Abstract

Small open reading frames (smORFs) encoding polypeptides of less than 100 amino acids in eukaryotes (50 amino acids in prokaryotes) were historically excluded from genome annotation. However, recent advances in genomics, ribosome footprinting, and proteomics have revealed thousands of translated smORFs in genomes spanning evolutionary space. These smORFs can encode functional polypeptides, or act as cis-translational regulators. Herein we review evidence that some smORF-encoded polypeptides (SEPs) participate in stress responses in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, and that some upstream ORFs (uORFs) regulate stress-responsive translation of downstream cistrons in eukaryotic cells. These studies provide insight into a regulated subclass of smORFs and suggest that at least some smORF-encoded microproteins may participate in maintenance of cellular homeostasis under stress.

Graphical Abstract

Increasing evidence suggests that some small open reading frame-encoded polypeptides (SEPs) function in prokaryotic and eukaryotic cellular stress responses.

Introduction

The FANTOM genome annotation consortium initially relied on a 100 amino acid cutoff to distinguish eukaryotic protein coding sequences because a large number of spurious ORFs of shorter lengths occur randomly within long non-coding RNAs1, 2. In prokaryotes, a cutoff of 50 amino acids was used3. However, with the advent of proteogenomic4 technologies, thousands of previously unannotated small open reading frames (smORFs)3, 5 encoding products of fewer than 100 amino acids have been shown to undergo translation in organisms spanning all domains of life, including bacteria, yeast, flies, mouse, and human6–17. With this increase in coding sequence annotation comes a need to determine the functions of smORF-encoded polypeptides (SEPs). Three classes of smORFs have been proposed in eukaryotes18, based on RNA “location” and conservation: (1) non-functional intergenic smORFs that may represent newly evolving genes19 (2) smORFs that encode functional SEPs and (3) translated upstream ORFs (uORFs) encoded in 5’ untranslated regions of mRNA that function as cis-translational regulators of downstream coding sequences. Classes 1 and 2 may also be relevant to bacteria.

One-by-one characterization has shown that dozens of functional SEPs play roles in important biological processes, often by regulating the activity of macromolecular complexes20. Increasing evidence suggests that a subset of smORFs participate in cellular stress responses21. Cellular stress responses are evolutionarily conserved molecular responses to changes in environment that would otherwise disrupt homeostasis by damaging cellular molecules22. These stresses can include temperature, reactive oxygen species, hypoxia, nutrient limitation, and other conditions to which cells must respond in order to survive. In this review, we first consider the functions of bacterial SEPs in stress response pathways (Figure 1a), and secondly consider both functional and regulatory roles of eukaryotic SEPs.

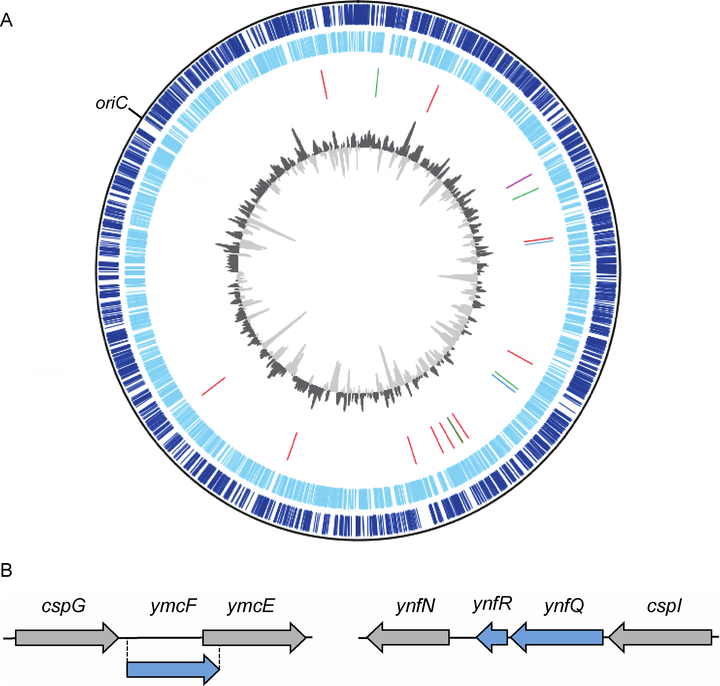

Figure 1. Locations of stress-response associated small open reading frames (smORFs) in the E. coli str. K-12 substr. MG1655 genome.

(A) Map of the E. coli str. K-12 substr. MG1655 genome. Tracks from the outside to inside represent: 1. Annotated coding sequences within the forward strand (dark blue). 2. Annotated coding sequences within the complement strand (light blue). 3. Stress-responsive smORFs discussed in this review, by color: cold shock (blue)23, 24, heat shock (red)21, 25, antibiotic stress-inducible (purple)26, and nutrient sensing (green)27–30. (4) Percent GC plot with above average GC content in dark gray and below average GC content in light gray. Genome sequence, annotated coding sequences, and stress-responsive smORFs (tracks 1–3) were uploaded to DNAPlotter version 1.031 and selected to construct the map using NCBI RefSeq assembly accession: GCF_000005845.2. (B) Scale diagrams of the cspG and cspI genomic regions; previously annotated genes are depicted as gray arrows and recently discovered cold-inducible smORFs are depicted as blue arrows23, 24.

smORFs and bacterial stress responses

Early evidence for the regulated expression of SEPs during cellular stress came from the study of prokaryotes, and a number of stress-response bacterial SEPs have been characterized both at the phenotypic and molecular levels3, 21, 32. In this section, we discuss SEP expression during various stress responses, then detail the functions and mechanisms of selected stress-response SEPs in both Gram-negative and -positive bacteria.

Regulated smORF expression during cellular stress in bacteria

Bacterial responses to extracellular stress are governed both transcriptionally and post-transcriptionally33–36. Transcriptional responses are mediated by dedicated transcription factors, such as σS/RpoS in Gram-negative and σB/SigB in Gram-positive bacteria, which are required for the general stress response (reviewed in refs. 35 and 36, respectively). Post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms include small regulatory RNAs (sRNA)34, RNA conformational changes37, and RNA binding proteins; unique among bacterial stress responses, the cold shock response is largely mediated by post-transcriptional mechanisms38. These transcriptional and post-transcriptional responses govern alterations to the transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome that are required to re-establish homeostasis. Regulated expression of smORFs after exposure to a cellular stress has therefore led to the hypothesis that the encoded SEPs may function in the corresponding stress response.

