage modulus for both types of CNTs was observed using the sample with a 250 μg/ml CNT concentration. Increasing the concentration to 750 μg/ml gradually decreased the storage modulus. In OH-CNT hydrogels, 1000 μg/ml and 1250 μg/ml concentrations yielded a greater storage modulus in comparison with the 750 μg/ml sample.

Figure 8.

The effect of CNT concentration on the storage modulus of composite hydrogels; (a) Carboxylic CNT groups (b) Hydroxylic CNT groups (Downward-pointing triangle: Control, Circle: CNT250, Asterisk: CNT500, Square: CNT750, Diamond: CNT1000, Cross: CNT1250).

A comparison between the values in Figure 7 and Figure 8 indicates that the storage modulus of the OH-CNT samples is greater than that of the COOH-CNT samples, and the gelation time of the OH-CNT hydrogels is shorter than that of the COOH-CNT ones. These differences are due to the different crosslinker concentrations. Using a tilted tube test, it was found that the OH-CNT hydrogels do not crosslink when 0.005% glyoxal is used. Therefore, the concentration of glyoxal used for OH-CNT samples was increased to 0.00625%. Increasing the concentration of crosslinker accelerated gelation and increased stiffness. The OH-CNT samples followed the same trends as those of the COOH-CNT hydrogels.

3.4. Biological characterization

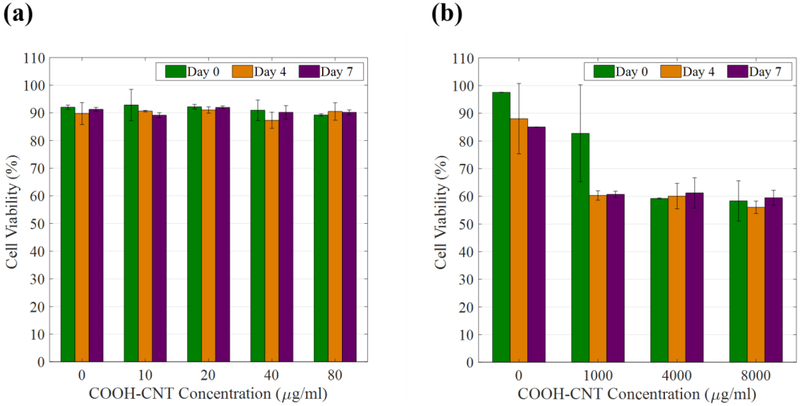

Three parameters were found to significantly affect the biocompatibility of CNT-based hydrogels: 1) the exposure time; 2) the CNT concentration; and 3) the functionalization type. Figure 9-a shows the cell viability rate for different low-range COOH-CNT concentrations over a period of one week. For the low concentration tests, all samples maintained a cell viability of over 90%. Since the COOH-CNT low concentration groups did not show any cytotoxic effect, the concentration was increased 100-fold. The viability rates significantly decreased when higher concentrations of CNT were incorporated, as shown in Figure 9-b. For samples with concentrations over 1000 μg/ml, the cell viability rate decreased to about 60%, which indicates cytotoxicity. At this point, the upper limit for the feasible COOH-CNT concentration was determined, and the results of medium concentration test confirmed the maximum allowable amount of COOH-CNT in the hydrogel.

Figure 9.

Cell viability rate for (a) low and (b) high concentrations of COOH-CNT in the first week of exposure.

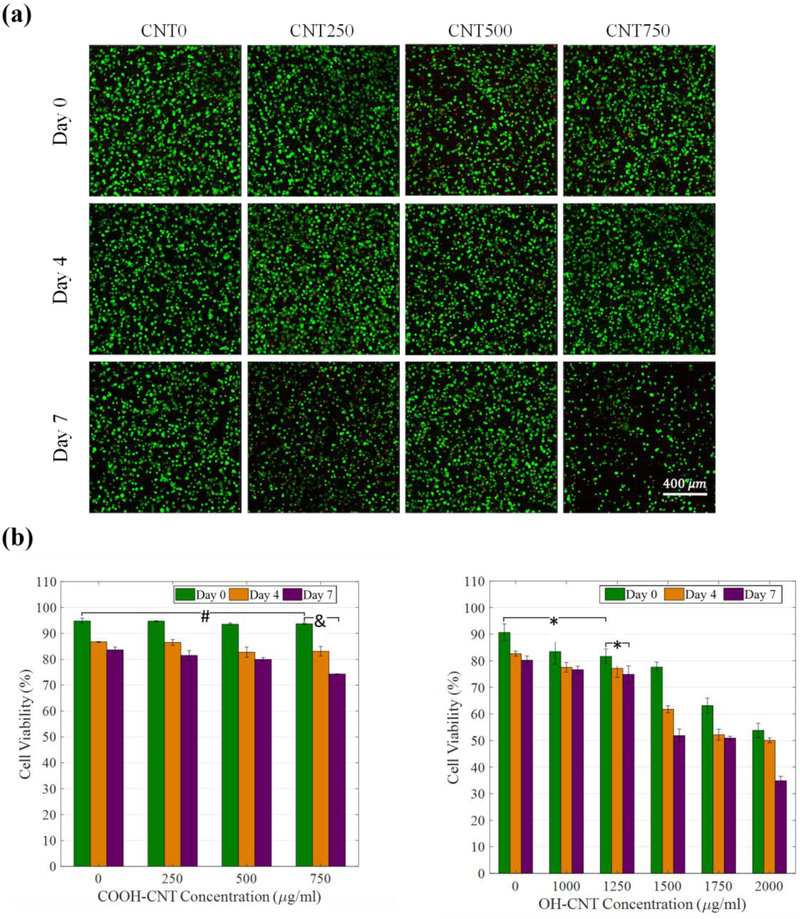

Figure 10-a shows CLSM images of medium concentration samples. In this range of concentration, the cell viability rate for all samples was similar to that for the control sample, as shown in Figure 10-b, left. There is a clear relationship between cell viability rate, exposure time, and CNT concentration. The viability rate falls as the exposure time and the COOH-CNT concentration increase. On day seven, a viability rate of 75%, which is considered as the threshold of viability, was obtained for the sample with a CNT concentration of 750 μg/ml. This was deemed the maximum COOH-CNT concentration in glycol chitosan hydrogel that can be used in 3D culture of HVFFs without causing any significant cytotoxicity.

Figure 10.

(a) Representative CLSM images of HVFFs encapsulated in composite GC hydrogels containing medium concentration carboxylic CNTs. The 3D images were used for determining the viability rate of the hydrogels (Green: live cells, Red: Dead cells). (b) Cell viability rate for medium concentration carboxylic and hydroxylic CNT groups. #p < 0.2 corresponds to an insignificant difference, &p < 10−5, *p < 0.01.

To determine the effect of CNTs’ functional group, OH-CNTs were also tested. A set of cell viability tests was performed. The maximum allowable OH-CNT concentration was found to be 1250 μg/ml (Figure 10-b, right), which is greater than that of the COOH-CNT samples. This proves that, although their dispersion is more problematic, the level of biocompatibility for OH-CNTs is greater than that of the COOH-CNTs. In the case of OH-CNT samples, the cell viability rates for day zero samples are significantly different, which confirms that the addition of OH-CNTs to a glycol chitosan hydrogel causes a short-term cytotoxicity.

4. Discussion

Higher concentrations of COOH-CNT and OH-CNT introduce more acidic and basic groups in the hydrogel, respectively. This changes the pH of the hydrogel, which can affect cell viability [51]. It is generally accepted that the cells maximum growth rate occurs at pH 7.4 – 7.5, which is the physiological pH level [52]. The pH of the control samples (without CNT) was measured to be 7.2 – 7.4. When OH-CNTs were added to the hydrogel, the OH functional groups caused the pH to slightly increase towards the physiological pH level. However, acidic functional groups in COOH-CNT decrease the pH away from the physiological range, which is not desirable. Therefore, the maximum allowable CNT concentration for OH-CNT hydrogels is greater than that for the COOH-CNT samples.

It was found that the addition of functionalized CNTs to glycol chitosan hydrogel has two competing effects. Firstly, the addition of CNTs increased the storage modulus of the composite hydrogel, since the stiffness of CNTs is much greater than that of the matrix. Conversely, the abundance of functional groups in the composite hydrogel impeded fast and complete crosslinking of glycol chitosan polymer chains when the CNT concentration increased. Slow and incomplete crosslinking of the hydrogel network resulted in an increase in gelation time and a decrease in storage modulus. Therefore, greater CNT concentrations do not necessarily cause an increase in the storage modulus.