The seminal observation by Storz and colleagues that ~40% of a set of 51 newly discovered Escherichia coli (E. coli) smORFs exhibited differential expression during stress responses, including heat shock, oxidative stress, and low pH, provided the first strong evidence that smORFs function during stress21. Interestingly, some of these smORFs are post-transcriptionally regulated, such as yobF during heat shock. Importantly, subsequent phenotypic analysis in E. coli showed that deletion of three of these smORFs, yqcG, ybhT, and yobF, renders cells sensitive to envelope stress, and the yobF deletion strain was severely sensitive to acid stress32. However, the molecular or biochemical function of YobF in response to heat shock, cell envelope stress, and acid stress has not yet been defined.

Proteomic and genomic approaches have subsequently been applied to identify additional temperature stress-regulated SEPs in E. coli K-12. Quantitative proteomics of small membrane proteins revealed an unannotated peptide mapping to a putative smORF, gndA, that is encoded within the gnd gene in an alternative reading frame (and is therefore independent at the amino acid level)25. Genomic tagging revealed that GndA expression is only detectable during heat shock. In parallel studies, three novel cold-inducible SEPs have been reported (Figure 1b). Quantitative proteomics of E. coli K-12 revealed peptides YmcF and YnfQ which are specifically induced by cold shock23. These peptides map to two unannotated, intergenic sequences downstream of cold shock genes cspG and cspI, respectively. YmcF and YnfQ are upregulated by cold shock by up to a factor of 10, and exhibit 66% sequence identity, suggesting possible functional overlap. Interestingly, both of these cold-inducible smORFs initiate at AUU start codons, consistent with regulated expression39. Subsequent work by Hemm and coworkers identified an additional 21 amino acid smORF, ynfR, downstream of ynfQ, that is also cold-inducible24.

SEPs are stress-inducible in diverse bacterial species. For example, three smORFs (sbrABC) recently discovered in Staphylococcus aureus are expressed in a SigB-dependent manner40. sbrA and sbrB encode SEPs that are 26 and 38 amino acids, respectively, while sbrC may encode a sRNA. In a second case, transcriptomic analyses of the photosynthetic cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 revealed three SEPs, NsiR6, HliR1, and Norf1, that were induced by stress conditions, including transfer of the cyanobacteria from light to darkness41. The nsir6 and hlir1 transcripts (nitrogen stress-induced RNA 6 and high light inducible RNA 1) were previously annotated as noncoding RNAs.

Antibiotic stress

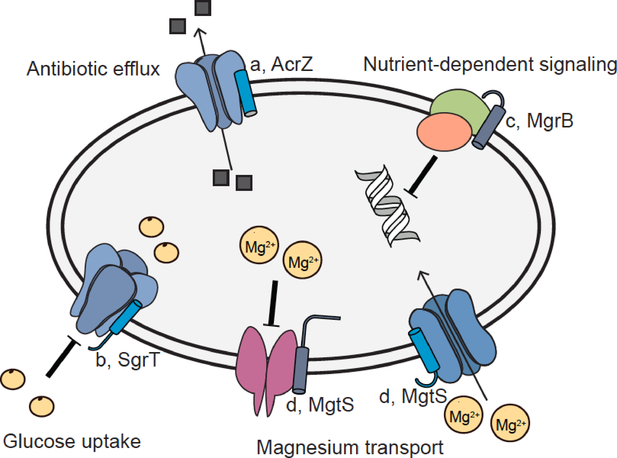

Antibiotics activate several bacterial stress pathways and can induce the stringent response via (p)ppGpp signaling42. Certain antibiotics and therapeutics such as ciprofloxacin and mitomycin C induce the SOS response43. A key antibiotic stress response linked to development of resistance is expression of drug efflux pumps26. The 49 amino acid membrane-bound AcrZ interacts with the AcrAB-TolC drug efflux pump, which exports some classes of antibiotics to confer resistance (Figure 2a)26. For example, strains lacking acrZ are sensitive to chloramphenicol and tetracycline, but not to erythromycin or rifampicin. While the mechanism of AcrZ is not fully characterized, AcrZ interacts directly with AcrB, which is hypothesized to lead to a conformational change in AcrB and export of specific antibiotics26.

Figure 2. Putative functions of selected membrane-bound bacterial stress-responsive microproteins.

a) AcrZ enhances export of specific antibiotics by the drug efflux pump AcrAB-TolC26; b) SgrT expression is induced by high intracellular levels of glucose 6-phosphate to inhibit glucose uptake27; c) MgrB regulates PhoPQ (green and orange circles) in low intracellular Mg2+, decreasing expression of PhoPQ-dependent genes28; d) MgtS increases Mg2+ uptake and prevents Mg2+ export29, 47.

Nutrient sensing and utilization

Specific pathways have evolved to maintain homeostasis during nutrient stress, which can arise from either nutrient limitation or accumulation3. An early report linking smORF expression to nutrient status showed that the 227 nt sgrS sRNA in E. coli is expressed during glucose 6-phosphate accumulation27. sgrS also encodes the 43-amino acid SEP SgrT (Figure 2b)27. The bifunctional sgrS/sgrT gene inhibits the glucose permease PtsG at both the RNA and protein level. Under conditions of high intracellular glucose 6-phosphate, the sgrS sRNA inhibits translation of the ptsG mRNA, while the SgrT SEP binds to PtsG and inhibits glucose uptake. Overexpression of SgrT renders cells incapable of growth on glucose44. Interestingly, preliminary studies suggest that SEPs may be linked to monosaccharide utilization in other organisms, such as Brucella abortus, in which three recently identified, stress-inducible, membrane-localized SEPs increase cell growth rate on L-fucose45.