For OH-CNT concentrations up to 750 μg/ml, the hydroxylic groups play the role of limiting reactant in chemical crosslinking reaction. Thus, in this range, the gelation time depends on the concentration of functional groups. When higher concentrations are introduced, e.g. 1000 μg/ml and 1250 μg/ml, the functional groups are the excess reactants, and the gelation time does not change with increasing the OH-CNT concentration. However, the storage modulus of the 1000 μg/ml sample is greater than that of 750 μg/ml sample, which is due to the higher concentration of stiff CNTs.

Our findings suggest that using COOH-CNT in glycol chitosan/ glyoxal hydrogel enhanced the swelling ratio and the porosity of the hydrogel. Since the cationization of amine groups is facilitated in an acidic environment [53], samples with higher concentrations of COOH-CNT absorb more PBS, and thus, have a greater swelling ratio. The greater swelling ratio resulted in a larger average pore size, which may promote cell migration. The addition of OH-CNTs did not alter the absorbance capacity of the hydrogels, which is due to the higher concentration of crosslinker [54]. Therefore, the OH-CNT neither affected the swelling ratio nor the average pore size of the hydrogel.

Other types of fibers such as collagen type I and III have been used in composite hydrogels [49]. Table 1 compares the impact of adding different fibers to glycol chitosan/glyoxal hydrogel. The addition of collagen and CNT fibers caused similar trends in pore size change. The swelling ratio did not change when collagen fibers were added. The storage modulus and gelation time of CNT-based composite hydrogels may be smaller or greater based on the concentration of fibers. This may allow the fine tuning of the storage modulus through the addition of CNTs.

Table 1.

The effects of adding different fibers to glycol chitosan hydrogel

| COOH-CNT | OH-CNT | Collagen I and III [49] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pore size | Increase | Constant | Increase |

| Swelling Ratio | Increase | Constant | Constant |

| Storage Modulus | Concentration dependent | Concentration dependent | Increase |

| Gelation Time | Concentration dependent | Concentration dependent | Decrease |

5. Conclusion

In the present study, the addition of carboxylic and hydroxylic CNTs in a glycol chitosan hydrogel matrix was explored for possible application as an injectable biomimetic hydrogel for vocal folds treatment. The two types of CNTs underwent biological, rheological, and physical tests. Although COOH-CNTs exhibited a lower biocompatibility in comparison with OH-CNTs, they were found to be preferable as they caused a 120% enlargement in the hydrogels’ pore size. Such increase in porosity has not been previously reported. It was found that the gelation time and the mechanical properties of the CNT-based composite hydrogels do not necessarily change in proportion with the CNT concentration. In conclusion, we found that carboxylic functionalized CNTs increase the average pore size of the glycol chitosan hydrogel. A larger pore size may improve cell migration through the tissue, which will be the subject of future investigations.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Glycol chitosan/CNT-based composite hydrogels were evaluated for tissue engineering applications.

The maximum concentrations of COOH- and OH-CNTs for 75% cell viability were found to be 750 μg/ml. and 1250 μg/ml., respectively.

The effects of CNT concentration on the mechanical properties, swelling rate, and gelation time of the glycol chitosan hydrogel were quantified.

The porosity of the hydrogel was found to increase by 120% following the incorporation of COOH-CNTs.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), NIH grant number R01-DC005788 (Mongeau, PI). Confocal images were collected and image processing and analysis for this manuscript were performed in the McGill University Life Sciences Complex Advanced Bioimaging Facility (ABIF). SEM and TEM images were obtained in the McGill University Facility for Electron Microscopy Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Data Availability

The raw/processed data required to reproduce these findings cannot be shared at this time as the data also forms part of an ongoing study.