Bacterial SEPs are also inducible and functional during divalent metal ion stress. When intracellular Mg2+ is low, PhoPQ upregulates gene expression, including the smORF mgrB46. E. coli MgrB (Figure 2c), a 47-amino acid SEP, interacts with PhoQ to inhibit its autophosphorylation and activation28. Induction of the SEP MgtS (Figure 2d) is also observed in a PhoPQ-dependent manner. MgtS co-purifies with the Mg2+ ATPase MgtA, leading to its stabilization and increased Mg2+ import29. This membrane-bound SEP also interacts with the PitA cation-phosphate transporter to prevent Mg2+ export47. In contrast, accumulation of Mn2+ can be toxic to cells48. The SEP MntS is repressed by the manganese-dependent transcriptional regulator MntR at high manganese, and overexpression of MntS leads to increased manganese sensitivity30. MntS may function to increase intracellular Mn2+ at low Mn2+ concentrations49.

Prli42 and the Listeria monocytogenes stressosome

The stressosome is a ~1 MDa cytosolic complex that regulates the general stress response in Gram-positive bacteria50. The stressosome senses extracellular stress and, through a previously undefined mechanism, initiates intracellular signaling to activate SigB. Cossart and colleagues recently utilized an N-terminalomics approach to identify Prli42, a membrane-associated, 31-amino acid SEP that binds to the stressosome subunit RbsR and anchors RbsR to the membrane51. Loss of Prli42 or the Prli42-RbsR interaction renders cells sensitive to oxidative stress and decreases expression of virulence factors in Listeria, suggesting that Prli42 is required for signaling by the stressosome during stress and host infection. Prli42 therefore provides a model of a SEP-protein interaction that regulates stress-response signaling in bacteria.

smORFs and eukaryotic stress responses

Upstream smORFs (uORFs) and translational regulation during stress

Translational regulation of the proteome is an important component of eukaryotic stress responses and may occur more rapidly than transcriptional responses; more expression-level changes occur at the protein level (several thousand genes) than at the mRNA level (hundreds of genes) during stresses such as glucose and oxygen deprivation52. Generally, global protein translation is downregulated during cellular stress, while translation of a subset of stress-response proteins remains constant or increases53–55. A specific class of eukaryotic smORFs - upstream ORFs (uORFs) – play a role in stress-dependent translational regulation of downstream cistrons56–58. Recent global profiling studies in yeast, plants and mammals9, 13, 59, 60 have shown that uORF translation is widespread, especially following cellular stress61. Ribosome profiling of oxidatively stressed yeast results in rapid accumulation of ribosomes on transcripts bearing uORFs following five minutes of hydrogen peroxide exposure62. This observation is paralleled in human cells affected by oxidative stress63, as well as oxygen and glucose deprivation52.

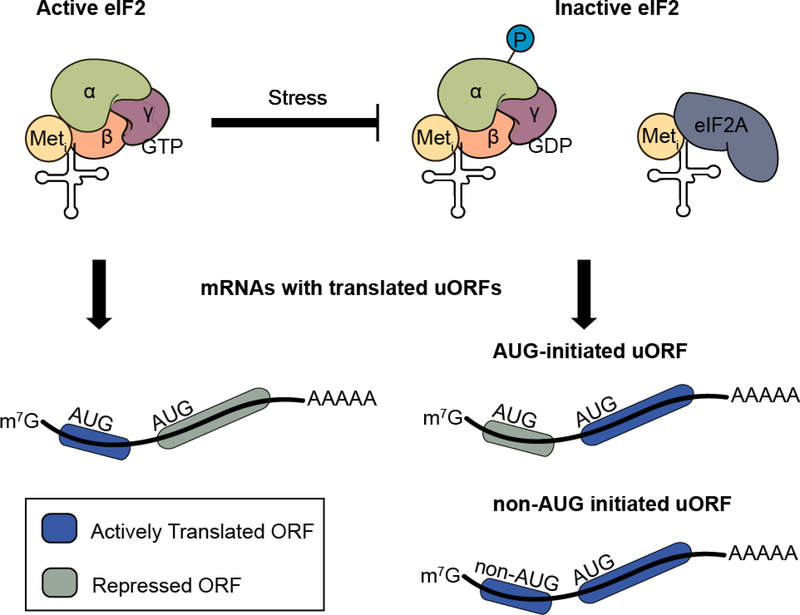

The prevailing model of uORF-mediated translational regulation holds that translating a uORF prevents scanning and/or re-initiation at the downstream coding sequence. Re-initiation is dependent on the distance between the uORF and downstream cistron64, 65. While uORFs were initially reported to act as cis-translational inhibitors of downstream coding sequences within the same mRNA56, 66, 67, it has become clear that uORFs can either down- or upregulate downstream protein translation depending on the uORF start codon. AUG-initiated uORFs typically compete for translation with their downstream ORFs under normal growth conditions68, 69. In contrast, uORFs initiating with near-cognate (non-AUG) start codons are more likely to exhibit positively correlated translation with downstream coding sequences 70. Non-AUG initiated uORFs may also play a role in upregulating downstream proteins previously thought to undergo non-canonical initiation under stress conditions or global translational arrest, as demonstrated during nutrient starvation and meiosis70, 71. However, the presence or sequence of a uORF is not sufficient to predict translational regulation during stress.

uORF-mediated regulation of protein translation occurs as a result of changes in the pre-initiation complex. During the integrated stress response, the trimeric eIF2 complex, which is responsible for initiator tRNA delivery to the 40S ribosome, is repressed through phosphorylation of the eIF2α subunit72. This repression of eIF2 activity has several effects on translation: global protein translation is downregulated 73, AUG-initiated uORFs are skipped by the preinitiation complex, relieving their inhibition of downstream protein translation74, and the weak eIF2 competitor eIF2A is de-repressed and delivers initiator tRNA to selected sites75 including non-AUG codon-initiated uORFs76, driving their translation during stress (Figure 3). For example, eIF2A drives translation of two uORFs initiating with UUG and CUG start codons and induces expression of the downstream cistron encoding binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP), an ER-resident chaperone vital for the activation of the integrated stress response76. This mechanism also operates in squamous cell carcinoma tumorigenesis, in which eIF2A-dependent translation drives a 1.8-fold increase in uORF occupancy by ribosomes77.

Figure 3. Regulated translation of upstream open reading frame (uORF)-containing transcripts under cellular stress.

Under normal conditions, active eIF2 is abundant and, in the subset of transcripts that contain them, AUG-initiated uORFs are translated, downregulating expression of the downstream ORF. Stress induces phosphorylation of the eIF2α subunit and results in eIF2 inactivation. Limiting eIF2 concentrations cause ribosomes to bypass AUG-initiated uORFs and drive downstream ORF translation. Simultaneously, weak eIF2 competitor eIF2A can activate translation of non-AUG initiated uORFs in the transcripts that contain them.

uORFs are generally thought to compete for scanning ribosomes, which can then only initiate translation of downstream coding sequences via leaky scanning or re-initiation73, implying that the regulatory function of uORFs should depend only on their translation and therefore be independent of their sequences. In a few cases, however, the specific amino acid sequence of a uORF is required for its regulatory activity78–80. An early report of this phenomenon described a uORF in the 5’ untranslated region (UTR) of DDIT3, which encodes the CHOP protein, a transcription factor that promotes a switch from stress response signaling to cell death81. Translation of the uORF alone is insufficient to recapitulate translational downregulation of CHOP, as introduction of nonsense and missense mutations within the uORF alleviated translational repression of CHOP, whereas silent mutations did not81. Further mutational analysis defined an IPI motif within the uORF that promotes ribosome stalling to inhibit CHOP translation in cis82. Fungal uORFs in the 5’ UTR of arginine biosynthetic genes ARG2 and CPA1 also regulate downstream protein production in cis in a sequence-dependent manner via ribosome stalling83–87.

Taken together, these studies show that uORF translational regulation plays a key role in proteomic reprogramming during cellular stress responses. While several uORFs have been reported to sequence-specifically induce ribosome stalling, translated products of uORFs have generally been assumed to lack function at the polypeptide level (though the uORF-encoded MIEF1 microprotein, which binds to and regulates the mitochondrial ribosome, presents a counterexample74). In contrast, conserved smORFs encoded in dedicated transcripts have been proposed to be functional20, and a number of these smORFs are involved in mediating stress responses76.

Functional stress-response smORFs in eukaryotes

Characterization of SEPs that function in eukaryotic cellular and organismal stress responses is dramatically accelerating. Several recent reports have implicated SEPs in response to infection and innate immunity. First, ribosome profiling of influenza virus-infected human lung cancer cells identified 19 novel smORFs in long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and other non-coding RNAs that were either up- or downregulated during infection88. Among these, a SEP translated from the host gene for miR-22, MIR22HG, was upregulated during infection with both wild-type influenza and NS1-mutant influenza that is rapidly cleared from cells due to interferon responses, suggesting that the MIR22HG SEP may respond to cellular stress due to viral particle exposure. More recently, ribosome profiling was applied to identify differential translation of lncRNA-encoded smORFs in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-treated mouse macrophages89. An LPS-upregulated smORF within the lncRNA Aw112010 encodes a CUG-initiated SEP that drives interleukin-12 beta expression. Characterization of a knockout mouse demonstrated that the Aw112010 SEP is essential for mucosal immunity during both Salmonella infection and colitis. While the molecular mechanisms of the MIR22HG and Aw112010 SEPs remain uncharacterized, these studies provide a link between SEP expression and infection in cells and in vivo.

The SEP humanin has been reported to protect cells from stress-induced apoptosis. Humanin was first discovered in 2001 as a neuroprotective factor in Alzheimer’s disease, conferring neuronal resistance to apoptosis by a disease variant of the amyloid precursor protein90. Humanin has subsequently been reported to play additional intracellular roles in suppressing apoptosis via Bax binding and inactivation91. While these functions suggest that humanin is protective against apoptosis downstream of cellular stress, it remains unclear how humanin is produced in cells, as its coding sequence may map to either mitochondrial or genomic DNA91.

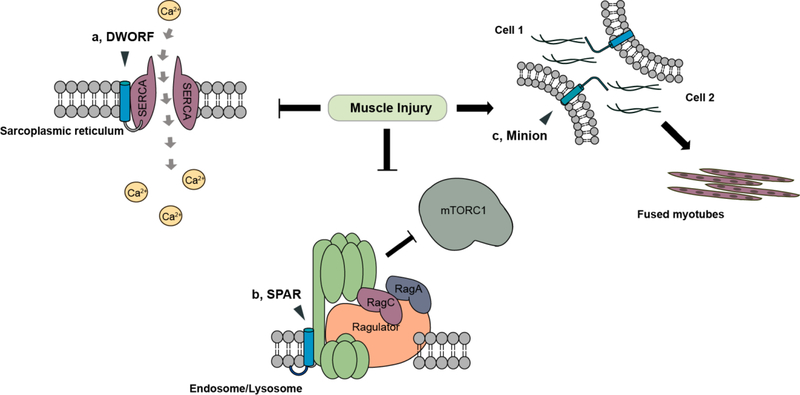

Extensive work has identified SEPs that participate in muscle regeneration following injury. DWORF92, a 34-amino acid SEP that localizes to the sarcoplasmic reticulum membrane, was identified in a lncRNA exhibiting heart- and muscle-specific expression (Figure 4a). DWORF is downregulated at the protein and mRNA level during ischemic heart failure92. DWORF normally functions to increase Ca2+ uptake into the sarcoplasmic reticulum via interaction with the Ca2+-ATPase SERCA and displacement of three other polypeptide inhibitors93–95. Decreased contractility observed during heart failure can be caused by reduced Ca2+ levels in the sarcoplasmic reticulum resulting from insufficient activity of the SERCA pump96. Activation of SERCA through DWORF overexpression restored calcium levels and heart contractility in a mouse model of heart disease97. Another example is SPAR98, a SEP encoded by lncRNA LINC00961 which is downregulated upon muscle injury (Figure 4b). SPAR normally localizes to the endosome/lysosome membrane to promote association between lysosomal v-ATPase, Ragulator, and Rag GTPases, preventing mTORC1 activation. Upon muscle injury, SPAR downregulation promotes mTORC1 activation and muscle regeneration. Conversely, Minion99 or Myomerger100, is a SEP which is transcriptionally upregulated in muscle tissue regeneration and development (Figure 4c). Skeletal muscle development and regeneration following injury proceeds through temporally regulated stem cell activation and differentiation, myoblast fusion and subsequent maturation into myofibers101, 102. CRISPR/Cas9 knockdown of Minion results in defects in myoblast fusion, while homozygous mutants are unviable, most likely due to the inability to form multinucleate myotubes. In summation, differential expression of a suite of SEPs is required for response to injury in both cardiac and skeletal muscle.