References

- 1.Titze IR and Martin DW, Principles of voice production. 1998, ASA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirano M, Morphological Structure of the Vocal Cord as a Vibrator and its Variations. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica, 1974. 26(2): p. 89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Y, et al. , A biphasic theory for the viscoelastic behaviors of vocal fold lamina propria in stress relaxation. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 2008. 123(3): p. 1627–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karle WE and Pitman MJ, Vocal Fold Regeneration. Textbook of Laryngology, 2017: p. 372. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wrona EA, et al. , Extracellular Matrix for Vocal Fold Lamina Propria Replacement: A Review. Tissue Engineering Part B: Reviews, 2016. 22(6): p. 421–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan RW, Gray SD, and Titze IR, The importance of hyaluronic acid in vocal fold biomechanics. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 2001. 124(6): p. 607–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hahn MS, et al. , Quantitative and Comparative Studies of the Vocal Fold Extracellular Matrix I: Elastic Fibers and Hyaluronic Acid. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, 2006. 115(2): p. 156–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hahn MS, et al. , Quantitative and Comparative Studies of the Vocal Fold Extracellular Matrix II: Collagen. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, 2006. 115(3): p. 225–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray SD, et al. , Biomechanical and Histologic Observations of Vocal Fold Fibrous Proteins. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, 2000. 109(1): p. 77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunter EJ, Smith ME, and Tanner K, Gender differences affecting vocal health of women in vocally demanding careers. Logopedics, Phoniatrics, Vocology, 2011. 36(3): p. 128–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy W, Black J, and Hastings GW, Handbook of biomaterial properties. 2016: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mallur PS and Rosen CA, Vocal fold injection: review of indications, techniques, and materials for augmentation. Clinical and experimental otorhinolaryngology, 2010. 3(4): p. 177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duflo S, et al. , Vocal fold tissue repair in vivo using a synthetic extracellular matrix. Tissue engineering, 2006. 12(8): p. 2171–2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thibeault SL, et al. , In vivo engineering of the vocal fold ECM with injectable HA hydrogels—late effects on tissue repair and biomechanics in a rabbit model. Journal of Voice, 2011. 25(2): p. 249–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansen JK, et al. , In vivo engineering of the vocal fold extracellular matrix with injectable hyaluronic acid hydrogels: early effects on tissue repair and biomechanics in a rabbit model. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, 2005. 114(9): p. 662–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thibeault SL and Duflo S, Inflammatory cytokine responses to synthetic extracellular matrix injection to the vocal fold lamina propria. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, 2008. 117(3): p. 221–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hertegård S, et al. , Cross-linked hyaluronan versus collagen for injection treatment of glottal insufficiency: 2-year follow-up. Acta oto-laryngologica, 2004. 124(10): p. 1208–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molteni G, et al. , Auto-crosslinked hyaluronan gel injections in phonosurgery. Otolaryngology--Head and Neck Surgery, 2010. 142(4): p. 547–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heris HK, et al. , Investigation of chitosan-glycol glyoxal as an injectable biomaterial for vocal fold tissue engineering. Procedia Engineering, 2015. 110: p. 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heris HK, et al. , Investigation of the Viability, Adhesion, and Migration of Human Fibroblasts in a Hyaluronic Acid Gelatin Microgel- Reinforced Composite Hydrogel for Vocal Fold Tissue Regeneration. Advanced healthcare materials, 2016. 5(2): p. 255–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Esteves IAAC, et al. , Determination of the surface area and porosity of carbon nanotube bundles from a Langmuirian analysis of sub- and supercritical adsorption data. Carbon, 2009. 47(4): p. 948–956. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lalwani G, et al. , Porous three- dimensional carbon nanotube scaffolds for tissue engineering. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A, 2015. 103(10): p. 3212–3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun Y-P, et al. , Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes: Properties and Applications. Accounts of Chemical Research, 2002. 35(12): p. 1096–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tonelli FMP, et al. , Carbon nanotube interaction with extracellular matrix proteins producing scaffolds for tissue engineering. International Journal of Nanomedicine, 2012. 7: p. 4511–4529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhattacharyya S, et al. , Carbon nanotubes as structural nanofibers for hyaluronic acid hydrogel scaffolds. Biomacromolecules, 2008. 9(2): p. 505–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu C, et al. , Gelation in carbon nanotube, polymer composites. Polymer, 2003. 44(24): p. 7529–7532. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smart SK, et al. , The biocompatibility of carbon nanotubes. Carbon, 2006. 44(6): p. 1034–1047. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pulskamp K, Diabate S, and Krug HF, Carbon nanotubes show no sign of acute toxicity but induce intracellular reactive oxygen species in dependence on contaminants. Toxicology letters, 2007. 168(1): p. 58–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu X, et al. , Acute Nanoparticle Exposure to Vocal Folds: A Laboratory Study. Journal of Voice, 2017. 31(6): p. 662–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muller J, et al. , Respiratory toxicity of multi-wall carbon nanotubes. Toxicology and applied pharmacology, 2005. 207(3): p. 221–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Werengowska-Ciećwierz K, et al. , Conscious changes of carbon nanotubes cytotoxicity by manipulation with selected nanofactors. Applied biochemistry and biotechnology, 2015. 176(3): p. 730–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin Y, et al. , Advances toward bioapplications of carbon nanotubes. Journal of Materials Chemistry, 2004. 14(4): p. 527–541. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tran PA, Zhang L, and Webster TJ, Carbon nanofibers and carbon nanotubes in regenerative medicine. Advanced drug delivery reviews, 2009. 61(12): p. 1097–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang F and Chen B, A review on biomedical applications of single-walled carbon nanotubes. Current medicinal chemistry, 2010. 17(1): p. 10–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tekade R, Maheshwari R, and Jain N, Toxicity of nanostructured biomaterials, in Nanobiomaterials. 2017, Elsevier, p. 231–256. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sayes CM, et al. , Functionalization density dependence of single-walled carbon nanotubes cytotoxicity in vitro. Toxicology letters, 2006. 161(2): p. 135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vardharajula S, et al. , Functionalized carbon nanotubes: biomedical applications. International journal of nanomedicine, 2012. 7: p. 5361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Treacy MMJ, Ebbesen TW, and Gibson JM, Exceptionally high Young’s modulus observed for individual carbon nanotubes. Nature, 1996. 381: p. 678. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gaharwar AK, Peppas NA, and Khademhosseini A, Nanocomposite hydrogels for biomedical applications. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 2014. 111(3): p. 441–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shin SR, et al. , Carbon nanotube reinforced hybrid microgels as scaffold materials for cell encapsulation. ACS nano, 2011. 6(1): p. 362–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harunaga JS and Yamada KM, Cell-matrix adhesions in 3D. Matrix Biology, 2011. 30(7–8): p. 363–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan RW and Titze IR, Viscoelastic shear properties of human vocal fold mucosa: Measurement methodology and empirical results. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 1999. 106(4): p. 2008–2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamauchi A, et al. , Age-and gender-related difference of vocal fold vibration and glottal configuration in normal speakers: analysis with glottal area waveform. Journal of Voice, 2014. 28(5): p. 525–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhukhovitskaya A, et al. , Gender and age in benign vocal fold lesions. The Laryngoscope, 2015. 125(1): p. 191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moura MJ, Figueiredo MM, and Gil MH, Rheological study of genipin cross-linked chitosan hydrogels. Biomacromolecules, 2007. 8(12): p. 3823–3829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Domingues RM, et al. , Development of injectable hyaluronic acid cellulose nanocrystals bionanocomposite hydrogels for tissue engineering applications. Bioconjugate chemistry, 2015. 26(8): p. 1571–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu X, et al. , Carbon Nanotubes Reinforced Maleic Anhydride-Modified Xylan-g-Poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) Hydrogel with Multifunctional Properties. Materials, 2018. 11(3): p. 354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ghobril C and Grinstaff M, The chemistry and engineering of polymeric hydrogel adhesives for wound closure: a tutorial. Chemical Society Reviews, 2015. 44(7): p. 1820–1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Latifi N, et al. , A tissue-mimetic nano-fibrillar hybrid injectable hydrogel for potential soft tissue engineering applications. Scientific reports, 2018. 8(1): p. 1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kenn K and Balkissoon R, Vocal cord dysfunction: what do we know? European Respiratory Journal, 2011. 37(1): p. 194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kruse CR, et al. , The effect of pH on cell viability, cell migration, cell proliferation, wound closure, and wound reepithelialization: in vitro and in vivo study. Wound Repair and Regeneration, 2017. 25(2): p. 260–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ceccarini C and Eagle H, pH as a determinant of cellular growth and contact inhibition. Proceedings of the national academy of Sciences, 1971. 68(1): p. 229–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Park H, Park K, and Kim D, Preparation and swelling behavior of chitosan- based superporous hydrogels for gastric retention application. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A, 2006. 76(1): p. 144–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chuang E-Y, et al. , Hydrogels for the Application of Articular Cartilage Tissue Engineering: A Review of Hydrogels. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering, 2018. 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.