Figure 4. Microproteins influence muscle regeneration following injury.

a) In uninjured muscle, DWORF binds the SERCA calcium pump and increases calcium flow into the sarcoplasmic reticulum. b) In uninjured muscle, SPAR binds the Ragulator v-ATPase and prevents mTORC1 activation. C) Following injury, Minion mediates myoblast fusion.

Conclusion

Mounting evidence supports regulatory (in eukaryotes) and functional (in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes) roles for smORF translation in cellular stress responses. A future direction will be elucidation of the functional, molecular, and phenotypic roles of dozens of yet-uncharacterized SEPs that have been identified as differentially regulated during various stress conditions in a wide variety of organisms. While dozens of SEPs have been implicated as differentially expressed at the RNA or protein level during stress responses, post-translational regulation of SEPs, especially via post-translational modifications (PTMs), has remained largely unaddressed. Given the importance of PTMs in stress signaling73, 103, identification of stress-regulated PTMs may be informative in elucidation of SEP functions. Finally, it is tempting to speculate that the small size of smORFs allows rapid translation, consistent with a need for rapid response to external stressors; measurements of the dynamics and abundance of SEP expression relative to the rate of production of known stress response proteins could test this hypothesis. Taken as a whole, the growing literature demonstrating roles for SEPs in cellular stress provides one testable hypothesis for characterization of newly discovered smORFs, and has also improved our understanding of the full complement of regulatory factors in stress response pathways.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Searle Scholars Program, the Leukemia Research Foundation, the NIH (R01GM122984), and Yale University West Campus start-up funds (to S.A.S.). A. K. was supported in part by an NIH training grant (5T32GM06754).

References

- [1].Fickett JW (1995) ORFs and genes: How strong a connection?, J Comput Biol 2, 117–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Dinger ME, Pang KC, Mercer TR, and Mattick JS (2008) Differentiating protein-coding and noncoding RNA: Challenges and ambiguities, PLoS Comput Biol 4, e1000176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Storz G, Wolf YI, and Ramamurthi KS (2014) Small proteins can no longer be ignored, Annu Rev Biochem 83, 753–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Jaffe JD, Berg HC, and Church GM (2004) Proteogenomic mapping as a complementary method to perform genome annotation, Proteomics 4, 59–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Basrai MA, Hieter P, and Boeke JD (1997) Small open reading frames: Beautiful needles in the haystack, Genome Res 7, 768–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Frith MC, Forrest AR, Nourbakhsh E, Pang KC, Kai C, Kawai J, Carninci P, Hayashizaki Y, Bailey TL, and Grimmond SM (2006) The abundance of short proteins in the mammalian proteome, PLoS Genet 2, e52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hanada K, Higuchi-Takeuchi M, Okamoto M, Yoshizumi T, Shimizu M, Nakaminami K, Nishi R, Ohashi C, Iida K, Tanaka M, Horii Y, Kawashima M, Matsui K, Toyoda T, Shinozaki K, Seki M, and Matsui M (2013) Small open reading frames associated with morphogenesis are hidden in plant genomes, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 2395–2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hemm MR, Paul BJ, Schneider TD, Storz G, and Rudd KE (2008) Small membrane proteins found by comparative genomics and ribosome binding site models, Mol Microbiol 70, 1487–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ingolia NT, Ghaemmaghami S, Newman JR, and Weissman JS (2009) Genome-wide analysis in vivo of translation with nucleotide resolution using ribosome profiling, Science 324, 218–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ingolia NT, Lareau LF, and Weissman JS (2011) Ribosome profiling of mouse embryonic stem cells reveals the complexity and dynamics of mammalian proteomes, Cell 147, 789–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kastenmayer JP, Ni L, Chu A, Kitchen LE, Au WC, Yang H, Carter CD, Wheeler D, Davis RW, Boeke JD, Snyder MA, and Basrai MA (2006) Functional genomics of genes with small open reading frames (sORFs) in S. cerevisiae, Genome Res 16, 365–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ladoukakis E, Pereira V, Magny EG, Eyre-Walker A, and Couso JP (2011) Hundreds of putatively functional small open reading frames in Drosophila, Genome Biol 12, R118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Slavoff SA, Mitchell AJ, Schwaid AG, Cabili MN, Ma J, Levin JZ, Karger AD, Budnik BA, Rinn JL, and Saghatelian A (2013) Peptidomic discovery of short open reading frame-encoded peptides in human cells, Nat Chem Biol 9, 59–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Vanderperre B, Lucier JF, Bissonnette C, Motard J, Tremblay G, Vanderperre S, Wisztorski M, Salzet M, Boisvert FM, and Roucou X (2013) Direct detection of alternative open reading frames translation products in human significantly expands the proteome, PLoS One 8, e70698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ndah E, Jonckheere V, Giess A, Valen E, Menschaert G, and Van Damme P (2017) Reparation: Ribosome profiling assisted (re-)annotation of bacterial genomes, Nucleic Acids Res 45, e168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Miranda-CasoLuengo AA, Staunton PM, Dinan AM, Lohan AJ, and Loftus BJ (2016) Functional characterization of the Mycobacterium abscessus genome coupled with condition specific transcriptomics reveals conserved molecular strategies for host adaptation and persistence, BMC Genomics 17, 553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Potgieter MG, Nakedi KC, Ambler JM, Nel AJ, Garnett S, Soares NC, Mulder N, and Blackburn JM (2016) Proteogenomic analysis of Mycobacterium smegmatis using high resolution mass spectrometry, Front Microbiol 7, 427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Couso JP, and Patraquim P (2017) Classification and function of small open reading frames, Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 18, 575–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Carvunis AR, Rolland T, Wapinski I, Calderwood MA, Yildirim MA, Simonis N, Charloteaux B, Hidalgo CA, Barbette J, Santhanam B, Brar GA, Weissman JS, Regev A, Thierry-Mieg N, Cusick ME, and Vidal M (2012) Proto-genes and de novo gene birth, Nature 487, 370–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Saghatelian A, and Couso JP (2015) Discovery and characterization of smORF-encoded bioactive polypeptides, Nat Chem Biol 11, 909–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hemm MR, Paul BJ, Miranda-Rios J, Zhang A, Soltanzad N, and Storz G (2010) Small stress response proteins in Escherichia coli: Proteins missed by classical proteomic studies, J Bacteriol 192, 46–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kultz D (2005) Molecular and evolutionary basis of the cellular stress response, Annu Rev Physiol 67, 225–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].D’Lima NG, Khitun A, Rosenbloom AD, Yuan P, Gassaway BM, Barber KW, Rinehart J, and Slavoff SA (2017) Comparative proteomics enables identification of nonannotated cold shock proteins in E. coli, J Proteome Res 16, 3722–3731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].VanOrsdel CE, Kelly JP, Burke BN, Lein CD, Oufiero CE, Sanchez JF, Wimmers LE, Hearn DJ, Abuikhdair FJ, Barnhart KR, Duley ML, Ernst SEG, Kenerson BA, Serafin AJ, and Hemm MR (2018) Identifying new small proteins in Escherichia coli, Proteomics 18, e1700064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Yuan P, D’Lima NG, and Slavoff SA (2018) Comparative membrane proteomics reveals a nonannotated E. coli heat shock protein, Biochemistry 57, 56–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hobbs EC, Yin X, Paul BJ, Astarita JL, and Storz G (2012) Conserved small protein associates with the multidrug efflux pump AcrB and differentially affects antibiotic resistance, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, 16696–16701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wadler CS, and Vanderpool CK (2007) A dual function for a bacterial small RNA: SgrS performs base pairing-dependent regulation and encodes a functional polypeptide, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104, 20454–20459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Salazar ME, Podgornaia AI, and Laub MT (2016) The small membrane protein MgrB regulates PhoQ bifunctionality to control PhoP target gene expression dynamics, Mol Microbiol 102, 430–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wang H, Yin X, Wu Orr M, Dambach M, Curtis R, and Storz G (2017) Increasing intracellular magnesium levels with the 31-amino acid MgtS protein, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, 5689–5694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Waters LS, Sandoval M, and Storz G (2011) The Escherichia coli MntR miniregulon includes genes encoding a small protein and an efflux pump required for manganese homeostasis, J Bacteriol 193, 5887–5897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Carver T, Thomson N, Bleasby A, Berriman M, and Parkhill J (2009) DNAplotter: Circular and linear interactive genome visualization, Bioinformatics 25, 119–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hobbs EC, Astarita JL, and Storz G (2010) Small RNAs and small proteins involved in resistance to cell envelope stress and acid shock in escherichia coli: Analysis of a bar-coded mutant collection, J Bacteriol 192, 59–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Browning DF, and Busby SJ (2016) Local and global regulation of transcription initiation in bacteria, Nat Rev Microbiol 14, 638–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Olejniczak M, and Storz G (2017) ProQ/FinO-domain proteins: Another ubiquitous family of RNA matchmakers?, Mol Microbiol 104, 905–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Battesti A, Majdalani N, and Gottesman S (2011) The RpoS-mediated general stress response in Escherichia coli, Annu Rev Microbiol 65, 189–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Hecker M, Pane-Farre J, and Volker U (2007) SigB-dependent general stress response in Bacillus subtilis and related gram-positive bacteria, Annu Rev Microbiol 61, 215–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kortmann J, and Narberhaus F (2012) Bacterial rna thermometers: Molecular zippers and switches, Nat Rev Microbiol 10, 255–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Zhang Y, Burkhardt DH, Rouskin S, Li GW, Weissman JS, and Gross CA (2018) A stress response that monitors and regulates mRNA structure is central to cold shock adaptation, Mol Cell 70, 274–286 e277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kozak M (2005) Regulation of translation via mRNA structure in prokaryotes and eukaryotes, Gene 361, 13–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Nielsen JS, Christiansen MH, Bonde M, Gottschalk S, Frees D, Thomsen LE, and Kallipolitis BH (2011) Searching for small sigmab-regulated genes in Staphylococcus aureus, Arch Microbiol 193, 23–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Baumgartner D, Kopf M, Klahn S, Steglich C, and Hess WR (2016) Small proteins in cyanobacteria provide a paradigm for the functional analysis of the bacterial micro-proteome, BMC Microbiol 16, 285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Harms A, Maisonneuve E, and Gerdes K (2016) Mechanisms of bacterial persistence during stress and antibiotic exposure, Science 354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Recacha E, Machuca J, Diaz de Alba P, Ramos-Guelfo M, Docobo-Perez F, Rodriguez-Beltran J, Blazquez J, Pascual A, and Rodriguez-Martinez JM (2017) Quinolone resistance reversion by targeting the SOS response, mBio 8 : e00971–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lloyd CR, Park S, Fei J, and Vanderpool CK (2017) The small protein SgrT controls transport activity of the glucose-specific phosphotransferase system, J Bacteriol 199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Budnick JA, Sheehan LM, Kang L, Michalak P, and Caswell CC (2018) Characterization of three small proteins in Brucella abortus linked to fucose utilization, J Bacteriol 200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Groisman EA (2001) The pleiotropic two-component regulatory system PhoP-PhoQ, J Bacteriol 183, 1835–1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Yin X, Wu Orr M, Wang H, Hobbs EC, Shabalina SA and Storz G The small protein MgtS and small RNA MgrR modulate the PitA phosphate symporter to boost intracellular magnesium levels, Mol. Microbiol, 2018, 111, 131–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Anjem A, Varghese S, and Imlay JA (2009) Manganese import is a key element of the OxyR response to hydrogen peroxide in Escherichia coli, Mol Microbiol 72, 844–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Martin JE, Waters LS, Storz G, and Imlay JA (2015) The Escherichia coli small protein MntS and exporter MntP optimize the intracellular concentration of manganese, PLoS Genet 11, e1004977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Martinez L, Reeves A, and Haldenwang W (2010) Stressosomes formed in Bacillus subtilis from the RsbR protein of Listeria monocytogenes allow sigma(b) activation following exposure to either physical or nutritional stress, J Bacteriol 192, 6279–6286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Impens F, Rolhion N, Radoshevich L, Becavin C, Duval M, Mellin J, Garcia Del Portillo F, Pucciarelli MG, Williams AH, and Cossart P (2017) N-terminomics identifies Prli42 as a membrane miniprotein conserved in firmicutes and critical for stressosome activation in Listeria monocytogenes, Nat Microbiol 2, 17005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Andreev DE, O’Connor PB, Zhdanov AV, Dmitriev RI, Shatsky IN, Papkovsky DB, and Baranov PV (2015) Oxygen and glucose deprivation induces widespread alterations in mRNA translation within 20 minutes, Genome Biol 16, 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Lu PD, Harding HP, and Ron D (2004) Translation reinitiation at alternative open reading frames regulates gene expression in an integrated stress response, J Cell Biol 167, 27–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Vattem KM and Wek RC Reinitiation involving upstream ORFs regulates ATF4 mRNA translation in mammalian cells, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 2004, 101, 11269–11274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Lee YY, Cevallos RC, and Jan E (2009) An upstream open reading frame regulates translation of GADD34 during cellular stresses that induce eIF2alpha phosphorylation, J Biol Chem 284, 6661–6673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Hinnebusch AG (1997) Translational regulation of yeast GCN4. A window on factors that control initiator-tRNA binding to the ribosome, J Biol Chem 272, 21661–21664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Vilela C, Linz B, Rodrigues-Pousada C, and McCarthy JE (1998) The yeast transcription factor genes YAP1 and YAP2 are subject to differential control at the levels of both translation and mRNA stability, Nucleic Acids Res 26, 1150–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Calvo SE, Pagliarini DJ, and Mootha VK (2009) Upstream open reading frames cause widespread reduction of protein expression and are polymorphic among humans, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 7507–7512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Oyama M, Itagaki C, Hata H, Suzuki Y, Izumi T, Natsume T, Isobe T, and Sugano S (2004) Analysis of small human proteins reveals the translation of upstream open reading frames of mRNAs, Genome Res 14, 2048–2052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Xiao Z, Su J, Sun X, Li C, He L, Cheng S, and Liu X (2018) De novo transcriptome analysis of Rhododendron molle G. Don flowers by Illumina sequencing, Genes Genomics 40, 591–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Watatani Y, Ichikawa K, Nakanishi N, Fujimoto M, Takeda H, Kimura N, Hirose H, Takahashi S, and Takahashi Y (2008) Stress-induced translation of ATF5 mRNA is regulated by the 5’-untranslated region, J Biol Chem 283, 2543–2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Gerashchenko MV, Lobanov AV, and Gladyshev VN (2012) Genome-wide ribosome profiling reveals complex translational regulation in response to oxidative stress, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, 17394–17399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Andreev DE, O’Connor PB, Fahey C, Kenny EM, Terenin IM, Dmitriev SE, Cormican P, Morris DW, Shatsky IN, and Baranov PV (2015) Translation of 5’ leaders is pervasive in genes resistant to eIF2 repression, elife 4, e03971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Kozak M (2001) Constraints on reinitiation of translation in mammals, Nucleic Acids Res 29, 5226–5232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Luukkonen BG, Tan W, and Schwartz S (1995) Efficiency of reinitiation of translation on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mRNAs is determined by the length of the upstream open reading frame and by intercistronic distance, J Virol 69, 4086–4094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Hinnebusch AG (1994) Translational control of GCN4: An in vivo barometer of initiation-factor activity, Trends Biochem Sci 19, 409–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Hinnebusch AG (2005) Translational regulation of GCN4 and the general amino acid control of yeast, Annu Rev Microbiol 59, 407–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Barbosa C, and Romao L (2014) Translation of the human erythropoietin transcript is regulated by an upstream open reading frame in response to hypoxia, RNA 20, 594–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Palam LR, Baird TD, and Wek RC (2011) Phosphorylation of eIF2 facilitates ribosomal bypass of an inhibitory upstream orf to enhance CHOP translation, J Biol Chem 286, 10939–10949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Brar GA, Yassour M, Friedman N, Regev A, Ingolia NT, and Weissman JS (2012) High-resolution view of the yeast meiotic program revealed by ribosome profiling, Science 335, 552–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Gilbert WV, Zhou K, Butler TK, and Doudna JA (2007) Cap-independent translation is required for starvation-induced differentiation in yeast, Science 317, 1224–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Wek RC, Jiang HY, and Anthony TG (2006) Coping with stress: eIF2 kinases and translational control, Biochem Soc Trans 34, 7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Jackson RJ, Hellen CU, and Pestova TV (2010) The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation and principles of its regulation, Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11, 113–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Rathore A, Chu Q, Tan D, Martinez TF, Donaldson CJ, Diedrich JK, Yates JR 3rd, and Saghatelian A (2018) MIEF1 microprotein regulates mitochondrial translation, Biochemistry 57, 5564–5575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Starck SR, Tsai JC, Chen K, Shodiya M, Wang L, Yahiro K, Martins-Green M, Shastri N and Walter P Translation from the 50 untranslated region shapes the integrated stress response, Science, 2016, 351, aad3867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Zoll WL, Horton LE, Komar AA, Hensold JO, and Merrick WC (2002) Characterization of mammalian eIF2a and identification of the yeast homolog, J Biol Chem 277, 37079–37087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Sendoel A, Dunn JG, Rodriguez EH, Naik S, Gomez NC, Hurwitz B, Levorse J, Dill BD, Schramek D, Molina H, Weissman JS, and Fuchs E (2017) Translation from unconventional 5’ start sites drives tumour initiation, Nature 541, 494–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Pendleton LC, Goodwin BL, Solomonson LP, and Eichler DC (2005) Regulation of endothelial argininosuccinate synthase expression and no production by an upstream open reading frame, J Biol Chem 280, 24252–24260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Ivanov IP, Firth AE, Michel AM, Atkins JF, and Baranov PV (2011) Identification of evolutionarily conserved non-AUG-initiated N-terminal extensions in human coding sequences, Nucleic Acids Res 39, 4220–4234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Parola AL, and Kobilka BK (1994) The peptide product of a 5’ leader cistron in the beta 2 adrenergic receptor mrna inhibits receptor synthesis, J Biol Chem 269, 4497–4505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Jousse C, Bruhat A, Carraro V, Urano F, Ferrara M, Ron D, and Fafournoux P (2001) Inhibition of CHOP translation by a peptide encoded by an open reading frame localized in the CHOP 5’UTR, Nucleic Acids Res 29, 4341–4351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Young SK, and Wek RC (2016) Upstream open reading frames differentially regulate gene-specific translation in the integrated stress response, J Biol Chem 291, 16927–16935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Wang S, Miura M, Jung Y, Zhu H, Gagliardini V, Shi L, Greenberg AH, and Yuan J (1996) Identification and characterization of Ich-3, a member of the interleukin-1beta converting enzyme (ICE)/Ced-3 family and an upstream regulator of ICE, J Biol Chem 271, 20580–20587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Freitag M, Dighde N, and Sachs MS (1996) A UV-induced mutation in neurospora that affects translational regulation in response to arginine, Genetics 142, 117–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Geballe AP, and Morris DR (1994) Initiation codons within 5’-leaders of mRNAs as regulators of translation, Trends Biochem Sci 19, 159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Thuriaux P, Ramos F, Pierard A, Grenson M, and Wiame JM (1972) Regulation of the carbamoylphosphate synthetase belonging to the arginine biosynthetic pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, J Mol Biol 67, 277–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Razooky BS, Obermayer B, O’May JB and Tarakhovsky A Viral infection identifies micropeptides differentially regulated in smORF containing lncRNAs, Genes, 2017, 8, 206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Werner M, Feller A, Messenguy F, and Pierard A (1987) The leader peptide of yeast gene CPA1 is essential for the translational repression of its expression, Cell 49, 805–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Jackson R, Kroehling L, Khitun A, Bailis W, Jarret A, York AG, Khan OM, Brewer JR, Skadow MH, Duizer C, Harman CCD, Chang L, Bielecki P, Solis AG, Steach HR, Slavoff S, and Flavell RA (2018) The translation of non-canonical open reading frames controls mucosal immunity, Nature 564, 434–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Hashimoto Y, Ito Y, Niikura T, Shao Z, Hata M, Oyama F, and Nishimoto I (2001) Mechanisms of neuroprotection by a novel rescue factor humanin from Swedish mutant amyloid precursor protein, Biochem Biophys Res Commun 283, 460–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Guo B, Zhai D, Cabezas E, Welsh K, Nouraini S, Satterthwait AC, and Reed JC (2003) Humanin peptide suppresses apoptosis by interfering with Bax activation, Nature 423, 456–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Nelson BR, Makarewich CA, Anderson DM, Winders BR, Troupes CD, Wu F, Reese AL, McAnally JR, Chen X, Kavalali ET, Cannon SC, Houser SR, Bassel-Duby R, and Olson EN (2016) A peptide encoded by a transcript annotated as long noncoding RNA enhances SERCA activity in muscle, Science 351, 271–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Bal NC, Maurya SK, Sopariwala DH, Sahoo SK, Gupta SC, Shaikh SA, Pant M, Rowland LA, Bombardier E, Goonasekera SA, Tupling AR, Molkentin JD, and Periasamy M (2012) Sarcolipin is a newly identified regulator of muscle-based thermogenesis in mammals, Nat Med 18, 1575–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Fujii J, Zarain-Herzberg A, Willard HF, Tada M, and MacLennan DH (1991) Structure of the rabbit phospholamban gene, cloning of the human cDNA, and assignment of the gene to human chromosome 6, J Biol Chem 266, 11669–11675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Anderson DM, Anderson KM, Chang CL, Makarewich CA, Nelson BR, McAnally JR, Kasaragod P, Shelton JM, Liou J, Bassel-Duby R, and Olson EN (2015) A micropeptide encoded by a putative long noncoding RNA regulates muscle performance, Cell 160, 595–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Makarewich CA, Munir AZ, Schiattarella GG, Bezprozvannaya S, Raguimova ON, Cho EE, Vidal AH, Robia SL, Bassel-Duby R and Olson EN The DWORF micropeptide enhances contractility and prevents heart failure in a mouse model of dilated cardiomyopathy, eLife, 2018, 7, e38319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Matsumoto A, Pasut A, Matsumoto M, Yamashita R, Fung J, Monteleone E, Saghatelian A, Nakayama KI, Clohessy JG, Pandolfi PP mTORC1 and muscle regeneration are regulated by the LINC00961-encoded SPAR polypeptide, Nature, 2017, 541, 228–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Luo M, and Anderson ME (2013) Mechanisms of altered Ca2+ handling in heart failure, Circ Res 113, 690–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Zhang Q, Vashisht AA, O’Rourke J, Corbel SY, Moran R, Romero A, Miraglia L, Zhang J, Durrant E, Schmedt C, Sampath SC, and Sampath SC (2017) The microprotein Minion controls cell fusion and muscle formation, Nat Commun 8, 15664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Quinn ME, Goh Q, Kurosaka M, Gamage DG, Petrany MJ, Prasad V, and Millay DP (2017) Myomerger induces fusion of non-fusogenic cells and is required for skeletal muscle development, Nat Commun 8, 15665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Hindi SM, Tajrishi MM, and Kumar A (2013) Signaling mechanisms in mammalian myoblast fusion, Sci Signal 6, re2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Abmayr SM, and Pavlath GK (2012) Myoblast fusion: Lessons from flies and mice, Development 139, 641–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Laplante M, and Sabatini DM (2012) mTOR signaling in growth control and disease, Cell 149, 274–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]